94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Front. Gastroenterol., 16 January 2024

Sec. Gastroenterology and Cancer

Volume 2 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fgstr.2023.1323471

This article is part of the Research TopicGut Microbiota in Health and DiseaseView all 19 articles

Ret is implicated in colorectal cancer (CRC) as both a proto-oncogene and a tumor suppressor. We asked whether RET signaling regulates tumorigenesis in an Apc-deficient preclinical model of CRC. We observed a sex-biased phenotype: ApcMin/+Ret+/- females had significantly greater tumor burden than ApcMin/+Ret+/- males, a phenomenon not seen in ApcMin/+ mice, which had equal distributions by sex. Dysfunctional RET signaling was associated with gene expression changes in diverse tumor signaling pathways in tumors and normal-appearing colon. Sex-biased gene expression differences mirroring tumor phenotypes were seen in 26 genes, including the Apc tumor suppressor gene. Ret and Tlr4 expression were significantly correlated in tumor samples from female but not male ApcMin/+Ret+/- mice. Antibiotics resulted in reduction of tumor burden, inverting the sex-biased phenotype such that microbiota-depleted ApcMin/+Ret+/- males had significantly more tumors than female littermates. Reconstitution of the microbiome rescued the sex-biased phenotype. Our findings suggest that RET represents a sexually dimorphic microbiome-mediated “switch” for regulation of tumorigenesis.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common cancers globally. Ret, which is critical in enteric nervous system (ENS) development and maintenance, has been implicated as both a proto-oncogene (1) and tumor suppressor (2) in CRC. While RET fusions in metastatic CRC portend a poor prognosis (3), specific RET inhibitors such as selpercatinib and pralsetinib have demonstrated efficacy in targeting oncogenic RET rearrangements [reviewed at (4, 5)]. Apc encodes a tumor suppressor and is commonly mutated in CRC. We assessed interactions of Apc and Ret through a crossbreeding experiment using ApcMin/+ mice and Ret+/- mice (6). We administered 1.5% dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) to induce colonic tumors in ApcMin/+Ret+/- progeny (as well as littermate controls with a mutation in Apc only, Ret only, or neither). We expected that ApcMin/+ mice would develop many intestinal tumors compared to wild-type or Ret+/- mice, which are not predisposed to developing tumors, but it was unknown whether mice harboring mutations both in Apc and Ret would develop a greater, lesser, or equivalent number of tumors compared to ApcMin/+ mice. We hypothesized that if tumorigenesis is regulated by RET signaling, then we should observe a change in tumor burden in ApcMin/+Ret+/- mice that is either decreased compared with ApcMin/+ mice if RET signaling promoted tumorigenesis or increased if RET suppressed tumorigenesis.

