- 1School of Life Sciences, Anhui Agricultural University, Hefei, China

- 2Institute of Sericulture, Anhui Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Hefei, China

TCP is a plant-specific transcription factor that plays an important role in flowering, leaf development and other physiological processes. In this study, we identified a total of 155 TCP genes: 34 in Pyrus bretschneideri, 19 in Fragaria vesca, 52 in Malus domestica, 19 in Prunus mume, 17 in Rubus occidentalis and 14 in Prunus avium. The evolutionary relationship of the TCP gene family was examined by constructing a phylogenetic tree, tracking gene duplication events, performing a sliding window analysis. The expression profile analysis and qRT-PCR results of different tissues showed that PbTCP10 were highly expressed in the flowers. These results indicated that PbTCP10 might participated in flowering induction in pear. Expression pattern analysis of different developmental stages showed that PbTCP14 and PbTCP15 were similar to the accumulation pattern of fruit lignin and the stone cell content. These two genes might participate in the thickening of the secondary wall during the formation of stone cells in pear. Subcellular localization showed that PbTCPs worked in the nucleus. This study explored the evolution of TCP genes in six Rosaceae species, and the expression pattern of TCP genes in different tissues of “Dangshan Su” pear. Candidate genes related to flower induction and stone cell formation were identified. In summary, our research provided an important theoretical basis for improving pear fruit quality and increasing fruit yield by molecular breeding.

Introduction

TCP (TEOSINTE BRANCHED I, CYCLOIDEA, PROLIFERATING CELL FACTOR I) transcription factors are unique to plants and play an important role in all aspects of plant growth and development (Uberti-Manassero et al., 2016; Lucero et al., 2017). The amino acid sequences encoded by members of the TCP family generally have a basic helix loop helix structure. The second helical region has a specific LXXLL motif, which can interact with DNA or protein. Based on their structures, the TCP family can be divided into two subfamilies. Class I, the TCP-P subfamily, is also called PCF subfamily. Class II, the TCP-C subfamily, includes CYC/TB1, and CIN. The most significant difference between the two subfamilies is that PCF subfamily lacks four amino acids in the basic region, and the members of CYC/TB1 subfamily specifically contain a hydrophilic α helix (R domain) rich in polar amino acids which does not exist in other members (Cubas et al., 1999).

The TCP gene was first identified in maize (Zea mays) (teosinte branched 1, TB1), snapdragon (Antirrhinum majus) (cycloidea, CYC) and rice (Oryza sativa) (proliferating cell factors 1 and 2, PCF1/PCF2) (Luo et al., 1996; Doebley et al., 1997; Kosugi and Ohashi, 1997; Cubas et al., 1999). Class I transcription factors can promote cell differentiation and plant growth (Aguilar-Martinez and Sinha, 2013). For example, TCP14 and TCP15 can regulate Arabidopsis seed germination by activating the gibberellin-dependent cell cycle (Resentini et al., 2015). At the same time, it has been reported that TCP14 and TCP15 regulate cell proliferation in leaves and flowers, thus affecting the length between nodes and leaf traits (Kieffer et al., 2011). Overexpression of TCP16 can regulate the process of plant differentiation, resulting in the formation of ectopic meristems (Uberti-Manassero et al., 2016). Class II, compared with Class I, mainly inhibit cell differentiation and plant growth (Manassero et al., 2013; Huang and Irish, 2015). The CYC gene affects the symmetry of flowers in many plants, such as Antirrhinum majus (Luo et al., 1996, 1999), Lotus corniculatus (Feng et al., 2006), and Gerbera happipot (Broholm et al., 2008). It inhibits the formation of floral organs by inhibiting the differentiation of cells, and ultimately affects floral symmetry. The transcription factors of the CIN subfamily can regulate the development of plant leaves. Compared with the wild type, the leaf area of snapdragon mutant (cin) and Arabidopsis mutant (cin) increased, and the leaves were curled and wrinkled (Nath et al., 2003; Palatnik et al., 2003). There were many leaflets on the compound leaves of the tomato mutant (cin), and the excessive growth of the leaf edge caused bending deformation (Ori et al., 2007). The TCP gene of maize (TB1) and Arabidopsis (BRC1) can inhibit the growth of axillary buds and reduce the number of branches above ground (Hubbard et al., 2002; Aguilar-Martinez and Sinha, 2013).

Flowering is an important life activity in plants and is a key step in the transformation from vegetative growth to reproductive growth. The TCP transcription factor plays an important role in flower induction (Zhao et al., 2018; Li et al., 2019). Previous studies found that TCP15 can regulate flowering by binding to the promoter of SUPPRESSOR OF OVEREXPRESSION OF CONSTANS 1 (SOC1) (Lucero et al., 2017). In contrast to TCP15, TCP20, and TCP22 delay flowering by CIRCADIAN CLOCK ASSOCIATED 1 (CCA1) (Wu et al., 2016). CIN-TCP subfamily, represented by TCP4, can interact with FLOWERING BHLH (FBH) and its co-promoter to regulate the flowering process (Liu et al., 2017). TCP5 can regulate petal growth by ethylene (Van Es et al., 2018). In conclusion, two subfamily members of the TCP are involved in regulating flower growth and development (Li et al., 2019). Among the Rosaceae species, fruit trees make up for the majority. Flowering is the starting point of the reproductive stage of fruit trees. The quantity and quality of flowering is an important factor directly affecting the yield of fruit.

With a long history of cultivation, “Dangshan Su” pear (Pyrus bretschneideri cv. Dangshan Su) is one of the most important pear resources in China and occupies an important position in the fruit market (Su et al. 2019). The stone cell content and the size in pear are important factors affecting the quality of fruit (Zhang et al., 2017). Thickening of the secondary wall is an important step in the formation of stone cells (Cheng et al., 2019). Therefore, the thickening of the secondary wall and the deposition of lignin have a great influence on the quality of pear. In the previous study, TCP4 can activate the promoter of VND7 to increase the formation of the secondary wall and up-regulate genes related to lignin and cellulose synthesis (Nag et al., 2009). TCP24 negatively regulates the secondary wall thickness of anther endothecium, resulting in anther dehiscence and pollen release and eventually male sterility (Wang et al., 2015). GbTCP5 is involved in the formation of secondary wall (Wang et al., 2020). Up-regulation of GhTCP4 expression in cotton can activate the synthesis of secondary walls in fibrocyte, thus obtaining fiber with thicker cell walls (Cao et al., 2020). In conclusion, we speculate that the TCP family members may be involved in flower induction and stone cell formation during fruit development of “Dangshan Su” pear. Systematic study of the TCP family is of great importance for improving pear fruit quality.

Although the identification and functions of TCP genes have been studied in Arabidopsis, snapdragon, the TCP genes in pear remain unstudied. In this study, 155 TCP genes were identified in pear (Pyrus bretschneideri), strawberry (Fragaria vesca), plum (Prunus mume), raspberry (Rubus occidentalis), cherry (Prunus avium), apple (Malus domestica). The phylogenetic relationships of TCP genes in six Rosaceae species were elucidated by constructing phylogenetic tree, tracking gene duplication events, performing a sliding window analysis. Candidate genes related to flowering regulation (PbTCP10) were identified by qRT-PCR and expression profile analysis. In addition, based on the analysis of expression patterns in pear and bioinformatics analysis results, we predicted that PbTCP14 and PbTCP15 were the key factors of pear fruit stone cell development. This study provided important theoretical basis and gene resources for improving pear fruit quality.

Materials and Methods

Identification of TCP Genes in Rosaceae

In this study, the Pyrus bretschneideri genome was downloaded from GIGADB datasets1. In addition, Rosaceae genomes (Fragaria vesca, Rubus occidentalis, Prunus avium, Malus domestica, Prunus mume) were obtained from the following website (see text footnote 1)2. Bioedit software was used to construct the local protein database. The conserved domain of TCP was used as the query sequence for Blastp search (E = 0.001) from the local protein database (Supplementary Table 1). The SMART online software was used to search and analyze TCP conserved region (Letunic et al., 2012). ExPASY online website was used to predict the molecular weight and basic information of TCP genes (Artimo et al., 2012). Wolf PSORT was used to the predicted subcellular localization of all TCP genes3 (Horton et al., 2007). Blast2GO sofware was used to implement Gene Ontology (GO) annotation analysis. Visualization of GO classifcations was used the WEGO online tool (Ye et al., 2006). The data of different tissues of Chinese white pear were downloaded from NCBI under the following accession numbers SRR8119889, SRR8119890, SRR8119891, SRR8119892, SRR8119893, SRR8119894, SRR8119895, SRR8119896, SRR8119897, SRR8119898, SRR8119899, SRR8119900, and SRR8119901 (Cao et al., 2019).

Phylogenetic Construction and Conserved Structure Analysis of TCP Genes

All TCP proteins sequenced were analyzed by ClustalW tool in MEGA7.0 software. The phylogenetic tree was constructed by MEGA7.0 software with the Neighbor-Joining method and other default parameters (Kumar et al., 2016). The TCP genes of Arabidopsis were obtained from previous study (Yao et al., 2007). Subsequently, the TCP protein sequence was used to obtain the conserved motif region by MEME online software (Bailey et al., 2015). In the conservative region prediction, we chose the interval range of 6–200, and the number of conservative regions was generally not less than 20.

Chromosomal Localization and Gene Duplication Events

The chromosome information of six Rosaceae species was obtained from the public genomic database, and MapInspect software was used to display the members of TCP gene family on their respective chromosomes (Ma et al., 2015; Zhu et al., 2015). The determination of gene duplication events mainly depended on the following principles: (1) Two genes were located in the same branch of the evolutionary tree, and the similarity of amino acid sequence was more than 80% (2) Two genes were located on the same chromosome and the distance between them was at least 200 kb, we considered these two genes tandem duplicated events (3) Two genes located on different chromosomes were defined as fragment duplication events (4) The non-synonymous substitution (Ka) and synonymous substitution (Ks) values of a replicated gene pair were calculated by DnaSP v5.0 software (Ka/Ks > 1 was positive selection, Ka/Ks < 1 was purification selection, Ka/Ks = 1 was neutral selection). Finally, DnaSP v5.0 software was used to analyze the gene duplication events by sliding window to determine the selection modest each amino acid site (Librado and Rozas, 2009). The specific parameters were as follows: the window size was 150 bp, and each step moved 9 bp.

Chinese White Pear TCP Gene Promoter cis-Acting Element Analysis

We obtained the promoter sequence of TCP genes from the pear genome database. In the database, we found promoter about 1,500–2,000 bp upstream of the initiation codon (ATG) of each TCP genes. The online Plantcare database was used to analyze cis-acting elements4 (Rombauts et al., 1999).

