- 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Linkou Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taoyuan, Taiwan

- 2Department of Genomic Medicine and Center for Medical Genetics, Changhua Christian Hospital, Changhua, Taiwan

- 3Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Changhua Christian Hospital, Changhua, Taiwan

- 4Department of Molecular Biotechnology, Da-Yeh University, Changhua, Taiwan

- 5Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, College of Medicine, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan

- 6Department of Medical Genetics, National Taiwan University Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan

- 7Department of Medical Science, National Tsing Hua University, Hsinchu, Taiwan

- 8Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Taipei Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan

- 9College of Medicine, Chang Gung University, Taoyuan, Taiwan

- 10Prenatal Cell and Gene Therapy Group, Institute for Women’s Health University College London, London, United Kingdom

Many parents with a disabled child caused by a genetic condition appreciate the option of prenatal genetic diagnosis to understand the chance of recurrence in a future pregnancy. Genome-wide tests, such as chromosomal microarray analysis and whole-exome sequencing, have been increasingly used for prenatal diagnosis, but prenatal counseling can be challenging due to the complexity of genomic data. This situation is further complicated by incidental findings of additional genetic variations in subsequent pregnancies. Here, we report the prenatal identification of a baby with a MECP2 missense variant and 15q11.2 microduplication in a family that has had a child with developmental and epileptic encephalopathy caused by a de novo KCNQ2 variant. An extended segregation analysis including extended relatives, in addition to the parents, was carried out to provide further information for genetic counseling. This case illustrates the challenges of prenatal counseling and highlights the need to understand the clinical and ethical implications of genome-wide tests.

Introduction

Having a child with disabilities caused by genetic variations can be a traumatic experience for any family. Parents of affected children often face substantial stress with intense feelings of anxiety, fear, and depression. They often seek counseling to understand the chance of recurrence of the genetic condition in a future pregnancy (Hall et al., 2012; van Warmerdam et al., 2019; Baenziger et al., 2020). Prenatal genetic diagnosis is an option for subsequent pregnancies of those couples seeking to reduce the chance of recurrence.

Genome-wide tests, such as whole-exome sequencing (WES) and chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA), which includes a more detailed analysis of the human genome, have gradually become more popular in the setting of prenatal diagnosis (Chang et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2020). WES provides comprehensive detection of variants in the exonic regions of genes of a genome compared with an analysis of a selective few genes. It is thought to be an efficient strategy for the diagnosis of rare diseases, where a monogenic disorder is highly suspected, but the underlying cause remains unclear or unknown (Jelin and Vora, 2018). CMA allows rapid detection of unbalanced chromosomal anomalies, such as microdeletions and duplications, and identifies genes responsible for the phenotypes of copy number variants (CNVs) (Ceylan et al., 2018).

To reduce the chance of recurrence, couples often prefer prenatal genomic tests for comprehensive detection of variants. However, prenatal counseling can be challenging due to the complexity of genomic data (Schmidt et al., 2019). This situation is further complicated by incidental (or secondary) findings that are not related to the initial indication of the prenatal diagnostic test.

Here, we report the prenatal identification of a baby with a MECP2 missense variant and 15q11.2 microduplication in a family that has had a child with developmental and epileptic encephalopathy (DEE) caused by a de novo KCNQ2 missense variant. To cope with the incidental finding at the prenatal stage, an extended segregation analysis including extended relatives, in addition to the parents, was carried out to provide further information for genetic counseling. This case illustrates the challenges of prenatal counseling and highlights the need to understand the clinical and ethical implications of genome-wide tests.

Materials and Methods

Case Presentation

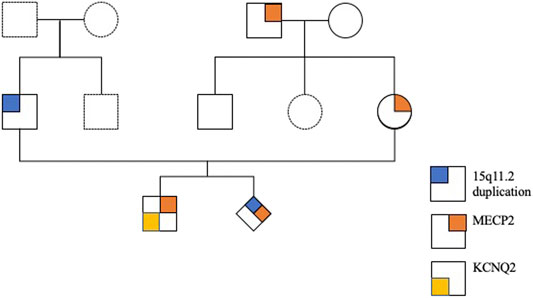

An East Asian family including a young healthy couple, their first son affected with KCNQ2-DEE, maternal grandparents, and uncle were enrolled in this study. The pedigree of this family is shown in Figure 1. Neither parent has a family history of epilepsy or developmental delays.

FIGURE 1. Pedigree of the family with a child with KCNQ2-developmental and epileptic encephalopathy (DEE).

