- 1Independent Expert, Els Leye Consultancy, Ghent, Belgium

- 2Independent Expert, ICF S.A., London, United Kingdom

One of the major achievements in tackling violence against women (VAW) is the adoption of the Council of Europe’s Istanbul Convention on VAW and Domestic Violence. The Istanbul Convention (IC) is a legally binding instrument tackling violence from a gender perspective, with a comprehensive set of measures. Although 21 European Union Member States (MS) and Turkey have ratified the Istanbul Convention and the European Union itself signed it, opposition towards gender equality has also risen. This paper reviews a study tendered by the European Parliament (the EP study), which aimed to understand the implementation of the Convention, its added value and arguments against its ratification. The EP Study grouped the 27 European Union MS and Turkey into those that have and have not ratified and implemented the IC. The EP study was based on four strands of data collection: 1) a literature review focusing on the impact of and arguments against ratification; 2) a legal mapping of the legislation to compare the criminal codes and support services of each country with relevant articles of the Convention; 3) national data collection to identify challenges in the implementation of the Convention and good practices; 4) a stakeholder on-line consultation. The study was conducted in 2020. The EP study found that ratification of the Convention triggered amendments to existing legislation and/or the adoption of new legal measures, but that legislative changes are less extensive in countries that have not ratified the Convention. Most European Union MS have adopted gender-neutral approaches to laws and policies, thus failing to acknowledge the gendered nature of violence against women and domestic violence. Seven of the European Union countries (BG, HR, LT, LV, MT, RO, TU) refer to physical, psychological, economic and sexual violence in their definitions of domestic violence, while nine countries (AT, BE, CZ, DK, EE, FI, FR, IE, LU) do not define domestic violence. Remaining challenges in the implementation of the Istanbul Convention include a lack of sustainable national action plans, and insufficient funding for specialist support services. Resistance to the Convention is evident even in countries that have ratified it, in response to proposed legislation on same-sex marriage, adoption or sexuality education in schools. Non-ratifying countries and countries with high resistance to the Convention often display victim-blaming public attitudes to intimate partner violence, stronger gender stereotypes and a stronger resistance to same-sex marriage/rights. The paper concludes by suggesting recommendations. The cut off date for data collection was 16 September 2020 and therefore legal and policy developments after that date were not included in this paper. This includes Poland and Turkey announcing their withdrawal from the IC in respectively July 2020 and March 2021. However, given the focus of this paper is on understanding the reasons behind resistance against the IC and on the differences between countries that ratified and those that did not, this paper contributes to a better understanding of how progress has been made following the IC, and points to the added value of the IC.

Introduction

Violence against women (VAW) can take different forms and has been widely acknowledged as an expression of inequality on the basis of gender. Despite decades of measures to tackle VAW, it remains widespread worldwide, including in Europe (FRA - Fundamental Rights Agency, 2014a). Since the age of 15, one in three women in the European Union (EU) has experienced physical and/or sexual violence, one in two experienced sexual harassment, one in 20 women has been raped and one in five experienced stalking. Moreover, 95% of victims that are trafficked for sexual exploitation in the EU are women. Nearly one in four women (22%) has experienced physical and/or sexual violence at the hands of a partner since the age of 15, and nearly half (43%) have experienced psychological partner violence. Among women in top-level management or professional occupational categories, 74–75% report having experienced sexual harassment in their lifetime (FRA – Fundamental Rights Agency, 2014b). In Turkey, 40% of women are exposed to physical and sexual violence, but only 10% of women exposed to violence seek help (Yüksel Kaptanoğlu et al., 2015). A 2018 Turkish study showed that 41% of the 1481 female respondents (married at least once and over 18 years) had experienced domestic violence (DV) and “the majority (89%) had been subjected to violence by their spouse” (Basar and Demirci, 2018).

Consequences of violence include fatal and non-fatal physical and mental health effects and can persist long after the violence ends (WHO and PAHO 2012). The composite measure for severity of gender-based violence in the EU showed that the health consequences of VAW and multiple victimization by any perpetrator was almost 50% (49.6%), and that only 14.3% reported violence experienced in the past 12 months (EIGE – European Institute for Gender Equality, 2017). Because violence against women is rooted in gender inequality, it is often also called gender-based violence. The EU Gender Equality Index showed a very slow progress on gender equality in the EU Member States (MS) in 2017, with an overall increase of only four points in the last 10 years, to 66.2 out of 100 (EP – European Parliament, 2017a). Moreover, the Covid-19 pandemic has slowed down progress made in tackling violence against women, whilst opposition towards gender equality has risen in a number of countries in Europe.

The EU provides a response to VAW through EU legislation and policies that tackle VAW, DV and gender inequality, as well as through a number of programs and initiatives. Although the EU treaties do not refer to VAW or gender based violence directly, a number of texts exist that refer to equality between women and men, such as the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), and the Charter of Fundamental Rights, making gender equality a guiding principle for the EU. Secondary law also does not include a specific instrument to address VAW and DV, but has a number of instruments that are relevant to the topic, such as the legislation on trafficking in human beings (CoE - Council of Europe, 2004a; EP and CoE – European Parliament and Council of Europe, 2011a), on protecting victims of crime (EP and CoE – European Parliament and Council of Europe, 2011b; EP and CoE – European Parliament and Council of Europe, 2012) or protection against (sexual) harassment committed in the workplace (CoE – Council of Europe, 2004b; EP and CoE – European Parliament and Council of Europe, 2006, 2010). Some of the relevant policy measures that tackle gender inequality and VAW, include the European Commission (EC)’s EU Gender Equality Strategy 2020-2025 (EC – European Commission, 2020a), the Resolutions of the European Parliament dealing with VAW (EP – European Parliament, 2017b, 2018, 2019, 2020) and the European Commission’s EU Guidelines on VAW and girls of 2008 (EC – European Commission, 2008). The EU also contributes to fighting VAW and DV through actions such as funding programs (e.g. the Daphne Program/Rights, Equality and Citizenship Program), awareness raising (e.g. NON.NO.NEIN campaign), research (e.g. the Fundamental Rights Agency’s (FRA) survey on VAW) and coordinated actions (e.g. Spotlight Initiative).

One of the major steps forward in dealing with VAW has been the adoption of the Council of Europe (CoE) Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence, better known as the Istanbul Convention (IC), in 2011. It is the first international treaty, and thus the first legally binding instrument, that deals specifically with violence from a gender perspective. It recognizes “the structural nature of violence against women” and “that domestic violence affects women disproportionately”, while recognizing that men may also be victims of such violence (Meurens et al., 2020). The Istanbul Convention tackles violence in a comprehensive way, through a focus on integrated policies, prevention, protection and prosecution. The Convention further develops international human rights law on the issue of VAW and brings distinct features, such as its gendered understanding of violence, the explicit reflection of due diligence, preventive measures addressing the root causes of violence, and an effective multi-agency approach to protect high-risk victims through risk assessment/management and an independent monitoring mechanism (Meurens et al., 2020). Types of violence that are detailed in the IC are: VAW; DV; physical, psychological, sexual and economic violence; stalking; female genital mutilation/cutting; forced marriage; forced abortion; forced sterilization and sexual harassment.

Since its adoption in 2011, 34 Members of the CoE have ratified the IC, including 21 EU MS and Turkey (as of February 16 2021). The EU itself signed the Istanbul Convention in 2017 but has not concluded it yet. When it does, the Istanbul Convention will form part of EU law insofar as EU competence is concerned (CJEU - Court of Justice of the European Union, 1974). Like every other signatory, the EU will be legally bound to implement and apply the Convention through legislation and policies, and to report to the Council of Europe Group of Experts on Action against Violence against Women and Domestic Violence (GREVIO). The IC will have the effect of strengthening the EU’s commitment to combating VAW and DV across the EU. It will require the EU to reinforce its legal framework in the area of criminal law in relation to the forms of violence within the scope of the Convention. Currently, the EU legal framework is broad and insufficiently specific to VAW and DV (De Vido 2017). One key avenue for the EU to implement the Convention is through the adoption of a directive on VAW and adding relevant forms of VAW among the list of crimes. The adoption of such a directive would provide the EU with a strong instrument to implement the Convention. EU implementation of the IC would require a toolbox of measures combining binding instruments with policy measures, initiatives and programs. Lastly, the EU will be required to allocate adequate resources for the implementation of the IC once it concludes the Convention (Meurens et al., 2020).

Given the importance of the IC in providing a legal basis for tackling VAW and DV in Europe, the EP Study has put the Istanbul Convention at the center to analyze progress made in Europe and Turkey, towards the eradication of violence against women. The paper analyses the added value of the IC and also sheds light on the (growing) resistance in some EU countries to ratification of the Convention, by analyzing the arguments against ratification and the impact of withdrawal from the Convention.

The cut off date for data collection was 16 September 2020 and therefore legal and policy developments after that date were not included in this paper. This includes Poland and Turkey announcing their withdrawal from the IC in respectively July 2020 and March 2021. However, given the focus of this paper is on understanding the reasons behind resistance against the IC and on the differences between countries that ratified and those that did not, this paper contributes to a better understanding of how progress has been made following the IC, and points to the added value of the IC.

