94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Hum. Dyn., 18 January 2022

Sec. Dynamics of Migration and (Im)Mobility

Volume 3 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fhumd.2021.778385

This article is part of the Research TopicSexual and Reproductive Health in Forced MigrationView all 4 articles

Turkey has the highest number of refugees in the world and is currently home to 3.7 million Syrians who had to flee from their country due to the conflict that started in 2011. This paper aims to focus on the fertility and marriage preferences of Syrian refugees by using a widely used qualitative research method Focus Group Discussions. The main findings revealed that socio-demographic indicators, the departure and arrival conditions in home and host country and the current place of residence had affected how families and individuals adjusted themselves and how they changed their fertility and marriage plans since their arrival in Turkey. Yet, the main findings also showed that while forced migration caused normative changes on some, some others reacted and saw these changes just as a temporary adjustment.

Turkey has the highest number of refugees1 in the world and is currently a host to 3.7 million Syrians who had to flee from the conflict that started in 2011. The Syrian refugee crisis had a lot of attention on an international scale—not only because of its political importance but also for having one of the highest numbers of refugees in global history. As a result, many researchers, academicians and international organizations published on a variety of subjects focusing on the Syrian refugees. Despite the high number of publications and special issues about Syrian refugees including subjects such as policy-making, health, social protection and security (Tsourapas, 2019; Munajed and Ekren, 2020; Bozdag et al., 2021; Kurt et al., 2021), only a few them were focusing on the changes on fertility and marriage preferences (Korri et al., 2020; Mirwais et al., 2020; Sieverding et al., 2020; Çöl et al., 2020; Al Akash and Chalmiers, 2021).

When the conflict in Syria started in 2011, the country of destination and the way people left the country highly differed which resulted in a selective migration. While wealthier families had access to different modes of transportation, many others crossed the borders by foot to the closest neighbouring country i.e., Turkey, Jordan or Lebanon. The highest number of arrivals in Turkey started in 2013 and stabilized in 2016 until ISIS triggered a new wave of arrivals in 2017 (DGMM, 2021). The border crossing from Syria still continues today though in less significant numbers. Upon their arrival in Turkey, all Syrians were eligible for “temporary protection” which is a residence permit to stay in Turkey to respond to this massive influx (DGMM, 2014). This permit also gave them access to free health and education services in the city they registered.

Concerning the location of the refugees, most of them are spread all around Turkey, where metropolitan cities of Turkey and the bordering cities with Syria host more than half of them. Turkey is a vast land that lies on two continents with a surface of 783,000 square kilometres that is more than twice the size of Germany. This broad territory hosts a very diverse population of 82 million inhabitants. The norms and customs of fertility and marriage in western metropolises such as Istanbul or Izmir strongly differ from those in smaller eastern towns at the Syrian border. Thus, this shows the importance of geographical location that can impact the refugee households in a certain way as their integration process will be slightly different depending on where they reside.

The literature on the fertility of migrant populations can be helpful to understand the fertility and marriage dynamics of Syrians since their arrival in Turkey. Research on this topic shows that migrants might have a particular fertility profile, marked by a postponing of births after arrival in the host country (Goldstein, 1973; Goldstein and Goldstein, 1981; Hervitz, 1985; Jensen and Ahlburg, 2004; Kulu, 2005; Lindstrom and Giorguli Saucedo, 2002; Toulemon, 2004). As a result, in most cases, emigrants tend to have fewer children than non-migrants before the migration period and more children in the years following settlement due to disruption. Research focusing more specifically on the fertility of refugees i.e., people who had not prepared their emigration for a long time but who had to leave their place of origin quickly, shows that this link between the plan to have children and the (non) migratory project is less systematic in this case (Agadjanian, 2018). Among them, some research examines short-term fertility after departure (Holck and Cates, 1982; Hill, 2004; Randall, 2004), considering, for example, the separation of couples and the absence of coitus, rape and sexual violence, physical and mental stress and its potential effects on losses. In contrast, other studies focus on the fertility of refugees in the longer term by looking at what happens to fertility preferences after arrival (Agadjanian, 2018; Avogo, 2008; Rumbault and Weeks, 1986). In that sense, the findings from the research on the fertility preferences of migrants in the long-term can still be valid for the case of forced migration, which suggests the fertility tend to converge with the host population (Lee and Pol, 1993; Fargues, 2000), and often resulting in a faster decrease in the level of fertility among emigrants than among the sedentary population remaining in the country of origin. Overall, in the studies mentioned above, refugees are studied as a monolithic block. On the contrary, the aim here is to situate representations, norms and practices by taking into account the generational differences, gender, social origin and the temporality of the pathways, situations which will make it possible to look not only at fertility practices and norms but also at matrimonial norms and practices, which remain much less studied up to now. The spatial separation of refugee populations in camps greatly reduces interaction with the host population and the liability of convergence of norms (Fargues, 2000). The fact that the population studied in this article lives outside the camps, on the contrary, increases the likelihood of interactions with the host population.

Even prior to the conflict, contemporary Syria was highly varied in terms of family and household compositions to a large extent which included rural-urban habitation, class background and ethnic and religious affiliation. Despite these differences, the general understanding and the acceptance of how marriages and/or parenthood should be was confirmed by many Syrian families (Rabo, 2008). In a 2016 research focusing on the marital practices in Syria before the conflict, Kastrinou suggests that marriage practices become the more intimate and strong plot of gendered, classed and religious struggles that are faced by all Syrian households (Kastrinou, 2016). It has been also showed that the overall 30 per cent of urban and 40 per cent of rural marriages were kindred marriages, which shows that many families were staying in their traditional ethnic and religious circle by doing so (Othman and Saadat, 2009).

Prior to war, fertility rates were already decreasing in Syria which was 5.1 in the 1990s and by 2009, it was decreased to 3.8 (Çağatay et al., 2020; Sieverding et al., 2019). Concerning child marriages, 2009 PAPFAM results showed that 8.4 per cent of Syrians were married under 18 (Abdulrahim et al., 2017). Since their arrival in Turkey after 2011, there is a chance that the fertility and marriage preferences of Syrian households changed due to forced migration along with the other habits due to cultural and economic differences in the country of arrival. Also, there has been a potential increase in reproductive health problems due to war and poverty caused by sexual abuse and rape, all kinds of violence and pregnancies as a result of undesired but forced or obliged marriages including rapes (Cevirme et al., 2015).

The current report published by UNICEF along with other humanitarian partners shows that child marriages were on the rise among Syrian refugees in the MENA region (UNICEF, 2021). The main reason for the increase of child marriages in the region is about how it is used as a survival strategy for Syrian families and a means to build patriarchal domination over girls’ bodies and sexuality (Yaman Sözbir et al., 2021). The child marriages were increased as various research demonstrates in Lebanon, Turkey and Jordan (Amiri et al., 2020; Bartels et al., 2018; Bartels et al., 2021; Cherri et al., 2017; Öztürk et al., 2020). Current literature also shows that the Syrian adolescent refugees in Turkey are particularly at risk of early pregnancy and higher fertility rates (Golbasi, 2021; Vural, 2021).