RNA Extraction and qRT-PCR Analysis

The plant material was collected from the “Dangshan Su” pear, which grown in the Dangshan County (Anhui Province, China). The fruits samples were taken on 15, 39, 47, 55, 63, 79, and 102 DAP (days after pollination), as well as the other tissue samples such as flowers, stems, and leaves were also collected on the same year. The 102 DAP fruit was used for expression analysis in different tissues. The buds of “Dangshan Su” pear were treated with gibberellin (GA) (700 mg⋅L–1). Then, the samples of 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 12 HPT (h post-treatment) were collected and stored at −80°C. Finally, the RNA was extracted using a plant RNA extraction kit from Tiangen (Beijing, China). Reverse transcribed by PrimeScriptTM RT reagent kit (Takara, Kusatsu, Japan) and each reaction consisted of 1 μg of RNA. The qRT-PCR primers of TCP genes were designed by Beacon Designer 7 (Supplementary Table 2). The qRT-PCR system consisted of 10 μL SYBR Premix Ex TaqTM II, 2 μL cDNA, 6.4 μL water, and 0.8 μL forward primer and reverse primer. The pear Tubulin gene (AB239680.1) used as an internal reference (Su et al. 2019). Introduction manual used for the procedure and repeat 3 times for each sample. The relative expression levels were calculated using the 2–ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001).

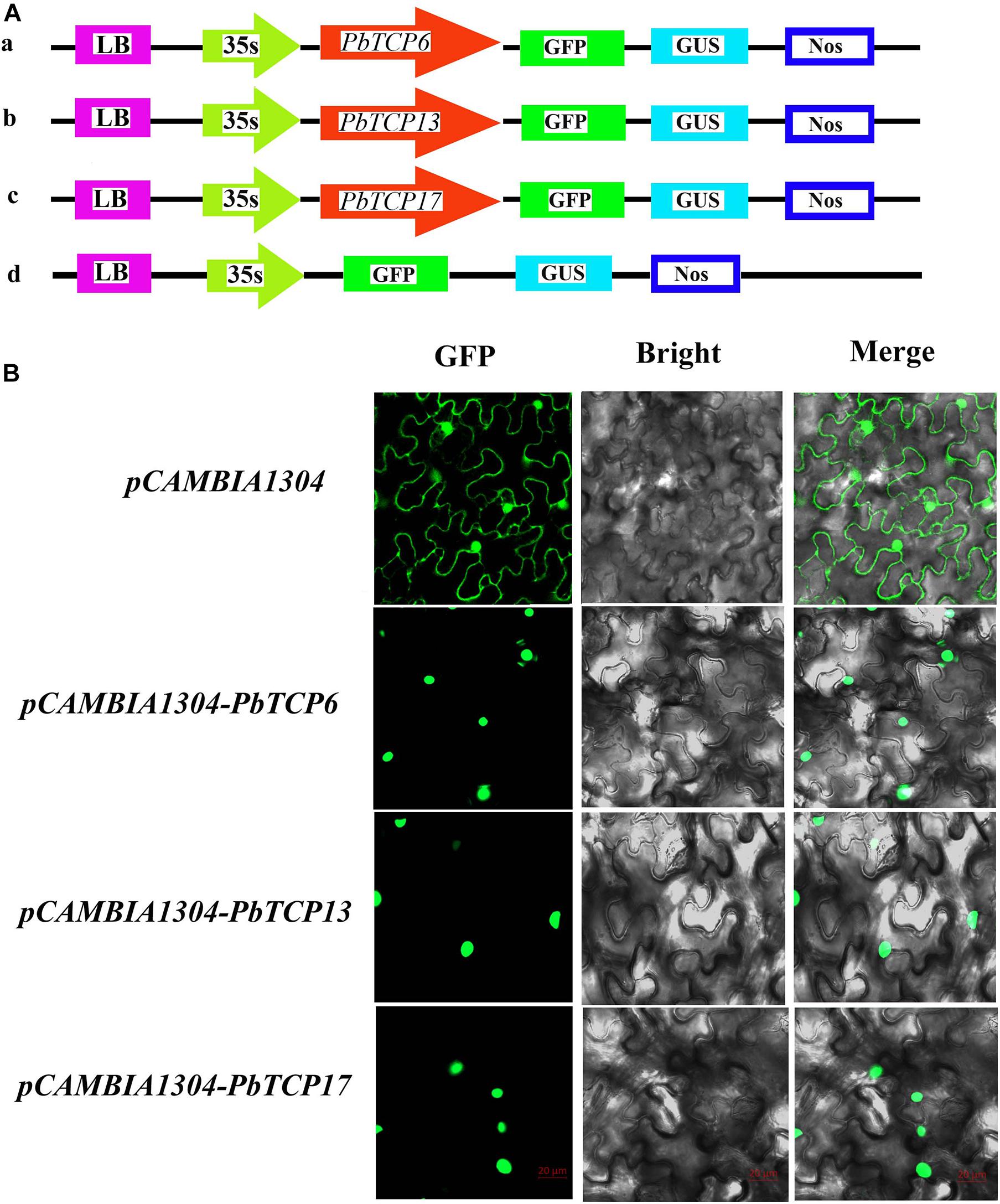

Subcellular Localization of PbTCP6, 13, and 17

Full length sequence specific primers and primers with restriction sites were designed using Primer Premier 5.0 software based on the full-length sequences of PbTCP6, 13, and 17 (PbTCP6, PbTCP13, and PbTCP17 both used Ncob I and SpeI restriction endonuclease sites) (Supplementary Table 3). “Dangshan Su” pear fruit cDNA as template was used. Finally, each gene fragment was ligated into the pCAMBIA1304 (GenBank: AF234300.1) vector used T4 DNA ligase (Takara, China) at 16°C for 3 h to obtain complete pCAMBIA1304-PbTCP6, 13, and 17 recombinant plasmids.

The pCAMBIA1304-PbTCP6, 13, and 17 recombinant plasmid, and pCAMBIA1304 empty plasmid Agrobacterium tumefaciens were cultured. Then mixed the infection liquid (10 mM MES, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM AS). Finally, the OD600 value of bacteria solution was adjusted between 0.6 and 0.8. The growing well and flat tobacco leaves were selected for injection. The infection solution was injected into the lower epidermis of tobacco leaf and cultured in the dark for 48 h (Sufficient water should be kept during dark culture). After dark culture, the tobacco leaf tissue near the injection hole was selected and placed on the glass slide. The fluorescence of GFP protein was observed under confocal laser scanning microscopy.