Methodology

This paper is based on a study1 that was commissioned by the European Parliament’s Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs at the request of the FEMM Committee, and presents its main findings. The study aimed to understand the implementation of the Convention, its added value, and arguments against the ratification of the Convention. The study grouped the 27 EU MS2 and Turkey into those that have ratified and implemented the Istanbul Convention and those that have not. Turkey was included to offer a comparator of the impact of the ratification of the Convention by a non-EU country. The study was based on four strands of data collection. First, a literature review of peer-reviewed and grey literature was conducted. Secondly, a legal mapping of the legislation was performed to compare the criminal codes and support services of each country against relevant articles of the Convention. The mapping has been carried out based on publicly available information. The main sources of information used were the State Baseline Reports to GREVIO, the GREVIO 1st evaluation reports, NGOs’ contribution to GREVIO as well as findings from the literature review. Where needed, the national legislation was reviewed, in particular the Criminal Code. Thirdly, national data collection was carried out, to identify challenges and good practices in the implementation of the Convention. This was done by 19 national researchers (see Acknowledgements), who covered all EU MS and Turkey. The national researchers conducted the desk research between 29 July 2020 and 16 September 2020 to complete a fiche for their country. Finally, a stakeholder consultation was carried out to collect information from support services for victims of VAW, particularly in relation to the impact of ratification of the Convention (where applicable). The country experts identified key stakeholders through desk research. The consultation was open from 5 August to 15 September 2020 and received 103 responses. The study as a whole was conducted between April and November 2020 (Meurens et al., 2020).

Implementation of and Resistance to the Istanbul Convention Across the EU and Turkey

Status of the Ratifications and Reservations to the Istanbul Convention

The EP study found that as of September 2020, 21 EU MS and Turkey had ratified the Convention. These MS were as follows: Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Cyprus, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, Spain, and Sweden. All of these countries lodged their ratification instruments before 1 July 2020. However, on 31 July 2020 (during the period of the study), Poland began the formal process to withdraw from the Convention. Furthermore, in March 2021, Turkey also announced its withdrawal from the Convention (Gumrukcu and Spicer 2021). The EP study categorized the 22 countries mentioned above as having ratified the Convention. The remaining six countries - Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Hungary, Lithuania, Latvia and Slovakia - are categorized as countries that have not ratified the Convention.

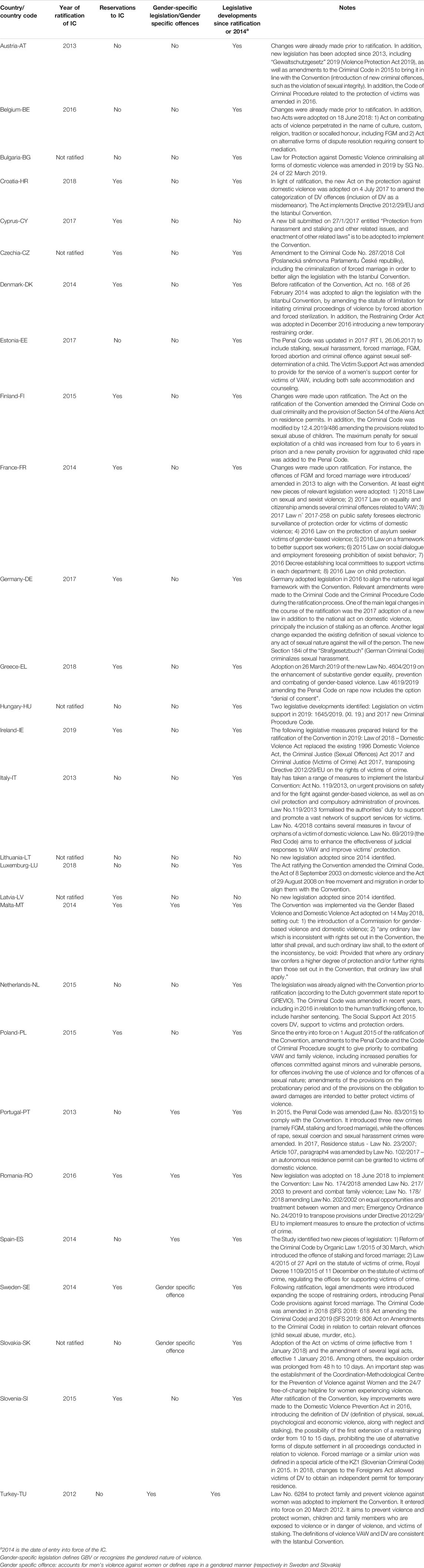

Upon ratification, MS are bound to review and, where necessary, adjust their national legal and policy frameworks to ensure the implementation of the Convention’s requirements. This is usually achieved by amending national criminal legislation to introduce new offences. For example, countries may criminalize forced marriage and psychological violence or introduce stricter sanctions for perpetrators. Article 78 of the Convention establishes that MS can reserve the right not to apply the following provisions of the Convention: Articles 30(2); Article 44(1), (3) and (4); Article 55(1); Article 58; and Article 59. Fifteen MS have signed or ratified the convention with reservations (CY, CZ, DE, DK, EL, FI, FR, HR, IE, LV, MT, PL, RO, SI, SE)3. An overview of reservations is provided in Table 1.

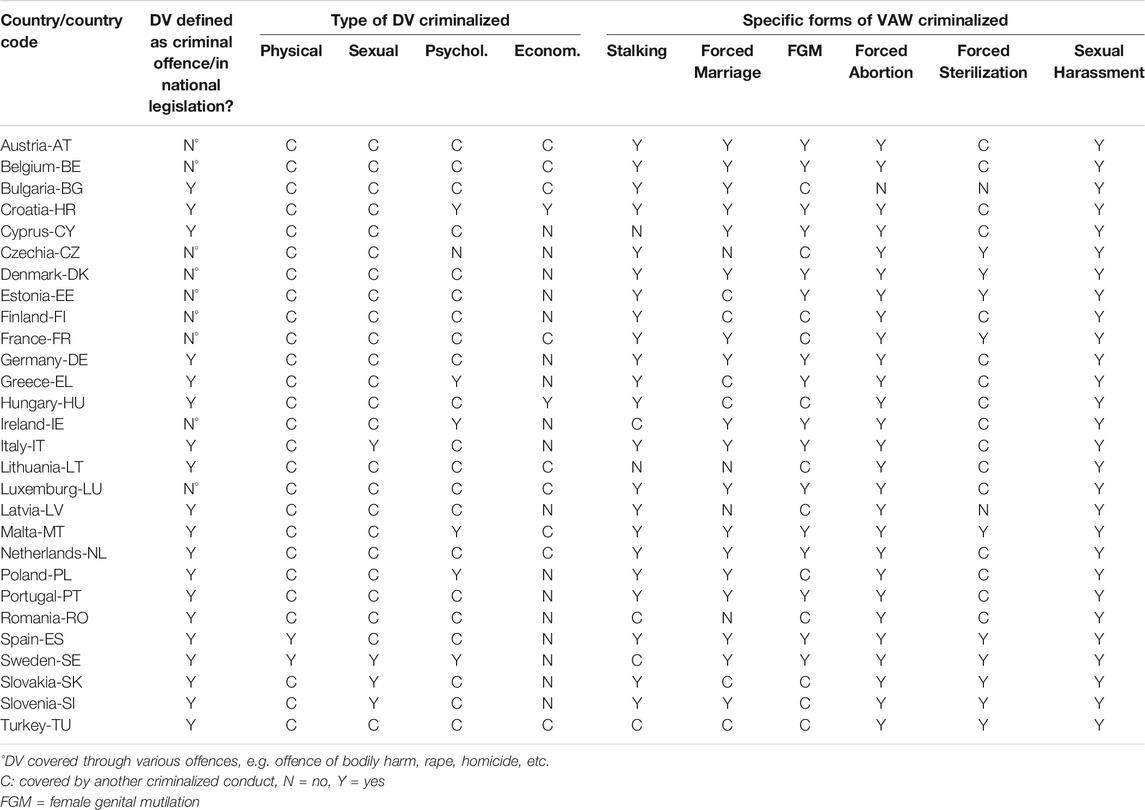

TABLE 1. Overview ratifications, reservations and legislative developments [adapted from Meurens et al. (2020)].

In addition to reservations, MS may also issue declarations to the Treaty. A declaration is often used to provide interpretation or explanation as to how the Treaty is applied to the national context. One such example of this is Croatia, which has made a Declaration relating to the concept of “gender ideology”4. This Declaration specified “the provisions of the Convention do not include an obligation to introduce gender ideology into the Croatian legal and educational system, nor the obligation to modify the constitutional definition of marriage” (CoE - Council of Europe, 2020a). There is evidence that this declaration was aimed at appeasing resistance to the Convention, mostly led by religious and conservative individuals and groups (Alcalde and Šarić 2018). According to the Government, the declaration was justified “due to the sensitivity of one part of the public”. The EP study noted “the Declaration has three main messages that the Convention does not imply assuming any obligation to introduce anything that would be contrary to Croatia’s legal order, that it does not introduce gender ideology in the country’s legal system and that it does not change the definition of marriage.” (Government of the Republic of Croatia 2018).

Legislative Developments Following the Ratification

The EP Study identified the impact of the Istanbul Convention by assessing to what extent ratification had triggered changes in the national legal framework, comparing countries that have ratified the Convention with those that have not. The study also looked at legislative changes in countries that have not yet ratified the Convention since 2014, the year of the entry into force of the Convention.

Of the EU-27 and Turkey, only three countries did not have any legislative developments since ratification or the date of entering into force of the IC in 2014 (CY, LT, LV). Of these, Lithuania and Latvia have not ratified the Convention. Cyprus is the only country that ratified the Convention but had no legislative developments relevant to the implementation of the IC. This is most likely linked to Cyprus having ratified the Convention recently (in 2017) and as of March 2021, is still in the process of revising its legislation. Most countries amended their legislation either prior to ratification or at the same time as the ratification. Seven countries (EL, ES, MT, PT, RO, SE, SI) made legislative changes to implement the Convention after its ratification. An overview of legislative developments is provided in Table 1.

The EP study not only revealed that ratification of the Istanbul Convention triggered amendments to existing legislation or/and the adoption of new legal measures, but also that such legislative changes are more extensive in ratifying countries. Some examples of the importance of the legislative changes triggered by the ratification to the Convention are presented below.

