94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Hum. Dyn., 05 February 2021

Sec. Dynamics of Migration and (Im)Mobility

Volume 3 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fhumd.2021.613792

This article is part of the Research TopicGender, Violence and Forced MigrationView all 8 articles

Rebecca Horn1*

Rebecca Horn1* Karin Wachter2

Karin Wachter2 Elsa A. Friis-Healy3

Elsa A. Friis-Healy3 Sophia Wanjku Ngugi4

Sophia Wanjku Ngugi4 Joanne Creighton5

Joanne Creighton5 Eve S. Puffer6,7

Eve S. Puffer6,7Armed conflict and forced migration are associated with an increase in intimate partner violence (IPV) against women. Yet as risks of IPV intensify, familiar options for seeking help dissipate as families and communities disperse and seek refuge in a foreign country. The reconfiguration of family and community systems, coupled with the presence of local and international humanitarian actors, introduces significant changes to IPV response pathways. Drawing from intensive fieldwork, this article examines response options available to women seeking help for IPV in refugee camps against the backdrop of efforts to localize humanitarian assistance. This study employed a qualitative approach to study responses to IPV in three refugee camps: Ajuong Thok (South Sudan), Dadaab (Kenya), and Domiz (Iraqi Kurdistan). In each location, data collection activities were conducted with women survivors of IPV, members of the general refugee community, refugee leaders, and service providers. The sample included 284 individuals. Employing visual mapping techniques, analysis of data from these varied sources described help seeking and response pathways in the three camps, and the ways in which women engaged with various systems. The analysis revealed distinct pathways for seeking help in the camps, with several similarities across contexts. Women in all three locations often “persevered” in an abusive partnership for extended periods before seeking help. When women did seek help, it was predominantly with family members initially, and then community-based mechanisms. Across camps, participants typically viewed engaging formal IPV responses as a last resort. Differences between camp settings highlighted the importance of understanding complex informal systems, and the availability of organizational responses, which influenced the sequence and speed with which formal systems were engaged. The findings indicate that key factors in bridging formal and community-based systems in responding to IPV in refugee camps include listening to women and understanding their priorities, recognizing the importance of women in camps maintaining life-sustaining connections with their families and communities, engaging communities in transformative change, and shifting power and resources to local women-led organizations.

Intimate partner violence (IPV), defined by a pattern of abusive and controlling behaviors, is one of the most common manifestations of violence against women worldwide (World Health Organization, 2013). Armed conflict and forced migration exacerbate risks of violence, abuse, and exploitation of women and girls, including IPV (Usta and Singh, 2015; Freedman, 2016). The destabilizing impact of displacement on individuals, families, and communities can further intensify conditions in which men continue to abuse their female partners or use violence for the first time (Usta and Singh, 2015). Impacts of armed conflict and displacement on communities include severe losses of social connections and erosion of trust (Strang et al., 2020), plus the potential for hostility in newly formed communities and competition over limited resources and services, all of which disproportionately affect women. Other drivers of IPV in displacement settings include the reinforcement and disruption of gender norms and roles such as men being unable to provide for the family whilst women begin to engage in income-generating activities; men’s substance use; separation from family; and rapid remarriages and forced marriages (Horn, 2010a; Wachter et al., 2019a). Findings from a study in two Congolese refugee camps in Rwanda suggest that women who had experienced violence from someone not known to them were at greater risk of IPV (Wako et al., 2015).

In refugee camps and other contexts of displacement, women face significant challenges seeking help for IPV. Displacement limits women’s access to informal networks of support, including extended family, which may have formerly played a protective and/or supportive role (Wachter et al., 2019a). Restrictions on mobility among all refugees have particular implications for women and girls (UN Women, 2018), limiting women’s ability to leave abusive relationships and seek help for IPV in new contexts. Community dynamics and structures in displacement often differ from pre-displacement mechanisms, obscuring familiar pathways to help and assistance (Horn, 2010b). Prior to displacement, volunteers and other civil society actors may have worked with existing women-led organizations and IPV service providers, and served an important role in helping women access help; yet, these mechanisms may not survive the onset of a crisis or function as they previously had in displacement, thereby creating fissures in reporting avenues. In other contexts, formal services and referral mechanisms for women experiencing IPV may have never existed. The cumulative consequences of displacement raise important questions around how women navigate IPV help seeking in contexts of displacement.

Across contexts—both in displacement and non-displacement settings—women who experience IPV primarily turn overwhelmingly to informal sources of support (i.e., family, friends, and community) for help (Garcia-Moreno et al., 2005; Andersson et al., 2007; Abramsky et al., 2010; Barrett and Pierre, 2011; Sylaska and Edwards, 2014). Informal responses available through interpersonal social networks are important for myriad reasons, and can mitigate negative consequences of IPV and promote better mental health (Coker et al., 2003). While shared aversions to formal services appear to cut across contexts, evidence suggests that women are more likely to seek help from formal sources as IPV becomes more severe and they begin to fear for their lives and/or their children’s safety (Fugate et al., 2005; Naved et al., 2006; Ergöçmen et al., 2013).

It is likely that only a small percentage of survivors in displacement settings report IPV to a formal institution (Horn, 2010b; Al-Natour et al., 2018). Women are often reluctant to disclose the violence they face at home due to complex and gendered social pressures and stigmatizing and victim-blaming forces (Kennedy and Prock, 2018; Strang et al., 2020). Displaced women may be especially conscious of the potentially serious economic and social consequences of disclosing IPV (Horn, 2010b; Al-Natour et al., 2018; Strang et al., 2020). The lack of economic opportunities for women to meet their own and their children’s basic needs are strong factors hindering women from seeking formal help (Vyas and Watts, 2009). These barriers to disclosure and seeking help, among others, may contribute to the preference commonly expressed by displaced and conflict-affected women to stay with abusive partners (Wirtz et al., 2014; Al-Natour et al., 2018). Given the precariousness of life in displacement, the potential consequences of disclosing IPV may be too high a risk for women, even at the expense of their personal safety (Al-Natour et al., 2018; Strang et al., 2020).

Previous research has elucidated patterns of family and community responses to help seeking in refugee camps. Research conducted in specific camp settings (i.e., Uganda) has highlighted preferences for addressing a wide range of disputes within the family (Vancluysen and Ingelaere, 2020) as people may attach more legitimacy to family and community mechanisms than formal services (Wessells, 2015). This has also been found to be the case in relation to IPV, where camp residents have described a “hierarchy of responses,” with family and community actors as the first option and international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) and the police at the “top” (Horn, 2010b). Rather, women experiencing IPV and their families may perceive help from existing community mechanisms as working in the best interest of families involved, and are therefore less threatening than external intervention. Whilst community mechanisms can be an important resource, traditional community mechanisms may be male-dominated, uphold patriarchal values, and on that basis prioritize family and community over the safety and wellbeing of individual women (da Costa, 2006; Horn, 2010b; Vancluysen and Ingelaere, 2020). Safety is a fundamental issue for women when informal traditional mechanisms may further punish them by issuing sanctions, such as a fine, that may force her to engage in negative coping strategies, such as reduced food intake or risky employment. Within a broader context of disenfranchisement, community-based leadership structures in camp settings may use their power to work in the interest of some at the expense of others.

Formal IPV services in refugee camps are part of a larger set of programming focused on gender-based violence (GBV) prevention and response implemented via the humanitarian infrastructure. Safe spaces for women and girls often function as the basis for delivering a wide range of GBV programming in humanitarian settings (Megevand and Marchesini, 2020). These are designated spaces where women and girls can safely seek, share, and access information and services, and enhance their overall psychosocial well-being. Services for women and girls who have experienced GBV, inclusive of IPV, non-partner sexual assault and rape, and early/forced marriage (among other forms), are grounded in a comprehensive case management approach, which aims to foster positive health, safety, and psychosocial outcomes among survivors (Interagency GBV Case Management Guidelines, 2017). This approach is rooted in survivor-centred principles that seek to ensure women and girls drive decisions around their safety planning and healing, and caseworkers enable and support their decision (Interagency GBV Case Management Guidelines, 2017). Other facilities in camp settings, such as health clinics and livelihood centers, often deliver additional IPV-related services. By virtue of a task-sharing model, refugee community workers often take on the role of bridging formal reporting mechanisms and community responses to IPV (Hossain et al., 2018). This may include outreach efforts seek to raise awareness of available services which may include economic empowerment interventions, skill-building opportunities, and access to legal advice and cash assistance. Additionally, outreach workers seek to increase community acceptance of programming for women and girls, and reduce stigma and barriers associated with seeking help.

