- 1Laboratory for Experimental Cardiology, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht University, Utrecht, Netherlands

- 2Julius Center for Health Sciences and Primary Care, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht University, Utrecht, Netherlands

- 3Imperial College London, The George Institute for Global Health, London, United Kingdom

Introduction: Pharmacological treatment is an important component of secondary prevention in acute coronary syndrome (ACS) survivors. However, adherence to medication regimens is often suboptimal, reducing the effectiveness of treatment. It has been suggested that sex influences adherence to cardiovascular medication, but results differ across studies, and a systematic overview is lacking.

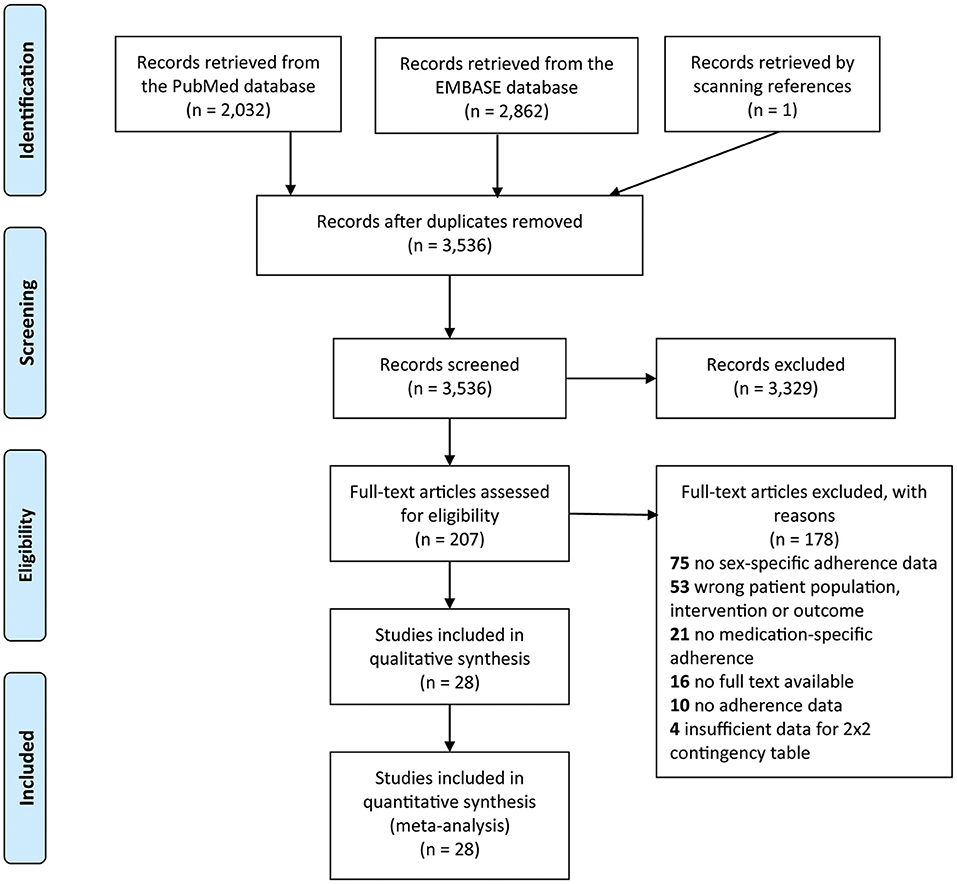

Methods: We performed a systematic search of PubMed and EMBASE on 16 October 2019. Studies that reported sex-specific adherence for one or more specific medication classes for ACS patients were included. Odds ratios, or equivalent, were extracted per medication class and combined using a random effects model.

Results: In total, we included 28 studies of which some had adherence data for more than one medication group. There were 7 studies for angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) (n = 100,909, 37% women), 8 studies for antiplatelet medication (n = 37,804, 27% women), 11 studies for beta-blockers (n = 191,339, 38% women), and 17 studies for lipid-lowering medication (n = 318,837, 35% women). Women were less adherent to lipid-lowering medication than men (OR = 0.87, 95% CI 0.82–0.92), but this sex difference was not observed for antiplatelet medication (OR = 0.95, 95% CI 0.83–1.09), ACEIs/ARBs (OR = 0.95, 95% CI 0.78–1.17), or beta-blockers (OR = 0.97, 95% CI 0.86–1.11).

Conclusion: Women with ACS have poorer adherence to lipid-lowering medication than men with the same condition. There are no differences in adherence to antiplatelet medication, ACEIs/ARBs, and beta-blockers between women and men with ACS.