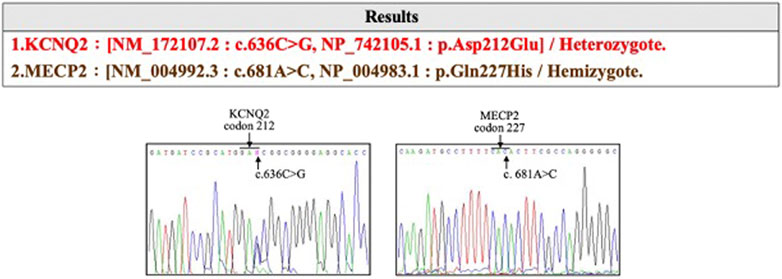

The affected son was born at 37 weeks of gestational age (GA) with a birth weight of 2,760 g and had an Apgar score of 9 and 10 at 1 and 5 min, respectively. He was delivered via cesarean section due to induction failure for maternal preeclampsia with severe features. Other than the acute onset of preeclampsia at GA = 36 weeks, prenatal examinations, including cytogenetic analysis and CMA, were negative. The delivery was uneventful, and newborn screening was normal. However, difficulty with nursing with a greater than 10% decrease in body weight was noted. On the third day after birth, an episode of generalized tonic–clonic seizure with desaturation occurred. Serum electrolytes, metabolites, and neurotransmitters were normal. Antiepileptic drugs, including levetiracetam and phenobarbital, were initiated in a stepwise manner. No structural abnormalities were observed on brain MRI. An electroencephalogram showed multifocal spikes with burst suppression. Trio WES of the son, mother, and father identified a novel de novo KCNQ2 missense variation (hg38 chr20 g.63444713G>C:NM_172107.2:exon4:c.636C>G:p.D212E) in the affected boy (Figure 2). The KCNQ2 variant was recognized as a disease-causative variant because a pathogenic variant causing the same amino acid change (hg38 chr20 g.63444713G>T:NM_004518.6:exon4:c.636C>A:p.D212E) has been reported in ClinVar database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/variation/205874/; accessed 10 July 2020). KCNQ2 is a gene related to autosomal dominant DEE (OMIM #613720), and KCNQ2-DEE was diagnosed to be consistent with the clinical presentation. At 34 months of age, the boy has presented with generalized tonic–clonic seizures, infantile spasm, and focal seizures. The condition of the affected son is currently under management with five antiepileptic drugs (lacosamide, oxcarbazepine, levetiracetam, vigabatrin, and topiramate). He is nonverbal and unable to roll, sit, crawl, and walk independently. He has hypotonic upper extremities and torso.

FIGURE 2. The KCNQ2 missense variation (hg38 chr20 g.63444713G>C:NM_172107.2:exon4:c.636C>G:p.D212E) identified in the affected devleopmental and epileptic encephalopathy (DEE) child.

