94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Hum. Dyn., 23 August 2022

Sec. Dynamics of Migration and (Im)Mobility

Volume 4 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fhumd.2022.898081

This article is part of the Research TopicNew Insights in Refugees and ConflictView all 5 articles

Refugee youth in protracted humanitarian contexts are faced with limited access to quality education. They may sustain traumatic experiences from conflicts and discrimination yet have limited psychosocial support access. Comprehending the magnitude and effects of these challenges is vital for designing and executing educational interventions in such contexts. This study evaluates the implementation quality of the Youth Education Pack intervention through the lens of the Inter-agency Network for Education in Emergencies minimum standards framework. It explores the types of discrimination experienced by refugee youth in the Dadaab refugee camp in Kenya. Nine participants comprising refugee students (N = 2), former refugee students (N = 2), teachers (N = 3), and project supervisors (N = 2) participated in the study. The first author conducted interviews and observations in the camp. The data were qualitatively coded deductively and analysed in Nvivo 12. We found that the YEP intervention faced contextual challenges that hindered the achievement of the implementation quality standards outlined in the INEE minimum standards for education. Refugee youth and refugee teachers experienced various forms of discrimination, including at individual, institutional, and structural levels. We conclude that providing refugee youth with an inclusive and high-quality education is central to providing secure and long-term solutions to their challenges and adversities and may promote their psychosocial wellbeing.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) reported that by the end of the year 2020, 82.4 million people were displaced around the globe, of which 32 per cent were refugees, and about 24 per cent were children under 18 years of age (UNHCR, 2021a). Prolonged wars, conflicts, and extreme violence are among the factors that have contributed to the adverse interruption of the educational and developmental processes of the school-age group of refugees (OECD, 2019; Kim et al., 2020; Lasater et al., 2022). Consequently, many have lost essential formal schooling during the conflicts (Milner and Loescher, 2011; Deane, 2016; Flemming, 2017), including lower literacy rates and widened gaps in knowledge across academic subjects (Birman and Tran, 2017). In addition, this school-age group of refugees have been exposed to violence, sexual abuse, forced marriage, recruitment into armed groups, and other activities that risk their lives (Talbot, 2013; Deane, 2016; UNHCR, 2016; Hamad et al., 2021). Most refugee youth who are over-age and cannot go through basic education are mainly faced with limited access to quality education and psychosocial development support (Berthold, 2000; Taylor and Sidhu, 2012; Flemming, 2017; NRC, 2020).

Education interventions in humanitarian settings, on the one hand, are vital tools that protect learners from physical harm and provide opportunities for their cognitive, emotional, and social development. School attendance helps to restore a sense of normalcy and creates an environment for positive interactions amongst peers and with educators and creates opportunities for developing important life skills (Taylor and Sidhu, 2012; MacKinnon, 2014; Lasater et al., 2022). For over-age refugee youth, interventions accelerate their learning and building of skills and enable them to recover the lost school years (Shah, 2015; Deane, 2016; Birman and Tran, 2017; Flemming, 2017). On the other hand, studies show that refugee learners in humanitarian contexts navigate a spectrum of adversity in educational spaces that include lower-quality education and experience of exclusion and discrimination (Oh and van der Stouwe, 2008; Dryden-Peterson, 2011; Kelcey and Chatila, 2020). One way of mitigating these gaps is to provide a high-quality education to all learners in these contexts. In this study, therefore, we evaluate the implementation quality of a widely enacted Youth Education Pack (YEP) intervention in the Dadaab refugee camp in Kenya. This study will be the first to evaluate the implementation quality of the YEP intervention using a holistic and more comprehensive Inter-agency Network for Education in Emergencies (INEE) minimum standards framework (INEE, 2010).

The YEP intervention is a vocational education intervention that targets youth refugees in humanitarian contexts who have had minimal or no basic education as a result of displacement. The intervention comprises foundational (numeracy and literacy) skills, life, and vocational skills and is designed to accelerate learning and support refugee youth in such contexts to acquire basic livelihood skills. The YEP has been implemented in the Dadaab refugee camp for over 12 years (NRC, 2015). The underlying goal of the programme is to mitigate conflicts, create sustainable peace, and provide a pathway for returning to normal life and livelihood (Monaghan and King, 2018).

Located in Eastern Kenya, the Dadaab refugee camp was established in 1991 by the Government of Kenya and the UNHCR to provide temporary settlement for Somali refugees displaced by civil war in Somalia (United Nations, 1992; MacKinnon, 2014; Monaghan, 2021). Recent statistics by UNHCR (2021b) indicate that over 223,800 registered refugees and asylum seekers are hosted at this camp. About 96% of this number represents refugees from Somalia, and the rest are from other countries in Eastern and Central Africa. A 2020 report showed that of the over 217,000 registered refugees and asylum seekers in the camp, about 58% comprised children and youth under 17 (UNHCR, 2021b, p. 3), pointing to a significantly young refugee population. Besides the four vocational centres, there are 22 primary schools, six secondary schools, and four non-formal education centres in the Dadaab refugee camp. The number of schools is far lower than the demand for education, and over 45% of school-age learners are out of school (NRC, 2015; UNHCR, 2017). Even though students can attend public education institutions outside the camp, the logistical challenge exacerbated by the Kenyan government encampment policy that restricts the movement of refugees out of the camp is insurmountable (The Republic of Kenya, 2013; Flemming, 2017). The average teacher-student ratio in classrooms at the camp is as high as 1:69 (Flemming, 2017). About 72% of refugee teachers in the camp have only secondary school academic qualifications and are not adequately supported with training and teaching resources (Mendenhall et al., 2015; World Bank and UNHRC, 2021). Research shows that these factors may hinder the delivery of quality education to refugees in humanitarian contexts (e.g., Dryden-Peterson, 2011; MacKinnon, 2014; Mendenhall et al., 2015; Burde et al., 2017; Soares et al., 2021). Yet, fewer studies have focused on assessing the quality with which education interventions targeting refugee youth are implemented in such contexts.

Education in Emergencies (EiE) refers to “education that does not fit into traditional development planning. It is about the effects of an event such as a cyclone, a drought, a war, or civil conflict”, which disrupt and cause schooling to happen in conditions that are not normal (Bensalah, 2002, p. 9). In such emergency circumstances, where state services are broken down, non-state actors such as international or non-governmental organisations often support education interventions that aid the continuation of learning. EiE, therefore, often comprises initiatives that manage the effects of interruptions caused by crises, and it essentially constitutes protective strategies that save and sustain the physical, psychosocial, and cognitive wellbeing of learners (INEE, 2010; Nicolai et al., 2015; Burde et al., 2017).

Embedded in the humanitarian paradigm, education in crisis programmes has gained prominence in recent decades as a key component of humanitarian responses. This is in recognition of the potential of education to offer lasting solutions to conflicts by humanitarian workers, that could culminate in improving the lives and opportunities of those displaced (INEE, 2010; Versmesse et al., 2017; Zakharia and Menashy, 2020). These efforts have been reinforced by conventions such as the 1989 Convention on the Right of the Child which emphasised protecting the rights of all children, including educational rights. Besides offering a return to familiar routines, especially for children and youth, education interventions in humanitarian contexts mitigate the psychosocial impact of violence and displacement (Bernhardt et al., 2014; Burde et al., 2017; Versmesse et al., 2017; Lasater et al., 2022).

Even though investment in EiE and the packaging of education as a service like other humanitarian interventions has increased both in funding and awareness of its importance, serious gaps remain. Education interventions in such contexts are faced with profound challenges that include missed essential-foundational education, traumatised learners, a considerable gender gap, understaffed and primarily poorly trained teaching staff, and limited learning resources (Brown, 2001; Oh and van der Stouwe, 2008; Milner and Loescher, 2011; UNESCO, 2015; Flemming, 2017). In sum, these challenges impact the implementation quality of any education interventions in such contexts as the Dadaab refugee camp.

