- 1Department of Botany, Hansraj College, University of Delhi, Delhi, India

- 2Institute of Plant Breeding, Genetics and Genomics, University of Georgia, Griffin, GA, United States

- 3Department of Biological Sciences, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC, United States

- 4Bioinformatics Lab, National Institute of Plant Genome Research (NIPGR), New Delhi, India

- 5EVA 4.0 Unit, Faculty of Forestry and Wood Sciences, Czech University of Life Sciences Prague, Suchdol, Czechia

- 6Forest Molecular Entomology Lab, EXTEMIT-K, EVA 4.0, Faculty of Forestry and Wood Sciences, Czech University of Life Sciences Prague, Suchdol, Czechia

- 7Department of Zoology, Deshbandhu College, University of Delhi, New Delhi, India

- 8Delhi School of Climate Change and Sustainability, Institution of Eminence, University of Delhi, Delhi, India

Lipid Transfer Proteins (LTPs) play a crucial role in synthesizing lipid barrier polymers and are involved in defense signaling during pest and pathogen attacks. Although LTPs are conserved with multifaceted roles in plants, these are not yet identified and characterized in Cicer arietinum. In this study, a genome-wide analysis of LTPs was executed and their physiochemical properties, biochemical function, gene structure analysis, chromosomal localization, promoter analysis, gene duplication, and evolutionary analysis were performed using in silico tools. Furthermore, tissue-specific expression analysis and gene expression analysis during pest attack was also conducted for the LTPs. A total of 48 LTPs were identified and named as CaLTPs. They were predicted to be small unstable proteins with “Glycolipid transfer protein” and “Alpha-Amylase Inhibitors, Lipid Transfer and Seed Storage” domains, that are translocated to the extracellular region. CaLTPs were predicted to possess 3–4 introns and were located on all the eight chromosomes of chickpea with half of the CaLTPs being localized on chromosomes 4, 5, and 6, and found to be closely related to LTPs of Arabidopsis thaliana and Medicago trancatula. Gene duplication and synteny analysis revealed that most of the CaLTPs have evolved due to tandem or segmental gene duplication and were subjected to purifying selection during evolution. The promoters of CaLTPs had development-related, phytohormone-responsive, and abiotic and biotic stress-related cis-acting elements. A few CaLTP transcripts exhibited differential expression in diverse tissue types, while others showed no/very low expression. Out of 20 jasmonate-regulated CaLTPs, 14 exhibited differential expression patterns during Helicoverpa armigera–infestation, indicating their role in plant defense response. This study identified and characterized CaLTPs from an important legume, C. arietinum, and indicated their involvement in plant defense against H. armigera-infestation, which can be further utilized to explore lipid signaling during plant-pest interaction and pest management.

1 Introduction

The persistence of environmental stresses has impelled a decline in the quality and quantity of important crops, posing severe challenges to global food and economic security. Amongst the biotic factors, insect pests, pathogens, and animals contribute to one-third of crop losses worldwide (Dhaliwal et al., 2015; Sharma et al., 2017). Plants, being sessile, are exposed to numerous such factors which are detrimental to their growth and development, and have thus, evolved various intrinsic mechanisms in response to stressful conditions. The preformed structures like spines, thorns, and trichomes can be the first level of defense employed by the plants in response to stress. Certain plant defense responses in plants are instigated by insect infestation, referred to as the induced defense mechanisms, that may be operated directly or indirectly. The indirect mode of action curtails the performance of the insects by releasing volatile compounds, such as terpenes, nitrogenous compounds, and indoles, to name a few. The direct responses include alteration in defense-associated protein expression, cell wall modifications, release of secondary metabolites and synthesis of reactive oxygen species (Kessler and Baldwin, 2002; Singh et al., 2008; Pandey et al., 2017; Alhoraibi et al., 2019). The direct defense may also include the release of phytohormones such as jasmonate (MeJA), ethylene, and salicylates (Reymond and Farmer, 1998). MeJA modulates the JA-dependent insect defense genes and plant signaling (Reyes-Díaz et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2018). Therefore, understanding the plant-insect interactions, genes/proteins that regulate the defense mechanisms, changes in their expression and their mode of action is crucial to formulate strategies for protecting crops against insect herbivory (Pandey et al., 2017).

A classic herbivory instance is the attack by the gram pod borer, H. armigera-infestation on C. arietinum L., an essential pulse and widely cultivated food legume in Asia and Africa. Being the most important pest of chickpea, H. armigera has led to severe losses in chickpea production by feeding straight on the foliage and pods, causing colossal damage, and eventually affecting the grain yield (Gowda et al., 2005; Sarmah et al., 2012; Rasool et al., 2015; Khatodia et al., 2017). Generally, the oral secretions of insect herbivores comprise several elicitors, that trigger the differential defense responses in plants. During the injury caused by H. armigera on chickpea, a plethora of changes occur at the molecular and cellular levels such as transcriptional changes and protein synthesis/degradation (Singh et al., 2008; Kerchev et al., 2012). Singh et al., 2008, have identified an array of transcripts that are differentially expressed at the time of H. armigera -infestation on chickpea, which contribute to plant defense against biotic and abiotic stresses, detoxification, signaling, gene regulation, and protein synthesis. In the above study, one defense-related gene, a member of LTP, was also reported to be involved in plant defense. LTPs play a crucial role in synthesizing lipid barrier polymers such as wax, suberin, and sporopollenin and are involved in defense signaling during pathogen attacks. Nevertheless, other members of the LTP family within the chickpea genome are not yet identified and their function during herbivore attacks also remains elusive.

LTPs are small, ubiquitous, lipid-binding cytosolic proteins, having a molecular mass ranging from 7 to 9 kDa and high isoelectric points, which facilitate the exchange of wide-ranging lipids between cellular membranes in vitro. LTP1 and LTP2 are the two major families of LTPs categorized based on their molecular weight. Since the LTPs are not directly associated with the cell walls but are found to be localized in the extracellular regions, they do not entirely suffice the role in intracellular lipid transfer, as proposed by their name. However, they are widely dispersed in the plants such as in the vascular tissues and over exposed surfaces and are encoded by multigene families in the cells (Arondel and Kader, 1990; García-Olmedo et al., 1995; Carvalho and Gomes, 2007; Yeats and Rose, 2008). Alternately, they are known to participate in various biological activities such as direct defense against pathogens as well as abiotic stresses, signaling, loosening of the cell wall and cell expansion, cutin synthesis, cuticular wax accumulation, liquid secretion, modulators of plant growth and seed, pollen, and fruit development, embryogenesis, symbiosis (Kader, 1996; Salcedo et al., 2007; Yeats and Rose, 2008; Salminen et al., 2016; Edqvist et al., 2018).

Since the discovery of LTPs in potato by J.C. Kader in 1975, it has been an abiding area for research in plant systems (Kader, 1975; Arondel and Kader, 1990; Kader, 1996). Previously, several reports give an account of LTPs identified in plants, such as 1 in Amaranthus hypochondriacus (del Carmen Ramírez-Medeles et al., 2003), 49 in Arabidopsis thaliana (Boutrot et al., 2008), 14 in Artemisia annua (Adhikari et al., 2019), 13 in Astragalus sinicus (Chou et al., 2006), 1 in Beta vulgaris (Kristensen et al., 2000), 39 in Cucumis sativus (Wang et al., 2020), 40 in Hordeum vulgare (Duo et al., 2021), 52 in Oryza sativa (Boutrot et al., 2008), 2 in Ricinus communis (Takishima et al., 1988), 5 in Sesamum indicum (Choi et al., 2008) and 83 in Solanum tuberosum (Li et al., 2019). Although LTP family members had been identified and characterized in model and a few crop plants, studies on leguminous crop plants including chickpea have not been explored much.

Chickpea is the third most crucial leguminous crop and their production is severely affected by many biotic and abiotic stresses. Amongst the biotic stresses, H. armigera-infestation causes substantial crop losses (Singh et al., 2008; Kumar et al., 2020). C. arietinum-H. armigera interaction has been investigated at the molecular level (Sanyal et al., 2005; Jaiswal et al., 2012; Dinesh et al., 2017; Singh et al., 2017; Singh et al., 2018a; Singh et al., 2018b; Singh et al., 2018b; Singh et al., 2018c; Barmukh et al., 2021), but the role of LTPs in chickpea plant defense against H. armigera has not been attempted yet. Therefore, we identified members of LTPs in the chickpea genome and characterized them. Through this study, the roles of LTPs in the Fabaceae (Leguminosae) family will be further enriched, as we have identified 48 LTPs from C. arietinum (hereby named CaLTPs). In addition to evaluating their physiochemical properties, chromosomal and subcellular localization, we have also investigated their distribution patterns of introns and exons, motif analysis, and phylogenetic and evolutionary relationships. We have also used RNA-seq data to evaluate the expression of CaLTPs in different tissues and performed relative expression analysis to identify the CaLTPs that are potentially involved in defense against H. armigera -infestation. Our results provide an extensive analysis of CaLTPs and contribute information on the role of CaLTPs in plant defense.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Identification, characterization, and localization of CaLTPs

The Hidden Markov Model profiles of the LTP domain were taken (http://Pfam.sanger.ac.uk/) and searched against chickpea genome to detect the LTP proteins in the C. arietinum with the E value <0.05. Sequences of all hits were retrieved and redundant sequences were removed and the selected sequences were scanned through HMMSCAN (http://hmmer.janelia.org/search/hmmscan) to check for the presence of conserved LTP domain. For further confirmation, selected sequences were utilized to check their similarity with A. thaliana LTPs using BLASTp and tBLASTn with an identity of 50% as the threshold. The genomic and peptide sequences of the CaLTPs were checked manually at NCBI, using both BLASTn and BLASTp, for further confirmation. The physicochemical properties, like isoelectric point (pI), molecular weight, number of amino acids, negatively and positively charged residues, instability, aliphatic indices, and grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY), were enumerated for the candidate CaLTPs, using the ExPASy ProtParam (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/) tool (Walker, 2005). The localization in the subcellular compartments was interpreted using the web tool, Wolf PSORT (https://www.genscript.com/wolf-psort.html), which predicts the localization based on the sorting signal motif and uses the k-nearest neighbor clustering method to group the corelative sequences (Horton et al., 2007)

2.2 Chromosomal localization and promoter analysis of CaLTPs

The ‘Genome’ extension (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/?term=) of the NCBI database was used to discern the chromosomal lengths of the 8 chickpea chromosomes (Bethesda, 1988). The chromosomal location for all the putative LTPs from chickpea, retrieved from NCBI earlier, was used to mark the positions of the candidate LTPs on the chickpea chromosomes, using the MapChart (v2.32) software, downloaded from MapChart (https://www.wur.nl/en/show/mapchart.htm) (Voorrips, R.E., 2002). The promoter sequences (1 kb genomic sequences present upstream to the transcription initiation site) of the CaLTPs were retrieved from the NCBI database and the analysis for the presence of different motifs in these 1,000 bp sequences was performed using the database, PlantCARE (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/) (Lescot et al., 2002).

