- 1School of Education, University of California, Irvine, CA, United States

- 2Psychology Department, University of California, Santa Cruz, CA, United States

Middle school is a period when young adolescents become more engaged with social media and adults become increasingly concerned about such use. Although research finds that parents often post about their children on social media, little is known about how adults’ social media behaviors relate to youths’ online behaviors. We surveyed 466 middle-school students about their social media habits, privacy-respecting behaviors, and their parents’, other adults’, and their own posting behaviors on social media. While 68% used social media, only 41% posted pictures. Of those, 33.5% also had parents and/or adults that posted about them. Using this subset, we found that adults’ privacy-respecting behaviors (e.g., asking permission to post, showing post first) were significantly related to youth using these same privacy-respecting behaviors when posting on social media. Like many areas of development, young adolescents may learn about social media use by modeling their parents’ and other adults’ behaviors.

Introduction

Research finds that youth are overwhelmingly using social media and that use increases drastically during the middle school years (Pew Research Center, 2018). This increased usage has caused concern about how youth protect their privacy when connecting with others online, who may or may not be known to them (Wisniewski et al., 2015; Shin and Kang, 2016). While recommendations about teaching privacy are plentiful, little of it considers how youths’ digital behaviors may mirror the online activities of important adults in their lives, such as parents. Decades of research have robustly demonstrated that youths’ media habits are often congruent with their parents. For instance, studies of television have found that parents’ television (TV) viewing habits predict their children’s viewing habits more than access to TV or having a TV in the bedroom (Saelens et al., 2002; Yalçinet al., 2002; Gorely et al., 2004; Davison et al., 2005; Jago et al., 2013). One possible explanation is the influence of parental modeling on children’s development (Tizard and Hiughes, 1984). Though robustly shown to influence traditional media habits (e.g., Gorely et al., 2004), the association between adults’ and young adolescents’ new media habits have not been well studied. Thus, we explore how middle-schoolers’ online posting behaviors might relate to their parents’ and other important adults’ privacy-respecting posting behaviors on social media.

Learning Through Modeling

From the earliest ages, children look to important adults around them to learn how to interact, behave, speak, and so on (Tizard and Hiughes, 1984; Gopnik, 2012). This finding exists in a variety of developmental perspectives, from social-cognitive theories of modeling (Bandura, 1971) to sociocultural perspectives of guided participation (Rogoff, 1991). Given this consistent pattern of learning and development, it would make sense that young adolescents, who are new users of social media (Martin et al., 2018; Pew Research Center, 2018), would look to important adults around them for guidance on how to engage with these sites. This might be especially relevant when considering behaviors that are privacy-respecting, such as thinking about what is posted and getting permission before posting about others. Therefore, we surveyed young adolescents about their posting behaviors and the behaviors of their parents and other important adults.

Methods

Sixth, seventh, and eighth graders (n = 466) in two middle schools in the Southeastern region of the United States completed anonymous online surveys in their homeroom or advisement class.

Measurement

Students reported on their demographic characteristics (gender, age, and ethnicity) and what types of social media they used most frequently. They were also asked whether their parent(s) and/or other adults ever posted photos of them on social media. If they selected yes, they were asked how often their parents and other important adults 1) show you what was posted, 2) ask your permission before they post, and 3) share private information about you. Response options included “never,” “sometimes,” and “always.” These answers were summed with “share private information” reverse coded. Thus, higher total scores indicated more privacy-respecting behaviors. Youth were also asked if they ever posted pictures of friends on social media. If yes, they were asked how often they 1) showed the picture first and 2) asked permission. Response options were also “never,” “sometimes,” and “always.” These posting behaviors were totaled into a privacy-respecting score as well.

Analytic Plan

First, the frequency of use of different types of social media was calculated. Then an analytic sample of students who posted on social media and had parents or other adults that posted on social media was created (n = 166 students). To determine if adult privacy-respecting behaviors were associated with tweens’ privacy-respecting behaviors, ordinary least square (OLS) regressions were run with youths’ privacy-respecting behaviors as the dependent variable and adults’ privacy-respecting behaviors as the predictors. Covariates included gender, age, and ethnicity (white, not white).

