- Department of Political Science, Law and International Studies, and Human Rights Centre, University of Padova, Padova, Italy

In Western Europe, migrant women are very often employed in the area of domestic/care work. In Italy, their presence in this sector is very important, making them particularly susceptible to abuse and exploitation. Domestic/care workers are a gendered segment of labor migration still strongly divided along a gender binary through the sexual division of roles and labor, directly associated with the sphere of the welfare state. Migrant women in the caregiving and domestic sector are one of the least protected work groups under international and national labor legislation. For a long time, waged domestic work has not been regarded as “actual” work, as it revolves around natural tasks that women perform in the household. In Italy, the domestic work sector has recently responded to a law-decree to regulate the presence of migrant workers in areas where there is an important presence of severe exploitation. The Italian government, in May 2020, to relaunch a post-pandemic economy released a Decree titled “Emergence of employment relationships” to counteract undeclared migrant work. From the data published by the Ministry of the Interior, 85% of the total number of applications submitted involved domestic and care workers, while the remaining 15% regarded subordinate work, especially in agriculture. Evidence of widespread irregularity of foreign women employed in this sector emerged only in part. Currently, unprecedented attention as well as institutional interest have been given to severe exploitation in the labor market rather than to forced prostitution or other forms of heavy servitude to the detriment of foreigners (i.e., begging, forced criminal activities). Identification and assistance to migrants involved in severe labor exploitation however include an “extraordinary” number of young male adults which are receiving unprecedented attention. The article analyzes the effects of recent regularization of the domestic/care work and the outcome on migrant women during the critical COVID-19 pandemic period produced by this policy from a women's human rights perspective and on the ongoing debate on their protection from severe exploitation regime also in relation to the discourse on trafficking. In Italy the debate is of particularly interest even if it remains largely under-researched.

Introduction: Background, Aims and Research Contribution

In Western Europe, migrant women are very often employed in the area of domestic/care work. In Italy, their presence in this sector is very important, making them particularly susceptible to abuse and exploitation. The factors that determine the vulnerability of these women include multiple intersecting forms of discrimination and oppression.

Domestic/care workers are a gendered segment of labor migration still strongly divided along a gender binary through the sexual division of roles and labor, directly associated with the sphere of the welfare state. In some cases, migrant women provide an alternative to public care services or to different support schemes, thus covering the lack of welfare of the reproductive area of work.

Migrant women in the caregiving and domestic sector are one of the least protected work groups under international and national labor legislation. Their vulnerability emerges from the lack of skills recognition to perform reproductive work; working in the intimate sphere of the home in close proximity to their employers, and the “paradoxical” exclusion of migrant care workers from political and public debates on the securitization of migrants. For a long time, waged domestic work has not been regarded as “actual” work, as it revolves around natural tasks that women perform in the household. This has led to high levels of undeclared irregular work, large numbers of undocumented migrant women that can often suffer from severe exploitation, at times brutal.

The Italian government, in May 2020, to relaunch a post-pandemic economy released a Decree titled “Emergence of employment relationships.” It served to regulate migrant work in areas where there is an important presence of severe exploitation to counter undeclared work, including undocumented foreign workers, EU migrants and regular non-EU migrants.

From the data published by the Ministry of the Interior, 85% of the total number of applications submitted involved domestic and care workers, while the remaining 15% regarded subordinate work, especially in agriculture. Evidence of widespread irregularity of foreign women employed in reproductive work emerged only in part. In-depth analysis of the data on regularization requests may relate to “other” foreigners rather than women affected by exploitation.

It is interesting to note that currently, unprecedented attention as well as institutional interest have been given to severe exploitation in the labor market rather than to forced prostitution or other forms of heavy servitude to the detriment of foreigners (i.e., begging, forced criminal activities). Identification and assistance to migrants involved in severe labor exploitation however include an “extraordinary” number of young male adults which are receiving unprecedent attention, considering that previously the predominant framing on trafficking focused almost exclusively on sexual exploitation (Agustin, 2007). This scenario seems to suggest that women are “less” affected by the problem of labor exploitation in Italy, while there are evident operational and political challenges when intervening in contexts of domestic/care work with suited policies that counteract cases of servitude and more in general women in a situation of economic subjugation.

The article analyzes the effects of recent regularization of the domestic worker and caregiving sector and the outcome on migrant women during the critical COVID-19 pandemic period produced by this policy from a women's human rights perspective. In addition, it introduces a new interpretation and hypothesis starting from an analysis of recent data and findings in relation to foreign women in reproductive paid work in Italy after the last “regularization” effort.

Furthermore, it contributes to the ongoing debate on the protection of migrant workers within severe exploitation regime and to the discourse on trafficking from the perspective of domestic and care work and migration studies (Pavlou, 2018). This debate at present, is of particularly interest in Italy owing to its ostensible relevance in the political agenda. Furthermore, to date, the conditions of foreign women working in the domestic and care sectors remain largely under-researched.

Exploitation of Migrant Women in Paid Domestic/Care Work as a Global Issue

Although most women move from their country of origin to improve their opportunities in life, international migration intersects with a series of social risks such as exclusion from different social or institutional networks, as well as poverty, underemployment, and exploitation. Arguably, international migration and inequality are inextricably linked (Faist and Bilecen, 2015; Faist, 2019).

Academics began to observe the phenomenon of migrant domestic/care work at the end of the twentieth century. Domestic work is an important source of wage employment for women, accounting for 7.5% of women employees worldwide (ILO, 2011). They had identified the emergence of a new international division of labor (Sassen, 2000) and “global care chains” in which women from the global South leave their family members behind to provide domestic/care work for rich families in the global north. From the beginning, one of the main elements identified by academics and feminists was the diffuse conditions of exploitation. Observation and analysis of this phenomenon and public policies, led to considerations on the nature and conditions of women's subjugation in waged reproductive work (Anderson, 2000; Ehrenreich and Hochschild, 2002). Starting from reflections on the global economy and gender inequalities, with a focus on migrations between the global north and south, Eastern and Western Europe in relation to the demand for migrant domestic and care workers. Further research has analyzed how national laws and policies impact and intersect care, gender and migration regimes, determining the different working conditions of migrant domestic and care workers.

“Feminization” of the work force in the last 20 years of the past century, not only implies greater female participation in the labor force, but intervenes in the gendered division of labor itself, although, women in Italy remain subordinated to their domestic duties. Of late, inequalities involved in global care chains have gained greater attention by scholars (Anderson, 2000; Hochschild, 2000; Ehrenreich and Hochschild, 2002) also with reference to exploitation and its connection to potential situations of severe subjugation (Sciurba, 2015; Palumbo, 2016). The asymmetrical power relations between women migrant workers and native women as employers along with ethnic or racial group identity that often characterize such relations (often, also in terms of subjugation and illegality) have also been critically analyzed.

A reduction of the welfare state under neoliberalism in the early of 1990's clearly appears gendered and racialized. Debates, particularly about global care chains in Europe, have paid more attention to the intersections of welfare and care, gender equality and migration regimes and, in the past few years, have focused on determining migrant status in mixed migration flows, refugees and humanitarian. In framing crises, public discourse has turned to human mobility, addressing and labeling various different phenomena (be it smuggling, trafficking, or displacement caused by armed conflicts, humanitarian crisis and natural disasters) as the same. In recent years, however, migration has mostly been regarded as voluntary with political rhetoric shifting from “emergency” and public order-related concerns to creating a dichotomy between regular and irregular migrants (Rigo, 2018). In particular, the dramatic restriction of regular channels for migration and restrictive migration policies, which today are prevalent worldwide, has determined a downward trend in terms of protection and promotion of migrant human rights since the procedures during their arrival phase in a foreign country.

