- 1Key Laboratory of Freshwater Fish Reproduction and Development (Ministry of Education), Key Laboratory of Aquatic Science of Chongqing, School of Life Sciences, Southwest University, Chongqing, China

- 2Pearl River Fisheries Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Fisheries Science, Key Laboratory of Tropical and Subtropical Fishery Resource Application and Cultivation, Ministry of Agriculture, Guangzhou, China

- 3Department of Biology, University of Maryland, College Park, Rockville, MD, United States

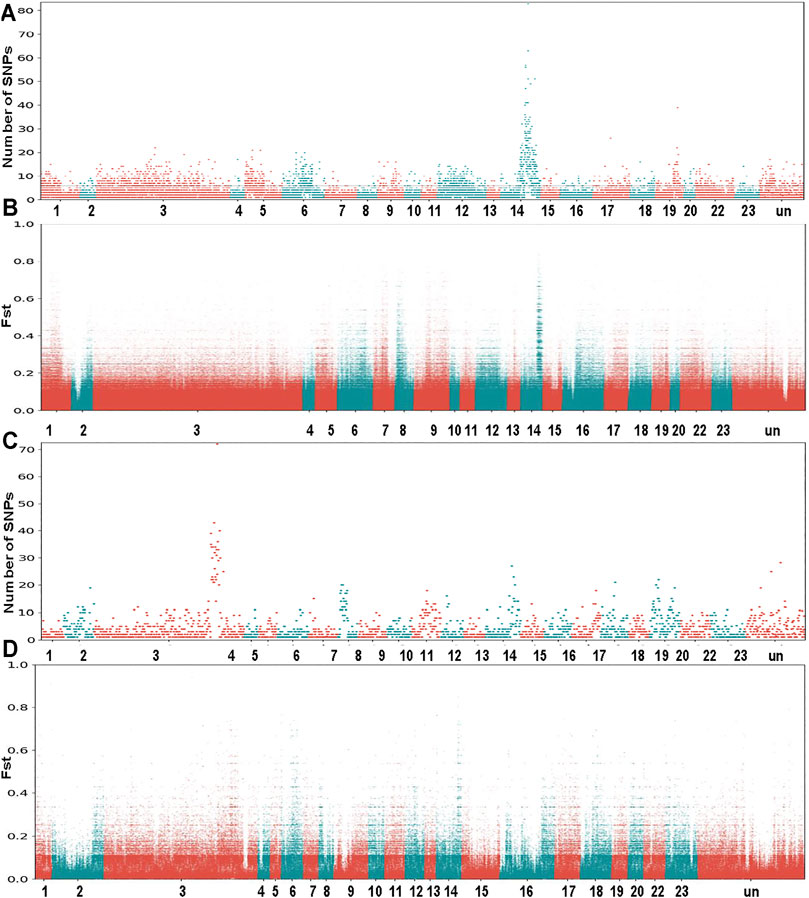

The Mozambique tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus) is a fascinating taxon for evolutionary and ecological research. It is an important food fish and one of the most widely distributed tilapias. Because males grow faster than females, genetically male tilapia are preferred in aquaculture. However, studies of sex determination and sex control in O. mossambicus have been hindered by the limited characterization of the genome. To address this gap, we assembled a high-quality genome of O. mossambicus, using a combination of high coverage of Illumina and Nanopore reads, coupled with Hi-C and RNA-Seq data. Our genome assembly spans 1,007 Mb with a scaffold N50 of 11.38 Mb. We successfully anchored and oriented 98.6% of the genome on 22 linkage groups (LGs). Based on re-sequencing data for male and female fishes from three families, O. mossambicus segregates both an XY system on LG14 and a ZW system on LG3. The sex-patterned SNPs shared by two XY families narrowed the sex determining regions to ∼3 Mb on LG14. The shared sex-patterned SNPs included two deleterious missense mutations in ahnak and rhbdd1, indicating the possible roles of these two genes in sex determination. This annotated chromosome-level genome assembly and identification of sex determining regions represents a valuable resource to help understand the evolution of genetic sex determination in tilapias.

Introduction

Sex determination, the process by which a sexually reproducing organism initiates differentiation as a male or female, is triggered either by genetic factors on sex chromosomes or environmental factors (Capel, 2017). Cytological analysis can only distinguish highly divergent sex chromosomes with significant differences in morphology (Wright et al., 2016; Palmer et al., 2019). The sex chromosome systems of mammals and birds are highly conserved, with cytologically differentiated sex chromosomes that have lost many ancestral genes and gained a large number of repetitive sequences. Fishes display a diversity of sex determining systems, from environmental to genetic sex determination (Schartl, 2004; Nagahama, 2005). Most fish have homomorphic sex chromosomes which are indistinguishable by shape (Devlin and Nagahama, 2002; Bachtrog et al., 2014). Thus, the identification and characterization of sex chromosomes in fishes has only advanced in recent years, when advances in DNA sequencing and bioinformatic methods made it possible to identify and characterize these less diverged sex chromosomes. Sex chromosomes have now been characterized in a wide variety of fishes based on both chromosome-level genome assemblies generated from long read sequence data, as well as re-sequencing of male and female genomes using short read sequencing technology (Dixon et al., 2019; Pan et al., 2019; Li et al., 2020; Peichel et al., 2020; Wen et al., 2020; Einfeldt et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021; Nakamoto et al., 2021; Tao et al., 2021; Xue et al., 2021).

Cichlids are an excellent model for understanding the evolution of sex determination as they show unusual diversity of sex chromosome systems (Gammerdinger and Kocher, 2018; El Taher et al., 2021). Several species of tilapias are the economically most important species of cichlids, and they are widely grown in tropical and subtropical climates. In aquaculture, all-male tilapias are favored because of the superior growth rate of males compared to females (Mair et al., 1995; Zhong et al., 2019), and the control of unwanted reproduction during the grow-out period. Therefore, the genetic basis of sex determination in tilapia has been studied for over 50 years. Both male heterogametic XX/XY system and female heterogametic ZZ/ZW system have been identified in tilapia (Cnaani et al., 2008). Variation of sex determining systems is apparent among closely related tilapia species, or even in different populations of the same species. For example, in different populations of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus), male sex determining loci have been identified on linkage groups (LG) 1, 20 and 23 (Gammerdinger et al., 2014; Li et al., 2015; Palaiokostas et al., 2015). An XY system on LG1 has been identified in Stirling Nile tilapia stock and blackchin tilapia (Sarotherodon melanotheron) (Gammerdinger et al., 2014; Gammerdinger et al., 2016). Both the closely related blue tilapia (O. aureus) and more diverged spotted tilapia (Pelmatolapia mariae) segregates an epistatically dominant ZW locus on LG3 (Conte et al., 2017; Gammerdinger et al., 2019; Tao et al., 2021). Recently, banf2w has been found to be concordant with female determination in four tilapias with LG3 ZW/ZZ SD-systems, including O. aureus, O. tanganicae, O. hornorum and P. mariae (Curzon et al., 2021). The major sex-determination gene on LG23 is a duplication of amh, which is known to play an important role in the vertebrate sex-determination network (Li et al., 2015; Pan et al., 2021b). The sex determining systems of other species in this lineage, including the Mozambique tilapia (O. mossambicus), remain to be elucidated.

The Mozambique tilapia is native to inland and coastal waters in southeastern Africa. It has been introduced to many tropical and subtropical habitats in the world, and plays a significant role in fish production around the world (El-Sayed, 2019) due to its adaptability to brackish water. Microsatellite DNA markers on LG1 and LG3 are found to be associated with sex based on QTL studies from the F2 of an interspecific cross between O. aureus and O. mossambicus (Cnaani et al., 2003; Cnaani et al., 2004). Recently, comparison of re-sequencing data of O. mossambicus against the reference genome of O. niloticus revealed a high density of XY-patterned SNPs uniformly spread across the first 10 Mb of LG14 (Gammerdinger et al., 2019). This large differentiated sex determining region might be explained by either error in the anchoring process or genome differences between O. niloticus and O. mossambicus. Thus, a chromosomal level genome assembly of O. mossambicus would facilitate the identification of sex-determining regions and further characterization of the sex determining genes in this species.

In the present study, we generated a chromosome-level genome assembly of a female O. mossambicus. We identified sex determining regions on LG14 and LG3 based on the re-sequencing data of different families, and compared the sex determining region on LG14 identified from two families. Our study lays a foundation for understanding the genetic basis of sex determination in Mozambique tilapia.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

Animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the regulations of the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Committee of Laboratory Animal Experimentation at Southwest University.

Sample Collection and Sequencing

To generate a chromosome-level assembly of O. mossambicus, a whole XX female fish was sourced from Pearl River Fishery Research Institute in 2019. Phenotypic sex was determined based on histological observation of gonad tissue as described (Tao et al., 2018). Skeletal muscle was flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and the DNA was extracted using a Blood and Cell Culture DNA Midi Kit (Q13343, Qiagen) to construct Illumina and Nanopore library. To identify a full range of transcripts, gill, brain, heart, kidney, head kidney, muscle and testis were collected and stored in RNAlater.