In Malta, existing legislation on gender-based violence was overhauled after the Convention was given full legal effect in 2018. The EP study found that “following extensive research and public consultation, Act XIII of 2018 (the Gender-Based Violence and Domestic Violence Act) was introduced to strengthen the legal framework on VAW. The Act gives full effect to the provisions of the Istanbul Convention as it voids existing legislation that is inconsistent with the rights set out in the Convention, unless the existing law provides a higher degree of protection to victims” (Meurens et al., 2020).

In Sweden, following ratification of the Convention, a review of Swedish legal practices identified the need for changes in several areas. Through ratification of the Convention, restraining order provisions were expanded to perpetrators who share a permanent resident with the victim. In addition, provisions against forced marriage were introduced in the Penal Code (Government of Sweden 2017).

The EP study also found that “Slovenia introduced the Domestic Violence Prevention Act in 2008, which focused on the prevention of violence and protection of victims. After ratification of the Convention, several key improvements to this act were included, introducing harassment and sexual harassment as crimes to the Protection against Discrimination Act (2016) and amendments to the Foreigners Act in order to grant victims of domestic violence an autonomous residence permit irrespective of the duration of the marriage or the relationship, among others” (Meurens et al., 2020).

In Turkey, prior to ratification of the Convention, VAW was handled under the 4320 Numbered Law on Protection of Family. Ratification of the Convention prompted the adoption of the 6284 Law which is far more progressive than its predecessor, as described by the EP study “its first provision clearly states that its purpose is to protect four groups of people; women, children, family members and victims of stalking, who are subjected to violence or at risk of being subjected to violence (Article 1(1)). In this context, women are protected within the scope of law solely because they are women, i.e. outside the realm of family violence or DV, and under any circumstance. In addition, the 6284 Law provides a new comprehensive array of prevention and protection orders” (Meurens et al., 2020).

The EP study found that “for the countries that have not ratified the Convention, the Convention had still influenced legislative and policy developments. For example, in Czech Republic, the government reacted to the need to better align the legislative framework to the requirements of the international community in the area of VAW and DV (i.e. the Istanbul Convention) by submitting the Amendment to the Criminal Code No. 40/2009 Coll. The law was published on 13 December 2018 under No. 287/2018 Coll. Nevertheless, some key gaps remain in the Czech legal framework, such as the lack of offence of forced marriage” (Meurens et al., 2020).

New Forms of Violence Adopted as Criminal Offences Under National Laws

An important contribution of the IC is the establishment of criminal offences for various forms of violence, and recognition of the gendered dimension of violence. The IC also differentiates between VAW and DV, and as such, does not limit VAW to domestic violence. Acknowledging that violence is not gender-neutral is crucial if it is to be tackled appropriately (Meurens et al., 2020). The starting point that women are disproportionately affected by violence enables policy responses to be directed to meet the actual needs of victims. Although the Istanbul Convention defines DV in a gender-neutral manner in order to cover both women and men victims and perpetrators, it also stresses that DV is distinctly gendered. As stated by the EP study, “a gendered approach to legislation can take the form of gender-specific offences, such as an offence specifically on VAW, or it can take the form of a specific aggravating circumstance, whereby the gender dimension of the crime brings in a higher penalty. Similarly as for the definition of DV, the Istanbul Convention drafted most of the substantive criminal offences in a gender-neutral manner, with the exception of female genital mutilation (FGM), forced abortion and forced sterilization, which are formulated gender-sensitively, highlighting that they primarily concern women and more specifically their sexual and reproductive integrity” (Meurens et al., 2020).

Most EU MS have adopted gender-neutral legal texts (An overview of countries and their gender-neutral legal texts is provided in Table 1) and policies, which poses a challenge to tackling VAW and DV in some countries. GREVIO’s first general report criticized the gender-neutral approach of national legal provisions and policy documents on DV. According to GREVIO, the gender-neutral approach “fails to address the specific experiences of women that differ significantly from those of men thus hindering their effective protection” (CoE - Council of Europe, 2020b). Such gender neutrality poses a fourfold issue: ignoring unequal power dynamics between women and men on which domestic violence is based; avoiding the establishment of responsibility for abuse and control; presenting a barrier to ensuring criminal accountability; and not accounting for the many forms of VAW outside of dependency relationships. A gender-neutral approach also impacts service provision, such as the lack of provision of women’s shelters that was noted in France for example (CoE - Council of Europe, 2019).

The EP Study identified very few gender-specific offences, these were found only in Sweden and Slovakia. In Sweden, there is a specific criminal offence for VAW perpetrated by men. Under its offence of violation of the person’s integrity, if committed by a man against a woman to whom he is or has been married/cohabiting, he is guilty of gross violation of a woman’s integrity (Section 4a of the Criminal Code). In Slovakia, the criminal offence of rape is formulated in a gendered manner. Section 199(1) states that “Any person who, by using violence or the threat of imminent violence, forces a woman to have sexual intercourse with him, or takes advantage of a woman’s helplessness for such act, shall be liable to a term of imprisonment of 5–10 years”.

Five countries (ES, MT, PT, RO, TU) have adopted gender-specific legislation, which defines gender-based violence or recognizes the gendered nature of violence.

For example, in Romania, Law No. 178/2018 introduced the concept of gender-based violence as violence directed against a woman or a man motivated by gender. Under the law, “gender-based violence against women or violence against women represents any form of violence that affects women disproportionately. Gender-based violence includes, but is not limited to, domestic violence, sexual violence, genital mutilation of women, forced marriage, forced abortion and forced sterilization, sexual harassment, trafficking in human beings and forced prostitution”. In Spain, Organic Law 1/2004 of 28 December, on integrated protection measures against gender violence aims “to combat the violence exercised against women by their present or former spouses or by men with whom they maintain or have maintained analogous affective relations, with or without cohabitation, as an expression of discrimination, the situation of inequality and the power relations prevailing between the sexes”. It establishes integrated protection measures to prevent, punish and eradicate violence and ensure assistance to its victims: women and children. “The gender violence to which this Act refers encompasses all acts of physical and psychological violence, including offences against sexual liberty, threats, coercion and the arbitrary deprivation of liberty” (Meurens et al., 2020).

The EP Study also looked at the legal framework on domestic violence in the EU-27 and Turkey (An overview of criminal laws related to DV is provided in Table 2). The Istanbul Convention defines domestic violence as “all acts of physical, sexual, psychological or economic violence that occur within the family or domestic unit or between former or current spouses or partners, whether or not the perpetrator shares or has shared the same residence with the victim” (Article 3(b)). As noted in the EP study, a “key component of the definition is the recognition of the four types of violence as expressions of DV. In addition, such violence should not be limited to when the victim and perpetrator are living together or are in an intimate relationship, as violence can continue after the relationship has ended” (Meurens et al., 2020).

As stated in the EP study, “DV is not usually a criminal offence in and of itself but, rather, tends to represent an umbrella of criminal conduct within a family unit or in the context of intimate relationships. DV is defined in 19 of the countries (BG, CY, DE, EL, ES, HR, HU, IT, LT, LV, MT, NL, PL, PT, RO, SE, SI, SK, TU) as either a criminal offence or within the national legislation on DV, which usually provides the mechanisms for protection orders and victims’ rights. In some cases, the legal definition does not explicitly refer to the four types of violence. Only seven countries (BG, HR, LT, LV, MT, RO, TU) refer to the four forms of violence (physical, sexual, psychological or economic) in their definition of DV. In nine countries (AT, BE, CZ, DK, EE, FI, FR, IE, LU), DV is not defined at national level. However, the various forms of violence are covered fully or in part by various criminal offences. This means that the violence may be criminalized, but there is a lack of clarity on which violence falls under DV for the purpose of protection or barring orders and victims’ rights. As a result, victims could find it challenging to seek out protection, unless police or prosecution practices or guidelines impose protection or barring orders for all four forms of violence. The absence of, and unclear or limited definitions do not necessarily mean a lack of coverage of the four forms of violence as criminal offences. In fact, most forms of violence are covered by several criminal offences rather than by an all-encompassing clearly defined criminal offence” (Meurens et al., 2020).

Both physical and sexual violence are reflected in the criminal legislation of all countries in the study (EU-27 and Turkey). Those forms of violence mostly fall under several types of criminal conduct. Psychological violence is present across the national legislation under various types of offences, such as threats, coercion, harassment, insult, blackmail, stalking, among others. Czech Republic, which has not ratified the Convention, does not have any identified forms of psychological violence in its legislation. The EP study stated that, “in six MS (EL, HR, IE, MT, PL, SE), psychological violence in the context of DV is explicitly reflected in a criminal offence. Economic violence is the form of violence that is least reflected in national legislation. Eleven countries reflect economic violence in their legislation. In 9 countries (AT, BE, BG, FR, LU, LT, MT, NL, TU) economic violence falls under certain offences which represent conduct falling within the category of economic violence if it occurs in the context of DV (e.g. theft, concealing assets, not paying alimony, etc.), while in HR and HU it is clearly defined in their legislation. The Istanbul Convention does not require the criminalization of economic violence, instead linking it to psychological violence and the wider concept of DV. The lack of a specific economic violence offence in the Convention accommodates its absence from national legislation” (Meurens et al., 2020).

The EP study did not identify a decisive pattern when comparing countries that have ratified the Convention with those that have not. In Bulgaria, Hungary and Lithuania, all four forms of violence are reflected in the legislation. In Latvia and Slovakia, economic violence is omitted but the legislation covers the three remaining forms of violence, like many of the countries that ratified the IC. Lastly, Czech legislation appears to only cover physical and sexual violence.

