- Department of Political Science and Sociology, North South University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Social Cohesion is an important issue for refugees and their host communities. Much attention on social cohesion in the literature has been focused on situations in the Middle East. This paper will bring attention to the Rohingya crisis in Bangladesh. With the influx of nearly one million Rohingya into Bangladesh in 2017, social cohesion between the Rohingya and their host communities has become more complex than ever. Although ensuring social cohesion is very important for Bangladesh, it has not been easy to implement under the present legislative framework of refugee management in Bangladesh. The sympathetic attitude of the host community toward the Rohingya has significantly declined during the past 4 years. In this context, qualitative research was undertaken to understand the challenges and dilemmas of social cohesion from both the host and Rohingya perspectives. Based on 50 key informant interviews, observations, and several informal group discussions, this paper argues that a negative perception among the neighboring host communities toward the Rohingya has increased, contributing to social tension. A pragmatic and sustainable approach has to be taken to ensure a cohesive and peaceful coexistence of the host communities and the Rohingya until dignified repatriation of the Rohingya is possible.

Introduction

Rising social tension is a potential cause of conflict among refugees and the host community. The UN and many international organizations have taken initiatives to promote social cohesion in ensuring the peaceful coexistence of the refugee and host community worldwide. Much of such attention was given to the Syrian and other refugees in various western countries. However, social cohesion was not explored much in the Rohingya and host community perspective in Bangladesh. Although the Rohingya crisis in Bangladesh started in the 1970s, social cohesion was not much discussed in the past. Despite various efforts to repatriate the Rohingya in the past episodes of the Rohingya influx in Bangladesh, many Rohingya have been living in registered refugee camps in Bangladesh. Evidence suggests that many Rohingya also made a way out to integrate into Bangladeshi communities. The influx of nearly one million Rohingya in Bangladesh in 2017 worsened the situation as the repatriation has not started yet despite various negotiations between Bangladesh and Myanmar. No one knows when the repatriation will start (Siddiqi, 2022a). Besides, the recent military coup has created further challenges in resolving the crisis (Hasan et al., 2021; Musa, 2021; Westerman, 2021).

After 4 years of the influx, when repatriation has not been the reality for the Rohingya in Bangladesh, social cohesion between the Rohingya and the host community has become more complex than ever. The host community was sympathetic with the large numbers of displaced Rohingya and extended their support to take refuge in Cox's Bazar. However, the sympathetic attitude of the host community has significantly declined during the past 4 years. In this context, this paper, based on qualitative research was undertaken to understand the challenges and dilemmas of social cohesion from both the host and Rohingya perspectives. In this paper, I argue that a negative perception among the neighboring host communities about the Rohingya has increased, contributing to social tension. Although the Rohingya generally seem to be thankful to the host community and wish to return to their home country with dignity, social tension with the locals has recently been on the rise. Both communities perceive that various anti-social and unlawful activities are on the rise due to the influx of the Rohingya. Thus, this paper shows that a pragmatic and sustainable approach has to be taken to ensure a cohesive and peaceful coexistence of the host and Rohingya until we see any practical signs of dignified repatriation of the Rohingya.

Under this backdrop, this paper provides a framework for a comprehensive understanding of the social cohesion from the host and Rohingya perspectives, which has become an important phenomenon from the Rohingya and host community perspectives. It is imperative to raise the discussion of social cohesion in the context of the Rohingya and Bangladeshi host communities. It is largely ignored by the stakeholders, researchers (including academics), and policymakers. Some NGOs have started to think about it but mainly remained in a dilemma of a project-based approach that, in many cases, will not bring a sustainable impact on the facts.

Literature review

Social cohesion is an important element of a peaceful society for a community. The idea of social cohesion is a pre-condition for building a resilient society. Social cohesion has become an important discussion for the refugee and host communities across the globe as the number of refugees is increasing worldwide. According to UNHCR, as of mid-2021, the total forcibly displaced people are 84 million worldwide, out of which 85% of forcibly displaced people are hosted in developing nations1. This has been a burden for many least and developing nations where ensuring effective social cohesion has become a challenge. After the crisis in the Middle East, Afghanistan and the Rakhine State of the Rohingya communities, the Ukrainian refugee crisis has been added as the latest country to this list. The UN and many international organizations have taken initiatives to promote social cohesion in ensuring the peaceful coexistence of the refugee and host community worldwide.

