95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Hum. Dyn. , 21 July 2021

Sec. Environment, Politics and Society

Volume 3 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fhumd.2021.654311

This article is part of the Research Topic Political Ecologies of COVID-19 View all 11 articles

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Peruvian government failed to protect its sparsely populated Amazon region. While infections were still rising, resource extraction was quickly approved to continue operations as a declared essential service that permitted an influx of workers into vulnerable indigenous territories despite weak or almost absent local healthcare. This article analyzes territorial counteraction as an indigenous response to pandemic national state failure, highlighted in a case of particularly conflictive stakes of resource control: Peru’s largest liquid natural gas extraction site Camisea in the Upper Amazon, home to several indigenous groups in the Lower Urubamba who engaged in collective action to create their own district. Frustration with the state’s handling of the crisis prompted indigenous counteraction to take COVID-19 measures and territorial control into their own hands. By blocking boat traffic on their main river, they effectively cut off their remote and roadless Amazon district off from the outside world. Local indigenous control had already been on the rise after the region had successfully fought for its own formal subnational administrative jurisdiction in 2016, named Megantoni district. The pandemic then created a moment of full indigenous territorial control that openly declared itself as a response and replacement of a failed national state. Drawing on political ecology, we analyze this as an interesting catalyst moment that elevated long-standing critiques of inequalities, and state neglect into new negotiations of territory and power between the state and indigenous self-determination, with potentially far-reaching implications on state-indigenous power dynamics and territorial control, beyond the pandemic.

Despite one of the strictest lockdowns in Latin America, Peru quickly became one of the most affected countries worldwide, taking first spot in the tragic global ranking of highest COVID-19 deaths per capita (Mortality Analyses–Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center, 2021). Amazon indigenous groups in the country struggled tremendously as the pandemic added, in many cases, another layer of difficulty on what had already been dire situations. They raised their voice against the delayed and half-hearted support the national government offered, and, above all, for not having been consulted and included as the national strategy allowed extractive operations to continue in their territories despite of the health crisis. They deployed their own measures that included the closure of their territories and local self-organization to promote traditional medicines, as well as widespread protests across the Amazon against expanding extraction and breached agreements between the company and communities, which ended in three deaths of indigenous protesters in August 2020 during the takeover of Canadian PetroTal facilities in the northern Peruvian Amazon.

As an example of such flaring tensions of the coronavirus pandemic across the Amazon and the world, this article focuses on one of Peru’s clashing hotspots for industrial hydrocarbon extraction, rainforest biodiversity, and indigenous rights in what has become known as the Amazon resource extraction frontier: located in the Lower Urubamba Valley in the southeastern Peruvian Amazon, close to the Brazilian border and far from a connecting road system, is the country’s largest natural gas extraction site Camisea, Peru’s flagship energy project that produces more than 60% of the country’s hydrocarbon extraction (Perupetro, 2019). Camisea has been running for more than 3 decades, carefully navigating between national support, global scrutiny, mounting environmental impacts, intercultural conflicts, and political debates, which have all shaped the operational standards of energy extraction in the country (Bebbington and Humphreys Bebbington, 2009; Fontaine, 2010; Peirano, 2011).

The region gained its own district status in 2016 at the insistence of local communities and indigenous organizations, arguing that the rent allocations and decision-making based on the administrative–territorial arrangements were still rooted in colonial structures, and had not granted them rights or improved their living conditions instead threatened their livelihoods. Indigenous territorial control was the key issue, as Daniel Rios, Megantoni’s current authority and former president of the pro-district campaign committee, remarks: “Fellows, it has not been easy, but we walked disagreeing everywhere, this is how this district headed […] At the council of ministers they disapproved the district because of the name of the district [that we] had complemented with ‘State of Indigenous Nations’, and that is what they told us. So, we changed the name solely to Megantoni and it was approved […] Fellows, the thing was to get the district be approved […]We needed the district to solve the overwhelming problems of our communities […]We have taken a leap creating the district.” (authors’ own translation; source Municipalidad Distrital de Megantoni, 2020a).

Peru has made itself economically dependent on natural resource extraction that routinely enters indigenous territories. The country’s legal framework and government institutions have, in design and practice, never guaranteed the protection of indigenous rights to their land, territories, and the exercise of traditional authorities and self-government.

Over the first months of the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, those contradictions and indigenous frustration were further laid bare. Unable to implement or trust Peru’s emergency lockdown measures that had been nationally declared, Amazon’s indigenous communities mobilized protests and closure of their territories. Tensions over territory and access control flared up, fueled by debate over the (in)action and clashing interests of the local and national state. Simultaneously, it helps to revisit the multiple dimensions of the territory and indigenous and communities’ access to resources (Ribot and Peluso, 2009) as the ability of indigenous local people to derive benefits from material and symbolic dimensions of the state’s administrative territory, beyond its understanding of property ownership regimes.

Our interest in this analysis addresses the competing rationales of state-based and indigenous territorial control during the pandemic. Painted as a resource extraction zone with a sparse population, Amazonia had been routinely overlooked in Peru’s early COVID-19 national health strategies. Soon after, energy extraction was even declared an essential service that mandated openness of the Amazon to an influx of workers, even while cases of infection were still rising in the region. In response, frustration with the state’s handling of the crisis prompted local action of indigenous communities in Megantoni to take COVID-19 measures and territorial control of their district into their own hands. Although they did not declare opposed to hydrocarbon operations, they blocked their remote district off entirely from the outside world, through simple but effective means of physically preventing river traffic. This created a moment of de facto indigenous territorial control and an openly declared replacement of a neglectful and exploitative state, catalyzed by the emergency momentum of the pandemic.

Drawing on theoretical perspectives of governmentality and indigenous self-determination, this article examines Peru’s Megantoni case for two advantages to explore political ecologies of COVID-19 in the Amazon. First, it sheds light on the understanding of the complex, nonlinear, and ambivalent dimension of indigenous power dynamics in which they internalize, digest, and reexpress dominant norms during COVID-19 as an attempt to resist extraction while confirming it. Second, it adds on understanding the crucial role of territorial local control in reconfiguring sociospatial power relationships of the so-called remote extractive areas. Peru must carefully reconsider both the situation of the indigenous peoples that call the Amazon home and the role of the absent or intermittent perceived nation-state in the larger region.

Growing literature on community responses to extractive projects in Latin America is examining the strategies of social movements to resist or halt extractive projects in their territories, but there is still a thin understanding of other forms of indigenous agency in the consolidation of interests and territories while engaging with extraction projects (Bebbington and Humphreys Bebbington, 2012; Frederiksen and Himley, 2020; Van Teijligen and Dupuits, 2021). Drawing on a post-structural political ecology approach, this study analyzes power relationships and indigenous tactics of self-governance during COVID-19 in the case of Peru’s most emblematic gas extraction project in which indigenous communities have, for decades, engaged with corporations while trying to reconfigure their control over their territory.

Two concepts and perspectives are at the core of this theoretical framework: governmentality and indigenous self-determination. These two concepts combined enable a platform that helps us analyze more nuances of indigenous agency, particularly those beyond a dichotomy of “powerless” and “powerful” that would focus on top-down workings of power while failing to acknowledge how power can be exercised from the bottom (Fletcher, 2007), and how indigenous people co-articulated manifestations of neoliberalism and extractivism on their lands (Anthias, 2018; Radcliffe, 2019). These concepts open more avenues to explore indigenous “true interests” and their strategies during the COVID-19 crisis.

For Foucault, the exercise of power is a broader context that signifies government as shaping and directing the possible conduct of individuals or groups and the possible outcomes, in short “a set of actions upon other actions” (Foucault, 1982, 789). Li (2007) defines governmentality as the “conduct of conduct” that surrounds governmental actions, embedded as “educating desires and configuring habits, aspirations, and beliefs” (Li, 2007, 275). From such a perspective, the state interacts with, and depends on, a dynamic and complex assemblage of collective and individual objects as well as social practices. Individuals are examined for how they are transformed into subjects, and how a subjectification is normalized that categorizes individuals as subordinate to others and to themselves (Foucault, 1982).

Governmentality analysis of extractive capitalism often points out how governmental practices have normalized extraction projects by prioritizing maximum economic gain over the lives and livelihoods of local populations that stand in the way of resource-based development such as in Peru (Andreucci and Kallis, 2017), or through the workings of corporate practices aimed to moderate the behavior of local communities against extractive corporations and achieve the “social license to operate” (Szablowski, 2019; Buu-Sao, 2020). Nevertheless, the power relationships in which the “conduct of the conduct” is exercised typically offer multiple points of contact through which processes can be negotiated, consented, or rejected (Allen, 2003; Allen, 2004), with unpredictable and ambiguous outcomes that simultaneously resist and confirm exclusionary and subordinating norms (Ahlborg and Nightingale, 2018).

A surge of global, local, and digital social action alongside the 2020 Coronavirus pandemic provides us with a unique opportunity to study counter-behaviors, and their various points of resistance against normalized treatments and portrayals of some vulnerable groups. Among indigenous peoples, this may include any treatments or portrayals as non-agent victims of dominant government rationalities.

As an international norm and concept, self-determination is rooted in freedom and equality for individuals and groups, in a way that entitles them to participate, change, or transform governing institutional orders, including those that are seen as a remedy of historical marginalized processes (Anaya, 1996). Broader purposes and goals of indigenous self-determination movements can entail 1) greater autonomy from a nation-state as a form of self-government; 2) greater participation in decision-making institutions at higher political levels such as legislatures or electoral coalitions; or 3) institutional changes that expand indigenous self-determination or seek to obtain state power to achieve social change (Hawkes, 2002; Jackson and Warren, 2005; Cornell, 2015; Petray and Pendergrast, 2018; Merino, 2020; Sidorova and Rice, 2020). The literature of self-determination emphasizes plurality and diversity of indigenous activism to continuously contest hierarchical relationships between governors and their subjectivities, while understanding how these produce and expand their self-determination through state, market, civil society, coalitions, and everyday practices (Gonzales and Gonzalez, 2015; Merino, 2020).

