- 1Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, United States

- 2Native Nations Institute, Udall Center for Studies in Public Policy, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, United States

- 3Library and Information Sciences, School of Information, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, United States

- 4Law Library, School of Law, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC, United States

- 5Department of Sociology, College of Social Sciences, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States

- 6American Indian Studies Program, College of Social Sciences, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States

- 7Center for Human Development, College of Health, University of Alaska Anchorage, Anchorage, AK, United States

- 8Te Kotahi Research Institute, University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand

- 9Institute for Society and Genetics, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States

- 10Institute for Precision Health, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States

- 11Division of General Internal Medicine and Health Services Research, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States

Biomedical data are now organized in large-scale databases allowing researchers worldwide to access and utilize the data for new projects. As new technologies generate even larger amounts of data, data governance and data management are becoming pressing challenges. The FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) were developed to facilitate data sharing. However, the Indigenous Data Sovereignty movement advocates for greater Indigenous control and oversight in order to share data on Indigenous Peoples’ terms. This is especially true in the context of genetic research where Indigenous Peoples historically have been unethically exploited in the name of science. This article outlines the relationship between sovereignty and ethics in the context of data to describe the collective rights that Indigenous Peoples assert to increase control over their biomedical data. Then drawing on the CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance (Collective benefit, Authority to control, Responsibility, and Ethics), we explore how standards already set by Native nations in the United States, such as tribal research codes, provide direction for implementation of the CARE Principles to complement FAIR. A broader approach to policy and procedure regarding tribal participation in biomedical research is required and we make recommendations for tribes, institutions, and ethical practice.

Introduction

As technological advances have generated immense amounts of biomedical data, the Indigenous Data Sovereignty (IDSov) movement has emerged to exert stronger control and oversight over data generated from Indigenous Peoples. Once subject to localized systems of management, biomedical data are now organized and stored in large-scale databases, allowing researchers worldwide to access and utilize data for new analyses. The governance of large-scale databases, many of which adopt broad data sharing models, often stands in contrast with stricter mechanisms of protection and relationships of trust that facilitated the original data collection. This disconnect is clearly evident in the case of Indigenous communities who have often challenged the extractive nature of genetic research (Boyer et al., 2007; Shaw et al., 2013; Trinidad et al., 2015; Haring et al., 2018; Chadwick et al., 2019; Dirks et al., 2019). We support the call for more open, inclusive, and equitable participation in research and innovation to resolve the tension between openness and innovation, on the one hand, and Indigenous rights and interests, on the other. This is a tension that pervades the current discourse on genetic diversity (Hudson et al., 2020; Welch et al., 2021).

Historically, biomedical data may not have been collected or utilized in ways that align with community rights and interests. The results are research with little or no benefit to the communities from which the data originated, potential biases in data interpretation, dwindling participation in genetics and genomics research, and limited oversight by the people from whom the data are collected (Garrison et al., 2019a). These negative experiences compound as biomedical and data futures move towards big data and large-scale biobanking. At the same time, the resurgence of Indigenous self-determination and the advancement of IDSov prompts a reexamination of data governance (Kukutai and Taylor 2016a; Garrison et al., 2019a; Carroll et al., 2020; Hudson et al., 2020; Walter et al., 2021). At a fundamental level, IDSov articulates the rights of Indigenous Peoples and nations to govern the collection, application, and use of data about their peoples, communities, lands, and resources (Kukutai and Taylor, 2016b).

This article outlines the relationship between sovereignty and ethics in the context of data to describe the collective rights that Indigenous Peoples assert to increase control over their biomedical data. Then drawing on the CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance (Collective benefit, Authority to control, Responsibility, and Ethics), we explore how standards already set by Native nations, such as tribal research codes, provide direction for implementing the CARE Principles. We close with recommendations for using tribal codes, laws, policy documents, and protocols to operationalize the CARE Principles as a way to spur translational genetics research that benefits Native nations, as well as rural and urban Indigenous communities.

Indigenous Peoples and Data

For the purposes of this paper, we define Indigenous Peoples in the US as American Indian, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, and other communities who are indigenous to the US and its territories. We will use Native nations and tribes interchangeably to refer to tribal nations in the US. The federal government recognizes 574 tribes in the US as sovereign nations with their own legal and political structures to govern their citizens and homelands (Department of the Interior, 2021). In addition, many other Indigenous Peoples exert sovereignty as state-recognized (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2019) or un-recognized nations, including those in the state of Hawai’i and US territories. Sovereignty refers to the collective powers of a nation, such as the power to grant access to the population or to negotiate treaties between nations. As sovereign nations, tribes have the power to govern via their own structures, determine their own citizenship, and regulate tribal business (Duthu, 2008).

Indigenous Peoples have always been “researchers,” demonstrated by their collecting, analyzing, and managing data for decision-making, knowledge transfer, and other uses. Historical and ongoing colonialism disrupted, co-opted, and suppressed Indigenous research methodologies and methods (Smith, 2012). Indigenous data, whether born digital or not, include information, knowledge, specimens, and belongings about Indigenous Peoples to which they relate at both the individual and collective levels (Carroll et al., 2020; Rainie et al., 2019; Lovett et al., 2019). IDSov returns authority over data about Indigenous nations and their citizens, communities, and resources (wherever they may be located) back to the tribes from whom the data derive (Kukutai and Taylor, 2016b). Indigenous Data Governance (IDGov) enables tribal ways of knowing and doing to guide Indigenous decision-making; it is a practical expression of IDSov (Rainie et al., 2017; Maiam nayri Wingara, 2018).