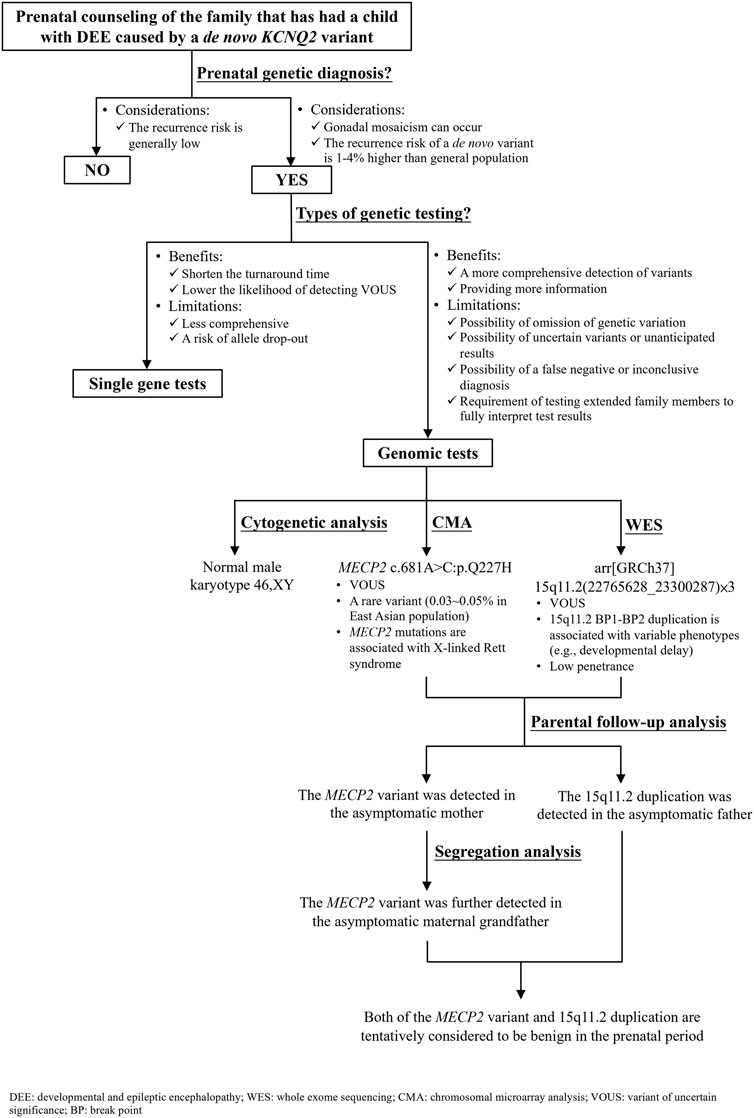

Parents of the affected boy visited our hospital (Linkou Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taiwan) for genetic counseling for their singleton, male pregnancy in 2020 due to the KCNQ2-DEE history of their first son. The pregnant woman underwent amniocentesis in the second trimester. Genetic analyses including cytogenetic analysis, WES, CMA, and segregation analysis were performed after genetic counseling (Figure 3). This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chang Gung Memorial Foundation (IRB No. 202001788B0). All individuals who participated in this study provided written informed consent and agreed to the publication of the results.

FIGURE 3. Flow diagram of the prenatal genetic counseling and genetic diagnosis for the family with KCNQ2-developmental and epileptic encephalopathy (DEE) history as well as the segregation analysis for determining the significance of a variant of uncertain significance.

DNA Extraction

DNA was extracted from amniocytes or peripheral blood cells using the Puregene Extraction Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). The values and ratio of absorbances at 260 and 280 nm were used to assess the DNA quality and purity with a ND-1000 photometer (Labtech International, Healthfield, East Sussex, UK).

Cytogenetic Analysis

Conventional cytogenetic G-banding analysis was performed on cultured amniocytes with Wright’s dye staining at the 550 bands of resolution, according to the standard cytogenetic protocol.

Whole-Exome Sequencing

Genomic DNA was fragmented using a model S220 sonicator (Covaris, Woburn, MA, USA) to obtain DNA fragments ranging in size from 200 to 500 bp. The fragmented DNA was ligated with sample-specific barcode sequences and a pair of universal tags (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) following PCR with eight cycles of amplification. The exonic regions of genomic DNA were enriched by hybridization with SureSelect Clinical Research v2 probes (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. After the non-captured intron/intergenic DNA was removed, the purified exonic DNA was subjected to next-generation sequencing using the Illumina NextSeq 500 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The sequencing amount for each DNA sample was estimated to be 10 to 12 giga base pairs. The average coverage depth of captured regions was set as >50-fold. Sequencing data were converted into the gzipped FASTA format and followed the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) best practice. The variations were called by a haplotype caller implemented in GATK 4 (version 4.1.4.1). The results of individual vcf files were merged by setting the trio proband–mother–father model and annotated utilizing resources from the University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC) (http://genome.ucsc.edu/), Ensembl (https://grch37.ensembl.org/index.html), dbNSFP (https://sites.google.com/site/jpopgen/dbNSFP), ClinVar (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/), Variant Effect Predictor (https://asia.ensembl.org/Homo_sapiens/Tools/VEP), 1000 Genomes Project (http://www.internationalgenome.org/), and the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD; http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/) to classify the type of variations, population frequencies, and potential impact on protein functions. The possible pathogenic variations detected in WES were validated by Sanger sequencing.

Chromosomal Microarray Analysis

CMA was performed using an oligonucleotide 8 × 60 K CytoScan gene chip (Agilent customer design ID 040427; Changhua Christian Hospital, Changhua, Taiwan). DNA labeling and hybridization were carried out according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The scanned images were analyzed using Feature Extraction 9.5.3 software (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The extracted data were processed using the Agilent Genomic Workbench 7.0 program (Agilent Technologies). The CMA findings were described based on the reference genome version of GRCh37.

Segregation Analysis

Segregation analysis was performed by PCR and direct sequencing and extended to relatives of the maternal lineages.