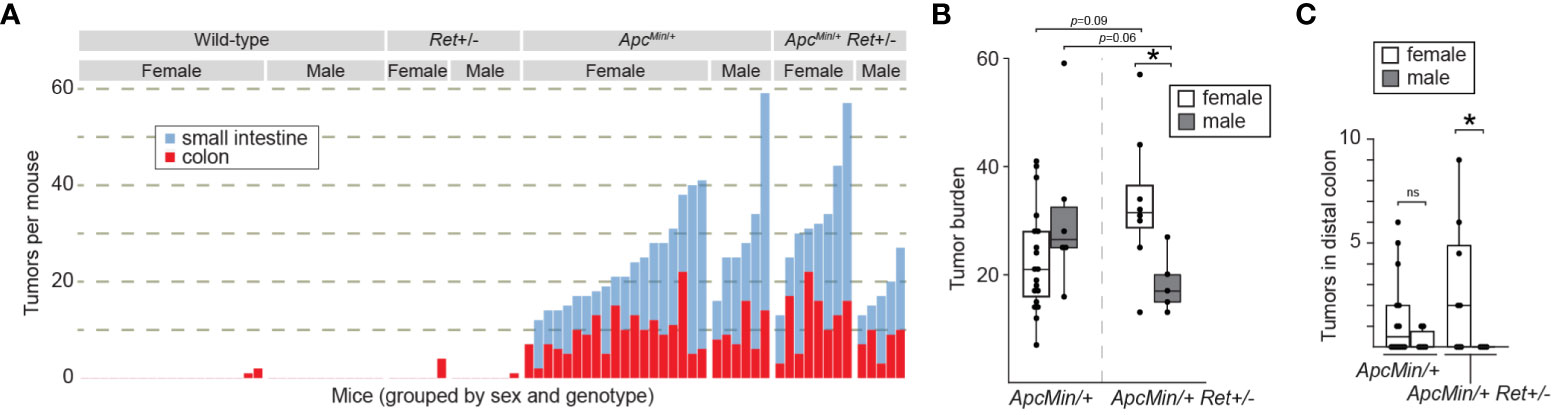

Consistent with expectations, (i) ApcMin/+ mice (n=25) had a significantly greater tumor burden than wild-type littermates (n=31) (mean ± SEM: 22.6 ± 2.2 vs 0.16 ± 0.12, p<10-8 [females]; 31.2 ± 6.1 vs 0 ± 0, p=0.004 [males]; Figures 1A, B; Supplementary Table 1); (ii) Ret+/- mice (n=13) had tumor burdens not significantly different from wild-type littermates (n=31) (0.7 ± 0.7 vs 0.2 ± 0.1 [females]; 0.1 ± 0.1 vs 0 ± 0, [males]; Figure 1A; Supplementary Table 1); and (iii) compared to ApcMin/+ mice that did not receive DSS (n=30), DSS-treated ApcMin/+ mice developed more colonic tumors (9.3 ± 1.0 vs 1.1 ± 0.3, p<10-6 [females]; 10 ± 1.7 vs 1.8 ± 0.3, p=0.004 [males]). In the experimental ApcMin/+Ret+/- cohorts, there was no overall significant difference in tumor burden compared to ApcMin/+ mice (two-way ANOVA; Figure 1A). However, we observed a sex-biased interaction of Ret and Apc: total (colonic plus small intestinal) tumor burden was significantly greater in female ApcMin/+Ret+/- mice compared to male ApcMin/+Ret+/- mice (3-way ANOVA, interaction between Apc, Ret, and sex covariates: p<0.003, F1,74 = 10; Figure 1B). Compared to males, female ApcMin/+Ret+/- mice had significantly greater tumor burden in the distal colon, which we defined as the last 25% of the colon by length (2.94 ± 1.17 vs 0 ± 0, p<0.04, Student’s two-tailed t-test; Figure 1C). In the small intestine, ApcMin/+Ret+/- females had more tumors than males (20.5 ± 4.2 vs 10.6 ± 2.3, p=0.06, Student’s two-tailed t-test). These sex-biased differences did not exist among ApcMin/+ mice.

Figure 1 RET signaling regulates intestinal tumorigenesis in a sex-dependent manner. (A) Tumor burden in male and female wild-type, Ret+/-, ApcMin/+, and ApcMin/+Ret+/- mice treated with 1.5% DSS. Each stacked bar represents one mouse. (B, C) Total intestinal and distal colonic tumor burdens. *: p<0.05, ns: not significant.

Male ApcMin/+Ret+/- mice had longer small intestines than female ApcMin/+Ret+/- mice (36.4 ± 0.37 cm vs 33.9 ± 0.85 cm; p<0.03, Student’s two-tailed t-test). While of unclear biological significance, it excludes small intestinal length as a potential confounder for the difference in small intestinal tumor burden, which was greater in females. Otherwise, there were no sex-based differences in tumor size, intestinal lengths, or whole gut transit times (Supplementary Table 1). Within control cohorts, there were also no sex-based differences in these metrics.