Introduction

Patients who survive an acute coronary syndrome (ACS) are at high risk of recurrent events (1–3). Secondary prevention through pharmacological therapy reduces the risk of recurrent events and mortality in this population (1, 2), but its effectiveness is attenuated by suboptimal patient adherence (4, 5). Poor adherence to medication regimens is an important obstacle in improving outcomes for ACS patients and has proven difficult to solve (6). Two large meta-analyses evaluating adherence to cardiovascular medication found that patient sex was an important factor in predicting adherence (7, 8). However, these meta-analyses did not investigate which sex was at higher risk of non-adherence.

There is some evidence on adherence to, for example, statins that suggests women have poorer adherence because they experience more adverse drug reactions (9), but a structured overview of the literature is still lacking. We performed a systematic review with meta-analyses on sex differences in adherence to cardiovascular medication in patients with ACS. We hypothesize that women, in general, have poorer adherence than men.

Methods

Terminology

It is important to recognize that sex and gender describe two different concepts. Sex refers to the biological differences between females and males, whereas gender refers to social differences between women and men. Both play an important role in health and disease, although through different mechanisms (10). This manuscript evaluates sex differences, meaning the linguistically correct terms to use would be “female” and “male.” However, all studies included in our review used the terms “women” and “men” to refer to patient sex, as is common in medical literature. We therefore also use the terms “women” and “men” to refer to patients of the female and male sex, respectively.

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

We searched both PubMed and EMBASE on 16 October 2019 using a pre-defined search term consisting of both text words and MeSH headings (Supplementary Files). The text words were limited to title and abstract only. The retrieved articles were screened by two independent reviewers who also resolved any conflicts that arose with help of a third reviewer, if necessary. The reference lists of relevant articles were screened for any additional articles. A modified version of the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale was used to assess the quality of included studies (Supplementary Files).

Only original research articles written in English that evaluated adherence at the individual patient-level were eligible for inclusion. Articles were included if they reported sex-specific data on medication adherence in patients with ACS, defined as either myocardial infarction or unstable angina (11). We excluded studies with too few participants to evaluate sex differences (n < 100), studies where ACS was included alongside other cardiovascular diseases and results could not be separated based on disease subgroup, and studies that included only men or only women. We also excluded studies that evaluated adherence to a combination of medications instead of per specific medication group. Finally, we excluded all studies for which the full text could not be retrieved.

We extracted population size, the percentage of women, mean age, total duration of follow-up, and measure of adherence used from all included studies. In addition, we extracted the number of adherent and non-adherent women and men or, if unavailable, unadjusted relative risk estimates (or equivalent). We also extracted adjusted relative risk estimates when available.

Statistical Analysis

The meta-analysis was conducted conforming with the Meta-Analyses and Systematic Reviews of Observational studies (MOOSE) guidelines (12). We chose “good adherence,” as defined by each study, as our outcome and men as the reference category to facilitate interpretation of the results. We pooled the sex-specific odds ratios (ORs) using random effects meta-analysis because the included studies applied varying definitions of adherence and thus the estimated effect of sex on adherence can vary across these studies. In these situations, it is recommended to apply random effects meta-analysis instead of fixed effects meta-analyses (13).

We calculated the average sex-specific adherence across studies weighted by study size. We calculated unadjusted ORs for studies that presented number of adherent and non-adherent women and men. We converted the risk estimates from studies that used either a different outcome (poor adherence) or reference category (women) to fit our analysis. When studies stratified their analysis by subgroups, we pooled reported risk estimates using fixed effects meta-analysis and included the pooled risk estimate in our overall meta-analysis. We performed an additional analysis using only adjusted ORs to see whether adjustment would affect our crude estimates. We created funnel plots to check for publication bias.

All analyses were performed in R (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria). A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study Characteristics

In total, we included 28 studies of which some had adherence data for more than one medication group (Figure 1). The medication groups included were angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ACEIs/ARBs), antiplatelet therapy, beta-blockers, and lipid-lowering medication. Nine studies were of high quality (4 stars), 17 studies were of moderate quality (2 or 3 stars), and two studies were of poor quality (0 or 1 star). A complete overview of the included studies can be found in Table 1.

