- 1First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, China

- 2School of Nursing and Health, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, China

- 3School of Nursing and Public Health, The University of Dodoma, Dodoma, Tanzania

Aim: There are limited studies in Tanzania concerning the modality of preparing patient navigators and the influence of patient navigation strategies on cervical cancer screening. This protocol describes the preparation of patient navigators and assesses the impact of a patient navigation strategy on promoting cervical cancer screening uptake, knowledge, awareness, intention, and health beliefs.

Design: This is a protocol for a community-based randomized controlled trial.

Methods: The method is categorized into two phases. (1) Preparing patient navigators, which will involve the training of five patient navigators guided by a validated training manual. The training will be conducted over three consecutive days, covering the basic concepts of cervical cancer screening and guiding navigators on how to implement a patient navigation strategy in the communities. (2) Delivering a patient navigation intervention to community women (COMW) which will involve health education, screening appointments, navigation services, and counseling. The study will recruit 202 COMW who will be randomized 1:1 by computer-based blocks to either the patient navigation intervention group or the control group.

Public contribution: The study will prove that the trained patient navigators are easily accessible and offer timely and culturally acceptable services to promote cervical cancer screening uptake in communities.

Introduction

Globally, cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer (1), and a leading cause of death (2). An estimated 569,847 new cervical cancer cases and 311,365 deaths worldwide occur annually (3). The rate of new cervical cancer cases is 7.5 per 100,000 women per year, and the death rate is 2.2 per 100,000 women per year (4). Cervical cancer can often be prevented by having regular screenings to find any precancerous conditions and treat them (5). Even though the World Health Organization (WHO) has adopted a global strategy for eliminating cervical cancer by ensuring that 70% of the population is screened and 90% of those diagnosed with cervical cancer disease are treated (6), the screening status remains unsatisfactory in developing countries (7).

Cervical cancer in Tanzania

The incidence rate of cervical cancer in Tanzania is 54 per 100,000 (8–10), which is the fifth highest in the world (11). Despite the fact that cervical cancer screening (CCS) services in Tanzania are free of cost (12, 13), only 6%–21% of women participate in CCS (14). A knowledge deficit about the disease and screening remains a predominant factor for poor participation in CCS (15). Public health education is a recommended approach to improve the proportion of screening uptake (16).

Harold P. Freeman initiated patient navigation in the 1990s to eliminate barriers to a timely diagnosis of breast cancer and treatment and reduce cost, whereby the result was a drop in late-stage diagnosis from 50% to 20% and an increase in survival from 39% to 70% (17). The patient navigation approach has been widely applied to promote CCS behavior in women (9). In many studies, patient navigators are referred to as community health workers (CHWs) (18–22). Patient navigators have successfully influenced many women to utilize CCS services (18, 19, 20–27, 28, 29), with increased participation of women in screening ranging from 56% to 89% (19, 20, 23, 24, 27, 28). This is because CHWs not only deliver education but also help women overcome screening barriers (18, 30, 31). Women who receive education from patient navigators have an increased knowledge and positive perception of CCS (19, 22). Education delivered by patient navigators is provided in a culturally accepted manner as they live in the same community as the women who receive the teaching (32), and follow-ups conducted by patient navigators for the women who receive the education are very effective (9, 33). Even though patient navigation is an important approach to increasing CCS uptake, there is a lack of studies in Tanzania concerning how to prepare patient navigators and the effect of a patient navigation strategy in promoting screening uptake. Therefore, the proposed study aims to assess a systematic approach to preparing patient navigators and assess the impact of patient navigation on promoting screening uptake, knowledge, awareness, health beliefs, and intention.

Methods

Since the study involves the preparation of patient navigators and the implementation of patient navigation for community women (COMW), separate detailed methodologies are described below.

Preparation of the patient navigators

Recruitment of potential patient navigators

Patient navigators are defined as the health workforce conducting outreach beyond healthcare facilities or who are based at peripheral health posts that are not staffed by doctors or nurses, who are either paid or volunteers, who are not licensed, and who have fewer than 2 years of training but at least some training, if only a few hours (34). The roles of patient navigators involve community mobilization, health promotion, provision of preventive services, provision of clinical services, epidemographic surveillance, and record-keeping (35). Therefore, non-healthcare professionals who are considered to be potential patient navigators will be recruited into the study through purposive sampling. The recruitment process will involve local community leaders who will propose the potential participants. Participants will be recruited if they are women, residents of the study area (21, 29, 36, 37), have community influence, are well respected in their communities, and have a secondary/high school/university level of education (19, 36). All the suggested participants will be visited by healthcare professionals at their homes to ask about their interests and willingness and further check whether they are eligible. Ten eligible patient navigators will be asked to give their informed consent (19, 24, 26, 29), administered a baseline questionnaire, and invited to participate in the training sessions.