The Istanbul Convention also requires State Parties to criminalize stalking, forced marriage, female genital mutilation, forced abortion, forced sterilization and sexual harassment (An overview of the criminalization of specific forms of violence is provided in Table 2). These specific types of conduct were included for their seriousness and as they are widespread in Europe and beyond. As noted in the EP study, “the Convention does not oblige State Parties to reproduce the specific provisions of the Convention or to mirror the same conduct. States should, however, ensure that types of conduct are sufficiently reflected in the criminal offences. Therefore, countries, which criminalize a particular conduct under other (various) offences rather than a specific explicit criminal offence, may still be in line with the Istanbul Convention” (Meurens et al., 2020).

Stalking is criminalized in the national legislation of 22 (AT, BE, BG, CZ, DE, DK, EE, EL, ES, FI, FR, HR, HU, IT, LU, LV, MT, NL, PL, PT, SI, SK) out of the 28 countries in the EP study. Ireland, Romania, Sweden and Turkey criminalize stalking under other criminal offences, such as threat, other forms of harassment and blackmail. As described in the EP study, “of the six countries that have not ratified the Convention, only Lithuania has no offence akin to stalking. Cyprus has no offence criminalizing stalking or similar conduct, but a draft law has been prepared to introduce a new offence of stalking: “Protection from harassment and stalking and other related issues, and enactment of other related laws” (Cyprus Women’s Lobby 2018). The ratification has led other countries to introduce the offence of stalking in their legal framework. Estonia updated its Criminal Code in 2017 (the year of ratification) to include harassing pursuit (stalking) under Article 157(3). Spain, in light of its ratification of the Convention, reformed the Criminal Code by Organic Law 1/2015 of 30 March, which introduced the offence of stalking and forced marriage. After ratification of the Convention, Slovenia adopted key improvements to the Domestic Violence Prevention Act in 2016 to introduce the definition of stalking (among others)” (Meurens et al., 2020).

Seventeen of the 28 countries (AT, BE, BG, CY, DE, DK, ES, FR, HR, IE, IT, LU, MT, NL, PT, SE, SI) examined by the EP study have a criminal offence specific to forced marriage. Of the non-ratifying countries, Czech Republic, Latvia and Lithuania do not criminalize forced marriage, while in Hungary this falls under the offence of coercion and in Slovakia, it falls under the offence of human trafficking. Estonia, Greece, Finland and Turkey limit the criminalization of forced marriage to the context of human trafficking (for sexual exploitation for example). Poland and Romania are the only countries that have ratified the Convention but where there is no criminal offence linked to forced marriage. In Poland, forced marriage can be criminalized under coercion to certain conduct (Article 191 § 1 Criminal Code). The EP study noted: “arguably, forced marriage would also be criminalized in Romania under a similar provision. However, the lack of clear legal scope and clarity in the legislation - such as the absence of a definition and of the elements of the crimes – have been identified as hindering prosecution (Psaila et al., 2016). Ratification of the Istanbul Convention prompted some MS to establish a criminal offence specific to forced marriage. This is the case for France (Article 222-14-4 of the Criminal Code, in accordance with Article 37 of the Convention) and Portugal (Law No. 83/2015). Preparatory acts for forced marriage are also considered crimes and can be punished separately. In Sweden, ratification of IC led to a review of the Swedish legal framework, which identified some gaps and triggered the adoption of provisions against forced marriage in the Penal Code (Government of Sweden 2017)” (Meurens et al., 2020).

Female genital mutilation (FGM) is criminalized through explicit references in the legislation of 16 countries (AT, BE, CY, DE, DK, EE, EL, ES, HR, IE, IT, LU, MT, NL, PT, SE). In the remaining 12 countries (BG, CZ, FI, FR, HU, LT, LV, PL, RO, SI, SK, TU), it falls under acts such as bodily harm, health impairment, coercion and loss of an organ. The EP study noted that “ratification of the Istanbul Convention has led some MS to establish FGM as an offence or to better define it under their national legislation. For instance, Greece introduced a new specific reference to FGM in its Penal Code in 2018 (Law 4531/2018) in response to its ratification of the Istanbul Convention. Article 315B of the Penal Code (Law 4619/2019) criminalizes individuals who persuade a woman to undergo FGM. In Luxembourg, the Law of 20 July 2018 implementing the Istanbul Convention (Law of 20 July 2018 approving the Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence against Women and Domestic Violence) introduced Article 409bis in the Penal Code, with a more detailed provision on FGM. In Austria, a recent amendment to the Criminal Code came into force in January 2020, introducing explicit reference to FGM under § 85 of the Austrian Criminal Code (bodily harm with severe and sustainable adverse effects). Romania does not have an explicit criminal offence for FGM as of yet. However, it is in the process of adopting new legislation to introduce such an offence. As a result of the work of the working group on the implementation of the Istanbul Convention, a draft law is being prepared to amend the Criminal Code. The draft Law will introduce new offences, including FGM, forced abortion and forced sterilization (Government of Romania 2020). None of the six countries that have not ratified the Convention have explicit criminal provisions on FGM, but can be criminalized under offences such as bodily harm or health impairment” (Meurens et al., 2020).

Bulgaria is the only country for which the study did not identify an explicit provision on forced abortion. Forced abortion is a human rights violation, in particular where this is conducted on persons with disabilities, which remains a practice in certain MS (CERMI Women’s Foundation and the European Disability Forum, 2017). The vulnerability of women and girls with disabilities stems both from their capacity to consent and from practices that do not give these women and girls a voice in their reproductive rights.

The EP study identified specific forced sterilization criminal offences in only 10 countries (CZ, DK, EE, ES, FR, MT, SE, SI, SK, TU). Forced sterilization is criminalized under other broader offences, such as bodily harm, assault and coercion in sixteen countries (AT, BE, CY, DE, EL, FI, HR, HU, IE, IT, LU, LT, NL, PL, PT, RO). No provision potentially criminalizing forced sterilization has been identified in Bulgaria and Latvia. As noted by the EP study, “it is likely that such conduct would fall under the bodily harm offence. In some of the MS, sterilization is a requirement to access gender legal recognition. In five MS (CZ, CY, FI, RO, SK), this is an explicit legal requirement, while in Latvia and Lithuania, a court can impose this in the absence of a procedure laid down in national law (European Commission 2020b). The Istanbul Convention does not govern legal gender recognition per se. However, such a legal requirement is akin to forced sterilization. Article 39 of the Istanbul Convention would apply to any forced sterilization of women. Since the Convention should apply regardless of gender identity, the question is whether it would apply to both women and men seeking to have their gender legally recognized. Aside from Slovakia, no non-ratifying Member State has an explicit criminal offence related to sterilization. In addition, three of those countries (Lithuania, Latvia, Slovakia) may require sterilization in cases of the legal gender recognition procedure” (Meurens et al., 2020).

The EP study found that all MS and Turkey criminalize sexual harassment to some degree but in most cases this falls under various offences or is limited to the workplace. As noted by the EP study, “all MS have transposed Directive 2006/54/EC, which prohibits sexual harassment in the workplace. In line with the Directive, sexual harassment in the workplace is considered a form of discrimination for which penalties must be established. The definition of sexual harassment under Article 40 of the Istanbul Convention almost mirrors the definition established by Directive 2006/54/EC Article 2(d), according to which sexual harassment is “any form of unwanted verbal, non-verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature occurs, with the purpose or effect of violating the dignity of a person, in particular when creating an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment”. Outside of the workplace, sexual harassment can be prosecuted under the offence of stalking, harassment, indecent assault, indecency, sexual intimidation or similar provisions. The fact that there is no comprehensive offence means that all the manifestations of sexual harassment are not criminalized comprehensively. GREVIO points to the issue of scattered protection in its review of the implementation of the Convention by Italy, which does not have a criminal provision dedicated to sexual harassment. Rather, sexual harassment falls under a number of civil and criminal provisions, such as the offence of sexual violence (Articles 609-bis Criminal Code), which does not apply to physical sexual acts other than genitalia or erogenous zone, or the offence of ill treatment (Article 572 Criminal Code), which is limited to family relations. Law No. 198/2006 on equal opportunities defines sexual harassment using the same definition as the Convention but is limited to sexual harassment in the workplace. The GREVIO experts noted that while sexual harassment fell under various provisions, “none of which, however, encompasses the entire spectrum of unwanted behavior of a sexual nature targeted by [Article 40 of the Convention]” (CoE - Council of Europe, 2020c). Eleven MS and Turkey (AT, DE, EE, FI, FR, HR, LT, MT, PT, RO, SK) have more comprehensive offences criminalizing sexual harassment. In Finland for example, sexual harassment is defined by chapter 20, section 5(a), of the Criminal Code as “a person who, by touching, commits a sexual act towards another person that is conducive to violating the right of this person to sexual self-determination”. The study did not find any patterns for this offence between countries that have ratified and those that have not” (Meurens et al., 2020).

Policy Responses to the Ratification of the Istanbul Convention

The Convention requires the adoption of “effective, comprehensive and coordinated policies” (Article 7) to prevent and combat all forms of violence. Such coordinated and holistic policies should be the results of the involvement of all relevant national and regional organizations, authorities and institutions to draw up relevant policies such as a National Action Plan (NAP) or strategy tackling the various forms of violence.