Concerning reproductive health and behaviour, refugee women experience more negative pregnancy and neonatal outcomes (Sayili, 2021) and also negative birth experiences during birth services in Turkey (Yaman Sözbir et al., 2021) along with low levels of antenatal care (Çöl et al., 2020). Although Syrian migrant women are aware of contraceptive methods, the rate of method use tend to be low and the rate of unmet need for family planning needs is 35 per cent (Çöl et al., 2020; Özşahin et al., 2021). About the fertility characteristics of refugee women who migrated to Turkey, the research found that it changed according to their ethnic background and was sustained in the country they migrated to (Coşkun, 2020) as mentioned earlier how in Syria before the conflict, family and reproductive health preferences was highly depended on the ethnicity and religious backgrounds.

Fertility and marriage preferences are generally studied through existing quantitative data to understand the overall dynamics. For stable populations, it is easier to measure and understand the roots of certain changes within general demographic theories. For example, the decreasing fertility rates in Syria before the conflict can be explained through the demographic transition. The overall fertility and marriage preferences of Syrians is however not simple to understand as it includes both contextual and personal dynamics that affected the population on different levels as the results from current literature shows.

This research aimed to get into more sociological and demographic aspects of these changes within this heterogeneous population that has arrived in Turkey in massive waves. It already shows that the Syrian population in Turkey is a selective migration but still includes all social classes and communities due to the very high amount of arrivals reaching 3.7 million (DGMM, 2021) and many others fleeing to the neighbouring countries. It means that the dynamics of fertility and marriage preferences would be better understood if observed through differences within this population.

This research was done as an additional contribution to quantitative research2 focusing on the impact of the biggest humanitarian cash transfer programme called ESSN3 on the fertility rates and fertility calendar of the applicants. The ESSN has around 1.5 million beneficiaries and the eligibility is decided by the demographic criteria, for instance having at least three children—dependency ratio being equal to or greater than 1.5—which was thought to affect the fertility behaviour of Syrians to become beneficiaries for the programme. While this research focused on the administrative data from the applicant list, additional focus group discussions were collected to support the statistical findings from the research. The research was financed by the World Food Programme to investigate the rumours that refugee households are having more children to become beneficiaries of the ESSN. The collection of focus group discussions with the refugee households in Turkey was a routine monthly monitoring exercise done by the World Food Programme (WFP) and the Turkish Red Crescent (TRC) who are the main implementing partners of the ESSN. While the questions were provided by the research team, the FGDs were collected by WFP and TRC teams and the research team was able to attend six focus groups as an observant in three different cities.

The main material of this study was the FGDs collected under the ESSN Fertility study mentioned above. Considering the richness of this qualitative data, the focus was to pay attention to the fertility and marriage preferences of Syrian refugees in Turkey in the context of forced migration. More precisely, the aim was to analyse these preferences in the light of the various social situations. FGDs also allowed us to analyze the data by distinguishing the refugees according to their gender, age group and place of residence. Moreover, FGD participants were also diversified in terms of social background and their migratory course (exposure to civil war violence, time of migration). This information led to enlightening these preferences that had not necessarily been underlined in the first place.

Similar research was done in Lebanon already on the perspectives of displaced Syrian women and service providers on fertility behaviour and available services (Kabakian-Khasholian et al., 2017). This research is the first qualitative research on the fertility and marriage preferences of Syrian refugees focusing on different age groups, and including both genders which accounts for the gendered approach while examining a sensitive subject as such. The main research questions are shown below:

• What happens to the matrimonial and reproductive norms in the context of forced migration?

• Do the FGD participants think that their fertility and marriage preferences have changed with forced migration?

• If that is so, how do they explain these changes?

• Do their preferences, representations and explanations vary according to individual situations?

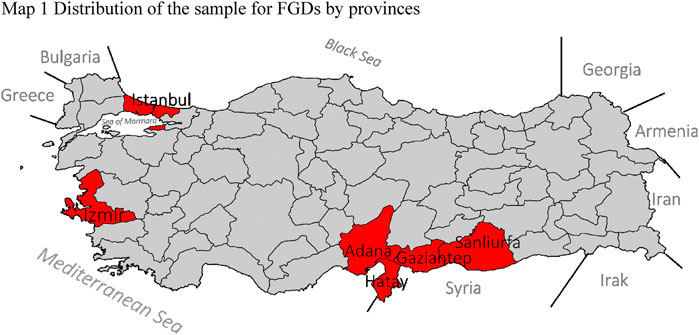

The sample consisted of a total of eleven FGDs from different locations that mainly revolved around the main refugee-hosting cities. That included main cities with much better job opportunities due to improved industries: Istanbul, Izmir and Ankara. The other cities chosen by the research team were mainly close to the Syrian border due to the high population density of Syrians. While Turkey counts 3.7 million Syrians among its inhabitants, the Table 1 shows where FGDs were collected which covered 61 per cent of all Syrians residing in Turkey4. We excluded one city (Ankara) from the analysis as the refugees who attended discussions in that city were mainly from Iraq. We also had age groups and gender groups distributed in a way that all groups were represented both in the bordering cities with Syria and also cities with improved industries in the western part of Turkey as Figure 1 shows.

FIGURE 1. Map 1 Distribution of the sample for FGDs by provinces. The map was produced by Celio-Sierra Paycha according to the FGD sample.

In focus groups in general, some arguments might be defined by specific participants and age can be an important factor. In some cases, older participants tend to be the most respected members of their community and their opinion could shape the overall discussion. For instance, if an older participant would oppose contraceptive use, younger members would often stay silent and not confront the opinion of the upheld members. To mitigate this, two age groups were made so that they would ideally represent two different generations in order to encourage full participation. During the design phase of the FGDs, the population samples were divided into two different age groups that are defined as below 30 and above 30.

Discussions on fertility and marriage preferences can also be shaped by the gendered approach. Indeed, in most cases, women tend to stay silent while talking about fertility, contraception and other intimate issues if there is another participant from the opposite gender. As a result, two distinct groups of male and female participants were set up for the discussions in order to give women a chance to freely express their preferences. It was decided that there would be around 10 to 14 participants for each group maximum and the overall discussion would take 3–4 h.

The survey design was planned carefully by the research team and consisted of three main sections5. The first section focused on the family events such as their arrival time and other relevant socio-demographic information. This section was useful to draw the participants’ profiles and understand the specific differences that affected their daily lives since their arrival in Turkey. The second section was about marriages. This part of the survey brought a broad perspective to the customs of marriages back home in Syria and their evolution since the exiles’ arrival in Turkey. It also enabled the making of a connection between past and present in order to get a bigger picture of marriage preferences. The last section was about fertility preferences. Questions on contraceptive usage were only asked in female FGD groups. For this part of the questionnaire, following the same method as the questions about marriages, the questions were about their perspectives before and after their arrival in Turkey.

We had a total of 82 Syrian refugees who participated in these discussions. While more than half of the participants were females, the number of male participants was only 29. The survey participation was on a voluntary basis and the participant list was organized by the Turkish Red Crescent (TRC) colleagues. Most participants were active visitors of TRC community centres6 that are present in most cities where the refugee population is present in Turkey. The community centres support the refugee populations on a variety of subjects such as protection issues, livelihood support and access to health services. The number of male participants was less compared to females as many of them had to work during the daytime. All refugees who attended this study were urban refugees as in the case of more than 99 per cent of the refugee population in Turkey as only 50,000 out of 3.7 million Syrians in Turkey are living in the refugee camps (DGMM, 2021).

