- 1Department of Sociology and Social Research, University of Milano-Bicocca, Milan, Italy

- 2Department of Statistics and Quantitative Methods, University of Milano-Bicocca, Milan, Italy

In the international literature, the principal task of grandparents is generally recognized as helping their children in providing childcare. Most of those studies analyzed grandparental childcare on the whole population, and few have focused on co-resident grandparent(s), which turns out to be an understudied topic in the European context. Further, most of them investigated the effect of childcare on grandparents’ health status. However, the elderly population can both provide and receive care. Using two Italian surveys released by the Italian National Institute of Statistics, the “Social Condition and Integration of Foreign Citizen (2011–2012)” and the “Multiscopo–Aspetti della vita quotidiana (2011)”, the study aims to analyze differences in grandparental childcare provided by co-resident grandparents between Italian and migrant households, considering both the role played by grandparents’ self-rated health (SRH) and gender. We identify four grandparents’ profiles by combining grandparents’ SRH and their attitude towards looking after their grandchild(ren). Subsequently, we apply multinomial logistic regressions, and we compute average marginal effects to facilitate results interpretations. Results display that migrant co-resident grandparents are less likely to declare bad SRH and no-childcare and are more likely to declare good SRH and to provide childcare than Italian grandparents. Moreover, when considering gender differences, the real role is revealed: we find that women have a higher probability to report poor health and care for their grandchild(ren) than men. Such findings illustrate that grandparents’ cohabitation decision is based upon the difference between their need for care and offer to care, and second, in addition to migrant status and SRH, gender is a determinant of grandparents’ childcare: women look after their grandchild(ren) more than men, whatever their health status.

Introduction and Background

The decrease in fertility and the increase in life expectancy has significantly altered the age structure of the population. Many developed countries have experienced an increase in the average age of the population (where the over 65 years-olds prevail), known as aging populations. Longer life expectancy means that more children have the opportunity to live with their grandparent(s), although this trend might be counterbalanced by a delay in fertility, especially in those countries where this phenomenon is particularly pronounced (Tomassini and Wolf, 2000). However, it should be noted that demographic changes and socioeconomic shifts, also occurring in the last 3 decades, have modified the meaning of grandparenting.

In the literature, it is well established that grandparents play an important role in providing family support, in terms of emotional, financial, and practical care, specifically for both their child(ren) and their grandchild(ren) (Fuller-Thomson and Minkler, 2001; Hank and Buber, 2009; Aassve et al., 2012; Dunifon et al., 2014; Di Gessa et al., 2016a; Bordone et al., 2017). Their supporting role as childcare providers is even stronger in countries with lower levels of paid employment among older women, limited public childcare services, and more conservative attitudes toward gendered family roles, such as in Southern European countries (Igel and Szydlik, 2011; Jappens and Van Bavel, 2012; Di Gessa et al., 2016a).

Although a growing body of literature has investigated the involvement of grandparents in grandchild care (Hank and Buber, 2009; Aassve et al., 2012; Di Gessa et al., 2016a; Bordone et al., 2017; Glaser et al., 2018; Zamberletti et al., 2018), some topics have received little attention. According to Glaser et al. (2018), one of the main gaps in the literature is the analysis of trends in co-residence between grandparent(s) and grandchild(ren). Indeed, most of those studies are widely concentrated in the United States (Casper and Bryson, 1998; Goodman and Silverstein, 2002; Dunifon et al., 2014), which has experienced a relevant increase in the prevalence of multigenerational households since the 1970’s (Casper and Bryson, 1998; Taylor et al., 2010; Dunifon et al., 2014), in some cases associated with socio-economic disadvantage (Dunifon et al., 2014).

For Europe, studies on multigenerational households and on co-residence between grandparents and grandchildren are not as abundant as they are for the United States, also because of data quality (Glaser et al., 2018). Although in Western European countries intergenerational co-residence declined dramatically over the course of the 20th century, they are less common in Northern than in Southern and Eastern European countries (Palloni, 2000; Tomassini et al., 2004; Albuquerque, 2011; Selwyn and Nandy, 2014).

So far, the assumption has been that all grandparents are equally likely to be involved in grandparental childcare; however, previous studies have stressed the preponderance of women as care providers (Wall et al., 2001; Thomese and Liefbroers, 2013; Zamberletti et al., 2018). In Western cultures, women, and in particular grandmothers, are considered as kin keepers (Rosenthal, 1985; Hagestad, 1986; Friedman, et al., 2008; Sear and Mace, 2008).

Several studies have also examined the relationship between grandparental childcare and grandparents’ health in different countries, often yielding ambiguous results (Hank et al., 2018). Some of them suggest that grandparents who look after their grandchild(ren) occasionally are more likely to report better physical and psychological health than grandparents with intensive commitments or grandparents who do not provide childcare at all (Fuller-Thomson and Minkler, 2001; Minkler and Fuller-Thomson, 2001; Hank and Buber, 2009; Arpino and Bordone, 2014). These grandparents are also more likely to report positive effects or no major effects once other characteristics are taken into account (Hughes et al., 2007; Di Gessa et al., 2016b; Ates, 2017). Conversely, other studies have highlighted a negative relationship between grandparents’ childcare and health, for example depressive symptoms and worse self-rated health as well as physical health problems (Minkler et al., 1997; Lee et al., 2003; Blustein et al., 2004). With a particular focus on co-residing grandparents, some studies found that looking after grandchild(ren) may have negative consequences on grandparents’ health, who are more likely to experience health declines and to report depressive symptoms compared to those who provide lower levels of grandchild care or no grandchild care at all (Minkler et al., 1997; Blustein et al., 2004; Hughes et al., 2007; Chen and Liu, 2012).

More generally, some studies underline that the familial context of grandparental childcare is central to understanding the health implications and that the context of grandparenting (e.g., whether they are custodial or non-coresiding) may cause possible selection effects (Danielsbacka et al., 2019).

Di Gessa et al. (2016b), analyzing the longitudinal association between grandparental childcare and health in eleven European countries, and also taking into account individuals’ advantages or disadvantages throughout the life-course, found that looking after grandchildren affects the physical health of grandmothers and grandfathers differently: it appears to be beneficial for grandmothers who look after their grandchild(ren) intensively or non-intensively as opposed to those who do not provide any childcare, while this pattern result was not significant for grandfathers. Other studies also found gender differences in the effect of the provision of grandchild care, in particular on mental health, and attributed such a difference to the different roles, expectations, and desires which men and women have concerning care and family involvement (Blustein et al., 2004; Grundy et al., 2012). Grandmothers may perceive grandchild care and may experience and perform care differently from grandfathers, thus, childcare in turn may affect their health differently (Waldrop et al., 1999; Stelle et al., 2010).