Empirical research that provides an in-depth understanding of women’s experiences of IPV, and the responses of community and formal mechanisms, is integral to informing policy and practice that reflects broader efforts to transform aspects of humanitarian assistance. While there have been advances in research to support initiatives to address IPV in low- and middle-income settings, efforts have largely overlooked refugee camp settings. This analysis therefore examined these issues in three distinct refugee camps. Our analysis sought to answer the following research questions: How and from whom do women seek help for IPV? How do community-based mechanisms and formal services respond to women’s requests for help with IPV? To answer these questions, our analysis generated visual maps of the ways in which women navigate existing options in each context—a method we believe could be useful for developing and implementing IPV responses across specific contexts.

Despite a growing urbanization of displacement, 39% of the 2.4 million refugees and 41.4 million internally displaced people at the end of 2018 (UNHCR, 2019) still lived in camps or formal settlements. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) manages most refugee camps. One or more national and/or international NGOs, alongside state providers in some settings, deliver sector-specific services related to shelter, food security, health, water and sanitation, education, child protection, and GBV, among other programs.

This study used qualitative methods to study options and responses to IPV in three refugee camps: 1) Ajuong Thok camp in South Sudan, 2) Hagadera (Dadaab) camp in Kenya, and 3) Domiz camp in the Kurdistan region of Iraq (Table 1). Researchers conducted the study in 2014 with the International Rescue Committee (IRC), which has an extensive history of responding to GBV in humanitarian settings.

Three institutional review boards oversaw the study: Duke University Institutional Review Board, the Kenya Medical Research Institute, and the Ministry of Health in Iraq. At the time, there was no ethical review board to seek approval from in South Sudan. Due to the significant ethical considerations involved in this research, the safety and wellbeing of participants was a priority, particularly among those who identified as survivors of IPV. The research was planned and conducted in accordance with established guidelines for conducting violence against women research at the time (World Health Organization, 2001; Ellsberg and Heise, 2005). A comprehensive set of ethical and safety guidelines were developed for this project, which addressed the research design, community consent, selection and recruitment of participants, informed consent, confidentiality, ethical checks during the course of the data collection and afterward, referrals and providing further support, and reporting procedures.

All interviews with survivors were conducted in a safe and private location identified by IRC staff in collaboration with the community and research participants. If someone not involved in the research interrupted interviews with survivors in process, the researcher immediately changed the topic from IPV to another subject (e.g., food intake), as a means of protecting the participant. No written records were kept of names or other identifying information. Furthermore, IPV survivors had access to trained case managers and counselors and received information about relevant services available in the camp.

Using a nonprobability purposive sampling strategy, we recruited four groups of study participants: 1) IPV survivors, 2) community members of the general refugee population, 3) community leaders within the camp, and 4) formal service providers. In each research site, a community advisory group (CAG), comprised of community members and service providers, contributed to adapting data collection strategies and assisted with recruitment.

Individual interviews with survivors were particularly sensitive in relation to selection and recruitment, especially given that we recruited both survivors who had reported to IRC and those who had not. For those who had reported to IRC, potential participants were selected from the IRC client database by the IRC caseworkers working in each location. These included both current and former clients. The caseworker responsible then approached the client to ask if she would be willing to participate in the study, using a pre-designed script, and if willing, the caseworker arranged for the interview to be conducted at a time and location that was safe for the client.

Survivors who had not reported to the IRC were recruited by members of the CAG who were working and/or living in the refugee camp, and knew of women living with IPV who had not reported. Where it was safe and appropriate to do so, CAG members approached the survivor to describe the study and asked whether she had interest in participating, using an IRB-approved script. If the survivor agreed, the CAG member informed the IRC field team, who arranged for the survivor to meet with the researcher. Field staff and CAGs recruited all other refugee participants, with the goal of including a broad spectrum of identities and voices. Field staff recruited key informants, which included refugee leaders and formal service providers, representing various sectors of humanitarian intervention (e.g., education, health, law enforcement, community services, camp management, GBV, and child protection). While no honorariums were offered to the study participants, refreshments were offered to group discussion participants.

A total of 284 individuals participated in the study across the three camps: adult women who experienced IPV (n = 39), refugee community members (n = 169) and leaders (n = 43), and service providers (n = 33). The age range of women who had experienced IPV was 18–46 years old. They reported having resided in the camps from 3 months to 23 years, a range length of marriage from 2 months to 28 years, and having between 0 and 14 children. Refugee community members and leaders ranged in age from 18–75 years.

The first author served as the lead field researcher and collected all data in Ajuong Thok and Domiz with the assistance of language interpreters. In Hagadera, due to security issues at the time, field staff collected data with training and guidance from the field researcher. Data collection methods included individual interviews, group discussions, and key informant interviews.

Individual interviews with IPV survivors explored whom they told about their partners’ behavior since arriving to the camp and how these actors responded. Depending on responses, follow-up questions included: how they chose who to disclose to and when, what they hoped these actors would do and what they actually did, the outcomes of disclosure or interventions (immediately and longer term) and how she felt about those outcomes. Survivors were also asked their opinions of the options available to them.

Focus group discussions (FGDs) with community members explored context-specific drivers of IPV and response options available to survivors. A functional mapping activity was conducted with each group of the networks of support available to women experiencing IPV in that location. The facilitator presented groups with a scenario developed for that context and posed a series of questions designed to explore sources of available help and steps typically taken by a woman experiencing IPV and other relevant actors. Issues explored included: who would be involved in making decisions, the likely outcomes of responses (for the woman, her husband and their children), the level of satisfaction of different stakeholders with those outcomes, and which other alternatives might have been available and why they were not utilized. This process generated existing pathways of responses to IPV.

Key informant interviews with refugee leaders focused on the differences between pre- and post-displacement in terms of the causes, effects and responses to IPV, and exploration of current response options in the camp. Key informant interviews with representatives of formal service-providers in the camp focused on IPV response options, including perceived strengths, weaknesses, barriers and challenges.

The first author conducted an initial analysis of the data in the field to identify preliminary themes (Braun and Clarke, 2006) and summarize key findings. To develop the response pathways presented in this paper, the functional maps developed during group discussions in each camp, together with data from interviews with IPV survivors, were combined into an aggregate response pathway for that camp. The consolidated “maps” were then shared in debriefing sessions with refugee leaders and representatives of humanitarian agencies in each camp. These sessions allowed the researcher to ask for clarification of any discrepancies and provided stakeholders the opportunity to correct any misunderstandings and give further information (Creswell, 2013). The researcher updated each of the “maps” based on these discussions before leaving the field site. In addition to the preliminary “maps,” the field-based data analysis process produced a preliminary codebook, which a four-person team (including the field researcher) further refined following the completion of all data collection activities. This team used an on-line analysis software platform, Dedoose, to develop the final coding scheme, facilitate collaboration across multiple coders, and code all of the data. This process also allowed the team to refine and finalize the response pathways figures, presented below. In alignment with standards for rigor in qualitative data analysis (Creswell, 2013), the team first coded a set of the same transcripts and discussed discrepancies to agree on interpretation and application of the codes before coding independently. Team meetings were also held regularly to discuss analytical procedures, queries, and emergent ideas (Padgett, 2008). The team also detailed all analytical decision-making in an audit trail (Rodgers and Cowles, 1993). Lastly, the team worked closely with field practitioners in reviewing the final analyses and considering implications for policy, practice, and research.