Results

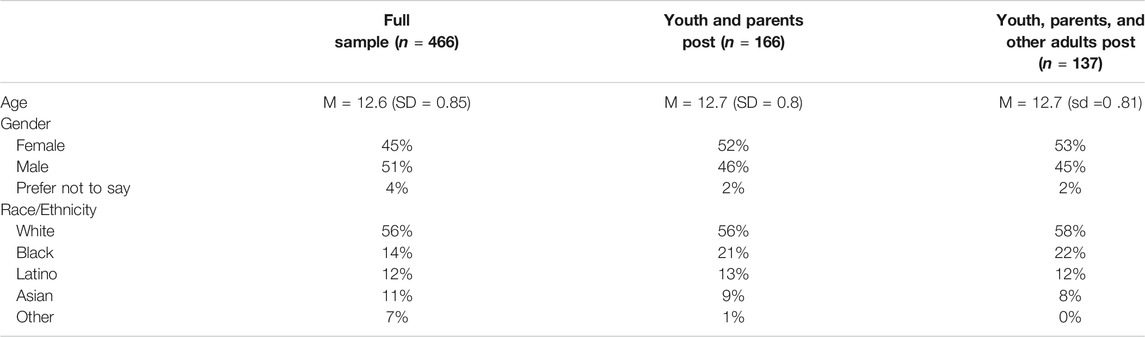

The 466 students that participated ranged from 11 to 14 years (Mage = 12.6 (sd = 1.33)), with 45% being female (4% preferring not to share gender) and about half (56%) being White, 14% Black, 12% Latinx, and 11% Asian. Of these students, 68% used social media. Instagram was the most popular site (55%), followed by Snapchat (48%), and TikTok (22%). Of the full sample, 191 posted on social media. These posting youth tended to be slightly older, have a parent that posted about them, and be female and non-White, compared to their non-posting peers. Of those youth who post, 166 reported that their parents posted images of them on social media accounts and 148 reported that other adults posted images as well. In total, 137 adolescents reported posting on social media and having parents and other adults post about them. From this, two analytic samples (166 youth that post images and have parents that post; 137 youth, parents, and other adults all post; see Table 1 for details) were created to assess how adults’ privacy-respecting posting behaviors related to youths’ online posting behaviors.

Adult Posting Habits

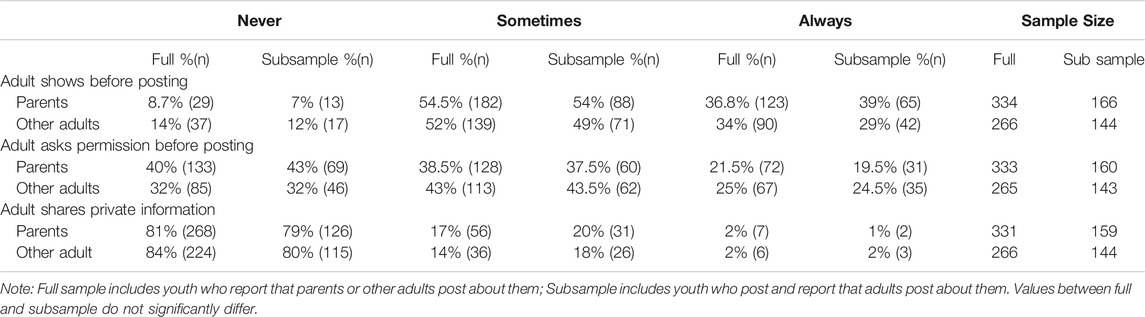

Across the full sample of youth whose parents and other adults post images of them, 40% and 32% respectively never asked permission prior to posting. Most did show the youth the photo at least some of the time (91% parents and 86% other adults) and parents and other adults rarely shared private information about the youth in their posts (19% parents, 16% other adults). See Table 2 for details.

