95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

HYPOTHESIS AND THEORY article

Front. Hum. Dyn. , 08 April 2021

Sec. Dynamics of Migration and (Im)Mobility

Volume 2 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fhumd.2020.599222

This article is part of the Research Topic Migration in the Time of COVID-19: Comparative Law and Policy Responses View all 18 articles

COVID-19 has spread quickly through immigration detention facilities in the United States. As of December 2, 2020, there have been over 7,500 confirmed COVID-19 cases among detained noncitizens. This Article examines why COVID-19 spread rapidly in immigration detention facilities, how it has transformed detention and deportation proceedings, and what can be done to improve the situation for detained noncitizens. Part I identifies key factors that contributed to the rapid spread of COVID-19 in immigration detention. While these factors are not an exhaustive list, they highlight important weaknesses in the immigration detention system. Part II then examines how the pandemic changed the size of the population in detention, the length of detention, and the nature of removal proceedings. In Part III, the Article offers recommendations for mitigating the impact of COVID-19 on detained noncitizens. These recommendations include using more alternatives to detention, curtailing transfers between detention facilities, establishing a better tracking system for medically vulnerable detainees, prioritizing bond hearings and habeas petitions, and including immigration detainees among the groups to be offered COVID-19 vaccine in the initial phase of the vaccination program. The lessons learned from the spread of COVID-19 in immigration detention will hopefully lead to a better response to any future pandemics. In discussing these issues, the Article draws on national data from January 2019 through November 2020 published by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and Customs and Border Protection (CBP), two agencies within DHS. The main datasets used are detention statistics published by ICE for FY 2019 (Oct. 2018-Sep. 2019), FY 2020 (Oct. 2019-Sep. 2020), and the first two months of FY 2021 (Oct. 2020-Nov. 2020). These datasets include detention statistics about individuals arrested by ICE in the interior of the country, as well as by CBP at or near the border. Additionally, the Article draws on separate data published by CBP regarding the total number of apprehensions at the border based on its immigration authority under Title 8 of the United States Code, as well as the number of expulsions at the border based on its public health authority under Title 42 of the United States Code.

COVID-19 has spread quickly through immigration detention facilities in the United States. As of December 2, 2020, there have been over 7,500 confirmed COVID-19 cases among detained noncitizens (Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2020a). The purpose of immigration detention is supposed to be to secure attendance at immigration court hearings and ensure the safety of the community. In reality, however, widespread detention is used as a way to deter asylum seekers and other migrants from coming to the United States (Ryo, 2019a). Although the United States immigration detention system is considered civil, it is embedded in the criminal justice system and virtually indistinguishable from criminal punishment (Stumpf, 2006; García Hernández, 2014; Ryo, 2019b). Like prisoners, immigration detainees live in crowded conditions, often with poor hygiene and inadequate ventilation, making them especially vulnerable to contagious diseases (Meyer et al., 2020).

The high rate of turnover in the detained population contributes to the risk of infection (Solis et al., 2020). In FY 2020, the average daily population in United States immigration detention was 34,427, but the total number of people booked into immigration detention was 177,391 (Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2020b). Frequent transfers of noncitizens between detention facilities further compounds the risk of transmission (Human Rights Watch, 2011; Ryo and Peacock, 2018). In fact, in August 2019, when the Centers for disease Control (“CDC”) addressed outbreaks of the mumps in fifteen immigration detention centers across seven states, the agency specifically noted concerns about “new introductions [of mumps cases] into detention facilities through detainees who are transferred or exposed before being taken into custody” (Leung et al., 2019).

Making matters worse, the immigration detention system is plagued by “substandard and dangerous medical practices,” including “overreliance on unqualified medical staff, delays in emergency care, and requests for care unreasonably delayed” (Human Rights Watch, 2017). Problems with medical care in immigration detention have been documented for decades, and the months leading up to the COVID-19 pandemic were no exception. In June 2019, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Office of the Inspector General found “egregious violations” of ICE’s own detention standards, including poor hygiene and inadequate medical care (Department of Homeland Security, Office of the Inspector General, 2019). Congress opened an investigation into the medical care in immigration detention facilities in December 2019, just a month before the first confirmed coronavirus cases in the United States (Aleaziz, 2019).

These conditions alone have made it difficult for DHS to protect the health of noncitizens in custody. But DHS’s slow response after the World Health Organization (WHO) announced a global pandemic in March 2020 exacerbated the situation. This Article examines why COVID-19 spread rapidly in immigration detention facilities, how it has transformed detention and deportation proceedings, and what can be done to improve the situation for detained noncitizens.

In discussing these issues, the Article draws on national data from January 2019 through November 2020 published by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and Customs and Border Protection (CBP), two agencies within DHS. The main datasets used are detention statistics published by ICE for FY 2019 (Oct. 2018-Sep. 2019), FY 2020 (Oct. 2019-Sep. 2020), and the first two months of FY 2021 (Oct. 2020-Nov. 2020). These datasets include detention statistics about individuals arrested by ICE in the interior of the country, as well as by CBP at or near the border. Additionally, the Article draws on completely separate data published by CBP regarding the total number of apprehensions at the border based on its immigration authority under Title 8 of the United States Code, as well as the total number of expulsions at the border based on its public health authority under Title 42 of the United States Code. Some, but not all, of the individuals apprehended by CBP are transferred to ICE custody and detained. For example, unaccompanied minors apprehended by CBP are never transferred to ICE custody. Instead, they are transferred to the custody of the Office of Refugee Resettlement within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, which operates shelters that are not considered detention.

Part I identifies key factors that contributed to the rapid spread of COVID-19 in immigration detention. While these factors are not an exhaustive list, they highlight important weaknesses in the immigration detention system. Part II then examines how the pandemic changed the size of the population in detention, the length of detention, and the nature of removal proceedings. In Part III, the Article offers recommendations for mitigating the impact of COVID-19 on detained noncitizens. These recommendations include using more alternatives to detention, curtailing transfers between detention facilities, establishing a better tracking system for medically vulnerable detainees, prioritizing bond hearings and habeas petitions, and including immigration detainees among the groups to be offered COVID-19 vaccine in the initial phase of the vaccination program. The lessons learned from the spread of COVID-19 in immigration detention will hopefully lead to a better response to any future pandemics.