An improved Hi-C procedure (Rao et al., 2014) was adapted for Hi-C library construction. Briefly, the blood sample was treated with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature and the reaction was quenched by adding glycine. Nuclei were digested with 100 units of DpnII, labeled with biotin-14- dCTP (Invitrogen), and ligated using T4 DNA ligase. Subsequently, the ligated DNA was sheared into fragments of 300–600 bp. These Hi-C libraries were sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq X Ten platform.

Seven RNA samples were extracted from gill, brain, heart, kidney, head kidney, muscle and testis using Trizol (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The RNA was treated with DNaseI (RNase-free, 5 U μl-1) to remove DNA contamination. Poly-T Oligonucleotides attached to magnetic beads were used to isolate poly(A) mRNA from total RNA according to the Illumina sample preparation guide. Paired-end cDNA libraries of different tissues were constructed using the RNASeq NGS library preparation kit (Gnomegen) and sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq 2500 system with a read length of 150 bp.

Genome Assembly and Synteny Analyses

To generate a high-quality genome assembly, we generated Nanopore long reads (110.57 Gb), 10x Genomics Illumina reads (30.42 Gb), and Hi-C Illumina read pairs (104.66 Gb). Oxford Nanopore basecalling was performed using Guppy V3.2.2 (Wick et al., 2019). A performance-oriented assembler NextDenovo V2.0-beta.1 (https://github.com/Nextomics/NextDenovo) with default parameters was used for genome assembly, including sequencing error correction, preliminary assembly, and genome polishing (Supplementary Figure S1). The NextCorrect module was used to correct sequencing errors and extract consensus sequence. These qualified long reads were assembled to obtain the preliminary assembly by NextGraph. Genome polishing to fix base errors was performed using NextPolish. Subsequently, the Hi-C data was processed to assemble the chromosomal-level genome. For the Illumina reads of HiC sequencing, fastp (Chen et al., 2018) was used to remove low quality reads, trim adapters and polyG tails. The clean Hi-C reads were aligned to the assembled scaffolds using bowtie2 V2.3.2 (Langmead and Salzberg, 2012) with the end-to-end model (-very- sensitive -L 30). The contact read count among each scaffold was calculated and normalized by standardizing the digestion sites of DpnII on the genome sketch. Then LACHESIS (Burton et al., 2013) was used to order and orientate the scaffolds. Finally, Juicebox (Durand et al., 2016) was used to visualize and manually adjust the candidate assembly until the overall Hi-C interaction heatmap conformed to the overall features of chromosome. Synteny analyses among O. mossambicus, O. niloticus and Archocentrus centrarchus were carried out using MUMmer (Delcher et al., 2003) and MCScanX (Wang et al., 2012).

Genome Annotation

Tandem repeats were identified using the tandem repeats finder (Benson, 1999) and GMATA (Wang and Wang, 2016) with default parameters. Interspersed repeats (transposable elements, TEs) were identified using a combination of de novo and homology-based approaches. MITE-Hunter (-n 20 -P 0.2 -c 3) (Han and Wessler, 2010) was used to identify miniature inverted repeat TEs and other small class II nonautonomous TEs. A de novo repeat library was constructed by Repeatmodeler V1.0.4 (Flynn et al., 2020) and classified automatedly by TEclass (Abrusan et al., 2009). Finally, Repeatmasker V4.0.6 (Chen, 2004) was adopted to search the repeat regions against the repeat library.

Protein-coding genes were predicted using ab initio, homology and RNA sequence-based methods. The ab initio gene prediction and gene structures were generated by Augustus v3.3.1 (Stanke et al., 2006). For homology-based gene prediction, protein sequences of Oreochromis niloticus (GCF_001858045.2), Oryzias latipes (GCF_002234675.1), Danio rerio (GCA_000002035.4), Xiphophorus maculatus (GCF_002775205.1), and Astyanax mexicanus (GCA_000372685.2) were downloaded from NCBI and GeMoMa V1.6.1 (Keilwagen et al., 2016) was adopted with default parameters. For the de novo prediction, RNA-seq reads were de novo assembled using StringTie (Pertea et al., 2015). PASA (https://github.com/PASApipeline/PASApipeline) was used to produce a unigene set. Finally, EVM v1.1.1 (Haas et al., 2008) was used to integrate the gene models predicted by these three different methods and produce a consensus gene set. Transposonpsi (http://transposonpsi.sourceforge.net) was used to align the gene set to the transposon database with default parameters. Genes containing homology to transposons were removed from the final gene set. BUSCO V5.2.2 (Simao et al., 2015) was used to perform quantitative assessment of genome assembly and measure annotation completeness by searching the conserved single-copy genes across Actinopterygii against the predicted gene models of the assembled genome. Completeness of the genome assembly was also estimated with CEGMA v2.5 (Parra et al., 2007). The functional annotation of the predicted genes of O. mossambicus were performed by homology searches against public gene databases, including the NR, SwissProt, KOG, KEGG and GO databases using BLAST v2.2.31 (Altschul et al., 1990). The results from searches against these 5 databases were concatenated as the final annotation result. For the noncoding RNAs annotation, different methods were adopted. The rRNA, snRNA and miRNA sequences were predicted by Infenal 1.1 (Nawrocki and Eddy, 2013) on Rfam (Griffiths-Jones et al., 2003) and miRBase (Kozomara et al., 2019). The rRNA sequences and their subunits were annotated using RNAmmer V1.2 (Lagesen et al., 2007). The tRNA sequences were predicted by tRNAscan-SE v1.3.1 (Lowe and Eddy, 1997) with the default parameters.

Phylogenomic Analyses and Divergence Time Estimation

To identify gene families in the O. mossambicus genome, genome sequences and annotation files of O. niloticus (GCF_001858045.2), O. latipes (GCF_002234675.1), D. rerio (GCA_000002035.4), X. maculatus (GCF_002775205.1), A. mexicanus (GCA_000372685.2), Takifugu rubripes (GCF_901000725.2), Astatotilapia calliptera (GCA_900246225.3), Archocentrus centrarchus (GCF_007364275.1), Pundamilia nyererei (GCA_000239375.1), Maylandia zebra (GCF_000238955.4), Neolamprologus brichardi (GCF_000239395.1), Haplochromis burtoni (GCF_018398535.1) and O. aureus (GCF_013358895.1) were downloaded from NCBI. OrthoMCL V2.0.9 (Li et al., 2003) was used to identify gene families among the genomes of these species. The protein sequences of the selected species were aligned to identify orthologs, paralogs and single-copy orthologs, respectively.

A phylogenetic tree among O. mossambicus and the representative species was constructed based on the single-copy orthologs. The protein sequences of these single-copy orthologs were concatenated into a supermatrix, which was aligned using Mafft V7.313 (Katoh et al., 2002). The poorly aligned sequences were then eliminated using Gblocks (Castresana, 2000). Phylogenetic analyses were performed using RAxML (Stamatakis, 2006) with the GTRGAMMA model and 1,000 bootstrap replicates. Based on the phylogenetic tree, MEGA-CC (Mello, 2018) was adopted to compute the mean substitution rates and estimate divergent time. Gene family expansion and contraction (gain and loss) were estimated using CAFÉ V4.2.1 (De Bie et al., 2006) over the constructed phylogenetic tree.

Analyses of Sex-Linked Regions

Re-sequencing data for two families (Family 1: 8 M, 12 F; Family 2: 15 M, 15 F) of O. mossambicus were downloaded from NCBI (Gammerdinger et al., 2019) and mapped to the newly assembled O. mossambicus genome. Sex-linked regions were identified as described (Gammerdinger et al., 2019). Briefly, variants were called using GATK V4.2 software package (McKenna et al., 2010). HaplotypeCaller and GenotypeGVCF implemented in GATK were used to obtain a single output VCF file. The alignment files were also converted into mpileup files using Samtools V1.9 (Li et al., 2009) and subsequently into sync files using Popoolation2 (Kofler et al., 2011). Next, each family was processed with Sex_SNP_finder_GA.pl (https://github.com/Gammerdinger/sex-SNP-finder) to identify XY and ZW sex-patterned SNPs, and to calculate FST values. The density of these sex-patterned SNPs was quantified in non-overlapping 10 kb windows and examined for an elongation of the high SNP density tail in the distributions of both the XY- and ZW-patterned SNPs.

To narrow the sex-determining regions, the sex-linked regions of O. mossambicus were also identified based on individual re-sequencing data as described (Xue et al., 2021). Briefly, genome re-sequencing data of 5 male and 5 female fish from the Pearl River Fishery Research Institute were collected individually. The phenotypic sex of each fish was identified through gonadal histology and DNA was extracted from muscle tissue. Paired-end libraries were constructed with an insert size of 300–500 base pairs (bp) according to manufacturer’s protocol and subsequently sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq X Ten platform. The raw reads were filtered and trimmed using fastp (Chen et al., 2018) and then mapped against the assembled chromosome-level genome using BWA-MEN (Li, 2013) using the default parameters. After marking and removing duplicates with MarkDuplicate implemented in Picard tools (https://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/), single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were called using the joint calling pipeline of GATK V4.1.4.0 (Van der Auwera et al., 2013). The parameters “QD < 2.0 || FS > 60.0 || MQRankSum < -12.5 || RedPosRankSum < -8.0 || SOR >3.0 || MQ < 40.0” (Xue et al., 2021) were used to filter the SNPs. SNPeff 4.3t (Cingolani et al., 2012) was used to identify the SNPs that are homozygous in one sex but heterozygous in the other sex. Patterns of sex-linked SNPs were compared to identify the sex determining systems. The VCF files of different families were compared to extract the shared sex-patterned SNPs using Bedtools V2.29.1 (Quinlan and Hall, 2010).

