- 1Center for Reproduction and Genetics, The Affiliated Suzhou Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Suzhou, China

- 2Center for Reproduction and Genetics, Suzhou Municipal Hospital, Suzhou, China

Background: Whole-exome sequencing (WES) has been recommended as a first-tier clinical diagnostic test for individuals with neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs). We aimed to identify the genetic causes of 17 children with developmental delay (DD) and/or intellectual disability (ID).

Methods: WES and exome-based copy number variation (CNV) analysis were performed for 17 patients with unexplained DD/ID.

Results: Single-nucleotide variant (SNV)/small insertion or deletion (Indel) analysis and exome-based CNV calling yielded an overall diagnostic rate of 58.8% (10/17), of which diagnostic SNVs/Indels accounted for 41.2% (7/17) and diagnostic CNVs accounted for 17.6% (3/17).

Conclusion: Our findings expand the known mutation spectrum of genes related to DD/ID and indicate that exome-based CNV analysis could improve the diagnostic yield of patients with DD/ID.

Background

Developmental delay (DD) and intellectual disability (ID) are major manifestations of neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs) with a global prevalence of 1%–3% (Thapar et al., 2017; Ismail and Shapiro, 2019). DD/ID shows phenotypic pleiotropy, and the underlying cause of DD/ID is heterogeneous, in which genetic factors such as copy number variations (CNVs) and variants in single genes have been recognized as major reasons (Savatt and Myers, 2021). With the advent of next-generation sequencing (NGS), the field of genetics was transformed; and the number of genes known to be associated with DD/ID has increased significantly. For example, over 700 genes have been identified in X-linked, autosomal-dominant, and autosomal-recessive ID until 2015 (Vissers et al., 2016).

Chromosomal microarray has been recommended as a first-tier clinical test to identify chromosomal CNVs and regions of homozygosity in individuals with DD/ID, autism spectrum disorders (ASDs), or multiple congenital anomalies with a diagnostic yield of 15%–20% (Manning et al., 2010; Miller et al., 2010). Whole-exome sequencing (WES) could detect single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) and small insertions or deletions (Indels) by whole-exome capture and massively parallel DNA sequencing, which has a diagnostic advantage in situations of genetic heterogeneity or unknown causal genes compared with conventional tests of single gene or gene panels (Monroe et al., 2016). WES is also recommended as a first-tier clinical diagnostic test for individuals with NDDs with an overall diagnostic yield of 36%, including 31% for isolated NDD, and 53% for NDD plus associated conditions, which is greater than the diagnostic yield of CMA (15%–20%) (Srivastava et al., 2019). Recently, CNV calling has been performed by depth-of-sequence coverage analysis of WES data, which enables the detection of deletions and duplications at the exon level (Marchuk et al., 2018).

In this study, WES and exome-based CNV analysis were performed for 17 children with unexplained DD/ID, and a variety of diagnostic variants including SNVs/Indels and CNVs were identified, indicating that WES could help to identify their molecular etiology and the incorporation of CNV calling could improve the diagnostic rate.

Methods

Patients

This study was approved by the institutional ethics committee of the Affiliated Suzhou Hospital of Nanjing Medical University. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient’s parents. This study included 17 children with unexplained DD/ID referred to our center for reproduction and genetics, the affiliated Suzhou Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Suzhou, Jiangsu, China, from January 2018 to March 2021. The characteristics of each patient including age, gender, and main phenotypes are listed in Table 1, and their clinical details are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Global DD is defined as a delay in two or more developmental domains of cognition, speech/language, gross/fine motor, social/personal, and activities of daily living (Mithyantha et al., 2017). Severity of ID was determined based on the intelligence quotient (IQ): severe ID (IQ < 40), moderate ID (IQ range 40–60), and mild ID (IQ range 60–70). In the absence of IQ, ID was diagnosed by the pediatric neurologist or geneticist.

Whole-Exome Sequencing and Data Analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from the whole blood of the patients and their parents. WES was performed using the SureSelect Human All Exon Kit (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and Illumina NovaSeq 6,000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The sequencing reads were aligned to the human reference genome (hg19/GRCh37) using Burrows-Wheeler Aligner tool, and PCR duplicates were removed by Picard v1.57 (http://picard.sourceforge.net/). The fraction of target bases covered at least 20× should be over 96%, with an average sequencing depth on target bases of over 100×. GATK (https://software.broadinstitute.org/gatk/) was employed for identifying the SNVs and Indels. Variant annotation and interpretation were conducted by ANNOVAR (Wang et al., 2010). The variants were searched in the dbSNP (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/), 1000 Genomes Project database (http://www.1000genomes.org/), Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC) (http://exac.broadinstitute.org/), and the Genome Aggregation database (gnomAD) (http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/). The pathogenicity of mutations was predicted by PROVEAN (http://provean.jcvi.org), PolyPhen-2 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/), and MutationTaster (http://www.mutationtaster.org/). Disease and phenotype databases and published literature, such as OMIM (http://www.omim.org), ClinVar (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar), HGMD (http://www.hgmd.org), and PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed), were also searched. The variants were classified according to the Standards and Guidelines for the Interpretation of Sequence Variants released by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) and the Association for Molecular Pathology (Richards et al., 2015). Finally, the variants with minor allele frequency <0.05 were selected for further interpretation considering ACMG category, evidence of pathogenicity, clinical synopsis, and inheritance mode of associated disease.

Sanger Sequencing

To validate the WES results, the identified candidate variants were amplified by PCR using genomic DNA from the patients and their parents. The primers used for PCR are listed in Supplementary Table S2. The PCR products were purified and sequenced in two orientations using an ABI 3500 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The mutation sites were analyzed by comparison with the GenBank reference sequences of each candidate gene.

Exome-Based CNV Detection and Validation

A comprehensive tool was used for CNV calling. It included XHMM (http://atgu.mgh.harvard.edu/xhmm) and PCA method to remove sequencing noise and CNVKit (https://github.com/etal/cnvkit) fix module to perform GC and bias correction; and then copy number calculation and CNV identification were performed in exons and long segment areas. The identified CNVs were interpreted according to the standards and guidelines for interpretation and reporting of postnatal constitutional CNVs released by the ACMG and the technical standards for the interpretation and reporting of constitutional copy-number variants recommended by the ACMG and the Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen) (Kearney et al., 2011; Riggs et al., 2020). CNVs were further validated by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) or quantitative PCR (qPCR) or CNV sequencing (CNV-seq).