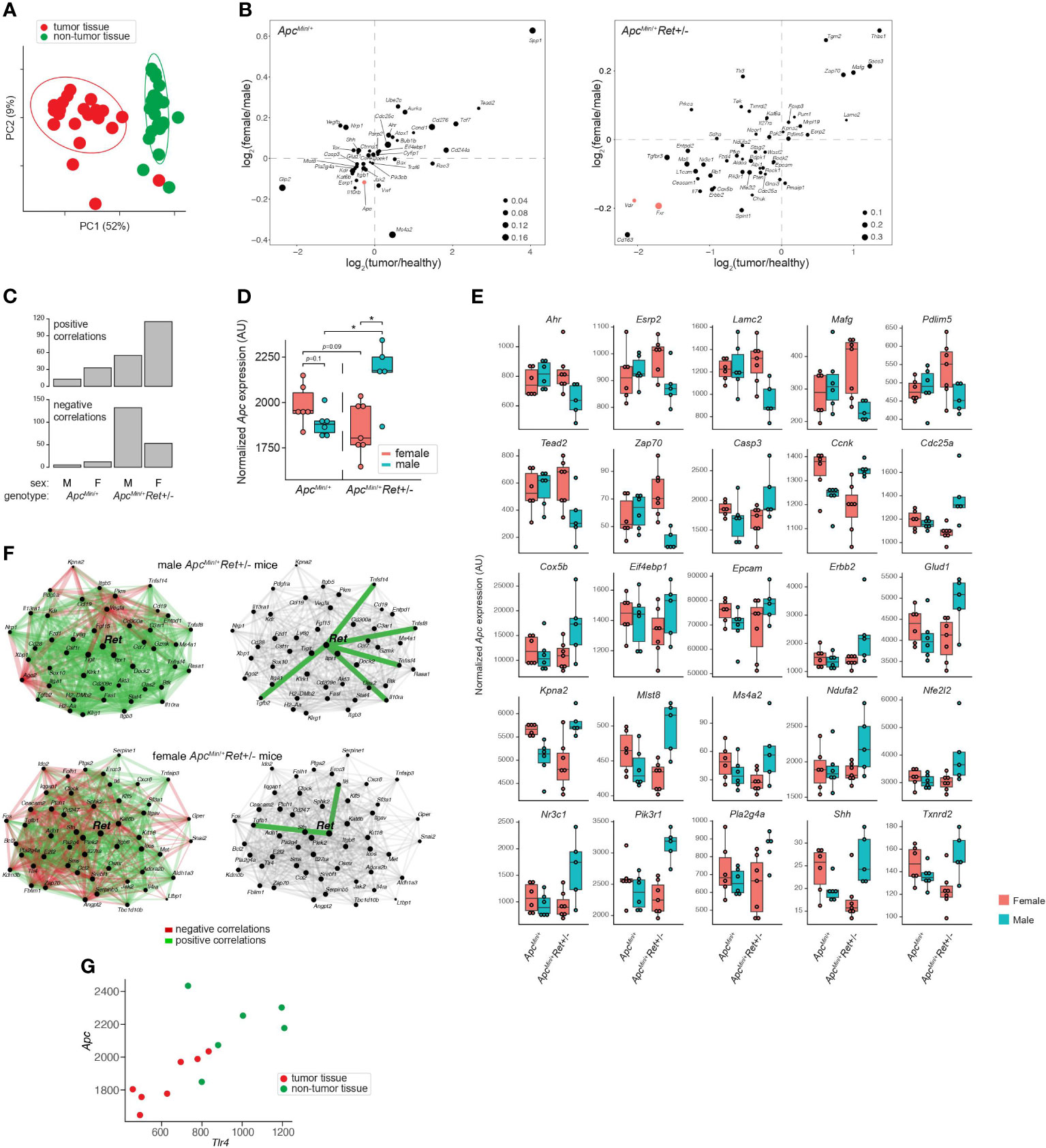

To define Ret’s role in tumor signaling pathways, we profiled gene expression in colonic tumors (n=24) and healthy-appearing colonic tissues (n=24) from male and female ApcMin/+ and ApcMin/+Ret+/- mice (Supplementary Table 2A). Global gene expression profiles clustered predominantly by whether they represented tumors or healthy tissues (p=0.001, PERMANOVA [permutational multivariate analysis of variance using distance matrices] using Bray-Curtis dissimilarity; Figure 2A). Expression levels of a subset of genes were nonetheless affected by the interaction between sex, genotype, and tissue sample type (ANOVA: p<0.05; Figure 2B). Consistent with their established biological roles, Apc, Fxr (Wnt pathway antagonist; bile acid receptor), and Vdr (vitamin D receptor; bile acid receptor) were expressed at higher levels in healthy tissues. In tumors, Myc (oncogene), Lgr5 (stem cell marker), and Wnt5a (Wnt pathway activator) were expressed at higher levels and were affected by the interaction between sex and genotype (ANOVA: p<0.05). Consistent with Fxr’s role as a negative regulator of bile acid synthesis, total bile acid concentrations were higher in females than males (3,604.2 ± 418.2 ng/mg stool vs 2,410.84 ± 177.2 ng/mg stool, p=0.01, Student’s two-tailed t-test).