Sex-Specific Adherence

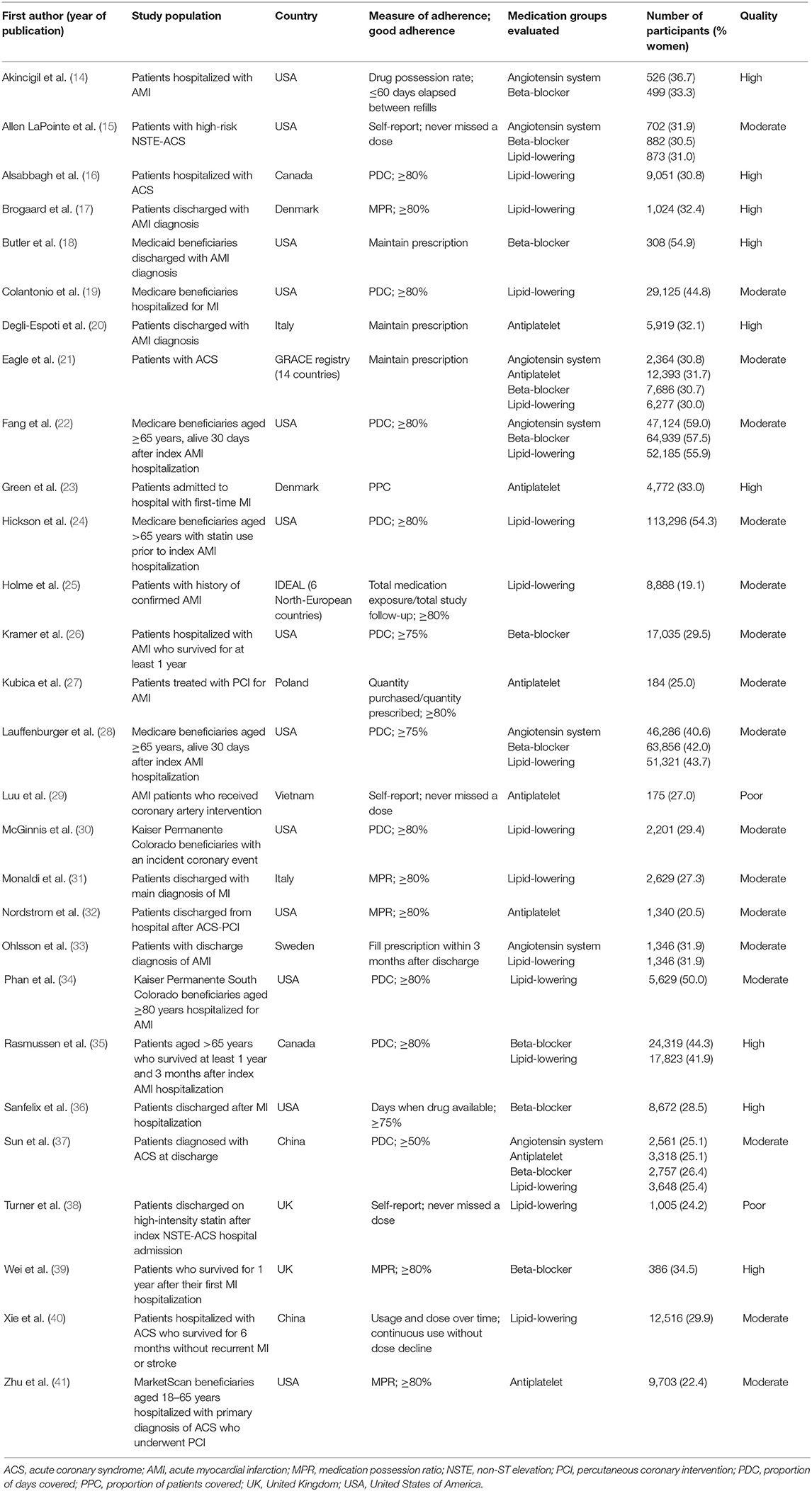

In the crude analyses, we included 7 studies with adherence information for ACEIs/ARBs (n = 100,909, 37% women), 8 for antiplatelet medication (n = 37,804, 27% women), 11 for beta-blockers (n = 191,339, 38% women), and 17 for lipid-lowering medication (n = 318,837, 35% women). Across all included studies, 62.7% of women and 63.9% of men had good ACEIs/ARBs adherence. These percentages were 64.5 and 66.0% for antiplatelet medication, 60.8 and 61.0% for beta-blockers, and 73.6 and 75.3% for lipid-lowering medication, respectively.

There was no significant sex difference in adherence for ACEIs/ARBs (OR = 0.95, 95% CI 0.78–1.17; Figure 2A), antiplatelet medication (OR = 0.95, 95% CI 0.83–1.09; Figure 2B), and beta-blockers (OR = 0.97, 95% CI 0.86–1.11; Figure 2C). However, women had significantly poorer adherence to lipid-lowering medications than men (OR = 0.87, 95% CI 0.82–0.92; Figure 2D).

Figure 2. Meta-analysis of unadjusted odds ratios per medication category. (A) Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers. (B) Anti-platelet medication. (C) Beta-blockers. (D) Lipid-lowering medication.