The consents from the participants was obtained upon their acceptance to participate which was initially confirmed by phone or in-person through the network that exists in TRC community centres. At the beginning of the discussions, all participants signed a paper confirming their consent to participate. According to the FGD operational guidelines of WFP and TRC teams, WFP is mainly responsible to provide methodological support whereas the operational side is handled by TRC teams as the permissions to interview any refugee population in Turkey was given solely to TRC teams by the Government of Turkey. As our contract was signed with WFP, we provided the required technical support i.e., providing the FGD questionnaire and sampling and TRC teams were supporting in arranging participants and any other operational support. As discussed earlier, focus groups discussions were a routine monitoring activity for WFP and TRC within the ESSN programme all required approvals were documented by them as they are the owners of the data and all official permissions are obtained from them to publish this article.

Confidentiality and anonymization were ensured. Most focus group discussion reports did not include any individual responses but rather collective opinions from the discussions. For those where we were provided with a verbatim transcript, it was directly anonymized and participants were addressed as participant 1, participant two which did not include any personally identifiable information.

Concerning the referral protocols, as TRC community centres have a big role in providing a variety of services to the refugee population but mostly on protection and legal aid related issues, participants who required any further assistance were referred to the relevant services if they agree for it. Issues regarding the ESSN programme was handled directly by the social workers in the community centres. WFP and TRC teams had a system in place which was part of the ESSN programme on any protection issues which is entered into the system and handled carefully for each refugee individually or on a household level.

The focus group discussions were conducted by Field Monitoring Assistants of WFP, who are trained on survey data and focus group discussions collection specifically as FGDs were monthly monitoring activity. The same was valid for TRC teams as they also had a team of trained monitoring assistance that led the data collection activities for the ESSN. As a result, they have a completely independent position with regard to the management of the participants’ situation.

The data collection took place in July 2019. The focus groups were organized in different cities simultaneously. While some of the focus groups took place in the community centres directly, some others were hosted by one of the participants. In the setting, there was one moderator and one note-taker with some exceptions as having more than one note-taker in some cases. The discussions were led by the moderator in Arabic and later translated into English to be shared with the research team. We were able to attend six different focus groups as observant and we were provided with a simultaneous translator for the translations from Arabic to English during FGDs.

In most cases, we did not intervene as observant, we rarely added some extra questions to probe some of the interesting conversations. It should also be noted that the main author of the paper was the employee of the WFP Turkey Country office at the time of data collection who proposed this study in the first place. Yet, this did not have an impact on the neutrality of the study as the process was mostly managed by the TRC, and her extensive knowledge and experience in the field with the Syrian refugees had a positive impact to have a better interpretation of the results.

One of the challenges was that the discussions occurred in Arabic and were later translated into English by the facilitators. While some discussions were handed over with the full transcript, others were only summarized into short sentences. Moreover, as a research team, we could only personally attend the discussions in three provinces for security reasons by the time of data collection. As a result, we did not have the full experience of some discussions.

The main purpose of collecting the FGDs was to understand the impact of the cash transfer programme that uses demographic criteria on the fertility incentives of the beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries. Consequently, during the discussions, there were both beneficiary and non-beneficiary participants. Eventually, the beneficiary status did not appear to have a strong impact on the overall fertility and marriage preferences. This was thus not reflected in the overall sample.

In most FGDs, the questions were well taken and satisfyingly answered. None of the groups was shy to express their opinion about any of the subjects. Yet, as this is the nature of discussions, some of them were dominated by the first answers that would then cause homogeneous results, which did not necessarily reflect the actual opinion of each participant. For instance, if someone would say that their ideal number of children was 4, most other participants would just agree with them.

Unlike other qualitative methods such as the individual interview or observation, which were more familiar to some of the team members, it appeared that the FGDs were particularly adapted to this study. The collective interviews not only enabled us to accurately capture the matrimonial and reproductive norms that were converging among most of the participants but also to reveal the diversity of speeches in cases of divergences, like the example below. Two of them exchange their views about the ideal number of children:

“Interviewer: What do you think is the best or most appropriate number of children? There is no right or wrong, I would like to hear it from all of you.

Participant1: it is a crime to have more than two or three children, back in Syria it was unlimited.

Participant2: I think this is God’s will, no one can decide. Everything is related to God.” (Male FGD, Istanbul).

Unfortunately, all the FGDs have not been transcribed with the same precision and have not necessarily been supervised by a member of the research team. Some reports, lacking too much detail could not enable an accurate exploration of all the divergences, practices or contradictory viewpoints. It would have been more interesting to couple the FGDs with semi-directive interviews in order to analyse more deeply the construction of the matrimonial and reproductive norms on an individual scale.

The FGD reports led to an articulation of two main lines of analysis: one included the social characteristics of the participants such as age, gender, social background and the other one was on the migratory patterns such as time and motivation of departure, places and conditions of arrival in Turkey.

The social, generational and gender characteristics are interlinked dimensions that form the cornerstone of the reproductive and matrimonial preferences and projects.

The FGDs were mostly homogeneous from the focal point of social origins: in some of them, the participants belonged to the same social group whereas other groups presented more heterogeneous aspects. The social stratification of the Syrian society is made of privileged classes and working-class from rural and urban areas as was observed in the discussions’ statements. The participants have various perceptions and normative worlds according to their social backgrounds. In several discussions during FGDs, differences were observed with their levels of education, economic capital or living places before the migration.

The ideal agenda in terms of age for marriage and first pregnancy was also specific to each social group. The participants who had more economic and educational capital claimed that the ideal age to get married and have children depends on a successful academic background and having a steady job in the labour market. The social downgrade they have been suffering since their arrival in Turkey has pushed them to reconsider their agendas and wait until they have a stable income resource. Within the rural and working-class category, marriage and parenthood are more held as a form of security, particularly for women in the chaotic context of migration. That is why, as in the FGD made in Adana counting on the one hand women who had recently fled from Raqqa and on the other hand uneducated women coming from the countryside, many of them stated that marriage was for them the only way to earn physical and economical security. They also testify about widows who got remarried to men already married in this prospect supporting the idea of polygamy to protect those women who are widows in Syria.

The way the FGDs were composed enabled us to have the opinions of several generations from men and women in their twenties to ones in their early fifties. While most FGDs are only constituted of people from the same generation, some others had extra participants despite that the sample was constructed based on age groups. Unlike other contexts of post-demographic transition where fertility is very low regardless of the generation, in its demographic contexts, Syria has seen a particularly dynamic evolution of its fertility level throughout these last decades. In 1990, this fertility was above five children per woman. At the beginning of the Syrian civil war, it went down to three children per woman. Nowadays, it may be close to 2.8 children for Syrian women according to the estimations of the World Bank (2021). The increase of the age for marriage and pregnancy simultaneously matched with the decrease of fertility. The generational gaps in the demographic transition may be found in the representations of matrimonial and reproductive projects. The youngest generations seem to claim that it is important to acquire a certain maturity to enter adulthood (for marriage and pregnancy). Hence, the answer of one of the eldest female participants from Gaziantep concerning the ideal age for matrimonial and reproductive projects who stood out from the crowd by defending young motherhood.