Parent and Adult Behaviors Predicting Posting Behaviors

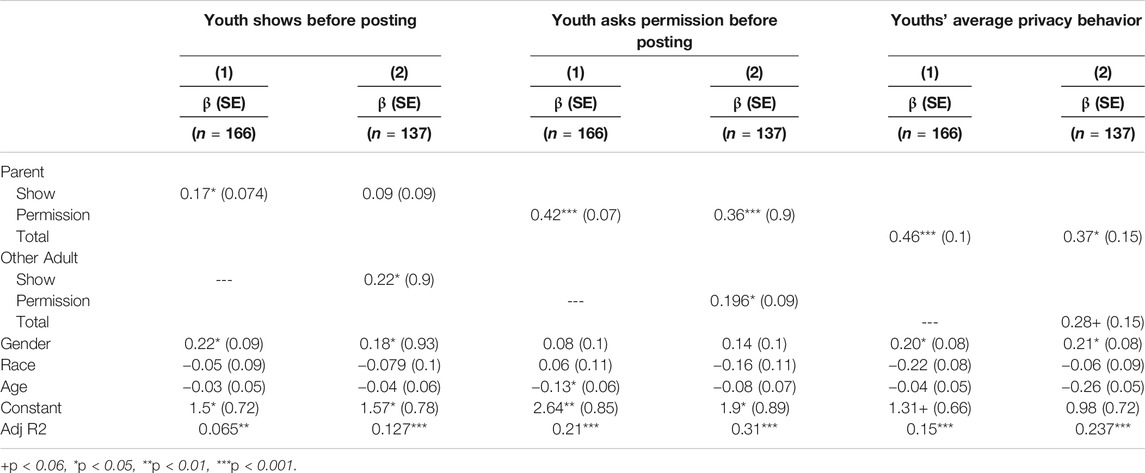

The posting behaviors of parents and other important adults were significantly associated with tweens’ posting behaviors. When parents showed their child the post before posting, their child was also more likely to show their friends pictured in the photo before posting (B = 0.17, SE = 0.07, p = 0.02). Similarly, when parents asked their child for permission before posting, their child also tended to ask others’ permission prior to posting (B = 0.36, SE = 0.09, p < 0.0001). When parents’ total privacy-respecting behaviors were higher, so were their children’s (B = 0.46, SE = 0.1, p < 0.0001). Other adults’ behaviors were also significantly related to youths’ posting behaviors. When they showed photos prior to posting, so did youth (B = 0.22, SE = 0.09, p = 0.016). When they asked permission before posting, so did youth (B = 0.196, SE = 0.09, p = 0.038). Gender and age were also related to posting behaviors, with females and older participants engaging in more privacy-respecting behaviors. See Table 3 for details.

TABLE 3. OLS Regression testing if parent and other adults’ behaviors predict youths’ posting behaviors.

Discussion

This survey of middle-school students’ social media use found that more youth report using social media than posting on social media (315 vs. 191). This pattern of viewing more than posting aligns with findings from Pew’s recent survey of US youth (13–17 years) (Pew Research Center, 2018). Others also find more lurking (i.e., viewing without posting or commenting) than posting in early adolescence (Len-Ríos et al., 2016).

In our sample, ¾ of parents posted images of youth on social media and almost 60% of youth reported other adults posted images of them as well. Thus, youth have an online presence, even if they do not have an account or post themselves. While parents and other adults tend not to share private information, they do not always ask permission to post about these tweens or even show the youth the post first. Thus, many young adolescents have an online presence that they did not create and do not control. In considering youths’ digital privacy, the behaviors of parents and other adults should be included. Other studies of parental sharing about children on social media have found that parents often post images and content about their children (Ammari et al., 2015; Ouvrein and Verswijvel, 2019) and many parents think they should ask permission more often than they actually do (Moser et al., 2017). Our findings provide one more reason why asking permission might be valuable. Results also highlight the importance of considering other adults, such as relatives and family friends.

