95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Ecol. Evol. , 21 October 2021

Sec. Behavioral and Evolutionary Ecology

Volume 9 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2021.756476

This article is part of the Research Topic The Development and Fitness Consequences of Sex Roles View all 11 articles

Population sex ratio is a key demographic factor that influences population dynamics and persistence. Sex ratios can vary across ontogeny from embryogenesis to death and yet the conditions that shape changes in sex ratio across ontogeny are poorly understood. Here, we address this issue in amphibians, a clade for which sex ratios are generally understudied in wild populations. Ontogenetic sex ratio variation in amphibians is additionally complicated by the ability of individual tadpoles to develop a phenotypic (gonadal) sex opposite their genotypic sex. Because of sex reversal, the genotypic and phenotypic sex ratios of entire cohorts and populations may also contrast. Understanding proximate mechanisms underlying phenotypic sex ratio variation in amphibians is important given the role they play in population biology research and as model species in eco-toxicological research addressing toxicant impacts on sex ratios. While researchers have presumed that departures from a 50:50 sex ratio are due to sex reversal, sex-biased mortality is an alternative explanation that deserves consideration. Here, we use a molecular sexing approach to track genotypic sex ratio changes from egg mass to metamorphosis in two independent green frog (Rana clamitans) populations by assessing the genotypic sex ratios of multiple developmental stages at each breeding pond. Our findings imply that genotypic sex-biased mortality during tadpole development affects phenotypic sex ratio variation at metamorphosis. We also identified sex reversal in metamorphosing cohorts. However, sex reversal plays a relatively minor and inconsistent role in shaping phenotypic sex ratios across the populations we studied. Although we found that sex-biased mortality influences sex ratios within a population, our study cannot say at this time whether sex-biased mortality is responsible for sex ratio variation across populations. Our results illustrate how multiple processes shape sex ratio variation in wild populations and the value of testing assumptions underlying how we understand sex in wild animal populations.

Sex ratio is a fundamental characteristic of a population capable of affecting its demography and fate (Cotton and Wedekind, 2009; Earl, 2019). In species where gonadal sex is determined by sex chromosomes, Fisher (1930) predicted that sex ratios should be equal at birth, hatching, or metamorphosis. However, observations of sex ratios at early life stages are frequently biased from parity in a variety of species (Hardy, 2002). In mammals and birds, most research on the drivers of early-life sex ratio variation has stressed parental sex allocation – where parents manipulate the sex of their offspring prior to or soon after fertilization by disproportionately allocating resources to a given sex – as a leading mechanism modulating sex ratio in early life stages (Charnov, 1982; West, 2009). However, research in other vertebrates, like many fishes and non-avian reptiles, emphasizes a role for sex determination in shaping offspring sex ratios (Sarre et al., 2004; Ospina-Alvarez and Piferrer, 2008). Sex determination in vertebrates occurs along a spectrum (Sarre et al., 2004). At one end, an organism’s phenotypic sex is controlled entirely by genes (genotypic sex determination) and at the opposite end by environmental conditions like temperature (environmental sex determination). In between these extremes there can be roles for both genetic and environmental factors to contribute to sex determination. Such species can sex reverse, where environmental conditions cause individuals to develop their phenotypic gonadal sex opposite from their genotypic sex (Sarre et al., 2004; Quinn et al., 2007; Ospina-Alvarez and Piferrer, 2008; Alho et al., 2010; Holleley et al., 2015, 2016; Lambert et al., 2019; Miko et al., 2021). In mammals and birds, phenotypic sex is genetically determined whereas fishes and reptiles show a diversity of sex-determining modes, including environmental sex reversal (Bachtrog et al., 2014).

Amphibians have been used as model organisms for over a century to study how environmental conditions influence sex ratios in developing animals (King, 1909, 1910; Witschi, 1929; Wallace and Wallace, 2000; Pettersson and Berg, 2007; Lambert, 2015; Lambert et al., 2016a, 2018; Miko et al., 2021). Sex ratio variation in metamorphosing amphibians is largely assumed to be the result of sex reversal and phenotypic sex ratios at metamorphosis are a proxy of sex reversal in laboratory and field studies (Wallace and Wallace, 2000; Pettersson and Berg, 2007; Papoulias et al., 2013; Lambert, 2015; Lambert et al., 2015, 2018). In such studies, female-biased phenotypic sex ratios are assumed to result from male-to-female sex reversal and male-biased phenotypic sex ratios from female-to-male sex reversal. However, this assumption is rarely tested. Evaluating whether sex ratio variation is due to sex reversal has remained elusive, in large part because genotypically sexing amphibians is notoriously challenging (Alho et al., 2010; Lambert et al., 2016b, 2019; Nemeshazi et al., 2020). Recent genomic advances permit the development of sex-linked molecular markers that allow researchers to genotypically sex large numbers of individual amphibians (Lambert et al., 2016b, 2019; Nemeshazi et al., 2020). Sex-linked markers have recently been used to demonstrate that sex reversal is occurring in wild amphibian populations (Lambert et al., 2016b, 2019; Nemeshazi et al., 2020). Even so, no study has yet to directly evaluate sex reversal as a mechanism underlying phenotypic sex ratio variation.

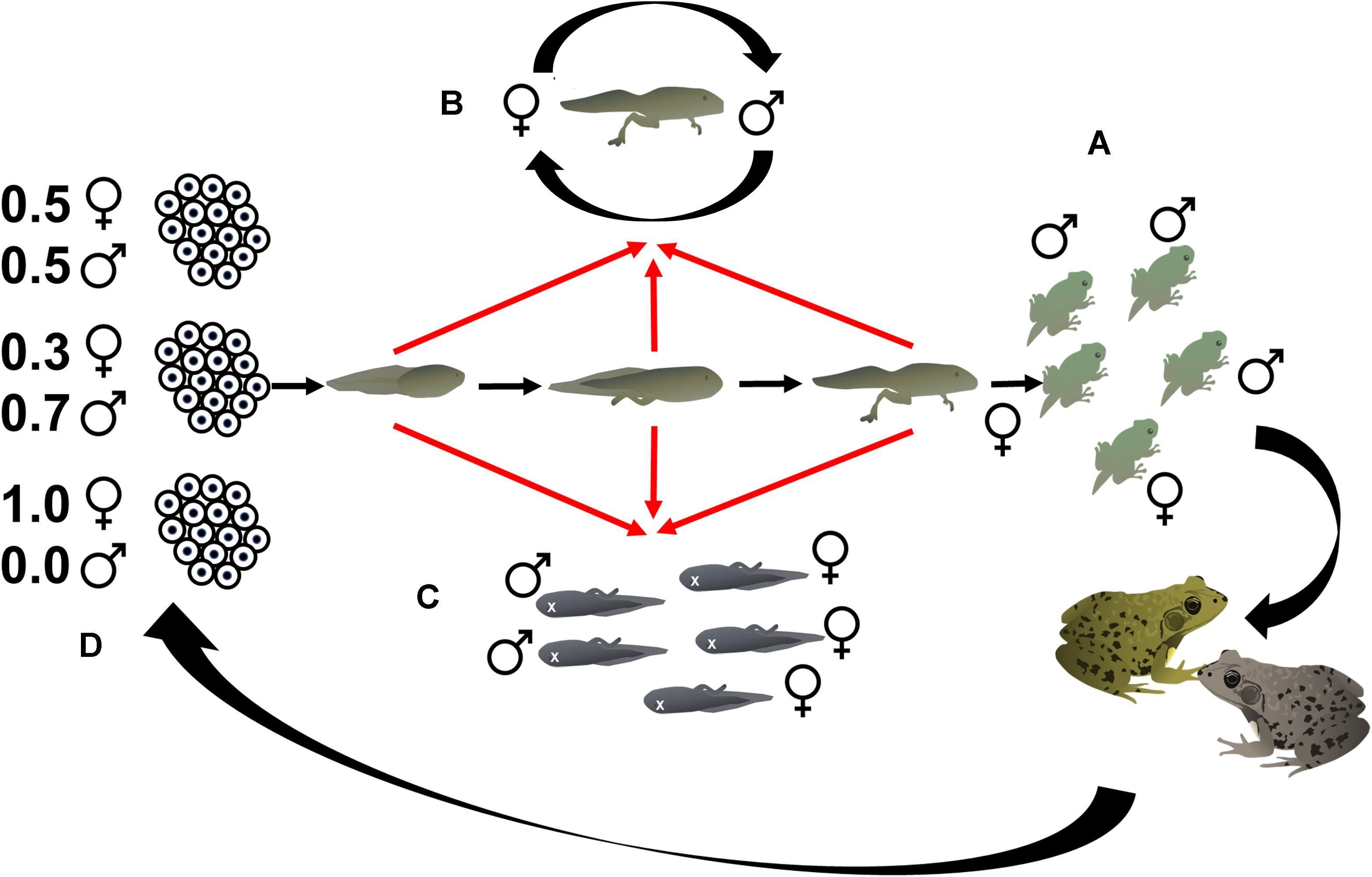

An alternate, and non-exclusive, hypothesis to sex reversal is that amphibian sex ratio variation is driven by sex-biased mortality (Figure 1). Sex-biased mortality prior to birth or hatching has been increasingly observed in wild animal populations, particularly in mammals and birds, but also occasionally in fish (Kruuk et al., 1999; Cichon et al., 2005; Svensson et al., 2007; Orzack et al., 2015; Moran et al., 2016; Kato et al., 2017; Firman, 2019). Multiple factors, including temperature stress and parental condition, have been identified as factors underlying sex-biased mortality, suggesting that sex-biased mortality may not be an adaptive process, as has been suggested for sex allocation, but a maladaptive response to stressful rearing conditions (Kruuk et al., 1999; Goth and Booth, 2005; Eiby et al., 2008; DuRant et al., 2016; Firman, 2019). Thus, sex-biased mortality is important to consider as it can directly shape sex ratios (Szekely et al., 2014).

Figure 1. Phenotypic sex ratios (A) in metamorphosing tadpoles may have contributions from the direct effect of sex reversal as tadpoles develop (B), the effects of genotypic sex-biased mortality (C), and indirect effects of sex reversal whereby sex-reversed adults breed and produce clutches with skewed genotypic sex ratios that bias entire cohort sex ratios (D).

