Abstract

Interactions between organisms and their environments are central to how biological diversity arises and how natural populations and ecosystems respond to environmental change. These interactions involve processes by which phenotypes are affected by or respond to external conditions (e.g., via phenotypic plasticity or natural selection) as well as processes by which organisms reciprocally interact with the environment (e.g., via eco-evolutionary feedbacks). Organism-environment interactions can be highly dynamic and operate on different hierarchical levels, from genes and phenotypes to populations, communities, and ecosystems. Therefore, the study of organism-environment interactions requires integrative approaches and model systems that are suitable for studies across different hierarchical levels. Here, we introduce the freshwater isopod Asellus aquaticus, a keystone species and an emerging invertebrate model system, as a prime candidate to address fundamental questions in ecology and evolution, and the interfaces therein. We review relevant fields of research that have used A. aquaticus and draft a set of specific scientific questions that can be answered using this species. Specifically, we propose that studies on A. aquaticus can help understanding (i) the influence of host-microbiome interactions on organismal and ecosystem function, (ii) the relevance of biotic interactions in ecosystem processes, and (iii) how ecological conditions and evolutionary forces facilitate phenotypic diversification.

Introduction

Interactions between organisms and their biotic and abiotic environment are central to our understanding of how biological diversity originates and how it is maintained (Pimentel, 1961; Kokko and López-Sepulcre, 2007; Hendry, 2017; Lion, 2018; Schwab et al., 2018; Govaert et al., 2019; Skúlason et al., 2019). Such interactions can be unidirectional or reciprocal, and involve dynamic processes operating across different levels of biological organization, from individuals and populations to communities and ecosystems. Examples of unidirectional processes include phenotypic responses to environmental conditions within an organism’s lifetime (e.g., phenotypic plasticity; Via and Lande, 1985; West-Eberhard, 2003; Sultan, 2021) and changes in population fitness across generations (e.g., adaptive evolution; Charlesworth et al., 2017). Examples of reciprocal interactions include coevolutionary dynamics between species (e.g., Anderson and May, 1982; Thompson, 1989), associations between hosts and microbial communities (e.g., microbiomes; Foster et al., 2017; Koskella et al., 2017), and evolution via organism-mediated modification of abiotic conditions (e.g., niche construction; Odling-Smee et al., 1996; Laland et al., 2016). Organism-environment interactions are inextricably linked with evolutionary processes, but their complexity and contingency represent a significant challenge to understanding biodiversity dynamics in natural ecosystems (Levins and Lewontin, 1985; Sultan, 2015; Hendry, 2017; Lion, 2018; Svensson, 2018; De Meester et al., 2019). Therefore, understanding how organisms and ecosystems respond to environmental heterogeneity in space and time remains an important challengue in evolutionary ecology, and necessitates studies that investigate organism-environment interactions across different hierarchical levels.

Much of our current mechanistic understanding of the emergence and evolution of phenotypic variation comes from studies using traditional microbe, plant, and animal model systems, which have provided great insight into how genetic, developmental, and environmental factors shape phenotypes (Lenski et al., 1991; Kohler, 1994; Silver, 1995; Dooley and Zon, 2000; Duvick, 2001; Barnett, 2007; Cresko et al., 2007; Fielenbach and Antebi, 2008; Bedford and Hoekstra, 2015; Hake and Ross-Ibarra, 2015). A mounting body of work has provided vast amounts of genomic resources and phenotypic data, as well as molecular toolkits and analytical methods (e.g., Ramos et al., 2014; O’Leary et al., 2016; Hunt et al., 2018; Thurmond et al., 2019). While some of the existing models have considerable ecological breadth and functional tractability both in laboratory and field settings (e.g., Skúlason et al., 2019; Duffy et al., 2021), many of these systems have only limited potential for integration across multiple scales of inquiry (i.e., from individual variation to dynamics within populations, communities, and ecosystems). Such integration is however critical in ecology and evolution, not only because natural ecosystems consist of a myriad of species interactions (De Meester et al., 2019; Travis, 2020) which are subject to adaptive change (Thompson, 1998; Hairston et al., 2005), but also because the hierarchical structure of natural ecosystems, ranging from the activities of individuals to ecosystem-level processes, is the relevant object of study (Wimsatt and Wimsatt, 2007). Thus, the introduction of model systems that are suitable for studies across hierarchical levels can enrich our understanding of the contextual nature of organism-environment interactions (Levins and Lewontin, 1985). Moreover, a wider set of empirical model systems is needed in order to make headway in integrative studies of microevolutionary processes in ecologically relevant settings, and to improve our ability to generalize the underlying processes (Bolker, 2014; Alfred and Baldwin, 2015).

