- 1Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 2Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 3Department of Pediatrics, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 4Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 5Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St. Michael's Hospital, Unity Health Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 6Joanna Briggs Institute Centre of Excellence, Queen's University, Kingston, ON, Canada

- 7Physician Health Program, Ontario Medical Association, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 8Gerstein Science Information Centre, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 9Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Objectives: The overall objectives of this rapid scoping review are to (a) identify the common triggers of stress, burnout, and depression faced by women in health care during the COVID-19 pandemic, and (b) explore individual-, organizational-, and systems-level interventions that can support the well-being of women HCWs during a pandemic.

Design: This scoping review is registered on Open Science Framework (OSF) and was guided by the JBI guide to scoping reviews and reported using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) extension to scoping reviews. A systematic search of literature databases (Medline, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycInfo and ERIC) was conducted from inception until June 12, 2020. Two reviewers independently assessed full-text articles according to predefined criteria.

Interventions: We included review articles and primary studies that reported on stress, burnout, and depression in HCWs; that primarily focused on women; and that included the percentage or number of women included. All English language studies from any geographical setting where COVID-19 has affected the population were reviewed.

Primary and secondary outcome measures: Studies reporting on mental health outcomes (e.g., stress, burnout, and depression in HCWs), interventions to support mental health well-being were included.

Results: Of the 2,803 papers found, 28 were included. The triggers of stress, burnout and depression are grouped under individual-, organizational-, and systems-level factors. There is a limited amount of evidence on effective interventions that prevents anxiety, stress, burnout and depression during a pandemic.

Conclusions: Our preliminary findings show that women HCWs are at increased risk for stress, burnout, and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic. These negative outcomes are triggered by individual level factors such as lack of social support; family status; organizational factors such as access to personal protective equipment or high workload; and systems-level factors such as prevalence of COVID-19, rapidly changing public health guidelines, and a lack of recognition at work.

Strengths and Limitations of this Study

• A rapid scoping review was conducted to identify stress, burnout and depression faced by women HCWs during COVID-19.

• To ensure the relevance of our review, representatives from the women HCWs were engaged in defining the review scope, developing review questions, approving the protocol and literature search strategies, and identifying key messages.

• It provides a descriptive synthesis of current evidence on interventions to prevent mental health for women HCWs.

• Most studies used cross-sectional surveys, making it difficult to determine the longitudinal impact.

• There was significant variability in the tools used to measure mental health.

Introduction

COVID-19 pandemic-related measures, such as prolonged periods of social isolation, unexpected employment disruptions, school closures, financial distress, and changes to routine, are having an unprecedented negative impact on women's mental well-being (UN). Over 80% of the health workers in Canada are women (1). Women in health care already face systemic challenges related to workplace gender biases, discrimination, sexual harassment, and other inequities (2). Studies show that women physicians are more likely than male physicians to experience depression, burnout, and suicidal ideation (3, 4). Additionally, women perform three times more unpaid care work than men as parents and primary caregivers to family members (5).

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to increased psychological trauma and suicide among health care workers (HCWs) (6–10). A poll of HCWs conducted by the Public Health Agency of Canada in April 2020 showed that 47% of respondents expressed the need for psychological support due to COVID-19 related factors; 90% of the respondents were women (11). Similarly, a survey conducted by the British Medical Association in April, 2020 of HCWs showed that 44% of respondents indicated they were experiencing burnout, depression, anxiety, or other mental health conditions due to COVID-19-related factors (12). Unaddressed stress and burnout can lead to depression, suicidal ideation, and substance abuse (4, 13). A healthy workforce is the cornerstone of a well-functioning health care system. Yet, there is a systemic lack of evidence-informed services that provide timely, accessible, and high-quality care for HCWs during public health crises. This is especially relevant for health systems and professional societies who recognize the importance of preventing and mitigating stress, burnout, depression, and suicidal ideation in their workforce during pandemics. In addition, these interventions are essential for the well-being and retention of the health care workforce. This review attempts to answer the following questions: What are the common triggers of occupational stress, burnout, and depression faced by women in health care during the COVID-19 pandemic? What individual-, organizational-, and systems-level interventions can support the well-being of women HCWs during a pandemic?

Overall Objectives

The overall objectives of this review are to (a) identify the common triggers of occupational stress, burnout, and depression faced by women in health care during the COVID-19 pandemic, and (b) explore individual-, organizational-, and systems-level interventions that can support the well-being of women HCWs during a pandemic.