To our knowledge, sex-biased mortality in pre-metamorphic amphibians remains largely unexplored. As with sex reversal, sex-biased mortality has likely remained understudied due to the technical limitations in genotypically sexing amphibians. Only two studies that we are aware of have considered sex-biased mortality in developing amphibians. One study attempted to infer sex-biased mortality by regressing phenotypic sex ratio variation against mortality rates at metamorphosis (Lambert et al., 2016a). This study concluded that sex ratio variation was due to sex reversal and not sex-biased mortality, however, molecular sex data are necessary to better clarify the processes underlying sex ratio variation. Another laboratory experiment found evidence for sex-biased mortality in tadpoles in response to high temperature even though that was not the intention of the study (Miko et al., 2021). Because sex reversal and sex-biased mortality could co-occur, distinguishing the relative contribution of these processes is crucial as both may produce similar phenotypic sex ratios but different genotypic sex ratios which can have implications for the evolutionary ecology and persistence of populations (Cotton and Wedekind, 2009; Earl, 2019).

In this study, we explore sex-biased mortality from embryogenesis to metamorphosis in two natural populations of the Green Frog (Rana clamitans) by sampling the genotypic sex of multiple developmental stages directly from a forested pond and a suburban pond. One of the few studies to assess phenotypic sex ratios in wild metamorphosing amphibians found that metamorphosing R. clamitans tadpole phenotypic sex ratios were male-biased in uncontaminated forest ponds and equal or female-based in suburban ponds that were contaminated by chemicals known to impact sexual differentiation (Lambert et al., 2015). Thus, R. clamitans sex ratio variation could suggest female-to-male sex reversal in natural populations and perhaps male-to-female reversal in environments impacted by suburban pollutants. Subsequent work used a novel molecular sexing approach and found that sex reversal was prevalent across 16 populations of free-living R. clamitans in both forest and suburban ponds and that both female-to-male and male-to-female reversal occur (Lambert et al., 2019). Although this study demonstrated that sex reversal is common in wild R. clamitans, it assessed sex reversal in adult frogs. Because adult R. clamitans populations represent multiple overlapping offspring cohorts, this study could not determine whether sex reversal contributes to sex ratio variation in metamorphosing R. clamitans larvae. Here, our two goals were to (1) document whether sex-biased mortality occurs and alters phenotypic sex ratios and (2) test whether sex reversal is correlated with phenotypic sex ratio variation. We genotype the sex of over 900 R. clamitans across ontogeny from embryo to free-swimming tadpole and metamorphosis, illustrating the important contribution of sex-biased mortality, but secondary and inconsistent effects of sex reversal, on phenotypic sex ratios.

All methods were approved by Yale IACUC protocols 2013-10361 and 2015-10681 and CT DEEP Permit 0116019b.

Our goal was to evaluate the existence of sex-biased mortality in wild R. clamitans cohorts, inferring bias based on changes in genotypic sex ratios across ontogeny from embryogenesis to metamorphosis (Orzack et al., 2015). We sampled genotypic sex ratios at three developmental points: (1) embryogenesis, when clutches are freshly laid in ponds, (2) the free-swimming tadpole stage, multiple months after hatching and prior to overwintering, and (3) at metamorphosis, a developmental stage analogous to birth in mammals or hatching in birds when aquatic tadpoles metabolize their tails and develop all four limbs to become more terrestrial. We sampled two ponds – Septic7 and Forest5 – which have been central to our study of sex research in R. clamitans and which represent ends of a land use spectrum from undeveloped, forested environments (Forest5) and dense, residential suburbs (Septic7; Lambert et al., 2015).

For clutch sampling, we visited the two ponds between 01 June and 12 July, 2017 every 1–3 days to ensure we sampled all new clutches. We note that this period of time does not typically encompass the entire breeding season of the species but, because of drought conditions, we detected few clutches past 26 June, 2017. We saw reduced breeding after this time because water within the two pond basins dried sufficiently below the emergent vegetation at the ponds’ edges that is necessary for R. clamitans to deposit clutches. While this survey period is not as long as it would be in most years, it is comprehensive of the breeding season for this year and allows us to begin addressing the degree of sex ratio variation in R. clamitans clutches and the genotypic sex ratio for the year’s cohorts. From each fresh clutch observed, we collected a subsample of ca. 150 embryos prior to neurulation (Gosner 14 and below), attempting to minimize any environmental effects on embryo survival. This species produces clutches with well over 1,000 embryos and so our samples represent at most 10% of a clutch. Because R. clamitans lays a single-layer film of embryos on the water’s surface, sampling randomly throughout the egg mass is impossible without destroying the entire mass. As such, we haphazardly sampled around each clutch’s periphery in a way that minimized damage to collected embryos or remaining embryos and in a way that did not detach the egg mass from emergent vegetation.

We maintained each clutch in a separate aquarium with reconstituted distilled water at 18°C until embryos freed themselves from jelly which is particularly important for R. clamitans because the jelly coat is too sticky to extract individual embryos without destroying them and collecting embryos singly (Sakisaka et al., 2000; Alho et al., 2010). The assumption in our approach is that the lab hatching accurately reflects the genotypic sex ratios of the clutches when collected in the field. We haphazardly collected 28–30 recently hatched embryos from each clutch, shipped tissue samples to Diversity Arrays Technology (Bruce, ACT, Australia), and genotypically sexed all individuals using DArTmp methods including two rounds of polymerase chain reaction and sequencing on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 using a sex-specific molecular marker for R. clamitans as described previously (Lambert et al., 2016b, 2019). For the sex-specific marker, we used the locus RaclCT001 which has previously been shown to be perfectly linked to genotypic sex, can accurately diagnose sex reversal on its own in the absence of other sex markers, and for which DArTmp methods consistently provide substantial reads to confidently call sex genotypes (Lambert et al., 2016b, 2019). Importantly, these markers have all been shown to be effective at genotypically sexing R. clamitans in all the focal ponds studied here (Lambert et al., 2019). Clutch sex ratio data are provided as Supplementary Data Sheet 1.

Larval R. clamitans have a relatively long larval development for amphibians where larvae typically hatch in late summer, overwinter as larvae in their natal pond, and metamorphose the following summer roughly 1 year after fertilization. From the two cohorts for which we had genotyped sex ratios in wild clutches in June and July 2017, we followed genotypic sex ratios during larval development. Specifically, we collected larvae in October 2017 prior to overwintering and we collected metamorphs in June 2018. Thus, we sampled tadpoles and metamorphs ∼95 and 337 days post-hatching, respectively, after we collected the final clutch in July 2017. We sampled larvae and metamorphs by comprehensively dipnetting the entirety of each waterbody, which should provide a relatively unbiased sample of each population. The phenotypic (i.e., gonadal) sex of tadpoles collected in October 2017 were not developmentally differentiated enough to be identifiable as ovaries or testes via dissection (Foote and Witschi, 1939; Lambert et al., 2016b) and so were only genotypically sexed. However, metamorphosing R. clamitans have well-differentiated gonads and so we assessed metamorph phenotypic sex by dissection as described previously (Lambert et al., 2015, 2016b). We also genotypically sexed all dissected metamorphs as described above. Larval and metamorph data are provided as Supplementary Data Sheets 2, 3.