Developed in 2004 and revised in 2010 by INEE, the minimum standards for education aim to promote the “quality of educational preparedness, response, and recovery, increase access to safe and relevant learning opportunities, and ensure accountability in providing these services” in crisis contexts. The standards are meant to facilitate coordination in humanitarian response and ensure that besides quality, the educational rights and specific learning needs of the affected are categorised and addressed separately from development activities (INEE, 2010, p. 4; Burde et al., 2017). The standards are clustered into five domains: foundational standards, access and learning environment, teaching and learning, teachers and other education personnel, and education policy.

The foundational standards concern the inclusive participation of the affected refugee community when evaluating their learning needs, identifying resources within the community that are useful for enforcing age-specific learning opportunities and having in place education coordination mechanisms to support identified interventions' implementation (INEE, 2010; Shah, 2015). They also address the timely and holistic assessment of the in-emergency educational needs, laying out inclusive response strategies, and allowing for monitoring and evaluation mechanisms that aim to improve the specific education response and intervention (Crisp et al., 2001; INEE, 2010; Nicolai et al., 2015).

The access and learning environment standards aim at facilitating equal access to relevant quality education by all communities in a crisis (INEE, 2010). Research shows that conflicts lower access to quality education (Lai and Thyne, 2007; Burde et al., 2017). Beyond accessing learning opportunities, the standards outline the need to secure the learning environment and enhance the protection and wellbeing of learners, teachers, and other personnel supporting an educational intervention (Crisp et al., 2001; INEE, 2010; DeJong et al., 2017; Nakeyar et al., 2017). In addition, the learning facilities should be sufficient and safe for use by learners, teachers, and other education personnel (INEE, 2010).

Standards in the teaching and learning domain entail promoting effective classroom teaching and learning. The host country's education curriculum should be relevant and adaptable to all learners and have the capacity to respond to refugee learners' social, cultural, and linguistic formal and non-formal educational needs (Rutter, 2003; INEE, 2010; UNHCR, 2012; Cohen, 2020). Besides ensuring that classroom instruction and learning processes are both inclusive and student-centred, continuous training and developmental support should be accessible to both teaching and non-teaching staff (Crisp et al., 2001; Taylor and Sidhu, 2012; Lasater et al., 2022), in addition to embracing proper and suitable methods for assessing learning outcomes (INEE, 2010).

The teachers and other education personnel standards address human resources in conflict contexts. The recruitment process of teachers and other education personnel should not only be transparent and inclusive, but those hired should also be sufficient in number and with appropriate qualifications (INEE, 2010; OECD, 2019), possibly including competencies to teach diverse and potentially vulnerable refugee learners (Oh and van der Stouwe, 2008; Miller et al., 2017). Teaching and non-teaching staff should have well-defined terms of engagement with appropriate renumeration and functioning support and supervision mechanisms such as sufficient teaching and learning materials, psychosocial support, and regular feedback from students (Brown, 2001; INEE, 2010; Soares et al., 2021).

The education policy standards pivot on formulating appropriate laws and policies and their implementation. The national governments' laws and policies should support the rights of the refugees to education and the diversity of their learning needs (Crisp et al., 2001; Essomba, 2017). In addressing the learning needs of the refugee population, the standards emphasise recovery and continuity of quality education in conflict contexts and prioritise adherence to both international and national laws, policies, and standards of education (INEE, 2010; UNESCO, 2012).

Overall, while providing guidance on best practises for implementing education in humanitarian and/or fragile contexts, each domain in the INEE minimum standards acknowledges the existence of discrimination and highlights it as a barrier to providing quality education to the refugee community worldwide. The framework places emphasis on the need for educational interventions to include mechanisms mitigate different forms of discrimination. In recognition of the adverse effects of the different forms of discrimination (Dryden-Peterson, 2011; Stark et al., 2015; Nakeyar et al., 2017), this study goes beyond the recommendations of the standards to specifically differentiate the forms of discrimination in schools in such contexts, as a key basis for developing models to understand and mitigate them.

Discrimination is a multifaceted phenomenon that may occur at various levels; at the individual level where the behaviour of individual members of one group in terms of race, ethnicity or gender has adverse effects on another group, and at the institutional level where the policies of institutions and the behaviour of the dominant group in terms of race, ethnicity or gender have adverse effects on the minority group, or at the structural level where the implementation of institutional policies and the behaviour of the implementing individuals have a negative impact on the minority groups (Pincus, 2019). Studies around the world show that schools where refugee youth attend, are potential spaces for racial, ethnic, linguistic, religious, gender, or other forms of discrimination (e.g., Dryden-Peterson, 2011; Correa-Velez et al., 2015; Stark et al., 2015; Nakeyar et al., 2017; Keles et al., 2018; OECD, 2019). For the case of Burmese refugees in Thailand's refugee camp, Oh and van der Stouwe (2008) found that inclusion is interpreted as the absence of discrimination. However, they argue that discrimination goes beyond this narrow scope to include the more fundamental aspects of access, quality, and relevance of refugees' education.

When embedded within education programmes, discrimination undermines the opportunities of refugee youth to achieve their full potential and are more likely to experience life-long socio-economic marginalisation (Save the Children, 2014). Further, refugee youth who experience daily hassles such as discrimination over time have poorer wellbeing and health (Correa-Velez et al., 2015; Stark et al., 2015; Nakeyar et al., 2017), more deficient coping skills (Keles et al., 2018), and lower self-worth with tendencies to withdraw from school (Stark et al., 2015). Consequently, they struggle with social, cultural, and academic adjustment processes (Dryden-Peterson, 2011; Nakeyar et al., 2017; Keles et al., 2018), which may be worse for refugees in low-income country contexts (Stark et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2020). The implementation of educational interventions in emergency contexts should incorporate holistic inclusion approaches that protect the refugee youth from the different forms of discrimination. However, fewer studies have examined the types of discrimination experienced by refugees in educational interventions in refugee camp contexts such as Dadaab. The current study, therefore, further explores the forms of discrimination experienced in the YEP intervention implementation.

The present study draws from the two frameworks to frame the methodology and analysis that focuses on the implementation of the YEP. The YEP intervention breaks away from the traditions of EiE and paves the way for new educational opportunities for refugee youth who cannot fit in basic primary and secondary education programmes (Shah, 2015; Flemming, 2017). This study qualitatively evaluates the implementation quality of the YEP intervention and further, explores the types of discrimination experienced by refugee youth during the intervention implementation. The two research questions are:

• How is the YEP education intervention implemented through the lens of the INEE minimum standards for education framework?

• What types of discrimination are experienced in the YEP intervention implementation?

This section of the study highlights the choice of a case study design and provides an in-depth overview of the YEP intervention, study participants, tools, ethical considerations, and analytical approach.

We adopted a case study design approach because this study primarily focused on evaluating an intervention specifically for youth refugees in a refugee camp context. The refugee camp school contexts in Kenya are not widespread but are limited to two refugee camps, Dadaab and Kakuma (Mendenhall et al., 2015). The qualitative evaluation used interviews and observations to explore the implementation quality of the intervention and potential forms of discrimination experienced by actors in the intervention.

The YEP is an educational intervention designed in 2003 by the Norwegian Refugee Council to address youth educational needs and wellbeing in post-crisis yet fragile contexts. It is modelled to target youth aged 15–24 who have missed out on most schooling due to displacement and limited opportunities. It is thus meant to accelerate their education and development (NRC, 2015). The YEP intervention is a 1-year intensive training programme with three components: the primary being training in vocational skills towards (self)-employment (e.g., motor vehicle mechanics, tailoring and cloth making, journalism, hairdressing and beauty therapy, among other skills). The other two are foundational skills (i.e., basic literacy and numeracy) and transferrable/life skills (e.g., skills in health, art and sports, information technology, and gardening) (Shah, 2015; UNICEF, 2016). While the latter two are mandatory, each learner chooses a vocational skill of interest to enrol in. Moreover, the three integrated components of the intervention aim to rebuild individuals' self-confidence, awareness and coping, reduce violence, and promote communal cooperation and re-integration (Bernhardt et al., 2014; NRC, 2015; UNICEF, 2016).