Increasingly over the past 50 years, tribes in the US have developed policies and procedures for the oversight of research within their nations’ physical jurisdiction and beyond tribal lands. Other Native nations rely on tribal colleges, tribal organizations, or the Indian Health Service to provide research oversight on their behalf (Around Him et al., 2019). Federally-recognized tribes are in the strongest legal position to assert authority over their data (Tsosie, 2019). Non-federally-recognized tribes and Indigenous Peoples worldwide experience numerous issues in exercising rights over their data that may be different from federally-recognized tribes (Kukutai and Taylor, 2016a; Walter et al., 2021). However, we posit that learnings from federally-recognized tribes’ codes can broadly benefit Indigenous Peoples as they implement laws, policies, and practices to govern their data and research.

IDGov and tribal research governance complement one another: some data are research data that are subject to both data governance and research governance. Thus, Indigenous research governance becomes a mechanism for enhancing IDGov as tribes assert IDSov.

Indigenous Peoples’ Increased Oversight of Biomedical Research

IDSov requires heightened consideration in projects that evoke a government-to-government relationship, such as federally funded projects that seek to recruit large numbers of Indigenous Peoples nationwide. In these cases, strong relationships and effective data governance systems at the tribal level are paramount for ensuring equitable participation in federally funded research and culturally rigorous results. At the same time, non-tribal institutional policies and practices must also evolve to promote and protect the sovereign rights and interests of Indigenous Peoples.

American Indian and Alaska Native populations are not simply ethnic or racial groups, nor are they vulnerable or “special” populations. Tribes maintain a unique political status and confer citizenship just like other nation states. Tribal citizenship persists regardless of residence on or off tribal lands. Also called tribal enrollment, tribal citizenship is not the same as self-identification nor is it the same as genetic ancestry (Tallbear, 2013). Tribal citizenship is a political designation similar to US citizenship. This political designation is the foundation for IDSov. Yet, the inclusion of Indigenous people off tribal lands challenges the reach of tribal oversight of research over enrolled tribal citizens. Approximately 78% of self-identified American Indian and Alaska Native individuals live off tribal lands, and approximately 60% primarily reside in urban areas (Norris et al., 2012). For Indigenous people living off tribal lands, questions arise regarding how tribes will govern information about them when data are collected and reside outside the jurisdictional boundaries of the tribal nation. Additional questions include how other institutions, such as intertribal non-profit organizations and universities, will steward and protect data about Indigenous Peoples and individuals.

The recognition of IDSov by federal agencies and large repositories funded by organizations like the National Institutes of Health (NIH) is an important first step. The use of already existing tribal expectations delineated in reports, policies, and practices are important next steps to align federal programs with tribal rights and expectations via IDSov (Tribal Collaboration Working Group, 2018). In late 2019, the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) (National Congress of American Indians, 2019a) asserted that even in the absence of formal tribal approval processes, researchers must establish a process to obtain approval that allows for tribal oversight of tribal data. Furthermore, the NCAI membership passed Resolution ABQ-19-061 that “calls on NIH to consult with tribal nations, provide a process for tribal nations to have oversight over any data and biospecimens from their tribal citizens, and restrict use of data associated with tribal nations until tribal oversight is in place” (National Congress of American Indians, 2019b). This resulted in developing a formal tribal consultation process (National Congress of American Indians, 2021; Haozous et al., 2021).

Tribal concerns about data use and data sharing have generated many discussions in federal agencies, universities, professional societies, and Indigenous communities. To build ethical university-tribal partnerships, it is necessary to recognize tribes as sovereign nations, acknowledge tribal intellectual property, and respect tribal data sharing preferences (James et al., 2014). Indigenous individuals’ concerns about privacy and confidentiality also extend to promotion of tribal rights to control data and protection of collective tribal confidentiality and privacy in data and research (Taitingfong et al., 2020). In interviews with Indigenous leaders, scholars, and tribal research review members, support for tribal oversight of data is seen as a viable solution to the challenges of data access, management, and sharing (Garrison et al., 2019b). Given the history of exploitative research with tribal communities, the ability of tribes to review inaccurate, harmful, or stigmatizing information before publication or distribution is crucial both to preventing the misuse of their data and to supporting sound scientific practice (Garrison et al., 2019a). This is increasingly important as biomedical and genomics research moves toward broad data sharing policies.

Indigenous data oversight has increased in response to support of broad data sharing by funders and scientists. The NIH Genomic Data Sharing policy requires federally-funded investigators to deposit de-identified data into federal databases to promote secondary analyses (National Institutes of Health, 2014). However, the policy allows a data sharing exception that recognizes some tribal laws may not permit broad data sharing (Hiratsuka et al., 2020). Some tribal laws and policies dictate that all data generated from a research study is property of the tribe and all data must be returned to the tribe at the conclusion of the study. A resulting concern about the data sharing policy is that the allowable exceptions are not clearly understood or recognized by all researchers, institutions, or journal editors. For example, some investigators who conduct research with Indigenous communities have been asked by journal editors to submit the data to federal databases, even when the agreement with the tribe is not to share data.

