- 1School of International Studies, University of Trento, Trento, Italy

- 2Centre de Recherches Politiques de Sciences Po, Sciences Po, Paris, France

EU Member States may legally designate a country as a Safe Country of Origin when human rights and democratic standards are generally respected. For nationals of these countries, asylum claims are treated in an accelerated way, the underlying objective of the “safe country” designation being to facilitate the rapid return of unsuccessful claimants to their country of origin. The concept of “safe country” was initially blind to gender-based violence. Yet, in the reform of the Common European Asylum System (CEAS), which began in 2016, the European Commission proposed two changes: first, that a common list of “safe countries” should be applied in all Member States, and second, that this concept should be interpreted in a “gender-sensitive” manner. In consequence, the generalization of a policy that has been documented as largely detrimental to asylum seekers has been accompanied by the development of special guarantees for LGBTI+ asylum seekers. In light of this, there is a need to examine the impact of “safe country” practices on LGBTI+ claimants and to investigate the extent to which the securitization of European borders is compatible with LGBTI+ inclusion. Based on a qualitative document analysis of EU “safe country” policies and on interviews with organizations supporting LGBTI+ asylum seekers, this article shows that despite the implementation of gender-sensitive safeguards, LGBTI+ asylum seekers are particularly affected by “safe country” practices. These practices permeate European asylum systems beyond the application of official lists, depriving many LGBTI+ asylum seekers of their right to have their protection claims fairly assessed.

Introduction

In 2019, the local and general elections in Greece were won by candidates from the conservative New Democracy party. Referring to asylum seekers, the Mayor of Athens and the Greek Prime Minister both promised to “bring order” to the country, leading to police operations in some districts of Athens and to the tightening of national asylum policies. This took the form of a new law on asylum that was passed in November 2019. One of the instruments introduced by this reform was the concept of “safe country of origin,” which led to the establishment of an official list of such countries in early 2020. This list made Greece the 21st EU Member State to use the “safe country of origin” concept [count based on the 2020 Asylum in Europe Database (AIDA) reports, UK included]1.

Since 2005, the concept of “safe country of origin” has been institutionalized in the Common European Asylum System (CEAS), a package of legislation designed to harmonize asylum policies throughout the EU. Although there is no common EU list of “safe countries of origin,” the 2005 Asylum Procedures Directive and its 2013 recast allow Member States to establish their own national list. These “safe countries” must meet several criteria: namely, to be democratic, respectful of human rights standards, and devoid of indiscriminate violence (Annex 1 of Procedures Directive 2013/32/EU). The asylum claims made by nationals of “safe countries” are examined in an accelerated way, based on the assumption that they are unlikely to be eligible for refugee status. The accelerated procedures entail a reduction in procedural safeguards: claimants have less time to prepare for their interview, they benefit from reduced material assistance (i.e., financial assistance, housing), and in some Member States laws may allow them to be deported before their appeal has been examined (AIDA, 2020).

The principal purpose of “safe countries” lists is to discourage what are presumed to be unfounded asylum claims. Not all countries that satisfy the criteria for “safe” designation are included on these lists as some countries, such as the US or Japan, generate few claimants. The countries on the list generally combine a high number of asylum seekers with high rates of refusal. Senegal, for example, whose nationals make several thousand asylum claims in France each year, and yet only 10% of which are successful2, is on the French list of “safe countries of origin.”

The case of Senegal illustrates one of the major blind spots of the “safe country of origin” concept; namely the lack of consideration for gender-based violence when assessing the “safety” of designated countries. This is particularly problematic for LGBTI+ asylum seekers. In many Member States, countries that punish homosexuality such as Senegal—where it can lead to prison sanctions—are considered “safe” (Winter, 2012). In 2020, the Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Claims of Asylum (SOGICA) project produced a report (Andrade et al., 2020) that highlighted the centrality of country of origin factors in LGBTI+ asylum claims, with supporters of LGBTI+ asylum seekers reporting that country of origin was the primary factor used by authorities to legitimize differences in the treatment of LGBTI+ asylum claims.

Change may, however, be on the way. In the ongoing CEAS reform which began in 2016, the European Commission has advocated both for the enforcement of the concept of “safe country” through the setting up of a compulsory EU list, and for a “gender-sensitive” interpretation of such a concept (European Commission, 2016). “Gender-sensitivity” is a term used in EU policymaking to designate policies “addressing and taking into account the gender dimension” (European Commission, 1998, p. 33) and, in asylum, it is considered as being inclusive of LGBTI+ people3. EU legislation does not specify what a gender-sensitive approach to “safe country” lists means, but some Member States have interpreted it as entailing restrictions clauses to their list (for example, the Netherlands considers Senegal as “safe except for LGBTI”).

As such, the reform has the potential to make both the concept of “safe country” (a concept detrimental to all asylum seekers) and that of “gender-sensitivity” (a notion providing special guarantees to women and LGBTI+ people) a compulsory part of all EU asylum systems. In this context, several questions arise: what is the impact of the notion of “safe country” upon LGBTI+ asylum seekers, and can gender-sensitive safeguards protect them? And, perhaps more importantly, are LGBTI+ rights being utilized in order to facilitate the passage into law of a restrictive policy? Drawing on the concept of “homonationalism” (Puar, 2007), researchers have documented how LGBTI+ rights may be rhetorically instrumentalized as a way to legitimize the exclusion of migrants and Muslims (Bracke, 2012; Mepschen, 2016; Quinan et al., 2020). In this paradigm, the portrayal of countries from the Global South as homophobic would allow European states to present themselves as inherently superior. Muslim and migrants would therefore be regarded as backward and unassimilable precisely because they are suspected of being anti-LGBTI+. Taking this hypothesis seriously, this article therefore takes a close look at the way LGBTI+ rights are incorporated into the EU's approach to asylum and border security.

Security is understood here as a “thick signifier,” which, “rather than describing or picturing a condition… organizes social relations into security relations” (Huysmans, 1998, p. 231). This means that in this article, the concept of “safe country of origin” is analyzed not only for what it “is” (a tool used in the management of asylum claims), but also for what it “does” to asylum policies. Hence it is understood in terms of practices rather than simply as a legal notion, as these practices exceed the official implementation of lists. “Safe country of origin” practices designate an assemblage of discourses, behaviors, and ways of relating to asylum seekers that permeate the field of asylum. This contributes to a “culture of suspicion” (Bohmer and Shuman, 2018), legitimizing the perception of asylum as a security issue.

This article links findings and discussion according to three main themes. It first analyzes the emergence of the concept of “safe country of origin” at the EU level, underlining that not only were LGBTI+ asylum seekers omitted from the initial debate, they were also negatively impacted by the “safe country of origin” concept, as some of their main nationalities were explicitly identified as potentially fraudulent. The second part of this article investigates the impact of this concept on LGBTI+ asylum seekers today. It shows that “safe country” practices permeate the entire asylum procedure and lead to generalized, nationality-based dismissals of asylum applications that affect LGBTI+ asylum seekers very harshly. This second part then shows that EU proposals for a gender-sensitive approach to the “safe country” concept fall short of providing a solution for LGBTI+ claims, and that gender-sensitive safeguards may actually reinforce suspicion toward LGBTI+ asylum seekers. The third part of this article analyzes the emergence of new understandings of “safety” and “safe country” in the EU debate, showing that local organizations have developed a Europeanized counter-narrative on “safe countries of origin.” It concludes, however, that the informal and superficial structure taken by the network of LGBTI+ organizations working on asylum in Europe has inhibited the development of a shared advocacy at the EU level.

Materials and Methods

This research analyzes a legal concept but does so from the perspective of political science. As such, it does not reflect on the conformity of the concept of “safe country of origin” to international standards, nor does it analyze fairness from the point of view of legal theory. Rather, it looks at the development of this concept by contextualizing its emergence and examining the competing visions of “safety” that coexist in the European asylum debate. In order to do so, it combines a qualitative analysis of “safe country” -related EU documents5 with 27 in-depth interviews of organizations supporting LGBTI+ asylum seekers6.