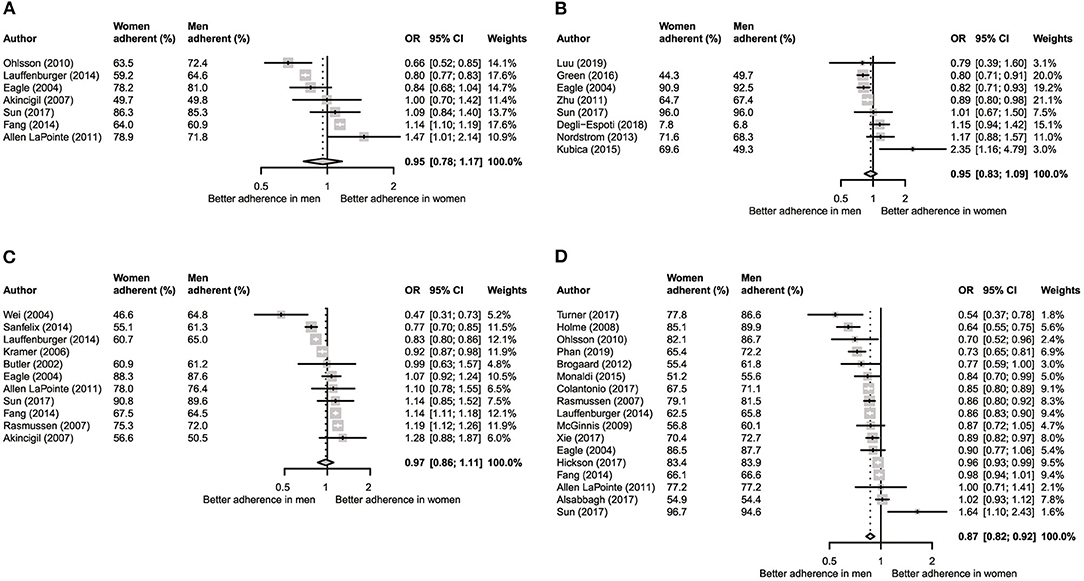

In the adjusted analyses, we included three studies for ACEIs/ARBs and beta-blockers and six studies for lipid-lowering medication. There was only one study with adjusted risk estimates for antiplatelet medication. These analyses showed a significantly poorer adherence in women for ACEIs/ARBs (OR = 0.88, 95% CI 0.80–0.96) and beta-blockers (OR = 0.91, 95% CI 0.88–0.93) but not for lipid-lowering medication (OR = 0.97, 95% CI 0.89–1.05) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Meta-analysis of adjusted odds ratios per medication category. (A) Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers. (B) Anti-platelet medication. (C) Beta-blockers. (D) Lipid-lowering medication.