Functional Annotation

The functional annotation and potential coding properties of sex-linked SNPs was performed using ANNOVAR (Wang et al., 2010) with the annotated gene models. mRNA models without full length protein coding sequences were excluded from the analysis. Missense mutations located in exonic regions were then analyzed to predict the functional impact of the missense mutation using PROVEAN V1.1.5 (Choi and Chan, 2015). Substitutions with scores lower than the recommended PROVEAN threshold of −2.5 were considered to be deleterious. The 3D structure models for genes with deleterious mutation were developed using Phyre2 (http://www.sbg.bio.ic.ac.uk/phyre2) for predicting the protein structure by homology modeling under “intensive” mode.

Results

Chromosome-Level Assembly and Genomic Characteristics of O. mossambicus

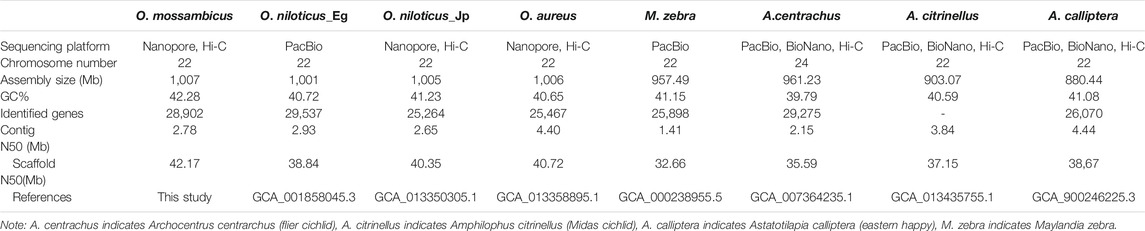

We used a combination of Nanopore long reads, Illumina short reads, and Hi-C technologies (Supplementary Figures S2–S3 and Supplementary Table S1), to generate a chromosome-level genome assembly for O. mossambicus. A total of 110.57 Gb Nanopore long reads were used to assemble a preliminary genome sequence, which was subsequently polished. Additionally, a total of 714 million raw Illumina reads with total length of about 104.66 Gb generated from the Hi-C library were applied to identify contacts among the Nanopore contigs, of which 357 million pairs of clean reads covered 99.93% of the assembled genome. The final assembly had 22 chromosomes with a total length of 1,007 Mb (Table 1), and 98.62% of contigs were anchored to the chromosomes. The heatmap of chromosome contact demonstrates that the genome assembly was complete and robust (Figure 1A). The genome size of O. mossambicus is comparable to that of its mostly related species, including O. niloticus and O. aureus. The contig N50 and scaffold N50 of the O. mossambicus assembly were 2.78 and 11.38 Mb (Table 1, Supplementary Table S2 and Supplementary Figure S4), respectively. The largest chromosome was LG3 with 130.76 Mb in length containing 46 scaffolds, and the smallest was LG19 with 32.83 Mb containing only 2 scaffolds. A. centrarchus is the most closely related species with a high-quality chromosome-scale assembly and a typical teleost karyotype of 24 chromosome pairs. To evaluate the quality of the assembly and facilitate the identification of chromosome fusion, we performed synteny analyses among O. mossambicus, O. niloticus and A. centrarchus. There were 39,689 synteny blocks (>2 kb) between the assembled genomes of O. mossambicus and A. centrarchus. Almost all chromosomes showed the 1:1 synteny relationship, with the exception of LG3 in the fish that aligned to Chr2 and Chr18 of A. centrarchus (Figure 1B). Genome synteny analysis also revealed good collinear relationship of the genome between O. mossambicus and O. niloticus (Supplementary Figure S5). The genome assembly of O. mossambicus had 97.71% complete BUSCO genes and 239 of 248 (96.38%) of conserved core eucaryotic genes in CEGMA v2.5 database (Supplementary Table S3). These results indicated that the genome assembly was of highly completeness. Moreover, nearly a half of the assembled sequences on LG3 showed no detectable synteny with any other chromosomes, supporting the hypothesis of B chromosome fusion origin, instead of autosome fusion origin, of this giant chromosome (Conte et al., 2021).

FIGURE 1. (A) Genome-wide chromosomal contact matrix of O. mossambicus based on chromatin interaction data generated by Hi-C. The low to high interaction frequency distribution of Hi-C links among chromosomes is shown from light yellow to dark red in the heatmap. (B) Comparison of the genome of O. mossambicus and A. centrarchus. A Circos atlas presents details of the pseudo-chromosome information from outside to inside: (I) the length of each chromosome, (II) GC content of 100-Kb genomic intervals, (III) density of gene distribution in each 100-Kb genomic interval, (IV) density of repeats in each 100-Kb genomic interval. A synteny comparison between O. mossambicus and A. centrarchus genomes (Chr represents A. centrarchus and lg represents O. mossambicus) revealed high accuracy of our assembled O. mossambicus genome.

The results of Repbase database and de novo prediction showed that repeated sequences accounted for 42.28% of the O. mossambicus genome, which is similar to O. niloticus (40.4%), O. aureus (39.4%) and O. latipes (42.83%), but lower than D. rerio (63.12%). Transposable elements accounted for the major parts of repeated sequences in the O. mossambicus genome. DNA transposons (21.13%) were the most common, followed by LINEs (long interspersed repeated segments, 10.13%) and LTR (long terminal repeats, 6.56%) (Supplementary Table S4). The most abundant tandem repeats were centromeric repeats which were identified on all LGs except LG22 (Supplementary Table S5), including the known tilapia centromeric repeat SATA (Franck et al., 1992). In total, 28,902 protein-coding genes were predicted by ab initio, homologous prediction and RNA-seq prediction in the O. mossambicus genome, with an average gene length of 16,519 bp. The average coding sequence length and intron length were 1,574 bp and 1,733 bp, respectively, with average exon number of 9.62 per gene. The functions of the protein-coding genes were annotated using the NR, TrEMBL, KOG, KEGG, and GO databases. A total of 4,524 tRNAs, 556 rRNAs and 1,170 miRNAs were predicted by Infernal and Rfam databases.

Phylogenomic Analyses

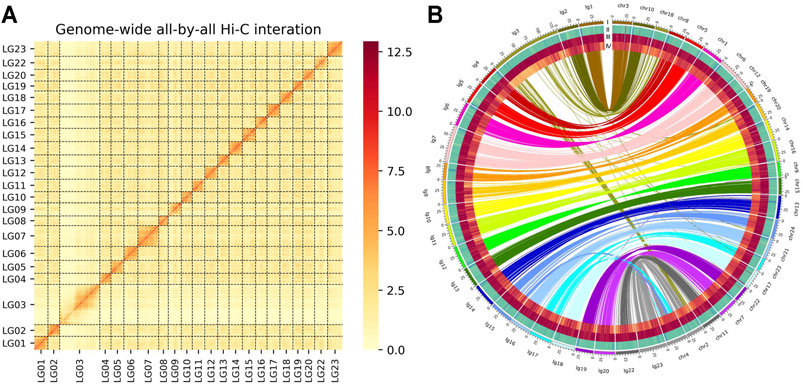

Genomes of the O. mossambicus and other 13 representative fishes (D. rerio, A. mexicanus, T. rubripes, X. maculatus, O. latipes, A. calliptera, A. centrarchus, P. nyererei, M. zebra, N. brichardi, H. burtoni, O. aureus and O. niloticus) were analyzed to establish the phylogenetic relationship. It appeared that O. mossambicus was most closely related to the branch consisting of O. aureus and O. niloticus (Figure 2). Consistent with previous studies based on phylogenomic analyses (Salzburger, 2018; Ronco et al., 2021), our results showed that cichlids were characterized by exceptionally fast diversification rates. All the nodes displayed 100 confidence intervals, indicating that this tree is robust. The overall topology is consistent with the previously comprehensive phylogenetic work on cichlids and ray-finned fishes (Hughes et al., 2018; Matschiner et al., 2020).

FIGURE 2. Phylogenetic analysis of O. mossambicus and other representative teleost fish species. The species divergence time is shown at the branches of the phylogenetic tree, and the confidence intervals are given in parentheses.