The long and active history of indigenous movements has addressed questions of territory and multiple ontologies at its heart, including as a political arena in which various actors try to exercise power. To this day, the struggle of indigenous communities toward legal recognition of land titles has not been enough to decolonize dominating rationalities that consistently privilege the rights of certain ethnic groups or political settlements (Inter-American Commision on Human Rights, 2009; Bryan, 2012; Stetson, 2012; Merino, 2015; Halvorsen et al., 2019) and further ongoing dispossession of lands (Anthias, 2019). This tension was evident in Latin America during the last extractive boom in the early 2000 s when states facilitated a rapid expansion of resource exploitation into indigenous territories, countered by growing social protest for the defense of territorial and indigenous rights (e.g., Stocks, 2005; Bebbington and Humphreys Bebbington, 2011; Bryan, 2012; Coombes, Johnson, and Howitt, 2012; Pacheco, Barry, Cronkleton, and Larson, 2012; Kröger and Lalander, 2016).

This article presents a qualitative case study of an ongoing environmental, indigenous, and COVID-19 crisis to highlight valuable insights to social vulnerabilities in a fast-moving pandemic, including unexpected outcomes of events and actions (Teti et al., 2020). The qualitative approach examines the different perspectives, meanings, interpretations, and diverse dimensions of the social world in depth, context, complexity, and multidimensionality (Flyvbjerg, 2006; Hay, 2010; Creswell, 2013; Hammersley, 2013).

Megantoni as a region and hydrocarbon extraction project stands out as a particularly insightful instrumental case (Stake, 2003) for several reasons. First, Camisea’s Megantoni District and its local organizations represent an opportunity to explore indigenous strategies that, rather than pursuing totalizing changes, promote alternatives of resistance alongside, and within, the existing apparatus of the state and hydrocarbon corporations. In contrast, many other indigenous self-determination and autonomy struggles in Latin America have focused, or continue to focus, on anti-systemic activism, and challenge the state apparatus and implement legal autonomy as, for example, in progressive constitutions of Ecuador and Bolivia (Van Cott and Lee, 2010; Merino, 2020). Second, analyzing the roles of the territorial and access control in Megantoni during the pandemic help understand indigenous nonviolent conflict through different dimensions of power (material, cultural, and political–economic) that can be subtle but crucial components in indigenous territorial defense and exercising self-determination, and finally, the Megantoni case lets us examine forms of emerging indigenous leadership that combine de facto and de jure strategies in the so-called co-living socioenvironmental conflicts that dominate extraction landscapes in Peru, to secure their rights beyond ownership of the extraction revenues (Presidencia del Consejo de Ministros–Viceministerio de Gobernanza Territorial, 2019; Defensoria del Pueblo Peru, 2020).

The dataset of this study includes historical secondary data with a broad variety of public texts, formal government documents, reports, newspaper articles, and maps from different stakeholders published between 1970 and 2020 such as archives, reports, and public documents from indigenous organizations, governmental, and nongovernmental institutions (see Figure 1). For events during the 2020 COVID-19 lockdown that made local visits impossible, the analysis is based on a remote data collection of online and print sources through a systematic document search of Megantoni and its gas extraction in the first half of 2020. It includes online public official information from the national and subnational governments, data from Peruvian media and investigative journalists, public statements from activists and energy companies, and publicly available social media (Facebook and Twitter) accounts from Megantoni authorities and indigenous leaders. The remote data collection of the lockdown is complemented by a larger pre-pandemic fieldwork dataset collected in Megantoni, Cusco, and Lima over 12 months from 2018 to 2019 including active interviews and contacts maintained into 2020.

Diversity of voices and perspectives are a key element of this analysis. Typically, a remote data collection as conducted during the lockdown bears the danger of overrepresenting dominant and privileged voices that have better access to public and formal online publication, while excluding opinions and silences from marginalized groups (Boyle, 2009). In order to include different voices and perspectives, the dataset was contrasted and triangulated with 75 face-to-face semi-structured interviews collected during the pre-pandemic fieldwork between 2018 and early 2020 (see Table 1). Additional face-to-face zoom conversations were conducted with local participants from the previous fieldwork data collection in 2020. Zoom conversations complemented previous interviews with ongoing developments of the pandemic.

The literature review identified general groups of participants that are central to understand the history and the negotiation dynamics and power relationships. Selection criteria for individuals then followed a purposeful sampling with maximum variation of perspectives, depth, and experience of the phenomenon. For indigenous perspectives, participants were selected based on purposeful sampling that considers their historical and contemporary relevance, cultural diversity, logistic accessibility, and voluntary desire to be part of the study as well as location related to the hydrocarbon project and Megantoni capital (see Table 2).

The content was analyzed in an iterative process in which emerging themes were coded based on identified issues and narratives around the forest, ethnicity, governmental institutions, and hydrocarbons. In order to develop common themes, verify details, contradictions, and contested perspectives, the process included triangulations between participants of each stakeholder group, across the different groups, and across information sources.

Peru holds a significant share of the Amazonian rainforest—second only to much larger Brazil— and industrial resource extraction is widely identified as the main pillar of the Peruvian economy (OECD, 2015). Despite the increasing performance of macroeconomic indicators during the last extractive boom, long-standing inequalities and uneven subnational development persist (Orihuela et al., 2019; Irarrazaval, 2020). In a hotly contested neoliberal reform, the Peruvian government vastly expanded Amazon oil concessions from 13% in 2007 to 73% by 2010, far above the South American average, and routinely approved new hydrocarbon blocks in indigenous communities and protected areas (Finer and Orta-Martínez, 2010; Red Amazónica de información Socioambiental Georreferenciada, 2012). Indigenous territories in the Peruvian Amazon, typically located in highly biodiverse rainforest ecosystems, now often see resource extraction operations in their territories that are driven by destructive profit regimes and protected by the national government.

Despite a democratic political system and an estimated 18% of the population self-identifying as indigenous (Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informatica (INEI), 2018), highly pro-extractive development and investment narratives over indigenous territories have remained driven in Peru by its economic elite, particularly by actors who engage in corrupt forms of governance (Crabtree and Durand, 2017). In an analysis of sovereign power and governmentality during the dramatic case of Amazon indigenous unrest in 2006 in Northern Peru’s Bagua, Drinot (2011) highlights how the neoliberal agenda of Peruvian President Alan Garcia was racialized and inserted in traditional elite projects against indigenous people. Extraction projects have been at the center of these difficult power dynamics. Given their limited representation at the national level, Peruvian Amazon communities have long identified a disconnect between state interests and their rights, and thus maintained distrust of state institutions. Over recent decades, indigenous resistance was rampant and intermittent, primarily dispersed at a local level (Rice, 2012; Arce, 2014), and narrated through heterogeneous stereotypes that distinguished between Andean and Amazonian indigenous peoples (McDonell, 2015).

Local communities have actively pursued formal, informal, and hybrid mechanisms including lawsuits to contest extraction projects within their territories (Szablowski, 2011; Walter and Urkidi, 2017). Based on the heart of local communities’ argument, Arce (2014) summarizes two types of conflicts in Peru: 1) “demands for rights” in which usually environmental discourse seeks to prevent or halt the expansion of extractive projects in their territories, and 2) “demands for services” connected with the distribution of revenues. However, indigenous strategies can have various entangled patterns of causation and motivations, and how indigenous groups combine both strategies to produce and or expand their self-determination in Peruvian context remains under-explored.

Important shifts of power took place between the national and subnational levels during the new extractive boom, and its deficiencies were obvious during the COVID-19 crisis. Decentralization reforms since 2002 created a contradictory subnational landscape of overlapping practices and responsibilities with other levels of government, offering new possibilities to challenge, contest, or legitimize extractive projects in their territories (Eaton, 2017; Bebbington et al., 2018; Gustafsson and Scurrah, 2019). Despite their great potential to understand indigenous acceptance or rejection to extractive projects vis-à-vis the emergence of new local leaderships, the connections of decentralization, and indigenous strategies in dealing with extractivism are little understood (Arce, 2014; Bland and Chirinos, 2014).

COVID-19 shifted the confusions of subnational politics and authority to the center stage. Using arguments of citizen protection, the Peruvian central government imposed one of the strongest militarized lockdowns in Latin America as an attempt to take control of infection spread among the population. More interestingly, the national state ambiguously appealed to self-care and isolation of its citizens, while simultaneously encouraging industrial extraction and flows of workers to continue, even if this meant substantial added infection exposure of remote indigenous territories that already had the poorest health services in the country. In short, the state decided which citizens should live, and which should be risked or sacrificed for the greater good. The pandemic health emergency once again exposed the Peruvian state government’s rationalities amid its vast uneven territorial and cultural heterogeneity, as well as its disarticulation at different levels of the state. Indigenous protests and mobilizations in the country broke out in various ways as the novel coronavirus made its way through the indigenous communities. By using a political ecology analytical lens, this analysis aims to contribute to this contemporary and highly relevant debate with a nuanced understanding of the interplay of indigenous resistances, subnational tensions, and territorial control and access beyond economic performance explanatory factors, applied to a poignant, and highly symbolic, case.