The gap between a commonplace negative representation of irregular migrants against the “need” of female foreign workers in the reproductive sector in EU countries has greatly conditioned the terms of employment and the treatment of the entire category for years (Sciurba, 2016; Garofalo Geymonat et al., 2021). Moreover, it has actually made it possible, over time, to propose a social representation of domestic/care work that is increasingly distant from the discourse of “work.” This has essentially deprived it of the dignity that is commonly recognized to any other salaried position (Camargo Magalhaes, 2017). According to ILO estimates (ILO, 2021) in Northern, Southern, and Western Europe women domestic workers directly employed by households cover 89.2% and the three largest employers are found in Italy (763,434), Spain (615,479), and France (370,362).

Clearly, the shift was made possible because of the social ascription of these tasks to women due to the gendered division of labor (which reproduces gender patterns, even when they are purchased from third parties rather than provided free of charge by women as part of tasks related to reproduction) and the prevalence in this labor market segment of women from EU or non-EU countries. The bearers of needs, women also suffer situations of weaker pay, which differ from the citizens of that country: for example, they depend more on their employer (for income, accommodation, and immigration status) (Ozyegin and Hondagneu-Sotelo, 2008).

The poor wage compensation of domestic/care workers can be ascribed to their arrangements, made within the private sphere of the home, and to commonplace ideas of women as unpaid house workers, which to date remains a common legacy. Social reproduction has long been an area of critical concern engaging Marxist-Feminist debates since the 1970s: the question of women's work and its relationship with oppression has animated feminist analysis and movements for decades and since then. Social reproduction refers to reproductive activities (women's unpaid domestic and care labor, in primis) that generate value as they maintain the current generation of (male) industrial workers while reproducing the next. Social reproduction or reproductive labor are terms that describe the activities that nurture future workers, regenerate the current work force, and maintain those who cannot work, that is, the set of tasks that together maintain and reproduce life, both daily and generationally (Dalla Costa and James, 1972; Fortunati, 1981; Fortunati and Federici, 1984; Picchio, 1992; Federici, 2004). Lately, several studies have stimulated renewed attention to social reproduction, considering its role in capitalism, and its reorganization in the global North during neoliberalism (Fraser, 2014, 2017; Ferguson, 2019).

Reproductive labor, that women perform regularly in their households, is perceived as unskilled and lacking value. In this regard, the neologism of “carers” is used to indicate people who take care of the elderly, which has replaced that of “domestic assistant,” “helper” or “maid” in common language (and before that, the boorish definition of “servant”). The term however, is neither neutral nor casual: it reflects a widespread social view of this type of work and the tendency to downplay the severity and conditions of sacrifice that it implies. It also negates the ties of affection, and lives that migrant women often leave behind in their country of origin, as well as all knowledge that may be required, especially when working with elderly people in poor health or in very different domestic environments to their own.

Invisibility and Irregularities of Domestic/Care Workers in Italy

The area within Italy's tertiary sector that is marked more than others by multiple forms of illegality and widespread exploitation is domestic/care work, which for years has favored the employment of female immigrant workers (Giammarinaro and Palumbo, 2000). This dimension is strongly “gendered” and embodies dynamics of repression of human rights and individual dignity largely defined by discriminatory logic. Today, the above must be considered to better understand the intersectional experiences of these women and the limitations placed on foreigners, both in terms of their entry and stay in Italy and, more widely, regarding their access to social rights. When framed correctly, intersectionality addresses the harm of gender neutrality on diverse groups of women by using a gender lens to recognize the diverse and interlocking oppressions to which women are subjected (Crenshaw, 1991; Yuval-Davis, 2006). In other words, it is essential to investigate the relationship between immigration and reproductive paid work, as well as the gendered nature of this work, addressing structural inequality to erase all forms of discrimination against women (Anderson, 2000, 2007; Lutz, 2002, 2008; Scrinzi, 2003). The conditions that many foreign women employed in the domestic/care sector in Italy experience are aggravated by the impacts and consequences of restrictive immigration and asylum policies adopted in these past years to “secure” state borders (Freedman, 2012) and the arrival of migrants. Undocumented immigrants in the host country or those who do not have permission to work are obviously the most vulnerable to exploitation.

Gender as relational power concept that is maintained and reproduced by materialist conditions and discursive practices—including the exercise or threat of violence and exploitation in the context of migration—frequently implies a condition of insecurity for women. This often occurs when they fail to receive a legal residence permit or social and political support, conventionally expected to reduce the risks inherent to human condition (Butler, 2009).

The risks of fundamental human rights violations within the system of the global market for paid reproductive labor often arise from intertwining dimensions that contribute to migrants' vulnerability.

The migration regime (Lutz and Palenga-Möllenbeck, 2011) within which it takes place often brings irregular migrants on the territory for different lengths of time, and leads to a work situation that, apparently has long been the subject of attention and regulation by legislation, but in reality often escapes public control or real protection against severe exploitation (National Observatory Domina, 2021).

For a more comprehensive understanding of the concept of severe labor exploitation also in the frame of trafficking in human beings, some scholars opt for a “continuum” approach (Skrivankova, 2010). In this scenario, trafficking can become a negative extreme of a reality which includes other “less severe” forms of exploitation. As Skrivankova (2010) highlights, since a clear notion of exploitation is missing, it is therefore difficult to draw the line between exploitation in terms of violation of labor rights and severe exploitation (Giammarinaro, 2022), especially when it involves women migrant workers which sometimes experience dehumanizing practices and other forms of simultaneous exploitation. Exploitation in this article, is considered broadly to include severe labor exploitation and trafficking in domestic/care work, along with other situations that contrast with the concept of decent work.

A Profile of Migrant Domestic/Care Workers in Italy

The Italian domestic sector comprises of two main kinds of work: '“family assistants” and “family helpers.” For clarity purposes, the article—like other institutional publications—uses the terms “carer” (as a synonym for “family assistant”) and “housekeeper” or domestic worker (as a synonym for “family helper”), in line with National Institute of Social Security (INPS, 2021) databases (DOMINA, 2020). In real terms, according to ILO Domestic Workers Convention (2011), domestic workers are generally defined as those who work for and in private households, very often performing non-direct care tasks while also providing young children or older household members with relational attention, combining and overlapping elements of domestic and care work generally related to reproductive work (King-Dejardin, 2019). In this regard, Italy was the fourth ILO Member State and the first EU country to ratify ILO Convention No. 189 concerning decent work for domestic workers, in December 2012, but has not yet signed the Protocol to the ILO Convention on Forced Labor (No. 29). Moreover, as for the rights of migrant workers, 30 years after the UN General Assembly adopted the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families (CRMW), Italy has neither signed nor ratified the convention.

A more in-depth look will explore the characteristics of the women who perform these tasks: being a migrant aged between 20 and 60 are the most prevalent features in the paid reproductive work sector. In 2020, the 50–54 age group had the highest frequency among domestic workers, accounting for 17.5% of the total, while 18.7% or older and only 2.3% were under 25 (INPS, 2021). In Italy, INPS data (2019 data) certify a shift in the number of domestic male workers in recent years. Looking at the overall trend, male domestic workers peaked in 2012 (192,000), then declined and settled just above 100,000 between 2016 and 2018, and fell even further in 2019 (96,000). Among domestic workers, there are higher rates of domestic helpers than caregivers, although the gap has narrowed over time. Compared to the total number of domestic workers in Italy, men now represent 11.3% (INPS data on Domina Redazione, July 8, 2021).