“What is the ideal age to get married for women and men?

One of the elderly participants stated that girls should marry at the age of 15–16 and boys at 18 years old. Because of technology, boys and girls communicate easily with each other, which is against religion and culture, so to avoid this, they should marry early. According to one of them, the ideal age is 26 years old. The others stated that the ideal age is 20 years old for marriage.

[…]

Do you think your children will get married at the same age as you did? Why or why not?

Except for one elderly participant, all the others stated that their children would get married at different ages from their own. They will get married older. Until they became mature enough to understand and decide to marry by themselves, they will not marry.” (Female FGD, Gaziantep).

On the contrary, in Adana, where the participants were younger (25 on average), their answers underlined the necessity to postpone the age for first marriage after the end of their studies, according to their common ideal age for adulthood, which does not appear in older generations:

“What is the ideal age to get married for women and men?

Ideal age for women is 17, 20, 19, 20, 17, 18, 18 and for men it’s mostly 25 and above. They also said that women should be 18 or older so that they can decide what’s better for them. After the children graduate from school, they can get married.

Do you think your children will get married at the same age as you did? Why or why not?

All participants agreed that all children first need to graduate from school, then they can get married. They can get married earlier if they don’t want to study but it should be above 18.” (Female FGD, Adana).

Men and women, regardless of their ages or social situations do not share the same point of view about these questions. The difference between men and women’s answers was observed repeatedly in most FGDs. As far as they are concerned, women seem to be less conservative than men, or at least, more realistic about the social transformations at stake, as the distinct answers about contraceptive methods could prove. Some of the male participants, on the other hand, think that Islam forbids birth control because it goes against God’s will, whereas women claim that they are not against the usage of contraceptive methods.

While all women of all ages say explicitly that they are aware of the changes occurring among the Syrian society, in social norms in terms of marriage and fertility, men put this vision less into words. Women of all ages foresee those transformations at stake as a form of the social shift to its very roots whereas men consider this turmoil as a result of the situational events linked to their current exile in Turkey.

According to the focus groups, men not only feel less concerned about changes regardless of their ages, but they also express a sort of nostalgia from the past they mourn to have lost. In the male FGD from Istanbul below, two men think that the women’s participation in household income is only an adjustment to the economic poverty they are experiencing, however, their new presence in the public space is generally not perceived as positive.

“Interviewer: How about females?

Participant 1: Yes, they are also working now. But if there is one working member in the household, it would be enough. So, sometimes they are sending their daughters to find a decent job to support [them].

Participant 2: Not all women are working. Their circumstances are worse. Women were studying back in Syria. Now here, they all have to stay at home because it is not safe enough. Syria was safer for women … not now, but I mean before the war … ” (Male FGD, Istanbul).

On the opposite, women see these changes as unavoidable and tend to be more accepting of them. They describe the costs and benefits of these changes in terms of emancipation and modifications of gender relationships and partnerships, namely in the redistribution of the matrimonial charges and responsibilities between men and women, as discussed in Istanbul in the exchange below:

“Participant 7: In Syria it was different. The roles of men and women have changed. Women didn’t go out alone … We never went out without our husbands … The only neighbourhood I was familiar with was the neighbourhood I lived in … When we came to Turkey, alhamdulilah, thank God I started going out … I go out more than I did back home … I know this place better than I know my own country…

Interviewer: Does this change make you feel better or not?

Participant 7: A lot!

Interviewer: Do you like this change? Do you feel better because of it?

(Participants all talking at the same time, agreeing that the change is better).

Participant 7: My husband would say no, it’s forbidden, it’s forbidden, it’s forbidden…

Interviewer: But has it changed for everyone? Do you all feel like freer women? Can you go out more … and make more friends? I mean, do you actually feel this freedom?

Participant: The responsibility … There’s more responsibility…

Participant: The woman is just as responsible as the man…

(More than one participant talking at the same time indicating that they agree).

Interviewer: Of course, there’s more responsibility…

[…]

Participant 5: For Syrians, it’s very difficult here … We are half men and half women at the same time…

Participant: Yes, we are struggling…

Participant: We work outside the house and inside too.

Participant 5 [Syrian] women have become men here, too. For example, we buy the bread … we buy things … We buy everything … and if we find a job, of course we will also work…

Interviewer: Is it better or worse for you?

Participant: It’s more tiring…

Participant 5: It’s tiring but I mean…

Participant: We have touched freedom…

Participant 5: We have touched freedom…

Participant 3: The husband leaves very early for work … and comes back in the evening … How is he going to go out and buy you a piece of meat? Yes … So, now you have to go out and run errands…

Participant 11: But it’s good that we are now sharing this [responsibility] with our husbands … ”

Interviewer: Is it better now?

Participant: It’s good…

Participant 3: We buy our groceries every Wednesday … Every Friday we go out…

Participant 7: In Syria, we couldn’t ask our husbands how much was … For example 1 kg of aubergines … You couldn’t ask this … You were not allowed to know this … “Didn’t I buy you the aubergines? You can’t ask!”

(Female FGD, Istanbul).

These differences in perception about women’s emancipation have significant consequences on fertility and marriage norms, more precisely concerning the ideal age for pregnancy and marriage. In the quotations of the continuing interview below with women from Istanbul, they picked up on the question of their unprecedentedly acquired responsibilities and asserted that no woman should get married before getting mature enough to be able to handle her new responsibilities acquired with exile.

“Interviewer: 18?

Participant 7: It’s too much of a responsibility for [a girl] under 18…

[…]

Participant 7: I got married at 20 for example … Alhamdulilah at that age you can take up the responsibility of the household … Before that, you can’t…

Participant 13: My daughter also married at 20 … She’s immature … She and her husband … It’s as if they were both children … She’s always causing him problems … ” (Female FGD, Istanbul).

The Syrian population in Turkey is diversified as the whole population has suffered the civil war and had to flee from their home country, including men and women, people of all ages and social classes. This diversity that was carefully taken into account while collecting FGDs thus shows a heterogeneous set of opinions. The perceptions regarding the changes of matrimonial and reproductive practices and norms differed by each generation, gender and social background of the participants. More vulnerable households from Syria tend to think in favour of early marriage and parenthood since that can be seen as a form of protection, whereas more privileged households are more for a postponing of these events and waiting until they are settled back down to a more balanced socio-economic status. Men and the elderly are more likely to comply with the traditional norms of early marriage and have a higher number of children. They develop their arguments around material and economical justifications to explain the changes which they often disapprove of: “if we make fewer children, it’s because we can’t have as much as we did before, we just can’t afford it anymore.” On the contrary, the youngest generations and most of the women, or in other words, the two groups to whom the exile has paradoxically provided some benefits of emancipation and individual independence, are more in favour of a decrease of fertility, the postponing of marriage and pregnancy and consider those changes as sustainable.