In addition, other studies stress that providing care may have both positive and negative consequences on well-being (Walker et al., 1995; Pinquart and Sörensen, 2003; Stanca, 2012). Ruppanner and Bostean (2014) found that women report worse well-being than men in countries with greater attitudinal support for co-residential familial caregiving. Nevertheless, reciprocally, elderly dependents may provide help in the home for the caregiver’s family, especially when children are present (Ingersoll-Dayton et al., 2001).

Although the aforementioned studies investigated grandparents’ characteristics, gender differences in childcare, the effect of childcare on grandparents’ health, and (marginally) grandparental childcare in multifamily households in Europe, most childcare works focus on the overall population without considering migrant families as potential consumers of childcare (Williams and Gavanas, 2008).

During the last decades, migration flows have shifted and still continue to shift European societies into multicultural societies. As migrants settle in the destination countries, childcare emerges as a new exigency. The few studies available on migrants’ childcare preferences suggest that they use more informal than formal care (Ryan, 2007; Barglowski et al., 2015).

Studying the Italian case is interesting for multiple reasons. First, the Italian care regime has long been marked by the male breadwinner model, with a traditional gender division of work and family responsibilities (Mencarini and Solera, 2004), which generally conceives childcare as a female issue (Naldini and Saraceno, 2011). Second, Italy is characterized by a “familistic model” of care based on solidarity between generations, resulting in a lack of public services (Esping-Andersen, 1990). Accordingly, in Italy, where grandparents play a key role in informal childcare, being a migrant may constitute a further constraint.

“As a matter of fact, the implicit familialism with its weak direct support for the family’s caring function and its lack in service provision does not directly intervene in gender relations. It resembles a laissez-faire model of family policy where the state seeks to exercise no influence on the family at all. Nevertheless, this type affects gender relations since it simply reproduces and thus confirms the status quo of gendered care provision within the family” (cf. Harding 1995: 183–6).

The present study, using two Italian surveys carried out by the Italian Institute of Statistics (ISTAT) and comparing Italian and migrant families, sheds light on grandparental childcare in those households called “sandwich generation” families (Bryson and Casper 1999), which are a specific form of multigenerational family where there is at least one grandparent, his/her child(ren), and his/her grandchild(ren). To our knowledge no research is devoted to this particular kind of family as far as the Italian context is concerned.

The Italian Context

Italy is characterized by a “familistic” welfare model (Esping-Andersen, 1990), where the family are responsible for the wellbeing of members, and family policies (based on the three pillars: family allowances, parental leave, and care services) are still scarce, not universal, and not generous (Costa and Sabatinelli, 2011; Presidency of the Council of Ministers–Department of Family policies, 2020). In addition, some studies show that among the European countries, Italy is characterized by the strongest intergenerational exchange (Di Gessa et al., 2016a; Zamberletti et al., 2018; Santero and Naldini, 2020).

In Europe, although Italy appears to be the “oldest country”, it has the lowest percentages of grandparents (53%) compared to England, France, the Scandinavian countries, and Belgium (between 62 and 67%) (Glaser et al., 2013). Nonetheless, Italy is one of the countries where grandparents are more likely to provide a higher intensity and regular daily form of care. The share of grandparents looking after their grandchild(ren) at least once a week is 20% in Northern countries, around 30% in France, and 45% in Spain and Italy. In Southern European countries, more interesting is the share of grandparents who provide care on a daily basis: 30% in Italy and Spain compared to only 2% in the Northern countries (Arpino et al., 2010).

A recent study by Di Gessa et al. (2016a) found that grandparents are more likely to provide intensive childcare for working mothers in countries where women enter less frequently in the labor market, such as in Italy. This finding shows that the probability of grandparents being involved in intensive childcare not only depends on individual characteristics, but also on the needs of childcare and on country characteristics.

As already mentioned in the previous paragraph, the relationship between providers and users of care among the elderly is also influenced by gender. Zamberletti et al. (2018) found that gender is crucial for the probability of providing childcare: grandmothers are more than three times more likely to provide intensive childcare than grandfathers. However, even in this context, the inverse relationship between childcare provider and care recipient is evident; those in poor health are less likely to take care of grandchildren. Another study by Del Boca et al. (2005) found that the presence of a grandmother who lives nearby and in good health is determinant for the choice to shift from public to informal childcare, in particular for very young child(ren).

The structure of the Italian population has been modifying for some decades, in part due to the constant increase of both migration flows and migrant settlements (Bonifazi, 2017; ISTAT, 2018). The migrant population in its settlement process has formed (or reunited) and enlarged families with children’s birth and subsequently has shown a need for childcare (Barbiano di Belgiojoso and Terzera, 2018). Mostly migrants live together with their descendants (Terzera and Barbiano di Belgiojoso, 2019), indeed, the cohabitation of several generations is more frequent among foreigners than among Italians.

According to two national surveys conducted by ISTAT, in Italy, among the Italian households the share of multigenerational households (i.e., families with at least one parent and one co-resident grandparent) with children aged 0–13 is 7.5% (ISTAT, 2018)1, while among foreigners the percentage is higher (11.5%; ISTAT, 2018)2.

The Italian law establishes strict criteria for the reunification of parents and relatives other than partner/spouse and minor children: parents aged under 65 can be reunified only if they do not have other children who can look after them in their own country, while parents aged 65 and more can be reunified only if any other relatives can’t support them in the country of origin due to serious health problems (Article 23 L 189/02). Moreover, in 2008 the Legislative decree n. 160 added the request for private health insurance (or privately funded registration with the National Health System) as a requisite for the reunification of elderly aged 65 or above (Bonizzoni, 2015). These requisites limit the number of family reunifications for relatives other than partner/spouse and minor children. The rare reunification of parents or relatives, as well as the low share of first generations of immigrants already grandparents, reduce the family network compared to the conditions in their home country (Barbiano di Belgiojoso and Terzera, 2018) and compared to non-migrants.

Italy began to experience considerable immigration during the 80’s, thus the aging of the immigrant population is still a marginal phenomenon (Cela and Barbiano di Belgiojoso, 2019); actually, the share of elderly migrants is rather small and therefore little studied. However, older populations are increasing in relative and absolute numbers and in the future, elderly people (both natives and migrants) will play a more important role in their family and in society in general, as long as their life expectancy increases. Although family and society will have to care for some of the elderly population, at the same time, they will benefit from the help of others, as grandparents looking after grandchildren and supporting working mothers and fathers.

