- 1Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, Haale, Germany

- 2Centre Maurice Halbwachs, École Normale Supérieure, Paris, France

In the last decade the number of countries aiming to resettle refugees increased and complementary pathways aiming to relocate humanitarian migrants expanded. Stakeholders in charge of the selection process of candidates and logistical organization of these programs multiplied as a consequence. Because refugee resettlement and complementary pathways are not entrenched in international law, selection processes and logistical organization are at the discretion of stakeholders in charge, sometimes hardly identifiable themselves, and can vary greatly from one scheme to another. For displaced candidates to resettlement and complementary pathways, this opacity can have dramatic consequences in regions of origin. This article will present the case of a group of African lesbian and gay asylum seekers who first sought asylum in a neighboring country, hoping for resettlement to the global North. Because their first country of asylum criminalizes homosexuality, the responsible regional office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) must circumvent the said country’s sovereignty on asylum matters and recognize LGBT asylum seekers as refugees under UN mandate before submitting their cases to resettlement countries. UNHCR agents thus conduct refugee status determination (RSD) and resettlement procedures behind a veil of secrecy, at the risk of antagonizing their local partners and confusing aspiring refugees. Meanwhile, INGOs from the global North cooperate with local LGBT associations to relocate LGBT Africans out of the same African countries. This paper will show African asylum asylum seekers’ efforts to qualify for all these programs simultaneously, unaware of the mutually exclusive aspects of some; to become visible to institutions and “sponsors” they deem more powerful, at the expense of solidarity within their group.

Introduction

The multiplication of programs of resettlement and complementary pathways but also of diverse stakeholders involved in their implementation has implications in regions of origin which have not yet been sufficiently researched. Based on an ethnography conducted in the African country3 of first asylum with UNHCR resettlement case workers and LGBT asylum seekers4 from a neighboring country aspiring to resettlement, this article offers to shift the gaze from regions of destination to regions of origin. I argue that UNHCR international staff maintains the resettlement process behind a veil of secrecy for fear that the program would be jeopardized by their local partners. This secrecy has unintended consequences for beneficiary refugees, who struggle to navigate between similar programs running simultaneously but sometimes with mutually exclusive criteria for inclusion.

States of the Global North have made on soil asylum applications increasingly difficult through tightened border controls, externalization of borders outside of their territories, stricter asylum procedures and hardened living conditions for asylum seekers. Notably in Europe in the wake of the political migration crisis of 2015, debates polarized around the need to establish safer pathways to migration. Migrants are selected in regions of origin and brought in legally, as a complement -or even as an alternative-to the right to claim asylum on European soil following an illegal entry (Hashimoto, 2018). To develop such alternative pathways, states of the Global North revive long-established programs like UNHCR refugee resettlement (European states have notably committed to resettling five time more refugees in 2018 than in 2008)5, replicate programs in place in other countries like private or blended sponsorship and launch new initiatives like emergency evacuations coupled with humanitarian admission programs (the EU initiated such a program to evacuate migrants detained in Libya). By speaking of “refugee resettlement and complementary pathways” one refers to very diverse programs which all have in common to be initiated by states of destination (most of them located in the Global North, see Cellini, 2018) or in cooperation with states of destination (in cases of private and blended sponsorship).

Historically states committed to resettling refugees have turned to the UNHCR to conduct the selection and preparation of resettlement candidates6, relying on the UN agency’s presence in regions of origin and knowledge of displaced populations (Garnier et al., 2018). However fragile its position as international protection actor is in the resettlement process (as resettlement is not codified in hard international law), the UNHCR took on the role of selection partner for resettlement states. With the increase in the number of countries launching resettlement programs and the multiplication of types of complementary pathways, the UNHCR had to expand its partnerships with NGOs, delegating responsibilities “such as identification of resettlement cases and preparation of resettlement submissions” (Garnier et al., 2018) and develop stronger ties with the private sector for the promotion of privately sponsored refugee resettlement (Garnier, 2016).

With this study of relations between a UNHCR regional office and its local partners (country office and partner NGO) in an African city on the one hand and on the other of beneficiarie’s understanding of resettlement and complementary pathways, I intend to contribute to two interconnected bodies of scholarship. The first is resettlement selection in regions of origin and the second pertains to refugees perceptions of refugee governance. Scholarship on refugee resettlement has evolved greatly in the past decades to overcome its original bias towards resettlement countries of the Global North. Most of the now numerous studies set in the Global South analyze resettlement selection in camps settings (see for example Ikanda, 2018; Thomson, 2012). Cities of the Global South offer particularly rich field sites to study local implementation of resettlement processes because of the presence of institutional actors’ headquarters (UNHCR, state of first asylum, local NGOs). With this research based in an African metropole, I wish to contribute to existing scholarly efforts to shed light on power relations between actors of resettlement processes in regions of origin (see for example Fresia, 2009a in Senegal; Vera Espinoza, 2018 in Chile and Brazil; Welfens and Bonjour, 2020 in Turkey). The second body of scholarship I draw on for this piece concerns asylum seekers’ knowledge and perception of refugee governance. My argument on LGBT resettlement candidates’ risky efforts to conform to multiple opaque and sometimes contradictory selection criteria builds on existing literature on resettlement candidates’ navigation of “black boxes of bureaucracy” in regions of origin (Broqua et al., 2020; Koçak, 2020; Saleh, 2020; Thomson, 2012).