Implementation of CARE Principles Guided by Tribal Oversight

The current structures that are in place for federal biomedical data governance, in particular the Common Rule (Office of Human Research Protections, 2017), fail to align with the rights and interests of Indigenous nations and communities (Hudson et al., 2020). Rather than demanding that representatives of Indigenous communities participate in these existing governance structures, we argue for sovereign control—that is, Indigenous nations controlling ownership, governing storage, and dictating parameters for data use and reuse. We also promote policy innovations for other institutions that both adhere to tribal sovereignty and protect Indigenous people living off tribal lands or who self-identify as Indigenous (i.e., not tribally affiliated).

This section introduces the CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance as high-level guidance for enhancing IDSov in research and data governance. This section also examines the sovereign expectations that tribes set for researchers and institutions to support Indigenous Peoples’ efforts to reclaim control and oversight of data, including biospecimens.

The CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance

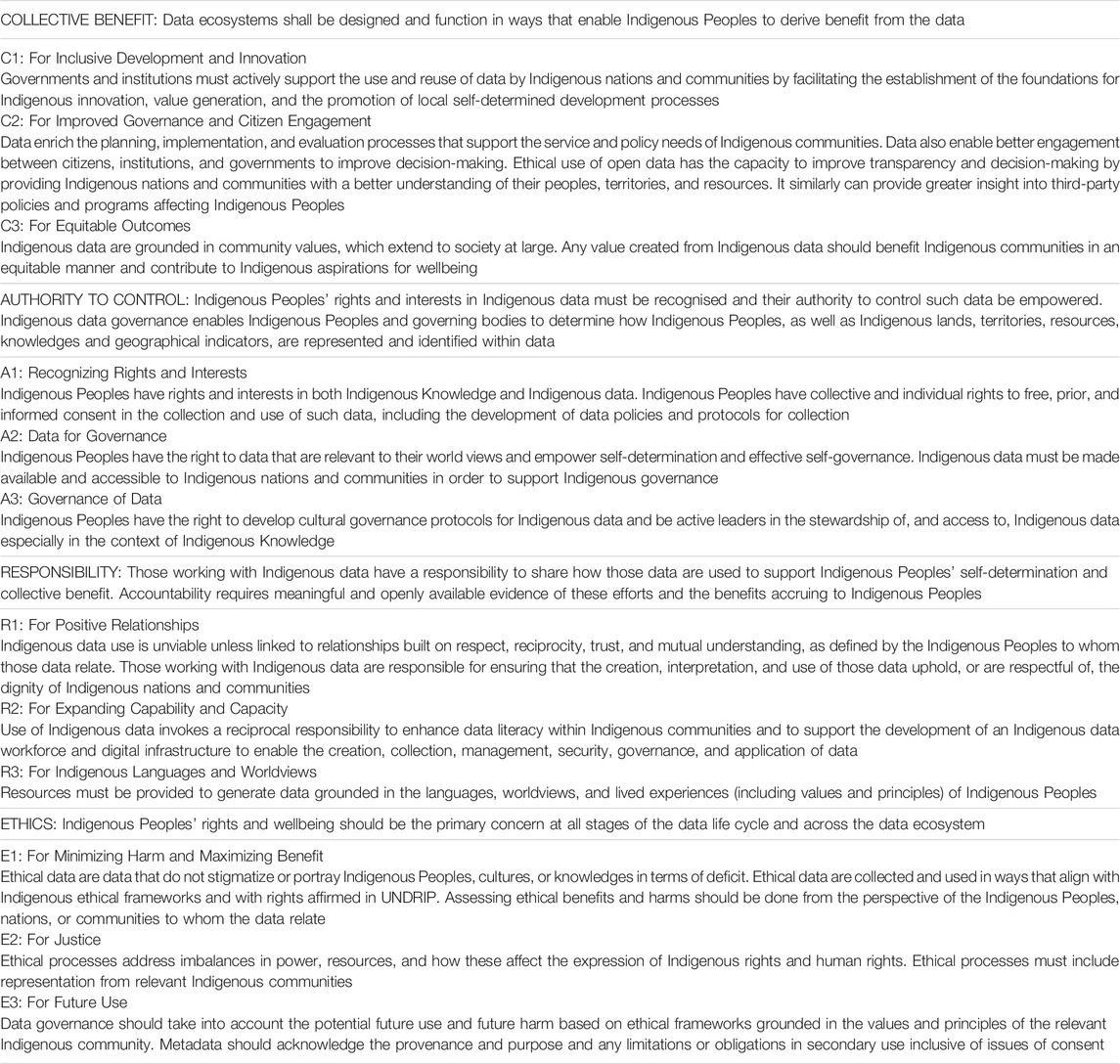

The CARE Principles define Collective benefit, Authority to control, Responsibility, and Ethics, and their relationship to engagement with and for secondary use of Indigenous data (Research Data Alliance Interest Group, 2019). The CARE Principles and the sub-principles (see Table 1) enhance and extend the ‘FAIR Principles’ for scientific data management (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable; Wilkinson et al., 2016) by centering equity and ethics as core guiding principles alongside those set out by FAIR. The CARE Principles reflect the crucial role of data in advancing Indigenous innovation and self-determination by focusing on people and purpose-oriented standards to be used alongside mainstream data guidelines (Carroll et al., 2020).