Training patient navigators

The training of five patient navigators will be facilitated by a nurse with a master's degree in oncology nursing who is currently working in the cervical cancer screening department. The training will be conducted using a training manual that is already developed by the principal investigator. The development of the manual has undergone five steps: (i) development of the first draft of the training manual through a systematic review study (38), (ii) revision of the training manual based on the available content in the World Health Organization facilitator guide (39), (iii) revision of the training manual based on a cross-sectional study (40), (iv) revision of the training manual based on an expert's comments, and (v) translation of the training manual from English into Swahili. The theory of planned behavior (TPB) and the health belief model (HBM) were used during the development process.

Patient navigators will receive training on three consecutive days (19, 21, 25, 26, 29, 41) from 9:00 a.m. until the scheduled activities for the day are accomplished (41). A healthcare professional will facilitate the training in Swahili (19, 24, 26, 29). Even after the 3-day training, the healthcare professional will continue to provide ongoing education to enable the patient navigators to acquire more knowledge and skills (21, 24, 29). In the 3-day training, seven sessions will be conducted. The training will begin with a 1-h open session; the patient navigators will be registered and welcomed to the training, followed by a self-introduction from the healthcare professional and the patient navigators. The healthcare professional will clearly state the goal, objectives, and rules of the training. Interactive learning visual aids, discussions, and role-playing will be used throughout the sessions. A PowerPoint (PPT) and projector will be used during the training. The healthcare professionals should prepare marker pens, notebooks, whiteboards, blackboards, and all other required teaching materials. There will be breaks between sessions with free lunches and drinks.

