94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. For. Glob. Change, 25 May 2021

Sec. Tropical Forests

Volume 4 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/ffgc.2021.624072

This article is part of the Research TopicAmazon Rainforest Future Under the Spotlight: Synergies and Trade-Offs Between Conservation and Economic DevelopmentView all 9 articles

In 2012, the new, revised Forest Code was established as the legal and regulatory framework for Brazilian forests. Though illegal logging has continued, frames about Brazil's forest policy and management have changed since that time. While until 2010 the successful implementation of forest policies and the resulting decline in deforestation rates were there for all to see and appreciate, the increase in the deforestation rate since then has become the focus of international criticism. With the help of a structured review of international scientific literature, newspaper articles, and programmes initiated by non-governmental organizations' (NGO) and international organizations' (IO), this paper aims to analyse the frames of illegal logging and its governance responses in Brazil since 2012. The review is guided by the framework of diagnostic (What is the problem? Who is to blame?) and prognostic framing (proposed policy and governance solutions). The main findings revealed a master frame of environmental justice that combines injustice toward indigenous people with the victimization of forest and environment at large. Embedded in this master frame, specific frames that follow the institutional logic of the single policy discourses have been identified. Finally, the results show a strong national focus of governance with continued emphasis on command and control instruments.

In recent years, the debate about forest management in Brazil gained considerable public and political attention. Increasingly frequent news reports on the growing deforestation rate are disclosing data gathered from monitoring systems, e.g., those released in November 2020 by the Brazilian National Institute for Space Research (INPE) showing clearings in the Amazon that have increased by at least 47% compared to 2018. Internationally, these numbers are observed and discussed critically by scientists, NGOs, politicians, and the media. In particular, western industrialized countries of the Global North pay great attention to those alarming numbers and describe the situation in the Amazon as a subject of global concern that Brazil must take care of.

The conversion of forest areas into agricultural land has been identified as a major driver of deforestation. Though its scope and size is often based on conflicting “guesstimates” (Bisschop, 2012), illegal logging plays a major role in this deforestation process (Lawson, 2014) undermining the efforts of sustainable forest management and affecting the livelihood of people. The first decade of the 21st century saw a number of (international) positive responses praising Brazil governance efforts in combatting illegal logging (Boucher et al., 2013; Nepstad et al., 2014). However, the second decade saw a raise of criticism and turmoil around the change of the Brazilian government in 2019 (e.g., Kröger, 2020).

While a lot of research has been presented about deforestation rates in Brazil and about technical opportunities and restrictions to gather data and monitor deforestation (Dantas Chaves and de Carvalho Alves, 2019; Schimabukuro et al., 2019) literature focusing on a social scientific perspective is limited and mostly focuses on the shortcomings of governance and very specific case studies (Balbinotto Neto et al., 2012; Waldhoff and Vidal, 2015; Tritsch et al., 2016; Celentano et al., 2018; Condé et al., 2019). This paper focuses on illegal logging, as one cause of deforestation. It therefore differs from other papers more broadly referring to deforestation in general not differentiating between legal or illegal deforestation. Though it has been recognized earlier that illegal and legal activities of deforestation are not easy to disentangle, this paper limits its focus on illegality to as well provide an overview about its specific consequences, e.g., specific governance responses. Thus, results of this paper will contribute to the larger body of literature on illegal logging and complement the literature on environmental crime.

What is understood as illegal or not is often perceived as clearly separate, demarcated by those activities violating existing law as illegal. This positivistic understanding has been highly criticized as it only refers to the juridical perspective of illegality while neglecting other norms and moral considerations strongly linked with the question of legitimacy. These questions are in particular addressed when the perspective of fairness and justice come into play. Additionally, the juridical perspective neglects conflicting issues and vagueness as well as the changes over time of what becomes illegal. As a review paper we follow the definition of what is counted as illegal and what is not from the articles included in our research.

Our paper starts out from an interpretative approach, assuming that controversial and complex issues are constructed in political discourses that structure meanings through frames. That said, this paper does not deny deforestation or illegal logging as a part of the Brazilian reality, but draws attention to the different problems and solutions that are supported in the discourse and that shape our understanding. Therefore, this paper aims to fill the research gap of interpretive analysis of illegal logging in Brazil by providing an overview of the frames of illegal logging in Brazil and its governance responses in different discourse forums since the 2012 Brazilian Forest Code (FC) reform.

Home to the largest tropical rainforest in the world, the Amazon (Charity et al., 2016, p. 8), Brazil has always been in the spotlight regarding deforestation, which is one of the country's largest sources of greenhouse gas emissions (Adelman, 2015, p. 195; Bento et al., 2019, p. 111). As part of the efforts to tackle the problem, in 2016, Brazil signed the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, committing to eliminate illegal deforestation in the Amazon by 2030.

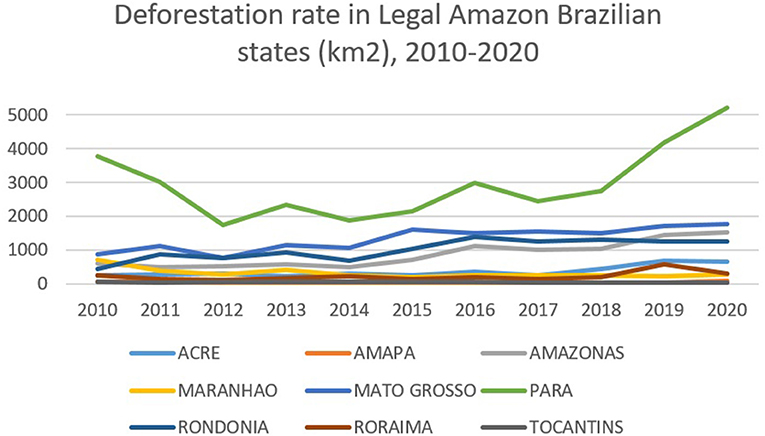

As a reaction to the deforestation peak in the Amazon in 2004, also documented by non-governmental organizations, the Brazilian federal government established a program called Plano de Ação para Prevenção e Controle do Desmatamento na Amazônia Legal (PPCDAM - Action Plan for Prevention and Control of Deforestation in the Legal Amazon to halt Amazon deforestation) (MMA, 2019). PPCDAM was a follow-up to the Pilot Plan for Brazilian Tropical Forest Protection (PPG7) from 1990 (De Antoni, 2010) and includes wild fire combat programmes. Due to this initiative and other international, private-public, and private sector initiatives, rates dropped by almost 80% between 2004 and 2012 (Bento et al., 2019, p. 115). However, since 2012, deforestation has slowly started to increase again, “casting doubts on the long-term sustainability of past conservation policy achievements” (Schielein and Börner, 2018). Since 1988 the INPE/PRODES system monitors deforestation in the Amazon. Taking a sample between 2004 and 2019, the highest rate of deforestation was registered in 2004, with 27,772 km2, while the lowest rate of deforestation was reported in 2012, with 4,571 km2. In 2008 the Brazilian Government committed to reduce deforestation to 20% of the historical rate by 2020 (Government of Brazil, 2007). Additionally, the network of Amazon protected area has been expanded (from 1.26 to 1.82 Mill km2). Nonetheless, the increase in deforestation has doubled since then, reaching 11,088 km2 in 2020 (INPE, 2020a). For a visual representation Figure 1 shows the Brazilian Amazon deforestation rates since 2010, by Legal Amazon region State.

Figure 1. Brazilian Amazon deforestation rates from 2010 to 2020, by Legal Amazon State (source: TerraBrasilis, INPE, 2020b).