Tribal Research Governance as Expectations

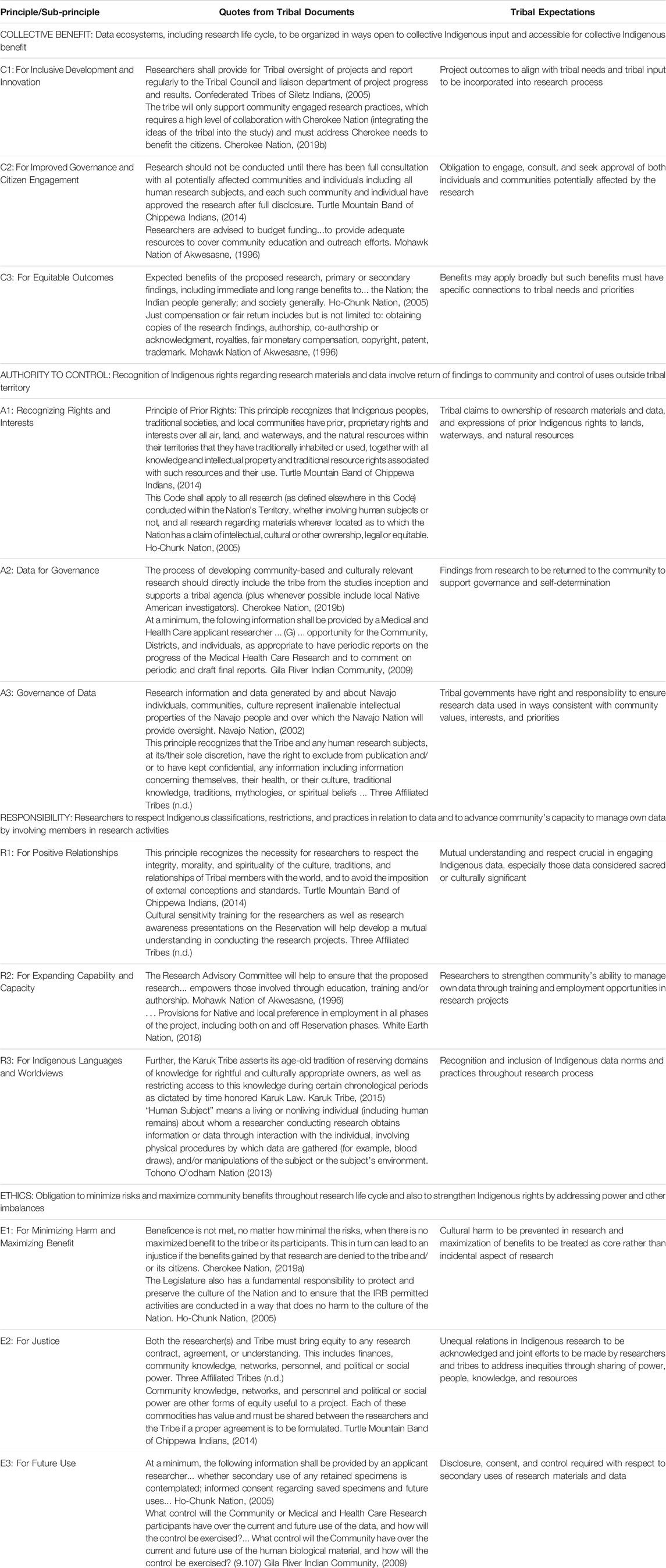

The CARE Principles are in the early stages of implementation, with some entities leading the way by collaborating with the Global Indigenous Data Alliance (GIDA) to operationalize the principles within repositories, national ethics frameworks, and United Nations open science guidance (Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, 2020; Carroll et al., 2021; United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2021; Welch et al., 2021). Large international genomics consortia are already implementing the FAIR principles, but to truly engage and demonstrate respect for marginalized, impacted, excluded, underserved populations, the CARE Principles must be integrated across institutional policies and practices (Wilkinson et al., 2016; Carroll et al., 2021). We draw on federal- and state-recognized Native nations’ research regulations (Table 2) to illustrate how these official documents’ assertions of IDSov set tribal expectations for enacting the CARE Principles. Tribal expectations include alignment with tribal priorities, recognizing the locus of control for tribal data, supporting respectful relationships, and addressing inequities in research.

TABLE 2. The CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance: Tribal expectations that guide implementation.

Discussion and Recommendations

Below we make recommendations for tribes, other institutions, and ethical practices that leverage Native nations’ codes as standards for researchers and data stewards as they implement the CARE Principles.

Tribal Law and Policy

Native nations are increasingly using tribal codes to set standards and expectations, exerting their jurisdiction over data, interests, places, and issues both on and off reservations (National Congress of American Indians, 2019a; Hiraldo et al., 2020). Here we share some of the ways that tribes address some of the more complex issues of tribal research oversight, including jurisdiction off tribal lands and protection of individual and collective interests, to spur Native nations to create and strengthen codes as guides to use of the CARE Principles with their peoples, lands, knowledges, and resources.