The analysis identified IPV response pathways, which include women’s responses to IPV, and community-based and formal responses to women’s experiences of IPV as described at the time of data collection. These pathways, depicted visually and explained in the text by camp setting, form the basis of the findings. Three figures reflect results of the functional mapping activity and the broader qualitative analysis by camp. It is important to note that the models do not represent a linear pathway or process; many survivors described interacting with options in various ways including repeating an option or only engaging with a small subset of options. Rather, models outline existing and possible care seeking pathways in each setting. Across the camps, three key thematic pathways emerged: 1) staying and persevering, 2) crisis intervention during or after an incidence of violence, and 3) seeking non-crisis help. Across all camps women noted staying and persevering was the most common option. Differences and similarities in IPV response pathways between camps are discussed throughout.

The most commonly described pathway in Ajuong Thok was “persevering” within an abusive relationship for a long time before seeking help or would never disclosing the abuse. Many women described how they searched for strategies that would enable them to remain in the relationship such as trying to contribute to the family income, not responding when their husband tries to start a quarrel, or carrying out their responsibilities within the home in ways they believed would reduce the likelihood of violence. Others hoped that the husband would spontaneously change his behavior.

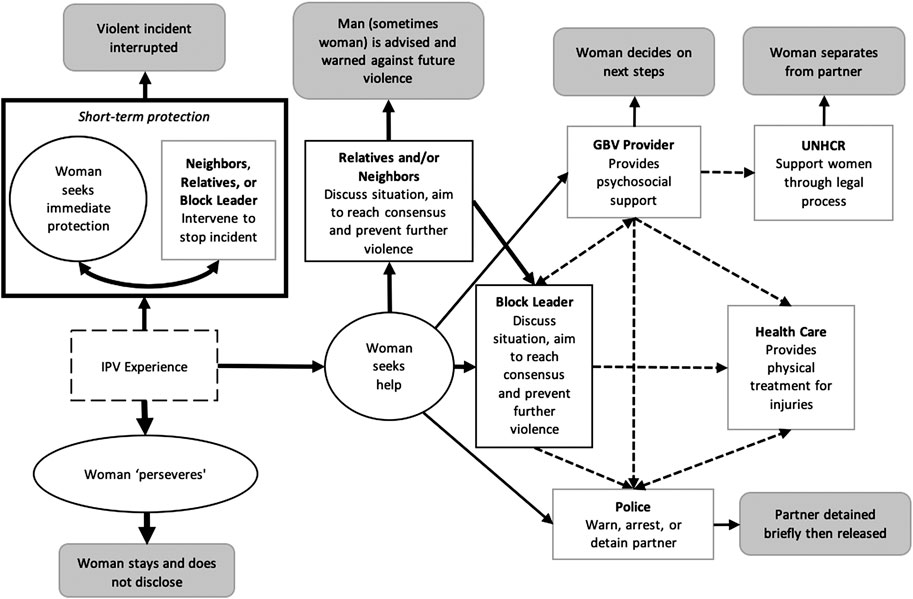

In the short term, women sometimes sought assistance from neighbors and, on occasion, neighbors, relatives and might independently intervene in crisis situations. In addition, some participants noted women may report directly to the international GBV provider or the police after an incident for protection. As highlighted in Figure 1, this process was bi-directional typically leading to the violent incident being interrupted, offering short term protection.

FIGURE 1. Pathways of responding to Intimate partner violence (IPV) in Ajuong, Thok. This model does not represent a linear process; survivors may interact with the options in various ways including repeating one option several times. Solid lines denote help-seeking pathways, dashed lines are utilized to denote referral pathways, and darker grey boxes are used to denote most likely “outcomes” of seeking each type of assistance.

In Ajuong Thok there were several longer-term response pathways. First, participants perceived a woman’s parents and her husband’s parents to be best placed to assist, but for most women, their parents were not in Ajuong Thok. In their absence, neighbors played a key role in the response. The first step of a response was often for a group of relatives and neighbors to meet with the couple with the aim of identifying and resolving the problem, deciding who was at fault and advising or warning that person to change their behavior so the couple could live together “peacefully.” However, neighbors and extended family tended not to be afforded the same respect that parents would be, so their advice was less likely to be heeded by an abusive partner.

As noted in Figure 1, a woman might seek help directly from the block leader or the couple’s family or neighbors may seek assistance from the block leader, which was the most frequently described formal pathway for seeking non-crisis assistance. Block leaders were mainly men and had the power to decide who was at fault, to advise and warn, and refer to other actors including the police or GBV provider, or assist in ensuring the woman received appropriate medical attention (Figure 1 dashed pathways). However, block leaders could not fine the perpetrator or decide that the couple should divorce. In general, while reporting to the block leader was officially the system one should follow, participants noted mixed opinions of its effectiveness. If the husband was unwilling to listen to block leader’s advice, there was little the block leader could do to assist the woman other than report the issue to the camp chairperson (effectively the coordinator of the block leaders), who would repeat the process of discussion but had no additional powers. Notably, participants did not report religious leaders having a significant role in advising a perpetrator or actively engaging in the response to IPV, although they offered emotional and spiritual support to affected women.

Women could independently seek additional help from the police or GBV providers. However, this was much less common than approaching family members or the block leaders. The block leader could also refer women to additional services including the GBV provider, police or a healthcare provider. As noted by the multiple dashed lines in Figure 1 between these additional actors, service providers could also refer to the woman to a number of additional actors. Notably, the GBV provider appeared to be the only actor that would reliably refer women to UNHCR, with her informed consent, and women reported very limited direct access to healthcare.

If the case was reported to the police, whether by the block leader or (less commonly) by the woman herself, the police might arrest the man and keep him in their cells for a few days. The block leader would return to talk to the man and once he “accepted his mistake,” he would usually be released and return home. Women tended not to see reporting to the police as a helpful option. They did not believe the police would detain their husbands long enough for a woman to take meaningful action (e.g., leaving or otherwise resolving the situation), which could potentially increase her risk. As one woman explained, I’ve seen many times, when the wife reports to the police, the man is taken there (to the police), but he does not spend the night there. Sometimes he pays money and he’s released the same day, which is really very dangerous. Because when a woman reports and the husband is captured and he doesn’t even spend some hours there, he comes back and he can take revenge for what the woman did. He can even kill her (IPV survivor, Ajuong Thok).

When women reported to the police, they usually did not want their husbands imprisoned for a lengthy period or taken to court. Rather, they wanted the police to frighten them into changing their behaviors, as a warning that if they use violence against, they would be arrested and tried in court.

The international GBV provider often became involved later in the process. Block leaders had the option to refer the case to the GBV provider when they were unable to find a solution themselves (typically when men refused to accept their authority). Additionally, women sometimes went directly to the GBV provider, but this tended to be a last resort when all other options had failed, when they had no confidence in the block leader, or when they were in fear for their lives. When contacted, the GBV provider would meet with the woman and support her in deciding which course of action she wanted to take. This may include seeking additional support from other actors (e.g., police, UNHCR, family members) or not taking any further steps. In addition to providing direct support, the GBV provider could refer the woman to the police, health-care providers, and/or UNHCR, depending on the needs and choices of the individual. The UNHCR provided support around a woman formally separating from her husband and was the only actor that could separate the woman’s ration card from her husband’s (necessary for her to obtain food in the camp), and allocate her with a separate shelter.

Community members, both male and female, generally disapproved of reporting to the international GBV provider, and saw it as a last resort when all other options have been unsuccessful. They wanted the international GBV provider to use the same process of calling all parties together to discuss, mediate and warn; they were unhappy with the practice of the GBV provider meeting with the woman alone. As a participant in a discussion with men reported, “If somebody goes to report … (the agency) is supposed to tell them to come and call the elder and block leader so they can solve the case, but now they just go and solve that case without calling them, which is not really good” (Ajuong Thok). Community disapproval spurred wariness amongst women of reporting to the GBV provider. A woman who had disclosed IPV shared, “There are a lot of questions when you tell somebody that they have reported. They will ask you why did you decide to report and what did you do there? A lot of questions.” (Ajuong Thok).

