95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

CASE REPORT article

Front. Genet. , 01 December 2021

Sec. Genetics of Common and Rare Diseases

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2021.761003

This article is part of the Research Topic Developmental Delay and Intellectual Disability View all 22 articles

7q terminal deletion syndrome is a rare condition presenting with multiple congenital malformations, including abnormal brain and facial structures, developmental delay, intellectual disability, abnormal limbs, and sacral anomalies. At least 40 OMIM genes located in the 7q34-7q36.3 region act as candidate genes for these phenotypes, of which SHH, EN2, KCNH2, RHEB, HLXB9, EZH2, MNX1 and LIMR1 may be the most important. In this study, we discuss the case of a 2.5-year-old male patient with multiple malformations, congenital brain dysplasia, developmental delay, and intellectual disability. A high-resolution genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphism array and real-time polymerase chain reaction were performed to detect genetic lesions. A de novo 9.4 Mb deletion in chromosome region 7q35-7q36.3 (chr7:147,493,985–156,774,460) was found. This chromosome region contains 68 genes, some of which are candidate genes for each phenotype. To the best of our knowledge, this is a rare case report of 7q terminal deletion syndrome in a Chinese patient. Our study identifies a rare phenotype in terms of brain structure abnormalities and cerebellar sulcus widening in patients with deletion in 7q35-7q36.3.

The 7q deletion syndrome is a rare genetic disorder caused by the deletion of the long arm of chromosome 7 (Ayub et al., 2016). This 7q deletion was first described in patients with unusual facial structure and delayed mental and physical development, and was consequently defined as a syndrome in 1977 (Harris et al., 1977). The characteristic features of the 7q deletion include developmental delay, intellectual disability, behavioral problems, and distinctive facial features; penoscrotal transposition or ulnar ray deficiency, Kaposi sarcoma, oral malformations, mitral dysplasia, and scoliosis have also been reported (Lewis et al., 1996).

Relatively little is known regarding 7q terminal deletions in contiguous gene deletion syndrome. The typical clinical features of 7q terminal deletion syndrome include abnormal brain and facial structures, developmental delay, intellectual disability, abnormal limbs, and sacral anomalies (Rush et al., 2013; Jackson et al., 2017). At present, 7q terminal deletion syndrome has only been described in 28 patients, most of whom had 7q36 microdeletions (Jackson et al., 2017). This region contains more than 40 OMIM genes, of which SHH, EN2, KCNH2, RHEB, HLXB9, EZH2, MNX1 and LIMR1 have been nominated as candidate dosage-sensitive key genes of clinical significance associated with this disorder (Rush et al., 2013; Coutton et al., 2014; Hyohyeon and Lee, 2015; Ayub et al., 2016; Jackson et al., 2017).

Majority of previous published cases were based on traditional G-banding resolution, which is inadequate to define cryptic interstitial deletion in the terminal region. With the development of SNP array technology, which can determine the precise breakpoints instead of terminal deletion, majority of these cases are found as de novo in origin. Here, we describe the case of a 2.5-year-old boy with multiple malformations, including congenital brain dysplasia, developmental delay, and intellectual disability, carrying a 9.4 Mb microdeletion in 7q35-7q36.3 (chr7:147,493,985–156,774,460).

The patient was a 2.5-year-old boy who first presented to the Department of Pediatrics of Hebei General Hospital due to developmental delay. Both his parents were healthy and were never exposed to undesirable substances, such as poisons and radiation. A family history of birth defects was absent. Pregnancy hypertension occurred at 34 weeks of pregnancy. At that time, B-mode ultrasound suggested that the fetus was 2 weeks less advanced and the head circumference was 3 weeks less advanced than the actual gestational age. Therefore, the mother underwent cesarean delivery.