The FC has a long standing history, being created in 1965 and transformed in the 1990s into a “de facto environmental law” (Soares-Filho et al., 2014). In 2001 the FC required landowners to set aside a minimum percentage of forest as legal reserves (LRs), with different sizes depending on the biome, e.g., in the Amazon the LR is 80%. Furthermore, the FC identified Areas of Permanent Preservation (APPs) including Riparian Preservation Areas (RPAs) to protect riverside forest buffers and Hilltop Preservation Areas (HPAs).

In 2012, a new FC was established. Even though the new FC kept the definitions of LRs and RPA, it also introduced several changes, e.g., the definition of HPAs has been included (Soares-Filho et al., 2014). The new Forest Code still included the obligation to restore illegally deforested areas at the expenses of the landowners, but made an exception for small farms. The size requirements to qualify as a small farm vary depending on the area, e.g., in the Amazon small farms can have a size of up to 440 ha, which resulted in a substantial reduction of the restoration requirement. On the other hand, the new FC has introduced new measures meant to respond to illegal logging, e.g., the enforcement of the national rural environmental registry (CAR), which assists in the identification of environmental compliance within private properties (Azevedo et al., 2017). Additionally, measures among other allowing the offset of surplus forest areas, have been added to the FC (Soares-Filho et al., 2014). Already since the initial drafting of the new FC, its effective implementation has been perceived as challenging and largely political (Soares-Filho et al., 2014). Additionally, logging requires licensing through a sustainable forest management plan approved by state environmental agencies. This instrument existed before the FC but has been reinforced by it. Illegal timber, therefore, can result e.g., from areas without an approved management plan or from forest areas that have been protected by regulations other than FC. This paper takes 2012 as the starting point of the analysis as it is argued in literature that the framing of forest has changed substantially since that time (Kröger, 2017).

As a starting point, this paper adopts an interpretative perspective on policy analysis. In contrast to other approaches (e.g., rational choice or institutionalism), interpretative approaches assume that words (in the form of text, spoken language, etc.) do matter in politics as they construct meaning. Following Dryzek (1997), we consider a discourse as a way of capturing and depicting the world. Discourse analysis has been employed frequently in order to analyse and understand policy controversies. In the terminology of Schön and Rein (1994), a discourse is a policy debate and framing is the way in which policy problems are structured and made sense of within this debate. Schön and Rein (1994) understand frames as “resting on an underlying structure of belief, perception and appreciation,” which they further describe as “taken for granted assumption structures, held by participants in the forums of policy discourse and by actors in policy making arenas.” Following the distinction made by Schön and Rein, we focus on narrative frames as generic storylines that underlie the particular problem-setting stories. These narratives tell what the problem is (about) and how it might be solved.

Our framework is based on the concept of frames as used in social movement studies. In this context, frames are understood as “intended to mobilize potential adherents and constitutes, to garner bystander support, and to demobilize antagonists” (Snow and Benford, 1988: 198). However, they also follow the primary definition of Goffman (1974), who describes frames as “schemata of interpretation” that help to organize experiences and understandings of complex situations by highlighting specific elements and downplaying others. The use of this structure has proven to be fruitful for the analysis of discourse in a variety of empirical studies going well-beyond social movement research. Collective action frames as used in social movement studies are constituted by core framing tasks that comprise diagnostic framing, prognostic framing, and motivational framing (Snow and Benford, 1988). We decided to use the differentiation between diagnostic and prognostic framing in our analytical scheme, while we found that motivational framing was not relevant for our study. Diagnostic framing asks the basic question of what the problem is, but also addresses blame and responsibility (Benford and Snow, 2000). Hence, diagnostic framing prompts reasoning about problems or specific causes, but also identifies the victims of a given problem. On the other hand, in prognostic framing, a plan for tackling the problem is central (Benford and Snow, 2000). Other scholars of frame analysis support naming problems and proposing solutions as important steps in the framing process (Schön and Rein, 1994 and Van Hulst and Yanow, 2016). Additionally, the role of those actors who are supposed to have agency to solve the problem is often identified as well. Schön and Rein (1994) argue that interests are shaped by frames and frames are used to promote interests. Consequently, they perceive policy controversies as disputes amongst actors who sponsor conflicting frames.

Following Schön and Rein's frame approach, we do not take a “thick” discourse approach (Arts et al., 2010) that ignores materiality, but we make an explicit distinction between discourse and frames on the one hand and institutions on the other (Van den Brink and Metze, 2006). At the same time, we assume interdependencies between the two, understanding discourse and frames as responses to institutional realities (Schmidt, 2015), in this case the Brazilian FC and its governance setting.

Guided by this framework and the issue at hand, this paper will provide an overview of the frames of illegal logging in Brazil and its governance responses by addressing following research questions:

RQ 1: What are the elements of the prevailing frame of illegal logging in Brazil and its governance responses?

RQ 2: Do frames about illegal logging in Brazil and its governance responses differ in the different policy discourses or do they follow a similar master frame?

This article is based on a discourse review that builds on material in different policy fora addressing illegal logging in Brazil and its governance responses. The main structured review concentrates on scientific papers. The analysis of scientific literature as a policy forum is crucial, as scientific articles present the knowledge frames of the problem of illegal logging and provide justification for those frames. In a second step, we analyzed other relevant policy fora that contribute to the construction of meaning and the spreading of knowledge. These include media articles published in Brazil, but also in countries that are major consumers of timber exported from Brazil (US, Germany, and China). Additionally, we also analyzed policy programmes of International Organizations and NGOs referring to illegal logging in Brazil and its governance responses.

Our analysis covers a time period of about 8 years (from 2012 to mid-2020), the starting point of which is marked by the introduction of the new FC in Brazil and the increased deforestation rate that followed it. This study's main methodological problems arose from the diversity of the discourses and the variety of their sources and products. We found ourselves forced to use a different selection process for each type of discourse:

A) Scientific Articles

The structured review of scientific articles was conducted in four steps. First, the material was gathered from two databases, Web of Science and Google Scholar, by using the search terms “illegal logging” and “Brazil” for title, abstract, and keywords. Only articles published in scientific journals and written in English or in Portuguese were considered. We believed that articles written in English as the major language of research would provide the most encompassing overview of the international scientific discourse. We added Portuguese articles to include the “insider” perspective of scientists from the country, who might have in-depth insights and a powerful position in framing the situation. Duplicates, as well as articles that were not published in scientific journals have been removed. The remaining articles have been analyzed for eligibility with the precondition that a minimum of one paragraph should refer to illegal logging and its governance in Brazil. This condition was necessary as some of the articles we found addressed only situations before 2012, and did not focus on Brazil or only referred to deforestation, without a focus on illegal logging. This selection process left us with a total of 25 articles which we then proceeded to analyse.

B) Media Articles

The media articles reviewed were gathered by using the Lexis Nexis database, filtering for “Newspapers” and the keywords “illegal logging” and “Brazil,” in English, German, and Portuguese. For each country, we considered nationwide quality newspapers with a broad range of audience including other media and political decision makers. For the United States “The New York Times International” and “The Washington Post,” for Germany “Süddeutsche Zeitung,” “Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung,” and “Die Zeit,” for Brazil “Folha de São Paulo,” “O Estado de São Paulo,” and “O Globo.” For China, for practical reasons, we included only an English language newspaper: “China Daily.” This search yielded a total of 26 newspaper articles that we then proceeded to analyse: 14 American, 2 German, 3 Chinese, and 7 Brazilian. Due to the small number of articles from each country, a comparative analysis between countries was not possible.