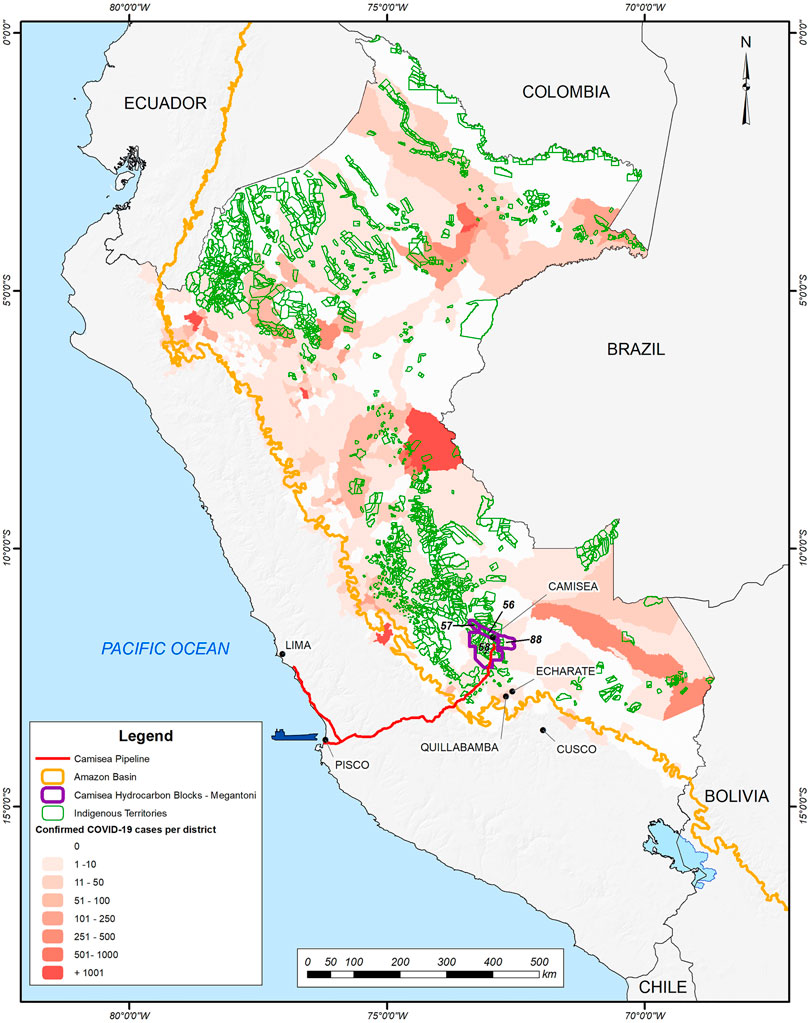

Camisea is an emblematic natural gas project in the Peruvian Amazon that has had a tremendous impact in Peru and attracted international debate. Camisea’s natural gas flows from the Amazon westward to Peru’s liquid natural gas export facility on the Pacific coast (see Figure 2). Peru was the first country in South America to drill an oil well, but still had problems to satisfy its internal energy demand. Camisea changed this by introducing natural gas as an alternative source of energy. There are over 12,000 BCF verified reserves of natural gas in Camisea (Ministerio de Energía y Minas Perú, 2016), which have transformed the country’s energy matrix, and an estimated 36% of Peru’s electricity production now comes from Camisea (Comité de Operación Econó)

FIGURE 2. Map of Camisea Gas Project Extraction. Source: Own elaboration 2020, using data from Confirmed COVID-19 cases May 25, 2020 (Ministerio de Salud Peru, 2020); licensed hydrocarbon blocks January 2019 (Instituto Geológico Minero y Metalúrgico); indigenous territories (Instituto del Bien Comun (IBC), 2020).

Natural gas extraction in Camisea occurs in a highly diverse fabric of cultural, political, legal, and environmental conditions that have evolved over time. Even when Peru was shaken by civil war and terror, authoritarian and democratic regime shifts, and socio-environmental conflicts, Camisea continued, remarkably unchanged, through more than thirty years of history. Throughout these, Peruvian legislation and institutional arrangements have repeatedly adapted to local, national, and international tensions around Camisea.

Internationally and nationally, the project has been lauded as a cleaner and sustainable energy to support the development of the country. However, it was the coalition of indigenous communities and organizations—which was required to approve and support the project strategy for the development of the country—that demanded better environmental and social standards (Sarasara, 2003; Ross, 2009). Among these, Camisea’s benefit distributions have been contested by indigenous groups for decades. Since the discovery of the gas fields in 1980 s by the Royal Dutch Shell Company, Camisea’s gas extraction was driven by centralist and nationalist pressures that opposed local benefits. Moreover, Camisea gas has always been operated by foreign private hydrocarbon companies that not only send the gas to the main cities along the Peruvian coast, but also as liquid natural gas exports to Mexico, Japan, Spain, and other countries, making Peru one of the main LNG exporters in Latin America (Bridge and Bradshaw, 2017; Bryan, 2019).

For decades, Camisea’s indigenous groups have navigated between being viewed as environmentally conscious “noble savages” requiring external support and as their own respectable political agents during project negotiations, as they have to demonstrate negatives effect of Camisea’s social and environmental practices. The Lower Urubamba Valley has been called one of the last pristine tropical rainforests in South America (Alonso et al., 2001; Caffrey, 2002). The forest is home to 25 indigenous communities and territorial reserves for indigenous groups in voluntary isolation (Nahua, Nanti, and Kugapakori Territorial Reserve). At the local level in Camisea’s Lower Urubamba Valley, an underrepresentation of indigenous benefits and interests has continually been contested. “It was only when the gas comes that Cusco looks down and remembers that it has Amazonian jungle.” (interview with a local indigenous representative, 2018).

When COVID-19 started spreading in Latin America, the Amazon region quickly became an area of particular concern due to notoriously deficient health-care infrastructure, suspected indigenous vulnerability to falling severely ill from the novel coronavirus, and widespread concern about possible implications for the cultural survival of Amazon indigenous groups. The pandemic was rightly feared to exacerbate the region’s dire underlying situation that had developed over centuries: colonial marginalization, exploitation, and neglect; and, in the Upper Amazon, massive hydrocarbon extraction growth that consistently prioritized national revenues over the well-being and livelihoods of local people.

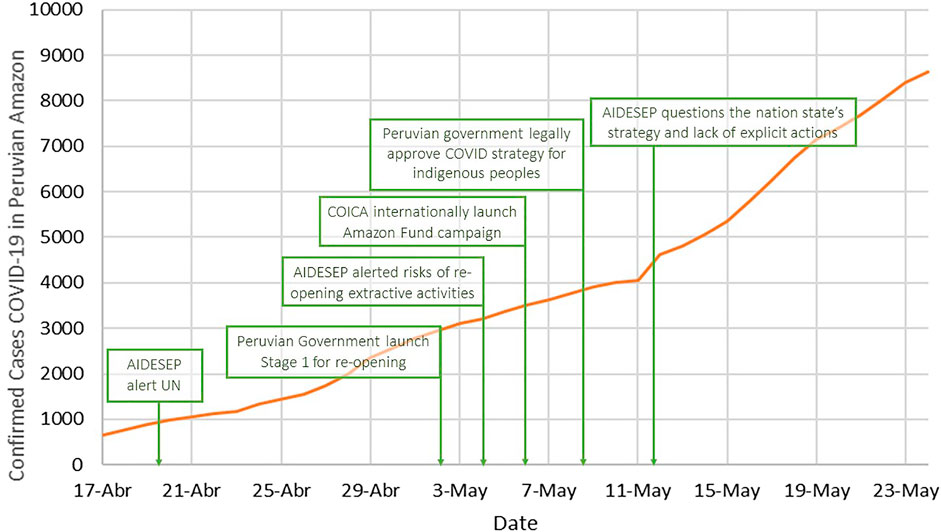

As before, it soon became apparent that the Peruvian government’s COVID-19 response offered no more care or attention to the Amazon than staying focused on the region’s resource extraction (see Figure 3). Announcing its national lockdown on March 15, 2020, the government had laid out its national COVID-19 pandemic protection strategy, addressing in detail the planned rules and protective measures for urban populations, their workers, and companies. More than a month later, still no feasible Amazon strategy had followed. On April 20, 2020, Peru’s Amazon’s indigenous organization AIDESEP (Inter-Ethnic Association for the Development of the Peruvian Forest) issued an open letter to the United Nations and international community to warn of insufficient Amazonian pandemic care planning as a result of political indifference of their national governments toward the health and survival of Indigenous Amazonians (Asociación Interétnica de Desarrollo de la Selva Peruana (AIDESEP), 2020a; Asociación Interétnica de Desarrollo de la Selva Peruana (AIDESEP), 2020b; Asociación Interétnica de Desarrollo de la Selva Peruana (AIDESEP), 2020c). They reminded that the government should not regard urban centers as their only policy directive, but that the state must rather protect all its citizens and not forget the country’s diverse situations related to cultures and livelihoods.

FIGURE 3. Timeline of COVID-19 events and resource extraction–related events in the Peruvian Amazon. Sources: Own elaboration using data from Confirmed COVID-19 cases in Peruvian Amazon (Centro Amazónico de Antropología y Aplicación Práctica (CAAAP), 2020a).

Regional reports soon indicated a significant lack of local information about the risks and prevention of COVID-19 infections across the Amazon, exacerbating the health situation. Testing proved not only difficult to access and implement among Amazon communities but also simply impossible for indigenous peoples living remotely or voluntarily isolated. Indigenous organizations in Peru started to investigate and report indigenous cases in the absence of official information (Gestion, 2020). Using data from the closest jurisdictions in the Peruvian Amazon Basin, by May 25, the Centro Amazónico de Antropología y Aplicación Práctica (CAAP) had reported 11,026 confirmed coronavirus cases and 477 deaths (Centro Amazónico de Antropología y Aplicación Práctica (CAAAP), 2020a). Actual numbers of infections and fatalities may have been much higher as testing remained limited.