2.3 Gene structure and motif analysis of CaLTPs

The structural organization of introns and exons in the candidate genes was analyzed and visualized using the Gene Structure Display Server v2.0 (http://gsds.gao-lab.org/) (Hu et al., 2015). The presence of novel conserved motifs in the LTP gene family of chickpea was identified using the MEME suite tool v.5.3.3 (https://meme-suite.org/meme/), such that the number of characters in a sequence pattern defined as the maximum optimal width was selected 200, with a motif limit of 10 (Bailey and Elkan, 1994; McLeay and Bailey, 2010; Bailey et al., 2015). The functions of the identified motifs were retrieved from the Conserved Domain Database (CDD) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi) (Marchler-Bauer et al., 2015).

2.4 Multiple sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis of LTPs

The evolutionary relatedness of the LTP protein family of chickpea with the LTPs characterized in A. thaliana, O. sativa, and M. truncatula was analyzed using the Molecular Evolutionary Genetic Analysis version X (MEGA X) (https://www.megasoftware.net/) software (Kumar et al., 2018). The LTP sequences from the reference organisms, A. thaliana, O. sativa, and M. truncatula, were retrieved from the UniProt database (https://www.uniprot.org/) (The UniProt Consortium, 2021). The multiple sequence alignment (MSA) of all the sequences was performed by the ClustalW method in MEGA X. Maximum Likelihood (ML) method of tree construction was employed to construct the evolutionary tree, with 1,000 bootstraps per replication, which was visualized using an online tool, Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v6.3 (https://itol.embl.de/) (Letunic and Bork, 2021).

2.5 Gene duplication and ka/ks value calculation of LTPs

The Multiple Collinearity Scan Toolkit (MCScanX) was used to analyse the homologous gene pairs in the identified CaLTPs within the C. arietinum genome, as well as their orthologous relationship with the genes of A. thaliana, O. sativa, and M. truncatula that have evolved due to duplication (Wang et al., 2012). The top five hits of an all-versus-all local BLAST search for the protein sequences of the aforementioned species were utilised as input in MCScanX to acquire data on collinear pairs of genes. The CIRCOS software package was also utilised to map the identified duplicated gene pairs using the collinearity file obtained (Krzywinski et al., 2009). The selection pressure of the CaLTPs was evaluated by finding the ratio of synonymous (Ks) and nonsynonymous (Ka) substitutions for each duplication using the PAL2NAL web server (http://www.bork.embl.de/pal2nal/) (Suyama et al., 2006). A pairwise alignment result for each duplicated gene pair and their CDS sequences was used as an input in the software.

2.6 Gene-ontology-based functional annotation of CaLTPs

The functional characterization of the LTP gene family of chickpea was performed using the functional analysis module of OmicsBox https://www.biobam.com/omicsbox/). Blast2GO, InterPro, and EggNOG plugins were used to perform gene-ontology-based functional characterization of the LTP gene family of chickpea (Conesa et al., 2005; Conesa and Götz, 2008).

2.7 Identification of microRNA (miRNA) targets of CaLTPs

An online plant small RNA analysis server, psRNATarget was used to predict possible miRNA sequences that can bind with the CaLTPs (Dai et al., 2018). The CDS sequence of the CaLTPs was used as the target and scoring schema V1 was used to perform the analysis with expectation value set at 3 and other default parameters.

2.8 Growth of chickpea and maintenance of H. armigera culture

The methodology employed by Armes et al. (1992), Singh et al. (2008), Singh et al. (2017), and Keshan et al. (2021), for the growth of chickpea plants and the H. armigera culture, were used for this study as well (Armes et al., 1992; Singh et al., 2008; Singh et al., 2017; Keshan et al., 2021). Briefly, the chickpea seeds (Pusa 362) were washed and soaked overnight. The soaked seeds were transferred to the sterilized soilrite containing pots. The seeds were allowed to germinate and seedlings were grown in a plant growth chamber under controlled conditions (photoperiod: 16 h light and 8 h dark; temperature: 26–27°C; humidity: 55%–60%) and watered regularly. For rearing and maintenance of H. armigera, the larvae were procured from ICAR–National Bureau Of Agricultural Insect Resources, Bangalore, India, and reared in the laboratory on chickpea -fluor based artificial diet using standard protocols at 27°C and 65%–70% relative humidity on a 14/10 h light/dark cycle (Armes et al., 1992; Singh et al., 2008). The freshly molted fifth instar larvae (one of the most active and infesting stage) were starved for 12 h before releasing them on plants for experimentation and bioassays.

For infestation, the fifth-instar larvae were allowed to starve overnight and exposed to one-month-old chickpea plants (one larva per plant). The infestation by the larvae was allowed until 20% of the infestation was achieved. Plants without any treatments served as control. The whole shoot of treated and control samples were collected, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C.

2.9 Isolation of total RNA and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was isolated from the leaf tissues using TRIzolTM Reagent (Invitrogen, USA), as per the instructions from the manufacturer, and the quality and quantity of the RNA were checked as per previously published articles (Singh et al., 2017; Singh et al., 2018b). The cDNA was synthesized using 1 μg of RNA using the cDNA synthesis kit (script select cDNA synthesis kit, Bio-rad).

2.10 Relative gene expression of MeJA-responsive CaLTPs

From the promoter analysis of the putative chickpea LTPs, 21 LTPs were found to have motifs for MeJA responsiveness. Primers were designed for these 20 CaLTPs (Supplementary Table S6) having MeJA responsiveness as well as for the internal control genes (actin), using the web tool, Primer3 v. 0.4.0 (https://bioinfo.ut.ee/primer3-0.4.0/), with conditions such as primer size, primer Tm, primer GC%, and product size ranging from 18–23 bp, 60°C–62°C, 40%–70%, and 150–200 bp, respectively, and the maximum poly-X as 3 (Koressaar and Remm, 2007; Untergasser et al., 2012; Kõressaar et al., 2018). The quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed to check the relative expression of the CaLTPs in reference to the internal control genes using the SYBR Green Master Mix (Biorad) on ABI step one Real-time (Applied Biosystems). The real-time data obtained was then used for determining ∆Ct, ∆∆Ct, and RQ values. The relative expression values were statistically analyzed using ANOVA and Student’s t-test.

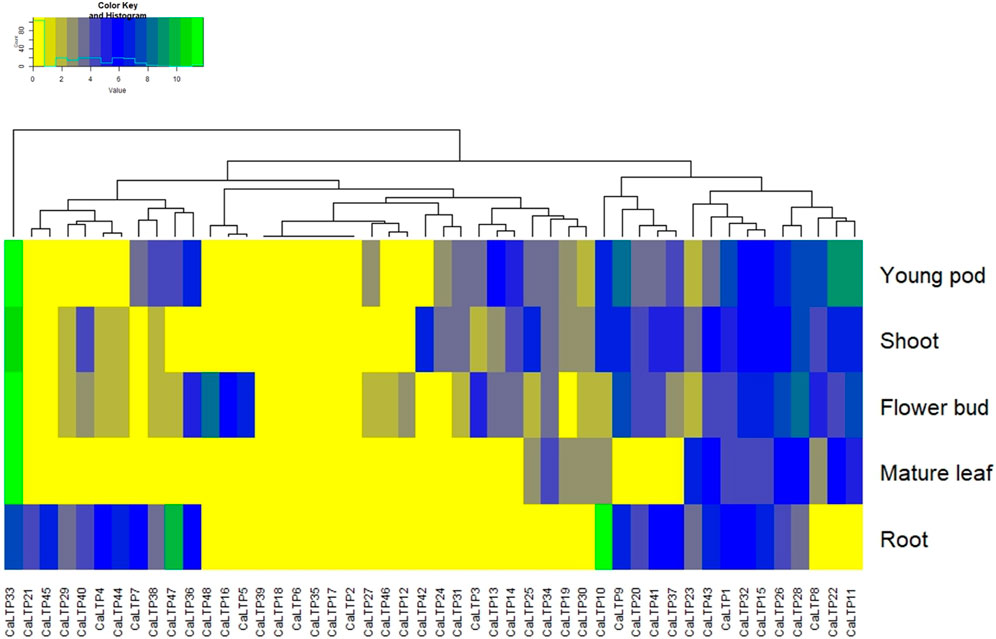

2.11 Tissue-specific expression analysis

To access the tissue-specific expression, Chickpea Transcriptome Database (CTDB) (http://www.nipgr.res.in/ctdb.html) was used to retrieve the identifiers for each of the 48 CaLTPs and RNAseq data corresponding to the differential expression in root, shoot, flower bud, mature leaf, and young pod was retrieved for each of the CaLTP [Reads/Kb/Million (RPKM) normalized data] (Verma et al., 2015). The heatmap.2 function from the ggplot2 package of RStudio was used to generate the heatmap (R Studio, 2020).