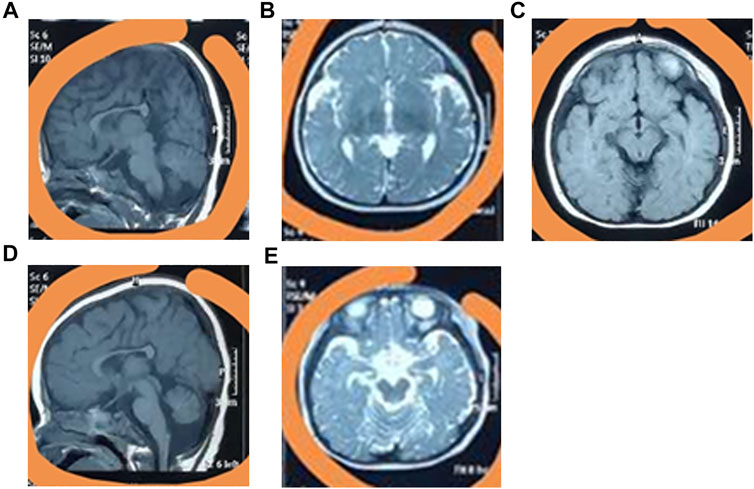

The baby was bruised, and exhibited feeding difficulties after birth, with an Apgar score of 6. At six-months-old, he could sit with the help of external objects. At 9 months old, he could not crawl. The baby began to speak at 1.5 years old but could only enunciate simple words, and even now he cannot say full sentences. At present, the patient has a normal weight (11.5 kg) and height (90 cm), but a small head circumference (42 cm), eye crack, broad ears, and a pointed chin (Supplementary Figure S1). Furthermore, the patient cannot walk independently. Brain MRI revealed overt carcass dysplasia (Figure 1A), bilateral forehead subarachnoid space widening (Figure 1B), right iliac choroidal fissure cyst (Figure 1C), large cisterna magna (Figure 1D), and cerebellar sulcus widening (Figure 1E).

FIGURE 1. The clinical phenotypes of the patient. The MRI testing identified the overt carcass dysplasia (A), bilateral forehead subarachnoid space widening (B), right iliac choroidal fissure cyst (C), large cisterna magna (D), and cerebellar sulcus widening (E).