The Amazon region soon saw rising numbers of infections and deaths, paired with growing protest with blockades and international pleas. Nonetheless, the Peruvian government pushed its national resource extraction frontier approach and, on May 2, 2020, announced the reopening of 27 economic activities as part of Stage 1 of its national economic recovery plan (Diario Oficial El Peruano, 2020a). This included eight natural resource industries declared as essential for the economy (e.g., hydrocarbon, forestry, oil palm, and cocoa plantations), which typically operate far away from high-density populated areas and the public eye. These industries were even reapproved to enter and operate with external workers in their licensed blocks within Amazon indigenous territories and without further control measures, despite rising infection risks for local people. Allowing these workers to travel long distances and enter sensitive zones with local populations was in stark contrast to the strict pandemic lockdown that the national government had announced on March 15, 2020, mandating a national “stay at home” order based on a strict isolation logic.

Amazonian indigenous organizations and communities raised their voices for more visibility, and inclusion in Peru’s emergency strategies and post-pandemic recovery plan in their territories. AIDESEP (Inter-Ethnic Association for the Development of the Peruvian Forest) warned of a “new ethnocide” (Asociación Interétnica de Desarrollo de la Selva Peruana (AIDESEP), 2020b) as a result of the lack of Amazon indigenous inclusion in the national government’s economic recovery strategy, in a letter dated May 4, 2020 (Asociación Interétnica de Desarrollo de la Selva Peruana (AIDESEP), 2020a), by May 6, COVID-19 concern in the Amazon had grown and the Coordinator of Indigenous Organizations of the Amazon Basin (COICA) scaled up regional campaigns to avoid environmental and cultural devastation (Amazon Emergency Fund, 2020; Amazon Watch, 2020; Reuters, 2020).

In response to rising Amazon concern and protest amid the pandemic, on May 9, 2020, the Peruvian government introduced a legislative decree that announces as its first listed point (health response) coordinated preventative measures against the spread of infection in Amazon indigenous communities, broadly criticized as much too little much too late (Servindi 2020a; Asociación Interétnica de Desarrollo de la Selva Peruana (AIDESEP), 2020c).

Interestingly, the same decree further established that the national police and military force were given full territorial control authority with respect to “control and supervision over river and terrestrial transit in areas where indigenous and native people live, so as to prevent the influx of people and goods that pose risks to these people” (own translation; Diario Oficial El Peruano, 2020b).

The Peruvian Amazon’s culturally diverse indigenous groups have survived throughout a long history of exploitation and marginalization. Referring to the locals as “little savages” (P. José Alvarez Fernández, O.P., 1936 cited by Soria et al., 1998), indigenous peoples were early portrayed as free labor for the extraction of diverse forestry resources such as rubber. Through slave-capturing raids called correrías, indigenous groups were not only robbed of their lands and livelihoods but also of their freedom and families, forced to work in rubber extraction, and later in coffee and cocoa haciendas or logging extraction (Pío Aza, 1919; Zarzar and Mora., 1997; Ludescher, 2001; Smith, 2005; Álvarez Lobo, 2009; Aparicio and Bodmer, 2009).

Despite the agrarian reform and land titling process in the 1980 s, indigenous communities in Megantoni were continuously confronted with new land zoning that diminished the recognition of their territorial rights, including the creation of protected areas (Shepard et al., 2010) and hydrocarbon blocks. Moreover, they had to defend their Amazonian ethnic distinction in contrast to Andean notions of indigenous peasants to prevent expansion of the agrarian frontier into their forests, driven by the Andean district they used to belong (interview with NGO representative and indigenous peoples, 2018).

After decades of indigenous collective efforts, in 2016, Megantoni received national government approval for the creation of their own formal district. It had taken the communities’ years of litigation, communal organization efforts, and investment of their resources to achieve district status and more authority over the region’s extractive management. Indigenous resistance in Camisea involves social and ideological contestations of the space and privileges related to knowledge, governance, and territorial control.

Although Camisea’s operations have internationally and nationally been praised as Peru’s most important and award-winning energy project with environmental best practices, they have not been able to improve local living conditions. Despite more than 15 years of extraction and tremendous revenues, indigenous people in Megantoni still live with limited electricity supply, insufficient public sanitation, and drinking water systems as well as higher occurrences rates of chronic child malnutrition (Red de Servicios de Salud la Convención, 2019). Even though they created their own district, they are still restricted by centralist revenue distribution laws that prohibit more local benefits from the hydrocarbon extraction, not least with respect to basic citizen rights related to health and well-being (Ojo Público Periodismo de Investigación, 2019; TV Peru Noticias National Television, 2019; Watson and Davidsen 2020a).

In short, Megantoni is known by some as a very dynamic and monetarily richest district in the country due to its revenues from hydrocarbon extraction, but with weak access to social services and access control. Camisea’s corporate social responsibility strategy introduced financial compensation agreements and local employment for local communities that have shown contradictory results over the years. The young territorial government of Megantoni is struggling to counteract state failures and changing national policies that affect citizen participation and local livelihoods in its territory.

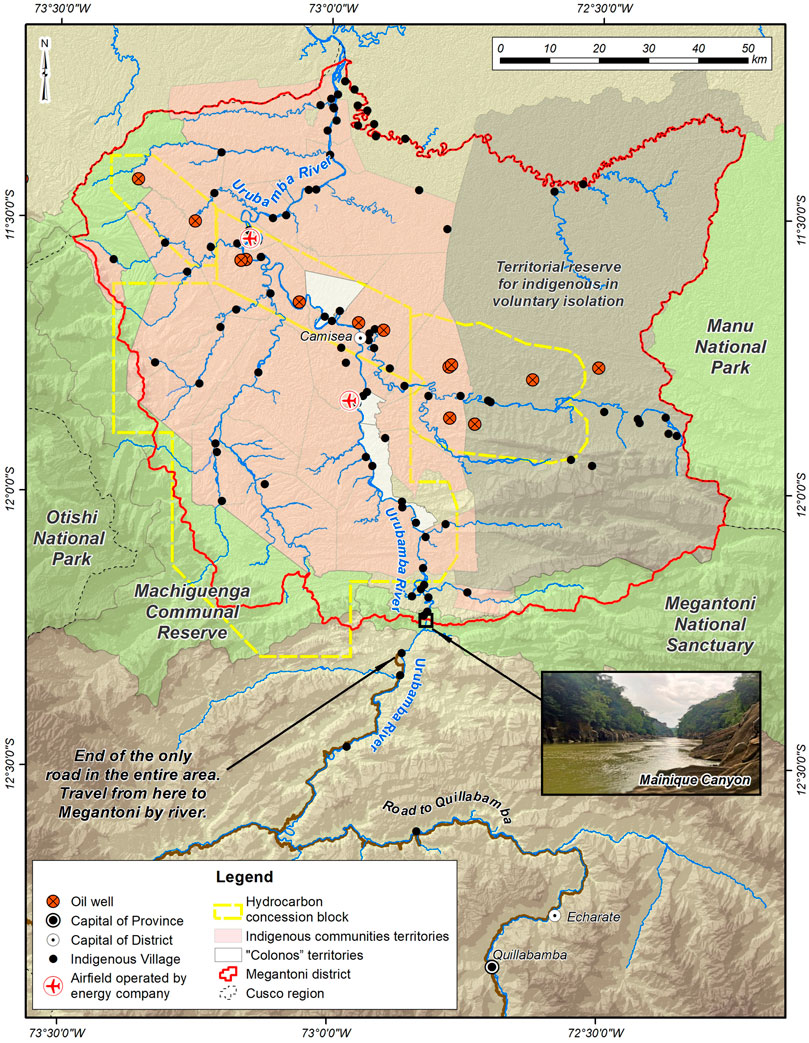

To protect the ecological integrity of the Amazon rainforest and avoid industrial footprints in the region, Camisea’s hydrocarbon operations use offshore inland extraction techniques that intentionally leave the area void of roads and infrastructure. This model has also been called enclave extraction, strategically employed to protect extraction operations in Africa from interruptions during internal conflict and civil war (Ferguson, 2006), or from the opposition of local communities (Appel, 2012). In contrast, in Camisea, the offshore inland model was announced as an environmentally led approach in roadless rainforest terrain and oil wells in close proximity to local indigenous villages, after local communities had communicated to the planning company Shell that they wanted to protect their territories from foreigners. Even after growing production in the 2000 s, the model remained in place as the result of environmental and indigenous activism that required this as a condition for their local support. Their objective was to avoid environmental and social impacts such as growing immigration settlements that typically accompanied other Amazon projects. As numerous indigenous interviewees summarized, it was “to protect us from the invasion” (Interview with indigenous communities, 2018).

In Camisea, all transport is exclusively done via rivers or air. No roads are linking these communities with nearby cities or to the outside world. The Urubamba River, a fast-flowing river with rapids and coarse wooden debris, provides the main connection between communities, settlements, and provincial hubs in the region, but travel on the river is difficult and dangerous due to dramatic surges during the rainy season. The only aerial transport from the Lower Urubamba to Lima is through the hydrocarbon companies. They have private aircraft and airfields for their exclusive corporate use. Under the cloak of conservation goals, territorial access has therefore become an issue of inequality in the Lower Urubamba, and relevant for critical health care.

The lack of medical facilities and health-related standards has long been a much-lamented issue in Megantoni. When the local population needs medical services beyond the basic care that the hydrocarbon company camps and postas médicas in select indigenous communities provide (Municipalidad Distrital de Megantoni, 2018), they have to make their way to the next hospital in Cusco city, at least one day of travel away, and during the rainy season (December to April) at times impossible. Local people in Megantoni have difficulties to access medical services outside their district, but energy company workers routinely enter their territories and, as COVID-19 emerged in 2020, created significant concern over an uncontrolled increase of infection risk.