Our contribution to the literature is fourfold: first, while most of the studies on grandparental childcare focus on the whole population, we analyzed and compared grandparental childcare between Italian and migrant households. Second, we analyzed grandparental childcare provided by co-resident grandparent(s), which is an understudied topic in the European context focusing on a segment of the population with specific characteristics. Third, while several studies investigated the effect of childcare on grandparents’ health, we analyzed co-resident grandparents in Italian and migrant families to examine whether such cohabitation is related to health status, thus analyzing whether grandparents need care, or conversely, they represent a family support system in providing childcare. Fourth, besides grandparents’ characteristics, the household is used as the analysis unit, taking into account the role of the household composition, the mother’s employment status, and the perception of the economic condition of the household, while the majority of previous studies focused only on the relationship between grandparents’ childcare and mother’s participation in the labor market, neglecting the role of the household composition (Del Boca et al., 2005; Aassve et al., 2012; Arpino et al., 2014). Therefore, this study has three aims. First, it analyses and measures the differences in co-resident grandparents’ childcare between Italians and migrants. Subsequently, by considering grandparents’ self-rated health, it explores whether there are differences in co-resident grandparents’ role between the two populations; finally, it examines gender differences in grandparental childcare, by verifying whether they also persist within migrant families.

Data and Methods

We created a pooled dataset merging two different national surveys conducted by ISTAT. The first (and, so far, unique) survey is “Social Condition and Integration of Foreign Citizen” (hereafter SCIFC), collected during 2011–2012, which contains information on a sample of nearly 9,500 households with at least one foreign-born member. The second survey is “Multiscopo–Aspects of Daily Life” (hereafter AVQ), conducted during 2011, which contains information on almost 20,000 Italian households. In both surveys information about childcare were asked only to households with at least one child aged 13 or less, thus we restricted our sample to those families with at least one parent (4,085 households in the AVQ sample and 3,389 in the SCIF sample). In addition, from the SCIF survey we excluded mixed couples (i.e., with an Italian parent) and single-parent families with Italian children (around 32%), because the surveys do not include information on the latter as, being Italians, they did not meet the criterion for being in the target group (2,298 households in the SCIF sample). Since our study focuses on co-resident grandparents’ childcare in Italy, we further selected households with at least one co-resident grandparent (303 households in the AVQ and 219 in the SCIF survey). Finally, the study analyses the role played by grandparents’ self-perceived health, thus, among this sample we selected grandparents for whom health information is available. Hence, the final sample is composed of 517 families (302 Italians and 215 foreigners) for a total of 718 co-resident grandparents.

From the data, two possible caveats emerge. First, in the AVQ survey we do not consider naturalized families (i.e., those who have acquired Italian citizenship) because the sample does not provide this information. Second, as stated beforehand, for migrant households, the presence of grandparents is strictly limited by the law. However, as regards the naturalization issue, three considerations are needed here: on the one hand, in Italy the migration phenomenon is relatively recent, the real increase was around the end of the 1990’s and the beginning of the 2000’s. On the other hand, Italy’s citizenship policy (n. 91/1992) requires 10 years of residence for naturalization (Paparusso, 2019). Finally, the bureaucratic process may take up to 3 years, meaning that the actual naturalization rate is the result of what happened 10–13 years before. Until the year of the survey (2012) the naturalization rate registered in Italy was low and negligible (1.6%; ISMU, 2015).

Dependent Variables

In both surveys, childcare information derives from a single question “Who are the individuals your child is with when he/she is not with his/her parent(s) or at school?” with different possible answers: alone, grandparents, adult siblings, relatives, extra-family members, baby-sitter, non-need for childcare, young siblings, and others. For analysis purposes, in the first analysis, the outcome variable is grandparent’s childcare, which is a dummy variable taking value one when grandparent’s childcare is verified, 0 otherwise. In the second analysis, we introduced grandparents’ health information. Self-rated health is derived from a single question “How is your health in general?” with five possible answers: very good, good, fair, bad, and very bad. For analysis purposes we used a dichotomous variable, grouping answers into two categories: value 0 for “good health” (very good, good, and fair), one otherwise. Based on grandparents’ self-rated health (SRH) and their attitude to look after their grandchildren, we identified four profiles of grandparents: 1) those who declare bad SRH and no-childcare, 2) those who declare bad SRH and childcare, 3) those who declare good SRH and no-childcare, and 4) those who declare good SRH and childcare.

Empirical Strategy and Independent Variables

In order to accomplish our aims, we conducted two separate analyses. In the first one, by applying a multivariate logistic regression, we analyze the association between the migrant status (migrants vs. Italians), which is the main independent variable, and co-resident grandparents’ childcare. In the second analysis, by applying a multinomial logistic regression, we analyze the association between the migrant status and grandparents’ profile.

We used robust standard errors clustered by household, applying population weights provided in the datasets. We present our results computing the average marginal effects (AMEs) to facilitate results interpretations. AME expresses the effect on p(Y = 1) as a categorical covariate changes from one category to another or as a continuous covariate increases by one unit, averaged across the values of the other covariates included in the model equations.

Control Variables

In both analyses we included a set of individual and family factors:

1) Grandparent’s characteristics: gender (man–reference category, woman), age group (<60 years old–reference category, 60–74, 75+), and grandparent’s occupational status (unemployed/inactive–reference category, employed);

2) Family’s characteristics: mother’s occupational status (unemployed/inactive–reference category, employed), number of grandparent(s) in the family (one GP–reference category, two or more GPs), the presence of child(ren) in pre-school age (no–reference category, yes), and the perception of the household’s economic condition (good/adequate -reference category, poor/sufficient).

In addition to these variables, for the first analysis, we also control for grandparent’s self-rated health.

Finally, since we are interested in the factors affecting grandparental childcare among Italian and migrant multigenerational households, we do not control for the number of parents (i.e., single parent in the family vs. both parents in the family). On the one hand, being a single parent may have very different implications for Italians and migrants (e.g., the availability of support networks). On the other hand, the lack of a parent is a very strong mediator (mainly via economic motivations as discussed in the concluding paragraph) of the effect of all our covariates on grandparental childcare, and including it in the models would conceal the effects we are interested in.

However, we included information on the proportion of multigenerational households considering single parents in the descriptive results to provide a clear description of the sample.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