Finally, additional options to women experiencing IPV, which had been available in Nuba Mountains, did not exist in Ajuong Thok. In order to divorce, it was necessary for the parents of both parties to come to agreement on bride price and other issues. In many cases, this would require the couple to return to Nuba Mountains, which was not possible for most since the conflict was ongoing. As a result, there was no resolution in the most serious cases of IPV. In addition, typical short-term resolution options were limited including returning temporarily to their parents while the situation was addressed. In the camp, separation was the preferred option for women who were in chronic and intractable IPV situations, although it was not necessarily how women wanted their lives to be, nor was this course of action without risk. Women usually did not want a formal divorce because this would require them to leave their children with the man, but they felt that living separately from their husband would allow them to live in peace.

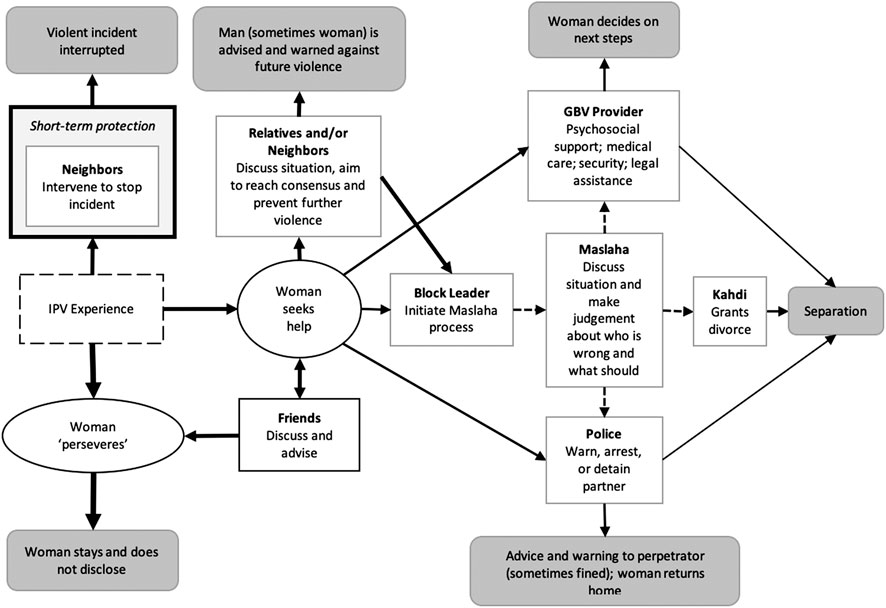

In Hagadera (Figure 2), like Ajuong Thok, women generally did not tell people about the abuse, but would identify and implement strategies designed to reduce the violence, and would “be patient,” as the women themselves described their strategy. Non-crisis help-seeking in Hagadera most typically consisted of a woman disclosing IPV to friends and family members or neighbors, unless she had already decided that she wanted to separate from her husband in which case she may report directly to the police or GBV provider. Friends were likely to give emotional support and advice, and the woman would then decide on a course of action, which could include not disclosing to anyone else or seeking help through other pathways.

FIGURE 2. Pathways of responding to IPV in Hagadera, Dadaab. This model does not represent a linear process; survivors may interact with the options in various ways including repeating one option several times. Solid lines denote help-seeking pathways, dashed lines are utilized to denote referral pathways, and darker grey boxes are used to denote most likely “outcomes” of seeking each type of assistance.

In the short term, when neighbors would overhear a violent incident, they would sometimes intervene spontaneously to protect the woman. Some IPV survivors in Hagadera described neighbors as very helpful, for practical protection, assistance, and emotional support. However, in a number of cases, neighbors were said to have become “tired” of the situation after it continued for a long period of time without their efforts having any effect, and they stopped intervening. In comparison to Ajuong Thok, women did not actively seek protection from neighbors.

Regarding longer-term response pathways, similar to Ajuong Thok, relatives and neighbors might meet together with the husband and the wife, and try to mediate. Family members would “counsel” or advise both parties, in an attempt to prevent the violence from recurring. In most cases, the advice given aimed to encourage the woman to stay in the marriage and to motivate the man to change his behavior. Parents and relatives of the husband played an important role and, in many cases, were supportive of the abused woman unless she decided to separate from her husband, at which point they tended to withdraw their support. In addition, a unique pathway consisted of women discussing the ongoing challenges with friends, or friends offering emotional support. These conversations may happen before or during other help seeking processes, however, the majority of times participants noted women would stay with an abusive partner and conversations with friends may support emotional coping with abuse.

Block leaders in Dadaab were also seen as important resources for women, although typically families or neighbors tried to resolve the issue on their own first before involving block leaders. When block leaders became involved, they would typically initiate the Maslaha process, which involved calling together elders (usually male only, although this depended on the community) from the couple’s families, and together they discussed the situation and came to a judgment. They decided who was in the wrong, and advised or warned that person; they may also fine the perpetrator if he has offended previously. Once their decision was made, they informed the woman (who was not usually present during proceedings, although the perpetrator was), and she was expected to abide by their decision. In most cases, this was for her to return home with her husband. If she rejected their decision, then she would not have the support of the community in case of future problems. Some women also feared that if they went against the Maslaha decision they would be cursed, which could lead to physical or mental illness, death of self, or death of a child. One woman, so severely beaten by her husband that she miscarried, described the following, I called elders of both sides and I told them all the issues, what happened and they asked, “right now, what do you want?” I told them I need to get a divorce. When the elders went to him, he told them, “I love my wife and I don’t know what caused this problem.”… They come back to me and said “the husband is saying this so what do you want?” And I said that I cannot stay in this camp while I live such a life, I cannot stay, I need to go back to Somalia.…Fortunately, the elders advised me, saying “In Somalia there is no peace. What are you going to do there? Just stay with your husband and be patient for him.” So I took their advice and I decided to stay with him.

The participant went on to say that she was, at present, satisfied with the advice because she would not have known what else to do.

Typically, the Maslaha process would result in the man being advised or warned on the first two occasions. A man would then more likely be punished if his abusive behavior continued, and the Maslaha may decide that the woman could divorce the man. If divorce was agreed upon, the case would be forwarded to the Kadhi (a religious leader), who assessed the evidence and decided whether to grant a divorce or not. At this stage, the Kadhi would invite neighbors, relatives and elders to give evidence, so if the woman had not been through the initial stages of the community-based processes, it would be difficult for her to obtain a divorce because her peers would not support her request. If a divorce was granted, the Kadhi or the elders might refer the case to the police or to mandated agencies for assistance (e.g., security, ration card separation).

In some cases, the Maslaha decided that they were not able to do anything to solve the problem and recused themselves from engaging with the case. Reasons participants gave for this included the husband refusing to accept their authority; the woman being from a minority clan and the husband from a more powerful clan; the Maslaha members feeling unable to handle the situation (e.g., a case where the man had mental health problems) or because they had not succeeded in resolving the issue and had become tired of it. One survivor described feeling that the Maslaha members avoided her for this reason: “When the elders see me, even if I come on the way, they will just escape from me.”

Similar to Ajuong Thok, women rarely reported to the police or the GBV provider directly without going through the community process and when they did, it was usually because they had already decided they wanted to separate from their abusive husband. When this happened, the elders sometimes arranged for the man to be released from the police cells and “take the case back” to the Maslaha system. Where the elders had referred the case to the police, the man might be arrested and detained, and in some cases legal action taken against him. Similarly, some women reported directly to the international GBV provider or another agency, but again, this was usually once they had decided that it was not possible for them to remain in their marriage. Participants shared examples of several cases of elders approaching the GBV provider to “take the case back” and threatening the woman that she would be cursed if she did not withdraw her complaint to the GBV provider and have the case dealt with by the Maslaha system. As noted in Figure 2 by the dashed arrows, elders would occasionally refer a woman to the GBV provider or the police. However, this only occurred when the elders had tried unsuccessfully to resolve the issue or the perpetrator was not abiding by their decisions. Women who did interact with the GBV international provider could receive psychosocial support, medical care, legal assistance or security. Women could then pursue other options previously discussed or continue to persevere in the relationship due to the numerous challenges associated with help seeking.