The organizations interviewed were chosen on the basis of their insertion within European networks. They were mostly members of the European branch of the International Lesbian and Gay Association (ILGA-Europe), which is a large and influential LGBTI+ NGO working at the EU level. Others were subscribers to an ILGA-Europe pan-European mailing list on asylum entitled “SOGIESC” (standing for “Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Expression, and Sex Characteristics,” commonly used terminology to refer to LGBTI+ asylum). The objective was to select organizations that could report on “safe country of origin” practices within their own country and express an opinion on the development of a EU-level common list of “safe countries of origin.” The goal of these interviews was not to gain in-depth knowledge of certain countries' legal system but rather to shed light on the debate around the notion of “safe country of origin” within the EU.

This study is based on an in-depth qualitative approach and as such it does not claim that the results obtained through interviews are representative of the situation of all LGBTI+ asylum seekers in Europe. However, even if some of the practices reported did not occur on a large scale, they still inform the way LGBTI+ rights are understood in “safe country practices.” During the selection process, the diversity of interviewees—in terms of geographic location7 and profile of the organizations8—was ensured in order to limit bias.

“Safe Country of Origin” Lists and the Securitization of Eu Asylum Policies

The notion of “safe country of origin” has been criticized by human rights organizations since its emergence in the 1990s. However, after the United Nations Refugee Agency's reluctant approval of the concept in 1991 (Background Note EC/SCP/68), “safe country” practices quickly spread around the EU. This first section shows that these practices were an integral aspect of the process of the Europeanization of asylum policies. Before being vertically enforced by EU legislation, the process initially took an informal and horizontal form, in which security actors played a decisive role. Horizontal means that policy changes were not vertically enforced by EU institutions, but rather were copy-pasted from one country to another. This section then examines the place granted to LGBTI+ rights in this process of securitization of asylum. The overlapping of the geographies of state-sponsored homophobia and of supposed “safety” shows that LGBTI+ rights were considered as irrelevant when securing borders.

“Safe Country” Lists in Early EU Asylum Cooperation

The concept of “safe country of origin” arose on the EU agenda in the early 2000s, with the European Commission's first proposal for a common Procedures Directive. This idea was not, however, new in Europe, as the first formal introduction of the concept of “safe country of origin” was recorded in Switzerland in 1990. The policy then spread around Europe, possibly due to countries' fears of receiving failed asylum seekers from their neighbors if they did not follow the trend (Engelmann, 2014).

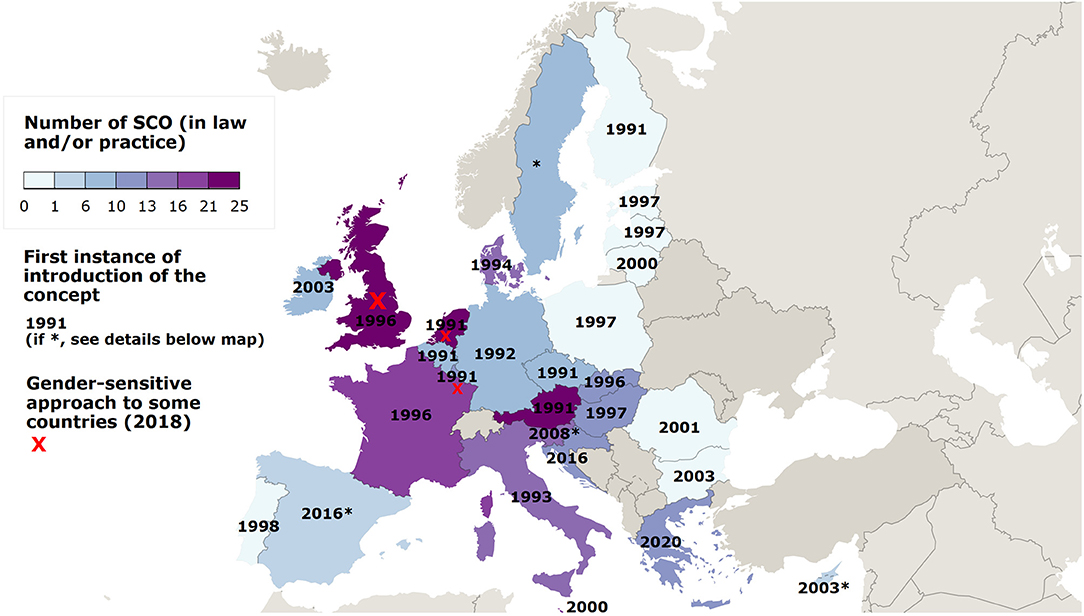

Figure 1 illustrates the expansion of the notion of “safe country of origin” in the EU, both in terms of Member States applying the concept, and in terms of the number of “safe countries” present on national lists. It should be noted that the dates which appear on this map refer to the first introduction of the concept in a country's legal system, and that sometimes, such lists were then withdrawn before subsequently being reintroduced.

Figure 1. “Safe Country of Origin” Practices in the EU in 2020. Basemap from GISCO—Eurostat (European Commission)—Author's compilation based on AIDA (2020), European Migration Network (2018), and Engelmann (2014). For sake of consistency, EU, EEA, Schengen States, Monaco, Andorra, San Marino, and Vatican City were excluded from the count when they were explicitly stated in lists, since they are de facto considered as safe by all EU member-states. Please see the footnote for details on the countries marked by an asterisk4 Made with Khartis.

The first wave of dissemination of “safe country of origin” practices therefore preceded the 2000–2005 CEAS debates. This dissemination was characterized by its informal and horizontal character, which did not, however mean that the EU played no role in this initial stage. On the contrary, it provided a fertile environment for the notion of “safe country of origin” to be developed, as the European environment was marked by two simultaneous trends: the securitization of migration and the Europeanization of security. In the 1980s, ad hoc working groups on security multiplied, bringing together actors promoting intergovernmental cooperation outside institutional constraints (Bigo, 1996). These groups played a fundamental role in framing asylum as a security issue, as they were willing to extend their field of operation in a post-Cold War context where the figure of the immigrant replaced the communist foil (Bigo, 1998).

It is in this context that the term “safety” started to be utilized to justify security-oriented policies. Choosing to focus on the “safety” of some countries (and not on their “security”) was indeed not anodyne, as in the 1990s, the United Nations Development Programme advocated for the idea of “human security,” emphasizing that security should include economic, food, health, environmental, political, personal and community-based considerations. Two trends help explain the choice of “safety” over “security.” Firstly, it is likely that the definition of “human security” was too far-reaching. As asylum policies became increasingly restrictive in the EU, it appeared unlikely that Member States would refer to a conception of (in)security that was broader than the definition of persecution set out by the 1951 Geneva Convention. Secondly, the qualification of countries of origin as “safe” presented the advantage of being in line with other securitizing uses of the notion of “safety” in migration policies. The 1990s−2000s saw the proliferation of terms such as “safe third country,” “super-safe third country,” and “safe havens.”

The case of the UK is illustrative of this trend. In 2002, the British government published a white paper entitled “Secure Borders, Safe Haven,” (Home Office, 2002) which sought to find ways of preventing asylum seekers from arriving in the UK (Sales, 2005). Prior to the US-led military intervention in Iraq, in which the UK participated, the term “safe” was being increasingly utilized to support the idea that asylum seekers did not need protection. As an example, an extended list of “safe countries” was published, and the British government advocated for the implementation of “safe havens” (Sales, 2005). The latter term designated the building of camps outside the EU where asylum seekers would be detained in basic conditions while waiting for their claim to be processed (Statewatch, 2003). These ideas circulated between national and the European levels, since “safe havens” were discussed in 2003 at an EU Justice and Home Affairs Ministers meeting.

In these policy proposals, “safe” and “safety” were not clearly defined. Even today, the notion of “safety” is still vague. These terms suggested individual well-being but set aside its concrete evaluation, putting the accent on what asylum seekers were supposed to have (safety), rather than on what the policies were doing to them (security); thus working as a cache-sexe (concealing something central and yet shameful) for the progressive securitization of a humanitarian field. The first stage of the Europeanization of the concept of “safe country of origin” was therefore based on security-oriented intergovernmental cooperation that bypassed EU institutions.

Nevertheless, the direct role of the EU should not be underestimated, as the development of the CEAS lent legitimacy to the “safe country of origin” concept. By integrating it into the European legal order, the CEAS debates led to a second wave of introduction of lists of “safe countries of origin” in Member States. What was a choice-based alignment before the CEAS became an integral part of the harmonization of EU asylum systems, opening up the possibility of establishing a common EU list of “safe countries of origin.” This idea was discussed in the early stages of the CEAS, and was subsequently abandoned as the European Court of Justice ruled that the European Council would have exerted too much power by establishing the list (case C-133/06, 2008).

