94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Hum. Dyn., 09 June 2021

Sec. Digital Impacts

Volume 3 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fhumd.2021.600146

This article is part of the Research TopicDigital Media and Social Connection in the Lives of Children, Adolescents and FamiliesView all 15 articles

With increasing media choice, particularly through the rise of streaming services, it has become more important for empirical research to examine how youth decide which programs to view, particularly when the content focuses on difficult health topics such as suicide. The present study investigated why adolescents and young adults chose to view or not view season 1 of 13 Reasons Why and how individual-level variables related to adolescents’ and young adults’ viewing. Using survey data gathered from a sample of 1,100 adolescents and young adult viewers and non-viewers of the series in the United States, we examined how participants’ resilience, loneliness, and social anxiety related to whether participants viewed the first season or not. Our descriptive results indicate that adolescents who watched the show reported that it accurately depicted the social realities of their age group, they watched it because friends recommended it, and they found the subject matter to be interesting. Non-viewers reported that they chose not to view the show because the nature of the content was upsetting to them. In addition, results demonstrated that participants’ social anxiety and resilience related to participants’ viewing decisions, such that those with higher social anxiety and higher resilience were more likely to report watching season 1. Together, these data suggest that youth make intentional decisions about mental health-related media use in an attempt to choose content that is a good fit for based on individual characteristics.

Entertainment media producers have increasingly integrated mental health-related topics into their narratives, including depictions of depression, suicide, bullying, and sexual assault (Pirkis and Blood, 2001; Rubin, 2014). One recent series in this domain is 13 Reasons Why (13RW), which debuted in the United States on Netflix on March 31, 2017. The streaming-only adolescent-directed original series has been controversial for its plotline, which involves a detailed and graphic account of the series of events that lead to a fictional adolescent character (Hannah Baker) dying by suicide. Though the series has been popular among adolescent audiences globally, the show provoked a debate over its portrayal of sensitive subjects such as suicide, self-harm, rape, and bullying, with some arguing that it may have violated guidelines on media portrayals of suicide (Arendt et al., 2017; Chesin et al., 2019). Many educators and health professionals were critical of the depiction of suicide (Brooks, 2017), warning that it could contribute to a contagion effect, and linked the show to self-harm and suicide threats among young people.

Research on the first season of 13RW has depicted varied relations between viewing and adolescent and young adult behavior. Some studies have reported concerning findings related to viewing 13RW (e.g., Ayers, et al., 2016; Niederkrotenthaler, et al., 2019; Santana da Rosa et al., 2019; Bridge et al., 2020) while others have found no concerns related to viewing (e.g., Ferguson, 2019; Romer, 2020). Further, multiple other studies using large, non at-risk samples have found potentially prosocial correlates of viewing (e.g., Arendt et al., 2019; Carter et al., 2020). Together, these findings suggest there is disagreement between studies about whether effects exist and, if they do, whether they are more positive or negative (see also Mueller, 2019). One possible reason for these differing findings regards the nature of the audience; indeed, it is likely that some adolescents chose not to view the series because of the widely reported graphic nature of the content, while others viewed the series in an attempt to learn more about the subject matter or because they found the subject matter to be interesting or entertaining. Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to examine individual-level characteristics that relate to participants’ viewing (or not) of the first season of the series. To our knowledge, research has not yet considered the characteristics of the audience of 13RW, and a study of this kind will provide more information regarding who watched season 1 of the series, and could help to explain some of the differences detected as to the correlates of viewing. Further, given the rise of mental health-related, adolescent-directed programming (Carter et al., 2020), this study can provide information about the characteristics of individuals who choose to consume, or not consume, such programming. Our study uses the selective exposure framework to examine the factors that may have associated with viewers opting to watch the show or opting out of viewing. Specifically, we use data from a survey of adolescent (13–17) and young adult (18–22) viewers and non-viewers living in the United States (N = 1,100). We examine participants’ responses to why they chose to watch or not to watch season 1, and test how key risk factors including loneliness, social anxiety, and resilience associate with participants’ viewing.

Researchers have continually examined selection patterns of consumers in various contexts (Stroud, 2007). The selective exposure framework posits that audience members prefer content that is reflective of their perspectives, experiences, beliefs, attitudes, and decisions (Zillmann and Bryant, 1985; Sherry, 2001; Sherry, 2004; Sherry et al., 2006). According to this framework, these preferences may also leave viewers more susceptible to model portrayed behaviors. Self-concept, or an individual’s representations and evaluations of themselves, is important in this context as it influences how people understand their own abilities, cognitive capacities, and the choices that they make to pursue certain activities. In other words, “self-concept does not merely reflect ongoing behavior, it actually guides behavior” (Brummelman and Thomaes, 2017, p. 1764). Thus, in the present context, we might expect that adolescents and young adults were drawn to view the first season of 13RW because the series portrayed adolescent and young adult life and therefore was consistent with individuals’ experiences. Further, given the popularity and press attention received, individuals may have chosen to view 13RW because their friends discussed it or watched it themselves. In doing so, however, individuals are still making viewing decisions that align with their experiences in their social context. Additionally, however, certain adolescents and young adults may have opted against viewing because they felt that the nature of the content, and the portrayal of mental health and suicide, was not appropriate for themselves personally, even if it was consistent with their experience. Based on the nature of their social group, individuals also may have heard negative feedback about the series and its appropriateness, which would also influence decisions to not view 13RW.

Indeed, according to common notions of selective exposure (e.g., Zillmann and Bryant, 1985), when deciding what content to watch among a number of options, people will expose themselves to materials aligned to their personal predispositions, avoiding those they deem unrelated to them or inappropriate for them. Thus, individuals at risk for mental health concerns may choose not to view programming that portrays characters experiencing mental health crises even though the content “fits” with that individuals’ lived experience. This may be particularly the case for 13RW, as the controversial portrayal of a character’s death by suicide was covered extensively in the popular press around the world (e.g., Saint Louis, 2017), and adolescents themselves were conflicted about viewing the series (Common Sense Media, n.d.). Therefore, prior to viewing, it is likely that many individuals were well aware of the nature of the content, and could chose to view or not view based on their personal predispositions, as well as feedback they had heard about the series from their friends, parents, or the popular press.