Figure 2 Global and gene-specific variation in colonic gene expression is regulated by RET signaling in a sex-dependent manner. (A) Principal coordinate analysis of global gene expression variation across samples. (B) Genes whose expression was significantly affected by the interaction between sex, genotype, and sample type. 2D enrichment plots of genes significantly enriched in tumors (x-axis) or in females (y-axis) in ApcMin/+ (left) and ApcMin/+Ret+/- (right) mice. The dot sizes represent log of fold change of expression in each genotype compared to the other. Three genes referenced in the text are colored red. (C) Numbers of genes that are significantly correlated with Apc expression in different sex and genotype contexts. (D) Tumor Apc expression split by cohort. (E) 25 genes, other than Apc, whose expression in tumors mirrored the sex-biased genotype-dependent tumor phenotype based on the mean expression for each group. Plots are organized by genes that first follow the tumor phenotype (U shaped) and then the inverse. (F) Sex biases in Ret gene networks in ApcMin/+Ret+/- mice. (G) Tlr4 and Apc correlation in ApcMin/+Ret+/- females. *: p<0.05.

Ret deficiency appeared to dysregulate homeostatic gene expression networks, resulting in a dramatic increase in numbers of genes significantly correlated with Apc expression in tumor samples (Figure 2C). Interestingly, ApcMin/+Ret+/- female mice had more positive than negative correlations, while ApcMin/+Ret+/- male mice had more negative than positive correlations (Figure 2C). The genes correlated with Apc are implicated in diverse pathways, suggesting global effects on gene expression (Supplementary Table 2B). In healthy samples, Apc expression was greater in ApcMin/+Ret+/- males than in females (2,452 ± 58 arbitrary units [AU] vs 2,181 ± 83 AU, p<0.03, Student’s two-tailed t-test). In tumor samples, ApcMin/+Ret+/- males had significantly higher Apc expression than both ApcMin/+Ret+/- females (2,160 ± 80 AU vs 1,854 ± 55 AU, p<0.02, Student’s two-tailed t-test) and ApcMin/+ males (2,160 ± 80 AU vs 1,885 ± 29 AU, p=0.02, Student’s two-tailed t-test). Notably, within tumor samples, Apc expression was higher in male ApcMin/+Ret+/- mice than in female ApcMin/+Ret+/- mice, and this trend was opposite in ApcMin/+ mice — the inverse of the sex-biased genotype-dependent tumor phenotype (Figure 2D). Including Apc, tumor-intrinsic expression levels of 26 genes mirrored tumor phenotypes (exactly or inversely) and were significantly affected by interactions between sex and genotype (p<0.05, two-way ANOVA) (Figure 2E). While Apc expression levels varied with tumor phenotypes in such a manner that it may plausibly explain the underlying biology, the biological significance of the other 25 genes is more challenging to interpret and underscores complexity of gene network interactions.

Strikingly, tumor-intrinsic Ret-centric gene expression networks were entirely non-overlapping between male and female ApcMin/+Ret+/- mice (Figure 2F). In tumors harvested from ApcMin/+Ret+/- males, we observed correlations between Ret and Il10ra, Tnfsf14, Tnfsf8, Tnfrsf4, and Tgfb2 (r≥0.89, p<0.05, Pearson correlation), which are involved in anti-inflammatory responses. In contrast, in ApcMin/+Ret+/- females, Ret was significantly correlated with Tgfb1 and with Il6 (r≥0.78, p<0.05, Pearson correlation), both of which are involved in upregulating the immune system. These findings suggest links between the immune system and Ret, whereby loss of functional RET signaling leads to a pro-inflammatory state in females and an anti-inflammatory state in males.