Since its inception, the YEP intervention has been implemented in several crisis-prone contexts across the globe, such as in Kenya, Myanmar, Afghanistan, Somalia, and the Central African Republic. In Kenya's Dadaab refugee camp, the intervention has been implemented since 2008 in the established four YEP vocational centres, namely Dadaab, Hagadera, Ifo, and Dagahaley.

A total of nine participants were purposively sampled from across the four YEP training centres to participate in the study's interviews (see Table 1). At the time of this study, 610 students were enrolled in the intervention. The students were predominantly refugees of Somali descent, who either attended school for the first time at the YEP centres or had minimal education. The intervention was implemented in English, the curriculum language of instruction in Kenya1. Only refugee students who could fairly express themselves well in English or Kiswahili, the languages of the interviewer, were recruited. The participants were selected to cover the main actors including two students, one enrolled in motor vehicle mechanics and the other in computerised secretarial vocational trades to provide their perspectives of the intervention. Of the three sampled teachers, one taught hairdressing and beauty therapy, the other taught electrical installation trades, and the third teacher was the head of the YEP centre, who coordinated teaching and learning activities. The intervention teachers were predominantly male Kenyan nationals who taught with assistant refugee teachers. The two project administrators supervised the day-to-day implementation of the YEP intervention. Both teachers and project supervisors, as curriculum implementation professionals were key to providing insights and experiences of implementing an education programme in a fragile context. The two former students were sampled from the previous year's YEP cohorts to provide insights that tap into their experiences in the intervention.

The first author conducted in-depth semi-structured interviews with the nine participants in February and March 2016. In light of the fragile context of this study, interviews were used due to their flexibility to be adapted to a wide range of research situations, and their ability to explore people's perceptions, meanings, and construction of reality (Punch and Oancea, 2014). The first author is a Kenyan male teacher with pedagogical qualifications in vocational education and training. The interviews were conducted using four sets of interview guides, each corresponding to the role of the informants and took into consideration the INEE minimum standards (INEE, 2010). Interviews lasted between 30 and 60 min, and they took place at the YEP training centres in Dadaab camps. They were conducted in English and recorded for transcription purposes. The first author conducted observations where he attended several lessons for electrical installation, hairdressing and beauty therapy, computerised secretarial, and motor vehicle mechanics classes. He took notes and asked the participants questions outside the classrooms whenever there was a clarification. Observations were used to supplement interviews and also because of their capacity to allow for behaviour to be observed directly (Bryman, 2016). A semi-structured observation schedule was used. Samples of research tools are included in Supplementary materials.

Before conducting this study, approval was obtained from both Stockholm University and the Kenya National Commission for Science, Technology, and Innovation ethics committees. Due to the sensitivity of information regarding refugees, additional permission was obtained from Kenya's Commission for Refugee Affairs in the Ministry of Interior and Co-ordination of the National Government. Informed written consent was also obtained voluntarily from participants and parents of students considered minors. The participants were assured of the confidentiality of the information and their anonymity. As such, pseudonyms have been used to protect participants' identities.

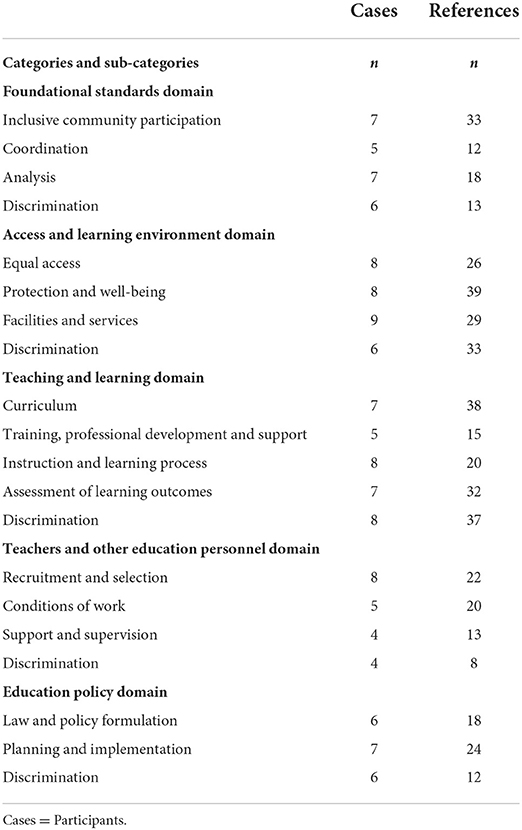

The data analysis process entailed first transcribing all interviews and observation notes. Secondly, a systematic analysis that employed the principles of deductive content analysis was conducted. Considering the aim of this study, themes and sub-themes were developed based on the domains and sub-domains of the INEE minimum standards for education (Elo and Kyngäs, 2008; INEE, 2010; Bryman, 2016). In addition, discrimination, as a sub-theme, was included in each domain. Before attempting to code, the first author read the transcribed interviews and field notes several times. Data were then deductively coded in Nvivo 12 (QSR International, 2020) within the themes and sub-themes (see Table 2), in which results are reported, respectively.

Table 2. Data coding themes and references for five domains of the INEE minimum standards for education.

This study's research questions sought to evaluate the implementation quality of the YEP intervention through the lens of the INEE minimum standards for education framework and highlight the types of discrimination experienced in the YEP intervention implementation.

The findings in this domain address community participation, coordination and analysis and discrimination relating to these three components.

We found that an active Parent Teacher Association (PTA) provided a link between the YEP training centres and the Dadaab refugee camp community that identified learning needs and mobilisation of the youth to enrol and train in the vocational skills offered. Teacher16 highlighted:

We normally elect a PTA who […] helps us with mobilisation. Once the learners come, we take part in their retention because they can come for one week, two weeks, and the third they are not there. So we take part in counselling, mentoring them, and telling them the importance of education because some of the learners who come to the programme have never been to school.

Resources in local communities (i.e., refugee and host communities) were given a priority in the implementation of the YEP intervention; for instance, AdminS23 mentioned that human resourcing exhausted locally available and qualified persons before they considered applicants from outside the locality of the refugee camp, as was stipulated in the design of the intervention. The locals comprised 20% of the YEP personnel. He, however, elaborated that they lacked pedagogically qualified teachers from the local communities, a factor that forced them to employ non-locals in teaching positions.

The UNHCR provided leadership in all educational interventions in the Dadaab refugee camp. AdminS23 noted that contextual guidelines provided by UNHCR coordinated both state and non-state partners such as NRC in addressing the educational needs of refugees. He further explained that NRC mobilised funding for the intervention project and coordinated sourcing of human resources and training materials, besides engaging the UNHCR and the government on intervention implementation policy issues.

We identified a range of the YEP intervention implementation barriers, and strategies to overcome them were laid out. For instance, to encourage and increase the enrolment of female youth, both Teacher21 and AdminS23 mentioned that female youth and single parents were categorised as the most vulnerable group and were thus prioritised during enrolment.

Regular monitoring and evaluation of the skills needed in the refugee community and their relevance were reported. “We do the cross-border assessments, market assessments, and all these are to inform us on the kind of skills to offer. Like out of that, the new journalism course came up”, AdminS25 stated. Teacher21 further highlighted that the evaluation feedback informed them of the kind of saturated skills in the camp. He mentioned an example of tailoring and dressmaking vocation as a saturated skill they were considering scaling down the training on.