Identification of Sex Determining Regions

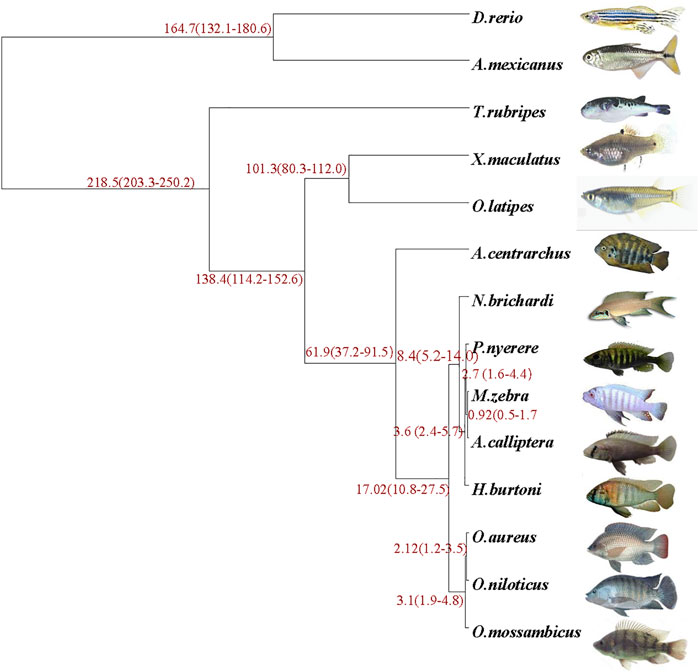

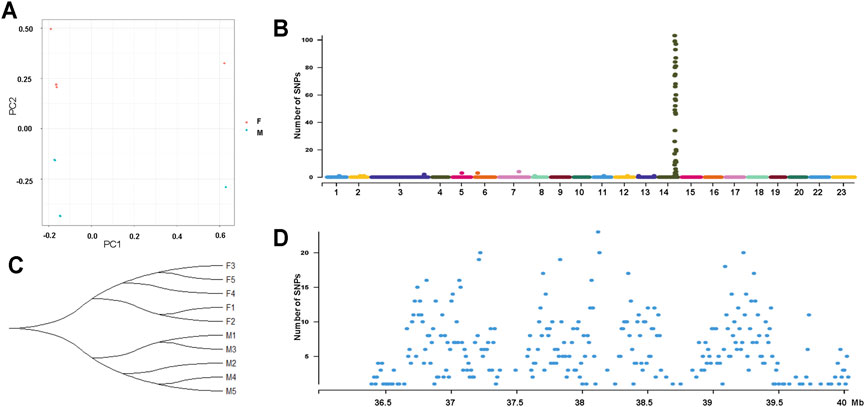

The O. mossambicus genome assembly was used to identify sex-determining regions of this species. Based on the whole genome re-sequencing data of pooled DNA from males and females of two families, a novel XY sex determining system on LG14 was characterized in O. mossambicus (Gammerdinger et al., 2019). We realigned these re-sequencing data to the O. mossambicus genome assembly and identified the variants that were fixed in either the female pool or the male pool. For Family 1, examination of the whole genome Fst plot comparing males and females revealed a strong signal on LG14 (Figure 3A). This region overlapped with the previously identified XY sex-determining regions in O. mossambicus (Gammerdinger et al., 2019) which spanned approximately 10 Mb. A total of 12,397 SNPs in Family 1 of O. mossambicus fitted the sex-patterned criteria. In Family 1, there were 451 non-overlapping 10 kb windows with at least 10 XY-patterned SNPs (Supplementary Table S6). The highest densities of sex-patterned SNPs (with more than 20 sex-linked SNPs per 10 Kb) occurred between 33.3 and 41.8 Mb on LG14 (Figure 3B). LG14 showed comparable repeat content of autosomes based on the Repeat element annotation (Supplementary Table S5). For Family 2, examination of the Fst plot identified a ZW sex determining pattern with strong signals on the giant chromosome LG3 (Figure 3C). A total of 2,290 SNPs in Family 2 fit the ZW-patterned criteria. There were 136 non-overlapping 10 kb windows with at least 10 sex-patterned SNPs in Family 2 (Supplementary Table S7). The highest densities of sex-patterned SNPs (with more than 20 sex-linked SNPs per 10 Kb) occurred between 97.1 and 110.7 Mb (Figure 3D). Our results indicated that multiple sex determination systems have been observed in O. mossambicus.

FIGURE 3. Whole genome survey of sex chromosomes in O. mossambicus. (A) Sex-patterned variants of Family 1, intermediate frequency SNPs in males that are fixed or nearly fixed in females. (B) FST comparison of female pool versus male pool from Family 1. (C) Sex-patterned variants of Family 2. (D) FST comparison of female pool versus male pool from Family 2. The genome re-sequencing data are retrieved from NCBI SRA database (Gammerdinger et al., 2019).

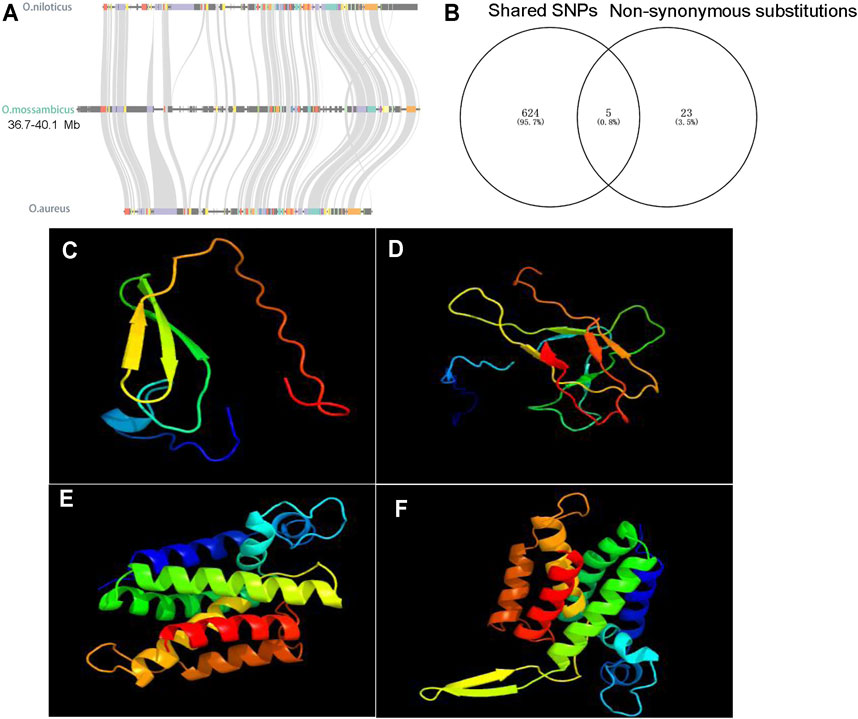

To further characterize the degree of sequence differentiation between sexes and identify sex-determining regions, we also sequenced 5 male and 5 female fish individually to an average depth of 20-fold. Using the assembled O. mossambicus genome as a reference, we detected a total of 4,231,342 SNPs and 1,680 XY-patterned SNPs (Supplementary Table S8). Principal component analysis (Figure 4A) and an SNP tree (Figure 4B) showed that male and female genomes clustered into two distinct groups, indicating sex-specifically differentiated genomic regions. Higher SNP density and substantially higher heterozygosity were presented in male individuals. Moreover, SNP density mapping showed that only 1.23% of the putatively sex-linked SNPs were located on autosomes. The highest SNP density was on the sex chromosome LG14 (Figure 4C). The region from 36.3 to 40 Mb on LG14 displayed high density of sex-patterned SNPs (Figure 4D). No differences in sequencing depth ratio were observed between females and males in this region. Synteny relationships in this region were shared among O. mossambicus, O. aureus and O. niloticus (Figure 5A). These results suggested that LG14 was possibly a young sex chromosome without accumulation of a large number of structural variations (Gammerdinger et al., 2019). To narrow the sex determining region of O. mossambicus, we compared the sex-linked SNPs identified in the individual re-sequencing with the pooled re-sequencing data from Family 1 (Figure 5B). We found that 629 out of 1,680 sex-patterned SNPs spanning 36.3–40 Mb on LG14 were shared by these two families (Supplementary Table S9). The density of sex-patterned SNPs was highest between 37–38 Mb on LG14 (Supplementary Table S10). We evaluated the location of these sex patterned SNPs and found that only 14 (2.05%) SNPs were located on the exonic regions, while 282 (44.8%) and 305 (48.5%) of the SNPs were located in the intronic and intergenic regions, respectively. Among the 14 SNPs in the exonic regions, 6 were located between 37–38 Mb, in which 3 were harbored on the ahnak gene. The functional annotation of the 14 SNPs in the exonic regions showed that 5 missense mutations were located in the ahnak, sae1, znf235, rhbdd1 and an uncharacterized gene 98.31% identical to LOC106098495. The mutations in ahnak and rhbdd1 were predicted to be deleterious. Protein modelling of ahnak and rhbdd1 using Phyre2 showed that the mutation on the Y allele changed the predicted protein structures of both genes (Figures 5C–F).

FIGURE 4. Genome-wide identification of SNPs from 5 male and 5 female individuals from Zhujiang population of O. mossambicus. (A) Principal component analysis of 10 individuals using SNPs. (B) Phylogenetic tree showing relationships of male (M1-M5) and female (F1-F5) SNPs. (C) Sex-linked SNPs of 10 individuals indicate LG14 is the sex chromosome of the Zhujiang population. (D) Density of sex-linked in each 10-Kb genomic interval on LG14.