Results

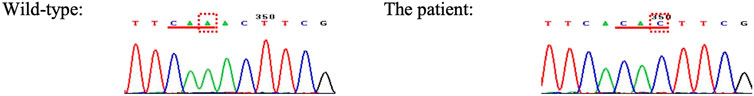

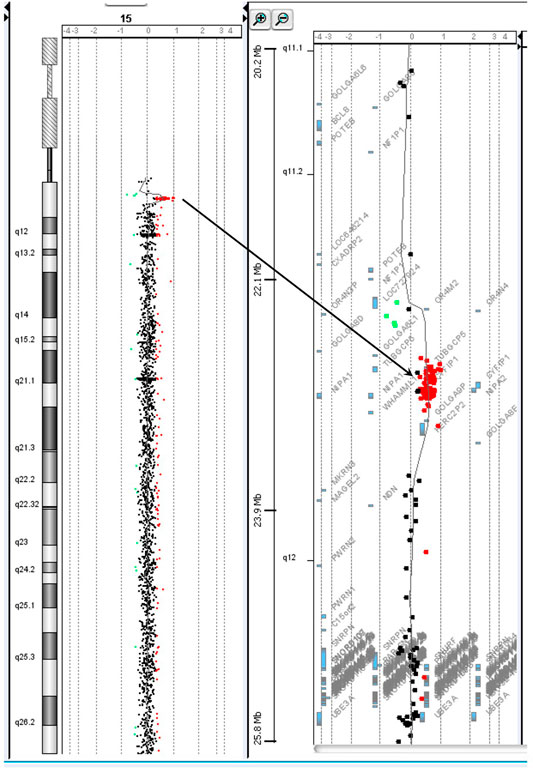

Chromosome analysis of amniocytes showed a normal male karyotype 46,XY. WES for the fetus excluded the existence of the KCNQ2 missense variant (c.636C>G:p.D212E) but incidentally identified a missense variant in MECP2 gene (hg38 chrX g.154031147T>G:NM_004992.3:exon4:c.681A>C:p.Q227H) (Figure 4). The MECP2 variant is a rare variant with a minor allele frequency of 0.03%–0.05% in the East Asian population (gnomAD; accessed Apr 27, 2020) and has not been reported in the ClinVar database (accessed Apr 27, 2020). Parental follow-up analysis showed that the MECP2 variant is of maternal origin. A retrospective review of the previous WES raw data found that the MECP2 variant was also presented in the affected son. The finding of the MECP2 variant was not shown in the WES report of the affected son because it was considered as a variant of uncertain significance (VOUS). Since variations in MECP2 gene have been associated with X-linked Rett syndrome (OMIM #312750), the clinical significance of the MECP2 variant (c.681A>C:p.Q227H) concerned the parents. An extended segregation analysis was recommended and performed for relatives of the maternal lineages, including the grandparents and uncle. The results showed the asymptomatic maternal grandfather also carried the same MECP2 variant. Moreover, CMA of the fetus further detected an approximately 0.53-Mb duplication in the 15q11.2 genomic region between the proximal 15q breakpoint 1 (BP1) and BP2 [arr(GRCh37)15q11.2(22765628_23300287) × 3], which contains four evolutionarily conserved and nonimprinted protein-coding genes: TUBGCP5, CYFIP1, NIPA1, and NIPA2. Parental analysis showed that the 15q11.2 duplication is of paternal origin (Figure 5). In utero brain MRI performed at GA = 26 weeks was negative for notable findings. The pregnancy was carried to term, and a 2,450-g male infant with Apgar scores of 9 and 10 at 1 and 5 min, respectively, was delivered via cesarean section. At the time of submission, the neonate is 15 months old with normal development.

FIGURE 4. The MECP2 missense variant incidentally identified in prenatal diagnosis by whole-exome sequencing is of maternal grandfather origin.

FIGURE 5. The chromosome 15q11.2 duplication incidentally identified in prenatal diagnosis by chromosomal microarray analysis is of paternal origin.

Discussion

DEE is a group of severe epilepsy disorders characterized by both intractable neonatal-onset seizures and profound global developmental delay. Developmental impairment and epileptic activity impact the cognitive and behavioral states of the affected person (Raga et al., 2021). Most DEE patients have a genetic etiology responsible for both cognitive impairment and severe epilepsy, and the control of seizures does not prevent cognitive impairment from worsening (Raga et al., 2021). A number of genes have been associated with DEE (Hamdan et al., 2017). Variants in KCNQ2 are among the most common genetic causes of DEE; the annual incidence of KCNQ2-DEE is estimated to be one per 17,000 live births (Symonds et al., 2019). KCNQ2 encodes the subunit Kv7.2 of neuronal voltage-gated potassium channels, which are broadly expressed in the brain, plasma membrane of axonal initial segments, and distal axons where action potential initiates and propagates. Currently, more than 200 variants in KCNQ2 have been recorded in The Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD) (http://www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk/; accessed September 1, 2021).