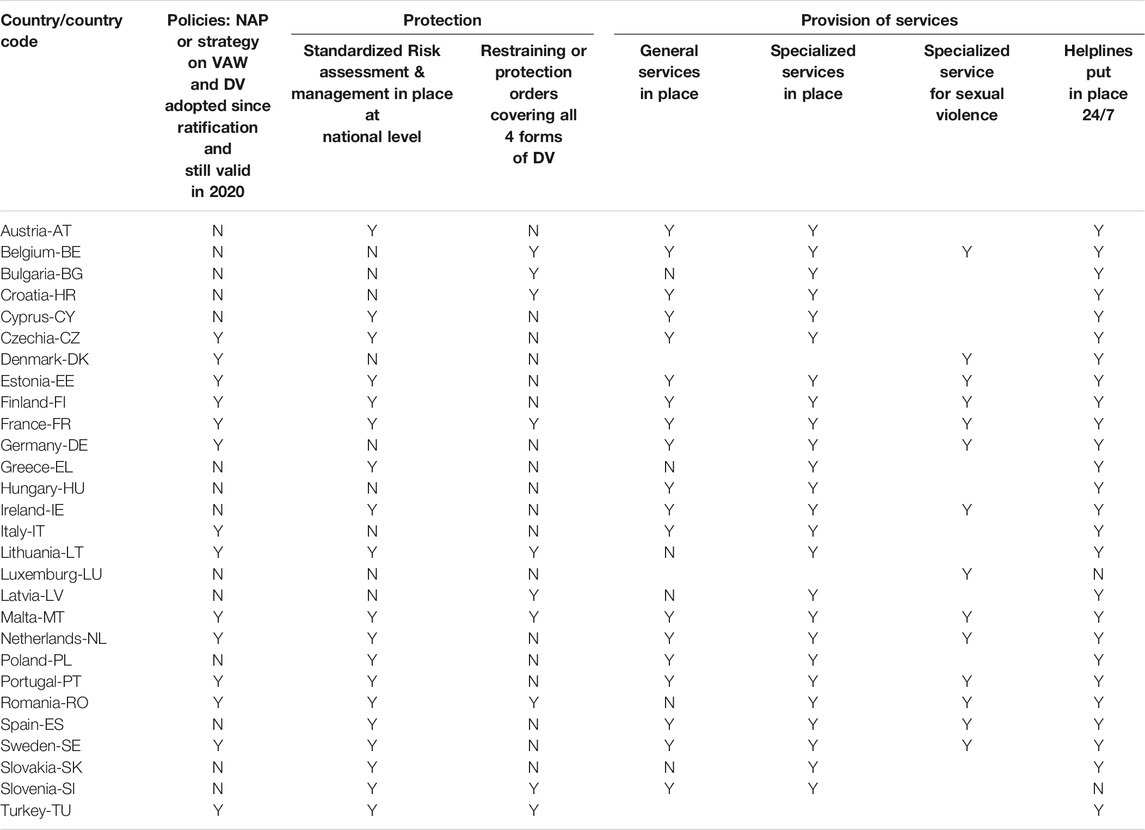

Our research showed that 14 countries (CZ, DE, DK, EE, FI, FR, IT, LT, MT, NL, PT, RO, SE, TU) have adopted an NAP or strategy on gender-based violence and DV, which were still applicable in 2020, and BG and LU have a NAP on gender equality that partly covers VAW. Of the non-ratifying countries, only CZ and LT have an NAP in place. Only the NAP of DE covers all forms of violence; most countries either focus on specific forms of violence or cover violence against women and domestic violence in general, without a focus on any specific forms of violence.

Almost half of the online consultation respondents (46%) confirmed an increase in coordinated, comprehensive and integrated policies on VAW and DV since the ratification of the IC. Examples of such changes include an increase in collaboration between agencies and increased funding (Meurens et al., 2020). However, 35% of the respondents did not see any changes in relation to more coordinated, comprehensive and integrated policies since ratification. An overview of integrated policies is provided in Table 3.

Protection of Victims of Violence and Their Children

The protection, support and assistance of victims from further violence are a core pillar of the Convention. To achieve this, the Convention establishes a range of obligations on setting up general and specialized support services to meet the needs of victims, risk assessment and safety plans for law enforcement and judicial authorities to manage identified risk for the victim (chapter 4 of IC).

EU legislation has played a crucial role in strengthening victims’ support and protection in EU Member States. The Victims’ Rights Directive (Directive 2012/29/EU) sets rights for victims of crime and minimum standards on victims’ support and protection. The Istanbul Convention, which dates prior to the Directive, sets more stringent requirements in some respects: while the Directive guarantees rights for victims, it does not establish support services requirements. For instance, both the Istanbul Convention and the Victims’ Rights Directive mention the need for general and specialized support services, whilst the Convention makes it a requirement to set up both and specifies the type of support services needed: helplines, shelters and rape crisis or sexual violence referral centers. Similarly, the IC goes more into detail than the Victims’ Rights Directive as for the types of protection measures to be implemented, such as risk assessment and management, emergency barring orders, restraining or protection orders.

When it comes to risk assessment and management, the Convention requires the setting up of standardized procedures to ensure that “an assessment of the lethality risk, the seriousness of the situation and the risk of repeated violence is carried out by all relevant authorities. Risk assessment and management obligations contributes to guarantee the implementation of the due diligence obligation (Article 5) for States to prevent acts of violence. Accordingly, “concern for the victim’s safety must lie at the heart of any intervention in cases of all forms of violence” (CoE - Council of Europe, 2011). The assessment and management of risk requires a coordinated response, taking into account the victim’s specific situation, the seriousness and frequency of the violence, perpetrator’s access to firearms, and so on. The EP Study found that 19 countries (AT, CY, CZ, EE, EL, ES, FI, FR, IE, LT, MT, NL, PL, PT, RO, SE, SI, SK, TU) have regulated and/or standardized risk assessment and management procedures. The remaining nine countries (BE, BG, DE, DK, HR, HU, IT, LU, LV) may have some risk assessment/management practices but those are not systematically applied or are limited.

Under the Istanbul Convention, restraining or protection orders should be available for all forms of violence covered by the Convention. The study found that only 10 countries (BE, BG, FR, HR, LT, LV, MT, RO, SI, TU) cover the four forms of domestic violence (sexual, physical, psychological, economic) in the scope of the protection order. This is in part due to the fact that not all four forms of domestic violence are explicitly criminalized in the national legislation. The Istanbul Convention has prompted legal developments in relation to protection orders in some countries, such as Croatia, the Netherlands, Slovenia and Turkey, which improved their framework on protection orders following ratification of the Convention.

Influence of IC on Support Services for Victims

The EP Study also established the influence of the IC on the availability of four types of support services for victims of violence: general support services, specialized support services, helplines and rape crisis or sexual violence referral centers. According to Ivankovic et al., 19 MS (AT, BE, CY, CZ, DE, EE, ES, FI, FR, HR, HU, IE, IT, MT, NL, PL, PT, SE, SI) offer both general and specialized support services, but six MS (BG, EL, LT, LV, RO, SK), four of which have not ratified the Convention, offer no general victim support services (Ivanković et al., 2019). The study identified few changes in the provision with only three countries (Cyprus, France and Sweden) having setting up or made change to general victim support services. The reason for this being that most countries already offered general victim support services prior to ratification.

Specialized support services ensure the provision of assistance tailored to the needs of specific groups of victims (e.g. migrants, women), victims of specific forms of violence (e.g. sexual violence) or the type of support (e.g. medical, psychological, legal). The EP Study identified the provision of new specialized support services in 10 countries (BE, DE, FI, FR, LV, NL, PL, PT, RO, TU) since ratification and a trend of establishing more tailored services for VAW and DV victims. This is confirmed by the online consultation, where the majority of respondents (55%, n = 84 stakeholders from countries that ratified IC) noted that they have seen changes to the availability and accessibility of specialized victim support services in their country. The respondents (n = 46 stakeholders that ratified IC) provided additional information on the types of changes seen in the provision of specialized support services. The most frequently reported change is an increase in the provision of shelters for victims (19% of respondents), as well as increased public services for victims (16%), changes in legislation or laws adopted (14%), increased awareness in general public and additional funding (both 12%) and police support improved (10%). 17% of the respondents also identified remaining gaps.

Specialized services for victims of sexual violence such as rape crisis or sexual violence referral centers must be easily accessible and provide “medical and forensic examination, trauma support and counseling for victims” (Article 25). Such support services must ensure both the immediate needs and long-term needs of victims of sexual violence. The EP Study identified sexual violence centers in 14 countries (BE, DE, DK, EE, ES, FI, FR, IE, LU, MT, NL, PT, RO, SE), some of which qualify as rape crisis or sexual violence referral centers, while others do not fulfil the Convention’s requirements on such centers. The EP Study noted that ratification of the Convention led to the setting up of such centers in a number of countries.

Finally, the IC requires that nationwide round-the-clock (24/7) helplines be available free-of-charge and confidentially for VAW and DV victims. The EP Study found that all countries have set up helplines for victims of violence. All countries except Luxembourg and Slovenia (helplines available but not 24/7) have one helpline available 24/7 for victims. However, helplines are not necessarily specialized helpline for victims of DV or VAW. An overview of the influence of the IC on the protection of and provision of services for victims is provided in Table 3.