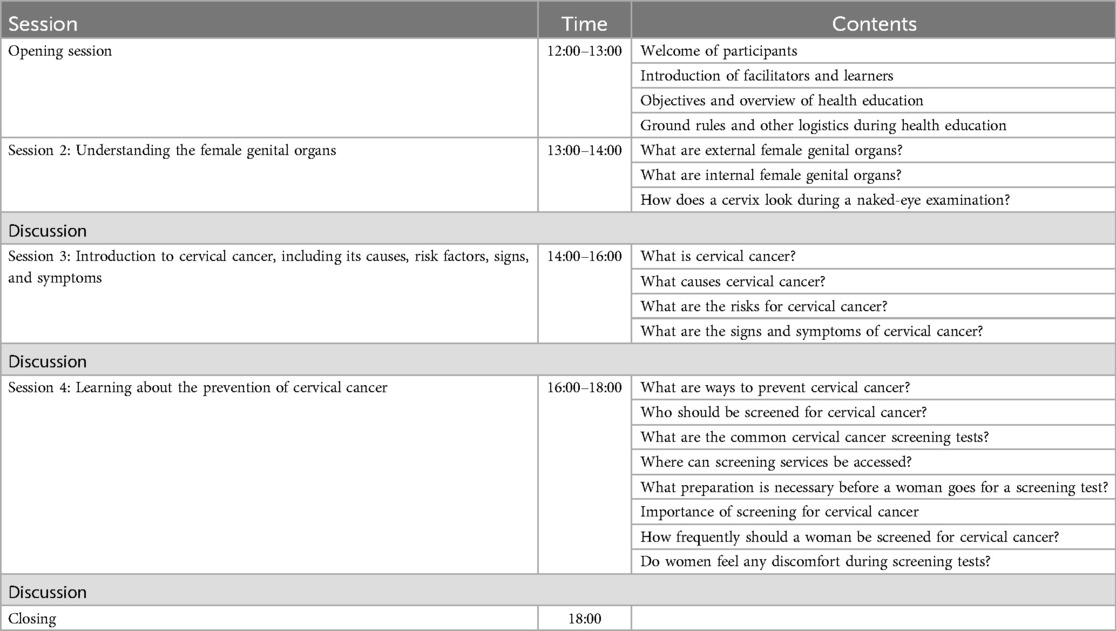

Table 1 shows details about the content to be delivered on specific days and in specific sessions, as explored in different studies (18, 23, 25, 26, 29). The first day will have two sessions with 1 h for each session. Session 1 will cover the roles of patient navigators while in session 2, patient navigators will learn about female reproductive organs. The second day will have a total of two sessions, whereby session 3 will last for 4 h to cover an introduction to cervical cancer, including the cause, risk factors, signs, and symptoms of cervical cancer. Session 4 is scheduled for 2 h and will cover preventive measures for cervical cancer. Furthermore, the third day will have three sessions, of which session 5 will last for 1.5 h and the patient navigators will learn how to deliver health education and encourage women to complete screening. Session 6 is scheduled for 2 h, teaching patient navigators about home visits, especially the importance of home visits, and how to talk to a woman who misses her scheduled appointment date. Session 7 will last for 2 h, teaching the patient navigators about healthcare facilities with cervical cancer screening services.

Implementation of patient navigation for community women

Study design, population, and setting

This will be a community-based randomized controlled trial to assess the effect of the patient navigation strategy on promoting cervical cancer screening, knowledge, health beliefs, and intention among community women. The study population is women living in a community in the Dar es Salaam region of Tanzania.

Sample size determination of COMW

The sample size for the COMW has been calculated through G-Power software (42) and is based on the outcome variable of completion of screening at a 6-month follow-up. Using the F-test, with an effect size of f = 0.3, α err prob = 0.05, and power (1 − β err prob) = 0.83, the sample size of community women to be recruited will be 202 (intervention group = 101 and control group = 101).

Recruitment of the COMW

After the 3-day training, the patient navigators and researchers will conduct one-to-one home visits to select participants from the Kinondoni ward in Dar es Salaam. Through a systematic sampling technique, the nth house will be selected and only one eligible woman will be recruited per household. Simple random sampling will be applied whenever more eligible women are found in one house to select only one participant. The inclusion criteria will be COMW aged 21–50 (18–23, 25, 27–29), no previous history of cancer (20, 23, 25, 27, 28), no previous CCS tests (22), able to speak native Swahili language (19, 21, 23), no plan to move residence during the 6-month study period (19, 23, 27), non-pregnant (22), and willing to participate in the study (21–23). They will be excluded from the study only if they are unable to comprehend the information provided due to mental illness and if they have mobility difficulties, and those who are absent at the time of collecting baseline data will also be excluded. The patient navigators will provide details about the study and will ask the COMW to complete the consent process. The researchers will administer questionnaires to obtain baseline data for all the eligible COMW willing to participate in the study (21–23).

Randomization

The study participants will be randomized 1:1 into the intervention group (n = 101) and control group (n = 101). A random sequence will be generated in an Excel spreadsheet, followed by the use of the Excel RAND function-random number-sort. The COMW in the intervention group will be notified of the date and place of the intervention.

Intervention group

The participants randomly assigned to the intervention group will receive health education, help to schedule screening appointments, navigation services, counseling, and follow-up care from the patient navigators. Regarding health education, each patient navigator will deliver a one-time group education session for 13 COMW (19–23, 28) that will last for 6 h (21, 28). The education session will be interactive and conducted using a PowerPoint, projector, and flipchart to help the COMW understand the content clearly (18–23, 25, 29). During the education session, free drinks will be given to the COMW to make them feel comfortable. The education session will have 4 sessions within the 6 h, whereby session 1, scheduled for 1 h, will be an opening session that allows everyone to introduce themselves and the objective and logistics to be communicated. Session 2 is scheduled for 1 h to cover female reproductive organs and session 3, scheduled for 2 h, is an introduction to cervical cancer, including the cause, risk factors, signs, and symptoms of cervical cancer. Session 4 is scheduled for 2 h to cover the preventive measures for cervical cancer. Please refer to Table 2 for further details. After delivering this one-time health education to the COMW, the patient navigators will begin to provide navigation services during follow-ups, such as scheduling screening appointments, escorting the women to the screening center, taking care of the mother's child, encouraging participants to attend the screening centers for their appointments, and counseling to those who fail to attend the screening center for their appointment.

Control group

The participants randomized to the control group will continue to receive the usual care from the national awareness-raising campaign and information from different media, friends, and relatives.