For the couple that has had a son affected with DEE caused by a de novo KCNQ2 variant (c.636C>G:p.D212E), prenatal genetic diagnosis is an option to reduce the chance of recurrence in the subsequent pregnancy. A nondirective pretest counseling was thus provided (Figure 3). The parents were concerned about de novo variants occurring prezygotically, preexisting in a parent of unrevealed mosaicism (Lynch, 2010; Eyal et al., 2019; Pasmant and Pacot, 2020). De novo prezygotic variants presenting in germ cells (gonadal mosaicism) can be transmitted to the next generation and cause diseases (Campbell et al., 2015; Eyal et al., 2019; Pasmant and Pacot, 2020). Recent studies have shown that the recurrence rate for a couple that has a child with a genetic disease caused by a de novo variant is 1%–4% higher than that of the general population (Campbell et al., 2014; Eyal et al., 2019). The benefits and limitations of single gene versus genomic tests were informed. The disadvantages of genomic tests include the omission of genetic variation due to inadequate coverage, the possibility of uncertain variants or unanticipated results, the possibility of a false-negative or inconclusive diagnosis, and the requirement of testing extended family members to fully interpret the test results were discussed (Zawati et al., 2014). The autonomy of the couple was respected when they decided to opt for genome-wide tests where WES was anticipated to cover the information of the KCNQ2 variant (c.636C>G:p.D212E) and CMA to rule out diseases caused by CNVs, such as Down syndrome and DiGeorge syndrome. The results showed incidental findings of a MECP2 missense variant and 15q11.2 microdeletion that were not related to the initial indication for the prenatal diagnostic test.

The MECP2 missense variant (c.681A>C:p.Q227H) detected in the male fetus is a rare and novel variant without known clinical significance. MECP2 is a gene encoding methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (MeCP2) essential for the normal function of nerve cells. Variants of MECP2 are responsible for 95% of cases of Rett syndrome, an X-linked dominant neurodevelopmental disorder with an incidence of one in 10,000 females (Shah and Bird, 2017; Gold et al., 2018). Females may be unaffected due to skewed X-inactivation or X-linked autosomal recessive inheritance (Tokaji et al., 2018; Pitzianti et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019). Rett syndrome was initially thought to be lethal in utero for males, but case studies with more severe symptoms that develop earlier in age have been reported in the literature. Other circumstances, such as Klinefelter syndrome and mosaicism, can also lead to males with Rett syndrome (Chahil et al., 2018). In this case, parental follow-up analysis showed that the MECP2 variant (c.681A>C:p.Q227H) was inherited from the unaffected, healthy mother. The effects of the MECP2 variant on the male fetus cannot be evaluated. A segregation analysis extending to the normal maternal grandparents and uncle was performed with the intent to involve extended relatives if the maternal grandmother was found to be a carrier. In the end, the maternal grandfather demonstrated to be a carrier but is asymptomatic (Figure 4). These results suggest that the MECP2 variant (c.681A>C:p.Q227H) does not correlate to abnormal phenotype and thus is likely a benign variant.

The 15q11.2 duplication detected in the fetus [arr(GRCh37)15q11.2(22765628_23300287) × 3] covers the 15q BP1–BP2 region and contains four genes (TUBGCP5, CYFIP1, NIPA1, and NIPA2). The 15q11.2 BP1–BP2 duplication has been reported to cause variable phenotypes including cognitive impairment, speech delay, and developmental delay (Burnside et al., 2011; Benitez-Burraco et al., 2017), as well as high inter-individual variability of neurodevelopmental disorders, such as schizophrenia (Kirov et al., 2012) and autism (Burnside et al., 2011). In addition, three of the four genes (CYFIP1, NIPA1, and NIPA2) have been shown to play a role in neurodevelopment and are associated with brain disorders (Goytain et al., 2008; van der Zwaag et al., 2010). Reports show the majority of the 15q11.2 BP1–BP2 duplication detected in affected children is transmitted from healthy parents. Furthermore, low penetrance was observed in case–control studies (e.g., 0.8% in Chaste et al., 2014). The 15q11.2 BP1–BP2 duplication is currently considered as a VOUS, and carrying the duplication increases the risk of clinical phenotypes. Prenatal prediction of the possible outcome of the 15q11.2 BP1–BP2 duplication based on the low penetrance and phenotypic variability is thus challenging. In this case, the risk of the 15q11.2 duplication was considered low because it was transmitted from the healthy father, and the follow-up ultrasounds and MRI were normal.

Prenatal counseling of genome-wide tests is challenging due to the complexity of genomic data, in which large numbers of genetic variants are VOUS whose significance to the function or health of people is unknown (Chen et al., 2020). The situation is further complicated by incidental (or secondary) findings not related to the indication or anticipation of the test. The debate regarding reporting of incidental findings not relevant to the perinatal outcome, such as variants associated with increased risk of cancer or disorders, continues (Dukhovny and Norton, 2018). Moreover, even when the genetic condition is known and is present in the same family, variable penetrance, expressivity, biological, and environmental factors can contribute to the differences in disease severity and outcome (Iafrate et al., 2004; Nowakowska, 2017). The limited understanding of the association between genotype and phenotype in many diseases may, at least partially, attribute to bias with the use of data from reference databases of symptomatic patients. Some genetic variations classified as pathogenic based on postnatal data may be polymorphic prenatally. The incomplete phenotype–genotype database of prenatal cases has limited the precise interpretation of variants (Aarabi et al., 2018).