Opposition to the Istanbul Convention in the EU and Turkey

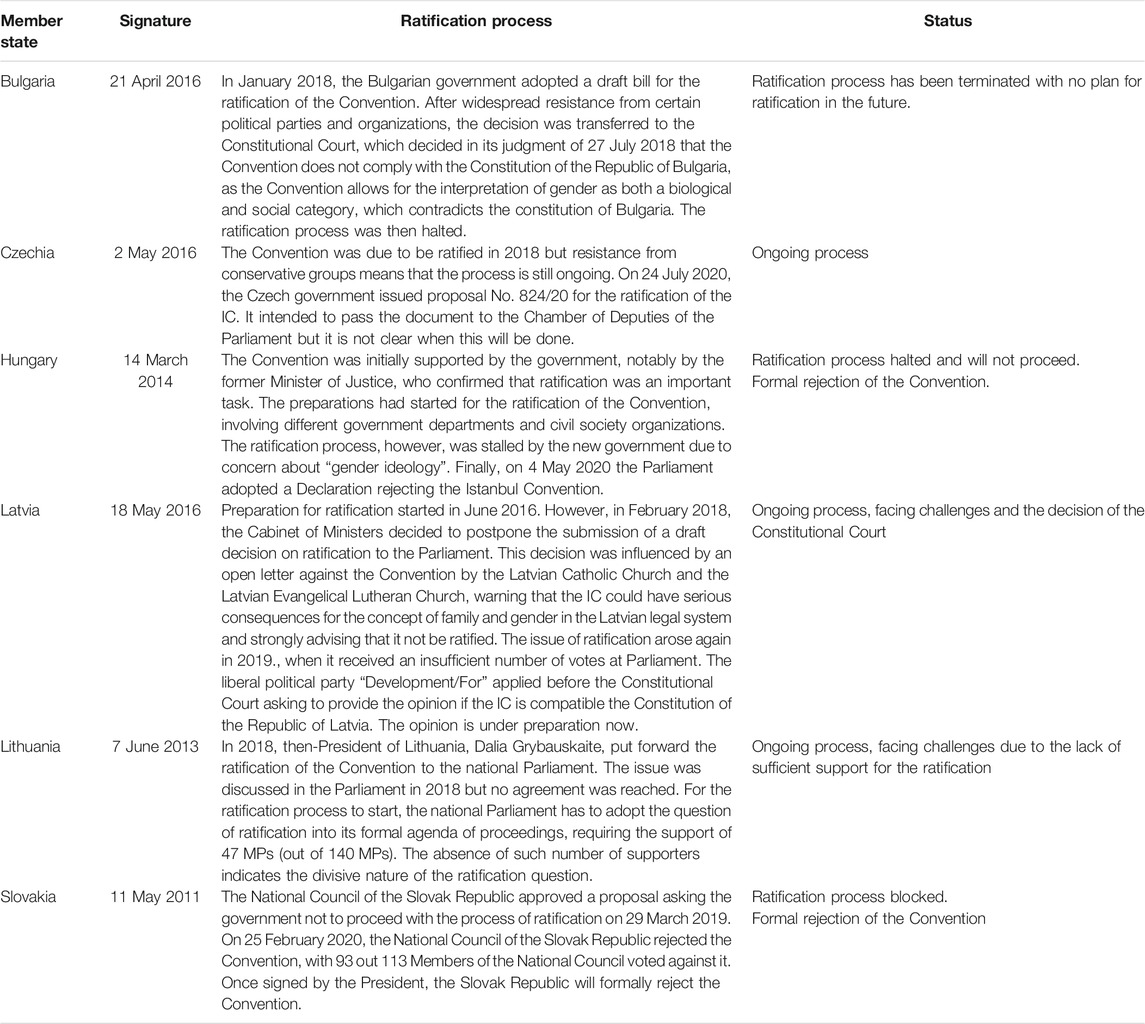

As stated earlier, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, and Slovakia have not yet ratified the Convention. Table 4 provides an overview of the ratification process in those six countries.

TABLE 4. Overview of ratification process in six non-ratifying countries (Meurens et al., 2020).

The signature alone of a Convention is not without legal consequences. Under international law, countries, which have signed but not yet ratified an international Convention are required to refrain from acts which would defeat the object and purpose of a treaty (Article 18 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties). This obligation remains until a state clearly expresses that it will not ratify the treaty, as it is the case for Hungary and Slovakia.

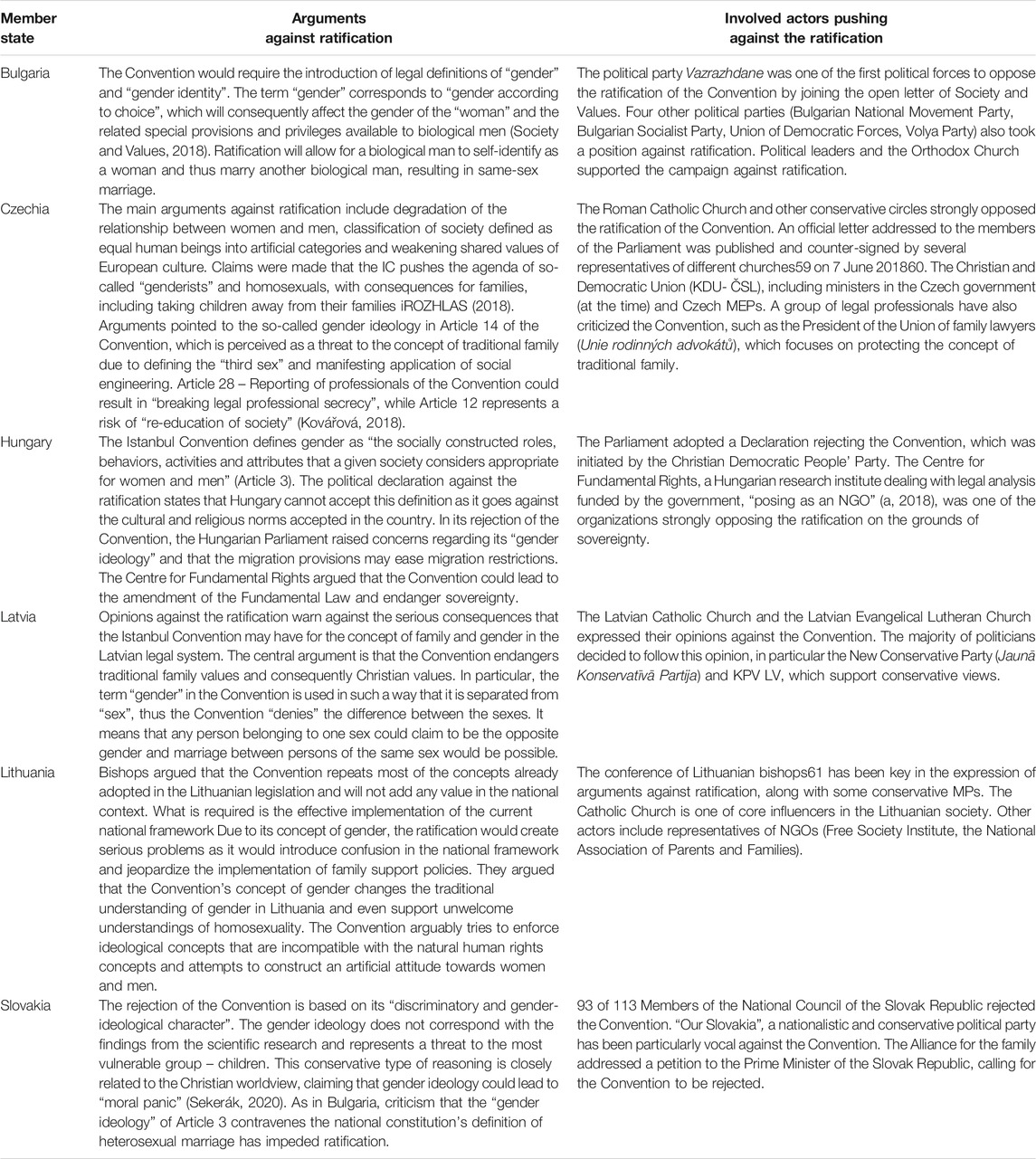

The EP Study found that various political actors and social factors have prevented the remaining six MS from acceding fully to the Convention. The EP Study identified the following common threads in the reasoning of the six countries in question. Table 5 provides some examples of these arguments against ratification, for the six countries.

TABLE 5. Overview of arguments and main actors against ratification in the 6 non-ratifying countries (Meurens et al., 2020).

Fears That the Istanbul Convention Opposes “Traditional Values”

In those countries, a number of arguments have been advanced against ratification of the Istanbul Convention. The most prominent ones being that the Convention constitutes a threat to the “traditional values” certain groups wish to uphold in their countries. Those so-called traditional values refer to an understanding of families as grounded in “natural” or “biological” roles of women and men, thereby excluding any LGBTQI+ rights. In Czech Republic for example, arguments include that the Convention directly attack families and lead to children being removed from their care (iROZHLAS, 2018).

Claims Denying Gender Is a Social Construct

Another common feature that the study identified is the claim that gender is a biological concept, not a social construct, mostly held by conservative and religious groups. This definition of gender as a biological concept, resulting in a binary understanding of gender, is considered to be in line with biological sex. The concept of gender is seen as an “ideology”, that aims “to eradicate natural order in society, causes a flood of abortion, and leads to the collapse of western culture” (Bosak and Vajda 2019, 78). However, the gendered dimension of violence of men towards women, in casu the attitudes that consider women as subordinate to men and that women and men have stereotyped roles, has been widely recognized in many international human rights standards, including in the IC. The Convention applies to all victims of DV, including men and children, but only asks States Parties to pay specific attention to women victims of GBV. The focus of the IC is on violence affecting women and DV affecting children, and does not regulate family values, same-sex marriages or other LGBTQI+ rights.

Resistance to Progressive Legal/Policy Reforms

These arguments focusing on the traditional values and views of families are at the center of conservatives’ political agendas in those countries. They present the Convention as a dangerous progressive legal or policy document, which could lead to national reforms at odds with those conservatives’ agendas. In some cases, conservative and religious actors claim gender mainstreaming is a global conspiracy (Zamfir, 2018) through the claim of gender ideology. Conservative and nationalist politicians have used claims of gender ideology to build a (foreign) enemy figure. This umbrella term refers to various issues linked to the liberal agenda, including reproductive rights, LGBTQI+ rights and gender equality, feminism that are framed as foreign-steered progressive reforms dangerous to national interests (Grzebalska and Peto, 2018). This is particularly the case in Hungary, where the IC is considered a threat to national sovereignty. The utopia of the traditional family constitutes the foundation of the nation. Women’s rights are therefore a threat undermining the nation to moral and biological deterioration (Grzebalska and Peto, 2018).