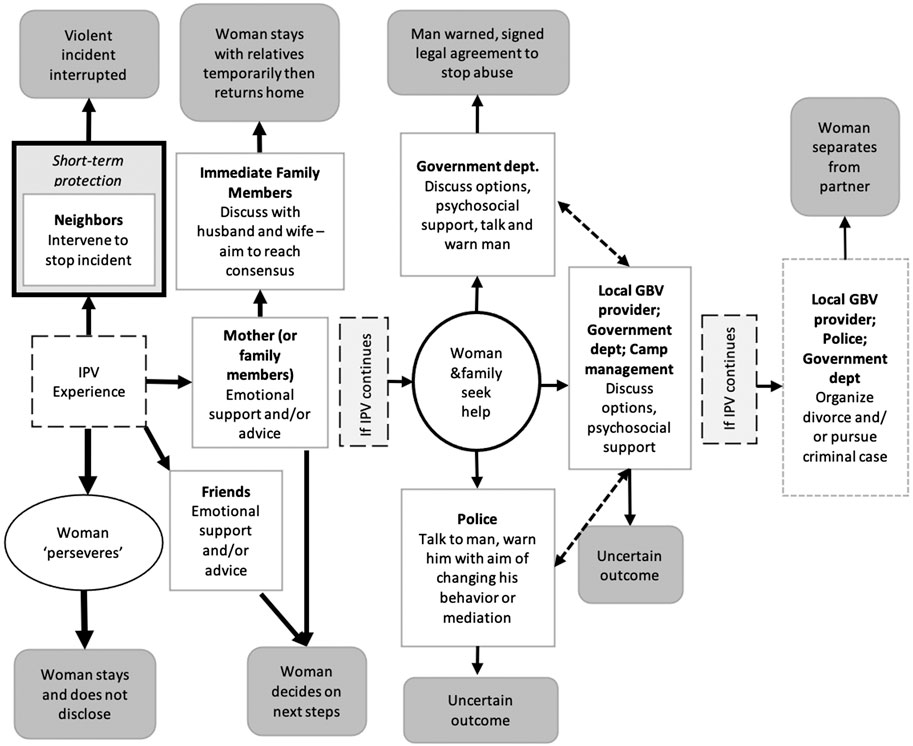

In Domiz (Figure 3), the situation was different from the other two camps, partly because community response systems were less apparent, and partly because there were a number of organizations providing services in the camp to women who experienced IPV and other forms of GBV. Women in Domiz, like in other locations, generally tried to tolerate the abusive situation as long as possible, especially if they had children or been married for a long time. They also “persevered” because they did not want the marriage to fail and felt it would be shameful for people to know about their problems, which would lead to a loss of respect. Women sought strategies to improve the situation by talking to their husbands or by changing their own behavior. Regarding short-term protection, similar to other situations, neighbors may intervene if they witness or overhear conflict, however participants noted trying to keep conflicts to themselves.

FIGURE 3. Pathways of responding to IPV in Domiz. This model does not represent a linear process; survivors may interact with the options in various ways including repeating one option several times. Solid lines denote help-seeking pathways, dashed lines are utilized to denote referral pathways, and darker grey boxes are used to denote most likely “outcomes” of seeking each type of assistance.

In contrast to other camps, participants tended to describe longer-term help seeking as a phased process. As noted in Figure 3, women were unlikely to progress through phases unless they continued to experience IPV over a long period and if the violence was severe. The first and most common option described was to disclose to friends or immediate relatives, primarily mothers. Initially, advice from friends and mothers tended to encourage the woman to stay and persevere resulting in women continuing to think through and decide on next steps, with many women not taking any other steps and continuing to persevere in the relationship. Women specifically differentiated this pathway from seeking assistance from family to “resolve” conflict and is therefore separated out in Figure 3 as two steps with some women never progressing to the second level. This may be due to reluctance to disclose to male family members (i.e., brothers, fathers) due to a fear that they would confront the husband, thereby escalating the situation and potentially leading to the husband divorcing his wife. However, if the violence continued, then the woman’s family may discuss the situation with the couple. The perpetrator would typically be given many opportunities to change his behavior. One of the outcomes of this discussion may include the woman staying with family members in the camp temporarily while discussions continued. In rare cases, the visit extended for a long period, sometimes becoming permanent and leading to divorce. Therefore, women without family support in the camp faced considerable barriers in finding a safe place to live during informal resolution processes. Unlike the other two settings, neighbors did not play a significant role in the response. Generally, women felt strongly that they did not want neighbors to know if they had problems in their marriage, believing that neighbors would lose respect for them or even take pleasure in knowing they were having problems. There was little trust between families, and women experiencing IPV felt extremely ashamed about what was happening to them.

The vast majority of IPV cases never progressed past the immediate family intervening. In comparison to other camps, the Domiz camp structure did not include block leaders or a clear community leader structure involved in responding to violence. Typically, reporting to formal organizations only took place if significant violence continued after family intervention and a woman and her family would seek help together. In the minority of cases whereby a woman and her family decided it was not possible for her to remain in the abusive relationship any longer, there were a number of formal providers they could approach. However, no clear patterns emerged from the analysis. As depicted in Figure 3, multiple organizations offered referrals, psychosocial support, medical intervention, and opportunities to discuss options and ongoing concerns, including but not limited to local gender-based violence organizations, a government department responsible for addressing violence against women, and the organization responsible for camp management. An overall theme that emerged was the variation in possible outcomes associated with seeking support from these agencies. For example, as noted in the darker gray boxes in Figures 1, 2, there were clear typical outcomes associated with seeking help from the police in Ajuong Thok and Dadaab, but in Domiz there could be several potential outcomes.

Among the various options, two clear response pathways emerged and depicted in Figure 3. First, the government department responsible for addressing violence against women, referred to locally as “Women’s Rights,” was preferred by many women, primarily because they had powers that the other organizations did not have, and women believed that a warning from this office had the potential to change their husband’s behavior. “Women’s Rights” initially mediated and decided who was “at fault,” then they advised and warned that person. They could also draw up a legally recognized agreement, which the man would sign, promising not to beat again, and if this was breached, the man would be detained, his residence card removed and court procedures initiated. Participants indicated that this approach had been effective in some cases in reducing or preventing IPV and, even when it was not, women felt that they had tried everything so were justified in divorcing the man. One woman described how her husband had signed such an agreement, stipulating that he would not physically abuse her again. She shared, “After this agreement, I stayed with him for three to four months, but he started to beat me again. I knew this man would never be scared of God, people, anything.”

A second more defined pathway in Domiz was reporting to the police. In contrast to the other two settings, participants perceived the police in Domiz as supportive and working collaboratively with other actors (see dashed referral lines in Figure 3). Very few women wanted their husband arrested, but some wanted the police to warn their husbands in the hope this might frighten him into changing his behavior. The police worked closely with “Women’s Rights” and a local organization offering psychosocial and legal support.

Finally, in rare instances, participants noted some women who continued to experience IPV after seeking support from organizations may seek to separate from their partner. Again, multiple organizations provided support around organizing a divorce and pursuing cases, however participants explained that women rarely went forward with this option. Indeed, while participants described a relatively diverse set of agencies and options, they highlighted these options were rarely explored. Conversely, women who had pursued some of these options did note positive experiences, especially in cases when there was a concrete warning given to the perpetrator.

Results from this study elucidated clear patterns in responses to IPV across three refugee camps at a particular point in time. Across settings, women began by “persevering” in the face of violence. They then engaged informal systems, which uniformly included family and, in two camps, included other (male) community members as well. Only when those informal systems did not stop the abuse, or otherwise yield intended results, did women—or other actors within the informal responses—tend to engage formal providers. All women highlighted challenges in accessing care and significant stigma around disclosing abuse. Though similarities across camps were many, differences across camp settings highlighted the importance of understanding informal systems and the actors involved, and the availability and scope of organizational responses, which influenced the sequence and speed with which formal systems engaged. In this section, we discuss nuances of IPV response pathways across the three sites paying particular attention to context, role of family and friends, community responses, and formal responses. Subsequently, we consider the implications of the findings for policy, practice, and future research.