In addition to the difficulty of prenatal interpretation of variants, different ethical issues have arisen over time with the prenatal use of genetic testing. One issue is eugenic counseling, which stresses the future of the gene pool by increasing desirable traits and preventing unwanted traits, emphasizing the prevention of birth of those with birth defects (Than and Papp, 2017). In addition, the evolution of precision medicine stems from the use of genetic testing to treat and improve the understanding of diseases at a biochemical or genetic level (Bailey et al., 2020). This extends to the use of prenatal genome editing, which is highly controversial. Although most people agree that prenatal genetic testing should balance the ethical principles of autonomy and distributive justice as newer and more advanced genome-wide tests become available, the equitable distribution of such tests is difficult due to their expense (Gekas et al., 2016; Dukhovny and Norton, 2018).

A perfectly healthy child is increasingly being demanded by modern society (Green, 2007). However, numerous genetic variations from CNVs to single-nucleotide variants have not been well studied. As such, expecting parents with fetuses of VOUS are faced with the difficult decision of whether to continue with the pregnancy and accept its risk. When a variant is detected, multifaceted support, including education of the significance of such findings, counseling, and meetings with specialists, may be warranted for the family to choose the best perinatal outcome for them. In addition, subsequent analysis of extended family members other than the parents may provide further insight, such as in our case. A thorough prenatal genetic counseling should include understanding the attitude of the family that can be affected by ethical and religious beliefs, education, socioeconomic conditions, and previous experience. It is essential to provide support and compassion to the family throughout the process.

Conclusion

Prenatal genetic diagnosis is an option for subsequent pregnancies of couples with a disabled child to reduce the chance of recurrence. Genome-wide tests that provide a more comprehensive detection of variants are gaining popularity for prenatal diagnosis. However, this is associated with the detection of incidental findings and VOUS. Consequently, genetic counseling of genomic tests can be challenging, requiring adequate informed consent, such as discussion of the potential to identify additional findings, findings of uncertain significance, the possibility for additional testing of extended family members to fully interpret test results, and ethical issues.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chang Gung Memorial Foundation (IRB No. 202001788B0). Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

MC and SWS led this work and provided genetic counseling. T-XH and WFL prepared the original draft. G-CM performed the laboratory work and revised the manuscript. All authors agree to be accountable for the content of the work.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the staff of the Department of Genomic Medicine, Changhua; Changhua Christian Hospital and the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Taipei; and Taipei Chang Gung Memorial Hospital for their technical assistance in genetic testing.

References

Aarabi, M., Sniezek, O., Jiang, H., Saller, D. N., Bellissimo, D., Yatsenko, S. A., et al. (2018). Importance of Complete Phenotyping in Prenatal Whole Exome Sequencing. Hum. Genet. 137 (2), 175–181. doi:10.1007/s00439-017-1860-1

Baenziger, J., Roser, K., Mader, L., Harju, E., Ansari, M., Waespe, N., et al. (2020). Post-traumatic Stress in Parents of Long-Term Childhood Cancer Survivors Compared to Parents of the Swiss General Population. J. Psychosoc Oncol. Res. Pract. 2 (3), e024. doi:10.1097/OR9.0000000000000024

Bailey, J. N. C., Bush, W. S., and Crawford, D. C. (2020). Editorial: The Importance of Diversity in Precision Medicine Research. Front. Genet. 11, 875. doi:10.3389/fgene.2020.00875

Benítez-Burraco, A., Barcos-Martínez, M., Espejo-Portero, I., and Jiménez-Romero, S. (2017). Variable Penetrance of the 15q11.2 BP1-BP2 Microduplication in a Family with Cognitive and Language Impairment. Mol. Syndromol 8 (3), 139–147. doi:10.1159/000468192

Burnside, R. D., Pasion, R., Mikhail, F. M., Carroll, A. J., Robin, N. H., Youngs, E. L., et al. (2011). Microdeletion/microduplication of Proximal 15q11.2 between BP1 and BP2: a Susceptibility Region for Neurological Dysfunction Including Developmental and Language Delay. Hum. Genet. 130 (4), 517–528. doi:10.1007/s00439-011-0970-4

Campbell, I. M., Shaw, C. A., Stankiewicz, P., and Lupski, J. R. (2015). Somatic Mosaicism: Implications for Disease and Transmission Genetics. Trends Genet. 31 (7), 382–392. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2015.03.013

Campbell, I. M., Stewart, J. R., James, R. A., Lupski, J. R., Stankiewicz, P., Olofsson, P., et al. (2014). Parent of Origin, Mosaicism, and Recurrence Risk: Probabilistic Modeling Explains the Broken Symmetry of Transmission Genetics. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 95, 345–359. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.08.010