3 Results

3.1 Identification, characterization, and localization of CaLTPs

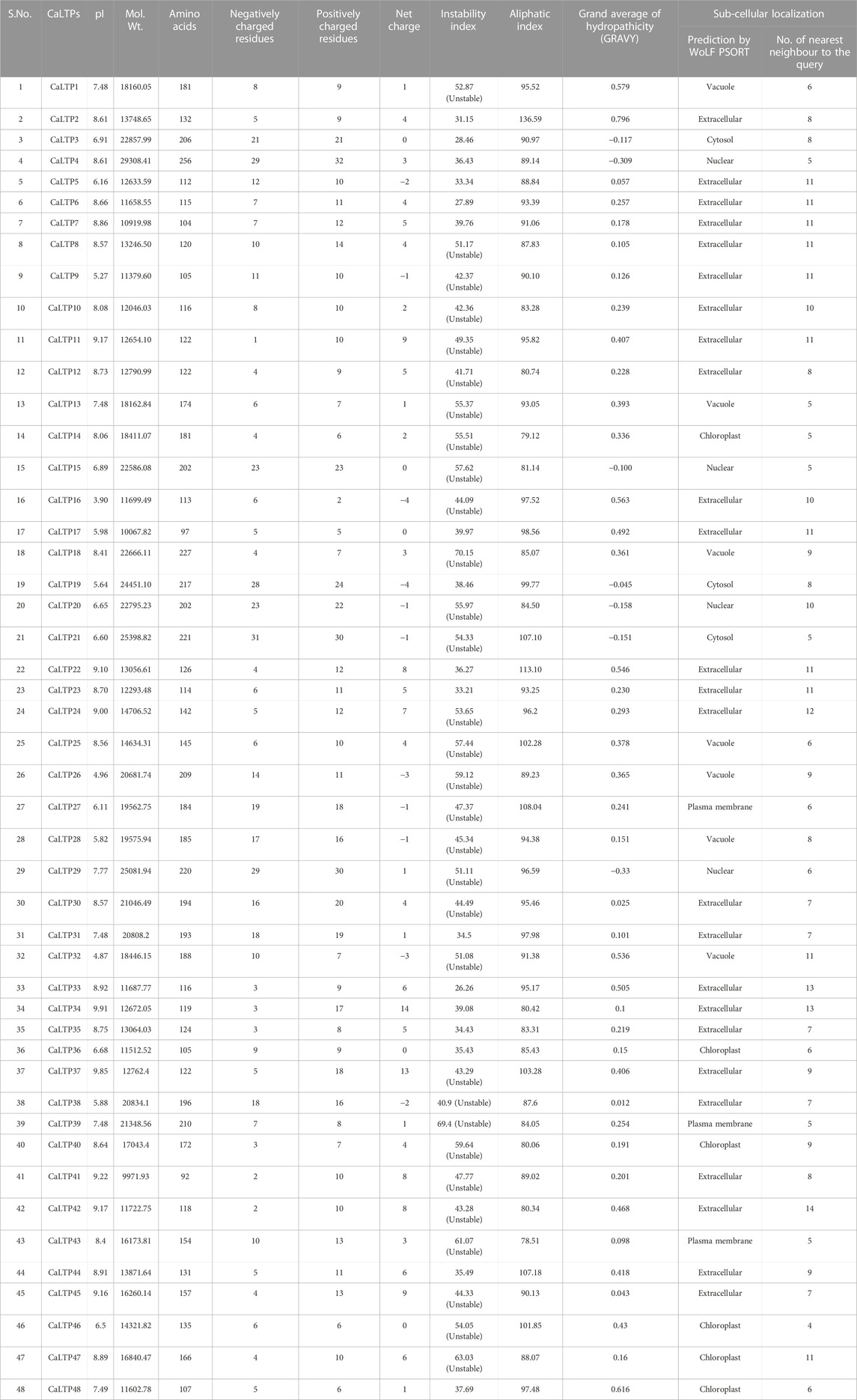

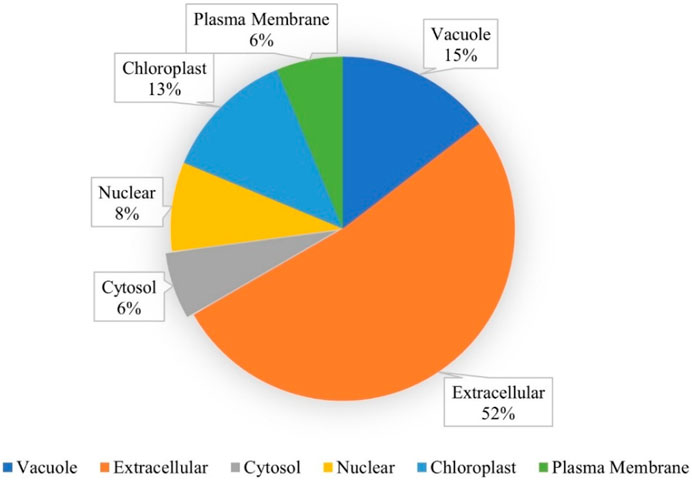

A total of 48 lipid transfer proteins (LTPs) were identified in the chickpea genome using in silico analysis (HMM profiles, HMMER scan and homology search; Supplementary Figures S1, S2). These 48 LTPs were given appropriate nomenclature from CaLTP1 to CaLTP48 (Supplementary Table S1), based on their location on the chickpea chromosomes, deciphered using the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) (Bethesda, 1988) (Table 1). Evaluation of their physiochemical properties revealed that the number of amino acids ranged from 92 to 256 with the molecular weight ranging from 9971.93 to 29308.41 Da. Their pI varied from 3.9 to 9.91 and 31 out of 48 proteins were predicted as unstable because their instability index was greater than 40. The aliphatic index of side chains varied from 78.51 to 136.59 and the GRAVY values indicated the hydrophilicity of the proteins as the values were found to be <0. Sub-cellular localization performed via WolfPSORT indicated that the proteins majorly translocated in the extracellular region which suggested their roles in lipid transport between membrane bilayers (Table 1; Figure 1)

TABLE 1. Physicochemical properties (pI, molecular weight, number of amino acids, number of negatively and positively charged residues, net charge, instability and aliphatic indices, GRAVY) and subcellular localization of the 48 CaLTPs.

FIGURE 1. Subcellular localization of the CaLTPs using WolfPSORT, showing 52, 15, 13, 8, 6, and 6 percent of CaLTPs localized in the extracellular membranes, vacuole, chloroplast, nuclear, cytosol, and plasma membranes, respectively.