FIGURE 5. Characterization of sex-determining regions. (A) Syntenic relationships of sex-determining regions on LG14 among O. niloticus, O. aureus and O. mossambicus. (B) 5 shared non-synonymous substitutions, and the other 23 non-synonymous substitutions are only found in the Zhujiang population. (C) The predicted protein structures of Y-linked ahnak. (D) The predicted protein structures of X-linked ahnak. (E) The predicted protein structures of Y-linked rhbdd1. (F) The predicted protein structures of X-linked rhbdd1.

Discussion

Like other tilapias, male Mozambique tilapia grow faster and are more uniform in size than females. For this reason, production of monosex, genetically male populations are desirable for aquaculture. In order to characterize the sex determining system in this species, we developed a highly accurate and contiguous genome assembly. This genome sequence will contribute to the development of technologies to produce all male populations of O. mossambicus for commercial aquaculture, and may also help us to better understand the unusual diversity of sex chromosomes in tilapias.

Genome Assembly

A variety of metrics confirm the high quality of our genome assembly for O. mossambicus. First, we compared the overall size of our assembly to the assembled genome size of closely related species of Oreochromis. The genome assembled from 44x PacBio reads from a female O. niloticus Egyptian strain was 1,001 Mb (Conte et al., 2017). Recent genome assemblies from a female O. niloticus Japanese strain and male O. aureus Wuxi strain generated from 100X Nanopore reads by us were 1,005 Mb and 1,006 Mb, respectively (Tao et al., 2021). In the present study, the assembled genome of a female O. mossambicus is 1,007 Mb, which matches the assembled genome size of sister species in Oreochromis genus, and within the range of assembled genome sizes of other cichlids (880–1,007 Mb). Second, standard measures of assembly contiguity, such as contig N50 and scaffold N50, are comparable to those of other cichlids with high quality genome assemblies (Conte et al., 2017; Conte et al., 2019; Tao et al., 2021). Third, measures of annotation completeness based on the CEGMA (Parra et al., 2007) and BUSCO (Simao et al., 2015) gene lists suggest our assembly includes a high proportion of the expected gene content. Fourth, the repeat-rich regions, such as centromeres, were identified on each chromosome except LG22 in the assembled genome. Finally, the assembled giant chromosome (LG3) of O. mossambicus showed syntenic blocks with Chr2 and Chr18 of A. centrarchus and the rest of LG3 showed undetectable synteny with other chromosomes of A. centrarchus, which supports the previous hypothesis of ancient chromosome fusion events of LG3 in the tribe Oreochromini based on the cytogenetic analysis and comparative genomic study (Chew et al., 2002; Conte et al., 2021). Thus, we have assembled a high-quality, chromosome-level genome of O. mossambicus, which lays the foundation for subsequent identification of sex chromosomes and sex determining regions.

Sex Determination Regions

Research on sex determination in tilapia has important economic implications because of the different growth rates between sexes, and therefore research on the molecular basis of sex determination in tilapia has been conducted for decades. Oreochromis niloticus has one of the best-documented sex determination systems, with major sex determining regions characterized on LG1, LG20 and LG23 (Lee et al., 2003; Li et al., 2015; Palaiokostas et al., 2015; Taslima et al., 2021). Recently, sex determining systems have been characterized in several other tilapias, including S. melanotheron, O. aureus, O. mossambicus, C. zillii and P. mariae, by Illumina re-sequencing (Gammerdinger et al., 2016; Conte et al., 2017; Gammerdinger et al., 2019). However, the sequence divergence between these species and the O. niloticus reference genome used for mapping the reads possibly introduces problems in the analysis. Thus, in the present study, whole genome re-sequencing data of male and female fish from two families of O. mossambicus (Gammerdinger et al., 2019) has been re-analyzed using our new genome assembly. A high density of sex-linked SNPs is identified on LG14 and LG3 in Family 1 and 2, respectively. Previously, only LG14 was identified as the sex chromosome (Gammerdinger et al., 2019). This discrepancy can be attributed to the different analysis strategies adopted. We analyzed the re-sequencing data of Family 1 and Family 2 independently, while the previous study combined the data of the two families into one dataset. The strong signal on LG14 might override the relatively weak signal on LG3 in the previous study (Gammerdinger et al., 2019). Similar to O. niloticus, multiple sex determination systems may exist within and among different families of O. mossambicus. Recently, a duplicate of banf2 (W-copy) on LG3 has been found to be concordant with female phenotypic sex in O. aureus, O. tanganicae, O. hornorum and P. mariae with ZW sex determining system (Curzon et al., 2021). However, the W-specific banf was not identified in the female fish of Family2 with ZW sex determining system based on the re-sequencing data, suggesting the existence of a different female sex determiner in O. mossambicus. These results are in sharp contrast to the sex determining systems shared among several closely related species in other fish lineages, for example, the male-specific amhy in 11 Esociformes species (Pan et al., 2021a) and amhr2y in two seadragons (Qu et al., 2021). A rapid turnover of sex chromosomes and sex-determining genes may have contributed to the adaptative radiation in tilapia and other cichlids (Ser et al., 2010; Ronco et al., 2021).

Although pool-seq data of high genome coverage is a practical method for identifying genes of major effect (Micheletti and Narum, 2018), individual sequencing has been proved to be more efficient in most cases (Cutler and Jensen, 2010). In the previous study, using the genome of O. niloticus as the reference, a recent genome scan from two families of O. mossambicus revealed a high density of XY-patterned SNPs uniformly spread across 10 Mb of LG14 (Gammerdinger et al., 2019). In the present study, re-analysis of the same re-sequencing data of Family 1 on the new genome assembly confirmed the same sex-linked region on LG14. However, based on the individual sequencing data of 5 females and 5 males, we successfully narrowed the sex determination region on LG14 to 3.7 Mb (36.3–40.0 Mb). Therefore, comparing SNP density between multiple males and females individually is a powerful approach to identify sex determining regions.

The conserved synteny of LG14 among different tilapias, together with the small sex determining region, suggests that recombination suppression has not spread very far from the sex-determining locus, and structural variants have not yet accumulated. These results suggest that LG14 is an evolutionarily young sex chromosome, consistent with the conclusion based on the lack of a bimodal distribution in the distribution of non-overlapping sex-patterned windows (Gammerdinger et al., 2019). LG14 has not been frequently identified as the sex chromosome of the cichlid fishes from African Lake Tanganyika (El Taher et al., 2021). To our knowledge, LG14 has only been identified as sex chromosomes in lab strains and one natural population of Astatotilapia burtoni with polygenic sex determination system (Bohne et al., 2016; Roberts et al., 2016). The broad region of differentiation in A. burtoni makes it difficult to know if the same genes might be involved in sex determination.

SNPs leading to deleterious substitutions were found in ahnak and rhbdd1. It is well documented that germ cell number is an important factor in fish sex determination (Uchida et al., 2004; Matsuda, 2005; Fujimoto et al., 2010; Dai et al., 2021). In tilapia, germ cells of female fish continued to proliferate, whereas the germ cell numbers did not change in males at the key stage of sex determination, indicating that germ cell proliferation could also be a critical threshold of sex determination (Kobayashi et al., 2008; Baroiller et al., 2009). It is well documented that TGF-β signaling pathway, the most frequently used pathway in fish sex determination, plays important roles in modulating the germ cell proliferation in the bipotential gonad (Kikuchi and Hamaguchi, 2013; Pan et al., 2021b). ahnak was a well-established inhibitor of TGF-β signaling, downregulating cyclin D1/D2 and inhibiting cell growth (Lee et al., 2014). It was considered as one of the candidate genes for sex determination in O. mossambicus (Gammerdinger et al., 2019). rhbdd1 is a proapoptotic member of the Bcl-2 family, and its knock-down results in enhanced apoptosis in HEK 293T cells (Wang et al., 2008). Consistently, rhbdd1 was proved to regulate spermatogonia apoptosis in mouse (Wang et al., 2009). Thus, the deleterious mutations and changed protein structures predicted by PROVEAN and Phyre2 in either ahnak or rhbdd1 could possibly affect the germ cell development and sex determination in O. mossambicus. The expression data in gonads at the key stage of sex determination and differentiation is important for the identification of sex determiner. Thus, the sequence of a LG14 Y and expression data at the early stages are required to better understand the structure of this sex chromosome and identify sex determining gene in O. mossambicus.

In conclusion, we generated a chromosome level genome assembly of O. mossambicus. Two sex determining regions harboring a high density of sex-linked SNPs on LG14 (XY) and LG3 (ZW) were identified in O. mossambicus based on whole genome re-sequencing data. Our results provide additional support to the idea that sex chromosome transitions occur at a rapid rate in Oreochromis fishes.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Ethics Statement

Animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the regulations of the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Committee of Laboratory Animal Experimentation at Southwest University.

Author Contributions

WT, DW, JC and ML conceived and designed the research. WT, HX and XZ performed the genome sequencing. WT and DW performed data analyses and wrote the manuscript. WT, JC, JD, HX and XZ performed sample preparation. WT, DW, JC and TK revised the manuscript. All authors approved submission of the manuscript for publication.

