- Mannheim Centre for European Social Research, University of Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany

Research on discriminating behavior against ethnic minorities in everyday situations is still a rather under-researched field, since most prior research on ethnic discrimination focuses on housing markets, job markets, criminal justice, institutions or discourses. This article contributes toward filling the research-gap on everyday discrimination by bringing together prior research from sociology and social-psychology, including threat and competition theories from integration research, social identity theory, particularism-universalism theory and experimental findings on fairness norms. It conceptually advances the field by combining them into an integrated interdisciplinary approach that can examine discriminating behavior in everyday situations. This approach studies the dynamics of ingroup-outgroup relationships, fairness norms and threat in regard to negative behavior toward others (e.g., a neighbor). In particular, it focusses on the dynamics under which negative behavior is more likely toward an ethnic outgroup-person than an ingroup-person (i.e., discriminating behavior). To scrutinize the expectations derived within this framework, a factorial survey experiment was designed, implemented and analyzed (by means of multilevel mixed-effects linear regressions and average marginal effects). The survey experiment presents a hypothetical scenario between two neighbors in order to measure the effects and dynamics of ingroup-outgroup relationships, fairness norms and threat on behavior. While no significant outgroup-effect can be found in the general analysis of the main effects, more in-depth analyses show an interplay of situational cues: Outgroup-discriminating behavior becomes significantly more likely when the “actor” has low general fairness norms and/or when threat-level in a situation is low. These results foreground the importance of interdisciplinary in-depth analyses of dynamics for understanding the conditions under which discriminating behavior takes place in everyday situations—and for deriving measures that can reduce discrimination.

Introduction

Discrimination based on ethnicity is a problem that every society faces. One that has yet to be solved. The issue is increasingly being addressed by politicians, the media, social media and in research. While most people focus on examining either the prevalence of ethnic discrimination and racism (attitudes, discourses, actions) and the individual or institutional causes, there is still a gap to be filled in regard to the dynamics and mechanisms of ethnic discrimination in everyday situations—such as encounters in the neighborhood (Diekmann and Fereidooni, 2019). During such encounters, it is likely that several causes affect how, for example neighbors, will react toward one another. Such causes involve, for instance, the perceived environment (including challenges or threats), a person's norms and ingroup-outgroup relationships (Blau, 1962; Tajfel et al., 1971; Tajfel and Turner, 1979; Smelser, 2015).

While much research has been conducted on discrimination of ethnic minority groups in the context of institutions, criminal justice, housing markets and labor markets (e.g., Heath et al., 2008; Pager and Shepherd, 2008; Wu, 2016; Quillian et al., 2017, 2019, 2020; Horr et al., 2018; Auspurg et al., 2019; Sawert, 2020; Zschirnt, 2020), until recently, discrimination in common everyday situations has been almost entirely neglected. While this dimension of ethnic discrimination is still under-researched, the very recent appearance of a number of publications studying everyday discrimination (e.g., in the metro or in the classroom) underlines the importance of filling this gap (e.g., Wenz and Hoenig, 2020; Mujcic and Frijters, 2021; Sylvers et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022). Because everyday discriminating behavior can occur in many different situations, more (experimental) studies on particular circumstances should be conducted. Looking at encounters between neighbors is a situation that merits special attention, since it is a very common situation that people find themselves in. Some adjacent research exists, such as cross-sectional and longitudinal studies looking at, for instance, neighborhood trust (in the context of diversity). They show that trusting one's neighbor is affected dynamically by ingroup-outgroup relationships as well as both individual characteristics and the environment (e.g., threat) (Laurence et al., 2019a,b). However, to date, there is a lack of research scrutinizing common everyday discriminating behavior between neighbors. In order to address this research gap, this article empirically focusses on such an encounter-situation between neighbors. As a point of departure, it poses the following research questions: How do ingroup-outgroup relationships, fairness norms and threat-levels influence negative behavior toward a neighbor? When is such behavior discriminating? What are the dynamics between ingroup-outgroup, fairness and threat that make discriminating behavior against a neighbor more likely?

In order to find answers to the research questions above, this article first presents the relevant literature, develops considerations and derives expectations related to the research questions. It then presents evidence from a factorial survey experiment (Rossi and Anderson, 1982; Jasso, 2006; Auspurg and Hinz, 2015) on ethnic discrimination among neighbors (in Germany). The survey experiment was conducted with a random sample, containing Germans and persons from minority nationalities in Germany. With this methodological approach, the factors of interest (ingroup-outgroup relevant ethnicities, fairness and perceived threat) can be measured independently in their effects on discriminating behavior. Due to the within-design, the effects are analyzed using multilevel mixed-effects linear regressions (Raudenbush and Bryk, 2002). The analyses also go into the depths of the dynamics at play by examining relevant interaction effects (e.g., between the ingroup-outgroup relationship and perceived threat) using multilevel mixed-effects linear regressions and average marginal effects. After the section on the results of the analyses, the findings are discussed in light of the research questions and relevant prior research.

Overall, this approach contributes both to developing the research field on ethnic discrimination—by proposing an integrated, interdisciplinary approach to examining everyday discrimination—and to providing first rigorous empirical experimental survey results that offer information to policymakers and other relevant stakeholders on what factors need to be changed in order to reduce discrimination (Laouénan and Rathelot, 2022), during everyday encounters in neighborhoods. This approach is supported by previous research showing that discriminating behavior can be reduced by changing particular relevant parameters of the situation (Auer and Ruedin, 2022). With its survey experimental approach, this article provides a foundation for future research on discriminating behavior in common everyday situations. The antecedents and dynamics found in the analyses of this study should be tested in regard to other common everyday-encounter situations, in order to find either similar dynamics or differing ones, to provide information for situation-specific interventions that can reduce discriminating behavior.

Materials and methods: Interdisciplinary integrated approach and research methodology

An interdisciplinary integrated framework of antecedents and dynamics of everyday discrimination in neighborhoods

While interesting research has been conducted regarding certain factors of influence on discrimination (e.g., threat and competition theories, social identity theory), this article goes beyond previous research in bringing together a number of theoretical and empirical perspectives, mainly from sociology and social-psychology. Primarily, it integrates threat theory—particularly from sociological integration research (e.g., Olzak, 1994; Olzak et al., 1994; Soule and van Dyke, 1999; Ebert and Okamoto, 2015; Shepherd et al., 2018)—with theories on ingroup-outgroup relationships—such as social identity theory and sociological particularism-universalism theory (Parsons, 1951; Blau, 1962; Tajfel, 1978; Tajfel and Turner, 1986; Smelser, 2015)—and psychological-experimental results on fairness norms (Waytz et al., 2013; Dungan et al., 2014, 2015). It proceeds in the sense of middle-range theories, assuming that the causes and mechanisms are context-specific to a certain extent but may be generalizable to other contexts (Merton, 1968; Hedström and Ylikoski, 2014). Building on this integrated framework, this interdisciplinary approach posits that ethnic ingroup-outgroup relationships lead to discrimination in the tension field of group, individual and environmental factors. This approach aims to examine ethnic discrimination in common everyday situations, such as an encounter between neighbors. As it aims at delivering results that are relevant for implementing measures that can reduce discrimination, the focus lies on examining under what conditions ethnic outgroup-discrimination leads people to treat others badly (behavior).

Ingroup-outgroup relationships and standards seem to contribute to behavior, such as discriminating actions, together with other factors (cf. Wilder and Shapiro, 1984; Marques et al., 1998; McGuire et al., 2017). Such factors include, but are not limited to, fairness norms and threatening situations. This leads to the question: Why is it relevant to examine ingroup-outgroup relationships, fairness norms and threat (and their dynamics) together? Both of the latter antecedents bear relevance to dynamics at play during ingroup-outgroup situations and are, therefore, relevant for understanding how to reduce ethnic discrimination as a driver of negative behavior toward others. Fairness norms are universalistic in the sense that one applies them to all other persons (irrespective of group-membership or characteristics), whereas ingroup-outgroup relationships are (per definition) particularistic, so only applied to persons with particular characteristics such as gender or ethnicity, or to members of a group (e.g., football team, workgroup) (Blau, 1962; Waytz et al., 2013; Smelser, 2015). Social-psychological experiments show that both particularistic and universalistic standards influence how people will behave (Dungan et al., 2014, 2015). Moreover, since, being fair is somewhat oppositional to discriminating against someone, higher fairness norms might reduce discrimination. Previous research on threat in the context of ingroup-outgroup relationships argues that when a threat is perceived, the negative behavior toward outgroup members becomes more likely (Rabbie, 1982). Hence, when inspecting ethnic discrimination in neighborhood ingroup-outgroup encounters, it is relevant to examine the role of fairness norms and threat—in order to find possible solutions that will lead to less discriminating behavior.