Results

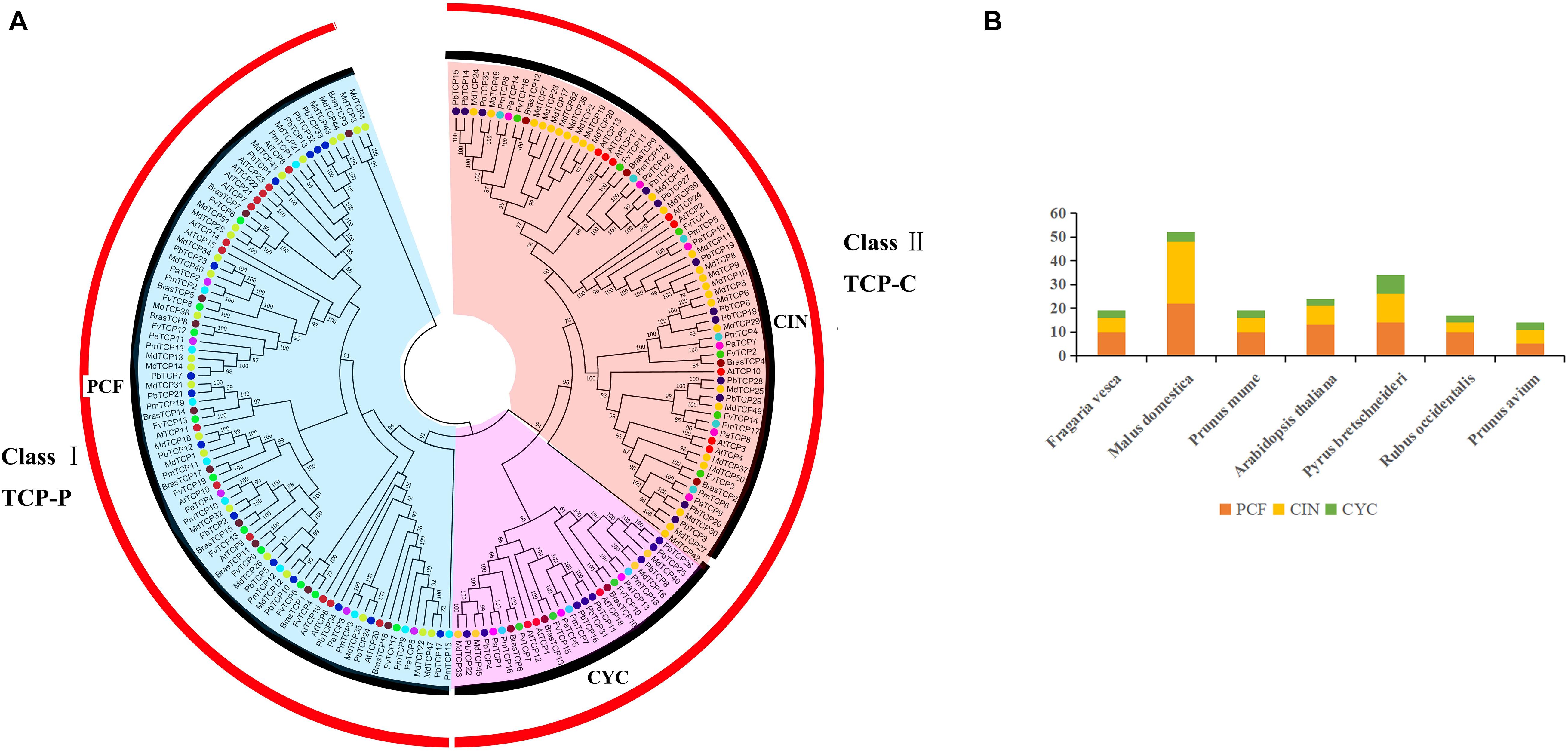

Identification, Characterization, and Phylogenetic Analysis of TCP Genes

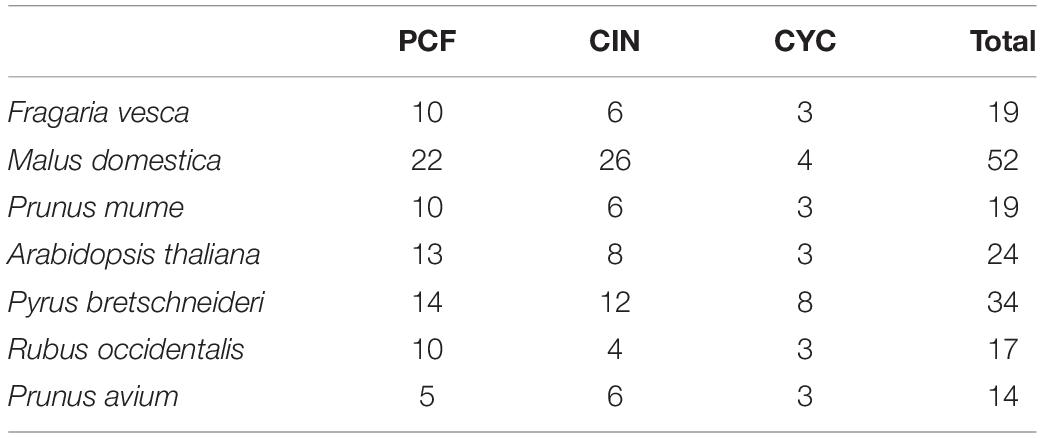

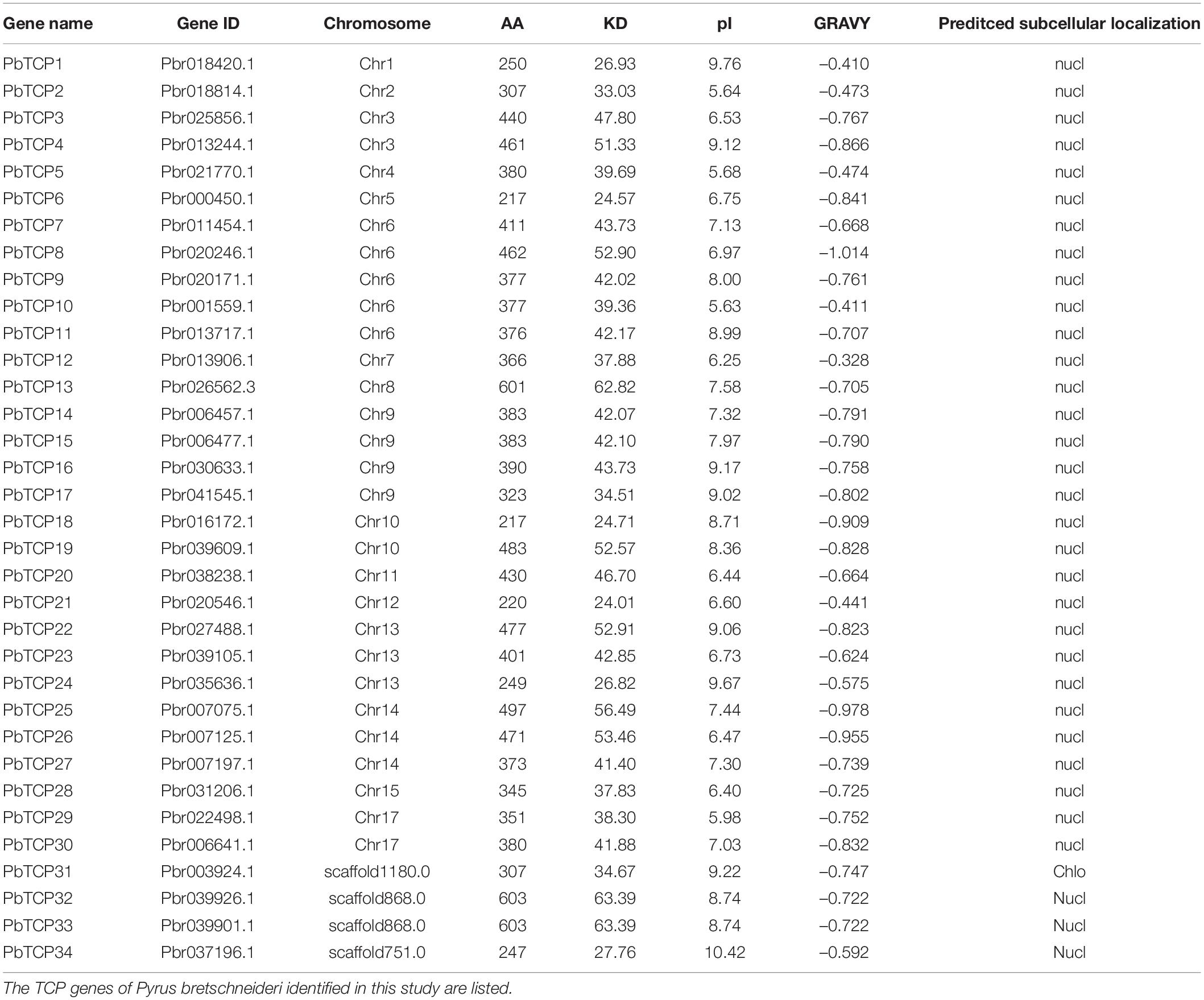

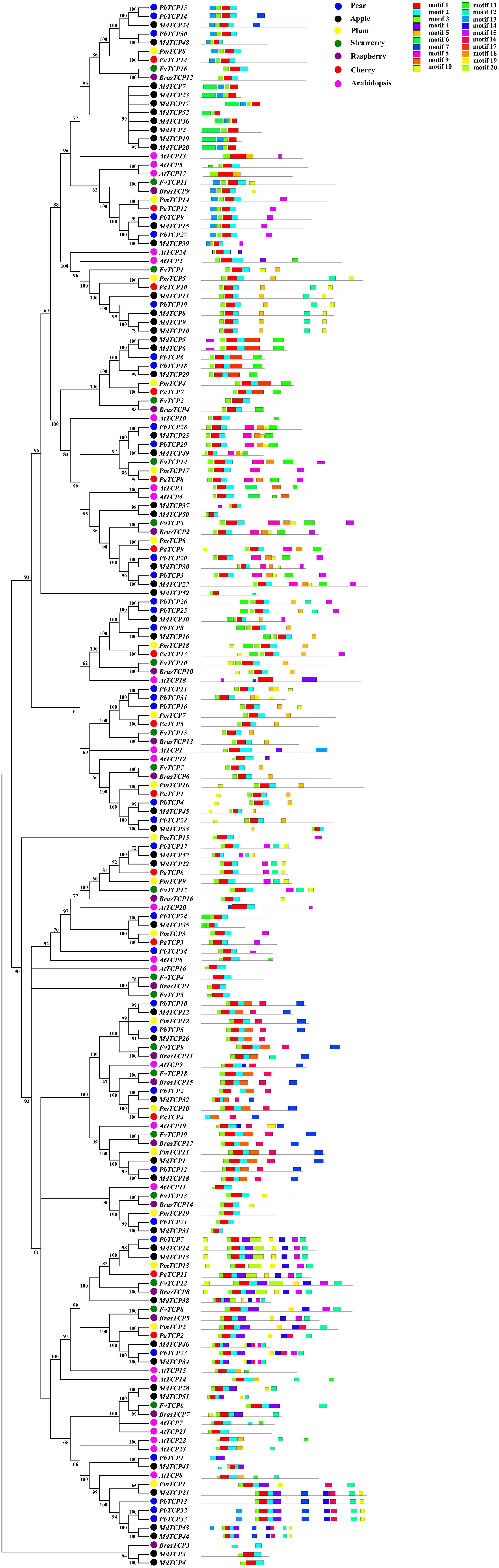

Firstly, we used the HMM for obtaining PF03634 of the conservative domain as the search criteria to compare six Rosaceae species in the protein database (Supplementary Table 1). Thirty-four TCP genes were identified in pear and 121 genes were identified in the other five Rosaceae species, including strawberry (19), apple (52), plum (19), raspberry (17), and cherry (14) (Table 1). Finally, we constructed phylogenetic trees with six Rosaceae species and Arabidopsis using the Neighbor-Joining method. The phylogenetic tree was divided into two subgroups: PCF was in Class I, CIN, and CYC were in Class II (Figure 1). Among them, CYC members had the least members, 3 in strawberry, 4 in apple, 3 in plum, 3 in Arabidopsis, 8 in pear, 3 in raspberry, 3 in cherry. Compared to CYC, PCF had more members, apple had 22 members, followed by pear (14), Arabidopsis (13), strawberry (10), raspberry (10), plum (10) and cherry (5) (Table 1). Additionally, we calculated the physicochemical parameters of TCP genes in six Rosaceae species. Among these six Rosaceae species, the pI value was 4.62–10.65 and the molecular weight ranges from 12.82 to 69.01. The GRAVY values of all TCP proteins were negative. 99% of TCP genes were located in the nucleus (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 4).

Figure 1. Phylogenetic relationships and subfamily designations in TCP proteins from Pyrus bretschneideri, Fragaria vesca, Prunus mume, Rubus occidentalis, Prunus avium, Malus domestica, and Arabidopsis thaliana. (A) Interspecific phylogenetic tree of TCP protein sequences from 7 species. (B) Number of genes in each subfamily of 7 species.

To further understanding about the potential function of TCP family in six Rosaceae species, we analyzed 155 TCP genes by GO analysis. The results showed that TCP genes could be divided into three categories: cellular component, biological process and molecular function. In molecular function, most genes were enriched in transcriptional regulatory activity. In biological process, TCP genes of six Rosaceae species were found in three GO terms (regulation of biological process, biological regulation, metabolic process). Among cellular components, organelle part and membarane enclosed activity were only found in a few genes of apple (Supplementary Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 5).

Conserved Structure Analysis of TCP Genes

In order to study the evolutionary relationship of TCP genes, we analyzed the conservative structure in six Rosaceae species. In this study, we used MEME to predict 20 motifs of TCP genes, and the results showed that members of TCP genes were highly conservative (motif 1, 2, 3) (Figure 2). We used ClustalX 2.0 to align the protein sequences. After alignment, TCP proteins were divided into two subgroups. Most of the TCP domains in each species were composed of 55–60 amino acids, which conform to the basic HLH structure (Supplementary Figures 2–7). In the basic region of TCP, several specific amino acids could bind to DNA, which was relatively conservative. In the region of helix 1 and 2, the amino acid sequences of TCP-P and TCP-C were different. In the TCP-C subfamily, most of the CYC genes contained an R domain (Supplementary Figures 2–7).