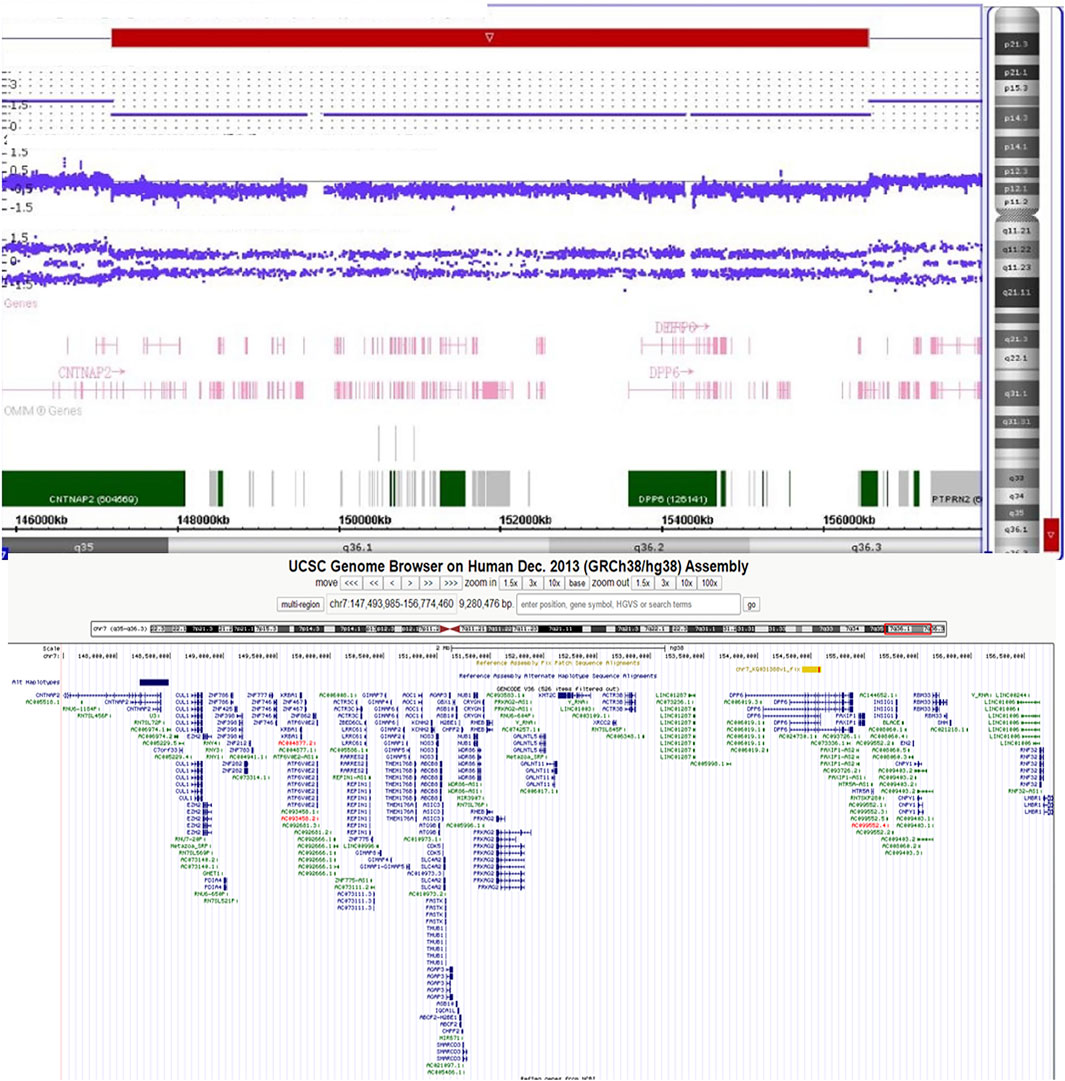

Banding cytogenetic results of the patient revealed a deletion of the long arm of chromosome 7, described as 46,XY,del (7)(q36). His parents’ karyotypes were normal (Supplementary Figure S2). We subsequently performed single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array with Human660W-Quad Chip (Illumina Inc., San Diego, United States) to analyze any genetic lesions. A total of 173 CNVs were identified in the proband. Compared with the database of Genomic Variants, a de novo 9.4 Mb deletion ranging from 7q35 to q36.3 (chr7:147,493,985–156,774,460) (hg 38) was detected (Figure 2). This chromosome region contains approximately 68 genes, including CNTNAP2, AGAP3, CDK5, CUL1, KMT2C, XRCC2, DPP6, HTR5A, EN2, SHH, LMBR1, KCNH2, PRKAG2, and EZH2. The patient’s parents did not carry this genomic lesion. Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction with part of the genomic DNA (SHH gene, the primers were as follows: forward: 5-GCAAGTGGCAACTCACCTA-3, reverse: 5-TTTATTTACCTCAGGCCCTAACC-3) of the trio (the proband and his parents) further confirmed this de novo deletion (Supplementary Figure S3).

FIGURE 2. The SNP array identified a 7q35-7q36.3 (chr7:147,493,985–156,774,460) deletion in the patient.

7q terminal deletion syndrome is a rare disorder worldwide. Currently, there have been very few reports in the Chinese population. In this study, we report a heterozygous 9.4 Mb microdeletion of 7q35-q36.3 (chr7:147,493,985–156,774,460) in a 2.5-year-old boy with congenital brain dysplasia, developmental delay, and intellectual disability. The findings of our study are consistent with those of previous studies and report that microdeletion in the 7q terminal may lead to abnormal brain and facial structures, developmental delay, and intellectual disability (Linhares et al., 2014; Busa et al., 2016).

There are several significant genes located in the region of 7q35-q36.3 (chr7:147,493,985–156,774,460). Previous studies have shown that mutations in CNTNAP2, KMT2C, EN2 and EZH2 can lead to intellectual disability and autism spectrum disorder (Penagarikano et al., 2011; Sundaram et al., 2014; Koemans et al., 2017; Suri and Dixit, 2017); CDK5 is required for proper development of the mammalian central nervous system (Alvarez-Periel et al., 2018), AGAP3 can regulate synaptic plasticity (Oku and Huganir, 2013), XRCC2 is required for embryonic neurogenesis (Deans et al., 2000), DPP6 mutations may explain the lateral sclerosis (van Es et al., 2008), and HTR5A is a candidate gene for schizophrenia (Guan et al., 2016). These findings may explain congenital brain dysplasia and intellectual disability phenotypes. Furthermore, DPP6 encodes a dipeptidyl-peptidase-like protein expressed predominantly in the brain, with very high expression in the cerebellum, which may explain the new phenotype of cerebellar sulcus widening (van Es et al., 2008). Finally, CUL1 can regulate the β-catenin and Wnt pathways, which play a crucial role in body development (Wei et al., 2007).