The fact that most tribal citizens reside off tribal lands (Norris et al., 2012), but may participate in research, raises unique challenges to the exercise of tribal sovereignty in research. Tribes have sought to address this governance challenge by extending the application of their research codes beyond tribal lands in two situations: (1) use of materials to which tribes have a legal claim and (2) participation of tribal citizens. Some tribes extend the protection of their citizens and interests beyond their territories by linking the exercise of their sovereignty to the physical location of research materials to which they have a claim (Colorado River Indian Tribes, 2009; Gila River Indian Community, 2009; Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate Tribe, n.d.; no date, henceforth n.d.; United Houma Nation Institutional Review Board Ordinance, n.d.; White Earth Nation, 2018; Tribal Collaboration Working Group, 2018). Other tribes address research governance challenges beyond their territories by linking the exercise of sovereignty to participation of their citizens in research, particularly in studies that implicate aspects of their tribal citizenship and affiliation in some way (Navajo Nation, 2002; Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians, 2005; Ho-Chunk Nation, 2005; Pascua Yaqui Tribe, 2008).

Some tribal claims of ownership over specimens and data are made in the context of broader statements about tribal sovereignty. For example, the Three Affiliated Tribes (n.d.) includes a general principle of prior rights that recognizes, among other rights, “proprietary rights and interests over… all knowledge and intellectual property” associated with their resources. Similarly, the United Houma (n.d.) Institutional Review Board Ordinance codifies the rights of the Tribe, “as a self-governed and self-determined people,” to “all data and information generated and produced by… research” conducted in the community. Other codes couch the tribe’s claim to ownership of specimens and data in narrower terms (Pascua Yaqui Tribe, 2008; Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians, 2005; Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate Tribe, n.d.), while others stress the need for researchers to respect those claims (Mohawk Nation of Akwesasne, 1996; Cherokee Nation, 2019b).

Some codes protect not only tribal (i.e., collective) but also individual citizens’ claims to ownership and control of specimens and data (Tohono O’odham Nation, 2013; Colorado River Indian Tribes, 2009). Tribes have adopted intellectual property provisions in their codes to support individual and collective claims of ownership in specimens and data (Mohawk Nation of Akwesasne, 1996; Navajo Nation, 2002; Ho-Chunk Nation, 2005; Colorado River Indian Tribes, 2009; Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians, 2014).

Issues in research agreements pertaining to data reflect broad tribal concerns about specimens. Additional points include the need to: describe specific means of preserving confidentiality of individual and tribal data, including Assurances of Confidentiality (Mohawk Nation of Akwesasne, 1996; Ho-Chunk Nation, 2005; Gila River Indian Community, 2009); provide data disposal plans (Cherokee Nation, 2019b); and detail conditions that would allow researchers to breach their duty of confidentiality under signed agreements (Mohawk Nation of Akwesasne, 1996; Ho-Chunk Nation, 2005).

International, Federal, and Institutional Guidelines

As institutions increasingly operationalize the CARE Principles in policy and practice, understanding how high-level principles link to tribal expectations becomes paramount. While research institutions, researchers, and funding agencies must follow appropriate federal, state, and local laws, they must also follow proper engagement and consultation procedures with tribal nations to uphold tribal law and policy pertaining to research, data, and specimens. Tribal laws and processes need to be part of robust planning and policy for research institutions and programs to implement the CARE Principles. Importantly, each Native nations’ written standards apply to research relationships with that nation only. The written standards must be balanced with ongoing community relationships to give more depth and definitions to community expectations and needs. Additionally, when no laws exist, it is the responsibility of research institutions, researchers, and funding agencies to engage in a process with participating tribal nations to obtain approvals and guidance for research and data oversight (Tribal Collaboration Working Group, 2018; National Congress of American Indians, 2019a). Finally, examining the commonalities across Native nations provides insight into broad and common ethical expectations.

Evolving Ethical Practices

The CARE Principles, especially as indicated by tribal research codes, delineate standards for research practice. Training for researchers to understand tribal sovereignty, tribal codes, and review processes is necessary to provide the knowledge and tools to meet tribal ethical expectations. Supporting the CARE Principles requires an approach to biomedical research and policy that supports tribal ethics requirements, regardless if they have been codified as law.

Institutions, researchers, tribes, and Indigenous communities will benefit from careful attention to the CARE Principles to enhance trust and build meaningful relationships to ensure high quality translational biomedical science that emerges as tangible benefits for tribes and rural and urban Indigenous communities.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

SC and NG conceptualized, drafted, and finalized the manuscript. IG, VH, MH, RP, and DSR contributed to drafting and editing.

Funding

The Morris K. Udall and Stewart L. Udall Foundation supported SC, IG, and RP.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Indigenous Peoples worldwide, and the tribes in the US that are re-imagining and re-membering laws, policies, and practices to assert their right to control and enact their responsibility to protect data about their peoples, lands, and resources. Special appreciation to the Native nations whose codes and policies are cited in this document for making this information publicly available so others are able to learn from it. Some concepts in this essay emerged as comments in response to the Request for Information (RFI) soliciting additional input to the All of Us Research Program 2019 Tribal Consultation (Notice Number: NOT-PM-19-004). SC is also grateful for the thoughtful comments of Professor Jane Anderson, and for the invitation to present this research to the “Innovation Policy Colloquium” at New York University School of Law. The authors are grateful to Danella Hall, Candace Yazzie, and Rogena Sterling for related work that spurred ideas and concepts.