Several factors have contributed to the rapid spread of COVID-19 in immigration detention. First, ICE delayed testing detained noncitizens for COVID-19. Second, ICE delayed issuing COVID-19 guidance to all immigration detention facilities and made important infection prevention and control measures discretionary rather than mandatory. In particular, too much discretion has been permitted regarding quarantine methods and transfers of detainees between facilities. Third, ICE lacked a system for tracking medically vulnerable detainees at risk for serious illness from COVID-19. Each of these factors is discussed below.

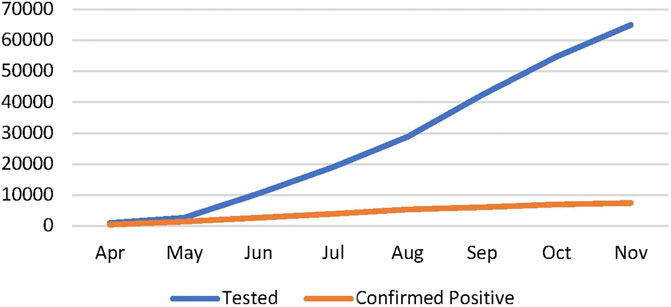

There were significant delays in testing detained noncitizens for COVID-19 that allowed infections to spread rapidly at the beginning of the pandemic. While ICE has not shared information about when it began testing for COVID-19, it began reporting data on COVID-19 testing on its website on April 28, 2020, well into the pandemic. On that day, it reported that only 705 detainees had been tested, of whom 425 were confirmed positive. By the end of May 2020, only 2781 detainees had been tested, of whom 1406 were positive. The extremely high positive rate of 50.5% in the month of May underscored the need for more widespread testing. Over the next several months, ICE began testing around 10,000 detainees each month. By December 2, 2020, ICE had tested 67,660 detainees, of whom 7,567 (11.2%) were confirmed positive. Figure 1 shows how COVID-19 testing of detainees progressed between April and November 2000.

FIGURE 1. COVID-19 Testing of Immigration Detainees, April-November 2020. Source: COVID-19 ICE Detainee Statistics, available at “https://www.ice.gov/coronavirus” and archived versions of that webpage.

Another major factor contributing to the spread of COVID-19 in detention was delayed and discretionary guidance from ICE. ICE did not issue COVID-19 Pandemic Response Requirements (“PRR”) that apply to all immigration detention facilities until April 10, 2020, one month into the pandemic (Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2020f). Before April 10, 2020, ICE issued various memoranda that provided only piecemeal instructions and did not apply to all detention facilities.

The ICE Health Service Corps (IHSC) first issued guidance on March 6, 2020, informing health care staff of the CDC’s recommendations for testing but leaving it up to staff to use their own discretion in deciding whether someone should be tested (Immigration and Customs Enforcement Health Service Corps, 2020). The IHSC guidance did not stress the importance of social distancing or face masks. A few weeks later, on March 27, 2020, ICE issued a memorandum that set forth an “action plan” with certain measures designed to reduce exposure to COVID-19, such as screening staff and detainees, suspending social visitation, and offering non-contact legal visits (Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2020c). However, this action plan applied only to “ICE-dedicated facilities,” meaning facilities that hold exclusively immigration detainees. With respect to the 172 “non-dedicated facilities,” which hold federal or state criminal detainees as well as civil immigration detainees, ICE deferred to local, state, and federal public health authorities.

Shortly thereafter, on April 4, 2020, ICE issued updated guidance titled “Detained Docked Review,” asking Field Office Directors to “please” review the custody of individuals who have a “significant discretionary factor weighing in favor of release” (Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2020d). This language did not require compliance. The guidance also stressed that noncitizens who pose a potential danger to persons or property should not be released as a matter of discretion, giving Field Office Directors wide latitude to deem someone a potential danger and keep them detained.

ICE finally set forth certain mandatory requirements for all facilities holding immigration detainees on April 10, 2020, when it issued the first version of the PRR (Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2020f). Among other things, the PRR directed all facilities to require staff and detainees to wear cloth face coverings when PPE is limited and to provide unlimited supplies of liquid soap for handwashing. However, the PRR, like prior guidance, was replete with discretionary language.

For example, the PRR stated that “efforts should be made” to reduce the population to approximately 75% of capacity, instead of requiring ICE to reduce the detained population. With respect to social distancing, the PRR simply noted that “strict social distancing may not be possible” and suggested that certain measures be adopted “to the extent practicable” (Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2020f). Regarding new entrants to a facility, ICE advised making “considerable effort” to quarantine them for 14 days before they enter the general population (Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2020f). For symptomatic detainees, the PRR stated that “ideally” they should not be isolated with other individuals (Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2020f). This discretionary language enabled detention centers to avoid adopting crucial measures for preventing the spread of COVID-19.

The PRR has been revised multiple times during the course of the pandemic, generally in response to updated guidance from CDC or federal court orders requiring ICE to make certain changes. At the time of this writing, the most recent version of the PRR is the fifth version that was published on October 27, 2020. Two especially important areas where discretionary measure remain a concern involve quarantining cohorts of detainees and transfers between facilities.

“Cohorting” refers to isolating a group of potentially exposed individuals together. According to the CDC, every possible effort should be made to individually quarantine potentially exposed people. The CDC explains that “cohorting individuals with suspected COVID-19 is not recommended due to the high risk of transmission from infected to uninfected individuals” (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). Thus, “cohorting should only be practiced if there are no other available options.” ICE, however, has relied primarily on cohorting potentially exposed individuals (Schriro, 2020). Entire dorms, which may include 50 or more people, are typically placed in isolation as a cohort when there is suspected exposure. The PRR simply instructs detention facility operators to “review” the CDC’s preferred methods of isolation and allows decisions to be made “depending on the space available in a particular facility.” Additionally, the CDC recommends that when it is not possible to place individuals who are quarantined in single cells, each person in the cohort should be assigned at least 6 feet of personal space in all directions (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). Such social distancing simply is not possible in a detention facility.