Refugee youth reported experiencing discrimination based on how they looked, their language, religion, and refugee status (racial-ethnic discrimination) and were excluded from participation in societal development. Asked about his expectation upon completing the course, Student2 expressed his frustration and pessimism about how his refugee status defined him and his future and made clear that he wanted to return and make a career in his motherland, Somalia, where no one prejudiced him. “Compared to this area [Dadaab-Kenya] even if you are a white man or black man, there is no consideration of colour, mother tongue, and religion”, he stated. Further, he elaborated that the chances of him getting employment in Kenya in the future were not there because of the refugee status that he had held since he was a year old. “Even if I completed Grade III, II, and I engineering,2 I cannot be allowed to work because I will just be told I am a refugee”, he elaborated.

The findings in this domain focus on equal access to education, protection and wellbeing, facilities and services, and discrimination experiences relating to education access and the school environment.

In examining the access to vocational education and training, we found that refugee youth were admitted into the intervention irrespective of whether they had had an education before or not. Besides refugees, AdminS23 confirmed that “up to 5% of the total enrolment” comprised youth from the “host community”. Asked about how flexible it was for the refugee youth to enrol in the YEP training, he elaborated:

We don't have particular entry criteria. Entry-level is open for all students who have been in school or who have dropped out at some level, either primary or secondary, or those who have completed secondary. Even those who have gone to post-secondary, and wish to undertake some skills. So, we don't have any limiting entry-level, but we target an age limit of 15 to 24.

Regarding gender and access to the YEP intervention, the first author observed that most classes at the YEP centres had fewer female than male students during visits to the classrooms. For some, like the electrical installation trade, “all students in the class were of the male gender3”. At one of the YEP centres, the centre supervising Teacher21 confirmed the number of students enrolled: “we have 111 female leaners and 250 male learners”. Curious to understand the enrolment trend and the underlying factors that explained the disparity in gender enrolment, AdminS25 explained that the average ratio was 70% male enrolling and completing and 30% female, which represented “an average ratio for […] 7 years since the YEP started”. In addition, the cultural practise by the refugee community of forcing early marriages on female youth was reported as a reason for their lower enrolment in the intervention. Teacher21 substantiated:

When these girls reach the age of 15, they are married off. In most of these communities […] when a lady reaches the age of 15, she is married to someone without even her consent. The father will give his daughter to the man he likes, and they can't refuse. Even if she was learning, she has to drop out to take care of her husband […]. Like the day before yesterday, a female learner was here, and she said her husband said he is not ready to accept what she is doing here and has to stay at home […]. She has dropped out because of the pressure from her husband.

Study participants cited the lack of sufficient protection and support for wellbeing amidst the security risks and violence in the Dadaab camp which often disrupted learning when they occurred4. AdminS23 mentioned that due to security concerns, their staff worked fewer hours a day than was required and were escorted to and from the YEP centres by the police. “We have security escorts for staff, although not sufficient enough because we have had cases of kidnapping5 and with lack of adequate security, we have had teachers withdraw from Dadaab refugee camp”, he elaborated. Teacher16 confirmed that when the security was worse, the police stayed with them at the YEP training centres.

The majority of students enrolled in the YEP intervention were from conflict zones in Somalia, and they needed support for their wellbeing and health. Student3 narrated that some of his peers found it rough and could not cope with school, and they dropped out. Teacher16 was concerned that even though the International Rescue Committee (IRC) supported the refugee youth with recovery from traumatic experiences, teachers lacked the necessary skills and training to support such students adjust socially and emotionally. He further stated:

As teachers, one of our responsibilities is to provide guiding and counselling services, and we help our students where we can. As for trauma challenges, we do not have the expertise, but I think they can get some help from our partner organisations for health. We lack the training, and there is a need for teachers to be trained more in this area because we spend most of the time with these students.

To enhance social and emotional wellbeing, the YEP intervention incorporated co-curricular activities like sports that helped the youth cope with traumatic and challenging experiences, such as when they felt rejected. All the YEP centres had playgrounds, and Teacher21 mentioned that peers met friends to talk with when they interacted in sporting activities. Student2 and Student3 emphasised the importance of sporting activities such as football competitions as a function that supported and united them as a community. In addition, refugee youth at the camp were from diverse ethnic backgrounds (e.g., Somalis, Congolese, Burundians, Sudanese, and Ethiopians). Student5 explained that the YEP intervention itself was an opportunity for intercultural exchange. “This is where different communities can be able to meet, and they learn each other's culture and exchange ideas, play in football competitions, and that interaction helps promote peace and unity”, he explained.

We further found that the YEP intervention played a crucial role in disengaging the youth from social vices such as violence, drug abuse, theft and burglary, and the risk of being radicalised by members of the militia groups. Both AdminS23 and Teacher21 described these identified risks in the camp among the majority of youth as the main reasons for the design of the YEP intervention. Teacher21 provided some perspective:

Before this programme began, there were so many youths who were out of school doing nothing. They were involved in criminal acts, they used to fight a lot but after this programme was brought some have started their own businesses, some have joined primary schools and secondary schools when they finish this course.

It was observed that the four YEP centres had classrooms and workshops that looked spacious, secure, and conducive to learning. Some of the classrooms visited for observation were overcrowded, but all students had working desks in good condition. The teaching staff at all four centres had a staff room with adequate working space to prepare their teaching6.

The vocational skills workshops at the four YEP centres were equipped to the minimum standards of the training level. AdminS23 remarked that “we have standardised our training facilities to the required training requirements by National Industrial Training Authority (NITA) and the ministry of education, and the organisation has equipped the facilities to that minimum standard […]. They are sufficient to guarantee quality training”. However, it was found that most tools and equipment were either worn out or broken and could not be used for learning purposes. In an electrical installation vocation workshop, it was observed that “the workshop equipment such as the electrical installation mounting boards, […] looked dilapidated due to overuse and required replacement (see text footnote 3). The responsible teacher explained that insufficient funding was why they had not been replaced.

Student2, a student in the motor vehicle mechanic trade, was concerned that the car they used for the training had missing parts, and this hindered them from following the lessons: “the car we use has been used by a lot of people for training, and now some parts are missing, which may make you to fail or not understand”, he said. Similarly, in the tailoring and cloth-making workshop, it was observed that “a number of students were not participating in the sewing practical lesson, because the sewing machines that were being operated were fewer than the number of students”, yet on one side of the workshop, there were sewing machines that were not being used7. Asked why this was the case, Teacher21 clarified: “the machines are there but not in operational condition, they need to be repaired […]. You can find only five machines are working and we have more than 50 learners […] which is a challenge”.

There were no library services at the four YEP training centres. Student2 stated: “we don't have reference books. The teacher will come and teach and finish the lesson, and there is nothing in the lab or like a library that you can go and check”. He further explained: “we don't have a library and we need one like during break you can go and refer”.

The cultural practises of the refugee community discriminated against female youth refugees and denied them equal access to educational opportunities compared to their male counterparts. Both Teacher21 and AdminS23 disappointedly described how female refugee youth experienced gender discrimination at an early age from their parents and older members of their community, who forced them into early marriages. AdminS23 described the impact of the practises; “we have so many young mothers and with early responsibilities of taking care of young children, then most of them don't have time to concentrate in school, and the school-going age surpasses them when they are playing the crucial role of parenthood”.

In the teaching and learning domain, teacher-specific competencies such as curriculum implementation, training and professional development, instruction and learning process, assessment of learning outcomes, and discriminations that pertain to these aspects of the domain are discussed.

AdminS23 reported that in the YEP intervention, they adopted and used the curriculum approved by the Kenyan government. Before implementing the intervention, suitable learning needs for refugee youth aged 15–24 were identified, including 13 skills broadly categorised as “construction, transport, ICT and communication, […] and consumer services”. AdminS25 provided examples of relevant vocational skills offered to youth: “In this centre, Hagadera, where we are today, we have motor vehicle mechanics, electrical, computer secretarial, journalism, tailoring and hair and beauty. On the other side, we have plumbing, welding and fabrication, food and beverage”.