Methods

Commissioning Agency

The Canadian Institute for Health Research issued a special call to address COVID-19 in Mental Health & Substance Use issues. Given there has not been any previous research in this topic area, and the need to provide decision-makers with timely results, a rapid scoping review was conducted in accordance with the WHO Rapid Review Guide and the JBI 2020 guide to scoping reviews (14, 15) and reported using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) for scoping reviews. Scoping reviews help map the key concepts and underpin a field of research and clarify working definitions (16, 17).

Protocol

This review is registered with the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/y8fdh/?view_only=1d943ec3ddbd4f5c8f6a9290eca2ece7).

Eligibility Criteria

The following PICOS (population, intervention, comparator, outcome, Study Design) eligibility criteria were developed a priori:

Population

Women HCWs. We define HCWs as “all people engaged in actions whose primary intent is to enhance health,” (18). This encompasses a broad array of health workers, including doctors, nurses, pharmacists, midwives, paramedics, physical therapists, technicians, personnel support workers, and community health workers. We included studies that primarily focused on women.

Interventions

Our inclusion criteria were all studies (primary and review articles) that reported on the causes of stress, burnout, and depression in HCWs and/or reported programs to mitigate stress, burnout, and Depression in HCWs.

Comparators

Not applicable for the purpose of this scoping review.

Outcomes

We looked at following outcomes: stress, burnout, and depression. We define stress as the degree to which one feels overwhelmed and unable to cope as a result of unmanageable pressures (19). We define burnout as the experience of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, or cynicism, along with feelings of diminished personal efficacy or accomplishment in the context of the work environment (20). We characterize depression according to a series of symptoms, including low mood, changes in appetite and sleep, difficulty concentrating, loss of interest/pleasure and thoughts of suicide that persist for at least 2 weeks (21).

Study Design

We included review articles and primary studies where data were collected and analyzed using quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods (14). We excluded editorials and opinion pieces unless the authors shared their personal experiences.

Search Methods and Information Sources

We conducted comprehensive search strategies in the following electronic databases: Medline (via OVID), Embase (via Ovid), CINAHL (via EBSCOHost), PsycINFO (via Ovid), and ERIC (via ProQUEST). Search strategies were developed by an academic health sciences librarian (APA), with input from the research team. The search was original built in MEDLINE Ovid, and peer reviewed using the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) tool (22), before being translated into other databases using their command language if applicable. The Coronavirus (Covid-19) 2019-nCov expert search from Ovid MEDLINE was used and translated to other databases. Searches were limited to articles published until June 12th, 2020, and by English language. The final search results were exported into Covidence, a review management software, where duplicates were identified and removed.

Screening Process

To minimize selection bias, we piloted 20 articles against a priori inclusion and exclusion criteria. Each article title was reviewed by two independent screeners against using Covidence. A third reviewer reviewed conflicts and resolved disagreements through discussion. Two reviewers also independently screened the full text of potentially eligible articles to check whether the articles fulfilled the inclusion criteria.

Data Charting

We used a predefined data extraction form to extract data from the papers included in the review. To ensure the integrity of the assessment, we piloted the data extraction form on three studies. We extracted the following information from the studies: the first author, year of publication, HCWs enrolled in the study, geographic location, study methods, and intervention information that could help answer our objectives. Scoping reviews are conducted to provide an overview of the existing evidence regardless of methodological quality or risk of bias. As a standard, included sources of evidence are not critically appraised for scoping reviews (14, 15). In accordance with this we did not appraise quality or risk of bias of the included articles. Ethical approval was not required for this review.

Data Synthesis

Due to heterogeneity regarding outcome measurement and statistical analysis, data was descriptively synthesized.

Patient Involvement

No patients were involved in setting the research question or the outcome measures, nor were they involved in the design and implementation of the study.