Why is it important to study hypothetical behavior in specific everyday situations to examine the dynamics of discrimination?

Previous literature on discrimination often examines negative attitudes of members of an ethnic majority toward ethnic minorities (e.g., Quillian, 1995; Fetzer, 2000; McLaren, 2003; Lahav, 2004; Schlueter and Davidov, 2013; Esses and Hamilton, 2021). One major subfield of this research examines attitudes in the context of perceived threat. Jedinger and Eisentraut (2020), for instance, posit that perceived cultural, economic and criminal threats through minority groups can negatively influence the attitudes of ethnic majority groups toward minority groups—especially in regard to particular ethnic minorities. While studying attitudes is relevant for many research questions on discrimination, it is less than ideal for studying discriminating behavior toward ethnic minority groups (cf. Okamoto and Ebert, 2016). If one is interested in research that is able to provide suggestions for measures that can decrease discriminating behavior in common everyday situations, one must study how discrimination leads to negative behavior toward minority outgroup persons. There is only a limited amount of research studying behavior (actions) in regard to ethnic discrimination. However, there are some publications, such as from the perspective of group threat and competition theories (e.g., Olzak, 1994; Olzak et al., 1994; Soule and van Dyke, 1999; Ebert and Okamoto, 2015; Shepherd et al., 2018).

There are a number of field experiments on the influence of ethnicity on behavior, covering issues such as returning “lost letters” (placed there by researchers) or getting someone to lend you something (e.g., Koopmans and Veit, 2014; Zhang et al., 2019; Baldassarri, 2020). However, oftentimes, it is not possible to observe discriminating behavior in real-life situations or to implement (field) experiments on participants, due to ethical considerations. Such studies could jeopardize peoples' physical safety and psychological wellbeing. Therefore, for studying certain discriminating behavior, the next best thing is applying factorial surveys containing a hypothetical situation and inquiring about behavior. This proceeding is described in more detail in the section Data and Methods, subsection Methodology: Factorial survey experiment. Previous methodological research on factorial surveys shows that this approach is suitable for scrutinizing real-life behavior because the reported hypothetical behavior is much alike actual behavior (Rettinger and Kramer, 2009; Hainmueller et al., 2015; Petzold and Wolbring, 2019).

Discrimination as a result of ingroup-outgroup relationships?

Ingroup-outgroup relationships and their influence on behavior have been studied by both social-psychologists and sociologists (e.g., Blau, 1962; Tajfel et al., 1971; Tajfel and Turner, 1979; Jetten et al., 1996; Smelser, 2015). Ingroup members typically rate each other more highly than outgroup members and share common characteristics or interests (Triandis, 1989; Earley, 1993). In regard to ethnic discrimination, much of this research is from the perspective of social-psychology (Zick, 2017). A lot of this research is based on social identity theory (Tajfel, 1978; Tajfel and Turner, 1986). Sociological research also addresses the influences of ingroup-outgroup relationships on behavior (e.g., Parsons, 1951; Blau, 1962; Smelser, 2015). However, while there are some studies that pick up these perspectives, particularly in order to examine deviant behavior (e.g., Kleinewiese and Graeff, 2020), other recent sociological literature picks up the perspective of social identity theory (e.g., Kretschmer and Leszczensky, 2022). Using an integrated interdisciplinary approach, we can utilize the advantages of both perspectives in order to understand how discriminatory behavior can result from ingroup-outgroup relationships. Presumably, people identify with their group (here: people with a common ethnicity), which can cause them to treat people from the outgroup worse than those from their ingroup. This can happen during typical everyday situations that we all encounter regularly. For example: meeting a neighbor. The classical sociological perspective, focusses more on the difference between influences that are oriented toward people in general vs. only toward a specific subgroup (e.g., Parsons, 1951; Blau, 1962; Smelser, 2015). This divide suggests, that we treat people differently based on alleged groups (that we categorized or sorted them into in accordance or contrast to ourselves). While coming at the problem from slightly different angles, sociological and social-psychological perspectives are easily integrated as they both provide a basis for arguing that people will often treat outgroup-members differently than ingroups members. From this viewpoint, ethnic discrimination happens when someone treats a member of an ethnic-outgroup differently from a member of their ethnic-ingroup, based on their ethnicity. The current article is interested in the dynamics of everyday discrimination of people from an ethnic majority against people from an ethnic minority.

Based on these considerations derived from previous research, I expect that, in an everyday encounter between neighbors, a person from an ethnic majority will treat a person from an ethnic minority (outgroup) worse than a person from the ethnic majority (ingroup). In regard to the specific situation analyzed in this article, this means that I assume that an old white man will be more likely to call police if the young man he encounters is a person of color than if the young man is white.

Does high fairness lead to “tattling” on others?

People with high fairness norms are more likely to report other people to authorities (unlike, for example, people with strong loyalty norms). Whistleblowers, for instance, have high fairness norms. Psychological experiments support this assumption (e.g., Dungan et al., 2019). They also show that when fairness norms can be increased in an experiment, reporting to authorities becomes more likely (Waytz et al., 2013; Dungan et al., 2014, 2015). Reporting others to an authority—for alleged or real misdeeds—is colloquially called “to tattle on someone.” Such behavior is usually considered to be negative, particularly toward the person who is reported. The reporting person can be, derogatively, called a “tattletale”. In other words, reporting someone to an authority is often considered to be negative behavior.

Research suggests that fairness norms affect behavior in the context of group dynamics (e.g., during ingroup-outgroup situations) (Tajfel et al., 1971). It follows, that when looking at an everyday situation in which ingroup-outgroup relationships can lead to discriminating behavior, general fairness norms can also have an effect on behavior (cf. Blau et al., 1991)—including on reporting people to authorities (for example, by calling the police). The current article is particularly interested in identifying antecedents that offer potential for behavior-change in real-life (if the antecedent were manipulated/changed, such as increasing fairness norms). Therefore, the integrated interdisciplinary approach in this article includes the dimension of peoples' fairness norms (e.g., Waytz et al., 2013; Dungan et al., 2014, 2015), as a possible influence on their (negative) behavior toward others.

Based on these findings and considerations, I expect that a person with high fairness norms is more likely to report someone else to an authority, than a person with low fairness norms. Applied to the neighborhood situation examined in this article, this means I expect that the old white man will be more likely to call the police on his neighbor when the old man's fairness norms are high than when they are low.

Does high threat lead to “tattling” on others?

When a person perceives a situation that they are in to be threatening, this can affect their attitudes, emotions and actions toward others. When a person feels that someone is behaving dangerously toward them (i.e., they feel threatened), they are more likely to report the situation to an authority, such as the police (e.g., Kääriäinen and Sirén, 2011; Asiama and Zhong, 2022). Threats, both real and perceived, are particularly relevant in situations that include ingroup-outgroup relationships (Kleinewiese and Graeff, 2020), as threat by an outgroup individual can be perceived as threat to one's ingroup (cf. Tajfel, 1978).

Threats and perception of other groups as threatening are also studied in regard to ethnic majority-minority relations. Previous research focusses on negative behavior and attitudes of majorities against minorities as an outcome of threat or competition (e.g., Blumer, 1958; Bobo and Hutchings, 1996). Within the research fields of group threat and competition theories, in the context of integration and discrimination, a number of studies show that high threat makes anti-minority behavior more likely (e.g., Olzak, 1994; Olzak et al., 1994; Soule and van Dyke, 1999; Ebert and Okamoto, 2015; Shepherd et al., 2018). Moreover, in situations in which there is ethnic discrimination, high threat can increase stress and foster a change in behavior (Pease et al., 2020). Psychological research also finds evidence that threat in intergroup situations can lead to discrimination and conflict (Chang et al., 2016). Remarkably, although from diverse fields, the above findings all show that threat and ethnic ingroup-outgroup relationships are closely intertwined. They also suggest that high threat increases reporting-behavior. Hence, threat needs to be included in examining an everyday encounter between neighbors that may lead to discrimination.

Based on these considerations derived from prior research, I expect that a person will be more likely to report someone to an authority the more threatening a situation is. In the particular situation which this article examines, this means that I expect that the old white man will be more likely to call the police when the threat in the situation is higher.