As noted, previous research on the correlates of viewing 13RW has been mixed. These mixed findings are likely due to the nature of the samples, indicating that individual differences among viewers is key to understanding the correlates of viewing, not just of 13RW, but other related series that focus on mental health issues among adolescents. For example, multiple studies have found maladaptive correlates of viewing 13RW among small, at-risk samples, particularly those with an expressed mental health need (e.g., Hong et al., 2018; Plager Zarin-Pass and Pitt, 2019). Chesin and colleagues (2019), however, found that suicide knowledge, or the knowledge of risk factors for suicide such as isolation, loneliness, and disconnection, was positively related to watching 13RW among those with no personal exposure to suicide, but there was no relationship between exposure and participants’ suicide ideation severity or suicidal behaviors. Among a largely non-at-risk sample, Lauricella and colleagues (2018) reported that adolescents and young adults found the portrayal of mental health in 13RW to be realistic and felt that it gave them better awareness of suicide risk and how to have serious conversations with supportive adults about mental health.

Using ecological data, Bridge and colleagues (2020) conducted a time series analysis of suicide rates in the United States following the initial release of 13RW. Their analysis found that suicide rates increased beyond expectations among males aged 10–17 in the month after the season 1 of 13RW was released. Niederkrotenthaler and colleagues (2019) also found an increase in deaths by suicide in the three months following the release of season 1, but this increase was among female viewers. After reanalyzing the data using an auto-regression model that tested for changes in rates after removing auto-correlation and national trends in suicide, however, Romer (2020) found that the increase for boys observed by Bridge et al. (2020) was no greater than the increase observed during the prior month before the show was released, or the later months of that year. Though Romer (2020) found a slight change in suicide for girls the month after the show was released, he concluded that it was still difficult to attribute harmful effects of the show using aggregate rates of monthly suicide rates. Adding to the uncertainty of this debate, most recently, Ferguson (2021) found that watching 13RW was associated with reduced depressive symptomatology and was not associated with suicidal ideation among viewers. Finally, in meta-analytic work, Ferguson (2019) concluded that the current state of the literature did not support the idea that fictional media can create a suicide contagion effect.

Together, these studies demonstrate that individual-level, mental health risk factors influence the nature of the correlates of viewing. For example, those at risk for mental health crises report negative outcomes, including negative affect (Hong et al., 2018) and worsening mental health symptoms (Plager Zarin-Pass and Pitt, 2019), while those less at risk report adaptive changes in prosocial mental health behaviors, such as reaching out to support friends in need (Carter et al., 2020). Thus, understanding the individual differences that predict whether an individual watched the first season is key to understanding the correlates of viewing. This may be the case because at-risk individuals chose to not view the series because they knew about the nature of the content, and that the portrayal of a characters’ death by suicide may be distressing to them personally. Conversely, non-at-risk individuals may have opted to view the series because it was popular, because they wanted to learn more about the subject matter, and because they felt that they could safely handle the portrayals of mental health in the series.

Given this context, we explore whether the correlates of 13RW on adolescent and young adults viewers is most likely attributable to individual risk factors for mental health concerns and suicide ideation. Given that risk factors appear to moderate viewer responses to 13RW, we hypothesize it is likely that these risk factors relate to choosing to view the series in the first place (see Valkenburg and Peter, 2013). Thus, we consider how specific risk factors relate to participants choices to view the series. We focus on these in particular, as all are linked to suicidal ideation and other mental health concerns. This is important in the present context, as Hannah’s death by suicide was seen as one of the most controversial portrayals in season 1 of 13RW (e.g., Saint Louis, 2017).

We chose to focus on participant resilience, loneliness, and social anxiety because they have been identified in several studies as important risk factors related to suicidal ideation (Harris and Molock, 2000; Hefner and Eisenberg, 2009; Davaasambuu et al., 2017), although we note that many other variables relate to individuals’ suicidal risk. Resilience refers to an individual’s abilities to overcome adversity and is considered to be a protective factor against risk outcomes (e.g., Luther et al., 2000). Conversely, loneliness, or an individuals’ perceived discrepancy between desired and actual social relationships (Peplau and Perlman, 1982), and social anxiety, or an individual’s anxiety stemming from a fear of interpersonal evaluation in real and imagined settings (Leary and Kowalski, 1997), are seen as risk factors for various mental health concerns. Both loneliness and social anxiety are quite prevalent in society, although age and country of residence influence the extent of prevalence (Russell and Shaw, 2009; Yang and Victor, 2011). Indeed, social anxiety is the third most common mental health concern after depression and alcohol abuse (Russell and Shaw, 2009).

Resilience has been found to attenuate the impact of many risks including suicide (Johnson et al., 2011), while loneliness and social anxiety are risk factors for suicidal ideation (Stravynski and Boyer, 2001). Previous research has suggested that loneliness and social anxiety occur when interpersonal relationships are deficient and fail to meet personal expectations (Peplau and Perlman, 1982). As different life stages come with different developmental goals, the importance of social engagement differs over the life course (Heckhausen et al., 2010). In the case of adolescents and young adults, loneliness and social anxiety may derive, respectively, from various factors, including not feeling well connected to one’s peers and fear of judgement from others, a failure to build social networks, the daunting task of launching a career, and trying to find a romantic partner (Luhmann and Hawkley, 2016). Lacking belongingness and feeling disconnected from peers and family are also among the major factors leading to suicide (Joiner, 2005).