Intriguingly, Ret expression was significantly correlated with Tlr4 expression in tumor samples from all cohorts of mice (r≥0.79, p<0.04, Pearson correlation) except for the male ApcMin/+Ret+/- mice. TLR4 is critical in microbial pattern recognition and is overexpressed in colorectal cancers and adenomas compared to healthy tissues in humans (7). Tlr4 was correlated with Apc in ApcMin/+Ret+/- female mice (tumor samples: r=0.88, p<0.01; all samples: r=0.73, p<0.005, Pearson correlation; Figure 2G) but not in other cohorts.

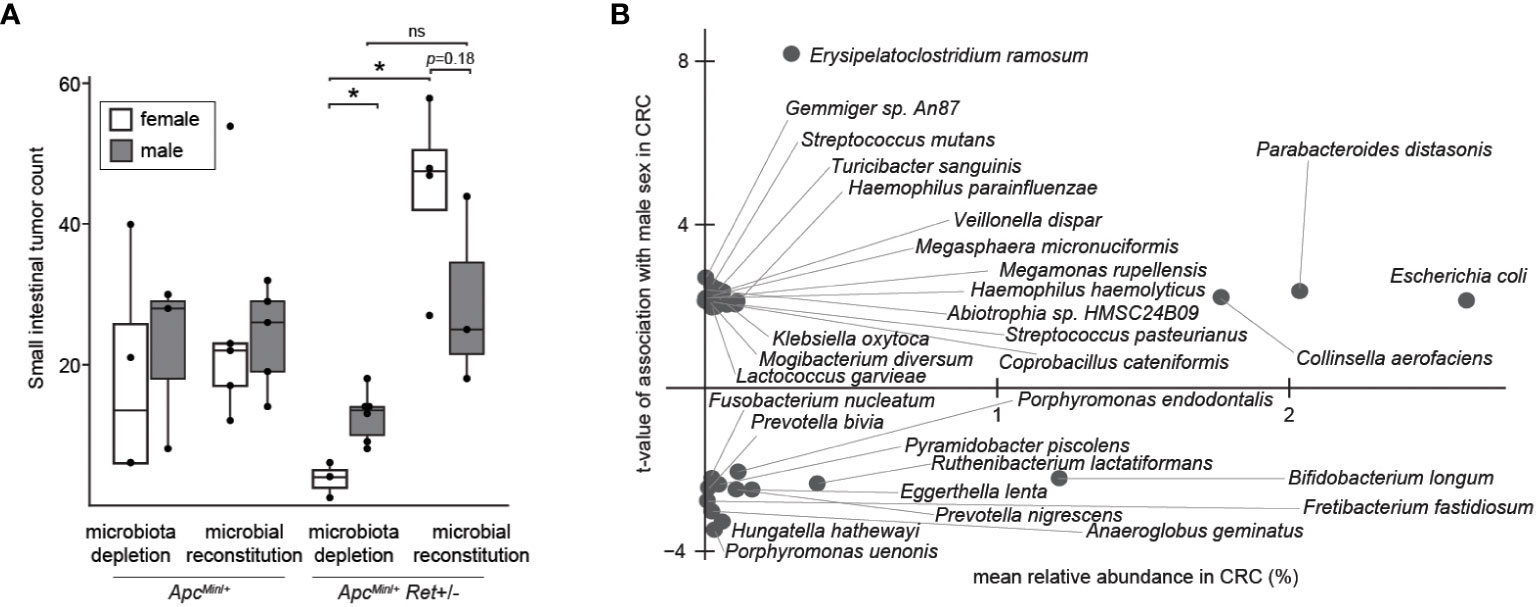

Thus, we next tested the role of the gut microbiome in driving sex bias in tumor phenotypes. We either administered chronic antibiotics or first depleted the native microbiota with antibiotics and then reconstituted the microbiota via oral gavage using a uniform fecal suspension. Chronic antibiotics reduced tumor burden, significantly more so in females, and resulted in complete inversion of the sex-biased tumor phenotype: microbiota-depleted ApcMin/+Ret+/- females had significantly fewer tumors than males (3.7 ± 1.5 vs 12.7 ± 1.5, p=0.005, two-tailed Student’s t-test; Figure 3A). The interaction between sex and microbiome status (harboring or lacking a microbiome) was significant (p<0.02, F1,12 = 7, two-way ANOVA).

