94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Glob. Womens Health, 14 December 2022

Sec. Maternal Health

Volume 3 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fgwh.2022.1048700

This article is part of the Research TopicSexual and Reproductive Health in Forced MigrationView all 4 articles

Milkie Vu1,2*

Milkie Vu1,2* Ghenet Besera2

Ghenet Besera2 Danny Ta3

Danny Ta3 Cam Escoffery2

Cam Escoffery2 Namratha R. Kandula1,4

Namratha R. Kandula1,4 Yotin Srivanjarean5

Yotin Srivanjarean5 Amanda J. Burks2,6

Amanda J. Burks2,6 Danielle Dimacali3

Danielle Dimacali3 Pabitra Rizal5

Pabitra Rizal5 Puspa Alay5

Puspa Alay5 Cho Htun5

Cho Htun5 Kelli S. Hall7

Kelli S. Hall7

Refugee women have poor outcomes and low utilization of sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services, which may be driven by access to and quality of SRH services at their resettled destinations. While healthcare providers offer valuable insights into these topics, little research has explored United States (U.S.) providers' experiences. To fill this literature gap, we investigate U.S. providers' perspectives of healthcare system-related factors influencing refugee women's access and utilization of SRH services. Between July and December 2019, we conducted in-depth, semi-structured interviews with 17 providers serving refugee women in metropolitan Atlanta in the state of Georgia (United States). We used convenience and snowball sampling for recruitment. We inquired about system-related resources, facilitators, and barriers influencing SRH services access and utilization. Two coders analyzed the data using a qualitative thematic approach. We found that transportation availability was crucial to refugee women's SRH services access. Providers noted a tension between refugee women's preferred usage of informal interpretation assistance (e.g., family and friends) and healthcare providers’ desire for more formal interpretation services. Providers reported a lack of funding and human resources to offer comprehensive SRH services as well as several challenges with using a referral system for women to get SRH care in other systems. Culturally and linguistically-concordant patient navigators were successful at helping refugee women navigate the healthcare system and addressing language barriers. We discussed implications for future research and practice to improve refugee women's SRH care access and utilization. In particular, our findings underscore multilevel constraints of clinics providing SRH care to refugee women and highlight the importance of transportation services and acceptable interpretation services. While understudied, the use of patient navigators holds potential for increasing refugee women's SRH care access and utilization. Patient navigation can both effectively address language-related challenges for refugee women and help them navigate the healthcare system for SRH. Future research should explore organizational and external factors that can facilitate or hinder the implementation of patient navigators for refugee women's SRH care.

Since the passage of the Refugee Act of 1980, the United States (U.S.) has admitted more than 3.1 million refugees (1). While the admission number has fluctuated each year based on global events and the priorities of different administrations, around half of resettled refugees are female (2, 3). Refugee women often face challenges and risks that are distinct from those encountered by their male counterparts (4). In particular, their history of pre-migration experiences, including torture, exposure to war, gender-based violence, and post-traumatic stress disorder (5, 6), as well as their post-migration living difficulties (7) can have negative implications for their sexual and reproductive health (SRH) (8). Indeed, U.S. and/or globally resettled refugee women are shown to have poor SRH outcomes and low knowledge and utilization of SRH services (e.g., contraceptives, cervical cancer screening, or HPV vaccination) (9–26).

Besides refugee women's pre-migration history and post-migration living conditions, a key but understudied determinant of SRH disparities experienced in this population may be access to, as well as the quality and appropriateness of SRH services at their resettled destinations (27–29). According to Liu and colleagues' framework (30), access means “an individual's ability to position oneself to receive healthcare services,” while utilization “presumes access and requires effective information exchange during a healthcare encounter.” Both healthcare access and utilization are influenced by the structure and operation of the system in which individuals receive care (30).

A recent systematic review synthesized evidence from 28 studies on access to preventive SRH care for refugee, asylum seeker, and internally displaced women in high-, middle-, and low-income host countries (31). The review found that while most existing studies have explored barriers of access, not many have focused on enablers of access. Among many challenges, in high-income host countries, refugee women face barriers in navigating and understanding the health system and making appointments for SRH care. Critically, the authors discussed how relatively few of the reviewed studies have investigated healthcare providers' perspectives and experiences providing care to refugee women.

The perspectives of healthcare providers on these issues are important as providers are at the forefront of caring for SRH needs in this population and can offer valuable insights into clinical encounters and possible challenges (32). Additionally, providers can speak about not only organizational barriers but also organizational resources and facilitators related to the delivery of SRH care. An understanding of these healthcare system-level factors is critical to ensuring health equity, as it allows for the allocation of resources to meet particular needs (33), which can subsequently increase refugee women's SRH access and utilization. Moreover, from an implementation science perspective, providers offer crucial insights on organizational inner context factors (e.g., existing programs, staffing, resources, funding) and outer context factors (e.g., interorganizational environment and networks, patient characteristics and needs) that can inform future implementation efforts to increase SRH access and care for refugee women (34).

Existing studies with providers serving refugee women have been predominantly conducted in non-U.S. settings such as Australia, Canada, or European countries (29, 35–44), with few studies based in the U.S. (32, 45–48). The non-U.S. literature has uncovered several challenges refugee women encounter in accessing services, as well as obstacles that clinicians faced in delivering high-quality, culturally-relevant health services for refugee women (29, 35, 37–41). Yet, the generalizability of non-U.S. findings to the U.S. context may be limited given differences in health insurance policy and structure of the healthcare systems. Moreover, some of the few U.S.-based studies do not distinguish between providers serving refugees, immigrants, or foreign-born individuals (32, 47), despite the fact that people's circumstances for migration as well as their official migration status greatly matter for healthcare (49–51).

To fill these gaps in the literature, we conducted a qualitative study with U.S. healthcare providers in metropolitan Atlanta about their experiences serving refugee women's SRH needs. Specifically, our study explored providers' perspectives of healthcare system-related resources, facilitators, and barriers influencing refugee women's access and utilization of SRH services. Our study uses a phenomenological approach, which investigates several individuals' shared experiences of a concept or phenomenon (e.g., providers’ experiences with refugee women's SRH access and utilization) (52).

Our study setting was the metropolitan Atlanta area, located within the state of Georgia. Georgia has historically been among the U.S. states that receive the highest numbers of resettled refugees (2, 3). For example, between 2010 and 2020, Georgia was the initial resettled destination of 4% of all refugees in the U.S. (53). A large number of refugees are concentrated in the metropolitan Atlanta area (54–57). In particular, in the past three decades, the city of Clarkston in the metropolitan Atlanta area has served as the primarily hub for refugee resettlement in Georgia and has resettled more than 40,000 refugees (58). The top countries of origins for refugees in Georgia are Burma, Congo, Syria, Afghanistan, and Bhutan (59); these are also the top countries of origins for refugees resettled in the U.S. (53).