Data collection and measures

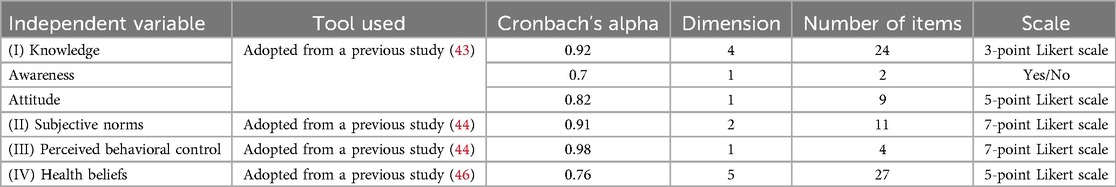

Data will be collected before and after the training of the patient navigators to evaluate whether the training has caused changes in screening knowledge, health beliefs, and skills in providing the intervention. The data will be collected through the adopted questionnaires including those for knowledge and awareness by Khosravi et al. (43), subjective norms by Ogilvie (44), perceived behavioral control by Ogilvie et al. (45), and health beliefs by Ma et al. (46). All the questionnaires are reliable, with acceptable Cronbach's alpha values. For instance, the questionnaire for knowledge, awareness, attitude, and practice has a Cronbach's alpha value ranging from 0.8 to 0.95 on a 3-point Likert scale. The subjective norms questionnaire has a Cronbach's alpha value of 0.83 on a 7-point Likert scale, and the health beliefs questionnaire has a Cronbach's alpha value ranging from 0.75 to 0.88 on a 5-point Likert scale. Please refer to Table 3 for further details. All the questionnaires have been translated into Swahili.

The COMW will be assessed for whether the intervention by the patient navigators has changed their screening knowledge, attitude, screening intention, and readiness to utilize screening. The COMW will be assessed by a similar questionnaire that will assess the patient navigators. The data will be collected at baseline (T0), immediately after the intervention (T1), after 3 months (T2), and at the exit at 6 months (T3). The T2 and T3 data collection will be conducted in the households. Finally, the data on whether the participant has been screened or not will be self-reported by the participants and confirmed at the screening facilities.

Analysis

All data will be entered and analyzed in SPSS version 21 software. To analyze the data from CHWs before and after their training, frequency and proportion will be used for the categorical variables and means for the continuous variables. Changes in knowledge, attitude, health beliefs, and screening intention will be analyzed using the independent sample t-test and linear regression.

The data from the COMW at baseline, 3-month follow-up, and 6-month follow-up will be analyzed using descriptive statistics (frequency and proportion), the independent sample t-test, linear regression, and a repeated measures ANOVA. Furthermore, principal components analysis (PCA) will be used to identify the frequency (N) and percentage (%) of respondents with awareness, knowledge, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and health beliefs regarding cervical cancer and CCS.

Outcome variables

The primary outcome of this study is the completion of CCS within 6 months in both the intervention group and control group (9–36, 39–41). Above 50% will indicate optimal screening uptake. The secondary outcome is the change in the level of knowledge, awareness, intention, and health beliefs toward cervical cancer and screening among the patient navigators and COMW after the training and education sessions (9, 47–50). For group items, >50% will indicate adequate knowledge, positive attitude, positive health beliefs, and being unaware of cervical cancer and CCS. Social demographic characteristics will be assessed to identify their association with the uptake of CCS services.

Ethical consideration

The study protocol was approved by the University of Dodoma Research Ethical Committee with approval number (UDOM/DRP/134/VOL IV/42). An informed consent form will be signed by each participant to indicate their willingness to participate. The participants will have the freedom to withdraw from the study if they wish to do so. The records of this study will be kept private.

Discussion

More funds have been spent to train health professionals and send them to communities to promote awareness of the disease and speak on the significance of screening tests (51). Despite these efforts, the proportion of women utilizing screening services remains small (16, 50–53). Several factors have been reported that hinder women from attending screening services in Tanzania in different studies, including a lack of support from their husbands, long distance to the screening clinics, and cultural norms (11), but a knowledge deficit about cervical cancer is considered the main hindrance and this should be addressed to increase the participation of women in CCS services (52).

The training of patient navigators in Tanzania is possible as women with a secondary education level and above are available and most of them are not employed. Furthermore, the training of patient navigators is possible because Tanzania currently has nurses and doctors in oncology who are capable of conducting the training of patient navigators.

