95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Front. Genet. , 21 December 2020

Sec. Livestock Genomics

Volume 11 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2020.582355

The acute thermal response has been extensively studied in commercial chickens because of the adverse effects of heat stress on poultry production worldwide. Here, we performed whole-genome resequencing of autochthonous Niya chicken breed native to the Taklimakan Desert region as well as of 11 native chicken breeds that are widely distributed and reared under native humid and temperate areas. We used combined statistical analysis to search for putative genes that might be related to the adaptation of hot arid and harsh environment in Niya chickens. We obtained a list of intersected candidate genes with log2 θπ ratio, FST and XP-CLR (including 123 regions of 21 chromosomes with the average length of 54.4 kb) involved in different molecular processes and pathways implied complex genetic mechanisms of adaptation of native chickens to hot arid and harsh environments. We identified several selective regions containing genes that were associated with the circulatory system and blood vessel development (BVES, SMYD1, IL18, PDGFRA, NRP1, and CORIN), related to central nervous system development (SIM2 and NALCN), related to apoptosis (CLPTM1L, APP, CRADD, and PARK2) responded to stimuli (AHR, ESRRG FAS, and UBE4B) and involved in fatty acid metabolism (FABP1). Our findings provided the genomic evidence of the complex genetic mechanisms of adaptation to hot arid and harsh environments in chickens. These results may improve our understanding of thermal, drought, and harsh environment acclimation in chickens and may serve as a valuable resource for developing new biotechnological tools to breed stress-tolerant chicken lines and or breeds in the future.

Domestic chickens (Gallus gallus domesticus) were most likely domesticated from wild Red Jungle Fowls (Miao et al., 2013; Wang M.-S. et al., 2020) and became the most abundant domestic animals all over the world (Lawler, 2014). After a long period of artificial and natural selection, over hundreds of distinct chicken breeds exist and thrive, and which could be raised in various geographical environments. Furthermore, considering the characteristics of short reproductive and growth periods and large clutch sizes, chickens can be used as ideal models to study genetic adaptations to environments. The chicken genome has been de novo assembled (Hillier et al., 2004; Warren et al., 2017) which allowed us to access whole-genome information to detect the genetic signatures of selection left in the genome.

Due to the effects of common global environmental stressors (e.g., heat stress) on poultry production, it is important to improve our understanding of the genetic mechanisms associated with the negative effects of stressful environments and conditions. Although the acute heat response has been extensively studied in commercial chickens because of the adverse effects of heat stress on poultry production worldwide (Nawab et al., 2018) and some studies have been done to exam the environmental adaptability of native chickens (Elbeltagy et al., 2019; Walugembe et al., 2019; Wang Q. et al., 2020), there are short of reports on the genetic mechanisms of domestic chickens adapting to naturally occurring hot arid and harsh environments with multiple stressors (e.g., heat stress, drought, and other adverse stimuli) in China.

The Niya chicken (NY) is a native Chinese chicken breed that originated from the northwest region of the Tarim Basin, the southern margin of the Taklimakan Desert. The living environment of NY belongs to the temperate desert climate zone with high solar radiation, huge diurnal ambient temperature difference, high daytime temperatures, frequent floating dust weather (>220 days/year), extremely low rainfall (30.2 mm/year), and high evaporation (2756.1–2,824 mm/year). While NYs have always been raised like free-range chickens outside by local people, they have encountered more drought and harsher conditions than their counterparts (Table 1) living in humid and temperate areas.

To investigate putative genomic regions related to adaptation to hot arid and harsh environments in native chickens, we performed whole-genome resequencing of NYs together with other indigenous chickens belonging to 11 native chicken breeds that are widely distributed and reared in native humid and temperate areas across China. All Chinese indigenous chickens used in this study were dual-purpose types and has been suggested derived from the G. gallus spadiceus (Wang M.-S. et al., 2020). We combined several statistical approaches (Fst and θπ ratio, XP-CLR and ΔAF) to increase the statistical power to detect selection signatures in NYs. We focused on the main environmental factor (annual precipitation) to distinguish NYs and Others. Though other environmental factors do exists, but that was vague to distinguish NYs and Others from them. Our findings could broaden our understanding of thermal, drought, and harsh environment acclimation in chicken genomes and may serve as a valuable resource for developing new biotechnological tools to breed stress-tolerant chicken lines or breeds in the future. It is worth noting that the genomic differences between NYs and Others may not only be due to climate adaptation since other influence factors may exist due to the study design.

The study was approved by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of Hunan Agricultural University. We performed the whole-genome resequencing of 15 unrelated NYs native to hot arid and harsh habitat. We also sequenced the whole genomes of 15 other indigenous chickens belonging to 11 native chicken breeds that are widely distributed and reared in native humid and temperate areas across China. Genomic DNA was extracted from venous blood of wing samples and muscle samples using the phenol-chloroform method. Sequencing libraries were generated using the Truseq Nano DNA HT Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina, USA). Whole genomes of 30 chickens were sequenced on the Illumina Hiseq 2500 platform for 150 bp paired-end reads on fast mode with two lines. Moreover, we downloaded the resequencing data of five Red Jungle Fowls (RJFs) (PRJNA241474) from NCBI.