Results

Search Results

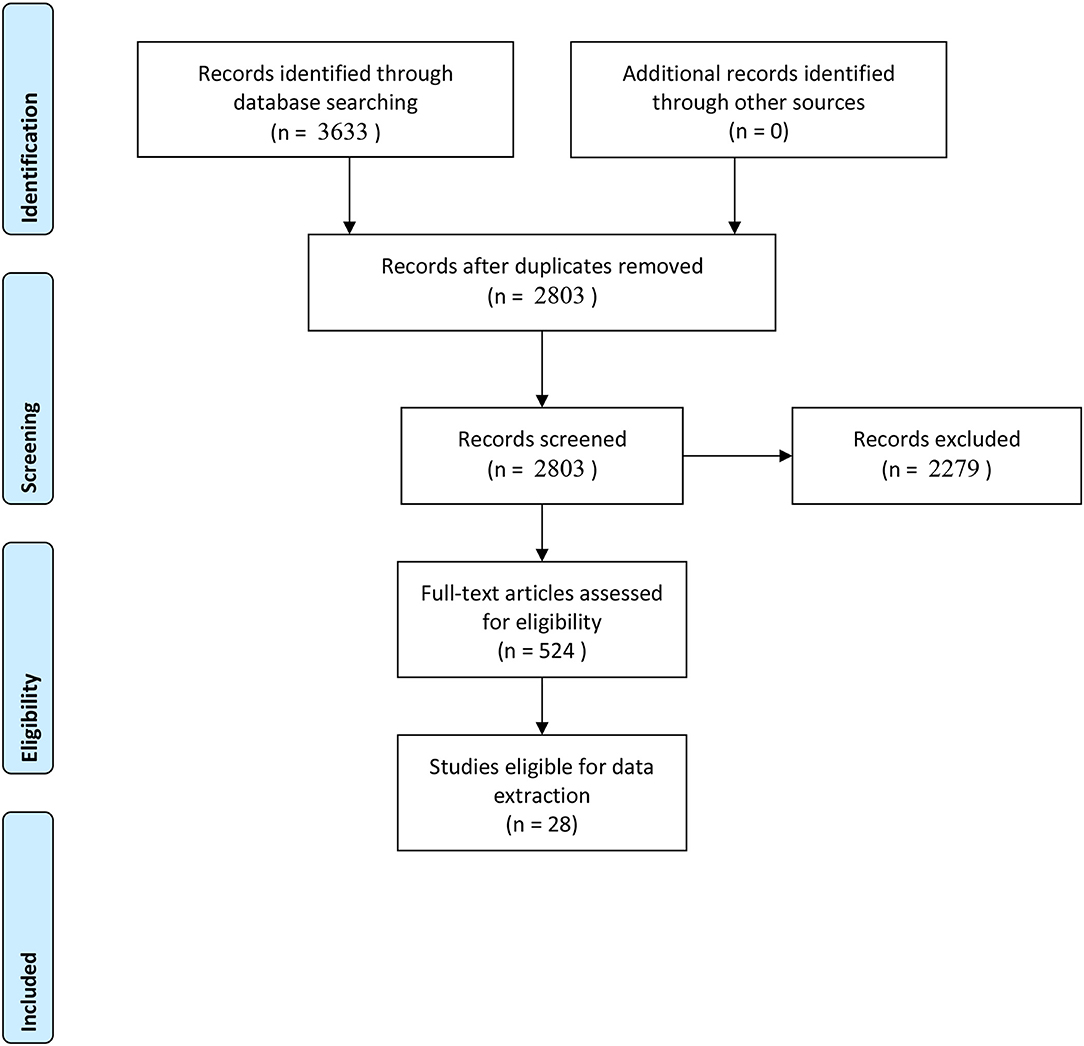

The search resulted in a total of 3,633 records. After 830 duplicates were removed, 2,803 records remained to be screened. We excluded 2,279 records based on title and abstract screening. We assessed 524 full-text articles. Most of these articles are opinion pieces and commentaries. Twenty eight published studies met our inclusion criteria and were included in this review. Figure 1 provides a summary of the PRISM flow diagram.