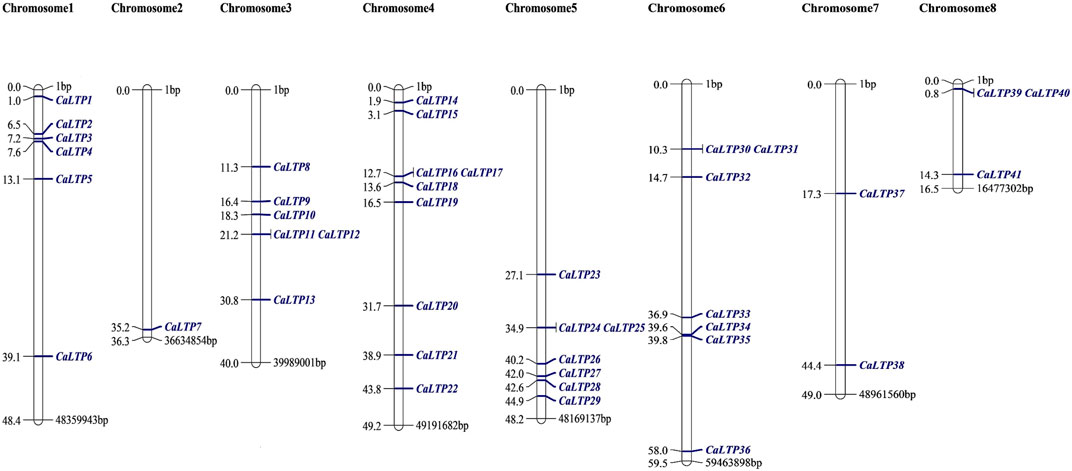

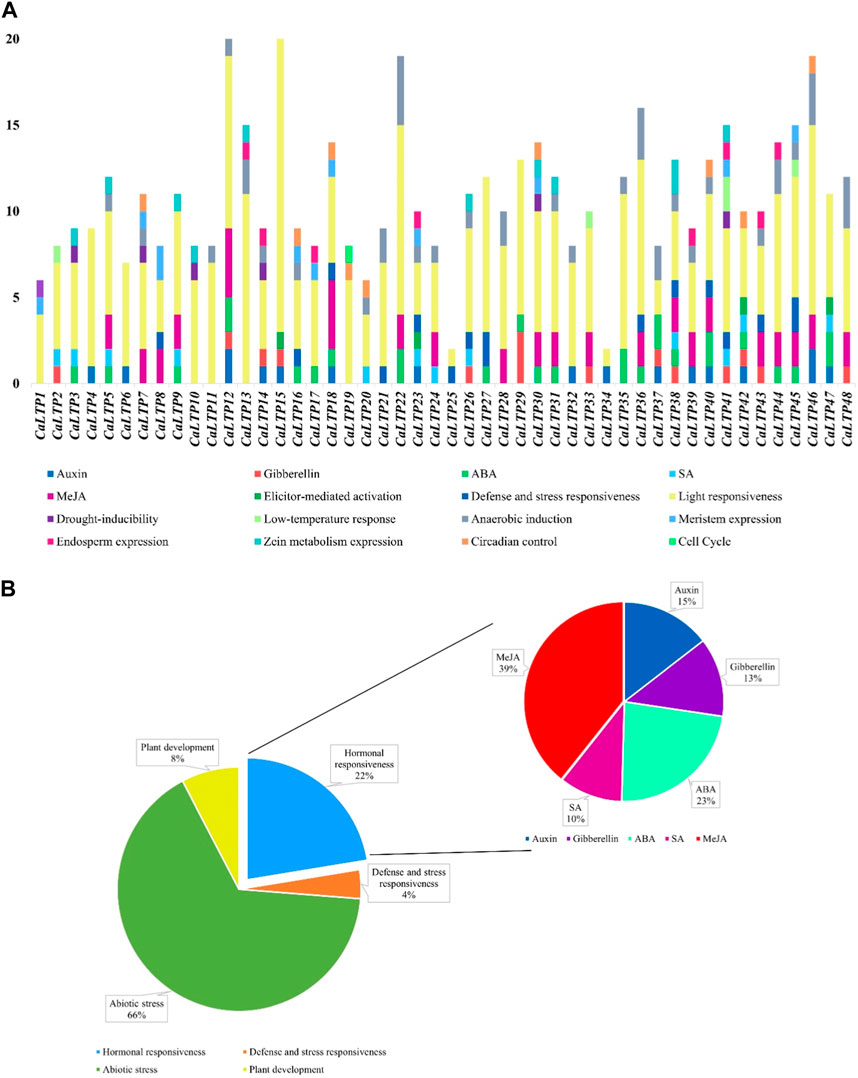

3.2 Chromosomal localization and promoter analysis

The 48 CaLTPs were seen to be localized on all eight chromosomes (haploid) of C. arietinum with the highest number of LTPs located on chromosome 4 (Figure 2). Most of the genes were present on the distal end of the chromosome suggesting their frequent involvement in the recombination process and might have high recombination frequency, indicating the potential causes of functional divergence of CaLTPs. The genes allocated at the proximal end of the chromosomes are highly unlikely to undergo recombination. Promoter analysis identified many cis-acting elements having roles in hormonal responsiveness, defense and stress responsiveness, abiotic stress, and plant development. Most of the CaLTPs transcription elements (about 66%) had roles in abiotic stress responses such as light responsiveness, drought-inducibility, low-temperature response, and anaerobic induction (Figure 3A; Supplementary Figure S3; Supplementary Table S2). Very few (∼8%) CaLTPs had promoter elements that contributed toward plant development. About 22% of the promoter elements showed hormonal responsiveness towards auxin, gibberellin, ABA, SA, and MeJA. It was also interesting to note that out of all the CaLTPs, 20 CaLTPs’ promoter sequences had elements responsive towards MeJA (Figure 3B). This is suggestive of the participation of CaLTPs in defense responses against herbivory and insect attacks by initiating the MeJA-induced defense mechanism.

FIGURE 2. Mapping of the 48 CaLTPs on the eight chickpea chromosomes using MapChart software. The CaLTPs are depicted using blue font (right side of each chromosome), and their exact position on the chromosome (in base pairs, bp) is mentioned next to each LTP (left side of each chromosome).

FIGURE 3. Promoter analysis of the CaLTPs. (A) Different promoter elements in CaLTPs and their role in different responses; (B) Pie chart depicting some LTPs participating in external responses and plant developmental process, emphasizing the roles in hormonal responsiveness.

3.3 Structural analysis and motif arrangement

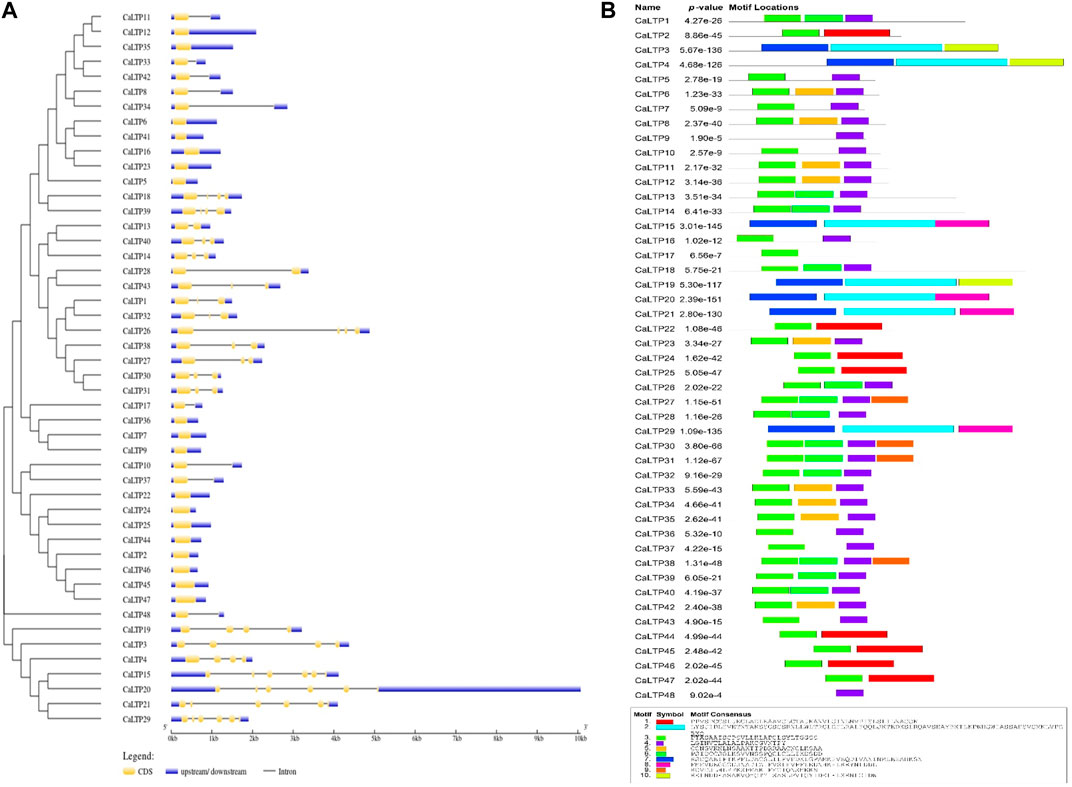

The distribution pattern of the exons and introns and their positions in the respective genes were analyzed using the GSDS server (Figure 4A). The maximum number of exons was found in CaLTP 12 and 29. No introns were found in 18 out of 48 CaLTPs. More than half of the LTPs had three or fewer introns and with 5 introns as the maximum number. This array of exons and introns helps to stipulate the structural, functional, and evolutionary features of the genes. Furthermore, the MEME suite helped to discover the ten novel conserved motifs for the 48 CaLTP genes (Figure 4B). The identified motifs were associated with the AAI_LTSS and GLTP superfamily and showed major involvement in the lipid transfer activity. The width of the novel motifs ranged from 21 to 85 amino acids. Motifs 3 and 4 were present in almost all the 48 CaLTPs and may correspond to the core LTP domain responsible for intermembrane lipid transfer activity. Motif 10 was present only in CaLTP 3, 4, and 19 while motifs 9 and 8 were found in CaLTP 30, 31, 27, 38, and CaLTP 15, 20, 29, and 21, respectively, suggesting that these three motifs might have some role exclusive to the protein they are present in. It was interesting to note that Motif 7 was only present in the CaLTPs (CaLTP 3,4,15,19,20,21, and 29), which had either motif 10 or motif 8 suggesting a hallmark linkage between the motifs (Supplementary Figure S4; Supplementary Table S3).

FIGURE 4. Gene structure and motif analyses. (A) The distribution patterns of exons and introns in the LTP gene family of chickpea were assessed using the GSDS server. Blue, yellow, and black colors, respectively represent the upstream/downstream, exons and introns (B) The presence of 10 novel conserved motifs in the CaLTPs was analyzed using the MEME suite.

3.4 Phylogenetic relatedness amongst CaLTPs and LTPs from model plants

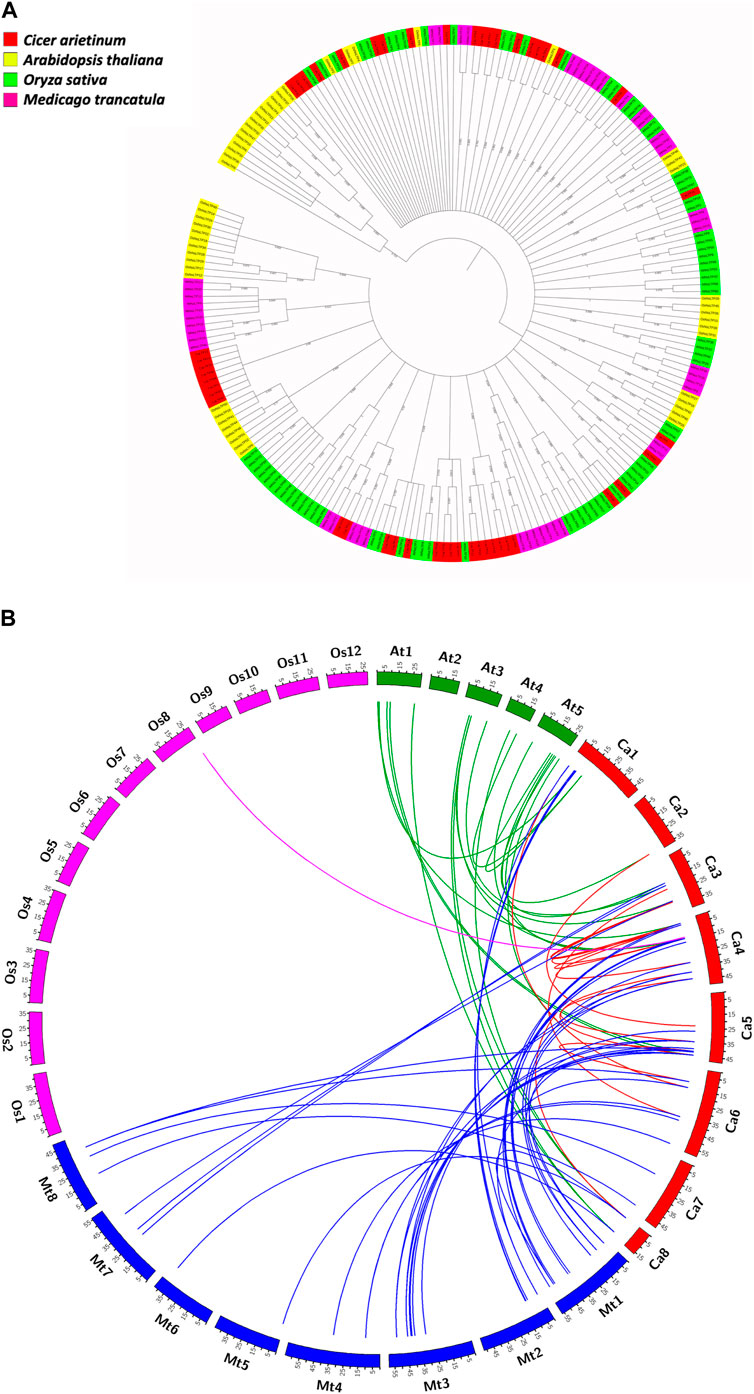

The evolutionary relationships of the LTP gene family in C. arietinum were studied with those in model dicots A. thaliana and M. truncatula, and model monocot O. sativa, by constructing a phylogenetic tree (Figure 5A). The results indicate that the LTPs have evolved significantly over a period of time, which is evident from different clades in the tree, suggesting the diverse roles of LTPs in the different plant systems. Out of 48 CaLTPs, 18 LTPs were found to occur in two clades next to each other, depicting relatedness amongst each other and no signs of functional divergence or relatedness with LTPs from reference organisms. The remaining LTPs were dispersed throughout the phylogenetic tree and were part of different clades sharing evolutionary relationships with the LTPs from A. thaliana and M. truncatula. The LTPs from O. sativa were present in distinct clades showing no signs of evolutionary relatedness with the chickpea LTPs.