The outcome of patient navigation is hypothetically assumed to be positive, with increases in screening uptake and knowledge, positive health beliefs, and intention. This should be associated with the proximity of the patient navigators and the COMW. Since they live in the same area, know each other, and share most of the cultural elements, they are likely to listen to each other and cooperate on whatever is agreed. When patient navigators deliver health education, it is likely to be well received and understood because it is delivered in a non-formal structure. Furthermore, when the patient navigators ask the COMW to screen for cervical cancer, they are likely to do so because the patient navigators could conduct a follow-up at any time at their homes. Therefore, COMW may screen not because of health education, but because they know the patient navigators will conduct a follow-up. Meanwhile, when women are asked to become patient navigators, they accept because they know it will benefit them financially. Since they consider this work as employment, an allowance inevitably amplifies their commitment to learning and implementing. Therefore, based on the definition that patient navigators can be volunteer or be paid, in the Tanzanian context, paying patient navigators is good, as volunteering could be associated with the poor implementation of patient navigation. This is consistent with a previous study that reported that patient navigators’ incentives and remuneration are core issues that affect the performance of individual patient navigators and the overall performance of the CHW program. This previous study recommends that patient navigators receive a financial package that corresponds to their job demands, complexity, number of hours worked, training, and the roles they undertake (54).

The patient navigators will deliver education to community women aged ≥21 and ≤75 years old (18–23, 25, 27–29). They must be willing to participate in the study (21–23), have no previous history of cancer or medical problem (20, 23, 25, 27, 28), speak their native language or English (19, 21, 23), have no plan to change their living residence during the study period (19, 23, 27), be non-adherent to the screening test guidelines (20, 25, 28), and have not undergone previous screening tests (21, 22). A one-time education session conducted by trained lay personnel lasting for 2 h is recommended to be adequate for imparting knowledge to women (21, 28). The education should be conducted in small groups of four to eight community women (19–23, 28). Community women should complete the screening test within 6 months after receiving the education from the trained lay personnel (18, 19, 21, 23, 29). The educational sessions conducted by trained lay personnel should be paired with other educational materials (18–23, 25, 29). After the educational intervention, the patient navigators will provide navigation services to women including financial assistance, organizing transportation services and childcare, and assisting women with language barriers to attend the screening tests (19–21, 24, 25). The patient navigators will also schedule appointment dates for the women (24, 25). The patient navigators will conduct a follow-up by telephone, a letter, mail, or home visits (19–24, 28) to remind the women to go for screening or identify their barriers to doing so. The follow-up is commonly conducted 6 months after the education is delivered to the community women (20, 21, 28).

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Dodoma. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

JM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend gratitude to the School of Nursing and Health of Zhengzhou University in China and the University of Dodoma in Tanzania for their encouragement and financial support, respectively. We also thank Dr. Golden Masika and Mr. Vincent Bankanie, who are lecturers at the University of Dodoma, for their guidance in the research methodology.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Fentie AM, Tadesse TB, Gebretekle GB. Factors affecting cervical cancer screening uptake, visual inspection with acetic acid positivity and its predictors among women attending cervical cancer screening service in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Women’s Health. (2020) 20(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12905-019-0871-6

2. National Cancer Institute Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results Program. Cervical Cancer Statistics. United States of America: National Cancer Institute Surveillance Epidemiology and end Results Program (2021). Available online at: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/cervix.html (cited April 6, 2022).

3. Gesink MP, Chamberlain RM, Mwaiselage J, Kahesa C, Jackson K, Mueller W, et al. Quantifying the under-estimation of cervical cancer in remote regions of Tanzania. BMC Cancer. (2020) 20(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-07439-3

4. National Cancer Institute Surveillance Epidemiology and end Results Program. Cancer Stat Facts: Cervical Cancer. United States of America: National Cancer Institute Surveillance Epidemiology and end Results Program (2021). Available online at: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/cervix.html (cited 2022 April 6).

5. Cancer.Net. Cervical Cancer: Screening and Prevention. United States of America: Cancer.Net (2020). Available online at: https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/cervical-cancer/screening-and-prevention (cited 2022 April 6).

6. World Health Organization. Cervical Cancer. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (2022). Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cervical-cancer (cited 2022 April 6).