To ensure that reads were reliable and without artificial bias (low quality paired reads, which mainly resulted from base-calling duplicates and adapter contamination) in the following analyses, raw reads of fastq format were first processed through a series of quality control (QC) procedures using FastQC (Version 0.11.9). QC standards are as follows: (1) Removing reads with ≥10% unidentified nucleotides (N); (2) Removing reads with > 20% bases having Phred quality <5; (3) Removing reads with > 10 nt aligned to the adapter, allowing ≤ 10% mismatches; (4) Removing putative PCR duplicates generated by PCR amplification in the library construction process (read 1 and 2 of two paired-end reads that were completely identical).

The clean paired-end reads were aligned to the chicken reference genome (Galgal5) using Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (Version: 0.7.8) (settings: mem -t 8 -k 32–M -R). BAM alignment files were then generated using SAMtools (v.1.3) (Li et al., 2009). Additionally, we improved the alignment performance through the following steps: (1) filtering the alignment reads with mismatches ≤5 and mapping quality = 0, and (2) removing potential PCR duplication. If multiple read pairs had identical external coordinates, only the pair with the highest mapping quality was retained.

We further performed SNP calling on a population scale using the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK, version v3.6) with the HaplotypeCaller-based method. Before calling variants, the base quality scores were recalibrated using GATK, which provides empirically accurate base quality scores for each base in every read. After SNP calling, we applied variant quality recalibration to exclude potential false-positive variant calls. We used the command “Variant Filtration –filterExpression” with the following parameters: QD < 10.0; FS > 60.0; MQ < 40.0; ReadPosRankSum < −8.0; and -G_filter “GQ<20”. SNPs were annotated by ANNOVAR using Galgal5 database.

Considering that all the selected samples are from the G. gallus, the data are relatively similar and meet the conditions of superposition. An individual-based neighbor-joining tree was constructed based on the p-distance using TreeBestv1.9.2 software. We conducted principal component analysis (PCA) to evaluate genetic structure using GCTA software. The significance level of the eigenvector was determined using the Tracey-Widom test. The population genetic structure was examined via an expectation maximization algorithm, as implemented in the program FRAPPEv1.170. The number of assumed genetic clusters K ranged from 2 to 6, with 10,000 iterations for each run. Ancestral model-based clustering, with no prior knowledge on breed origins, was performed using ADMIXTURE 1.2.2 (Alexander et al., 2009) to investigate individual admixture proportions, for 1<k<10, where k is the number of expected subpopulations, and the best k = 2 was determined based on the cross-validation error for different numbers of ancestral genetic backgrounds.

We applied a sliding-window approach (40 kb windows sliding in 20 kb steps) according to Rubin et al. (2010) to quantify polymorphism levels (θπ, pairwise nucleotide variations as a measure of variability and genetic differentiation FST for NYs and Others, including LS, QY, HT, EM, XJ, TY, P1, P2, P3, QX which were breeds native to humid areas across China with average annual precipitation >1,200 mm). We calculated the θπ ratios based on the θπ values of the two populations and then log2-transformed the data. We considered the windows with the top 5% FST and log2 (θπ ratio) simultaneously as candidate outliers under strong selective sweeps in NYs. Furthermore, we estimated the XP-CLR statistic (Chen et al., 2010) between NY and Others. The threshold for candidate genes in the XP-CLR analyses was set to the top 1% percentile outliers. All outlier windows were assigned to corresponding SNPs and genes. Functional enrichment was performed for candidate genes using DAVID 6.8 (Huang et al., 2009).

Allele frequency in a population is the number of individuals with a given genotype divided by the total number of individuals in the population (Brooker et al., 2011). The major of NY genotype was used as a reference, and the per genotype absolute allele frequency difference (ΔAF) between NYs and Others was then calculated with Perl script using the formula: ΔAF = abs (AFNYs – AFOthers).

We sequenced 30 chickens (Supplementary Figure 1, Supplementary Table 1) to an average genome mapping rate of 99.05% with ~11.76-fold average depth (Supplementary Table 2). We identified 161,322 SNPs located within the coding region of the chicken genome, including 46,063 non-synonymous SNPs, 355 stop gain, 89 stop loss and 114,815 synonymous SNPs (Supplementary Table 3). Approximately 5.50 M SNPs were detected in each native chicken individual, and an average of 93.27% (range: 89.68–95.39%) of the SNPs were validated in the chicken dbSNP (Build 151) database (Supplementary Table 4), indicating the high reliability of the called SNP variations in this study.