Further, we chose to examine loneliness and social anxiety because previous research has found associations between these factors and suicidal ideation in early adolescence (Roberts et al., 1998), adolescence (Garnefski et al., 1992; Heinrich and Gullone, 2006) and young adulthood (Rich and Bonner, 1987). Strong associations among suicide ideation, parasuicide, and different ways of being lonely and alone, defined either subjectively (i.e., the feeling), or objectively (i.e., living alone or being without friends), have been observed by empirical research (see Stravynski and Boyer, 2001). Moreover, the prevalence of suicide ideation has been found to increase with an individual’s degree of loneliness and social anxiety, while having social support is seen by many as correlated to endorsements of high life satisfaction and having positive expectations for the future (Yeh and Inose, 2003).

We chose to examine resilience because it affects the ability of the individual to deal with difficult situations and actively move past them for a better future (Hamill, 2003). Resilience has been defined as a “positive adaptation within the context of significant adversity” (Luther et al., 2000; Masten 2001), indicating a “process of negotiating, managing, and adapting to significant sources of stress or trauma” (Windle et al., 2011, p. 2). Critical to the idea of resilience is that certain ecological factors and processes coupled with individual strengths may mitigate the potentially negative outcomes associated with adversities and risks (Jain et al., 2012). As a psychological construct, resilience works as a perceived ability that allows the individual to overcome adversity (Rutter et al., 2008; Johnson et al., 2010). Moreover, resilience has been conceptualized as “an ability, perception or set of beliefs which buffer individuals from the development of suicidality in the face of risk factors or stressors” (Johnson et al., 2011, pg. 564). As such, young people whose resilience is strong appear to be somewhat protected against depression and suicidal behaviors (McNamara, 2013).

Together, the selective exposure framework and existing literature suggest that adolescents and young adults make conscious decisions about the nature of the media content that they consume as a function of individual-level factors, including both individual mental health-related factors and social factors. Even when media content is similar to the lived experiences or attitudes of an individual, however, that individual may choose not to watch content that they find to be personally inappropriate or because others have warned that it is inappropriate. In the context of selective exposure, mental health, and viewing 13RW, we expect that those higher in resilience, and lower in loneliness and social anxiety, will be more likely to report viewing season 1 of 13RW and will report viewing the entire first season, rather than a portion of the episodes. We expect this because these individuals are theoretically most likely to be able to process the content in a healthy, adaptive way. Therefore, we predict:

H1: Participants’ level of 1) loneliness and 2) social anxiety will relate negatively to viewing season 1 of 13RW, while participants’ level of 3) resilience will relate positively to viewing season 1 of 13RW.

H2: Participants’ level of 1) loneliness and 2) social anxiety will relate negatively to viewing the entire first season, while participants’ level of 3) resilience will relate positively to viewing the entire first season.

Finally, we offered both viewers and non-viewers a number of close-ended options to explain their reasoning behind choosing to view season 1 or not. Thus, we ask:

RQ1: What were the reported reasons that adolescents and young adult viewers decided to watch or not watch season one of 13RW?

The data in this study are part of a larger multinational survey that includes parents, young adults, and adolescents from five countries. The full sample was purposive in nature with the goal of achieving approximately 50% viewers and non-viewers of the series with approximately equal number of respondents at each age. This paper focuses on a subsample of that data (N = 1,100), including only adolescent (n = 600; ages 13–17) and young adult (n = 500, ages 18–22) participants from the United States. The majority (70%) of the participants for this study were female (n = 767). This subsample consists of 43% viewers (n = 219 adolescent viewers, n = 252 young adult viewers) and 57% non-viewers (n = 381 adolescent non-viewers, n = 248 young adult non-viewers).

We developed an online survey and data collection was completed between November 2017 and January 2018. While this research study was funded by Netflix, the authors worked with the participant recruitment company, analyzed, and wrote descriptive reports independently. Data collection was completed by IPSOS Research, after receiving approval by the university’s institutional review board. IPSOS Research worked with partners in each country to recruit participants. To target the adolescent sample, parents who reported that they had at least one child in the home between the ages of 13–17 received an email with introductory information about the nature of the research study and a link to the online survey. Parents first consented to their own participation, and completed an online parent survey (reported elsewhere). Once we obtained parent consent, adolescents had the opportunity to provide their assent, and then answer the survey questions. Young adult participants were recruited through local agencies by IPSOS and consented to their participation. The adolescent and young adult survey took approximately 20–30 min to complete. At the end, we thanked participants for their time, and they received compensation where appropriate. The survey for adolescents and young adults was identical; the only difference was in the recruitment and consent process.

Viewers and Non-Viewers. All respondents were asked if they had watched season 1 of 13RW. This question divided the sample into “viewers” (n = 471) or “non-viewers” (n = 629).

Complete Season Viewed. Each participant who indicated that they watched the show was asked how many episodes they watched. The data was skewed toward those who reported watching all of the episodes (n = 296, 63%). Another 30 participants (6%) watched 9–12 episodes, 46 participants (10%) watched five to eight episodes, 63 participants (13%) watched two to four episodes, 30 participants (6%) watched only 1 episode, and six participants (1%) watched part of one episode. Given that 63% of viewers reporting that they had watched all of the episodes, we created a dichotomous variable for viewers who viewed all (1) or less than all (0) of the episodes of season 1.

Viewing Decisions and Reasons. We examined viewing decisions with a series of separate questions for non-viewers and viewers. Non-viewers were asked why they decided not to watch the show and could select all the reasons that applied from a 17-item list. Examples of items were “I wasn’t interested in the story or subject matter,” “I didn’t feel the topics covered were relevant to my life,” and “I heard that the content was graphic.” Similarly, viewers were asked why they chose to watch the show and could select all the reasons that applied from an 18-item list. Examples of items for viewers were “The show was relevant to my life,” and “it covered important subject matter that people my age should know more about.” For a complete listing of response options, please see Lauricella et al. (2018).