In 2020, 920,722 domestic workers contributed to INPS: a 7.5% (+64,529 workers) increase from 2019. Two elements have influenced this increase the most: first, the lockdown following the first wave of COVID-19, which required regular employment relationships that would allow seasonal workers to move freely for work reasons and to counteract the invisibility of foreign citizens in Italy with the aim of mitigating the impact of the pandemic to “protect health.” Subsequently, laws were implemented to govern the emersion of irregular employment relationships contained in Law-decree No. 34 of 19 May 2020, art. 103. In fact, the so-called “Relaunch law-decree known as “sanatoria” has allowed the irregular work of certain sectors to surface, including domestic/ care work, performed by family workers and caregivers, as well as foreign citizens.

From the latest available data, before adoption of the provision on domestic/care work (2019), INPS estimated almost 850,000 domestic workers, with a slight majority of family helpers (housekeepers) over family assistants (carers). It is no surprise that, in the past decade, the number of carers increased regularly against continued reduction in housekeepers: while in 2010, carers accounted for 32% of (regular) domestic workers in Italy, in 2019, this figure reached 48%. It is therefore reasonable to assume that this percentage will rise in the years to come (DOMINA, 2020).

In this context, a large share of the workforce is represented by foreign domestic workers (70% of the total)—especially from Eastern Europe—and by women (89%). However, in recent years, there has been an increase of both male and Italian workers, probably due to difficulties of the labor market (ILO, 2021).

The domestic sector has the highest share of undeclared workers in Italy: according to the National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT), they account for 57.6% of the total. This means that the 850,000 workers registered at INPS are actually less than half of the total workforce, estimated at over two million workers. Historically, reproductive paid work is performed informally, therefore estimates and precise figures on its extent are not simple to calculate because in these particular sectors there is widespread and hidden recruitment of irregular workers.

Without delving too deeply into the comprehensiveness of the data, it should be noted that official statistics only count regularly reported jobs, confirming this composition. Clearly, illegal work positions of Italian, EU or foreign citizens staying regularly, and non-EU citizens without (or who have lost) a regular residence permit must be added to the above-mentioned working positions.

The Italian Case

Regarding the Italian case, starting from the 1980s, the recourse of women in household work that care for the homes and for the people finds a purely socio-economic explanation, when family organization was changing as women were employed as wage workers, the birth rate declined, followed by progressive dismantling of the welfare apparatus. This decade marked the beginning of a significant number of foreign women involved in domestic/care work in Italy. An increase in the number of older age be added to these factors which, on the one hand, implied that women could no longer provide care work for the elderly on the same terms as previously and, on the other, saturated residential structures and nursing homes for the elderly along with higher fees. The welfare crisis, coupled with the increasing participation of women in the labor market and the recourse to paid domestic/care work, mainly performed by migrant women, seeing the demand for domestic/care work that has now become common practice, not only of affluent, upper class families but also of low-middle class ones. This is especially true for long-term care, where salaried caregivers—called “badanti”—often employed as live-in household helpers, have nowadays became a pillar of the elderly-care system in Italy (ILO, 2013; Borelli, 2021).

It should be noted that despite the increase in domestic outsourcing work, the idea of housewife as “caregiver and homemaker” is consolidated and reflected in the gender gap (in the total number of work hours, and the low full-time employment rate for women in Italy) confirmed by the large formal reality of domestic work for limited hours. The “Mediterranean” welfare model in Italy, is linked to a cohesive family model structure, which implies family-based welfare/care regime and a model of social exchange (Bettio and Pastore, 2017).

In the Italian context, a primary element of fragility lies in the fact that more and more, women can no longer play a role as informal caregiver within their own family, in other words, wives and daughters who take care of their spouse or elderly parents. Italian women's entry into the paid labor market has created greater demand for immigrant domestic workers, employed by Italian women to help balance their dual roles within the family and the labor market. While today, 2.4 elderly people in need of care depend on woman, aged between 50 and 59, in 2030 the number will be 4, and could be as high as 7.5 in 2050 (Pasquinelli and Rusmini, 2013). In a country with a strong family-based welfare system, the lack of the public response has not led to a strong political demand for services that respond to such needs (Pfau-Effinger, 2005; ILO, 2021). On the demand side, there has therefore been a growing call specifically for a domestic and personal care workforce, providing a privileged access to migrant women.

International female migration and new care needs have emblematically determined a system of silent care, a “private” search for “wellbeing” that has further strengthened the family-based matrix of our welfare. Public policies on reproduction work reflect the current social changes, bringing care and domestic activities and relations, traditionally represented as private, into the public sphere. It can modify the division of labor, cost, and responsibility among family, the state, the market, and voluntary or non-profit sector (Daly, 2011). At the same time, public policy reflects dominant legislative frameworks and common social discourse, revealing important dimensions of gender relations and women's lives in relation to care, unpaid care, and paid work, at the same time capturing the characteristics of social arrangements concerning personal needs and welfare (Lewis, 2001; Daly, 2011, p. 36). The experience of public intervention in Italy in the social field has always been limited by the systemic dimension of self-organized families with respect to their needs for care generally hiring of paid staff. Interventions are often reduced to modest ad hoc income supplements and directed in a particularistic way toward individuals and families who need support in caring for the elderly (Degiuli, 2007), the sick, or children. This process has given rise to massive privatization of domestic and care work, which relies primarily on the availability of migrant female labor (Lutz, 2008) who, of course, can be paid lower prices precisely because of this duality.

Non-EU female care workers are now a pillar of the personal care system in Italy, along with EU care workers (Picchi, 2016). For Italian families, the presence of foreign women employed in personal and domestic service work means having a lower cost labor force, with considerable flexibility to manage the workload, while for the state, it means significant constraints on public spending in this domain on the issue (Van Hooren, 2011). According to research, the development of the private domestic and care market in Italy has been mostly uncontrolled and its design was without an institutional coherence in Italy, despite being one of the European countries with the largest number of domestic and care workers. The domestic and care services sector is a typical example of a marginal labor market sector where low pay, poor working conditions, little opportunity for career development, high vacancy and turnover rates prevail. Research confirms that the development of the private domestic and care market in Italy was largely uncontrolled and lacking a coherent institutional design in terms of public policies (Picchi, 2016; GRETA, 2019).

A classification of domestic/care workers by type of employment relationship shows a significant difference in terms of distribution: over the last 10 years, family helpers have progressively decreased (−32.1% since 2012) and family assistants have increased (+11.5% since 2012). This change in trend is likely related to the aging population and the need to “buy” care for the elderly. In parallel, the economic crisis led to a decrease in the number of domestic workers (National Observatory Domina, 2021).

As families have increasingly less money to spend, they benefit from the services that these women provide, even if the condition of household works is deteriorating. This scenario has been partially remedied on the moral level due to the fact that these tasks are more or less consciously considered less burdensome and therefore are less profitable. This confirms the low social value assigned to care workers. All of the above has made exploitation more socially acceptable for the employer and for the community (Palumbo, 2016), which is increasingly inclined to look at domestic work and care as tasks delegated to third parties rather than fundamental dimensions of life, this includes the standards imposed at the social level (Kofman, 2014; Kofman and Raghuram, 2015). Moreover, these activities are often characterized by cohabitation, a situation where the boundaries between work relationships and family and intimate relationships become acutely blurred. In this context, by not recognizing care and domestic work as a full status job, many employers do not perceive themselves as such and therefore do not respect the rights and protection of their employees. On the contrary, there appears to be a widespread narrative in the everyday dynamics and contexts of the relationship between worker and employer: the latter charitably offers a “desperate” person a chance to work and “a place to sleep.” Clearly, this process negates any consideration of the human “costs” that migration entails, especially for women (Lutz, 2017). Very often, the success of the migration project to regularize one's status in Italian territory, finding employment only becomes possible where there are no cases of intolerance that would make integration (even with residence permits linked to international protection) practically impossible.