Results

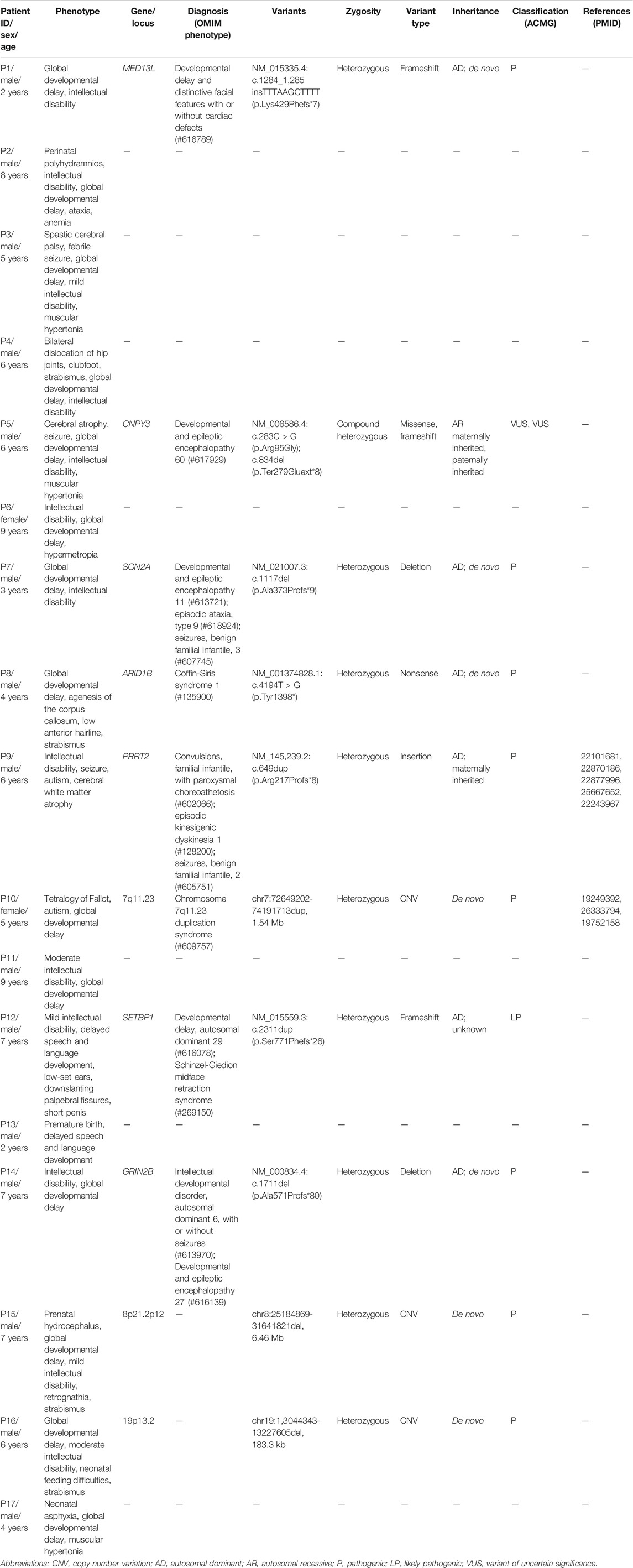

A total of 17 children with DD/ID were enrolled and analyzed by WES. As shown in Table 1, the age of 17 probands in this study ranged from 2 to 9 years, with a mean age of 5.6 years. Male-to-female ratio was 15:2. The clinical characteristics of 17 probands include global DD (14/17) and ID (13/17) (Table 1, Supplementary Table S1).

Diagnostic Yields

Among the 17 probands, WES in family trios (Trio-WES) was performed for 14 patients (patients 1–11 and 15–17). Patient 12 and his father underwent WES as a father–proband duo, for the sample of the patient’s mother was unavailable. And patients 13 and 14 had singleton WES. Analysis of WES data revealed that the coverage for over 97% of the targeted bases were over 20×, with an average sequencing depth of over 100×. An overall diagnostic rate of 58.8% (10/17) was achieved after analysis of SNV/Indel and CNV, of which diagnostic SNVs/Indels accounted for 41.2% (7/17) and diagnostic CNVs accounted for 17.6% (3/17) (Table 1).

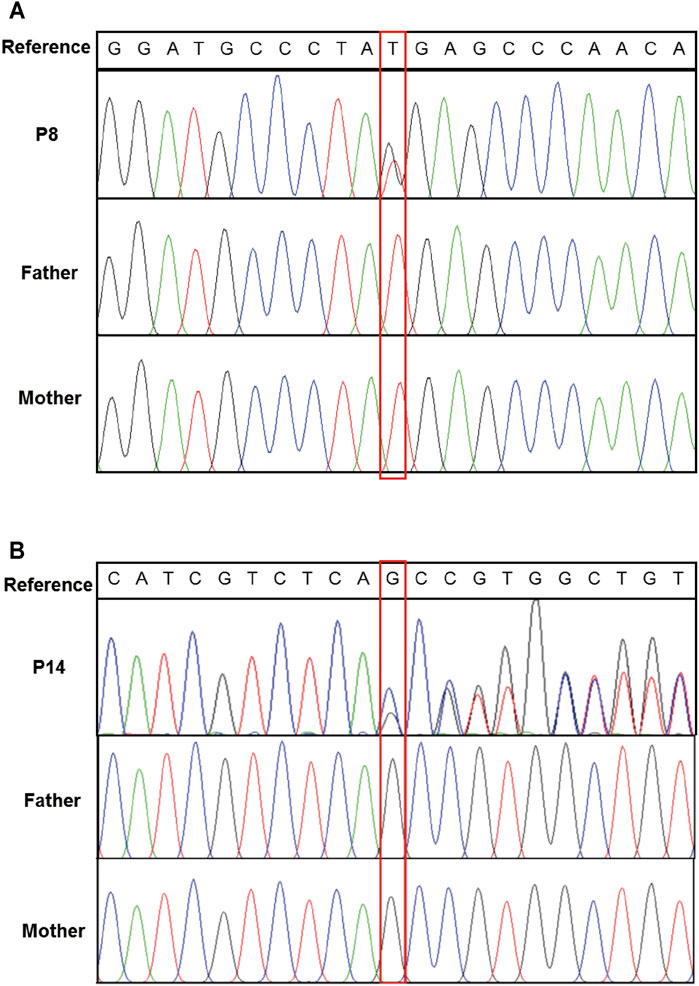

A total of eight variants in seven genes were identified in seven probands by SNV/Indel analysis and confirmed by Sanger sequencing, including six variants in six genes associated with autosomal dominant disorders and two compound heterozygous variants in CNPY3 gene related to an autosomal recessive disorder early infantile epileptic encephalopathy 60 (EIEE60). In autosomal dominant disorders, four variants detected in patients 1, 7, 8, and 14 occurred de novo (Figure 1); the origin of a variant in SETBP1 gene of patient 12 is unknown, for his mother’s sample is unavailable; and a variant in PRRT2 gene of patient 9 was inherited from his unaffected mother. The two compound heterozygous variants in CNPY3 gene of patient 5 were inherited from his mother and father (Table 1).