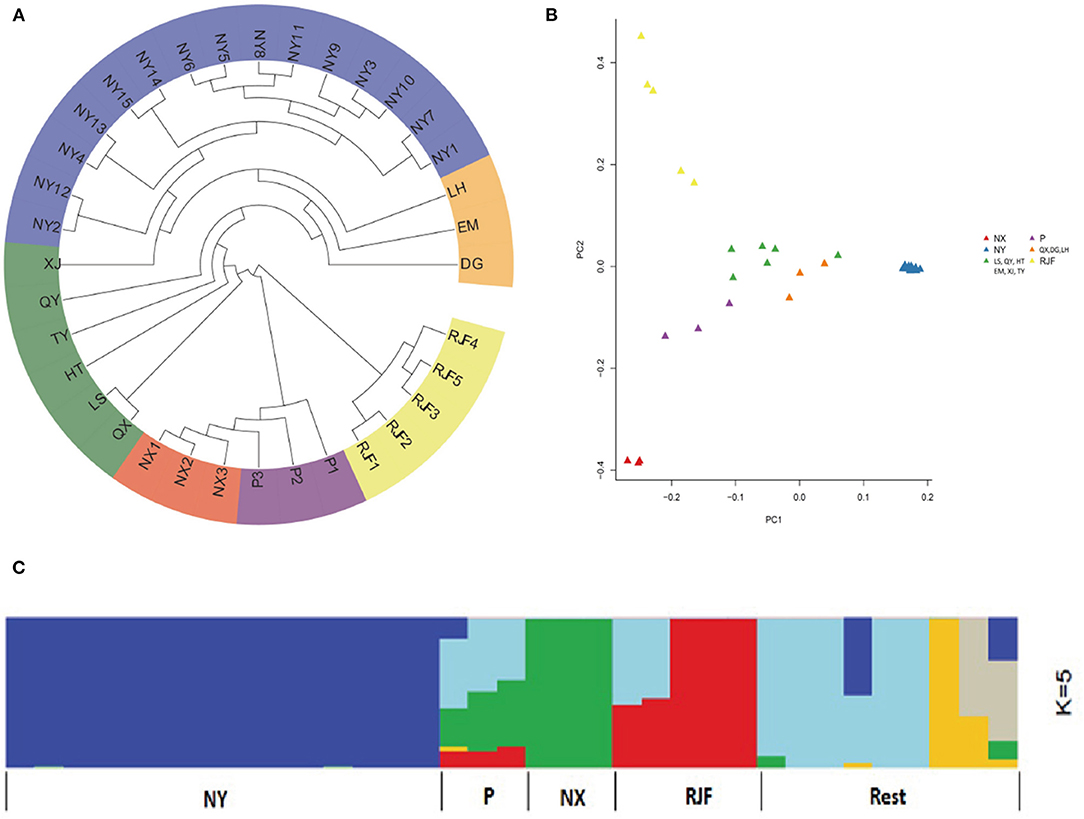

To investigate the genetic relationships between NYs and other native chicken breeds, we constructed a phylogenetic tree using the neighbor-joining method. From the phylogenic tree, the RJF formed a root clade that was separated from other domesticated chicken breeds (Figure 1A). Six individuals belonging to two chicken breeds (NX and P) first separated and NYs with the rest chickens formed a subcluster. The PCA analysis distinguished NY from other chickens and RJFs (Figure 1B). In particular, the first eigenvector PC1 separated NYs from others, explaining 8.24% of the overall variation, and the second eigenvector PC2 distinguished NXs and RJFs, explaining 5.15% of the overall variation (Supplementary Table 5). We further performed population admixture analysis to examine the possible population ancestry and structure of NYs. When the pre-defined genetic cluster K was set to 2, we found that other native breeds together with RJFs were separated from NY chickens. When K was set to 3, other breeds (P, NX and rest samples) were further separated from RJF. When K was set to 4, RJFs were divided into two lineages, as reported previously (Wang et al., 2015), and more additional lineages of other breeds were found, indicating the possible admixture among native breeds. Notably, however, at all settings of K (2–5) in this study, NYs were remain separated from other local breeds, implying possible isolation with other indigenous chicken breeds during the breeding history of NY (Figure 1C).

Figure 1. Population genetics analyses of 35 chickens. (A) Neighbor-joining tree constructed using p-distances between individuals. (B) Principal component analysis (PCA) of 35 chickens. (C) Genetic structure of chicken breeds. The length of each colored segment represents the proportion of the individual's genome from ancestral populations (k = 5). The population names are at the bottom of the figure. Dagu (DG), Emei Black (EM), Hetian (HT), Luhua (LH), Longsheng (LS), Nixi (NX), Niya (NY), Piao (P), Qianxiang (QX), Qingyuan (QY), Taoyuan (TY), Xianju (XJ), and Red jungle fowl (RJF).