C) Policy Statements of NGO/IOs

Policy statements of NGOs and IOs were identified through the same keywords in an open internet search. Only publications and webpages published between 2012 and mid-2020 in English or Portuguese were considered. We were able to select a total of 14 political programmes and 6 NGO/IO Policy programmes published on webpages for our analysis, from organizations such as Greenpeace, WWF, IUFRO, Amazon Watch, Imazon, Chatham House, Human Rights Watch, UNEP, and Interpol.

All material has been analyzed following a structured category system guided by the theoretical framework of diagnostic and prognostic action frames. Additionally, the category system makes use of formal categories, such as date of publication, journal, author, etc. Diagnostic categories addressing the problem of the situation of illegal logging, e.g., the scope of the problem, drivers for illegal logging, victimization, and responsibilities. Finally, the category system comprises categories addressing the prognostic dimension of frames, e.g., about possible ways to solve illegal logging and overcome governance weaknesses. All text elements that we identified as addressing one of the categories were directly coded into an excel file which we then used as a basis for a descriptive analysis. The results of this analysis are the core of what is presented below.

The PRISMA flow diagram in Figure 2 visually presents the systematic review performed by the authors.

The result chapter deals with the formal characteristics of the discourses and the collective action frames and includes both diagnostic and prognostic framing.

The analysis of the discourses on illegal logging and governance responses in Brazil in scientific literature, media, and NGOs/IGOs fora show certain similarities in its formal characteristics, e.g., the publication timeline. Considering the selection process of the data and its limited comparability the results presented in Figure 3 about the development of the amount of attention drawn to the issue of illegal logging must be interpreted with caution. However, they do provide an overview of the general dynamics of the discourses, peaking in 2018/2019, a time marked by Bolsonaro's election as president of Brazil and by large forest fires.

The scientific articles analyzed include seven review articles and 17 original contributions. Six of the scientific articles have been published in Brazilian Portuguese in geographically focused journals (i.e., journals focused on South America). The remaining 19 have been published in international, English language journals. The Amazon region forms the main area of interest of these papers. Some of them focus on a specific local area within the Amazon. Other papers look at the issue on a national level. Only two articles address cross-national issues: one deals with both Brazil and Peru and another presents a comparative analysis between Brazil and Indonesia. The majority of articles is (co-)authored by authors who have an academic connection to Brazil. Scientific articles published in international journals do not primarily focus on the situation as it appears around the date that the article was published. This depends on the fact that it takes time to produce and publish an article, but also on the fact that many articles set out to provide ex-post analyses for specific periods. Therefore, scientific articles published in a specific year rarely refer to the governance situation in that same year or in the previous one. Consequently, political situations, e.g., the election of Jair Bolsonaro, are usually neglected, with the exception of the paper of Carvalho et al. (2019).

Similar to the scientific literature, the majority of the 26 analyzed newspaper articles focus on the Amazon region, with a peak in 2019. The articles published during the peak (specifically between September and December 2019) reported on the large forest fires that ravaged the Amazon biome in particular during the month of August.

Much like that of the scientific and newspaper articles, the career of the reports from NGOs/IGOs and official policy documents has a peak in 2018/2019. While encompassing reports such as scientific articles take some time to get published and therefore often refer back to situations in the past, reports presented online are usually topical and discuss the present situation. Therefore, the peak in 2018 and 2019 is strongly related to the new government and its environmental policy, and, more specifically, is concerned with deforestation and illegal logging. Like the scientific and newspaper articles, NGO/IO articles focus on the Amazon region, sometimes even on specific local spots in the Amazon, e.g., the states of Rondônia, Pará, and Mato Grosso.

In the following section, the diagnostic and prognostic frames of illegal logging and its governance responses in the scientific, newspaper, and NGOs/IOs discourse are presented.

Research on illegal logging and timber trade has shown that illegal activities can take place along the whole supply chain, from extraction to transport, from processing to consumption (Tacconi et al., 2016). However, the scientific discourse on illegal logging in Brazil concentrates on the extraction of wood, ranging from single extraction of trees, small- and medium-scale logging, including for fuelwood production, to large-scale industrial logging. Other illegal activities subordinated or parallel to illegal logging pass relatively unnoticed. An exception within the scientific discourse is, for example, the paper from Reboredo (2013), where the author investigates the illegal activities around the tree felling process as well as around other phases of the timber trade, e.g., the certification and export of illegal timber. Like the scientific discourse, the newspaper discourse as well provides a focused framing of illegal activities concentrating on the extraction of wood. News reports focus particularly on the deforestation of larger areas of natural forests, e.g., “Thousands of square miles of forest have already been razed in indigenous territories, where large-scale industrial activity is prohibited.” (Londono, 2018). In contrast, the discourse of NGOs/IOs offers a more encompassing picture of illegal activities. In particular, it draws attention to the (international) criminal networks in the supply chain, dealing with forest management plans, inventories, timber laundering, trade, transport, and partly with manufacturing, or sometimes with the full supply chain, e.g., “Forest Inventory: The first step in a cycle of illegality” (Greenpeace, 2018).

Tacconi et al. (2016) have specified specific types of illegal activities. Two major types of illegal activities are found to be dominant in the discourses. One is the violation of ownership rights, and more specifically the rights of indigenous people in the Amazon, e.g., Law 6.001 on Indigenous People's Rights (from 1973) (Celentano et al., 2018). The second type of illegal activity often addressed in the discourse is the violations of resource management rules and regulation, namely the extraction of wood without authorization or the extraction of wood from prohibited areas, e.g., the violation of Law 9.985 on Conservation Units (from 2000) (e.g., Paiva et al., 2020). In the discourse of NGOs/IOs, the violation of public trust, in particular in the form of corruption, is addressed more often than in the scientific discourse. Corruption is either presented in a specific situation where officials, e.g., police, judiciary or forestry officials, are bribed or through the more general corruption perception index of Brazil, or due to a “dysfunctional timber traceability system” (UN Environment and UNEP-WCMC, 2018).

Different discourses focus their attention on different drivers of illegal logging, such as market-driven and infrastructural drivers, socio-economic drivers, and drivers related to governance. The demand for wood products and other commodities, like soy or beef, is mentioned as an important driver for illegal logging. Additionally, large economic players are named as drivers, pointing toward specific sawmills processing (and laundering) of illegal wood and those companies exporting from these sources to international customers located in particular in the US and Europe (e.g., Greenpeace, 2014; Amazon Watch, 2019). The demand from the (global) market is directly related to another driver: the development of infrastructure (e.g., Viscidi and Ortiz, 2019; Paiva et al., 2020), e.g., “Highway projects (…) create access to previously remote areas, allowing for expansion of legal and illegal activities that cause deforestation.” (Viscidi and Ortiz, 2019). Poverty is also addressed as a socio-economic driver, being a reason for non-compliance due to bureaucratic costs, creating barriers for people to comply to the law, thus, resorting to illegal extraction of wood for their livelihoods (e.g., Waldhoff and Vidal, 2015; Tacconi et al., 2019). This observation has been supported as well by more general comparative studies, comprising Brazil, stating that “the main causes of illegal logging are poverty, weak governance and the absence of sustainable forest management” (Reboredo, 2013).