Case Study and Methods

My research participants fled from their country of origin (country A) to a neighboring county on the African continent (country B), which is party to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol without reservation. At the end of the 1960’s a law established a National Commission of Eligibility (CNE) in country B. The state thus sovereignly decides whether or not to recognize individual asylum seekers as refugees, even though the UNHCR sits as an observer in the CNE and provides the CNE with funding for its running costs. The UNHCR also funds the NGO Africanrésilience7, its main implementing partner in country B for the past 30 years, in charge of orienting asylum seekers and refugees within the asylum system and providing punctual material and financial assistance. The city of this case study, the capital of country B, is also host to the headquarters of the UNHCR for the African region.

In 2017 I started an ethnography of the asylum system in this cosmopolitan African city and conducted participant observation within the office of the NGO Africanrésilience for several months. There I got acquainted with the complex situation of a specific population “of concern” to the UNHCR: LGBT asylum seekers and refugees8, most of whom had fled from the neighboring country A under the fierce dictatorship of a head of state notorious for his homophobic state violence. In country B, LGBT asylum seekers have no hope of being awarded a refugee status on the base of the homophobic persecution they faced in their country of origin, as country B itself criminalizes same-sex relationships, punishable by fines and prison. For the UNHCR regional office overseeing these African countries, the dilemma is of size: according to its RSD guidelines, LGBT asylum seekers can be recognized as refugees provided that their “membership to a particular social group” can be established and that the harm they suffered amounted to persecution on the base of their sexual orientation or gender identity. However, and like for all its field offices, the UNHCR activities in country B depend on its good diplomatic relationships with its government. The UNHCR thus had to discretely find “durable solutions” for these asylum seekers who are criminals according to the laws of country B: resettlement to states of the Global North appeared as the best solution.

At the end of my participant observation within the NGO Africanrésilience’s office, I dedicated the remaining 7 months of my fieldwork to following a group of LGBT asylum seekers in their daily lives in transit in country B’s capital to grasp—mainly through participant observation and semi-structured interviews—their understanding of the asylum system and selection criteria for resettlement and the impact thereof on their group dynamic. Simultaneously I conducted semi-structured and structured interviews with UNHCR agents working in (or who had formally worked in) the resettlement unit of the regional office as well as UNHCR agents of the country office and analyzed files produced by these different instances on LGBT asylum seekers (documentation of asylum claims, rejection letters).

Conducting research with refugees must be preceded by a clear ethical road map. As I explain elsewhere (Menetrier, Forthcoming), my positioning is this of a “triple imperative” (building on Jacobsen and Landau, 2003; Krause, 2017, 22–24) concerning researchers’ responsibility to peer scholars, humanitarian agencies and research participants. More concretely, the data used in this publication was collected during semi-structured interviews with UNHCR and NGO staff aware of my research project who agreed to share information under cover of anonymity. Their names and other identification details have thus been changed, most of them work in different locations by now. Similarly, asylum seekers and refugees whose stories feature in this publication chose to participate in the study. Their names have been changed, temporal and spatial details on their specific trajectories were only shared when they could not lead to an identification of specific individuals.

Results

A New Decision-Making Chain for LGBT Resettlement

The UNHCR regional office in charge of operation in countries A and B decided to negotiate the resettlement of LGBT asylum seekers with states of the Global North who had committed to quotas for resettlement from the region. The head of the resettlement unit led negotiations directly with immigrations officers of resettlement states, trying to obtain provisional consent for the resettlement of a given number of LGBT asylum seekers even before submitting their files. A resettlement case worker recalled negotiations with Sweden:

“[…] in a particular year they had no places but anyway we are talking about small numbers of cases so, you can always advocate I mean one or two people, you tell them “it is lifesaving, please proceed and accept them” you know … ” (December 10, 2019)

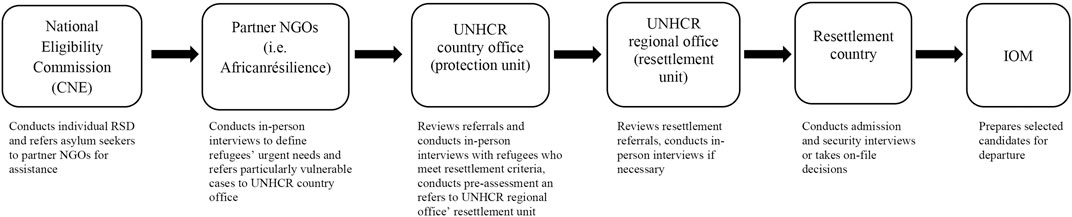

Once a number of resettlement spots was secured, the protection unit of the UNHCR regional office conducted RSD of a corresponding number of asylum seekers, recognizing them as refugees under UNHCR mandate (indeed only cases of recognized refugees can be submitted to the resettlement unit). The UNHCR regional office9 was thus not only cross-cutting the CNE, thereby circumventing country B’s sovereignty in asylum matters10, but also cross-cutting the UNHCR country office. Indeed, the latter was usually in charge of conducting RSD for beneficiaries who fled to country B, identifying together with its implementing partner the NGO Africanrésilience those with resettlement needs, then forwarding their cases to the resettlement unit of the regional office (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. Regular process of refugee selection for resettlement from country B, based on fieldwork insights.