The numbers of refugees resettled in Georgia in the years preceding the conduct of this study decreased considerably due to the reduction in the cap on refugee admissions set by the Trump Administration. For example, while 3,017 refugees were initially resettled in Georgia in fiscal year 2016 (2), only 1,182 were resettled in fiscal year 2019 (3). Moreover, despite being one of the top states in terms of refugee resettlements, the state of Georgia reportedly spends little to no state dollars to fund programs meant to specifically help refugees (60, 61). At the time of our study, Georgia ranked third worst in the U.S. regarding the uninsured rate (62), and it had not adopted a full expansion of Medicaid for its resident (63).

Between July and December 2019, we recruited 26 refugee women and 17 healthcare providers to participate in our study. The data analyzed in this manuscript focused on the 17 healthcare providers. Eligibility criteria for providers included (1) identifying as a healthcare provider and (2) previously or currently providing SRH services (e.g., family planning, sexually transmitted diseases testing, cervical cancer screening, HPV vaccination, or perinatal care) to refugee women in the metropolitan Atlanta area. We sampled providers from different occupations (e.g., physicians, nurse practitioners, registered nurses, other clinic staff). Providers were first identified through word-of-mouth recruitment at clinics that refugee women had indicated, in previous interviews, that they attended for SRH services. Additionally, we contacted community-based organizations serving refugee populations for names of clinics or providers that regularly saw refugee women for SRH visits. We also utilized snowball sampling and asked providers who were interviewed to identify other eligible providers. Providers worked at several different clinics that cared for refugee women, including federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) and charitable, volunteer-operated clinics. The a priori sample size of 15–20 was selected based on past qualitative research of similar topics (32, 39, 43, 45, 47, 48) and recommendations for sample size needed to achieve code and meaning saturation (64). The Emory University Institutional Review Board approved this study (IRB00142813).

Prior to the start of each interview, each provider gave verbal consent and answered a brief survey about their sociodemographic information. Each interview lasted 30–60 min. Participants were compensated with a $20 gift card upon interview completion. All interviews were conducted in person by two authors (MV and GB). Both interviewers were doctoral candidates trained in behavioral and social sciences and in public health, with prior formal coursework and professional experience in qualitative research. Both were also women of color and first- or second-generation immigrants in the U.S. They both had extensive personal networks, as well as professional research experience with migrants and refugees in the U.S.

The semi-structured interview guide was developed based on a conceptual model (Figure 1) that integrates the Socioecological Framework (65) and Penchansky and Thomas' Theory of Access (66). The Sociological Framework describes how engagement in SRH services utilization can be influenced by factors at multiple levels (e.g., interpersonal, healthcare systems, community, and policy) (37, 65). Interview questions also assessed the five dimensions of access (66) which involve accessibility (i.e., services proximity to ethnic enclaves or communities), availability (i.e., sufficient resources, including language services, to meet SRH needs), acceptability (i.e., services are culturally acceptable to patients), affordability (for both service providers and community members), and accommodation (defined as relationships between the structure/resources of the organization and the patient's ability to accommodate these factors, i.e., refugee women's ability to follow through on referral to other care settings).

All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by a professional audio transcription company. We analyzed the data using an inductive qualitative thematic analysis approach (67). While the theory-driven research questions outlined by the research team provided the domains of relevance for the analysis (68), identified themes and patterns were strongly data-driven. In other words, our findings arose primarily and directly from the analysis of the raw qualitative data and not a priori models or a pre-existing coding frame (68, 69). We established trustworthiness during each phase of thematic analysis by: (1) familiarizing ourselves with the data; (2) generating initial inductive codes from the qualitative data; (3) searching for themes; (4) reviewing themes; (5) defining and naming themes; and (6) producing the report (67). First, two researchers (MV and GB) read five transcripts carefully and developed a codebook with definitions (based on the initial inductive codes), inclusion and exclusion criteria, and examples. The two researchers then independently coded the initial five transcripts using the codebook. Subsequently, the two researchers met to compare coding results and reconciled any discrepancies through discussion. The two researchers then each coded six transcripts of the remaining twelve transcripts using the codebook. A third researcher (DT) reviewed these twelve coded transcripts. Any discrepancies were reconciled through discussion among the three researchers. We used researcher triangulation, vetted themes and subthemes by research team members, and reached consensus on themes (67).

To establish the significance of patterns and meaning while balancing the controversy regarding whether to quantify qualitative results (70), we operationalized the frequency of themes that appeared in interviews as “all” (100% of interviews), “almost all” (90%–99%), “most” (70%–89%), “the majority” (50%–69%), “several” (20%–49%), and “a few” (less than 20%) (71). We employed several techniques to establish and enhance validity, rigor, and trustworthiness in qualitative research, including articulating data collection and analysis decisions, providing verbatim transcription, exploring rival explanations, performing a literature review, peer debriefing, negative case analysis, and close collaboration with community partners (72–74). We used MAXQDA 2020 (75) for all qualitative data analyses and data management activities. Descriptive statistics were generated for sociodemographic characteristics in Stata 16 (76).

Table 1 displays providers' sociodemographic characteristics. The majority of providers were female (88.2%). Approximately a half identified as White and a third identified as Asian. On average, providers had 14.2 and 6.5 years of experience in healthcare and in working with refugee women, respectively. The most common occupations were physicians (29.4%) and registered nurses (29.4%). Providers mentioned that the majority of refugee patients they saw were from South and Southeast Asia (e.g., Bhutan, Nepal, and Burma), the Middle East (e.g., Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan), and East and Central Africa (e.g., Eritrea, Somalia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo).

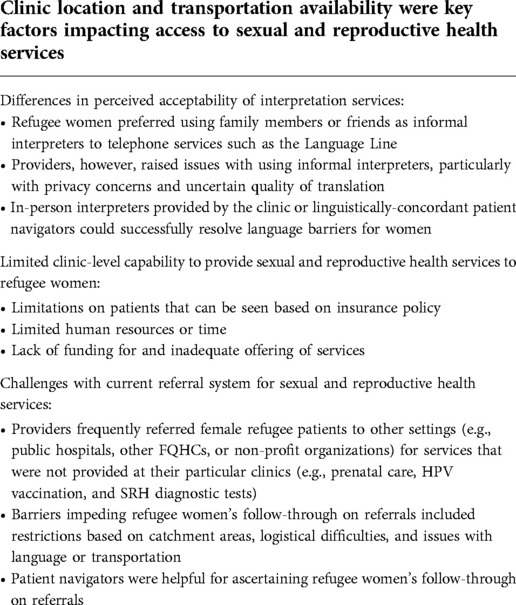

Providers described a range of healthcare system-related factors influencing refugee women's access and utilization of SRH services: clinic location and transportation availability; differences in perceived acceptability of interpretation services; limited clinical-level capability to provide SRH services; and challenges with current referral systems for SRH services. These key emergent themes are further described below and summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Healthcare system-related resources, opportunities, and barriers influencing refugee women's access and utilization of sexual and reproductive health services.