References

Around Him, D., Andalcio Aguilar, T., Frederick, A., Larsen, H., Seiber, M., and Angal, J. (2019). Tribal IRBs: A Framework for Understanding Research Oversight in American Indian and Alaska Native Communities. Am. Indian Alsk. Native Ment. Health Res. 26 (2), 71–95. doi:10.5820/aian.2602.2019.71

Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (2020). AIATSIS Code of Ethics for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Research. Canberra, Australia: AIATSIS. Available at: https://aiatsis.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-10/aiatsis-code-ethics.pdf (Accessed January 19, 2022).

Boyer, B. B., Mohatt, G. V., Pasker, R. L., Drew, E. M., and McGlone, K. K. (2007). Sharing Results from Complex Disease Genetics Studies: a Community Based Participatory Research Approach. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 66 (1), 19–30. doi:10.3402/ijch.v66i1.18221

Carroll, S. R., Rodriguez-Lonebear, D., and Martinez, A. (2019). Indigenous Data Governance: Strategies from United States Native Nations. Data Sci. J. 18 (31), 1–15. doi:10.5334/dsj-2019-031

Carroll, S. R., Garba, I., Figueroa-Rodríguez, O. L., Holbrook, J., Lovett, R., Materrechera, S., et al. (2020). The CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance. Data Sci. J. 19 (43), 1–12. doi:10.5334/dsj-2020-043

Carroll, S. R., Herczog, E., Hudson, M., Russell, K., and Stall, S. (2021). Operationalizing the CARE and FAIR Principles for Indigenous Data Futures. Sci. Data 8 (1), 1–6. doi:10.1038/s41597-021-00892-0

Chadwick, J. Q., Copeland, K. C., Branam, D. E., Erb-Alvarez, J. A., Khan, S. I., Peercy, M. T., et al. (2019). Genomic Research and American Indian Tribal Communities in Oklahoma: Learning from Past Research Misconduct and Building Future Trusting Partnerships. Am. J. Epidemiol. 188 (7), 1206–1212. doi:10.1093/aje/kwz062

Cherokee Nation (2019a). Guidance on Study Closure. Information and Guidance Documents. Available at: https://irb.cherokee.org/media/jezhjftz/guidance-on-study-closure.pdf (Accessed January 19, 2022).

Cherokee Nation (2019b). Tribal Research. Information and Guidance Documents. Available at: https://irb.cherokee.org/media/zaulx5iz/tribal-reserach.pdf (Accessed January 19, 2022).

Colorado River Indian Tribes (2009). Human and Cultural Research Code. Ordinance No. 09-04. Available at: https://www.crit-nsn.gov/crit_contents/ordinances/Human-and-Cultural-Research-Code.pdf (Accessed January 19, 2022).

Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians (2005). Research Ordinance. Ordinance No. 9.100. Available at: https://www.ctsi.nsn.us/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Research-Ordinance-09-16-2005.pdf (Accessed January 19, 2022).

Department of the Interior (2021). Indian Entities Recognized and Eligible to Receive Services from the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs. Federal Register 86, No. 67. 18552. Available at: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2021-04-09/pdf/2021-06723.pdf (Accessed January 19, 2022).

Dirks, L. G., Shaw, J. L., Hiratsuka, V. Y., Beans, J. A., Kelly, J. J., and Dillard, D. A. (2019). Perspectives on Communication and Engagement with Regard to Collecting Biospecimens and Family Health Histories for Cancer Research in a Rural Alaska Native Community. J. Community Genet. 10 (3), 435–446. doi:10.1007/s12687-019-00408-9

Garrison, N. A., Hudson, M., Ballantyne, L. L., Garba, I., Martinez, A., Taualii, M., et al. (2019a). Genomic Research through an Indigenous Lens: Understanding the Expectations. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 20 (1), 495–517. doi:10.1146/annurev-genom-083118-015434

Garrison, N. A., Barton, K. S., Porter, K. M., Mai, T., Burke, W., and Carroll, S. R. (2019b). Access and Management: Indigenous Perspectives on Genomic Data Sharing. Ethn. Dis. 29 (Suppl. 3), 659–668. doi:10.18865/ed.29.S3.659

Gila River Indian Community (2009). The Medical and Health Care Research Ordinance (Ord GR-05-09), Title 17, Chapter 9. Gila River Indian Community Code. Available at: https://naair.arizona.edu/sites/default/files/gila_river_indian_ord_gr-05-09_title_17_chapter_9_0.pdf (Accessed January 19, 2022).

Haozous, E. A., Lee, J., and Soto, C. (2021). Urban American Indian and Alaska Native Data Sovereignty: Ethical Issues. Am. Indian Alsk. Native Ment. Health Res. 28 (2), 77–97. doi:10.5820/aian.2802.2021.77

Haring, R. C., Henry, W. A., Hudson, M., Rodriguez, E. M., and Taualii, M. (2018). Views on Clinical Trial Recruitment, Biospecimen Collection, and Cancer Research: Population Science from Landscapes of the Haudenosaunee (People of the Longhouse). J. Canc Educ. 33 (1), 44–51. doi:10.1007/s13187-016-1067-5

Hiratsuka, V. Y., Hahn, M. J., Woodbury, R. B., Hull, S. C., Wilson, D. R., Bonham, V. L., et al. (2020). Alaska Native Genomic Research: Perspectives from Alaska Native Leaders, Federal Staff, and Biomedical Researchers. Genet. Med. 22 (12), 1935–1943. doi:10.1038/s41436-020-0926-y

Ho-Chunk Nation (2005). Tribal Research Code, Ho-Chunk Nation Code, 3 HCC §3. Available at: https://tribalinformationexchange.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Ho-Chunk-Nation-Tribal-Research-Code.pdf (Accessed January 19, 2022).