Determinants of Vulnerability: Assessing The Lack of Public Policy Response in Italy

Domestic/care workers are considered a vulnerable category, not only as they are mostly foreign and female, but also because of their actual workplace even though it important to avoid an overly simplified generalization of complex situations. According to Satterthwaite's definition, domestic/care workers' vulnerability, as framed in this article, is not as “a quality that inheres in them (….), but is instead the product of political, economic, and cultural forces acting along a variety of identity axes, including gender, race, and nationality, that disempower specific sets of women in particular ways” (2005). Vulnerability (Giolo and Pastore, 2018) is a concept that can be referred to the impact of intersectional factors that determine the risk of severe exploitation, that can also be framed as a condition of “situational vulnerability” (Finemann, 2008; Giammarinaro and Palumbo, 2021). This approach can help to redefine the narrative about communities/groups as homogenous, situating people's experiences in a systemic analysis of power and gender too. There is a significant difference between addressing women and girls as a vulnerable group, rather than understanding how power affects their life experiences, that is, how gender may interact with other social categories/factors/elements of identity including age, race, nationality, disability, economic and marital status, among many others. Another element to consider is represented by the systemic attempt to deny the women's agency, relegating them in the role of “perfectly innocent victim” or “person in need” while a different behavior is expected in order to endorse or justify a narrative of a state securitized response to migration (Wylie, 2016).

Research conducted by the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA, 2015) showed how their isolation makes these workers more exposed to the risk of being exploited and subjected to irregular working conditions. The fact that women (who in the beginning are often without independent legal status) are overrepresented in informal work sectors and as family migrants is particularly important. In the past 20 years, many countries of destination have drawn greater distinctions between different categories of migrants, increasing the stratification among them, recognizing a different status and levels of social and economic rights to migrants' (Kraler, 2010). The systematic exclusion of domestic/care workers from enforced labor regulations relates to the difficulties in monitoring private homes as workplaces. Both these elements contribute to increase the vulnerability of household workers (particularly migrant domestic workers). It is important to underscore that adopting a critical approach to the norms, the way in which a given phenomenon is regulated, results from a precise public policy schema choice.

The situation in recent years fosters growing intolerance toward foreigners on the part of an increasingly large portion of the population, often being seen as usurpers of something that, although difficult to translate into concrete terms, is present in public discourse. Hence, there is a need to reshape how migrants think about their own position, where whatever they receive does not constitute a right, but is a “gift” from the host society to which they have to be grateful toward. This is notoriously one of the fundamental mechanisms on which situations of vulnerability are built. Conversely, the notoriously rare sanctioning procedures in this area is a clear indicator of both regulatory deficiencies and the poor (but, in the institutional sphere, unfortunately widespread) perception of the serious extent of damage caused by the exploitation of domestic workers, mostly to the detriment of EU women or non-EU citizens. To put it simply, domestic work exploitation is a cheap resource that meets a widespread family need. The fact that this need is met mainly by immigrant women makes it socially accepted and widely tolerated. Moreover, the unpaid domestic work of a housewife and consequently even of waged domestic workers tend not to be recognized for their real value and thus not framed as “actual work.” Therefore the lack of recognition of reproductive work often leads not to consider salary expectations, resembling even situations of severe exploitation.

National Law and Policy Scenario: The Latest “Regularization”

In Italy, the provision, in the existing legal framework on theoretical and unlikely “remote” recruitment of a foreign worker for the purpose of regular entry makes the condition of illegality practically inevitable, a phase which anticipates the transition toward a situation of regularity (Caputo, 2009). In addition to lending itself easily and instrumentally to (potentially serious) abuse and violations of human rights (Castagnone et al., 2013; Sciurba, 2015), this situation elevates the presence of undocumented and irregular migrants who act on the labor market. Not to mention that the so-called “entry quotas” for domestic work have practically no longer been allocated since 2010 (Zorzella and Giovannetti, 2020).

Law 339, adopted in 1958 to establish a system of domestic labor regulation, is considered the first step toward specific recognition of care and domestic worker's rights. The law has established eight occupational levels based on worker's qualifications and regulated the working hours, the standard work breaks required, and possible changes in shifts (Sarti, 2010).

Italy does not provide a government-fixed guaranteed minimum wage for all professions; remunerations are fixed by collective agreements/bargaining. The most recent National Collective Agreement (CCNL) for Domestic Workers was concluded on 28 September 2020 (ILO, 2021).

The administrative instruments known as ”sanatoria/e“ are the main regulative tools in the field of migration policies in Italy. They represent a real “window of opportunity” to gain administrative access to regularize irregular residence or entry in the country. When considering the poor adherence of employers in the sector of domestic/care work compared to others, the periodic nature of provisions on illegal and irregular migrant position, in terms of regulatory policy needs, has not improved the situation of women involved in waged reproductive work. In this regard, it is interesting to note that most workers have, at some point, been forced to take on the economic burdens and see their salary cut. In practice, the regularization of employment by employers—when this occurs—does not imply a work relation lacking illegal exploitation. In fact, it often leads to the contrary as employers impose a regularization payment onto workers.

The issue of the migrant worker's dependence on their employer has also been recognized by the UN Committee on Migrant Workers. In 2011, the Committee adopted a General Comment (UN CMW No. 13) which considers the vulnerability of migrant domestic workers “throughout the migration cycle” in the case of migrant domestic workers. The document recognizes that immigration law can be a source of “specific vulnerabilities” for migrant domestic workers, most notably where immigration laws tie their status to the continued sponsorship of specific employers. According to the Committee, sponsorship systems reduce the possibility of worker mobility and increase the risk of exploitation, including forced labor and servitude (National Observatory Domina, 2021). In other words, workers are unlikely to press charges through legal proceedings against the person that their immigration status depends on because they lack resources and employment alternatives, especially if they are indebted.

Public policies related to welfare, migration and labor do not generally seem to be able to counter an ongoing demand for low-paid foreign workers in the reproductive sector. The government regularly introduces a quota for the employment of migrants in this sector. Moreover, in regularization procedures for irregular and undocumented migrants, domestic and care workers have often received preferential treatment (Sarti, 2010), confirming a “different treatment,” not only in the “tolerance” toward this target of foreign people in ordinary public discourse, but also a need for these workers. The lack of public welfare services and consequent need for private care have led the Italian government to adopt more attractive policies toward domestic/care workers (Colombo, 2003), for instance in preferential access in awarding residence permits compared to other workers. These migration policies implicitly favor false access to this work sector and go hand-in-hand with welfare and labor policies which encourage hiring external help. Van Hooren (2011) argues that the “migrant in the family model” is enhanced by the state's support consisting mainly of monetary allowance to households with dependent persons, with generally no conditions on how these funds are spent. It is also true, as Da Roit and Weicht (2013) point out, that segregation in the Italian labor market and the presence of undocumented migrants willing to work as domestic workers would, without additional care benefits, alone be enough to create this model. However, in the course of regularizations, instrumental situations and ambiguities arose in 2009 in the context of “sanatoria.” As noted by Castagnone et al. (2013), despite the lack of systematic research conducted on this issue so far, a relative openness to domestic/care workers, both by regular admission through quotas and by mass regularization, have opened opportunities and allowed a significant number of foreign workers, not necessarily employed as domestic workers, to access the Italian labor market on legal grounds (Pasquinelli and Rusmini, 2010; National Observatory Domina, 2021).

Previous regularization schemes have shown that limiting access to certain sectors does not prevent participation even by those who have no real involvement in that sector. This was also evident in 2009 and 2012 when having limited access almost exclusively to domestic work, the number of domestic workers and caregivers grew considerably, then fell the following year (Di Pasquale and Tronchin, 2020).