The struggle of forced migration—in terms of temporality, modes of transportation and travel conditions but also in terms of places and conditions of arrival—have a direct impact on the perceptions and the ways of dealing with their life projects, and thus their family projects. Beyond the refugees’ pre-existing characteristics at the moment of migration (gender, age and social background), the conditions of migration and arrival also shape the way one can consider their matrimonial and reproductive projects. The second part of these results is dedicated to how marriage and fertility practices are influenced by the characteristics of the migratory journey. In other words, this second part focuses on the impact of the temporality of the migratory journey (period of departure, exposure to violence and perspectives of return) and its destination (mainly the province of arrival and residence in Turkey) on the matrimonial and reproductive projects.

Suffering violence is often a central issue as far as forced migration is concerned, not only because it tends to be the main reason for leaving the country, but also it is experienced at home and after in the host country. (Andro and Scadollero, 2019). The FGD analysis enabled us to point out two distinct types of migration paths for men and women. The first one is that they come from families who had to flee from the combat zones and thus who had suffered psychological and/or physical violence or secondly families who fled before they experienced these types of trauma. In the FGDs collected in the metropolises of Izmir or Istanbul, the participants had rarely been confronted to direct war violence whereas the testimonies reported more recurrent cases of violence during the FGDs collected in bordering cities with Syria. The context of repetitive and embedded violence, acting like a collective and individual blast wave affected the matrimonial and reproductive projects (Freedman, 2015).

Running away either from the political crisis or ISIS, from political repression or combat zones, in 2013, 2016 or after 2017 implies multiple possibilities of migratory trajectories and various levels of exposure to violence. Adana had the sad record of testimonies of violence whereas, in the other cities, those events were not necessarily mentioned. One of the male participants from Adana for example mentioned a torture centre near his children’s school, back in Syria. The association of being at school with the shrieks of pain traumatised his children to the point that they constantly refused to ever go back to school, even years after in Turkey although it is at peace.

Some of the women in Adana, who were from Raqqa, declared as the capital of ISIS, suffered from the violence that might have unsettled their standard matrimonial practices. ISIS had indeed taken the right to force marriages between women and terrorist soldiers. Women have come to consider polygamy as security against this type of danger. Couples already married proposed widows or single women to join the household in order to protect them from being matrimonial preys to ISIS. The wounds of the war have not healed even after they left their home country. Still, in Adana, the same women took stock of the numerous Malthusian xenophobic acts of obstetrical violence they have been enduring in Turkish maternities, pushing them to reconsider downwards the number of their children. Here is an example below:

“Interviewer: Where did you give birth to your children? Was it in the hospital? Did you get the healthcare you needed/ wanted during your pregnancy if you ever got pregnant in Turkey?

Participants: All women gave birth to their children in a hospital. However, doctors are not nice to Syrians. They say that Syrians make a lot of babies. Most women go to hospitals for monthly control. One woman said that she had a very bad doctor but as soon as she said that she was married to a Turkish man, he was very nice. After three children, doctors are very mean.” (Female FGD, Adana).

The violence endured throughout the migratory course has a strong impact on the perspectives of returning to the home country (Goldstein and Goldstein, 1981): the more violence the country is associated with, the less they wish to go back. While a majority of the people interrogated have lived in Turkey for several years, the prospects of return differ in the answers. The possibilities of a return to Syria or on the contrary of settling down in Turkey eventually define the matrimonial projects that the parents plan for their children. In the case of potentially mixed marriages for their children (more precisely between a Syrian and a Turkish), the answers were equally in favour and against. Unexpectedly, the probability of going back to Syria for some exiles was discussed twice (in Izmir and Sanliurfa) with the arguments below:

Mixed marriage can be considered in a particular context of long-term migration with the project of settling down in the host country. However, for the parents who wish to go back to Syria with their married children as soon as the conflict ends, exogamy is completely rejected as it could encourage those families to settle down in Turkey if they have a Turkish family.

According to these people, the prospect of a marriage with a Syrian person would not affect a possible return if it had to happen. The quotations of discussion from Sanliurfa and Izmir both develop this idea:

“Would you feel comfortable if your daughter/son got married to someone from another nationality?

Two families said yes but the others said no; because we want to go back to Syria and that person from another nationality wouldn’t come with us. This is a problem” (Sanliurfa FGD).

“Would you feel comfortable if your daughter/son got married to someone from another nationality?

[…]

Participant 11: Participant 8 is Turkmen, I guess that’s why her daughters are married to Turkish men but for us Arabs, it is not acceptable. If I ever have to go back to Syria, I can’t leave my daughters here.

[…]

Participant 2: You can’t leave your daughter behind when going back to Syria. That’s why it’s not acceptable for them to marry Turks.” (Female FGD, Izmir).

These examples show that participants can be driven to change their perceptions on mixed marriage depending on the experiences they had throughout their migratory path. The normative context of the residing place can nonetheless determine the perceptions of ideal fertility and marriage.

According to Greulich et al., 2016, the western Turkish provinces display lower fertility and an older age for marriage than the standards observed in the eastern and central Anatolian regions. Most of the western regions for instance are below the generational replacement level since the 1980s. In the South-East, mainly in the provinces with a high concentration of Kurdish population, the fertility rate is higher and the age for marriage is younger than in Central Anatolia that shows an intermediate position. Still, according to these authors, the geographical distinctions can be explained by educational differences concerning women than by religious or ethnic differences. To sum up, if fertility is higher in the South-East, it is mostly due to a lower proportion of educated women there.

Those various normative contexts depending on the place of residence in Turkey probably generate various perceptions of the standards and the overturn of the standards of fertility and marriage for the exiles. First of all, the Syrian practices can look less different than the natives living in the bordering cities where they are similar and vice versa within metropolitan cities such as Istanbul, Izmir and Ankara. Second, the exposure to western fertility and marriage standards for populations having traditional norms can affect their practices even more radically. The hypotheses can be verified thanks to the information collected during the discussions.

The FGDs were led in the cities bordering Syria like Hatay, Gaziantep and Sanliurfa as well as in two of the cities far from Syria like Istanbul and Izmir. It is interesting to compare the Syrian perceptions of standards and practices of fertility and marriage with their change of standards since their departure, in the light of the Turkish practices for each hosting city. Among the bordering cities where the FGDs were collected, Sanliurfa had the highest total fertility rate with 3.9 children per woman in 2019 for the Turkish population (TUIK, 2021). Fertility rates are in Gaziantep (TFR = 2.62) and Hatay (2.38), these are above the generational replacement level. In contrast, Istanbul and Izmir had the lowest TFR with respectively 1.6 and 1.49 children per woman according to the Turkish National Statistics Institute (TUIK, 2021). The same trend was observed for the average age for marriage. In Sanliurfa, women get married younger than in Istanbul or Izmir.

In line with these assumptions, Sanliurfa and Hatay showed that the ideal number of children is at its highest with more than five children whereas in Istanbul and Izmir it was mostly below four children. The information on this issue reported from Gaziantep is not detailed enough to enable a decent comparison with the other provinces. However, in the bordering cities where the fertility rate is high, the Syrians visualise a higher ideal number of children than their compatriots who live in western metropolitan cities like Istanbul or Izmir where the fertility rate is lower.