Characteristics of Studies

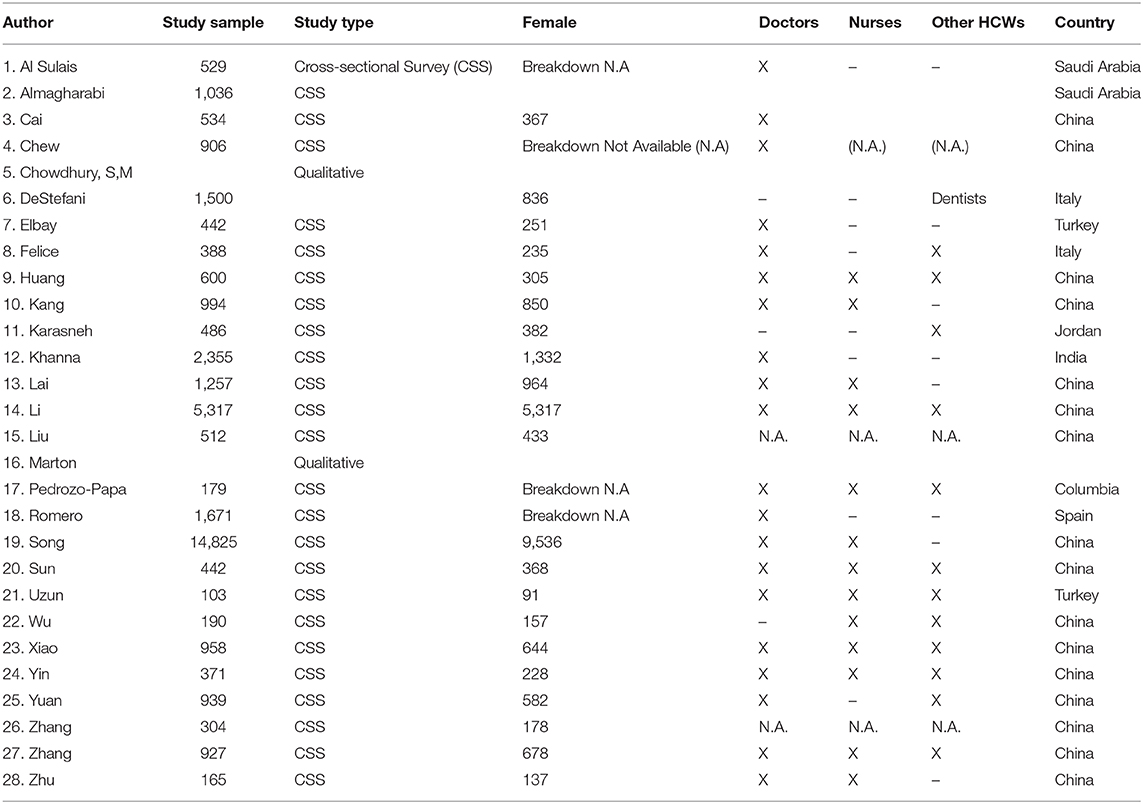

Our search identified 28 eligible studies; 26 of these studies focused on the prevalence of mental health issues in health care professionals (Table 1). Two studies were case studies (Table 1). Sixteen of the primary studies were conducted in China, whereas others were conducted in Saudi Arabia, Italy, Singapore, India, and Colombia. These studies primarily focused on doctors, nurses, and generalized groups of allied health professionals. One study focused on dentists, whereas another focused-on pharmacists. The study samples included both male and women health professionals. Only one study focused exclusively on women in health care (23). Anxiety, depression, stress/distress symptoms, post-traumatic stress disorder, and insomnia were commonly assessed mental health issues in these studies.

A variety of assessment tools were used to measure mental health in these studies. Common tools used to measure psychosocial well-being included DASS-21, Impact of Event Scale Revised Questionnaire (IES-R), Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale, Chinese Perceived Stress Scale, Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) Scale, Questionnaire Star, Psychological Symptom Screening Test (SCL-90-R), Beck Anxiety Inventory and Short Psychiatric Rating Scale, Maslach Burnout Inventory-Medical Personnel, Perceived Stress Scale and Hospital Anxiety/Depression Scale, Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, Stress Response Questionnaire, Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale SF-12, K6, Insomnia Severity Index, Self-Rating Depression Scale, and Simplified Coping Style Questionnaire.

Common Triggers of Stress, Burnout, and Depression Faced by Women in Health Care During the Coronavirus Pandemic

Common triggers of mental health issues were fears of getting infected with COVID-19 and putting family members at risk (24–26), as well as concerns about professional growth, difficulty meeting living expenses (27), and having family members with suspected and confirmed COVID-19 (23). Individual-, organizational-, and systems-level factors are reported as common triggers of stress, burnout, and depression in women HCWs.