FIGURE 1. Confirmation of de novo variants by Sanger sequencing. (A) Sanger sequencing of ARID1B in patient 8 and his parents. (B) Sanger sequencing of GRIN2B in patient 14 and his parents. Variants were indicated by red boxes.

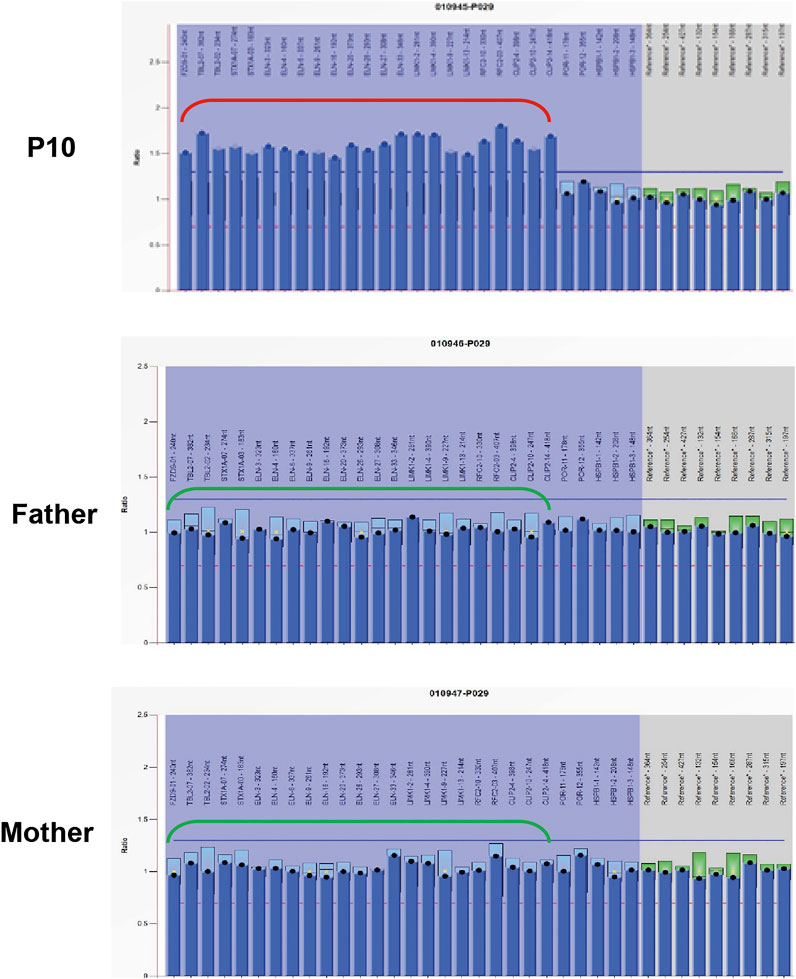

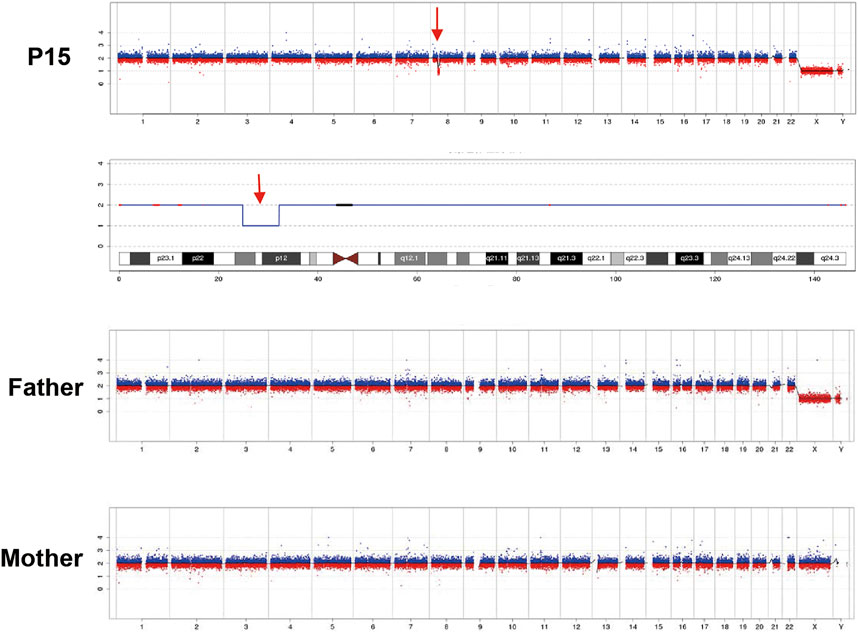

Exome-based CNV analysis revealed three de novo pathogenic CNVs. A 1.54-Mb duplication on chromosome 7q11.23 related to chromosome 7q11.23 duplication syndrome (MIM #609757) was identified in patient 10 and confirmed by MLPA (Figure 2). In patient 15, a 6.46-Mb deletion on chromosome 8p21.2p12 was detected and validated by CNV-seq (Figure 3). A 183.3-kb deletion on chromosome 19p13.2 was found in patient 16 and verified by qPCR (Figure 4).

FIGURE 2. MLPA results of patient 10 and her parents. MLPA was performed using SALSA MLPA Probemix P029 WBS kit, and the red bracket indicates the duplication region in patient 10.

FIGURE 3. CNV-seq results of patient 15 and his parents. A 6.46-Mb deletion on chromosome 8 of patient 15 is indicated by the red arrow.