Regarding the perception of fertility-practice changes in the context of forced migration, all the FGDs confirm a decrease of ideal fertility since their arrival. Economic reasons often determine the decrease of the ideal number of children, the educational cost of each child being superior for a Syrian family exiled in Turkey compared to their former situation, whether the family lives in Istanbul or along the Syrian border. However, in FGDs reports from Istanbul and Izmir, some female participants describe their interactions with Turkish people as a decreasing factor of their ideal fertility. One of the female participants hence briefly related her experience at the maternity with the medical staff who disapproved of having one additional child:

“When we go to hospitals in Turkey while we’re pregnant, the reaction is always: Why are you pregnant again? I think they are right, it is better to stop after having one or two.” (Female FGD, Izmir).

The participant here directly links her opinion on the decrease in the ideal number of children to the disapproval from the medical staff of Izmir in which her ideal number of children is now slightly below the replacement level. When we compared this to a similar case from Adana, it is from three children upwards that Syrian women are more likely to be disapproved which is slightly higher compared to Izmir. In the other extract transcribed, it is the interactions between Syrian and Turkish children that explain the decrease of ideal fertility for the Syrian families.

“F […] Did it affect you in this way? As for you (addressing a participant), you did not want to [have children] right?

Participant: Yes, because life is difficult, and children are demanding … For example, they see other children and they say ‘Mama, look he has a bicycle.’” (FGD, Istanbul).

Here it is not only the economic resources that have diminished since their arrival in Turkey but also the children’s basic needs that have increased because of the gap between the major way of life in Izmir and Istanbul. In this particular case, the Syrian child seems to be asking his mother the same sort of toys (here, a bicycle) as the Turkish children, which implies to adjust to the low fertility standards, characterised by a more important economic investment within a limited progeny by Gary Becker (1960). The interactions between the children in Istanbul and the ones between the Syrian woman and the hospital of Izmir show two examples to decrease fertility in a context where the gap of fertility between exiles and locals is significant. The type of interactions partly explains why the ideal number of children is lower within Syrian families exiled in Turkish western metropoles than within those exiled in the bordering cities.

Depending on the modalities of the migratory journey, FGD participants can be led to adjust their matrimonial norms to the new context in a pragmatic way. That is why some women confessed that polygamy could be a solution in the context of war. As for others, a mixed marriage with the local population can facilitate their integration into the host country. On the opposite, rejecting the idea of a marriage between Syrian and Turkish to avoid the risk of seeing their children settling down to ensure a potential return to the home country. The representations of matrimonial and reproductive projects considered as ideal are not self-evidently built at the convenience of individual practical adjustments. The standards applied in the new place of residence can to a certain extent sustainably sprout in the exiles’ minds. The examples above prove that the dissemination of the host’s standards towards the migrating populations can occur through micro-interactions.

This article aimed to understand the norms and representations of practices and the changes of practices related to the matrimonial and reproductive behaviours of the Syrian refugee population in Turkey. It seemed relevant to analyse these aspects by distinguishing the opinions according to the individuals’ characteristics and their migratory journey: social groups, genders, generations, temporalities of migration and the normative contexts of their hosting city.

The overall results of this study show similar observations among different groups among Syrians. Most quotations rarely reveal unheard or different opinions and show similar tendencies on the ideal number of children or the age for marriage or first pregnancy. Having fewer children, getting married later (particularly for women) are the most recurrent remarks. Most of the participants seem to agree on the fact that these customs are evolving, regardless of their generational, gender, residential or social situations. Besides, during the discussions, these changes were organised by a dual opposition between what had occurred “Back in Syria” and what they lived “Now in Turkey”.

Their points of view about the reasons for these changes nevertheless differ according to the characteristics of the individuals. Everyone seems to be aware that the changes have been operating but they do not explain them with the same arguments. Some individuals highlight short-term adjustments to explain the changes. Particularly men, the populations who have violently suffered the outcomes of the civil war, the most rural and underprivileged populations, the populations exiled in the cities close to the Syrian borders and the elderly tend to think of the decrease of fertility as a pragmatic and rational adjustment to the economic downgrade they now have to face. The downgrade has indeed significantly impacted the individuals who often used to own their housings and be qualified and educated in their home country whereas they now have become tenants and perform underqualified jobs if they work at all, stuck in a context of an economic crisis in Turkey. The burdens of economic difficulties, the mental load of raising children and the sacrifice of paying a dowry for the children’s marriage are added a total absence of hope for a brighter future for their descendants.

On the contrary, other participants consider the changes in terms of matrimonial and reproductive behaviours as more sustainable, that they refer to a change of standards. It involves younger generations, most of the women, the populations who left Syria at the beginning of the conflict or settled in the metropole cities where the matrimonial and reproductive norms are the most different from those in Syria by the time they left the country. In a certain way, the civil war and its outcome leading to a forced migration can be held as a throttle to one of the aspects of the first demographic transition (Kirk 1996), namely the decrease of fertility. In some quotations, several growing aspects of the second demographic transition, characterised by an increase of couple breakdowns and divorces are observed (Lesthaeghe, 2014). The reported speeches from the female FGD extracts in Istanbul hint repeatedly at women’s empowerment. Others refer to the possibility of a divorce in case of a complicated marriage in an insecure time.

Of course, these two types of considerations cannot be opposed to one another. The new norms are often accepted since they are adapted (from a pragmatic and rational point of view) to a certain situation. It applies to all Syrian refugees as their situation, sometimes seen as a short-term upheaval looks stabilising throughout the years. That is why the women, who have acquired new responsibilities by economic necessity, play a main part in their empowerment, including in terms of reproductive and contraceptive choices.

The original contributions presented in the study are partly included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The ethical review and approval was obtained according to the FGD operational guidelines of WFP and TRC teams who collected the data. Written informed consent for participation was obtained prior to each FGD by WFP and TRC teams in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

This research was done using the qualitative data that was collected for another research on the impact of demographic criteria and humanitarian assistance on fertility decisions of the Syrian refugees. The main author IB is a PhD candidate currently working on the Syrian refugees in Turkey and focusing on their fertility and marriage preferences. This research was led by her within her doctoral studies. However, AA and CS-P widely contributed to this research as the field trip for this research was done together in 2019 in Turkey organized by IB within her employment at the World Food Programme by the time of the data collection.

This study was made it possible through the support of the United Nations World Food Programme during its work with the Government of Turkey and Türk Kızılayı on assisting over 1.7m Syrian and other refugees with generous funding from European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations under its ESSN grant to WFP.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We would like to express our appreciation to all monitoring assistants of World Food Programme Turkey country office and the Turkish Red Crescent for their efforts in the data collection.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fhumd.2021.778385/full#supplementary-material

1Most Syrians in Turkey are under temporary protection, however, throughout the report, they will be referred as refugees

2Bozdag, I., Sierra-Paycha, C., and Andro, A (2021). Humanitarian Assistance and Fertility Decisions: To what extent Emergency Social Safety Net (ESSN) targeting criteria had influenced the fertility rates and fertility calendar of Syrian refugees in Turkey. p. 1–24

3Emergency Social Safety Net: What is ESSN?