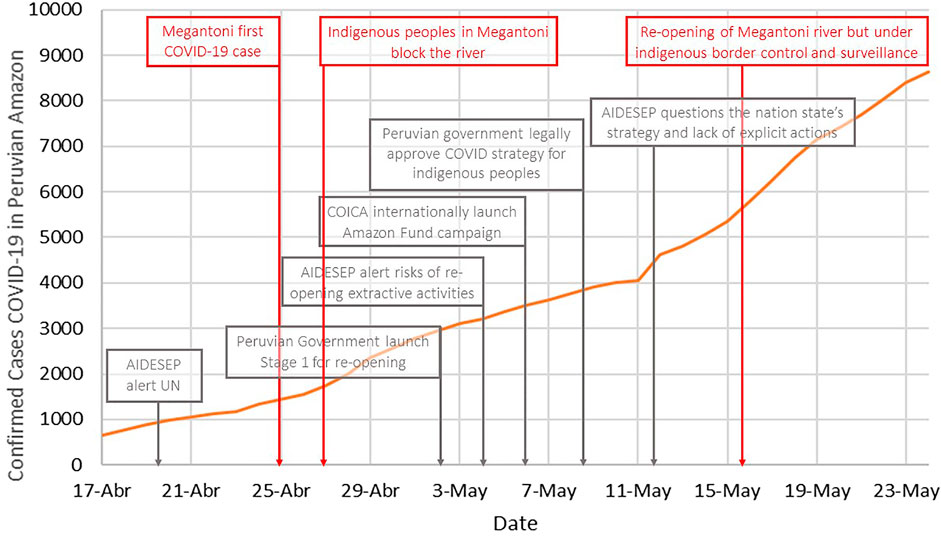

Peru’s national COVID-19 crisis response created new frustrations and momentum to challenge the status quo of territorial control in Megantoni (see Figure 4). Several weeks into the pandemic, on April 5, 2020, Megantoni’s mayor Daniel Ríos issued an urgent plea to state leaders in an interview with the large Peruvian news service Canal N. He called on the state to protect them, and to finally allow Megantoni to use their own district funding to build a hospital, as they had already requested for years (Municipalidad Distrital de Megatoni, 2020b). Although Megantoni’s former community leader and now mayor insisted on concrete measures to help the urgent health crisis in the communities, the interviewer in Lima brushed it off: “This is not the time to talk about whether a mayor can manage money like that” (own translation; Municipalidad Distrital de Megantoni, 2020c, min 7:22). The district would have had long sufficient municipal funds from its local gas extraction royalties, but the district mayor’s office lacks formal budget authority to approve and build a new hospital (Watson and Davidsen, 2020b).

FIGURE 4. Timeline of COVID-19 events in Megantoni. Sources: Own elaboration using data from Confirmed COVID-19 cases in Peruvian Amazon (CAAAP 2020a).

After no response, on April 24, Megantoni’s mayor announced in the main Peruvian newspaper El Comercio that they would close the district border because the national government had abandoned them. He argued that government plans did not consider the everyday realities of Amazon’s indigenous communities that show vast differences to those of Peru’s main urban centers along the coast and the Andes. He criticized the lack of decentralized emergency authority during such unprecedented times that require quick and local decisions (El Comercio, 2020a).

A day later, on April 25, the first case of COVID-19 was confirmed in Megantoni. It was a worker of the Spanish hydrocarbon company REPSOL who was evacuated by air to Lima by the company (Repsol 2020; Centro Amazónico de Antropología y Aplicación Práctica (CAAAP), 2020b). Local infection numbers were developing and uncertain, but reports from other parts of the Amazon accumulated to a wave of concern with respect to the regional health care infrastructure, lack of planning, and cultural respect by the national government, and, in short, lack of political interest in the region for its people and not just the extractive frontier.

Being concerned about the dire health situation in the area with understaffed medical services, and after the first formally confirmed COVID-19 case in their territories, on April 27, 2020, several indigenous communities in Megantoni self-organized to block the key access point to the entire Lower Urubamba Valley. All it took was to span a rope across the river at Pongo de Mainique (Mainique canyon), but it required collective agreement of the neighboring communities in the district, and highly effectively prevented any boat traffic across (El Comercio, 2020b).

The geographic characteristics of the Pongo highlight both practical as well as cultural territorial boundaries and power over the region in a fascinating way. The Pongo de Mainique is a 3-km stretch of river rapids through a narrow canyon, only manageable by the most skilled boat guides, and has become known as one of South America’s most dangerous and challenging navigable river passages. Surrounded by dozens of waterfalls and giant walls of vertical rock, this area is one of the most biodiverse spots of the planet, and it has remained relatively isolated due to the challenges it poses. The Pongo sits as a bottleneck between the Andes on its upper section, and the Amazon Lower Urubamba Valley on its lower section (see Figure 5). Without any roads in this geographical border area between highland and rainforest, and surrounded by several protected rainforest areas, there are no other land- or water-based ways in or out. The Lower Urubamba Amazon’s rainforest basin remains sparsely populated with small indigenous Amazonian communities, distinctly separated from the neighboring Andean highlands with their well-connected and more densely populated peasant communities.

FIGURE 5. Megantoni territorial access control in Lower Urubamba, with the strategic and spiritual point of Pongo de Mainique highlighted (bottom right).

The Pongo’s unique characteristics are also reflected in symbolic and spiritual meanings. The word Pongo stems from the Quechua word Puncu that means door. Literature and field research further highlight spiritual symbolism of the Pongo de Mainique associated with the beginning of the times, their lives, and protection from foreigners (Servicio Nacional de Areas Naturales Protegidas Servicio Nacional de Areas Naturales Protegidas (SERNANP), 2007; Snell et al., 2011). During field research, various participants also used the term pongo for a more generic meaning of a natural barrier, for example, to distinguish between other river sections. They also use the term to refer to cultural differences and tensions between Amazonian rainforest’s people on one hand, and Andean indigenous descents from the Incas on the other hand.

The simple act of blocking off the Pongo with a rope, organized by the leaders of six indigenous communities and rural settlements in the region (Kitaparay, Saringabeni, Sababantiari, Timpia, Kuway, and Chocoriari), essentially took over de facto territorial control of the entire Lower Urubamba, and implemented a territorial isolation from the outside. Countering the national government’s orders with this territorial control counteraction at the Pongo de Mainique epitomizes their strained relationship—and limited patience—of Amazonians with the Peruvian state, prompted by the extraordinary circumstances of COVID-19 that amplified already existing frustration over inequalities, exploitation, and neglect.

Peruvian laws usually penalize blockades, especially in defined critical areas such as those related to resource extraction. The community leaders, however, declared the blockade of the Urubamba River as an act of emergency self-defense in response to an absent state (El Comercio, 2020b; Municipalidad Distrital de Megantoni, 2020b; Servindi, 2020b), implying that the state norms would no longer apply when the state was not present. The emergency self-defense was described as their only alternative to protect themselves from the spread of infection over their territories, as their declaration preamble explains as follows:

“We appeal to the entire public opinion and to the central government authorities to deal with this situation because we find ourselves abandoned and we have not been listed no, nor do the institutions of the district, region, and the companies want to hear us. Confident to be cared for and understood, we the undersigned take on the commitment to take care of our communities especially with respect to prevention.” (Comite de Gestion para el Desarrollo Sostenible de la Cuenca del Bajo 2020:3)

As the indigenous community leader of Tangoshiari commented frankly, in a way, their need for self-defense arguably long precedes the arrival of COVID-19: “We feel like indigenous beggars sitting on a gold bench. Sad reality for us. We have been in a state of emergency for several years” (Comunidad Nativa de Tangoshiari, 2020). Public statements of the blockade pointed out the lack of capacity and the state failure to control and protect indigenous communities, but not against hydrocarbon operations. The de facto strategy of taking the Pongo reiterates their claim to expand their local authority as well as demonstrate the articulation of their traditional social organization at the interplay of their district authority.

In Megantoni, the district communities and central mayor launched their own surveillance system and COVID-19 command control before reopening the Pongo. The district representatives of Megantoni embarked on several days of discussions with the indigenous community leaders to decide how to proceed and where to install future checkpoints. In contrast with the former municipality regime, the embedded coordination and participation of indigenous leaders in Megantoni plays an important role. During our field data collection, local communities remarked how important it is that the municipality must respect all community leaders and continuously coordinate activities with them to thrive. Finally, during the third week of May, Megantoni’s major, indigenous leaders, and communities agreed to reopen the Pongo, but upheld strict control of river access through newly installed checkpoints.

The peaceful blockade of the Pongo was widely covered across Peruvian national media, prompting calls for more authority over resource access and locally concerted actions as broad and standardized measures, particularly where nationally mandated actions are unable to meet the needs of this diverse country. After the local communities had started the Pongo blockade, the national government announced further controversial relaxations of mobility restrictions for those industries considered of so-called national interest, including mining and hydrocarbon. This led to further concern across Amazonian indigenous territories and demands for indigenous participation in the decision-making of the COVID-19 strategies for their territories and provided even more background support for Megantoni’s blockage of the Pongo.

In response to continuous complaints by local authorities that they were unable to respond to the COVID-19 crisis in their jurisdictions, the national government passed an urgent decree (DU 081–2020) on July 5th, 2020, that grants local municipalities new rights to use their local resource extraction revenues to build and provide emergency services (Diario Oficial El Peruano, 2020c). However, this new measure does not respond to, or even acknowledge, the larger indigenous argument that the Pongo blockage had illustrated as a call for more political inclusion and territorial control, especially as prompted here by state failures. Instead, the government decree appeases by simplifying self-governance and greater authority over local budget roles, but ironically in a way that reinforces local governance dependence on resource extraction with its revenues and industries.