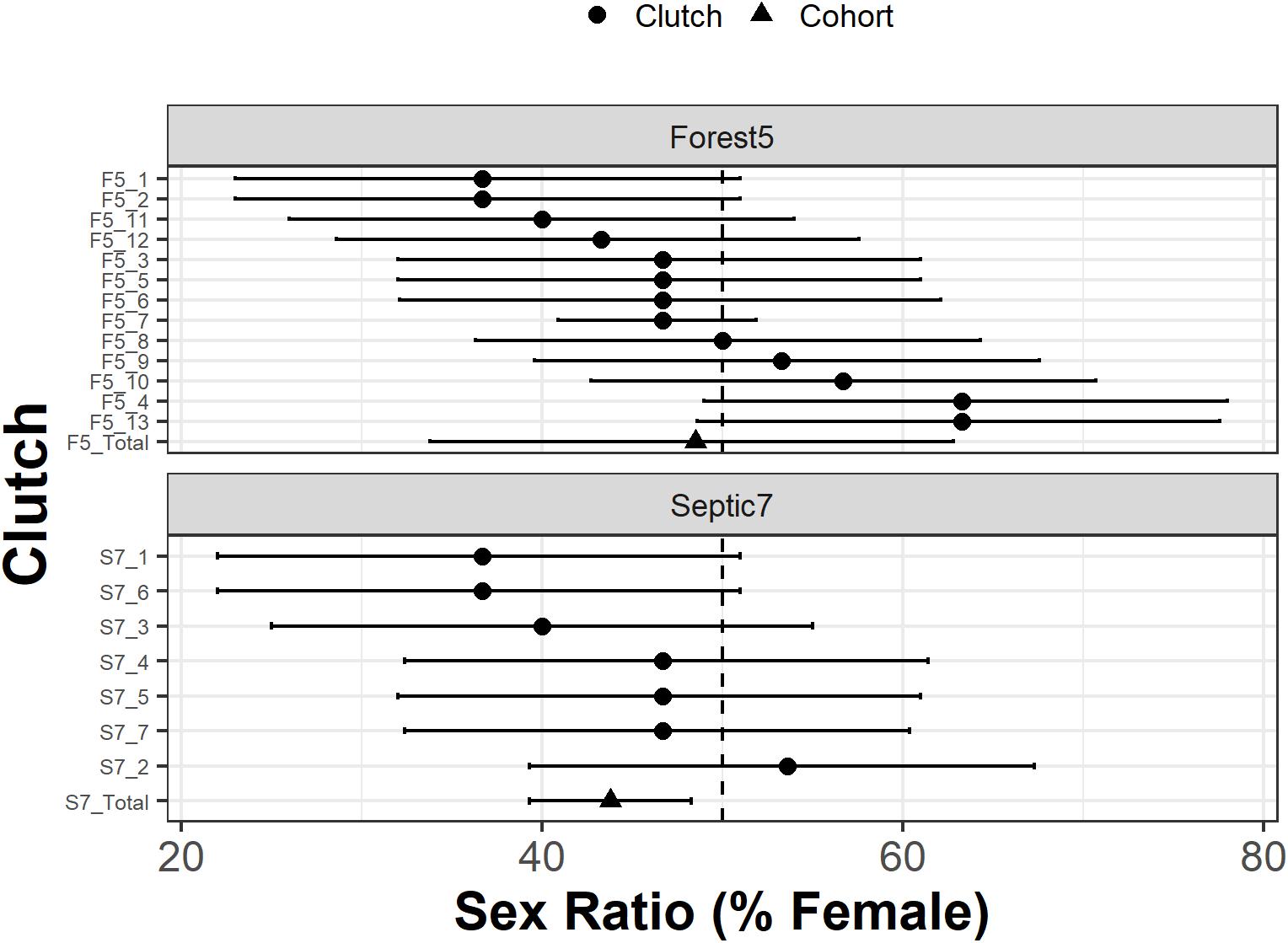

To evaluate whether genotypic sex ratios varied across ontogeny, we took an information theoretic approach to model our data. Specifically, we used binomial generalized linear models (GLMs) to model the frequency of each genotypic sex as a function of Pond (Forest5 or Septic7), developmental Stage (embryo, tadpole, and metamorph), and the effects of Pond and Stage together. We used the aictab function in the R (v 3.4.0) package “AICcmodavg” to compare AICc values and model weights for a null (intercept-only) model, each univariate model, and the additive model. We considered models to provide important explanatory power if they were within ΔAICc ≤ 2.0 of the top-ranked model (i.e., model with lowest AICc) and carried ≥ 0.10 of model weight. If the null model was the top-ranked model, a candidate model was not considered strong evidence but its trend was considered of interest if ΔAICc ≥ 2.0 of the null model and carried ≥ 0.10 of model weight. We constructed models using individuals as the unit of measurement and, because the number of embryo samples were much larger than the tadpole or metamorph samples, we excluded the tadpole samples to minimize the number of contrasts our models had to make between developmental stages. As such, this approach analyzes changes in genotypic sex frequencies from embryo to metamorphosis but does not incorporate an intermediate developmental stage, although these data are presented (Figure 2). We checked for the top models’ fits by plotting residuals against predicted model estimates because small sample sizes in terms of the number of populations studied did not allow for more integrative model diagnostics. The associated R script and data csv are in Supplementary Data Sheets 4, 5.

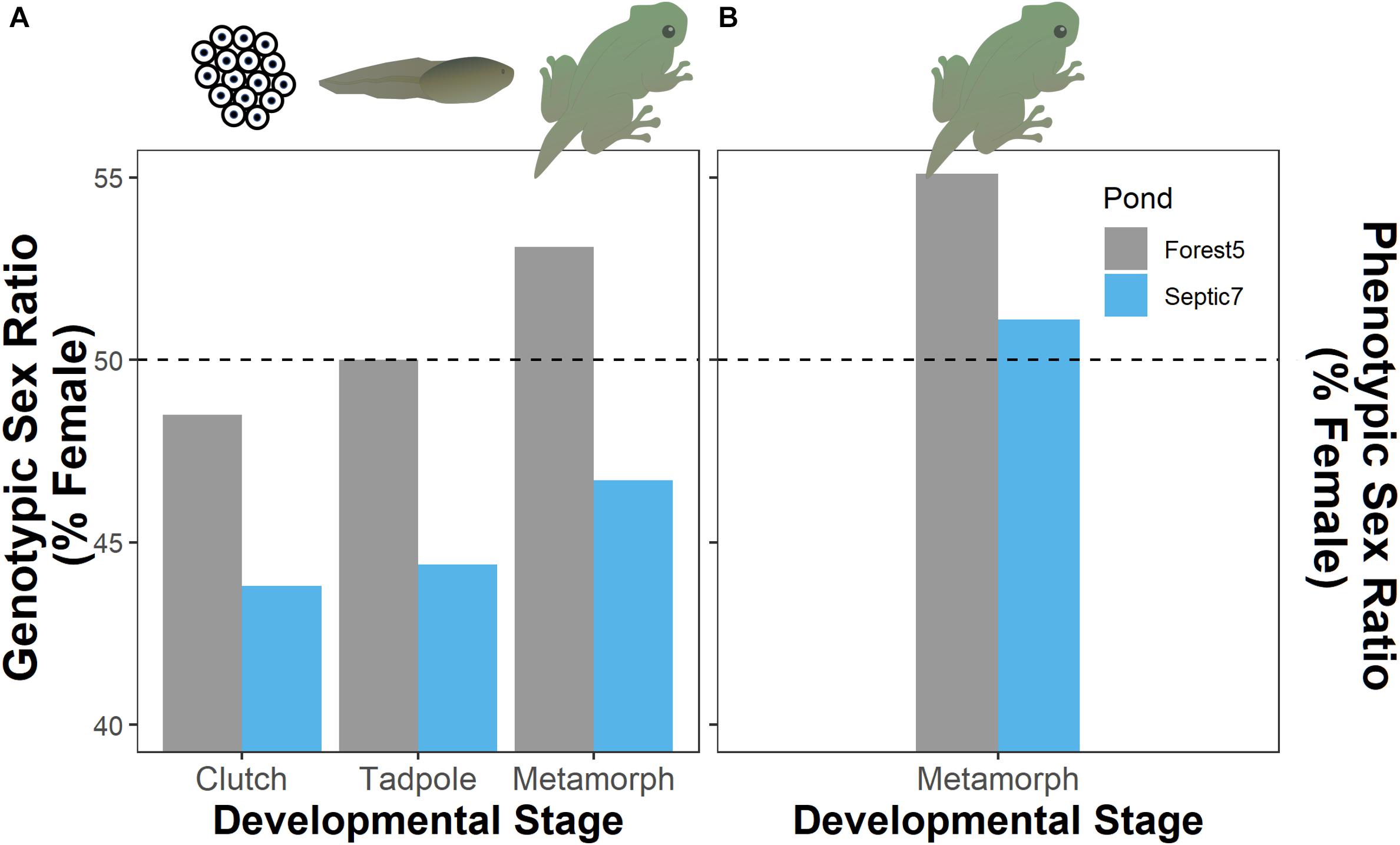

Figure 2. Evidence for genotypic male-biased mortality as genotypic sex ratios (A) in both ponds (Forest5 and Septic7) become increasingly comprised of females as cohorts develop from clutches of embryos through the tadpole stage and into metamorphosis. Final phenotypic sex ratios in these cohorts (B) are comprised of more females than would be expected from genotypic sex ratios due to sex reversal in both cohorts (4 and 12.5% of genotypic males reversing in Forest5 and Septic7, respectively). The horizontal dashed line represents a hypothetical 50:50 sex ratio (phenotypic or genotypic).

We also explored whether individual clutch sex ratios in R. clamitans had the potential to differ from parity. Because sex ratios can require large sample sizes to detect deviations from parity using traditional frequentist statistical binomial approaches (e.g., Chi-squared analysis), we analyzed individual clutch sex ratio data within a probabilistic Bayesian framework using the maximum a posteriori (map) function in the R package “rethinking” following McElreath (2016). We only performed this analysis on clutch sex ratios as we did not analyze deviations from parity in sex ratios from other life stages. To test whether clutch genotypic sex ratios were skewed from parity, we used the map function and a binomial likelihood to assess whether the proportion of females in a sample differed from a flat prior (i.e., differed from an equal sex ratio). For each clutch we assessed deviation from parity using, for example, a script like: precis(map(alist(f ∼ dbinom(30, p), p ∼ dunif(0,1)), data = list(f = 11))). In this example, the script tests for a sex ratio bias in a sample of 30 individuals where 11 are females.

Next, our goal was to understand the relationship – if any – between phenotypic sex ratio variation at metamorphosis and the frequency of sex reversal in either direction (female-to-male or male-to-female reversal). If sex reversal is the primary mechanism underlying phenotypic sex ratio variation, then male-biased phenotypic sex ratios would be correlated with higher frequencies of female-to-male sex reversal, and vice versa for female-biased phenotypic sex ratios. To do so, we leveraged specimens collected the prior year across six populations. In 2016, we collected metamorphosing R. clamitans tadpoles from six ponds along a forest-suburban environmental gradient, including the two ponds (Forest5 and Septic7) sampled for the sex-biased mortality study. Because larval R. clamitans have a relatively long larval development for amphibians (∼1 year), R. clamitans larvae are sensitive to drought as ponds can dry in late summer or fall, resulting in complete mortality of entire larval cohorts prior to metamorphosis the following year. Because of the drought conditions, metamorphs were only present in a subset of ponds (n = 6; AV08, Septic3, Septic7, Septic10 Sewer3, Forest5) used in prior studies and which maintained water over winter (Lambert et al., 2015, 2019). Even so, the ponds sampled here cover the extent of a forest-suburban environmental gradient used in prior studies of sex ratios and sex reversal (Lambert et al., 2015, 2019). We surveyed ponds at least twice per week, collecting metamorphosing R. clamitans larvae from these six ponds as they emerged in summer 2016 and assessed gonadal sex via dissection to estimate phenotypic sex ratios. To infer sex reversal, we genotyped a random subset of metamorphs’ sex (minimum of 55% of individuals in a cohort, but typically 70% or more) and identified individuals where genotypic sex differed from phenotypic sex.

We also used these data to explore whether sex ratios and sex reversal were associated with differences in environmental conditions across populations. Although in our prior work we found that sex reversal occurred in both the female-to-male and male-to-female directions and was prevalent across 16 R. clamitans populations, including four forested and 12 suburban populations, we were unable to confidently assess environmental relationships with sex reversal frequencies (Lambert et al., 2019). This is because our prior study assessed sex reversal in adult R. clamitans and relating a single year of environmental data to sex reversal frequencies in adults is not possible because this species survives up to 7 years and adult populations comprise multiple overlapping cohorts (Shirose and Brooks, 1995). By assessing sex ratios and sex reversal at metamorphosis here, we can more confidently explore environmental relationships with sex ratios and sex reversal. We collected water condition data [specific conductance (i.e., conductivity), pH, dissolved oxygen, and temperature] at each survey using an Oakton PCSTestr 35 Multiparameter probe (conductivity, pH, and temperature) and a YSI ProODO Optical Meter for dissolved oxygen as described previously (Lambert et al., 2019). We used the mean measurement across surveys for each environmental condition in our statistical analyses. Using GIS and custom high-resolution suburban land use data, we also calculated the percent of land cover surrounding each pond that was either forest or suburban development (Lambert et al., 2019). Our prior work has found that, although environmental conditions certainly fluctuate throughout the year within a pond, relative differences among ponds are generally constant (Lambert et al., 2019). This is important here because the developmental period where R. clamitans larval sex determination is sensitive to environmental conditions is unclear. As such, our environmental correlates can help identify patterns of relative environmental conditions associated with sex.