The CDC recommends against transferring detained individuals between facilities unless absolutely necessary. Yet, throughout the pandemic, ICE has continued to transfer detained noncitizens all over the nation. Such transfers have led to known outbreaks of COVID-19 in numerous states, including Texas, Ohio, Florida, Mississippi, and Louisiana (Seville and Rappleye, 2020). For instance, on April 11, 2020, ICE transferred around 70 people from facilities in Philadelphia and New Jersey with known outbreaks of COVID-19 to the Prairieland Detention Center in Alvarado, Texas, resulting in an outbreak there (Solis, 2020). Furthermore, at least 200 people were transferred to the Bluebonnet Detention Center in Texas between mid-March 2020 and the end of May 2020 (Seville and Rappleye, 2020). By early April 2020, there was an outbreak in Bluebonnet that grew to 300 confirmed cases (Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2020b).

In a particularly egregious incident, ICE flew detainees to Virginia simply to transport its own agents to Washington DC to help suppress Black Lives Matter protests (Olivo and Miroff, 2020). That transfer resulted in an outbreak of 300 COVID-19 cases in the Farmville Detention Center, resulting in one death. While the fifth version of the PRR attempts to limit transfers, the number of exceptions still makes it ineffective, as discussed further in Part III below.

A third factor that contributed to the spread of COVID-19, recognized by the April 20, 2020, court order in Fraihat v. United States. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, is that no system existed for identifying and tracking medically vulnerable detainees (Fraihat, 2020). ICE uses a tool called a Risk Classification Assessment (RCA) that generates recommendations about detention or release for individuals who are not subject to mandatory detention. The RCA includes a “checklist” for “special vulnerabilities,” but this checklist provides only minimal information. It includes only four categories that can be marked: “serious physical illness,” “elderly,” “disabled,” and “pregnant.” These limited categories failed to provide enough information to identify individuals at high risk of severe illness due to COVID-19. The absence of a centralized tracking mechanism for high risk individuals resulted in insufficient medical and preventive monitoring.

The spread of COVID-19 in immigration detention has had an enormous impact on detention. Both the number of people in detention and the average length of detention have changed as a result of the pandemic. Additionally, detained removal proceedings have been adversely impacted, especially access to counsel.

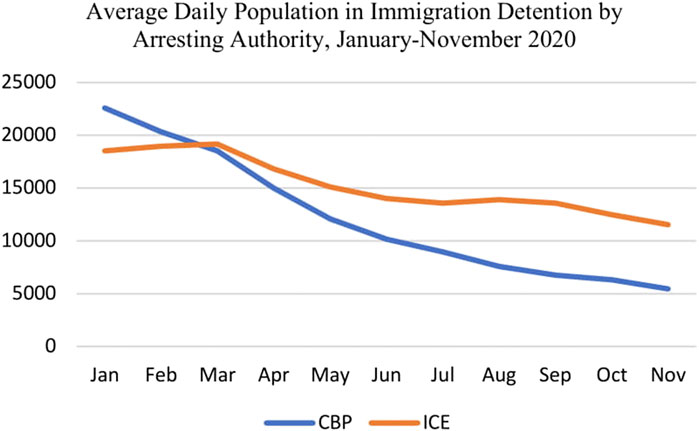

Since the pandemic began, the average daily detained population has been reduced by more than half. In February 2020, before the WHO declared a pandemic, the average daily detained population was 39,314 (Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2020b). By November 2020, it was down to 16,894 (Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2020e). The total drop in detention can be attributed to both fewer arrests by ICE, which operates in the interior of the country, and fewer arrests by CBP, which operates at the nation’s borders. However, the drop in detention due to fewer arrests by CBP has been much more pronounced, as shown in Figure 2 (Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2020b; Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2020e).

FIGURE 2. Average daily population in immigration detention by arresting authority, January-November 2020. Source: Ice detention data, FY20 YTD; ice detention data, FY 21 YTD.

In March 2020, ICE announced that it would make only “mission critical” arrests necessary to “maintain public safety and national security” (Kullgren, 2020; Sacchetti and Hernández, 2020). The average daily detained population attributed to arrests by ICE dropped from 18,981 in February 2020 to 11,534 by November 2020 (Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2020e). By comparison, the average daily detained population attributed to arrests by CBP fell from 20,332 in February 2020 to just 5,451 by November 2020 (Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2020b; Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2020e).

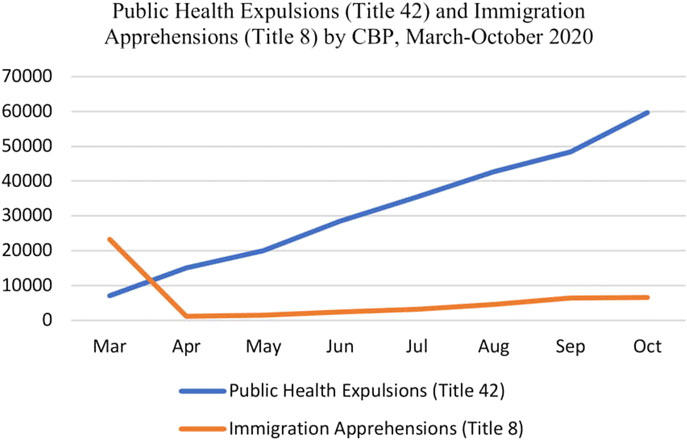

The more dramatic drop in detention by CBP is related to CBP’s use of Title 42 of the United States Code, a public health law, to expel migrants, including asylum seekers, at the southwest border on public health grounds, rather than allowing them to apply for asylum in the United States. On March 21, 2020, President Trump determined that it was necessary to prevent undocumented migrants from entering the United States in the interest of public health and prohibited their entry under Title 42. That month, CBP expelled 7,075 migrants at the southwest border (U.S. Customs and Border Protection, 2020a). The number of expulsions has continued to increase exponentially each month, exceeding 59,000 at the southwest border by October 2020 (U.S. Customs and Border Protection, 2020b).