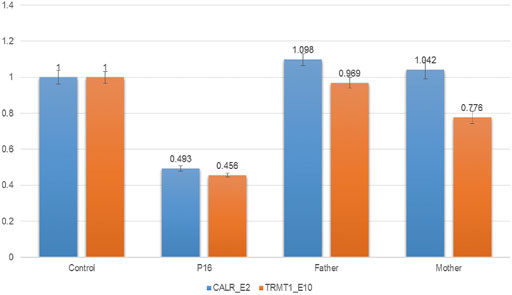

FIGURE 4. qPCR results of patient 16 and his parents. To confirm the 183.3-kb deletion on chromosome 19p13.2, two pairs of primers for CALR_E2 and TRMT1_E10 were selected and used in the qPCR. Three replicates were performed, and the relative copy number was estimated by the comparative 2−ΔΔCT method using ALB gene as the internal control. The numbers in the Y-axis indicate the 2−ΔΔCT value. 2−ΔΔCT < 0.1 is considered to be a homozygous deletion, 0.3 < 2−ΔΔCT < 0.7 is considered to be a heterozygous deletion, 0.7 < 2−ΔΔCT < 1.3 is considered to be normal, and 2−ΔΔCT > 1.3 is considered to be a duplication.

Case Example

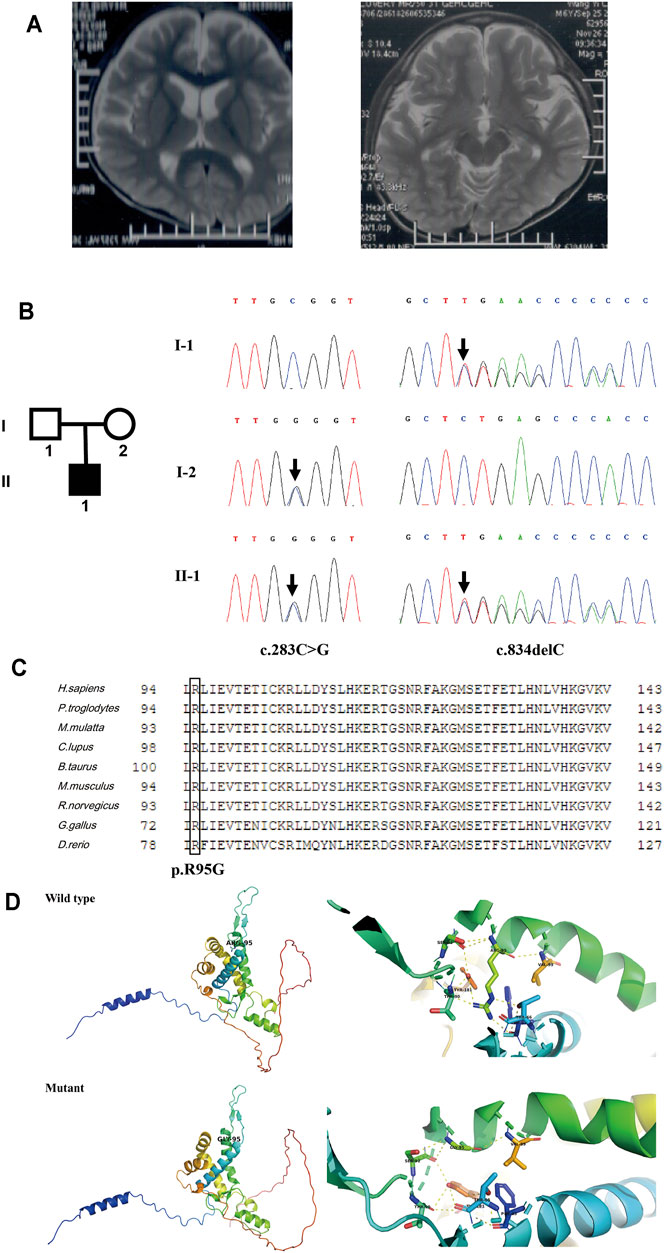

Patient 5 is a 6-year-old boy whose parents are healthy and non-consanguineous. He was born full term by natural delivery without abnormalities, weighing 2,900 g. He was bed ridden and presented with global DD, spastic quadriplegia, ID, and intractable seizure. He had multiple admissions for pneumonia and seizure. His first seizure started at age 6 months, and his electroencephalography (EEG) at 2 years of age showed diffuse sharp waves, spike waves, and multiple spike and slow wave complex. MRI of his brain at 6 years old revealed enlargement of the lateral ventricles and cerebral atrophy (Figure 5A).

FIGURE 5. Clinical information and genetic analysis of patient 5. (A) Brain MRI of the patient. The left panel shows enlarged lateral ventricles, and the right panel shows bilateral hippocampus. (B) Genetic analysis of the family. Left panel: the pedigree of the patient’s family. Right panel: Sanger sequencing of CNPY3 in family members demonstrated mutations in the proband and his parents. Mutations are indicated by black arrows. (C) Multiple sequence alignment of CNPY3 protein and its orthologs in different species. The arginine residue in position 95 is indicated by a black box. The protein and its orthologs were aligned using Clustal Omega (http://www.clustal.org/omega/). (D) Predicted structures of wild-type and mutated CNPY3 proteins using PyMOL (http://www.pymol.org). ARG-95 of wild-type protein may form hydrogen bonds with PHE-63, THR-66, THR-90, SER-92, VAL-99, and TYR-181, while GLY-95 of mutant protein may only form hydrogen bonds with SER-92 and VAL-99, which may affect the protein structure and function.

WES in family trios (Trio-WES) was performed with DNA from patient 5 and his parents. For patient 5, the coverage for 97.87% of the targeted bases was over 20×. Ultimately, two compound heterozygous variants in CNPY3 gene (c.283C > G and c.834del) were detected. Sanger sequencing validated the two compound heterozygous variants in the patient. His mother was heterozygous for the c.283C > G variant in exon 3 of CNPY3 gene, and his father was heterozygous for the c.834del variant in exon six of CNPY3 gene (Figure 5B). These two variants were not recorded in the dbSNP, 1000 Genomes Project database, ExAC, or gnomAD. The c.283C > G variant was a novel missense mutation causing a substitution from arginine to glycine of CNPY3 protein (p.Arg95Gly), which is predicted to be deleterious by PROVEAN with a score of −6.62, probably damaging by PolyPhen-2 with a score of 1.0, and disease causing by MutationTaster with a probability value of 0.999. Furthermore, sequence alignment of human CNPY3 protein and its othologs in different species revealed that the R95 residue is highly conserved among species (Figure 5C). And protein structural analysis revealed that substitution from arginine to glycine of CNPY3 protein at position 95 may reduce the formation of hydrogen bonds, thus affecting the protein structure and function (Figure 5D). The c.834del variant is a novel frameshift deletion mutation, which results in a prolonged protein with the addition of eight amino acid residues (EPTQHPLS) to the C-terminal of CNPY3 protein (p.Ter279Gluext*8). According to the ACMG variant classification guideline (Richards et al., 2015), the c.283C > G variant could be classified as uncertain significance with two supporting (PM2_Supporting and PP3) evidences, and the c.834del variant could be classified as uncertain significance with one moderate (PM4) and one supporting (PM2_Supporting) evidences.