Figure 2. Predicted Pyrus bretschneideri, Fragaria vesca, Prunus mume, Rubus occidentalis, Malus domestica, Prunus avium, and Arabidopsis thaliana TCP protein conserved motifs.

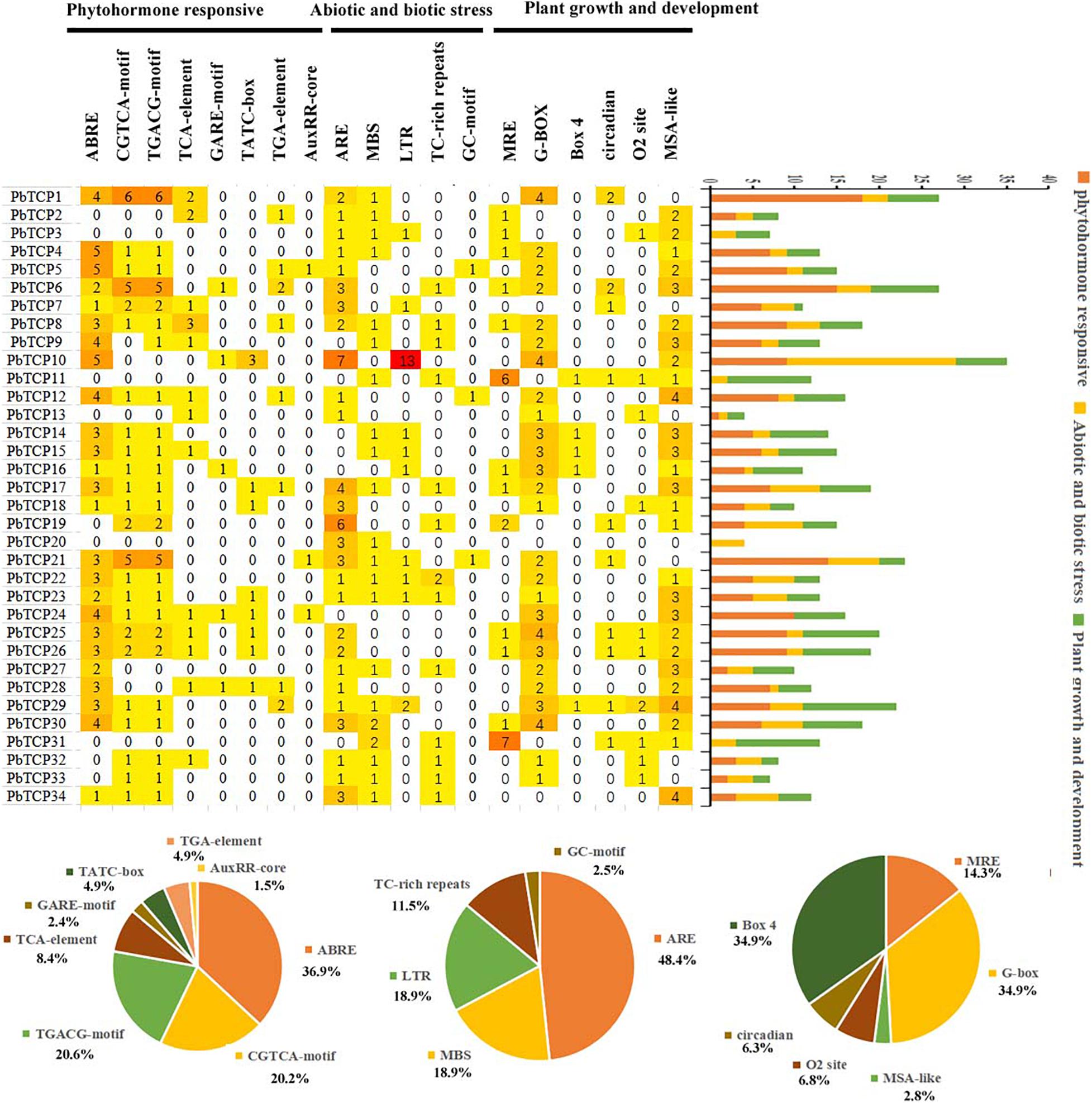

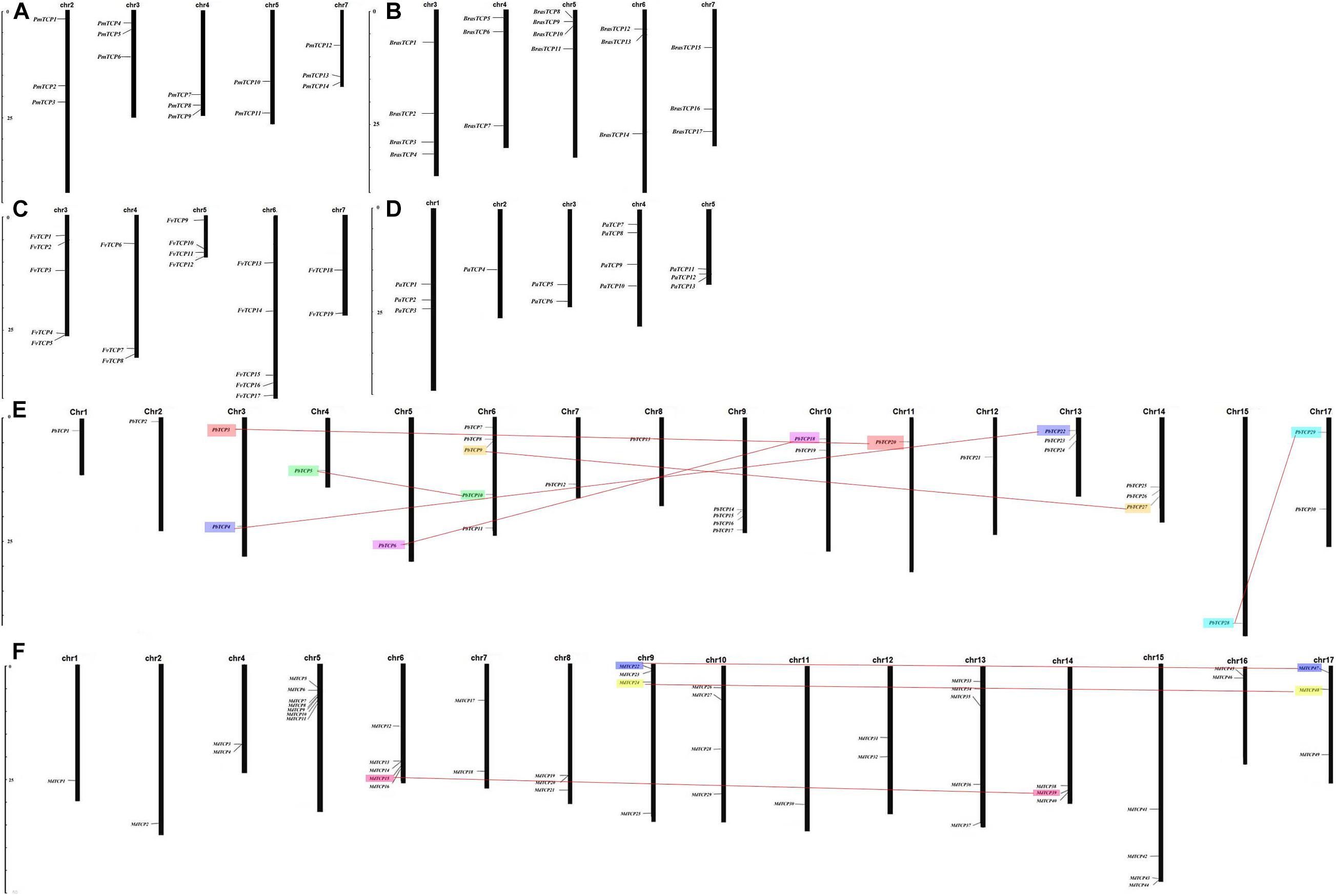

Chromosomal Location and Duplication Events of TCP Genes in Six Rosaceae Species

According to the whole genome data of strawberry, apple, plum, pear, raspberry, cherry, the exact chromosome physical location information of all TCP genes were determined (Figure 3). In the pear, 4 out of 34 TCP genes were not located on any chromosome, and 30 TCP genes were located on 16 chromosomes (except chromosome 16). In strawberry, TCP genes were located on chromosome 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7. Five genes in plum were not located on any chromosome, and other genes were located on chromosome 2, 3, 4, 5, and 7. In raspberry, TCP genes were mainly distributed on chromosomes 3 and 5, and other genes were distributed on chromosomes 4, 6, and 7. In cherry, four genes were distributed on chromosome 4, three genes on chromosome 1 and 5, and the remaining three genes on chromosome 2 and 3. In apple, there are no genes on chromosome 3 and three genes are not located on any chromosome.

Figure 3. Chromosomal locations of Six Rosaceae species. Chromosomal locations of TCP genes in (A) Prunus mume, (B) Rubus occidentalis, (C) Fragaria vesca, (D) Prunus avium, (E) Pyrus bretschneideri, and (F) Malus domestica. Duplicated gene pairs are connected with colored lines.