Why the dynamics of antecedents are important when researching discrimination in everyday situations

While the aforementioned literature and expectations point toward interesting first insights on how ethnic ingroup-outgroup relationships, fairness norms and threat may impact a person's behavior toward their neighbor, scrutinizing their deeper dynamics is the most important step toward finding the real-life processes leading toward discriminating behavior among neighbors. Findings from prior research in a number of fields coherently suggest that the ingroup-outgroup effect interacts both with fairness norms and with threat-levels. It seems, that particularistic standards (e.g., ingroup-outgroup) and universalistic standards (e.g., fairness norms) can influence behavior together, i.e., dynamically (cf. Blau, 1962; Rodrigues et al., 2016). Fairness norms can influence behavior in situations with ingroup-outgroup relationships (e.g., Tajfel et al., 1971; Jetten et al., 1996). Specifically, higher fairness norms make discrimination against an outgroup less likely (Jetten et al., 1996). Threats can lead from ingroup-outgroup relationships (that do not always need to be antagonistic) to “us-against-them” attitudes of members of two groups (Rabbie, 1982). This can shift behavior from simply ignoring outgroup-members to being hostile toward them (Chang et al., 2016). The implication of this is that when a situation has higher levels of threat, behavior based on ingroup-outgroup categorization becomes more likely. This can be a result of higher ingroup conformity and/or stronger negative attitudes toward the outgroup (e.g., Riek et al., 2006; Stollberg et al., 2017; Barth et al., 2018). Research on ethnic discrimination indicates that members of ethnic majority groups become more prejudiced toward ethnic minority groups after threatening situations arise, provided the threat is attributed to the minority group (Becker et al., 2011; Schlueter and Davidov, 2013). Majority group members then also display more negative behavior toward minority group members (Frey, 2020).

Summarizing the prior research, it seems that the ingroup-outgroup effect on the negative behavior (toward ethnic minorities) may only be meaningful under certain circumstances (e.g., a high-threat situation) but not under others. It is, therefore, important to conduct in-depth analyses of the dynamics of the ingroup-outgroup relationship and fairness norms or threat, respectively.

Based on the stated considerations and previous literature, I expect that a person is more likely to report someone to an authority based on their outgroup-ethnicity (than if the person were from their ethnic ingroup) in (a) high-threat situations, or, (b) when the reporting person has low fairness norms. In regard to the specific situation examined in this article—an encounter between two neighbors—this means that the old white man is more likely to call the police on the young man if the young man is a person on color (than if he is white) when (a) the situation becomes more threatening, or, (b) the old man has low general fairness norms.

Data and methods

Survey procedure

In January 2021, a factorial survey experiment was implemented in order to assess the antecedents and, particularly, the in-depth dynamics, of everyday discrimination among neighbors. Since everyone has neighbors, a random sample was drawn from the general population of inhabitants in Germany. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, I had to switch from the originally planned in-person paper-pencil questionnaire distribution to a random online distribution. This decision was based on ethical and health concerns, i.e., methods such as random walks could have led to a spread of the disease. The “advertisement” for survey-participation contained a short text and a link to the study. This link led the respondents to the questionnaire, which was created via the survey-platform Unipark. For data security reasons, the places where respondents lived (beyond the country, which is Germany) were not logged or inquired. The conclusions drawn in previous methodological research differ in regard to whether or not online survey samples are less representative and generalizable than offline samples (Best et al., 2001; Gosling et al., 2004). However, methodological research suggests that factorial surveys typically have high external validity, as they can describe realistic situations. As with laboratory experiments from psychology, convenience samples suffice in order to draw conclusions on causality, given that the scenario-vignettes have been randomly distributed to the participants (Auspurg and Hinz, 2015). The respondents were able to select between completing the survey in German, Arabic or Turkish. The latter languages were selected as they cover much of the non-German-speaking inhabitants in Germany, in order to not exclude these groups from the survey (see also Jacobsen et al., 2021). While the sampling did not allow documenting how many people saw the advertisement of the survey, the participation rate of the people who clicked on it lies at 99.53% (N = 637). The 637 participants received four vignette-versions of the survey experimental scenario each (2,548 overall). Due to 18 item non-responses, n = 2,530 vignette responses were gathered (response rate to distributed scenario-versions/-vignettes = 99.29%). The detailed sample composition is shown in the Supplementary Table A5 Respondent-specific variables (e.g., means, standard deviations). In order to achieve high response-rates incentives were offered, as methodical research shows that incentives increase response rates to web/online surveys (Göritz, 2006). The respondents received incentives of 10 € each.

The questionnaire began with a page providing information on the study (including on the intended methods, e.g., receiving several scenario variations) and its terms, such as guaranteed participant anonymity. It then asked the potential participants if they agree to these terms and would like to participate. Only people who agreed were forwarded to the survey. The agreement was checked by a data security expert before survey implementation. The first page was followed by the factorial survey section and a questionnaire on respondent-specific variables (e.g., socio-demographics, discrimination experiences).

The factorial survey scenario was constructed to examine the expectations stated in this article and based on the integrated interdisciplinary framework introduced above. In order to ensure closeness to real-life situations, plausibility and understandability as well as ensure that the vignette treatment-levels are clearly distinct from one another, qualitative pretests were conducted (see, e.g., Auspurg and Hinz, 2015). The information gained from the qualitative pretests was used to improve the factorial survey instrument, before it was implemented in the quantitative study.

Methodology: Factorial survey experiment

This study implemented a factorial survey experiment (Rossi and Anderson, 1982; Jasso, 2006). Methodically, factorial surveys are advantageous as, ideally, they combine the high internal validity of experiments with the high external validity of classic surveys (Auspurg and Hinz, 2015). Since measuring certain behaviors (e.g., violence, corruption, discrimination) in real-life or with experiments is often unethical or unfeasible, measuring such behaviors by means of hypothetical scenarios in the form of factorial surveys is a suitable alternative. Such scenarios describe a hypothetical situation, varying the sections in which the independent variables (treatments/dimensions) are operationalized independently from one another. This is followed by a question for an intended hypothetical action, often by inquiring about the likelihood of the action in the described situation (Dickel and Graeff, 2018; Kleinewiese and Graeff, 2020). But is measuring hypothetical actions in hypothetical situations adequate for drawing conclusions regarding real-life behavior? Hypothetical behavior cannot be assumed to be entirely identical to behavior in real-life under the same conditions. However, methodical research shows that hypothetical experimental survey designs deliver very similar results to the same situations and resulting behavior in real-life (Hainmueller et al., 2015). As put by (Rettinger and Kramer, 2009), factorial survey scenarios are “(…) a good substitute for similar manipulations in the real world when the latter are not possible.” Typically, regression analyses will begin with a model containing only the experimental treatments (independent variables in the scenario) and then continue with a model that amends these with respondent-specific variables (e.g., socio-economic variables, experiences, attitudes) as control-variables. If the effects of the treatments are the same in the model including the control-variables as in the one containing only the treatments, we find support for the premise that the internal validity of the experiment is upheld. This means that the effects are actually and independently measuring the effects of the experimental variables and the respondent-level is not interfering. This is particularly relevant for designs that include individual features (e.g., self-control, morality) as this can control that the measured effects depend on the experiment (hypothetical actor in the scenario) and not on the respondent's characteristics (see Kleinewiese, 2021). Previous research on ethnic discrimination has successfully used factorial surveys as a tool for measuring ethnic discrimination (e.g., Sniderman et al., 1991). It follows, that applying a factorial survey to examine the dynamics of situations including groups of different ethnicities and how these may lead to discriminating behavior is an expedient scientific undertaking.

The current design is a full factorial design, i.e., vignettes are constructed from all combinations of the scenario's treatments' levels. This results in a vignette-universe (total number of vignettes) of 23 × 41 = 32. Each participant randomly received four different versions (four vignettes) of the scenario (different treatment-level combinations), therefore, it is a “within-design.” Since n = 2,530 vignette responses were collected, each scenario-version (vignette) was responded to about 79 times. Table 1 contains the scenario, including its instructions, hypothetical situation and the varied treatments as well as the question on hypothetical behavior (translated into English).