Social Anxiety. We measured social anxiety using a 10-item measure from La Greca et al. (1988; Social Anxiety Scale for Children). Participants answered each item using a 5-point Likert scale anchored by (1) strongly disagree and (5) strongly agree. Example questions include “I worry about doing something new in front of other kids,” “I am afraid that other kids will not like me,” “I am quiet when I’m with a group of kids.” A principal components analysis indicated that all items factored together. Thus, we summed and averaged the items to create an average social anxiety score, with higher scores indicating higher levels of social anxiety (M = 3.05, SD = 1.03). This measure was reliable (α = 0.94).

Resilience. Resilience was measured using an 18-item measure from the Institute of Education Science’s measure of resilience (Internal Resilience Assets; Hanson and Kim, 2007). As above, response options for each item were presented on a 5-point Likert-type scale anchored by (1) strongly disagree and (5) strongly agree. Example items that were presented to respondents were “When I need help, I can find someone to talk to” and “I understand my moods and feelings.” A principal components analysis indicated that all items factored together. Thus, we summed and averaged the items to create an average resilience score, with higher scores indicating higher levels of resilience (M = 3.90, SD = 0.68). This measure was reliable (α = 0.94).

Loneliness. Loneliness was measured using an 8-item measure from Roberts et al. (1993; Brief Measure of Loneliness for Adolescents) measure of loneliness. Response options for each item were presented on a 5-point Likert-type scale anchored by (1) strongly disagree and (5) strongly agree. Examples of items that were presented to respondents related to loneliness were “I lack companionship” and “I often feel isolated.” A principal components analysis indicated that all items factored together. Thus, we summed and averaged the items to create an average loneliness score, with higher scores indicating higher levels of loneliness, (M = 2.57, SD = 0.82). This measure was reliable (α = 0.84).

Age. Respondents ranged in age from 13 to 22 (M = 17.32, SD = 2.91).

Gender. Respondents indicated their gender as either male (30.27%; n = 333) or female (69.72%; n = 767).

Among viewers, 79% of those who heard of the show reported hearing about it from friends. Viewers generally heard the show was popular (60%), intense (59%), and sad (53%). In order to answer RQ1, which asked about participants’ reasons to view the first season of 13RW or not, we examined our dataset to understand why viewers and non-viewers of 13RW chose to watch the show (or not). The most common reasons viewers reported that they choose to watch was because they found the story interesting (69%), saw it on Netflix and decided to give it a try (57%), had either a friend (46%) or Netflix (40%) recommending it, and were curious about it because they read about the controversies surrounding the series (35%). However, only 20% of viewers reported they wanted to learn more about the topic and just 18% said they watched it because the show was relevant to their own life.

With respect to non-viewers, one-third reported that they did not watch because they felt that the content was upsetting to watch (33%) or they were not interested in the subject matter (27%). Other reasons they reported were that their friends talked about the show but that they decided it did not sound like something that they would like (25%), that it was inappropriate (18%), and some felt the content was too graphic (17%) or they did not find it relevant to their lives (9.6%). For some non-viewers, parents (8%) told them not to watch the program. Lack of access (13%) to Netflix (the subscription streaming service needed to watch the show) and not having time/opportunity to watch (22%) also resulted in non-viewership.

Thus, in answer to RQ1, the majority of viewers chose to view because they found the story interesting and because they saw it on Netflix; interestingly, however, only a small minority of viewers reported that they viewed season 1 because the show was relevant to their lives or because they wanted to learn more about the topics. Among non-viewers, a sizable minority chose not to watch because they thought the content would be upsetting, inappropriate, and/or too graphic, or because they were not interested in the subject matter. Thus, while there may be a number of reasons why an individual might find the content to be upsetting or graphic, this does indicate that approximately one-third to one-fourth of non-viewers did not watch because they were aware of the nature of the content and felt that it was not appropriate for them personally, or because their friends warned them not to consume the content.

Prior to analysis, we tested the correlations between the three main variables, social anxiety, resilience, and loneliness. While there was some relation between the variables, none of the variables reached a correlational value of 0.70, which would be indicative of multicollinearity. Moreover, Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) ranged from 1.19 to 1.63 indicating low multicollinearity (see Table 1).

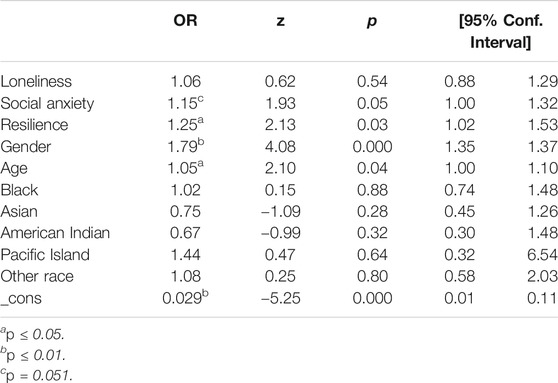

To address H1, which predicted relationships between individual-level risk factors and viewing the first season of 13RW, we ran a logistic regression with viewership (yes/no) as the dependent variable, and loneliness, resilience, social anxiety, age, gender, and race/ethnicity as independent variables. The full model was significant, pseudo R2 = 0.03, LR chi 2 (10, 1,100) = 38.98, p < 0.01. Social anxiety (OR = 1.15, p = 0.05) and resilience (OR = 1.25, p < 0.05) both positively predicted viewership. Loneliness was not significantly related to viewership. There were also differences by age and gender (see Table 2), such that females and older participants were more likely to report viewing. Thus, H1c is supported; resilience was positively related to viewership. H1a was not supported; loneliness was not related to viewing. H1b was also not supported; interestingly, social anxiety was positively related to viewing, counter to our predictions.

TABLE 2. Relations Between Individual-Level Risk Factors, Demographic Variables, and Viewership of 13 Reasons Why.

