A Commentary on

No evidence for language syntax in songbird vocalizations

By Beckers GJL, Huybregts MAC, Everaert MBH and Bolhuis JJ (2024). Front. Psychol. 15:1393895. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1393895

1 Introduction

It has been hypothesized that the generative power of language stems from a cognitive capacity called “Merge,” which enables senders to combine two linguistic items (e.g., two words or two phrases) into a sequence and receivers to recognize it as a single unit (Chomsky, 1995, 2001). In an experimental study published in Nature Communications (Suzuki and Matsumoto, 2022), we demonstrated that a bird species, the Japanese tit (Parus minor), has evolved “core-Merge,” the most fundamental form of Merge that combines two words into a single unit (Fujita, 2009, 2014). In their recent publication in Frontiers in Psychology, Beckers et al. (2024) raised concerns about the interpretation of our results. However, after careful consideration, we maintain the conclusion that our results provide evidence for core-Merge.

2 Suzuki and Matsumoto (2022)

Japanese tits produce alert calls when warning conspecifics about danger, such as the presence of predators, while they produce acoustically distinct recruitment calls when attracting others to non-dangerous situations, such as food locations or during nest visitations (Suzuki, 2014; Suzuki et al., 2016). They often combine these call types into ordered sequences (alert-recruitment call sequences) when gathering other individuals to approach and harass (i.e., mob) a predator (Suzuki, 2014; Suzuki and Matsumoto, 2022). Previous experiments showed that tits display different behaviours when hearing alert calls (moving their head horizontally as if scanning for danger) and recruitment calls (approaching the sound source) (Suzuki et al., 2016). In response to alert-recruitment call sequences, tits progressively approach the sound source while continuously scanning the horizon, suggesting that they detect compound information (i.e., “alert” + “approach”) (Suzuki et al., 2016).