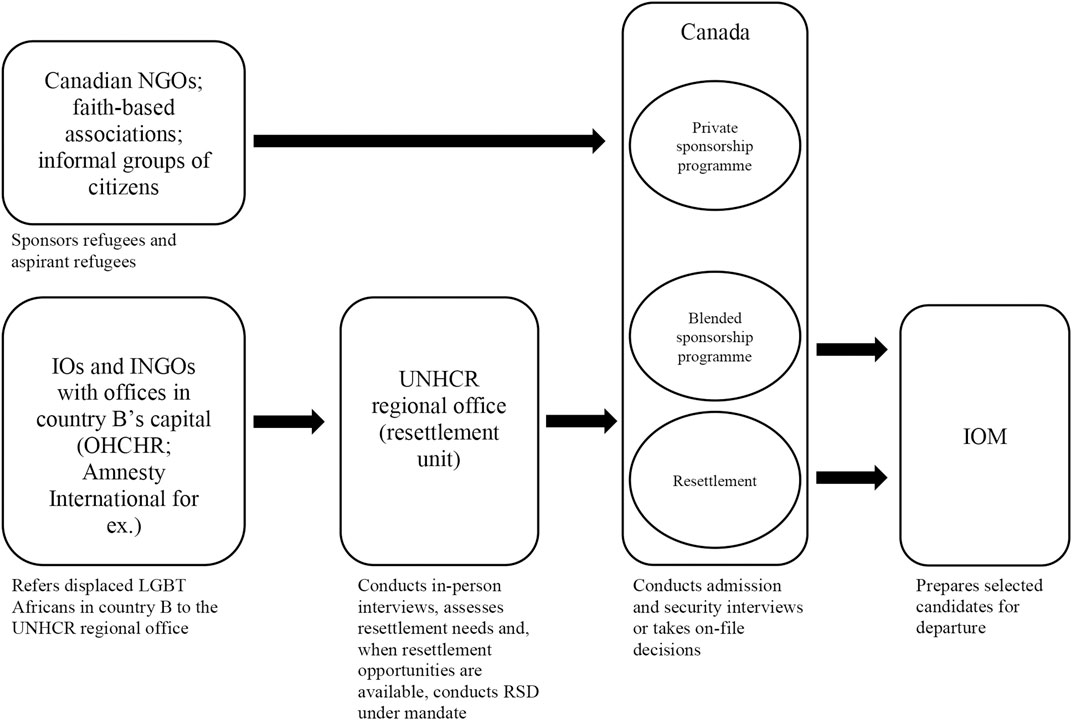

In the case of LGBT asylum seekers arriving from neighboring country A however, the UNHCR regional office proceeded autonomously (Figure 2). Resettlement agents awarded “mandate” refugee statuses to LGBT asylum seekers only after obtaining resettlement states’ informal acceptance. They referred to this procedure as “fast-track” resettlement for “urgent” cases. In periods of scarce resettlement opportunities for refugees from Africa, the UNHCR regional office postponed the “mandate” RSD process for LGBT asylum seekers. In such periods, LGBT asylum seekers in transit in country B thus did not count as “persons of concern” to the UN agency. The UNHCR regional office ran the fast track resettlement of LGBT cases without their country office nor their partner NGO. They feared that their African colleagues would slow down the process because of their presumed reluctance to see LGBT asylum seekers as a priority. Anna, a resettlement caseworker I interviewed in the African city, phrased relationships with the country office as such:

FIGURE 2. Process of refugee selection for LGBT resettlement and complementary pathways from country B, based on fieldwork insights.

“I am 100% certain that [country B] office is not the only office with this problem … no matter how much we say what LGBT, gender means and all that bullshit, there are a lot of homophobic people here. So its like that and some are better than others … but it’s very difficult to pinpoint it to homophobia when they say “ohh I just didn’t realize that it was this serious and blab la bla, kind of you know we didn’t asses this person to be vulnerable, we didn’t think that there was serious protection needs” (December 3, 2017)

Anna suspects her African colleagues to disrespect standard operating procedures in place for resettlement selection because of their personal aversion towards LGBT individuals from neighboring country A. She did not apply the same critique towards her “expatriate” colleagues and her own categorization of LGBT asylum seekers as “urgent” resettlement cases even prior to their assessment, verification and conduct of interviews. For UNHCR agents of the regional office, the noble goal of efficiently processing the resettlement of LGBT asylum seekers out of Africa legitimized circumventing local partners. Sandvik calls “informal normativities” this interweaving of transactions usually deemed illegal into the matrix of resettlement practice as a response to internal and external pressures (2011, 2012).