Discussion

In this study, WES was performed for 17 probands with DD/ID with an overall diagnostic yield of 58.8% (10/17), which is consistent with a recent study that WES identified pathogenic variants in 53.5% (54/101) of patients with DD/ID (Hiraide et al., 2021). A total of eight de novo variants were detected, including five SNVs/Indels and three CNVs, corroborating the burden of de novo variants in DD/ID (Brunet et al., 2021). And further functional studies are needed to elucidate the effect of the identified variants at the transcriptional or translational level. In addition, exome-based CNV analysis revealed three pathogenic CNVs, increasing the diagnostic yield by 17.6% (3/17), which is consistent with a recent study that incorporation of exome-based CNV calling improved the diagnostic rate of trio-WES by 18.92% (14/74) in patients with NDDs (Zhai et al., 2021). However, WES analysis yielded negative results for seven patients in this study, possibly due to technical limitations of WES (e.g., deep intron mutations and structural variants).

SNV/Indel analysis identified eight variants of seven genes, including five novel heterozygous variants in patients 1, 7, 8, 12, and 14; one reported heterozygous variant in patient 9; and two compound heterozygous variants in patient 5. A novel de novo heterozygous variant c.1284_1285insTTTAAGCTTTT of MED13L gene was detected in patient 1, resulting in a frameshift and a premature stop codon (p.Lys429Phefs*7). The mediator complex subunit 13-like (MED13L) gene encodes a subunit of the mediator complex that functions as transcriptional regulation by physically linking DNA-binding transcription factors and RNA polymerase II in early development of the heart and brain (Utami et al., 2014). MED13L haploinsufficiency is involved in DD and distinctive facial features with or without cardiac defects (MIM #616789). In addition to DD/ID, patient 1 had mild dysmorphic facial features, but cardiac malformations were not observed, which is consistent with previous reports on variable penetrance of cardiac malformations (Adegbola et al., 2015; Cafiero et al., 2015).

For patient 7, a novel de novo heterozygous variant c.1117del of SCN2A gene was identified, leading to a frameshift and a premature termination (p.Ala373Profs*9). SCN2A encodes the voltage-gated sodium channel Nav1.2, which plays a role in the initiation and conduction of action potentials (Wolff et al., 2017). Mutations in SCN2A were related to a spectrum of epilepsies and NDDs with phenotypic heterogeneity, including developmental and epileptic encephalopathy 11 (MIM #613721); episodic ataxia type 9 (MIM #618924); and benign familial infantile seizures 3 (MIM #607745). Patient 7 is 3 years old with DD and ID, but he is seizure-free until now. He may have later-onset epilepsy, or he may show ID and/or autism without epilepsy as 16% (32/201) of previously reported cases with SCN2A mutations (Wolff et al., 2017).

WES identified a novel de novo heterozygous nonsense mutation (c.4194T > G, p. Tyr1398*) of ARID1B gene in patient 8. To date, nine genes have been reported to be related to Coffin-Siris syndrome, and mutations of ARID1B gene were the most common reason for Coffin-Siris syndrome. ARID1B encodes a small subset of SWI/SNF (SWItch/Sucrose Non-Fermentable) complexes that play an important role in chromatin remodeling (Sekiguchi et al., 2019). Agenesis of corpus callosum was detected prenatally and confirmed after birth in patient 8, but hypoplasia of the fifth digits/nails was not observed, which is consistent with a previous report that most patients with corpus callosum anomalies and ARID1B mutations (n = 8/11) had normal fingers and toes (Mignot et al., 2016).

For patient 9, a heterozygous variant (c.649dup, p. Arg217Profs*8) of PRRT2 gene was identified, which was inherited from his mother. PRRT2 encodes the proline-rich transmembrane protein 2 (PRRT2) and is highly expressed in the brain and spinal cord (Chen et al., 2011). PRRT2 is associated with familial infantile convulsions with paroxysmal choreoathetosis (MIM #602066), episodic kinesigenic dyskinesia 1 (MIM #128200), and benign familial infantile seizures 2 (MIM #605751); and the penetrance of episodic kinesigenic dyskinesia 1 is estimated to be 60%–90% (van Vliet et al., 2012). The c.649dup variant was a mutation hotspot in families of different origins (Wang et al., 2011; Ono et al., 2012; Schubert et al., 2012), and a homozygous c.649dup mutation was detected in five individuals of an Iranian family with severe non-syndromic ID (Najmabadi et al., 2011). However, it was reported that only 0.6% (8/1,423) of individuals with heterozygous PRRT2 mutations present ID (Ebrahimi-Fakhari et al., 2015), and PRRT2 mutations are not related to increased susceptibility to ASD (Huguet et al., 2014), suggesting that the maternally inherited c.649dup variant of PRRT2 may not completely explain the phenotypes of ID and autism observed in patient 9.

A novel heterozygous variant c.2311dup of SETBP1 gene was detected in patient 12, resulting in a frameshift and a premature termination (p.Ser771Phefs*26). SETBP1 encodes the SET binding protein 1 expressed ubiquitously, but little is known about the function of SETBP1 (Hoischen et al., 2010). De novo gain-of-function variants of SETBP1 are associated with Schinzel-Giedion midface retraction syndrome (MIM #269150), while haploinsufficiency of SETBP1 caused by loss-of-function (LoF) variant or a heterozygous gene deletion is related to DD, autosomal dominant 29 (MIM #616078). Patient 12 exhibited mild ID (IQ 65–70), consistent with a recent study that ID of various levels was observed in 77% (23/30) of patients with SETBP1 haploinsufficiency disorder (Jansen et al., 2021). In addition, another study indicated that aberrant speech and language development are central to SETBP1 haploinsufficiency disorder (Morgan et al., 2021), and patient 12 also showed impaired speech and language development.

For patient 14, a novel heterozygous variant c.1711del of GRIN2B gene was identified, leading to a frameshift and a premature stop codon (p.Ala571Profs*80). GRIN2B encodes the subunit NR2B of N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, which are neurotransmitter-gated ion channels involved in the regulation of synaptic function in the central nervous system (Endele et al., 2010). GRIN2B is related to intellectual developmental disorder, autosomal dominant 6, with or without seizures (MIM #613970), and developmental and epileptic encephalopathy 27 (MIM #616139). A previous study of 58 individuals with GRIN2B encephalopathy revealed that 52% (30/58) of the patients have had seizures with a variable age of onset (0–9 years) (Platzer et al., 2017). Patient 14 is 7 years old, and he is seizure-free until now.