FIGURE 5. Evolutionary studies of CaLTPs. (A) The phylogenetic tree depicting the evolutionary relatedness of the LTP gene family in chickpea to those in the reference plant systems like Arabidopsis thaliana, Oryza sativa, and Medicago truncatula. (B) Segmentally duplicated LTP pairs between C. arietinum (red) and Arabidopsis thaliana (green); C. arietinum (red) and Medicago trancatula (blue); C. arietinum (red) and Oryza sativa (pink).

3.5 Occurrence of gene duplication in LTPs and ka/ks value calculation

Gene duplication events play an essential role in expanding gene families leading to species divergence and evolving novel gene functions through subfunctionalization and neofunctionalization (Innan and Kondrashov, 2010). Analyzing the occurrence of gene duplication events within the C. arietinum genomes showed that a total of 16 pairs of genes underwent duplication, with four tandem duplication events, where the duplicated pairs were found on the same chromosome; 12 segmental duplication events, where the duplicated genes were present on different chromosomes (Supplementary Table S1B). Interestingly, all the tandemly duplicated gene pairs were present on chromosome 4. A comparative genome mapping of CaLTPs with genes from A. thaliana, O. sativa, and M. truncatula was also analyzed to show an orthologous relationship of the CaLTPs with genes from these species (Figure 5B). A total of 67 pairs of orthologous duplicated genes were identified, including 23 pairs between CaLTPs and the genes of A. thaliana, 43 pairs between CaLTPs and the genes of M. truncatula, and one pair between CaLTPs and O. sativa. The CaLTPs showed a maximum synteny with M. truncatula genes (34 CaLTPs), followed by A. thaliana (18 genes). In contrast, only one gene, CaLTP17, was found to have an orthologous relationship with genes from O. sativa. The results indicate that most of the CaLTPs have evolved due to gene duplication events, but a few might have been present earlier. To determine the selection pressure involved in the duplication and divergence of LTPs, the non-homologous (Ka) and synonymous (Ks) substitution rates of duplicated gene pairs (paralogous as well as orthologous gene pairs) were determined. Within the C. arietinum genome, the ratio of Ka/Ks for segmentally duplicated gene pairs ranged from 0.0934 to 0.4396 (with an average of 0.21), whereas tandemly duplicated genes had an average range of 0.086. In all paralogous duplicated gene pairs, the Ka/Ks ratio varied from 0.0064 to 0.817, with an average of 0.25. All homologous pairs of genes were found to have a Ka/Ks ratio smaller than 1, indicating that the duplicated genes were subjected to purifying selection during evolution (Kondrashov et al., 2002).

3.6 GO-based functional annotation of CaLTPs

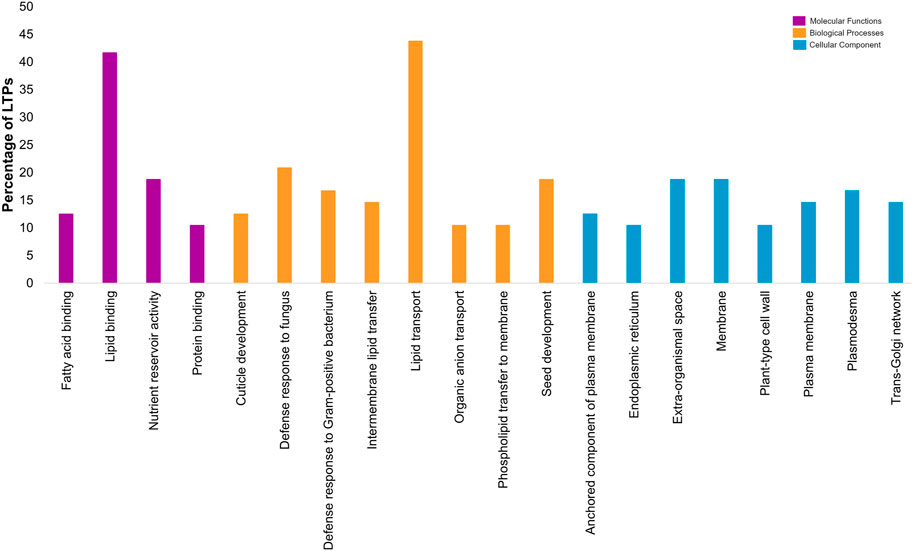

Gene ontology-based functional annotation uncovered the roles of CaLTPs in various components like molecular functions, biological processes, and cellular components. A majority of CaLTPs took part in biological processes and molecular functions related to lipid transport (GO:0006869) and lipid binding (GO:0008289), respectively. It was interesting to note that apart from lipid transport, CaLTP genes also participated in the biological processes such as defense response to fungus (GO:0050832), seed development (GO:0048316) and defense response to Gram-positive bacteria (GO:0050830) to name a few. They also took part in molecular functions such as nutrient reservoir activity (GO:0045735), fatty acid binding (GO:0005504), protein binding (GO:0005504). The cellular component occupied by most of the LTPs were membrane (GO:0005886), extra-organismal space (GO:0043245), and plasmodesmata (GO:0009506) (Figure 6; Supplementary Table S5).

FIGURE 6. Gene-ontology-based functional annotation of the LTP gene family of chickpea, with diverse roles in Molecular functions, Biological processes and Cellular component.

3.7 miRNA targets prediction for CaLTPs

With the default parameters and expectation value of ≤3, psRNATarget could predict 51 miRNAs that can potentially bind with the CaLTPs (Supplementary Table S7). The search was optimized with the expectation value (measure of similarity and the possibility for the mismatches between mature small RNA and the target sequence) and UPE (maximum energy to unpair the target site) value of 2 and 19.377 respectively.

3.8 Effect of H.armigera-infestation on the expression profiles of CaLTPs

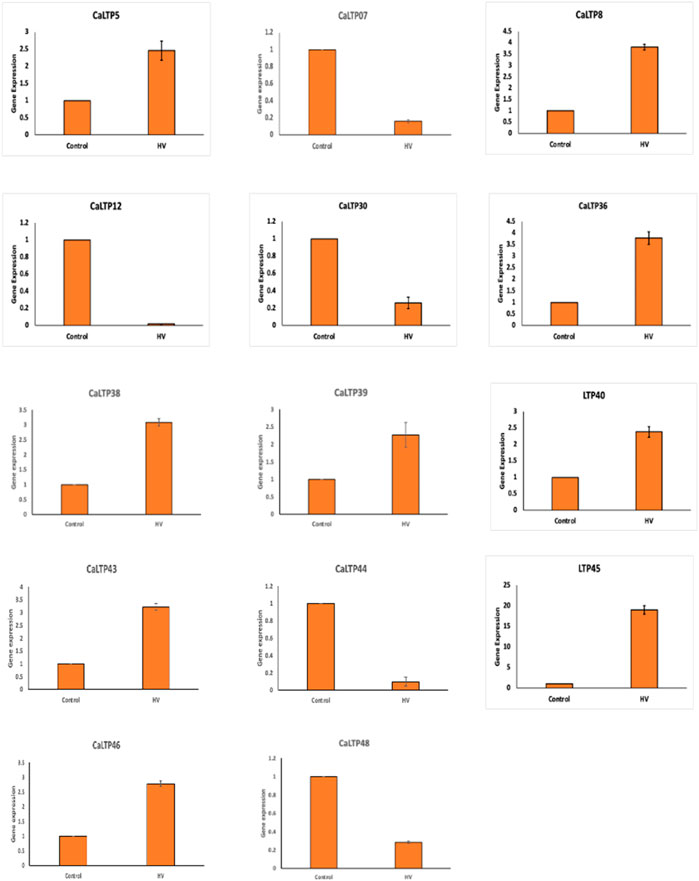

A total of 20 CaLTPs that showed MeJA responsiveness, were used for studying the relative gene expression when infested with H. armigera. Specific primers were designed to study the real-time expression of the 20 CaLTPs, where actin was used as the internal control (Figure 7). A positive fold-change was observed for 9 of the CaLTPs (CaLTP 5, 8, 36, 38, 39, 40, 43, 45, and 46) whereas 5 of the CaLTPs (CaLTP 7, 12, 30, 44, and 48) were downregulated during H. armigera-infestation and the rest of them did not alter their expression significantly. CaLTP45 showed approximately 5-fold upregulation followed by CaLTP 8 and 36. The upregulated expression pattern for the remaining CaLTPs ranged from 1.5 to 2-fold in response to H. armigera-infestation.

FIGURE 7. The qRT-PCR expression pattern of CaLTPs during H. armigera -infestation. Actin was used as the internal control gene. Triplicate set of data were used for each experiment. The statistical analysis was conducted using AVOVA and Student’s T-tests. The data are plotted as means ± s.d. The error bars represent standard deviations.

3.9 Tissue-specific gene expression profile of CaLTPs

Expression analysis was performed to study the differential expression of CaLTPs in the root, shoot, flower bud, mature leaf, and young pod (Figure 8). The differential expression values were estimated as Reads/Kb/Million (RPKM) values and the heatmap was created with log2 normalized data. It was observed that CaLTP33 was highly expressed in all the tissue types except the roots. CaLTP10 was found to be highly expressed whereas CaLTP47 was expressed mildly in the roots. CaLTP 9, 11, 22, and 33 had higher expression in the young pods. CaLTP 28, 33, and 48 were found to be expressed in the flower buds. Contrastingly, most of the CaLTP genes either showed no expression or exhibited very low levels of expression in the vegetative and reproductive tissues.