Whereas in 2020, regularization estimated that roughly 300,000 people without residence permits would be employed in services to individuals and families [the latest “sanatoria,” in accordance with Article 103 of law-decree 34/2020 (ASGI, 2020)] instead, involved only 176,848 applications for domestic and care work. Of these, to date, only a very small percentage have been administratively defined. However, if all of them were accepted, in Italy, the number of regular domestic workers would have to be increased by over 20%.

The ratio between estimated presence of irregular immigrants and the number of applications is certainly not encouraging. Once again, it confirms the low willingness of employers, as was the case in previous regularizations (Colombo, 2009), that would require further correction considering the downward trend. It can be assumed that an appreciable part of recent applications for reproductive paid work is an artificial consequence, determined by the limited possibility to regularize only the sectors of domestic work, agriculture, and fishing, which has led to the employment of many irregular workers in different sectors to procure “fictitious” work as domestic servants. The data related to the 2020 regularization, disaggregated by gender with reference to domestic and care work, shows that almost two out of three foreigners applying for regularization in the domestic sector were men: a very high percentage considering that in 2019, 89% of domestic employees in Italy were women based on ISTAT (Italian National Institute of Statistics) figures. The data, published by OtherEconomies based on information from the Ministry of the Interior, was obtained from civic access procedures. Gender-disaggregated data of applicants reveal that out of ~177,000 applications in the domestic sector, over 113,000 (64%) were submitted by men. Massive demand requesting regularization of foreign workers on the reproductive labor market was also present in the aforementioned “regularization” when, out of the 134,576 applications, 115,969 concerned domestic work and care, an area which in the following years was marked by an important decrease in the presence of men. This might be attributed to the fact that these migrants, after obtaining their residence permit, changed location. Based on the latest data analysis on regularization, of the 176,848 requests received (85% of the total number of requests submitted), 122,247 were for family workers, 52,729 for personal care assistants for those in need of support and 1862 baby sitters for dependent children.

The anomalies that emerge from the data on applications for regularization in the sector of waged reproductive labor (split by sex) are confirmed by examining the nationalities of foreign workers that apply, which with the sole exception of Ukraine, have a greater incidence of men in Italy. Clearly, this is a further element demonstrating the limits of this measure that, as explained by Paggi (lawyer and member of the Association for Legal Studies on Immigration ASGI), has forced thousands of people to look for a job outside their own expertise, in order to regularize themselves by expanding, among other things, the “market” of false contracts (Paggi, 2021; Rondi, 2021).

There is a clear link in Italy among the regularization process per se, which tries to reduce illegality and irregular migrant work in the original policy perspective, its failure, due to limits of this provision and a continuity in severe forms of exploitation (also trafficking, i.e.) owing to administrative obstacles in complying with the law, in addition to the economic cost when applying for this ”sanatoria.”

Considering these obstacles more men than women have applied to the regularization scheme under the domestic/carer category, even though women are the majority of workers in the sector. This fact pinpoints that men are claiming “fictitious” domestic work roles but, in reality, are employed in sectors that are not covered by the scheme. This condition is frequent in the “sanatorie” experiences in Italy since male migrants tend to have more economic resources and individual capital compared to migrant women. Male migrants normally enjoy a broader network of contacts and sponsors that make it easier for them to regularize their position, while the isolation of women in the domestic/care sector leads to less support, making it harder to achieve the same results. Additionally, in Italy many migrant domestic/care female workers come to the country alone with a short or mid-long term migratory project strictly defined on the basis of the remittances they send to their family in the country of origin. This condition determines a weaker interest in applying for regularization compared with men working in sector excluded from the sanatoria as seasonal manpower or characterized by a severe control of illegal recruiters (caporali). The persistence of exploitation with regard to domestic/care work can therefore be found in the scarce number of “authentic” applications, in line with the already mentioned limits and outcomes of other previous schemas on illegal migrant work regularizations (National Observatory Domina, 2021).

Severe Exploitation and Trafficking in Domestic/Care Work in Italy: A Hidden Phenomenon

As recognized by the EU Commission in the latest Report on the application of Directive 2009/52/EC of 18 June 2009, providing for minimum standards on sanctions and measures against employers of illegally staying third country nationals (COM, 2021; 592 final), illegal employment exposes migrants to risks of violation of individual and social rights, notably labor exploitation, precarious living and working conditions, and limited or no access to social protection. Furthermore, in some cases, labor exploitation can also have links to serious and organized crime, either through trafficking in human beings for labor exploitation or exploitation of irregular migrants by smuggling networks through debt bondage, where a person is forced to work to pay off a debt, and exploitative work conditions (Gallagher, 2010). Moreover, criminal networks, not necessarily very structured, also target migrants who are staying irregularly in the EU, forcing them to work—often—under highly exploitative conditions. Precarity may well involve diverse groups, defined by gender and other characteristics as age, nationality, and ethnicity.

Considering the increased “employability” of migrant women in specific sectors of the European labor markets and possible factors of vulnerability, precarity, and exploitation in the context of temporary circular labor migration take place in the Italian house work and care sector (Marchetti, 2015). In concrete terms many of the experiences of severe labor exploitation see women in the domestic/care sector working up to 11 or 12 h a day, 200 h per month, that can be likened to amount to trafficking in human beings as defined in Article 2 of the EU Anti-Trafficking Directive (2011/36/EU) (FRA, 2011, 2019). Framing inequality today requires looking at the stratification and understanding social divisions of gender, national origin, race/ethnicity, gender, linguistic repertoire, socio-economic status, and class (among many others), which intersect at the local, national, and transnational level, determining access to material and symbolic resources, social status, and level of power. They are intrinsically related to discursive practices of “othering” as they construct specific, more or less welcome, groups.

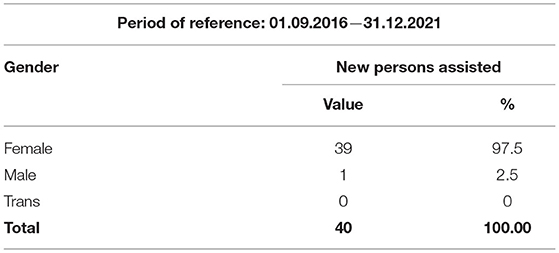

Based on national data on women victims of severe exploitation (see Table 1) also through trafficking process who came into contact with and were evaluated by the social operators of Anti-Trafficking Projects (September 2016 _ December 2021) within the framework of the National System, coordinated by the Equal Opportunity Department of the Presidency of the Council of Ministers, severe exploitation in domestic and care work and, in agriculture, are the two dominant areas of subjugation for women after forced into prostitution. In fact the National Anti-Trafficking Toll-Free Number (800.290.290), provides 24-h assistance to victims, controls the database on social intervention in coordination with the existing local referral mechanisms, directly contacting territorial Projects to protect the victims of exploitation. The hotline is a structured policy instrument designed to respond to the trafficking phenomena on a nation-wide level by spreading information, through awareness raising campaigns, research intervention activities regarding specific aspects and the evolution of trafficking, and through the coordination of different accredited local authorities and NGOs. The Veneto Region, mandated by the Government's Department of Equal Opportunities, manages the Toll-Free Number.

Table 1. Data extracted from the computerized system for the collection of information on trafficking in human beings (SIRIT 11/04/2022)—by the Anti-Trafficking Toll-Free Number, Department for Equal Opportunities of the Presidency of the Council of Ministers Data related to new cases of victims of exploitation in the field/area of “domestic servitude” emerged and assisted.

Moreover, the data collected reveals that among the women evaluated between 2016 and 2021 situations of serious exploitation in labor tool place, with 40 cases of “domestic servitude.” Of these cases, 39 involved foreign women from different countries and, among them, only one was underage when taking on the role.