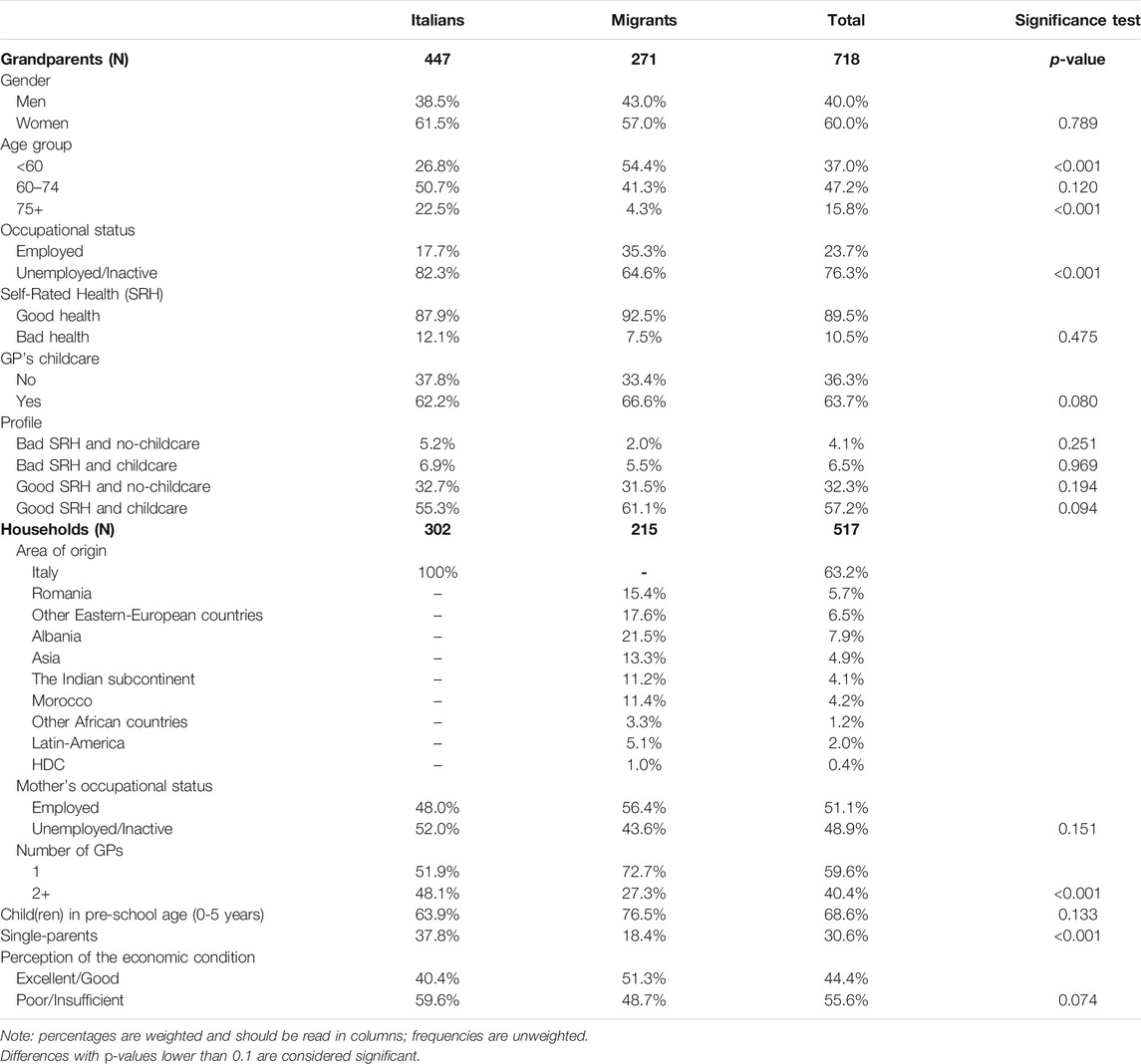

Table 1 presents grandparents’ and households’ characteristics of the sample by migrant status. The last column (Significance test) reports the p-value of the proportion test for the difference between Italians and migrants for each variable. In both populations, the proportion of grandmothers is higher than that of grandfathers. Unsurprisingly, migrant grandparents are younger, the share of those unemployed is lower, and they are in better health than the reference group (although the last result is not significant). There is no large difference in the share of grandparents who look after their grandchild(ren) between Italians and migrants. The distribution of grandparents’ profiles (combining grandparent’s self-rated health and whether they look after their grandchild(ren) or not) is similar within the two populations, except for the share of those who declare good SRH and care, which is slightly higher among migrants than Italians.

As regards the households’ characteristics, among migrant households, 21.5% come from Albania, 15.4% from Romania, and a higher share from other Eastern-European countries (17.6%), followed by Asian countries, the Indian subcontinent, Morocco, other African countries, Latin-America, and a negligible percentage from Highly Developed Countries (HDC).

Although Italian households show a higher proportion of employed mothers than migrant ones (52.0 vs. 43.6%, respectively), the difference is not significant. Most migrant households have one co-resident grandparent, while Italian households present higher percentages of two or more co-resident grandparents. As much as 77.3% of migrant households have child(ren) in pre-school age (0–5 years old) compared to 65.3% among Italian households (the difference is not significant).

Looking at the presence of parents within the multigenerational households, almost 31% of the sample has only one parent, 37.8% among Italian households and 18.4% among migrant households. This relevant difference between Italian and migrant households suggests a different household need. For Italian single parents, the choice of cohabitation could be related to a need for practical and economic support. Conversely, among migrant single parents, the choice might be the result of the migration process.

Finally, results show that Italian and migrant households differ in terms of the perception of the household economic condition, with migrant households displaying a higher proportion of good/adequate conditions than Italian ones. It should be noted that the perception of the economic condition may vary between the two populations. As previously mentioned, this result may suggest and reinforce the reason behind the choice of cohabitation for the two populations. Among Italian multigenerational households, the choice to co-reside with grandparents is also linked to low economic conditions and ability to cope with economic hardships. On the other hand, migrants, particularly first-generation migrants, compare their new conditions with respect to the ones they left in the origin country, rather than with those of natives. Therefore, they may perceive a good economic condition.

Differences in Grandparents’ Childcare between Italian and Migrants

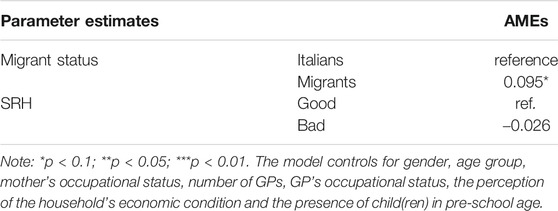

Preliminarily, we analyzed whether there are differences in grandparents’ childcare between Italians and migrants. Table 2 illustrates the AMEs from logistic regression models for the probability of co-resident grandparents’ childcare. Net of all controls, migrant grandparents are significantly more likely (AME = 0.953) to look after their grandchild(ren), while there is no difference by SRH (AME = −0.026 for bad health, not significant).

TABLE 2. Logistic model for the probability of co-resident grandparents’ childcare. AMEs are reported.

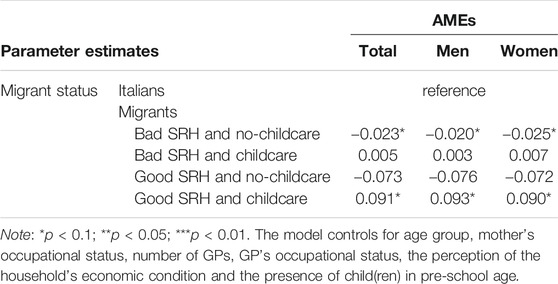

By considering grandparents’ self-rated health, in Table 3 we explored co-resident grandparents’ role. Specifically, if co-resident grandparents provide or receive care. In this context, we computed the AMEs from multinomial logistic regressions for the probability of childcare by grandparents’ profiles. Specifically, results for the total sample show that net of all controls, compared to Italian grandparents, migrant grandparents have both a significantly lower probability of declaring bad SRH and no-childcare (AME = −0.023), and they are 9.1% more likely to declare good SRH and provide childcare. Looking at men and women separately, we explored if such a pattern is the same by gender. We found that the direction and magnitude of the relationship between the main independent variable (migrant status) and the probability of childcare by grandparents’ profiles are very similar to those obtained from the previous model (total sample).