The presented Megantoni case highlights territorial conflicts in Amazonia as a “political space” (Massey, 2005; McCarthy, 2005; MacKinnon, 2011; Dietz, 2018; Vela-Almeida et al., 2018) as power relationships between the national state and indigenous communities are redefined, while extractive operations become competitively legitimized and delegitimized. Drawing on the concepts of governmentality and self-determination, we shed light on how power can be exercised from indigenous communities in a conservative neoliberal Peruvian context. In Camisea, indigenous communities have employed tactics of engaging with extraction in trying to advance the consolidation of their lands and achieve a greater autonomy from the national and local state that has continuously marginalized them; however, the sanitary emergency exposed that de jure collective action was not enough to secure their rights and interests. While trying to prevent the infection, they also called for their rights to control their lands, and challenge institutional and government frameworks to gain more participation in extraction decision-making.

In this case study analysis, territorial and access control (material and symbolic) are explored as a dynamic contestation of subjectivities imposed from above, while simultaneously creating new subjectivities from below. Interestingly, in the latter, the state has also been a result, through the creation of a separate district. Camisea was established as a small-footprint roadless sustainable project in the Lower Urubamba. Corporate access and control in the region were based on narratives of reconciled conservation and “offshore inland” technology, which fed into a more progressive approach and support for extractivism.

Camisea’s decades of growth have been placing local indigenous peoples into a two-sided experience. On the one hand, this local extraction invasion constantly reminds locals of the regions’ historical marginalization and fragmentation. At the same time, Camisea has opened new opportunities for them to renegotiate their political voice more effectively within the system, and helped change their narrative from that of marginalized victims to powerful political actors. Megantoni’s local communities have become highly engaged in compensation agreements and negotiations with extractive companies, and they have developed a fluid and intertwined set of de jure and de facto tactics to counteract national state rationalities.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Camisea’s influential standing and remote technology helped buttress the state’s extractive project and profit in the region. Paired with increasing national state neglect of health case for indigenous Amazonians, it resulted in prioritized resource extraction over “a few others” that can be left to die. A few weeks after the onset of the pandemic had caused increasing concern in the region, on April 27, 2020, the local indigenous population organized a physical and symbolic act of territorial resistance to protect their life and territory: they closed the Pongo de Mainique, the river canyon that constitutes the only land/water access into the Lower Urubamba Valley, as well as a spiritual and ecological landmark of the region.

In the context of this analysis’ explored political strategy and agency, it is particularly interesting that the Pongo blockade that they chose cut off public access for outsiders and merchants from the Upper Andes, but not from the transnational companies that were already operating in the area. The offshore design of the hydrocarbon extraction still gave the companies full control over their operations and concession block via airstrips and pipelines. In contrast to other indigenous communities in the northern Peruvian Amazon that entered and occupied oil camps to make their claims heard by the government, Megantoni chose to close the Pongo instead of taking over the local facilities of the most important energy project of the country.

This highlights their interesting positioning and hybrid resistance strategy that aims to challenge the state from within the same system that feeds their economic and political power, creating a dilemma for the local population. In trying to expand Megantoni’s land and resource rights through district status and toward greater access to gas rents, the district seems to accept and strengthen the state, the extractive project, and the national economic agenda, and in turn becoming more dependent on all three. As such, Camisea’s extractive project jeopardizes local indigenous interests through getting caught in the power hierarchies of the different imaginaries, while the latter may mute their original call for rights and reframe them within the dominant discourses and top-down institutional reforms.

By shifting indigenous narratives from one of victims to active political agents, Megantoni adds new insights into new local indigenous movements and indigenous political agency that are creating alternatives within, outside, or alongside the system to challenge the legitimacy of nation states, elites, and self-determination rights, formerly grounded on the coloniality of extractive power.

Apart from the collected field interviews, publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. These data can be found at Plataforma Nacional de Datos Abiertos. Accessed May 29, 2020. https://www.datosabiertos.gob.pe/dataset/casos-positivos-por-covid-19-ministerio-de-salud-minsa.

AW conducted the primary field data collection. AW and CD contributed to the design and implementation of the research, to the analysis of the results, and to the writing of the article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Ahlborg, Helene., and Nightingale, Andrea. J. (2018). Theorizing Power in Political Ecology: The where of Power in Resource Governance Projects. J. Polit. Ecol. 25 (1), 381–401. doi:10.2458/v25i1.22804

Allen, John. (2003). Lost Geographies of Power. Oxford: Blackwell. doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t071955

Allen, John. (2004). The Whereabouts of Power: Politics, Government and Space. Geografiska Annaler, Ser. B: Hum. Geogr. doi:10.1111/j.0435-3684.2004.00151.x

Alonso, Leeanne. E., Alonso, Alfonso., Schulenberg, Thomas. S., and Dallmeier, Francisco. (2001). Rapid Assessment Program Smithsonian Institution/Monitoring and Assessment of Biodiversity Program Biological and Social Assessments of the Cordillera de Vilcabamba, Peru. Washington: Conservation International.

Amazon Emergency Fund (2020). Supporting Amazon Forest Guardians. Available at: https://www.amazonemergencyfund.org/. (Accessed July 28, 2020).

Amazon Watch (2020). COVID-19: Inaction and Lack of Funds Threatens over Three Million Indigenous People in the Amazon. Available at: https://amazonwatch.org/news/2020/0506-covid-19-inaction-and-lack-of-funds-threatens-over-3-million-indigenous-people-in-the-amazon. (Accessed July 28, 2020).

Anaya, S. J. (1996). Indigenous Peoples in International Law. New York: Oxford University Press. Contemporary International Norms.

Andreucci, D., and Kallis, G. (2017). Governmentality, Development and the Violence of Natural Resource Extraction in Peru. Ecol. Econ. 134, 95–103. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.01.003

Anthias, P. (2018). Indigenous Peoples and the New Extraction: From Territorial Rights to Hydrocarbon Citizenship in the Bolivian Chaco. Latin Am. Perspect. 45 (5), 136–153. doi:10.1177/0094582X16678804

Anthias, P. (2019). Rethinking Territory and Property in Indigenous Land Claims. Geoforum. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.09.008

Aparicio, P. M., and Bodmer, R. (2009). Pueblos indígenas de la amazonía peruana. Iquitos: Centro Teológico de la Amazonía (CETA).

Appel, H. (2012). Offshore Work: Oil, Modularity, and the How of Capitalism in Equatorial Guinea. Am. Ethnol. 39 (4), 692–709. doi:10.1111/j.1548-1425.2012.01389.x

Arce, M. (2014). Resource Extraction and Protest in Peru. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt9qh8z9

Asociación Interétnica de Desarrollo de la Selva Peruana (AIDESEP) (2020a). Carta Abierta. Acciones de Emergencia En La Amazonía Indígena (DS 080-2020-PCM). Available at: http://www.aidesep.org.pe/sites/default/files/media/noticia/v2 Carta gobierno 3.5.20.pdf.

Asociación Interétnica de Desarrollo de la Selva Peruana (AIDESEP) (2020b). Denuncia Al Estado Del Perú Ante El Sistema Internacional de Protección de Los Derechos Humanos. Available at: http://www.aidesep.org.pe/sites/default/files/media/noticia/Denuncia AIDESEP ante la ONU.pdf. (Accessed May 28, 2020).

Asociación Interétnica de Desarrollo de la Selva Peruana (AIDESEP) (2020c). Pronunciamiento DL 1489. Voluntad Política de Urgencia No Peloteo Burocrático. Available at: http://www.aidesep.org.pe/noticias/pronunciamiento-que-la-accion-llegue-al-rio. (Accessed May 28, 2020).

Bebbington, A., and Humphreys Bebbington, Denise. (2009). Actores y ambientalismos: conflictos socio-ambientales en Perú. Íconos 35, 117–128. doi:10.17141/iconos.35.2009.371

Bebbington, A., and Humphreys Bebbington, Denise. (2011). An Andean Avatar: Post-Neoliberal and Neoliberal Strategies for Securing the Unobtainable. New Polit. Economy 16 (1), 131–145. doi:10.1080/13563461003789803

Bebbington, A., and Humphreys Bebbington, Denise. (2012). Underground Political Ecologies: The Second Annual Lecture of the Cultural and Political Ecology Specialty Group of the Association of American Geographers. Geoforum 43, 1152–1162. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2012.05.011

Bebbington, A., Abdulai, A-G., Bebbington, D. H., Hinfelaar, M., and Sanborn, C. A. (2018). Governing Extractive Industries. Politics, Histories, Ideas. Oxford: Oxford University PressAvailable at: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.%0AEnquiries. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198820932.001.0001

Bland, G., and Chirinos, L. A. (2014). Democratization through Contention? Regional and Local Governance Conflict in Peru. Lat. Am. Polit. Soc. 56 (01), 73–97. doi:10.1111/j.1548-2456.2014.00223.x

Boyle, M. (2009). Oral History. Int. Encyclopedia Hum. Geogr. 8, 30–33. doi:10.1016/B978-008044910-4.00485-5

Bridge, G., and Bradshaw, M. (2017). Making a Global Gas Market: Territoriality and Production Networks in Liquefied Natural Gas. Econ. Geogr. 93 (3), 215–240. doi:10.1080/00130095.2017.1283212

Bryan, J. (2019). BP Statistical Review of World Energy. (Accessed March 12, 2021). doi:10.2307/3324639

Bryan, J. (2012). Rethinking Territory: Social Justice and Neoliberalism in Latin America's Territorial Turn. Geogr. Compass 6 (4), 215–226. doi:10.1111/j.1749-8198.2012.00480.x

Buu-Sao, D. (2020). Extractive Governmentality at Work: Native Appropriations of Oil Labor in the Amazon. Int. Political Sociol. 15, 63–82. doi:10.1093/ips/olaa019

Caffrey, P. B. (2002). An Independent Environmental and Social Assessment of the Camisea Gas Project - by: Patricia B. Caffrey. Available at: https://amazonwatch.org/news/2002/0401-an-independent-environmental-and-social-assessment-of-the-camisea-gas-project--by-patricia-b-caffrey. (Accessed April 2, 2020). doi:10.2210/pdb1meq/pdb

Centro Amazónico de Antropología y Aplicación Práctica (CAAAP) (2020a). Casos Confirmados de COVID-19 En La Amazonía Peruana. Available at: http://www.caaap.org.pe/website/2020/04/17/casos-confirmados-de-covid-19-en-la-amazonia/. (Accessed May 2, 2020).