Drivers related to weaknesses of the governance system have been addressed frequently in the various discourses, including weak enforcement, property rights, and power imbalances. Weak enforcement and corruption appear as the prevailing governance-related drivers in the discourses, in particular in the second half of the observation period. Before the change in government in 2019, enforcement was understood as something that was actively pursued but challenged due to the problem of collecting fines: “As a consequence, the value of fines issued increased eightfold over the period (…) although only 2,5% of the fines were successfully collected” (Reboredo, 2013: 300). The later discourse, i.e., concerning the time after the changes in government, clearly points toward enforcement as a strategic governance weakness: “And he [Bolsonaro] delivered: Since he took office in January, the agency says it has issued 29.4 percent fewer fines for violations, including illegal burning and deforestation”. This quote as well as other articles refer to Bolsonaro's statement about IBAMA (the federal environmental agency) as an “industry of fines” which he claims to prevent. Another media article describes a circumstance in which Bolsonaro's government sends the army for inspection, since IBAMA does not have enough staff, yet the operation clearly does not follow IBAMA's recommendation on the places to inspect for illegal logging. The army team went instead to an area that had already been inspected and identified possible illegal wood, though did not confiscate it. Heavily funded and with reports in English to show to donors, these environmental inspection operations under Bolsonaro seem to be “fiasco” operations which delegitimize the official environmental agency (Amaral, 2020).

The only scientific paper covering the time after the change in government addresses this change as well: “Authorities only catch a small fraction of illegal actions, and if caught, the probability of the perpetrator actually paying the resulting fine is also very low.” (Carvalho et al., 2019: 127). However, there have been as well a few controversial perspectives on enforcement referring mainly to the beginning of the observation period – either by articles that have been published early after 2012 or by articles that focus to a larger degree on the governance situation before 2012. Those articles referred to enforcement as a challenging element but also as something that was been successfully implemented in Brazilian forest policy (Boucher, 2014; Tacconi et al., 2019). A specific acknowledgment of enforcement can be observed in the scientific discourse. Here the challenges of enforcement or the lack of enforcement are explained as a consequence of insufficient monitoring partly due to technological deficiencies (Carvalho et al., 2019) and lack of inspection due to low investment and personnel (Muniz and Pinheiro, 2019). This lack of enforcement has been given as a reason for the establishment of the Public Forest Management Law in Brazil (Law 11.284/2006), described by some authors as a solution for decentralized management (Roma and de Andrade, 2013; Chules et al., 2018).

Property rights are addressed as drivers in a few cases: when undesignated lands belonging to the Federal or the State Government are exposed to land-grabbing (Santos de Lima et al., 2018), when talking about the expanded law from 2017 that allowed for the privatization of larger patches of land and leading to (illegal) deforestation and burning, and when the deprivation of property rights results in illegal activities. Other governance related drivers of illegal logging addressed in the discourses are corruption, deficient regulation, and limited financial incentives for legal resource use (Brancalion et al., 2018; Carvalho et al., 2018).

Later in the observation period, the media discourse is increasingly concerned with power asymmetries between the agribusiness and the political system on the one hand and indigenous rights on the other hand. These asymmetries have been further boosted by some political developments of the Bolsonaro government, e.g., by the shifting of responsibilities for indigenous land over demarcation (e.g., Carvalho et al., 2019).

The governance-related drivers of illegal logging are based on a fundamental understanding of governance as national governmental rules and regulations with a central role of the state, highlighting command and control mechanism. First and foremost, they refer to the Forest Code but as well to the Law on Public Forest Management (Law 11,284/2006), the 2000 Law 9.985 (SNUC - on conservation units), and the 1998 Law 9.605 on Environmental Crimes. Other forms of governance, like co-governance or self-governance, are mentioned to a much lesser degree (McDermott et al., 2014; Tritsch et al., 2016). Here the private sector and the civil society become more central in political steering and the Brazilian government is less prominent. These articles refer to certification or other voluntary agreements.

Directly linked with the drivers is the identification of the actors who are to blame or who carry responsibility. The framing in the three different discourses promotes a similar narrative with a different emphasis. Those held responsible for illegal logging are mainly political actors and agencies as well as large, international and small, mostly national economic players. Most scientific articles refer to political actors and agencies as those creating or pushing for illegal logging, e.g., weak governance. Carvalho et al. (2019) is the only scientific paper that directly refers to Jair Bolsonaro, which links the increased deforestation rate to the government, stressing that Bolsonaro “has a markedly anti-environmental stance both in rhetoric and practice,” and points toward specific institutional changes that easing the restriction on deforestation and illegal logging. In contrast, the majority of newspaper articles that make up the media discourse of the late 2019 directly criticize the newly elected president for his environmental policy and his negative effect on the Amazon, e.g., “The Amazon Is Completely Lawless” (Moriyama and Sandy, 2019). The international articles report a statement of Bolsonaro before his election, in which he promised to open the Amazon for business, and see this as a foreshadowing of the increasing deforestation that followed his election: “The industries [agribusiness] found an ally in Mr Bolsonaro, (…).” His government, Ms. Silva said, “is not fighting to preserve environmental governance” (Moriyama and Sandy, 2019). The tone of these articles does not vary among the newspapers, including those from Brazil with statements such as “the federal government's complicity with environmental crimes has been made explicit” (Prestes, 2020 - author's translation). There is only one exception that points to the positive effects of Bolsonaro's governance, e.g., in a letter to the editor “Brazil is working to save the Amazon” (Forster, 2019). In contrast to the other two fora, in the discourse of NGOs/IOs, large economic players are more prominently addressed as those to blame for illegal logging (Amazon Watch, 2019).

In diagnostic framing, the counterpart of those to blame are the victims of illegal logging. Even though across all discourses there is one prevalent and fairly consistent story about the victims, a difference in emphasis between the discourses can be observed. First of all, the forest itself and the environment are mostly identified as victims. This narrative is strongly connected with the negative effects on climate change, with the loss of biodiversity, or, more in general, with the environmental importance of the Amazonian forest: “Illegal Logging and forest fires in the years of severe El Niño droughts threatened the maintenance of environmental services provided by the Amazonian forests.” (Condé et al., 2019: 1). A second narrative, which is pushed particularly by the media discourse, is that concerning local communities, and more specifically indigenous tribes, that are being stripped of their home (the forest) and their livelihood and are threatened by violence (e.g., Fischermann and Lichterbeck, 2014). Additionally, indigenous people are victimized not only because they are losing their forest, but also because they are being exposed to new diseases and to unfamiliar cultural elements that challenge the norms of their societies (Fischermann and Lichterbeck, 2014). Even though this storyline is rather clear, sometimes the boundaries between the culprits and the alleged victims become blurred, e.g., when the “chief” of a tribe is accused of selling their forest and their people for their own financial benefit (Fischermann and Lichterbeck, 2014). Papers focusing on Brazilian forest concessions constitute an exception in that they widen the victims pool by including the industry, as illegal logging lowers the price of timber and creates unfair competition (Azevedo-Ramos et al., 2015; Santos de Lima et al., 2018).