If we look into the conceptual understanding of social cohesion, we can see that social cohesion has been defined differently by the academics and researchers in various refugee and social contexts. In 1897, Durkheim, a sociologist, defined social cohesion as a characteristic of a society that shows the interdependence between individuals of a society (Berkman and Kawachi 2000 cited in Fonseca et al., 2019). “Social cohesion” refers to the ties which hold people together within and between communities and the willingness of community members to engage and cooperate to survive and prosper (The World Bank Group., 2021). Fonseca et al. (2019) provide a framework to characterize social cohesion, where they identified the elements of social cohesion. In this context, Beauvais and Jenson (2002) (cited in Fonseca et al., 2019) identified five dimensions of social cohesion: a sense of belonging, inclusion, participation, recognition and legitimacy. The social cohesion situations of the Rohingya refugees in various contexts can also be seen from these five dimensions. The Rohingya in Bangladesh significantly lack these five dimensions despite their limited interaction with the host community in Bangladesh. Social interactions seem to be an essential element of social cohesion (Shadhin et al., 2021); however, that is not present between the Rohingya and host communities. Moreover, the contemporary initiatives of fencing the camps are the attempts to keep the Rohingya and host community at a distance.

A cohesive society promotes a sense of belonging and trust. Lack of belongingness can also negatively impact the social protection of the Rohingya. Social protection is vital and can also foster social cohesion (Valli et al., 2019). Living in such complex and uncertain situations can create a situation of losing social capital. Social capital is a significant factor in the social life of a person, and the cases of the Rohingya are no different in this context. In the Colombian refugee context in Ecuador, Valli et al. (2019) show that social capital through various economic interventions helped to foster social cohesion among the refugee community. However, the cases of the Rohingya are yet to be assessed.

Despite these several definitions, there remains a sense of ambiguity and lack of consensus among many NGOs working in the refugee context, which the world bank again identified as a critical problem in achieving social cohesion among the refugee and host community (The World Bank Group., 2021). However, the definition of Guay (2016) seems to be the most relevant in this context, as he mentioned, “the set of relationships between and individuals and groups in a particular environment and between those individuals and groups and the institutions that govern them in a particular environment.” (Guay, 2016: 5). This definition emphasizes the importance of nurturing the relationship between individuals and groups, which significantly lacks in the context of Rohingya and host community perspectives as they do not have much scope for interactions.

Interaction between the host and the Refugee community is one of the requirements for ensuring social cohesion (Shadhin et al., 2021). The situation of the Rohingya and host community in Bangladesh is not an exception. The GoB is very careful in promoting any intervention that requires the integration of the Rohingya with the host community. Because of this approach, the GoB does not provide any space for social interaction between the Rohingya and the host community. This is a key barrier to ensuring a cohesive relationship between these two communities.

Besides, the repatriation of the Rohingya after the influx of 2017 has become a “myth” (Siddiqi, 2022a) as not a single effort has been taken seriously; the apparent reality is to ensure an environment where both Rohingya and host community people stay in a peaceful condition. This is not an easy task to ensure without acknowledging the Rohingya as refugees by the Government of Bangladesh because the status of Forcibly Displaced Myanmar Nationals does not ensure many rights of the Rohingya population. Besides, Bangladesh does not want to integrate Rohingya into Bangladesh. Thus, the question arises, what would be a viable and sustainable method of ensuring social cohesion without social integration, as social interaction is the main element of social cohesion. Social interaction cannot be possible without social integration between these two communities.

Since the Rohingya who entered Bangladesh in 2017 does not have refugee rights in Bangladesh, the Government of Bangladesh (GoB) has clearly stated her position not to recognize the Rohingya as a refugee; instead, she defined the Rohingya as Forcibly Displaced Myanmar Nationals (FDMNs). The GoB is not a signatory of the 1951 Refugee Convention that allows Bangladesh to have such a position. Thus, the Rohingya are deprived of many rights from Bangladesh, such as freedom of movement, the right to work, formal education (non-formal education has been implemented in camps), accessibility to travel documents etc., as highlighted in the convention2. Although Bangladesh has been providing many other essential rights to the Rohingya in camps with the assistance of various national and international agencies, it is reluctant to grant the Rohingya refugee status who entered Bangladesh in or after 2017. This is a strategic decision of Bangladesh which may also have various financial and political implications for Bangladesh. In order to ensure such refugee rights, Bangladesh needs to implement and provide certain services that would have been an enormous challenge and burden for Bangladesh as a developing nation it has to deal with various development challenges of its own. Moreover, the growing dissatisfaction and neglect from the host community under the present situation is another challenge for Bangladesh. The host communities think that the Rohingya have received all the attention with financial and aid support.

Moreover, the Rohingya suffer from an identity crisis from two perspectives: one as a refugee and the other is a crisis of identity as Rohingya as there is no sign of dignified repatriation yet. They belong nowhere in the Bangladesh context. In addition, the Government of Bangladesh has not yet finalized or drafted a comprehensive refugee policy as it has been witnessing the Rohingya refugee crisis for many decades now (Siddiqi and Kamruzzaman, 2021). The non-existence of a comprehensive refugee policy in Bangladesh has been a critical barrier to ensuring many rights of the Rohingya and promoting a practical approach to social cohesion as there are no guidelines about social cohesion.