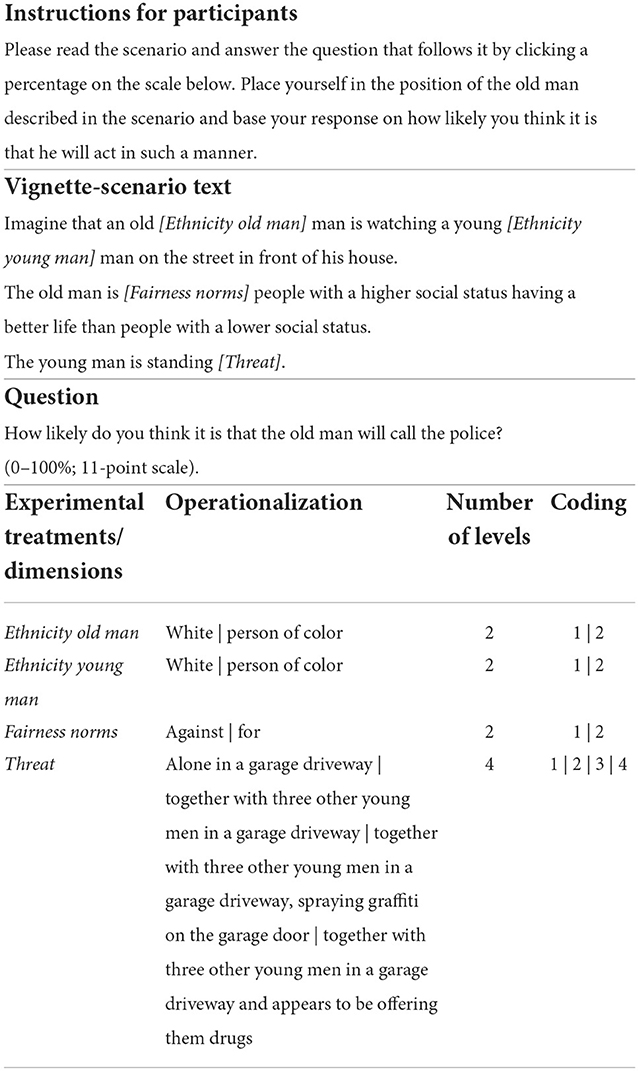

Table 1. The vignette-scenario text, the question and the response (dependent vignette-variable), including the experimental treatments of the factorial survey experiment.

Dependent variable: The likelihood of calling the police on your neighbor

After reading the instructions and the description of the vignette on the hypothetical situation between two neighbors, the participants were asked to assess a question on the behavior of the hypothetical protagonist (an old man living in the neighborhood). They were asked how likely they think it is that the old man will call the police. They responded on an 11-point rating scale ranging from 0 to 100% (coded as 1–11) (see Table 1 for more details on the vignette-scenario). Previous methodical research on measures for independent variables in factorial surveys recommends 11-point rating scales, as they outperform other types of scales. They lead to a smaller number of missing values and higher validity of regression estimates (Sauer et al., 2020). Previous research has successfully applied 11-point rating scales (0–100%) to measure how likely an action of a hypothetical person is (e.g., Dickel and Graeff, 2018; Kleinewiese and Graeff, 2020).

Independent variables: Experimental treatments varied independently and respondent-specific variables as controls

The scenario contains four experimental treatments (independent variables/dimensions). The first one is the ethnicity of the old man (the protagonist of the scenario), the second treatment is the ethnicity of the young man (the other person in the scenario). These treatments are needed in order to measure how the ethnicity of each person affects the likelihood that the old man will call the police. Moreover, it allows for examining ingroup-outgroup effects and dynamics. The third treatment is fairness norms (held by the old man). The fairness norms are operationalized as entitlement norms. While it may seem that this is not directly related to the hypothetical situation “at hand” that is precisely the point. Based on the theoretical framework and forwarded expectation, fairness norms represent “general fairness standards,” which are universalistic in that they are not oriented toward the person's own group but rather applied to everyone, generally (Blau, 1962; Waytz et al., 2013; Smelser, 2015). Therefore, it was important to operationalize the treatment “non-situation-specific” to make sure that the treatment is—in fact—perceived as a universalistic norm by participants. Furthermore, we tested this treatment extensively in our qualitative pretests of the design and no issues were found. The fourth treatment is threat, operationalized as increasingly threatening behavior of the young man (and his peers). This treatment was also tested extensively during the qualitative pretests and the participants found the levels to be clearly distinct and rising (with each level) in perceived threat. Four levels were selected for this treatment in order to gain a more nuanced picture of the dynamics of threat in regard to calling the police than a simple differentiation between threat/no threat would have allowed. This is in line with previous factorial survey experiments using “threat treatments” that show a strong influence of increasing levels of threat on behavior, particularly in ingroup-outgroup situations (Kleinewiese and Graeff, 2020). See Table 1 for more details on the treatments and their levels.

The respondent-specific variables are important for assessing the sample composition. Moreover, they serve as control-variables in regression analyses, to test if internal validity remains intact. As each participant (respondent) assesses several vignettes (within-design), analyses typically differentiate the vignette-level (level 1) and the respondent-level (level 2). The respondent-specific variables are: age, gender, income, citizenship and discrimination experiences. They are described in Supplementary Table A5.

Analytical strategy: Descriptives, multilevel mixed linear regressions and average marginal effects

The first step of the analyses will be checking for correlations between the experimental treatments. There should be no significant correlations, since the effects are designed to be independent from one another (Auspurg and Hinz, 2015). The dependent variable (likelihood of calling the police on the neighbor) is examined descriptively, reporting the mean and standard deviation.

For examining and the dynamics of ingroup-outgroup relationships, fairness norms and threat in regard to behavior in everyday situations between neighbors, I rely on multilevel mixed-effects linear regressions and average marginal effects. Regression analyses on the vignette-level (i.e., effects of the treatments on the dependent variable) allow for estimating the effects of the independent variables without the issue of “real-world” confoundings (Auspurg and Hinz, 2015). With the regression analyses, I can contribute refined insights into the dynamics of ethnic ingroup-outgroup situations and how discrimination can play a role in the behavior of neighbors toward each other.

Multilevel mixed-effects linear models fit the two-level design of this study (vignettes nested in respondents). The intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) calculated for the regressions support this choice of model (see Supplementary Tables A2–A4 for the ICCs of each regression model). Moreover, likelihood-ratio tests of the models are highly significant (p ≤ 0.000). Statistically, this supports the choice of the models, i.e., that they are suitable (Lois, 2015). The models are termed “mixed” because they consist of fixed and random effects—with random deviations in addition to those covered by the overall error term. In the current case, the models have two levels and a random intercept. For the results shown in the subsequent section, the multilevel mixed-effects linear models were implemented in STATA (Raudenbush and Bryk, 2002; Stata, 2019). The models use a maximum likelihood estimator. They have a Gaussian error distribution, with Gaussian within-group errors with one common variance. Constant variance is set for the independent residuals (McCulloch et al., 2008; Stata, 2019).

The core findings are presented in the results section of this article. Additional analyses (e.g., regression models that include both the vignette treatments and the respondent-specific control variables) can be viewed in the Supplementary Tables A2–A4. The first model presented in the results section estimates the main effects of the ethnicity of the young man, the fairness norms and the threat on the likelihood of the old man calling the police for those vignettes in which the old man's ethnicity is “white” (see Figure 1). The selection of this “fraction” of vignettes allows for measuring the “ingroup-outgroup effect” of the majority ethnicity toward the minority. Methodically, this fraction allows for unbiased estimation of the treatment-effects on the dependent variable because the original full factorial design is divided into two halves that are identical in regard to the remaining experimental treatments and their levels. Therefore, methodologically speaking, the vignettes on which the analyses are conducted are, as a fraction, a symmetrical orthogonal design (Dülmer, 2007). The subsequent analyses shown in the “results” section are also conducted with the fraction of vignettes in which the old man's ethnicity is “white.” For the purpose of showing the dynamics of ingroup-outgroup effect, fairness and threat, this article then presents the results of two multilevel mixed-effects linear models estimating the main effects of the treatments and one relevant interaction effect each. The two interaction effects that are of relevance to analyzing the dynamics from the introduced integrated interdisciplinary approach are, firstly, ingroup-outgroup (ethnicity of the young man when the old man is white) and fairness norms and, secondly, ingroup-outgroup (ethnicity of the young man when the old man is white) and threat (see Figure 2). In order to gain a deeper understanding of these dynamics, the average marginal effects are shown in Figures 3, 4.

Results

Descriptives and correlations: Checking the experiment's variables

I start by examining the experiment's variables: the independent variables and the dependent variable. Checking for possible correlations between the independent variables confirms that there are no significant correlations. Scrutinizing the dependent variable descriptively, I find that the mean is 5.695 with a standard deviation of 2.841 (on a response scale ranging from 1 to 11). With this information, I can proceed to the multilevel mixed-effects linear regressions.

At first glance: How the experimental treatments appear to affect the likelihood of an old white man calling the police on his neighbor

In order to gain first insights, it is expedient to look at how the treatments ethnic outgroup/ingroup, fairness norms and threat affect the behavior of the old “white” man. Since the factorial survey situation is alike real life in neighborhoods, the respondents are able to immerse themselves in the situation, slipping into the perspective of the old man. In regard to the fairness norms this means that the respondents perceive themselves at the presented level of fairness when reading a vignette and respond accordingly.