Figure 3 The microbiome as a potential sex-biased driver of intestinal tumorigenesis. (A) Effects of microbiota depletion with or without gut microbial reconstitution on tumor burden. (B) Bacterial species enriched in males (up) or females (down) in human CRC microbiomes, adjusting for biases in non-CRC cohorts. *: p<0.05, ns: not significant.

Finally, we asked whether human CRC data support our findings. Approximately 10% of CRCs are reported as harboring Ret mutations (2). Intriguingly, in The Cancer Genome Atlas (8), CRCs with Ret mutations occurred predominantly in females (z=2.98, p<0.003). Further, in a reanalysis of published CRC microbiome surveys (9), we found that 68 bacterial species were differentially abundant between sexes in CRC (Figure 3B); of these, only 11 species were also differentially abundant in the healthy cohort, evidencing CRC-specific sex biases. E. coli was more abundant in males with CRC than in females with CRC, whereas in the healthy cohort, E. coli was more abundant in females than in males. In contrast, Fusobacterium nucleatum was more abundant in females than in males in the CRC cohort. F. nucleatum, which is linked to CRC progression and metastasis, has been associated with CpG methylation and a CpG island methylator phenotype, which is associated with the female sex (10).

The answer to our initial question — is RET an oncogene (1) or tumor suppressor (2) in CRC? — appears to be complicated: it depends on sex and the microbiome. Underlying the phenotype that we discovered were significant differences in tumor burden in the distal colon. Interestingly, public datasets suggest that Ret mutations in CRC and CRC microbiome signatures are both sex-biased. Our study offers proof-of-principle that CRC risk-modulating gut microbial effects depend on sex and genetics, and they underscore the importance of evaluating sex as a biological variable in research and of reporting the sexes of both human and non-human study participants.

A limitation of this study is that the specific cellular players remain unknown. Our gene expression data suggest that both tumor-intrinsic and tumor-extrinsic cells are disrupted by Ret insufficiency, and that the resulting Ret gene networks starkly differ by sex. RET is a critical player in the ENS, which transmits intestinal growth signals via the GLP-2 pathway (11, 12), potentially facilitates CRC metastasis (13, 14), and regulates immunity (15) and physiology (16). Enteric neurons express estrogen receptor (17) so could form the basis for sex-biased microbiome-dependent tumorigenesis. Future studies should elucidate tumor cell-autonomous effects versus effects of a RET-deficient ENS. This research could lead to novel personalized CRC prevention tactics.

Male and female ApcMin/+, Ret+/-, and ApcMin/+Ret+/- mice (C57BL/6 background) were studied using methods approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center (protocol 51049). Mice from the same litter were co-housed regardless of differences in genotype, thereby leading to shared microbiota due to coprophagy. Mice were fed ad libitum with PicoLab Mouse Diet 5058. DSS (1.5% by volume) was administered in drinking water for 7 days to mice at 6-8 weeks of age. Following DSS exposure, mice were given standard drinking water for the remainder of the experiment. Mice were euthanized ~6 weeks after DSS exposure (or earlier if exhibiting symptoms of high tumor burden) using aerosolized 1.5% isoflurane delivered through a precision vaporizer. At euthanasia, small intestines and colons were harvested, rinsed in ice cold phosphate buffered saline to remove fecal material, and opened longitudinally for tumor counting and characterization. Fresh fecal pellets were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C until use. Tumor localization analysis. Digital images of colons were equally split into quartiles. Tumors spanning different segments of the colon had fractions of tumors counted in each segment. These fractions were estimated as 0.25, 0.5, or 0.75, and the fractions for each tumor add up to 1. Microbiome manipulation studies. Vancomycin (1 g/L), metronidazole (1 g/L), and neomycin (0.5 g/L) antibiotics (Millipore Sigma, St. Louis, MO) were delivered via drinking water containing 2% sucrose (20 g/L) over 10 days or, in the experiment involving chronic antibiotic administration, cyclically throughout the duration of the experiment. Recolonization was performed via oral gavage of a fecal suspension from female ApcMin/+Ret+/- mice. Due to enhanced DSS toxicity in the setting of antibiotic use, mice receiving antibiotics were not given DSS; therefore, small intestinal tumor counts were used as readouts in these experimental cohorts.