The curriculum materials such as books suited for refugee youth enrolled in the YEP intervention were reported to be missing. A few that were available were too advanced for students, some of whom were entering school for the first time, and hence did not address their diverse needs. “The books that are there on the market are not meant for this kind of learners. I think they need simpler books. The reference books being used are advanced for them”, remarked Teacher16. AdminS23 reported efforts to develop relevant books and learning materials in the Somali language. “We are also partnering with UNICEF and the Somali government ministry of education to have most of the materials we have translated into the Somali language”.

We found that essential components in the curriculum implementation for vocational skills were lagging, i.e., entrepreneurship and apprenticeship. AdminS23 described entrepreneurship on the one hand as a critical part of the syllabus. He noted that “entrepreneurship […] is offered as a training course within vocational skills. However, we have several challenges that come with that. One is the literacy level of learners and the level of entrepreneurship course that we are offering”. Teacher16 stated that they could not cover it as required, even though it was relevant because employment opportunities in the camp were few and hence, they aimed to prepare the youth for self-employment. Due to context, on the other hand, the youth were offered internships instead of apprenticeships, which were also broadly not accessible. Student3 reported having had a three-month internship, in which he said he learned most of the competencies. Student5 said that he never had a chance to learn the skills on the job. Teacher16 explained that it is challenging to get institutions that can offer internships or apprenticeships in a camp set up, a perspective that AdminS23 acknowledged:

Apprenticeship is part of the training curriculum for vocational skills training designed by the Kenya Institute of Curriculum Development. So, there is a period where students are allowed to go for attachment [placement for internships8] as much as it has not been emphasised here for contextual reasons, whereby we don't have established attachment institutions. So, the programme has not been strengthened due to the lack of those kinds of institutions that can facilitate it.

However, Teacher16, Teacher21, and AdminS23 reported that they had completed mapping of business enterprises in the region that could offer internships to their students and were in the process of agreeing with them.

Teachers and supervisors were asked about the YEP intervention's training and professional development support. AdminS25 stated that they offered on-job training for refugee teachers recruited in the camp, who did not possess any pedagogical qualifications. He explained that refugee teachers would typically “work under qualified Kenyan teachers for on-the-job training and help with translation as they learned how to teach”. He clarified that they sponsored the refugee teachers for further training depending on funding availability.

Teacher16, however, pointed out a stark lack of in-service teacher training and support for the 4 years he had worked in the YEP intervention. For instance, he pointed out that teachers were expected to offer emotional support to their students, who suffered from trauma after being in conflict-hit zones, but they did not have the necessary skills to help them. He cited the exclusion of teachers in the staff development programme notwithstanding their crucial role. He remarked:

You come here for four years, and you don't go for any training; the knowledge you came with is what you continue using. Sometimes the line managers are the only ones taken for this [training], and yet they don't deal with the beneficiary [refugee students] directly.

In a follow-up interview with the supervisors, AdminS23 acknowledged the lack of in-service teacher training and the need to reactivate the teacher development programme. He stated that “we have a programme for teacher development which is underfunded. It has not been active for a while […], but it is there, which is meant to improve teachers' ability to respond to the training needs contextually in our programme”.

The first author observed classroom instruction and the learning process and found that lessons began on time and that students went to class prepared. During lessons, teachers demonstrated understanding of the content and competency in classroom instruction. During an electrical installation lesson, like other lessons attended for observation, the first author observed that “there were two teachers in the workshop; the primary course teacher [Teacher16] and the assistant teacher who translated for the primary teacher from English to the Somali language (see text footnote 3). Both teachers made an effort to engage with and support the students during the lesson. During a practical work session, students worked in groups of two. Teachers were at hand to guide them, and students successfully built simple electric circuits. Responding to the question of how they dealt with language hassles to include all students in the learning process, AdminS23 said:

We have tried to have two teachers in every skill. Because of the context demands, the key teachers are non-Somali speaking, and […] we have given them an assistant teacher who is Somali speaking. So they help in the translation of the content, which closes the gap of the language barrier.

A visit to Teacher17's hairdressing and beauty therapy workshop confirmed the availability of just two hair driers used by about 25 students in her class. As to how she ensured that all students had equal learning opportunities, she explained: “I train students in turns after grouping them. It may take 1 or 2 weeks to take the learners through the usage of the machines, but I manage”. Similarly, in an active tailoring and cloth-making class, the first author observed students working with sewing machines in turns. Teachers were supportive, and “students could skilfully cut materials into required shapes and safely operate the sewing machines as instructed by their teachers (see text footnote 7).

Concerning whether appropriate methods were used to evaluate learners in the YEP intervention, we found that a holistic approach was used for assessing learning outcomes. Student3 and Student5 confirmed that they participated in a series of assessments when they were students. Student5 described that “we normally do exams and Continuous Assessment Tests (CAT). […] In the first term, we have CAT 1, CAT 2, and CAT 3, then we have the end-of-term exam. After we have finished, after 12 months, we do our final year exam, which is from outside YEP”. AdminS25, AdminS23, Teacher16, and Teacher21 confirmed Student5's insights. They further confirmed that the NITA issued students certificates upon completing the vocational training programme. AdminS23 clarified further:

We have two examiners; one is the […] NITA and the second one is the Northeastern Training College which is a government training institution that offers similar training courses to the ones we are doing. Since it offers training at a slightly higher level, it does the examining and certification of our learners.

Teacher16 and AdminS23 further clarified that because of linguistic challenges and for an inclusive and fair assessment, the YEP students' examinations comprised 80 per cent practical work and 20 per cent oral and written work.

Language discrimination was reported in the implementation of the YEP intervention. The students had difficulties understanding English, the language of instruction in class, which made schooling harder for them. The youth were introduced to English language learning while enrolled in the intervention. Learning through a translator was not the only option, but they had to do with it, even after NRC had implemented the intervention for over 8 years.

We also found discrimination in the books used for the curriculum implementation. The books did not reflect the learning needs of the refugee youth, and requests to develop relevant reference books had not been honoured by the relevant Kenyan education authority. Student3 acknowledged that it was difficult to be provided with everything in a refugee camp set-up, but helpful syllabus books that were easy to understand were important for students.

Some organisations working in the Dadaab refugee camp were reported to discriminate against refugees and view them as security threats. When asked why it was challenging to secure internships for refugee students with the organisations working in the camp, Teacher16 explained that their students were subjected to a complex vetting process that made it impossible to secure internships for learning purposes. “When it comes to the agencies, most of them don't want these people for security reasons. If they have to involve them [refugee students], they have to be vetted and verified. So, the organisations are not that co-operative”, he explained. He further suggested that “they [the organisations] should be told that even if they are refugees, they can't be so dangerous, they need to learn”.

The key areas that this section reports on include the recruitment of teachers, conditions of work, and support and supervision accorded to personnel. Types of discrimination experienced by teachers and other educational personnel are also reported.

The staff recruitment process was reported to adhere to the NRC's human resource procedures. “We follow the organisational human resource policies depending on the kind of recruitment, whether we need a Kenyan national staff or a local refugee staff”, explained AdminS25. A rigorous procedure was followed to hire competent personnel to work in the YEP intervention. AdminsS23 further detailed:

We advertise based on the requirements for the skill we want to recruit a teacher for. Once the position is advertised, we screen the applications and conduct interviews at three levels; the practical part where the teacher demonstrates his knowledge of the skill. Then we also do oral interviews to understand the person and written interviews.

Regarding whether teachers employed needed to have pedagogical training or not, both AdminS23 and AdminS25 confirmed that it was a requirement. “It is a mandatory requirement, for example, if we are looking for a trainer in automotive mechanics, a person must have a diploma in automotive mechanics and must have a diploma in technical teacher training”, AdminS25 clarified. However, this requirement did not apply to assistant refugee teachers who hardly had such qualifications to enhance inclusion. AdminS23 explained that:

If we look at the key-skill teacher whose entry level is higher as per the required standard of the ministry of education and our examiner, they must have an education component. But if we look at the assistant teacher, those are people we are recruiting to be mentored. As we provide them with pedagogical skills training, we mentor them to stand in as teachers.