Providers often described how clinics that were centrally located within refugee communities facilitated access to services. For instance, a registered nurse said: “The location of the clinic is … very centrally located … A lot of women can walk to clinic” (#17). At the same time, several providers mentioned that for refugee women who lived in other parts of metropolitan Atlanta or for clinics that were less reachable on foot, transportation difficulties could be a major access barrier. A registered nurse discussed: “[Refugee women] are often dependent on family members, community members or individuals at the place of worship to bring them to clinic … they're not really in charge of their own time” (#16). To overcome this issue, one clinic offered their patients free transportation services to the clinic. A program coordinator described: “A lot of refugee women … don’t have transportation, but we have a transportation team on site … we do provide the transportation service” (#03).

Several providers stated that limited English proficiency was a major barrier for services access and utilization. Most providers discussed the use of on-demand telephone interpretation services. However, several providers mentioned that women with limited English proficiency would often prefer having family members or friends serve as interpreters to using telephone services. A physician said: “We typically try to use the Language Line if it's at all possible, just because that's a more accurate way of doing it … [Patients] typically will decline the phone and prefer to use their friend or family member” (#08).

Several providers discussed certain disadvantages of using on-demand telephone interpretation services. A midwife explained: “Midwifery care tends to be a conversation and we would sit in the room with somebody and provide labor support. A lot of the communication's nonverbal … The Language Line doesn’t work for casual conversation. The focus of using the Language Line is very clinical. It's not cultural … A challenge is the cost of the Language Line and getting the right translation services … They need advanced notice … before their appointment in order to get the right language available” (#09).

While having refugee women's family members or friends serving as interpreters could resolve some challenges with using telephone interpretation services, providers had mixed perceptions about this practice. A nurse practitioner (#05) remarked: “Especially when you’re talking about sexual and reproductive health, having family members is always going to be a challenge in … feeling confident that the answers that they’re giving are accurate … When we’re talking about vaginal discharge, that can be an uncomfortable conversation that you wouldn’t want to have in front of your neighbor.” Another nurse practitioner said: “Sometimes we really should be using the Language Line, but we do rely on family members, which is not the best practice. It gets the job done, but I don’t know what's being translated into” (#06).

The majority of providers stated that their clinics tried to overcome language barriers by providing in-person interpreter services for refugee women. In some cases, interpreters also assumed the job of being patient navigators for refugee women. A registered nurse said: “We did have a consistent translator who … would speak Pashto … She would help all these women navigate the system” (#10). Several providers discussed the positive impact of such services. A physician said: “For the Iraqi refugees, Syrian refugees, we have [Arabic-speaking] staff. And then we have staff from Afghanistan for the Afghani refugees. We have a couple of staff who speak Swahili … They’re hired on purpose to keep it a multilingual place, so that the patients feel comfortable” (#15). Another physician discussed: “Our Burmese navigator is here three days a week. So [the patients] want to come when the navigator is here … [The patients and the navigator] have a very strong relationship. That's great because it actually helps them with follow-ups and just with all around care” (#07).

Although providers recognized the benefits in providing in-person interpretation, it was not always feasible. A registered nurse explained: “At our clinic alone, patients speak approximately 40 different languages … there are a lot more challenges trying to deal with the broad range of diversity … It's both a good thing and a challenge at the same time” (#17). A nurse practitioner said: “[For patients that speak Arabic], occasionally we will have an interpreter on site, but not always. Some of the dialects of the African nations and the Bhutanese, Burmese can be kind of tough to find” (#05).

Most participants indicated their clinics were able to provide certain essential SRH services to refugee women, such as mammograms, Pap smears, sexually transmitted disease testing, or contraceptives. Clinics also frequently offered free or low-cost services or had sliding scale fees to assist with cost-related barriers for refugee women with low income. A physician said: “We don’t want money to be a barrier … We had a patient that just paid $5 because that's all they can pay” (#13).

A few clinics, however, faced policy constraints that limited who they could see. Therefore, even if women were able to access the clinic, they may not be able to utilize SRH services. A nurse practitioner explained: “We will only see people without insurance” (#02). Other clinic-level capacity barriers included a lack of human resources (e.g., a lack of specialists in obstetrics/gynecology) or providers’ time constraints. Some clinics operated primarily with volunteer providers, which limited the availability of appointments for refugee women. A nurse practitioner explained: “It would be great to have the clinic open even more hours. Right now it's somewhat limited … For the longest time, it was Sundays only and then it became Sundays and Fridays” (#01). A physician said: “[Patients] have to expect to be [waiting at the clinic] for probably about like three or four hours before you’re seen” (#08).

In addition, the majority of providers mentioned the lack of funding for, and consequently, the inadequate offering of SRH services at the clinics serving refugee women. The range of SRH services limited what refugee women can utilize. A physician stated: “It's just such a resource poor clinic … We don’t have ultrasound, we don’t have the ability to do prenatal care. We can’t do a lot of free birth control. Our microscope is crappy and you can’t see anything through it. There are a lot of things that could use improvement” (#08). Another physician remarked: “We can’t provide HIV testing and syphilis testing … that's one thing that we would really like to do. Being able to provide HPV vaccine [is] something we’d like to do” (#12).

Most providers discussed referring female refugee patients to other settings (e.g., public hospitals, other FQHCs, or non-profit organizations) for services that were not provided at their particular clinics (e.g., prenatal care, HPV vaccination, and SRH diagnostic tests). Several providers remarked on the challenges with this type of “fragmented” care. A nurse practitioner brought up restrictions on where patients could be referred to based on their catchment areas: “If the person doesn’t live in DeKalb or Fulton County, we can’t refer them to Grady [Memorial Hospital]” (#02). A physician discussed other logistical difficulties: “If [patients] need more than just an annual exam or a basic treatment, then they have to go to Grady [Memorial Hospital] … talk to financial, get a Grady card, get scheduled and there's a waiting period involved” (#08). Moreover, a few providers reported poor inter-clinic communication of medical records and test results.