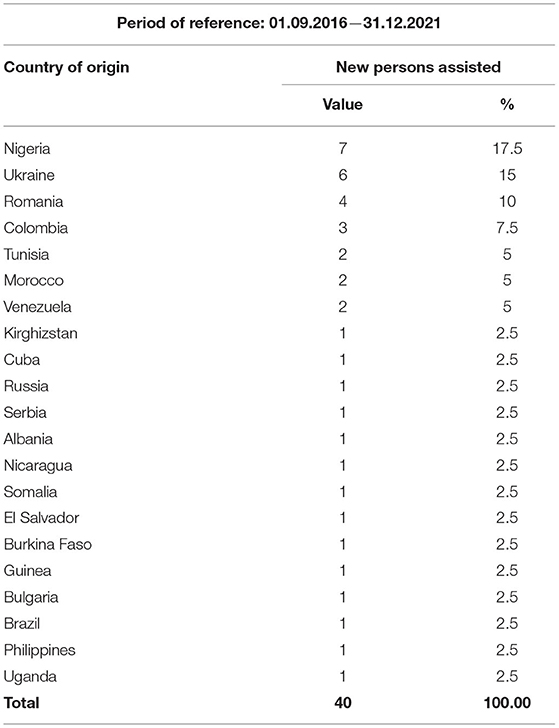

Looking at nationalities (see Table 2), the countries of origin that most emerged for this type of exploitation are Nigeria (seven cases), Ukraine (six), Romania (four), and Colombia (three).

Table 2. Data extracted from the computerized system for the collection of information on trafficking in human beings (SIRIT 11/04/2022)—by the Anti-Trafficking Toll-Free Number, Department for Equal Opportunities of the Presidency of the Council of Ministers Data related to new cases of victims of exploitation in the field/area of “domestic servitude” emerged and assisted.

Worth noting that both the Nigerian and Ukrainian communities are quite large in Italy, even in terms of number of women, but they are not the most populous nationalities in the domestic and care work sector. Traditionally, countries such as Romania, Ecuador, the Philippines, and Albania prevail, but with lower numbers in terms of cases of serious exploitation.

It is important to highlight that law enforcement agencies have played a pivotal role in fighting serious labor exploitation. More so than social workers. Conversely, the role of subjects classified as friends/acquaintances of the victim, in the Anti-Trafficking System database should be further explored. Both these types of subjects have contributed (in six cases each) to the emergence and investigation of victims, who were also reported to anti-trafficking operators via information desks, contact units of anti-trafficking projects, local and national NGO and territorial commissions for applicants for international protection.

How to Tackle Exploitation and Illegality in Domestic/Care Work: The Weakness of Law Instruments

Until a few years ago, domestic work exploitation mainly involved people without a residence permit and in an irregular situation on the territory, mostly non-EU workers from Eastern Europe. Today, this extends to include EU citizens from the east (especially Romanians), asylum seekers, and other permit holders foreseen by the national system. Therefore, despite an absence of official statistics, fewer without a residence permit were employed in the domestic sphere, especially in northern Italy. This however, has not only led to a reduced condition of exploitation, but rather to more sophisticated techniques, with “gray” areas of work clearly directed at reducing the risk of sanctions and claims.

This circumstance can be explained by considering the deterrent effect of criminal sanctions, foreseen only for the employment of irregular non-EU workers. Unlike other cases, criminal sanctions can only be applied for serious exploitations, whose verification is, however, even more uncertain. As a matter of fact, in cases of irregular non-EU citizens, it suffices to assess work performance for 1 day, along with the lack of a permit, to configure a crime referred to in Article 22, paragraph. In these cases, fearing conviction, the employer often abandons the idea of contesting economic claims by weighing up the lack of evidence and often considers it more appropriate to reach a decent conciliation to avoid recourse to the judicial authority. This does not take into account that regularizing a migrant's residence status is conditioned by the need to ascertain conduct of serious exploitation, although a verification of this exploitation is often unsystematic. This will be further explained below.

A basic problem concerning both irregular migrants and regularly residing EU or Italian citizens has to do with wage disparities which is connected to criminal violations related to exploitation clashes and difficulties in proving both the existence of a subordinate work relationship in this particular area where there may be no work contract and the extent and actual nature of the work performance. In fact, even in cases of assistance to the person, the formalization of “gray” employment relationships, or contracts that cover and almost always only pay officially declared hours rather than the actual work performed that surpasses the hourly limits fixed by the CCNL is widespread (Paraciani and Rizza, 2021).

The Italian National Labor Inspectorate ensures the correct implementation of all labor and social security regulations, including prevention and combating undocumented work. Labor inspectors have: free access to the premises, buildings, and rooms of the inspected entities, can take statements from workers, may request all relevant documentation and seek information from all public offices, labor consultants, employers, and social security institutions. Labor inspectors, as judicial officers in matters of their own competence, are obliged to send timely reports to the relevant authorities. The places where labor inspectors can legitimately carry out their work are dictated by Presidential Decree 520/1955, which excludes private homes, for which the normal rules on access to workplaces do not apply. Article 8, paragraph 2 of the Presidential Decree provides that labor inspectors—like street-level or frontline workers—work within the limits of the service to which they are assigned. Labor inspectors' limited powers of investigation also correspond to fewer sanctions targeting irregular employment relationships that take place within the household, thus, reducing deterrence. This condition does not facilitate inspections. Even though inspectors can use discretionary powers as mediators of policies [in the sense that they transform formal policies into policy practices (Brodkin, 2013), refer cases to the Labor Inspectorate's conciliation facility, resolve disputes or appeal to the criteria of justice and justiciability and reparation of workers' rights], they believe that employment irregularities in the domestic sphere must be further investigated (Lipsky, 1980; Paraciani and Rizza, 2021). Very often, policies are ambiguous or contain conflicting definitions of problems and goals or are based on a system of administrative rules articulated so that policy delivery and frontline agency become part of the arena where problems are defined, and solutions developed. The complexity of the environment has increased as a consequence of new forms of governance for the delivery of public policies and services, among others (Denhardt and Denhardt, 2000). A crucial part of frontline workers' agency (Møller and Stensöta, 2019) entails coping with these contextual issues and those related to severe forms of exploitation in Italy which may potentially involve other professional figures and institutions in determining discretionary decision making, as well as define and limiting options and decisions in using discretion (Heidenreich and Rice, 2016; Van Berkel et al., 2017). In 2020, more than 100 domestic workers were officially involved in labor violations identified by labor inspectors (Official Data National Labor Inspectorate).

The problem of proof is therefore difficult to resolve, thus preventing protection in both criminal and civil law. It is up to the worker to offer evidence that, without documentation, can only be provided by witnesses that can testify. In cases where assistance to a person who does not cohabit with other relatives is needed, it can be quite easy; in the cases of services with non-cohabitation, witness evidence is arduous.

It is worth highlighting that not only is the application of the so-called “maxi sanction” for undeclared work legally precluded to employers of domestic workers, but inspections are also quite complex and are legally almost impossible in private homes. This means that official data relating to modest results of supervisory offices must be interpreted as the outcome of difficult attempts in mediating among the parties involved in monocratic conciliation.

Facing such obstacles, recourse to video recordings can provide practical proof. The Court of Cassation has only recently cleared it as a lawful evidence, although such expedient is not easy to use. Moreover, it is only relevant if it truly reconstructs a typical working day, the starting time and date of the employment relationship.

With regard to the crimes that are typically related to labor exploitation, note that in practical experience, cases of trafficking for the purpose of labor exploitation and as such punishable under Article 601 of the Criminal Code1 seem to have only recently emerged and in very few circumstances. In other words, to date, the identification of criminal networks that govern the overseas recruitment and illegal entry for the purpose of exploitation in domestic work is struggling to emerge, even in the face of important investigative signals, although these investigations are leading to some arrests.