Hudson, M., Garrison, N. A., Sterling, R., Caron, N. R., Fox, K., Yracheta, J., et al. (2020). Rights, Interests and Expectations: Indigenous Perspectives on Unrestricted Access to Genomic Data. Nat. Rev. Genet. 21, 377–384. doi:10.1038/s41576-020-0228-x

James, R., Tsosie, R., Sahota, P., Parker, M., Dillard, D., Sylvester, I., et al. (2014). Exploring Pathways to Trust: a Tribal Perspective on Data Sharing. Genet. Med. 16 (11), 820–826. doi:10.1038/gim.2014.47

Karuk Tribe (2015). Protocol with Agreement for Intellectual Property Rights of the Karuk Tribe: Research, Publication and Recordings. Publication and Recordings. Available at: https://www.karuk.us/images/docs/forms/Protocol_with_Agreement_for_Intellectual_Property_Rights_of_the_Karuk_Tribe.pdf (Accessed January 19, 2022).

Kukutai, T., and Taylor, J. (Editors) (2016a). Indigenous Data Sovereignty: Toward an Agenda. Canberra, Australia: Australian National University Press.

Kukutai, T., and Taylor, J. (2016b). “Data Sovereignty for Indigenous Peoples: Current Practice and Future Needs,” in Indigenous Data Sovereignty: Toward an Agenda. Editors T. Kukutai, and J. Taylor (Canberra, Australia: Australian National University Press), 1–24.

Lovett, R., Lee, V., Kukutai, T., Rainie, S. C., and Walker, J. (2019). “Good Data Practices for Indigenous Data Sovereignty,” in Good Data. Editors A. Daly, K. Devitt, and M. Mann (Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures).

Maiam nayri Wingara (2018). Indigenous Data Sovereignty Communique. Canberra, Australia: Maiam Nayri Wingaara. Available at https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5b3043afb40b9d20411f3512/t/5b6c0f9a0e2e725e9cabf4a6/1533808545167/ Communique%2B-%2BIndigenous%2BData%2BSovereignty%2BSummit.pdf (Accessed January 19, 2022).

Mohawk Nation of Akwesasne (1996). Protocol for Review of Environmental and Scientific Research Proposals, Akwesasne Task Force on the Environment and Research Advisory Committee. Available at: https://nnigovernance.arizona.edu/protocol-review-environmental-and-scientific-research-proposals (Accessed January 19, 2022).

National Conference of State Legislatures (2019). Federal and State Recognized Tribes. Available at https://www.ncsl.org/research/state-tribal-institute/list-of-federal-and-state-recognized-tribes.aspx (Accessed January 19, 2022).

National Congress of American Indians (2019a). Re: All of Us Research Program Tribal Consultation. Washington, DC: National Congress of American Indians. Available at: http://www.ncai.org/policy-research-center/research-data/recommendations/NCAI_Letter_NIH_All_of_Us_Research_Program_Consultation_11_26_2019_FINAL_signed.pdf (Accessed January 19, 2022).

National Congress of American Indians (2019b). Resolution ABQ-19-061 - Calling upon the National Institutes of Health to Consult with Tribal Nations and Establish Policies and Guidance for Tribal Oversight of Data on Tribal Citizens Enrolled in the All Of Us Research Program. Albuquerque: National Congress of American Indians. Available at: https://www.ncai.org/ABQ-19-061.pdf (Accessed January 19, 2022).

National Congress of American Indians (2021). Consultation Support Center. Washington, DC: National Congress of American Indians. Available at: https://www.ncai.org/resources/consultation-support (Accessed January 19, 2022).

National Institutes of Health (2014). Genomic Data Sharing Policy. Fed. Regist. 79, 16751345–16751354. Available at: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2014-08-28/pdf/2014-20385.pdf (Accessed January 19, 2022).

Navajo Nation (2002). Human Research Code. Health and Welfare. 13 NNC §§3251 through 3271. April 16, 2002. Available at: https://www.nnhrrb.navajo-nsn.gov/pdf/NavNatHumResCode.pdf (Accessed January 19, 2022).

Norris, T., Vines, P. L., and Hoeffel, E. M. (2012). The American Indian and Alaska Native Population: 2010. Washington, D.C: Census Bureau. Available at: https://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-10.pdf (Accessed January 19, 2022).

Office of Human Research Protections (2017). Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects. Final Rule. Fed. Regist. 82, 7149–7274. Available at: https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2017-01-19/pdf/2017-01058.pdf (Accessed January 19, 2022).

Pascua Yaqui Tribe (2008). Research Protection. 8 PYTC §§7-1-10 through 7-1-250. May 14, 2008. Available at: https://www.pascuayaqui-nsn.gov/tribal-code/ch-7-1-research-protection/ (Accessed January 19, 2022).

Rainie, S. C., Rodriguez-Lonebear, D., and Martinez, M. (2017). Policy Brief (Version 2): Data Governance for Native Nation Rebuilding. Tucson: Native Nations Institute, University of Arizona. Available at: https://climas.arizona.edu/sites/default/files/Policy_Brief_Data_Governance_for_Native_Nation_Rebuilding_Version_2.pdf (Accessed January 19, 2022).