We used a similar modeling approach as described in the sex-biased mortality portion of our study. To analyze whether sex ratios varied as a function of sex reversal frequency, we again used binomial GLMs with phenotypic sex frequency as a binary response variable and assessed the independent and additive influence of female-to-male and male-to-female sex reversal frequencies on phenotypic sex ratios. We similarly modeled the relationship between environmental conditions and phenotypic sex ratios using the same approach except that we used each pond as the unit of measurement and express sex ratios as the proportion of females (individuals with phenotypic ovaries) and sex reversal rates as proportion of genotypic females with testes (female-to-male reversal) or genotypic males with ovaries (male-to-female reversal). Finally, we modeled environmental relationships and either direction of sex reversal separately. For female-to-male sex reversal, our response variable was a binary probability of a genotypic female having either testes or ovaries (i.e., a phenotypic male or female, respectively). We used the same modeling approach for male-to-female sex reversal but using genotypic males. Because the number of sampled populations (n = 6) was relatively low due to drought conditions, we only modeled the additive effects of at most two explanatory variables in a single model to avoid overfitting. The associated R script and data csv are in Supplementary Data Sheet 6.

In total, we genotyped 598 embryos from seven and 13 clutches, respectively, from the two ponds Septic7 (n = 208 embryos total) and Forest5 (n = 390 embryos total). We sampled 36 tadpoles from each pond and genotyped the sex of all tadpoles. For metamorphs, we sampled 49 frogs from Forest5 and 45 from Septic7, genotyping all metamorphs. By tracking genotypic sex ratios from embryogenesis through metamorphosis in these cohorts, we found that genotypic sex-biased mortality – specifically male-biased mortality – contributed to phenotypic sex ratios in metamorphosing frog cohorts. In both ponds, genotypic sex ratios become more female-biased as larvae developed from embryos to tadpoles through metamorphosis (Figure 2). Our analysis found evidence for sex-biased mortality (Table 1). In this analysis, an intercept-only model was ranked highest but a model including Stage received sufficient support to infer consistent male-biased mortality between both ponds. Additionally, male-to-female sex reversal caused the final phenotypic sex ratios to become further female-biased relative to the initial genotypic sex ratios of these cohorts’ clutches (Figure 2).

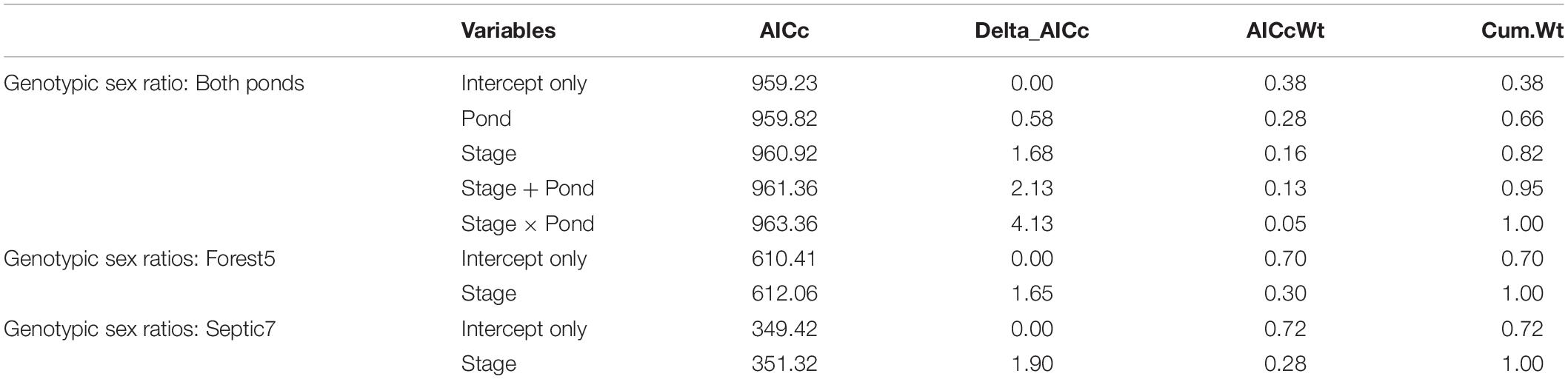

Table 1. Analysis of models of genotypic sex ratio across developmental stages (a proxy of sex-biased mortality) and between ponds using individual sample as the unit of measurement.

Interestingly, individual clutch genotypic sex ratios varied from 36.7 to 63.3% female. Our analyses support male-biased genotypic sex ratios for four clutches, two from Septic7 (S7_1 and S7_6) and two from Forest5 (F5_1 and F5_2; Figure 3). The cohort genotypic sex ratio estimated by summing across clutches for Septic7 also had a significant male bias (Figure 3). There was also support for two clutches from Forest5 (F5_4 and F5_13) exhibiting a genotypic female-bias (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Genotypic sex ratios for individual clutches (circles) in two R. clamitans populations. Clutch identifiers are on the y-axis. Cohort genotypic sex ratios (triangles) are pooled across clutches. The vertical dashed line indicates sex ratios at parity (50% female and 50% male). Horizontal bars are Bayesian credible intervals and higher support for biased sex ratios is observed in clutches with credible intervals that minimally overlap or do not overlap the vertical line at parity.

From across the six ponds, we phenotypically sexed 221 (n = 29–56) metamorphosing R. clamitans. Phenotypic sex ratios in metamorphs from the six focal ponds in 2016 ranged from 39–52% female. We did not identify any environmental correlates of phenotypic sex ratios. Of our models evaluating possible environmental correlations with phenotypic sex ratios, no model including environmental variables improved model fit over a null, intercept-only model all models (ΔAICc > 4.3 over null model, AICc Weight ≤ 0.08; Table 2).

We genotyped the sex of a random subset of these metamorphosing R. clamitans larvae from each pond (n = 164 total; n = 18–31 per pond) and inferred sex reversal by identifying differences between each metamorph’s genotypic and gonadal sex (i.e., ovaries vs. testes). Consistent with prior work in adult R. clamitans (Lambert et al., 2019), we found both female-to-male and male-to-female sex reversal directions, each occurring across roughly half of the study populations. Neither direction of sex reversal provided a better fit to the phenotypic sex ratio data than an intercept-only model (Table 2), suggesting sex reversal is not tightly or consistently associated with phenotypic sex ratios.

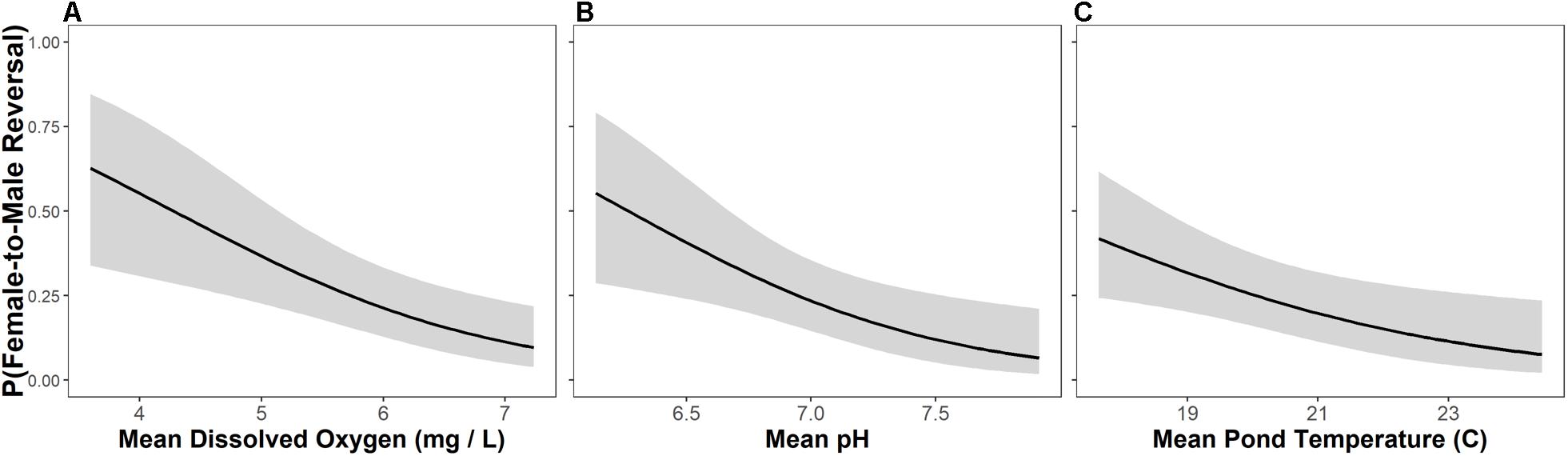

Female-to-male sex reversal was best predicted by dissolved oxygen concentrations in ponds with a univariate model carrying > 50% of model weight (Figure 4 and Table 3). Models containing pH, dissolved oxygen + temperature, and temperature alone were also relevant candidate models for female-to-male sex reversal in metamorphosing R. clamitans (Figure 4 and Table 3). In sum, rates of female-to-male sex reversal were highest in metamorphosing tadpoles developing in ponds with low dissolved oxygen, more acidic pH, and cooler pond temperatures.

Figure 4. Female-to-male sex reversal rates are highest in metamorphosing green frog (Rana clamitans) tadpoles developing in ponds with lower dissolved oxygen (A), more acidic pH (B), and cooler water temperatures (C).

No environmental variables explained male-to-female sex reversal (i.e., an intercept-only model was the best supported model; Table 3). However, univariate models containing suburban land use and mean pond water temperatures carried > 24% of AICc model weight each and were within 2.0 ΔAICc from the null model (Table 3). These results provide limited evidence that rates of male-to-female sex reversal were highest in ponds impacted by surrounding suburban land use and ponds with warmer average water temperatures.