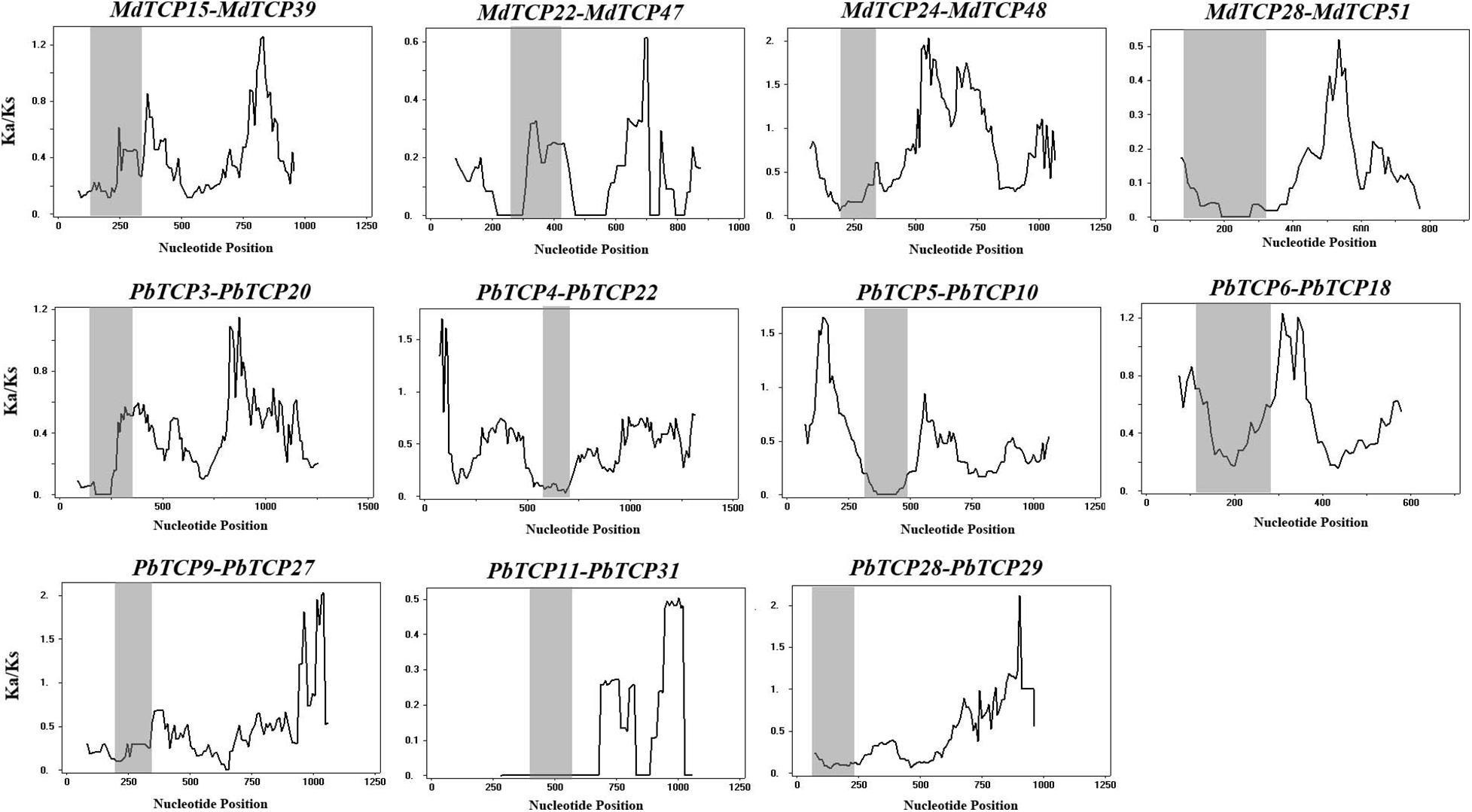

Among the six Rosaceae species, only 11 gene duplication events were identified in pear and apple (Supplementary Table 6). Seven duplication events were identified in pear and 4 in apple. In order to study the effect of duplication events on gene evolution, we counted the values of Ka, Ks, and Ka/Ks of 11 duplicated gene pairs were analyzed them. Among these 11 gene duplication events, Ka/Ks values were <1, with the maximum value of 0.907 (MdTCP24-MdTCP48) and the minimum value of 0.097 (MdTCP28-MdTCP51). These results indicated that TCP family genes were mainly affected by purifying selection during evolution.

Among the 11 gene duplication events, 9 pairs were fragment duplication events and two pairs were not located any chromosome. These results indicated that the expansion of TCP genes were mainly driven by fragment duplication. To understand the selection pressure of TCP family in the evolution process, we performed sliding window analysis (Figure 4). Sliding window analysis, results implied that the Ka/Ks values of TCP conservative domains were <1. Most coding site Ka/Ks ratios were <1, with exceptions for one or several distinct peaks (Ka/Ks > 1).

Figure 4. Sliding window plots of duplicated TCP genes in Pyrus bretschneideri and Malus domestica. The gray shaded portion indicates conserved TCP domain. The X-axis indicates the synonymous distance within each gene.

Analysis of cis-Acting Elements in TCP Gene Promoter

In plant growth and development, gene-specific expression was mainly related to cis-acting elements of upstream promoter. In this experiment, we had been analyzed the cis-acting elements of 34 members of TCP gene promoter in pear. We divided the functional elements into three types: plant growth and development, biological and abiotic stress responses, and phytohormone responses (Figure 5 and Supplementary Table 7). In phytohormone responses, there were many cis-acting elements related to the responses to hormones, including responses to methyl jasmonate (CGTCA-motif, TGACG-motif), gibberellin (TATC-box, GARE-motif), auxin (TGA-element, AuxRR-core), abscisic acid (ABRE), and salicylic acid (TCA-element). In 34 members of TCP family, the cis-acting element related to the responses to abscisic acid appeared 75 times. In plant growth and development, including the light response elements (MRE, Box 4, G-Box), cell cycle regulation (MSA-like), zein metabolism regulation (O2-site), day and night control (circadian), in which the proportion of light response elements was more, Box4, G-box each appeared 61 times. In biological and abiotic stress responses mainly included drought (MBS), defense and stress (TC rich repeats), hypoxia specific inducible enhancer like elements (GC motif), anaerobic (ARE), and low temperature (LTR).

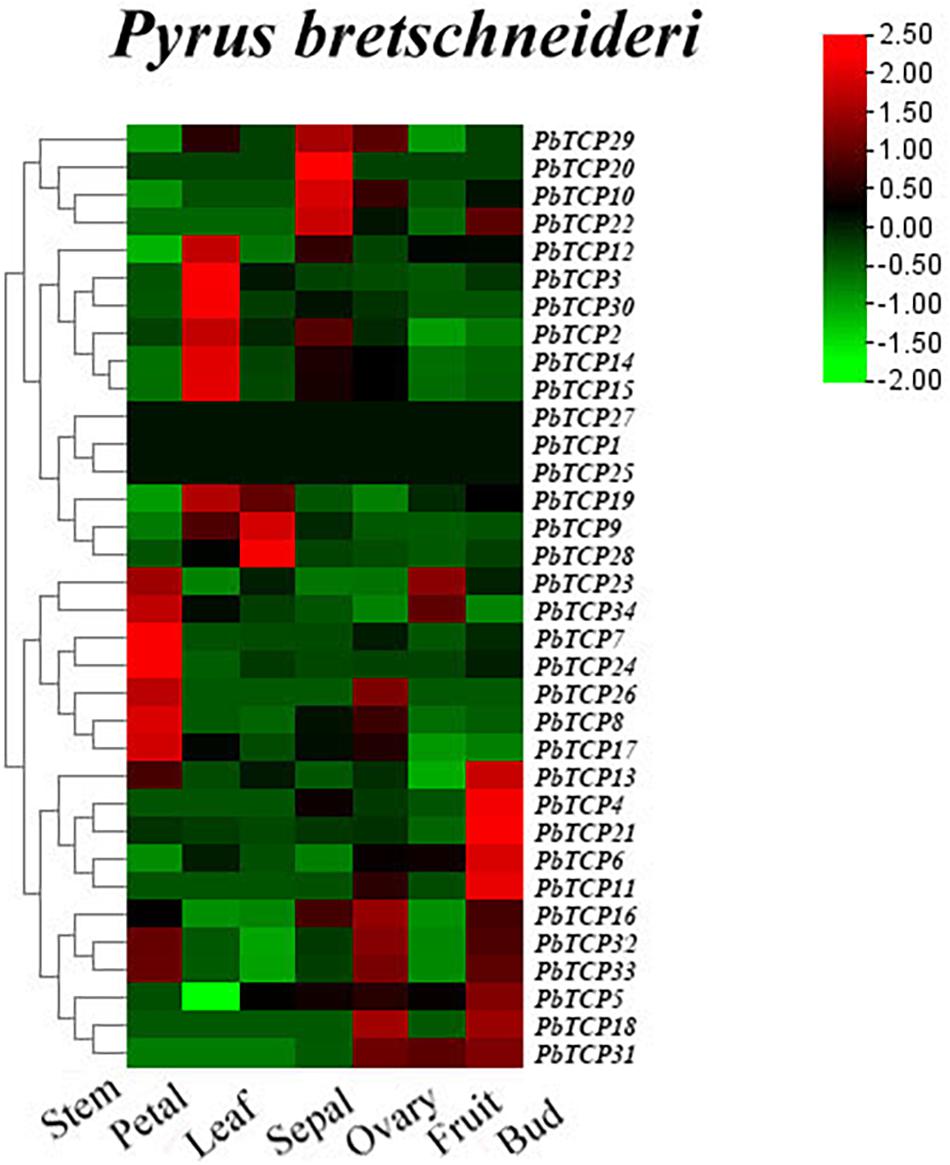

Expression Profile Analysis of PbTCPs in Different Tissues of Chinese White Pear

In order to further study the function of PbTCPs in flower, we analyzed the expression patterns of 34 TCP genes in petal, sepal, ovary, bud, stem, leaf according to the RNA-seq database. As shown in Figure 6, three genes (PbTCP1, 25, 27) were not expressed in all tissues. PbTCP2, 3, 12, 14, 15, and 30 were highly expressed in petals. The expression levels of PbTCP16, 18, 31, 32, and 33 were higher in ovary, which might affect the growth and development of fruits in the later stage. Comparing with other tissues, the expression of almost all genes in mature fruit was relatively low. Four genes (PbTCP10, 20, 22, 29) were highly expressed in sepal. About 30% genes were highly expressed in buds and stems.

Figure 6. Expression profiles of PbTCP genes in different tissues of Pyrus bretschneideri. The heatmap was generated by TBtools software according to the RNA-seq database. Log2-based-fold changes were used to create a heatmap. As shown in the bar at the upper right corner, the gene transcription level is expressed in different colors on the map.