Employees of the NGO Africanésilience and of the UNHCR country office were themselves trained by the UNHCR regional office to strictly respect the resettlement chain when referring candidates profiles. They learned that their expertise relies on their ability to take purely legal and objectified decisions (Fresia and Von Känel, 2016) in accordance with the UN agency’s standards of transparency (Thomson, 2012), fairness and impartiality (Fresia, 2009b; Fresia and Von Känel, 2016). The UNHCR resettlement handbook advises that “information meetings may be held to inform refugees and resettlement partners of the standards and procedures governing the resettlement process in a given field office.” (UNHCR, 2011, 121). No such meeting was organized in the case of LGBT resettlement in country B. Employees of the NGO Africanrésilience learned through rumors that some of the LGBT asylum seekers from country A who once came to her office asking for financial and material assistance were now living in Canada and Sweden. An employee of the NGO Africanrésilience complained to me: “They [LGBT asylum seekers] were in a program that was running in secret. We could not even localize it, their office and all … I did everything I could to meet them.” (February 1, 2018). National employees of Africanrésilience and of the UNHCR country office are on local precarious contracts with low wages compared to most of their colleagues of the UNHCR regional office who are international “P-staff” in the UN system (Fresia, 2009b, 181). Their salary and passport do not allow them to travel easily to the Global North. They thus view resettlement to the Global North as a rare privilege, not only for refugees but for Africans in general. When I asked them about their willingness to assess resettlement needs of LGBT asylum seekers in a state which criminalizes homosexuality, they responded that it was their mandate to “assist ALL asylum seekers on an equal footing” (March 26, 2018). They interpreted the opacity surrounding LGBT asylum seekers’ departure to the Global North as a sign that the international staff of the regional office had something to hide. In the absence of information, they assumed that LGBT asylum seekers were unfairly privileged for resettlement in violation of the principles of fairness, impartiality and transparency preached by the UNHCR itself. Local partners are usually what I called elsewhere “street-level humanitarians” (Menetrier, 2017). On the front-line of refugee assistance, they represent the human figure of the resettlement bureaucracy behind which UNHCR agents’ responsibility is shirked (Thomson, 2012, 198). Leaving out local partners from the adapted resettlement procedure for LGBT asylum seekers in country B had negative although unintended consequences on asylum seekers’ access to information about the procedure.

LGBT Resettlement Aspirants’ Access to Information

Without the local mediators’ translation, resettlement candidates were left with their own interpretation of the successive steps towards resettlement and the diverse institutions involved in the decision-making process. Because UNHCR agents of the regional office only interviewed LGBT asylum seekers when they were almost certain to be able to resettle them quickly, during periods of scarce resettlement spots LGBT asylum seekers spent months, in certain cases several years in country B before meeting a UNHCR agent. Obtaining a first interview with an agent of the UNHCR regional office was thus LGBT asylum seekers’ dearest hope. Not knowing what the variation in procedure duration was due to, LGBT asylum seekers could only speculate and establish theories about specific UNHCR agents’ decision-making power and willingness to resettle LGBT Africans (Menetrier, 2019). Because most resettlement case workers were from the Global North while Africanrésilience and country office’s agents were African, they concluded that being interviewed by a white-skinned agent increased their chances for resettlement to the Global North. It prompted many of the LGBT asylum seekers who were not fluent in English to choose the latter as interview language instead of their local languages, in the hope to be allocated a non-African interviewer, often eventually at the cost of the “coherence” of their story of flight.

The opacity around the resettlement procedure, criteria and decision-makers extended to complementary pathways. For LGBT Africans aspiring to relocate to the Global North, they were indeed impossible to distinguish from one another: in all cases were countries of destination distant places in the Global North, decision-makers seemed to be unattainable white expatriates11, criteria and procedure appeared behind a veil of secrecy. What LGBT asylum seekers in transit in country B knew about resettlement and complementary pathways to the Global North came from informal discussions in the house they shared in the suburbs of country B’s capital and revolved around the experience of friends and acquaintances who had fled country A before them, started these procedures earlier and were now either undergoing the last screening before departure or already in their final country of destination.

Misunderstanding Blended Sponsorship Programs

Among the group of LGBT Africans freshly established in Canada, Paul often video-called his friends who remained in country B’s capital and bragged about his “new family” in Canada, sending selfies taken with his “mother” in the nicely furnished apartment or in the SUV car. Ben S, who was himself in the very first stages of the asylum procedure in country B became persuaded that accelerating his asylum procedure and reaching Canada faster would necessitate such a support by Canadian citizens: “Agathe, please help me find a private sponsor like Paul” he often urged me (October 26, 2017). Obsessed by this search, Ben S. spent much time on social media and in touristic places of country’s B cosmopolitan capital in the hope to convince citizens of the Global North to “sponsor” him to relocate to their country of residence.12 He neglected his own asylum procedure, forgetting to honor meetings with Africanrésilience social workers or with agents of the UNHCR country office, considering that the concrete assistance would come from “private sponsors.” Very suspicious of his fellow LGBT asylum seekers with whom he considered to be in competition for scarce resettlement spots, Ben S. thought that Paul was jealously keeping the secret of his access to Canadian private sponsors to himself. What he did not understand is that Paul had himself gone through each step of the resettlement program put in place by the UNHCR regional office in country B and been selected for resettlement by the Canadian High Commission (CHC). Only then was he enrolled in a blended sponsorship program because, as LGBT Christian from a Muslim-majority African country, he had (unlike his Muslim friends with whom he fled country A) a particularly fitting profile for faith-based groups willing to “sponsor” refugees in Canada. Ben S. search for what he interpreted to be “private sponsors,” outside of the UNHCR resettlement program, was in the contrary jeopardizing his resettlement procedure. Indeed resettlement agents questioned Ben S. vulnerability, since he appeared to be well connected with wealthy individuals who might offer him protection (Ikanda, 2018, Ikanda, 2019).