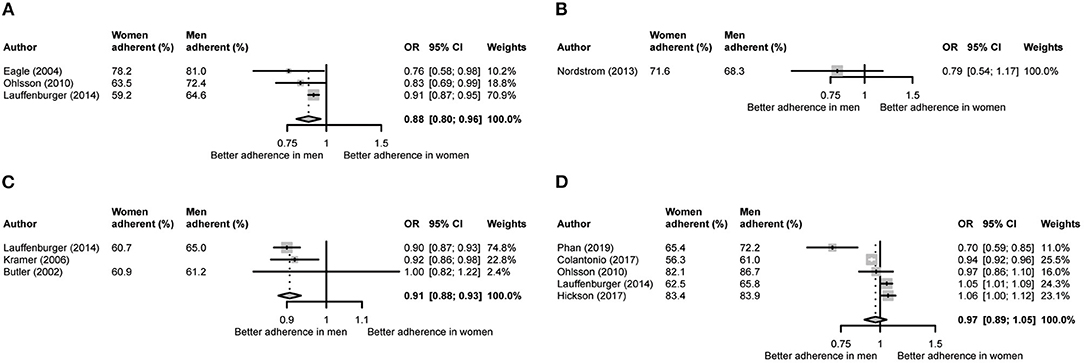

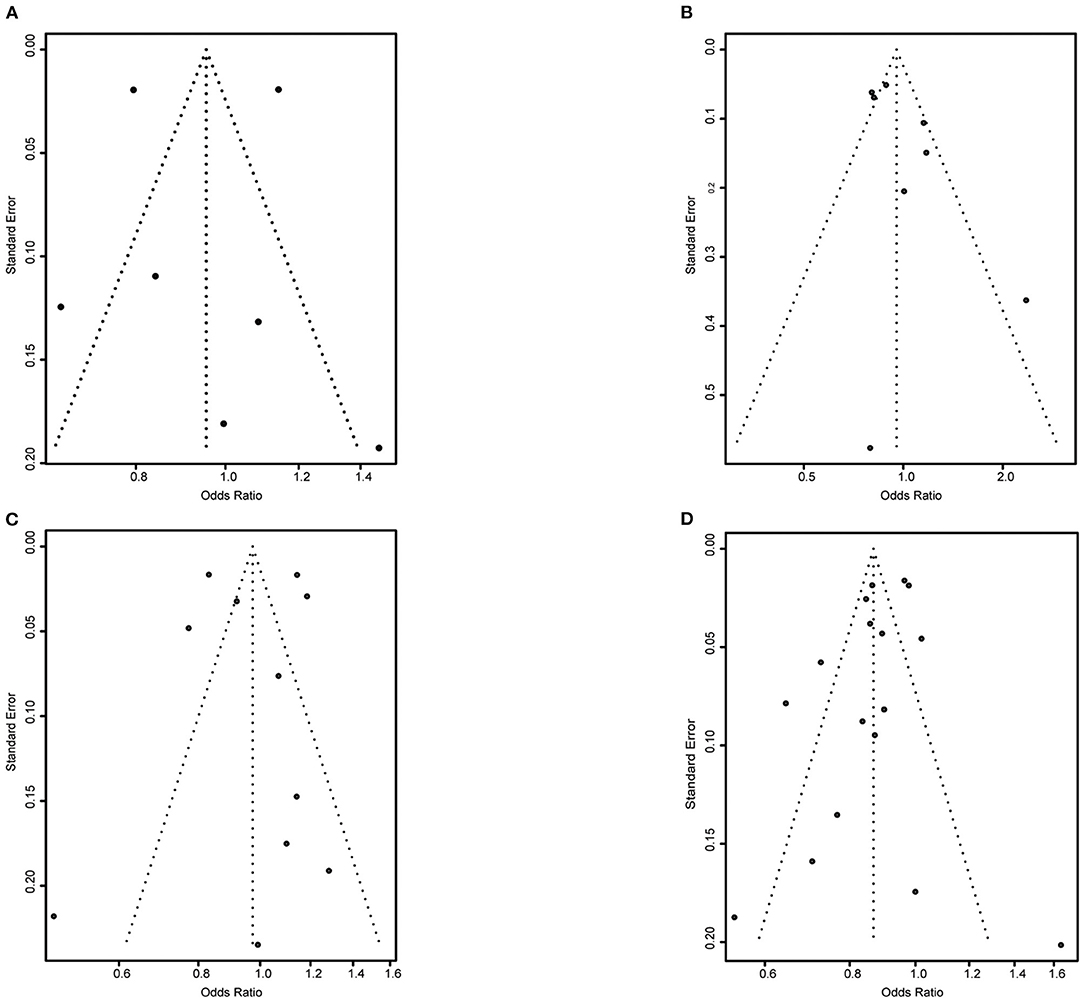

The funnel plots for ACEIs/ARBs and lipid-lowering medication were relatively balanced, suggesting little publication bias. For antiplatelet medication and beta-blockers, however, smaller studies showing poorer adherence in women seemed to be lacking compared with the number of such studies showing poorer adherence in men (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Funnel plot for each medication category. (A) Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers. (B) Anti-platelet medication. (C) Beta-blockers. (D) Lipid-lowering medication.

Discussion

Adherence to ACEIs/ARBs, antiplatelet medication, beta-blockers, and lipid-lowering medication lies between 60 and 70% in both women and men surviving an ACS. Women had poorer adherence than men for lipid-lowering medication but not for the other medication groups, where adherence was similar between the sexes.

A previous systematic review on adherence to cardiovascular medication in coronary heart disease patients also found adherence to be 60–70% (42), suggesting that adherence is reasonable in secondary prevention of ACS. However, they did not find any sex differences (42), whereas our results suggest that those may be present at least for lipid-lowering drugs. This finding is supported by previous work showing that women have poorer adherence to statins in both primary and secondary prevention (43). This may be due to biological or social reasons, or a combination of both. There are known biological differences in drug metabolism between women and men (44), which may increase the risk of statin-related adverse drug reactions in women (45). This may also be true for the other medication groups included in our review, but the lack of sex-specific data on medication efficacy, safety, and metabolism prevents researchers from drawing sound conclusions on this topic (46–48). Gender differences may also play a role in adherence, with women for example more often refusing or discontinuing statins because they do not believe the medication is safe (49). Given that women derive equal benefit from statin therapy as men (50), it is important to improve statin adherence in women through both collecting more high-quality sex-specific data on this topic and adapting treatment to individual patients by for example using lower dosages to reduce the risk of side effects (45).