7. Urasa M, Darj E. Knowledge of cervical cancer and screening practices of nurses at a regional hospital in Tanzania. Afr Health Sci. (2011) 11(1):48–57. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2017-0444

8. Lovgren K, Soliman AS, Ngoma T, Kahesa C, Meza J. Characteristics and geographic distribution of HIV-positive women diagnosed with cervical cancer in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Int J STD AIDS. (2016) 27(12):1049–56. doi: 10.1177/0956462415606252

9. Bateman LB, Blakemore S, Koneru A, Mtesigwa T, Mccree R, Lisovicz NF, et al. Barriers and facilitators to cervical cancer screening, diagnosis, follow-up care and treatment: perspectives of human immunodeficiency virus-positive women and health care practitioners in Tanzania. TheOncologist. (2018) 24:1–7. Available online at: www.TheOncologist.com

10. O’Sullivan É. Cervical Cancer Prevention and Treatment Training in Tanzania. Geneva, Switzerland: Pepal (2018). p. 1. Available online at: file:///F:/Cervical cancer prevention and treatment training in Tanzania — Pepal.html.

11. Morrison PB. Preventing Cervical Cancer in Rural Tanzania: A Program Model for Health Worker Trainings. Tanzania: Texas Medical Center Library (2015).

12. Nelson S, Kim J, Wilson FA, Soliman AS, Ngoma T, Kahesa C, et al. Cost-effectiveness of screening and treatment for cervical cancer in Tanzania: implications for other Sub-Saharan African countries. Value Health Reg Issues. (2016) 10:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.vhri.2016.03.002

13. Linde DS, Rasch V, Mwaiselage JD, Gammeltoft TM. Competing needs: a qualitative study of cervical cancer screening attendance among HPV-positive women in Tanzania. BMJ open. (2019) 9(e02401):1–8. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024011

14. Runge A, Bernstein M, Lucas A, Tewari KS. Cervical cancer in Tanzania a systematic review of current challenges in six domains. Gynecol Oncol Rep. (2019) 29:40–7. doi: 10.1016/j.gore.2019.05.008

15. Pernga P, Perng W, Ngoma T, Kahesa C, Mwaiselage J, Merajver SD, et al. Promoters of and barriers to cervical cancer screening in a rural setting in Tanzania. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. (2013) 123(3):221–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.05.026

16. Cunningham MS, Skrastins E, Fitzpatrick R, Jindal P, Oneko O, Yeates K, et al. Cervical cancer screening and HPV vaccine acceptability among rural and urban women in Kilimanjaro region, Tanzania. BMJ Open. (2015) 5(3):e005828–9. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005828

17. Patterson A. An overview of patient navigation, its history, and core competencies. Acad Oncol Nurse Patient Nav. (2016) 7(3). Available online at: https://www.jons-online.com/issues/2016/april-2016-vol-7-no-3/1416-an-overview-of-patient-navigation-its-history-and-core-competencies

18. Mbah O, Ford JG, Qiu M, Wenzel J, Bone L, Bowie J, et al. Mobilizing social support networks to improve cancer screening: the COACH randomized controlled trial study design. BMC Cancer. (2015) 15(907):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1920-7

19. Han H, Song Y, Kim M, Hedlin HK, Kim K, Ben LH, et al. Breast and cervical cancer screening literacy among Korean American women: a community health worker-led intervention. Am J Public Health. (2017) 107(1):159–65. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303522

20. Ma GX, Fang C, Tan Y, Feng Z, Ge S, Nguyen C. Increasing cervical cancer screening among Vietnamese Americans: a community-based intervention trial. J Health Care Poor Underserved. (2015) 26(2):36–52. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2015.0064

21. Schuster ALR, Frick HD, Huh B-Y, Kim KB, Kim M, Han H-R. Economic evaluation of a community health worker-led health literacy intervention to promote cancer screening among Korean American women. J Health Care Poor Underserved. (2015) 26(2):431–40. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2015.0050

22. Rosser JI, Njoroge B, Huchko MJ. Changing knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors regarding cervical cancer screening: the effects of an educational intervention in rural Kenya. Patient Educ Couns. (2015) 98(7):884–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.03.017

23. Tong EK, Nguyen TT, Lo P, Stewart SL, Gildengorin GL. Lay health educators increase colorectal cancer screening among Hmong Americans: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Cancer. (2017) 123(1):98–106. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30265