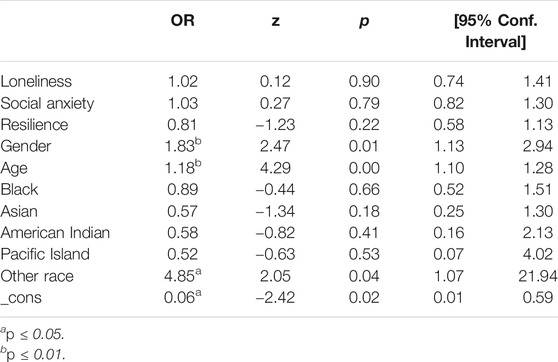

To address H2 and examine how these risk factors were associated with whether individuals viewed the entire first season of 13RW or a portion of episodes, we ran a logistic regression with the complete season viewed as the dependent dichotomous variable (watched entire season or watched less than the entire season), and loneliness, resilience, social anxiety, age, gender, and ethnicity as independent variables. The full model was significant, pseudo R2 = 0.08, LR chi2 (10, 471) = 50.50, p < 0.01. None of the risk factor variables predicted watching all of the episodes. There were differences by age and gender (see Table 3), such that females and older participants were more likely to report viewing all 13 episodes. Thus, H2a-c are not supported; individual-level risk factors were not related to viewing the entire first season.

TABLE 3. Relations Between Individual-Level Risk factors, Demographic Variables, and Entirety of Season Viewed.

Overall, these analyses answered our research question and partially supported our hypotheses. Consistent with the selective exposure framework, the reasons youth chose to view the first season of 13RW were largely related to how interested and/or appropriate they found the content to be, or because those in their friend group watched it or suggested it. Additionally, however, one-fourth to one-third of non-viewing youth recognized that the content may not be relevant or appropriate for them. Indeed, between one-fifth and one-third of non-viewers reported that the content was either too upsetting, inappropriate, or graphic, and thus, was the reason why they chose not to view. Similar to viewers, about one-quarter of non-viewers reported that members of their friend group suggested they not view the series due to the nature of the content. Viewers, however, were likely to report that the content was interesting or that they watched because they saw it while using Netflix. In all, these descriptive findings suggest that viewers may have selectively viewed the series based on their interest in the content as well as their perceptions of the appropriateness of the content.

This conclusion is partially supported through our hypothesis testing. For example, we found a positive relationship between resilience and viewership, suggesting that individuals higher in the feeling that they have the ability to persevere through adverse life events were more likely to view season 1. While there was no relationship between viewing and ratings of loneliness, we did find a positive relationship between social anxiety and viewership, suggesting that individuals higher in social anxiety were more likely to view season 1. This finding ran counter to our prediction. In contrast, H2 was not supported, as only youth demographics of age and gender were related to whether participants watched all of the episodes or only a portion of the episodes in season 1. Therefore, there is some evidence that individual-level risk factors related to participants’ decisions to view season 1 but did not relate to viewing the entire first season of episodes.

Thus, the descriptive and inferential findings of this research study show some general support for the predictions set forth by the selective exposure framework (Zillmann and Bryant, 1985; Sherry, 2001; Sherry, 2004; Sherry et al., 2006). As resilience is characterized by one’s ability to overcome adversity (Jain et al., 2012), it is logical that this individual-level variable would be positively related to viewing. It appears that adolescents and young adults with this ability may have felt more comfortable in dealing with the difficult mental health-related topics portrayed in the 13RW, and thus were more likely to view season 1, in comparison to those lower in resilience. This explanation would also serve to contextualize our null finding pertaining to viewing the entire first season; individual-level factors appear to relate to the decision to view, but once an individual began viewing, individual-factors do not appear to relate to viewing all of the episodes. This might also suggest that resilience is an individual-level factor that may predict adolescent and young adult exposure to other mental health-related media content.

A second key finding is the relationship between social anxiety and viewing. Although our significant finding ran counter to predictions, certain types of youth may opt into watching this series, or television in general, to satisfy a level of peer connection and comfort that they are less comfortable obtaining from live interactions with peers. This is consistent with research of viewers of other platforms including YouTube. For example, social anxiety is related to addictive viewing of YouTube (de Bérail et al., 2019), suggesting that media can fill a void in the lives of youth who are less comfortable in non-mediated interactions with peers. Further, those higher in social anxiety may have been more likely to view 13RW as a function of the nature of the content. Indeed, research studies demonstrate that topics relating to mental health are difficult to discuss (Jorm et al., 2008), and this may be compounded among individuals who already feel a poor sense of social connection with peers (Luhmann and Hawkley, 2016). We note, however, that we did not find a significant relationship between loneliness and viewership. Thus, although loneliness is also characterized by a sense of poor connection with others (Luhmann and Hawkley, 2016), the differences in findings between loneliness and social anxiety may be attributable to an additional sense of anxiety. That is, those who are socially anxious both feel cut off from others, but also feel a sense of self-consciousness and fear when communicating with others (Leary and Kowalski, 1997). Therefore, based on the present findings, it appears that individuals higher in social anxiety may turn to media as a relative safe space to learn about mental health topics. More research is necessary in order to clarify this relationship; however, this finding does suggest the possibility for media to support those at risk for mental health concerns, in addition to those less at risk (e.g., those higher in resilience).

Therefore, this research adds to the literature on adolescent-directed health-related media, which previously has largely focused on the correlates of viewing on physical health. Research on selective exposure, however, provides key information on who views such content, and why they view such content. This type of information can be used to contextualize patterns of relationships and effects, thus providing insight into who is more or less susceptible to viewing and being affected by such programming (see Valkenburg and Peter, 2013). As mental health-related programming becomes more prevalent, it will increasingly be important to consider individuals’ own experiences with mental health, and how they shape viewing decisions and interpretations of different types of portrayals.