Individual-Level Factors

Women HCWs are more likely than men HCWs to experience psychological stress and burnout (24, 28–36). More specifically, young women HCWs and mid-career women HCWs were more likely to experience emotional and mental health issues due to COVID-19 (23, 29, 37). Similarly, less working experience and self-perception about lack of competency to care for COVID-19 patients was associated with increased prevalence of stress and burnout (29, 37). Women who are single or lacking social support are more at risk of developing symptoms of anxiety, stress and burnout (23, 29, 37–39). Women HCWs with medical or psychiatric comorbidities (23, 39) or increased alcohol use are at higher risk of mental health issues (37). Surprisingly, women HCWs who have more than two children experience higher prevalence of psychosocial well-being (29).

Organizational-Level Factors

Long working hours and increased workload (29, 37, 40); increased number of COVID-19 patients under their care (29, 41); lack of access to personal protective equipment (25, 26, 28, 30, 40, 42–44); lack of infection control guidelines and protocols (26, 29, 42, 45); lack of support and recognition by their peers, supervisors, and hospital leadership (26, 29); and work location (30, 43) are reported as common triggers of mental health issues related to the work environment.

Systems-Level Factors

Increased incidence of COVID-19 cases in the local area (26), changes in public health measures and guidelines (46), information shared in the media (47), and lack of recognition by the government officials and policy makers of HCWs' work conditions (26) are reported to increase stress and mental health issues among HCWs.

Interventions That Can Support the Well-Being of Women HCWs During a Pandemic

Very few studies have discussed potential interventions to support women in health care with COVID-19 related stress, anxiety, and mental health. Women with increased workloads preferred to use psychological support (40). Regular exercise is considered a protective factor for depression and anxiety (23). Time is considered a modifiable factor that improves anxiety level (32). Mental health services such as online resources, psychological assistance hotlines, and group activities for stress reduction are poorly utilized by HCWs (38). Online-push messages of mental health self-help and self-help books are mostly preferred by women HCWs (38). Measures to support HCWs financially (25), provision of rest areas for sleep and recovery (Yin, 29), care for basic physical needs such as food (38), training programs to improve resiliency (33), information on protective measures (38), and access to leisure activities (38) and counselors (38, 41) are considered potential strategies to support HCWs during a pandemic. However, these studies did not measure the impact of these interventions.

Discussion

This review shows that individual characteristics such as sex (women), age (younger women), marital status (single women and women with young children), and career stage (less experience) have been contributing factors to occupational stress, burnout, and depression during COVID-19. The current literature lacks data on how socioeconomic, cultural, and ethnoracial differences influence occupational stress, burnout, and depression in women HCWs.

At the organizational level, lack of training, poor infection control guidelines, work conditions that include changing policies, higher workload, and inadequate access to personal protective equipment are contributing to occupational stress, burnout, and depression in women during COVID-19. The long-term effects of burnout during COVID-19 are unknown. General studies on burnout in HCWs has shown an association between burnout and poor career satisfaction, high absenteeism, career transitions, early retirements, and familial and marital stressors (48, 49).

This review shows there is relatively little empirical research into possible interventions to help support women HCWs during a pandemic. Interventions to reduce occupational stress and burnout among HCWs have primarily focused on providing mental health services such as online resources and psychological assistance hotlines, the effects of which have been mixed. This is consistent with findings from HCW burnout studies unrelated to COVID-19. There is a lack of understanding about the effects of organizational interventions such as workload policies and procedures; organizational support systems, such as employee assistance programs; coaching and resiliency and mindfulness training programs, such as reducing working hours; caseloads; and on-call procedures.

Virtually all empirical studies included in this review are epidemiological studies of occupational stress, burnout, and depression. However, there was a significant variability in the tools used to measure stress, burnout, and depression. Further, the current literature has emerged from limited geographical regions. It is unclear how variations in health care and organizational and cultural contexts will shape the outcomes of similar studies carried out across a broader geographic area. During the search and screening, we specifically focused on including articles focused on female health workers or articles that included both genders. We noticed, often the gender-based analysis was clearly articulated in several publications.