The main strength of this review is that it combines data from 28 studies. However, it is limited by the quality of the available data. The majority of studies included in this review were of moderate quality, and the data were heterogeneous on several important points. Both the chosen measure of adherence and the definition of “good adherence” varied greatly across studies. Approximately half of the included studies used a standardized measure of adherence, such as the medication possession ratio (18% of studies) or proportion of days covered (36%), but others used either self-report (11%) or another, sometimes self-devised, measure (35%). This makes meta-analyzing such data and interpreting the results difficult. To alleviate this issue, it is important that future studies use both standardized measures of adherence and standardized cut-off values to denote good and poor adherence. We also saw that smaller studies showing poorer adherence in women were less likely to be published, and that studies showing poorer adherence in women more often provided adjusted risk estimates. This differential approach may introduce bias in meta-analyses such as ours and complicate the interpretation of our findings.

In conclusion, we show that adherence to cardiovascular medication is reasonable in women and men surviving an ACS. Women had poorer adherence to lipid-lowering medication than men, but this difference was not observed for the other cardiovascular medication groups. However, a standardized approach to the measurement and evaluation of adherence is needed to improve the quality of research performed in this field.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

SB and JI performed the systematic search. SB analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. SP conceived the project, supported data analyses, and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

SP was supported by a UK Medical Research Council Skills Development Fellowship (MR/P014550/1).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgwh.2021.637398/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Gallone G, Baldetti L, Pagnesi M, Latib A, Colombo A, Libby P, et al. Medical therapy for long-term prevention of atherothrombosis following an acute coronary syndrome: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am College Cardiol. (2018) 72:2886–903. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.09.052

2. Hoedemaker NPG, Damman P, Ottervanger JP, Dambrink JHE, Gosselink ATM, Kedhi E, et al. Trends in optimal medical therapy prescription and mortality after admission for acute coronary syndrome: a 9-year experience in a real-world setting. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. (2018) 4:102–10. doi: 10.1093/ehjcvp/pvy005

3. Makki N, Brennan TM, and Girotra S. Acute coronary syndrome. J Intensive Care Med. (2013) 30:186–200. doi: 10.1177/0885066613503294

4. Ho PM, Spertus JA, Masoudi FA, Reid KJ, Peterson ED, Magid DJ, et al. Impact of medication therapy discontinuation on mortality after myocardial infarction. Arch Internal Med. (2006) 166:1842. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1842

5. Jackevicius CA, Li P, and Tu JV. Prevalence, predictors, and outcomes of primary nonadherence after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. (2008) 117:1028–36. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.706820

6. Armstrong PW, and McAlister FA. Searching for adherence: can we fulfill the promise of evidence-based medicines?*. J Am College Cardiol. (2016) 68:802–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.06.006

7. Kardas P, Lewek P, and Matyjaszczyk M. Determinants of patient adherence: a review of systematic reviews. Front Pharmacol. (2013) 4:91. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2013.00091

8. Chowdhury R, Khan H, Heydon E, Shroufi A, Fahimi S, Moore C, et al. Adherence to cardiovascular therapy: a meta-analysis of prevalence and clinical consequences. Euro Heart J. (2013) 34:2940–8. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht295

9. Karalis DG, Wild RA, Maki KC, Gaskins R, Jacobson TA, Sponseller CA, et al. Gender differences in side effects and attitudes regarding statin use in the Understanding Statin Use in America and Gaps in Patient Education (USAGE) study. J Clin Lipidol. (2016) 10:833–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2016.02.016

10. Heise L, Greene ME, Opper N, Stavropoulou M, Harper C, Nascimento M, et al. Gender inequality and restrictive gender norms: framing the challenges to health. Lancet. (2019) 393:2440–54. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30652-X

11. Thygesen KA, and Alpert JS. The definitions of acute coronary syndrome, myocardial infarction, and unstable angina. Curr Cardiol Rep. (2001) 3:268–72. doi: 10.1007/s11886-001-0079-9

12. Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. (2000) 283:2008–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008

13. Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, and Rothstein HR. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res Synthesis Methods. (2010) 1:97–111. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.12

14. Akincigil A, Bowblis JR, Levin C, Jan S, Patel M, and Crystal S. Long-term adherence to evidence based secondary prevention therapies after acute myocardial infarction. J Gen Intern Med. (2008) 23:115–21. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0351-9

15. Allen LaPointe NM, Ou FS, Calvert SB, Melloni C, Stafford JA, Harding T, et al. Association between patient beliefs and medication adherence following hospitalization for acute coronary syndrome. Am Heart J. (2011) 161:855–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.02.009

16. Alsabbagh MW, Eurich D, Lix LM, Wilson TW, and Blackburn DF. Does the association between adherence to statin medications and mortality depend on measurement approach? A retrospective cohort study. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2017) 17:66. doi: 10.1186/s12874-017-0339-z

17. Brogaard HV, Køhn MG, Berget OS, Hansen HS, Gerke O, Mickley H, et al. Significant improvement in statin adherence and cholesterol levels after acute myocardial infarction. Dan Med J. (2012) 59:A4509.