As expulsions under Title 42 have increased, the number of individuals apprehended by CBP under Title 8 has plummeted (Figure 3). Title 8 pertains to immigration proceedings and protects the right to apply for asylum. The drop in credible fear interviews conducted by asylum officers for individuals apprehended at or near the border further confirms that asylum seekers are among those being expelled at the border. Credible fear interviews provide a threshold screening for asylum, and those who pass the interview are allowed to apply for asylum in immigration court. The number of credible fear cases received by USCIS dropped from 4,631 in February 2020 to 709 in October 2020 (U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, 2020).

FIGURE 3. Public health expulsions and immigration apprehensions by CBP, March to October 2020. Sources: CBP, nationwide enforcement encounters: Title 8.

A small percentage of the reduction in the detained population can also be attributed to the release of children detained in “family residential centers” (FRCs), which are detention centers that hold children together with their parents. Based on a nationwide restraining order issued by a federal judge in Flores v. Barr in March 2020, ICE was required to release children detained in FRCs (Flores, 2020). The average daily detained population in FRCs dropped from 1,591 in March 2020 to 766 in April 2020 and continued to decline in the following months (Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2020b). By November 2020, the average daily detained population in FRCs was 235 (Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2020e). The parents of the children, however, were not ordered released, and therefore had to decide whether to be separated from their children or remain together with their children in detention (Alvarez and Sands, 2020).

While the size of the detained population has decreased during the pandemic, the length of detention has increased. In March 2020, the average length of stay in immigration detention was 51 days (Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2020b). By November 2020, that number had increased to 88 days (Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2020e). For individuals arrested by CBP, generally asylum seekers who asked for asylum at a port of entry or who were apprehended near the border after entering unlawfully, the average length in detention increased from 54 days in March to 137 days in November (Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2020b; Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2020e). This could be due to delays in conducting credible fears interviews or in delays conducting immigration court hearings to review credible fear denials.

Additionally, the increase in the average length of detention may be due to court closures or delayed bond hearings. There may also be more requests for continuances related to the pandemic. Noncitizens may need more time to find an attorney, and attorneys may need more time to prepare cases when they cannot meet with clients in person. In cases where the noncitizen already has final order of removal, detention may be prolonged by border closures, lack of commercial flights, and fewer charter flights to effectuate a deportation or voluntary departure.

The pandemic has also had a significant impact on removal proceedings. Non-detained hearings in immigration court have been indefinitely postponed. Cases subject to the Migrant Protection Protocols (“MPP”) have also been indefinitely postponed, even though those cases are categorized as detained under 8 U.S.C. § 1,225(b) (2). Asylum seekers placed in MPP are forced to remain in Mexico during their removal proceedings and must present themselves at designated ports of entry to be transported by ICE to their court hearings (Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2019a). Consequently, they are effectively trapped in dangerous areas and squalid camps along the border. Even though they are not in a detention center, the regulation at 8 C.F.R. § 235.3(d) states that they are “considered detained,” and immigration courts normally place MPP cases on the detained docket. Nevertheless, MPP cases remain suspended during the pandemic, prolonging and exacerbating the risk of harm these asylum seekers face while forced to remain in Mexico.

With the exception of MPP cases, immigration courts have proceeded with the detained docket during the pandemic. In order to reduce the need for personal appearances, immigration courts have liberally allowed telephonic appearances by counsel for master hearings, which are brief, status hearings. However, in-person appearances remain the norm for merits hearings, which are similar to trials. As a result, immigration judges, court personnel, attorneys on both sides, and detained immigrants face a risk of being infected by COVID-19 in court. This risk is real, as evidenced by numerous court closures due to COVID-19 exposure. But postponing detained cases due to the pandemic would further prolong detention and potentially raise due process concerns.

In moving forward with detained cases, both detained individuals and representatives have faced numerous challenges. For detained individuals, it is harder to find a representative and to communicate with an existing representative. Representatives have also dealt with confusing and changing directives about how to communicate with clients during the course of the pandemic. At the very beginning of the pandemic, guidance on ICE’s website instructed legal representatives to bring their own PPE to detention centers to have contact visits. That guidance was later changed to say that representatives are required to undergo “the same screening required for staff,” without specifying what that screening involves. As COVID-19 spread, it became increasingly dangerous for representatives to visit in person even if they brought their own PPE. Attorneys were forced to balance their professional responsibility of zealous representation with serious threats to their personal health. Ultimately, most representatives began to rely exclusively on phone calls to continue representing detained clients.

However, legal calls have also been challenging. Many detention centers do not have an adequate number of phones dedicated to legal calls. Detained individuals may therefore be forced to call their counsel from non-legal phone lines, which deprive them of private and confidential communications. While some detention centers make video conference calls available to detainees, those also can be monitored. Additionally, in some detention centers, individuals who are quarantined have been cut off completely from access to the legal phones, leaving them no choice but to make calls on monitored lines. Making matters worse, there are often tight time limits on calls and detainees may not be able to pay for them.

For counsel, being limited to telephonic communications with a client can greatly impede the representation. It is difficult to establish trust and properly prepare a client to testify telephonically. Assessing the client’s demeanor and reviewing evidence are also nearly impossible over the phone. From a detained individual’s perspective, it is much harder to engage with the legal process when interactions occur remotely rather than in-person, which can lead to giving up the case instead of fighting to remain in the country (Eagly, 2015). Detained individuals also lose the ability to confer with counsel before, during, and after a hearing, further limiting access to counsel. Consequently, protecting access to counsel, which is crucial to fundamental due process, remains one of the most challenges issues during the pandemic.