This review covers limited empirical and review studies published on the topic of stress, burnout and health care workers from the start of COVID-19 until June 2020. As a scoping review, we were able to map the emerging concepts that underpin occupation stress and wellness for health care women during the COVID-19 pandemic. We expect to see an increased number of publications concerning COVID-19's impact on health professionals will emerge in the next 6 months. We have registered a rapid review protocol in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO CRD42020189750) to systematically examine the emerging evidence on occupational stress, burnout, and depression in HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusions

Women HCWs are at increased risk for occupational stress, burnout, and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic because of a combination of personal and organizational factors. However, there is a significant gap in the evidence base as to what interventions can help address these issues. We recommend that health-system decision-makers, hospitals, and professional organizations support research that measures the long-term impact of COVID-19 on women in health care and outcome studies that measure the impact of various mental health interventions and resources supporting women in health care. Given the complex nature of these interventions, we urge future researchers to provide the contexts in which the interventions were implemented and the mechanisms that shape successful interventions.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

AS, SR, AT, and DL conceptualized and designed the review. AS, AA, HP, and DDL reviewed titles, abstracts, and full-text papers for eligibility. AS, HP, and DDL were responsible for extracting data and all data extraction was verified by AS. AS prepared the initial draft manuscript. SR, AT, and DL reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was supported through a grant from the Canadian Institute for Health Research Operating Grant: Knowledge Synthesis: COVID-19 in Mental Health & Substance Use. AT was funded by a Tier 2 Canada Research Chair in Knowledge Synthesis.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Authors acknowledge the contribution by Sabine Caleja who helped with article retrieval and screening. This manuscript has been released as a pre-print at medRxiv (50).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgwh.2020.596690/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Porter A, Bourgeault I. Gender, Workforce and Health System Change in Canada. Canadian Institute for Health Information (2017). Available online at: http://158.232.12.119/hrh/Oral-Gender-equity-and-womens-economic-empowerment-Porter-and-Bourgeault-16Nov-17h30-18h30.pdf (accessed May 2, 2020).

2. Ghebreyesus T. Female Health Workers Drive Global Health. (2019). Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/female-health-workers-drive-global-health 2019 (accessed May 2, 2020).

3. Gold KJ, Andrew LB, Goldman EB, Schwenk TL. “I would never want to have a mental health diagnosis on my record”: a survey of female physicians on mental health diagnosis, treatment, and reporting. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. (2016) 43:51–7. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2016.09.004

4. Guille C, Frank E, Zhao Z, Kalmbach DA, Nietert PJ, Mata DA, et al. Work-family conflict and the sex difference in depression among training physicians. JAMA Intern Med. (2017) 177:1766–72. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.5138

5. UN Women Headquarters. COVID-19 and Ending Violence Against Women and Girls. Available online at: https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2020/04/issue-brief-covid-19-and-ending-violence-against-women-and-girls (accessed May 2, 2020).

6. Mock J. Psychological Trauma is the Next Crisis for Coronavirus Health Workers. Scientific American (2020). Available online at: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/psychological-trauma-is-the-next-crisis-for-coronavirus-health-workers (accessed May 2, 2020).

7. Orr C. 'COVID-19 Kills in Many Ways': The Suicide Crisis Facing Health-Care Workers. Canada's National Observer. (2020). Available online at: https://www.nationalobserver.com/2020/04/29/analysis/covid-19-kills-many-ways-suicide-crisis-facing-health-care-workers (accessed May 2, 2020).

8. Pappa S, Ntella V, Giannakas T, Giannakoulis VG, Papoutsi E, Katsaounou P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 88:901–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026

9. Spoorthy MS, Pratapa SK, Mahant S. Mental health problems faced by healthcare workers due to the COVID-19 pandemic–a review. Asian J Psychiatr. (2020) 51:102119. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102119

10. Vindegaard N, Benros ME. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: systematic review of the current evidence. Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 89:531–42. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.048

11. McKinley S. Canadian Health Workers on COVID-19 Front Line Say They Need Mental Health Support, Poll Indicates. (2020). Available online at: https://www.cpha.ca/canadian-health-workers-covid-19-front-line-say-they-need-mental-health-support-poll-indicates (accessed November 8, 2020).

12. BMA News Team. Steps and Burnout Warning Over COVID-19. (2020). Available online at: https://www.bma.org.uk/news-and-opinion/stress-and-burnout-warning-over-covid-19 (accessed May 2, 2020).

13. Oreskovich MR, Kaups KL, Balch CM, Hanks JB, Satele D, Sloan J, et al. Prevalence of alcohol use disorders among American surgeons. Arch Surg. (2012) 147:168–74. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.1481

14. Peters MDJ, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Tricco AC, Khalil H. Chapter 11: scoping reviews. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI Reviewer's Manual, JBI. (2020). Available online at: https://wiki.jbi.global/display/MANUAL/JBI+Manual+for+Evidence+Synthesis (accessed November 8, 2020).