Rainie, S. R., Kukutai, T., Walter, M., Figueroa-Rodriguez, O. L., Walker, J., and Axelsson, P. (2019). “Issues in Open Data: Indigenous Data Sovereignty,” in The State of Open Data: Histories and Horizons. Editors T. Davies, S. Walker, M. Rubinstein, and F. Perini (Cape Town and Ottawa: African Minds and International Development Research Centre), 300–319.

Research Data Alliance International Indigenous Data Sovereignty Interest Group (2019). “CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance,” in The Global Indigenous Data Alliance. Editors S. R. Carroll, and M. Hudson. Available at: https://www.gida-global.org/ (Accessed February 11, 2022).

Shaw, J. L., Robinson, R., Starks, H., Burke, W., and Dillard, D. A. (2013). Risk, Reward, and the Double-Edged Sword: Perspectives on Pharmacogenetic Research and Clinical Testing Among Alaska Native People. Am. J. Public Health 103 (12), 2220–2225. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301596

Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate Tribe (n.d.). Research Code. Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate Codes of Law §§77-01-01 through 77-07-06. Available at: https://www.swo-nsn.gov/wp-content/uploads/Chapter-77-ResearchCode-FINAL-V15.pdf (Accessed January 19, 2022).

Smith, L. T. (2012). Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. Second edition. London: Zed Books.

Taitingfong, R., Bloss, C. S., Triplett, C., Cakici, J., Garrison, N., Cole, S., et al. (2020). A Systematic Literature Review of Native American and Pacific Islanders' Perspectives on Health Data Privacy in the United States. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 27 (12), 1987–1998. doi:10.1093/jamia/ocaa235

TallBear, K. (2013). Native American DNA: Tribal Belonging and the False Promise of Genetic Science. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Tohono O'odham Nation (2013). Research Code. 17 Tohono O’odham Code Chapter 8. Available at: https://naair.arizona.edu/sites/default/files/tohono_oodham_nation_title17ch8_0.pdf (Accessed January 19, 2022).

Tribal Collaboration Working Group (2018). All of Us Research Program Advisory Panel. Considerations for Meaningful Collaboration with Tribal Populations. Available at: https://allofus.nih.gov/sites/default/files/tribal_collab_work_group_rept.pdf (Accessed January 19, 2022).

Trinidad, S. B., Ludman, E. J., Hopkins, S., James, R. D., Hoeft, T. J., Kinegak, A., et al. (2015). Community Dissemination and Genetic Research: Moving beyond Results Reporting. Am. J. Med. Genet. 167 (7), 1542–1550. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.37028

Tsosie, R. (2019). Tribal Data Governance and Informational Privacy: Constructing ‘Indigenous Data Sovereignty. Mont. L. Rev. 80 (2).

Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians (2014). Research Protection Act. Available at: https://nebula.wsimg.com/792a7ad79f2b2b8886d214cd7373ab8c?AccessKeyId=FF0318FE16C15B6C1F97&disposition=0&alloworigin=1 (Accessed January 19, 2022).

United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) (2021). UNESCO Recommendation on Open Science. Paris: UNESCO. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000379949.locale=en (Accessed January 19, 2022).

Walter, M., Kukutai, T., Carroll, S. R., and Rodriguez-Lonebear, D. (Editors) (2021). Indigenous Data Sovereignty and Policy. New York: Routledge.

Welch, E., Louafi, S., Carroll, S. R., Hudson, M., IJsselmuiden, C., Kane, N., et al. (2021). Post COVID-19 Implications on Genetic Diversity and Genomics Research & Innovation: A Call for Governance and Research Capacity. Rome: Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. Available at: http://www.fao.org/3/cb5573en/cb5573en.pdf (Accessed January 19, 2022).

White Earth Nation (2018). Restructured/Codified White Earth Nation Research Review Board Policy/Procedure.

Keywords: genetic research, Indigenous, data sovereignty, data governance, CARE principles

Citation: Carroll SR, Garba I, Plevel R, Small-Rodriguez D, Hiratsuka VY, Hudson M and Garrison NA (2022) Using Indigenous Standards to Implement the CARE Principles: Setting Expectations through Tribal Research Codes. Front. Genet. 13:823309. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2022.823309

Received: 27 November 2021; Accepted: 21 February 2022;

Published: 21 March 2022.

Edited by:

Tina Lasisi, The Pennsylvania State University (PSU), United StatesReviewed by:

Nchangwi S. Munung, University of Cape Town, South AfricaJohn C. Burnett, Beckman Research Institute, City of Hope, United States

Rebecca Pollet, Vassar College, United States

Copyright © 2022 Carroll, Garba, Plevel, Small-Rodriguez, Hiratsuka, Hudson and Garrison. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nanibaa’ A. Garrison, bmFuaWJhYUBzb2NnZW4udWNsYS5lZHU=

Stephanie Russo Carroll

Stephanie Russo Carroll Ibrahim Garba1,2

Ibrahim Garba1,2 Rebecca Plevel

Rebecca Plevel Vanessa Y. Hiratsuka

Vanessa Y. Hiratsuka Maui Hudson

Maui Hudson Nanibaa’ A. Garrison

Nanibaa’ A. Garrison