Using previously published methods (18), mice were gavages with 200 μL per mouse of a sterilized 6% red carmine dye solution (Sigma C1022) and monitored for time to initial passage per rectum. Gavages were performed by the same individual (N.L.) within a consistent time frame in all mice in order to minimize variability.

After flushing with PBS, gut segments were stored in RNAlater (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA) at 4°C for 24 hours and then transferred to -20°C for storage until use. To isolate RNA, 20 mg of each sample was placed into a tube containing 0.1 mm zirconium beads, a 4 mm steel ball, and homogenization buffer before mechanical disruption using a TissueLyser II (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). RNA was purified using RNeasy Mini kits (Qiagen).

Gene expression data were generated using NanoString nCounter® Tumor Signaling 360 Panels in conjunction with a 55-gene Panel Plus.

We utilized curatedMetagenomicData, an R package linked to a database of curated data from nearly 100 microbiome surveys (9). We filtered in stool samples from individuals with CRC and healthy individuals at least 18 years of age, none of whom reported current antibiotic use. We identified 625 stool samples from individuals with CRC (392 males and 233 females) and 5,221 stool samples from otherwise healthy individuals (2,178 males and 3,043 females). To control for differences in age and study population, we included only the subset of individuals from the healthy cohort who were (i) from the same countries represented in the CRC cohort and (ii) within 2 years of age of an individual in the CRC cohort. Ultimately, this resulted in a healthy cohort comprised of 1,707 individuals (911 males and 796 females). We then used corncob, an R package that uses beta-binomial regression to model relative abundances and identify bacteria significantly associated with covariates of interest (19), to identify bacterial species that were significantly differentially abundant in CRC between sexes.

Statistical comparisons were performed in R (version 4.0.0). Figures were generated using R using native functions as well as the ggplot2 (version 3.1.0) and pheatmap (version 1.0.12) packages. Figures were assembled in Adobe Illustrator.

The previously published sequencing datasets re-analyzed in this study can be found in the online curated Metagenomic Data database, which lists the names of the original repositories along with corresponding accession numbers. The gene expression data we generated and present here are reported in Supplementary Table 2.

The animal study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

SK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ND: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by grants from the NIH (NIDDK K08 DK111941; NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA015704; NCI U54 CA274374) and research funds from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center (Pathogen-Associated Malignancies Integrated Research Center; Microbiome Research Initiative).

We are grateful to Sam Minot, David Hockenbery, and other colleagues for helpful feedback. We thank Dr. Robert Heuckeroth for generously providing Ret+/- mice and Dr. Cynthia Sears for generously providing ApcMin/+ mice.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgstr.2023.1323471/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Table 1 | Individual mouse data. Unique mouse identification numbers, cage identification numbers, sex, genotype, age at time of euthanasia, microbiota, whether DSS was used, diet, transit times, small intestinal length, cecal length, colonic length, and tumor counts by location.

Supplementary Table 2 | Gene expression data. (A) Normalized data from the NanoString nCounter® Tumor Signaling 360 Panels in conjunction with a 55-gene Panel Plus. (B) Genes significantly correlated with Apc expression in ApcMin/+ and ApcMin/+Ret+/- mice.