Ceylan, A. C., Citli, S., Erdem, H. B., Sahin, I., Acar Arslan, E., and Erdogan, M. (2018). Importance and Usage of Chromosomal Microarray Analysis in Diagnosing Intellectual Disability, Global Developmental Delay, and Autism; and Discovering New Loci for These Disorders. Mol. Cytogenet. 11, 54. doi:10.1186/s13039-018-0402-4

Chahil, G., Yelam, A., and Bollu, P. C. (2018). Rett Syndrome in Males: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Cureus 10 (10), e3414. doi:10.7759/cureus.3414

Chang, T.-Y., Chung, I.-F., Wu, W.-J., Chang, S.-P., Lin, W.-H., Ginsberg, N. A., et al. (2020). Whole Exome Sequencing with Comprehensive Gene Set Analysis Identified a Biparental-Origin Homozygous c.509G>A Mutation in PPIB Gene Clustered in Two Taiwanese Families Exhibiting Fetal Skeletal Dysplasia during Prenatal Ultrasound. Diagnostics 10 (5), 286. doi:10.3390/diagnostics10050286

Chaste, P., Sanders, S. J., Mohan, K. N., Klei, L., Song, Y., Murtha, M. T., et al. (2014). Modest Impact on Risk for Autism Spectrum Disorder of Rare Copy Number Variants at 15q11.2, Specifically Breakpoints 1 to 2. Autism Res. 7 (3), 355–362. doi:10.1002/aur.1378

Chen, M., Wu, W.-J., Lee, M.-H., Ku, T.-H., and Ma, G.-C. (2020). Relevance of Copy Number Variation at Chromosome X in Male Fetuses Inherited from the Mother May Be Ascertained by Including Male Relatives from the Maternal Lineage in Addition to Trio Analyses. Genes 11 (9), 979. doi:10.3390/genes11090979

Dukhovny, S., and Norton, M. E. (2018). What Are the Goals of Prenatal Genetic Testing? Semin. Perinatology 42 (5), 270–274. doi:10.1053/j.semperi.2018.07.002

Eyal, O., Berkenstadt, M., Reznik‐Wolf, H., Poran, H., Ziv‐Baran, T., Greenbaum, L., et al. (2019). Prenatal Diagnosis for De Novo Mutations: Experience from a Tertiary center over a 10‐year Period. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 7 (4), e00573. doi:10.1002/mgg3.573

Gekas, J., Langlois, S., Ravitsky, V., Audibert, F., van den Berg, D., Haidar, H., et al. (2016). Non-invasive Prenatal Testing for Fetal Chromosome Abnormalities: Review of Clinical and Ethical Issues. Tacg 9, 15–26. doi:10.2147/TACG.S85361

Gold, W. A., Krishnarajy, R., Ellaway, C., and Christodoulou, J. (2018). Rett Syndrome: A Genetic Update and Clinical Review Focusing on Comorbidities. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 9 (2), 167–176. doi:10.1021/acschemneuro.7b00346

Goytain, A., Hines, R. M., and Quamme, G. A. (2008). Functional Characterization of NIPA2, a Selective Mg2+ Transporter. Am. J. Physiology-Cell Physiol. 295 (4), C944–C953. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00091.2008

Hall, H. R., Neely-Barnes, S. L., Graff, J. C., Krcek, T. E., Roberts, R. J., and Hankins, J. S. (2012). Parental Stress in Families of Children with a Genetic Disorder/disability and the Resiliency Model of Family Stress, Adjustment, and Adaptation. Issues Compr. Pediatr. Nurs. 35 (1), 24–44. doi:10.3109/01460862.2012.646479

Hamdan, F. F., Myers, C. T., Cossette, P., Lemay, P., Spiegelman, D., Laporte, A. D., et al. (2017). High Rate of Recurrent De Novo Mutations in Developmental and Epileptic Encephalopathies. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 101 (5), 664–685. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.09.008

Iafrate, A. J., Feuk, L., Rivera, M. N., Listewnik, M. L., Donahoe, P. K., Qi, Y., et al. (2004). Detection of Large-Scale Variation in the Human Genome. Nat. Genet. 36 (9), 949–951. doi:10.1038/ng1416

Jelin, A. C., and Vora, N. (2018). Whole Exome Sequencing. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. North America 45 (1), 69–81. doi:10.1016/j.ogc.2017.10.003

Kirov, G., Pocklington, A. J., Holmans, P., Ivanov, D., Ikeda, M., Ruderfer, D., et al. (2012). De Novo CNV Analysis Implicates Specific Abnormalities of Postsynaptic Signalling Complexes in the Pathogenesis of Schizophrenia. Mol. Psychiatry 17 (2), 142–153. doi:10.1038/mp.2011.154