TABLE 3. Multinomial logistic model for the probability of childcare by grandparents’ profile and migrant status for the total sample and stratified by gender. AMEs are reported.

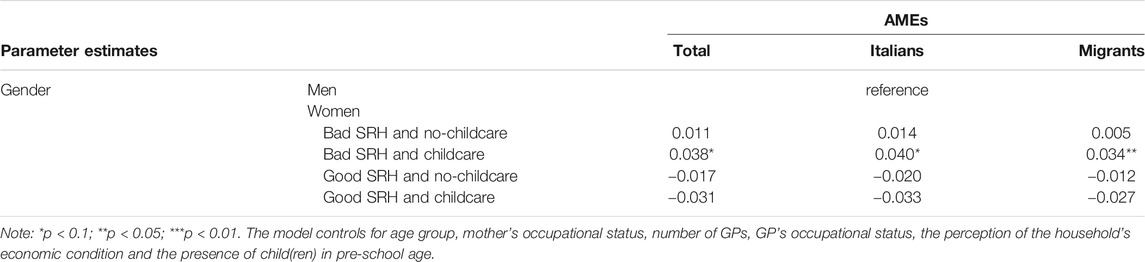

Finally, when analyzing gender disparities, Table 4 displays that gender is a stronger determinant of the probability of providing childcare. Overall, grandmothers are associated with a 3.8% increase in the probability of declaring bad SRH and providing childcare than grandfathers, and such a pattern is evident both among Italians and migrants (4.0 and 3.4%, respectively).

TABLE 4. Multinomial logistic model for the probability of childcare by grandparents’ profile and gender for the total sample and stratified by migrant status. AMEs are reported.

Discussion and Conclusion

Socio-demographic changes of the family in modern societies have modified the meaning of grandparenting, driving the attention towards three-generation interactions and highlighting the key role of grandparents as an important source of help for their (grand)children. Grandparental childcare in multigenerational households, in which children reside with at least one parent and grandparent, is an understudied topic in the European context. In addition, the existing literature that addresses grandparental childcare focuses on the whole population without distinguishing between migrant and non-migrant populations. This study addresses this gap, and it is the first one to investigate differences in grandparental childcare in multigenerational households between Italian and migrant families, by taking into account the role played by grandparents’ health and by gender.

As previously mentioned, studying the Italian context is very interesting. On the one hand it is because in Italy childcare is usually conceived as a female issue (Mencarini and Solera, 2004); on the other hand, it is because the country is characterized by a “familialism by default model” (i.e., characterized by scarce public child-care services and parental leave; Saraceno and Keck, 2010) where grandparents play a central role in providing childcare. Therefore, being a migrant may constitute a further constraint.

In particular, the study sheds light on co-resident grandparents to better understand if the “choice” of co-residence is due to a poor health status, thus the grandparents need care, or conversely, they represent a family support in helping parents by providing childcare.

From an overall analysis, we found that migrant co-resident grandparents are more likely to look after their grandchild(ren) than Italian co-resident grandparents do. This finding might suggest that, in migrant families, co-resident grandparents support and help the family in rearing a child, providing childcare in the host country.

By combining grandparents’ self-rated health and their attitude towards looking after their grandchild(ren), results display that, net of all controls (gender, age group, mother’s occupational status, number of grandparents in the household, grandparents’ occupational status, and the perception of the household’s economic condition), on the one side, migrant co-resident grandparents are significantly less likely to declare bad SRH and no-childcare and, on the other side, they are more likely to declare good health and to provide childcare than Italians. This result confirms the previous one, suggesting that in migrant families, the co-habitation of grandparents is principally linked to childcare support. However, caution should be applied in the interpretation of these results. The selection of individuals into multigenerational households may be linked to other factors. Financial hardship is seen as another important reason for drawing on the support of extended family in the form of intergenerational co-residence (Goodman and Silverstein, 2002; Baker et al., 2008; Dunifon et al., 2014). This might be the case among Italians, where a higher share of households declared a poor/insufficient perception of their economic condition with respect to migrants. Such a result might also reflect a higher percentage of multigenerational households with a single parent among Italians than migrants. Indeed, some studies found that, even in the case of single father or a single mother, those with co-resident grandparents are usually better off financially (Goodman and Silverstein, 2002; Mutchler and Baker, 2004). As explained in the background section, for migrant families, the “choice” of co-residence can be influenced by the Italian family reunification policies.

When gender disparities are considered, the real role is revealed. We found that being a woman, regardless of migrant status, is associated with higher probability of declaring poor health and to looking after grandchild(ren) than men. Such a significant role of gender could suggest that the “familistic” pattern is adopted also by foreigners: grandmothers may be asked to help their daughters and sons in childcare even if their health is poor.

When studying grandparental childcare, we must consider that it requires decision-making at two levels: that of grandparents in addition to parents. Some scholars argue that decisions about childcare and who is the “caregiver” are embedded in contextualized moralities: what individuals consider the “right thing to do” within the social framework in which they live (Duncan et al., 2003; Lewis, 2009). The gender differences observed in the analysisare well-known even in the literature. Actually, the gender division of families’ responsibilities between parents, who conceive childcare as a female issue, is likely to also pertain in the grandparental generation, as a result of traditional role ideology and divergent male and female care and employment trajectories over the life-course (Leopold and Skopek, 2014). The result is that grandmothers would be more likely than grandfathers to provide childcare support, and to add this “work” to their activities.

SRH is a good predictor of morbidity, use of healthcare services, and mortality (Idler and Benyamini 1997). However, health perception differs according to individuals’ characteristics, aspirations, and culture (Jylhä et al., 1998). As regards comparisons across cultures, evidence suggests that ethnic groups differ in their self-perception of health (Bombak and Bruce, 2012). Therefore, SRH may suffer from individual reporting heterogeneity (Bago d’ Uva et al., 2008), and its comparability among native and immigrant populations may be questioned (Jürges et al., 2008). Despite this issue, the literature has validated its use across ethnic groups, genders, and ages, showing that a poorer SRH is associated with higher disease prevalence rate (Chandola and Jenkinson, 2000; Gerritsen and Devillé, 2009; Crimmins et al., 2011).