This study also adds to the research on the correlates of viewing 13RW, which, to date, have been mixed. When studies sample from small, at-risk samples of adolescents and young adults, results demonstrate that exposure to 13RW relates to maladaptive mental and physical health outcomes (e.g., Hong et al., 2018; PlagerZarin-Pass and Pitt, 2019). Analysis of ecological data initially pointed to an increase in suicides relative to expectations (Niederkrotenthaler et al., 2019; Bridge et al., 2020), but a re-analysis of the Bridge et al. (2020) data showed no such increase (Romer, 2020). Other researchers have concluded that there is little current support for a suicide contagion effect stemming from exposure to fictional media (Ferguson, 2019). In contrast, larger samples of 13RW viewers featuring non-at-risk youth largely show positive outcomes related to mental health (e.g., Ferguson, 2021) or prosocial mental-health related behaviors, such as reaching out to help others (e.g., Carter et al., 2020).

This study is among the first to use a selective exposure framework to examine the antecedents of viewing 13RW, showing that at least some at-risk individuals may have opted not to view the series due to the potential triggering nature of the content. This may especially be the case, as the portrayal of suicide was widely reported in the popular press (e.g., Saint Louis, 2017), and thus, was likely known to the potential viewer or the viewer’s friends. While some viewers certainly appear to have experienced negative outcomes as a function of viewing, as demonstrated in multiple studies (Hong et al., 2018; PlagerZarin-Pass and Pitt, 2019), the present study shows that the scope of these adverse outcomes may have been attenuated somewhat through selective exposure. Other studies show that viewing the series may have positive correlates among non-at-risk viewers (see Carter et al., 2020; Ferguson, 2021). Thus, research that examines the conditions under which and the processes through which media, particularly 13RW, contribute to and mitigate against mental health continue to be vitally necessary. This study, however, adds to the literature on 13RW and adolescent-directed mental health-related programming by considering the characteristics of the audience and how they relate to viewership, especially considering that most existing studies focus on the correlates of viewing. A study involving selective exposure provides information on who viewed, which is especially important when the content focuses on mental health and suicide, and can be used to help contextualize correlates of viewing.

It will be important for future research to examine other risk factors and their role in selective exposure to other series like 13RW, particularly variables such as depression or suicidal ideation. In addition, adolescent-directed mental and physical health programming is quite popular on Netflix currently (e.g., Sex Ed; Insatiable); thus, understanding the antecedents of viewing will continue to be timely. Further, media can influence adolescent development and learning, and may have the power to influence conceptions of adulthood; namely, priorities, expectations around relationships with others and definitions of success (Wartella et al., 2018). Therefore, it is imperative to think about the implications of media use in a way that will help increase understanding of media effects throughout the lifespan. Evidence in our study suggests that future research should examine more individual difference variables that relate to the selection of media content in the first place, rather than only examining the outcomes of those who selectively choose to view the media content.

Limitations. Although this work does provide some insight on how individual-level factors relate to adolescent and young adult viewing of the first season of 13RW, it is not without caveats. First, these data were cross-sectional, thus calling into question the directionality of our findings. We also focused on one show for many of our survey questions. Despite the popularity of the series, there is risk to studying responses to one series due to questions of generalizability. While this is a limitation, we would note that the content of the series is not unique to 13 Reasons Why. Indeed, a number of other series available around the world via Netflix (e.g., Insatiable), as well as in specific countries (e.g., Euphoria), and including movies (To the Bone), have recently begun to include storylines related to mental and physical health in their plots. Further, research has demonstrated that such topics are of great importance to adolescents and young adults around the world (e.g., Lauricella et al., 2018). Third, we note that our statistical effect sizes are small in nature, suggesting that other individual-level characteristics might be important to consider in this context. Future research should continue to examine individual difference variables as they predict media content exposure. Overall, more research is needed to examine not just the outcomes of media consumption among adolescents and young adults, but also the antecedents of use, with particular attention to individual differences in culture, age and context.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

The authors declare that this study received funding from Netflix by way of Zeno Group. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Arendt, F., Scherr, S., Pasek, J., Jamieson, P. E., and Romer, D. (2019). Investigating Harmful and Helpful Effects of Watching Season 2 of 13 Reasons Why: Results of a Two-Wave U.S. Panel Survey. Soc. Sci. Med. 232, 489–498. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.04.007

Arendt, F., Scherr, S., Till, B., Prinzellner, Y., Hines, K., and Niederkrotenthaler, T. (2017). Suicide on TV: Minimising the Risk to Vulnerable Viewers. BMJ 358, j3876. doi:10.1136/bmj.j3876

Ayers, J. W., Althouse, B. M., Leas, E. C., Dredze, M., and Allem, J. P. (2016). Internet Searches for Suicide Following the Release of 13 Reasons Why. JAMA Intern. Med. 177, 1527–1529. doi:10.1186/s13012-016-0390-x10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.3333

Bridge, J. A., Greenhouse, J. B., Ruch, D., Stevens, J., Ackerman, J., Sheftall, A. H., et al. (2020). Association between the Release of Netflix's 13 Reasons Why and Suicide Rates in the United States: An Interrupted Time Series Analysis. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 59 (2), 236–243. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2019.04.020

Brooks, M. (2017). Teen Suicide Experts Blast Netflix Series “13 Reasons Why. Available at: https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/879606 (Accessed February 15, 2020).

Brummelman, E., and Thomaes, S. (2017). How Children Construct Views of Themselves: A Social-Developmental Perspective. Child. Dev. 88, 1763–1773. doi:10.1111/cdev.12961

Carter, M. C., Cingel, D. P., Lauricella, A. R., and Wartella, E. (2020). 13 Reasons Why, Perceived Norms, and Reports of Mental Health-Related Behavior Change Among Adolescent and Young Adult Viewers in Four Global Regions. Communication Research [Epub ahead of print]. doi:10.1177/0093650220930462

Chesin, M., Cascardi, M., Rosselli, M., Tsang, W., and Jeglic, E. L. (2019). Knowledge of Suicide Risk Factors, but Not Suicide Ideation Severity, Is Greater Among College Students Who Viewed 13 Reasons Why. J. Am. Coll. Health 68, 644–649. doi:10.1080/07448481.2019.1586713J. Am. Coll. Health.