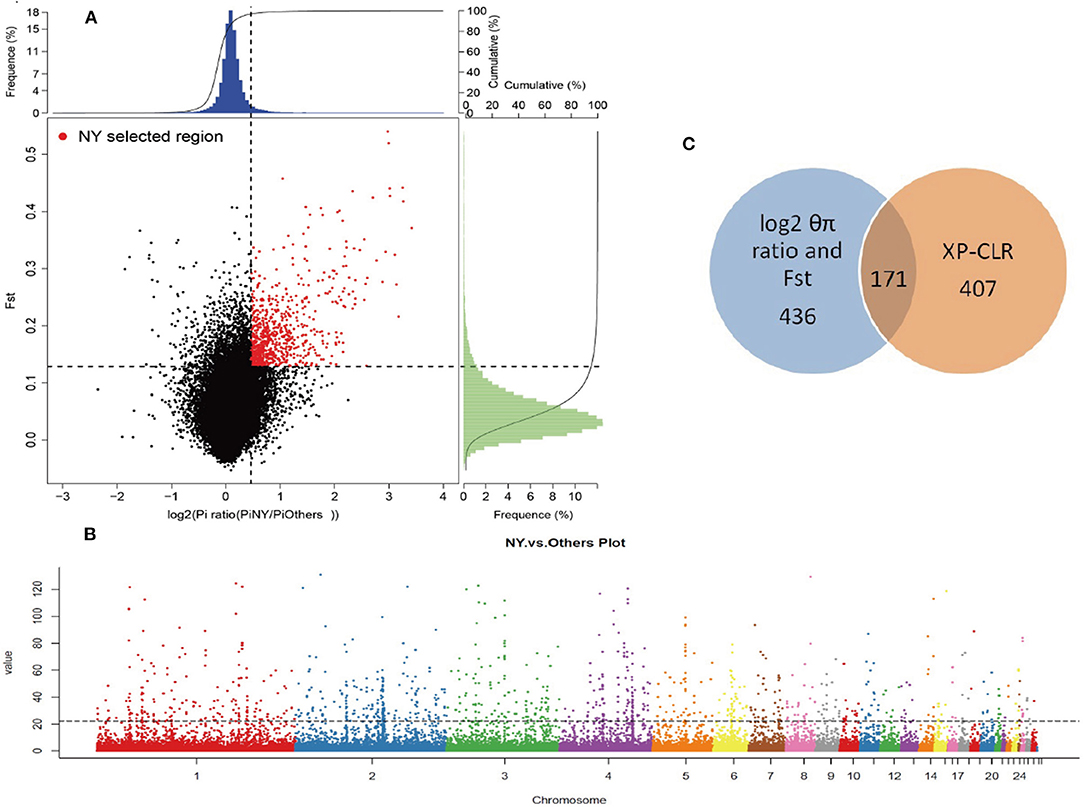

To reliably detect the genomic footprints left by selection pressures related to adaptation to hot, dry, and harsh environments in NYs and reduce the impact of genetic divergence that results from the domestication process, we measured pairwise comparisons of genome-wide variations and compared NYs with a domesticated diverse local chicken panel (Others) (Supplementary Table 6). We used an empirical procedure and selected regions simultaneously with significantly higher log2 (θπ ratio [θπ, Others/θπ, NYs]) (top 5% outliers, log2 [θπ ratio] > 0.46) and FST values (top 5% outliers, FST > 0.13) as candidate regions with strong selective sweep signals along the genome (except for the sex chromosome) (Figure 2A). We identified a total of 32.4 Mb genomic regions (3.07% of the genome, containing 436 genes, 24 chromosomes, the average length is 67.2 kb) with strong selective sweep signals in NYs (Supplementary Tables 7, 8).

Figure 2. Genomic regions with strong selective sweep signals in NYs. (A) Distribution of log2 (θπ ratio [θπ, Others / θπ, NYs]) (top 5% outliers, log2 [θπ ratio] > 0.46) and FST values (top 5% outliers, FST > 0.13), which are calculated in 40 kb windows sliding in 20 kb steps. The selected regions for NYs were indicated by red dots. (B) The Manhattan plot shown candidate genes positively selected in XP-CLR method between NYs and Others. The dotted line indicates the top 1% threshold. The data points above the straight line (corresponding to the top 1% of empirical values) are genomic regions under selection in NYs. (C) A total of 171 candidate genes in NYs were identified by combining three methods (including log2 [θπ ratio], FST and XP-CLR) simultaneously and are shown using Venn diagram components.