This judgment did not, however, signal the end of the “safe country of origin” concept. Discussions on establishing a common EU list were relaunched in the context of the 2015 migration crisis. The discourse justifying the notion of “safe country of origin” in terms of reducing claims and deterring false asylum seekers was, this time, fully appropriated by the EU institutions (see European Commission, 2015a).

The concept of “safe country of origin” has therefore marked decades of formal and informal harmonization of EU asylum systems and is largely tributary to broader logics of securitization and Europeanization of asylum. As such, it is not a peripheral aspect of the CEAS but rather a pivotal concept that shows the incorporation of asylum into the security continuum. It would be simplistic, however, to consider the notion of “safe countries” as simply an illustration of broader trends. On the contrary, it has played an essential role in reorienting the relationship of Member States to asylum seekers—and to LGBTI+ claimants in particular.

LGBTI+ Asylum in the 2000s: Combining Humanitarian and Strategic Incentives

Huysmans (1998) opposes the idea of “security” as a descriptive term that would allow some situations to be qualified as objectively “dangerous” and others as “safe.” For him, “security” should rather be understood as a concept that reorganizes our understanding of the world by marking some aspects of our lives as subjects of security. Drawing on his analysis, this article argues that the notion of “safe country of origin” did not simply flow from EU trends, but in fact it played a crucial role in reorienting EU migration policies toward a more securitized understanding of migration.

The point here is not to know whether asylum seekers from “safe countries” qualify as refugees. For Huysmans, “the question is no longer if the security story gives a true or false picture of social relations… [but] how does a security story order social relations? What are the implications of politicizing an issue as a security problem?” (Huysmans, 1998, p. 232). In this case, the concept of “safe country” played a central role in marking out nationals from these countries—many of which criminalized homosexuality—as undeserving of international protection, and therefore as potentially “fraudulent” and “abusing” of European asylum systems.

Paradoxically, the debates on the “safe country of origin” concept took place within a favorable environment for LGBTI+ activism at the EU level. In the early 2000s, EU-level LGBTI+ organizations gained in respectability and increased their presence in Brussels, seeking to further influence EU institutions (Paternotte, 2016). In this context, ILGA-Europe published several documents on the situation of LGBTI+ people in European societies, referring specifically to LGBTI+ asylum seekers in these reports from the late 1990s. As a consequence, the first directive defining the beneficiaries of refugee status (Qualification Directive, 2004/83/EC) stated that refugee status could be granted to persons persecuted for their sexual orientation, legitimizing the idea of “rescuing” LGBTI+ non-EU nationals. LGBTI+ asylum seekers seemed to have gained legitimacy as the potential subjects of humanitarian policies.

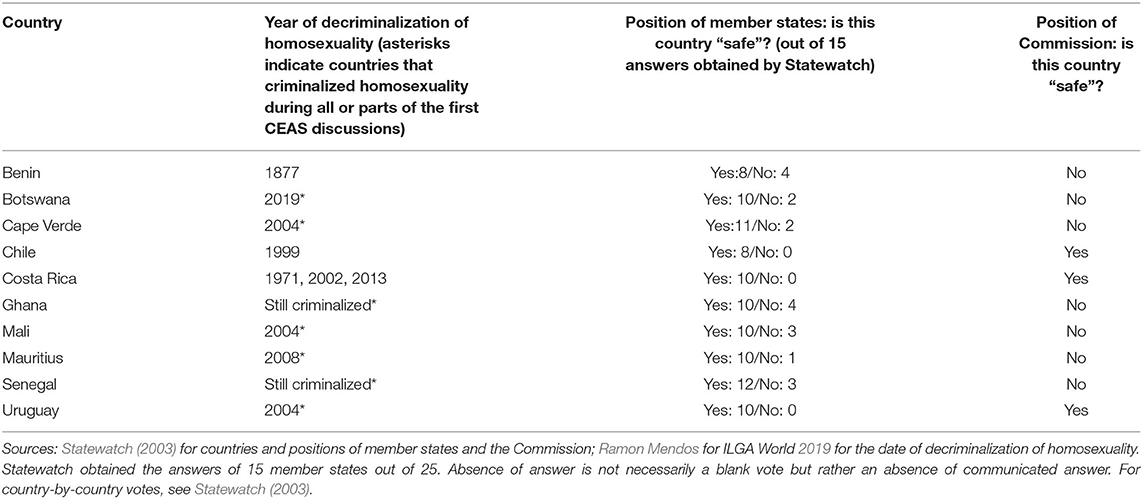

However, consideration for LGBTI+ asylum seekers did not go beyond the Qualification Directive within the ambit of EU law, and the situation of these claimants was not considered from a security and border perspective. On the contrary, many of the countries included on the first draft of a common EU list of “safe countries of origin” criminalized homosexuality, as indicated in the table below. Asterisks indicate countries where homosexuality was still criminalized during all or parts of the discussions on a common EU list (2003–2004) (Table 1).

The overlapping of geographies of “safety” and geographies of state-sponsored homophobia does not reflect an absence of application of criminalizing laws, as LGBTI+ asylum seekers from these countries do arrive in Member States. As an example, between 2005 and 2019, the Association pour la Reconnaissance des Droits des Personnes Homosexuelles et Trans au Séjour (ARDHIS, a French organization supporting LGBTI+ foreigners) provided support to claimants from almost all of the African countries included on the initial draft of the “safe countries” list. During the same period, Senegalese asylum seekers were the most common nationality presenting at the ARDHIS (13%), with Malians also in the top 10 (data from the ARDHIS 2019 annual report, ARDHIS, 2020).

Even though EU institutions had shown their willingness to frame LGBTI+ asylum seekers as legitimate claimants in the Qualification Directive, at the same time, in the Procedures Directive they largely dismissed the violence LGBTI+ people might face with regard to the concept of “safe country.” The way consideration for their struggles disappeared between the publication of the Qualification Directive and the publication of the Procedures Directive shows that if LGBTI+ claimants benefited from some interest from a humanitarian approach, their situation was not considered as relevant from the point of view of border security.

Hence, the concept of “safe country of origin” was, from its beginnings, particularly detrimental to LGBTI+ claimants. It marked out asylum seekers from countries where homosexuality is criminalized as “undesirable” and “fraudulent,” undermining the solidity of their claims.

Impact of Contemporary “Safe Country of Origin” Lists on LGBTI+ Claimants

Change has, nevertheless, been underway in the past few years. Some EU Member States now consider certain countries as “safe only for men” or “safe except for LGBTI+.”9 This section of the article assesses the impact of “safe country of origin” practices on LGBTI+ asylum seekers. It shows that this concept has a negative impact on LGBTI+ asylum seekers, even in countries that have adopted a gender-sensitive approach. The failure of gender-sensitive safeguards to provide for LGBTI+ asylum seekers can be explained by the permeation of “safe country of origin” practices beyond official lists. In many cases, the pervasive and informal nature of “safe country” practices renders them even more difficult to challenge. The second part of this section focuses on the solutions proposed by the European Commission to ensure gender-sensitivity in the development of a common EU list. It shows that in their current design, these solutions are insufficient to remedy the exclusion of LGBTI+ asylum seekers, and that in some instances they risk reinforcing it.

Gender-Sensitive Safeguards to “Safe Country” Practices: A Stalemate

In 2013, the “Fleeing Homophobia” report analyzed the multiple exclusions LGBTI+ asylum seekers faced in the EU (Spijkerboer, 2013b). The report cites examples of asylum authorities requesting claimants to be “more discreet” about their sexuality/gender identity in order to avoid persecution, using this reasoning as a basis to return asylum seekers to their country of origin. The authors of the report also underlined that asylum officers often used stereotypical or humiliating questions when assessing LGBTI+ asylum claims, and that the belief that LGBTI+ asylum seekers would be lying was particularly widespread (Spijkerboer, 2013b). Most of these findings were confirmed in the 2020 SOGICA Survey Report. However, what arose in this report in contrast to the “Fleeing Homophobia” report is that issues related to the country of origin of LGBTI+ claimants have become a central part of their struggles. Respondents from organizations supporting LGBTI+ asylum seekers reported that accurate country of origin information was often unavailable; and when asked about the differences they perceived in the treatment of LGBTI+ asylum claims, “country of origin” was reported as the primary factor legitimizing such differences (Andrade et al., 2020).