Involvement of Religious Actors in Policy-Making

The EP Study also found a strong involvement of religious actors and sometimes active campaigning against the Convention. Religious actors reinforce the discourse on so-called traditional views, by advocating against any reform that can threaten the “socio-political structure of domination”, whereby any change to the traditional roles of women (and men) would lead to social disruption (Zamfir, 2018). Religious actors are found to acknowledge the need to tackle VAW, yet they place VAW as a lesser concern to the conservative agenda of “families fitting the stereotyped roles of women and men” (Meurens et al., 2020). This is particularly problematic since there is a correlation between the patriarchal “traditional” views and women’s vulnerability to violence (Zamfir, 2018). Conservative and religious actors show concerns about the so-called global conspiracy attempting “to deny the biological differences between sexes, to undermine traditional female roles and to destroy the family” (Zamfir, 2018). For instance, in Slovakia, political actors have associated the Convention with gender propaganda against the “natural order” (Sekerák, 2020). Conservative religious actors make claims based on the “natural law perpetuating pseudo-biological contentions on male and female nature”, which embody a patriarchal vision of society (Zamfir, 2018).

Fear That the Istanbul Convention Will Lead to the Recognition of LGBTQI+ Rights

Another common thread among the six countries is the fear of the implication the Convention has in terms of same-sex marriage/partnership and LGBTQI+ rights. For instance, in Lithuania, religious leaders5 claimed that ratifying the Convention would result in having to teach about non-stereotypical gender roles and the full spectrum of sexual diversity. They argued that it would be against moral values and the education system of Lithuania.

Bans on same-sex marriage and fear of recognition of LGBTQI+ rights correlate with strong resistance against the Convention, including Croatia and Poland. Negative attitudes towards same-sex relationships are more prevalent in countries that did not ratify the Convention. The 2019 Eurobarometer on discrimination shows that few citizens agree with same-sex marriage in Bulgaria (16%), Hungary (33%), Latvia (24%), Lithuania (30%), and Slovakia (20%) (EC - European Commission, 2019). Similarly, citizens of those countries are among the least likely in Europe to agree with the introduction of a “third gender” option in public documents, as is the case in Bulgaria (7%), Hungary (13%), Slovakia (21%) and Latvia (21%) (EC - European Commission, 2019). While claims that the IC will lead to recognition of LGBTQI+ rights are unfounded, the broader anti-LGBTQI+ rights narrative is used to invalidate the Convention in countries with poorer record to protect LGBTQI+ rights. Indeed, same-sex marriage is not recognized in the countries that have not ratified the Convention.

While only six Central and Eastern European countries have failed to ratify the Convention, Paternotte and Kuhar, in their book volume on Anti-gender campaigns in Europe, noted an organized transnational trend of resistance to the ratification across Europe (Paternotte and Kuhar, 2017), and might be an indicator that in the near future, more countries might consider withdrawing from the Convention.

Finally, it should be noted that two countries, Poland and Turkey, have announced their intention to withdraw from the IC.

Discussion

One of the main assets of the IC is that it offers a comprehensive framework to address VAW, i.e. integrated policies, prevention, protection and prosecution, the so-called four Ps. The study identified a number of good practices with regard to these four Ps, as well as a number of remaining challenges, which are summarized below.

From the above, it is clear that the IC triggered positive amendments to existing legislation and/or the adoption of new legal measures in State Parties to tackle VAW and DV. For example in Malta, a legislative act was introduced that voided existing legislation that was inconsistent with the rights outlined in the Convention and in Sweden, the provision on restraining orders was expanded to include perpetrators who share a permanent resident with the victim, and provisions against forced marriage were added to the Penal Code. The evaluation of national implementation through the GREVIO monitoring mechanisms is expected to bring further legislative and policy changes as countries address GREVIO’s recommendations.

The Study also found that even non-ratification could lead to positive, although less extensive, legislative developments to tackle VAW and DW, which are in part influenced by the Convention. In Czech Republic, for example, the government introduced legislation in 2018 to better align its legislative framework to requirements of the international community in the area of VAW and DV (i.e. the Istanbul Convention). It is important to note that the gender-neutral approach in the Convention has been criticized for failing to recognize the gendered nature of all forms of violence it covers (with the exception of FGM, forced abortion and forced sterilization). This gender-neutral approach of the IC is reflected in the adoption of gender-neutral legal texts and policies in most of the EU MS, with the exception of Sweden and Slovakia who have established a gender-specific criminal offence. While violent conduct must be criminalized regardless of the sex of the offender, the gendered nature of violence should be reflected in either specific gender-based violence criminal offences or in the aggravating circumstances linked to specific VAW and DV conduct. In addition, this gender-neutral approach is connected to the lack of specific criminal offences in several countries for violent conduct that is typically gendered, such as FGM or forced sterilization, which instead falls under broader offences such as bodily harm, or, in the case of sexual harassment, is limited to the workplace (Meurens et al., 2020).

The IC recognized physical, psychological, sexual and economic violence as forms of DV, but only seven countries (BG, HR, LT, LV, MT, RO, TU) specifically refer to all 4 forms in their legal definitions of DV. Consequently, victims might have difficulties in seeking adequate protection or legal redress, if DV is not legally defined or if only some forms of DV are referred to. It should be noted that all forms of DV are frequently covered by other criminal offences, albeit not within the context of DV and not covering all manifestations of the violence. This lack of legal recognition is reflected in the scope of protection orders that are available in the case of DV, as in only 10 countries (BE, BG, FR, HR, LT, LV, MT, RO, SI, TU) protection orders cover all forms of violence.

The IC was also influential in prompting MS to establish new criminal offences for those types of conduct that previously fell under various broader offences, such as stalking, forced marriage and FGM. The EP Study clearly showed that countries that have not ratified are less likely to fully recognize those forms of violence. For example, none of the six non-ratifying countries have explicit criminal provisions on FGM, creating gaps in the legal protection. This absence of specific criminal offences renders the violence invisible, including its legislative, policy and support service responses and data collection.

14 countries (CZ, DE, DK, EE, FI, FR, IT, LT, MT, NL, PT, RO, SE, TU) adopted a NAP/strategy on VAW and DV since ratifying the Convention, four MS (AT, EL, HU, SI) have no NAP/strategy on VAW and DW, while an additional four adopted one (BE, CY, LV, SK), which has expired since. Two MS (BG, LU) have a strategy on gender equality partly covering VAW. This mix of national policy commitments reveals that countries have committed to practical action to varying extents and with different priorities. This shows that more efforts are needed to put or keep DV and VAW high on the policy agenda. Nevertheless, stakeholders reported that the Convention’s influence is evident in increased awareness of the issue of VAW and DV at policy level and in society. They noted that the Convention has empowered professionals at all levels, who have benefited from a new impetus and heightened sense of awareness of the issue. The Convention has helped to bring the issue of VAW and DV to the forefront of policy-making across EU countries and elevated the need for victim protection (Meurens et al., 2020).

The IC requires MS to provide a range of general and specialized support services. The Study found that both the IC and the Victims’ Rights Directive have influenced the availability of support services across the EU. Since the ratification of the IC, 10 countries (BE, DE, FI, FR, LV, NL, PL, PT, RO, TU) established new specialized support services. Rape crisis centers or sexual violence referral centers have been established in 14 ratifying countries (BE, DE, DK, EE, ES, FI, FR, IE, LU, MT, NL, PT, RO, SE), and the IC has directly contributed to setting up such services in a number of countries. In the countries that have not ratified, only Czech Republic and Hungary have both general and specialized support services in place.

While the majority of countries have regulated and/or standardized risk assessment/management processes in place at national level, a significant number do so on a more ad hoc basis and with limitations to certain regions or actors. Although ratification of the Convention prompted at least two countries to adopt new standardized tools or procedures for risk assessment or management, nine others (BE, BG, DE, DK, HR, HU, IT, LU, LV), including three non-ratifying countries, have no regulated/standardized risk assessment/management processes. This means that a victim’s safety is not guaranteed by robust and well established due diligence processes, undermining the quality and consistency of protection offered to victims of VAW and DV across Europe (Meurens et al., 2020).

The Convention brings key innovations and strengthens the legal framework to tackle VAW and DV effectively by addressing the root causes of violence. Those innovations include new legal offences, a requirement of due diligence, a coordinated and integrated approach to eliminating VAW, a requirement to set up a range of dedicated victim support services and protection tools, and obligations to tackle the root causes of violence and prevent further violence. The IC also established a monitoring mechanism to ensure effective implementation of the Convention through an independent body of experts (GREVIO) and a political body (the Committee of the Parties). GREVIO monitors the implementation of the Convention through a reporting system, data, expert analysis and country visits. Its evaluations and recommendations, while not legally binding, indicate areas of improvements for countries to align with the Convention and prompt better tackling of VAW. In ratifying the Convention, countries must designate or establish a coordination body with responsibility for the coordination, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of policies and measures. This requirement has generated several good practices in MS, strengthening coordination between civil society actors and government institutions and recognizing the need for a multi-sectorial approach (Meurens et al., 2020).