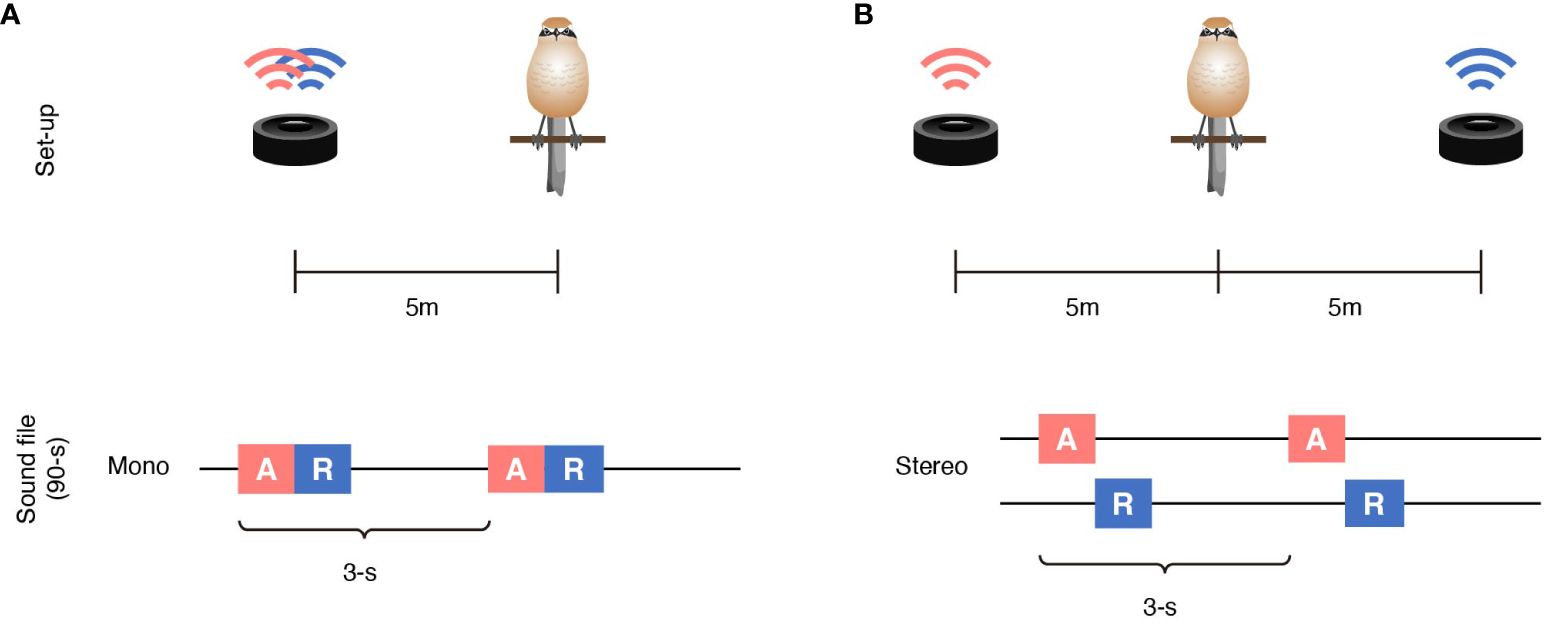

There are two possible explanations for the bird’s responses to alert-recruitment call sequences. One possibility is that receiver tits recognize an alert-recruitment call sequence as a single unit (i.e., core-Merge) and extract a compound meaning. The other possibility is that tits perceive the two-call sequence as two individual calls that are arbitrarily produced in close time proximity, not as a single unit, and then extract both meanings. If tits recognize an alert-recruitment call sequence as a single unit, then they are expected to exhibit appropriate responses to alert-recruitment calls given by a single individual; however, they should not perceive the same information when alert calls and recruitment calls are separately produced by two individuals with the same timing (see Suzuki and Matsumoto, 2022). To test this, we exposed flocks of Japanese tits to a taxidermic specimen of predator (bull-headed shrike) during playback of (i) alert-recruitment call sequences broadcast from a single speaker (1AR) or (ii) alert and recruitment calls broadcast from two speakers in turn, following the alert-recruitment order (2AR) (Figure 1, see also Suzuki and Matsumoto, 2022).

Figure 1 Schematic representation of the experimental design by Suzuki and Matsumoto (2022). If an animal uses core-Merge for recognizing call sequences, it should be capable of assessing whether the component calls originate from a single individual. Japanese tits were exposed to a shrike specimen (a predator specimen) along with playback stimuli: (A) alert calls and recruitment calls were broadcast from one speaker as temporally linked, alert-recruitment sequences; (B) the same two calls were broadcast from two speakers while maintaining temporal linkage. This figure was partially adapted from Suzuki and Matsumoto (2022).

We found that Japanese tits approach and harass a predator specimen when perceiving alert-recruitment call sequences played from a single source, but not from two sources (Suzuki and Matsumoto, 2022). Therefore, we concluded that tits perceive an alert-recruitment call sequence as a single unit, providing evidence for core-Merge.

3 Interpretation

The main criticism raised by Beckers et al. (2024) is that simply recognizing two calls as a single unit does not provide evidence for core-Merge. However, this is due to a misunderstanding of the definition of core-Merge. According to Fujita (2014), core-Merge is “the simple binary combinatorial device that concatenates two syntactic atoms (lexical items) into a set.” In other words, core-Merge does not lead to a structure with endocentricity, but does construct a simple concatenation of two meaning-bearing units (e.g., a + dog = {a dog}) (Fujita, 2009, 2014). Thus, for animal studies, core-Merge could be defined as a capacity which allows senders to combine two meaning-bearing calls into a sequence and receivers to recognize it as a single unit (Suzuki and Matsumoto, 2022). If an animal species perceives a two-call sequence produced by a single individual as a single unit (or a single utterance which is both spatially and temporally linked), this should provide evidence for core-Merge. Therefore, according to the definition of core-Merge, Beckers et al. (2024)’s statement that “we agree that the experiment shows that 1AR can be seen as one utterance, contrary to 2AR” supports our conclusion as it is.