Several providers indicated barriers that may impede refugee women's follow-through on referrals. A physician said: “What we basically do is give [female refugee patients] information and just hope that they end up going there. But they don’t have the transportation, they don’t speak the language” (#08). A registered nurse stated: “Just how complex the structure of doing a referral is, patients having … to pick up on a number they might not know … Our patients, because they’re using pay-per-use cell phones, their phone numbers are changing every time they’re in clinic and so it makes doing referrals just very hard” (#17).

Patient navigators or case managers were helpful for ascertaining follow-through on referrals. A physician said: “If [the patients are] Burmese, Nepali, Congolese or Spanish speaking, then we have a navigator for those groups. The navigator will help make the appointment, follow through with the family and try to facilitate them going, even try to help with transport … Before we had navigators, we had a lower compliance and lower ability to refer. With the navigators … it's improved” (#07).

Our study documented metropolitan Atlanta-based healthcare providers’ perceptions of healthcare system-related influences on refugee women's access and utilization of SRH services. Findings highlighted the importance of clinic-level provision of transportation and interpretation services. At the same time, several providers noted a tension between women's preference for using friends or family members as informal interpreters and providers' desire to use more formal services, such as the Language Line. In addition, the majority of providers reported a lack of clinic-level capacity or resources to provide high-quality, comprehensive SRH care for refugee women. Several providers brought up challenges with using a referral system for refugee women to get additional SRH care in other healthcare settings. Patient navigators were described as a key facilitator that helped refugee women navigate the healthcare system and increase their SRH services access and utilization.

Our findings echo those of other studies with different populations in the U.S. that have recognized transportation difficulties as a central barrier to healthcare utilization (77, 78) in general and SRH services utilization in particular (79–82). In our study, only one clinic was able to offer transportation aid to refugee women. To ameliorate SRH disparities, it is imperative that clinics providing SRH care to refugee women can receive adequate funding and support to operate similar assistance programs (83, 84). In addition to traditional non-emergency medical transportation, initiatives such as rideshare (e.g., Uber or Lyft) can be considered (85). For example, one Boston-based pilot program found that coordinating rideshares for refugee and asylum seeking women is an effective and cost-efficient strategy to increase health services access (86). In case women need to be referred from one setting to another (as commonly described by providers in our study), it is possible that transportation services can increase refugee women's follow-through on referrals.

Besides the lack of transportation programs, providers in our study reported limitations in delivering high-quality, comprehensive SRH care for refugee women due to insurance policy, unavailability of appointments, or a lack of funding for several services. The few studies assessing system-level resources among organizations in the U.S. that serve refugees have primarily focused on non-medical organizations (e.g., local nonprofit organizations, voluntary or resettlement agencies) (87, 88). Our study adds to the literature by underscoring the current constraints of clinics in the U.S. that directly provided healthcare to refugee women. Several clinics in our study depended heavily on volunteers and limited grant funding for SRH services. Such operation is not financially sustainable because the capacity or availability of volunteers and the amount of funding can vary at any given time. More long-term, financially sustainable care models for refugee health should be explored in future research (89). Given the identified barriers to follow-through on referrals (e.g., restrictions based on catchment areas, logistical difficulties), additional research is needed to explore approaches to help refugee women overcome these barriers.

To our knowledge, this study is one of the first to explore perspectives of providers in Georgia or the Southeastern U.S. on refugee women's access and utilization of SRH services. We also note that providers in our study also served refugees from diverse backgrounds instead of from one country or ethnic group, which sets our research apart from past studies (31) and enhances the external validity of our findings. Much of existing U.S.-based research on refugee women's SRH access and utilization has focused on the coasts (90) or the Midwest (14), where healthcare resources and policy differ considerably from the setting of our study. Research with the context of Georgia is highly needed given the unique nature of the state with a large population of resettled refugees from diverse origins (54–58) but also poor healthcare access (e.g., third worst uninsured rate in the U.S.) (62) and restrictive healthcare policy (e.g., lack of full Medicaid expansion, restrictive abortion laws) (63, 91). While the scope of our study does not permit us to compare across settings (e.g., states), future research can consider how different state and local policy shape refugee women's experiences accessing and utilizing SRH care. For example, research can investigate whether state or local environments directly impact the funding and resources that clinics receive to provide SRH care for refugee women.

The importance of providing interpretation services during healthcare encounters has been noted in previous studies with providers serving refugee women in the U.S. (45, 46). We found a tension between refugee women's preferred usage of informal interpretation assistance and healthcare providers' desire for more formal interpretation services. This discordance points to a need to assess the acceptability of healthcare provision in clinical settings from multiple perspectives, especially with populations with diverse cultural backgrounds. While not specific to the U.S. context and SRH care delivery, a few previous studies in international settings with other health issues have noted similar concerns that providers had with refugee patients' family members or friends serving as interpreters (e.g., safety, confidentiality, or translation accuracy) (92–94). A study with Somali Bantu women in Connecticut also discusses several issues with using the Language Line for translating reproductive healthcare encounters (90), For example, the translators identified Af Maxaa as the “Somali” language as it is spoken by the majority of Somali immigrants. Somali Bantu women, however, use Af Maay, a language that share some similarities in the written form to Af Maxaa but is distinct enough in the spoken form such that the two languages are mutually unintelligible (90). In addition, sometimes the translation is done by a male translator which made women hesitant to discuss SRH (90).

Based on their experiences, providers in our study believed patient navigators can effectively address language-related challenges and that refugee women were comfortable with having patient navigators be their translators in clinical encounters. Moreover, patient navigators were critical in ensuring follow-through on referrals (e.g., helping women overcome issues in the process of going from a FQHC to a public hospital for additional SRH care). In the U.S., the role of patient navigators was historically created in the context of cancer screening, diagnosis, and care. Patient navigators are an asset to the communities they work in and help patients and caregivers comply with evidence-based guidelines for cancer prevention and early detection (95).

Patient navigators facilitate access for underserved populations to healthcare systems and connect them to resources most appropriate for their needs (95). Specific to refugee populations in the U.S., the use of patient navigators or community health workers has been shown to reduce barriers to healthcare access and improved healthcare in the context of cancer screenings and primary care services (96–99). Findings from our study contribute to the literature by highlighting the fact that patient navigators can be helpful outside of the context of cancer screenings and primary care services – specifically, they can be a key facilitator in assisting refugee women with navigating the healthcare system for SRH. As Davidson and colleagues have found in their systematic review, one of the critical barriers refugee women in high-income host countries face is related to navigating and understanding the health system and making appointments for SRH care (31).