In core action frames, solving problems is categorized as being part of prognostic framing as it strongly relates to action plans or strategies. In the frames of illegal logging and its governance responses, solving the problem is also diagnostic to some extent, as it refers to already ongoing situations. This element of the frame is more ambiguous across the discourses than other elements mentioned before. In contrast to the scientific discourse, in particular the media discourse but as well the NGO/IO discourse refers to informal practices responding to illegal logging, amongst which violence, e.g., “The Tenharim [a tribe in the Amazon – author's note] started to violently fight back against tree fellers. (…) This is how the indigenous became the last guardians in many places of the Amazonian forest.” (Fischermann and Lichterbeck, 2014 – author's translation). This informal practice is framed in the newspapers as the only solution in a country where governance and low enforcement are weak. Therefore, indigenous people are presented by newspapers not only as victims, but also as actors who fight to prevent further illegal logging. In contrast, the scientific discourse and the discourse of NGOs/IOs portray local communities and indigenous people as a solution to the problem only in exceptional cases. Instead, they address political actors and agencies at the national level as those that should solve the problem (Santos de Lima et al., 2018). They also suggest that those who are responsible for illegal logging can also act as solvers, e.g., large economic players or small local economic players (Brancalion et al., 2018). Additionally, the discourse of IOs portrays IOs themselves as being in a position to solve the problem of illegal logging (UNEP and Interpol, 2012; Bueno and Cashore, 2013).

The discourses do not stop at the attribution of agency to specific actors, but also propose solutions to improve the situation in the future. In the scientific discourse, legal frameworks are usually presented as the key to successfully fight illegal logging. NGOs/IOs and the media share this opinion to a large degree. However, some do not refer to any possible improvement and some do not see the change of governance as something that could help at all (Uribe, 2013; Fischermann, 2019). When comparing how the governance situation is described in the diagnostic framing, in particular in the scientific discourse, one can observe how the prognostic frames show a slight shift away from a clear state-centric governance and a move toward an increased co-governance and self-governance. However, the focus remains on the national level: in fact, governance systems beyond the nation state of Brazil are only referred to as a solution to a minor degree. Unsurprisingly, the NGOs/IOs discourse is the one that most often hints toward transnational and international governance solutions (Kleinschmit et al., 2016). Other governance solutions presented in the discourse are the guarantee of land tenure rights and an increased enforcement of existing rules and regulations: “strategies must be therefore considered, not only related to logging per se, but also to land grabbing issues and related illegal deforestation” (Santos de Lima et al., 2018). In addition to a change of governance modes, technological fixes are also described as a way to solve problems. The scientific discourse in particular proposes new monitoring techniques, remote sensing, and life tracking as possible solutions.

In the following section, we will summarize the main results presented in the former section and we will contextualize them within the scientific literature on illegal logging and within the scientific discussion about frames.

Starting with the contextualization of the problem of illegal logging, the discourses show strong similarities in their focus on the Amazon region, in their career, and in their emphasis on the extraction phase of the wood supply chain. The focus on the Amazon region reflects the geographical balance of forest areas in Brazil but also the (international) attention payed to the Amazon.

The career of the discourse presented seems to contradict studies that compare environmental scientific, media and political discourses (Weingart et al., 2000). These show that the longer production process of scientific literature results in the scientific discourse moving at a different pace. Naturally, newspaper discourses react directly to new situations. In contrast, scientific discourses, as well as IOs' discourses, are more long-term and need time for preparation and publishing. Therefore, newspaper discourses are the ones that respond to the government changes in Brazil in 2019, as mirrored in our analysis. However, the general trend of increasing deforestation after 2012 is mirrored not only in the news discourse but also by an increasing attention toward illegal logging in the scientific and NGOs/IOs discourses, indicated by a larger number of articles on the topic in the observation period.

The clear focus on the extraction phase of the wood supply chain is another similarity across the discourse. This focus on one particular sequence of illegal logging activities is surprising considering the broad range of illegal activities identified in earlier reports (Hoare, 2015; Tacconi et al., 2016). A broadened perspective including activities other than felling trees and harvesting forests can only be found in the NGOs/IOs discourse.

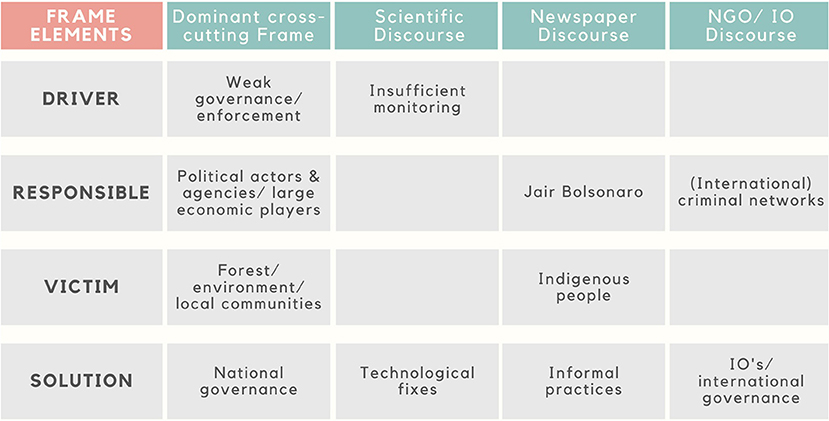

A further analysis of the diagnostic and prognostic frames uncovered a dominant cross-cutting frame of illegal logging in Brazil and at the same time identified elements that are particularly highlighted in specific discourses (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Dominant, cross-cutting frames and elements of specific frames highlighted in the different discourses (source: own inquiry).

The general frame focuses on the violation of ownership rights, specifically indigenous peoples' ownership rights, based on weak national governance, with forest and the environment at large depicted as suffering from illegal logging. Despite being presented as responsible parties, political actors and institutions are also portrayed as being those who are in a position to respond to the problem at the national level. This general dominant frame underlies all three discourses, even though each discourse has its own emphasis.

The scientific discourse has a particular focus on the weak enforcement of governance and points to monitoring systems as a possible solution. Accordingly, more often than in other discourses, the scientific discourse presents technological fixes as a way to overcome weak enforcement, e.g., by new remote sensing techniques.

The newspaper discourse, instead, strongly supports the portrayal of indigenous people as the victim of illegal logging (a criminal act accompanied by violence) and sometimes depicts them as solvers of the problem who try to prevent deforestation by means of informal practices. The newspaper discourse also clearly identifies the new government, and Bolsonaro in particular, as those who are to be considered responsible of the situation in the last few years.

Boundaries between the scientific and the NGOs/IOs discourses are blurred, with the latter comprising scientific analysis as well. However, a difference becomes obvious when it comes to the scope of governance. The NGOs/IOs discourse partly uses a broader frame as it emphasizes (international) criminal networks as culprits. Accordingly, finding a solution to the problem is not described as being only in the hands of national governmental policies but also pertains to governance beyond the nation state, and more specifically to IOs.

These results show a general frame of illegal logging and governance responses, contextualizing the specific discourses. In the literature on framing, this kind of generic and inclusive frame is called a “master frame” (Snow and Benford, 1992). In the context of social movements, master frames are described as “more flexible modes of interpretation, and as a consequence, they are more inclusive systems that allow for extensive ideational amplification and extensive, elastic, flexible, and inclusive enough so that any number of other social movements can successfully adopt and deploy it in their campaign” (Snow and Benford, 1992: 140). Even though the different discourses that form the subject of this paper are not social movements, an adoption of the generic frame can be observed.

The literature on master frames has identified the frame of environmental justice, combining injustice against humans and environmentalism in one frame (Taylor, 2012). The dominant frame identified in the three discourses matches the master frame of environmental justice as referring to indigenous people rights and the victimization of forests and the environment at large. The identified frames point toward the unequal impact of illegal logging confronting indigenous people with a higher burden than others. This master frame is reflected in the problem definition of the discourses in particular pointing toward illegal logging in the area of indigenous territories and the violation of the rights of indigenous people. In combination with the identification of power asymmetries between politicial actors and economic players at the one side and indigenous people at the other the question of justice is strongly combined with the problem of environmental harm suggesting that both are inseparable (Taylor, 2012). Some articles mainly focus on environmental justice though taking on different lenses, e.g., on the consequences of illegal logging of mafia networks for indigenous people (Teixeira et al., 2018) or in scientific but as well NGO and newspaper articles on the violence resulting from illegal logging activities (Uribe, 2013; Greenpeace Brasil, 2017; Celentano et al., 2018). This master frame also extends usual environmental frames by targeting people who are normally not included in environmental movements (Uribe, 2013; Greenpeace Brasil, 2017; Celentano et al., 2018). Furthermore, the master frame resonates with the environmental paradigm of the time.