Beckers et al. (2024) also argue that the results of Suzuki and Matsumoto (2022) are inconsistent with those of Suzuki et al. (2017), which demonstrated that Japanese tits respond to novel call sequences comprising conspecific alert calls and heterospecific recruitment calls (synonymous with their own recruitment calls, produced by the members of mixed-species flocks to maintain flock cohesion) only when these calls are combined into alert-recruitment ordering. However, their claim is based on the unfounded assumption that Japanese tits should recognize two calls from different species as two separate utterances even if the two calls are spatially and temporally linked (see also Schlenker et al., 2023). No study has tested this assumption. It might be possible that tits recognize sequences of conspecific and heterospecific calls as a single unit produced by the same individual when the two calls are produced from the same spatial location in a temporally linked manner.

In Suzuki and Matsumoto (2022), there was no significant difference in receivers’ responses to the playback of call sequences comprising alert and recruitment calls from the same individual compared to the playback of call sequences comprising alert and recruitment calls from different individuals. These results indicate that, when extracting information from call sequences, Japanese tits rely more on the spatial and temporal linkage of the two meaning-bearing calls rather than on individual-based variation in the acoustic structure of each component call. Future experiments are required to clarify how Japanese tit receivers recognize mixed-species novel call sequences; however, regardless of the outcomes, the Suzuki and Matsumoto (2022)’s conclusion that receivers recognize 1AR (a sequence of conspecific calls) as a single unit should remain unchanged.

4 Discussion

In our paper, we introduced the existence of two conflicting theories for the origins of language’s productivity (Suzuki and Matsumoto, 2022). One theory holds that Merge is an atomic and primitive capacity, enabling us to produce and comprehend any kind of word combinations, including complex expressions with hierarchical structure (e.g., a + dog + barks = {a dog} + barks = {{a dog} barks}) (Bolhuis et al., 2014; Berwick and Chomsky, 2019). The second theory holds that such complex expressions require at least two capacities: a capacity for combining words (core-Merge or Merge: (α, β) ⇒ {α, β}) and another capacity for its recursive application (Fujita, 2009, 2014; Boeckx, 2009; Hornstein, 2009; Fukui, 2011; Rizzi, 2016; Suzuki et al., 2019). Although the terminology for such a recursive applicability has not been settled [e.g., “Copy” (Boeckx, 2009), “Label” (Hornstein, 2009), “Embed” (Fukui, 2011)], it envisages taking an already merged unit and one of its members, combining them to form a set union, and turning it into another unit to which the core-Merge can apply again ({α, β} ⇒ {γ, {α, β}}, where γ = α or β) (Fujita, 2009, 2014). In this theory, it is expected that without recursion, Merge (or core-Merge) merely serves to combine two linguistic items into a set.

Our findings at least support this second theory, as Japanese tits combine two call types into a single unit. Although Japanese tits often produce call sequences comprising more than two types of notes (Suzuki, 2014), it remains unknown whether such complex sequences involve more than two meaning-bearing units. However, absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. Future research is necessary to determine if Japanese tits combine more than two meaning-bearing calls into hierarchically structured sequences. Therefore, we introduced the two theories in our paper without insisting on a specific trajectory of language evolution (Suzuki and Matsumoto, 2022).

While Beckers et al. (2024) stated “we do not agree, therefore, with their claim that core-Merge explains the increase in the repertoire of vocalizations, or with their suggestion that such call combinations could be the first step toward hierarchically structured expressions,” we never made such claims in our paper (see Suzuki and Matsumoto, 2022). Instead, we concluded that “determining how widely Merge is involved in animal signals and what specific mechanisms provide the basis for the emergence of hierarchical structure remains a key challenge in animal communication research” (Suzuki and Matsumoto, 2022). Thus, we believe that Beckers et al. (2024)’s claim overlooks the focus of our paper which tests whether birds have a capacity to recognize a two-call sequence as a single unit (i.e., core-Merge).

In conclusion, Beckers et al. (2024)’s criticisms do not change interpretations or conclusion of Suzuki and Matsumoto (2022) in any way. Their argument appears to be heavily influenced by their own perspective on “no half-Merge.” Even the title “No evidence for language syntax in songbird vocalizations” appears unsuitable as a counterargument to our previous study (Suzuki and Matsumoto, 2022); we strictly defined the term “core-Merge” in our paper and never used or defined the term “language syntax” or even “syntax.” In linguistic literature, “core-Merge” (or “Merge”) and “syntax” are used with distinct meanings. We believe that explicitly defining terms is essential for advancing interdisciplinary research.