4The population numbers are taken from DGMM (Directorate General of Migration Management) on 28 August 2021

5The final questionnaire can be found in the appendix

6Fact sheet: TRC Community Centres

Abdulrahim, S., DeJong, J., Mourtada, R., and Zurayk, H. (2017). Estimates of Early Marriage Among Syrian Refugees in Lebanon in 2016 Compared to Syria Pre-2011. Eur. J. Public Health 27 (3), 322–323. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckx189.049

Agadjanian, V. (2018). Interrelationships of Forced Migration, Fertility and Reproductive Health. Demogr. Refugee Forced Migration, 113–124. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-67147-5_6

Al Akash, R., and Chalmiers, M. A. (2021). Early Marriage Among Syrian Refugees in Jordan: Exploring Contested Meanings through Ethnography. Sex. Reprod. Health Matters 29 (1), 1–16. doi:10.1080/26410397.2021.2004637

Amiri, M., El-Mowafi, I. M., Chahien, T., Yousef, H., and Kobeissi, L. H. (2020). An Overview of the Sexual and Reproductive Health Status and Service Delivery Among Syrian Refugees in Jordan, Nine Years since the Crisis: a Systematic Literature Review. Reprod. Health 17 (66), 166. doi:10.1186/s12978-020-01005-7

Amiri, M., El-Mowafi, I. M., Chahien, T., Yousef, H., and Kobeissi, L. H. (20202020). An Overview of the Sexual and Reproductive Health Status and Service Delivery Among Syrian Refugees in Jordan, Nine Years since the Crisis: a Systematic Literature Review. Reprod. Health 17, 166. doi:10.1186/s12978-020-01005-7

Andro, A., and Scadollero, C. (2019). Parcours migratoire, violences déclarées, et santé perçue des femmes migrantes hébergées en hôtel en Île-de-France. Enquête Dsafhir (2017-18). Bull. Epidémiol Hebd, 334–341. Available at: http://beh.santepubliquefrance.fr/beh/2019/17-18/2019_17-18_3.html.

Avogo, W., and Agadjanian, V. (2008). Childbearing in Crisis: War, Migration and Fertility in Angola. J. Biosoc. Sci. 40 (5), 725–742. doi:10.1017/S0021932007002702

Bartels, S. A., Michael, S., and Bunting, A. (2021). Child Marriage Among Syrian Refugees in Lebanon: At the Gendered Intersection of Poverty, Immigration, and Safety. J. Immigrant Refugee Stud. 19 (4), 472–487. doi:10.1080/15562948.202010.1080/15562948.2020.1839619

Bartels, S., Michael, S., and Roupetz, S. e. (2018). Making Sense of Child, Early and Forced Marriage Among Syrian Refugee Girls: A Mixed Methods Study in Lebanon. London: BMJ Global Health.

Becker, G. (1960). “An Economic Analysis of Fertility,” in Demographic and Economic Change in Developed Countries (Columbia University Press).

Bozdag, I., Sierra-Paycha, C., and Andro, A. (2021). Humanitarian Assistance and Fertility Decisions: To what Extent Emergency Social Safety Net (ESSN) Targeting Criteria Had Influenced the Fertility Rates and Fertility Calendar of Syrian Refugees in Turkey. Ankara, Turkey: World Food Programme.

Çağatay, P., Keskin, F., and Ergöçmen, B. (2020). “Fertility Behavior of Syrian Women in Turkey: The Crosscut of Intention and Regulation,” in Syrian Refugees in Turkey. Editor A. Cavlin (Oxfordshire: Taylor & Francis), 86–102.

Cevirme, A., Hamlaci, Y., and Ozdemir, K. (2015). Women on the Other Side of War and Poverty: Its Effect on the Health of Reproduction. Ijwhr 3 (3), 126–131. doi:10.15296/ijwhr.2015.27

Cherri, Z., Gil Cuesta, J., Rodriguez-Llanes, J., and Guha-Sapir, D. (2017). Early Marriage and Barriers to Contraception Among Syrian Refugee Women in Lebanon: A Qualitative Study. Ijerph 14 (8), 836. doi:10.3390/ijerph14080836

Çöl, M., Bilgili Aykut, N., Usturalı Mut, A. N., Koçak, C., Uzun, S. U., Akın, A., et al. (2020). Sexual and Reproductive Health of Syrian Refugee Women in Turkey: a Scoping Review within the Framework of the MISP Objectives. Reprod. Health 17 (99). doi:10.1186/s12978-020-00948-1

DGMM (2021). Distribution of Syrians under Temporary Protection by Year:Temporary Protection Statistics. Available at: https://en.goc.gov.tr/temporary-protection27.

DGMM (2014). Temporary Protection in Turkey. Ankara, Turkey: Directorate General of Migration Management. From https://en.goc.gov.tr/temporary-protection-in-turkey.

Fargues, P. (2011). International Migration and the Demographic Transition: A Two-Way Interaction. Int. Migration Rev. 45 (3), 588–614. doi:10.1111/j.1747-7379.2011.00859.x

Fargues, P. (2000). Protracted National Conflict and Fertility Change: Palestinians and Israelis in the Twentieth century. Popul. Dev. Rev. 26 (3), 441–482. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2000.00441.x

Freedman, J. (2015). Gendering the International Asylum and Refugee Debate. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Golbasi, C., Vural, T., Bayraktar, B., Golbasi, H., and Sahingoz Yildirim, A. G. (2021). Maternal and Neonatal Outcomes of Syrian Adolescent Refugees and Local Adolescent Turkish Citizens: A Comparative Study at a Tertiary Care Maternity Hospital in Turkey. Gynecol. Obstet. Reprod. Med., 1–9. doi:10.21613/gorm.2021.1186

Goldstein, S., and Goldstein, A. (1981). The Impact of Migration on Fertility: An 'own Children' Analysis for Thailand. Popul. Stud. 35 (2), 265–284. doi:10.1080/00324728.1981.10404967

Goldstein, S. (1973). Interrelations between Migration and Fertility in Thailand. Demography 10 (2), 225–241. doi:10.2307/2060815

Gonçalves, M., and Matos, M. (2016). Prevalence of Violence against Immigrant Women: a Systematic Review of the Literature. J. Fam. Viol 31 (697).

Greulich, A., Dasre, A., and Inan, C. (2016). Two or Three Children? Turkish Fertility at a Crossroads. Popul. Dev. Rev. 42 (3), 537–559. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2016.00148.x

Hervitz, H. M. (1985). Selectivity, Adaptation, or Disruption? A Comparison of Alternative Hypotheses on the Effects of Migration on Fertility: The Case of Brazil. Int. Migration Rev. 19 (2), 293–317. doi:10.1177/019791838501900205

Hill, K. (2004). War, Humanitarian Crises, Population Displacement, and Fertility: A Review of Evidence. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Holck, S. E., and Cates, W. (1982). Fertility and Population Dynamics in Two Kampuchean Refugee Camps. Stud. Fam. Plann. 13 (4), 118–124. doi:10.2307/1965707

Jensen, E., and Ahlburg, D. (2004). Why Does Migration Decrease Fertility? Evidence from the Philippines. Popul. Stud. 58 (2), 219–231. doi:10.1080/0032472042000213686