Within this master frame of environmental justice, the different discourses place emphasis on adapting to their own institutional logics, determining how an issue is framed more specifically.

The media logic is well-researched (e.g., Berglez et al., 2009; Berglez, 2011). The media needs to frame illegal logging as an issue with high news value to gain the attention of a large audience. The emphasis on the illegal logging discourse supports this news value, as humans are presented as being threatened and those victims are characterized as much as possible in order to trigger empathy and other emotions (for the example of climate change see Weingart et al., 2000). Similarly, the communication logic of NGOs is expected to frame issues to gain the attention of the general public, generate funding, and mobilize people by making use of emotions (Anspach and Dragulijic, 2019). In contrast, IOs and scientific discourses are expected to present an objective description of the problem and provide constructive solutions (Weingart et al., 2000). Through the process of framing, these different discourses make a “normative leap” (Schön and Rein, 1994: 26) by proposing their own formulation of the problem and their own preferred solutions substantiated by their own stories and catering to their own institutional logics. The impact of this institutional embedding on the way of framing issues has been already acknowledged in earlier studies of framing (Schön and Rein, 1994: 26).

Another clear result of the analysis of the discourses on illegal logging in Brazil is the central role of national governance, being equally part of the problem and of the solution. This result has to be interpreted with caution, given that “Brazil” is the key selection criteria for the analyzed material. However, even though the focus of this analysis on discourses and frames around the new FC in Brazil presumes a strong national focus, the weakness of national governance and enforcement detected within the discourse could have resulted in a shift of perspective toward governance beyond the nation state. All the more so, as the trend of the scientific international forest debate becomes increasingly international and moves toward legality verification, including market-based instruments and consumer driven policies like FLEGT, EUTR, Lacey Act, or certification systems (e.g., Cashore and Stone, 2012; Maryudi, 2016; Wibowo et al., 2019). Instead, the analyzed discourses frame governance mainly as national, with the exception of the NGOs/IOs discourse, which however still deals with central governmental authorities and command and control instruments. Other frame analyses argue that the national perspective of media frames result from the national logic of media (Olausson, 2009). However, in our analysis we have analyzed media from different countries, therefore it would have made sense to find different national logics.

First, the analysis of frames of illegal logging and governance responses in Brazil in the scientific discourse, the media discourse, and the NGOs/IOs discourse has identified that differences of frames correspond to the institutional logic of the discourse. For example, a strong focus on human threats and humanization to support emotional reporting in the media, frames concentrating on technological fixes in the scientific discourse, and a more central role of IOs in the NGOs/IOs discourse. Despite these specific perspectives that give precedence to certain aspects over others, these frames are all embedded in the general master frame of environmental justice.

Second, other results show the strong national character of the discourse as well as the continued focus on command and control instruments, e.g., pointing toward the enforcement of existing regulations while anticipating the lively and creative debate of new governance mechanisms only to a minor degree. These results might indicate that the internationalization of the legality verification debate has only been taken up to a minor degree when discussing specific national problems like illegal logging in Brazil. The results can also be a reflection of the fact that most of the (illegally) harvested timber remains in the domestic market of Brazil (ITTO, 2017). This could then be a research gap that can be addressed in the future, or it can be concluded that international forest governance studies are taken up less in domestic studies and considerations.

Third, but still related to the second result, the results indicate a narrow focus on only one aspect of illegal logging, namely the extraction of wood, and a disregard for other illegal activities around illegal logging, despite the attempts of the NGOs/IOs discourse to raise awareness on a broader spectrum of illegal logging activities.

Finally, it is important to point out that the empirical design of this paper comes with certain limitations. The selection of scientific articles, media article, and NGOs/IOs programmes, respectively has been carried out following different selection criteria: the results can therefore only be compared to with caution. The time limit of the observation period (which ends in mid-2020) makes it difficult to see scientific articles covering the governmental change in 2019, even though this could be an event that has the power to change the scientific discourse as well. Therefore, we suggest to broaden the time period of analysis in future studies on the scientific discourse on illegal logging in Brazil, starting before 2012 in order to cover a possible change in discourse following the trend of the deforestation rate and ending as late as possible to include literature that takes into account the governmental change in 2019.

Despite these empirical limitations, the frame analysis based on social movement theories has proven to be a fruitful theoretical framework for organizing a review of scientific and other discourses, even though social movements have not been a central object of analysis. This paper contributes to the literature of illegal logging by starting from an interpretative approach. It shows differences between the discourses as well as the master frame of environmental justice informing all discourses.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

DK: concept, interpretation, and writing. RF: category system, data collection, and data analysis. LW: data collection. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The article processing charge was funded by the Baden-Wuerttemberg Ministry of Science, Research and Art and the University of Freiburg in the funding programme Open Access Publishing.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/ffgc.2021.624072/full#supplementary-material

Adelman, S. (2015). Tropical forests and climate change: a critique of green governmentality. Int. J. Law Context 11, 195–212. doi: 10.1017/S1744552315000075

Amaral, A. C. (May 20, 2020). Exército ignora Ibama, mobiliza 97 agentes e faz vistoria sem punição. Folha de São Paulo.

Amazon Watch (2019). “Complicity in destruction ii: how northern consumers and financiers enable Bolsonaro's assault on the Brazilian Amazon” in Amazon Watch (Washington, DC).

Anspach, N. M., and Dragulijic, G. (2019). Effective advocacy: the psychological mechansims of environmental issue framing. Environ. Politics 28, 615–638. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2019.1565468

Arts, B., Appelstrand, M., Kleinschmit, D., Pülzl, H., Visseren-Hamakers, I., Eba'a Atyi, R., et al. (2010). “Discourses, actors and instruments in international forest governance,” in Embracing Complexity: Meeting the Challenges of International Forest Governance, eds J. Rayner, A. Buck, and P. Katila (Vienna: IUFRO World Series vol 28), 57–73.

Azevedo, A. A., Rajão, R., Costa, M. A., Stabile, M. C. C., Macedo, M. N., dos Reis, T. N. P., et al. (2017). Limits of Brazil's Forest Code as a means to end illegal deforestation. PNAS 114, 7653–7658. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1604768114

Azevedo-Ramos, C., Silva, J. N. M., and Merry, F. (2015). The evolution of Brazilian forest concessions. Elem. Sci. Anth. 3:48. doi: 10.12952/journal.elementa.000048

Balbinotto Neto, G., Tillmann, E. A., and Ratnieks, I. (2012). “Regulation and moral hazard in forest concessions in Brazil,” in ALACDE (Berkeley).

Benford, R. D., and Snow, D. A. (2000). Framing processes and social movements: an overview and assessment. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 26, 611–639. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.611

Bento, J., Ferreira, D. S., and Poschen, P. (2019). About trees and people. what works for development, employment and the environment in the Brazilian Amazon? REB 6, 109–121. doi: 10.14201/reb2019611109121

Berglez, P. (2011). Inside, outside, and beyond media logic: journalistic creativity in climate reporting. Media Cult. Soc. 33, 449–465. doi: 10.1177/0163443710394903

Berglez, P., Höijer, B., and Olausson, U. (2009). “Individualisation and nationalisation of the climate issue. Two ideological horizons in Swedish news media,” in Climate Change in the Media, eds T. Boyce and L. Lewis (New York, NY: Peter Lang), 211–223.