The findings reiterate the role of context and setting in shaping response options available for women seeking help for IPV. The three refugee camps differed in terms of how long they had been in existence, structures and organizations, availability of services, social norms, and impacts of displacement on people’s lives. These differences influenced the options available to women experiencing IPV. A clear similarity across the three sites was women’s tenacity and attempts to “persevere” in abusive relationships. Indeed, women made exceptional efforts to stay in their marriages and keep the family together in spite of the abuse they experienced, which is in line with research with displaced populations in other settings (Horn, 2010b; Al-Natour et al., 2018; Strang et al., 2020). In all three camps, women reported staying silent about IPV because if their husband found they had disclosed what was happening, there was nothing to stop him from further violence. Physical protection of women experiencing IPV across the sites was minimal, and women depended on neighbors and family members to intervene.

The lack of protection indicates a profound weakness in community-based and formal responses, and points to an important area of intervention to strengthen physical protection strategies available to women experiencing IPV, without necessarily requiring women to make a formal report and risk an unintended escalation in response. Inconsistencies in informal and formal justice responses to hold abusers accountable have tremendous variance in application in displacement settings. This lends itself to a climate of impunity, in which these systems fail to act as a deterrent to using violence against a female intimate partner/spouse. The lack of consistent specialized protection services available to women under these circumstances severely limits their options, as well as the options formal GBV providers have at their disposal to offer survivors. For instance, while the combination of income generating and empowerment programs have systematically been promoted by the humanitarian infrastructure (Tappis et al., 2016), entrenched patriarchy embedded in systems and structures severely limit the viability of options and create undue burdens on women to take action in opposition to societal forces at work.

Across the three camps, women frequently turned to family members and/or women friends to obtain emotional support and advice, which is in alignment with IPV studies conducted with displaced communities in other contexts (Al-Natour et al., 2018; Strang et al., 2020) as well as in the broader IPV literature. The findings also highlight that once women decided they were no longer able to cope with the violence, they would disclose to male family members since men had more authority to address the situation and potentially bring about change. Women whose family members were not accessible faced particular difficulties in addressing their situation. In the three camps studied here, families were scattered and women often lacked the option of temporarily staying with their parents in times of need. Other studies have reported similar issues, whereby women without family perceived an absence of support options when faced with IPV and in some cases, abusive partners would take advantage of this additional vulnerability (Horn, 2010b; Wachter et al., 2019b). Yet, support from women’s parents can be contingent on women’s willingness to abide by a decision to remain in the marriage.

One of the clear distinctions between the three settings in the current study was the fluidity with which women engaged with various options once they had decided to disclose IPV outside their immediate circle of women confidantes. The availability and strength of community structures appeared to influence to whom women disclosed. Community-based mechanisms for resolving conflicts in refugee camps often attempt to replicate systems that functioned pre-displacement. However, in Domiz this was not possible at all. In the other two camps, community mechanisms were much weaker than they had been pre-displacement and lacked the necessary power to be effective. For instance, in Ajuong Thok, and to a lesser extent in Dadaab, participants indicated that block leaders and elders did not have the same authority as those in similar positions would have had in their home countries, which limited their influence on men who abused their female partners. Similarly, a study of refugee dispute mechanisms in Uganda highlighted challenges customary leaders faced to maintain their status and authority, whereby elders and chiefs felt overlooked and undermined as members of their community issued complaints directly to Ugandan authorities (Vancluysen and Ingelaere, 2020). However, women may face dire consequences when leaders align with men who use violence against their intimate partners.

In all three settings, community-based mechanisms commonly focused on consensus, discussion, and persuasion. These interventions usually had several stages and took place over time, similar to mediation practices. Process was important, perhaps more important than the outcome, particularly in terms of keeping all parties engaged. Community-based mechanisms did not offer quick solutions and they gave many opportunities for abusers to change their behavior. Yet, these processes were not necessarily inclusive of the women seeking help for IPV, as noted in the examples of the Maslahas in Hagadera camp. Furthermore, the absence of family members in the camp limited the effectiveness of community-based mechanisms, since distant relatives and neighbors did not have the same authority as the parents of the woman or the abusive partner to make decisions and influence change (Horn, 2010b). Where they functioned (Ajuong Thok and Dadaab), survivors who did not engage community mechanisms faced the possibility of rejection and hostility from family and community members, and losing support vital for survival. Rejection by family and the community puts women in a precarious position, since social networks are crucial to women’s wellbeing whether they stayed with or separated from their male partners. These findings, in combination with other studies (Strang et al., 2020), suggest that societal pressures and the threat of severing connections and losing support may be salient reasons for women to engage primarily with community-based mechanisms when seeking help for the violence they experience at home.

In all three camps, community members generally perceived reporting to formal systems (e.g., GBV providers, UN agencies, and police) as a last resort. Women would typically persist with community-based mechanisms for considerable time before approaching formal organizations, in an attempt to garner community support for doing so. Women who approached formal providers appeared resigned to the fact that divorce may be the only solution available to them; nevertheless, women retained hope that providers would help them avoid separation. Therefore, when women approached an agency for help, they often asked providers to talk to their husband and put pressure on him to change his abusive behavior, reflective of familiar community-based approaches. Research has captured similar dynamics in resettlement contexts as well (Wachter et al., 2019b). Yet, priorities and values underpinning community-based mechanisms and formal responses do not always readily align (Columbia Group for Children in Adversity, 2013).

The community-based mechanisms described in this study promoted keeping stakeholders engaged, consensus among multiple decision-makers, and values associated with family and community unity. In contrast, formal GBV services and programs in camps, drawing from survivor-centred approaches, prioritize individual women’s safety and wellbeing, and empowering women to choose the best way forward for themselves. Interagency GBV Case Management Guidelines (2017) state that GBV caseworkers should never mediate but rather, should act as advocates for the survivor and provide support to an abused woman before, during and after any mediation process. Caseworkers should also seek to gain an understanding of local mediation justice systems in a given context, and provide support to survivors engaged in mediation processes. Critics of mediation approaches in cases of IPV argue that unequal power relations undermine the process by silencing survivors and creating opportunities for perpetrators to retaliate against and re-victimize female partners by victim-blaming, threats, and acts of violence and coercion (Koss, 2000; Cameron, 2006).

These divergent perspectives and approaches complicate help seeking processes for women and create significant challenges that impede collaboration between formal responses and community structures. Formal GBV providers in refugee camps have systematically advocated through community sensitizations and discussions with key stakeholders, oftentimes over the course of years (even decades), that mediation-based approaches are not advisable in cases of IPV and other forms of GBV. Yet, these efforts have not always yielded the intended effects, frustrating advocates. The tensions inherent in dissimilar understandings, principles, and priorities underscore the need for innovative and transformative approaches to re-envision what supporting the well-being of women and girls, ensuring the safety of survivors, and holding perpetrators appropriately accountable looks like in the unique context of refugee camps.

While there is tremendous variation in women’s experiences with IPV, the analysis foregrounds the imperative for formal and informal actors committed to the safety and wellbeing of women to facilitate help seeking and ensure women get the help they need and want. Ideally, collaborative responses—family, community, and formal services–should seek to shorten the period in which women “persevere,” seek help, and ultimately access assistance that reduces and/or ends the negative, harmful impacts of IPV associated with IPV; as well as strengthen coping mechanisms, personal safety, and social connections. The findings from this study point to the need for bolstering efforts to transform IPV policy, practice, and research in refugee camp settings.

Women and girls must be at the center of every effort to improve IPV policy and practice in refugee camps. Responses must be rooted in the lived experiences of women who experience IPV and address the challenges they face in a way that minimizes the risks and costs involved for seeking help and reprieve from abuse. It is therefore important to invest in context-specific studies to produce a nuanced understanding of the challenges and stakes involved from the perspectives of women. While centering women’s perspectives in knowledge-building efforts, participatory approaches can also contribute to building more authentic collaborations and relationships across family, community, and formal systems in camps. In deepening understandings of challenges and opportunities, additional areas of inquiry are central to examine further. First, understanding the role children play in shaping women’s help seeking for IPV (Rhodes et al., 2010; Randell et al., 2012) in contexts of refugee camps is important for informing practice and policy necessary for addressing their concerns. Second, as evidenced in the broader IPV literature, economic pressures on women are salient factors shaping help seeking for IPV (Postmus et al., 2012); indeed, coping with IPV is interrelated with women’s economic needs (Hahn and Postmus, 2014). In contexts of displacement, employment opportunities are scarce and women face additional obstacles in generating income due to social expectations and norms related to gender (Falb et al., 2014; Wachter et al., 2017) and intersecting social positions. Therefore, ensuring access to high quality services responsive to broad needs expressed by women and girls, inclusive of IPV and other forms of GBV, is an ongoing imperative in refugee camps.