Though few demographic characteristics were available in this anonymous dataset, it is worth noting that females were more likely to show images to friends before posting and engage in more privacy-protecting posting behaviors. Other studies have found that adolescent females, compared to males, spend more time editing photos and carefully considering what is posted (Dhir et al., 2016; Yau and Reich, 2019). Thus, it is likely that this consideration around sharing extends to sharing about their peers as well. Age was only related to asking permission before posting, with older middle schoolers being more likely to ask. Though not well studied, there is some evidence that friendship maintaining posting behaviors can relate to feelings of closeness which then predicts friendship maintaining posting behaviors (Rousseau et al., 2019). Perhaps 8th graders were further along in their cycle of peer closeness and relationship maintenance posting behaviors than those in younger grades.

Slightly over 1/3 of the sample had posted on social media and had their own image posted by others. Not surprisingly, parents and other adults’ posting behaviors were related to youths’ posting behaviors. Developmental theories robustly demonstrate the myriad ways in which youth learn from others (Bandura, 1971; Tizard and Hiughes, 1984; Rogoff, 1991; Gopnik, 2012). Posting behaviors on social media may be one more area in which youth look to important people in their life to learn how to engage with these sites. To date, most research exploring how parents model and support children’s media habits have focused on young children (Coyne et al., 2017), with research on older children targeting mediation and monitoring practices (Wisniewski et al., 2015). These findings suggest that adult behavior may indirectly shape adolescents’ privacy practices, highlighting an important aspect of how youth might learn about privacy online.

Limitations

Given the age of the participants, most of the sample did not post on social media, even though many were using social media platforms. This limited our analytic sample and subsequently our ability to test for smaller effects. As a cross-sectional study, the association between adults’ social media behaviors and youths’ is not causal. Additionally, the use of self-report introduces the risk of errors in memory, knowledge, and interpretation. Also, the selection of youth in the Southeastern U.S. limits the generalizability of findings to youth in other regions.

Conclusion

Even with these limitations, this exploratory survey study of middle-schoolers’ social media use and posting behaviors provide insights into areas to consider when parenting around social media. Rather than rules or direct instruction, adults could model what we hope our children will do—consider others’ privacy when engaging online.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because these data were collected as part of a research practice partnership by the school partners. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Stephanie Reich (c21yZWljaEB1Y2kuZWR1).

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the University of California, Irvine Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent from the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the design of the study, creation of the survey, and analysis and interpretation of the data. The second author facilitated data collection. The first author drafted the initial manuscript and the three other authors helped with revisions.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Ammari, T., Kumar, P., Lampe, C., and Schoenebeck, S. (2015). Managing Children’s Online Identities: How Parents Decide what to Disclose about Their Children Online. Seoul, Korea: Paper presented at the Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. doi:10.1145/2702123.2702325

Coyne, S. M., Radesky, J., Collier, K. M., Gentile, D. A., Linder, J. R., Nathanson, A. I., et al. (2017). Parenting and Digital Media. Pediatrics 140 (s112), S112–S116. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-1758N

Davison, K. K., Francis, L. A., and Birch, L. L. (2005). Links between Parents' and Girls' Television Viewing Behaviors: A Longitudinal Examination. J. Pediatr. 147 (4), 436–442. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.05.002

Dhir, A., Pallesen, S., Torsheim, T., and Andreassen, C. S. (2016). Do age and Gender Differences Exist in Selfie-Related Behaviours? Comput. Hum. Behav. 63, 549–555. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.053

Gopnik, A. (2012). Scientific Thinking in Young Children: Theoretical Advances, Empirical Research, and Policy Implications. Science 337 (6102), 1623–1627. doi:10.1126/science.1223416

Gorely, T., Marshall, S. J., and Biddle, S. J. H. (2004). Couch Kids: Correlates of Television Viewing Among Youth. Int. J. Behav. Med. 11 (3), 152–163. doi:10.1207/s15327558ijbm1103_4