The opacity of the procedure which led Paul to depart to Canada and be hosted by a Canadian family is such that it is only by analyzing interviews I conducted with him in the light of ongoing complementary pathways to Canada that I was able to make the hypothesis that Paul must have benefitted from a blended sponsorship program. Paul himself was simply proud to have “sponsors” and ignored why he, alone among the group of LGBT asylum seekers from country A who departed simultaneously for Canada, was hosted by a guest family.

Aspiring to Private Sponsorship and Resettlement Simultaneously

In the months, in some cases years before they were interviewed by the UNHCR regional office in country B’s capital, LGBT asylum seekers explored all kinds of options promising the opportunity to travel North. Apart from offers of forged visas by smuggler networks which they considered to be too risky, some of my informants came in contact with transnational networks of assistance directed at LGBT individuals in countries criminalizing homosexuality. One of them, the Canada-based NGO Rainbow Railroad (2020), presents itself on its website as “help[ing] LGBT people escape persecution and violence” and “provid[ing] travel to their destination country and immediate, bridging post-travel support on arrival”13. This resembles the definition of resettlement which my informants in country B read on UNHCR’s website. Moreover, this NGO is operating from Canada, the country where most of their acquaintances had been resettled to, and the representatives of RR with whom they exchanged over Skype were white, like the UNHCR resettlement case workers they hoped to obtain an interview with. As such they viewed RR’s assistance as a hopefully faster version of the UNHCR resettlement program. When pledging their cases to RR they did not mention their asylum procedure with UNHCR resettlement prospects, for fear of appearing less vulnerable to the Canadian NGO. Resettlement aspirants did not know that RR worked with private sponsorship schemes which risk postponing if not jeopardizing their chances of resettlement.

LGBT asylum seekers from country A shared a house in the suburbs of country B’s capital with LGBT nationals of country B. The latter could not claim asylum in the country of which they are nationals. However they could benefit from RR’s private sponsorship, as it is not conditioned on a refugee status. These LGBT nationals of country B understood however that their friends from country A preferred the perspective of resettlement through the UNHCR to RR’s assistance. Eager to become legible to UNHCR resettlement as well, LGBT nationals of country B decided to flee to yet another neighboring country (country C), where they heard that the UNHCR had an office and resettled LGBT individuals to the global North. The fact that country C punishes homosexuality by death penalty appeared to them as secondary compared to the hope of qualifying for UNHCR criteria for asylum and resettlement (Broqua et al., 2020).

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Resettlement Agents’ Compartmentalized Treatment of Resettlement and Complementary Pathways

A resettlement case worker in the regional office admitted that it is even difficult for individuals about to relocate to distinguish whether they went through the UNHCR resettlement process or a private sponsorship process:

“Refugees often cannot tell the difference between resettlement process and a non-resettlement process. It is possible they were never under resettlement consideration and only under private sponsorship process … Since everyone is interviewed by the respective embassies, it is not often possible to tell the processes apart. At least from the point of view of refugees” (November 25, 2019)

As this UNHCR agent rightly remarks, for resettlement and complementary pathways from country B to Canada, it is one and the same instance, the Canadian High Commission (CHC), which is in charge of assessing resettlement cases, blended sponsorship cases and private sponsorship cases. The UNHCR assesses cases, prepares and submits lists to the CHC. The CHC uses these lists to select refugees for resettlement or blended sponsorship programs, parallel to assessing candidates to private sponsorship proposed by other actors (Figure 2).

The degree of entrenchment of UNHCR and CHC procedures suggests that their agents share a sense of bureaucratic agency and communicate on common selection criteria but also on their respective responsibility to inform candidates on the advancement of their cases. However, UNHCR resettlement agents I interviewed knew what private and blended sponsorship programs were but were not aware of which were currently run by Canada nor by other states of the Global North. One of my interviewees in the resettlement unit of the UNHCR regional office presented the different complementary pathways in terms of mutual exclusion rather than complementarity:

“The resettlement process and the private sponsorship process do not interact at any stage. If, however a refugee is under consideration for private sponsorship, UNHCR will not consider the resettlement application until the point the private sponsorship is decided. We would in fact ask the applicant (if they are currently in a private sponsorship process] and withdraw their resettlement case. The selection for private sponsorship is dependent on the Canadians based on the parameters that are set by the government” (November 25, 2019).