This study is not without limitations. Our data are cross-sectional and cannot identify causality. We do not know how many grandchildren are cared for by grandparents and we have no information about the frequency of grandparental childcare or about grandparents’ gender role, which is an important factor, especially among migrants characterized by different cultures. Finally, we have no information about whether the dwelling was owned or rented, identified as an important determinant of co-residence (Stephens et al., 2015).

Despite these limitations, our findings provide new information on childcare provided by co-resident grandparents distinguishing between Italian and migrant families. The study suggests that grandparents’ cohabitation is the difference resulting from the need for care or offer of care. Furthermore, we found that, in addition to migrant status and self-report health, gender is a determinant of grandparents’ childcare: women look after grandchild(ren) more than men even with poor health conditions.

Given the increase of the elderly population and the migrant populations, including the aging of the migrant population, and the widespread economic austerity in all European countries, this would lead us to expect an increase in multigenerational households for the same reason as in the United States, especially in familistic countries. Further works are needed to explore the observed patterns in different contexts.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT). Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study. Data are available https://www.istat.it/it/dati-analisi-e-prodotti/microdati with the permission of ISTAT.

Author Contributions

ET: conceptualisation, preparation of the dataset, methodology, formal analysis, writing and editing; SR: conceptualisation, writing, review; LT: conceptualisation, methodology, writing, review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Italian Ministry of University and Research under the 2017 MiUR-PRIN Grant Prot. N. 2017N9LCSC (Immigration, integration, settlement. Italian-Style), PI Giuseppe Sciortino.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1According to the 2011 “Multiscopo–Aspects of Daily Life survey”.

2According to the 2011–2012 “Social Condition and Integration of Foreign Citizen survey”.

References

Aassve, A., Arpino, B., and Goisis, A. (2012). Grandparenting and Mothers' Labour Force Participation: A Comparative Analysis Using the Generations and Gender Survey. DemRes 27, 53–84. doi:10.4054/demres.2012.27.3

Albuquerque, P. C. (2011). Grandparents in Multigenerational Households: the Case of Portugal. Eur. J. Ageing 8 (3), 189–198. doi:10.1007/s10433-011-0196-2

Arpino, B., and Bordone, V. (2014). Does Grandparenting Pay off? the Effect of Child Care on Grandparents' Cognitive Functioning. Fam. Relat. 76 (2), 337–351. doi:10.1111/jomf.12096

Arpino, B., Pronzato, C. D., and Tavares, L. P. (2014). The Effect of Grandparental Support on Mothers' Labour Market Participation: An Instrumental Variable Approach. Eur. J. Popul. 30 (4), 369–390. doi:10.1007/s10680-014-9319-8

Arpino, B., Pronzato, C., and Tavares, L. (2010). All in the Family: Informal Childcare and Mothers' Labour Market Participation (No. 2010-24). ISER Working Paper Series.

Ates, M. (2017). Does Grandchild Care Influence Grandparents' Self-Rated Health? Evidence from a Fixed Effects Approach. Soc. Sci. Med. 190, 67–74. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.08.021

Bago d’Uva, T., O’Donnell, O., and Van Doorslaer, E. (2008). Differential Health Reporting by Education Level and its Impact on the Measurement of Health Inequalities Among Older Europeans. Int. J. Epidemiol. 37 (6), 1375–1383. doi:10.1093/ije/dyn146

Baker, L. A., Silverstein, M., and Putney, N. M. (2008). Grandparents Raising Grandchildren in the United States: Changing Family Forms, Stagnant Social Policies. J. Soc. Soc. Pol. 7, 53–69.

Barbiano di Belgiojoso, E., and Terzera, L. (2018). Family Reunification - Who, when, and How? Family Trajectories Among Migrants in Italy. DemRes 38, 737–772. doi:10.4054/demres.2018.38.28

Barglowski, K., Bilecen, B., and Amelina, A. (2015). Approaching Transnational Social protection: Methodological Challenges and Empirical Applications. Popul. Space Place 21 (3), 215–226. doi:10.1002/psp.1935

Blustein, J., Chan, S., and Guanais, F. C. (2004). Elevated Depressive Symptoms Among Caregiving Grandparents. Health Serv. Res. 39 (6p1), 1671–1690. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00312.x

Bombak, A. E., and Bruce, S. G. (2012). Self-rated Health and Ethnicity: Focus on Indigenous Populations. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 71 (1), 18538. doi:10.3402/ijch.v71i0.18538

Bonifazi, C. (2017). Migrazioni e integrazioni nell’Italia di oggi: Realtà e prospettive. Migrazioni e integrazioni nell’Italia di oggi. Rome: National Research Council E-Publishing, 7–41.

Bonizzoni, P. (2015). Here or There? Shifting Meanings and Practices in Mother-Child Relationships across Time and Space. Int. Migr 53 (6), 166–182. doi:10.1111/imig.12028

Bordone, V., Arpino, B., and Aassve, A. (2017). Patterns of Grandparental Child Care across Europe: the Role of the Policy Context and Working Mothers' Need. Ageing Soc. 37 (4), 845–873. doi:10.1017/s0144686x1600009x

Bryson, K. R., and Casper, L. M. (1999). Coresident Grandparents and Grandchildren (No. 198). In Current Population Reports, Special Studies. U.S. Bureau of the Census. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Casper, L. M., and Bryson, K. R. (1998). Co-resident Grandparents and Their Grandchildren: Grandparent Maintained Families. Washington, DC: Population Division, US Bureau of the Census. doi:10.1037/e410352005-005

Cela, E., and Barbiano di Belgiojoso, E. (2019). Ageing in a Foreign Country: Determinants of Self-Rated Health Among Older Migrants in Italy. J. Ethnic Migration Stud., 1–23. doi:10.1080/1369183x.2019.1627863

Chandola, T., and Jenkinson, C. (2000). Validating Self-Rated Health in Different Ethnic Groups. Ethn. Health 5 (2), 151–159. doi:10.1080/713667451

Chen, F., and Liu, G. (2012). The Health Implications of Grandparents Caring for Grandchildren in China. Journals Gerontol. Ser. B: Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 67B (1), 99–112. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbr132

Costa, G., and Sabatinelli, S. (2011). Local Welfare in Italy: Housing, Employment and Child Care. WILCO Publication no, 2. Available at: http://wilcoproject.eu/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/WILCO_WP2_Report_02_IT.pdf

Crimmins, E. M., Kim, J. K., and Solé-Auró, A. (2011). Gender Differences in Health: Results from SHARE, ELSA and HRS. Eur. J. Public Health 21 (1), 81–91. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckq022

Danielsbacka, M., Tanskanen, A. O., Coall, D. A., and Jokela, M. (2019). Grandparental Childcare, Health and Well-Being in Europe: A Within-Individual Investigation of Longitudinal Data. Soc. Sci. Med. 230, 194–203. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.03.031