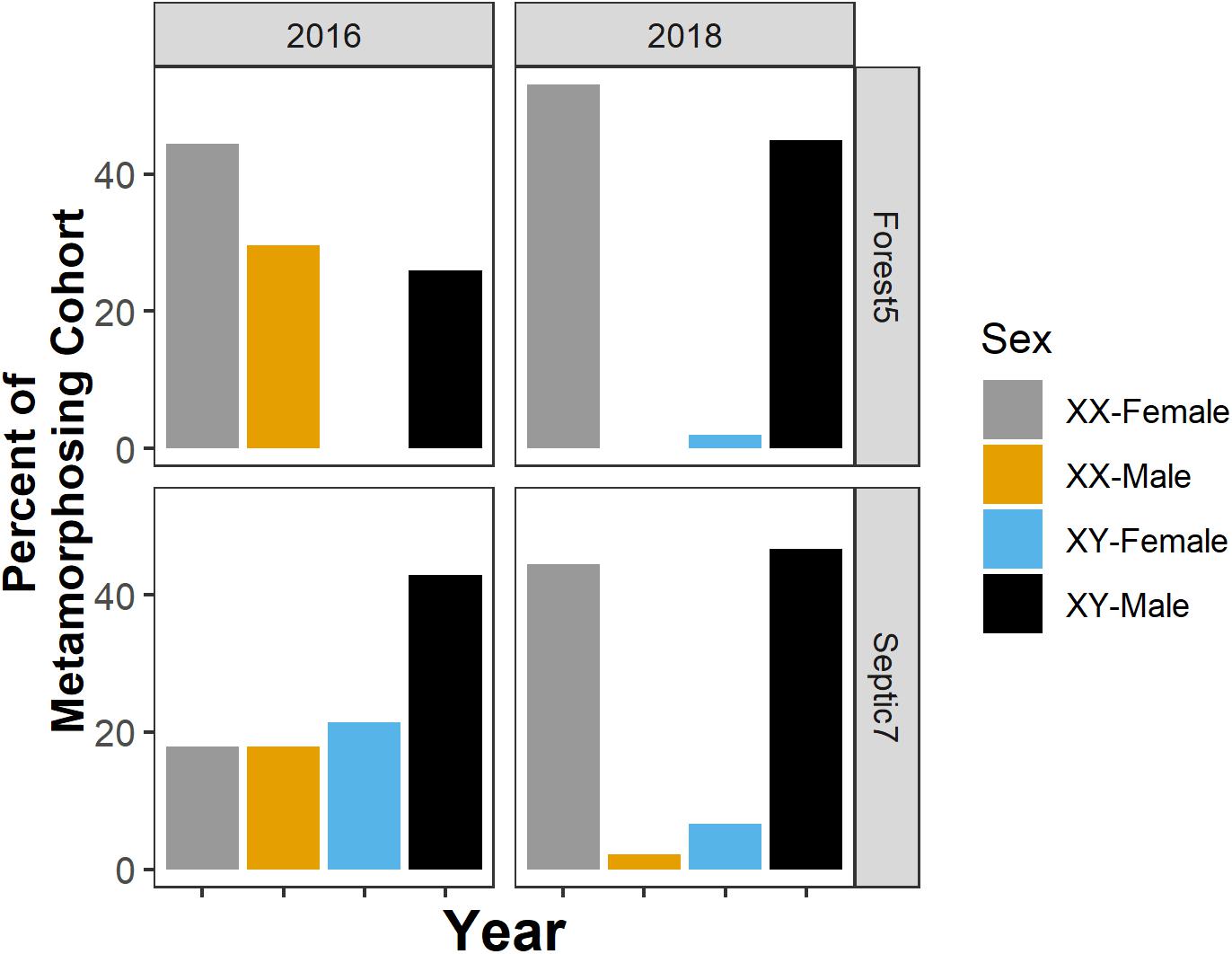

We note that, for the two focal populations we studied for the sex-biased mortality part of the study in 2018 and in the sex reversal part of our study, the extent of sex reversal in metamorphosing cohorts varies between populations and among years within a population (Figure 5). Additionally, our focal environmental variables (dissolved oxygen, temperature, and pH) and suburban land use were largely uncorrelated in this study (linear regression, all p ≥ 0.14), except for a correlation between pond pH and dissolved oxygen (linear regression, p = 0.009, R2 = 0.81).

Figure 5. The presence, direction, and frequency of sex reversal in metamorphosing cohorts varies between populations and among years within a population. Sexual genotype-phenotype data from two focal ponds – Forest5 and Septic7 – in the years 2016 and 2018. Orange and blue bars represent frequencies of sex-reversed metamorphs and gray and black bars represent non-reversed frogs.

The pattern of genotypic sex ratio in multiple populations from the embryo stage to metamorphosis is consistent with an important role for sex-biased mortality in amphibians. Although there is evidence of sex-biased mortality in juvenile mammals, birds, and even some fish (Kruuk et al., 1999; Cichon et al., 2005; Svensson et al., 2007; Orzack et al., 2015; Moran et al., 2016; Kato et al., 2017; Firman, 2019), to our knowledge, this is the first record of sex-biased mortality in larval amphibians in the wild. Importantly, we find the same pattern of male-biased mortality across two independent frog populations which inhabit contrasting environments, suggesting sex-biased mortality may be a relatively common phenomenon. Although we identified both directions of sex reversal, we found little evidence that sex reversal frequencies are consistently associated with phenotypic sex ratios. Even though sex reversal may not be the dominant mechanism undergirding phenotypic sex ratio variation, sex reversal still contributes to phenotypic sex ratios. In the populations we studied, male-biased mortality produced proportionally more genotypic females over larval development and additional sex reversal led to proportionally more phenotypic females than expected from genotypic sex ratios alone. The degree of sex-biased mortality we detected was modest (3–5% percentage change) but the degree of sex ratio change due to sex-biased mortality is sufficient to have important demographic consequences (Wedekind, 2017). To be clear, we identified sex-biased mortality as a mechanism that shapes sex ratios of individual wild amphibian populations, but our study was not designed to document whether sex-biased mortality shapes sex ratio variation across populations. Additionally, we note that our limited sample size of six populations may have had limited power to detect a relationship between sex reversal and phenotypic sex ratios, although the lack of a detectable pattern with these six population is notable. Sex-biased mortality, to our knowledge, is a previously undocumented process in larval amphibians and acts in concert with other processes like sex reversal to shape the phenotypic sex ratios of entire cohorts.

The causes for sex-biased mortality in this system remain to be studied, but both chromosomal and ecological processes may contribute. Heterogametic sex chromosomes (Y-chromosomes in species with XX-XY sex chromosome and W-chromosome in species with ZZ-ZW sex chromosomes) are often degenerate and accumulate deleterious alleles (Charlesworth and Charlesworth, 1997; Gordo and Charlesworth, 2001; Bachtrog, 2008; Miura et al., 2012; but see Kratochvil et al., 2021). As such, these degraded sex chromosomes can reduce survival and longevity in a diversity of animals (Xirocostas et al., 2020). Given R. clamitans has an XX-XY sex chromosome system (Lambert et al., 2016b), R. clamitans Y-chromosomes may be degraded (although there is no evidence for sex chromosome heteromorphy) which could explain higher rates of genotypic male mortality early in life. The absence of YY-individuals in our study may provide additional support for this hypothesis if YY-embryos are frequently unfit, as is often expected (Bull, 1983; Charlesworth, 1996). However, embryos with two Y-chromosomes may also never exist in wild populations if ecological factors limit reproduction by male-to-female reversed frogs.

Ecological differences between genotypic female and male larvae may also contribute to sex-biased mortality. For instance, pilot laboratory data suggest that male wood frog (Rana sylvatica) tadpoles exhibit higher activity patterns than female tadpoles (Skelly et al., unpubl.). Higher activity in tadpoles is associated with higher mortality due to predation (Skelly, 1994). If R. clamitans larvae similarly display sex-specific behaviors, then there is the possibility for sex-biased predation that could contribute to the sex-biased mortality we observed. Further, sex-specific behaviors may also influence sex-specific sampling efficacy. For instance, if sexes differ in microhabitat preferences, different types of sampling approaches may be biased toward one sex or another. Although identifying this issue is beyond the scope of our study, we sampled through the entire water body of each pond, including the benthos and surface and so presumably this bias should not influence our results. In mammals and birds, evidence also suggests that stress or poor health in parents can lead to sex-biased mortality in embryos and offspring (Kruuk et al., 1999; Muller et al., 2005; Perez et al., 2006; Firman, 2019). It is possible that reduced body condition in breeding R. clamitans similarly contributes to sex-biased mortality of embryos and tadpoles. Additionally, sex-biased mortality may be a result of female and male differences in tolerance of various environmental conditions like temperature, as has been seen in birds (Goth and Booth, 2005; DuRant et al., 2016; Eiby et al., 2008). Support for these and other hypotheses require further research.

Our analyses provide some evidence for environmental conditions associated with sex reversal. Specifically, our data suggest that natural water chemistry (dissolved oxygen, pH, and temperature) are related to genotypic female R. clamitans developing as phenotypic males. Experimental evidence in fishes shows that sex reversal can result from variation in dissolved oxygen and pH, and so these conditions may be relevant to amphibian sexual development (Romer and Beisenherz, 1996; Oldfield, 2005; Shang et al., 2006). We also have correlative evidence of temperature-mediated sex reversal where cooler temperatures contribute to higher rates of female-to-male sex reversal. Intriguingly, the opposite trend occurred for male-to-female sex reversal where warmer temperatures contribute to more male-to-female reversal, although the strength of evidence was weak. Temperature-mediated sex reversal in amphibians has been explored in laboratory experiments (Witschi, 1929; Wallace and Wallace, 2000; Lambert et al., 2018) but, to our knowledge, this is the first evidence from wild populations. Sex reversal in amphibians has, in recent decades, been assumed to be strictly caused by environmental pollutants or to unnatural conditions imposed by laboratory experiments (Hayes, 1998; Eggert, 2004; Nakamura, 2013; Orton and Tyler, 2015). This contrasts with work over a century ago that assumed sex reversal was largely a natural process (King, 1909, 1910; Witschi, 1929). Our findings here and previously in both metamorphosing and adult R. clamitans – in addition to recent work on European Agile Frogs (Rana dalmatina) – suggest that sex reversal can be natural and not necessarily a response to abnormal conditions because sex reversal has been observed under natural conditions in the wild for both species (Lambert et al., 2019; Nemeshazi et al., 2020). The conditions (dissolved oxygen, pH, and temperature) correlated with sex reversal vary naturally but can also be influenced by human land use (Holgerson et al., 2018; Lambert et al., 2019). However, in our study, these variables were uncorrelated with suburban land use (all p ≥ 0.14), suggesting that female-to-male reversal is largely natural. Although, our analysis did provide limited support that suburban land used increased the rate of male-to-female sex reversal. These patterns should encourage further work on sex reversal and the relative effect of natural and anthropogenic causes in wild amphibians.