While the UNHCR resettlement unit works hand in hand with the CHC to prepare case assessments with the highest chances of resettlement, the resettlement agent insists on the one procedure on which both bureaucratic actors’ procedures diverge. Like Thomson remarked for resettlement agents in Nyarugusu camp in Tanzania, my interviewee seems eager to maintain the compartmentalization inherent to the UNHCR as a bureaucratic organization, which eventually “allows bureaucrats to continue to disperse, or even deflect, individual agency by attributing responsibility to another person or department.” (2012, 199). My interviewee and her colleagues of the resettlement unit disregarded other programs than resettlement as falling per se outside of the “humanitarian mission” (Fresia, 2009b) which they view as UNHCR’s raison d’être: “Private sponsorship is not a humanitarian program. It is an immigration program.” (November 25, 2019) she asserted. As such UNHCR agents did not see it as their responsibility to explain the existence of complementary pathways to individuals aspiring to relocate to the Global North. It was not until the stage of the resettlement interview that resettlement aspirants would learn that the private sponsorship program in which they were involved conflicted with UNHCR resettlement. At this stage, their case would be withdrawn from the imminent resettlement pipeline. Resettlement agents might consider the case to be “on hold,” but resettlement aspirants who saw their friends advance in the process while they themselves were not called back considered that the UNHCR had rejected their claims. After such a setback, some moved out of country B’s capital in search of livelihood projects, abandoning private sponsorship and resettlement projects they thought had already failed.

UNHCR’s local partners in charge of orienting asylum seekers at their arrival in country B are usually those who initiate resettlement aspirants to the procedure and would warn for instance about the impossibility to be considered for UNHCR resettlement and private sponsorship simultaneously. As previously explained however, in the case of LGBT asylum seekers in country B, the NGO Africanrésilience and the UNHCR country office were themselves kept in the dark about the former’s resettlement options.

Discussion

Most dedicated literature on resettlement and complementary pathways offers analyzes through the lens of destination states, sponsors or sponsored refugees upon arrival. Knowledge on the implementation of resettlement and complementary pathways in regions of origin is scarce. My research with LGBT asylum seekers aspiring to resettle to the Global North and UNHCR resettlement agents in a large African city provides new elements on the implementation of resettlement and complementary pathways in regions of origin, on relationships between the UNHCR and local partners and on beneficiaries’ perceptions thereof. In this article I presented some findings of my ethnography: a UNHCR regional office in Africa proceeded to the fast-track resettlement of LGBT asylum seekers out of Africa, altering the usual decision-making chain to circumvent their national partners, for fear that the latter’s presumed homophobia would jeopardize the program’s success. Firstly I analyzed UNHCR resettlement agents’ justifications and their local partners' reactions to their exclusion from the resettlement decision-making chain. Following scholars who theorized the opacity of resettlement selection criteria (Ikanda, 2018; Sandvik, 2011; Thomson, 2012), I argue that the LGBT resettlement process took place behind a veil of secrecy. UNHCR international staff forms an “epistemic community” around their belief on their agency’s moral authority (Fresia, 2009b) and the legitimacy of their soft-law instruments (Sandvik, 2011). Like most expatriate humanitarians, they link their expertise to their upbringing and training in regions of the Global North (Dauvin et al., 2002; Le Renard, 2019), and thus consider their local partners in the Global South as per se outside of their epistemic community. UNHCR international staff’s dissimulation is an “informal normativity” they deemed necessary for the urgent resettlement of LGBT Africans, thereby upholding “the ideals that underpin the transnational resettlement framework” (ibid, 20). Excluding local partners from the decision-making chain for fear that their norms on gender and sexuality conflicts with resettlement states’ resettlement priorities is an extreme form of disciplining local actors’ assessment practices, studied for example by Welfens and Bonjour with family norms in mind.

I build on Thomson’s piece on resettlement procedures as “black boxes of bureaucracy” to come to the conclusion that UNHCR resettlement agents have a fragmented comprehension of resettlement and complementary pathways and their complementarity. They compartmentalize their decision-making power into specific bureaucratic tasks which they consider to be transparent because documented and traceable by other colleagues within the regional office. UNHCR agents see the resettlement of a number of LGBT asylum seekers to the Global North as a success of the resettlement chain stripped of its local actors. They thereby fail to see the damage of a resettlement process without mediation between them and beneficiaries.