Author contributions

TS: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YM: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by JST FOREST Program (Grant Number JPMJFR2149 to TS).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Beckers G. J. L., Huybregts M. A. C., Everaert M. B. H., Bolhuis J. J. (2024). No evidence for language syntax in songbird vocalizations. Front. Psychol. 15, 1393895. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1393895

Berwick R. C., Chomsky N. (2019). All or nothing: No half-Merge and the evolution of syntax. PloS Biol. 17, e3000539. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000539

Boeckx C. (2009). “The Nature of Merge: Consequences for Language, Mind, and Biology,” in Of Minds & Language: A Dialogue with Noam Chomsky in the Basque Country. Eds. Piattelli-Palmarini M., Uriagereka J., Salaburu P. (Oxford University Press, Oxford), 44–57.

Bolhuis J. J., Tattersall I., Chomsky N., Berwick R. C. (2014). How could language have evolved? PloS Biol. 12, e1001934. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001934

Chomsky N. (2001). “Derivation by Phase,” in Ken Hale: A Life in Language. Ed. Kenstowicz M. (MA MIT Press, Cambridge), 1–52.

Fujita K. (2009). A prospect for evolutionary adequacy: Merge and the evolution and development of human language. Biolinguistics 3, 128–153. doi: 10.5964/bioling.v3i2-3

Fujita K. (2014). “Recursive Merge and Human Language Evolution,” in Recursion: Complexity in Cognition. Eds. Roeper T., Speas M. (Springer, New York), 243–264.

Fukui N. (2011). “Merge and Bare Phrase Structure,” in The Oxford handbook of linguistic minimalism. Ed. Boeckx C. (Oxford University Press, Oxford), 73–95.

Hornstein N. (2009). A Theory of Syntax: Minimal Operations and Universal Grammar (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press). doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511575129

Rizzi L. (2016). Monkey morpho-syntax and merge-based systems. Theor. Linguist. 42, 139–145. doi: 10.1515/tl-2016-0006

Schlenker P., Coye C., Leroux M., Chemla E. (2023). The ABC-D of animal linguistics: Are syntax and compositionality for real? Biol. Rev. 98, 1142–1159. doi: 10.1111/brv.12944

Suzuki T. N. (2014). Communication about predator type by a bird using discrete, graded and combinatorial variation in alarm calls. Anim. Behav. 87, 59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2013.10.009

Suzuki T. N., Matsumoto Y. K. (2022). Experimental evidence for core-Merge in the vocal communication system of a wild passerine. Nat. Commun. 13, 5605. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-33360-3

Suzuki T. N., Wheatcroft D., Griesser M. (2016). Experimental evidence for compositional syntax in bird calls. Nat. Commun. 7, 10986. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10986

Suzuki T. N., Wheatcroft D., Griesser M. (2017). Wild birds use an ordering rule to decode novel call sequences. Curr. Biol. 27, 2331–2336. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.06.031

Keywords: birds, call combinations, core-Merge, merge, language evolution

Citation: Suzuki TN and Matsumoto YK (2024) Commentary: No evidence for language syntax in songbird vocalizations. Front. Ecol. Evol. 12:1430848. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2024.1430848

Received: 10 May 2024; Accepted: 09 July 2024;

Published: 23 July 2024.

Edited by:

Sang-im Lee, Daegu Gyeongbuk Institute of Science and Technology (DGIST), Republic of KoreaReviewed by:

Jungmoon Ha, Seoul National University, Republic of KoreaCopyright © 2024 Suzuki and Matsumoto. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Toshitaka N. Suzuki, dG9zaGl0YWthc3V6dWtpQGcuZWNjLnUtdG9reW8uYWMuanA=

Toshitaka N. Suzuki

Toshitaka N. Suzuki Yui K. Matsumoto

Yui K. Matsumoto