These findings call for additional research using an implementation science perspective and exploring organizational and external factors that can help or hinder the adoption of patient navigators for refugee women's SRH care. Existing implementation studies on patient navigation, while not focusing specifically on SRH, have identified several critical factors that should be considered such as planning to ensure alignment with organizational need, integration of the navigator into clinical processes, appropriate caseload, multidisciplinary engagement, funding, and in-kind resources (100, 101). Although the use of patient navigators holds potential for increasing refugee women's SRH care access and utilization, several issues may remain over the large-scale implementation of this model.

For example, given the incredible diversity of refugee patients in Atlanta, it may be challenging to have navigators for each different language or dialect that patients spoke. In addition, while we did not specifically inquire about costs in our study, many patient navigation programs currently lack stable funding and rely on inconsistent sources of payment (102). Given the promise of patient navigation in improving outcomes and reducing disparities, future work can explore scalable implementation strategies and cost-effectiveness of navigation programs for refugee populations (102, 103). Moreover, models using multisectoral partnerships to consolidate resources and coordinate navigation services between different healthcare entities and community-based or nonprofit organizations (e.g., between hospitals, resettlement agencies, and primary care practices) have been shown to be financially sustainable (89).

The strengths of our study include the use of multilevel theoretical frameworks and rigorous qualitative research procedures. We sampled providers with different clinical roles and from different clinical settings; providers in our study also served refugees from diverse backgrounds as opposed to one particular population. Nevertheless, given the heterogeneity of experiences, our study may face limitations in terms of the transferability of results to different settings and contexts (104). Specifically, the context of Georgia (high concentration of refugees, poor healthcare access, and restrictive healthcare policy) may limit the transferability of our results. While the perspectives of providers are critical to understanding organizational contexts, in this manuscript we could not include refugee women's insights on other important factors that have been noted to influence SRH access and utilization (e.g., sociocultural factors, trust, and the refugee experience) (31). Davidson and colleagues' systematic review also noted the significant influence of providers' characteristics and past cultural competence training (31), which will be the focus of additional manuscripts from our study. We acknowledge that the positioning of the researchers in relation to the community of study affected how the research question was formed, who was invited to participate, and the way in which knowledge was constructed and disseminated (105). While we determined an a priori sample size based on previous relevant studies and recommendations for saturation in qualitative research, it is possible that a larger sample size would have enhanced data adequacy (106).

Our study explores healthcare providers’ perspectives of healthcare system-related factors influencing refugee women's access and utilization of SRH services. Findings underscore current constraints of clinics that provided SRH care to refugee women. The provision of transportation services and acceptable interpretation services holds potential for increasing refugee women's SRH care access and utilization. Implementing patient navigation can reduce language-related challenges for refugee women and help women overcome issues to navigate the healthcare system for SRH.

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request and with the approval of Emory University Institutional Review Board. The data are not publicly available as it contains information that could compromise the privacy of research participants. Please contact Dr. Cam Escoffery (cescoff@emory.edu) with any request for data access.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Emory University Institutional Review Board. The patients/participants provided their verbal informed consent to participate in this study.

MV: co-led the conception and study design; co-led the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and led the writing of the manuscript. GB: co-led the conception and study design; co-led the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and reviewed and edited the manuscript. DT: contributed to the analysis and data intepretation and in reviewing and editing the manuscript. CE: contributed to the study design and data interpretation and in reviewing and editing the manuscript. NK: contributed to data interpretation and in reviewing and editing the manuscript. YS: contributed to the study design and in reviewing and editing the manuscript. AB: contributed to the study design and data acquisition and in reviewing and editing the manuscript. DD: contributed to the study design and data acquisition and in reviewing and editing the manuscript. PR: contributed to the study design and in reviewing and editing the manuscript. PA: contributed to the study design and in reviewing and editing the manuscript. CH: contributed to the study design and in reviewing and editing the manuscript. KH: contributed to the study design and data interpretation and in reviewing and editing the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This research was supported by the Mini Grant Program from the Center for Reproductive Health Research in the Southeast (RISE) at Emory University; the Jones Program in Ethics Mini-Grant at Emory University; the Research Development Grant from the Organization for Research on Women and Communication; and the Healthcare Innovation Program Student-Initiated Project Grant at the Georgia Clinical & Translational Science Alliance (CTSA). The Georgia CTSA is supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1TR002378. Dr. Vu was supported by the United States National Cancer Institute (grant no. F31CA243220 and grant no. T32CA193193).

We acknowledge the research assistance that Victoria Huynh provided for this manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. United States Department of State. United States refugee admissions program. Available at: https://www.state.gov/refugee-admissions/ (cited Nov 19, 2021).

2. Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration. Proposed refugee admissions for fiscal year 2018 (2017).

4. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Resettlement and women-at-risk: Can the risk be reduced? Geneva, Switzerland (2013).

5. Casey SE. Evaluations of reproductive health programs in humanitarian settings: a systematic review. Confl Health. (2015) 9(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-9-S1-S1

6. Cottingham J, García-Moreno C, Reis C. Sexual and reproductive health in conflict areas: the imperative to address violence against women. BJOG: Int J Obstet Gynaecol. (2008) 115:301–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01605.x

7. Schweitzer RD, Brough M, Vromans L, Asic-Kobe M. Mental health of newly arrived burmese refugees in Australia: contributions of pre-migration and post-migration experience. Aust New Zeal J Psychiatry. (2011) 45(4):299–307. doi: 10.3109/00048674.2010.543412

8. Metusela C, Ussher J, Perz J, Hawkey A, Morrow M, Narchal R, et al. “In my culture, we don’t know anything about that”: sexual and reproductive health of migrant and refugee women. Int J Behav Med. (2017) 24(6):836–45. doi: 10.1007/s12529-017-9662-3

9. Vangen S, Eskild A, Forsen L. Termination of pregnancy according to immigration status: a population-based registry linkage study. BJOG An Int J Obstet Gynaecol. (2008) 115(10):1309–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01832.x

10. McMichael C. Unplanned but not unwanted? Teen pregnancy and parenthood among young people with refugee backgrounds. J Youth Stud. (2013) 16(5):663–78. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2012.744813

11. Raymond NC, Osman W, O’Brien JM, Ali N, Kia F, Mohamed F, et al. Culturally informed views on cancer screening: a qualitative research study of the differences between older and younger Somali immigrant women. BMC Public Health. (2014) 14:1188. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1188