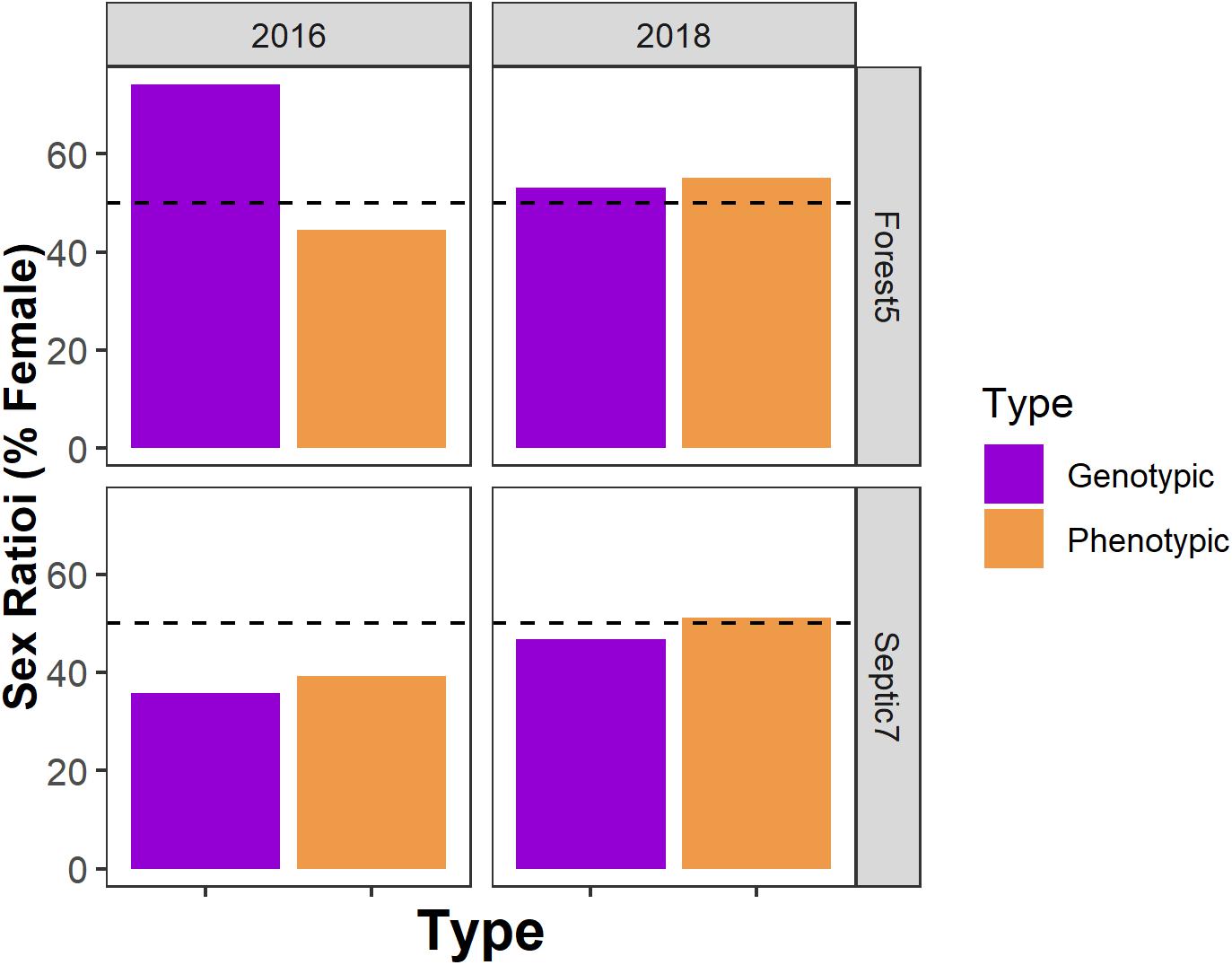

Temporal variation may complicate identifying relationships between the environment, sex ratios, and sex reversal. For instance, in our two focal populations (Forest5 and Septic7), the presence, direction, and frequency of sex reversal varied not only between the two populations but also between years (Figure 5). This resulted in among-year differences in phenotypic and genotypic sex ratios (Figure 6). Among-year variation may explain why our results seemingly contrast with previous research. In prior work in this system, metamorphs sampled across 13 populations in 2012 consistently had male-biased phenotypic sex ratios across multiple forest ponds but equal or female-biased sex ratios in suburban ponds (Lambert et al., 2015). We found no such association between the environment and sex ratios in metamorphs sampled in 2016. Additionally, due to drought, we had a smaller number of populations (n = 6) available for study. Although this sample size is like what is often used in similar studies (Hayes et al., 2003; Orton and Routledge, 2011; Papoulias et al., 2013), it is half of the sample size of our prior work (Lambert et al., 2015). How yearly differences in environmental conditions influence sex ratios and sex reversal is unclear but documenting interannual variation is likely important for understanding the natural and anthropogenic contributions to wild amphibian sexual demography. Importantly, work in fishes and reptiles suggests that climate change is having and will continue to shape the sexual demography of wild animal populations (Ospina-Alvarez and Piferrer, 2008; Montalvo et al., 2012; Holleley et al., 2015). Additionally, experimental research in amphibians provides unambiguous evidence that temperature can modulate amphibian sex reversal (Lambert et al., 2018; Miko et al., 2021). Given the associations between drought, temperature, sex reversal, and sex ratios observed in R. clamitans here, there is a need to understand how climate change will shape sex reversal and population demography in wild amphibians.

Figure 6. Genotypic and phenotypic sex ratios vary not only among populations but also among years within a population. Horizontal dashed lines indicate a hypothetical 50:50 sex ratio. Here are genotypic and phenotypic sex ratio data from two focal ponds – Forest5 and Septic7 – in the years 2016 and 2018.

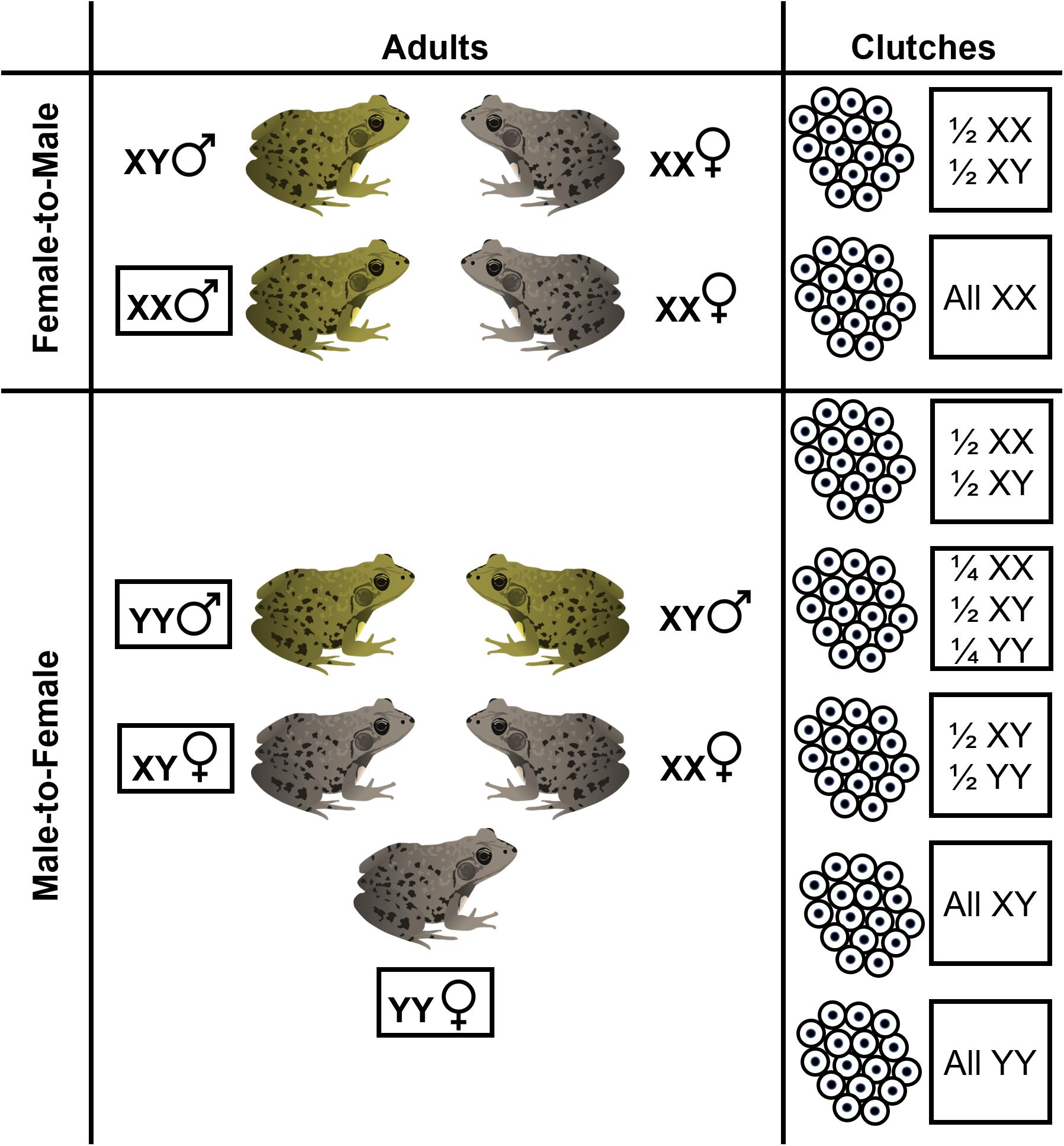

We also found that genotypic sex ratios of individual clutches are variable and can deviate from parity. Breeding by sex-reversed individuals could produce a diversity of potential genotypic sex ratios (Figure 7) which, in aggregate, could hypothetically shape cohort sex ratios. Four clutches (two from each pond) had male-biased genotypic sex ratios. The most likely explanation for this pattern is that male-to-female reversed adults successfully breed, although further work is needed to document breeding by sex-reversed frogs. Interestingly, we also found two clutches in our focal forest pond which had female-biased genotypic sex ratios. Mating between only two frogs – a sex-reversed genotypic female and a non-sex reversed female – would produce a clutch with only genotypically female embryos (i.e., all XX sex chromosome genotypes). However, the female-biased clutch genotypic sex ratios we observed were ∼ 2/3 female, not entirely genotypically female. The only other study, to our knowledge, to assess clutch sex ratios was on European Common Frogs (Rana temporaria) and also found several clutches that were ∼ 2/3 genotypic female (Alho et al., 2010). Alho et al. (2010) interpreted this as a result of multiple paternity where one father was a sex-reversed XX-male. While the drivers of female-biased (but not entirely female) clutches are unclear, multiple paternity and “clutch piracy” is known to occur in frogs (Laurila and Seppa, 1998; Vietes et al., 2004) and so these sex ratios could potentially be the result of mating between a sex-reversed genotypic female, a sex-concordant male, and a sex-concordant female. Our individual clutch genotypic sex ratios provide suggestive evidence that sex-reversed frogs breed in the wild which may skew individual clutch and entire cohort genotypic sex ratios at fertilization (Figure 1). Direct observations are still needed to confirm whether sex-reversed adults successfully reproduce and whether this breeding can sufficiently skew entire cohort genotypic sex ratios. We note that because our clutch samples represent field-collected embryos that were hatched in the lab, it is possible that sex-biased mortality occurred during lab hatching, skewing our inferences of clutch sex ratios. Even so, mortality in our lab-hatched embryos was negligible and likely did not impact our inferences here.