Centro Amazónico de Antropología y Aplicación Práctica (CAAAP) (2020b). Repsol Confirma Positivo Por COVID-19: Trabajador Del Lote 57 Fue Evacuado. Available at: https://www.caaap.org.pe/website/2020/04/25/repsol-confirma-positivo-por-covid-19-trabajador-del-lote-57-fue-evacuado/. (Accessed May 2, 2020).

Comité de Operación Económica del Sistema Interconectado Nacional (COES-SINAC) (2019). Estadísticas Anuales de Operaciones. Estadistica Anual 2019. Available at: https://www.coes.org.pe/Portal/publicaciones/estadisticas/estadistica2019#. (Accessed March 12, 2021).

Comunidad Nativa de Tangoshiari (2020). Pronunciamiento de La Comunidad de Tangoshiari. Available at: http://www.caaap.org.pe/website/2020/05/16/ashaninkas-y-matsigenkas-de-megantoni-denuncian-no-tener-mascarillas-ni-medicamentos/. (Accessed May 2, 2020).

Coombes, B., Johnson, J. T., and Howitt, R. (2012). Indigenous Geographies I. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 36 (6), 810–821. doi:10.1177/0309132511431410

Cornell, S. (2015). Processes of Native Nationhood: The Indigenous Politics of Self-Government. iipj 6 (4). doi:10.18584/iipj.2015.6.4.4

Crabtree, J., and Durand, F. (2017). Peru: Elite Power and Political Capture. London: Zed Books. doi:10.5040/9781350221758

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. London: Sage.

Defensoria del Pueblo Peru (2020). Prevención y Gestión de Conflictos Sociales en el Contexto de La Pandemia por El COVID-19. Serie Informes Especiales 026-2020. Available at: https://cdn.www.gob.pe/uploads/document/file/1058897/Informe-Especial-026-2020-DP-Prevencio%CC%81n-y-Gestio%CC%81n-de-conflictos-APCSG.pdf. (Accessed November 2, 2020).

Diario Oficial El Peruano (2020b). Legislative Decree 1489. Legislative Decree Establishing Actions for the Protection of Indigenous or Original Peoples in the Framework of Sanitary Emergency Declared by Covid-19. Lima, Peru: Gobierno del Peru.

Diario Oficial El Peruano (2020a). Supreme Decree 080-2020-PCMApproves the Resumption of Economic Activities Gradually and Progressively within the Framework of the Declaration of National Health Emergency Due to the Serious Circumstances that Affect the Life of the Nation as a Consequence of COVID-19. Lima, Peru: Gobierno del Peru.

Diario Oficial El Peruano (2020c). Urgent Decree 081-2020. To Enhance Investment and Services in Charge of the Regional Governments and Local Governments, and Other Measures in Face of the Health Emergency Produced by COVID-19. Lima, Peru: Gobierno del Peru.

Dietz, K. (2018). “Researching Inequalities from a Socio-Ecological Perspective,” in Global Entangled InequalitiesElizabeth Jelin, Renata Motta, and Sergio Costa, 76–92 (Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge).

Drinot, P. (2011). The Meaning of Alan García: Sovereignty and Governmentality in Neoliberal Peru. J. Latin Am. Cult. Stud. 20 (2), 179–195. doi:10.1080/13569325.2011.588514

Eaton, Kent. (2017). Territory and Ideology in Latin America. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198800576.001.0001

El Comercio (2020a). Coronavirus En Perú: Alcalde de Megantoni Pide Adecuar Plan de Salud a Realidad de Comunidades Nativas. Available at: https://elcomercio.pe/peru/cusco/coronavirus-en-peru-alcalde-de-megantoni-pide-adecuar-plan-de-salud-a-realidad-de-comunidades-nativas-cusco-noticia/?fbclid=IwAR0CfpK-dJKoWHZQK-CFVdofObfvvMWXZFP8722XFOWyIHJUCuK_N6fjq-s. (Accessed May 31, 2020).

El Comercio (2020b). Pobladores Bloquean Tránsito Fluvial Hacia Comunidades Nativas de Megantoni Por Temor Al COVID-19. Available at: https://elcomercio.pe/peru/cusco/pobladores-bloquean-transito-fluvial-hacia-comunidades-nativas-de-megantoni-por-temor-al-covid-19-noticia/?fbclid=IwAR0wz_VjJ4rrh1u6FZUnRpup966ryQQ64SFiFRuxqOmcayFYJ_t_ww6L4X4. (Accessed May 31, 2020).

Ferguson, J. (2006). Governing Extraction: New Spatializations of Order and Disorder in Neoliberal Africa. in Global Shadows: Africa in the Neoliberal World Order. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 194–210.

Finer, M., and Orta-Martínez, M. (2010). A Second Hydrocarbon Boom Threatens the Peruvian Amazon: Trends, Projections, and Policy Implications. Environ. Res. Lett. 5, 014012. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/5/1/014012

Fletcher, Robert. (2007). Introduction. in beyond Resistance: The Future Of Freedom. New York: Nova Science Publishers, 1–19.

Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five Misunderstandings about Case-Study Research. Qual. Inq. 12 (2), 219–245. doi:10.1177/1077800405284363

Fontaine, G. (2010). The Effects of Energy Co-governance in Peru. Energy Policy 38 (5), 2234–2244. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2009.12.011

Foucault, M. (1982). The Subject and Power. Crit. Inq. 8 (4), 777–795. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1343197. doi:10.1086/448181

Frederiksen, T., and Himley, M. (2020). Tactics of Dispossession: Access, Power, and Subjectivity at the Extractive Frontier. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 45 (1), 50–64. doi:10.1111/tran.12329

Gestion (2020). “Sin Datos Oficiales, Indígenas de Perú Hacen Su Recuento de Víctimas de COVID-19.” Lima. Available at: https://gestion.pe/peru/sin-datos-oficiales-indigenas-de-peru-hacen-su-recuento-de-victimas-de-covid-19-noticia/. (Accessed June 2, 2020).

Gonzales, T., and González, M. (2015). Introduction: Indigenous Peoples and Autonomy in Latin America. Latin Am. Caribbean Ethnic Stud. 10 (1), 1–9. doi:10.1080/17442222.2015.1034437

Gudynas, E. (2014). Sustentación, Aceptación y Legitimación de Los Extractivismos: Múltiples Expresiones pero un Mismo Basamento. Opera 14 (14), 137–159.

Gustafsson, M.-T., and Scurrah, M. (2019). Strengthening Subnational Institutions for Sustainable Development in Resource-Rich States: Decentralized Land-Use Planning in Peru. World Dev. 119, 133–144. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.03.002

Halvorsen, S., Fernandes, B. M., and Torres, F. V. (2019). Mobilizing Territory: Socioterritorial Movements in Comparative Perspective. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 109 (5), 1454–1470. doi:10.1080/24694452.2018.1549973

Hammersley, M. (2013). What Is Qualitative Research? London: Bloomsbury Academic. doi:10.5040/9781849666084

Hawkes, D. C. (2002). Indigenous Peoples: Self-Government and Intergovernmental Relations. Int. Soc. Sci. J. 53 (167), 153–161. doi:10.1111/1468-2451.00304

Hay, Iain. (2010). Qualitative Research Methods in Human Geography. Ontario: Oxford University Press.

Instituto del Bien Comun (Ibc) (2020). Mapa Comunidades Nativas. Available at: http://191.98.188.187/ibcmap. (Accessed June 2, 2020).

Instituto Geológico Minero y Metalúrgico. n.d. “Lote Petroleros Enero (2019). PERUPETRO.” INGEMMET - Datos Abiertos. Available at: http://data-ingemmet-peru.opendata.arcgis.com/datasets/1d2ce37feb2f4644b3772f3311f410b4_0. (Accessed May 29, 2020).

Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informatica (INEI) (2018). Perú: Crecimiento y Distribución de La Población Total 2017. Lima: INEI.

Inter-American Commision on Human Rights (2009). “Derechos de los Pueblos Indígenas y Tribales sobre sus Tierras Ancestrales y Recursos Naturales: Normas y Jurisprudencia del Sistema Interamericano de Derechos Humanos.” OEA documentos oficiales. Available at: https://www.oas.org/es/cidh/indigenas/docs/pdf/tierras-ancestrales.esp.pdf. (Accessed April 29, 2020).

Irarrazaval, F. (2020). Contesting Uneven Development: The Political Geography of Natural Gas Rents in Peru and Bolivia. Polit. Geogr. 79 (February), 102161. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2020.102161

Jackson, J. E., and Warren, K. B. (2005). INDIGENOUS MOVEMENTS IN LATIN AMERICA, 1992-2004: Controversies, Ironies, New Directions. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 34 (1), 549–573. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.34.081804.120529

Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center.(2021). “Mortality Analyses - Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center.” n.D. Available at: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/mortality. (Accessed January 4, 2021).