18. Butler J, Arbogast PG, BeLue R, Daugherty J, Jain MK, Ray WA, et al. Outpatient adherence to beta-blocker therapy after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2002) 40:1589–95. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(02)02379-3

19. Colantonio LD, Huang L, Monda KL, Bittner V, Serban M-C, Taylor B, et al. Adherence to high-intensity statins following a myocardial infarction hospitalization among medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Cardiol. (2017) 2:890–895. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.0911

20. Degli Esposti L, Perrone V, Veronesi C, Buda S, and Rossini R. Long-term use of antiplatelet therapy in real-world patients with acute myocardial infarction: insights from the PIPER study. TH Open. (2018) 2:e437–44. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1676529

21. Eagle KA, Kline-Rogers E, Goodman SG, Gurfinkel EP, Avezum A, Flather MD, et al. Adherence to evidence-based therapies after discharge for acute coronary syndromes: an ongoing prospective, observational study. Am J Med. (2004) 117:73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.12.041

22. Fang G, Robinson JG, Lauffenburger J, Roth MT, and Brookhart MA. Prevalent but moderate variation across small geographic regions in patient nonadherence to evidence-based preventive therapies in older adults after acute myocardial infarction. Med Care. (2014) 52:185–93. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000050

23. Green A, Pottegård A, Broe A, Diness TG, Emneus M, Hasvold P, et al. Initiation and persistence with dual antiplatelet therapy after acute myocardial infarction: a Danish nationwide population-based cohort study. BMJ Open. (2016) 6:e010880. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010880

24. Hickson RP, Robinson JG, Annis IE, Killeya-Jones LA, Korhonen MJ, Cole AL, et al. Changes in statin adherence following an acute myocardial infarction among older adults: patient predictors and the association with follow-up with primary care providers and/or cardiologists. J Am Heart Assoc. (2017) 6:e007106. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.007106

25. Holme I, Szarek M, Cater NB, Faergeman O, Kastelein JJ, Olsson AG, et al. Adherence-adjusted efficacy with intensive versus standard statin therapy in patients with acute myocardial infarction in the IDEAL study. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. (2009) 16:315–20. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e32832130f5

26. Kramer JM, Hammill B, Anstrom KJ, Fetterolf D, Snyder R, Charde JP, et al. National evaluation of adherence to beta-blocker therapy for 1 year after acute myocardial infarction in patients with commercial health insurance. Am Heart J. (2006) 152:454.e1-8. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.02.030

27. Kubica A, Kasprzak M, Obonska K, Fabiszak T, Laskowska E, Navarese EP, et al. Discrepancies in assessment of adherence to antiplatelet treatment after myocardial infarction. Pharmacology. (2015) 95:50–8. doi: 10.1159/000371392

28. Lauffenburger JC, Robinson JG, Oramasionwu C, and Fang G. Racial/Ethnic and gender gaps in the use of and adherence to evidence-based preventive therapies among elderly Medicare Part D beneficiaries after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. (2014) 129:754–63. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002658

29. Luu NM, Dinh AT, Nguyen TTH, and Nguyen VH. Adherence to antiplatelet therapy after coronary intervention among patients with myocardial infarction attending vietnam national heart institute. Biomed Res Int. (2019) 2019:6585040. doi: 10.1155/2019/6585040

30. McGinnis BD, Olson KL, Delate TM, and Stolcpart RS. Statin adherence and mortality in patients enrolled in a secondary prevention program. Am J Manag Care. (2009) 15:689–95.

31. Monaldi B, Bologna G, Costa GG, D'Agostino C, Ferrante F, Filice M, et al. Adherence to statin treatment following a myocardial infarction: an Italian population-based survey. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. (2015) 7:273–80. doi: 10.2147/CEOR.S70936

32. Nordstrom BL, Simeone JC, Zhao Z, Molife C, McCollam PL, Ye X, et al. Adherence and persistence with prasugrel following acute coronary syndrome with percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. (2013) 13:263–71. doi: 10.1007/s40256-013-0028-1

33. Ohlsson H, Rosvall M, Hansen O, Chaix B, and Merlo J. Socioeconomic position and secondary preventive therapy after an AMI. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. (2010) 19:358–66. doi: 10.1002/pds.1917

34. Phan DQ, Duan L, Lam B, Hekimian A, Wee D, Zadegan R, et al. Statin adherence and mortality in patients aged 80 years and older after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2019) 67:2045–9. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16037