FIGURE 8. Representation of the gene expression levels of 48 CaLTPs in vegetative and reproductive tissues (shoot, root, mature leaf, flower bud, and young pod) in the form of a heat map.

4 Discussion

C. arietinum L., commonly known as chickpea, is widely grown and the second-largest consumed legume in the world. Asia accounts for 89.7% area under cultivation followed by Africa (4.3% area) and occurs as the largest producer in the world (Varshney et al., 2013). However, chickpea faces tremendous pre- and post-harvest damages due to several biotic and abiotic stresses. Among biotic stresses, the damage caused due to insect attacks accounts for 18%–50% of the yield loss (Pandey et al., 2017). Amongst several insects that affect chickpea’s growth and productivity, the pod borer, H. armigera is a voracious pest causing a notable decline in the yield and leading to severe economic losses (Romeis et al., 2004). To prevent this, using pesticides is an effective approach but it harms the environment. With the advancement of techniques used to enhance agricultural productivity, researchers have started looking for solutions at the molecular and genetic levels. Thus, the mechanisms underlying the plant-insect interactions are intriguing as it includes identifying the genes that regulate specific responses against herbivory, their expression, and their mode of action. One such gene family which has been known to have functions in plant defense against pests is the non-specific Lipid Transfer Proteins (LTPs); one of the members of the LTP family is reported to be upregulated during H. armigera -infestation. Even though it has been a hub for new research in many plants such as Arabidopsis, rice, wheat and so on over the past few decades, very little is known about its role in chickpea.

This study encompasses genome-wide identification and characterization of LTPs which were upregulated in C. arietinum upon H. armigera -infestation. Forty-eight LTPs were identified using in silico analysis, and have been structurally and functionally characterized during this study. The assessment of their physiochemical properties revealed the unstable and hydrophilic nature of the LTPs. The subcellular localization of the LTPs suggested that they were localized in extracellular spaces, vacuole, and chloroplast while few were localized in the cytosol, nucleus, and plasma membrane. This coincides with the studies, which show that LTPs are localized in exterior spaces to the plasma membrane (Chou et al., 2006). Furthermore, we attempted to find the locations of these 48 LTPs in the chickpea genome and discovered that the genes were dispersed unevenly on the eight chickpea chromosomes. Most of the genes were present at the distal ends of the chromosomes, which is suggestive of causing divergence of LTPs with each other and with respect to other plant species as well (Bulger and Groudine, 2011).

The promotor analysis of the LTP family disclosed promoter elements or motifs specific to LTPs have multifarious roles in hormonal regulation, defense and stress mechanisms, and abiotic stress responses. Interestingly, the cis-regulatory elements for light responsiveness were common to all the LTPs, and about 65% of the LTPs were found to have MeJA-responsive cis-regulatory elements. The presence of MeJA motifs gave the impression of LTPs contributing to plant innate immunity and phytohormone pathways. There have been previous reports that endorse the fact that LTPs are regulated during plant stress, hormonal signaling, and plant development, and thus, similar roles of CaLTPs stipulate the presence of conserved domains for plant defense mechanisms (Wei and Zhong, 2014; Finkina et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2021). The arrangement of introns and exons of CaLTPs gave insights into the structural attributes of the 48 genes, such that the introns ranged from 0 to 5 in number, with a greater stretch of exons or CDS sequences in the genes. Since introns in eukaryotic genes contributes to evolutionary advantage, fewer introns in LTPs suggested low evolutionary conservation (Gorlova et al., 2014). Moreover, genes with fewer introns are likely to be induced faster in response to external stimuli (Heidari et al., 2022). The identification of 10 novel motifs provided information on the motifs that were common to a majority of the chickpea LTPs and the motifs that were linked to each other. Functional annotation of these motifs divulged their involvement in stress responses and lipid transport activities. Thus, the conserved motifs and gene structure of the CaLTPs shared a noteworthy similarity which is suggestive of higher conservation. In addition, CaLTPs were annotated using GO terms under molecular functions, biological processes, and cellular component, categories, suggesting the putative roles of the LTPs in lipid binding and plant defense majorly and localization in the extracellular spaces. Initially LTPs were only associated with inter-membrane lipid transport, yet further studies confirmed their role in defense against biotic and abiotic stress.

Understanding the evolutionary pattern is crucial for the reasons behind the diverse roles exhibited by a gene or a gene family. Phylogenetic analyses of the 48 LTPs with the LTP families of model organisms, namely, A. thaliana, M. truncatula, and O. sativa, manifested a close relationship of CaLTPs with LTPs from A. thaliana and M. truncatula. This indicates that LTPs from chickpea are orthologous to those from A. thaliana and M. truncatula, which may have diverged during speciation events during the evolutionary timeline. Interestingly, the LTP family of rice (a monocot) showed peculiarity in the phylogenetic tree as they were present as distinct clusters with no significant relatedness with any of the CaLTPs and rare instances of relatedness with LTPs from A. thaliana and M. truncatula, providing strong evidence of evolutionary divergence.

The gene duplication analysis of the CaLTPs suggested that both tandem and segmental duplication might have played an important role in the evolution and expansion of the LTP family. Further, decrease in the number of orthologous genes between C. arietinum-M. truncatula (∼70%), -A. thaliana (∼37%), and -O. sativa (∼2%) revealed the close relationship of chickpea with other dicots, while having least relatedness with genes from O. sativa. This analysis also supports the results of phylogenetic analysis that CaLTPs evolved independently of LTPs from O. sativa, forming a separate clade. The ratio of synonymous and non-synonymous mutations in duplicated gene pairs, or Ka/Ks, revealed the selection pressure on a gene or protein. All of the duplicated gene pairs had a Ka/Ks ratio value of less than 1, indicating that the CaLTP genes had undergone purifying selection during the course of evolution, eliminating any harmful alleles (Kondrashov et al., 2002).

The gene expression patterns delineated by RNA-Seq of CaLTPs in different tissues such as root, shoot, leaf, pod, and flower buds, yielded profiles showing variation in the expression patterns in vegetative and reproductive tissues, indicating their role in overall growth and development of respective tissue type. However, many of the CaLTPs exhibited very low/no expression in different tissue, indicating their role in other processes. The changes at the transcript level during insect herbivory on plants have been extensively studied in several plant systems, such as A. thaliana, Solanum lycopersicum, Nicotiana attenuata, Gossypium sp., and so on, which elucidate the complex changes in the expression patterns in signaling and hormonal pathways in response to herbivory. Additionally, gene families involved in MAPK pathway (MAPK, MAPKK, MAPKKK) of chickpea were also investigated, showing the involvement of MAPK pathway in signaling during plant defense against H. armigera (Singh et al., 2017; Keshan et al., 2021). In this study, the relative expression patterns of MeJA-regulated LTPs were evaluated, which showed their responsiveness towards MeJA and herbivory (Pandey et al., 2017). Interestingly, a positive fold change was observed for 9 of the CaLTPs, whereas 5 of the CaLTPs were downregulated during H. armigera-infestation, suggesting differential expression of CaLTPs during the H. armigera -infestation. Our results supports the notion that LTPs are involved in lipid signalling and plant defense against H. armigera-infestation.

5 Conclusion

The H. armigera-infestation on chickpea leads to a surfeit of changes at molecular and biochemical levels. Alteration in the transcript level of defense-related genes such as lipid transfer proteins (LTPs) is one such consequence observed during the attack and is the basis of this genome-wide analysis. We speculate a significant contribution of the LTP family of chickpea in plant defense responses and its primary role in lipid transfer activity. Identifying and characterizing 48 CaLTPs helped to dissect the genetic expansion, evolution, distribution, and gene expression patterns of these proteins in chickpea. Motif analysis and GO-based annotation highlighted the functional importance of LTPs in various stress responses and plant developmental processes. Differential expression of 14 CaLTPs during H. armigera-infestation indicated their role in plant defense. This evaluation will not only serve as a fundamental point for further elucidation and validation of functions of LTPs in chickpea and legumes per se but will also provide a platform for studying the stress-related pathways and mechanisms with special emphasis on herbivory.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

AS and IS conceptualized and supervised the study. AS, HS, and HN designed the methodology, and HS, HN, PC, and RK, performed the experiments, collected the data and analysed the results. AS, HS, PC, and HN wrote the manuscript. AS, IS, SK, AC, and AR critically reviewed the manuscript. AS, IS, SK, AC, and AR contributed to editing and visualization. AS, IS, and AR contributed to the formal analysis. AS and AR contributed to Funding acquisition. AS and IS contributed to resources. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

Financial support was provided to AS by the Science and Engineering Research Board (SERB), Department of Science and Technology, New Delhi, India (ECR/2017/002478). AR, AC, financed by EVA 4.0, No. CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/16019/0000803 and “EXTEMIT–K,” No. CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/15_003/0000433 financed by OP RDE. AR and AC are also supported by “Excellent team grants (2023–24)” from FLD, CZU.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Prof. (Dr.) Rama, Principal, Hansraj College, for providing the facilities and her constant support for research work.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgene.2023.1195554/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

C, degree Celsius; µg, microgram; ABA, Abscisic Acid; bp, base pairs; CDD, Conserved Domains Database; cDNA, complementary Deoxyribonucleic Acid; CDS, Coding Sequence; Ct, Cycle threshold; CTDB, Chickpea Transcriptome Database; Da, Dalton; GO, Gene Ontology; GRAVY, GRand Average of hYdropathicity; GSDS, Gene Structure Display Server; iTOL, interactive Tree Of Life, LTP, Lipid Transfer Proteins; MEGA, Molecular Evolutionary Genetic Analysis; MeJA, Methyl Jasmonate; ML, Maximum Likelihood; MSA, Multiple Sequence Alignment; NCBI, National Center for Biotechnology Information; pI, Isoelectric point; qRT-PCR, quantitative Real Time-Polymerase Chain Reaction; RNA, Ribonucleic Acid; RQ, Relative Quantification; SA, Salicylic Acid; TAIR, The Arabidopsis Information Resource; TIGR, The Institute for Genomic Research; Tm, melting Temperature.