Funding

This work was supported by grant 31861123001 from the National Natural Science Foundation of China; grant CARS-46 from China Agriculture Research System of MOF and MARA; grant 2018YFD0900202 from the National Key Research and Development Program of China; grants 31630082, 31972778, 32172953, and 31872556 from the National Natural Science Foundation of China; grants cstc2018jscx-mszd0380 and cstc2018jcyjAX0283 from the Chongqing Science and Technology Commission; grant 2018IB019 from Yunnan Science and Technology Project.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgene.2021.796211/full#supplementary-material

References

Abrusan, G., Grundmann, N., DeMester, L., and Makalowski, W. (2009). TEclass-a Tool for Automated Classification of Unknown Eukaryotic Transposable Elements. Bioinformatics 25, 1329–1330. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btp084

Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W., and Lipman, D. J. (1990). Basic Local Alignment Search Tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410. doi:10.1016/s0022-2836(05)80360-2

Bachtrog, D., Mank, J. E., Peichel, C. L., Kirkpatrick, M., Otto, S. P., Ashman, T. L., et al. (2014). Sex Determination: Why So Many Ways of Doing it? Plos Biol. 12, e1001899. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001899

Baroiller, J. F., D’Cotta, H., and Saillant, E. (2009). Environmental Effects on Fish Sex Determination and Differentiation. Sex. Dev. 3, 118–135. doi:10.1159/000223077

Benson, G. (1999). Tandem Repeats Finder: A Program to Analyze DNA Sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 573–580. doi:10.1093/nar/27.2.573

Böhne, A., Wilson, C. A., Postlethwait, J. H., and Salzburger, W. (2016). Variations on a Theme: Genomics of Sex Determination in the Cichlid Fish Astatotilapia burtoni. BMC Genomics 17, 883. doi:10.1186/s12864-016-3178-0

Burton, J. N., Adey, A., Patwardhan, R. P., Qiu, R., Kitzman, J. O., and Shendure, J. (2013). Chromosome-Scale Scaffolding of De Novo Genome Assemblies Based on Chromatin Interactions. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 1119–1125. doi:10.1038/nbt.2727

Capel, B. (2017). Vertebrate Sex Determination: Evolutionary Plasticity of a Fundamental Switch. Nat. Rev. Genet. 18, 675–689. doi:10.1038/nrg.2017.60

Castresana, J. (2000). Selection of Conserved Blocks from Multiple Alignments for Their Use in Phylogenetic Analysis. Mol. Biol. Evol. 17, 540–552. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026334

Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y., and Gu, J. (2018). Fastp: An Ultra-fast All-In-One FASTQ Preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, i884–890. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560

Chen, N. (2004). Using RepeatMasker to Identify Repetitive Elements in Genomic Sequences. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics Chapter 4, 10. doi:10.1002/0471250953.bi0410s05

Chew, J., Oliveira, C., Wright, J., and Dobson, M. (2002). Molecular and Cytogenetic Analysis of the Telomeric (TTAGGG) n Repetitive Sequences in the Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus (Teleostei: Cichlidae). Chromosoma 111, 45–52. doi:10.1007/s00412-002-0187-3

Choi, Y., and Chan, A. P. (2015). PROVEAN Web Server: A Tool to Predict the Functional Effect of Amino Acid Substitutions and Indels. Bioinformatics 31, 2745–2747. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btv195

Cingolani, P., Platts, A., Wang, L. L., Coon, M., Nguyen, T., Wang, L., et al. (2012). A Program for Annotating and Predicting the Effects of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms, SnpEff. Fly (Austin) 6, 80–92. doi:10.4161/fly.19695

Cnaani, A., Hallerman, E. M., Ron, M., Weller, J. I., Indelman, M., Kashi, Y., et al. (2003). Detection of a Chromosomal Region with Two Quantitative Trait Loci, Affecting Cold Tolerance and Fish Size, in an F2 tilapia Hybrid. Aquaculture 223, 117–128. doi:10.1016/s0044-8486(03)00163-7

Cnaani, A., Zilberman, N., Tinman, S., Hulata, G., and Ron, M. (2004). Genome-Scan Analysis for Quantitative Trait Loci in an F2 tilapia Hybrid. Mol. Genet. Genomics 272 (2), 162–172. doi:10.1007/s00438-004-1045-1

Cnaani, A., Lee, B.-Y., Zilberman, N., Ozouf-Costaz, C., Hulata, G., Ron, M., et al. (2008). Genetics of Sex Determination in Tilapiine Species. Sex. Dev. 2, 43–54. doi:10.1159/000117718

Conte, M. A., Gammerdinger, W. J., Bartie, K. L., Penman, D. J., and Kocher, T. D. (2017). A High Quality Assembly of the Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) Genome Reveals the Structure of Two Sex Determination Regions. BMC Genomics 18, 341. doi:10.1186/s12864-017-3723-5

Conte, M. A., Joshi, R., Moore, E. C., Nandamuri, S. P., Gammerdinger, W. J., Roberts, R. B., et al. (2019). Chromosome-Scale Assemblies Reveal the Structural Evolution of African Cichlid Genomes. Gigascience 8 (4), giz030. doi:10.1093/gigascience/giz030

Conte, M. A., Clark, F. E., Roberts, R. B., Xu, L., Tao, W., Zhou, Q., et al. (2021). Origin of a Giant Sex Chromosome. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 1554–1569. doi:10.1093/molbev/msaa319

Curzon, A. Y., Shirak, A., Benet-Perlberg, A., Naor, A., Low-Tanne, S. I., Sharkawi, H., et al. (2021). Gene Variant of Barrier to Autointegration Factor 2 (Banf2w) Is Concordant with Female Determination in Cichlids. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (13), 7073. doi:10.3390/ijms22137073

Cutler, D. J., and Jensen, J. D. (2010). To Pool, or Not to Pool? Genetics 186, 41–43. doi:10.1534/genetics.110.121012

Dai, S., Qi, S., Wei, X., Liu, X., Li, Y., Zhou, X., et al. (2021). Germline Sexual Fate Is Determined by the Antagonistic Action of Dmrt1 and Foxl3/foxl2 in Tilapia. Development 148 (8), dev199380. doi:10.1242/dev.199380

De Bie, T., Cristianini, N., Demuth, J. P., and Hahn, M. W. (2006). CAFE: A Computational Tool for the Study of Gene Family Evolution. Bioinformatics 22, 1269–1271. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btl097

Delcher, A. L., Salzberg, S. L., and Phillippy, A. M. (2003). Using MUMmer to Identify Similar Regions in Large Sequence Sets. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics 10–3. doi:10.1002/0471250953.bi1003s00

Devlin, R. H., and Nagahama, Y. (2002). Sex Determination and Sex Differentiation in Fish: An Overview of Genetic, Physiological, and Environmental Influences. Aquaculture 208, 191–364. doi:10.1016/s0044-8486(02)00057-1

Dixon, G., Kitano, J., and Kirkpatrick, M. (2019). The Origin of a New Sex Chromosome by Introgression between Two Stickleback Fishes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 36, 28–38. doi:10.1093/molbev/msy181

Durand, N. C., Robinson, J. T., Shamim, M. S., Machol, I., Mesirov, J. P., Lander, E. S., et al. (2016). Juicebox Provides a Visualization System for Hi-C Contact Maps with Unlimited Zoom. Cel Syst. 3, 99–101. doi:10.1016/j.cels.2015.07.012

Einfeldt, A. L., Kess, T., Messmer, A., Duffy, S., Wringe, B. F., Fisher, J., et al. (2021). Chromosome Level Reference of Atlantic Halibut Hippoglossus hippoglossus Provides Insight into the Evolution of Sexual Determination Systems. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 21, 1686–1696. doi:10.1111/1755-0998.13369

El Taher, A., Ronco, F., Matschiner, M., Salzburger, W., and Böhne, A. (2021). Dynamics of Sex Chromosome Evolution in a Rapid Radiation of Cichlid Fishes. Sci. Adv. 7, eabe8215. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abe8215

Flynn, J. M., Hubley, R., Goubert, C., Rosen, J., Clark, A. G., Feschotte, C., et al. (2020). RepeatModeler2 for Automated Genomic Discovery of Transposable Element Families. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 9451–9457. doi:10.1073/pnas.1921046117

Fujimoto, T., Nishimura, T., Goto-Kazeto, R., Kawakami, Y., Yamaha, E., and Arai, K. (2010). Sexual Dimorphism of Gonadal Structure and Gene Expression in Germ Cell-Deficient Loach, a Teleost Fish. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107, 17211–17216. doi:10.1073/pnas.1007032107

Gammerdinger, W. J., and Kocher, T. D. (2018). Unusual Diversity of Sex Chromosomes in African Cichlid Fishes. Genes 9 (10), 480. doi:10.3390/genes9100480

Gammerdinger, W. J., Conte, M. A., Acquah, E. A., Roberts, R. B., and Kocher, T. D. (2014). Structure and Decay of a Proto-Y Region in Tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus. BMC Genomics 15, 975. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-15-975