24. Braun KL, Thomas WL, Domingo JB, Allison AL, Ponce A, Kamakana PH, et al. Reducing cancer screening disparities in Medicare beneficiaries through cancer patient navigation. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2015) 63(2):365–70. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13192

25. Thompson B, Carosso EA, Jhingan E, Wang L, Holte SE. Results of a randomized controlled trial to increase cervical cancer screening among rural Latinas. Cancer. (2017) 123(4):666–74. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30399

26. Ngoma T, Mandeli J, Holland JF. Downstaging cancer in rural Africa. Int J Cancer. (2015) 136(12):2875–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29348

27. Shastri SS, Mittra I, Mishra GA, Gupta S, Dikshit R, Singh S, et al. Effect of VIA screening by primary health workers: randomized controlled study in Mumbai, India. J Natl Cancer Inst. (2014) 106(3):1–7. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju009

28. Fang CY, Ma GX, Handorf EA, Feng Z, Tan Y, Rhee J, et al. Addressing multilevel barriers to cervical cancer screening in Korean American women: a randomized trial of a community-based intervention. Cancer. (2017) 123(6):1018–26. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30391

29. Dunn SF, Lofters AK, Ginsburg OM, Meaney CA, Ahmad F, Moravac MC, et al. Cervical and breast cancer screening after CARES: a community program for immigrant and marginalized women. Am J Prev Med. (2017) 52(5):589–97. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.11.023

30. Bellhouse S, French DP, Mcwilliams L, Firth J, Yorke J. Are community-based health worker interventions an effective approach for early diagnosis of cancer? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psycho-Oncology. (2018) 27:1089–99. doi: 10.1002/pon.4575

31. Muliira JK, Souza MSD. Effectiveness of patient navigator interventions on uptake of colorectal cancer screening in primary care settings. Jpn J Nurs Sci. (2016) 13(2):205–19. doi: 10.1111/jjns.12102

32. Wells KJ, Rivera MI, Proctor SSK, Bynum SA, Quinn GP, Luque JS, et al. Creating a patient navigation model to address cervical cancer disparities in a rural Hispanic farmworker community. J Health Care Poor Underserved. (2012) 23(4):1712–8. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2012.0159

33. Markossian TW, Darnell JS, Calhoun EA. Follow-up and timeliness after an abnormal cancer screening among underserved, urban women in a patient navigation program. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. (2013) 21:1–20. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0535

34. United Nations Children’s Fund, World Health Organization, Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women, Gavi the VA. Guidance for Community Health Worker Strategic Information and Service Monitoring. New York: UNICEF (2021). p. 1–124. Available online at: file:///C:/Users/dora deo gerald/Downloads/210305_UNICEF_CHW_Guidance_EN.pdf

35. Glenton C, Javadi D, Perry HB. Community health workers at the dawn of a new era: 5. Roles and tasks. Health Res Policy Syst. (2021) 19(3):1–17. doi: 10.1186/s12961-021-00748-4

36. Mbachu C, Dim C, Ezeoke U. Effects of peer health education on perception and practice of screening for cervical cancer among urban residential women in South-east Nigeria: a before and after study. BMC Women’s Health. (2017) 17(41):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12905-017-0399-6

37. Fleming K, Simmons VN, Christy SM, Sutton SK, Romo M, Luque JS, et al. Educating Hispanic women about cervical cancer prevention: feasibility of a promotora-led charla intervention in a farmworker community. Ethn Dis. (2018) 28(3):169–76. doi: 10.18865/ed.28.3.169

38. Mboineki JF, Wang P, Chen C. Fundamental elements in training patient navigators and their involvement in promoting public cervical cancer screening knowledge and practices: a systematic review. Cancer Control. (2021) 28:10732748211026670. doi: 10.1177/10732748211026670

39. World Health Organization. Cervical Cancer Screening and Management of Cervical pre-cancers: Trainees’ Handbook and Facilitators’ guide. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (2017). Available online at: file:///C:/Users/dora deo gerald/Downloads/programme-manager-manual.pdf

40. Mboineki JF, Wang P, Dhakal K, Amare M, Cleophance W, Changying M. Predictors of uptake of cervical cancer screening among women in urban Tanzania: community-based cross-sectional study. Int J Public Health. (2020) 65:1593–602. doi: 10.1007/s00038-020-01515-y