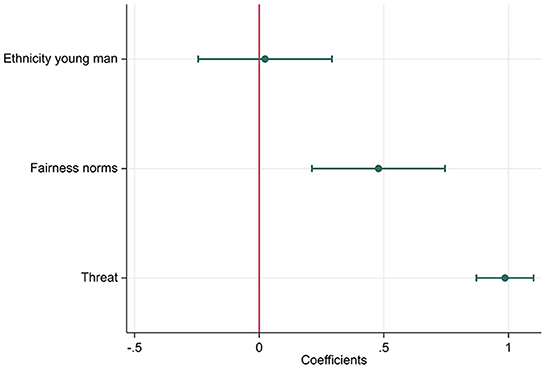

Evidence from prior research supports the expectations that the old white man is more likely to call the police (a) if the young man is a person of color, (b) if the old man generally has higher fairness norms, (c) if the perceived threat in the situation is higher. The results of the multilevel mixed-effects linear regression in Figure 1 show that only two of these expectations seem to be supported (see also Supplementary Table A2, Model 3, in the Appendix). The effect of the young man's ethnicity is positive but not significant. Hence, the expectation that the old man will be more likely to call the police when the young man is a person of color (than when the young man is white) is not substantiated here. This appears to be in contrast to the assumption that people behave discriminatingly toward outgroup members. The old man's fairness norms have the expected positive effect (p < 0.001), i.e., the old man is more likely to call the police on his neighbor when he is generally “fairer” and, concomitantly, oriented toward universalistic standards (that are applied equally to all people). As expected, threat has a strong positive effect on the likelihood of the old man calling the police (p < 0.001), i.e., when the perceived threat increases, so does the likelihood of the old white man calling the police.

Figure 1. Factorial survey treatment-effects on the likelihood of the old white man calling the police, multilevel mixed-effects linear regression.

A second look: What the dynamics between ingroup-outgroup, threat and fairness tell us about what is actually happening

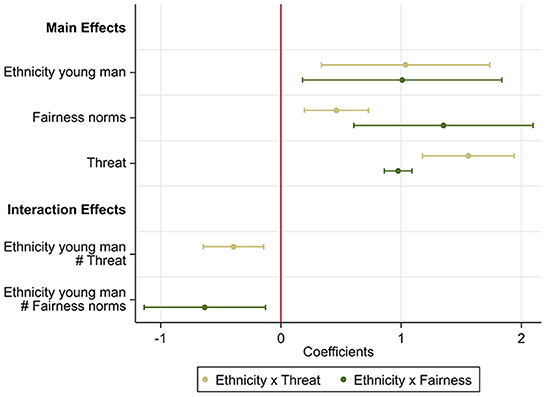

Does this mean that an ingroup-outgroup relationship between the old white man and a person of color young man does not affect how likely the old man is to call the police? Hence, that discrimination does not play an important part in regard to his behavior? Not necessarily. While the results above provide interesting insights, they do not tell us much about how the causes interact with each other. Since in real-life, it is likely that a person will be influenced in his or her behavior more dynamically, the relevant interaction-effects need to be scrutinized in order to find out what is actually happening in regard to ethnic discrimination. As Figure 2 shows (see also Supplementary Table A4, Model 7, in the Appendix), my expectation that a positive effect of the young man's ethnicity on the likelihood of the old white man calling the police (he is more likely to call the police in the outgroup situation, i.e., when the young man is a person of color) will be higher the more threatening a situation becomes, is not confirmed here. In fact, the opposite seems to be the case: The interaction-effect with the young man's ethnicity has a negative sign (p < 0.01). Hence, with increasing threat the effect of the young man's ethnicity on the old man calling the police appears to decrease. Despite this surprising finding for everyday situations between neighbors, the significant effect suggests an influence on how the old man will behave. Figure 2 supports my expectation that (see also Supplementary Table A4, Model 9, in the Appendix) high fairness norms decrease the effect of the ethnic ingroup-outgroup relationship on the old man calling the police. This assumption is backed by the negative significant interaction-effect of the young man's ethnicity and the old man's general fairness norms (p < 0.05). In other words: The effect of the ingroup-outgroup relationship on calling the police on one's neighbor (it is more likely that a majority ethnic group member will call the police on an ethnic minority group member than on a fellow member of the majority) appears to be reduced when the old man has higher fairness norms (as opposed to when he has low fairness norms). Examining the interactions—taking the dynamics of the situation into account—suggests that discrimination against minorities can play a part in neighborhood encounters and behavior. This draws a rather more nuanced picture than the analysis of only the main effects. It shows that under some conditions, ingroup-outgroup relationships are of relevance but not necessarily always and that the interplay and dynamics are of fundamental importance when examining everyday discriminating behavior, for example, among neighbors.

Figure 2. Factorial survey treatments'-interaction-effects on the likelihood of the old white man calling the police, multilevel mixed-effects linear regressions.

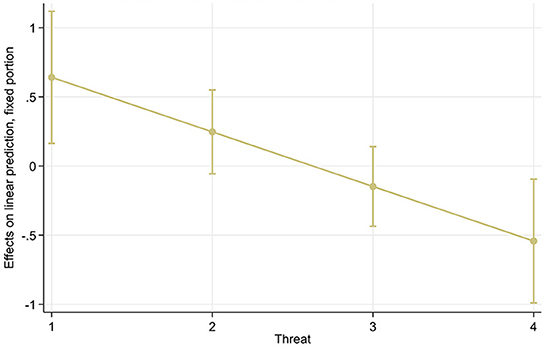

Figure 3. Average marginal effects of the young man's ethnicity, according to threat-level, with 95% confidence intervals.

Into the deep: Expected and unexpected in-depth patterns of dynamics of the ingroup-outgroup relationship, threat and fairness in everyday discrimination among neighbors

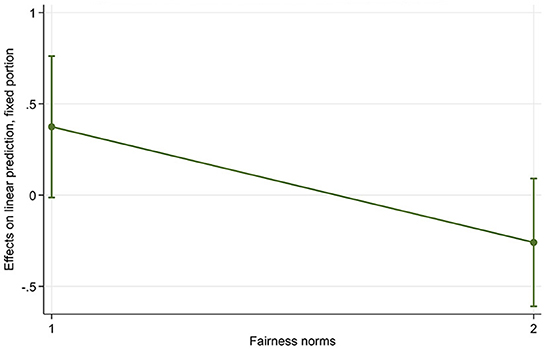

As the interactions studied above indicate, we need to do in-depth analyses in order to better understand the role of ethnic discrimination in the tension field of ingroup-outgroup relationships, fairness norms and threat. In order to go even deeper into the dynamics indicated by the interaction-effects and to understand what they mean for particular circumstances (e.g., when encountering a person who lacks a sense of fairness or a particularly threatening situation) and behavior, we need to scrutinize the interactions' average marginal effects. Figure 3 (for the interaction ethnicity x threat) and Figure 4 (for the interaction ethnicity x fairness norms) depict these average marginal effects. Figure 3 shows a downward trend. When threat is low, the old white man is more likely to call the police if the young man is a person of color than when he is white (ethnic discrimination). As the threat increases one level, the aforementioned effect becomes smaller (but is still positive, i.e., there is still ethnic discrimination against the outgroup). When the threat increases one more level, the effect drops further and becomes negative. Contrary to my expectation, this not only suggests that ethnic discrimination against the outgroup does not play a role at this higher level of threat, it even suggests that the old white man may now be more likely to call the police when the young man is white. In the situation which describes the highest threat (one more level up), this negative effect becomes even stronger. Besides being surprising, these results underline that we need to look at in depth-dynamics in order to understand when and how behavior is affected by ethnic discrimination in specific situations. Figure 4 also shows a negative tendency. As expected, the influence of the young man's ethnicity on calling the police has a positive effect when the old man's fairness norms are low. This suggests that the old white man discriminates against the ethnic outgroup when he is a person who does not generally care about fairness. When the old man's general fairness norms are high, however, the effect of the young man's ethnicity on calling the police shows a negative effect. This shows when the old man generally cares about fairness, he is not likely to discriminate against a person from the ethnic outgroup. In fact, he may even be more likely to call the police when the person is from his ethnic ingroup. The results clearly demonstrate—at least in the case of a typical situation between neighbors—that when examining behavior affected by ethnic discrimination (based on ingroup-outgroup relationships) we need to take a nuanced look at the dynamics with other relevant factors (such as fairness norms and threat-level). In doing so, one can uncover “hidden” discrimination that we cannot identify by means of more superficial analyses. This is highly relevant in the quest of reducing discrimination in everyday encounters.

Figure 4. Average marginal effects of the young man's ethnicity, according to fairness norm-level, with 95% confidence intervals.