A first criminal investigation concluded in June 2021 identified a criminal transnational association that committed an undetermined series of crimes of illegal intermediation, exploitation of Moldovan citizens, aiding and abetting illegal immigration; extortion (the criminals forced Moldovan women to give them money, threatening to abandon them in the street and have them arrested). This involved the recruitment of Moldovan citizens (among others) to assign them the job of caregivers in conditions of exploitation, taking advantage of their state of need. A more recent police investigation identified women in an extreme condition of vulnerability and poverty. They were sent to Italy to work, then exploited in families that needed assistance for the elderly. From Moldova to Italy, dozens of women paid 500 euros for their journey. They had to return that sum to their exploiters together with a 100 euro “bribe” per month. They worked 24/7 without a day of rest. Those who dared to take an hour's break were beaten or threatened to be sent to work on the streets as prostitutes. Women were deprived of their passports to prevent them from moving freely around Italy or returning to Moldova once they realized that their working conditions were different from what they had established. They were taken to a small apartment where they stayed in exchange for money, sleeping on the floor, before moving to the family who had requested them. There, due to lack of adequate space, they had to sleep in the same bed as the person they were assisting.

Exploitation in the field of domestic work, when the working relationship between two subjects assumes a para-familiar character, it can lead to the crime of mistreatment against family members or cohabitants, provided for by article 572 of the Criminal Code. Instead, the crime set by article 603-bis of the Criminal Code on illegal recruitment and exploitation of labor directly punishes the employer, regardless of whether or not there are recruiters (and even in the absence of a para-familial cohabitation), when there is one or more index of exploitation considered in the same rule or: “the repeated payment of wages in a manner clearly different from the national or territorial collective agreements; the repeated violation of regulations relating to working hours, rest periods, weekly rest, compulsory leave, vacations; the existence of violations of the rules on safety and hygiene in the workplace; the submission of the worker to working conditions, methods of surveillance, or degrading housing situations.”

More specifically concerning the working conditions of workers without a residence permit, detecting situations of exploitation can give rise to the granting of a residence permit, with incentives to denounce and indirectly reward. In this regard, the provisions of article 18 and article 22, paragraph 12-bis and -seq. of Legislative Decree No. 286/98 (Consolidated Act on Immigration) on immigration are complementary but not easily applicable to domestic work.

The specific conditions of female workers employed in domestic work and care, especially when the cohabiting regime produces a strong isolation and greater vulnerability, are certainly not the most favorable to encourage complaints or, much less, the hope of finding better placement. However, the challenges in collecting evidence of exploitation in this area are associated with additional difficulties given by the way these rules are formulated, clearly not designed to envisage such situations of exploitation. “Anti-trafficking” rules were given little space in domestic work, even in cases of particularly deteriorating working conditions, except aggravating conduct that is typical of different work areas, such as agriculture is demonstrable.

With regard to the specific permit for victims of labor exploitation, article 22 of the Consolidated Act on Immigration has been amended by Decree 109/2012, which has implemented, albeit belatedly, EU Directive 52/2009/EC, which is expressly aimed at ensuring sanctions for the exploitation of irregular immigrants and to encourage reporting, with a provision of a permit based on a rewarding logic. Among the many limitations of the aforementioned domestic transposition law, the political choice to reduce the concept of exploitation—which the directive clearly refers to the individual condition—only generally concerning cases where more than three workers are employed in an irregular condition of residence, expresses the precise and conscious will to (in practice) exclude domestic work from the scope of application of the rule, even in situations that have the indices of exploitation determined by article 603-bis criminal code.

Therefore, it is comforting only up to a certain point that these rules find more space for application against pseudo-entrepreneurial organizations (that can rightfully be defined as criminal associations) and that increasingly offer home care services, making profit from conditions of exploitation of women workers (in these cases well above three), using forms of “gray” labor, or that abuse contracts, which imply a derisory pay and the exclusion of fundamental rights such as vacations, leave, and rest.

Shortcomings and Obstacles in Addressing Severe Exploitation of Domestic/Care Workers in Italy

“Regularization” represents, in general, a controversial schema of migration policy, since it intervenes “a posteriori” by reducing the irregular presence of foreigners, without modifying the mechanisms that generated it; In other words, it is the emblem of an “emergency” migration policy (Leone Moressa Foundation, 2020).

The latest sanatoria of migrants was one of the solutions that emerged at the start of the health emergency for reasons related not only to the protection of health, but also to public safety.

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected everyone, but not everyone equally. The Policy Brief published by the United Nations “COVID-19 and People on the Move” (2020) highlights the effects of the pandemic on the migrant population worldwide. It can be summarized as a crisis that is simultaneously health-related, socio-economic, and humanitarian. For each of these dimensions, the Policy Brief highlights the factors that have contributed to generating or worsening this crisis, including, in terms of health, overcrowding and unhealthy housing conditions, lack of access to public health systems, lack of adequate nutrition, as well as, of course, the illegality, and therefore the invisibility of many migrants. Regarding the socio-economic dimension, the triggering factors can be found in the rise in unemployment and consequent loss of means of subsistence as well as in accentuated situations of vulnerability and therefore of serious exploitation.

In the socio-economic sphere, the health emergency led to significant disempowerment of large portions of the migrant workforce, exposing them more to exploitation and irregular employment. The restrictions in force on national territory and the fear of sanctions not only for migrants but also employers have made it particularly difficult for workers in irregular conditions to move to the workplace, also due to the fear of spreading the disease. This was especially true in the domestic and care sector where there has been a significant loss of regular work positions. Domestic workers are, in fact, not included among the categories that have benefited from the freeze on dismissal. According to the National Association of Domestic Workers (Assindatcolf), in the period between March and June 2020, ~13,000 work agreements came to an end (Gonnelli, 2021).

While regularization has been advocated as a form of social protection of migrant labor by some intergovernmental organizations, including the United Nations and the International Labor Organization, which recommend adopting measures to support migrants through the extension of visas and the renewal of work or residence permits. In Italy, the regularization of migrant workers was suggested as a way to cope with the production crisis that some sectors were experiencing as borders closed consequently blocking foreign workers as a result of the pandemic.

In the Italian legal system, regularization was promoted by the government as a means to solve the social crisis experienced by irregular foreign workers on the territory, highlighting the importance of encouraging the visibility of thousands of people who live and/or work on Italian territory, to provide adequate protection of personal and collective health and to take a step forward in strengthening the fight against caporalato and the exploitation of national and foreign labor workers.

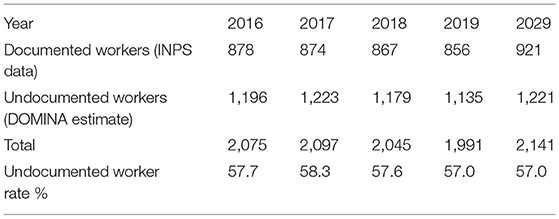

However, evidently, beyond the partially calming effects of serious exploitation in Italy attributable to regularization schema, a situation of tolerance toward illegality still persists with a pervasive use of practices aimed at keeping the cost of domestic labor low. According to the Annual Report on Domestic Work, the percentage of undeclared work in the sector is 57%: ISTAT reports that these figures are the highest among those detected in the various economic sectors by the institution (National Observatory Domina, 2021, p. 76). This implies that the 920,000 domestic/careworkers registered with INPS represent less than half of the total, which therefore exceeds 2.1 million. It is interesting to note the trend formulated by Observatory Domina on the basis of INPS and ISTAT data in the above chart.

Alongside undeclared work, situations of serious exploitation are hidden behind under-employment, false declarations of working hours, non-payment of overtime and night work, and the non-use of daily, weekly and annual rest periods (see Table 3).

Table 3. Estimation of undocumented workers in domestic work, time series1 (data in thousands) Processing by DOMINA National Observatory of INPS and ISTAT data.