In light of the problems discussed above, urgent reforms are needed. This section makes several recommendations to improve the plight of detained noncitizens. First and foremost, release is the best way to protect both public health and legal rights. There are various ways that ICE can release noncitizens to minimize any concerns about flight risk. Second, transfers between facilities should be stopped, or at least sharply curtailed and better regulated. Third, ICE should create a long-term system for tracking medically vulnerable detainees. Fourth, courts should prioritize bond hearings and habeas petitions challenging detention. Finally, detained noncitizens should be prioritized for COVID-19 vaccination.

Releasing noncitizens from detention is the best way to address the risk of transmission in detention, concerns with medical care in detention, and the impact of detention on removal proceedings (Meyer et al., 2020; Solis et al., 2020). A poll by the University of Colorado Immigration Clinic found that a majority of the population supports releasing noncitizens from detention during the pandemic (Chapin, 2020). Releasing noncitizens not only lowers the risk of infection by reducing the detained population, but it also addresses some of the problems that ICE is currently addressing through dangerous transfers. For example, instead of transferring noncitizens for medical evaluation or clinical care, they could be released for medical care in the community; and instead of transferring noncitizens to “prevent overcrowding,” that issue can be resolved by releasing more people from detention.

One positive change during the past year is that ICE has increased its use of “parole” under 8 C.F.R. § 212(d) (5) as a way to release someone from detention for humanitarian reasons. In FY 2019, 17,798 noncitizens were released on parole out of a total of 263,263 noncitizens released from detention (6.8%), while in FY 2020, 11,140 noncitizens were released on parole out of 60,625 released from detention (18.4%) (Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2019b; Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2020b). But the parole authority could be used much more liberally to reduce the detained population. In particular, noncitizens who have lawfully asked for asylum at a port of entry are generally detained as “arriving aliens,” but ICE can decide to release them through parole. Releasing all asylum seekers would uphold the right to seek asylum while also protecting public health.

ICE could also release more noncitizens on their own recognizance, under an order of supervision, or on bond. In FY 2020, a much smaller percent of noncitizens were released from detention on their own recognizance compared to FY 2019 (23% compared to 67%), while a higher percentage of noncitizens were released under an order of supervision in FY 2020 compared to FY 2019 (10.6% compared to 5.2%). One might expect ICE to be more willing to set bonds during the pandemic, but the percent of people released from detention based on a bond set by ICE did not change in FY 2020 compared to FY 2019 (7.6% compared to 7.5%). More frequent use of these alternatives would help keep detention as a last resort.

The total number of people enrolled in ICE’s electronic monitoring programs also did not increase much in FY 2020 compared to FY 2019 (85,857 compared 83,186) (Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2019b; Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2020b). Electronic monitoring programs involve either an ankle bracelet with GPS monitoring, telephonic check-ins with voice recognition software, or a smartphone app called SMARTLink that uses a photo check-in. If flight risk is the main issue, then bond and electronic monitoring are both preferable alternatives to detention that address that concern.

Community-based alternatives to detention that rely on case management are an even better option (Marouf, 2017). These community-based alternatives were being piloted during the Obama Administration. The basic idea is to provide a case manager’s support with legal, medical, and other needs in order to help noncitizens effectively navigate their removal proceedings and comply with court orders. Reducing detention long-term is not only the most humane option, but it will also save enormous costs while protecting public health. As Solis et al. have concluded, simply “implementing CDC recommendations to mitigate COVID-19 transmission in carceral settings has been insufficient to lessen outbreak progression” (Solis et al., 2020).

Abolishing detention is ideal, but at a minimum transfers should be sharply curtailed and better regulated. Although the fifth version of the PRR attempts to limit transfers, the exceptions swallow the general rule (Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2020g). The PRR states that transfers “are discontinued unless necessary for medical evaluation, medical isolation/quarantine, clinical care, extenuating security concerns, release or removal, or to prevent overcrowding” (Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2020g). Because “security concerns” are not defined, this particular exception could be invoked for unspecified reasons. Additionally, the PRR allows “transfers for any other reason,” as long as there is “justification and pre-approval from the local [ICE] Field Office Director” (Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2020g). The PRR does not explain what qualifies as a justification. This loophole gives broad discretion to ICE Field Office Directors to approve transfers. Consequently, transfers are continuing on a large scale, both within states and between states.

Stopping these transfers, or at least substantially reducing them by reigning in the exceptions, is crucial for curbing the spread of COVID-19. Transfers for “clinical care” and “medical isolation/quarantine” are especially disturbing because the individuals being transferred may already be infected. If a facility cannot provide the medical evaluation or clinical care needed, the appropriate response during a pandemic would be to take the individual to an outside medical provider or release the individual, rather than transferring the individual to another detention facility. Release is also a much better solution than transfers to prevent overcrowding. Allowing transfers to “prevent overcrowding” effectively permits pre-pandemic practices to continue, since ICE has typically made decisions about transfers based on bed space (Ryo and Peacock, 2018).

Apart from the public health reasons for stopping transfers, they should be stopped because of their harmful impact on removal proceedings. As Emily Ryo and Ian Peacock have explained, transfers can “hinder access to legal representation, sever family ties and community support, and separate detainees from the evidence needed in their court proceedings” (Ryo and Peacock, 2018). Human Rights Watch reports that transfers are often made to facilities in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas, “states that collectively have the worst ratio of transferred immigrant detainees to immigration attorneys in the country (510–1) (Human Rights Watch, 2011). Given how the pandemic has already hindered access to representatives, family, and community support, adding transfers to this mix makes representation nearly untenable. Transfers also impede detainees’ ability to challenge their detention through bond hearings and habeas petitions, which is especially problematic during the pandemic (Human Rights Watch, 2011).