The concept of “safe country of origin” further entrenches the ways in which country of origin information takes precedence over personal history in the evaluation of LGBTI+ asylum claims. This leads to generalized dismissals of claims that may neglect legitimate fears of persecution. Based on the interviews carried out with organizations supporting LGBTI+ asylum seekers, two major types of consequences of “safe country” practices on LGBTI+ claimants were identified: (1) the exacerbation of time and credibility issues and (2) the legitimization of informal practices of exclusion.

Exacerbating Time and Credibility Issues

As Pitea (2019) underlines, the very efficacy of the notion of “safe country” relies on asylum seekers' lack of information about their own rights, allowing for the quick dismissal of their claims and for their swift deportation. In some countries, such as France, Germany or the UK, it is legally possible to deport an asylum seeker before their appeal has been examined (AIDA, 2020). This acceleration of procedures is detrimental to LGBTI+ claimants because it means that some asylum seekers may be deported before they have revealed their sexual orientation or gender identity (“coming out”). According to the organizations interviewed, cases of “late disclosure” are indeed very common among LGBTI+ asylum seekers, and by shrinking the asylum time frame, the concept of “safe country” may simply prevent such late instances of “coming out.” This is also the case in countries where gender-sensitive safeguards apply (principally through the non-application of the concept of “safe country” to LGBTI+ claimants), as it presupposes identifying LGBTI+ people at an early stage in the asylum process. Those who do not speak up are submitted to the accelerated procedure, and safeguards therefore fail to protect the asylum seekers most afraid to talk about their identity.

Furthermore, time is often key in re-structuring LGBTI+ life stories so that they appear credible to asylum authorities. The way LGBTI+ asylum seekers have to conform to certain scripts in order to be considered credible by asylum authorities has been largely documented (Kobelinsky, 2012; Giametta, 2017; Fassin and Salcedo, 2019). Many of the organizations interviewed reported that they often spent a large amount of time helping asylum seekers re-organize their life story. This is exemplified in the contribution of Maria Kortenbach of LGBT Asylum (Denmark):

We are not lawyers… we mainly have this approach where we go over the timeline of the life because then when they meet the immigration services, it will help them to structure their interview. So we try to mirror that beforehand, [because] it's a matter of trying to talk about your sexuality or your gender identity before you do it in a setting where every single word is kept against you. [The authorities] mostly carry out two interviews, and they take the minutes of these two interviews and overlap them. And if there are minor differences, they will likely deem the applicant not credible, and give a rejection. So, what we are trying to do is… to prepare people to tell consistent or coherent stories, two or three times. Sometimes it's just a matter of making a list of former sexual partners, or going back to what was his or her name, if this was in the fall or not… (personal communication, 22/11/2019).

Time is therefore much needed to consolidate the credibility of LGBTI+ asylum claims, and this need seems to be largely incompatible with accelerated procedures. This problem also exists in countries where accelerated procedures are not supposed to apply to LGBTI+ claims: in France, Aude Le Moullec-Rieu (ARDHIS) reported that Senegalese LGBTI+ cases remain classified according to the “safe country” status of Senegal, even though they should not be (personal communication, 27/11/2019).

Finally, “safe country of origin” practices have a direct and uncontrollable impact on the credibility of asylum claims, as they “create an institutional bias for decision-makers in terms of a country of origin's presumptive safety” (Atak, 2018, p. 183). In this context, the concept of “safe country” becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy: presumptions of safety are so overarching that asylum seekers have a greater chance of being refused, leading to a drop in the number of cases where asylum is granted, which in turn justifies the labeling of the country as “safe.” In Italy, where a list of “safe countries of origin” was re-implemented in 2019, and despite the fact that this list is supposed to take into account LGBTI+ rights, Jonathan Mastellari (president of the organization Intersectionalities and More) reported a detrimental impact on Albanian asylum seekers, with the first decision to refuse asylum delivered immediately after the list came into force—refusing refugee status to an asylum seeker who was a visible LGBTI+ activist, had been publicly threatened, and came from the same region of Albania as asylum seekers who had previously been granted refugee status (personal communication, 28/11/2019).

The concept of “safe country” therefore heightens time and credibility issues for LGBTI+ asylum seekers. This is even more crucial as these two issues (time and credibility) are tightly interdependent matters: time is often key to credibility. The increased suspicion that LGBTI+ asylum seekers experience combined with shorter time frames leads to unattainable standards of proof for LGBTI+ asylum seekers.

Legitimizing Informal Practices of Ex Ante Exclusion

The presence of “safe country of origin” lists legitimizes a vast array of informal practices, behaviors, and ways of relating to asylum seekers that are rooted in suspicion and prejudice. These behaviors are part of the broader “logics of suspicion” documented by Bohmer and Shuman (2018). By giving suspicion legal legitimacy, lists of “safe countries” contribute to the depersonalization of claims, which are assessed principally through the prism of nationality and not of personal history (Costello, 2005). In LGBTI+ cases, the combination of a lack of information about the situation of LGBTI+ people in some countries and stereotypes about certain nationalities results in informal practices of exclusion ex ante.

The lack of appropriate LGBTI-specific country of origin information has been signaled as particularly problematic in recent years (Jansen, 2014; Andrade et al., 2020). Several of the organizations interviewed reported submitting country of origin reports for the claimants they were supporting to complement the partial information possessed by asylum authorities. These organizations also reported that very often asylum officials considered countries to be “safe” based on a simplistic understanding of “safety”, as described by Collette O'Reagan of LGBT Ireland:

Generally, we feel that we can put up a good appeal because the allies we have around the group are quite diverse in terms of their living abroad experiences. We have a lot of experiences to draw on, which may contradict what the interviewing officer has written in the rejection letter… or their feeling that there are safe spaces within your country, that you can move around your country… Again, at the appeal stage we try our best to explain that the reach of family in other countries and cultures can be widespread, even to abroad, so safety within a country is not an option—protecting and upholding family honor is a dangerous enemy of LGBT+ people moving within their borders or to neighboring countries. Also living in fear all the time, is that really an option, is it really what our Dept. of Justice is saying to LGBT+ people? (personal communication, 27/11/2019).

Similarly, in the 2016 Procedures Regulation proposal Albania's “safety” was justified by its anti-discrimination legislation, even though the government's capacity to protect LGBTI+ people has been called into question by NGOs and international institutions (see ERA, 2017).

Presumptions of safety are not limited to the countries officially marked as “safe.” Most of the organizations interviewed reported that asylum officials relied on informal presumptions of “safety” when refusing asylum claims. These presumptions of safety are not grounded in an objective and documented lack of violence in a country. Rather, they seem to be rooted in political considerations and prejudices, visible in the discrepancies that exist between EU countries. For Marty Huber (Austria):

Depending on where people are from, we can already know at 100% that it is going to be a ‘no’. For example, Afghanistan, in the first instance it is 99.9% ‘no’… Same for Nigeria, there has been racist propaganda against Nigerians in the media for at least ten years. In Nigeria generally homosexuality is punishable with up to 14 years in jail, in the Northern part you have the Sharia and people are threatened by the death penalty. But still, we have a case pending for nine years and they are not questioning the homosexuality of the person, but they say no, it's ok, you can live in Nigeria. And this would not happen with, say, Iran or most of the cases concerning Iraq. (Marty Huber, Queer Base, Austria, personal communication, 10/12/2019).

Inversely, David Nannen, activist in Germany, states that:

“It also depends on the origin of the refugees. This is our feeling, if people from Iran say that they are gay, it's much more difficult to convince the authorities compared to a statement coming from a refugee from Afghanistan.” (personal communication, 29/11/2019).

Neither Iran nor Afghanistan are on the list of “safe countries of origin” in any EU country; such generalized dismissals should therefore not exist. Yet, apparent in many of the interviews was the fact that presumptions of safety extend far beyond official lists. These presumptions of safety are not based on a documented lack of violence, but rather on the perception that the country is mostly safe for non-LGBTI+ and that people therefore fake their sexual orientation or gender identity in order to obtain refugee status. This is an underlying element of the accounts given above, and is particularly visible in the following testimony:

If you are Gambian and you claim asylum because you are lesbian, they have seen so many “fake” cases that now they do not grant protection on those grounds to anyone coming from Gambia. Many people have been in a same-sex relationship here in Italy, it's clear that they are gay, but since they are Gambian, they will not get the refugee status.