Lynch, M. (2010). Rate, Molecular Spectrum, and Consequences of Human Mutation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107 (3), 961–968. doi:10.1073/pnas.0912629107

Nowakowska, B. (2017). Clinical Interpretation of Copy Number Variants in the Human Genome. J. Appl. Genet. 58 (4), 449–457. doi:10.1007/s13353-017-0407-4

Pasmant, E., and Pacot, L. (2020). Should We Genotype the Sperm of Fathers from Patients with 'De Novo' Mutations? Eur. J. Endocrinol. 182 (1), C1–C3. doi:10.1530/EJE-19-0759

Pitzianti, M. B., Santamaria Palombo, A., Esposito, S., and Pasini, A. (2019). Rett Syndrome in Males: The Different Clinical Course in Two Brothers with the Same Microduplication MECP2 Xq28. Ijerph 16 (17), 3075. doi:10.3390/ijerph16173075

Raga, S., Specchio, N., Rheims, S., and Wilmshurst, J. M. (2021). Developmental and Epileptic Encephalopathies: Recognition and Approaches to Care. Epileptic Disord. 23 (1), 40–52. doi:10.1684/epd.2021.1244

Schmidt, J. L., Maas, R., and Altmeyer, S. R. (2019). Genetic Counseling for Consumer‐driven Whole Exome and Whole Genome Sequencing: A Commentary on Early Experiences. J. Genet. Couns. 28 (2), 449–455. doi:10.1002/jgc4.1109

Shah, R. R., and Bird, A. P. (2017). MeCP2 Mutations: Progress towards Understanding and Treating Rett Syndrome. Genome Med. 9 (1), 17. doi:10.1186/s13073-017-0411-7

Symonds, J. D., Zuberi, S. M., Stewart, K., McLellan, A., O‘Regan, M., MacLeod, S., et al. (2019). Incidence and Phenotypes of Childhood-Onset Genetic Epilepsies: a Prospective Population-Based National Cohort. Brain 142 (8), 2303–2318. doi:10.1093/brain/awz195

Than, N. G., and Papp, Z. (2017). Ethical Issues in Genetic Counseling. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 43, 32–49. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2017.01.005

Tokaji, N., Ito, H., Kohmoto, T., Naruto, T., Takahashi, R., Goji, A., et al. (2018). A rare male patient with classic Rett syndrome caused by MeCP2_e1 mutation. Am. J. Med. Genet. 176 (3), 699–702. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.38595

van der Zwaag, B., Staal, W. G., Hochstenbach, R., Poot, M., Spierenburg, H. A., de Jonge, M. V., et al. (2009). A Co-segregating Microduplication of Chromosome 15q11.2 Pinpoints Two Risk Genes for Autism Spectrum Disorder. Am. J. Med. Genet. 9999B (4), a–n. doi:10.1002/ajmg.b.31055

Warmerdam, J., Zabih, V., Kurdyak, P., Sutradhar, R., Nathan, P. C., and Gupta, S. (2019). Prevalence of Anxiety, Depression, and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Parents of Children with Cancer: A Meta‐analysis. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 66 (6), e27677. doi:10.1002/pbc.27677

Zawati, M. N. H., Parry, D., Thorogood, A., Nguyen, M. T., Boycott, K. M., Rosenblatt, D., et al. (2014). Reporting Results from Whole-Genome and Whole-Exome Sequencing in Clinical Practice: a Proposal for Canada? J. Med. Genet. 51 (1), 68–70. doi:10.1136/jmedgenet-2013-101934

Keywords: prenatal diagnosis, prenatal counseling, whole exome sequencing, chromosome microarray analysis, de novo variant, KCNQ2-DEE, MECP2, 15q11.2 microduplication

Citation: Huang T-X, Ma G-C, Chen M, Li W-F and Shaw SW (2021) Difficulties of Prenatal Genetic Counseling for a Subsequent Child in a Family With Multiple Genetic Variations. Front. Genet. 12:612100. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2021.612100

Received: 30 September 2020; Accepted: 15 November 2021;

Published: 14 December 2021.

Edited by:

Reza Azizi Malamiri, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, IranReviewed by:

Elizabeth Emma Palmer, University of New South Wales, AustraliaRamshekhar Menon, Sree Chitra Tirunal Institute for Medical Sciences and Technology (SCTIMST), India

Copyright © 2021 Huang, Ma, Chen, Li and Shaw. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Steven W. Shaw, ZHIuc2hhd0BtZS5jb20=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Ting-Xuan Huang

Ting-Xuan Huang Gwo-Chin Ma

Gwo-Chin Ma Ming Chen2,3,4,5,6,7

Ming Chen2,3,4,5,6,7 Wen-Fang Li

Wen-Fang Li Steven W. Shaw

Steven W. Shaw