Finally, all stakeholders must consider the growing dissatisfaction among the host community over the Rohingya crisis, which shows a drastic shift in their sympathy toward the Rohingya crisis (Ansar and Md. Khaled, 2021; Siddiqi, 2022b). Thus, demonizing the Rohingya in various aspects has become a reality in local and national contexts. Various local and national newspapers have already started to view the Rohingya negatively. The extrajudicial killing of many Rohingya results from such an approach (Amnesty International., 2020). It is hard to find positive news on the Rohingya in Bangladesh news media. The phrase “Rohingya” has become a buzzword, and people have started to use the word as slang in many areas of Bangladesh. Although demonizing the Rohingya will not bring any solution to the crisis, it will complicate the situation further, and a sense of resistance may be evident among the Rohingya in the future. Many already bring out the possible security threat of the Rohingya crisis not only in Bangladesh but also in the region, which is alarming (Prasse-Freeman, 2017).

Methods

Data was collected using a qualitative research method. A semi-structured interview process was convened to collect data. Besides this, the author carried out observations and several informal group discussions among the Rohingya and host community members. A total of 50 semi-structured interviews were conducted; among them, 25 were conducted with the Rohingya, and 25 were conducted with the host community. The author has visited Rohingya camp several times since the Rohingya influx in 2017 in Cox's Bazar. Insights from the repeated visit to the camps and interactions with the Rohingya and host community members provided the author with an in-depth understanding of the phenomenon. The interviews were translated into Bengali from the dialect used by the Rohingya, which is close to the local Chittagonian dialect (a dialect of Bengali). A comprehensive data matrix was developed from the interview data using excel with relevant quotations with the help of a research assistant.

Findings

The findings are organized into broadly two sections: perspectives from the host community and the Rohingya community to understand the challenges of promoting and ensuring social cohesion. In addition, a policy perspective was added based on the understanding of the Rohingya and host community that would be beneficial for the policymakers, researchers and activists (various national and international humanitarian actors working in the areas of Rohingya crisis). Findings show that declining sympathy and growing dissatisfaction help develop a negative perception among the host community regarding the Rohingya communities, which is the key challenge to social cohesion. Moreover, demonizing the Rohingya in local and national news agencies has become another difficulty in relation to social cohesion. In contrast, the Rohingya community generally seems thankful to Bangladesh for providing shelter and meeting their other needs at camps. However, various unlawful activities of the Rohingya and their tendency to work outside the camps secretly are seen as problematic. This deteriorates the relations with the host community as perceived by the Rohingya. Although this is entirely a survival strategy of the Rohingya, it can be a critical challenge in ensuring peaceful coexistence between these two communities. The following section of the findings will shed light on these issues in an elaborated form. This section begins with the declining sympathy among the host community.

Why has the sympathy gone?

Members of the host community from various areas of Ukhiya and Tekhnaf were the first responders toward the persecuted Rohingya in Myanmar who sought refuge in Bangladesh in 2017. Their helping efforts can be seen as good examples of community response to one of the complex refugee crises in the present time. The question arises: What exactly has changed the attitudes and approaches of the host community toward the Rohingya population in Bangladesh. Interviews data and observations from several field visits to Rohingya camps and the neighboring areas in the Cox's Bazar reflect that prolonged staying without any hope of the repatriation of the Rohingya community has created dissatisfaction among the host community. Host community people could not predict that the staying of the Rohingyain Bangladesh would be prolonged. In addition to this, the host community perceives that the Rohingya influx in 2017 has created several challenges for the host community. One of the issues is a threat to peaceful coexistence. A person mentioned in this context that,

A good number of Rohingya entered Bangladesh in 2017. This is why this large number population can cause so much chaos. We have a little interaction and communication with them [the Rohingya]. I believe the only way to ensure peace between the Rohingya and the host community is by sending them to Myanmar. A 23-year old young man from a host community.

In a similar context, another person mentioned his experiences.

We had some conflict with the Rohingya sometimes. The initiatives of the village leaders resolved these conflicts. For example, one Rohingya man borrowed 20K BDT almost a month ago, but now he is unwilling to repay his debt. If I ask for my money, he threatens me. They get such courage because of their involvement with ARSA. A middle-aged village doctor.

The next concern is the economic impact on the host community. Informants emphasized that the living expenses have increased due to the presence of the Rohingya community and increased activities of NGO lead intervention. The same village doctor shared that the influx of the Rohingya caused an increased price of everyday goods in their locality. He had a mango tree garden that was a profitable income source for him; it has been used as a camp area for the Rohingya. A student shared a similar experience. As he mentioned,

We have been experiencing several problems since the Rohingya came to Bangladesh. The main difficulty is the unbearable price hike in the local area. The next problem is lowering the daily wages for the day-laborer as many Rohingya started working in the neighboring host community area without any approval of the camp authority. Besides, the Rohingya influx has also brought hundreds of NGOs to the areas, creating challenges in our daily communication as the traffic has become unbearable. A student from a host community.

An undergraduate student mentioned that.