12. Salad J, Verdonk P, de Boer F, Abma TA. A Somali girl is Muslim and does not have premarital sex. Is vaccination really necessary?” A qualitative study into the perceptions of Somali women in the Netherlands about the prevention of cervical cancer. Int J Equity Health. (2015) 14(1):68. doi: 10.1186/s12939-015-0198-3

13. Aptekman M, Rashid M, Wright V, Dunn S. Unmet contraceptive needs among refugees. Can Fam Physician. (2014) 60(12):e613–9.25642489

14. Haworth RJ, Margalit R, Ross C, Nepal T, Soliman AS. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices for cervical cancer screening among the Bhutanese refugee community in Omaha, Nebraska. J Community Health. (2014) 39(5):872–8. doi: 10.1007/s10900-014-9906-y

15. Ozel S, Yaman S, Kansu-Celik H, Hancerliogullari N, Balci N, Engin-Ustun Y. Obstetric outcomes among Syrian refugees: a comparative study at a tertiary care maternity hospital in Turkey. Rev Bras Ginecol e Obs/RBGO Gynecol Obstet. (2018) 40(11):673–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1673427

16. Asif S, Baugh A, Jones NW. The obstetric care of asylum seekers and refugee women in the UK. Obstet Gynaecol. (2015) 17(4):223–31. doi: 10.1111/tog.12224

17. Kandasamy T, Cherniak R, Shah R, Yudin MH, Spitzer R. Obstetric risks and outcomes of refugee women at a single centre in Toronto. J Obstet Gynaecol Canada. (2014) 36(4):296–302. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(15)30604-6

18. Wanigaratne S, Cole DC, Bassil K, Hyman I, Moineddin R, Urquia ML. The influence of refugee status and secondary migration on preterm birth. J Epidemiol Community Health. (2016) 70(6):622–8. doi: 10.1136/jech-2015-206529

19. Carolan M. Pregnancy health status of sub-Saharan refugee women who have resettled in developed countries: a review of the literature. Midwifery. (2010) 26(4):407–14. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2008.11.002

20. Dyer JM, Baksh L. A study of pregnancy and birth outcomes among african-born women living in Utah. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute (2016).

21. Gagnon AJ, Merry L, Robinson C. A systematic review of refugee women's reproductive health. Refuge. (2002) 21(1):6–17. doi: 10.25071/1920-7336.21279

22. Gagnon AJ, Zimbeck M, Zeitlin J. Migration to western industrialised countries and perinatal health: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med. (2009) 69(6):934–46. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.06.027

23. Ngum Chi Watts MC, Liamputtong P, Carolan M. Contraception knowledge and attitudes: truths and myths among African Australian teenage mothers in greater Melbourne, Australia. J Clin Nurs. (2014) 23(15–16):2131–41. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12335

24. Ngum Chi Watts MC, McMichael C, Liamputtong P. Factors influencing contraception awareness and use: the experiences of young African Australian mothers. J Refug Stud. (2015) 28(3):368–87. doi: 10.1093/jrs/feu040

25. Barnes DM, Harrison CL. Refugee women’s reproductive health in early resettlement. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. (2004) 33(6):723–8. doi: 10.1177/0884217504270668

26. McComb E, Ramsden V, Olatunbosun O, Williams-Roberts H. Knowledge, attitudes and barriers to human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine uptake among an immigrant and refugee catch-up group in a Western Canadian province. J Immigr Minor Heal. (2018) 20(6):1424–8. doi: 10.1007/s10903-018-0709-6

27. Eluka NN, Morrison SD, Sienkiewicz HS. “The wheel of my work”: community health worker perspectives and experiences with facilitating refugee access to primary care services. Heal Equity. (2021) 5(1):253–60. doi: 10.1089/heq.2020.0150

28. Feldman R. Primary health care for refugees and asylum seekers: a review of the literature and a framework for services. Public Health. (2006) 120(9):809–16. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2006.05.014

29. Mengesha ZB, Perz J, Dune T, Ussher J. Challenges in the provision of sexual and reproductive health care to refugee and migrant women: a Q methodological study of health professional perspectives. J Immigr Minor Heal. (2018) 20(2):307–16. doi: 10.1007/s10903-017-0611-7

30. Liu C, Watts B, Litaker D. Access to and utilization of healthcare: the provider’s role. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. (2006) 6(6):653–60. doi: 10.1586/14737167.6.6.653

31. Davidson N, Hammarberg K, Romero L, Fisher J. Access to preventive sexual and reproductive health care for women from refugee-like backgrounds: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. (2022) 22(1):403. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-12576-4

32. Edward J, Hines-Martin V. Exploring the providers perspective of health and social service availability for immigrants and refugees in a Southern Urban community. J Immigr Minor Heal. (2015) 17(4):1185–91. doi: 10.1007/s10903-014-0048-1

33. National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. Achieving behavioral health equity for children, families, and communities. In: Tracey SM, Kellogg E, Sanchez CE, Keenan W, editors. Achieving behavioral health equity for children, families, and communities. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press (2019). p. 1–126.

34. Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. (2009) 4(1):50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50

35. Riggs E, Davis E, Gibbs L, Block K, Szwarc J, Casey S, et al. Accessing maternal and child health services in Melbourne, Australia: reflections from refugee families and service providers. BMC Health Serv Res. (2012) 12(1):117. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-117

36. Newaz S. User and provider perspectives on improving mental healthcare for Syrian refugee women in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. J Refug Glob Heal. (2020) 3(1):1–17. doi: 10.18297/rgh/vol3/iss1/7

37. Mengesha ZB, Perz J, Dune T, Ussher J. Refugee and migrant women’s engagement with sexual and reproductive health care in Australia: a socio-ecological analysis of health care professional perspectives. PLoS ONE. (2017) 12(7):e0181421. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181421

38. Ng C, Newbold KB. Health care providers’ perspectives on the provision of prenatal care to immigrants. Cult Health Sex. (2011) 13(5):561–74. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2011.555927

39. Cheyne-Hazineh L. Creating new possibilities: service provider perspectives on the settlement and integration of Syrian refugee youth in a Canadian community. Can Ethn Stud. (2020) 52(2):115–37. doi: 10.1353/ces.2020.0008

40. Mahimbo A, Seale H, Smith M, Heywood A. Challenges in immunisation service delivery for refugees in Australia: a health system perspective. Vaccine. (2017) 35(38):5148–55. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.08.002

41. Salami B, Salma J, Hegadoren K. Access and utilization of mental health services for immigrants and refugees: perspectives of immigrant service providers. Int J Ment Health Nurs. (2019) 28(1):152–61. doi: 10.1111/inm.12512