Gammerdinger, W. J., Conte, M. A., Baroiller, J.-F., D’Cotta, H., and Kocher, T. D. (2016). Comparative Analysis of a Sex Chromosome from the Blackchin Tilapia,. Sarotherodon melanotheron. BMC Genomics 17, 808. doi:10.1186/s12864-016-3163-7

Gammerdinger, W. J., Conte, M. A., Sandkam, B. A., Penman, D. J., and Kocher, T. D. (2019). Characterization of Sex Chromosomes in Three Deeply Diverged Species of Pseudocrenilabrinae (Teleostei: Cichlidae). Hydrobiologia 832, 397–408. doi:10.1007/s10750-018-3778-6

Griffiths-Jones, S., Bateman, A., Marshall, M., Khanna, A., and Eddy, S. R. (2003). Rfam: An RNA Family Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 439–441. doi:10.1093/nar/gkg006

Haas, B. J., Salzberg, S. L., Zhu, W., Pertea, M., Allen, J. E., Orvis, J., et al. (2008). Automated Eukaryotic Gene Structure Annotation Using EVidenceModeler and the Program to Assemble Spliced Alignments. Genome Biol. 9 (1), R7. doi:10.1186/gb-2008-9-1-r7

Han, Y., and Wessler, S. R. (2010). MITE-Hunter: A Program for Discovering Miniature Inverted-Repeat Transposable Elements from Genomic Sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, e199. doi:10.1093/nar/gkq862

Hughes, L. C., Ortí, G., Huang, Y., Sun, Y., Baldwin, C. C., Thompson, A. W., et al. (2018). Comprehensive Phylogeny of ray-finned Fishes (Actinopterygii) Based on Transcriptomic and Genomic Data. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 6249–6254. doi:10.1073/pnas.1719358115

Katoh, K., Misawa, K., Kuma, K., and Miyata, T. (2002). MAFFT: A Novel Method for Rapid Multiple Sequence Alignment Based on Fast Fourier Transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 3059–3066. doi:10.1093/nar/gkf436

Keilwagen, J., Wenk, M., Erickson, J. L., Schattat, M. H., Grau, J., and Hartung, F. (2016). Using Intron Position Conservation for Homology-Based Gene Prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 44 (9), e89. doi:10.1093/nar/gkw092

Kikuchi, K., and Hamaguchi, S. (2013). Novel Sex-Determining Genes in Fish and Sex Chromosome Evolution. Dev. Dyn. 242, 339–353. doi:10.1002/dvdy.23927

Kobayashi, T., Kajiura-Kobayashi, H., Guan, G., and Nagahama, Y. (2008). Sexual Dimorphic Expression of DMRT1 and Sox9a during Gonadal Differentiation and Hormone-Induced Sex Reversal in the Teleost Fish Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Dev. Dyn. 237, 297–306. doi:10.1002/dvdy.21409

Kofler, R., Pandey, R. V., and Schlotterer, C. (2011). PoPoolation2: Identifying Differentiation between Populations Using Sequencing of Pooled DNA Samples (Pool-Seq). Bioinformatics 27, 3435–3436. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btr589

Kozomara, A., Birgaoanu, M., and Griffiths-Jones, S. (2019). miRBase: From microRNA Sequences to Function. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D155–D162. doi:10.1093/nar/gky1141

Lagesen, K., Hallin, P., Rødland, E. A., Stærfeldt, H.-H., Rognes, T., and Ussery, D. W. (2007). RNAmmer: Consistent and Rapid Annotation of Ribosomal RNA Genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, 3100–3108. doi:10.1093/nar/gkm160

Langmead, B., and Salzberg, S. L. (2012). Fast Gapped-Read Alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359. doi:10.1038/nmeth.1923

Lee, B.-Y., Penman, D. J., and Kocher, T. D. (2003). Identification of a Sex-Determining Region in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) Using Bulked Segregant Analysis. Anim. Genet. 34, 379–383. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2052.2003.01035.x

Lee, I. H., Sohn, M., Lim, H. J., Yoon, S., Oh, H., Shin, S., et al. (2014). Ahnak Functions as a Tumor Suppressor via Modulation of TGFβ/Smad Signaling Pathway. Oncogene 33, 4675–4684. doi:10.1038/onc.2014.69

Li, L., Stoeckert, C. J., and Roos, D. S. (2003). OrthoMCL: Identification of Ortholog Groups for Eukaryotic Genomes. Genome Res. 13, 2178–2189. doi:10.1101/gr.1224503

Li, H., Handsaker, B., Wysoker, A., Fennell, T., Ruan, J., Homer, N., et al. (2009). The Sequence Alignment/Map Format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352

Li, M., Sun, Y., Zhao, J., Shi, H., Zeng, S., Ye, K., et al. (2015). A Tandem Duplicate of Anti-müllerian Hormone with a Missense SNP on the Y Chromosome Is Essential for Male Sex Determination in Nile Tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus. Plos Genet. 11, e1005678. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005678

Li, Y. L., Xing, T. F., and Liu, J. X. (2020). Genome‐Wide Association Analyses Based on Whole‐Genome Sequencing of Protosalanx hyalocranius Provide Insights into Sex Determination of Salangid Fishes. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 20, 1038–1049. doi:10.1111/1755-0998.13172

Li, M., Zhang, R., Fan, G., Xu, W., Zhou, Q., Wang, L., et al. (2021). Reconstruction of the Origin of a Neo-Y Sex Chromosome and its Evolution in the Spotted Knifejaw, Oplegnathus punctatus. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 2615–2626. doi:10.1093/molbev/msab056

Li, H. (2013). Aligning Sequence Reads, Clone Sequences and Assembly Contigs with BWA-MEM). arXiv:1303.3997.

Lowe, T. M., and Eddy, S. R. (1997). tRNAscan-SE: A Program for Improved Detection of Transfer RNA Genes in Genomic Sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 955–964. doi:10.1093/nar/25.5.955

Mair, G. C., Abucay, J. S., Beardmore, J. A., and Skibinski, D. O. F. (1995). Growth Performance Trials of Genetically Male tilapia (GMT) Derived from YY-Males in Oreochromis niloticus L.: On Station Comparisons with Mixed Sex and Sex Reversed Male Populations. Aquaculture 137, 313–323. doi:10.1016/0044-8486(95)01110-2

Matschiner, M., Böhne, A., Ronco, F., and Salzburger, W. (2020). The Genomic Timeline of Cichlid Fish Diversification Across Continents. Nat. Commun. 11, 5895. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-17827-9

Matsuda, M. (2005). Sex Determination in the Teleost Medaka, Oryzias latipes. Annu. Rev. Genet. 39, 293–307. doi:10.1146/annurev.genet.39.110304.095800

McKenna, A., Hanna, M., Banks, E., Sivachenko, A., Cibulskis, K., Kernytsky, A., et al. (2010). The Genome Analysis Toolkit: A MapReduce Framework for Analyzing Next-Generation DNA Sequencing Data. Genome Res. 20, 1297–1303. doi:10.1101/gr.107524.110

Mello, B. (2018). Estimating TimeTrees with MEGA and the TimeTree Resource. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 2334–2342. doi:10.1093/molbev/msy133

Micheletti, S. J., and Narum, S. R. (2018). Utility of Pooled Sequencing for Association Mapping in Nonmodel Organisms. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 18, 825–837. doi:10.1111/1755-0998.12784

Nagahama, Y. (2005). Molecular Mechanisms of Sex Determination and Gonadal Sex Differentiation in Fish. Fish. Physiol. Biochem. 31, 105–109. doi:10.1007/s10695-006-7590-2

Nakamoto, M., Uchino, T., Koshimizu, E., Kuchiishi, Y., Sekiguchi, R., Wang, L., et al. (2021). A Y-Linked Anti-Müllerian Hormone Type-II Receptor Is the Sex-Determining Gene in Ayu,. Plecoglossus altivelis. Plos Genet. 17, e1009705. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1009705

Nawrocki, E. P., and Eddy, S. R. (2013). Infernal 1.1: 100-Fold Faster RNA Homology Searches. Bioinformatics 29, 2933–2935. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btt509

Palaiokostas, C., Bekaert, M., Khan, M. G., Taggart, J. B., Gharbi, K., McAndrew, B. J., et al. (2015). A Novel Sex-Determining QTL in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). BMC Genomics 16, 171. doi:10.1186/s12864-015-1383-x

Palmer, D. H., Rogers, T. F., Dean, R., and Wright, A. E. (2019). How to Identify Sex Chromosomes and Their Turnover. Mol. Ecol. 28, 4709–4724. doi:10.1111/mec.15245

Pan, Q., Feron, R., Yano, A., Guyomard, R., Jouanno, E., Vigouroux, E., et al. (2019). Identification of the Master Sex Determining Gene in Northern pike (Esox lucius) Reveals Restricted Sex Chromosome Differentiation. Plos Genet. 15, e1008013. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1008013

Pan, Q., Feron, R., Jouanno, E., Darras, H., Herpin, A., Koop, B., et al. (2021a). The Rise and Fall of the Ancient Northern pike Master Sex-Determining Gene. Elife 10, e62858. doi:10.7554/eLife.62858