I am a student. I maintain my family tutoring other students. Our people have been facing difficulties since the Rohingya came to Bangladesh in 2017. Although the job opportunity has increased, the wage rate has significantly decreased due to the Rohingya entering the local job market. A 19-year-old student.

All respondents from the host community mentioned various issues that negatively affected their lives. They witnessed a disruption of their daily social life due to the influx of the Rohingya in the region. It also brought thousands of NGO workers into their areas, impacting the local culture. In some cases, the opportunities for the local businesses have increased, but at the same time, prices of many daily necessities have also increased with the increasing demand. The rent of houses has increased because of this reason. Many people find it very difficult to find a decent rented house because of higher prices. Many people also rose that they lost their opportunities to cultivate the government lands due to the makeshifts camps. Some lost their land as many Rohingya started to live in those areas and never shifted to another place.

There have been constant complaints among the host population that humanitarian workers do not want to recruit staff from their community. They also claim that the host community people have been deprived as they do not receive much financial and relief help and assistance from the GoB. A local doctor mentioned that,

We do not receive any relief goods as the Rohingya receive. However, some people receive some assistance from the local Union Parishad, but we do not have any conflict or tension with this. Like the Rohingya, we sometimes receive health services which are not sufficient, and they are biased toward the Rohingya. A middle-aged village doctor.

There has been an impact on the wages and income of the day-laborer from the host community. This is because of the willingness to work in reduced wage rate by the Rohingya. This is why many people from the host community do not recruit labor from the host community, as it is much cheaper to recruit day labor from the Rohingya community. Although the Rohingya are not allowed to work in the host community, the ground reality is significantly different in many Rohingya day laborers regularly go outside their camps to work for the host community. In this context, one small businessman shared his experience as he mentioned:

I also recruited Rohingya people to work for me. It is easy to get Rohingya workers to work for us. If I just call one person, he will bring the required number of people to work for me. They work at a cheap wage rate, which is beneficial for me. They are serious and sincere toward their work. Besides, they are hard-working, and they can work long hours. This is how they utilize every little opportunity that they get (A local businessman, Ukhiya Bazar).

Such an approach has a tremendous impact on the local wage market. People in the host community see that Rohingya day-laborers are taking away their jobs, and poor and marginalized day laborers have been suffering from it. Many people from the host community also brought the issues of environmental challenges due to the Rohingya influx. It broadly has two impacts: the host community depended on the government land (known as khash land), which is no longer available to the host community as the camps were mainly built on these lands. And the other is a reduced green zone with a severe environmental impact.

Thus, it has already created a growing dissatisfaction among the host communities. The result of such attitudes is the declining sympathetic approach toward the Rohingya. Instead, the phrase Rohingya has become a negative terminology among the host community. The impact of such negativity can be seen through the approach of demonizing the Rohingya in various ways. The following section will discuss the challenging issues of demonizing the Rohingya.

Demonizing the Rohingya

The previous section presented how various levels of dissatisfaction were translated into a negative perception of the Rohingya among the host community. Declining sympathy of the host community gradually contributes to demonizing the Rohingya in various ways. The negative perception among the neighboring host communities about the Rohingya has increased, contributing to social tension between them. Demonizing the Rohingya and the idea of social tension complement each other. This is one of the main challenges to the peaceful coexistence of the Rohingya. The first step of the demonisation process begins with bringing the perceived threat of the existence of Rohingya in the neighborhood of the host population. For example, host community members repeatedly brought the issue of unlawful activities of the Rohingya and increased patterns of illegal activities in the neighborhood. In this context, a host community member mentioned that,

The new Rohingya [who entered Bangladesh in 2017] have created risks for us. They have started engaging in various unlawful activities, such as conflict, trafficking in persons, killing, drug trafficking, etc. A middle-aged business person.

Another person mentioned that many unlawful activities of the Rohingya cause threats to the host community. While discussing with the host community, they frequently referred to the phrases associated with demonizing the Rohingya. They see the camps as the breeding ground for unlawful activities, criminal activities, radicalization, etc. The most common complaints from the host communities about the Rohingya are stealing cows and goats and involvement in the robbery. All these have created a sense of fear among many host community people. While my conversation in various places in Ukhiya and neighboring camps areas, I noticed none of the host community members referred to the positive aspects of the Rohingya. One elderly person even mentioned that “we are living in a fear that the Rohingya would probably occupy Ukhiya and Teknaf one day. They would outnumber us in every aspect”. The number of Rohingya is almost tripled compared to the host community population in Ukhiya and Teknaf. Such attitudes help to build a negative image of the Rohingya. Similar views were expressed by many people living in the neighboring Rohingya camps.

In the context of violence and radicalization, the name of Al Yakin frequently came into the discussion of the host community. This is seen as a dangerous group that has been perceived as promoting violence and conflict. Many people from the host community repeatedly referred to this radical group. They firmly believe that this particular group has been active in creating fear through violent activities in the neighborhood. The local people also vehemently claimed that their lack of security and perceived wellbeing were severely hampered after these new Rohingya came to Bangladesh in 2017. Most people from the host community think that the new Rohingya have been creating problems more than the old Rohingya, who have been living in Bangladesh in two registered Rohingya camps for decades.