The EP Study also demonstrated that opposition to the IC exists and arises for a number of reasons, all of which are rooted in efforts to preserve certain “traditional” ideas. Although the content and scope of the Convention does not undermine these ideas, conservative and religious agendas fear that ratifying will trigger other progressive changes. The most common arguments preventing the remaining six MS from acceding fully to the Convention center on a set of (often linked) assumptions: that the Convention is opposed to traditional values; that gender is a biological construct; that the Convention is at odds with conservative nationalist political and/or religious agendas; and that it will lead to the recognition of LGBTQI+ rights. The scope of the Convention applies to violence affecting women, and specifically to domestic violence experienced by women, children and men. The Convention does not regulate family values, same-sex marriage or other LGBTQI+ rights. It mentions gender identity and sexual orientation once, in a provision requiring authorities not to discriminate when providing victims’ rights, victim support or any other measures under the Convention. In the (contested) provision requiring ratifying countries to promote measures to eradicate prejudice based on the idea of the inferiority of women or stereotyped roles for women and men, the Convention provides a wide margin of discretion in implementation, allowing maximum flexibility for each country to adopt the measures best suited to its national context. In addition, the persistence of stereotyped roles has been widely recognized as the root cause of VAW by the social sciences and international human rights law. This mismatch between the actual requirements of the Convention and the claims against it has highlighted the need to acknowledge the wider, socio-political contexts within which opposition is arising. A worrying thread in the resistance to ratification is the involvement of religious actors in political decision-making, often directly pressuring policymakers. It is also directly linked to the rise of nationalist political agendas, which are often intolerant to social progress and driven by a stereotyped (patriarchal) vision of families. The Convention and the concept of “gender ideology” are used to build a (foreign) enemy figure. This “gender ideology” discourse, as well as victim-blaming attitudes, have been reported as key obstacles for tackling VAW and DV in several countries (CZ, EE, HR, HU, LT, LV, RO, SK, TU), and point to the importance of continuing efforts to adopting prevention measures, such as awareness-raising to the general population, education and training for (future) professionals and preventive intervention and treatment programs for offenders. A discourse of threat to national sovereignty is used to resist various issues attributed to the liberal agenda, such as reproductive rights, LGBTQI+ rights and gender equality. This discourse also contributes to create a lack of trust in international and European organizations and institutions (Meurens et al., 2020).

Recommendations

The EP Study made a number of recommendations, targeted at the EU institutions and the Member States, to tackle VAW and DV. With regard to the IC, the EU has competence on matters related to judicial cooperation in criminal matters, asylum and non-refoulement, as well as gender equality and gender mainstreaming. Both the European Commission and the European Parliament can strengthen the framework on VAW and DV, and tackle it through initiatives and funding, but it is the EU MS themselves that should provide full effect to all of the Convention’s provisions (Meurens et al., 2020). Five overarching recommendations for the EU and the MS were formulated and extensively discussed in the EP study, and are briefly highlighted below.

Strengthen the Legal Framework by Fully Reflecting the Convention’s Substantial Law Provisions in the Legislation

The IC ratification led to positive changes in the national legal and policy frameworks in many countries. However, several gaps in national legal frameworks have also been identified in relation to substantial criminal law provisions, including a lack of comprehensive legal definitions of DV and its four forms of violence, and a lack of specific criminal offences for all the conducts laid down in the Convention. Lastly, the conclusions of the EU to the Convention have been pending at the Council since 2017. Therefore, the EP Study suggested that the EP continues to call for the CoE to conclude the IC. Furthermore, EU legislation should be aligned with the IC and adopt a Directive on VAW and DV that complements the already existing framework. In the next revision of the TFEU, protection on the ground of gender and gender identity should be introduced. However, it should be noted that the EU would only be required to implement the IC within its limits of its competencies under the Treaties (Meurens et al., 2020).

The EP Study also recommended that Member States that have not yet ratified the IC should do so. To facilitate the ratification, they could envisage adopting a declaration that the ratification of the Convention does not entail the introduction of a “gender ideology” in the national legal framework, in a similar manner as Croatia’s declaration. MS should also conduct a review of their legal framework, to identify necessary changes in all areas covered by the IC, paying attention to GREVIO recommendations, reflecting the gender dimension of violence and ensuring all violent conducts are fully and effectively criminalized and prosecuted. All stakeholders, including NGOs, equality bodies and experts, should be involved in this review process.

Ensure the Full Implementation of the Istanbul Convention’s Provisions

In order to tackle VAW and DV, the framework must be fully implemented and requires concerted efforts and commitments by all actors. The most common issue in relation to the national policy frameworks is the lack of a holistic, coherent, and nation-wide policy approach (Meurens et al., 2020).

In order to ensure the implementation of the IC in all its aspects, the EU should develop a comprehensive framework of policies, programs and other initiatives to tackle VAW and DV and the exchange of (the implementation of) good practices regarding prevention, prosecution, protection could be facilitated. The EU should also allocate sufficient and adequate resources to the implementation of the IC through its funding programs.

At Member State level, recommended key actions include ensuring that VAW and DV are a policy priority and that the IC is fully implemented through legal and policy measures. MS should provide a comprehensive national response to VAW and DV, addressing the 4 Ps and all forms of physical, psychological, sexual and economic violence.

Ensure an Integrated, Gender-Sensitive, Intersectional and Evidence-Based Policy Framework

Another key challenge identified in the implementation of the Convention is the lack of coordinated action in practice. Coordination among the relevant services and actors can result in providing better responses to violence and to manage the cases effectively. In addition to being coordinated and integrated, the response should be gender sensitive and intersectional, as a gender-neutral approach to legislation, policy and funding, results in inadequate provision of services and protection of victims (Meurens et al., 2020).

The EP Study recommended that at EU level, the European Commission could encourage and facilitate the exchange of best practices on integrating an intersectional and gender sensitive response to VAW. At MS level, it is recommended that a comprehensive, multisectoral action plan is developed that tackles all forms of VAW and DV, is gender sensitive and takes an intersectional approach. To implement, monitor and evaluate all measures, a coordinating agency should be appointed that has a clear mandate and sufficient resources, and that is able to update the measures on a regular basis. Collecting disaggregated data at regular intervals and disseminate these data to the general public is also recommended, in order to raise awareness on the issue of VAW and DV and keep it high on the agenda.

Ensure Adequate Prevention, Protection and Service Provision

As the EP Study showed, the current provision of support services for victims of VAW fails to meet the IC’s minimum standard in most European countries. To tackle this, key actions at EU level could include allocating resources that support the prevention of violence and the protection of victims through funding programs of the EU. Specific attention should be given to support pilot projects to implement best practices in terms of support services and prevention initiatives. Furthermore, it is recommended that the implementation of the Victims’ Rights Directive is closely monitored, and that all the provisions of the Directive are fully implemented for all victims in the EU. Member States on the other hand, should ensure the establishment of general and specialized support services, helplines, shelters and rape crisis or sexual violence referral centers in line with the Convention’s requirements. Moreover, in all measures and actions to prevent VAW and DV, MS should pay particular attention to addressing the gender inequalities causing VAW and DV, and to the prevention of violence towards women and children in vulnerable situations (Meurens et al., 2020).

Promote Gender Equality, Education and Awareness-Raising on the Various Forms of Violence and Gender Stereotypes

The most persisting challenge identified for the full implementation of the Convention is the attitudes, prejudice and persisting stereotypes with regard to gender equality. Awareness raising and education on various forms of violence and gender stereotypes can have a positive impact on the overall effectiveness of the IC. The EP Study therefore recommended, at EU level, that awareness should be enhanced on the benefits of the Convention by e.g. publishing a booklet to demystify and counter the transnational spread of misconceptions and myths with regard to the IC. In addition, a number of measures could be taken to strengthen awareness raising and education, including the exchange of good practices and funding their implementation. At Member State level, key actions could include, adopting measures to ensure students at all education levels are aware of the various forms of VAW and DV and how to seek support. Education measures should prioritize educating students on the issue of gender stereotypes, victim blaming and stigma. Educational material should be revised to tackle stereotypes. Training curricula of teachers could be adapted in order to provide them with teaching tools to educate on reducing gender stereotypes and eradicating prejudices. At national level, funding of awareness-raising activities and campaigns tackling victim-blaming and gender stereotypes are equally recommended. And finally, all professionals that are likely to be in contact with victims (law enforcement, healthcare, justice, etc.) should be trained on how to best support victims and reduce gender stereotypes and prejudice in their response (Meurens et al., 2020).

Author Contributions

NM and HD collected the data. NM, HD and EL analyzed the data. All authors were involved in the writing process. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

This paper is based on a study that was commissioned by the European Parliament’s Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs at the request of the FEMM Committee. We greatly acknowledge the FEMM Committee for granting permission to use the report for this paper and the authors and country experts, that contributed to the report on which this paper is based, i.e. Abdallah C., Charitakis S., Chowdhury N., D’Souza, H., Dupate K., Gay-Berthomieu M., Guney G., Jakubowska K., Kovářová K., Laas A., Marshall R., Milovanovic J., Mohamed S., Nikolova M., Pavlovaite I., Regan K., Vajai D., Wildoer E., and Ulcica I.

Footnotes

1Meurens N, D’Souza H, Mohamed S, Leye E, Chowdhury N, Charitakis S and Regan K. Tackling violence against women and domestic violence in Europe. The added value of the Istanbul Convention and remaining challenges. FEMM Committee, European Parliament, 2020. Available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2020/658648/IPOL_STU(2020)658648_EN.pdf

2Austria (AT), Belgium (BE), Bulgaria (BG), Croatia (HR), Cyprus (CY), Czech Republic (CZ), Denmark (DK), Estonia (EE), Finland (FI), France (FR), Germany (DE), Greece (EL), Hungary (HU), Ireland (IE), Italy (IT), Lithuania (LT), Luxemburg (LU), Latvia (LV), Malta (MT), Netherlands (NL), Poland (PL), Portugal (PT), Romania (RO), Spain (ES), Sweden (SE), Slovenia (SI) and Slovakia (SK)