15. Tricco AC, Langlois E, Straus SE, editors. Rapid Reviews to Strengthen Health Policy and Systems: A Practical Guide. Geneva: World Health Organization. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO (2017). Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/258698/9789241512763-eng.pdf?sequence=1

16. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. (2005) 8:19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616

17. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. (2018) 169:467–73. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850

18. WHO. The World Health Report 2006 – Working Together for Health. Geneva: World Health Organization (2006). Available online at: https://www.who.int/whr/2006/whr06_en.pdf (accessed May 2, 2020).

19. Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Organ Behav. (1981) 2:99–113. doi: 10.1002/job.4030020205

20. Templeton K, Bernstein CA, Sukhera J, Nora LM, Newman C, Burstin H, et al. Gender-based differences in burnout: ISSUES faced by women physicians. NAM Perspect. (2019) 1–16. doi: 10.31478/201905a

21. Mental Health Foundation. Stress. Available online at: https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/a-to-z/s/stress (accessed May 2, 2020).

22. McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol. (2016) 75:40–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021

23. Li G, Miao J, Wang H, Xu S, Sun W, Fan Y, et al. Psychological impact on women health workers involved in COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan: a cross-sectional study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. (2020) 91:895–7. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2020-323134

24. Al Sulais E, Mosli M, AlAmeel T. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on physicians in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. Saudi J. Gastroenterol. (2020) 26:249–55. doi: 10.4103/sjg.SJG_174_20

25. Almaghrabi RH, Alfaraidi HA, Al Hebshi WA, Albaadani MM. Healthcare workers experience in dealing with Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Saudi Med J. (2020) 41:657–60. doi: 10.15537/smj.2020.6.25101

26. Cai H, Tu B, Ma J, Chen L, Fu L, Jiang Y, et al. Psychological impact and coping strategies of frontline medical staff in hunan between January and March 2020 during the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Hubei, China. Med. Sci. Monit. (2020) 26:e924171. doi: 10.12659/MSM.924171

27. Khanna RC, Honavar SG, Metla AL, Bhattacharya A, Maulik PK. Psychological impact of COVID-19 on ophthalmologists-in-training and practising ophthalmologists in India. Indian J. Ophthalmol. (2020) 68:994. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1458_20

28. Huang L, Wang Y, Liu J, Ye P, Cheng B, Xu H, et al. Factors associated with resilience among medical staff in radiology departments during the outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a cross-sectional study. Med. Sci. Monit. (2020) 26:e925669-1–10. doi: 10.12659/MSM.925669

29. Elbay RY, Kurtulmuş A, Arpacioglu S, Karadere E. Depression, anxiety, stress levels of physicians and associated factors in covid-19 pandemics. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 290:113130. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113130

30. Xiao X, Zhua X, Fua S, Hub Y, Lia X, Xiaoa Y. (2020). Psychological impact of healthcare workers in China during COVID-19 pneumonia epidemic: a multi-center cross-sectional survey investigation. J Affect Disord. 274:405–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.081

31. Yin Q, Sun Z, Liu T, Ni X, Deng X, Jia Y, et al. Posttraumatic stress symptoms of health care workers during the corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Clin Psychol Psychother. (2020) 27:384–95. doi: 10.1002/cpp.2477

32. Yuan S, Liao Z, Huang H, Jiang B, Zhang X, Wang Y, et al. Comparison of the indicators of psychological stress in the population of Hubei Province and non-endemic provinces in China during two weeks during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in February 2020. Med Sci Monit. (2020) 26:e923767-10. doi: 10.12659/MSM.923767

33. Zhu J, Sun L, Zhang L, Wang H, Fan A, Yang B, et al. Prevalence and influencing factors of anxiety and depression symptoms in the first-line medical staff fighting against COVID-19 in Gansu. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:386. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00386

34. Sun D, Yang D, Li Y, Zhou J, Wang W, Wang Q, et al. Psychological impact of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak on health workers in China. Epidemiol Infect. (2020) 148:e96. doi: 10.1017/S0950268820001090

35. Chew NW, Lee GK, Tan BY, Jing M, Goh Y, Ngiam NJ, et al. A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak. Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 88:559–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.049

36. Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, Hu J, Wei N, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. (2020) 3:e203976. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976