While referring to the crimes and conflict, a young betel nut business person mentioned that,

After taking shelter in Bangladesh, they [The Rohingya] have started various problems. Many of them have been engaged in kidnapping people for ransom. Various unlawful activities have increased after they arrived in our country.

As mentioned earlier, the Rohingya have already lost their reputation among the host community, and newspapers have been representing them negatively. Both the nature of declining sympathy and demonizing the Rohingya complement each other. However, it can be argued that demonizing the Rohingya will not ensure the peaceful coexistence of the Rohingya and the host community in the camp areas. Without the Rohingya perspective, understanding social cohesion will not be completed. Thus, the following section briefly will show results from the perspective of the Rohingya.

Rohingya perspectives of social cohesion

In contrast to such negative views from the host community members, my field data indicates that most Rohingya do not show their dissatisfaction and anger over the host community. They generally offer their thankful attitude toward Bangladesh Government and toward the people of Bangladesh. They do not have a critical perspective toward the Host community member.

Although the Rohingya generally seem to be thankful to the host community and wish to return to their home country with dignity, social tension with the locals has recently been on the rise. However, in some cases, many people from the Rohingya community show their dissatisfaction toward the host community as the interaction is increasing slowly in the neighboring Rohingya camps with the host community. A Rohingya housewife mentioned that,

We are happy to stay in a land of a host community. Many of them demand rent for their land. We are not very happy about this. How could we pay their rent? This induces conflict with the host community people. The local leaders intervene to resolve such issues. A 59-year-old Rohingya housewife.

Some Rohingya also think that the host community has benefited from increased jobs and other opportunities because of the Rohingya influx in 2017. The Rohingya influx before 2017 did not attract such substantial global attention. The entire place is now under the international community's attention due to the Rohingya, which has changed the areas. The Rohingya see it from a perspective that has benefited the host more than the Rohingya. In addition, many also pointed out that the host community people, in many cases, manipulate the system to receive the relief goods that also benefit the host community. Another Rohingya housewife mentioned that,

The job opportunity of the host community people increased after we arrived in Bangladesh. Although we are receiving relief, we are living a difficult life here as we only receive minimal living support. Besides, some host people from the local areas started to receive relief like us by making fake identity cards. A 30-year-old Rohingya housewife.

In the previous section of the findings, I mentioned that the study reveals that many Rohingya have started to work outside the camps since they arrived in Bangladesh in 2017. Many Rohingya told me this in our discussion. Many of them already mentioned how they go out and return in the evening without informing the camp management authority. Although this is entirely a survival strategy of the Rohingya, it can be a critical challenge in ensuring peaceful coexistence between these two communities. Most of the respondents shared that they lived several economic hardships in camps. They only rely on relief goods that are insufficient, and do not fulfill all their needs. As a Rohingya man mentioned in this context,

We do not have any income at all in the camp because we are not allowed to go out of the camp to work. We have to maintain our lives based on relief goods. Sometimes, we need to sell our oil bottles to buy other necessities. A 59-year-old Rohingya man.

Few Rohingya admitted that their prolonged stay in camps had created problems for the neighboring host communities. As a Rohingya student mentioned that,

The host community people have faced many challenges after our arrival. Due to the increased Rohingya population, the price of the necessary daily goods has increased. A 21-year-old Rohingya student.

But the number of such Rohingya people is not very high, and they are concerned about their problems in camps. Living in camps with post-traumatic situations is not easy. Besides, they do not know what exactly would be their fate as there is no sign of a potential solution. Thus, looking for a better life under this condition seems to be their key priority. Under such circumstances, many of them have started to raise concerns about various issues living in camps, which are the reasons for their dissatisfaction. Like the growing dissatisfaction of the host community, the Rohingya also have dissatisfaction in receiving services from the camps. The first and foremost concern that the Rohingya have is their children's education as a housewife mentioned that “the education facilities for our children are not enough here. We also do not receive a better health service”.

However, most Rohingya do not want to share their negative perception of the host community. As I mentioned earlier about demonizing the Rohingya referring to various unlawful incidents and activities of the Rohingya, most of the Rohingya respondents of the research show no empathy toward the Rohingya who are engaged in various illegal and unauthorized activities. They also live in fear while referring to the Rohingya people from the underworld. As a student mentioned that,

Those Rohingya who do all these unauthorized and unlawful activities are also the sources of fear for us. But not every Rohingya is involved in such activities. Those who are involved in such activities should be punished. If that can be done, the crimes will be reduced. A 21-year-old Rohingya student.