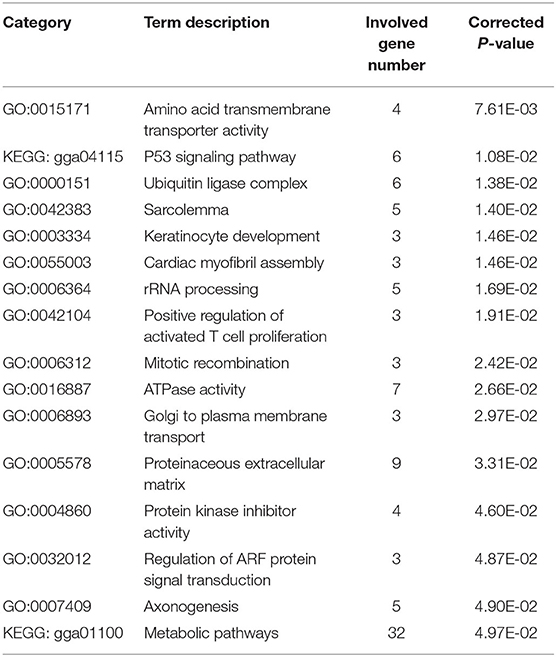

We also ran a composite likelihood ratio test (XP-CLR) between the two populations (NYs and Others) to search for the selective sweeps. We divided the whole genome area into non-overlapping windows of 10 kb. The genomic windows with XP-CLR scores greater than a threshold of 22.85 (top 1% outliers) were putative selected regions. We identified a total of 8.67 Mb genomic regions (0.81% of the genome, containing 407 genes, 26 chromosomes, the average length is 24.9 kb) with strong selective sweep signals in NYs (Figure 2B, Supplementary Tables 9, 10). The combination of different statistical analysis results would provide more powerful information than a single test result. Thus, we obtained 672 putative genes (Supplementary Table 11) in the union of log2 θπ ratio, FST and XP-CLR after removed the duplicates and 171 genes intersected with three statistics (Figure 2C, Supplementary Table 12). These overlapped putative genes were significantly functionally enriched in p53 signaling, metabolic pathway and 14 GO terms (corrected P-value < 0.05) which may play important roles in hot arid adaptation (such as the NRP1 and PARK2) in NYs (Table 2). The functional analysis of candidate genes using David for the gene list results from each of the statistical analyses was showed in Supplementary Tables 13, 14.

Table 2. Enriched genes associated with adaptation to hot arid and harsh environment in NYs (top list, corrected P-value ≤ 0.05).

We used combined statistical analysis to search for putative genes that might be related to the adaptation of hot arid and harsh environment in NYs. We obtained a list of intersected candidate genes with three statistical analyses (including 123 regions of 21 chromosomes with the average length of 54.4kb) (Supplementary Table 10) involved in different molecular processes and pathways implied complex genetic mechanisms of adaptation of native chickens to hot arid and harsh environments.

The living environment of NYs is characterized by huge diurnal ambient temperature differences caused by intense solar radiation, resulting in high temperatures during the day. Chickens use a variety of methods to maintain core body temperature and internal homeostasis (Lara and Rostagno, 2013), including increased radiation, convective, and evaporative heat loss through the diastolic blood vessels (Mutaf et al., 2009). By reducing blood flow bypassing internal organs, more blood flows to naked surface tissues, such as combs (Wolfenson et al., 1981) and bare feet (Hillman et al., 1982), to dissipate excessive heat. Additionally, as a true panting animal, chickens can expel internal heat by evaporating moisture through the lungs and air sacs, which are richer in blood vessels (Collier and Gebremedhin, 2015).

In NYs, we found several genes that were related to circulatory and cardiovascular system development, blood vessel development, and heart development. For example, BVES is known as a caveolae-associated protein important for the preservation of caveolae structural and functional integrity and heart protection (Alcalay et al., 2013). It also plays a role in the regulation of heart rate (Froese et al., 2012), response to ischemia (Alcalay et al., 2013), and heart development (Torlopp et al., 2006). SMYD1 is essential for cardiomyocyte differentiation and cardiac morphogenesis (Phan et al., 2005) and involved in angiogenesis (Ye et al., 2016). PDGFRA plays the role of the receptor and the ligands in chicken cardiac development (Bax et al., 2009). IL18 is a kind of cytokine with multiple proinflammatory effects and is suggested to be a novel angiogenic mediator (Park et al., 2001). NRP1 encodes neuropilin 1, a type of VEGF receptor, and has been well-studied with known functions in angiogenesis (Gelfand et al., 2014), cardiovascular system development (Ruhrberg et al., 2009), the formation of certain neural circuits (Schwarz et al., 2008), and the development in other organs other than nervous system organs (Ng et al., 2001). And selective signals of IL18 and NRP1 were just consistent with the adaptation studies in East-African vs. North-African chickens (Elbeltagy et al., 2019). Interestingly, in NY populations, we found high ΔAF (ΔAF > 0.7) only presented in 18 intronic SNPs of CORIN compared with other domestic chickens. CORIN is a heart hormone that regulates blood pressure and volume in humans (Chen et al., 2015) and could be functionally important for the maintenance of the proper volume of blood fluids in NYs due to adapt to hot arid environments. Therefore, we assumed that selected genes involved in the circulatory system and vasculature development reflect the crucial role of thermoregulation in adaptation to hot arid environments in NYs.

In the selected genes, we identified genes related to central nervous system development including dendrite development, neuron migration, neuron differentiation, and brain development. For example, SIM2 is a major regulator of neurogenesis (Moffett et al., 1997). NALCN regulates sodium leakage conductance responsible for the neuronal background. Many studies in humans and mice have shown alterations, retardation, and deleterious effects in the central nervous system due to adaptation to thermal environments (Ahmed, 2005). Therefore, we supposed that the selective signals of genes related to central nervous system development in NYs may be the result of adaptation to the hot arid environment.

Apoptosis refers to a stable and highly regulated cell death process controlled by multiple genes and has functions to maintain the stability of the internal environment in living organisms. Also, it permits adaptation to the existing environment (Elmore, 2007). We found abundant apoptosis-related genes in the selective regions. For example, CLPTM1L encodes a membrane protein associated with apoptosis induced by cisplatin. In particular, we found an abundance of genes with functions related to cell differentiation and apoptosis in neural cells, such as APP, CRADD and PARK2. And studies of Elbeltagy et al. (2002) reported that PAPK7 were located at the ROH region of North African Chicken populations (Elbeltagy et al., 2019). Studies have shown the heat-induced apoptosis mainly manifests as central nervous system damage and can cause cellular injury in the liver, heart, and kidneys of humans and mice (Edwards et al., 1997; Bongiovanni et al., 1999). Hence, we speculated that the set of genes involved in apoptosis, particularly induction of neural cell death, may provide evidence of the adaptation of NYs to the hot arid environment.