Expression Characteristics of Chinese White Pear TCP Genes

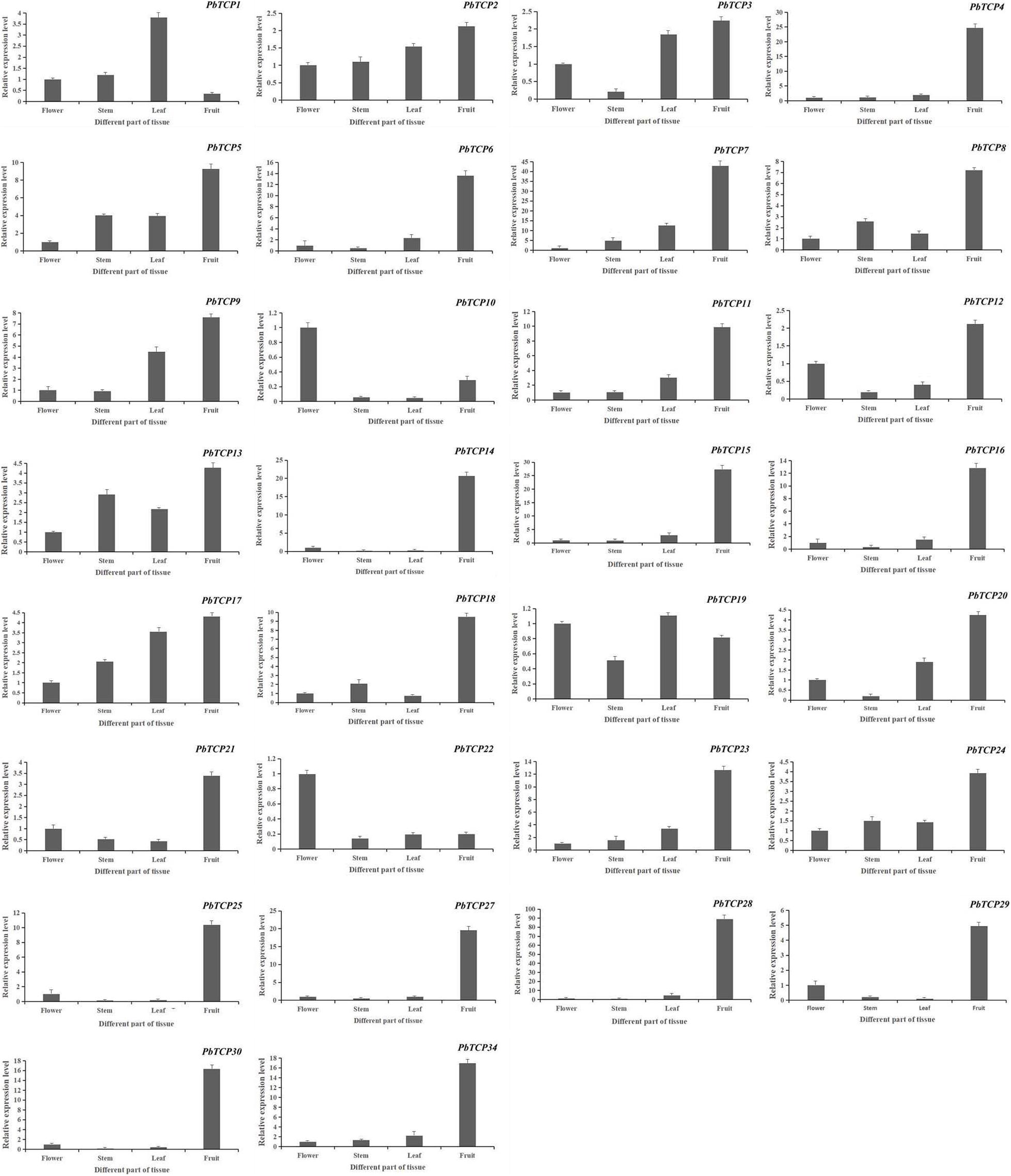

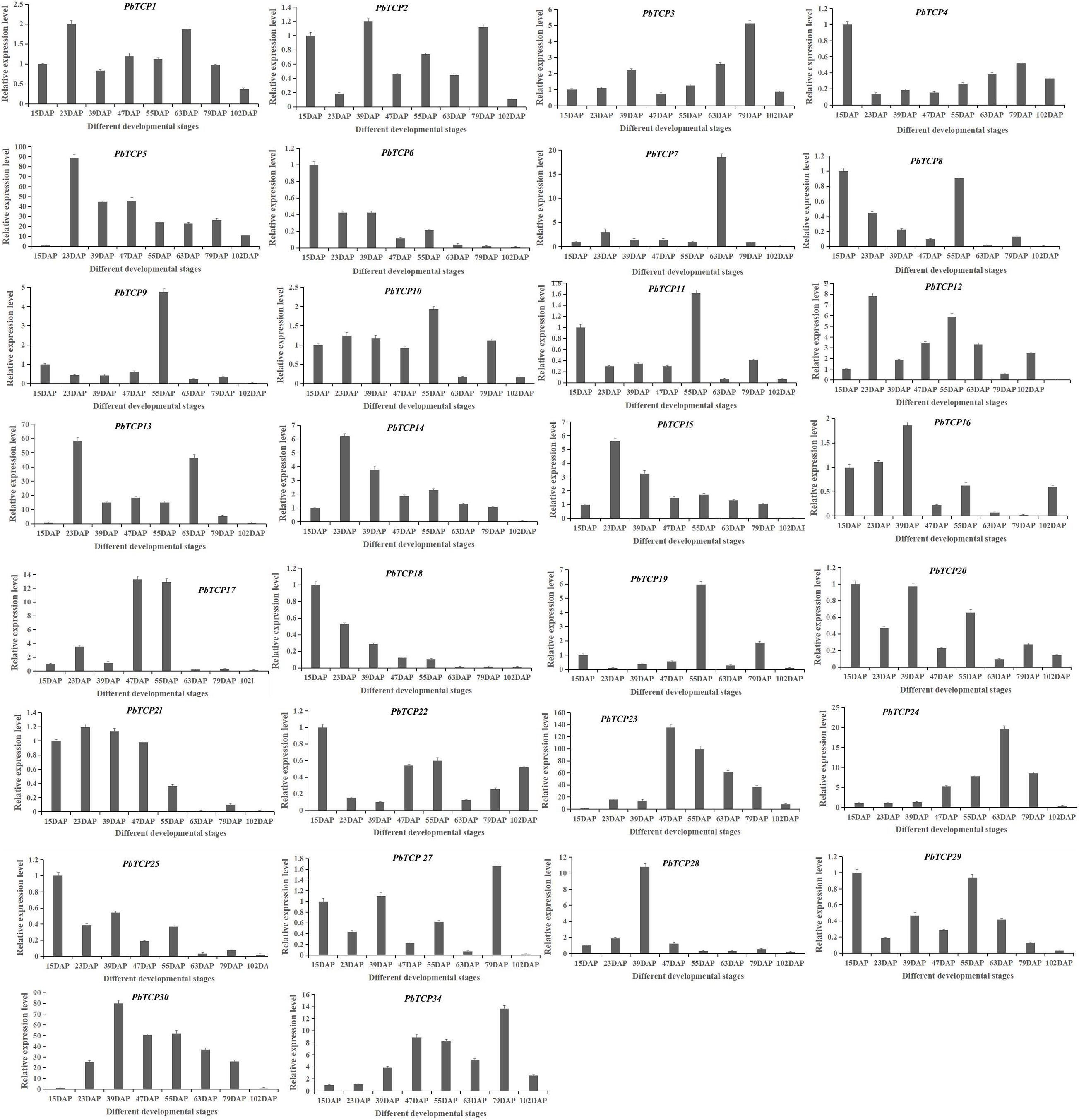

In order to further study the function of TCP genes in pear, we studied the expression of TCP genes in different tissues. As shown in Figure 7, PbTCP26, 31, 32, and 33 were not expressed in any tissues. PbTCP10, 19, and 22 were highly expressed in flowers, and PbTCP1 was highly expressed in leaves. Other genes were highly expressed in fruits.

Figure 7. Expression pattern of PbTCPs across different tissues (fruit, stems, flowers, and leaves). Error bars show the standard error between three replicates.

We analyzed the expression level in seven development stages of Chinese white pear (Figure 8). These results showed that the expression pattern of PbTCP7 reached a peak at 63 DAP. The expression of PbTCP9 and PbTCP19 reached a peak only at 55 DAP, but the expression level was very low at other developmental stages. Firstly, the expression level of PbTCP14, 15, 23, and 24 were increased, then the expression level decreased during fruit development. The expression of PbTCP6 and PbTCP18 reached a peak at the 15 DAP.

Figure 8. Expression pattern of PbTCPs across different developmental stages (15DAP, 23DAP, 39DAP, 47DAP, 55DAP, 63DAP, 79DAP, and 102DAP). Error bars show the standard error between three replicates.

Gibberellin Response Pattern Analysis of PbTCPs

The results of expression profile analysis and qRT-PCR showed that PbTCP10, 19, and 22 were highly expressed in flowers (Supplementary Figure 8). In this experiment, the buds of “Dangshan Su” pear were treated with exogenous GA, and the expression patterns of PbTCP10, 19, and 22 were analyzed. After GA treatment, these three genes expressed two response patterns. The expression of PbTCP10 increased significantly at 2 HPT, maintained at a high level at 4–8 HPT, and returned to the initial level at 12 HPT. There was no significant change in the transcriptional level of PbTCP19 and PbTCP22 under exogenous GA treatment.

Subcellular Localization of PbTCP6, 13, and 17

The main function of transcription factors is to connect with cis-acting elements of gene promoter in the nucleus. In order to study the subcellular localization of TCP genes in pear, three TCP genes were connected with 35S promoter containing green fluorescent protein (GFP). These three genes and empty vector were transiently expressed in tobacco. As shown in Figure 9, these three genes were located in the nucleus, and the empty vector was located in the nucleus and cell membrane, which was consistent with the predicted results.

Figure 9. Subcellular localization of three PbTCP genes. (A) Schematic illustration of vectors pCAMBIA1304 and PbTCPs. (B) The three pCAMBIA1304-PbTCPs fusion proteins (pCAMBIA1304-PbTCP6, pCAMBIA1304-PbTCP13, pCAMBIA1304-PbTCP17), and pCAMBIA1304 as a control were transiently expressed in tobacco leaf and observed under fluorescence microscope.

Discussion

TCP proteins are transcription factors that are unique in plants and are involved in leaf development, flower symmetry, stem branching, and other biological processes. TCP proteins can also regulate the flowering process and secondary wall formation and ultimately affect plant growth and development (Nag et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2015). In this study, 155 genes were identified in six Rosaceae plants. All genes contained a TCP conserved domain, and their proteins were hydrophilic with a negative GRAVY value (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 4). In the six Rosaceae species, all genes were divided into two subgroups, and the number of Class I (TCP-P) members was generally greater than that of Class II (TCP-C) members. However, in apple, pear and cherry, there were more TCP-C members than TCP-P members (Table 1). According to the number of TCP genes in each species, there are the most TCP genes in apple (52), followed by pear (34). The number of TCP family members of apple and pear were more than other species (Table 1). These differences might be related to the evolution of the TCP family.

Whole-genome duplication (WGD) or polyploidy is an important driving force shaping plant evolution (Tang et al., 2008). Previous studies indicated that pear, strawberry, apple and other dicotyledons had a whole-genome duplication event before 140 million years ago (Mya). However, apple and pear experienced a whole-genome duplication event 30–40 Mya (Shulaev et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2013). After that, the chromosome number of pear and apple changed to 17, strawberry changed to 7, plum changed to 8 and raspberry changed to 7, and cherry changed to 8. These results indicated that the second WGD, the 9 chromosomes in the common ancestor of Rosaceae underwent doubling, breaking, hybridization and fusion. The conserved domains were closely related to the diversity of gene functions. The structures within a subfamily were similar, which indicated that these genes might have similar functions. In the HLH domain, the second helix region had a specific LXXLL motif, and members of the CYC/TB1 subfamily specifically contained a hydrophilic α helix (R domain) rich in polar amino acids, which did not exist in other members (Supplementary Figures 2–7). The difference in gene number and the retention of conserved structures might be due to the loss of TCP family genes, chromosome doubling, and selection pressure in the process of WGDs.