(Carlo*, Italy, personal communication, 17/04/2020).

The suspicion that claimants are lying can even extend to doubting their real nationality, a scenario in which their purported nationality has been selected to escape from “safe country” designation. Hanna* from Germany recounted one such case where asylum officials suspected a claimant of lying about his nationality and of coming from a neighboring country that was considered “safe.” To verify this, they contacted officials from the claimant's country and asked them to go to the claimant's address to confirm his real origin (personal communication, 20/12/2019). Such practices endanger asylum seekers if they are sent back, since the authorities know that they have filed an asylum claim and have their home address.

Presumptions of safety therefore largely affect LGBTI+ asylum claims, even in contexts where anti-LGBTI+ violence is documented. By instilling the idea that claimants from the same country are all similar and may be lying en masse, the concept of “safe country of origin” thus symbolically legitimizes these generalized dismissals. The consequence for LGBTI+ claimants is that their claims may be dismissed before they have had the opportunity to talk about themselves, as Adriana* from Cyprus describes:

When it's not a country where it is known that there is a war, they are a bit stricter. It definitely affects LGBT people: I once had someone from Iran, and now the authorities know that there are problems in Iran, but when this case happened… this person didn't even have a chance to talk about his identity during the interview. I assume it was related to the fact that they were trying to dismiss Iranians in general (personal communication, 05/12/2019).

The concept of “safe country of origin” therefore permeates asylum procedures long beyond “safe country” lists are applied. By legitimizing nationality-based generalized dismissals of asylum claims, many LGBTI+ asylum seekers are prevented from having access to a fair procedure. The implementation of safeguards (in particular considering countries as “safe except for LGBTI+”) is unlikely to remedy these issues, since it simply reinforces the suspicion that claimants pretend to be LGBTI+ to avoid the accelerated procedures entailed by their nationality.

Future research is needed to confirm the extent to which the practices analyzed in this section take place in the EU, as the number of interviews carried out is too low to be able to generalize the findings. However, even if these behaviors were found not to be widespread, their presence demonstrates that “safe country of origin” lists are detrimental not only to some nationalities, but to all LGBTI+ asylum seekers. This finding contradicts the argument that “safe country of origin” lists are a tool for concentrating efforts on those most in need. Contrary to such a narrative, the concept of “safe country of origin” does not make it possible to differentiate between “genuine refugees” and “bogus migrants”: rather it merges them together. Furthermore, by symbolically legitimizing nationality-based dismissals of asylum claims, the concept of “safe country” legitimizes the reliance of authorities on broader presumptions of “safety.” This leads to informal practices of nationality-based dismissals of claims which do not reflect an absence of persecution but rather reflect political considerations and/or prejudices in the host country. As these practices are little formalized, they cannot be held to account.

The 2016 Procedures Directive Recast Proposal and LGBTI+ Rights

It is in this context of disorganized multiplication of the uses and meanings of “safety” that the European Commission has tabled proposals seeking to harmonize and systematically enforce the concept of “safe country” throughout the EU. This section seeks to analyze whether these proposals could help to reduce the issues faced by LGBTI+ asylum seekers in Europe today. It shows that despite increased attention being granted to gender and LGBTI+ rights, such rights are treated as a normative and not as a strategic issue, therefore not translating into a change of security policies.

The place granted to gender-sensitivity in the 2016 proposed Procedures recast has slightly increased compared to the previous 2013 Procedures Directive. Both documents advocate for a “gender-sensitive” approach to the concept of “safe country of origin,” stating that the “complexity of gender-related claims” must be considered when applying this notion (recital 18, European Commission, 2016). What this gender-sensitive approach entails is not defined. Overall, the 2016 and 2013 files are largely similar with regard to gender-related aspects; however, the 2016 proposed recast shows a broadened understanding of what “gender” means, referring much more extensively to sexual orientation, gender identity and—for the first time in EU asylum policies— sex characteristics.

Yet in parallel to this broadened understanding of gender-based persecution, discourses on claimants from “safe countries of origin” have harshened. The notion of “safe country” is repeatedly associated with vocabulary related to fraud throughout the text. This is visible in the Commission Explanatory Note, which states that:

The accelerated examination procedure becomes compulsory under certain limited grounds related to prima facie manifestly unfounded claims, such as when the applicant makes clearly inconsistent or false representations, misleads the authorities with false information or when an applicant comes from a safe country of origin. Similarly, an application should be examined under the accelerated examination procedure where it is clearly abusive…

(European Commission, Explanatory Note 2016, bold added).

In the above excerpt nationality (a characteristic attributed at birth) is placed side-by-side with behaviors considered to be deviant or criminal, showing a slippage in EU policies between a person's origin and possible criminal conduct. Article 36 (5) further states that claimants filing “manifestly unfounded claims” (a category under which “safe country of origin” falls) could be refused the examination of their asylum claim on the basis of its individual merit. This article was subsequently deleted by the European Parliament, but nevertheless represents the culmination of ex ante refusals based on presumptions of “safety.”

The combination of gender-sensitivity with restrictive policies is not a new dynamic in the CEAS. Scholars analyzing the 2013 recast of the Procedures Directive had already underlined the fact that asylum seekers were being simultaneously portrayed as “vulnerable victims” and “bogus and fraudulent migrants” (Costello and Hancox, 2015). Yet, in the case of the “safe country of origin” concept, it must be noted that these two figures are not granted the same legal value.

In fact, gender-sensitivity is provided in recitals (an explicative text inserted before law articles, providing information and exposing the rationale of the text) but disappears from operative provisions. This difference is important: recitals do not have binding power since their purpose is only to clarify provisions. This dualism is particularly useful in reconciling contradictory requests (Lavenex, 2018): where operative provisions set restrictive policies, recitals uphold the EU narrative of gender equality and LGBTI-friendliness by inciting Member States to interpret these policies carefully. However, no pragmatic solutions are offered by the proposed Procedures Regulation, and gender-sensitivity remains a general principle. Without clear guidelines and depending exclusively on the goodwill of Member States, these calls for gender-sensitivity are likely to have limited implications for claimants.

More importantly, it seems that the attention granted to the situation of LGBTI+ people in the assessment of “safety” has shifted in an unexpected way. In recent decades, scholars have analyzed how LGBTI+ rights may be utilized for nationalist purposes, and in particular as a way to portray societies in the Global North as inherently tolerant and open-minded, contrasting with the depiction of migrants and Muslims as sexist and homophobic (Puar, 2007). In the case of asylum, researchers have argued that LGBTI+ asylum seekers may be more welcome than their heterosexual counterparts as long as they fit occidental stereotypes of homosexuality (Murray, 2014; Llewellyn, 2017). Following this analysis, LGBTI+ rights could be expected to be a central criterion to assess a country's “safety.”

However, the attention the European Commission gives to LGBTI+ rights when assessing a country's safety is ambiguous. During the debates on the notion of “safe country of origin” in the 2000s, LGBTI+ rights were simply omitted. In the 2015 Commission proposal for a Regulation establishing a common EU list of “safe countries of origin” (subsequently merged into the 2016 proposal for a new Procedures Regulation), the Commission acknowledged that violence against LGBTI+ people exists in all of the countries on the list, but portrayed it as “individual cases,” and therefore as insufficient to overturn the presumed “safety” of the countries listed. For example, on Kosovo, the 2015 proposal states that:

Discrimination or violence against individuals belonging to vulnerable groups of persons such as women, LGBTI and persons belonging to ethnic minorities, including ethnic Serbs, may occur in individual cases.

(European Commission, 2015b, 5, bold added).

Table 2 synthetizes the 2015 proposal on an EU “safe countries of origin” list, listing the groups that are recognized as facing violence in each of the proposed “safe countries.” This document therefore exemplifies two dynamics that affect LGBTI+ claims: the minimization of violence faced by LGBTI+ people and the ongoing exclusion of some categories of the population from the conception of the political community.