Efforts to address IPV must consider women’s priorities in a holistic sense in recognition that women oftentimes consider IPV one problem among many. Support services for IPV survivors in camp settings must account for the social connections women seek to maintain. Women who experience abuse from their male partner find themselves in a fraught position and subject to various and competing pressures to engage or disengage family, community, and formal systems. Under already very difficult circumstances and extreme risk, displaced women can face severe consequences for speaking out, and they face different but possibly equally serious consequences for not seeking help. While some families and communities create hardships and even inflict harm on women experiencing IPV (Wachter et al., 2019a), these systems hold tremendous potential for providing the emotional and practical support women need and want, while keeping women connected to vital social and economic lifelines. Programmatic approaches that thoughtfully integrate family, community, and formal systems involved in addressing IPV would be an important step forward. Critical to these efforts are local women-led organizations in promoting the rights, safety, and well-being of women and girls, while strengthening social networks to support and keep women vitally connected to family and community members.

Additionally, it is important that formal services do not undermine natural recovery processes (World Health Organization War Trauma Foundation and World Vision International, 2011). Evidence indicates that the majority of people who experience distressing events, such as IPV, will recover over time if their basic needs are met, they are safe, and they have the support of family and community (Inter-Agency Standing Committee, 2007). Support from external agencies may be required to ensure that survivors have sufficient resources and support to fulfill their own basic needs and those of family members under their care (e.g., children and elderly). It is important to offer informal psychological services for IPV survivors who require them (e.g., supportive listening and support groups), which could be embedded in the community, as well as specialized mental health care provided by formal providers for those who need a higher level of care.

Efforts to address IPV in refugee camps must strengthen community responses without colluding with systems, structures, or activities that condone or sustain violence against women and girls. One of the key findings of the current study was that physical protection of women experiencing IPV was minimal, as was accountability of men who use violence. In all three camps women said they had stayed silent about the abuse because if their husbands found they had disclosed what was happening, there was nothing to stop them from harming the women more severely as a result. Advocacy for functional systems of accountability for violence, and the physical protection of those experiencing violence, is a crucial element necessary for IPV prevention and response. When violence occurs, family and neighbors who live alongside women experiencing IPV can react immediately by intervening directly or alerting security services, if they have sufficient information and buy-in to do so safely and effectively. In addition, community members can offer temporary shelter and protection and practical support to survivors, without removing women from supportive elements of her community. Service providers can also support community actors to establish a system of safe housing among community members and women-led activists, as a replacement for the temporary respite some women experiencing IPV would have previously sought with their parents.

Situating responses to IPV as part of broader transformative prevention efforts is instrumental to meaningful and transformative work. Solidarity groups that evolve in support of ending violence against women and girls through thoughtful community-based programming and activism would serve the evolution of community processes to promote the well-being of women and girls (Michau et al., 2015) (For program examples see SASA!1; Engaging Men through Accountable Practice2; and Indashyikirwa3). Amplification of women and girls’ voices in grassroots advocacy efforts with influential community stakeholders is vital to encourage help seeking and improve responses to IPV at all levels.

As actors and stakeholders engage their communities in transformative change, participatory methods can contribute to monitoring progress. Our approach to generating visual maps of IPV response pathways facilitated participation of multiple stakeholder groups and produced visual models that can serve as a launching point for discussion and idea generation. Expanding this approach by creating “living” visual maps to which new responses and resources are added over time, can contribute to tracking progress and continually informing the design of IPV responses in specific contexts.

Finally, shifting power and resources to local women-led organizations is fundamental to addressing violence against women and girls in displacement settings. Recent calls for reforms indicate that the international community can do more to put communities at the center of the response to humanitarian crizes. At the core of localization advocacy underway is a call for a shift in power, so that local actors take a leading role in humanitarian responses, with international actors stepping in only if and when necessary (Sadiq, 2020). This goes beyond traditional partnerships between humanitarian agencies and local actors, by which international organizations recruit and train local actors such as community and faith leaders to disseminate messages or implement activities developed by humanitarian actors (Svoboda, 2018). Yet, despite the sustained work of women-led organizations and global commitments to localize GBV prevention and response, there has been minimal engagement of women rights actors in the humanitarian sector, dominated by INGOs and global north actors (Care and GBV Area of Responsibility, 2019). Indeed, less than one percent of funding investments to support gender equality have reached feminist organizations in the global south (The Guardian, 2019). The expertize, commitments, and activism of local and regional women’s organizations in the global south are instrumental to creating and sustaining social networks critical to women’s healing, amid broader social, economic, and political aims. Ensuring a localized approach, embedded in broader efforts to decolonize international humanitarian assistance writ large (Kemitare and Eoomkham, 2019; Currion, 2020), is an important step forward in shifting power and bringing actors traditionally kept at the margins to the center of local efforts to assist displaced people.

It is important that readers situate the findings at the point in time when the data collection took place, with the understanding that contexts are dynamic, work is ongoing, and circumstances continuously shift. Another consideration is that findings draw from a non-representative sample of survivors and community members, and therefore are not generalizable. Additionally, the results only reflect IPV pathways in these three refugee camp settings; we do not intend to infer transferability of these conclusions to other or all refugee camps and displacement settings. Rather, a main conclusion from this research is that future work in research and practice would benefit from replicating and building on these processes in other settings. This would contribute to the body of knowledge related to IPV in displacement settings and contribute to enhancing practice and policy solutions.

This study reiterated the complexities involved in bridging formal and community-based systems responding to IPV in refugee camps. Results of this study show the benefits of understanding response pathways in specific contexts by describing them from multiple perspectives and then visually summarizing them in maps for analysis. After fully understanding the IPV pathways women navigate, the next step is to identify avenues for change and develop strategies to enhance policy and practice. The findings from this study indicate that strategies will require listening to women and understanding their priorities; recognizing the importance for women in camps to maintain life-sustaining connections with their families and communities; engaging communities in transformative change; and shifting power and resources to local women-led organizations.

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because we do not have permission to share highly sensitive qualitative data in raw format. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to cmViZWNjYS5yLmhvcm5AZ21haWwuY29t.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Duke University Ethical Review Board. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

RH led on the data collection and analysis, and the drafting of the manuscript. KW, EF-H and EP contributed to the data analysis and interpretation, and the drafting of the manuscript. SWN and JC contributed to the contextualisation of the findings and the drafting of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

The research was funded by the U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration (S-PRMCO-13-CA-1209).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abramsky, T., Francisco, L., Kiss, L., Michau, L., Musuya, T., Kaye, D., et al. (2010). SASA! Baseline report. London, United Kingdom: London School of Hygiene and Tropical medicine (LSHTM) and raising voices.

Al-Natour, A., Al-Ostaz, S. M., and Morris, E. J. (2018). Marital violence during war conflict: the lived experience of Syrian refugee women. J. Transcult. Nurs., 30, 32–38. doi:10.1177/1043659618783842

Andersson, N., Ho-Foster, A., Mitchell, S., Scheepers, E., and Goldstein, S. (2007). Risk factors for domestic physical violence: national cross-sectional household surveys in eight southern African countries. BMC Wom. Health 7, 11. doi:10.1186/1472-6874-7-11

Barrett, B. J., and St Pierre, M. (2011). Variations in women’s help seeking in response to intimate partner violence: findings from a Canadian population-based study. Violence Against Women 17, 47–70. doi:10.1177/1077801210394273

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3 (2), 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Cameron, A. (2006). Stopping the violence. Theor. Criminol. 10 (1), 49–66. doi:10.1177/1362480606059982

Care and the GBV Area of Responsibility (2019). Gender-Based Violence (GBV) Localization: humanitarian transformation or maintaining the status quo? Available at: https://careevaluations.org/wp-content/uploads/GBV-Localization-Mapping-Study-Full-Report-FINAL.pdf (Accessed January 25, 2021).