42. Mengesha ZB, Perz J, Dune T, Ussher J. Talking about sexual and reproductive health through interpreters: the experiences of health care professionals consulting refugee and migrant women. Sex Reprod Healthc. (2018) 16:199–205. doi: 10.1016/j.srhc.2018.03.007

43. Winn A, Hetherington E, Tough S. Caring for pregnant refugee women in a turbulent policy landscape: perspectives of health care professionals in Calgary, Alberta. Int J Equity Health. (2018) 17(1):91. doi: 10.1186/s12939-018-0801-5

44. El Sount CR-O, Denkinger JK, Windthorst P, Nikendei C, Kindermann D, Renner V, et al. Psychological burden in female, Iraqi refugees who suffered extreme violence by the “Islamic state”: the perspective of care providers. Front Psychiatry. (2018) 9:562. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00562

45. Zhang Y, Ornelas IJ, Do HH, Magarati M, Jackson JC, Taylor VM. Provider perspectives on promoting cervical cancer screening among refugee women. J Community Health. (2017) 42(3):583–90. doi: 10.1007/s10900-016-0292-5

46. LaMancuso K, Goldman RE, Nothnagle M. “Can I ask that?”: perspectives on perinatal care after resettlement among Karen refugee women, medical providers, and community-based doulas. J Immigr Minor Heal. (2016) 18(2):428–35. doi: 10.1007/s10903-015-0172-6

47. Khuu BP, Lee HY, Zhou AQ, Shin J, Lee RM. Healthcare providers’ perspectives on parental health literacy and child health outcomes among Southeast Asian American immigrants and refugees. Child Youth Serv Rev. (2016) 67:220–9. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.06.006

48. Lazar JN, Johnson-Agbakwu CE, Davis OI, Shipp MP-L. Providers’ perceptions of challenges in obstetrical care for Somali women. Obstet Gynecol Int. (2013) 2013:1–12. doi: 10.1155/2013/149640

49. Castañeda H, Holmes SM, Madrigal DS, Young M-ED, Beyeler N, Quesada J. Immigration as a social determinant of health. Annu Rev Public Health. (2015) 36(1):375–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182419

50. Kumar GS, Beeler JA, Seagle EE, Jentes ES. Long-term physical health outcomes of resettled refugee populations in the United States: a scoping review. J Immigr Minor Heal. (2021) 23(4):813–23. doi: 10.1007/s10903-021-01146-2

51. Campbell RM, Klei AG, Hodges BD, Fisman D, Kitto S. A comparison of health access between permanent residents, undocumented immigrants and refugee claimants in Toronto, Canada. J Immigr Minor Heal. (2014) 16(1):165–76. doi: 10.1007/s10903-012-9740-1

52. Creswell JW, Poth CN. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. 4th Eds Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA (2018). 1–488.

54. Kim AJ, Bozarth A. Refuge city: creating places of welcome in the Suburban U.S. South. J Urban Aff. (2021) 43(6):851–71. doi: 10.1080/07352166.2020.1718506

55. Burton J. Atlanta: Resettled refugees and the American South. 2015 Humanity in Action Philanthropy and Social Enterprise Fellowship (2015).

56. Carlisle L. Refugee Resurgens: Asian Immigration in Atlanta. Atlanta History Center (2021). Available at: https://www.atlantahistorycenter.com/blog/refugee-resurgens-asian-immigration-in-atlanta/ (cited Feb 7, 2022).

58. Long K. This small town in America’s deep south welcomes 1,500 refugees a year. Clarkston, GA: The Guardian (2017). https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/may/24/clarkston-georgia-refugee-resettlement-program

60. Muñoz C. World refugee day and immigrant heritage month: How welcoming is Georgia? (2022). Available at: https://gbpi.org/world-refugee-day-and-immigrant-heritage-month-reflection/ (cited Jun 27, 2022).

62. Hart A. Georgia adds 36,000 to uninsured rolls, ranks third worst in U.S. AJC. (2019). https://www.ajc.com/news/state--regional-govt--politics/georgia-adds-000-uninsured-rolls-ranks-thirdworst/dBiv1qGR4qb7Ono1gUukrL/

63. Kaiser Family Foundation. Status of state medicaid expansion decisions: Interactive Map (2022). Available at: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/status-of-state-medicaid-expansion-decisions-interactive-map/ (cited Nov 9, 2022).

64. Hennink MM, Kaiser BN, Marconi VC. Code saturation versus meaning saturation. Qual Health Res. (2017) 27(4):591–608. doi: 10.1177/1049732316665344

65. McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. (1988) 15:351–77. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401

66. Penchansky R, Thomas JW. The concept of access: definition and relationship to consumer satisfaction. Med Care. (1981) 19(2):127–40. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198102000-00001

67. Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, Moules NJ. Thematic analysis. Int J Qual Methods. (2017) 16(1):160940691773384. doi: 10.1177/1609406917733847

68. Thomas DR. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am J Eval. (2006) 27(2):237–46. doi: 10.1177/1098214005283748

69. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. (2006) 3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

70. Maxwell JA. Qualitative research design, an interactive approach. 3rd ed Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Inc. (2012). 1–232.

71. Sandelowski M. Real qualitative researchers do not count: the use of numbers in qualitative research. Res Nurs Health. (2001) 24(3):230–40. doi: 10.1002/nur.1025

72. Creswell JW, Miller DL. Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory Pract. (2000) 39(3):124–30. doi: 10.1207/s15430421tip3903_2

73. Whittemore R, Chase SK, Mandle CL. Validity in qualitative research. Qual Health Res. (2001) 11(4):522–37. doi: 10.1177/104973201129119299

74. Golafshani N. Understanding reliability and validity in qualitative research. Qual. Res. J. (2003) 8(4):597–606. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2003.1870

77. Starbird LE, DiMaina C, Sun C-A, Han H-R. A systematic review of interventions to minimize transportation barriers among people with chronic diseases. J Community Health. (2019) 44(2):400–11. doi: 10.1007/s10900-018-0572-3

78. Syed ST, Gerber BS, Sharp LK. Traveling towards disease: transportation barriers to health care access. J Community Health. (2013) 38(5):976–93. doi: 10.1007/s10900-013-9681-1

79. Holcomb DS, Pengetnze Y, Steele A, Karam A, Spong C, Nelson DB. Geographic barriers to prenatal care access and their consequences. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. (2021) 3(5):100442. doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2021.100442

80. Heaman MI, Sword W, Elliott L, Moffatt M, Helewa ME, Morris H, et al. Barriers and facilitators related to use of prenatal care by inner-city women: perceptions of health care providers. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2015) 15(1):2. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0431-5

81. Hansen A, Moloney ME, Cockerham-Morris C, Li J, Chavan NR. Preterm birth prevention in Appalachian Kentucky: understanding barriers and facilitators related to transvaginal ultrasound cervical length surveillance among prenatal care providers. Women’s Heal Reports. (2020) 1(1):293–300. doi: 10.1089/whr.2019.0023

82. Ayers BL, Hawley NL, Purvis RS, Moore SJ, McElfish PA. Providers’ perspectives of barriers experienced in maternal health care among Marshallese women. Women Birth. (2018) 31(5):e294–301. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2017.10.006

83. Williams KM, Tremblay N. Improving transportation access to health care services. Tampa, FL: National Center for Transit Research (2019).