References

Adhikari, P. B., Han, J. Y., Ahn, C. H., and Choi, Y. E. (2019). Lipid transfer proteins (AaLTP3 and AaLTP4) are involved in sesquiterpene lactone secretion from glandular trichomes in Artemisia annua. Plant Cell. Physiology 60, 2826–2836. doi:10.1093/pcp/pcz171

Alhoraibi, H., Bigeard, J., Rayapuram, N., Colcombet, J., and Hirt, H. (2019). Plant immunity: The MTI-ETI model and beyond. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 30, 39–58. doi:10.21775/cimb.030.039

Armes, N. J., Jadhav, D. R., and King, A. B. S. (1992). Pyrethroid resistance in the pod borer, Helicoverpa armigera. Presented at the proceeding brighton crop protection conference — pests and diseases. Bracknel, UK, 239–244.

Arondel, V., and Kader, J.-C. (1990). Lipid transfer in plants. Experientia 46, 579–585. doi:10.1007/BF01939696

Bailey, T. L., and Elkan, C. (1994). Fitting a mixture model by expectation maximization to discover motifs. Biopolymer 9.

Bailey, T. L., Johnson, J., Grant, C. E., and Noble, W. S. (2015). The MEME suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, W39–W49. doi:10.1093/nar/gkv416

Barmukh, R., Roorkiwal, M., Jaba, J., Chitikineni, A., Mishra, S. P., Sagurthi, S. R., et al. (2021). Development of a dense genetic map and QTL analysis for pod borer Helicoverpa armigera (Hübner) resistance component traits in chickpea (Cicer arietinum L). Plant Genome 14 (1), e20071. doi:10.1002/tpg2.20071

Bethesda, M. (1988). National center for Biotechnology information (NCBI). [WWW Document]. URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/.

Boutrot, F., Chantret, N., and Gautier, M.-F. (2008). Genome-wide analysis of the rice and arabidopsis non-specific lipid transfer protein (nsLtp) gene families and identification of wheat nsLtp genes by EST data mining. BMC Genomics 9, 86. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-9-86

Bulger, M., and Groudine, M. (2011). Functional and mechanistic diversity of distal transcription enhancers. Cell. 144, 327–339. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.024

Carvalho, A. de O., and Gomes, V. M. (2007). Role of plant lipid transfer proteins in plant cell physiology—a concise review. Peptides 28, 1144–1153. doi:10.1016/j.peptides.2007.03.004

Choi, A. M., Lee, S. B., Cho, S. H., Hwang, I., Hur, C.-G., and Suh, M. C. (2008). Isolation and characterization of multiple abundant lipid transfer protein isoforms in developing sesame (Sesamum indicum L) seeds. Plant Physiology Biochem. 46, 127–139. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2007.10.003

Chou, M.-X., Wei, X.-Y., Chen, D.-S., and Zhou, J.-C. (2006). Thirteen nodule-specific or nodule-enhanced genes encoding products homologous to cysteine cluster proteins or plant lipid transfer proteins are identified in Astragalus sinicus L. by suppressive subtractive hybridization. J. Exp. Bot. 57, 2673–2685. doi:10.1093/jxb/erl030

Conesa, A., and Götz, S. (2008). Blast2GO: A comprehensive suite for functional analysis in plant genomics. Int. J. Plant Genomics 2008, 619832. doi:10.1155/2008/619832

Conesa, A., Götz, S., García-Gómez, J. M., Terol, J., Talón, M., and Robles, M. (2005). Blast2GO: A universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics 21, 3674–3676. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bti610

Dai, X., Zhuang, Z., and Zhao, P. X. (2018). psRNATarget: a plant small RNA target analysis server (2017 release). Nucleic Acids Res. 46, W49–W54. doi:10.1093/nar/gky316

del Carmen Ramírez-Medeles, M., Aguilar, M. B., Miguel, R. N., Bolaños-García, V. M., García-Hernández, E., and Soriano-García, M. (2003). Amino acid sequence, biochemical characterization, and comparative modeling of a nonspecific lipid transfer protein from Amaranthus hypochondriacus. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 415, 24–33. doi:10.1016/s0003-9861(03)00201-7

Dhaliwal, G. S., Jindal, V., and Mohindru, B. (2015). Crop losses due to insect pests: Global and Indian scenario. Ind. Jour. Entomol. 77, 165. doi:10.5958/0974-8172.2015.00033.4

Dinesh, K., Anusha, S., Singh, R. B., and Dangi, N. L. (2017). Estimation of avoidable yield losses caused by Helicoverpa armigera (Hubner) on chickpea. J. Entomology Zoology Stud. 5 (2), 1476–1478.

Duo, J., Xiong, H., Wu, X., Li, Y., Si, J., Zhang, C., et al. (2021). Genome-wide identification and expression profile under abiotic stress of the barley non-specific lipid transfer protein gene family and its Qingke Orthologues. BMC Genomics 22, 674. doi:10.1186/s12864-021-07958-8

Edqvist, J., Blomqvist, K., Nieuwland, J., and Salminen, T. A. (2018). Plant lipid transfer proteins: Are we finally closing in on the roles of these enigmatic proteins? J. Lipid Res. 59, 1374–1382. doi:10.1194/jlr.R083139

Finkina, E. I., Melnikova, D. N., Bogdanov, I. V., and Ovchinnikova, T. V. (2016). Lipid transfer proteins as components of the plant innate immune system: Structure, functions, and applications. Acta Naturae 8, 47–61. doi:10.32607/20758251-2016-8-2-47-61

García-Olmedo, F., Molina, A., Segura, A., and Moreno, M. (1995). The defensive role of nonspecific lipid-transfer proteins in plants. Trends Microbiol. 3, 72–74. doi:10.1016/s0966-842x(00)88879-4

Gorlova, O., Fedorov, A., Logothetis, C., Amos, C., and Gorlov, I. (2014). Genes with a large intronic burden show greater evolutionary conservation on the protein level. BMC Evol. Biol. 14, 50. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-14-50

Gowda, C. L. L., Ramesh, S., Chandra, S., and Upadhyaya, H. D. (2005). Genetic basis of pod borer (Helicoverpa armigera) resistance and grain yield in desi and Kabuli Chickpea (Cicer arietinum L) under unprotected conditions. Euphytica 145, 199–214. doi:10.1007/s10681-005-1165-7

Heidari, P., Puresmaeli, F., and Mora-Poblete, F. (2022). Genome-wide identification and molecular evolution of the magnesium transporter (MGT) gene family in Citrullus lanatus and Cucumis sativus. Agronomy 12, 2253. doi:10.3390/agronomy12102253

Horton, P., Park, K.-J., Obayashi, T., Fujita, N., Harada, H., Adams-Collier, C. J., et al. (2007). WoLF PSORT: Protein localization predictor. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W585–W587. doi:10.1093/nar/gkm259

Hu, B., Jin, J., Guo, A.-Y., Zhang, H., Luo, J., and Gao, G. (2015). Gsds 2.0: An upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics 31, 1296–1297. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btu817

Innan, H., and Kondrashov, F. (2010). The evolution of gene duplications: Classifying and distinguishing between models. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11 (2), 97–108. doi:10.1038/nrg2689

Jaiswal, P., Cheruku, J. R., Kumar, K., Yadav, S., Singh, A., Kumari, P., et al. (2012). Differential transcript accumulation in chickpea during early phases of compatible interaction with a neurotrophic fungus Ascochyta rabiei. Mol. Biol. Rep. 39, 4635–4646. doi:10.1007/s11033-011-1255-7

Kader, J. C. (1975). Proteins and the intracellular exchange of lipids: I. Stimulation of phospholipid exchange between mitochondria and microsomal fractions by proteins isolated from potato tuber. Biochimica Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Lipids Lipid Metabolism 380, 31–44. doi:10.1016/0005-2760(75)90042-9

Kader, J. C. (1996). LIPID-TRANSFER proteins in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant. Physiol. Plant. Mol. Biol. 47, 627–654. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.47.1.627

Kerchev, P. I., Fenton, B., Foyer, C. H., and Hancock, R. D. (2012). Plant responses to insect herbivory: Interactions between photosynthesis, reactive oxygen species and hormonal signalling pathways. Plant, Cell. & Environ. 35, 441–453. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02399.x

Keshan, R., RaginiSingh, I. K., and Singh, A. (2021). Genome wide investigation of MAPKKKs from Cicer arietinum and their involvement in plant defense against Helicoverpa armigera. Physiological Mol. Plant Pathology 115, 101685. doi:10.1016/j.pmpp.2021.101685

Kessler, A., and Baldwin, I. T. (2002). P lant R esponses to I nsect H erbivory: The emerging molecular analysis. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 53, 299–328. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.53.100301.135207

Khatodia, S., Bhatotia, K., and Behl, R. K. (2017). Helicoverpa resistant chickpea plants: From bt toxins to plant-mediated RNAi 9.

Kondrashov, F. A., Rogozin, I. B., Wolf, Y. I., and Koonin, E. V. (2002). Selection in the evolution of gene duplications. Genome Biol. 3, RESEARCH0008. doi:10.1186/gb-2002-3-2-research0008

Koressaar, T., and Remm, M. (2007). Enhancements and modifications of primer design program Primer3.