The European Commission considers the violence faced by the groups listed above to be instances of discrimination or isolated acts, thus contradicting numerous reports published on the topic10. Such downplaying of the violence faced by LGBTI+ people is a documented phenomenon. Spijkerboer, in particular, has argued that what would constitute persecution if it targeted a political opponent in an authoritarian regime (harassment, police refusal of protection, beatings, serious death threats) is often considered as “acceptable” when targeting LGBTI+ people. For him, “the idea that sexual minorities must settle for less than straight people is fundamental in refugee law doctrine and practices,” and he further argues that this “subsumption of physical violence under the concept of discrimination… assumes that some extent of violence against LGBT people is only natural, something that one will have to put up with, and that therefore does not count” (Spijkerboer, 2013a, p. 223).

The logical consequence of the 2015 proposal for a Regulation on “safe countries of origin” is that some categories of the population (women, children, LGBTI+ people, ethnic minorities, journalists, etc.) are expected to settle for fewer rights and less protection than they are entitled to. The violence they face is considered as unrepresentative of the general situation in their country. By portraying their situation as necessarily “specific,” this logic reduces these populations to their perceived difference, considered as irreducible, and therefore calls into question their ability to represent their own political community.

It is important to note that such partial exclusion from citizenship cannot be fully explained by the fact that these groups are numerically small. In the case of Kosovo, women (the numerical majority) are considered as facing violence, but the country is still considered to be “safe.” “Minority,” therefore, has a symbolic value rather than a numerical one: it designates groups falling at the lower end of the citizenship ladder. Despite claims of gender-sensitivity, the lack of importance granted to gender-based violence in assessing “safety” shows the persistence of traditional exclusions from the political community—which is itself a gendered and sexual object (Pateman, 1990).

To the question of whether gender and LGBTI+ considerations are included in the EU approach to security, the new proposed EU list shows that such inclusion is largely built on an “add-on” mode. Even though calls for a “gender-sensitive” approach to the notion of “safe country” seem to be on the rise, the principles upon which the notion of “safe country of origin” is based and their consequences on LGBTI+ claimants are never really questioned. The differentiation between “security” and “safety” evoked earlier is important here: it is the vague and ambiguous concept of “safety” that is claimed to be gender-sensitized, not border management and even less the conception of the political community. In this sense, despite the existence of discourses asserting that LGBTI+ rights are integral to the European identity, former logics of exclusion of LGBTI+ people from the community still pervade the logics of border securing.

Civil Society Production of a Europeanized Counter-Discourse on “Safety”

Organizations supporting LGBTI+ asylum seekers have repeatedly denounced the lack of consideration for LGBTI+ rights in the application of the “safe country of origin” concept. Nevertheless, it would be simplistic to assume that their relationship to the idea of “safety” only takes the form of a principled opposition. Rather, they utilize the concept of “safety” as an object of critique, a tool for questioning policies, and as an ideal to achieve. Foregrounding the practices of these organizations, this section analyzes the emergence of a Europeanized counter-discourse on the notion of “safe country of origin.” The first part examines the way LGBTI+ asylum organizations oppose presumptions of “safety” in asylum claims while, in parallel, mobilizing the notion of “safety” to question broader asylum policies. This ambiguous use of “safety” is shared among organizations in different countries, leading to the production of a Europeanized counter-discourse on the notion of “safe country,” and to the structuring of a transnational network of LGBTI+ asylum organizations. This article concludes with an analysis of this process of Europeanization, seeking to understand the failure of organizations to build a shared EU-level advocacy on “safe country” policies.

Uses of “Safety” in the Discourses and Practices of Organizations Supporting LGBTI+ Asylum Seekers in Europe

An important omission in the concept of “safe country of origin” is the idea that EU Member States could be “unsafe” for some people too. Protocol 24 on asylum for nationals of Member States of the European Union (the “Aznar Protocol”) declares all EU Member States to be “safe countries of origin,” with the exception of certain specific situations. The Dublin Regulation is based on the same rationale, as it forces asylum seekers to file their claim in their EU country of arrival, based on the idea that human rights are applied consistently throughout the EU. LGBTI+ asylum organizations, however, call into question the idea that there could be a fair list of “safe countries of origin,” that the EU would be “safe for all,” and finally, that asylum claims are processed equally in all Member States.

The organizations interviewed all opposed the notion of “safe country of origin,” basing their opposition on the idea that LGBTI+ asylum seekers are just as impacted by restrictive policies as other asylum seekers. As Aude Le Moullec-Rieu (ARDHIS, France) explains, “there is no triage [between LGBTI+ and non-LGBTI+ asylum seekers] when policies are tightening” (personal communication, 27/11/2019). A similar idea is expressed by Elias* (Malta):

People at the Refugee Commission get training about LGBT issues, how to use vocabulary, but for us it's sugar coating, it is not the most important issue… On paper we look like this liberal country with good wording on non-binarity, but then, we are putting people in detention, and in detention there are LGBT people… We do not want this sugar coating. We want a safe place, for all, not only for LGBT people—even though of course, we are specializing in LGBT issues.

(personal communication, 21/04/2020).

As the testimony of Elias demonstrates, many organizations have developed a concurrent use of the term “safety,” presenting “safety for all” as an ideal (yet) to be attained. This is representative of larger trends within the LGBTI+ movement, which has granted central importance to “safety” since the 1990s (for a discussion see the work of The Roestone Collective, 2014).

Consequently, the way LGBTI+ asylum organizations frame “safety” contrasts with the legal framework set out by the Procedures Directive, which defines it in a mostly negative way—as an absence of persecution. The organizations interviewed tended to adopt a much more positive definition of the concept, with “living safely” entailing not only freedom from persecution, the right to good health and the full recognition of one's identity (through legal gender recognition for transgender claimants, for example), but also the right to live with one's partner, dignified living conditions, access to the job market, and integration.

Therefore, going beyond what could appear as a monolithic and principled opposition, LGBTI+ asylum organizations routinely negotiate the notion of “safe country of origin.” They publish press releases opposing “safe country of origin” lists11, but these are only the tip of the iceberg. More often than not, their opposition to “safe country” practices takes the form of ad hoc practices. These practices often rely on information sharing, as described by Marty Huber (Queer Base, Austria), who explained that when judges did not believe that, for example, lesbians may be punished by “corrective rape” in some countries, Queer Base mobilized its transnational network to access legal decisions acknowledging such threats (personal communication, 10/12/2019).

What is particularly interesting in the way LGBTI+ asylum organizations negotiate the idea of “safe country” is that they have extended this concept to the EU itself, developing a concurrent use of the notion of “safety,” broadening its scope (“what safe means”) and its reach (“where (un)safety is”). By doing so, they articulate all the stages of LGBTI+ asylum seekers' journeys (from the country of origin to the host country), incorporating European asylum procedures into the broader picture of LGBTI+ “unsafety.” The notion of “safety” is therefore reinvested as a tool to contest EU asylum policies. Organizations reported that they often opposed Dublin decisions12 on the basis that sending a particular asylum seeker back to their country of arrival in the EU would not be “safe” for them. Substantial negative information on the country of arrival is needed for such contestation to be effective, leading organizations to share information on their countries' mutual “unsafety.” An organization in one country may request information from a sister organization in another country to argue that it is unsafe to send back an asylum seeker, while also producing documents affirming that their own country is not safe either.

What always surfaced in interviews was a critique of the inability of the EU to ensure the safety of LGBTI+ asylum seekers. This includes criticism of the management of accommodation centers (harassment and sexual abuse were systematically reported), the lack of training of asylum officers and social workers, as well as the persistence of LGBT phobias in European societies. Organizations also emphasized how legal divergences between Member States could lead Europe to be “less safe” for some asylum seekers compared to others, particularly in relation to transgender rights (difficulties accessing medical transition, the impossibility of changing a foreigner's gender markers in some states) or to intersex mutilations (parents of intersex children sometimes seek asylum in order to access corrective surgery for their children, a practice which is still accepted in most Member States)13.

Building on the perception of the EU as “unsafe,” LGBTI+ asylum organizations have further called into question the idea that Member States are themselves “safe countries of origin.” Evoking the issue of legal gender recognition, Marta Ramos (ILGA-Portugal) argued that “we are talking about basic human rights, the rights to one's identity, rights to health standards. Who are we, as EU Member States, to think that we are safe enough for everyone?” (personal communication, 12/11/2019). On the other hand, Aaro Horsma of Helsinki Pride Community, Finland, reported that his organization supported a young North African man who claimed asylum in Finland because he was persecuted by his family, based in France, and could not get police support there. He was sent back to France, where his residence permit had expired and where he may have been deported back to his country of origin. This led Horsma to conclude that “hopefully at some point we'll be more aware of what is the responsibility between EU countries, since there are people who are threatened in their own families and communities in European countries” (personal communication, 11/12/2019).