EIEE is a group of neurological disorders characterized by frequent epileptic seizures and development delay beginning in infancy (McTague et al., 2016). In 2018, biallelic variants in CNPY3 gene (MIM *610774) have been identified to cause EIEE60 (MIM #617929) (Mutoh et al., 2018). CNPY3 gene is located on chromosome 6p21.1, comprises six exons and five introns, and encodes a co-chaperone of 278 amino acid residues in the endoplasmic reticulum. In this study, two compound heterozygous variants of CNPY3 gene were identified in patient 5. To date, three individuals with biallelic CNPY3 variants have been reported, and their MRI showed diffuse brain atrophy and hippocampal malrotation (Mutoh et al., 2018). Brain MRI of patient 5 also showed cerebral atrophy, but hippocampal malrotation was not observed. And the other phenotypes of patient 5 were consistent with the three reported patients in the literature.

Three pathogenic CNVs were detected by exome-based CNV analysis in patients 10, 15, and 16. A 1.54-Mb heterozygous duplication on chromosome 7q11.23 was identified in patient 10; hence, he was diagnosed with chromosome 7q11.23 duplication syndrome (MIM #609757). 7q11.23 duplication syndrome is characterized by DD, speech delay, and congenital anomalies (Morris et al., 2015). To date, more than 150 individuals with 7q11.23 duplication syndrome have been reported (Mervis et al., 2015). Patient 10 was diagnosed with tetralogy of Fallot after birth and underwent surgical repair. And he showed delayed motor, speech, and autistic features at 3 years old, which are similar to the characteristics of 7q11.23 duplication patients reported in the literature.

For patient 15, a 6.46-Mb heterozygous deletion on chromosome 8p21.2p12 was detected, which overlaps with the deletion region of four cases recorded in the DECIPHER database (https://www.deciphergenomics.org). DECIPHER patient #390234 had attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, depressivity, expressive language delay, and mild ID. Patient #1557 had abnormality of the skin, blepharophimosis, fine hair, hearing impairment, hypothyroidism, ID, microtia, obesity, and short palm. Patient #415150 had mild ID, seizure. And patient #372147 had delayed speech and language development, generalized hypotonia, hypermetropia, short stature, and strabismus. A previous study reviewed 21 patients with deletions overlapping 8p21p12 region; and growth retardation, psychomotor retardation, and postnatal microcephaly were characteristics of most patients (Willemsen et al., 2009). Patient 15 also showed mild ID and DD, and he had hydrocephalus diagnosed prenatally, which was not reported in patients with deletion on 8p21.2p12. He underwent neurosurgical cerebrospinal fluid diversion after birth; afterwards, his follow-up CT scan was normal.

A 183.3-kb deletion on chromosome 19p13.2 encompassing NFIX gene was identified in patient 16. Haploinsufficiency of NFIX causes Sotos syndrome 2 (MIM #614753), which is characterized by postnatal overgrowth, macrocephaly, DD, and intellectual impairment (Malan et al., 2010). Patients with Sotos syndrome 2 will develop marfanoid habitus with age. The birth weight of patient 16 is 3.45 kg, and he had neonatal feeding difficulties. Now he is 6 years old with a weight of 21 kg (normal range) and height of 128 cm (+2 SD), consistent with a previous report that the median height of patients with Sotos syndrome 2 is 2.0 SD above the mean (range −0.5 to +3.8 SD) (Klaassens et al., 2015). He also had strabismus, DD, and moderate ID, similar to reported patients with 19p13.2 deletion encompassing NFIX gene (Klaassens et al., 2015; Jezela-Stanek et al., 2016).

In conclusion, WES could identify the underlying genetic causes for patients with unexplained DD/ID, and exome-based CNV analysis could detect clinically significant submicroscopic CNVs, thus improving the diagnostic yield. Our findings not only broaden the known mutation spectrum of genes associated with DD/ID but also indicate the potential of WES and exome-based CNV analysis in clinical diagnosis and discovery of disease-causing mutations and CNVs.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available due to ethical concerns regarding patient privacy and consent. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the institutional ethics committee of the Affiliated Suzhou Hospital of Nanjing Medical University. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s), and minors’ legal guardian/next of kin, for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

JX, QZ, and TW are responsible for testing strategy design and manuscript preparation. Data analysis and interpretation were performed by JX, HT, JM, and QH. Genetic counselling was conducted by QZ, YD, FY, AG, and WZ. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by Jiangsu Provincial Medical Innovation Team (CXTDB2017013), Suzhou Clinical Medical Expert Team (SZYJTD201708), Jiangsu Science and Technology Support Program (BE2019683), and Suzhou Science and Technology Support Program (SS2019066).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the patients for participating in this research project. We also acknowledge all members of our center.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgene.2021.738561/full#supplementary-material

References

Adegbola, A., Musante, L., Callewaert, B., Maciel, P., Hu, H., Isidor, B., et al. (2015). Redefining the MED13L Syndrome. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 23 (10), 1308–1317. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2015.26

Brunet, T., Jech, R., Brugger, M., Kovacs, R., Alhaddad, B., Leszinski, G., et al. (2021). De Novo variants in Neurodevelopmental Disorders-Experiences from a Tertiary Care center. Clin. Genet. doi:10.1111/cge.13946

Cafiero, C., Marangi, G., Orteschi, D., Ali, M., Asaro, A., Ponzi, E., et al. (2015). Novel De Novo Heterozygous Loss-Of-Function Variants in MED13L and Further Delineation of the MED13L Haploinsufficiency Syndrome. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 23 (11), 1499–1504. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2015.19

Chen, W.-J., Lin, Y., Xiong, Z.-Q., Wei, W., Ni, W., Tan, G.-H., et al. (2011). Exome Sequencing Identifies Truncating Mutations in PRRT2 that Cause Paroxysmal Kinesigenic Dyskinesia. Nat. Genet. 43 (12), 1252–1255. doi:10.1038/ng.1008

Ebrahimi-Fakhari, D., Saffari, A., Westenberger, A., and Klein, C. (2015). The Evolving Spectrum ofPRRT2-Associated Paroxysmal Diseases. Brain 138 (Pt 12), 3476–3495. doi:10.1093/brain/awv317