Teacher16 and Teacher17 confirmed holding diplomas in their respective vocational skills and pedagogy.

It emerged, however, that the YEP intervention was understaffed in terms of teaching personnel. “For example, in this class, we have lacked a teacher for 2 months”, TeacherH21 stated about the computer hardware and repair course at the centre he supervised. Teacher16 talked about his harrowing experience of teaching without a translator. “Not every time you have an interpreter, like last year I taught a whole year without one, and sometimes learners would demonstrate like for two days and come back since they don't understand in class”, he explained. AdminS23 acknowledged the understaffing of teachers and highlighted that it contradicted the required standards and undermined the quality of the intervention implementation. He further mentioned that the student-teacher ratio in the YEP intervention was 38:1, higher than the recommended ratio of 25:1 for vocational skills. He attributed this to higher staff turnover due to insecurity and dynamics in the refugee community. The “turnover ratio for refugee teachers is so high because of the aspect of repatriation, resettlement and going back home”, he explained.

Teachers' responsibilities were clearly defined even though their skills were limited in some areas, such as student support and entrepreneurship, which they said needed training. In terms of renumeration, Teacher17 mentioned that she was okay with her renumeration, while Teacher16 highlighted lower renumeration for teachers as a source of demotivation. “Compared to other employees in this region, they [teachers] are the lowest paid. They should be motivated”, he said. His perspective was shared with AdminS23, who cited lower compensation packages as a factor that kept away more competent teachers from working in the YEP intervention. “The compensation of good quality teachers is also an issue that makes the teacher position not attractive for competent people”, he stated.

The teachers confirmed that students had enough writing and practical lesson materials. Teacher17 reported that the learning materials she requested for her classes were adequate and that she would always improvise in case of a shortage. However, Student4 pointed out that they did not have access to reference books. Her concern concurred with that of Student2, who said, “we don't normally get textbook material support, so I also request NRC to provide us with textbooks for the syllabus”. Asked about why this was the case, Teacher16 remarked: “don't ask about that because they don't know how to read. It's only the teacher who uses that book and one or two learners, and when you give them, they just look at the pictures”. AdminS23 explained that the training is more skill-oriented and essentially involves project activities. He further clarified that:

The reference materials are expensive because, for example, the essential reference book goes for Ksh. 5,000 a unit. Considering 700 students, then it is not easy to achieve that. We have books that are under the custody of the teacher and who directs how they need to be used.

Teachers recounted their challenges that suggested the need for attention and support. For instance, Teacher17 described her unpreparedness for the culture, context, and challenges of the teaching process where a translator mediated the teacher's language and that of the learner. For Teacher16, teaching a whole year without a translator to students who did not understand English was stressful, especially when the youth staged demonstrations with genuine concern about not understanding in class.

Refugee teachers experienced discrimination in terms of wage compensation. They worked as much as the primary teachers, but they earned a mere incentive since the Kenya government's labour laws did not allow them to work. AdminS23 explained that their lower wages and a huge income gap between them and the primary teachers were somewhat linked to their high turnover rate.

Findings under the education policy and domain focus on law and policy formulation, planning and implementation, and their related discrimination.

The government lawfully facilitated non-governmental organisations such as NRC to establish EiE in the Dadaab camp. The national security agencies protected the established education facilities that implemented the Kenyan education curriculum. However, the encampment policy enforced by the Kenyan government was found to hinder the full implementation of the YEP intervention. The youth were not allowed free movement outside the camp that Teacher21 described as having cut off apprenticeship as a part of the training process. “They don't have that free movement and reception in all institutions that are around the country where they can go for attachment. So, […] they are limited to do all their training and learning within the camp”, AdminS23 highlighted.

The implementation of the YEP intervention was found to be integrated with other emergency response sectors such as healthcare, sanitation, and food services. The Kenya education institutions like the NITA and the Northeastern Training College provided examination and certification services to the YEP students. Even though it was the responsibility of Kenya's ministry of education to monitor and evaluate the curriculum implementation quality of the YEP intervention, these services were reported to be lacking. AdminS23 provided insight: “the government's monitoring system is not very consistent, they don't bring new ideas on how we should implement, so their monitoring and feedback process if not poor, it's not there. They solely rely on us to do everything the way we understand it best”.

The encampment policy practised by the Kenyan government structurally discriminated and excluded the refugee youth from fulfilling their learning needs. The policy barred the youth from free movement out of the camp and hence denied them the much-needed learning opportunities not available in the camp, such as access to institutions and industries for apprenticeships and internships, a core component of vocational skills training. AdminS23, Teacher17, Teacher16, and Teacher21 underscored that the policy largely undermined the YEP intervention implementation quality.

The YEP is a vital intervention that responds to the educational needs of the refugee youth and provides a pathway for vocational skills training in protracted humanitarian contexts that are difficult to implement learning. The findings of this study contribute to the literature on education in humanitarian contexts and provide suggestions for improving the quality of implementing YEP intervention. Even though the INEE minimum standards were implemented extensively in the YEP intervention, contextual challenges undermined the implementation quality, which, when addressed, may significantly improve the effectiveness of the intervention in terms of the quality of the training process and the transfer of skills. Generally, the intervention is severely underfunded and requires more resources to realise the desired implementation quality. The refugee youth also experience a range of discrimination types reflected in the quality of their education and development.

The starkly lower access to the YEP intervention, especially by female refugee youth due to underfunding and discriminatory cultural practises (also see Mendenhall et al., 2015; NRC, 2015; Flemming, 2017), could perhaps be improved by mechanisms such as community awareness engagements on gender, education, and inclusion. Perceived gender discrimination is linked to gender-based violence and poor health among refugees (Berthold, 2000; Murray and Achieng, 2011; UNHCR, 2012; Hamad et al., 2021). Appropriate interventions that focus on minimising gender discrimination effects among female youth and raising community awareness on the importance of educating female members of the society and their retention in schools are needed in the Dadaab refugee camp (Gichiru and Larkin, 2009).

The teachers worked in a challenging humanitarian context and with students who potentially had difficult experiences both in and outside the camp's school context. Such conditions may have far-reaching adverse effects on the wellbeing of both teachers and students over time, and more so on the quality of teaching (Oh and van der Stouwe, 2008; Dryden-Peterson, 2015; Burde et al., 2017; DeJong et al., 2017). There is a need for more funding to support the in-service teacher training and development that should focus on increasing their capacity in terms of resilience, competency, and psychosocial support skills for their personal growth and that of their students (Taylor and Sidhu, 2012; Mendenhall et al., 2015; Soares et al., 2021; Lasater et al., 2022). Further, support for further education of resourceful refugee teachers to qualify as full-fledged teachers would offer secure and long-term solutions.

It was important that refugee youth had access to literacy classes and were taught English, the curriculum's language of instruction. However, the severe language hassles experienced by refugee youth resulted from the organisational challenges and probably limited funding to separate the concurrent language learning and vocations training. A link between language competency and academic success among the youth of refugee and foreign backgrounds is established (e.g., Taylor and Sidhu, 2012; Morris and Maxey, 2014; Bryman, 2016). The intervention design should be reviewed to allow refugee youth to learn the language first before enrolling in various vocations.

Regarding the curriculum implementation, firstly, the integration of the YEP intervention with other emergency response actors like healthcare agencies adhered to the design and standards (INEE, 2010; NRC, 2015). Secondly, the quality assurance of the curriculum implementation was, however, not provided. The fact that the YEP implementors did not know whether the curriculum was being implemented as was required had ramifications on the quality of the refugee youth's education (INEE, 2010; Talbot, 2013; MacKinnon, 2014). Thirdly, the books for implementing the curriculum in the YEP intervention did not reflect the learning needs of refugee youth. The youth must be provided with sufficient and easily comprehensible books. The design of books and learning materials should reflect the content relevance and identity of the refugee youth (Crisp et al., 2001; Shah, 2015). Fourthly, when most tools and equipment are either broken or worn out, as was observed in the YEP workshops, it contributes to lower-quality training and poorer learning outcomes (Coates, 2009). Support in terms of funding is needed to overhaul the tools and equipment for quality training. In sum, further engagement with Kenya's ministry of education is required to ensure quality control measures for curriculum implementation are in place, and perhaps if these mechanisms were functionally in place, the challenges of books, learning materials, and apprenticeships, as sources of educational discrimination for the youth would be lower.