Bisschop, L. (2012). Out of the Woods: the illegal trade in tropical timber and a European trade hub. Glob. Crime 13, 191–212. doi: 10.1080/17440572.2012.701836

Boucher, D. (2014). How Brazil has dramatically reduced tropical deforestation. Solutions 5, 66–75. Available online at: http://thesolutionsjournal.org/node/237165

Boucher, D., Roquemore, S., and Fitzhugh, E. (2013). Brazil's success in reducing deforestation. Trop. Conserv. Sci. 6, 426–445. doi: 10.1177/194008291300600308

Brancalion, P. H. S., de Almeida, D. R. A., Vidal, E., Molin, P. G., Sontag, V. E., Souza, S. E. X. F., et al. (2018). Fake legal logging in the Brazilian Amazon. Sci. Adv. 4:1192. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aat1192

Bueno, G., and Cashore, B. (2013). “Can legality verification combat illegal logging in Brazil? Strategic insights for policy makers and advocates,” in IUFRO Task Force on Forest Governance (Vienna).

Carvalho, A. V., Silva, F. M., Carvalho, R. A. F., Guimaraes, J. L. C., Carvalho, A. C., Almeida, R. M., et al. (2018). Legislação ambiental e economia do crime na BR-163 e PA-370: análise do mercado madeireiro illegal. RICA 9, 391–408. doi: 10.6008/CBPC2179-6858.2018.006.0036

Carvalho, W. D., Mustin, K., Hilário, R. R., Vasconcelos, I. M., Eilers, V., and Fearnside, M. (2019). Deforestation control in the Brazilian Amazon: a conservation struggle being lost as agreements and regulations are subverted and bypassed. PECON 17, 122–130. doi: 10.1016/j.pecon.2019.06.002

Cashore, B., and Stone, M. (2012). Can legality verification rescue global forest governance?: Analyzing the potential of public and private policy intersection to ameliorate forest challenges in Southeast Asia. Forest Policy Econ. 18, 13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2011.12.005

Celentano, D., Miranda, M. V. C., Mendonça, E. N., Rousseau, G. X., Muniz, F. H., Loch, V. C., et al. (2018). Desmatamento, degradação e violência no “Mosaico Gurupi” – A região mais ameaçada da Amazônia. Estud. Avançados 32:20180021. doi: 10.5935/0103-4014.20180021

Charity, S., Dudley, N., Oliveira, D., and Stolton, S. (2016). Relatório Amazônia Viva 2016: uma abordagem regional à conservação da Amazônia Sumário Executivo. WWF Iniciativa Amazônia Viva. Brasília: Brazil and Quito: Ecuador.

Chules, E. L., Scardua, F. P., and Martins, R. C. C. (2018). Desafios da implementação da política de concessões florestais federais no Brasil. Rev. Direito Econ. Socioambiental 9, 295–318. doi: 10.7213/rev.dir.econ.soc.v9i1.18351

Condé, T. M., Higuchi, N., and Lima, A. J. N. (2019). Illegal selective logging and forest fires in the Northern Brazilian Amazon. Forests 10:61. doi: 10.3390/f10010061

Dantas Chaves, M. E., and de Carvalho Alves, M. (2019). Recent applications of the MODIS sensor for soybean crop monitoring and deforestation detection in Mato Grosso, Brazil. CAB Reviews 14:7. doi: 10.1079/PAVSNNR201914007

De Antoni, G. (2010). Pilot program for tropical forest protection in Brazil (PPG-7) and the globalization of the Amazon. Ambiente Sociedade 13, 299–313. doi: 10.1590/S1414-753X2010000200006

Dryzek, J. S. (1997). The Politics of Earth: Environmental Discourses. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Fischermann, T. (November 18, 2019). Vormarsch der Kettensägen; Die Abholzung im brasilianischen Amazonasgebiet ist politisch gewollt. Nun könnte sich ausgerechnet das mächtige Agrobusiness dagegenstemmen. DIE ZEIT 49, 35.

Fischermann, T., and Lichterbeck, P. (November 27, 2014). DER KAMPF UM DIE LUNGE DER WELT. Weiße Holzfäller zerstören den Amazonaswald. Wie drei Indianerstämme versuchen, sie daran zu hindern. DIE ZEIT 49, 48–57.

Goffman, E. (1974). Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience. New York, NY: Harper Colophon.

Government of Brazil (2007). Plano Nacional sobre Mudança do Clima. Available online at: https://www.mma.gov.br/clima/politica-nacional-sobre-mudanca-do-clima/plano-nacional-sobre-mudanca-do-clima.html (accessed October 09, 2020).

Greenpeace (2018). “IMAGINARY TREES, REAL DESTRAUCTION. How licensing fraud and illegal logging of IPE trees are causing irreversible damage to the Amazon rainforest,” in Greenpeace (São Paulo).

Hoare, A. (2015). Tackling Illegal logging and the Related Trade: What Progress and Where next? London: Chatham House.

INPE (2020a). Monitoramento do Desmatamento da Floresta Amazônica Brasileira por Satélite. Available online at: http://www.obt.inpe.br/OBT/assuntos/programas/amazonia/prodes (accessed October, 09, 2020).

INPE (2020b). TerraBrasilis. PRODES-Desmatamento. Available online at: http://terrabrasilis.dpi.inpe.br/app/dashboard/deforestation/biomes/legal_amazon/rates (accessed March, 08, 2021).

ITTO (2017). Review and Assessment of the World Timber Situation. Available online at: https://www.itto.int/annual_review/ (assessed April, 23, 2021).

Kleinschmit, D., Mansourian, S., Wildburger, C., and Purret, A. (2016). Illegal Logging and Related Timber Trade - Dimensions, Drivers, Impacts and Responses. A Global Scientific Rapid Response Assessment Report, Vol. 35. IUFRO World Series. Vienna.

Kröger, M. (2017). Inter-sectoral determinants of forest policy: the power of deforesting actors in post-2012 Brazil. Forest Policy Econ. 77, 24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2016.06.003

Kröger, M. (2020). Field research notes on Amazon deforestation during the Bolsonaro era. Globalizations 17, 1080–1083. doi: 10.1080/14747731.2020.1763063

Lawson, S. (2014). Consumer Goods and Deforestation. An Analysis of the Extent and Nature of Illegality in Forest Conversion for Agriculture and Timber Plantation. Washington, DC: Forest Trends.

Londono, E. (November 14, 2018). As Brazil's far right leader threatens the Amazon, one tribe pushes back. The New York Times - International Edition.

Maryudi, A. (2016). Choosing timber legality verification as a policy instrument to combat illegal logging in Indonesia. Forest Policy Econ. 6, 99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2015.10.010

McDermott, C. L., Irland, L. C., and Pacheco, P. (2014). Forest certification and legality initiatives in the Brazilian Amazon: Lessons for effective and equitable forest governance. For. Policy Econ. 50, 134–142. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2014.05.011

MMA (2019). Plano de Ação para Prevenção e Controle do Desmatamento na Amazônia Legal. Available online at: https://www.mma.gov.br/informma/item/616-prevenção-e-controle-do-desmatamento-na-amazônia (accessed August 10, 2020).