The living environments of NYs are highly stressful (e.g., thermal stress, arid and sandy wind, and solar radiation). To maintain homeostasis and thermoregulation, chickens can use various physiological activities to respond to such external stimuli. We found that selected genes were associated with response to hormones, endogenous stimuli, and external stimuli. Notably, the AHR gene encodes aryl hydrocarbon receptor, a ligand-activated transcription factor that is highly conserved in different species and is involved in eliminating various environmental toxins, mediating immune defenses, and regulating metabolism and cellular stress (Moura-Alves et al., 2014). ESRRG is a steroid hormone receptor and plays a critical role in thermogenesis (Ahmadian et al., 2018). Moreover, FAS and IL18 play important roles in immune and inflammatory responses (Wawrocki et al., 2016; Guegan and Legembre, 2018). Also, UBE4B belongs to E3 ubiquitin ligases and allows cells to respond to a variety of stimuli to keep their internal environment stable (Karve and Cheema, 2011) and also involved in DNA damage repair (Ackermann et al., 2016). And two E3 ligases were just identified as the selection signatures among Egyptian chicken populations compared with that Brazilian and Sri Lankan (Walugembe et al., 2019). The strong selected signals in these genes indicate that NYs may have better disease resistance and stronger ability to survive in the harsh environment than other chickens evaluated in this study.

Chickens seem to be more sensitive to environmental stressors (particularly heat stress) (Lara and Rostagno, 2013). When broilers encounter chronic heat stress, physiological performance is altered, including stimulation of lipid accumulation, reducing fat decomposition, and enhancing the metabolism of amino acids (Geraert et al., 1996). Among the selected genes, FABP1, a fatty acid binding protein, has several functions including the mediation of catabolism or anabolism of lipid metabolic pathways, the preservation of intracellular fatty acid level and the regulation of FA-responsive genes transcriptions (Wang et al., 2019). FABP1 may be important for maintaining lipid metabolism and normal growth rates in NYs due to acclimation to the hot arid environment. By comparing the intramuscular fat (IMF) contents in three tissues (the cardiac, chest and leg muscles) between NY and three-yellow (TYC) chicken (a major meat-type broiler raised in China), NY showed significantly increased IMF contents than TYC (Wang et al., 2016).

To the best of our knowledge, our findings revealed the complex genetic mechanisms of adaptation to hot arid and harsh environments of native chickens in China for the first time. Although functional studies are further needed to confirm our findings, our work could improve our understanding of thermal, drought, and harsh environment acclimation in chicken genomes.

Whole-genome resequencing data for 30 unrelated chicken individuals have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under bioproject number PRJNA344300 and PRJNA553299. Previously published genome sequences from five Red Jungle Fowls (bioproject number PRJNA241474) were downloaded from the NCBI database.

The animal study was reviewed and approved by Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of Hunan Agricultural University.

JG and SL designed the project. JG drafted the manuscript with inputs from all authors. JG, QL, CL, and SL wrote and revised the manuscript. JG collected the chicken samples. JG, QL, CL, and SL analyzed the data. All the authors revised and approved the manuscript.

This work was supported by the grant from National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31501000).

QL and CL were employed by the company Novogene Bioinformatics Institute. SL was employed by the company Maxun Biotechnology Institute.

The remaining author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgene.2020.582355/full#supplementary-material

Ackermann, L., Schell, M., Pokrzywa, W., Kevei, E., Gartner, A., Schumacher, B., et al. (2016). E4 ligase-specific ubiquitination hubs coordinate DNA double-strand-break repair and apoptosis. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 23, 995–1002. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3296

Ahmadian, M., Liu, S., Reilly, S. M., Hah, N., Fan, W., Yoshihara, E., et al. (2018). ERRgamma preserves brown fat innate thermogenic activity. Cell Rep. 22, 2849–2859. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.02.061

Ahmed, R. (2005). Heat stress induced histopathology and pathophysiology of the central nervous system. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 23, 549–557. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2005.05.005

Alcalay, Y., Hochhauser, E., Kliminski, V., Dick, J., Zahalka, M. A., Parnes, D., et al. (2013). Popeye domain containing 1 (Popdc1/Bves) is a caveolae-associated protein involved in ischemia tolerance. PLoS ONE 8:e71100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071100

Alexander, D. H., Novembre, J., and Lange, K. (2009). Fast model-based estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome Res. 19, 1655–1664. doi: 10.1101/gr.094052.109

Bax, N. A., Lie-Venema, H., Vicente-Steijn, R., Bleyl, S. B., Van Den Akker, N. M., Maas, S., et al. (2009). Platelet-derived growth factor is involved in the differentiation of second heart field-derived cardiac structures in chicken embryos. Dev. Dyn. 238, 2658–2669. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22073

Bongiovanni, G., Fissolo, S., Barra, H., and Hallak, M. (1999). Posttranslational arginylation of soluble rat brain proteins after whole body hyperthermia. J. Neurosci. Res. 56, 85–92. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19990401)56:1andlt;85::AID-JNR11andgt;3.0.CO;2-T

Brooker, R., Widmaier, E., Graham, L., and Stiling, P. (2011). Biology. New York, NY: The McGraw-Hill Companies Inc.