To understand the evolutionary patterns of TCP family genes in six Rosaceae species, we calculated the values of Ka and Ks (Figure 4 and Supplementary Table 6). These results showed that collateral gene pairs only existed in apple and pear, and the Ka/Ks values of all gene pairs were <1, which indicated that the TCP family had undergone obvious purifying selection in the evolutionary process. Interestingly, there were two gene pairs (PbTCP28-PbTCP29, MdTCP24-MdTCP48) with relatively high Ka/Ks values (>0.5), which might be due to the rapid evolution and diversification of these two genes after the duplication event.

Plant flowering is an important life activity in the process of plants transitioning from vegetative growth to reproductive growth. Many genes are involved in the flowering process of plants, such as FLS (Park et al., 2020), MADS (Tang et al., 2020), and CDF (Corrales et al., 2014). Recent studies have shown that TCP genes also play a regulatory role in plant flowering (Lucero et al., 2017; Li et al., 2019). We used public transcriptome data and qRT-PCR to obtain the expression pattern of TCP genes in “Dangshan Su” pear. These results showed that there was expression in all tissues results of TCP genes, which indicated that TCP genes played an important role during growth and development in pear. The qRT-PCR results in different tissues showed that PbTCP10, 19, and 22 were highly expressed in flowers (Figure 7). According to expression profile analysis, PbTCP10 and PbTCP22 were highly expressed in the sepal. PbTCP19 was highly expressed in the petal (Figure 6). Previous studies showed that hormones (especially GA), sugar and light also play an important role in flowering regulation (Srikanth and Schmid, 2011; Osnato et al., 2012; Cao et al., 2018). In the analysis of cis-acting elements, it could be seen that the promoter regions of PbTCP10 contained GA-responsive elements (TATC-box, GARE-motif). After exogenous GA treatment, the expression patterns of PbTCP10, 19, and 22 showed that the expression of PbTCP19 and PbTCP22 were almost not induced by GA, and the expression of PbTCP10 increased significantly at 2 HPT (Supplementary Figure 8). These phenomenons might be due to the absence of GA response element in the promoter of PbTCP19 and PbTCP22. In addition, we found that the cis-acting elements of PbTCP10 promoter contained light response elements, which indicated that PbTCP10 might be involved in photoperiodic signal (Figure 5). In conclusion, PbTCP10 might be involved in GA regulated flowering induction pathway and regulate photoperiod.

Previous studies found that the formation of stone cells in “Dangshan Su” pear mainly occurred in the early stage of fruit formation (15–47 DAP) (Su et al. 2019). Therefore, TCP genes with high expression level in the early stage of fruit development might be involved in the formation of stone cells. The genes with high expression in late stage might be involved in the accumulation of sugar and the response of hormone during fruit ripening. In order to determine the effect of TCP genes on secondary wall formation during fruit development of “Dangshan Su” pear, qRT-PCR analysis was conducted at different stages of fruit development (Figure 8). The results showed that PbTCP14, 15, 23, and 24 increased firstly and then decreased during fruit development, which was consistent with the trend of stone cell formation, but only PbTCP14 and PbTCP15 were highly expressed in the early stage of fruit development. Therefore, PbTCP14 and PbTCP15 might be involved in the stone cell formation during fruit development of “Dangshan Su” pear.

Through comparative genomics analysis, we identified the evolution of TCP genes in six Rosaceae species, and screened candidate regulatory genes related to flowering (PbTCP10) and stone cell formation (PbTCP14 and PbTCP15). In the following study, we will analysis the biological functions of these genes and provide an important theoretical basis for improving pear quality.

Conclusion

In this work, 155 TCP genes were identified in six Rosaceae species. According to bioinformatics analysis, we explained the possible evolutionary patterns of TCP genes in six Rosaceae species. By qRT-PCR analysis of 34 TCP genes in different development stages and tissues of pear, we found that PbTCP14 and PbTCP15 might be involved in the formation of secondary wall during pear fruit development, and PbTCP10 might be involved in the process of flowering induction by GA. In general, these results provided a theoretical basis for improving the quality of pear.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author Contributions

YZ and XS performed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. XW, MW, and XC analyzed the data. MA and GL helped to polish the language. YC conceived and designed the experiments. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 31640068). The funding bodies were not involved in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling editor declared a past co-authorship with one of the authors YC.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgene.2021.669959/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure 1 | Gene Ontology (GO) analysis of TCP genes in six Rosaceae species (Prunus mume, Rubus occidentalis, Fragaria vesca, Prunus avium, Malus domestica, Pyrus bretschneideri).

Supplementary Figure 2 | Multiple sequence alignment of pear TCP transcription factors. Alignment of the TCP domain for the predicted pear TCP proteins. The basic, helix I, loop, and helix II regions are indicated. Alignment of the R domain of Class II subfamily members. The sequences were aligned with ClustalW.

Supplementary Figure 3 | Multiple sequence alignment of apple TCP transcription factors. Alignment of the TCP domain for the predicted apple TCP proteins. The basic, helix I, loop, and helix II regions are indicated. Alignment of the R domain of Class II subfamily members. The sequences were aligned with ClustalW.

Supplementary Figure 4 | Multiple sequence alignment of raspberry TCP transcription factors. Alignment of the TCP domain for the predicted raspberry TCP proteins. The basic, helix I, loop, and helix II regions are indicated. Alignment of the R domain of Class II subfamily members. The sequences were aligned with ClustalW.

Supplementary Figure 5 | Multiple sequence alignment of strawberry TCP transcription factors. Alignment of the TCP domain for the predicted strawberry TCP proteins. The basic, helix I, loop, and helix II regions are indicated. Alignment of the R domain of Class II subfamily members. The sequences were aligned with ClustalW.

Supplementary Figure 6 | Multiple sequence alignment of cherry TCP transcription factors. Alignment of the TCP domain for the predicted cherry TCP proteins. The basic, helix I, loop, and helix II regions are indicated. Alignment of the R domain of Class II subfamily members. The sequences were aligned with ClustalW.

Supplementary Figure 7 | Multiple sequence alignment of plum TCP transcription factors. Alignment of the TCP domain for the predicted plum TCP proteins. The basic, helix I, loop, and helix II regions are indicated. Alignment of the R domain of Class II subfamily members. The sequences were aligned with ClustalW.

Supplementary Figure 8 | Expression modes of candidate PbTCP10, 19, and 22 in Chinese white Pear buds treated with gibberellin. Error bars show the standard error between three replicates.

Supplementary Table 1 | All TCP protein sequences list.

Supplementary Table 2 | Primer sequences used in qRT-PCR.

Supplementary Table 3 | Primers for vector construction.

Supplementary Table 4 | Basic information of TCP genes in five Rosaceae species (Prunus mume, Rubus occidentalis, Fragaria vesca, Prunus avium, and Malus domestica).

Supplementary Table 5 | Blast2GO annotation details of TCP protein sequences of six Rosaceae species (Prunus mume, Rubus occidentalis, Fragaria vesca, Prunus avium, Malus domestica, Pyrus bretschneideri).

Supplementary Table 6 | Ka/Ks analysis of the TCP homologous gene pairs from Pyrus bretschneideri and Malus domestica.

Supplementary Table 7 | All TCP gene promoter sequences list.

Footnotes

- ^ http://gigadb.org/dataset/10008

- ^ https://www.rosaceae.org/

- ^ http://www.genscript.com/wolf-psort.html

- ^ http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcarere/html/

References

Aguilar-Martinez, J. A., and Sinha, N. (2013). Analysis of the role of Arabidopsis class I TCP genes AtTCP7, AtTCP8, AtTCP22, and AtTCP23 in leaf development. Front. Plant Sci. 16:406. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00406

Artimo, P., Jonnalagedda, M., Arnold, K., Baratin, D., Csardi, G., Castro, E., et al. (2012). ExPASy:SIB bioinformatics resource portal. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, W597–W603.

Broholm, S. K., Tähtiharju, S., Laitinen, R. A. E., Albert, V. A., Teeri, T. H., and Elomaa, P. (2008). A TCP domain transcription factor controls flower type specification along the radial axis of the Gerbera (Asteraceae) inflorescence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 105, 9117–9122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801359105

Cao, J. F., Zhao, B., Huang, C. C., Chen, Z. W., Zhao, T., Liu, H., et al. (2020). The miR319-targeted GhTCP4 promotes the transition from cell elongation to wall thickening in cotton fiber. Mol. Plant 13, 1063–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2020.05.006

Cao, K., Yan, F., Xu, D. W., Ai, K. Q., Yu, J., Bao, E. C., et al. (2018). Phytochrome B1-dependent control of SP5G transcription is the basis of the night break and red to far-red light ratio effects in tomato flowering. BioMed Central 18:158.

Cao, Y. P., Li, X. X., and Jiang, L. (2019). Integrative analysis of the core fruit lignification toolbox in pear reveals targets for fruit quality bioengineering. Biomolecules 9:504. doi: 10.3390/biom9090504

Cheng, X., Li, M. L., Abdullah, M., Li, G. H., Zhang, J. Y., Manzoor, M. A., et al. (2019). In silico genome-wide analysis of the pear (Pyrus bretschneideri) KNOX family and the functional characterization of PbKNOX1, an Arabidopsis BREVIPEDICELLUS orthologue gene, involved in cell wall and lignin biosynthesis. Front. Genet. 10:632. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.00632

Corrales, A. R., Nebauer, S. G., Carrillo, L., Fernandez-Nohales, P., Marques, J., Renau-Morata, B., et al. (2014). Characterization of tomato Cycling Dof Factors reveals conserved and new functions in the control of flowering time and abiotic stress responses. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 995–1012. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert451

Cubas, P., Lauter, N., Doebley, J., and Coen, E. (1999). The TCP domain: a motif found in proteins regulating plant growth and development. Plant J. 18, 215–222. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00444.x

Doebley, J., Stec, A., and Hubbard, L. (1997). The evolution of apical dominance in maize. Nature 386, 485–488. doi: 10.1038/386485a0

Feng, X. Z., Zhao, Z., Tian, Z. X., Xu, S. L., Luo, Y. H., Cai, Z. G., et al. (2006). Control of petal shape and floral zygomorphy in lotus japonicus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 103, 4970–4975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600681103

Huang, T. B., and Irish, V. F. (2015). Temporal control of plant organ growth by TCP transcription factors. Curr. Biol. 25, 1765–1770. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.05.024

Hubbard, L., McSteen, P., Doebley, J., and Hake, S. (2002). Expression patterns and mutant phenotype of teosinte branched1 correlate with growth suppression in maize and teosinte. Genetics 162, 1927–1935. doi: 10.1093/genetics/162.4.1927

Horton, P., Park, K. J., Obayashi, T., Fujita, N., Harada, H., Adams-Collier, C. J., et al. (2007). WoLF PSORT: protein localization predictor. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W585–W587.