1. Guy R. Association between germline mutations in the RET proto-oncogene and colorectal cancer and polyps. Adv Res Gastroenterol Hepatol (2019) 12:44–47. doi: 10.19080/ARGH.2019.12.555835

2. Luo Y, Tsuchiya KD, Il Park D, Fausel R, Kanngurn S, Welcsh P, et al. RET is a potential tumor suppressor gene in colorectal cancer. Oncogene (2013) 32:2037–47. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.225

3. Pietrantonio F, Di Nicolantonio F, Schrock AB, Lee J, Morano F, Fucà G, et al. RET fusions in a small subset of advanced colorectal cancers at risk of being neglected. Ann Oncol (2018) 29:1394–401. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy090

4. Takahashi M. RET receptor signaling: Function in development, metabolic disease, and cancer. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B (2022) 98:112–25. doi: 10.2183/pjab.98.008

5. Desilets A, Repetto M, Yang S-R, Sherman EJ, Drilon A. RET-altered cancers—A tumor-agnostic review of biology, diagnosis and targeted therapy activity. Cancers (2023) 15:4146. doi: 10.3390/cancers15164146

6. Enomoto H, Crawford PA, Gorodinsky A, Heuckeroth RO, Johnson EM, Milbrandt J. RET signaling is essential for migration, axonal growth and axon guidance of developing sympathetic neurons. Development (2001) 128:3963–74. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.20.3963

7. Sewda K, Coppola D, Enkemann S, Yue B, Kim J, Lopez AS, et al. Cell-surface markers for colon adenoma and adenocarcinoma. Oncotarget (2016) 7:17773–89. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7402

8. The Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature (2012) 487:330–7. doi: 10.1038/nature11252

9. Pasolli E, Schiffer L, Manghi P, Renson A, Obenchain V, Truong DT, et al. Accessible, curated metagenomic data through ExperimentHub. Nat Methods (2017) 14:1023–4. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4468

10. Advani SM, Advani P, DeSantis SM, Brown D, VonVille HM, Lam M, et al. Clinical, pathological, and molecular characteristics of cpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl Oncol (2018) 11:1188–201. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2018.07.008

11. Bjerknes M, Cheng H. Modulation of specific intestinal epithelial progenitors by enteric neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (2001) 98:12497–502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211278098

12. Guan X, Karpen HE, Stephens J, Bukowski JT, Niu S, Zhang G, et al. GLP-2 receptor localizes to enteric neurons and endocrine cells expressing vasoactive peptides and mediates increased blood flow. Gastroenterology (2006) 130:150–64. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.005

13. Liebl F, Demir IE, Rosenberg R, Boldis A, Yildiz E, Kujundzic K, et al. The severity of neural invasion is associated with shortened survival in colon cancer. Clin Cancer Res (2013) 19:50–61. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2392

14. Duchalais E, Guilluy C, Nedellec S, Touvron M, Bessard A, Touchefeu Y, et al. Colorectal cancer cells adhere to and migrate along the neurons of the enteric nervous system. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol (2018) 5:31–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2017.10.002

15. Jarret A, Jackson R, Duizer C, Healy ME, Zhao J, Rone JM, et al. Enteric nervous system-derived IL-18 orchestrates mucosal barrier immunity. Cell (2020) 180:50–63.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.12.016

16. Dey N, Wagner VE, Blanton LV, Cheng J, Fontana L, Haque R, et al. Regulators of gut motility revealed by a gnotobiotic model of diet-microbiome interactions related to travel. Cell (2015) 163:95–107. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.059

17. D’Errico F, Goverse G, Dai Y, Wu W, Stakenborg M, Labeeuw E, et al. Estrogen receptor β controls proliferation of enteric glia and differentiation of neurons in the myenteric plexus after damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci (2018) 115:5798–803. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1720267115

18. Koester ST, Li N, Lachance DM, Dey N. Marker-based assays for studying gut transit in gnotobiotic and conventional mouse models. STAR Protoc (2021) 2:100938. doi: 10.1016/j.xpro.2021.100938

Keywords: colorectal cancer, microbiome, RET, sexual dimorphism, Apc Min/+ mice

Citation: Koester ST, Li N and Dey N (2024) RET is a sex-biased regulator of intestinal tumorigenesis. Front. Gastroenterol. 2:1323471. doi: 10.3389/fgstr.2023.1323471

Received: 17 October 2023; Accepted: 05 December 2023;

Published: 16 January 2024.

Edited by:

Diogo Alpuim Costa, CUF Oncologia, PortugalReviewed by:

Masahide Takahashi, Fujita Health University, JapanCopyright © 2024 Koester, Li and Dey. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Neelendu Dey, bmRleUBmcmVkaHV0Y2gub3Jn

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.