Del Boca, D., Locatelli, M., and Vuri, D. (2005). Child-care Choices by Working Mothers: The Case of Italy. Rev. Econ. Household 3 (4), 453–477. doi:10.1007/s11150-005-4944-y

Di Gessa, G., Glaser, K., Price, D., Ribe, E., and Tinker, A. (2016a). What Drives National Differences in Intensive Grandparental Childcare in Europe? Geronb 71 (1), 141–153. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbv007

Di Gessa, G., Glaser, K., and Tinker, A. (2016b). The Impact of Caring for Grandchildren on the Health of Grandparents in Europe: A Lifecourse Approach. Soc. Sci. Med. 152, 166–175. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.01.041

Duncan, S., Edwards, R., Reynolds, T., and Alldred, P. (2003). Motherhood, Paid Work and Partnering: Values and Theories. Work, employment Soc. 17 (2), 309–330. doi:10.1177/0950017003017002005

Dunifon, R. E., Ziol-Guest, K. M., and Kopko, K. (2014). Grandparent Coresidence and Family Well-Being. ANNALS Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci. 654 (1), 110–126. doi:10.1177/0002716214526530

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Friedman, D., Hechter, M., and Kreager, D. (2008). A Theory of the Value of Grandchildren. Rationality Soc. 20 (1), 31–63. doi:10.1177/1043463107085436

Fuller-Thomson, E., and Minkler, M. (2001). American Grandparents Providing Extensive Child Care to Their Grandchildren. The Gerontologist 41 (2), 201–209. doi:10.1093/geront/41.2.201

Gerritsen, A. A., and Devillé, W. L. (2009). Gender Differences in Health and Health Care Utilisation in Various Ethnic Groups in the Netherlands: a Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Public Health 9 (1), 109. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-9-109

Glaser, K., Price, D., Di Gessa, G., Ribe, E., Stuchbury, R., and Tinker, A. (2013). Grandparenting in Europe: Family Policy and Grandparents’ Role in Providing Childcare. Grandparents Plus. Available at: http://www.grandparentsplus.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/EU-report-summary.pdf

Glaser, K., Stuchbury, R., Price, D., Di Gessa, G., Ribe, E., and Tinker, A. (2018). Trends in the Prevalence of Grandparents Living with Grandchild(ren) in Selected European Countries and the United States. Eur. J. Ageing 15 (3), 237–250. doi:10.1007/s10433-018-0474-3

Goodman, C., and Silverstein, M. (2002). Grandmothers Raising Grandchildren. The Gerontologist 42 (5), 676–689. doi:10.1093/geront/42.5.676

Grundy, E. M., Albala, C., Allen, E., Dangour, A. D., Elbourne, D., and Uauy, R. (2012). Grandparenting and Psychosocial Health Among Older Chileans: A Longitudinal Analysis. Aging Ment. Health 16 (8), 1047–1057. doi:10.1080/13607863.2012.692766

Hagestad, G. O. (1986). “The Family: Women and Grandparents as Kin‐keepers,” in Our Aging Society: Paradox and Promise. Editors A. Pifer, and L. Bronte (New York: W. W. Norton), 141–160.

Hank, K., and Buber, I. (2009). Grandparents Caring for Their Grandchildren. J. Fam. Issues 30 (1), 53–73. doi:10.1177/0192513x08322627

Hank, K., Cavrini, G., Di Gessa, G., and Tomassini, C. (2018). What Do We Know about Grandparents? Insights from Current Quantitative Data and Identification of Future Data Needs. Eur. J. Ageing 15 (3), 225–235. doi:10.1007/s10433-018-0468-1

Harding, L. F. (1995). Family, State and Social Policy. New York: Macmillan International Higher Education.

Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., LaPierre, T. A., and Luo, Y. (2007). All in the Family: The Impact of Caring for Grandchildren on Grandparents' Health. Journals Gerontol. Ser. B: Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 62 (2), S108–S119. doi:10.1093/geronb/62.2.s108

Idler, E. L., and Benyamini, Y. (1997). Self-rated Health and Mortality: a Review of Twenty-Seven Community Studies. J. Health Soc. Behav. 38 (1), 21–37. doi:10.2307/2955359

Igel, C., and Szydlik, M. (2011). Grandchild Care and Welfare State Arrangements in Europe. J. Eur. Soc. Pol. 21 (3), 210–224. doi:10.1177/0958928711401766

Ingersoll‐Dayton, B., Neal, M. B., and Hammer, L. B. (2001). Aging Parents Helping Adult Children: The Experience of the Sandwiched Generation. Fam. Relations 50 (3), 262–271.

ISMU (2015). The Twenty-First Italian Report On Migrations. Available at: https://www.ismu.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/XXI-Report_Ismu_III.pdf.

ISTAT (2018). Vita e percorsi di integrazione degli immigrati in Italia, Istat, Roma. Available at: https://www.istat.it/it/files//2019/05/Vita-e-percorsi.pdf.

Jappens, M., and Van Bavel, J. (2012). Regional Family Cultures and Child Care by Grandparents in Europe. DemRes 27, 85–120. doi:10.4054/demres.2012.27.4

Jürges, H., Avendano, M., and Mackenbach, J. P. (2008). Are Different Measures of Self-Rated Health Comparable? an Assessment in Five European Countries. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 23 (12), 773–781. doi:10.1007/s10654-008-9287-6

Jylhä, M., Guralnik, J. M., Ferrucci, L., Jokela, J., and Heikkinen, E. (1998). Is Self-Rated Health Comparable across Cultures and Genders? Journals Gerontol. Ser. B: Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 53B (3), S144–S152. doi:10.1093/geronb/53b.3.s144

Lee, S., Colditz, G., Berkman, L., and Kawachi, I. (2003). Caregiving to Children and Grandchildren and Risk of Coronary Heart Disease in Women. Am. J. Public Health 93 (11), 1939–1944. doi:10.2105/ajph.93.11.1939

Leopold, T., and Skopek, J. (2014). Gender and the Division of Labor in Older Couples: How European Grandparents Share Market Work and Childcare. Social Forces 93 (1), 63–91. doi:10.1093/sf/sou061

Lewis, J. (2009). Work-family Balance, Gender and Policy. Cheltenham, UK/Northampton, MA, United States: Edward Elgar Publishing. doi:10.4337/9781848447400

Mencarini, L., and Solera, C. (2004). “Diventare e fare i genitori oggi: l’Italia in prospettiva comparata,” in La Transizione Alla Genitorialità. Da Coppie Moderne a Famiglie Tradizionali. Editor M. Naldini (Bologna: Il Mulino), 33–59.

Minkler, M., and Fuller-Thomson, D. E. (2001). Physical and Mental Health Status of American Grandparents Providing Extensive Child Care to Their Grandchildren. J. Am. Med. Womens Assoc. (1972) 56 (4), 199–205.