Kõressaar, T., Lepamets, M., Kaplinski, L., Raime, K., Andreson, R., and Remm, M. (2018). Primer3_masker: Integrating masking of template sequence with primer design software. Bioinformatics 34, 1937–1938. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bty036

Kristensen, A. K., Brunstedt, J., Nielsen, K. K., Roepstorff, P., and Mikkelsen, J. D. (2000). Characterization of a new antifungal non-specific lipid transfer protein (nsLTP) from sugar beet leaves. Plant Sci. 155, 31–40. doi:10.1016/S0168-9452(00)00190-4

Krzywinski, M., Schein, J., Birol, I., Connors, J., Gascoyne, R., Horsman, D., et al. (2009). Circos: An information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 19 (9), 1639–1645. doi:10.1101/gr.092759.109

Kumar, S., Stecher, G., Li, M., Knyaz, C., and Tamura, K. (2018). Mega X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 1547–1549. doi:10.1093/molbev/msy096

Kumar, A., Panwar, R., Singh, A., and Singh, I. K. (2020). “Role of calcium signalling during plant–herbivore interaction,” in Plant stress biology. Editors B. Giri, and M. P. Sharma (Singapore: Springer Singapore), 491–510. doi:10.1007/978-981-15-9380-2_16

Lescot, M., Déhais, P., Thijs, G., Marchal, K., Moreau, Y., Peer, Y., et al. (2002). PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 30–325. doi:10.1093/NAR/30.1.325

Letunic, I., and Bork, P. (2021). Interactive tree of Life (iTOL) v5: An online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, W293–W296. doi:10.1093/nar/gkab301

Li, G., Hou, M., Liu, Y., Pei, Y., Ye, M., Zhou, Y., et al. (2019). Genome-wide identification, characterization and expression analysis of the non-specific lipid transfer proteins in potato. BMC Genomics 20, 375. doi:10.1186/s12864-019-5698-x

Marchler-Bauer, A., Derbyshire, M. K., Gonzales, N. R., Lu, S., Chitsaz, F., Geer, L. Y., et al. (2015). Cdd: NCBI’s conserved domain database. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, D222–D226. doi:10.1093/nar/gku1221

McLeay, R. C., and Bailey, T. L. (2010). Motif enrichment analysis: A unified framework and an evaluation on ChIP data. BMC Bioinforma. 11, 165. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-11-165

Pandey, S. P., Srivastava, S., Goel, R., Lakhwani, D., Singh, P., Asif, M. H., et al. (2017). Simulated herbivory in chickpea causes rapid changes in defense pathways and hormonal transcription networks of JA/ethylene/GA/auxin within minutes of wounding. Sci. Rep. 7, 44729. doi:10.1038/srep44729

Rasool, S., Latef, A. A. H. A., and Ahmad, P. (2015). “Chickpea: Role and responses under abiotic and biotic stress,” in Legumes under environmental stress. Editors M. M. Azooz, and P. Ahmad (Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd), 67–79. doi:10.1002/9781118917091.ch4

Reyes-Díaz, M., Lobos, T., Cardemil, L., Nunes-Nesi, A., Retamales, J., Jaakola, L., et al. (2016). Methyl jasmonate: An alternative for improving the quality and health properties of fresh fruits. Molecules 21, 567. doi:10.3390/molecules21060567

Reymond, P., and Farmer, E. E. (1998). Jasmonate and salicylate as global signals for defense gene expression. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 1, 404–411. doi:10.1016/S1369-5266(98)80264-1

Romeis, J., Sharma, H. C., Sharma, K. K., Das, S., and Sarmah, B. K. (2004). The potential of transgenic chickpeas for pest control and possible effects on non-target arthropods. Crop Prot. 23, 923–938. doi:10.1016/j.cropro.2004.02.004

Salcedo, G., Sánchez-Monge, R., Barber, D., and Díaz-Perales, A. (2007). Plant non-specific lipid transfer proteins: An interface between plant defence and human allergy. Biochimica Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Mol. Cell. Biol. Lipids 1771, 781–791. doi:10.1016/j.bbalip.2007.01.001

Salminen, T. A., Blomqvist, K., and Edqvist, J. (2016). Lipid transfer proteins: Classification, nomenclature, structure, and function. Planta 244, 971–997. doi:10.1007/s00425-016-2585-4

Sanyal, I., Singh, A. K., Kaushik, M., and Amla, D. V. (2005). Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L) with Bacillus thuringiensis cry1Ac gene for resistance against pod borer insect Helicoverpa armigera. Plant Sci. 168 (4), 1135–1146. doi:10.1007/s12298-010-0030-x

Sarmah, B. K., Acharjee, S., and Sharma, H. C. (2012). “Chickpea: Crop improvement under changing environment conditions,” in Improving crop productivity in sustainable agriculture. Editors N. Tuteja, S. S. Gill, and R. Tuteja (Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA), 361–380. doi:10.1002/9783527665334.ch15

Sharma, S., Kooner, R., and Arora, R. (2017). “Insect pests and crop losses,” in Breeding insect resistant crops for sustainable agriculture. Editors R. Arora, and S. Sandhu (Singapore: Springer Singapore), 45–66. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-6056-4_2

Singh, A., Singh, I. K., and Verma, P. K. (2008). Differential transcript accumulation in Cicer arietinum L. in response to a chewing insect Helicoverpa armigera and defence regulators correlate with reduced insect performance. J. Exp. Bot. 59, 2379–2392. doi:10.1093/jxb/ern111

Singh, I. K., Kumar, S., Singh, S., and Singh, A. (2017). Expression profiling of mitogen-activated protein kinase genes from chickpea (Cicer arietinum L) in response to Helicoverpa armigera, wounding and signaling compounds. J. Asia-Pacific Entomology 20, 942–948. doi:10.1016/j.aspen.2017.07.003

Singh, A., Jain, D., Tyagi, C., Singh, S., Kumar, S., and Singh, I. K. (2018a). In silico prediction of active site and in vitro DNase and RNase activities of Helicoverpa-inducible pathogenesis related-4 protein from Cicer arietinum. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 113, 869–880. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.03.027

Singh, A., Nath, O., Singh, S., Kumar, S., and Singh, I. K. (2018b). Genome-wide identification of the MAPK gene family in chickpea and expression analysis during development and stress response. Plant gene. 13, 25–35. doi:10.1016/j.plgene.2017.12.001

Singh, A., Tyagi, C., Nath, O., and Singh, I. K. (2018c). Helicoverpa-inducible thioredoxin h from cicer arietinum: Structural modeling and potential targets. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 109, 231–243. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.12.079

Suyama, M., Torrents, D., and Bork, P. (2006). PAL2NAL: Robust conversion of protein sequence alignments into the corresponding codon alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 1, W609–W612. doi:10.1093/nar/gkl315

Takishima, K., Watanabe, S., Yamada, M., Suga, T., and Mamiya, G. (1988). Amino acid sequences of two nonspecific lipid-transfer proteins from germinated castor bean. Eur. J. Biochem. 177, 241–249. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb14368.x

The UniProt Consortium (2021). UniProt: The universal protein knowledgebase in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D480–D489. doi:10.1093/nar/gkaa1100

Untergasser, A., Cutcutache, I., Koressaar, T., Ye, J., Faircloth, B., Remm, M., et al. (2012). Primer3 - new capabilities and interfaces.

Varshney, R. K., Song, C., Saxena, R. K., Azam, S., Yu, S., Sharpe, A. G., et al. (2013). Draft genome sequence of chickpea (Cicer arietinum) provides a resource for trait improvement. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 240–246. doi:10.1038/nbt.2491

Verma, M., Kumar, V., Patel, R. K., Garg, R., and Jain, M. (2015). Ctdb: An integrated chickpea transcriptome database for functional and applied genomics. PLoS ONE 10, e0136880. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0136880

Voorrips, R. E. (2002). MapChart: Software for the graphical presentation of linkage maps and QTLs. J. Hered. 93, 77–78. doi:10.1093/jhered/93.1.77

J. M. Walker (Editor) (2005). The proteomics protocols handbook (Totowa, NJ: Humana Press). doi:10.1385/1592598900

Wang, Y., Tang, H., Debarry, J. D., Tan, X., Li, J., Wang, X., et al. (2012). MCScanX: A toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 40 (7), e49. doi:10.1093/nar/gkr1293

Wang, X., Li, Q., Cheng, C., Zhang, K., Lou, Q., Li, J., et al. (2020). Genome-wide analysis of a putative lipid transfer protein LTP_2 gene family reveals CsLTP_2 genes involved in response of cucumber against root-knot nematode (Meloidogyne incognita). Genome 63, 225–238. doi:10.1139/gen-2019-0157

Wang, C., Gao, H., Chu, Z., Ji, C., Xu, Y., Cao, W., et al. (2021). A nonspecific lipid transfer protein, StLTP10, mediates resistance to Phytophthora infestans in potato. Mol. Plant Pathol. 22, 48–63. doi:10.1111/mpp.13007

Wei, K., and Zhong, X. (2014). Non-specific lipid transfer proteins in maize. BMC Plant Biol. 14, 281. doi:10.1186/s12870-014-0281-8

Yeats, T. H., and Rose, J. K. C. (2008). The biochemistry and biology of extracellular plant lipid-transfer proteins (LTPs). Protein Sci. 17, 191–198. doi:10.1110/ps.073300108

Keywords: lipid transfer proteins (LTPs), chickpea, Helicoverpa armigera, phylogenetic analysis, plant defense, herbivory

Citation: Saxena H, Negi H, Keshan R, Chitkara P, Kumar S, Chakraborty A, Roy A, Singh IK and Singh A (2023) A comprehensive investigation of lipid-transfer proteins from Cicer arietinum disentangles their role in plant defense against Helicoverpa armigera-infestation. Front. Genet. 14:1195554. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2023.1195554

Received: 28 March 2023; Accepted: 19 June 2023;

Published: 30 June 2023.

Edited by:

Ertugrul Filiz, Duzce University, TürkiyeReviewed by:

Nasreen Bano, University of Pennsylvania, United StatesSpurthi N. Nayak, University of Agricultural Sciences, India

Anuj Kumar, Dalhousie University, Canada

Parviz Heidari, Shahrood University of Technology, Iran

Copyright © 2023 Saxena, Negi, Keshan, Chitkara, Kumar, Chakraborty, Roy, Singh and Singh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Archana Singh, YXJjaGFuYXNpbmdoQGhyYy5kdS5hYy5pbg==; Indrakant K. Singh, aWtzaW5naEBkYi5kdS5hYy5pbg==; Amit Roy, cm95QGZsZC5jenUuY3o=

Harshita Saxena

Harshita Saxena Harshita Negi

Harshita Negi Radhika Keshan1

Radhika Keshan1 Amrita Chakraborty

Amrita Chakraborty Amit Roy

Amit Roy Indrakant K. Singh

Indrakant K. Singh Archana Singh

Archana Singh