Even if transfers cannot be completely stopped, more checks should be imposed on the decisions of ICE officers to transfer detainees. Transfers of state and federal prisoners are currently much better regulated than the transfer of immigration detainees. If ever there was a time to address the need for better regulation of transfers, it is now, during a pandemic.

ICE eventually created a tracking mechanism in response to a preliminary injunction issued by a federal court in a case called Fraihat. The fifth version of the PRR explains that two categories of detained individuals must be tracked based on the Fraihat class action (Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2020g). One category is for detained individuals who are pregnant or aged 55 and older. This category is called “Subclass One” and assigned the alert code “RF1.” The second category is for detained individuals with certain medical conditions, who are called “Subclass Two” and assigned the alert code “RF2.”

This new tracking system promotes compliance with the court’s orders in Fraihat, but it is specific to the subclasses defined in that litigation. ICE could simply terminate the tracking system if the court no longer required it. A tracking method that is independent of the litigation and captures different types of medical vulnerabilities would be useful to maintain not only for the present pandemic, but long term. It would be useful for any future pandemics as well as to improve medical treatment in detention by providing a way for ICE to assess the medical conditions and needs of the detained population.

Courts also have an important role to play in helping medically vulnerable noncitizens in detention. Immigration Judges should prioritize bond hearings in order to facilitate release from detention. During bond hearings, judges should ensure that the burden of proof is placed on the government to show a need for detention based on flight risk or danger. David Hausman has argued that because detention itself poses a danger to the community, immigration courts actually should not even consider flight risk (Hausman, 2020). Immigration judges should further ensure that they are setting individualized bonds based on ability to pay, instead of blanket bonds, and that they fairly consider all relevant factors. Emily Ryo’s empirical research indicates that bond proceedings often are not fair, as the recency and number of convictions are not predictive of danger determinations, Central Americans are more likely to be deemed dangerous, and pro se individuals fare worse than those with representation even after controlling for criminal history (Ryo, 2019c). For detainees who cannot afford a bond, immigration judges should seriously consider other alternatives to detention. Considering the pandemic a “changed circumstance” that justifies a new bond hearing if bond was previously denied would also help protect public health.

Similarly, federal district courts should prioritize habeas petition by noncitizens seeking release from detention. It is all too common for federal judges to handle habeas petitions without any urgency, even during the pandemic. Instead of giving the government sixty days to respond to a habeas petition and then waiting thirty more days for a reply, courts should set expedited briefing schedules. Once the briefing is completed, courts should promptly schedule a hearing or render a decision. For many detained noncitizens, a habeas petition challenging prolonged detention or the conditions of detention may be the only hope for release.

Finally, while noncitizens remain detained, they should be prioritized for vaccination as a highly vulnerable group. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), a federal advisory committee that develops recommendations on the use of vaccines, has recommended, as interim guidance, that health care personnel and residents of long-term care facilities be offered COVID-19 vaccine in the initial phase of the vaccination program (Dooling et al., 2020). However, the ethical principles that guide decisionmaking about vaccination if supply is limited support prioritizing detained noncitizens as well. These ethical principles include: 1) maximizing benefits and minimizing harms; 2) mitigating health inequities; 3) promoting justice; and 4) promoting transparency.

Vaccinating detained noncitizens helps maximize benefits in several ways. It reduces the risk of large outbreaks in detention facilities; reduces the risk of spreading the disease to surrounding communities as well as to other cities and states through transfers; and reduces the risk of spreading the disease to other countries through deportations. At the same time, vaccinating detainees helps minimize harms, not only to the detainees themselves, but to the population. In fact, Jamie Solis et al. have identified outbreaks in jails, prisons, and immigration detention centers as responsible for the third wave of structural vulnerability related to COVID-19 that began in April 2020 (Solis et al., 2020). As WHO has explained, the transmission of COVID-19 in detention centers amplifies the overall effect of the pandemic (World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, 2020). According to the WHO, “efforts to control COVID-19 in the community are likely to fail if strong infection prevention and control (IPC) measures, adequate testing, treatment and care are not carried out in prisons and other places of detention” (World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, 2020).

Additionally, vaccinating detained noncitizens would help mitigate health inequities in the burden of COVID-19 disease. Factors such as income, access to health care, and race/ethnicity, which contribute to health disparities, are traditionally considered in applying this ethical principle. Most detained noncitizens are black or brown, have little or no income, limited access to health care, and no ability to socially distance in detention. Blacks and Hispanics also have a high prevalence of underlying medical conditions that place them at high risk of progressing to severe COVID-19 and dying (Solis et al., 2020). Prioritizing the vaccination of detained noncitizens would ensure that they are not further disadvantaged.

Third, the principle of promoting justice requires upholding the dignity of all persons and removing barriers to vaccination among marginalized groups. Detained noncitizens have already been stripped of their dignity in numerous ways and are often invisible to society, hidden in detention centers in remote areas. Certain subgroups of detained noncitizens are even less visible and more marginalized because they speak neither English nor Spanish and face medical neglect due to language barriers (Ryo, 2019b). The principle of promoting justice requires intentionally ensuring that all detained noncitizens “have equal opportunity to be vaccinated, both within the groups recommended for initial vaccination, and as vaccine becomes more widely available” (McClung et al., 2020). Establishing a fair and consistent implementation process is also an important aspect of this principle. The government should therefore not only prioritize the vaccination of detained noncitizens, but also have a concrete plan in place for how the vaccine will be distributed to this vulnerable group.

Finally, the principle of transparency supports prioritizing the vaccination of detained noncitizens because ICE’s treatment of this group is notoriously non-transparent. Privately operated detention centers, which hold the vast majority of detained noncitizens (Cullen, 2018), are especially lacking in transparency and accountability (Ryo and Peacock, 2018). For those in detention, the experience of incarceration itself further reduces trust in government (Weaver and Lerman, 2010; Muller and Schrage, 2014). At a minimum, in order to promote transparency, the government’s plan for distributing a vaccinate to detained noncitizens should be made publicly available. ICE should also provide accurate and detailed data on administration of the vaccine on its website.