In fact, another four genes (SHH, LMBR1, KCNH2, and PRKAG2) may also affect the phenotypes of 7q terminal deletion syndrome (Hyohyeon and Lee, 2015; Jackson et al., 2017). First, SHH and LMBR1 are responsible for bone and tooth development; therefore, most 7q terminal deletion patients may show microcephaly, abnormal hand, and scoliosis (Rush et al., 2013). In our case, the head circumference was smaller than that in normal individuals, which may have been caused by the haploinsufficiency of the SHH and LMBR1 genes. In addition, two other genes of interest were KCNH2 and PRKAG2; KCNH2 is a candidate gene of Long QT syndrome (Tuveng et al., 2018) and mutations in PRKAG2 may lead to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (Porto et al., 2016). However, most 7q terminal deletion patients show no obvious cardiovascular disorders. In our study, the patient also did not have cardiovascular disease, but we think 7q terminal deletion patients may have a high risk for the future development of cardiovascular disorders, and we will continue to follow the patient.

We summarized the 16 reported patients with 7q35-7q36 microdeletion, and found that facial deformities, growth retardation, intellectual disability, speech delay, and poor attention were the common phenotypes in 7q35-7q36 microdeletion patients (Table1; Figure 3), and the 7q36.1-7q36.3 including EZH2, MNX1 and SHH may be the critical region of the 7q deletion syndrome which is responsible for facial malformation, developmental delay and intellectual disability (Coutton et al., 2014; Hyohyeon and Lee, 2015; Suri and Dixit, 2017). However, other phenotypes, including abnormal limbs, hearing loss, seizures, short stature, heart defects, and urogenital anomalies have been rarely reported. Meanwhile, most cases with 7q35-7q36 microdeletion have been reported in the United States population (Roessler et al., 1996). Compared to reported cases with 7q35-7q36 microdeletion, we did not observe any limb abnormalities, hearing loss, seizures, short stature, heart defect, or urogenital anomalies in our case. Simultaneously, brain structure abnormalities were only reported in three cases with 7q35-7q36 microdeletions. Caselli et al. reported the hypoplasia of the corpus callosum in a 9-year-old girl with a 5.27 Mb deletion in 7q36.1-q36.2 (Caselli et al., 2008). In 2010, Petrin et al. described cerebellar atrophy in a Brazilian stuttering case with a 10 Mb deletion of chromosome region 7q33-35 (Petrin et al., 2010). Afterwards, Pelegrino et al. reported the hypoplasia of corpus callosum and white matter reduction in a child with a deletion of 7q36.1–36.3 and duplication of 9p22.3–23 (Pelegrino et al., 2013). All the reported 7q35-7q36 microdeletions cases brain structure abnormalities were shown hypoplasia of the corpus callosum. Here, in our study, the case not only presented with hypoplasia of the corpus callosum, but also showed cerebellar sulcus widening, which has not been reported in previous 7q35-7q36 microdeletion patients.

In conclusion, we reported a de novo 9.4 Mb deletion ranging from 7q35 to q36.3 (chr7:147,493,985–156,774,460) in a patient with congenital brain dysplasia, developmental delay, and intellectual disability identified via SNP array analysis. Our study together with literature review indicated that 7q terminal deletion can be redefined as a contiguous 7q deletion syndrome, similar to other contiguous deletion syndromes, in which different regions and breakpoints gave an overlapping phenotype.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Hebei General hospital. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s), and minor(s)’ legal guardian/next of kin, for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Y-LL enrolled the samples; YS and L-LF performed the SNP-array experiment and Real-time PCR. C-YW isolated the DNA; YS and L-LF wrote the draft; Y-LL and J-SL revised the manuscript and support the project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82,000,427 and 82,070,738), Hunan Province Natural Science Foundation (2020JJ5785 and 2021JJ31015), Research Project of Hunan Provincial Health Commission (202,103,012,102, 202,103,050,563 and 202,104,022,248), 2020 Education Reform Project of Central South University (2020jy172) and the Fundamental Research Funds for Central Universities of Central South University (2021zzts0570).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We thank all subjects for participating in this study. We thank Shuai Guo from University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, the United States for editing the language.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgene.2021.761003/full#supplementary-material

Alvarez-Periel, E., Puigdellívol, M., Brito, V., Plattner, F., Bibb, J. A., Alberch, J., et al. (2018). Cdk5 Contributes to Huntington's Disease Learning and Memory Deficits via Modulation of Brain Region-specific Substrates. Mol. Neurobiol. 55 (8), 6250–6268. doi:10.1007/s12035-017-0828-4