Secondly I analyzed beneficiaries’ understanding of resettlement and complementary pathways in the absence of local partners’ mediation. Following scholars who documented refugees’ efforts to qualify for resettlement in regions of origin, I showed that asylum seekers do not wait to be selected for resettlement but actively work on the presentation of their “case” to correspond to selection criteria to the best of their knowledge (Ikanda, 2018, 2019; Thomson, 2018). My findings confirm analyses by Sandvik. (2011) and by Thomson (2012, 2018): candidates know that they owe the success or failure of their resettlement plans to specific agents’ interpretation of selection guidelines and do not hesitate to make life-changing decision based on this observation. I complement these analyses by focusing on those I call street-level humanitarians: local partners who, as mediators between the UNHCR and resettlement candidates, can greatly influence the latter’s interpretation of selection processes. I argue that LGBT aspirants to resettlement share experiences and rumors on the selection process and capitalize on this scarce information to choose their routes to the Global North (resettlement, private sponsorship, tourism visa etc.) and the relevant actors to approach. In the African city of the case study, LGBT aspirants to resettlement identified white expatriates as decision-makers in programs with a potentiality of relocation to the Global North. Competition between aspirants increased misunderstandings of different program’s criteria and their incompatibility, leading to extended waiting time in transit in the country of first asylum for some and aborted procedures for others.

In conclusion this article argues that deliberate or not, the opacity inherent to the bureaucracy of the resettlement selection process initiates refugee’s confusion and actions which, in many cases, work to their detriment.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data, following anonymization, supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

AM collected the data on which the analysis in this submission is based and wrote the manuscript as a single author.

Funding

The research on which this article is based has been funded by the Max Planck Society.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The material on which this paper is based was collected during a one-year long fieldwork in 2017-2018 in several African countries. I am grateful to my informants (refugees and asylum agents) for their time and generosity. Fieldwork was financed by the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology within the framework of a PhD project supported by the research group Integration and Conflict along the Upper Guinea Coast. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the ARAPs Workshop of the Netzwerk Fluchtforschung in November 2019.

Footnotes

1Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, Upper Guinea Coast Research Group, Halle, Germany–Centre Maurice Halbwachs, Paris, France.

3The countries of origin (country A) and of first asylum (country B) are anonymized here in order not to risk jeopardizing their asylum procedures.

4I hereafter use “LGBT” to reflect the appellation through which they become legible in the asylum system.

5See European Commission European Agenda on Migration (2020)https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_18_1763.

6I call them candidates even though they cannot formally “apply” for resettlement as they are identified and then selected by the UNHCR or partners in regions of origin.

7Name changed.

8Based on oral history as well as uncomplete written files archived by UNHCR’s partner NGO, I appreciate the number of resettled LGBT refugees who departed from country B from 2015 to 2018 to be around 100 persons.

9My interviewees at the UNHCR regional office all showed a great dedication to the LGBT resettlement programme. I would like to emphasize that I do not intend to undermine their efforts with my analysis but rather to uncover adverse effects of their implementation practices.

10A process also recounted for the UNHCR Mauritania in (Fresia and Von Känel, 2016).

11Often used by white individuals who live in the Global South and refuse the appellation of “migrants.”

12This search for “sponsors” is better understandable when put in parallel with similar practices by young women and young homosexual men in urban Africa who have recourse to—often romantic and/or sexual—sponsors to sustain their needs. These sponsors are well-off, older, in some cases men from the Global North who act like sugar daddies for their protégés (Fouquet, 2011; Foley and Drame, 2013).

13(Rainbow Railroad–What We Do).

References

Broqua, C., Laborde-Balen, G., Menetrier, A., and Bangoura, D. (2020). Queer Necropolitics of Asylum: Senegalese Refugees Facing HIV in Mauritania. Glob. Public Health 16, 746–762. doi:10.1080/17441692.2020.1851744

Cellini, A. (2018). Annex. Refugee Resettlement: Power Polit. Humanitarian Governance 38, 253–305. doi:10.2307/j.ctvw04brz.16

Dauvin, P., and Siméant, J. (2002). Le travail humanitaire: les acteurs des ONG du siège au terrain. Paris: Presses de sciences po.

Espinoza, M. A. V. (2018). The Politics of Resettlement:. Refugee Resettlement: Power Polit. Humanitarian Governance, 223–243. doi:10.2307/j.ctvw04brz.14

European Commission European Agenda on Migration (2020). European Commission European Agenda on Migration: Continuous Efforts Needed to Sustain Progress. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_18_1763. (Accessed July 20, 2020).

Foley, E. E., and Drame, F. M. (2013). Mbaraanand the Shifting Political Economy of Sex in Urban Senegal. Cult. Health Sex. 15, 121–134. doi:10.1080/13691058.2012.744849

Fouquet, T. (2011). Filles de la nuit, aventurières de la cité: arts de la citadinité et désirs de l’Ailleurs à Dakar. Paris, France: EHESS

Fresia, M. (2009a). Les Mauritaniens réfugiés au Sénégal: une anthropologie critique de l’asile et de l’aide humanitaire. Paris, France: L'Harmattan.

Fresia, M. (2009b). Une élite transnationale : la fabrique d'une identité professionnelle chez les fonctionnaires du Haut Commissariat des Nations Unies aux Réfugiés. remi 25, 167–190. doi:10.4000/remi.4999

Fresia, M., and von Känel, A. (2016, Universalizing the Refugee Category and Struggling for Accountability: the Everyday Work of Eligibility Officers within UNHCR). In UNHCR and the Struggle for Accountability. (London, United Kingdom: Routledge), 101–118.doi:10.4324/9781315692593-6

Garnier, A., Jubilut, L. L., and Sandvik, K. B. (2018). Refugee Resettlement: Power, Politics, and Humanitarian Governance. New York, NY: Berghahn Books.