Kröger, M., and Lalander, R. (2016). Ethno-Territorial Rights and the Resource Extraction Boom in Latin America: Do Constitutions Matter? Third World Q. 37 (4), 682–702. doi:10.1080/01436597.2015.1127154

Ludescher, M. (2001). Instituciones Y Prácticas Coloniales En La Amazonía Peruana: Pasado Y Presente, Indiana. 17/18, 313–359. Available at: http://www.iai.spk-berlin.de/fileadmin/dokumentenbibliothek/Indiana/Indiana_17_18/14ludescher.pdf.

MacKinnon, D. (2011). Reconstructing Scale: Towards a New Scalar Politics. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 35 (1), 21–36. doi:10.1177/0309132510367841

McCarthy, J. (2005). Scale, Sovereignty, and Strategy in Environmental Governance. Antipode 37 (4), 731–753. doi:10.1111/j.0066-4812.2005.00523.x

McDonell, E. (2015). The Co-constitution of Neoliberalism, Extractive Industries, and Indigeneity: Anti-mining Protests in Puno, Peru. Extractive Industries Soc. 2 (1), 112–123. doi:10.1016/j.exis.2014.10.002

Merino, R. (2020). Rethinking Indigenous Politics: The Unnoticed Struggle for Self-Determination in Peru. Bull. Latin Am. Res. 39 (4), 513–528. doi:10.1111/blar.13022

Merino, R. (2015). The Politics of Extractive Governance: Indigenous Peoples and Socio-Environmental Conflicts. Extractive Industries Soc. 2 (1), 85–92. doi:10.1016/j.exis.2014.11.007

Ministerio de Energía y Minas Perú (2016). Libro anual de reservas de hidrocarburos al 31 de diciembre del 2015. MINEM Perú. Available at: http://www.minem.gob.pe/minem/archivos/Libro de Reservas 2015.pdf.

Ministerio de Salud Peru (2020). “Casos Positivos Por COVID-19 (Ministerio de Salud – MINSA). Plataforma Nacional de Datos Abiertos.” Plataforma Nacional de Datos Abiertos. Available at: https://www.datosabiertos.gob.pe/dataset/casos-positivos-por-covid-19-ministerio-de-salud-minsa. (Accessed May 29, 2020).

Municipalidad Distrital de Megantoni (2020a). Ceremonia de Entrega Parcial Del Campamento Contingencia Municipal de Megantoni En Camisea. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/815133875313215/videos/149946353535689.(Accessed December 23, 2020).

Municipalidad Distrital de Megantoni (2020b). Entrevista Del Alcalde Daniel Ríos a Canal N. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/815133875313215/videos/357204455184579. (Accessed May 29, 2020).

Municipalidad Distrital de Megantoni (2018). Plan de Desarrollo Local Concertado Megantoni Al 2030. Available at: http://www.munimegantoni.gob.pe/media/4232/pdlc-al-2030.pdf. (Accessed May 29, 2020).

Municipalidad Distrital de Megantoni (2020c). “Fuerzas Del Orden No Pudieron Disolver Bloqueo de Pobladores En La Entrada de Megantoni.” Radio Exitosa. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=662628964580156. (Accessed May 29, 2020).

OECD (2015). Competitiveness and Economic Diversification in Peru. in Multi-Dimensional Review of Peru, 99–136. Paris: OECD Publishing. doi:10.1787/9789264243279-8-en

Ojo Público Periodismo de Investigación (2019). Entrevista de Ojo-Publico.Com a Daniel Ríos, Primer Alcalde Electo Del Distrito de Megantoni. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6ua7wBe2rjk&ab_channel=OjoPúblicoPeriodismodeInvestigación. (Accessed April 15, 2020).

Orihuela, J. C., Pérez, C. A., and Huaroto, C. (2019). Do Fiscal Windfalls Increase Mining Conflicts? Not Always. Extractive Industries Soc. 6 (2), 313–318. doi:10.1016/j.exis.2018.07.010

Pacheco, P., Barry, D., Cronkleton, P., and Larson, A. (2012). The Recognition of Forest Rights in Latin America: Progress and Shortcomings of Forest Tenure Reforms. Soc. Nat. Resour. 25 (6), 556–571. doi:10.1080/08941920.2011.574314

Peirano, G. (2011). La Coherencia de la Política Ambiental Peruana: Las Implicancias del Proyecto Gasífero Camisea en la Creación del Ministerio Del Ambiente. Lima: Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú.

Petray, T., and Pendergrast, N. (2018). Challenging Power and Creating Alternatives: Integrationist, Anti-systemic and Non-hegemonic Approaches in Australian Social Movements. J. Sociol. 54 (4), 665–679. doi:10.1177/1440783318756513

Pío Aza, J. (1919). Un Documento Revelador 1916. San Luis del Manu, 30 abril 1916. Señor Subprefecto de La Provincia Del Manu. Misiones Dominicanas Del Perú 2, 37–48.

Presidencia del Consejo de Ministros - Viceministerio de Gobernanza Territorial (2019). Willaqniki. Comunicándonos Mejor para Conocernos Mejor. 01-2019. Lima: PCM.

Radcliffe, S. A. (2019). Geography and Indigeneity III: Co-articulation of Colonialism and Capitalism in Indigeneity's Economies. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 44 (2), 374–388. doi:10.1177/0309132519827387

Red Amazónica de información Socioambiental Georreferenciada (2012). “Amazonía Bajo Presión.” São Paulo: RAISG Red Amazónica de Información Socioambiental Georreferenciada. Available at: www.raisg.socioambiental.org. (Accessed April 15, 2019).

Red de Servicios de Salud la Convención (2019). Sistema de Información Estadística. Red de Servicios de Salud La Convención. Reporte 2015-2019: Anemia y Desnutrición por Microred. Available at: http://www.estadistica.redsaludlaconvencion.gob.pe/uploads/reporte_2019/. REPORTE 2015-2019 ANEMIA Y DESNUTRICION POR MICRORED.xlsx. (Accessed April 15, 2020).

Repsol (2020). “Repsol Comunicado de Prensa. 24 de Abril 2020.” Lima: Red de Salud La Convención. Available at: http://www.redsaludlaconvencion.gob.pe/Imagen/Publicidad Minsa 2020/marzo/Informacion de Interes.jpg. (Accessed May 15, 2020).

Reuters (2020). Amazon Indigenous Groups Launch International Fund to Fight Coronavirus. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-amazon-indigenous/amazon-indigenous-groups-launch-international-fund-to-fight-coronavirus-idUSKBN22I2WS. (Accessed May 25, 2020).

Ribot, J. C., and Peluso, N. L. (2009). A Theory of Access*. Rural Sociol. 68 (2), 153–181. doi:10.1111/j.1549-0831.2003.tb00133.x

Rice, R. (2012). The New Politics of Protest: Indigenous Mobilization in Latin America's Neoliberal Era. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Ross, C. (2009). “Case Study: Natural Gas Project in Peru,” in Globalizing Social Justice. The Role Of Non-govermental Organizations In Bringing About Social ChangeJeffrey Atkinson and Martin Scurrah, 133–65. (Hampshire: Palgrove Macmillan).

Sarasara, C. (2003). Manifiesto Publico. Declaracion de Los Pueblos Matsiguengas y Yine Del Bajo Urubamba y Bases de CONAP.

Servicio Nacional de Areas Naturales Protegidas (SERNANP) (2007). Plan Maestro Del Santuario Nacional Megantoni 2007-2011. Lima: SERNANP.

Servindi (2020a). Observaciones Críticas Al D.L. 1498 de Emergencia Para Pueblos Indígenas. Available at: https://www.servindi.org/actualidad-opinion/11/05/2020/observaciones-criticas-al-dl-1498-de-emergencia-para-pueblos-indigenas.(Accessed May 25, 2020).

Servindi (2020b). Tránsito Fluvial En El Bajo Urubamba Pone En Riesgo a Megantoni. Available at: https://www.servindi.org/21/04/2020/denuncian-transito-de-enbarcacionesbajo-en-el-urubamba. (Accessed May 31, 2020).

Shepard, G. H., Rummenhoeller, K., Ohl-Schacherer, J., and Yu, D. W. (2010). Trouble in Paradise: Indigenous Populations, Anthropological Policies, and Biodiversity Conservation in Manu National Park, Peru. J. Sust. For. 29 (2), 252–301. doi:10.1080/10549810903548153

Sidorova, E., and Rice., R. (2020). Being Indigenous in an Unlikely Place: Self-Determination in the Yakut Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (1920-1991). iipj 11 (3), 1–18. doi:10.18584/iipj.2020.11.3.8269

Smith, R. C. (2005). “Can David and Goliath Have a Happy Marriage? the Machiguenga People and the Camisea Project in the Peruvian Amazon,” in Communities and Conservation: Histories and Politics of Community-Based Natural Resource Management. Editors Brosius, P. J., Tsing, A. L., and Zerner, C. (California: AltaMira Press). Available at: http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ucalgary-ebooks/detail.action?docID=1343755. 231–67.

Snell, B., Chavez, I., Cruz, V., Collantes, A., and Epifanio Pereira, J. (2011). Diccionario Matsigenka - Castellano. Serie Lingüística Peruana N° 56. Mary Ruth Wise. Lima: Instituto Lingüístico de Verano.

Soria, H., and Manuel, J. (1998). Entre Tribus Amazónicas. La Aventura Misionera Del P. José Alvarez Fernández. Salamanca: San Esteban. 1890-1970.

Stake, R. E. (2003). “Case Study,” in Strategies Of Qualitative Inquiry. Editors N. K. Denzin, and Y. S. Lincoln (London: Sage).