Figure 7. Breeding by sex-reversed adults, either due to female-to-male or male-to-female sex reversal, can result in a diversity of hypothetical clutch genotypic sex ratios. In species such as R. clamitans which have an XX-XY male heterogametic sex chromosome systems, if YY individuals are viable, sex reversal may produce phenotypic females that have two Y-chromosomes. Shown are the various hypothetical genotypic-phenotypic sex combinations for adult frogs and associated clutch genotypic sex ratios that can result from various crossings. Other genotypic sex ratios may occur for clutches if mutliple paternity or clutch piracy occurs.

Our work has implications for how we study the role sex variation plays in population, community, and ecosystem biology. The growing recognition that sex reversal in amphibians is common including in environments assumed to be natural and minimally impacted by people – including our observations here – highlights how a binary model of sex (i.e., female vs. male) limits how we study the biology of sex (Alho et al., 2010; Lambert et al., 2019; Nemeshazi et al., 2020). In the case of amphibian sex reversal, we can conceive of at least four sex categories depending on the combination of an individual’s genotypic and phenotypic sex. However, these sex categories may still be incomplete as sexual phenotypes and functions may occur along a gradient rather than discrete categories and sex-reversal may create new emergent behavioral and morphological phenotypes that differ from expectations based on constituent phenotypic or genotypic sexes (Li et al., 2016). Sex ratios can influence intraspecific interactions in a population and sex differences in behavior or morphology can shape predation rates and impacts on community and ecosystem processes (Lode et al., 2004, 2005; Weir et al., 2011; Liker et al., 2014; Fryxell et al., 2015). Given this, sex reversal combined with sex-biased mortality has the potential to influence the role of individuals within populations as well as how populations of different genotypic and phenotypic sex compositions influence the broader biological community and ecosystem properties. There has been an increasing call for biologists to rethink our understanding of sex roles and sexual variation in amphibians may open opportunities to expand this area of inquiry (Ah-King and Ahnesjo, 2013; Monk et al., 2019; Warkentin, 2021).

We document multiple processes that work together to shape phenotypic sex ratios of metamorphosing tadpoles. Particularly noteworthy is the consistent pattern of male-biased mortality between two disparate populations. Sex-biased mortality among pre-metamorphic life stages has, to our knowledge, never been documented before in amphibians and represents a previously-unknown contribution to amphibian population demography. Sex-biased mortality, particularly in the context of sex reversal, has the potential to shape amphibian ecological and evolutionary dynamics due to the underappreciated influence on both the genotypic and phenotypic sexual makeup of populations. We further highlight how phenotypic sex ratios may not be a reliable proxy for important biological processes. For example, sex-biased mortality could skew genotypic sex ratios in one direction, but sex reversal could bring phenotypic sex ratios back to parity; superficially this equal sex ratio would appear unremarkable whereas it is in fact shaped by the joint effects of sex-biased mortality and sex reversal. Continued exploration of the processes underlying the sexual demography of wild populations will be essential not only to our general understanding of population biology but to conserving populations and species in the face of global environmental change.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

The animal study was reviewed and approved by Yale IACUC Prototocols 2013-10361 and 2015-10681.

ML, TE, and DS conceived the project idea, contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript. ML performed field and laboratory procedures and conducted statistical analyses. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was funded by NSF DDIG-1701311 to ML and DS.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We thank R. Denton, A. Georges, A. Kamath, J. Monk, M. Packer, O. Schmitz, G. Wagner, and A. Wesner for conversations about the biology of sex.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fevo.2021.756476/full#supplementary-material

Ah-King, M., and Ahnesjo, I. (2013). The “sex role” concept: an overview and evaluation. Evol. Biol. 40, 461–470. doi: 10.1007/s11692-013-9226-7

Alho, J. S., Matsuba, C., and Merila, J. (2010). Sex reversal and primary sex ratios in the common frog (Rana temporaria). Mol. Ecol. 19, 1763–1773. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04607.x

Bachtrog, D. (2008). The temporal dynamics of processes underlying Y chromosome degeneration. Genetics 179, 1513–1525. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.084012

Bachtrog, D., Mank, J. E., Peichel, C. L., Kirkpatrick, M., Otto, S. P., Ashman, T.-L., et al. (2014). Sex determination: why so many ways of doing it? PLoS One 12:e1001899. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001899

Bull, J. J. (1983). Evolution of Sex Determining Mechanisms. Menlo Park, CA: Benjamin/Cummings Pub. Co., Advanced Book Program.

Charlesworth, B. (1996). The evolution of chromosomal sex determination and dosage compensation. Curr. Biol. 6, 149–162. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)00448-7

Charlesworth, B., and Charlesworth, D. (1997). Rapid fixation of deleterious alleles can be caused by Muller’s ratchet. Genet. Res. 70, 63–73. doi: 10.1017/S0016672397002899

Cichon, M., Sendecka, J., and Gustafsson, L. (2005). Male-biased sex ratio among unhatched eggs in great tit Parus major, blue tit P. caeruleus and collared flycatcher Ficedula albicollis. J. Avian Biol. 36, 386–390. doi: 10.1111/j.0908-8857.2005.03589.x

Cotton, S., and Wedekind, C. (2009). Population consequences of environmental sex reversal. Conserv. Biol. 23, 196–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2008.01053.x

DuRant, S. E., Hopkins, W. A., Carter, A. W., Kirkpatrick, L. T., Navara, K. J., and Hawley, D. M. (2016). Incubation temperature causes skewed sex ratios in a precocial bird. J. Exp. Biol. 219, 1961–1964. doi: 10.1242/jeb.138263

Earl, J. E. (2019). Evaluation the assumptions of population projection models used for conservation. Biol. Conserv. 237, 145–154. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2019.06.034

Eggert, C. (2004). Sex determination: the amphibian models. Reprod. Nutr. Dev. 44, 539–549. doi: 10.1051/rnd:2004062

Eiby, Y. A., Wilmer, J. W., and Booth, D. T. (2008). Temperature-dependent sex-biased embryo mortality in a bird. Proc. R. Soc. B 275, 2703–2706. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2008.0954

Firman, R. C. (2019). Exposure to high male density causes maternal stress and female-biased sex ratios in a mammal. Proc. R. Soc. B 287:20192909. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2019.2909

Fisher, R. A. (1930). The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection. Oxford: Clarendon. doi: 10.5962/bhl.title.27468

Foote, C. L., and Witschi, E. (1939). Effects of sex hormones on the gonads of frog larvae (Rana clamitans): sex inversion in females; stability in males. Anat. Rec. 75, 75–83. doi: 10.1002/ar.1090750109

Fryxell, D. C., Arnett, H. A., Apgar, T. M., Kinnison, M. T., and Palkovacs, E. P. (2015). Sex ratio variation shapes the ecological effects of a globally introduced freshwater fish. Proc. R. Soc. B 282:20151970. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2015.1970

Gordo, I., and Charlesworth, B. (2001). The speed of Muller’s ratchet with background selection, and the degeneration of Y chromosomes. Genet. Res. 78, 149–161. doi: 10.1017/S0016672301005213

Goth, A., and Booth, D. T. (2005). Temperature-dependent sex ratio in a bird. Biol. Lett. 1, 31–33. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2004.0247

Hardy, I. C. W. (2002). Sex Ratios: Concepts and Research Methods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511542053

Hayes, T., Haston, K., Tsui, M., Hoang, A., Haeffele, C., and Vonk, A. (2003). Atrazine-induced hermaphroditism at 0.1 ppb in American leopard frogs (Rana pipiens): laboratory and field evidence. Environ. Health Perspect. 111, 568–575. doi: 10.1289/ehp.5932

Hayes, T. B. (1998). Sex determination and primary sex differentiation in amphibians: genetic and developmental mechanisms. J. Exp. Zool. 281, 373–399. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-010X(19980801)281:5<373::AID-JEZ4>3.0.CO;2-L

Holgerson, M. A., Lambert, M. R., Freidenburg, L. K., and Skelly, D. K. (2018). Suburbanization alters small pond ecosystems: shifts in nitrogen and food web dynamics. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 75, 641–652. doi: 10.1139/cjfas-2016-0526

Holleley, C. E., O’Meally, D., Sarre, S. D., Marshall-Graves, J. A., Ezaz, T., Matsubara, K., et al. (2015). Sex reversal triggers the rapid transition from genetic to temperature-dependent sex. Nature 523, 79–82. doi: 10.1038/nature14574

Holleley, C. E., Sarre, S. D., O’Meally, D., and Georges, A. (2016). Sex reversal in reptiles: reproductive oddity or powerful driver of evolutionary change? Sex. Dev. 10, 279–287. doi: 10.1159/000450972

Kato, T., Matsui, S., Terai, Y., Tanabe, H., Hashima, S., Kasahara, S., et al. (2017). Male-specific mortality biases secondary sex ratio in Eurasian tree sparrows Passer montanus. Ecol. Evol. 7, 10675–10682. doi: 10.1002/ece3.3575

King, H. D. (1909). Studies on sex-determination in amphibians. II. Biol. Bull. 16, 27–43. doi: 10.2307/1536023

King, H. D. (1910). Temperature as a factor in the determination of sex in amphibians. Biol. Bull. 18, 131–137. doi: 10.2307/1536099

Kratochvil, L., Stock, M., Rovatsos, M., Bullejos, M., Herpin, A., Jeffries, D. L., et al. (2021). Expanding the classical paradigm: what we have learnt from vertebrates about sex chromosome evolution. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 376:20200097. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2020.0097

Kruuk, L. E. B., Clutton-Brock, T. H., Albon, S. D., Pemberton, J. M., and Guinness, F. E. (1999). Population density affects sex ratio variation in red deer. Nature 399, 459–461. doi: 10.1038/20917

Lambert, M. R. (2015). Clover root exudate produced male-biased sex ratios and accelerates male metamorphic timing in wood frogs. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2:150433. doi: 10.1098/rsos.150433