Coker, A. L., Watkins, K. W., Smith, P. H., and Brandt, H. M. (2003). Social support reduces the impact of partner violence on health: application of structural equation models. Prev. Med. 37, 259–267. doi:10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00122-1

Columbia Group for Children in Adversity (2013). A rapid ethnographic study of community-based child protection mechanisms in somaliland and puntland and their linkage with national child protection systems. New York, NY: Columbia Group for Children in Adversity.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. New York, NY: Sage publications.

Currion, P. (2020). Decolonising aid, again. Available at: https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/opinion/2020/07/13/decolonisation-aid-humanitarian-development-racism-black-lives-matter (Accessed September 30, 2020).

da Costa, R. (2006). The administration of justice in refugee camps: a study of practice. Geneva, Switzerland: UNHCR.

Ellsberg, M., and Heise, L. (2005). Researching violence against women: a practical guide for researchers and activists. Washington DC, PATH: World Health Organization.

Ergöçmen, B. A., Yüksel-Kaptanoğlu, İ., and Jansen, H. A. F. M. H. (2013). Intimate partner violence and the relation between help-seeking behavior and the severity and frequency of physical violence among women in Turkey. Violence Against Women 19, 1151–1174. doi:10.1177/1077801213498474

Falb, K. L., Annan, J., King, E., Hopkins, J., Kpebo, D., and Gupta, J. (2014). Gender norms, poverty and armed conflict in Côte D’Ivoire: engaging men in women’s social and economic empowerment programming. Health Educ. Res. 29, 1015–1027. doi:10.1093/her/cyu058

Freedman, J. (2016). Sexual and gender-based violence against refugee women: a hidden aspect of the refugee “crisis”. Reprod. Health Matters 24 (47), 18–26. doi:10.1016/j.rhm.2016.05.003

Fugate, M., Landis, L., Riordan, K., Naureckas, S., and Engel, B. (2005). Barriers to domestic violence help seeking: implications for intervention. Violence Against Women 11, 290–310. doi:10.1177/1077801204271959

Garcia-Moreno, C., Jansen, H. A. F. M., Ellsberg, M., Heise, L., and Watts, C. (2005). WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women: initial results on prevalence, health outcomes and women’s responses. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health OrganizationAvailable at: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2019/jul/02/gender-equality-support-1bn-boost-how-to-spend-it (Accessed June 17, 2020). The Guardian (2 July 2019). Only 1% of gender equality funding is going to women’s organisations – why?

Hahn, S. A., and Postmus, J. L. (2014). Economic empowerment of impoverished IPV survivors: a review of best practice literature and implications for policy. Trauma Violence Abuse 15, 79–93. doi:10.1177/1524838013511541

Horn, R. (2010a). Exploring the impact of displacement and encampment on domestic violence in Kakuma refugee camp. J. Refug. Stud. 23, 356–376. doi:10.1093/jrs/feq020

Horn, R. (2010b). Responses to intimate partner violence in kakuma refugee camp: refugee interactions with agency systems. Soc. Sci. Med. 70, 160–168. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.036

Hossain, M., Izugbara, C., McAlpine, A., Muthuri, S., Bacchus, L., Muuo, S., et al. (2018). Violence, uncertainty, and resilience among refugee women and community workers: an evaluation of gender-based violence case management services in the Dadaab refugee camps. London, United Kingdom: Department for International Development.

Inter-Agency Standing Committee (2007). IASC guidelines on mental health and psychosocial support in emergency settings. Geneva, Switzerland: IASC.

Interagency GBV Case Management Guidelines (2017). Providing care and case management services to gender-based violence survivors in humanitarian settings. Available at: https://gbvresponders.org/response/gbv-case-management/ (Accessed August 21, 2020).

Kennedy, A. C., and Prock, K. A. (2018). “I still feel like i am not normal”: a review of the role of stigma and stigmatization among female survivors of child sexual abuse, sexual assault, and intimate partner violence. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse. 19 (5), 512–527. doi:10.1177/1524838016673601

Kemitare, J. W., and Eoomkham, J. (2019). Feminist practice: local women’s rights organisations set out new ways of working in humanitarian settings. Available at: https://odihpn.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Humanitarian-Exchange-Issue-75-web-version.pdf (Accessed August 21, 2020).

Koss, M. P. (2000). Blame, shame, and community: justice responses to violence against women. Am. Psychol. 55 (11), 1332–1343. doi:10.1037//0003-066x.55.11.1332

Megevand, M., and Marchesini, L. (2020). Women and girls safe spaces: a toolkit for advancing women’s and girls’ empowerment in humanitarian settings international rescue committee and international medical corps. Available at: https://gbvresponders.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/IRC-WGSS-English-2020.pdf (Accessed 25 Jan 2021)

Michau, L., Horn, J., Bank, A., Dutt, M., and Zimmerman, C. (2015). Prevention of violence against women and girls: lessons from practice. Lancet 385, 1672–1684. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61797-9

Naved, R. T., Azim, S., Bhuiya, A., and Persson, L. A. (2006). Physical violence by husbands: magnitude, disclosure and help-seeking behavior of women in Bangladesh. Soc. Sci. Med. 62, 2917–2929. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.12.001

Postmus, J. L., Plummer, S. B., McMahon, S., Murshid, N. S., and Kim, M. S. (2012). Understanding economic abuse in the lives of survivors. J. Interpers. Violence 27 (3), 411–430. doi:10.1177/0886260511421669

Randell, K. A., Bledsoe, L. K., Shroff, P. L., and Pierce, M. C. (2012). Mothers’ motivations for intimate partner violence help-seeking. J. Fam. Violence. 27 (1), 55–62. doi:10.1007/s10896-011-9401-5

Rhodes, K. V., Cerulli, C., Dichter, M. E., Kothari, C. L., and Barg, F. K. (2010). “I didn’t want to put them through that”: the influence of children on victim decision-making in intimate partner violence cases. J. Fam. Violence 25 (5), 485–493. doi:10.1007/s10896-010-9310-z

Rodgers, B. L., and Cowles, K. V. (1993). The qualitative research audit trail: a complex collection of documentation. Res. Nurs. Health. 16 (3), 219–226. doi:10.1002/nur.4770160309

Sadiq, M. (2020). INGOs and the localisation agenda humanitarian academy for development blog. Available at: https://had-int.org/blog/ingos-and-the-localisation-agenda/ (Accessed September 30, 2020).

Strang, A., O'Brien, O., Sandilands, M., and Horn, R. (2020). Help-seeking, trust and intimate partner violence: social connections amongst displaced and non-displaced Yezidi women and men in the Kurdistan region of northern Iraq. Conflict Health 14, 61. doi:10.1186/s13031-020-00305-w

Svoboda, E. (2018). Humanitarian access and the role of local organisations. Available at: https://refugeehosts.org/2018/01/15/humanitarian-access-and-the-role-of-local-organisations/ (Accessed September 30, 2020). Refugee Hosts Blog doi:10.2307/j.ctv6sj8fh

Sylaska, K. M., and Edwards, K. M. (2014). Disclosure of intimate partner violence to informal social support network members: a review of the literature. Trauma Violence Abuse 15, 3–21. doi:10.1177/1524838013496335

Tappis, H., Freeman, J., Glass, N., and Doocy, S. (2016). Effectiveness of interventions, programs and strategies for gender-based violence prevention in refugee populations: an integrative review. PLoS Curr. 8, ecurrents. doi:10.1371/currents.dis.3a465b66f9327676d61eb8120eaa5499

The Guardian (2019). Only 1% of gender equality funding is going to women's organisations ‐ why?. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2019/jul/02/gender-equality-support-1bn-boost-how-to-spend-it (Accessed June 17, 2020).

UN Women (2018). Unpacking gendered realities in displacement: the status of Syrian refugee women in Jordan, Lebanon and Iraq. UN women Arab states. Available at: https://arabstates.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2018/12/unpacking-gendered-realities-in-displacement (Accessed August 26, 2020).

UNHCR (2019). UNHCR global report 2018 geneva: UNHCR. Available at: https://reporting.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/gr2018/pdf/GR2018_English_Full_lowres.pdf (Accessed August 26, 2020).