Discussion

Research on discrimination against ethnic minorities focusses on discrimination in housing markets, labor markets, criminal justice and institutions (e.g., Heath et al., 2008; Wu, 2016; Quillian et al., 2017, 2019, 2020; Horr et al., 2018; Auspurg et al., 2019; Sawert, 2020; Zschirnt, 2020). But what about everyday discrimination; what about situations that many or all people in a country may encounter regularly? This is an area of discrimination research that, despite a small number of recent publications (e.g., Wenz and Hoenig, 2020; Sylvers et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022) remains under-researched. Moreover, there is a complete gap in this field on everyday encounters between neighbors. This article contributes toward filling this gap in research by examining the antecedents and dynamics of discriminating behavior of neighbors by means of a factorial survey experiment. In addition, its integrated interdisciplinary approach provides a foundation, on which future research on everyday discrimination can build.

By taking the dynamics of everyday situations involving negative behavior toward others into account, firstly, I show that discriminating behavior in encounters between neighbors is brought about in the interplay of relevant factors. Looking only at the main effects, discriminating behavior cannot be identified because the ingroup-outgroup relationship based on ethnicities does not show a significant effect on how likely the negative action of one neighbor toward another is. However, the significant interaction-effects and their average marginal effects show that discriminating behavior does, in fact, take place—in specific situations (depending on fairness norms and threat-levels). Secondly, the results of the average marginal effects show that these interactions are highly dynamic, i.e., discriminating behavior against a person from the ethnic outgroup is likely in low-threat situations but behaving negatively toward a neighbor from one's ingroup appears to be more likely in highly threatening situations.

This also helps to answer the research questions presented in the introduction. The first question was how ingroup-outgroup relationships, fairness norms and threat-levels influence negative behavior toward a neighbor? The answer is simple: dynamically; the main effects show that fairness and threat have strong positive influences (i.e., one is more likely to report a neighbor when one has high fairness norms or the situation is more threatening). However, the more in-depth analyses—as discussed above—show patterns that are highly specific to the interplay of influences in the situation. The second question inquired: When is such behavior discriminating? Reporting a neighbor to authorities is discriminating when it is more likely that one will report the neighbor if he is from the ethnic outgroup than if he is from the ethnic ingroup. The third question was on what the dynamics between ingroup-outgroup, fairness and threat are that make discriminating behavior against a neighbor more likely. In the everyday encounter between neighbors that this article focusses on, fairness norms play the role we would expect in that outgroup-discriminating behavior is less likely when the “behaving person” has high general fairness norms than when that person has low general fairness norms. In other words: High fairness makes the discriminating behavior less likely. Threat, on the other hand, shows more unexpected dynamics. From previous literature we would expect that higher threat makes discriminating behavior more likely (e.g., Rabbie, 1982; Chang et al., 2016; Frey, 2020). However, the in-depth analyses performed on the neighborhood-scenario suggest that (at least during everyday encounters between neighbors) the outgroup-discriminating behavior appears to happen when the situation is not threatening (or threat is rather low). This effect is strongest, when there is no threat at all. On the other hand, when threat is high, behaving negatively toward one's ingroup is more likely (than against the outgroup). These surprising findings highlight the importance of examining in-depth dynamics of common everyday situations that could lead to discriminating behavior; they show—unexpectedly—reducing perceived threat is not a solution for discrimination against an ethnic outgroup in an everyday encounter between neighbors. However, as expected, increasing fairness would be a solution, i.e., could help reduce the likelihood of behavior based on ethnic discrimination. These findings also suggest that macro-perspectives (while interesting for a number of research questions on discrimination) fall short in regard to comprehending situational dynamics. Something that is paramount for conducting research that can inform policy-changes and other interventions (Laouénan and Rathelot, 2022). This is because—while studies aiming to determine antecedents more generally are valuable to science—they run the risk of “over generalizing” causalities, which may vary from situation to situation (cf. Bar-Tal, 2006). It is suggested that future research should amend such perspectives with studies that follow the current approach: Studies that interdisciplinarily examine one specific everyday situation and how (based on previous research, available methodologies and survey-resources) important factors dynamically effect discrimination.

My theoretical approach to studying everyday discrimination goes beyond most previous approaches by utilizing previous research from both sociology and social-psychology and integrating their respective strengths. For instance, in regard to ingroup-outgroup relationships, it draws on social identity theory and particularism-universalism theory which both address ingroup-outgroup categorizations (e.g., Parsons, 1951; Blau, 1962; Tajfel, 1978; Tajfel and Turner, 1986; Smelser, 2015). It also includes integrating ideas from integration research's threat and competition theory with research on how threats affect behavior more generally (e.g., Blumer, 1958; Olzak, 1994; Olzak et al., 1994; Bobo and Hutchings, 1996; Soule and van Dyke, 1999; Kääriäinen and Sirén, 2011; Ebert and Okamoto, 2015; Shepherd et al., 2018; Asiama and Zhong, 2022). Moreover, amending the aforementioned with findings from social-psychological experimental research on how fairness norms affect behavior (e.g., Tajfel et al., 1971; Bar-Tal, 2006; Waytz et al., 2013; Dungan et al., 2014, 2015). Integrating these approaches into one framework, allows studying the dynamics at play. None of the theories and approaches—by themselves—could be the foundation of empirical research that is able to examine the dynamics of ethnic discrimination in an everyday situation. Hence, the current approach develops the research field further by showing that the whole is more than the sum of its parts, i.e., taken together we can determine dynamics of discrimination. The results of this study support that this has an added value and that future studies on everyday discrimination should consider using this framework or a similar one, one that includes relevant antecedents at the level of the individual, group and setting. Such studies may also want to compare the dynamics of everyday discriminating behavior toward neighbors with the dynamics of discriminating behavior in other everyday situations (such as shopping for groceries), in order to compare how similar (or different) such dynamics are across situations.

A limitation of this study is that the selected situation between neighbors is fixed in regard to a number of situational features. For example, I do not vary the gender of the neighbors. However, previous research on gender and inter-religion friendships, for instance, suggests that religion-based ingroup-outgroup relationships can differ based on gender-compositions (Kretschmer and Leszczensky, 2022). Hence, it seems feasible that ethnic ingroup-outgroup discrimination may also vary according to gender-composition. Future research should conduct an in-depth examination of this proposition. Moreover, environmental factors that contribute to implicit biases, such as substantial changes in ethnic diversity (Kawalerowicz, 2021), should also be included in future experimental surveys. Another limitation is that only two ethnic groups (white/person of color) are included. Despite being aware of these limitations, I selected this design because of methodological issues that would otherwise have arisen, such as plausibility issues and possible biases in the results (see Shamon et al., 2019). This is, for instance, due to the complex design that was necessary for modeling the ingroup-outgroup relationship and its impact on the experimental design (e.g., size of the full factorial, orthogonality and level balance) (cf. Dülmer, 2007). Future methodological research may want to explore solutions to these issues, allowing for more complex designs and analyses that can include additional treatments (such as gender) that are likely to affect discrimination, or additional levels of ethnicity.

This article provides empirical results which feed information that is important for policymakers and other relevant stakeholders aiming to reduce ethnic discrimination during everyday encounters between neighbors. The primary recommendation that can be derived from the current study is that to reduce discrimination against neighbors from ethnic minorities, one should increase general fairness—both its salience in specific situations and sustainably as personal norms—for example, by educating students in regard to ethics and general standards of fairness.

Data availability statement

The dataset presented in this article is currently not publicly available. However, the author is able to share the vignette-data with other scientists upon request.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

The data presented in this article is from a project funded by the German Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth (BMFSFJ) as part of the Research Association Discrimination and Racism (FoDiRa). The publication of this article was funded by the Mannheim Centre for European Social Research (MZES), University of Mannheim.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fhumd.2022.1038252/full#supplementary-material

References

Asiama, A. A., and Zhong, H. (2022). Victims rational decision: a theoretical and empirical explanation of dark figures in crime statistics. Cogent Soc. Sci. 8, 1–15. doi: 10.1080/23311886.2022.2029249

Auer, D., and Ruedin, D. (2022). How one gesture curbed ethnic discrimination. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 1–22. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12547

Auspurg, K., and Hinz, T. (2015). Factorial Survey Experiments. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Auspurg, K., Schneck, A., and Hinz, T. (2019). Closed doors everywhere? A meta-analysis of field experiments on ethnic discrimination in rental housing markets. J. Ethnic. Migration Studies 45, 95–114. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2018.1489223

Baldassarri, D. (2020). Market integration accounts for local variation in generalized altruism in a nationwide lost-letter experiment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 117, 2858–2863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1819934117

Bar-Tal, D. (2006). “Bridging between micro and macro perspectives in social psychology,” in Bridging Social Psychology: Benefits of Transdisciplinary Approaches, ed. P. A. M. van Lange (London: Taylor & Francis), 341–346.