Ayub, S., Gadji, M., Krabchi, K., Côté, S., Gekas, J., Maranda, B., et al. (2016). Three New Cases of Terminal Deletion of the Long Arm of Chromosome 7 and Literature Review to Correlate Genotype and Phenotype Manifestations. Am. J. Med. Genet. 170 (4), 896–907. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.37428

Busa, T., Panait, N., Chaumoitre, K., Philip, N., and Missirian, C. (2016). Esophageal Atresia with Tracheoesophageal Fistula in a Patient with 7q35-36.3 Deletion Including SHH Gene. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 59 (10), 546–548. doi:10.1016/j.ejmg.2016.09.001

Caselli, R., Mencarelli, M. A., Papa, F. T., Ariani, F., Longo, I., Meloni, I., et al. (2008). Delineation of the Phenotype Associated with 7q36.1q36.2 Deletion: Long QT Syndrome, Renal Hypoplasia and Mental Retardation. Am. J. Med. Genet. 146A (9), 1195–1199. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.32197

Coutton, C., Poreau, B., Devillard, F., Durand, C., Odent, S., Rozel, C., et al. (2013). Currarino Syndrome and HPE Microform Associated with a 2.7-Mb Deletion in 7q36.3 ExcludingSHHGene. Mol. Syndromol 5 (1), 25–31. doi:10.1159/000355391

Deans, B., Griffin, C. S., Maconochie, M., and Thacker, J. (2000). Xrcc2 Is Required for Genetic Stability, Embryonic Neurogenesis and Viability in Mice. EMBO J. 19 (24), 6675–6685. doi:10.1093/emboj/19.24.6675

Guan, F., Lin, H., Chen, G., Li, L., Chen, T., Liu, X., et al. (2016). Evaluation of Association of Common Variants in HTR1A and HTR5A with Schizophrenia and Executive Function. Sci. Rep. 6, 38048. doi:10.1038/srep38048

Harris, E. L., Wappner, R. S., Palmer, C. G., Hall, B., Dinno, N., Seashore, M. R., et al. (1977). 7q Deletion Syndrome (7q32 Leads to 7qter). Clin. Genet. 12 (4), 233–238.

Hyohyeon, C., and Lee, C. G. (2015). A 13-Year-Old Boy with a 7q36.1q36.3 Deletion with Additional Findings. Am. J. Med. Genet. 167 (1), 198–203. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.36792

Jackson, C. C., Lefèvre-Utile, A., Guimier, A., Malan, V., Bruneau, J., Gessain, A., et al. (2017). Kaposi Sarcoma, Oral Malformations, Mitral Dysplasia, and Scoliosis Associated with 7q34-q36.3 Heterozygous Terminal Deletion. Am. J. Med. Genet. 173 (7), 1858–1865. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.38275

Koemans, T. S., Kleefstra, T., Chubak, M. C., Stone, M. H., Reijnders, M. R. F., de Munnik, S., et al. (2017). Functional Convergence of Histone Methyltransferases EHMT1 and KMT2C Involved in Intellectual Disability and Autism Spectrum Disorder. Plos Genet. 13 (10), e1006864. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1006864

Lewis, S., Abrahamson, G., Boultwood, J., Fidler, C., Potter, A., and Wainscoat, J. S. (1996). Molecular Characterization of the 7q Deletion in Myeloid Disorders. Br. J. Haematol. 93 (1), 75–80. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2141.1996.4841025.x

Linhares, N. D., Svartman, M., Salgado, M. I., Rodrigues, T. C., da Costa, S. S., Rosenberg, C., et al. (2014). Dental Developmental Abnormalities in a Patient with Subtelomeric 7q36 Deletion Syndrome May Confirm a Novel Role for the SHH Gene. Meta Gene 2, 16–24. doi:10.1016/j.mgene.2013.10.005

Oku, Y., and Huganir, R. L. (2013). AGAP3 and Arf6 Regulate Trafficking of AMPA Receptors and Synaptic Plasticity. J. Neurosci. 33 (31), 12586–12598. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0341-13.2013

Pelegrino, K. d. O., Sugayama, S., Catelani, A. L., Lezirovitz, K., Kok, F., and Chauffaille, M. d. L. (2013). 7q36 Deletion and 9p22 Duplication: Effects of a Double Imbalance. Mol. Cytogenet. 6 (1), 2. doi:10.1186/1755-8166-6-2