Moriyama, V., and Sandy, M. (December 10, 2019). ‘The Amazon is completely lawless:' the rainforest after Bolsonaro's first year. The New York Times - International Edition.

Muniz, T. F., and Pinheiro, A. S. O. (2019). Concessão florestal como instrumento para redução de exploração ilegal madeireira em Unidades de Conservação em Rondônia. Revista Farol 8, 121–142. Available online at: http://www.revistafarol.com.br/index.php/farol/article/view/123

Nepstad, D., McGrath, D., Stickler, C., Alencar, A., Azevedo, A., Swette, B., et al. (2014). Slowing Amazon deforestation through public policy and interventions in beef and soy supply chains. Science 344, 1118–1123. doi: 10.1126/science.1248525

Olausson, U. (2009). Global warming–global responsibility? Media frames of collective action and scientific certainty. Public Understand. Sci. 18, 421–436. doi: 10.1177/0963662507081242

Paiva, P. F. P. R., de Lourdes Pinheiro Ruivo, M., Marques da Silva Júnior, O., de Nazaré Martins Maciel, M., Braga, T. G. M., de Andrade, M. M. N., et al. (2020). Deforestation in protect areas in the Amazon: a threat to biodiversity. Biodivers. Conserv. 29, 19–38. doi: 10.1007/s10531-019-01867-9

Prestes, M. (June 17, 2020). Bacia do Xingu é campeã de desmatamento na Amazônia, diz estudo. Folha de São Paulo

Reboredo, F. (2013). Socio-economic, environmental, and governance impacts of illegal logging. Environ. Syst. Decis. 33, 295–304. doi: 10.1007/s10669-013-9444-7

Roma, J. C., and de Andrade, A. L. C. (2013). Economia, concessões florestais e a exploração sustentável de madeira. Brasília: IPEA.

Santos de Lima, L., Merry, F., Soares-Filho, B., Rodrigues, H. O., dos Santos Damaceno, C., and Bauch, M. A. (2018). Illegal logging as a disincentive to the establishment of a sustainable forest sector in the Amazon. PLoS ONE 13:e0207855. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0207855

Schielein, J., and Börner, J. (2018). Recent transformation of land-use and land-cover dynamics across different deforestation frontiers in the Brazilian Amazon. Land Use Policy 76, 81–94. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.04.052

Schimabukuro, Y. E., Arai, E., Duarte, V., Jorge, A., dos Santos, E. G., Gasparini, K. A. C., et al. (2019). Monitoring deforestation and forest degradation using multi-temporal fraction images derived from Landsat sensor data in the Brazilian Amazon. Int. J. Remote Sens. 40, 5475–5496. doi: 10.1080/01431161.2019.1579943

Schmidt, V. (2015). “Discursive institutionalism. understanding policy in context,” in Handbook of Critical Policy Studies. Handbooks of Research on Public Policy, eds F. Fischer, D. Torgerson, A. Durnová, and M. Orsini (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing), 187–205.

Schön, D., and Rein, M. (1994). Frame Reflection: Toward the Resolution of Intractable Policy Controversies. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Snow, D. A., and Benford, R. D. (1988). Ideology, Frame resonance, and participant mobilization. Int. Soc. Mov. Res. 1, 197–218.

Snow, D. A., and Benford, R. D. (1992). “Master frames and cycles of protest,” in Frontiers in Social Movement Theory, eds A. D. Morris and C. M. Mueller (New Haven: Yale University Press), 133–155.

Soares-Filho, B., Rajao, R., Macedo, M., Carneiro, A., Costa, W., Coe, M., et al. (2014). Cracking Brazil's forest code. Science 344, 363–364. doi: 10.1126/science.1246663

Tacconi, L., Cerutti, P. O., Leipold, S., Rodrigues, R. J., Savaresi, A., To, P., et al. (2016). “Defining illegal forest activities and illegal logging,” in Illegal Logging and Related Timber Trade – Dimensions, Drivers, Impacts and Responses. A Global Scientific Rapid Assessment Report, eds D. Kleinschmit, S. Mansourian, C. Wildburger, and A. Purret (Vienna: IUFRO), 23–35.

Tacconi, L., Rodrigues, R. J., and Maryudi, A. (2019). Law enforcement and deforestation: lessons for Indonesia from Brazil. For. Policy Econ. 108:101943. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2019.05.029

Taylor, D. E. (2012). The Rise of the environmental justice paradigm – injustice framing and the social construction of environmental discourses. Am. Behav. Sci. 43, 508–580. doi: 10.1177/00027640021955432

Teixeira, M. A. D., Lima, R. M., and Ferreira, J. C. S. (2018). Crimes Verdes e Colarinho Branco- a mafia da madeira na Amazônia Ocidental, uma violação aos direitos humanos. Quaestio Iuris 11, 3148–3172. doi: 10.12957/rqi.2018.37444

Tritsch, I., Sist, P., da Silva Narves, I., Mazzei, L., Blanc, L., Bourgoin, C., et al. (2016). Multiple patterns of forest disturbance and logging shape forest landscapes in Paragominas, Brazil. Forests 7:315. doi: 10.3390/f7120315

UN Environment and UNEP-WCMC (2018). “Brazil; country overview to aid implementation of the EUTR,” in UN environment and UNEP-WCMC.

UNEP and Interpol (2012). “Green carbon, black trade,” in Illegal Logging, Tax Fraud and Laundering in the World's Tropical Forests. A Rapid Response Assessment, ed C. Nellemann (Arendal: INTERPOL Environmental Crime Programme (UN Environment and UNEP-WCMC)), p. 67.

Van den Brink, M., and Metze, T. (2006). “Words matter in policy and planning,” in Words Matter in Policy and Planning: Discourse Theory and Method in the Social Sciences, eds M. van den Brink and T. Metze (Utrecht: KNAG/NETHUR), 13–20.

Van Hulst, M., and Yanow, D. (2016). From policy “frames” to “framing”: theorizing a more dynamic, political approach. Amer. Rev. Public Administr. 46, 92–112. doi: 10.1177/0275074014533142

Viscidi, L., and Ortiz, E. (July 22, 2019). How to save the amazon rain forest. The New York Times - International Edition.

Waldhoff, P., and Vidal, E. (2015). Community loggers attempting to legalize traditional timber harvesting in the Brazilian Amazon: an endless path. For. Policy Econ. 50, 311–318. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2014.08.005

Weingart, P., Engels, A., and Pansegrau, P. (2000). Risks of communication: discourses on climate change in science, politics and the mass media. Public Underst. Sci. 9, 261–283. doi: 10.1088/0963-6625/9/3/304

Keywords: illegal logging, Brazil, deforestation, master frame, environmental justice, collective action frame

Citation: Kleinschmit D, Ferraz Ziegert R and Walther L (2021) Framing Illegal Logging and Its Governance Responses in Brazil – A Structured Review of Diagnosis and Prognosis. Front. For. Glob. Change 4:624072. doi: 10.3389/ffgc.2021.624072

Received: 30 October 2020; Accepted: 27 April 2021;

Published: 25 May 2021.

Edited by:

Claudia Azevedo-Ramos, Federal University of Pará, BrazilReviewed by:

Celso H. L. Silva Junior, National Institute of Space Research (INPE), BrazilCopyright © 2021 Kleinschmit, Ferraz Ziegert and Walther. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Daniela Kleinschmit, ZGFuaWVsYS5rbGVpbnNjaG1pdEBpZnAudW5pLWZyZWlidXJnLmRl

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.