Kabakian-Khasholian, T., Mourtada, R., Bashour, H., Kak, F. E., and Zurayk, H. (2017). Perspectives of Displaced Syrian Women and Service Providers on Fertility Behaviour and Available Services in West Bekaa, Lebanon. Reprod. Health Matters 25, 75–86. doi:10.1080/09688080.2017.1378532

Kirk, D. (1996). Demographic Transition Theory. Popul. Stud. 50 (3), 361–387. doi:10.1080/0032472031000149536

Korri, R., Hess, S., Froeschl, G., and Ivanova, O. (2021). Sexual and Reproductive Health of Syrian Refugee Adolescent Girls: a Qualitative Study Using Focus Group Discussions in an Urban Setting in Lebanon. Reprod. Health 18 (130), 130. doi:10.1186/s12978-021-01178-9

Kulu, H. (2005). Migration and Fertility: Competing Hypotheses Re-examined. Eur. J. Popul. 21, 51–87. doi:10.1007/s10680-005-3581-8

Kurt, G., Acar, İ. H., Ilkkursun, Z., Yurtbakan, T., Acar, B., Uygun, E., et al. (2021). Traumatic Experiences, Acculturation, and Psychological Distress Among Syrian Refugees in Turkey: The Mediating Role of Coping Strategies. Int. J. Intercultural Relations 81, 214–225. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2021.02.001

Lee, B. S., and Pol, L. G. (1993). The Influence of Rural-Urban Migration on Migrants' Fertility in Korea, Mexico and Cameroon. Popul. Res. Pol. Rev 12, 3–26. doi:10.1007/bf01074506

Lesthaeghe, R. (2014). The Second Demographic Transition: A Concise Overview of its Development: Table 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 111, 18112–18115. doi:10.1073/pnas.1420441111

Lindstrom, D. P., and Saucedo, S. G. (2002). The Short- and Long-Term Effects of U.S. Migration Experience on Mexican Women's Fertility. Social Forces 80 (4), 1341–1368. doi:10.1353/sof.2002.0030

M Coşkun, A., Özerdoğan, N., Karakaya, E., and Yakıt, E. (2020). Fertility Characteristics and Related Factors Impacting on Syrian Refugee Women Living in Istanbul. Afr. H. Sci. 20 (2), 682–689. doi:10.4314/ahs.v20i2.19

Munajed, D. A., and Ekren, E. (2020). Exploring the Impact of Multidimensional Refugee Vulnerability on Distancing as a Protective Measure against COVID-19: The Case of Syrian Refugees in Lebanon and Turkey. J. Migration Health 1-2 (2), 100023. doi:10.1016/j.jmh.2020.100023

Othman, H., and Saadat, M. (2009). Prevalence of Consanguineous Marriages in Syria. J. Biosoc. Sci. 41 (5), 685–692. doi:10.1017/S0021932009003411

Öztürk, A. B., Albayrak, H., Karataş, K., and Aslan, H. (2021). Dynamics of Child Marriages Among Syrian and Afghan Refugees in Turkey. Atatürk Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi 25 (1), 251–269. Available at: https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/ataunisosbil/issue/60912/738035.

Özşahin, A., Nilüfer, E., and Tamer, E. (2021). Contraceptive Use and Fertility Behaviour Among Syrian Migrant Women. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 26 (3), 209–213. doi:10.1080/13625187.2020.1867842

Rabo, A. (2008). 'Doing Family': Two Cases in Contemporary Syria. Hawwa 6 (2), 129–153. doi:10.1163/156920808X347232

Randall, S. (2004). Fertility of Malian Tamasheq Repatriated Refugees: The Impact of Forced Migration. Columbia UniversityNational Academies Press (US.

Randall, S. (2005). The Demographic Consequences of Conflict, Exile and Repatriation: A Case Study of Malian Tuareg. Eur. J. Popul. 21 (1), 291–320. doi:10.1007/s10680-005-6857-0

Rumbaut, R. G., and Weeks, J. R. (1986). Fertility and Adaptation: Indochinese Refugees in the United States. Int. Migration Rev. 20, 428–466. doi:10.1177/019791838602000216

Sayili, U., Ozgur, C., Bulut Gazanfer, O., and Solmaz, A. (2021). Comparison of Clinical Characteristics and Pregnancy and Neonatal Outcomes between Turkish Citizens and Syrian Refugees with High-Risk Pregnancies. J. Immigrant Minor. Health. doi:10.1007/s10903-021-01288-3

Sieverding, M., Berri, N., and Abdulrahim, S. (2019). “Marriage and Fertility Patterns Among Jordanians and Syrian Refugees in Jordan,” in The Jordanian Labour Market : Between Fragility and Resilience. Editors C. Krafft, and R. Assaad (OxfordOxford, 259–288. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198846079.003.0010

Sieverding, M., Krafft, C., Berri, N., and Keo, C. (2020). Persistence and Change in Marriage Practices Among Syrian Refugees in Jordan. Stud. Fam. Plann. 51 (3), 225–249. doi:10.1111/sifp.12134

Toulemon, L. (2004). La fécondité des immigrées : nouvelles données, nouvelle approche. Populations et Sociétés 400, 1–4.

Tsourapas, G. (2019). The Syrian Refugee Crisis and Foreign Policy Decision-Making in Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey. J. Glob. Security Stud. 4 (4), 464–481. doi:10.1093/jogss/ogz016

TUIK (2021). Birth Statistics. Available at: https://data.tuik.gov.tr/https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Kategori/GetKategori?p=nufus-ve-demografi-109&dil=2.

UNICEF (2021). Child Marriage in Humanitarian Settings: Spotlight on the Situation in Arab Region. UNICEF. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/mena/sites/unicef.org.mena/files/2018-08/CM%20in%20humanitarian%20settings%20MENA.pdf.

Vural, T., Gölbaşı, C., Bayraktar, B., Gölbaşı, H., and Yıldırım, A. G. Ş. (2021). Are Syrian Refugees at High Risk for Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes? A Comparison Study in a Tertiary center in Turkey. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 47 (4), 1353–1361. doi:10.1111/jog.14673

World Bank (2021). Fertility Rates , Total (Births Per Woman) - Syrian Arab Republic. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.TFRT.IN?locations=SY.

World Bank (2021). Fertility Rates , Total (Births Per Woman) - Syrian Arab Republic. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.TFRT.IN?locations=SY.

World Food Programme (2020). Comprehensive Vulnerability Monitoring Exercise. Ankara: WFP. FromAvailable at: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/CVME5_03072020.pdf.

Keywords: refugees, syrians, fertility, marriage, Turkey, focus group discussion (FGD), forced migration, early marriages

Citation: Bozdag I, Sierra-Paycha C and Andro A (2022) Temporary Adjustment or Normative Change? Fertility and Marriage Preferences of Syrian Refugees in Turkey in the Context of Forced Migration. Front. Hum. Dyn 3:778385. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2021.778385

Received: 16 September 2021; Accepted: 13 December 2021;

Published: 18 January 2022.

Edited by:

Jane Freedman, Université Paris 8, FranceReviewed by:

Gillian Wylie, Trinity College Dublin, IrelandCopyright © 2022 Bozdag, Sierra-Paycha and Andro. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ilgi Bozdag, aWxnaWJvemRhZ0BnbWFpbC5jb20=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.