Minkler, M., Fuller-Thomson, E., Miller, D., and Driver, D. (1997). Depression in Grandparents Raising Grandchildren: Results of a National Longitudinal Study. Arch. Fam. Med. 6 (5), 445–452. doi:10.1001/archfami.6.5.445

Mutchler, J. E., and Baker, L. A. (2004). A Demographic Examination of Grandparent Caregivers in the Census 2000 Supplementary Survey. Popul. Res. Pol. Rev. 23 (4), 359–377. doi:10.1023/b:popu.0000040018.85009.c1

Naldini, M., and Saraceno, C. (2011). Conciliare famiglia e lavoro. Vecchi e nuovi patti tra sessi e generazioni. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Palloni, A. (2000). Living Arrangements of Older Persons. Popul. Bull. UN Spec. Issue. 42 (43), 54–110.

Paparusso, A. (2019). Immigrant Citizenship Status in Europe: the Role of Individual Characteristics and National Policies. Genus 75 (1), 1–23. doi:10.1186/s41118-019-0059-9

Pinquart, M., and Sörensen, S. (2003). Differences between Caregivers and Noncaregivers in Psychological Health and Physical Health: a Meta-Analysis. Psychol. Aging 18 (2), 250–267. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.18.2.250

Presidency of the Council of Ministers – Department of Family policies (2020). Nidi e Servizi Educativi per l’Infanzia. Rapporto di ricerca. Available at: https://www.istat.it/it/files//2020/06/report-infanzia_def.pdf.

Rosenthal, C. J. (1985). Kinkeeping in the Familial Division of Labor. J. Marriage Fam. 47, 965–974. doi:10.2307/352340

Ruppanner, L., and Bostean, G. (2014). Who Cares? Caregiver Well-Being in Europe. Eur. Sociological Rev. 30 (5), 655–669. doi:10.1093/esr/jcu065

Ryan, L. (2007). Migrant Women, Social Networks and Motherhood: The Experiences of Irish Nurses in Britain. Sociology 41 (2), 295–312. doi:10.1177/0038038507074975

Santero, A., and Naldini, M. (2020). Migrant Parents in Italy: Gendered Narratives on Work/family Balance. J. Fam. Stud. 26 (1), 126–141. doi:10.1080/13229400.2017.1345319

Saraceno, C., and Keck, W. (2010). Can We Identify Intergenerational Policy Regimes in Europe? Eur. Societies 12 (5), 675–696. doi:10.1080/14616696.2010.483006

Sear, R., and Mace, R. (2008). Who Keeps Children Alive? A Review of the Effects of Kin on Child Survival. Evol. Hum. Behav. 29 (1), 1–18. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2007.10.001

Selwyn, J., and Nandy, S. (2014). Kinship Care in the UK: Using Census Data to Estimate the Extent of Formal and Informal Care by Relatives. Child Fam. Soc. Work 19 (1), 44–54. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2206.2012.00879.x

Stanca, L. (2012). Suffer the Little Children: Measuring the Effects of Parenthood on Well-Being Worldwide. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 81 (3), 742–750. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2010.12.019

Stelle, C., Fruhauf, C. A., Orel, N., and Landry-Meyer, L. (2010). Grandparenting in the 21st Century: Issues of Diversity in Grandparent-Grandchild Relationships. J. Gerontological Soc. Work 53 (8), 682–701. doi:10.1080/01634372.2010.516804

Stephens, M., Lux, M., and Sunega, P. (2015). Post-socialist Housing Systems in Europe: Housing Welfare Regimes by Default? Housing studie. 30 (8), 1210–1234. doi:10.1080/02673037.2015.1013090

Taylor, P., Passel, J., Fry, R., Morin, R., Wang, W., Velasco, G., et al. (2010). The Return of the Multi-Generational Family Household. In A Social & Demographic Trends Report. Washington, DC: Pew Research CenterAvailable at: https://www.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2010/10/752-multi-generational-families.pdf (Accessed March 16, 2021).

Terzera, L., and Barbiano di Belgiojoso, E. (2019). Tempi e modi di fare famiglia tra gli stranieri in Italia. In Vita e Percorsi di Integrazione degli immigrati in Italia. Roma: ISTAT, 53–68. Available at: https://flore.unifi.it/retrieve/handle/2158/1147758/393468/Integrazione%20degli%20immigrati%20%28ISTAT%29.pdf.

Thomese, F., and Liefbroer, A. C. (2013). Child Care and Child Births: The Role of Grandparents in the Netherlands. J. Marriage Fam. 75 (2), 403–421.

Tomassini, C., Glaser, K., Wolf, D. A., Van Groenou, M. B., and Grundy, E. (2004). Living Arrangements Among Older People: an Overview of Trends in Europe and the USA. Popul Trends. 115, 24–35. POPULATION TRENDS-LONDON.

Tomassini, C., and Wolf, D. A. (2000). Shrinking Kin Networks in Italy Due to Sustained Low Fertility. Eur. J. Population/Revue européenne de Démographie 16 (4), 353–372.

Waldrop, D. P., Weber, J. A., Herald, S. L., Pruett, J., Cooper, K., and Juozapavicius, K. (1999). Wisdom and Life Experience: How Grandfathers mentor Their Grandchildren. J. Aging Identity 4 (1), 33–46.

Walker, A. J., Pratt, C. C., and Eddy, L. (1995). Informal Caregiving to Aging Family Members: A Critical Review. Fam. Relations 44, 402–411.

Wall, K., Aboim, S., Cunha, V., and Vasconcelos, P. (2001). Families and Informal Support Networks in Portugal: the Reproduction of Inequality. J. Eur. Soc. Pol. 11 (3), 213–233.

Williams, F., and Gavanas, A. (2008). The Intersection of Childcare Regimes and Migration Regimes: A Three-Country Study. Migration and Domestic Work: A European Perspective on a Global Theme, 13–28.

Keywords: grandparent childcare, gender differences, health differences, migrant population, need for care

Citation: Trappolini E, Rimoldi SML and Terzera L (2021) Co-Resident Grandparent: A Burden or a Relief? A Comparison of Gender Roles between Italians and Migrants. Front. Hum. Dyn 3:642728. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2021.642728

Received: 16 December 2020; Accepted: 20 April 2021;

Published: 31 May 2021.

Edited by:

Enrico Ripamonti, Karolinska Institutet, SwedenReviewed by:

Teresa Castro-Martin, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, SpainFrancesco Della Puppa, Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, Italy

Veronica Riniolo, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, Italy

Copyright © 2021 Trappolini, Rimoldi and Terzera. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Eleonora Trappolini, ZWxlb25vcmEudHJhcHBvbGluaUB1bmltaWIuaXQ=

Eleonora Trappolini

Eleonora Trappolini Stefania Maria Lorenza Rimoldi

Stefania Maria Lorenza Rimoldi Laura Terzera2

Laura Terzera2