But there are some Rohingya who think that some host communities exploit and oppress the Rohingya community. This is probably another reason many Rohingya do not want to create social relationships with the host community. As a female Rohingya mentioned that,

We do not have a social relationship with the host community as they repeatedly oppress us. They scold us frequently with our names. The name Rohingya has become a slang word now. We also witnessed some conflict with the host community. But we do not see any resolution to such conflicts. A 35-year-old Rohingya female.

But most Rohingya believe that ensuring a good relationship between the host and Rohingya community is an element of peaceful coexistence. A Rohingya housewife mentioned that,

Promoting the social relationships between the Rohingya and host community people are crucial to ensure social cohesion and peaceful coexistence. If a good relationship can be ensured between us, we will be able to live in peace. A 30-year-old Rohingya housewife.

In contrast, to ensure a cohesive environment for both Rohingya and the host community perspective, shifting a portion of the Rohingya to a remote island called Bhashan Char by the Government of Bangladesh will not bring any positive impact in terms of social cohesion. Because of social isolation in Bhashan Char many Rohingya have already started to flee the island secretly. Many take a risky journey in the Bay of Bengal, putting their lives in danger. Such an approach may not bring a solution to ensure a peaceful coexistence as not every Rohingya will be shifted there.

Discussion

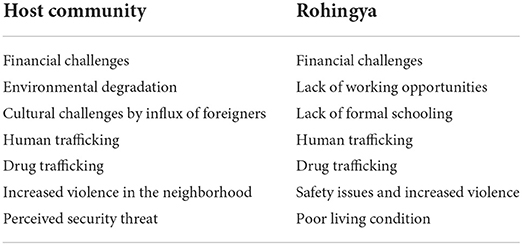

There has been growing dissatisfaction, and declining sympathy is evident among the host community as the sustainable resolution to this Rohingya crisis has not been started yet (Siddiqi and Kamruzzaman, 2021). Besides, rising crime, prostitution, theft, and drug and human trafficking are some of the known unlawful activities that have increased since the last Rohingya influx in 2017 (Siddiqi, 2022a). Price hikes and economic imbalance in the wage market were repeatedly mentioned by the host community, creating further challenges in the lives of the host community. Ansar and Md. Khaled (2021) find similar perspectives that shape the attitudes of the host community toward the Rohingya. The following table shows some of the perceived difficulties by the host and Rohingya that have been making their lives and social cohesion hard (Table 1).

The presence of nearly a million Rohingya refugees in Ukhiya and Teknaf became a substantial demographic “shock” for the host community member. Displacement is often associated with social disruption, tension, grievance, social fragmentation and economic upheaval (Berry and Roberts, 2018). Both communities perceive that various criminal activities are increasing due to the Rohingya influx, which is seen as a threat to peaceful coexistence. Such a negative attitude has demonized the Rohingya in many cases, both in the local and national contexts. However, demonizing the Rohingya is not a solution. Demonizing the Rohingya would not bring any solution to the peaceful coexistence between the Rohingya and host communities. Instead, it may increase the tension between them further. There remains a risk of tension between the host and the Rohingya community was published in various newspapers (Shishir, 2019).

The indefinite stay of the Rohingya in Bangladesh would intensify the tension between the Host and Rohingya (Sharma, 2021). In addition, there have been no signs of Rohingya repatriation since the 2017 influx (Siddiqi, 2022a,b). Besides, growing tension and a gradual decline in sympathy are already there (Kamruzzaman and Siddiqi, 2022). Now the question arises, can it be possible to ensure social cohesion without social integration? Social cohesion is often seen as the first step of social integration. Let us look at the standpoint of the Government of Bangladesh. GoB does not favor promoting any sense of social integration of the Rohingya due to the fear of delaying the repartition. But the question arises, is it possible to ensure social cohesion without the interactions between these two communities.

Two important issues have to be mentioned here: the Rohingya perspective of the problem and social cohesion. Like many other refugee situations, the Rohingya context also shows declining sympathy among the host community that contributes negatively toward social cohesion. Although this is not an option for the Rohingya to live in makeshift camps in Bangladesh, the living conditions and standards are not satisfactory as many Rohingya also claim, and a just a visit to a camp would prove the claim. Under such living conditions, the Rohingya also expect a quick and sustainable solution to the crisis. The prolonged delay in dignified repatriation of the Rohingya would only increase their vulnerability (Siddiqi, 2022a).

A critical question is whether it can be applied to Rohingya-host community perspectives in Bangladesh. This is why a project-based, short-term, and unsustainable model of social cohesion can be seen to be implemented by different stakeholders among the Rohingya communities in camps with the donor-driven approach. Besides, the lack of a medium to long-term strategy seemed to be a huge problem in refugee management (Sullivan, 2021). This is why it needs to develop a local model of social cohesion as Bangladesh has not recognized these Rohingya as refugees; instead, they are identified as Forcibly Displaced Myanmar Nationals (FDMNs). Thus, there has been no priority given to social cohesion.