To fully implement the YEP intervention, there is a need to review the Kenyan government encampment policy. For any education to protect refugees, it must be of high quality. Refugee-hosting countries have a role in guaranteeing it and integrating the youth into the socioeconomic system (Dryden-Peterson, 2011). For instance, apprenticeship as a resource is central for integrating learning and work and is linked to the mastery of work skills and employability (Picchio and Staffolani, 2019; Ashman et al., 2021), including among refugee youth (Women's Refugee Committee, 2011). The encampment policy should be reviewed to allow free movement of refugee students such as those enrolled in the YEP to apprentice in institutions and industries outside the camp and even study further at more competent education institutions in the country. This will contribute to building the needed capacity of skilled human resources among the refugee community. The other way would be to grant temporary work permits to the refugee teachers and other resourceful refugee personnel involved in refugees' development programmes. This is important because they would be eligible to earn a salary and hence be better compensated like other non-refugee humanitarians in the camp. In addition, these measures would help lower the structural discrimination in terms of lower quality training for refugee youth that result from their discriminatory isolation and restriction in the bounds of the camp that does not have relevant education and from the discriminatory compensation among the refugee teachers.

Refugee youth recounted the experience of racial-ethnic and religious forms of prejudice. Racial-ethnic and religious discrimination is common among refugee youth (Oh and van der Stouwe, 2008; Correa-Velez et al., 2015; Keles et al., 2018) and has the potential to cause harm to their physical health, psychological, and academic wellbeing (Stark et al., 2015; Nakeyar et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2020; Lasater et al., 2022). Perhaps including interventions that focus on strengthening cultural identity ties may help reduce the effects of such forms of discrimination (Kunyu et al., 2021). Notably, more data on these forms of discrimination and their effects among encamped refugee youth would help improve the design of interventions.

In evaluating the implementation quality of the YEP intervention, the present study has explicitly highlighted the strengths and contextual gaps in the intervention. In addition, various forms of discrimination experienced in the school context by refugee youth in Dadaab are highlighted. Importantly, however, the study provides vital recommendations for mitigating the challenges and supporting the improvement of the quality of the YEP intervention implementation.

A notable strength of this study is that given limited empirical research focusing on the implementation quality of education interventions in humanitarian contexts, to our knowledge, it is one of the first to evaluate the YEP intervention using the comprehensive INEE minimum standards framework. The study also utilises multiple respondents in the YEP implementation process: students, former students, teachers, and supervisors who offered diverse insights into the YEP implementation. This study, however, had some limitations. It was conducting the interviews in English that limited participation of especially students and former students to those who could reasonably speak English. It is possible that, as such, important information was not collected from this group of participants due to limited language skills. Furthermore, the data collection process could have utilised Somali-speaking enumerators to include more participants in the study and minimise the language barrier. Perhaps this could have also contributed to the collection of richer data.

Future studies that focus on an in-depth evaluation of each domain of the standards with a higher sample of both qualitative and quantitative data are desired. This will be vital for proposing specific policy action plan activities for various actors and stakeholders involved in the educational programming for refugee youth in Dadaab. Further, a more in-depth investigation into the specific forms of discrimination experienced by the refugee youth, and the extent of their effects on learning outcomes and wellbeing is needed. In addition, studies that go beyond to focus on exploring protective factors and mechanisms against the different forms of discrimination are desired to inform the design of context-specific interventions.

In conclusion, education actors need to assess the unique challenges of each humanitarian context and incorporate them into the design of educational programmes for the youth. Since financing education in such contexts is mainly dependent on donors, it is vital to ensure that the scale of the intervention remains within the limits of the available financial resources. This is vital to ensuring that the intervention guarantees the refugees high-quality education. Moreover, interventions targeting refugees should incorporate strategies for more substantial social and emotional support because, besides being a vulnerable group, refugee youth are faced with an array of discrimination experiences.

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because of the sensitivity of the research population. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to DK: a2hpc29uaUB1bmktcG90c2RhbS5kZQ==.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Kenya National Commission for Science, Technology, and Innovation; Stockholm University. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants or where applicable, their legal guardian/next of kin.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

The publication of this article was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) - Project Number 491466077.

The authors thank James Sifuna for his logistical support during data collection in the Dadaab refugee camp.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organisations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fhumd.2022.898081/full#supplementary-material

1. ^Even though English was the language of instruction, students were at a beginner's level and did not have sufficient English language competencies. They spoke Somali language.

2. ^Grades III, II, and I refer to the training qualifications and certification levels for the various vocational trades as provided for in Kenya's education curriculum for vocational education and training. Grade III is the beginner's level while Grade I is the highest (Ministry of Education, 2013).

3. ^Observation notes, Dadaab Refugee Camp, February 26, 2016.

4. ^AdminS23; Student2; Student3; Teacher16; Teacher21.

5. ^In 2012, four NRC staff were abducted and several wounded in an attack in the Dadaab refugee camp by members of the Al-Shabaab militia group from Somalia (NRC, 2017).

6. ^Observation notes, Dadaab Refugee Camp, March 3, 2016.

7. ^Observation notes, Dadaab Refugee Camp, February 29, 2016.

8. ^The term “attachment” as used by interview respondents in this article refers to placement for internship.

Ashman, K., Rochford, F., and Slade, B. (2021). Work-integrated learning: the new professional apprenticeship? J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pract. 18, 5. doi: 10.53761/1.18.1.5

Bensalah, K. (2002). Guidelines for Education in Situations of Emergency and Crisis. Paris, France: UNESCO.

Bernhardt, A. C., Yorozu, R., and Medel-Añonuevo, C. (2014). Literacy and life skills education for vulnerable youth: what policy makers can do. Int. Rev. Educ. 60, 279–288. doi: 10.1007/s11159-014-9419-z

Berthold, S. (2000). War traumas and community violence: psychological, behavioral, and academic outcomes among khmer refugee adolescents. J. Multicult. Soc. Work 8, 15–46. doi: 10.1300/J285v08n01_02

Birman, D. B., and Tran, N. (2017). When worlds collide: academic adjustment of Somali Bantu students with limited formal education in a U.S. elementary school. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 60:132–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2017.06.008

Brown, T. (2001). ”Improving quality and attainment in refugee education: the case of bhutanese refugees in Nepal,” in Learning for a Future: Refugee Education in Developing Countries, eds J. Crisp, C. Talbet, and D. B. Cipollone (Geneva: UNHCR), 109–162.

Burde, D., Kapit, A., Wahl, R. L., Guven, O., and Skarpeteig, M. I. (2017). Education in emergencies: a review of theory and research. Rev. Educ. Res. 87, 619–658. doi: 10.3102/0034654316671594

Coates, H. (2009). Building quality foundations: indicators and instruments to measure the quality of vocational education and training. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 61, 517–534. doi: 10.1080/13636820903326532

Cohen, E. (2020). How Syrian refugees expand inclusion and navigate exclusion in Jordan: a framework for understanding curricular engagement. J. Educ. Muslim Soc. 2, 3. doi: 10.2979/jems.2.1.02

Correa-Velez, I., Gifford, S. M., and McMichael, C. (2015). The persistence of predictors of wellbeing among refugee youth eight years after resettlement in Melbourne, Australia. Soc. Sci. Med. 142, 163–168. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.08.017

Crisp, J., Talbot, C., and Cipollone, D. (2001). Learning for a Future: Refugee Education in Developing Countries. Geneva: UNHCR.