In line with this, we introduce a model system to address fundamental questions in ecology and evolution from multiple perspectives and across scales: the freshwater isopod Asellus aquaticus, commonly known as aquatic sowbug, water slate, or waterlouse. This species is widely distributed, phenotypically variable, and has a very long history in research, ranging from environmental and ecotoxicological to developmental and evolutionary studies (Figure 1; e.g., Unwin and Stebbing, 1920; Kosswig and Kosswig, 1940; Konec et al., 2015; Fuller et al., 2018; O’Callaghan et al., 2019; Verovnik and Konec, 2019). This sets a solid, but to this day underexploited, foundation for integrative studies on organismal-environment interactions within an eco-evolutionary framework.

FIGURE 1

Over 150 years of research on and with Asellus aquaticus. The figure summarizes published scientific literature on A. aquaticus. We conducted a quantitative literature survey with the search tools of Web of Science (WOS; Clarivate analytics) by searching for the term “asellus aquaticus” in six databases (i.e., BIOSIS, CABI, FSTA, Medline, WOS Core Collection, and Zoological Records). We found 1235 records, published between 1867 and 2020. (A) The graph shows the number of publications per year within a given subject area, as designated by WOS. (B) The graph shows the total number of publications assigned to a specific subject area. The top 10 fields account for 72.58% of all publications, and are indicated by color coding in (A,B) (multiple assignments are possible, summing up to 2845 assignments). The inset in (B) shows a wordcloud with the 100 most used keywords from all A. aquaticus publications. Furthermore, we compiled all records with relevant information (e.g., title, keywords, research areas, and abstract) to a single file which is available online (Zenodo doi: https://zenodo.org/record/5070310#.YV1LQx1S_zU). More details can be found in the Supplementary Material.

We begin our review with an overview of key aspects of A. aquaticus life history, ecology, and evolution that facilitate such integrative studies (see section “Asellus aquaticus as a Model System for Integrative Studies”). Next, we highlight three major areas of integrative research in ecology and evolution for which A. aquaticus is particularly well-suited to address questions across different hierarchical scales (see section “Areas of Integrative Research Using Asellus aquaticus”). Starting at the organismal scale, we show how diverse host-microbiome interactions in A. aquaticus can help us understand host-microbiome evolution (see Koskella et al., 2017). Specifically, how host microbiomes, including endosymbionts and epibionts, can influence organismal performance and fitness, which in turn may affect ecosystem function. Broadening the scale to then include how individuals interact with their external biotic and abiotic environments, we propose that studies on A. aquaticus can aid in understanding species interactions and ecosystem processes. Finally, given substantial phenotypic variation and repeated cases of morphological diversification of this species (e.g., Verovnik and Konec, 2019), we suggest that integrative studies on A. aquaticus can shed light on how ecological conditions and evolutionary forces jointly shape phenotypes. Throughout the review, we emphasize how studies using this species can aid in bridging different disciplines (e.g., ecology, developmental, and evolutionary biology) and levels of biological organization (e.g., from individuals to ecosystems). We note that the species has been extensively used in the field of ecotoxicology (e.g., Bloor, 2011; O’Callaghan et al., 2019), but our goal here is to highlight, in particular, its use as an eco-evolutionary model.

Asellus Aquaticus as a Model System for Integrative Studies

Asellus aquaticus (Crustacea, Isopoda, Asellidae; Linnaeus, 1758) is a sexually reproducing arthropod, with several key features of ecological relevance and methodological benefits that facilitate establishing it as a model system for integrative research. Below, we provide a short historical overview and summarize the key characteristics that make A. aquaticus an excellent model system.