Another widespread phenomenon is unlawful intermediation of domestic workers. Forms of illegal networks offer a variety of work: from the “classic” provision of labor by a subject that does not have the authority to operate as an employment agency, to the provider of the cheapest collaborators, supplying domestic workers that were formally hired by families but trapped by organized crime (National Observatory Domina, 2021).

The lack of administrative controls, owing to difficulties related to law restrictions [except in cases of a well-founded suspicion “that they serve to carry out or conceal violations of the law” (article 8, Presidential Decree No. 520/1955)] strengthen the conditions of severe exploitation. Furthermore, based on, ILO Convention n. 189, which requires states to adopt inspection measures, including access to the family home (article 17, para. 3), does not seem to fully complied with the obligations defined by the same Convention. However, in recent years, awareness and mobilization in the domestic sector have been growing, oftentimes as consequence of the great attention to other fields of exploitation where the high presence of severely subjugated male workers tends to hide women's conditions.

The marked vulnerability of immigrant women's employment can be explained by the clear tendency to work in jobs with little protection and particularly exposed to precariousness and restrictions (as well as the risk of contagious diseases). More than half of them work in only three professions: domestic helpers, caregivers, office, and commercial cleaners (compared to 13 professions for foreign men and 20 for Italian women) and 39.7% are domestic helpers or caregivers.

The lack of regularization is also a factor that affects the employment decline of foreign women. A slow regularization in the summer 2020 is evident, considering that by the end of July 2021, only 27% of applications had completed the process and a residence permit was issued. The high concentration of work with families severely limits the possibility for foreign female workers to rely on the dismissal ban and access unemployment temporary funds. According to INPS data, women represented just 10.5% of non-EU recipients of ordinary unemployment benefits in 2020 and 24.3% of extraordinary unemployment benefits. Their share rises only for ordinary allowance of the Solidarity Funds (37.6%) and the redundancy fund in derogation (41.1%) (Redattore Sociale, 2021).

Work within the home, considered an innate role and duty of women, has been carried out and gone unpaid, thus contributing to the social devaluation and economic invisibility of women in reproductive work. Law regimes, in particular immigration and labor law, not only reflect these ideologies around paid domestic and care work, but also play an important role in reproducing the vulnerability of migrant domestic workers and in strengthening the irregular dynamics of the labor market, resulting in severe conditions of exploitation.

Conclusion

The data on reproductive waged work clearly highlights widespread illegality as a structural reality in Italy due to the large number of foreign workers in undocumented or illegal work conditions. This dimension is clearly confirmed by the outcomes from the latest sanatoria.

At present, on the basis of the available data, slave-like conditions and trafficking can be experienced by a very limited number of migrant domestic/care workers in Italy among the 633,162 foreign individuals employed in this activity at the end of 2020 (the total number, including Italian workers, amounts to 922,587) as revealed by recent investigations that have uncovered cases of severe subjugation. On the contrary, clearly the number of women who suffer potential degrading working conditions, low wages, insufficient safety measures and lack basic social protections, out of the 1,220,492 workers estimated by Domina in the 2021 Annual Report, could be very high.

This scenario per se represents a failure of the government's schema to regulate migrant labor and give thousands of foreigners dignity in Italy.

The article therefore explains that the exploitation some migrant women in domestic/care work experience is a structural phenomenon that can be more or less severe depending on a plurality of factors. Today, renewed attention has been devoted to issues of severe labor exploitation, including the trafficking context. The great visibility of male subjugation in many work sectors, seems to implicitly support the emersion of women's condition in reproductive waged work. Coherently, in this scenario recent investigations on trafficking cases of domestic/care women migrant workers should be framed to focus on this specific form of exploitation. In Italy, nowadays, there is a persistent plurality of work sectors characterized by a very large segment of illegal labor that calls for a “political will” to contrast such condition, both for the mistreatment it expresses, and for the difficulties to “govern” the phenomenon due to the proportion of foreign migrants who suffer some sort of abuse at work including domestic/care employment.

A real political will to maintain or modify the status quo can be measured against proposals aimed at encouraging the repression of any violations, but this implies a change in the way women's work is valued. Such aim calls for a recognition of reproduction as a fundamental process in life even in economic terms; only within this frame can the value produced by women's work be correctly identified also in waged domestic/care employment performed by migrants.

Author's Note

Law-decree 19 May 2020, No. 34, on urgent measures on health, support for employment and the economy, and social policies related to the emergency COVID-19 pandemic, converted into Law July 17th 2021 n. 77, article 103.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary materials, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Article 601 of the penal code criminalizes trafficking. It prescribes penalties of 8–20 years' imprisonment, which increase by one third to one half if the offense involved a child victim. Additional penal code provisions are utilized to prosecute severe forms exploitation. Article 600 criminalizes placing or holding a person in conditions of slavery or servitude, and Article 602 criminalizes the sale and purchase of slaves—both prescribe the same penalties as Article 601. Additionally, Article 600-bis criminalizes offenses relating to child sex trafficking and prescribes punishments of 6–12 years' imprisonment.

References

Agustin, M. L. (2007). Sex at the Margins: Migration, Labour Markets and the Rescue Industry. London: Zed Books.

Anderson, B. (2000). Doing the Dirty Work?: The Global Politics of Domestic Labour. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Anderson, B. (2007). A very private business: exploring the demand for migrant domestic workers. Euro. J. Women's Stud. 14, 247–264. doi: 10.1177/1350506807079013

ASGI (2020). Emersione dei lavoratori stranieri 2020. Scheda Pratica. Available online at: https://www.asgi.it/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/2020_Scheda-emersione-2020_16_06_def.pdf

Bettio, F., and Pastore, F. (2017). Female Employment & Dynamics of Inequality Research Network Overview of Female Employment Issues in Italy, Country Briefing Paper No: 06.17.7. Available online at: https://www.soas.ac.uk/fedi/research-output/file137449.pdf

Borelli, S. (2021). Le diverse forme dello sfruttamento nel lavoro domestico di cura. Lavoro e diritto Rivista trimestrale 2, 281–301. doi: 10.1441/100864

Brodkin, E. (2013). “Street-level organizations and the welfare state,” in Work and the Welfare State: Street-Level Organizations and Workfare Politics, eds E. Brodkin and G. Marston (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press), 17–35.

Butler, J. (2009). Performativity, precarity, and sexual policies. Aibr. Revista de Antropología Iberoamericana 4, 321e−336e. doi: 10.11156/aibr.040303e

Camargo Magalhaes, B. (2017). Mind the protection (policy) gap: trafficking and labor exploitation in migrant domestic work in Belgium. J. Immigrant Refugee Stud. 15, 122–139. doi: 10.1080/15562948.2017.1305472

Caputo, A. (2009). Immigrazione, politiche del diritto, qualità della democrazia. Diseguali illegali criminali Quest. giust 1, 83–86. doi: 10.3280/QG2009-001008

Castagnone, E., Salis, E., and Premazzi, V. (2013). Promoting Integration for Migrant Domestic Workers in Italy. Torino; Geneve: FIERI; ILO. Available online at: http://www.ilo.org/global/topics/labour-migration/publications/WCMS_222290/lang–en/index.htm

Colombo, A. (2003). Razza, genere, classe. Le tre dimensioni del lavoro domestico in Italia. Polis Ricerche e studi su società e politica 2, 317–344. doi: 10.1424/9567

Colombo, A. (2009). La sanatoria per le badanti e le colf del 2009: fallimento o esaurimento di un modello? Fieri Analisi e Commenti. Available online at: https://www.fieri.it/la-sanatoria-per-le-badanti-e-le-colf-del-2009-fallimento-o-esaurimento-di-un-modello/#_ftn1

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Rev. 43, 1241–1299. doi: 10.2307/1229039