To conclude, the same networks of information sharing are mobilized to contest the “safety” of countries of origin (dissemination of court judgments, institutional reports) and even of the EU itself (reports on violence in Member States, information on EU policies). These hybrid forms of contestation, combining press releases, administrative appeals, report writing and information sharing, lead to the construction of a counter-discourse on the concept of “safe country of origin.” This counter-discourse produces in turn an alternative geography of “safety” that articulates the “unsafety” for LGBTI+ claimants of their countries of origin, of other EU Member States, and finally of the very Member State where asylum is being claimed.

Failure to Build Common Advocacy at an EU Level

The LGBTI+ asylum organizations' practices of contestation around the notion of “safe country of origin” largely rely on the presence of pan-European networks. These networks can take a physical form, for example ILGA-Europe's annual conferences; but on an everyday basis they mostly rely on digital tools, entailing the use of mailing lists, online reports, etc. Nonetheless, even in their digital form, these networks are facilitated by EU integration processes. The last part of this article draws on the literature on social movements to examine the conditions necessary to the emergence of a shared EU-level advocacy on the notion of “safe country of origin.” Indeed, the counter-narrative on the uses of “safety” analyzed in the previous section is becoming increasingly harmonized throughout the EU, as it relies on transnational cooperation between organizations.

Can the building of such harmonized counter-discourse on “safety” lead to collective mobilization of LGBTI+ organizations at the EU level? At first sight, there seems to be potential for such mobilization to occur. Collaboration with civil society actors is very important for EU institutions (Ruzza, 2015); and several well-established organizations are present and active on LGBTI+ and migration issues. The role of these actors in compensating for the restrictive vision carried by other EU actors has been studied in the case of the CEAS (Schittenhelm, 2019).

ILGA-Europe's action has, in fact, facilitated the emergence of this counter-discourse on “safety.” It has set up a mailing list (“SOGIESC”), fostering requests for information and reports on the situation of other countries. In interviews, this mailing list was viewed positively and appeared to be a demand that organizations had already formulated to ILGA-Europe some time ago. This list has increased both the circulation of information on LGBTI+ asylum issues and communication between organizations. Moreover, during interviews, many organizations reported being connected to ILGA-Europe, whether formally (i.e., membership, participation in conferences) or on a more informal level (following their work, using ILGA-Europe reports).

Two paths to an EU-level common advocacy on “safe country of origin” lists are thus open to LGBTI+ asylum organizations: the transfer of their claim to delete “safe country of origin” lists to existing EU-level NGOs such as ILGA-Europe, which are largely professionalized and efficient in developing discourses that fit the accepted patterns of influence of EU institutions; or the building of alternative advocacy networks with a more radical component (Monforte, 2009). Indeed, what was observed in interviews is that LGBTI+ asylum organizations often have a dual identity: most are politicized and have a left-wing orientation (ranging from “respectability-oriented” to “no-border” organizations14), while at the same time many have built working relationships with their national authorities (such as the OFPRA in France).

This ambiguity in theory allows them to exploit both paths to European action. In both cases, the presence of a shared issue (“safe country of origin” practices) and the current debates around the constitution of a compulsory EU list could favor the emergence of coordinated action. Nevertheless, in spite of the fact that ILGA-Europe and Transgender Europe have produced statements on “safe countries of origin” lists and called for their withdrawal, this issue has not become central to the agenda of either organization; and an alternative coalition has not been built on this subject.

It should not be inferred, however, that the LGBTI+ asylum organizations interviewed are indifferent to EU politics: on the contrary, they are very present in transnational networks and they all had an opinion on European integration. The production of a counter-narrative on safety also relies on cooperation processes that transcend national borders, including between activists from countries that are loosely connected in other respects. Yet paradoxically, even though this alternative discourse on “safe countries of origin” and “safety” is becoming increasingly Europeanized due to information sharing, it is still largely rooted at the local level.

Cefaï (2016) argues that “a collective mobilization emerges when the members of a collectivity... feel concerned about, directly or indirectly, a ‘trouble’ which they are confronted with..., define it as a problematic situation and decide to take action” (Cefaï, 2016, p. 28–29). Troubles do not naturally become issues to act on: such change happens only when people or organizations “engender a collective experience field, with ways of seeing, saying and making sense in common, articulated by a network of available numbers, categories, types, discourses and arguments” (Cefaï, 2016, p. 31). Absolutely crucial in this process is the travail du sens (“making sense work”), which fixes objectives and paths to attain them.

Yet in the case of the notion of “safe country of origin,” this “making sense together” is still embryonic among organizations supporting LGBTI+ asylum seekers, which favor their local anchoring over their European connections. The idea that asylum is a sovereign issue and that governments would never transfer this competence to the EU was pervasive in interviews. Despite their involvement in European networks, many organizations were unaware of or uninterested in the CEAS reform, and most were not aware of the EU's intention to develop a list of “safe countries.” Many of those interested in the reform described experiencing feelings of discouragement linked to the perception that the EU is much more difficult to access.

The absence of a conception of the EU as a possible “common objective” also derives from the fact that many of the organizations interviewed viewed the EU in “normative” terms (“human rights are important to the EU”) rather than in “strategic” terms (“the CEAS does this”). As a consequence, the less an organization knew about the EU's workings, the more enthusiastically Europhile it tended to be. In contrast, organizations specialized exclusively in LGBTI+ asylum and with a good knowledge of the EU tended to have a more critical approach. It is possible that this dynamic explains the failure of local organizations to access the EU level, since the most knowledgeable organizations are also those most prone to critiquing EU action. This could lead to a misfit between these organizations and EU-level coalitions and discourage their involvement at the EU level.

If this counter-discourse on the notion of “safety” is becoming increasingly Europeanized, it does not entail a move toward EU institutions. The Europeanization process these organizations are undergoing is also quite superficial: it mostly involves sharing pieces of information without connecting them together. This absence of a real overview of “safe countries of origin” lists in the EU is particularly problematic in the construction of a common advocacy: with no fixed objectives, no fixed path, and no real sense of collective experience (even though, paradoxically, such collective experience does exist), any common advocacy at the EU level appears unlikely. The pan-European network developed by LGBTI+ asylum organizations is therefore loosely bound rather than tightly structured; and Europeanization takes place “from below to below,” simultaneously bypassing and neglecting EU institutions. This Europeanization of discourses on “safety” and “safe countries” does not reflect a conscious will to impact EU policies: Europe, here, is a tool and not an end; and harmonization is only a collateral effect.

Conclusion

This article has shown that LGBTI+ asylum seekers are particularly negatively affected by the tightening of asylum policies and by “safe country of origin” practices, therefore calling into question the hypothesis of a homonationalist turn in EU asylum policies.

The negative effect of “safe country of origin” practices on LGBTI+ asylum seekers is not compensated by new claims of gender-sensitivity. Indeed, the implementation of gender-sensitive safeguards overlooks the multifaceted nature of “safe country of origin” practices. “Safe country of origin” lists are only the visible face of a larger phenomenon of refusals based on nationality. Informal presumptions of safety based on nationality permeate asylum systems, leading to a whole range of informal practices that, in effect, result in ex ante refusals of asylum claims. The officialization of “safe country of origin” lists grants symbolic legitimacy to these practices and thereby reinforces them. LGBTI+ claimants are particularly affected, as “safe country of origin” aggregates the situation of all nationals from the same country, obscuring the situations of minorities. Furthermore, this climate of suspicion legitimizes refusals based on prejudices or political considerations.

In this context, gender-sensitive safeguards appear to be limited instruments, as they leave responsibility for mitigating harsh policies to asylum officials. In reality, LGBTI+ claims are generally fast-tracked even when they should not be. “Safe country of origin” practices thus place an unfair burden on LGBTI+ people since their situations are ignored when “safe country of origin” lists are established. Consequently, they are often deemed “safe” and, when they arrive in Europe, they are assumed to be lying and their claims are summarily rejected.