41. World Health Organization. Training of Community Health Workers. New Delhi: World Health Organization (2017). Available online at: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&url=http://www.searo.who.int/entity/maternal_reproductive_health/documents/chwm.pdf%3Fua%3D1&ved=2ahUKEwj6qYC8nt7iAhXsmuAKHeBwA6oQFjADegQIAxAB&usg=AOvVaw3Lemhk0pEkP3c0DEofgz0n

42. Kang H. Sample size determination and power analysis using the G*power software. J Educ Eval Health Prof. (2021) 18:17–12. doi: 10.3352/jeehp.2021.18.17

43. Khosravi M, Shafaee S, Karimi H, Haghollahi F, Ramazanzadeh F, Mamishi N. Validity and reliability of the knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) questionnaire about cervical cancer and its screening among Iranian women. Basic Clin Cancer Res. (2012) 4(1):2–7.

44. Ogilvie GS. Intention of Women to Receive Cervical Cancer Screening in the Era of Human Papillomavirus Testing. United states of America: Gillings School of Global Public Health (2012).

45. Ogilvie GS, Smith LW, Van Niekerk DJ, Khurshed F, Krajden M, Saraiya M, et al. Women’s intentions to receive cervical cancer screening with primary human papillomavirus testing. Int J Cancer. (2013) 133(12):2934–43. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28324

46. Ma GX, Gao W, Carolyn YF, Yin T, Ziding F, Shaokui G, et al. Health beliefs associated with cervical cancer screening among Vietnamese Americans. J Women’s Health. (2013) 22(3):276–88. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2012.3587

47. Pryor RJ, Masroor N, Stevens M, Sanogo K, Hernández O’Hagan PJ, Bearman G. Cervical cancer screening in rural mountainous Honduras: knowledge, attitudes and barriers. Rural Remote Health. (2017) 17(2):1–8. doi: 10.22605/RRH3820

48. Moshi F V, Vandervort EB, Kibusi SM. Cervical cancer awareness among women in Tanzania: an analysis of data from the 2011-12 Tanzania HIV and malaria indicators survey. Int J Chronic Dis. (2018) 2018:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2018/2458232

49. Napolitano M, Schonman E, Mpango E, Isdori G. Cervical Cancer and Its Impact on the Burden of Disease. New York: CUL Initiatives in Publishing (CIP) (2012). Available online at: https://ecommons.cornell.edu/bitstream/handle/1813/55686/3-14.pdf?sequence=1

50. Kahesa C, Kjaer S, Mwaiselage J, Ngoma T, Tersbol B, Dartell M, et al. Determinants of acceptance of cervical cancer screening in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. BMC Public Health. (2012) 12(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-1

51. Mabelele MM, Materu J, Ng’ida FD, Mahande MJ. Knowledge towards cervical cancer prevention and screening practices among women who attended reproductive and child health clinic at Magu district hospital, lake zone Tanzania: a cross-sectional study. BMC Cancer. (2018) 18(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4490-7

52. Lyimo FS, Beran TN. Demographic, knowledge, attitudinal, and accessibility factors associated with uptake of cervical cancer screening among women in a rural district of Tanzania: three public policy implications. BMC Public Health. (2012) 12(1):22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-22

53. Kileo NM, Michael D, Neke NM, Moshiro C. Utilization of cervical cancer screening services and its associated factors among primary school teachers in Ilala municipality, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. BMC Health Serv Res. (2015) 15(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-1206-4

Keywords: cervical cancer, screening, patient navigation, community health workers (CHW), health beliefs, knowledge

Citation: Mboineki JF and Chen C (2024) Preparing patient navigators and assessing the impact of patient navigation in promoting cervical cancer screening uptake, knowledge, awareness, intention, and health beliefs: a protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Front. Glob. Womens Health 5:1209441. doi: 10.3389/fgwh.2024.1209441

Received: 20 April 2023; Accepted: 11 November 2024;

Published: 4 December 2024.

Edited by:

Mwansa Ketty Lubeya, University of Zambia, ZambiaReviewed by:

Kathryn L. Braun, University of Hawaii at Manoa, United StatesAna Afonso, NOVA University of Lisbon, Portugal

Copyright: © 2024 Mboineki and Chen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Changying Chen, Y2hhbmd5aW5nQHp6dS5lZHUuY24=

Joanes Faustine Mboineki

Joanes Faustine Mboineki Changying Chen1*

Changying Chen1*