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted all aspects of immigration detention in the United States, from the conditions and length of detention, to the size of the detained population, to how detained removal proceedings are conducted. Using detention only as a last resort and relying more on alternatives would mitigate both the health risks of COVID-19 and its impact on the legal rights of detained individuals. Stopping transfers between detention facilities, establishing a system to track medically vulnerable detainees long-term, prioritizing bond hearings and habeas petitions by noncitizens seeking release, and prioritizing detained noncitizens for vaccinations are all ways to mitigate these harms.

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://www.ice.gov/detention-management.

FM is the sole author of this piece.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Enforcement Actions and Title 42 Expulsions (FY 2020 and FY 2021).

Aleaziz, H. (2019). Congress has launched an investigation into the medical care of immigrant detainees, New York, NY: BuzzFeed News, https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/hamedaleaziz/congress-investigation-immigrant-detainees-medical-care (Accessed December 5, 2020).

Alvarez, P., and Sands, G. (2020). Judges rejects plea to release immigrant families in detention due to COVID-19, Atlanta, GA: CNN, https://www.cnn.com/2020/07/22/politics/immigration-detention-coronavirus/index.html (Accessed December 5, 2020). doi:10.3386/w26981

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020). Interim guidance on management of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in correctional and detention facilities, https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/correction-detention/guidance-correctional-detention.html (accessed Dec. 5, 2020)

Chapin, V. (2020). Policies and polling on the coronavirus and America’s immigrant detention crisis, the justice collaborative, https://filesforprogress.org/memos/coronavirus-detention-centers.pdf (Accessed December 5, 2020). doi:10.1093/oso/9780190081195.001.0001

Cullen, T. T. (2018). ICE released its most comprehensive immigration data yet. It’s Alarming, Chicago, IL: National Immigrant Justice Center, https://immigrantjustice.org/staff/blog/ice-released-its-most-comprehensive-immigration-detention-data-yet (Accessed December 5, 2020).

Department of Homeland Security, Office of the Inspector General (2019). Concerns About ICE Detainee Treat. Care Four Detention Facil., https://www.oig.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/assets/2019-06/OIG-19-47-Jun19.pdf (Accessed December 5, 2020).

Dooling, K., McClung, N., Chamberland, M., Marin, M., Wallace, M., Bell, B., et al. (2020). The advisory committee on immunization practices’ interim recommendation for allocating initial supplies of COVID-19 vaccine—United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 69, 1857–1859. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6949e1

Flores, V. B. (2020). Case CV 85-4544-DMG (AGRx), order re plaintiffs’ ex parte application for restraining order and order to show cause re preliminary injunction, https://www.courthousenews.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Flores-CovidTRO03282020.pdf (Accessed December 5, 2020).

Fraihat, V. (2020). U.S. Immigration and Customs enforcement, case 5-19-cv-01546-JGB-SHK (C.D. Cal. Apr. 20, 2020), Order Granting Plaintiff’s Motion for Preliminary Injunction, https://www.splcenter.org/sites/default/files/fraihat_pi_grant.pdf (Accessed December 5, 2020).

García Hernández, C. C. (2014). Immigration detention as punishment, UCLA. L. Rev. 61, 1346–1414. doi:10.5565/rev/dag.115

Hausman, D.. (2020). When immigration detention endangers the community, Pennsylvania, PA: Harvard Law Review Blog, https://blog.harvardlawreview.org/when-immigration-detention-endangers-the-community/ (Accessed December 7, 2020).

Human Rights Watch (2011). A costly move, https://www.hrw.org/report/2011/06/14/costly-move/far-and-frequent-transfers-impede-hearings-immigrant-detainees-united (Accessed December 7, 2020).

Human Rights Watch (2017). Systemic indifference: dangerous & substandard medical care in United States immigration detention, https://www.hrw.org/report/2017/05/08/systemic-indifference/dangerous-substandard-medical-care-us-immigration-detention (Accessed December 7, 2020).

Immigration and Customs Enforcement (2019a). Memorandum from nathalie R. Asher Field Off. Directors, “Migrant Prot. Protoc. Guidance,” February 12, 2019, https://www.ice.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Fact%20sheet/2019/ERO-MPP-Implementation-Memo.pdf (Accessed December 7, 2020).

Immigration and Customs Enforcement (2019b). FY19 detention statistics, https://www.ice.gov/detention-management (Accessed December 7, 2020).

Immigration and Customs Enforcement (2020a). ICE guidance on COVID-19, ICE detainee statistics, https://www.ice.gov/coronavirus (Accessed December 7, 2020).

Immigration and Customs Enforcement (2020b). FY20 detention statistics, https://www.ice.gov/doclib/detention/FY20-detentionstats.xlsx (Accessed December 7, 2020).

Immigration and Customs Enforcement (2020c). Memorandum to detention warden and superintendents, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), action plan, revision 1, March 27, 2020, https://www.aila.org/infonet/ice-memo-covid19-ice-dedicated-facilities (Accessed December 7, 2020).

Immigration and Customs Enforcement (2020d). Updated guidance: COVID-19 detained docket review—effective immediately, April 4, 2020, https://www.ice.gov/doclib/coronavirus/attk.pdf (Accessed December 7, 2020).

Immigration and Customs Enforcement (2020e). FY21 detention statistics (tab titled “detention FY21 YTD”), https://www.ice.gov/doclib/detention/FY21-detentionstats.xlsx (Accessed December 7, 2020).

Immigration and Customs Enforcement (2020f). Enforcement and removal operations. COVID-19 pandemic response requirements, version 1.0 (updated on April 10, 2020),https://www.ice.gov/doclib/coronavirus/eroCOVID19responseReqsCleanFacilities-v1.pdf (Accessed December 7, 2020).

Immigration and Customs Enforcement (2020g). Enforcement and removal operations. COVID-19 pandemic response requirements (version 5.0, Oct. 27, 2020), https://www.ice.gov/doclib/coronavirus/eroCOVID19responseReqsCleanFacilities.pdf (Accessed December 7, 2020).