Garnier, A. (2016). “Narratives of Accountability in UNHCR's Refugee Resettlement Strategy,” in UNHCR and the Struggle for Accountability. (London, United Kingdom: Routledge), 64–80. doi:10.4324/9781315692593-4

Hashimoto, N. (2018). Refugee Resettlement as an Alternative to Asylum. Refugee Surv. Q. 37, 162–186. doi:10.1093/rsq/hdy004

Ikanda, F. N. (2018). Animating ‘refugeeness' through Vulnerabilities: Worthiness of Long-Term Exile in Resettlement Claims Among Somali Refugees in Kenya. Africa 88, 579–596. doi:10.1017/s0001972018000232

Ikanda, F. (2019). What Makes a Refugee Vulnerable? SAPIENS, Available at: https://www.sapiens.org/culture/somali-refugees/ (Accessed December 12, 2018).

Jacobsen, K., and Landau, L. B. (2003). The Dual Imperative in Refugee Research: Some Methodological and Ethical Considerations in Social Science Research on Forced Migration. Disasters 27, 185–206. doi:10.1111/1467-7717.00228

Koçak, M. (2020). Who Is “Queerer” and Deserves Resettlement?: Queer Asylum Seekers and Their Deservingness of Refugee Status in Turkey. Middle East Critique 29, 29–46. doi:10.1080/19436149.2020.1704506

Krause, U. (2017). Researching Forced Migration: Critical Reflections on Research Ethics during Fieldwork. RSC Working Paper Series. Available at: https://www.rsc.ox.ac.uk/publications/researching-forced-migration-critical-reflections-on-research-ethics-during-fieldwork. (Accessed January 13, 2020).

Le Renard, A. (2019). Le Privilège Occidental. Travail, intimité et hiérarchies postcoloniales à Dubaï. Les Presses de Sciences Po. Available at: http://journals.openedition.org/sociologie/6376 (Accessed November 1, 2019).

Menetrier, A. (Forthcoming). “An Ethical Dilemma: When Research Becomes ‘expert Testimony,’” in eds. B. Camminga, and J. Marnell (London, United Kingdom: Zed Books).

Menetrier, A. (2019). Déchiffrer les stéréotypes de genre des guichets de l’asile par les réseaux sociaux, in Hermès Stéréotypes, représentations et idéologies. Paris, France: CNRS éditions.

Menetrier, A. (2017). “‘It’s a War against Our Own Body’: Long-Term Refugee Women React to the Withdrawal of Relief Organisations in Dakar, Senegal,” in Witnessing The Transition: Moments in the Long Summer of Migration. Editors G. Yurdakul, R. Römhild, A. Schwanhäußer, and B. Zur Nieden (Berlin: Berlin Institute for empirical Integration and Migration Research (BIM), 77–94.

Rainbow Railroad (2020). What We Do. Available at: https://www.rainbowrailroad.org/whatwedo. (Accessed July 20, 2020).

Saleh, F. (2020). “Resettlement as Securitization: War, Humanitarianism, and the Production of Syrian LGBT Refugees,” in Queer and Trans Migrations: Dynamics of Illegalization, Detention, and Deportation. Editor K. R. chávez.

Sandvik, K. B. (2011). Blurring Boundaries: Refugee Resettlement in Kampala-Between the Formal, the Informal, and the Illegal. PoLAR: Polit. Leg. Anthropol. Rev. 34, 11–32. doi:10.1111/j.1555-2934.2011.01136.x

Thomson, M. J. (2018). “Giving Cases Weight”: in Refugee Resettlement: Power, Politics and Humanitarian Governance. Editors A. Garnier, L. Lyra Jubilut, and K. Bergtora Sandvik, 203–222. doi:10.2307/j.ctvw04brz.13

Thomson, M. J. (2012). Black Boxes of Bureaucracy: Transparency and Opacity in the Resettlement Process of Congolese Refugees. PoLAR: Polit. Leg. Anthropol. Rev. 35, 186–205. doi:10.1111/j.1555-2934.2012.01198.x

UNHCR (2011). UNHCR Resettlement Handbook (Complete Publication). Geneva: UNHCR. Available at: https://www.unhcr.org/46f7c0ee2.pdf.

Keywords: resettlement, Africa, LGBT, united nations high commissioner for refugees, secrecy

Citation: Menetrier A (2021) Implementing and Interpreting Refugee Resettlement Through a Veil of Secrecy: A Case of LGBT Resettlement From Africa. Front. Hum. Dyn 3:594214. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2021.594214

Received: 12 August 2020; Accepted: 12 August 2021;

Published: 09 September 2021.

Edited by:

Adele Garnier, Laval University, CanadaReviewed by:

Saskia Bonjour, University of Amsterdam, The NetherlandsMarnie Thomson, Fort Lewis College, United States

Copyright © 2021 Menetrier. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Agathe Menetrier, bWVuZXRyaWVyLmFnYXRoZUBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Agathe Menetrier

Agathe Menetrier