Endele, S., Rosenberger, G., Geider, K., Popp, B., Tamer, C., Stefanova, I., et al. (2010). Mutations in GRIN2A and GRIN2B Encoding Regulatory Subunits of NMDA Receptors Cause Variable Neurodevelopmental Phenotypes. Nat. Genet. 42 (11), 1021–1026. doi:10.1038/ng.677

Hiraide, T., Yamoto, K., Masunaga, Y., Asahina, M., Endoh, Y., Ohkubo, Y., et al. (2021). Genetic and Phenotypic Analysis of 101 Patients with Developmental Delay or Intellectual Disability Using Whole‐exome Sequencing. Clin. Genet. 100, 40–50. doi:10.1111/cge.13951

Hoischen, A., van Bon, B. W. M., Gilissen, C., Arts, P., van Lier, B., Steehouwer, M., et al. (2010). De Novo mutations of SETBP1 Cause Schinzel-Giedion Syndrome. Nat. Genet. 42 (6), 483–485. doi:10.1038/ng.581

Huguet, G., Nava, C., Lemière, N., Patin, E., Laval, G., Ey, E., et al. (2014). Heterogeneous Pattern of Selective Pressure for PRRT2 in Human Populations, but No Association with Autism Spectrum Disorders. PLoS One 9 (3), e88600. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0088600

Ismail, F. Y., and Shapiro, B. K. (2019). What Are Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 32 (4), 611–616. doi:10.1097/WCO.0000000000000710

Jansen, N. A., Braden, R. O., Srivastava, S., Otness, E. F., Lesca, G., Rossi, M., et al. (2021). Clinical Delineation of SETBP1 Haploinsufficiency Disorder. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 29, 1198–1205. doi:10.1038/s41431-021-00888-9

Jezela-Stanek, A., Kucharczyk, M., Falana, K., Jurkiewicz, D., Mlynek, M., Wicher, D., et al. (2016). Malan Syndrome (Sotos Syndrome 2) in Two Patients with 19p13.2 Deletion Encompassing NFIX Gene and Novel NFIX Sequence Variant. Biomed. Pap. 160 (1), 161–167. doi:10.5507/bp.2016.006

Kearney, H. M., Thorland, E. C., Brown, K. K., Quintero-Rivera, F., and South, S. T. (2011). Working Group of the American College of Medical Genetics Laboratory Quality Assurance, C. (American College of Medical Genetics Standards and Guidelines for Interpretation and Reporting of Postnatal Constitutional Copy Number Variants. Genet. Med. 13 (7), 680–685. doi:10.1097/GIM.0b013e3182217a3a

Klaassens, M., Morrogh, D., Rosser, E. M., Jaffer, F., Vreeburg, M., Bok, L. A., et al. (2015). Malan Syndrome: Sotos-like Overgrowth with De Novo NFIX Sequence Variants and Deletions in Six New Patients and a Review of the Literature. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 23 (5), 610–615. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2014.162

Malan, V., Rajan, D., Thomas, S., Shaw, A. C., Louis Dit Picard, H., Layet, V., et al. (2010). Distinct Effects of Allelic NFIX Mutations on Nonsense-Mediated mRNA Decay Engender Either a Sotos-like or a Marshall-Smith Syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 87 (2), 189–198. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.07.001

Manning, M., Hudgins, L., Professional, P., and Guidelines, C. (2010). Array-based Technology and Recommendations for Utilization in Medical Genetics Practice for Detection of Chromosomal Abnormalities. Genet. Med. 12 (11), 742–745. doi:10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181f8baad

Marchuk, D. S., Crooks, K., Strande, N., Kaiser-Rogers, K., Milko, L. V., Brandt, A., et al. (2018). Increasing the Diagnostic Yield of Exome Sequencing by Copy Number Variant Analysis. PLoS One 13 (12), e0209185. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0209185

McTague, A., Howell, K. B., Cross, J. H., Kurian, M. A., and Scheffer, I. E. (2016). The Genetic Landscape of the Epileptic Encephalopathies of Infancy and Childhood. Lancet Neurol. 15 (3), 304–316. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00250-1

Mervis, C. B., Morris, C. A., Klein-Tasman, B. P., Velleman, S. L., and Osborne, L. R. (2015). “7q11.23 Duplication Syndrome,” in GeneReviews®. Editors M. P. Adam, H. H. Ardinger, R. A. Pagon, S. E. Wallace, L. J. H. Bean, G. Mirzaaet al. (Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Seattle), 1993–2021. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK327268/

Mignot, C., Moutard, M.-L., Rastetter, A., Boutaud, L., Heide, S., Billette, T., et al. (2016). ARID1Bmutations Are the Major Genetic Cause of Corpus Callosum Anomalies in Patients with Intellectual Disability. Brain 139 (11), e64. doi:10.1093/brain/aww181

Miller, D. T., Adam, M. P., Aradhya, S., Biesecker, L. G., Brothman, A. R., Carter, N. P., et al. (2010). Consensus Statement: Chromosomal Microarray Is a First-Tier Clinical Diagnostic Test for Individuals with Developmental Disabilities or Congenital Anomalies. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 86 (5), 749–764. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.04.006

Mithyantha, R., Kneen, R., McCann, E., and Gladstone, M. (2017). Current Evidence-Based Recommendations on Investigating Children with Global Developmental Delay. Arch. Dis. Child. 102 (11), 1071–1076. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2016-311271

Monroe, G. R., Frederix, G. W., Savelberg, S. M. C., de Vries, T. I., Duran, K. J., van der Smagt, J. J., et al. (2016). Effectiveness of Whole-Exome Sequencing and Costs of the Traditional Diagnostic Trajectory in Children with Intellectual Disability. Genet. Med. 18 (9), 949–956. doi:10.1038/gim.2015.200

Morgan, A., Braden, R., Wong, M. M. K., Colin, E., Amor, D., Liégeois, F., et al. (2021). Speech and Language Deficits Are central to SETBP1 Haploinsufficiency Disorder. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 29, 1216–1225. doi:10.1038/s41431-021-00894-x

Morris, C. A., Mervis, C. B., Paciorkowski, A. P., Abdul-Rahman, O., Dugan, S. L., Rope, A. F., et al. (2015). 7q11.23 Duplication Syndrome: Physical Characteristics and Natural History. Am. J. Med. Genet. 167 (12), 2916–2935. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.37340

Mutoh, H., Kato, M., Akita, T., Shibata, T., Wakamoto, H., Ikeda, H., et al. (2018). Biallelic Variants in CNPY3, Encoding an Endoplasmic Reticulum Chaperone, Cause Early-Onset Epileptic Encephalopathy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 102 (2), 321–329. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.01.004