Immigration and Customs Enforcement Health Service Corps (2020). Interim reference sheet on 2019-novel coronavirus (COVID-19), version 6.0, March 6, 2020, https://www.aila.org/infonet/ice-interim-reference-sheet-coronavirus (Accessed December 7, 2020).

Kullgren, I. (2020). ICE to scale back arrests during coronavirus pandemic, politico, mar. 18 https://www.politico.com/news/2020/03/18/ice-to-scale-back-arrests-during-coronavirus-pandemic-136800 (Accessed December 7, 2020).

Leung, J., Elson, D., Sanders, K., Marin, M., Leos, G., Cloud, B., et al. (2019). Notes from the Field: mumps in detention facilities that house detained migrants - United States, september 2018-august 2019. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 68:749–750. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6834a4

Marouf, F. E. (2017). Alternatives to immigration detention, Cardozo L. Rev. 38, 101. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3048480

McClung, N., Chamberland, M., Kinlaw, K., Matthew, D. B., Wallace, M., Bell, B., et al. (2020). The advisory Committee on immunization practices’ ethical Principles for allocating initial Supplies of COVID-19 vaccine—United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 69, 1782–1786. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6947e3

Meyer, J. P., Franco-Paredes, C., Parmar, P., Yasin, F., and Gartland, M. (2020). COVID-19 and the coming epidemic in US immigration detention centres. Lancet Infect. Dis. 20, 646–648. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30295-4

Muller, C., and Schrage, D. (2014). Mass imprisonment and trust in the law. Annals Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci. 651, 139–158. doi:10.1177/0002716213502928

Olivo, A., and Miroff, N. (2020). ICE flew detainees to Virginia so the planes could transport agents to D.C. protests. A huge coronavirus outbreak followed, Wash. Post., Sep 11, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/coronavirus/ice-air-farmville-protests-covid/2020/09/11/f70ebe1e-e861-11ea-bc79-834454439a44_story.html (Accessed December 7, 2020).

Ryo, E. (2019b). Understanding immigration detention: causes, conditions, and consequences. Annu. Rev. L. Soc. Sci. 15, 97–115. doi:10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-101518-042743

Ryo, E. (2019c). Predicting danger in immigration courts. L. Soc. Inq. 44, 227–256. doi:10.1017/lsi.2018.20

Ryo, E., and Peacock, I. (2018). A national Study of immigration Detention in the United States, S. Cal. L. Rev. 92 (1), 39.

Sacchetti, M., and Hernández, A. R.. (2020). ICE to stop most immigration enforcement inside U.S., will focus on criminals during coronavirus outbreak, Washington, DC: Washington Post.

Schriro, D. (2020). Declaration of dr. Dora schriro in support of petitioners’ emergency petition for a writ of habeas corpus and motion for a temporary restraining order and/or preliminary injunction, dembele v. Prim, Case 1:20-cv-02401 (N.D. Ill. Apr. 17, 2020), https://www.aclu-il.org/sites/default/files/field_documents/declaration_of_schriro.pdf (Accessed December 7, 2020).

Seville, L. R., and Rappleye, H. (2020). ICE keeps transferring detainees around the country, leading to COVID-19 outbreaks, NBC news, may 31, 2020, https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/immigration/ice-keeps-transferring-detainees-around-country-leading-covid-19-outbreaks-n1212856 (Accessed December 7, 2020).

Solis, D.. (2020). Virus began spreading in Texas detention center as positive immigrants were quickly transferred in from northeast, dallas morning news, apr 27, 2020, https://www.dallasnews.com/news/public-health/2020/04/27/virus-began-spreading-in-texas-detention-center-as-positive-immigrants-were-quickly-transferred-in-from-northeast/ (Accessed December 7, 2020).

Solis, J., Franco-Paredes, C., Henao-Martínez, A. F., Krsak, M., and Zimmer, S. M. (2020). Structural vulnerability in the U.S. Revealed in three waves of COVID-19. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hygv.103 103, 25. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.20-0391

Stumpf, J. (2006). The crimmigration crisis: immigrants, crime, and sovereign power, American U. L. Rev. 56, 367–419.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (2020). Congressional semi-monthly report 10-01-19 to 10-31-20, https://www.uscis.gov/tools/reports-and-studies/semi-monthly-credible-fear-and-reasonable-fear-receipts-and-decisions (Accessed December 7, 2020).

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (2020a). FY 2020 nationwide enforcement Encounters: Title 8 enforcement actions and Title 42 expulsions, https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/cbp-enforcement-statistics/title-8-and-title-42-statistics-fy2020 (Accessed December 7, 2020).

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (2020b). U.S. Border patrol monthly enforcement Encounters 2021: Title 42 expulsions and Title 8 apprehensions, https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/cbp-enforcement-statistics/title-8-and-title-42-statistics (Accessed December 7, 2020).

Weaver, V. M., and Lerman, A. E. (2010). Political consequences of the carceral state. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 104, 817–833. doi:10.1017/s0003055410000456

World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe (2020). Preparedness, prevention, and control of COVID-19 in prisons and other places of detention, interim guidance, March 15, 2020, https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/336525/WHO-EURO-2020-1405-41155-55954-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (Accessed December 7, 2020).

Keywords: immigration, migration, detention, removal, deportation, incarceration, asylum, COVID-19

Citation: Marouf FE (2021) The Impact of COVID-19 on Immigration Detention. Front. Hum. Dyn 2:599222. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2020.599222

Received: 26 August 2020; Accepted: 16 December 2020;

Published: 08 April 2021.

Edited by:

Jaya Ramji-Nogales, Temple University, United StatesReviewed by:

César García Hernández, University of Denver, United StatesCopyright © 2021 Marouf. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fatma E. Marouf, ZmF0bWEubWFyb3VmQGxhdy50YW11LmVkdQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.