This article has further shown that the proposed recast of the Procedures Directive does not reflect a meaningful change in the way gender is conceived in relation to security, but rather reflects continuity. Despite the claim that the concept of “safe country” is approached in a gender-sensitive manner, the security-oriented logic of asylum rejections remains unchallenged. The gender-sensitization of “safety” should not be mistaken for that of “security.” The European Commission 2015 Explanatory Note for the Proposal for a Regulation establishing a common EU list of “safe countries of origin” clarifies the continuity with traditional conceptions of the place of LGBTI+ people in the political community. Indeed, the presence of violence against LGBTI+ people in all of the countries on the proposed list is explicitly acknowledged, but it is considered to be insufficient to overturn the presumption of “safety” in the countries listed. By doing so, the Explanatory Note normalizes the existence of violence against LGBTI+ people and depicts them as undeserving of equal protection, not only in their countries but also under the CEAS.

Is the EU doomed to fail LGBTI+ asylum seekers? Not necessarily. Through the existence of the CEAS, the EU has been an important normative actor in enhancing the protection of LGBTI+ asylum seekers in Member States. European integration has also benefited local organizations, which have developed horizontal networks allowing them to produce a harmonized counter-discourse on “safety” and “safe countries.” Nonetheless, this counter-discourse on safety is still largely rooted at the local level, and it has not resulted in the building of a common EU-level advocacy. EU institutions must therefore take responsibility if they are serious about protecting LGBTI+ asylum seekers. Indeed, for LGBTI+ rights to be respected, non-binding incentives to adopt a gender-sensitive approach are not sufficient. Women and LGBTI+ people have long been excluded from the definition of the political community, and it is unlikely that mere encouragements to “take them into account” will be enough to remedy these deeply ingrained representations. This means not only critically analyzing existing policies, but also accepting that some concepts are inherently problematic and are not compatible with gender equality or LGBTI+ rights. This is the case for the concept of “safe country of origin.”

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because it is part of an unfinished research project and contains sensitive information. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to amandine.lebellec@unitn.it.

Ethics Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

AL has done the research, data analysis, and redaction of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This publication has benefited from the support of Sciences Po Paris research group on Migration and Diversity (MiDi). The author would therefore like to thank both MiDi for their financial help, and Rachel Robertson for her careful editing.

Footnotes

1. ^The Asylum in Europe Database Provides Annual Reports on the Situation of Asylum Seekers in 23 European Countries. Available online at: https://asylumineurope.org/reports/ (accessed February 16, 2021).

2. ^Official Data From the 2019 Report Published by the French Office for the Protection of Refugees and Stateless Persons, the Institution in Charge of Assessing Refugee Claims in France. Available online at: https://ofpra.gouv.fr/sites/default/files/atoms/files/rapport_dactivite_2019.pdf (accessed February 16, 2021).

3. ^For example, the Istanbul Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence (2011) states that Parties may extend the obligation of gender-sensitivity in asylum to LGBT individuals (Explanatory Memorandum on Art. 60, par. 317). In order to emphasize these slippages and the way LGBTI+ protection occurs partly through “gender” categories, this article uses the term “gender-sensitive” as inclusive of LGBTI+ people.

4. ^In Sweden there is no list of “safe countries of origin” in force, but some nationalities (mostly Western Balkans) are fast-tracked. In Spain, the concept is enshrined in the legislation but with no widespread use. In Slovenia there is a list, but little difference is made between accelerated and normal procedures. In Cyprus, the list is supposed to be based on an EU common list to which Georgia is added.

5. ^The documents analyzed include EU legislation (Procedures Directive, 2013 recast, 2015 Proposal for a Regulation for a EU common list, 2016 Proposal for a Procedures Regulation), reports and opinions coming from the European Parliament and the European Council, and press releases from NGOs.

6. ^The interviews were semi-structured, lasted around one hour and were conducted by phone. Consent for recording was systematically requested, and all quotes presented in this article were proofread by the interviewees. When requested, anonymity was granted (names with an asterisk*).

7. ^Interviews were conducted with organizations based in the following countries: Austria [1], Belgium [2], Cyprus [1], Denmark [2], Finland [1], France [2], Germany [3], Greece [3], Ireland [1], Italy [5], Malta [1], Norway [1], Portugal [1], Slovenia [1], and the UK [2]. This list includes Member States at the time of the study plus Norway, which applies part of the CEAS.

8. ^The organizations interviewed were eclectic in their profiles: most deployed a wide range of activities (support throughout the asylum application procedure, social events, advocacy, psychosocial support), with very few organizations having a single focus (such as litigation or advocacy).

9. ^The European Network on Migration (EMN) cites the Netherlands as considering several countries, such as Algeria or Senegal, to be “safe except for LGBTI”.

10. ^See the ERA Online Resource Center. Available online at: https://www.lgbti-era.org/online-resource-center (accessed January 22, 2021).

11. ^See for example the ARDHIS, “Aucun pays n'est sûr”. Available online at: https://ardhis.org/aucun-pays-nest-sur/ (accessed January 23, 2021).

12. ^The Dublin III Regulation establishes which country is responsible for the assessment of an asylum claim. This is generally the country of arrival of the asylum seeker, even though exceptions can be made. When asylum seekers seek to go to another country (for example, because they have family there, or because they fear that their asylum claim will not be fairly assessed), the authorities may send them back to their country of arrival.

13. ^In 2015, the EU Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA) reported that in at least 21 Member States, corrective “normalizing” surgeries (which are generally denounced as invasive procedures by intersex organizations) were carried out on children; and that in eight Member States, this could be done without the consent of the child. Link to the FRA report. Available online at: https://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra-2015-focus-04-intersex.pdf (accessed February 16, 2021).

14. ^Organizations supporting LGBTI+ asylum seekers are usually critical of the migration policies implemented in their country, but may relate to the authorities in very different ways. Some have built a relationship of trust with asylum offices and use it as a way to lobby for LGBTI+ asylum seekers' rights, therefore displaying a consensual façade (“respectability-oriented” organizations), while others refuse any form of cooperation and may advocate for the abolition of borders (“no-border” organizations). Most organizations are located on the continuum between these two poles, but entirely no-border organizations seem to be rarer in European networks.

References

AIDA (2020). Reports 2020 | Asylum Information Database. Available online at: https://www.asylumineurope.org/reports

Andrade, V., Danisi, C., Dustin, M., Ferreira, N., and Held, N. (2020). Queering Asylum in Europe: A Survey Report. Sussex. Available online at: https://www.sogica.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/The-SOGICA-surveys-report_1-July-2020-1.pdf

ARDHIS (2020). Rapport d'Activité 2019. Paris. Available online at: https://ardhis.org/sur-lardhis/

Atak, I. (2018). Safe country of origin: constructing the irregularity of asylum seekers in Canada. Int. Migrat. 56, 176–190. doi: 10.1111/imig.12450

Bigo, D. (1998). “L'Europe de La sécurité intérieure: penser autrement la sécurité,” in Entre Union et Nations. L'Etat En Europe, ed A.-M. Le Gloannec (Paris: Presses de Sciences Po), 55–90.

Bohmer, C., and Shuman, A. (2018). Political Asylum Deceptions. The Culture of Suspicion. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bracke, S. (2012). From “Saving Women” to “Saving Gays”: rescue narratives and their dis/continuities. Eur. J. Women's Stud. 19, 237–252. doi: 10.1177/1350506811435032

Cefaï, D. (2016). Publics, problèmes publics, arènes publiques. Que nous apprend le pragmatisme?' Quest. Commun. 30, 25–64. doi: 10.4000/questionsdecommunication.10704

Costello, C. (2005). The asylum procedures directive and the proliferation of safe country practices: deterrence, deflection and the dismantling of international protection. Eur. J. Migrat. Law 7, 35–70. doi: 10.1163/1571816054396842

Costello, C., and Hancox, E. (2015). “The Recast Asylum Procedures Directive 2013/32/EU: caught between the stereotypes of the abusive asylum seeker and the vulnerable refugee,” in Reforming the Common European Asylum System: The New European Refugee Law, eds V. Chetail, P. De Bruycker, and F. Maiani (Boston, MA: Brill Nijhoff), 375–445.

Engelmann, C. (2014). Convergence against the odds: the development of safe country of origin policies in EU member states (1990-2013). Eur. J. Migrat. Law 16, 277–302. doi: 10.1163/15718166-12342056