Chen, H., Patterson, N., and Reich, D. (2010). Population differentiation as a test for selective sweeps. Genome Res. 20, 393–402. doi: 10.1101/gr.100545.109

Chen, S., Cao, P., Dong, N., Peng, J., Zhang, C., Wang, H., et al. (2015). PCSK6-mediated corin activation is essential for normal blood pressure. Nat. Med. 21, 1048–1053. doi: 10.1038/nm.3920

Collier, R. J., and Gebremedhin, K. G. (2015). Thermal biology of domestic animals. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 3, 513–532. doi: 10.1146/annurev-animal-022114-110659

Edwards, M. J., Walsh, D. A., and Li, Z. (1997). Hyperthermia, teratogenesis and the heat shock response in mammalian embryos in culture. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 41, 345–358.

Elbeltagy, A. R., Bertolini, F., Fleming, D. S., Van Goor, A., Ashwell, C. M., Schmidt, C. J., et al. (2019). Natural selection footprints among African chicken breeds and village ecotypes. Front. Genet. 10:376. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.00376

Elmore, S. (2007). Apoptosis: a review of programmed cell death. Toxicol. Pathol. 35, 495–516. doi: 10.1080/01926230701320337

Froese, A., Breher, S. S., Waldeyer, C., Schindler, R. F., Nikolaev, V. O., Rinne, S., et al. (2012). Popeye domain containing proteins are essential for stress-mediated modulation of cardiac pacemaking in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 1119–1130. doi: 10.1172/JCI59410

Gelfand, M. V., Hagan, N., Tata, A., Oh, W.-J., Lacoste, B., Kang, K.-T., et al. (2014). Neuropilin-1 functions as a VEGFR2 co-receptor to guide developmental angiogenesis independent of ligand binding. eLife 3:e03720. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03720.019

Geraert, P., Padilha, J., and Guillaumin, S. (1996). Metabolic and endocrine changes induced by chronic heatexposure in broiler chickens: biological and endocrinological variables. Br. J. Nutr. 75, 205–216. doi: 10.1017/BJN19960125

Guegan, J. P., and Legembre, P. (2018). Nonapoptotic functions of Fas/CD95 in the immune response. FEBS J. 285, 809–827. doi: 10.1111/febs.14292

Hillier, L. W., Miller, W., Birney, E., Warren, W., Hardison, R. C., Ponting, C. P., et al. (2004). Sequence and comparative analysis of the chicken genome provide unique perspectives on vertebrate evolution. Nature 432, 695–716. doi: 10.1038/nature03154

Hillman, P. E., Scott, N., and Van Tienhoven, A. (1982). Vasomotion in chicken foot: dual innervation of arteriovenous anastomoses. Am. J. Physiol. 242, R582–R590. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1982.242.5.R582

Huang, D. W., Sherman, B. T., and Lempicki, R. A. (2009). Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 4, 44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211

Karve, T. M., and Cheema, A. K. (2011). Small changes huge impact: the role of protein posttranslational modifications in cellular homeostasis and disease. J. Amino Acids 2011:207691. doi: 10.4061/2011/207691

Lara, L. J., and Rostagno, M. H. (2013). Impact of heat stress on poultry production. Animals 3, 356–369. doi: 10.3390/ani3020356

Li, H., Handsaker, B., Wysoker, A., Fennell, T., Ruan, J., Homer, N., et al. (2009). The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352

Miao, Y., Peng, M., Wu, G., Ouyang, Y., Yang, Z., Yu, N., et al. (2013). Chicken domestication: an updated perspective based on mitochondrial genomes. Heredity 110, 277–282. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2012.83

Moffett, P., Reece, M., and Pelletier, J. (1997). The murine Sim-2 gene product inhibits transcription by active repression and functional interference. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 4933–4947. doi: 10.1128/MCB.17.9.4933

Moura-Alves, P., Faé, K., Houthuys, E., Dorhoi, A., Kreuchwig, A., Furkert, J., et al. (2014). AhR sensing of bacterial pigments regulates antibacterial defence. Nature 512, 387–392. doi: 10.1038/nature13684

Mutaf, S., Seber Kahraman, N., and Firat, M. (2009). Intermittent partial surface wetting and its effect on body-surface temperatures and egg production of white and brown domestic laying hens in Antalya (Turkey). Br. Poult. Sci. 50, 33–38. doi: 10.1080/00071660802592399

Nawab, A., Ibtisham, F., Li, G., Kieser, B., Wu, J., Liu, W., et al. (2018). Heat stress in poultry production: mitigation strategies to overcome the future challenges facing the global poultry industry. J. Therm. Biol. 78, 131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2018.08.010