37. Song X, Fu W, Liu X, Luo Z, Wang R, Zhou N, et al. Mental health status of medical staff in emergency departments during the Coronavirus disease 2019 epidemic in China. Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 88:60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.06.002

38. Kang L, Ma S, Chen M, Yang J, Wang Y, Li R, et al. Impact on mental health and perceptions of psychological care among medical and nursing staff in Wuhan during the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak: a cross-sectional study. Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 87:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.03.028

39. Uzun ND, Tekin M, Sertel E, Tuncar A. Psychological and social effects of COVID-19 pandemic on obstetrics and gynecology employees. J Surg Med. (2020) 4:355–8. doi: 10.28982/josam.735384

40. Felice C, Di Tanna GL, Zanus G, Grossi U. Impact of COVID-19 outbreak on healthcare workers in italy: results from a national E-survey. J Commun Health. (2020) 45:675–83. doi: 10.1007/s10900-020-00845-5

41. Liu CY, Yang YZ, Zhang XM, Xu X, Dou QL, Zhang WW, et al. The prevalence and influencing factors in anxiety in medical workers fighting COVID-19 in China: a cross-sectional survey. Epidemiol Infect. (2020) 148:e98. doi: 10.1017/S0007485320000413

42. De Stefani A, Bruno G, Mutinelli S, Gracco A. COVID-19 Outbreak Perception in Italian Dentists. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:3867. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17113867

43. Zhang WR, Wang K, Yin L, Zhao WF, Xue Q, Peng M, et al. Mental health and psychosocial problems of medical health workers during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Psychother Psychosom. (2020) 89:242–50. doi: 10.1159/000507639

44. Zhang SX, Liu J, Jahanshahi AA, Nawaser K, Yousefi A, Li J, et al. At the height of the storm: healthcare staff's health conditions and job satisfaction and their associated predictors during the epidemic peak of COVID-19. Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 87:144–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.010

45. Wu Y, Wang J, Luo C, Hu S, Lin X, Anderson AE, et al. A comparison of burnout frequency among oncology physicians and nurses working on the frontline and usual wards during the COVID-19 epidemic in Wuhan, China. J Pain Symptom Manag. (2020) 60: e60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.008

46. Pedrozo-Pupo JC, Pedrozo-Cortés MJ, and Campo-Arias A. Perceived stress associated with COVID-19 epidemic in Colombia: an online survey. Cadernos de Saúde Pública. (2020) 36:e00090520. doi: 10.1590/0102-311x00090520

47. Karasneh R, Al-Azzam S, Muflih S, Soudah O, Hawamdeh S, Khader Y. Media's effect on shaping knowledge, awareness risk perceptions and communication practices of pandemic COVID-19 among pharmacists. Res Soc Administr Pharm. (2020) 1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.04.027

48. Krasner MS, Epstein RM, Beckman H, Suchman AL, Chapman B, Mooney CJ, et al. Association of an educational program in mindful communication with burnout, empathy, and attitudes among primary care physicians. JAMA. (2009) 302:1284–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1384

49. Wallace JE, Lemaire JB, Ghali WA. Physician wellness: a missing quality indicator. Lancet. (2009) 374:1714–21. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61424-0

Keywords: women, health care, occupational stress, burnout, mental health, pandemic, COVID-19, health work force

Citation: Sriharan A, Ratnapalan S, Tricco AC, Lupea D, Ayala AP, Pang H and Lee DD (2020) Occupational Stress, Burnout, and Depression in Women in Healthcare During COVID-19 Pandemic: Rapid Scoping Review. Front. Glob. Womens Health 1:596690. doi: 10.3389/fgwh.2020.596690

Received: 20 August 2020; Accepted: 02 November 2020;

Published: 26 November 2020.

Edited by:

Laura A. Magee, King's College London, United KingdomReviewed by:

Claudia Carmassi, University of Pisa, ItalyNatalie Paige Thomas, Monash Alfred Psychiatry Research Centre, Australia

Copyright © 2020 Sriharan, Ratnapalan, Tricco, Lupea, Ayala, Pang and Lee. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Abi Sriharan, abi.sriharan@utoronto.ca

Abi Sriharan

Abi Sriharan Savithiri Ratnapalan2,3,4

Savithiri Ratnapalan2,3,4 Ana Patricia Ayala

Ana Patricia Ayala