Kumar, S., Stecher, G., and Tamura, K. (2016). MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evolut. 33, 1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054

Kieffer, M., Master, V., Waites, R., and Davies Brendan. (2011). TCP14 and TCP15 affect internode length and leaf shape in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 68, 147–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313x.2011.04674.x

Kosugi, S., and Ohashi, Y. (1997). PCF1 and PCF2 specifically bind to cis elements in the rice proliferating cell nuclear antigen gene. Plant Cell 9, 1607–1619. doi: 10.2307/3870447

Letunic, I., Doerks, T., and Bork, P. (2012). SMART 7: recent updates to the protein domain annotation resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D302–D305.

Luo, D., Carpenter, R., Vincent, C., Copsey, L., and Coen, E. (1996). Origin of floral asymmetry in Antirrhinum. Nature 383, 794–799. doi: 10.1038/383794a0

Luo, D., Carpenter, R., Copsey, L., Vincent, C., Clark, J., and Coen, E. (1999). Control of organ asymmetry in flowers of Antirrhinum. Cell 99, 367–376. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81523-8

Li, D. B., Zhang, H. Y., Mou, M. H., Chen, Y. L., Xiang, S. Y., Chen, L. G., et al. (2019). Arabidopsis class II TCP transcription factors integrate with the FT-FD module to control flowering. Plant Physiol. 181, 97–111. doi: 10.1104/pp.19.00252

Librado, P., and Rozas, J. (2009). DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics 25, 1451–1452. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp187

Liu, J., Cheng, X. L., Liu, P., Li, D. Y., Chen, T., Gu, X. F., et al. (2017). MicroRNA319-regulated TCPs interact with FBHs and PFT1 to activate CO transcription and control flowering time in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 13:e1006833. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006833

Livak, K. J., and Schmittgen, T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2 –ΔΔCT method. Methods 25, 402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262

Lucero, L. E., Manavella, P. A., Gras, D. E., Ariel, F. D., and Gonzalez, D. H. (2017). Class I and Class II TCP transcription factors modulate SOC1-Dependent flowering at multiple levels. Mol. Plant 10, 1571–1574. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2017.09.001

Ma, Y., Zhang, F. Y., Bade, R., Daxibater, A., Men, Z. H., and Hasi, A. (2015). Genome-Wide Identification and Phylogenetic Analysis of the ERF gene family in melon. J. Plant Growth Regulat. 34, 66–77. doi: 10.1007/s00344-014-9443-z

Manassero, N. G., Uberti, V., Ivana, L., Welchen, E., and Gonzalez, D. H. (2013). TCP transcription factors: architectures of plant form. BioMol. Concepts 4, 111–127. doi: 10.1515/bmc-2012-0051

Nag, A., King, S., and Jack, T. (2009). MiR319a targeting of TCP4 is critical for petal growth and development in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 106, 22534–22539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908718106

Nath, U., Crawford, B. C. W., Carpenter, R., and Coen, E. (2003). Genetic control of surface curvature. Science 299, 1404–1407. doi: 10.1126/science.1079354

Ori, N., Cohen, A. R., Etzioni, A., Brand, A., Yanai, O., Shleizer, S., et al. (2007). Regulation of LANCEOLATE by miR319 is required for compound-leaf development in tomato. Nat. Genet. 39, 787–791. doi: 10.1038/ng2036

Osnato, M., Castillejo, C., Matias-Hernandez, L., and Pelaz, S. (2012). TEMPRANILLO genes link photoperiod and gibberellin pathways to control flowering in Arabidopsis. Nat. Communicat. 3:808.

Palatnik, J. F., Allen, E., Wu, X. L., Schommer, C., Schwab, R., Carrington, J. C., et al. (2003). Control of leaf morphogenesis by microRNAs. Nature 425, 257–263. doi: 10.1038/nature01958

Park, S., Kim, D. H., Yang, J. H., Lee, J. Y., and Lim, S. H. (2020). Increased flavonol levels in tobacco expressing AcFLS affect flower color and root growth. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21:1011. doi: 10.3390/ijms21031011

Resentini, F. A., Lucia, F. B., Colombo, A., David, B. M., and Masiero, A. S. (2015). TCP14 and TCP15 mediate the promotion of seed germination by gibberellins in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Plant 8, 482–485. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2014.11.018

Rombauts, S., Déhais, P., Van Montagu, M., and Rouzé, P. (1999). PlantCARE, a plant Cis-acting regulatory element database. Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 295–296. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.295

Shulaev, V., Sargent, D. J., Crowhurst, R. N., Mockler, T. C., Folkerts, O., Delcher, A. L., et al. (2011). The genome of the woodland strawberry (Fragaria vesca). Nat. Genet. 43, 109–116.

Su, X. Q., Meng, T. K., Zhao, Y., Li, G. H., Cheng, X., Muhammad, A., et al. (2019). Comparative genomic analysis of the IDD genes in five Rosaceae species and expression analysis in Chinese white pear (Pyrus bretschneideri). PeerJ 26:e6628. doi: 10.7717/peerj.6628

Su, X. Q., Zhao, Y., Wang, H., Li, G. H., Cheng, X., Jin, Q., et al. (2019). Transcriptomic analysis of early fruit development in Chinese white pear (Pyrus bretschneideri Rehd.) and functional identification of PbCCR1 in lignin biosynthesis. BMC Plant Biol. 19:417. doi: 10.1186/s12870-019-2046-x

Srikanth, A., and Schmid, M. (2011). Regulation of flowering time: all roads lead to Rome. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 68, 2013–2037. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0673-y

Tang, H. B., Bowers, J. E., Wang, X. Y., Ming, R., Alam, M., and Paterson, A. H. (2008). Synteny and collinearity in plant genomes. Science 320, 486–488. doi: 10.1126/science.1153917

Tang, X. L., Liang, M. X., Han, J. J., Cheng, J. S., Zhang, H. X., and Liu, X. H. (2020). Ectopic expression of LoSVP, a MADS-domain transcription factor from lily, leads to delayed flowering in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Rep. 39, 289–298. doi: 10.1007/s00299-019-02491-1

Uberti-Manassero, N. G., Coscueta, E. R., and Gonzalez, D. H. (2016). Expression of a repressor form of the Arabidopsis thaliana transcription factor TCP16 induces the formation of ectopic meristems. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 108, 57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2016.06.031

Van Es, S. W., Silveira, S. R., Rocha, D. I., Bimbo, A., Martinelli, A. P., Dornelas, M. C., et al. (2018). Novel functions of the Arabidopsis transcription factor TCP5 in petal development and ethylene biosynthesis. Plant J. 94, 867–879. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13904

Wang, H., Mao, Y. F., Yang, J., and He, Y. K. (2015). TCP24 modulates secondary cell wall thickening and anther endothecium development. Front. Plant Sci. 6:436. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00436

Wang, Y., Yu, Y. H., Wang, J. D., Chen, Q. J., and Ni, Z. Y. (2020). Heterologous overexpression of the GbTCP5 gene increased root hair length, root hair and stem trichome density, and lignin content in transgenic Arabidopsis. Gene 758:144954. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2020.144954

Wu, J., Wang, Z. W., Shi, Z. B., Zhang, S., Ming, R., Zhu, S. L., et al. (2013). The genome of the pear (Pyrus bretschneideri Rehd.). Genome Res. 23, 396–408.

Wu, J. F., Tsai, H. L., Joanito, I., Wu, Y. C., Chang, C. W., Li, Y. H., et al. (2016). LWD-TCP complex activates the morning gene CCA1 in Arabidopsis. Nat. Communicat. 7:13181.

Yao, X. M., Hong, W. J., and Zhang, D. B. (2007). Genome-wide comparative analysis and expression pattern of TCP gene families in Arabidopsis thaliana and Oryza sativa. J. Integrat. Plant Biol. 49, 885–897. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2007.00509.x

Ye, J., Fang, L., Zheng, H. K., Zhang, Y., Chen, J., Zhang, Z. J., et al. (2006). WEGO: a web tool for plotting GO annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, W293–W297.

Zhang, J. Y., Cheng, X., Jin, Q., Su, X. Q., Li, M. L., Yan, C. C., et al. (2017). Comparison of the transcriptomic analysis between two Chinese white pear (Pyrus bretschneideri Rehd.) genotypes of different stone cells contents. PLoS One 12:e0187114. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0187114

Zhao, Y. F., Pfannebecker, K., Dommes, A. B., Hidalgo, O., Becker, A., and Elomaa, P. (2018). Evolutionary diversification of CYC/TB1-like TCP homologs and their recruitment for the control of branching and floral morphology in Papaveraceae (basal eudicots). N. Phytol. 220, 317–331. doi: 10.1111/nph.15289

Keywords: TCP genes, flowers, development of fruit, expression patterns, genome-wide

Citation: Zhao Y, Su X, Wang X, Wang M, Chi X, Aamir Manzoor M, Li G and Cai Y (2021) Comparative Genomic Analysis of TCP Genes in Six Rosaceae Species and Expression Pattern Analysis in Pyrus bretschneideri. Front. Genet. 12:669959. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2021.669959

Received: 19 February 2021; Accepted: 19 April 2021;

Published: 17 May 2021.

Edited by:

Yunpeng Cao, Central South University Forestry and Technology, ChinaReviewed by:

Awais Shakoor, Universitat de Lleida, SpainWu Yuejin, Institute of Intelligent Machines, Hefei Institutes of Physical Science (CAS), China

Ling Xu, Zhejiang Sci-Tech University, China

Hui Song, Qingdao Agricultural University, China

Copyright © 2021 Zhao, Su, Wang, Wang, Chi, Aamir Manzoor, Li and Cai. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yongping Cai, eXBjYWlhaEAxNjMuY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Yu Zhao

Yu Zhao Xueqiang Su2†

Xueqiang Su2†