Common Sense Media. Kid Reviews for 13 Reasons Why. Available at: https://www.commonsensemedia.org/tv-reviews/13-reasons-why/user-reviews/child. (Accessed March 19, 2021).

Davaasambuu, S., Batbaatar, S., Witte, S., Hamid, P., Oquendo, M. A., Kleinman, M., et al. (2017). Suicidal Plans and Attempts Among Adolescents in Mongolia. Crisis 38, 330–343. doi:10.1027/0227-5910/a000447

de Bérail, P., Guillon, M., and Bungener, C. (2019). The Relations between YouTube Addiction, Social Anxiety and Parasocial Relationships with YouTubers: A Moderated-Mediation Model Based on a Cognitive-Behavioral Framework. Comput. Hum. Behav. 99, 190–204. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2019.05.007

Ferguson, C. J. (2019). 13 Reasons Why Not: A Methodological and Meta‐Analytic Review of Evidence Regarding Suicide Contagion by Fictional Media. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 49, 1178–1186. doi:10.1111/sltb.12517

Ferguson, C. J. (2021). One Less Reason Why: Viewing of Suicide-Themed Fictional media Is Associated with Lower Depressive Symptoms in Youth. Mass Commun. Soc. 24, 85–105. doi:10.1080/15205436.2020.1756335

Garnefski, N., Diekstra, R. F. W., and Heus, P. D. (1992). A Population-Based Survey of the Characteristics of High School Students with and without a History of Suicidal Behavior. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 86, 189–196. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1992.tb03250.x

Hamill, S. K. (2003). Resilience and Self-Efficacy: The Importance of Efficacy Beliefs and Coping Mechanisms in Resilient Adolescents. Colgate Univ. J. Sci. 35, 115–146.

Hanson, T. L., and Kim, J. O. (2007). Measuring Resilience and Youth Development: The Psychometric Properties of the Healthy Kids Survey. Issues & Answers. REL 2007-No. 34. Washington, DC: Regional Educational Laboratory West. doi:10.1037/e607962011-001

Harris, T. L., and Molock, S. D. (2000). Cultural Orientation, Family Cohesion, and Family Support in Suicide Ideation and Depression Among African American College Students. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 30, 341–353. doi:10.1111/j.1943-278X.2000.tb01100.x

Heckhausen, J., Wrosch, C., and Schulz, R. (2010). A Motivational Theory of Life-Span Development. Psychol. Rev. 117, 32–60. doi:10.1037/a0017668

Hefner, J., and Eisenberg, D. (2009). Social Support and Mental Health Among College Students. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 79, 491–499. doi:10.1037/a0016918

Heinrich, L. M., and Gullone, E. (2006). The Clinical Significance of Loneliness: A Literature Review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 26, 695–718. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2006.04.002

Hong, V., Ewell Foster, C. J., Magness, C. S., McGuire, T. C., Smith, P. K., and King, C. A. (2019). 13 Reasons Why: Viewing Patterns and Perceived Impact Among Youths at Risk of Suicide. Psychol. Sci. 70, 107–114. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201800384

Jain, S., Buka, S. L., Subramanian, S. V., and Molnar, B. E. (2012). Protective Factors for Youth Exposed to Violence. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice 10, 107–129. doi:10.1177/1541204011424735

Johnson, J., Gooding, P. A., Wood, A. M., and Tarrier, N. (2010). Resilience as Positive Coping Appraisals: Testing the Schematic Appraisals Model of Suicide (SAMS). Behav. Res. Ther., 48, 179–186. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2009.10.007

Johnson, J., Wood, A. M., Gooding, P., Taylor, P. J., and Tarrier, N. (2011). Resilience to Suicidality: The Buffering Hypothesis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 31, 563–591. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2010.12.007

Jorm, A. F., Morgan, A. J., and Wright, A. (2008). First Aid Strategies that Are Helpful to Young People Developing a Mental Disorder: Beliefs of Health Professionals Compared to Young People and Parents. BMC Psychiatry 8, 42–52. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-8-42

La Greca, A. M., Dandes, S. K., Wick, P., Shaw, K., and Stone, W. L. (1988). Development of the Social Anxiety Scale for Children: Reliability and Concurrent Validity. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 17, 84–91. doi:10.1177/154120401142473510.1207/s15374424jccp1701_11

Lauricella, A. R., Cingel, D. P., and Wartella, E. (2018). Exploring How Teens, Young Adults and Parents Responded to 13 Reasons Why. Evanston, IL: Center on Media and Human Development, Northwestern University.

Luhmann, M., and Hawkley, L. C. (2016). Age Differences in Loneliness from Late Adolescence to Oldest Old Age. Dev. Psychol. 52, 943–959. doi:10.1037/dev0000117

Luther, S. S., Cicchetti, D., and Becker, B. (2000). Research on Resilience: Response to Commentaries. Child. Dev. 71, 573–575. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00168

Masten, A. S. (2001). Ordinary Magic: Resilience Processes in Development. Am. Psychol. 56, 227–238. doi:10.1037//0003-066X.56.3.22710.1037/0003-066x.56.3.227

McNamara, P. M. (2013). Adolescent Suicide in Australia: Rates, Risk and Resilience. Clin. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 18, 351–369. doi:10.1177/1359104512455812

Mueller, A. S. (2019). Why Thirteen Reasons Why May Elicit Suicidal Ideation in Some Viewers, but Help Others. Soc. Sci. Med. 232, 499–501. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.04.014