35. Rasmussen JN, Chong A, and Alter DA. Relationship between adherence to evidence-based pharmacotherapy and long-term mortality after acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. (2007) 297:177. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.2.177

36. Sanfélix-Gimeno G, Franklin JM, Shrank WH, Carlo M, Tong AY, Reisman L, et al. Did HEDIS get it right? Evaluating the quality of a quality measure: adherence to β-blockers and cardiovascular outcomes after myocardial infarction. Med Care. (2014) 52:669–76. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000148

37. Sun Y, Li C, Zhang L, Hu D, Zhang X, Yu T, et al. Poor adherence to P2Y12 antagonists increased cardiovascular risks in Chinese PCI-treated patients. Front Med. (2017) 11:53–61. doi: 10.1007/s11684-017-0502-2

38. Turner RM, Yin P, Hanson A, FitzGerald R, Morris AP, Stables RH, et al. Investigating the prevalence, predictors, and prognosis of suboptimal statin use early after a non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome. J Clin Lipidol. (2017) 11:204–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2016.12.007

39. Wei L, Flynn R, Murray GD, and MacDonald TM. Use and adherence to beta-blockers for secondary prevention of myocardial infarction: who is not getting the treatment? Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. (2004) 13:761–6. doi: 10.1002/pds.963

40. Xie G, Sun Y, Myint PK, Patel A, Yang X, Li M, et al. Six-month adherence to Statin use and subsequent risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) in patients discharged with acute coronary syndromes. Lipids Health Dis. (2017) 16:155. doi: 10.1186/s12944-017-0544-0

41. Zhu B, Zhao Z, McCollam P, Anderson J, Bae JP, Fu H, et al. Factors associated with clopidogrel use, adherence, and persistence in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Curr Med Res Opin. (2011) 27:633–41. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2010.551657

42. Naderi SH, Bestwick JP, and Wald DS. Adherence to drugs that prevent cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis on 376,162 patients. Am J Med. (2012) 125:882–7.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.12.013

43. Lewey J, Shrank WH, Bowry ADK, Kilabuk E, Brennan TA, and Choudhry NK. Gender and racial disparities in adherence to statin therapy: A meta-analysis. Am Heart J. (2013) 165:665–78.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.02.011

44. Soldin OP, and Mattison DR. Sex differences in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Clin Pharmacokinet. (2009) 48:143–57. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200948030-00001

45. Goldstein KM, Zullig LL, Bastian LA, and Bosworth HB. Statin adherence: does gender matter? Curr Atherosclerosis Rep. (2016) 18:63. doi: 10.1007/s11883-016-0619-9

46. Farkouh A, Riedl T, Gottardi R, Czejka M, and Kautzky-Willer A. Sex-related differences in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of frequently prescribed drugs: a review of the literature. Adv Therapy. (2020) 37:644–55. doi: 10.1007/s12325-019-01201-3

47. Franconi F, and Campesi I. Pharmacogenomics, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics: interaction with biological differences between men and women. Brit J Pharmacol. (2014) 171:580–94. doi: 10.1111/bph.12362

48. Faubion SS, Kapoor E, Moyer AM, Hodis HN, and Miller VM. Statin therapy: does sex matter? Menopause. (2019) 26:1425–35. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001412

49. Nanna MG, Wang TY, Xiang Q, Goldberg AC, Robinson JG, Roger VL, et al. Sex differences in the use of statins in community practice. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. (2019) 12:e005562. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.118.005562

50. Mihaylova B, Emberson J, Blackwell L, Keech A, Simes J, Barnes EH, et al. The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with statin therapy in people at low risk of vascular disease: meta-analysis of individual data from 27 randomised trials. Lancet. (2012) 380:581–90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60367-5

Keywords: acute coronary syndome, sex differences, medication adherence, cardiovasccular medicine, women

Citation: Bots SH, Inia JA and Peters SAE (2021) Medication Adherence After Acute Coronary Syndrome in Women Compared With Men: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Glob. Womens Health 2:637398. doi: 10.3389/fgwh.2021.637398

Received: 03 December 2020; Accepted: 15 January 2021;

Published: 22 February 2021.

Edited by:

Rosemary Morgan, Johns Hopkins University, United StatesReviewed by:

Sabra L. Klein, Johns Hopkins University, United StatesJenni Aittokallio, Turku University Hospital, Finland

Copyright © 2021 Bots, Inia and Peters. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sanne A. E. Peters, c3BldGVyc0BnZW9yZ2VpbnN0aXR1dGUub3JnLnVr

Sophie H. Bots

Sophie H. Bots Jose A. Inia

Jose A. Inia Sanne A. E. Peters

Sanne A. E. Peters