In the past, no attention has been given to the failure of developing a comprehensive refugee policy. Thus, no priority in the areas of social cohesion. Bangladesh Government approached the crisis on an Ad-hoc basis, which is not seen as the right approach (Siddiqi and Kamruzzaman, 2021). Besides, seeing the crisis from the disaster and security perspective has created further challenges. The wellbeing of both Rohingya and host communities in the name of social cohesion was significantly ignored. Besides, the idea of social interaction, which is the key to ensuring a cohesive relationship between the host and Rohingya community (Shadhin et al., 2021), can hardly be found on the ground. My findings also show such a trend, but the interaction has to be increased for a better and more cohesive society. Otherwise, the social distance between these two communities is likely to be increased, which is not good for their peaceful coexistence. Moreover, the GoB's strategy to relocate part of the Rohingya to a remote island to hope for better livelihood opportunities will increase the living standard of the Rohingya (Islam et al., 2022). However, this may not contribute positively to ensuring a cohesive relationship between the host and refugee as it will only create distance between these two communities.

Finally, policymakers and implementers should also consider that dignified repatriation has to be seen as a priority while ensuring social cohesion. Otherwise, it would further put the future of repatriation at a stake that is not expected.

Conclusion

Although social cohesion is an important element for the peaceful co-existence between the host and Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh, this is not very easy to implement under the present legislative framework of refugee management in Bangladesh. Because in the present refugee management system in Bangladesh, there remains not much scope for promoting social cohesion. This remains equally challenging as GoB strictly does not want to promote social integration or increase social interactions of the Rohingya within Bangladesh. Thus, such an approach has already created a challenges for Bangladesh to implement and promote social cohesion. Therefore, the following measures should be taken for a better social cohesion. First, there has to be a delicate balance between the western and local approaches to seeing and implementing social cohesion-related intervention. Second, recognizing the local socio-cultural context while developing any social cohesion intervention. Third, social cohesion intervention programs can be very complex; thus, a comprehensive and coordinated approach has to be taken where interactions between these two communities has to be increased for a better and more cohesive relationship. Fourth, the “One-size-fits-all” – approach has to be avoided, and a holistic approach (it requires cooperation between peacebuilding, humanitarian aid, and development actors) has to be adopted with an evidence-based approach has to be adopted while developing an intervention to ensure social cohesion.

A pragmatic and sustainable approach has to be taken to ensure a cohesive and peaceful coexistence of the host and Rohingya until we see any practical signs of dignified repatriation of the Rohingya. In many cases, the voices of the key stakeholders are ignored while developing an intervention. The situation of the Rohingya refugees and the host communities in Bangladesh is an example of this. Their voices and perspectives have to be listened to before developing any comprehensive intervention on social cohesion. Above all, policymakers and implementers should continue working on the dignified and voluntary repatriation as the priority while ensuring social cohesion. Bangladesh needs to develop a comprehensive policy on the Rohingya crisis and open all channels to keep the pressure on Myanmar and the international communities.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because: This is qualitative research and funded by North South University. I do not have a clearance from my university to share qualitative research data. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to mohammad.siddiqi@northsouth.edu.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the director of CPS, SIPG, North South University. Informed consent was taken before the interview.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

The research is funded by SIPG-CPS research grant provided by North South University.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^‘Refugee Data Finder’ accessed on 15 May 2022 from https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/#:~:text=An%20estimated%2035%20million%2042,age%20(end%2D2020).&text=Between%202018%20and%202020%2C%20an,a%20refugee%20life%20per%20year.

2. ^‘The Refugee Convention, 1951’ see https://www.unhcr.org/4ca34be29.pdf last accessed on 7 July 2022.

References

Amnesty International. (2020). Let Us Speak for Our Rights: Human Rights Situation of Rohingya Refugees in Bangladesh, London.

Ansar, A., and Md. Khaled, A. F. (2021). From solidarity to resistance: host communities' evolving response to the Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh. J. Int. Human. Action 6, 1–14. doi: 10.1186/s41018-021-00104-9

Berry, J. P., and Roberts, A. (2018). Social cohesion and forced displacement: a desk review to inform programming and project design. The World Bank.

Fonseca, X., Lukosch, S., and Brazier, F. (2019). Social cohesion revisited: a new definition and how to characterize it. Innovat. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 32, 231–53. doi: 10.1080/13511610.2018.1497480

Guay, J. (2016). Social cohesion between Syrian Refugees and Urban Host Communities in Lebanon and Jordan. World Vision. Available online at: https://preparecenter.org/sites/default/files/social-cohesion-clean-10th-nov-15.pdf (accessed August 11, 2022).

Hasan, M., Hawksley, C., Georgeou, N., and Ruud, A. E. (2021). What Myanmar's coup d'état means for the Rohingya refugees and their future. ABC News. Available online at: https://www.abc.net.au/religion/myanmar-military-coup-and-the-future-of-the-rohingya-refugees/13180680 (accessed August 11, 2022).