Deane, S. (2016). Syria's lost generation: refugee education provision and societal security in an ongoing conflict emergency. IDS Bull. 47, 35–52. doi: 10.19088/1968-2016.143

DeJong, J., Sbeity, F., Schlecht, J., Harfouche, M., Yamout, R., Fouad, F. M., et al. (2017). Young lives disrupted: gender and well-being among adolescent Syrian refugees in Lebanon. Confl. Health 11, 25–34. doi: 10.1186/s13031-017-0128-7

Dryden-Peterson, S. (2015). Refugee education in countries of first asylum: breaking open the black box of pre-resettlement experiences. Theory Res. Educ. 14, 131–148. doi: 10.1177/1477878515622703

Elo, S., and Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 62, 107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

Essomba, M. À. (2017). The right to education of children and youngsters from refugee families in Europe. Intercult. Educ. 28, 206–218. doi: 10.1080/14675986.2017.1308659

Flemming, J. (2017). Case Study Report: Norwegian Refugee Council, Dadaab, Kenya. Amherst, MA: Center for International Education, University of Massachusetts.

Gichiru, W. P., and Larkin, D. B. (2009). ”Reframing refugee education in Kenya as an inclusionary practice of pedagogy,” in Beyond Pedagogies of Exclusion in Diverse Childhood Contexts, eds S. Mitakidou, E. Tressou, B. B. Swadener, and C. A. Grant (New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan), 225–240.

Hamad, B. A., Elamassie, S., Oakley, E., Alheiwidi, S., and Baird, S. (2021). No one should be terrified like I was!' Exploring drivers and impacts of child marriage in protracted crises among Palestinian and Syrian refugees. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 33, 1209–1231. doi: 10.1057/s41287-021-00427-8

INEE (2010). INEE Minimum Standards for Education: Preparedness, Response, Recovery. Ebook. 2nd Edn. New York, NY: INEE.

Kelcey, J., and Chatila, S. (2020). Increasing inclusion or expanding exclusion? How the global strategy to include refugees in national education systems has been implemented in Lebanon. Refuge Canadas J. Refugees 36, 9–19. doi: 10.25071/1920-7336.40713

Keles, S., Friborg, O., Idsøe, T., Sirin, S., and Oppedal, B. (2018). Resilience and acculturation among unaccompanied refugee minors. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 42, 52–63. doi: 10.1177/0165025416658136

Kim, H. Y., Brown, L., Dolan, C. T., Sheridan, M., and Aber, J. L. (2020). Post-migration risks, developmental processes, and learning among Syrian refugee children in Lebanon. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 69, 101142. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2020.101142

Kunyu, D. K., Juang, L. P., Schachner, M. M., and Schwarzenthal, M. (2021). Discrimination among youth of immigrant descent in Germany: do school and cultural belonging weaken links to negative socio-emotional and academic adjustment?. German J. Dev. Educ. Psychol. 52, 3–4. doi: 10.1026/0049-8637/a000231

Lai, B., and Thyne, C. (2007). The effect of civil war on education, 1980-−97. J. Peace Res. 44, 277–292. doi: 10.1177/0022343307076631

Lasater, M. E., Flemming, J., Bourey, C., Nemiro, A., and Meyer, S. R. (2022). School-based MHPSS interventions in humanitarian contexts: a realist review. BMJ Open 12, e054856. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-054856

MacKinnon, H. (2014). Education in Emergencies: The Case of Dadaab Refugee Camps. New York, NY: Centre for International Governance Innovation.

Mendenhall, M., Dryden-Peterson, S., Bartlett, L., and Ndirangu, C. (2015). Quality education for refugees in Kenya: Pedagogy in urban Nairobi and Kakuma refugee camp settings. J. Educ. Emerg. 1, 92–130. doi: 10.17609/N8D08K

Miller, E., Ziaian, T., and Esterman, A. (2017). Australian school practices and the education experiences of students with a refugee background: a review of the literature. Int. J. Inclusive Educ. 22, 339–359. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2017.1365955

Milner, J., and Loescher, G. (2011). Responding to Protracted Refugee Situations: Lessons from a Decade of Discussion. Oxford: Refugee Studies Centre, University of Oxford.

Ministry of Education. (2013). The Technical and Vocational Education and Training Act, 2013. Nairobi: Government Printer.

Monaghan, C. (2021). Educating for Durable Solutions: Histories of Schooling in Kenya's Dadaab and Kakuma Refugee Camps. London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

Monaghan, C., and King, E. (2018). How theories of change can improve education programming and evaluation in conflict-affected contexts. Comp. Educ. Rev. 62, 365–384. doi: 10.1086/698405

Morris, M., and Maxey, S. (2014). The importance of english language competency in the academic success of international accounting students. J. Educ. Bus. 89, 178–185. doi: 10.1080/08832323.2013.819315

Murray, S., and Achieng, A. (2011). Gender-Based Violence Assessment: Hagadera Refugee Camp, Dadaab, Kenya. International Rescue Committee.

Nakeyar, C., Esses, V., and Reid, G. J. (2017). The psychosocial needs of refugee children and youth and best practices for filling these needs: a systematic review. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 23, 186–208. doi: 10.1177/1359104517742188

Nicolai, S., Hine, S., and Wales, J. (2015). Education in Emergencies and Protracted Crises: Toward a Strengthened Response. London: Overseas Development Institute.

NRC (2015). Strategic Research into the Youth Education Pack Model. Oslo: Norwegian Refugee Council.

NRC (2017). The 2012 Dadaab Attack: A Follow-Up on Our Staff and Organisational Learning. Oslo: Norwegian Refugee Council.

NRC (2020). Youth Wellbeing in Displacement: Case Study Research and NRC Global Framework. Oslo: Norwegian Refugee Council.

OECD (2019). Refugee Education: Integration Models and Practices in OECD Countries. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Oh, S., and van der Stouwe, M. (2008). Education, diversity, and inclusion in Burmese refugee camps in Thailand. Comp. Educ. Rev. 52, 589–617. doi: 10.1086/591299

Picchio, M., and Staffolani, S. (2019). Does apprenticeship improve job opportunities? A regression discontinuity approach. Empirical Econ. 56, 23–60. doi: 10.1007/s00181-017-1350-2

Pincus, F. L. (2019). ”Discrimination comes in many forms: individual, institutional, and structural,” in Race and Ethnic Conflict: Contending Views on Prejudice, Discrimination, and Ethnoviolence, 2nd Edn. (New York, NY: Routledge), 120–124.

Punch, K., and Oancea, A. (2014). Introduction to Research Methods in Education. London: Sage Publications Limited.

Rutter, J. (2003). Supporting Refugee Children in 21St Century Britain. Stoke on Trent: Trentham Books.

Save the Children (2014). Save the Children Stands for Inclusive Education. London: Save the Children.

Shah, R. (2015). Norwegian Refugee Council's Accelerated Education Responses: A Meta-Evaluation. Oslo: Norwegian Refugee Council.

Soares, F., Menezes Cunha, N., and Frisoli, P. (2021). How do we know if teachers are well? The wellbeing holistic assessment for teachers tool. J. Educ. Emerg. 7, 152–211. doi: 10.33682/f059-7nxk

Stark, L., Plosky, W. D., Horn, R., and Canavera, M. (2015). ‘He always thinks he is nothing': the psychosocial impact of discrimination on adolescent refugees in urban Uganda. Soc. Sci. Med. 146, 173–181. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.10.045

Talbot, C. (2013). Education in Conflict Emergencies in Light of the Post-2015 MDGs and EFA Agendas. Geneva: NORRAG.

Taylor, S., and Sidhu, R. R. (2012). Supporting refugee students in schools: what constitutes inclusive education? Int. J. Inclusive Educ. 16, 39–56. doi: 10.1080/13603110903560085

UNESCO (2015). Humanitarian Aid for Education: Why It Matters and Why More Is Needed. Paris: UNESCO.