Jago, R., Sebire, S. J., Edwards, M. J., and Thompson, J. L. (2013). Parental TV Viewing, Parental Self-Efficacy, Media Equipment and TV Viewing Among Preschool Children. Eur. J. Pediatr. 172, 1543–1545. doi:10.1007/s00431-013-2077-5

Len-Ríos, M. E., Hughes, H. E., McKee, L. G., and Young, H. N. (2016). Early Adolescents as Publics: A National Survey of Teens with Social Media Accounts, Their Media Use Preferences, Parental Mediation, and Perceived Internet Literacy. Public Relations Rev. 42 (1), 101–108. doi:10.1016/j.pubrev.2015.10.003

Martin, F., Wang, C., Petty, T., Wang, W., and Wilkins, P. (2018). Middle School Students’ Social Media Use. Educ. Tech. Soc. 21 (1), 213–225.

Moser, C., Chen, T., and Schoenbeck, S. (2017). Parents’ and Children’s Preferences about Parents Sharing about Children on Social Media. Denver, CO: Paper presented at the CHI. doi:10.1145/3025453.3025587

Ouvrein, G., and Verswijvel, K. (2019). Sharenting: Parental Adoration or Public Humiliation? A Focus Group Study on Adolescents' Experiences with Sharenting against the Background of Their Own Impression Management. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 99, 319–327. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.02.011

Pew Research Center (2018). Teens, Social Media & Technology 2018. Retrieved from https://www.pewinternet.org/2018/05/31/teens-social-media-technology-2018/.

Rogoff, B. (1991). “Social Interaction as Apprenticeship in Thinking: Guided Participation in Spatial Planning,” in Perspectives on Socially Shared Cognition. Editors L. B. Resnick, J. M. Levine, and S. D. Teasley (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 349–364.

Rousseau, A., Frison, E., and Eggermont, S. (2019). The Reciprocal Relations between Facebook Relationship Maintenance Behaviors and Adolescents' Closeness to Friends. J. Adolescence 76, 173–184. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.09.001

Saelens, B. E., Sallis, J. F., Nader, P. R., Broyles, S. L., Berry, C. C., and Taras, H. L. (2002). Home Environmental Influences on Children’s Television Watching from Early to Middle Childhood. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 23 (3), 127–132. doi:10.1097/00004703-200206000-00001

Shin, W., and Kang, H. (2016). Adolescents' Privacy Concerns and Information Disclosure Online: The Role of Parents and the Internet. Comput. Hum. Behav. 54, 114–123. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.07.062

Wisniewski, P., Rosson, M. B., Jia, H., Xu, H., and Carroll, J. M. (2015). Preventative’ vs. “relative”: How Parental Mediation Influences Teens’ Social Media Privacy Behaviors. Vancouver: Paper presented at the CSCW. doi:10.1145/2675133.2675293

Yalçin, S., Tugrul, B., Naçar, N., Tuncer, M., and Yurdakok, K. (2002). Factors that Affect Television Viewing in Preschool and Primary Schoolchildren. Pediatr. Int. 44, 622–627. doi:10.1046/j.1442-200X.2002.01648.x

Keywords: social media, modeling, early adolescence, privacy, privacy-respecting behaviors, posting

Citation: Reich SM, Starks A, Santer N and Manago A (2021) Brief Report–Modeling Media Use: How Parents’ and Other Adults’ Posting Behaviors Relate to Young Adolescents’ Posting Behaviors. Front. Hum. Dyn 3:595924. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2021.595924

Received: 18 August 2020; Accepted: 21 April 2021;

Published: 05 May 2021.

Edited by:

Kaveri Subrahmanyam, California State University, Los Angeles, United StatesReviewed by:

Kathryn Modecki, Griffith University, AustraliaLarry Rosen, California State University, Dominguez Hills, United States

Copyright © 2021 Reich, Starks, Santer and Manago. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Stephanie M. Reich, c21yZWljaEB1Y2kuZWR1

Stephanie M. Reich

Stephanie M. Reich Allison Starks

Allison Starks Nicholas Santer

Nicholas Santer Adriana Manago

Adriana Manago