Lambert, M. R., Giller, S. J., Barber, L. B., Fitzgerald, K. C., and Skelly, D. K. (2015). Suburbanization, estrogen contamination, and sex ratio in wild amphibian populations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 11881–11886. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1501065112

Lambert, M. R., Stoler, A. B., Smylie, M. S., Relyea, R. A., and Skelly, D. K. (2016a). Interactive effects of road salt and leaf litter on wood frog sex ratios and sexual size dimorphism. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 74, 141–146. doi: 10.1139/cjfas-2016-0324

Lambert, M. R., Skelly, D. K., and Ezaz, T. (2016b). Sex-linked markers in the North American green frog (Rana clamitans) developed using DArTseq provide early insight into sex chromosome evolution. BMC Genomics 17:844. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-3209-x

Lambert, M. R., Smylie, M. S., Roman, A. J., Freidenburg, L. K., and Skelly, D. K. (2018). Sexual and somatic development of wood frog tadpoles along a thermal gradient. J. Exp. Zool. A 329, 72–79. doi: 10.1002/jez.2172

Lambert, M. R., Tran, T., Kilian, A., Ezaz, T., and Skelly, D. K. (2019). Molecular evidence for sex reversal in wild populations of green frogs (Rana clamitans). PeerJ 7:e6449. doi: 10.7717/peerj.6449

Laurila, A., and Seppa, P. (1998). Multiple paternity in the common frog (Rana temporaria): genetic evidence from tadpole kind groups. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 63, 221–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8312.1998.tb01515.x

Li, H., Holleley, C. E., Elphick, M., Georges, A., and Shine, R. (2016). The behavioural consequences of sex reversal in dragons. Proc. R. Soc. B 283:20160217. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2016.0217

Liker, A., Freckleton, R. P., and Szekely, T. (2014). Divorce and infidelity are associated with skewed adult sex ratios in birds. Curr. Biol. 24, 880–884. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.02.059

Lode, T., Holveck, M.-J., and Lesbarreres, D. (2005). Asynchronous arrival pattern, operational sex ratio and occurrence of multiple paternities in a territorial breeding anuran, Rana dalmatina. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 86, 191–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2005.00521.x

Lode, T., Holveck, M.-J., Lesbarreres, D., and Pagano, A. (2004). Sex-biased predation by polecats influences the mating system of frogs. Proc. R. Soc. B 271(Suppl. 6), S399–S401. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2004.0195

McElreath, R. (2016). Statistical Rethinking: A Bayesian Course with Examples in R and Stan. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman and Hall/CRC, 487

Miko, Z., Nemeshazi, E., Ujhegyi, N., Verebelyi, V., Ujszegi, J., Kasler, A., et al. (2021). Sex reversal and ontogeny under climate change and chemical pollution: are there interactions between the effects of elevated temperature and a xenoestrogen on early development in agile frogs? Environ. Pollut. 285:117464. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.117464

Miura, I., Ohtani, H., and Ogata, M. (2012). Independent degeneration of W and Y sex chromosomes in frog Rana rugosa. Chromosome Res. 20, 47–55. doi: 10.1007/s10577-011-9258-8

Monk, J. D., Giglio, E., Kamath, A., Lambert, M. R., and McDonough, C. E. (2019). An alternative hypothesis for the evolution of same-sex sexual behaviour in animals. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 3, 1622–1631. doi: 10.1038/s41559-019-1019-7

Montalvo, A. J., Faulk, C. K., and Holt, G. J. (2012). Southern determination in southern flounder, Paralichthys lethostigma, from the Texas Gulf Coast. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 432-433, 186–190. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2012.07.017

Moran, P., Labbe, L., and Garcia de Leaniz, C. (2016). The male handicap: male-biased mortality explains skewed sex ratios in brown trout. Biol. Lett. 12:20160693. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2016.0693

Muller, W., Groothuis, T. G. G., Eising, C. M., and Dijkstra, C. (2005). An experimental study on the causes of sex-biased mortality in the black-headed gull – the possible role of testosterone. J. Anim. Ecol. 74, 735–741. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2005.00964.x

Nakamura, M. (2013). Is a sex-determining gene(s) necessary for sex-determination in amphibians? Steroid hormones may be the key factor. Sex. Dev. 7, 104–114. doi: 10.1159/000339661

Nemeshazi, E., Gal, Z., Ujhegyiu, N., Verebelyi, V., Miko, Z., Uveges, B., et al. (2020). Novel genetic sex markers reveal high frequency of sex reversal in wild populations of the agile frog (Rana dalmatina) associated with anthropogenic land use. Mol. Ecol. 29, 3607–3621. doi: 10.1111/mec.15596

Oldfield, R. G. (2005). Genetic, abiotic and social influences on sex differentiation in cichlid fishes and the evolution of sequential hermaphroditism. Fish Fish. 6, 93–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2979.2005.00184.x

Orton, F., and Routledge, E. (2011). Agricultural intensity in ovo affects growth, metamorphic development and sexual differentiation in the common toad (Bufo bufo). Ecotoxicology 20, 901–911. doi: 10.1007/s10646-011-0658-5

Orton, F., and Tyler, C. R. (2015). Do hormone-modulating chemicals impact on reproduction and development of wild amphibians? Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 90, 1100–1117. doi: 10.1111/brv.12147

Orzack, S. H., Stubblefield, J. W., Akmaev, V. R., Colls, P., Munne, S., Scholl, T., et al. (2015). The human sex ratio from conception to bird. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.SA. 112, E2102–E2111. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1416546112

Ospina-Alvarez, N., and Piferrer, F. (2008). Temperature-dependent sex determination in fish revisited: prevalence, a single sex ratio response pattern, and possible effects of climate change. PLoS One 3:e2837. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002837

Papoulias, D. M., Schwarz, M. S., and Mena, L. (2013). Gonadal abnormalities in frogs (Lithobates spp.) collected from managed wetlands in an agricultural region of Nebraska, USA. Environ. Pollut. 172, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2012.07.042

Perez, C., Velando, A., and Dominguez, J. (2006). Parental food conditions affect sex-specific embryo mortality in the yellow-legged gull (Larus michahellis). J. Ornithol. 147, 513–519. doi: 10.1007/s10336-006-0074-4

Pettersson, I., and Berg, C. (2007). Environmentally relevant concentrations of ethynylestradiol cause female-biased sex ratios in Xenopus tropicalis and Rana temporaria. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 26, 1005–1009. doi: 10.1897/06-464R.1

Quinn, A. E., Georges, A., Sarre, S. D., Guarino, F., Ezaz, T., and Marshall Graves, J. A. (2007). Temperature sex reversal implies sex gene dosage in a reptile. Science 316:411. doi: 10.1126/science.1135925

Romer, U., and Beisenherzm, W. (1996). Environmental determination of sex in Apistogrammai (Cichlidae) and two other freshwater fishes (Teleostei). Fish Biol. 48, 714–725. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8649.1996.tb01467.x

Sakisaka, Y., Yahara, T., Miura, I., and Kasuya, E. (2000). Maternal control of sex ratio in Rana rugosa: evidence from DNA sexing. Mol. Ecol. 9, 1711–1715. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2000.01038.x

Sarre, S. D., Georges, A., and Quinn, A. (2004). The ends of a continuum: genetic and temperature-dependenet sex determination in reptiles. Bioessays 26, 639–645. doi: 10.1002/bies.20050

Shang, E. H. H., Yu, R. M. K., and Wu, R. S. S. (2006). Hypoxia affects sex differentiation and development, leading to a male dominated population in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Environ. Sci. Technol. 40, 3118–3122. doi: 10.1021/es0522579

Shirose, L. J., and Brooks, R. J. (1995). Growth rate and age at maturity in syntopic populations of Rana clamitans and Rana septentrionalis in central Ontario. Can. J. Zool. 73, 1468–1473. doi: 10.1139/z95-173

Skelly, D. K. (1994). Activity level and the susceptibility of anuran larvae to predation. Anim. Behav. 47, 465–468. doi: 10.1006/anbe.1994.1063

Svensson, M., Rintamaki, P. K., Birkhead, T. R., Griffith, S. C., and Lundberg, A. (2007). Impaired hatching success and male-biased embryo mortality in tree sparrows. J. Ornithol. 148, 117–122. doi: 10.1007/s10336-006-0112-2

Szekely, T., Liker, A., Freckleton, R. P., Fichtel, C., and Kappeler, P. M. (2014). Sex-biased survival predicts adult sex ratio variation in wild birds. Proc. R. Soc. B 281:20140342. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2014.0342

Vieites, D. R., Nieto-Roman, S., Barluenga, M., Palanca, A., Vences, M., and Meyer, A. (2004). Post-mating clutch piracy in an amphibian. Nature 431, 305–308. doi: 10.1038/nature02879

Wallace, H., and Wallace, B. M. N. (2000). Sex reversal of the new Triturus cristatus reared at extreme temperature. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 44, 807–810.

Warkentin, K. (2021). “Chapter 4- Queering herpetology: on human perspectives and the study of diverse animals,” in Herpetologia Brasileira Contemporanea, ed. L. F. Toledo (São Paulo: Sociedade Brasileira de Herpetologia).

Wedekind, C. (2017). Demographic and genetic consequences of disturbed sex determination. Philos. Trans. B 372:20160326. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2016.0326

Weir, L. K., Grant, J. W. A., and Hutchings, J. A. (2011). The influence of operational sex ratio on the intensity of competition for mates. Am. Nat. 177, 167–176. doi: 10.1086/657918

West, S. (2009). Sex Allocation. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. doi: 10.1515/9781400832019

Witschi, E. (1929). Studies on sex differentiation and sex determination in amphibians II. Sex reversal in female tadpoles of Rana sylvatica following the application of high temperatures. J. Exp. Zool. 52, 267–291. doi: 10.1002/jez.1400520203

Keywords: amphibian, endocrine disruption, population dynamics, sex determination, suburban, urban ecology

Citation: Lambert MR, Ezaz T and Skelly DK (2021) Sex-Biased Mortality and Sex Reversal Shape Wild Frog Sex Ratios. Front. Ecol. Evol. 9:756476. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2021.756476

Received: 10 August 2021; Accepted: 29 September 2021;

Published: 21 October 2021.

Edited by:

Veronika Bókony, Centre for Agricultural Research, HungaryReviewed by:

Edina Nemesházi, University of Veterinary Medicine Budapest, HungaryCopyright © 2021 Lambert, Ezaz and Skelly. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Max R. Lambert, bGFtYmVydC5tcm1AZ21haWwuY29t

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.