Peñagarikano, O., Abrahams, B. S., Herman, E. I., Winden, K. D., Gdalyahu, A., Dong, H., et al. (2011). Absence of CNTNAP2 Leads to Epilepsy, Neuronal Migration Abnormalities, and Core Autism-Related Deficits. Cell 147 (1), 235–246. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.040

Petrin, A. L., Giacheti, C. M., Maximino, L. P., Abramides, D. V. M., Zanchetta, S., Rossi, N. F., et al. (2010). Identification of a Microdeletion at the 7q33-Q35 Disrupting the CNTNAP2 Gene in a Brazilian Stuttering Case. Am. J. Med. Genet. 152A (12), 3164–3172. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.33749

Porto, A. G., Brun, F., Severini, G. M., Losurdo, P., Fabris, E., Taylor, M. R. G., et al. (2016). Clinical Spectrum of PRKAG2 Syndrome. Circ. Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 9 (1), e003121. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.115.003121.e003121

Roessler, E., Belloni, E., Gaudenz, K., Jay, P., Berta, P., Scherer, S. W., et al. (1996). Mutations in the Human Sonic Hedgehog Gene Cause Holoprosencephaly. Nat. Genet. 14 (3), 357–360. doi:10.1038/ng1196-357

Rush, E. T., Stevens, J. M., Sanger, W. G., and Olney, A. H. (2013). Report of a Patient with Developmental Delay, Hearing Loss, Growth Retardation, and Cleft Lip and Palate and a Deletion of 7q34-36.1: Review of Distal 7q Deletions. Am. J. Med. Genet. 161 (7), 1726–1732. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.35951

Sundaram, S., Huq, A. H. M., Hsia, T., and Chugani, H. (2014). Exome Sequencing and Diffusion Tensor Imaging in Developmental Disabilities. Pediatr. Res. 75 (3), 443–447. doi:10.1038/pr.2013.234

Suri, T., and Dixit, A. (2017). The Phenotype of EZH2 haploinsufficiency-1.2‐Mb Deletion at 7q36.1 in a Child with Tall Stature and Intellectual Disability. Am. J. Med. Genet. 173 (10), 2731–2735. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.38356

Tuveng, J. M., Berling, B.-M., Bunford, G., Vanoye, C. G., Welch, R. C., Leren, T. P., et al. (2018). Long QT Syndrome KCNH2 Mutation with Sequential Fetal and Maternal Sudden Death. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 14 (3), 367–371. doi:10.1007/s12024-018-9989-3

van Es, M. A., van Vught, P. W., Blauw, H. M., Franke, L., Saris, C. G., Van den Bosch, L., et al. (2008). Genetic Variation in DPP6 Is Associated with Susceptibility to Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Nat. Genet. 40 (1), 29–31. doi:10.1038/ng.2007.52

Wei, S., Lin, L.-F., Yang, C.-C., Wang, Y.-C., Chang, G.-D., Chen, H., et al. (2007). Thiazolidinediones Modulate the Expression of β-Catenin and Other Cell-Cycle Regulatory Proteins by Targeting the F-Box Proteins of Skp1-Cul1-F-Box Protein E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Independently of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor γ. Mol. Pharmacol. 72 (3), 725–733. doi:10.1124/mol.107.035287

Keywords: 7q terminal deletion syndrome, 7q35-7q363 deletion, SNP array, cerebellar sulcus widening, congenital brain dysplasia, developmental delay

Citation: Fan L-L, Sheng Y, Wang C-Y, Li Y-L and Liu J-S (2021) Case Report: Congenital Brain Dysplasia, Developmental Delay and Intellectual Disability in a Patient With a 7q35-7q36.3 Deletion. Front. Genet. 12:761003. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2021.761003

Received: 19 August 2021; Accepted: 05 November 2021;

Published: 01 December 2021.

Edited by:

Santasree Banerjee, Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI), ChinaReviewed by:

Mohammed Ali Al Balwi, King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences, Saudi ArabiaCopyright © 2021 Fan, Sheng, Wang, Li and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ya-Li Li, bHlsODcwM0BzaW5hLmNvbQ==; Ji-Shi Liu, amlzaGlsaXV4eTN5eUAxNjMuY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.