Islam, M. M., Barman, A., Khan, M. I., Goswami, G. G., Siddiqi, B., and Mukul, S. A. (2022). Sustainable Livelihood for Displaced Rohingyas and Their Resilience at Bhashan Char in Bangladesh. Sustainability 14, 6374. doi: 10.3390/su14106374

Kamruzzaman, P., and Siddiqi, B. (2022). Lessons for Ukraine from the Rohingya crisis: even sympathetic communities can lose their enthusiasm for hosting refugees. The Conversation. Available online at: https://theconversation.com/lessons-for-ukraine-from-the-rohingya-crisis-even-sympathetic-communities-can-lose-their-enthusiasm-for-hosting-refugees-181365 (accessed August 11, 2022).

Musa, M. (2021). Panel Discuss Rohingya future following Myanmar coup: Academics, journalists, politicians urge sanctions, embargo against military leaders. Anadolu Agency. Available online at: https://www.aa.com.tr/en/asia-pacific/panel-discuss-rohingya-future-following-myanmar-coup/2166498# (accessed August 11, 2022).

Prasse-Freeman, E. (2017). “The Rohingya crisis,” in Anthropology Today. Vol. 33. doi: 10.1111/1467-8322.12389

Shadhin, S., Zahin, N., and Rabbi, F. U. (2021). Understanding social cohesion between the Rohingya and host communities.pdf. BBC Media Action. Available online at: https://www.dropbox.com/s/32f6mazzfxasuk4/UnderstandingsocialcohesionbetweentheRohingyaandhostcommunities.pdf?dl=0 (accessed August 11, 2022).

Sharma, I. (2021). Indefinite Hosting of Rohingya Refugees a Growing Concern for Bangladesh. The Diplomat. Available online at: https://thediplomat.com/2021/07/indefinite-hosting-of-rohingya-refugees-a-growing-concern-for-bangladesh/ (accessed August 11, 2022).

Shishir, Q. (2019). In Bangladesh, Rohingya refugees face risk from a xenophobic media onslaught. Available online at: https://scroll.in/article/937623/in-bangladesh-rohingya-refugees-face-risk-from-a-xenophobic-media-onslaught?fbclid=IwAR06ie-41-FUEwTVf5leH6GlpHcbdd8QYkQbsQWWDqUP8zmu7pwTqphPjPg

Siddiqi, B. (2022a). “The ‘Myth’ of Repatriation: The Prolonged Sufferings of the Rohingya in Bangladesh,” in N. Uddin (Ed.), The Rohingya Crisis Human Rights Issues, Policy Concerns and Burden Sharing. 1st Edition (India: SAGE). p. 334–357.

Siddiqi, B. (2022b). Will Rohingya repatriation ever happen? Available online at: https://www.thedailystar.net/views/opinion/news/will-rohingya-repatriation-ever-happen-2992656 (accessed March 29, 2022).

Siddiqi, B., and Kamruzzaman, P. (2021). Policy challenges towards rohingya crisis in bangladesh the role of national development experts. Center for Peace Studies Working Paper Series. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3979905

Sullivan, D. P. (2021). ReliefWeb. Fading Humanitarianism: The Dangerous Trajectory of the Rohingya Refugee Response in Bangladesh - Bangladesh. May. Available online at: https://reliefweb.int/report/bangladesh/fading-humanitarianism-dangerous-trajectory-rohingya-refugee-response-bangladesh (accessed August 11, 2022).

The World Bank Group. (2021). Refugee Policy Review Framework : Technical Note (English). Available online at: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/159851621920940734/pdf/Refugee-Policy-Review-Framework-Technical-Note.pdf (accessed August 11, 2022).

Valli, E., Peterman, A., and Hidrobo, M. (2019). Economic transfers and social cohesion in a refugee-hosting setting. J. Develop. Stud. 55, 128–146. doi: 10.1080/00220388.2019.1687879

Westerman, A. (2021). What Myanmar's Coup Means For The Rohingya. NPR. Available online at: https://www.npr.org/2021/02/11/966923582/what-myanmars-coup-means-for-the-rohingya (accessed August 11, 2022).

Keywords: Rohingya, repatriation, identity, peace, social cohesion, vulnerability

Citation: Siddiqi B (2022) Challenges and dilemmas of social cohesion between the Rohingya and host communities in Bangladesh. Front. Hum. Dyn. 4:944601. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2022.944601

Received: 15 May 2022; Accepted: 08 August 2022;

Published: 31 August 2022.

Edited by:

Abu Faisal Md. Khaled, Bangladesh University of Professionals, BangladeshReviewed by:

Annekathryn Goodman, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, United StatesEmily Pelley, Canadian Defence Academy/Dallaire Centre of Excellence for Peace and Security, Canada

Copyright © 2022 Siddiqi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bulbul Siddiqi, bW9oYW1tYWQuc2lkZGlxaUBub3J0aHNvdXRoLmVkdQ==

Bulbul Siddiqi

Bulbul Siddiqi