Pan, Q., Kay, T., Depincé, A., Adolfi, M., Schartl, M., Guiguen, Y., et al. (2021b). Evolution of Master Sex Determiners: TGF-β Signalling Pathways at Regulatory Crossroads. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 376, 20200091. doi:10.1098/rstb.2020.0091

Parra, G., Bradnam, K., and Korf, I. (2007). CEGMA: A Pipeline to Accurately Annotate Core Genes in Eukaryotic Genomes. Bioinformatics 23, 1061–1067. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btm071

Peichel, C. L., McCann, S. R., Ross, J. A., Naftaly, A. F. S., Urton, J. R., Cech, J. N., et al. (2020). Assembly of the Threespine Stickleback Y Chromosome Reveals Convergent Signatures of Sex Chromosome Evolution. Genome Biol. 21, 177. doi:10.1186/s13059-020-02097-x

Pertea, M., Pertea, G. M., Antonescu, C. M., Chang, T.-C., Mendell, J. T., and Salzberg, S. L. (2015). StringTie Enables Improved Reconstruction of a Transcriptome from RNA-Seq Reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 290–295. doi:10.1038/nbt.3122

Qu, M., Liu, Y., Zhang, Y., Wan, S., Ravi, V., Qin, G., et al. (2021). Seadragon Genome Analysis Provides Insights into its Phenotype and Sex Determination Locus. Sci. Adv. 7 (34), eabg5196. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abg5196

Quinlan, A. R., and Hall, I. M. (2010). BEDTools: A Flexible Suite of Utilities for Comparing Genomic Features. Bioinformatics 26, 841–842. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btq033

Rao, S. S. P., Huntley, M. H., Durand, N. C., Stamenova, E. K., Bochkov, I. D., Robinson, J. T., et al. (2014). A 3D Map of the Human Genome at Kilobase Resolution Reveals Principles of Chromatin Looping. Cell 159, 1665–1680. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.021

Roberts, N. B., Juntti, S. A., Coyle, K. P., Dumont, B. L., Stanley, M. K., Ryan, A. Q., et al. (2016). Polygenic Sex Determination in the Cichlid Fish Astatotilapia burtoni. BMC Genomics 17, 835. doi:10.1186/s12864-016-3177-1

Ronco, F., Matschiner, M., Böhne, A., Boila, A., Büscher, H. H., El Taher, A., et al. (2021). Drivers and Dynamics of a Massive Adaptive Radiation in Cichlid Fishes. Nature 589, 76–81. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2930-4

Schartl, M. (2004). A Comparative View on Sex Determination in Medaka. Mech. Develop. 121, 639–645. doi:10.1016/j.mod.2004.03.001

Ser, J. R., Roberts, R. B., and Kocher, T. D. (2010). Multiple Interacting Loci Control Sex Determination in Lake Malawi Cichlid Fish. Evolution 64, 486–501. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00871.x

Simão, F. A., Waterhouse, R. M., Ioannidis, P., Kriventseva, E. V., and Zdobnov, E. M. (2015). BUSCO: Assessing Genome Assembly and Annotation Completeness with Single-Copy Orthologs. Bioinformatics 31, 3210–3212. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351

Stamatakis, A. (2006). RAxML-VI-HPC: Maximum Likelihood-Based Phylogenetic Analyses with Thousands of Taxa and Mixed Models. Bioinformatics 22, 2688–2690. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btl446

Stanke, M., Keller, O., Gunduz, I., Hayes, A., Waack, S., and Morgenstern, B. (2006). AUGUSTUS: Ab Initio Prediction of Alternative Transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, W435–W439. doi:10.1093/nar/gkl200

Tao, W., Chen, J., Tan, D., Yang, J., Sun, L., Wei, J., et al. (2018). Transcriptome Display during Tilapia Sex Determination and Differentiation as Revealed by RNA-Seq Analysis. BMC Genomics 19, 363. doi:10.1186/s12864-018-4756-0

Tao, W., Xu, L., Zhao, L., Zhu, Z., Wu, X., Min, Q., et al. (2021). High‐Quality Chromosome‐Level Genomes of Two tilapia Species Reveal Their Evolution of Repeat Sequences and Sex Chromosomes. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 21, 543–560. doi:10.1111/1755-0998.13273

Taslima, K., Khan, M. G. Q., McAndrew, B. J., and Penman, D. J. (2021). Evidence of Two XX/XY Sex-Determining Loci in the Stirling Stock of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Aquaculture 532, 735995. doi:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2020.735995

Uchida, D., Yamashita, M., Kitano, T., and Iguchi, T. (2004). An Aromatase Inhibitor or High Water Temperature Induce Oocyte Apoptosis and Depletion of P450 Aromatase Activity in the Gonads of Genetic Female Zebrafish during Sex-Reversal. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A: Mol. Integr. Physiol. 137, 11–20. doi:10.1016/s1095-6433(03)00178-8

Van der Auwera, G. A., Carneiro, M. O., Hartl, C., Poplin, R., Del Angel, G., Levy-Moonshine, A., et al. (2013). From FastQ Data to High Confidence Variant Calls: The Genome Analysis Toolkit Best Practices Pipeline. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics 43 (1110), 11.10.1–11.10.33. doi:10.1002/0471250953.bi1110s43

Wang, X., and Wang, L. (2016). GMATA: An Integrated Software Package for Genome-Scale SSR Mining, Marker Development and Viewing. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 1350. doi:10.3389/fpls.2016.01350

Wang, Y., Guan, X., Fok, K. L., Li, S., Zhang, X., Miao, S., et al. (2008). A Novel Member of the Rhomboid Family, RHBDD1, Regulates BIK-Mediated Apoptosis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65, 3822–3829. doi:10.1007/s00018-008-8452-0

Wang, Y., Song, W., Li, S., Guan, X., Miao, S., Zong, S., et al. (2009). GC-1 mRHBDD1 Knockdown Spermatogonia Cells Lose Their Spermatogenic Capacity in Mouse Seminiferous Tubules. Bmc Cel Biol 10, 25. doi:10.1186/1471-2121-10-25

Wang, K., Li, M., and Hakonarson, H. (2010). ANNOVAR: Functional Annotation of Genetic Variants from High-Throughput Sequencing Data. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, e164. doi:10.1093/nar/gkq603

Wang, Y., Tang, H., Debarry, J. D., Tan, X., Li, J., Wang, X., et al. (2012). MCScanX: A Toolkit for Detection and Evolutionary Analysis of Gene Synteny and Collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, e49. doi:10.1093/nar/gkr1293

Wen, M., Feron, R., Pan, Q., Guguin, J., Jouanno, E., Herpin, A., et al. (2020). Sex Chromosome and Sex Locus Characterization in Goldfish, Carassius auratus (Linnaeus, 1758). BMC Genomics 21, 552. doi:10.1186/s12864-020-06959-3

Wick, R. R., Judd, L. M., and Holt, K. E. (2019). Performance of Neural Network Basecalling Tools for Oxford Nanopore Sequencing. Genome Biol. 20, 129. doi:10.1186/s13059-019-1727-y

Wright, A. E., Dean, R., Zimmer, F., and Mank, J. E. (2016). How to Make a Sex Chromosome. Nat. Commun. 7, 12087. doi:10.1038/ncomms12087

Wu, B., Feng, C., Zhu, C., Xu, W., Yuan, Y., Hu, M., et al. (2021). The Genomes of Two Billfishes Provide Insights into the Evolution of Endothermy in Teleosts. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 2413–2427. doi:10.1093/molbev/msab035

Xue, L., Gao, Y., Wu, M., Tian, T., Fan, H., Huang, Y., et al. (2021). Telomere-to-Telomere Assembly of a Fish Y Chromosome Reveals the Origin of a Young Sex Chromosome Pair. Genome Biol. 22, 203. doi:10.1186/s13059-021-02430-y

Keywords: Mozambique tilapia, genome, sex chromosome, sex determining region, transition

Citation: Tao W, Cao J, Xiao H, Zhu X, Dong J, Kocher TD, Lu M and Wang D (2021) A Chromosome-Level Genome Assembly of Mozambique Tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus) Reveals the Structure of Sex Determining Regions. Front. Genet. 12:796211. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2021.796211

Received: 16 October 2021; Accepted: 15 November 2021;

Published: 08 December 2021.

Edited by:

Shaojun Liu, Hunan Normal University, ChinaCopyright © 2021 Tao, Cao, Xiao, Zhu, Dong, Kocher, Lu and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Deshou Wang, d2Rlc2hvdUBzd3UuZWR1LmNu; Maixin Lu, bWFpeGluLWx1QHByZnJpLmFjLmNu

†These authors have Contributed equally to this work

Wenjing Tao

Wenjing Tao Jianmeng Cao

Jianmeng Cao Hesheng Xiao

Hesheng Xiao Xi Zhu

Xi Zhu Junjian Dong

Junjian Dong Thomas D. Kocher

Thomas D. Kocher Maixin Lu

Maixin Lu Deshou Wang

Deshou Wang