Najmabadi, H., Hu, H., Garshasbi, M., Zemojtel, T., Abedini, S. S., Chen, W., et al. (2011). Deep Sequencing Reveals 50 Novel Genes for Recessive Cognitive Disorders. Nature 478 (7367), 57–63. doi:10.1038/nature10423

Ono, S., Yoshiura, K.-i., Kinoshita, A., Kikuchi, T., Nakane, Y., Kato, N., et al. (2012). Mutations in PRRT2 Responsible for Paroxysmal Kinesigenic Dyskinesias Also Cause Benign Familial Infantile Convulsions. J. Hum. Genet. 57 (5), 338–341. doi:10.1038/jhg.2012.23

Platzer, K., Yuan, H., Schütz, H., Winschel, A., Chen, W., Hu, C., et al. (2017). GRIN2B Encephalopathy: Novel Findings on Phenotype, Variant Clustering, Functional Consequences and Treatment Aspects. J. Med. Genet. 54 (7), 460–470. doi:10.1136/jmedgenet-2016-104509

Richards, S., Aziz, N., Aziz, N., Bale, S., Bick, D., Das, S., et al. (2015). Standards and Guidelines for the Interpretation of Sequence Variants: a Joint Consensus Recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 17 (5), 405–423. doi:10.1038/gim.2015.30

Riggs, E. R., Andersen, E. F., Cherry, A. M., Kantarci, S., Kearney, H., Patel, A., et al. (2020). Technical Standards for the Interpretation and Reporting of Constitutional Copy-Number Variants: a Joint Consensus Recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) and the Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen). Genet. Med. 22 (2), 245–257. doi:10.1038/s41436-019-0686-8

Savatt, J. M., and Myers, S. M. (2021). Genetic Testing in Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Front. Pediatr. 9, 526779. doi:10.3389/fped.2021.526779

Schubert, J., Paravidino, R., Becker, F., Berger, A., Bebek, N., Bianchi, A., et al. (2012). PRRT2 Mutations Are the Major Cause of Benign Familial Infantile Seizures. Hum. Mutat. 33 (10), 1439–1443. doi:10.1002/humu.22126

Sekiguchi, F., Tsurusaki, Y., Okamoto, N., Teik, K. W., Mizuno, S., Suzumura, H., et al. (2019). Genetic Abnormalities in a Large Cohort of Coffin-Siris Syndrome Patients. J. Hum. Genet. 64 (12), 1173–1186. doi:10.1038/s10038-019-0667-4

Srivastava, S., Love-Nichols, J. A., Love-Nichols, J. A., Dies, K. A., Ledbetter, D. H., Martin, C. L., et al. (2019). Meta-analysis and Multidisciplinary Consensus Statement: Exome Sequencing Is a First-Tier Clinical Diagnostic Test for Individuals with Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Genet. Med. 21 (11), 2413–2421. doi:10.1038/s41436-019-0554-6

Thapar, A., Cooper, M., and Rutter, M. (2017). Neurodevelopmental Disorders. The Lancet Psychiatry 4 (4), 339–346. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30376-5

Utami, K. H., Winata, C. L., Hillmer, A. M., Aksoy, I., Long, H. T., Liany, H., et al. (2014). Impaired Development of Neural-Crest Cell Derived Organs and Intellectual Disability Caused ByMED13LHaploinsufficiency. Hum. Mutat. 35 (11), a–n. doi:10.1002/humu.22636

van Vliet, R., Breedveld, G., de Rijk-van Andel, J., Brilstra, E., Verbeek, N., Verschuuren-Bemelmans, C., et al. (2012). PRRT2 Phenotypes and Penetrance of Paroxysmal Kinesigenic Dyskinesia and Infantile Convulsions. Neurology 79 (8), 777–784. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182661fe3

Vissers, L. E. L. M., Gilissen, C., and Veltman, J. A. (2016). Genetic Studies in Intellectual Disability and Related Disorders. Nat. Rev. Genet. 17 (1), 9–18. doi:10.1038/nrg3999

Wang, J.-L., Cao, L., Li, X.-H., Hu, Z.-M., Li, J.-D., Zhang, J.-G., et al. (2011). Identification of PRRT2 as the Causative Gene of Paroxysmal Kinesigenic Dyskinesias. Brain 134 (Pt 12), 3493–3501. doi:10.1093/brain/awr289

Wang, K., Li, M., and Hakonarson, H. (2010). ANNOVAR: Functional Annotation of Genetic Variants from High-Throughput Sequencing Data. Nucleic Acids Res. 38 (16), e164. doi:10.1093/nar/gkq603

Willemsen, M. H., de Leeuw, N., Pfundt, R., de Vries, B. B. A., and Kleefstra, T. (2009). Clinical and Molecular Characterization of Two Patients with a 6.75Mb Overlapping Deletion in 8p12p21 with Two Candidate Loci for Congenital Heart Defects. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 52 (2-3), 134–139. doi:10.1016/j.ejmg.2009.03.003

Wolff, M., Johannesen, K. M., Hedrich, U. B. S., Masnada, S., Rubboli, G., Gardella, E., et al. (2017). Genetic and Phenotypic Heterogeneity Suggest Therapeutic Implications in SCN2A-Related Disorders. Brain 140 (5), 1316–1336. doi:10.1093/brain/awx054

Keywords: whole-exome sequencing, developmental delay, intellectual disability, exome-based CNV analysis, variants

Citation: Xiang J, Ding Y, Yang F, Gao A, Zhang W, Tang H, Mao J, He Q, Zhang Q and Wang T (2021) Genetic Analysis of Children With Unexplained Developmental Delay and/or Intellectual Disability by Whole-Exome Sequencing. Front. Genet. 12:738561. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2021.738561

Received: 09 July 2021; Accepted: 07 October 2021;

Published: 10 November 2021.

Edited by:

Anjana Munshi, Central University of Punjab, IndiaReviewed by:

Theresa V. Strong, Foundation for Prader-Willi Research, United StatesSantasree Banerjee, Beijing Genomics Institute, China

Copyright © 2021 Xiang, Ding, Yang, Gao, Zhang, Tang, Mao, He, Zhang and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ting Wang, Ymlvd3RAbmptdS5lZHUuY24=; Qin Zhang, emhhbmdxMTEwMDA0QDE2My5jb20=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Jingjing Xiang

Jingjing Xiang Yang Ding1,2†

Yang Ding1,2† Quanze He

Quanze He Qin Zhang

Qin Zhang Ting Wang

Ting Wang