Barth, M., Masson, T., Fritsche, I., and Ziemer, C.-T. (2018). Closing ranks: Ingroup norm conformity as a subtle response to threatening climate change. Group Proc. Intergroup Relat. 21, 497–512. doi: 10.1177/1368430217733119

Becker, J. C., Wagner, U., and Christ, O. (2011). Consequences of the 2008 financial crisis for intergroup relations: the role of perceived threat and causal attributions. Group Proc. Intergroup Relat. 14, 871–885. doi: 10.1177/1368430211407643

Best, S. J., Krueger, B., Hubbard, C., and Smith, A. (2001). An assessment of the generalizability of internet surveys. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 19, 131–145. doi: 10.1177/089443930101900201

Blau, P. M. (1962). Operationalizing a conceptual scheme: the universalism-particularism pattern variable. Am. Sociol. Rev. 27, 159–169. doi: 10.2307/2089672

Blau, P. M., Ruan, D., and Ardelt, M. (1991). Interpersonal choice and networks in China. Soc. Forces 69, 1037–1062. doi: 10.2307/2579301

Blumer, H. (1958). Race prejudice as a sense of group position. Pacific Soc. Rev. 1, 3–7. doi: 10.2307/1388607

Bobo, L., and Hutchings, V. L. (1996). Perceptions of racial group competition: Extending Blumer's theory of group position to a multiracial social context. Am. Sociol. Rev. 61, 951–972. doi: 10.2307/2096302

Chang, L. W., Krosch, A. R., and Cikara, M. (2016). Effects of intergroup threat on mind, brain, and behavior. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 11, 69–73. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.06.004

Dickel, P., and Graeff, P. (2018). Entrepreneurs' propensity for corruption: a vignette-based factorial survey. J. Bus. Res. 89, 77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.03.036

Diekmann, D., and Fereidooni, K. (2019). Diskriminierungs- und Rassismuserfahrungen geflüchteter menschen in deutschland: ein forschungsüberblick. Z'Flucht 3, 343–360. doi: 10.5771/2509-9485-2019-2-343

Dülmer, H. (2007). Experimental plans in factorial surveys: random or quota design? Sociol. Methods Res. 35, 382–409. doi: 10.1177/0049124106292367

Dungan, J., Waytz, A., and Young, L. (2014). Corruption in the context of moral trade-offs. J. Interdiscipl. Eco. 26, 97–118. doi: 10.1177/0260107914540832

Dungan, J., Waytz, A., and Young, L. (2015). The psychology of whistleblowing. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 6, 129–133. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.07.005

Dungan, J. A., Young, L., and Waytz, A. (2019). The power of moral concerns in predicting whistleblowing decisions. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 85, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2019.103848

Earley, P. C. (1993). East meets west meets mideast: further explorations of collectivistic and individualistic work groups. Acad. Manag. J. 36, 319–348. doi: 10.2307/256525

Ebert, K., and Okamoto, D. (2015). Legitimating contexts, immigrant power, and exclusionary actions. Soc. Probl. 62, 40–67. doi: 10.1093/socpro/spu006

Esses, V. M., and Hamilton, L. K. (2021). Xenophobia and anti-immigrant attitudes in the time of COVID-19. Group Proc. Intergroup Relat. 24, 253–259. doi: 10.1177/1368430220983470

Fetzer, J. S. (2000). Public Attitudes Toward Immigration in the United States, France, and Germany. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Frey, A. (2020). ‘Cologne changed everything'—The effect of threatening events on the frequency and distribution of intergroup conflict in Germany. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 36, 684–699. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcaa007

Göritz, A. S. (2006). Incentives in web studies: methodological issues and a review. Int. J. Int. Sci. 1, 58–70.

Gosling, S. D., Vazire, S., Srivastava, S., and John, O. P. (2004). Should we trust web-based studies? A comparative analysis of six preconceptions about internet questionnaires. Am. Psychol. 59, 93–104. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.2.93

Hainmueller, J., Hangartner, D., and Yamamoto, T. (2015). validating vignette and conjoint survey experiments against real-world behavior. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 2395–2400. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1416587112

Heath, A. F., Rothon, C., and Kilpi, E. (2008). the second generation in Western Europe: Education, unemployment, and occupational attainment. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 34, 211–235. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134728

Hedström, P., and Ylikoski, P. K. (2014). “Analytical sociology and rational choice theory,” in Analytical Sociology: Actions and Networks, ed. G. Manzo (Chichester: John Wiley & Sons), 53–70.

Horr, A., Hunkler, C., and Kroneberg, C. (2018). Ethnic discrimination in the German housing market: a field experiment on the underlying mechanisms. Zeitschrift für Soziol. 47, 134–146. doi: 10.1515/zfsoz-2018-1009

Jacobsen, J., Krieger, M., Schikora, F., and Schupp, J. (2021). Growing potentials for migration research using the German socio-economic panel study. Jahrbücher. National. Statistik 241, 527–549. doi: 10.1515/jbnst-2021-0001

Jasso, G. (2006). Factorial survey methods for studying beliefs and judgments. Sociol. Methods Res. 34, 334–423. doi: 10.1177/0049124105283121

Jedinger, A., and Eisentraut, M. (2020). Exploring the differential effects of perceived threat on attitudes toward ethnic minority groups in Germany. Front. Psychol. 10, 1–9. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02895

Jetten, J., Spears, R., and Manstead, A. S. R. (1996). Intergroup norms and intergroup discrimination: distinctive self-categorization and social identity effects. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 71, 1222–1233. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.71.6.1222

Kääriäinen, J., and Sirén, R. (2011). Trust in the police, generalized trust and reporting crime. Eur. J. Criminol. 8, 65–81. doi: 10.1177/1477370810376562

Kawalerowicz, J. (2021). Too many immigrants: How does local diversity contribute to attitudes toward immigration? Acta Sociol. 64, 144–165. doi: 10.1177/0001699320977592

Kleinewiese, J. (2021). Good people commit bad deeds together: a factorial survey on the moral antecedents of situational deviance in peer groups. Deviant Behav. 43, 1–12. doi: 10.1080/01639625.2021.1990739

Kleinewiese, J., and Graeff, P. (2020). Ethical decisions between the conflicting priorities of legality and group loyalty: Scrutinizing the “code of silence” among volunteer firefighters with a vignette-based factorial survey. Deviant Behav. 4, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/01639625.2020.1738640

Koopmans, R., and Veit, S. (2014). Cooperation in ethnically diverse neighborhoods: a lost-letter experiment. Polit. Psychol. 35, 379–400. doi: 10.1111/pops.12037

Kretschmer, D., and Leszczensky, L. (2022). In-group bias or out-group reluctance? The interplay of gender and religion in creating religious friendship segregation among Muslim youth. Soc. Forces 100, 1307–1332. doi: 10.1093/sf/soab029

Lahav, G. (2004). Immigration and Politics in the New Europe: Reinventing Borders. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Laouénan, M., and Rathelot, R. (2022). Can information reduce ethnic discrimination? Evidence from Airbnb. Am. Eco. J. 14, 107–132. doi: 10.1257/app.20190188

Laurence, J., Schmid, K., and Hewstone, M. (2019a). Ethnic diversity, ethnic threat, and social cohesion: (re)-evaluating the role of perceived out-group threat and prejudice in the relationship between community ethnic diversity and intra-community cohesion. J. Ethnic Migrat. Stud. 45, 395–418. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2018.1490638

Laurence, J., Schmid, K., Rae, J. R., and Hewstone, M. (2019b). Prejudice, contact, and threat at the diversity-segregation nexus: a cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis of how ethnic out-group size and segregation interrelate for inter-group relations. Soc. Forces 97, 1029–1066. doi: 10.1093/sf/soy079

Lois, D. (2015). Mehrebenenanalyse mit STATA: Grundlagen und Erweiterungen. Munich: Universität der Bundeswehr München.