Niederkrotenthaler, T., Stack, S., Till, B., Sinyor, M., Pirkis, J., Garcia, D., et al. (2019). Association of Increased Youth Suicides in the United States with the Release of 13 Reasons Why. JAMA Psychiatry 76, 933–940. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.0922

Pirkis, J., and Blood, R. W. (2001). Suicide and the Media. Crisis 22, 155–162. doi:10.1027/0227-5910.22.4.15510.1027//0227-5910.22.4.155

PlagerZarin-Pass, P. M., Zarin-Pass, M., and Pitt, M. B. (2019). References to Netflix' "13 Reasons Why" at Clinical Presentation Among 31 Pediatric Patients. J. Child. Media 13, 317–327. doi:10.1080/17482798.2019.1612763

Rich, A. R., and Bonner, R. L. (1987). Concurrent Validity of a Stress-Vulnerability Model of Suicidal Ideation and Behavior: A Follow-Up Study. Suicide Life‐Threatening Behav. 17, 265–270. doi:10.1111/j.1943-278X.1987.tb00067.x

Roberts, R. E., Lewinsohn, P. M., and Seeley, J. R. (1993). A Brief Measure of Loneliness Suitable for Use with Adolescents. Psychol. Rep. 72, 1379–1391. doi:10.2466/pr0.1993.72.3c.1379

Roberts, R. K., Roberts, C. R., and Chen, Y. R. (1998). Suicidal Thinking Among Adolescents with a History of Attempted Suicide. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 37, 1294–1300. doi:10.1097/00004583-199812000-00013

Romer, D. (2020). Reanalysis of the Bridge et al. Study of Suicide Following Release of 13 Reasons Why. PLoS one 15, e0227545. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0227545

Rosa, G. S. d., Andrades, G. S., Caye, A., Hidalgo, M. P., Oliveira, M. A. B. d., and Pilz, L. K. (2019). Thirteen Reasons Why: The Impact of Suicide Portrayal on Adolescents' Mental Health. J. Psychiatr. Res. 108, 2–6. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.10.018

Rubin, L. C. (2014). Mental Illness in Popular Media: Essays on the Representation of Disorders. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company. doi:10.21236/ada598923

Russell, G., and Shaw, S. (2009). A Study to Investigate the Prevalence of Social Anxiety in a Sample of Higher Education Students in the United Kingdom. J. Ment. Health 18, 198–206. doi:10.1080/09638230802522494

Rutter, P. A., Freedenthal, S., and Osman, A. (2008). Assessing Protection from Suicidal Risk: Psychometric Properties of the Suicide Resilience Inventory. Death Stud. 32, 142–153. doi:10.1080/07481180701801295

Saint Louis, C. (2017). For Families of Teens at Suicide Risk, ‘13 Reasons’ Raises Concerns. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/01/well/family/for-families-of-teens-at-suicide-risk-13-reasons-triggers-concerns.html (Accessed February 15, 2020).

Sherry, J. L., Lucas, K., Greenberg, B. S., and Lachlan, K. (2006). “Video Game Uses and Gratifications as Predictors of Use and Game Preference,” in Playing Video Games: Motives, Responses, and Consequences. Editors P. Vorderer, and J. Bryant(Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers) 24, 213–224.

Sherry, J. L. (2004). Media Effects Theory and the Nature/nurture Debate: A Historical Overview and Directions for Future Research. Media Psychol. 6, 83–109. doi:10.1207/s1532785xmep0601_4

Sherry, J. L. (2001). Toward an Etiology of media Use Motivations: The Role of Temperament in media Use. Commun. Monogr. 68, 274–288. doi:10.1080/03637750128065

Stravynski, A., and Boyer, R. (2001). Loneliness in Relation to Suicide Ideation and Parasuicide: A Population-wide Study. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav. 31, 32–40. doi:10.1521/suli.31.1.32.21312

Stroud, N. (2007). Media Effects, Selective Exposure, and Fahrenheit 9/11. Polit. Commun. 24 (4), 415–432. doi:10.1080/10584600701641565

Valkenburg, P. M., and Peter, J. (2013). The Differential Susceptibility to media Effects Model. J. Commun. 63, 221–243. doi:10.1111/jcom.12024

Wartella, E., Lauricella, A., Evans, J., Pila, S., Lovato, S., Hightower, B., et al. (2018). “Digital media Use by Young Children: Learning, Effects, and Health Outcomes,” in Child Psychiatry and the Media. Editors E. Beresin, and C. Olsen (St. Louis, MO: Elsevier).

Windle, G., Bennett, K. M., and Noyes, J. (2011). A Methodological Review of Resilience Measurement Scales. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 9, 8. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-9-8

Yang, K., and Victor, C. (2011). Age and Loneliness in 25 European Nations. Ageing Soc. 31, 1368–1388. doi:10.1017/S0144686X1000139X

Keywords: selective exposure, 13 reasons why, adolescents, young adults, mental health

Citation: Evans JM, Lauricella AR, Cingel DP, Cino D and Wartella EA (2021) Behind the Reasons: The Relationship Between Adolescent and Young Adult Mental Health Risk Factors and Exposure to Season One of Netflix’s 13 Reasons Why. Front. Hum. Dyn 3:600146. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2021.600146

Received: 28 August 2020; Accepted: 25 May 2021;

Published: 09 June 2021.

Edited by:

Kaveri Subrahmanyam, California State University, Los Angeles, United StatesReviewed by:

Christopher J. Ferguson, Stetson University, United StatesCopyright © 2021 Evans, Lauricella, Cingel, Cino and Wartella. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jabari Miles Evans, amFiYXJpZXZhbnMyMDIwQHUubm9ydGh3ZXN0ZXJuLmVkdQ==; Drew P. Cingel, ZGNpbmdlbEB1Y2RhdmlzLmVkdQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.