84. Health Research & Educational Trust. Social determinants of health series: transportation and the role of hospitals. Chicago, IL: Health Research & Educational Trust (2017).

85. Powers BW, Rinefort S, Jain SH. Nonemergency medical transportation. JAMA. (2016) 316(9):921. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.9970

86. Vais S, Siu J, Maru S, Abbott J, St. Hill I, Achilike C, et al. Rides for refugees: a transportation assistance pilot for women’s health. J Immigr Minor Heal. (2020) 22(1):74–81. doi: 10.1007/s10903-019-00946-x

87. Khan A, DeYoung SE. Maternal health services for refugee populations: exploration of best practices. Glob Public Health. (2019) 14(3):362–74. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2018.1516796

88. Philbrick AM, Wicks CM, Harris IM, Shaft GM, Van Vooren JS. Make refugee health care great [again]. Am J Public Health. (2017) 107(5):656–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303740

89. New York State Health Foundation. Opening doors: A sustainable refugee health care model (2016).

90. Gurnah K, Khoshnood K, Bradley E, Yuan C. Lost in translation: reproductive health care experiences of Somali Bantu women in hartford, Connecticut. J Midwifery Womens Health. (2011) 56(4):340–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-2011.2011.00028.x

91. Guttmacher Institute. State facts about abortion: Georgia (2022) . Available at: https://www.guttmacher.org/fact-sheet/state-facts-about-abortion-georgia (cited Nov 9, 2022).

92. Farley R, Askew D, Kay M. Caring for refugees in general practice: perspectives from the coalface. Aust J Prim Health. (2014) 20(1):85. doi: 10.1071/PY12068

93. Jensen NK, Norredam M, Priebe S, Krasnik A. How do general practitioners experience providing care to refugees with mental health problems? A qualitative study from Denmark. BMC Fam Pract. (2013) 14(1):17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-14-17

94. MacFarlane A, Glynn LG, Mosinkie PI, Murphy AW. Responses to language barriers in consultations with refugees and asylum seekers: a telephone survey of Irish general practitioners. BMC Fam Pract. (2008) 9(1):68. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-9-68

95. Natale-Pereira A, Enard KR, Nevarez L, Jones LA. The role of patient navigators in eliminating health disparities. Cancer. (2011) 117(S15):3541–50. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26264

96. Percac-Lima S, Ashburner JM, Bond B, Oo SA, Atlas SJ. Decreasing disparities in breast cancer screening in refugee women using culturally tailored patient navigation. J Gen Intern Med. (2013) 28(11):1463–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2491-4

97. Raines Milenkov A, Felini M, Baker E, Acharya R, Longanga Diese E, Onsa S, et al. Uptake of cancer screenings among a multiethnic refugee population in North Texas, 2014–2018. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15(3):e0230675. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0230675

98. Yun K, Paul P, Subedi P, Kuikel L, Nguyen GT, Barg FK. Help-seeking behavior and health care navigation by Bhutanese refugees. J Community Health. (2016) 41(3):526–34. doi: 10.1007/s10900-015-0126-x

99. Rodriguez-Torres SA, McCarthy AM, He W, Ashburner JM, Percac-Lima S. Long-term impact of a culturally tailored patient navigation program on disparities in breast cancer screening in refugee women after the program’s end. Heal Equity. (2019) 3(1):205–10. doi: 10.1089/heq.2018.0104

100. Freund KM. Implementation of evidence-based patient navigation programs. Acta Oncol. (2017) 56(2):123–7. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2016.1266078

101. Kokorelias KM, Shiers-Hanley JE, Rios J, Knoepfli A, Hitzig SL. Factors influencing the implementation of patient navigation programs for adults with complex needs: a scoping review of the literature. Heal Serv Insights. (2021) 14:117863292110332. doi: 10.1177/11786329211033267

102. Schmit CD, Washburn DJ, LaFleur M, Martinez D, Thompson E, Callaghan T. Community health worker sustainability: funding, payment, and reimbursement laws in the United States. Public Health Rep. (2021) 137(3):003335492110060. doi: 10.1177/00333549211006072

103. McKenney KM, Martinez NG, Yee LM. Patient navigation across the spectrum of women’s health care in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. (2018) 218(3):280–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.08.009

104. Barnes J, Conrad K, Demont-Heinrich C, Graziano M, Kowalski D, Neufeld J, et al. Generalizability and Transferability. Writing@CSU. (2012). Available from: https://writing.colostate.edu/guides/pdfs/guide65.pdf (cited Oct 6, 2021).

105. Rowe WE. Positionality. In: Coghlan D, Brydon-Miller M, editors. The SAGE encyclopedia of action research. 1 Oliver’s yard, 55 city road, London EC1Y 1SP. United Kingdom: SAGE Publications Ltd (2014). p. 627–8.

Keywords: refugee women, healthcare providers, transportation services, interpretation services, patient navigators, sexual and reproduction health, healthcare system, implementation science

Citation: Vu M, Besera G, Ta D, Escoffery C, Kandula NR, Srivanjarean Y, Burks AJ, Dimacali D, Rizal P, Alay P, Htun C and Hall KS (2022) System-level factors influencing refugee women's access and utilization of sexual and reproductive health services: A qualitative study of providers’ perspectives. Front. Glob. Womens Health 3:1048700. doi: 10.3389/fgwh.2022.1048700

Received: 29 September 2022; Accepted: 18 November 2022;

Published: 14 December 2022.

Edited by:

Jane Freedman, Université Paris 8, FranceReviewed by:

Kelly Melekis, Skidmore College, United States© 2022 Vu, Besera, Ta, Escoffery, Kandula, Srivanjarean, Burks, Dimacali, Rizal, Alay, Htun and Hall. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Milkie Vu bWlsa2llLnZ1QG5vcnRod2VzdGVybi5lZHU=

Specialty Section: This article was submitted to Maternal Health, a section of the journal Frontiers in Global Women's Health

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.