Ng, Y. S., Rohan, R., Sunday, M., Demello, D., and D'amore, P. (2001). Differential expression of VEGF isoforms in mouse during development and in the adult. Dev. Dyn. 220, 112–121. doi: 10.1002/1097-0177(2000)9999:9999andlt;::AID-DVDY1093andgt;3.0.CO;2-D

Park, C. C., Morel, J. C., Amin, M. A., Connors, M. A., Harlow, L. A., and Koch, A. E. (2001). Evidence of IL-18 as a novel angiogenic mediator. J. Immunol. 167, 1644–1653. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.3.1644

Phan, D., Rasmussen, T. L., Nakagawa, O., McAnally, J., Gottlieb, P. D., Tucker, P. W., et al. (2005). BOP, a regulator of right ventricular heart development, is a direct transcriptional target of MEF2C in the developing heart. Development 132, 2669–2678. doi: 10.1242/dev.01849

Rubin, C.-J., Zody, M. C., Eriksson, J., Meadows, J. R., Sherwood, E., Webster, M. T., et al. (2010). Whole-genome resequencing reveals loci under selection during chicken domestication. Nature 464, 587–591. doi: 10.1038/nature08832

Ruhrberg, C., Maden, C., and Schwarz, Q. (2009). Neuropilin 1 controls cardiovascular development through neural crest cells. FASEB J. 23, 302.303–302.303.

Schwarz, Q., Vieira, J. M., Howard, B., Eickholt, B. J., and Ruhrberg, C. (2008). Neuropilin 1 and 2 control cranial gangliogenesis and axon guidance through neural crest cells. Development 135, 1605–1613. doi: 10.1242/dev.015412

Torlopp, A., Breher, S. S., Schluter, J., and Brand, T. (2006). Comparative analysis of mRNA and protein expression of Popdc1 (Bves) during early development in the chick embryo. Dev. Dyn. 235, 691–700. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20687

Walugembe, M., Bertolini, F., Dematawewa, C. M. B., Reis, M. P., Elbeltagy, A. R., Schmidt, C. J., et al. (2019). Detection of selection signatures among Brazilian, Sri Lankan, and Egyptian chicken populations under different environmental conditions. Front. Genet. 9:737. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00737

Wang, M.-S., Li, Y., Peng, M.-S., Zhong, L., Wang, Z.-J., Li, Q.-Y., et al. (2015). Genomic analyses reveal potential independent adaptation to high altitude in Tibetan chickens. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 1880–1889. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msv071

Wang, M.-S., Thakur, M., Peng, M.-S., Jiang, Y., Frantz, L. A. F., Li, M., et al. (2020). 863 genomes reveal the origin and domestication of chicken. Cell Res. 30, 693–701. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0349-y

Wang, Q., Li, D., Guo, A., Li, M., Li, L., Zhou, J., et al. (2020). Whole-genome resequencing of dulong chicken reveal signatures of selection. Br. Poultry Sci. 61, 624–631. doi: 10.1080/00071668.2020.1792832

Wang, Y., Hui, X., Wang, H., Kurban, T., Hang, C., Chen, Y., et al. (2016). Association of H-FABP genepolymorphisms with intramuscular fat content in three-yellow chickens and hetian-black chickens. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 7:9. doi: 10.1186/s40104-016-0067-y

Wang, Z., Yue, Y. X., Liu, Z. M., Yang, L. Y., Li, H., Li, Z. J., et al. (2019). Genome-wide analysis of the FABP gene family in liver of chicken (Gallus gallus): identification, dynamic expression profile, and regulatorymechanism. Int. J. Mol. Sci 20:5948. doi: 10.3390/ijms20235948

Warren, W. C., Hillier, L. W., Tomlinson, C., Minx, P., Kremitzki, M., Graves, T., et al. (2017). A new chicken genome assembly provides insight into avian genome structure. G3 7, 109–117. doi: 10.1534/g3.116.035923

Wawrocki, S., Druszczynska, M., Kowalewicz-Kulbat, M., and Rudnicka, W. (2016). Interleukin 18 (IL-18) as a target for immune intervention. Acta Biochim. Pol. 63, 59–63. doi: 10.18388/abp.2015_1153

Wolfenson, D., Frei, Y. F., Snapir, N., and Berman, A. (1981). Heat stress effects on capillary blood flow and its redistribution in the laying hen. Pflügers Archiv. 390, 86–93. doi: 10.1007/BF00582717

Keywords: positive selection, native chicken, environmental adaption, whole genome resequencing, candidate genes

Citation: Gu J, Liang Q, Liu C and Li S (2020) Genomic Analyses Reveal Adaptation to Hot Arid and Harsh Environments in Native Chickens of China. Front. Genet. 11:582355. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.582355

Received: 11 July 2020; Accepted: 01 December 2020;

Published: 21 December 2020.

Edited by:

Nick V. L. Serão, Iowa State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Angelica G. Van Goor, United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), United StatesCopyright © 2020 Gu, Liang, Liu and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jingjing Gu, aG5hdWd1QDE2My5jb20=; Sheng Li, bWF4dW5sc0BhbGl5dW4uY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.