Marques, J. M., Abrams, D., Paez, D., and Martinez-Taboada, C. (1998). The role of categorization and in-group norms in judgments of groups and their members. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 75, 976–988. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.75.4.976

McCulloch, C. E., Searle, S. R., and Neuhaus, J. M. (2008). Generalized, Linear, and Mixed Models. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

McGuire, L., Manstead, A. S. R., and Rutland, A. (2017). Group norms, intergroup resource allocation, and social reasoning among children and adolescents. Dev. Psychol. 53, 2333–2339. doi: 10.1037/dev0000392

McLaren, L. M. (2003). Anti-immigrant prejudice in Europe: contact, threat perception, and preferences for the exclusion of migrants. Soc. Forces 81, 909–936. doi: 10.1353/sof.2003.0038

Mujcic, R., and Frijters, P. (2021). The colour of a free ride. Eco. J. 131, 970–999. doi: 10.1093/ej/ueaa090

Okamoto, D., and Ebert, K. (2016). Group boundaries, immigrant inclusion, and the politics of immigrant–native relations. Am. Behav. Sci. 60, 224–250. doi: 10.1177/0002764215607580

Olzak, S. (1994). The Dynamics of Ethnic Competition and Conflict. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Olzak, S., Shanahan, S., and West, E. (1994). School desegregation, interracial exposure, and antibusing activity in contemporary urban America. Am. J. Sociol. 100, 196–241. doi: 10.1086/230503

Pager, D., and Shepherd, H. (2008). The sociology of discrimination: racial discrimination in employment, housing, credit, and consumer markets. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 34, 181–209. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.33.040406.131740

Pease, M., Birgin, A., Quiroga, K., Reardon, N., Leininger, A., and Davis, K. (2020). Examining Cognitive-Affective Reactivity to Racial Stigma: Implications for Risk Behavior. Maryland, MD: Digital Repository at the University of Maryland.

Petzold, K., and Wolbring, T. (2019). What can we learn from factorial surveys about human behavior? A validation study comparing field and survey experiments on discrimination. Methodology 15, 19–30. doi: 10.1027/1614-2241/a000161

Quillian, L. (1995). Prejudice as a response to perceived group threat: Population composition and anti-immigrant and racial prejudice in Europe. Am. Sociol. Rev. 60, 586–611. doi: 10.2307/2096296

Quillian, L., Heath, A., Pager, D., Midtbøen, A., Fleischmann, F., and Hexel, O. (2019). do some countries discriminate more than others? Evidence from 97 field experiments of racial discrimination in hiring. Sociol. Sci. 6, 467–496. doi: 10.15195/v6.a18

Quillian, L., Lee, J. J., and Honoré, B. (2020). Racial discrimination in the U.S. housing and mortgage lending markets: a quantitative review of trends, 1976–2016. Race. Soc. Probl. 12, 13–28. doi: 10.1007/s12552-019-09276-x

Quillian, L., Pager, D., Hexel, O., and Midtbøen, A. H. (2017). Meta-analysis of field experiments shows no change in racial discrimination in hiring over time. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 10870–10875. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1706255114

Rabbie, J. M. (1982). “The effects of intergroup competition and cooperation on intragroup and intergroup relationships,” in Cooperation and Helping Behavior, ed. V. J. Derlega (New York, NY: Academic Press), 123–149.

Raudenbush, S. W., and Bryk, A. S. (2002). Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Rettinger, D. A., and Kramer, Y. (2009). Situational and personal causes of student cheating. Res. High. Educ. 50, 293–313. doi: 10.1007/s11162-008-9116-5

Riek, B. M., Mania, E. W., and Gaertner, S. L. (2006). Intergroup threat and outgroup attitudes: a meta-analytic review. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 10, 336–353. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr1004_4

Rodrigues, R. B., Rutland, A., and Collins, E. (2016). “The multi-norm structural social-developmental model of children's intergroup attitudes: integrating intergroup-loyalty and outgroup fairness norms,” in The Social Developmental Construction of Violence and Intergroup Conflict, eds. J. Vala, S. Waldzus, and M. M. Calheiros (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 219–246.

Rossi, P. H., and Anderson, A. B. (1982). “The factorial survey approach: an introduction,” in Measuring Social Judgments: The Factorial Survey Approach, eds. P. H. Rossi, and S. L. Nock (Beverly Hills, CA: SAGE publications, Incorporated), 15–67.

Sauer, C., Auspurg, K., and Hinz, T. (2020). Designing multi-factorial survey experiments: effects of presentation style (text or table), answering scales, and vignette order. Methods Data Anal. 14, 195–214. doi: 10.12758/mda.2020.06

Sawert, T. (2020). Understanding the mechanisms of ethnic discrimination: a field experiment on discrimination against Turks, Syrians and Americans in the Berlin shared housing market. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 46, 3937–3954. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2019.1577727

Schlueter, E., and Davidov, E. (2013). Contextual sources of perceived group threat: Negative immigration-related news reports, immigrant group size and their interaction, Spain 1996–2007. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 29, 179–191. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcr054

Shamon, H., Dülmer, H., and Giza, A. (2019). The factorial survey: the impact of the presentation format of vignettes on answer behavior and processing time. Sociol. Methods Res. 51, 1–43. doi: 10.1177/0049124119852382

Shepherd, L., Fasoli, F., Pereira, A., and Branscombe, N. R. (2018). The role of threat, emotions, and prejudice in promoting collective action against immigrant groups. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 48, 447–459. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2346

Smelser, N. J. (2015). Sources of unity and disunity in sociology. Am. Sociol. 46, 303–312. doi: 10.1007/s12108-015-9260-2

Sniderman, P. M., Piazza, T., Tetlock, P. E., and Kendrick, A. (1991). The new racism. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 35, 423–447. doi: 10.2307/2111369

Soule, S. A., and van Dyke, N. (1999). Black church arson in the United States, 1989-1996. Ethn. Racial Stud. 22, 724–742. doi: 10.1080/014198799329369

Stata (2019). Stata Multilevel Mixed-Effects Reference Manual Release 16. College Station, TX: Stata Press.

Stollberg, J., Fritsche, I., and Jonas, E. (2017). The groupy shift: conformity to liberal in-group norms as a group-based response to threatened personal control. Soc. Cogn. 35, 374–394. doi: 10.1521/soco.2017.35.4.374

Sylvers, D., Taylor, R. J., Barnes, L., Ifatunji, M. A., and Chatters, L. M. (2022). Racial and ethnic differences in major and everyday discrimination among older adults: African Americans, black caribbeans, and non-latino whites. J. Aging Health 34, 460–471. doi: 10.1177/08982643221085818

Tajfel, H. (1978). Differentiation Between Social Groups: Studies in the Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. New York, NY: Academic Press.

Tajfel, H., Billig, M. G., Bundy, R. P., and Flament, C. (1971). Social categorization and intergroup behaviour. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 1, 149–178. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2420010202

Tajfel, H., and Turner, J. (1979). “An integrative theory of intergroup conflict,” in Organizational Identity: A Reader, eds. M. J. Hatch, and M. Schultz (New York, NY: Oxford University Press).

Tajfel, H., and Turner, J. C. (1986). “The social identity theory of intergroup behavior,” in Psychology of Intergroup Relations, eds. S. Worchel, and W. G. Austin (Chicago: Nelson-Hall), 7–24.

Triandis, H. C. (1989). The self and social behavior in differing cultural contexts. Psychol. Rev. 96, 506–520. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.96.3.506

Waytz, A., Dungan, J., and Young, L. (2013). The whistleblower's dilemma and the fairness–loyalty tradeoff. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 49, 1027–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2013.07.002

Wenz, S. E., and Hoenig, K. (2020). Ethnic and social class discrimination in education: experimental evidence from Germany. Res. Soc. Stratif. Mobil. 65, 1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.rssm.2019.100461

Wilder, D. A., and Shapiro, P. N. (1984). Role of out-group cues in determining social identity. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 47, 342–348. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.47.2.342

Wu, J. (2016). Racial/ethnic discrimination and prosecution. Crim. Justice Behav. 43, 437–458. doi: 10.1177/0093854815628026

Zhang, N., Aidenberger, A., Rauhut, H., and Winter, F. (2019). Prosocial behaviour in interethnic encounters: evidence from a field experiment with high- and low-status immigrants. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 35, 582–597. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcz030

Zhang, N., Gereke, J., and Baldassarri, D. (2022). Everyday discrimination in public spaces: a field experiment in the Milan metro. Eur. Soc. Rev. 38, 1–16. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcac008

Zick, A. (2017). “Sozialpsychologische diskriminierungsforschung,” in Handbuch Diskriminierung, eds. A. Scherr, A. El-Mafaalani, and G. Yüksel (Wiesbaden: Springer VS), 59–80.

Keywords: ingroup-outgroup, ethnic discrimination, fairness norms, threat, everyday discrimination, discriminating behavior, factorial survey

Citation: Kleinewiese J (2022) Ethnic discrimination in neighborhood ingroup-outgroup encounters: Reducing threat-perception and increasing fairness as possible solutions. Front. Hum. Dyn. 4:1038252. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2022.1038252

Received: 06 September 2022; Accepted: 07 November 2022;

Published: 16 December 2022.

Edited by:

Yuliya Kosyakova, Institute for Employment Research (IAB), GermanyReviewed by:

Stephan Dochow-Sondershaus, Freie Universität Berlin, GermanyNeli Demireva, University of Essex, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2022 Kleinewiese. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Julia Kleinewiese, a2xlaW5ld2llc2VAdW5pLW1hbm5oZWltLmRl