Asellus aquaticus has a long history in biological research (Figure 1). The earliest available scientific publications on A. aquaticus were written in the late 1800s and focused on anatomical and physiological features of organismal development (Dohrn, 1867; Zuelzer, 1907; Wege, 1909). These early studies included detailed descriptions of its life cycle and its ability to regenerate appendages (Unwin and Stebbing, 1920; Needham, 1950; Fano et al., 1976; Murphy and Learner, 1982; Marchetti and Montalenti, 1990). In Box 1, we summarize those and some other characteristics of A. aquaticus, including core aspects of its body plan, reproduction, development, and growth. Research on A. aquaticus shifted, in more recent years, from individual-level variation to population and ecosystem processes, prompting a wider use of this species in ecological and evolutionary studies (Graça et al., 1994; Hargeby et al., 2004; Eroukhmanoff et al., 2009a; Lürig et al., 2019; Lürig and Matthews, 2021).

Life cycle and reproduction in

Body plan: Adults are characterized anatomically by the presence of the derived traits distinctive of isopods’ body plan (Wilson, 1991; Balian et al., 2008; Verovnik et al., 2009; Vick and Blum, 2010). This body plan consists of a dorsoventrally flattened body divided in three tagma. First, the cephalon (ce), which results from the fusion of the mandibulate head and the first thoracic segment with maxillipeds. Second, the pereon (pe) with seven thoracic segments and walking legs (called pareopods), which increase in length posteriorly. Third, the pleon (or abdomen), with abdominal limbs (or pleopods) used for respiration, the uropods, and the gonads. Two of the pleonic segments are free while the others are fused to the telson, forming the pleotelson (pl) (Balian et al., 2008; Verovnik et al., 2009; Vick and Blum, 2010).

Reproduction:Asellus aquaticus is a gonochoric species (Bertin et al., 2002), with a karyotype consisting of eight homomorphic chromosome pairs (2n = 16) in both sexes (Montalenti and Rocchi, 1964; Salemaa, 1979; Valentino et al., 1983). It is presumed to have exclusively sexual reproduction (Unwin and Stebbing, 1920; Ridley and Thompson, 1979). Fertilization is only possible during a short time window (during approximately 24 hours), while the female oviducal openings are free (i.e., right after she molts the exoskeleton posterior to the fifth thoracic segment). Because of this time-limitation in fertility, copulation is preceded by mate guarding; a behavioral strategy common in isopods, during which the male guards the female by carrying her until insemination becomes possible (Jormalainen et al., 1994; Jormalainen, 1998). The duration of this pre-copula (or amplexus) phase is variable (Jormalainen and Merilaita, 1995). After copulation, insemination happens internally with the eggs in the mother’s brood pouch (bp) (within a marsupium) being fertilized during their transit in the oviduct (Wilson, 1991). Females of A. aquaticus are females are assumed not to have a true spermatheca, rather a temporary pouch in the oviduct (i.e., seminal receptacle) that can collect sperm and that regresses after egg-laying without sperm storage (Wilson, 1986). Females can produce a variable number of eggs (between a few dozen to over a hundred; e.g., Lürig and Matthews, 2021) and large females tend to produce more eggs (Arakelova, 2001).

Development and growth: Embryonic development happens within the mother’s brood pouch and different stages of embryogenesis can be easily detected in the brood pouch. Initially, eggs are round and surrounded by the chorion (ch) and the vitelline membrane (vi) (Brusca and Iverson, 1985; Wilson, 1991; Martínez and Defeo, 2006; Wolff, 2009; Vick and Blum, 2010). Early embryogenesis is characterized by the appearance of a dorsal curvature and start of the incorporation of the yolk (y) into the digestive glands (Vick and Blum, 2010). By late embryogenesis, the yolk is fully incorporated, the appendages are well developed, the embryo (e) has lengthened along the ventral curvature, and the thoracic segments are evident (Brusca and Iverson, 1985; Wilson, 1991; Martínez and Defeo, 2006; Wolff, 2009; Vick and Blum, 2010).

In most aspects, A. aquaticus follows the standard development described in isopods (Brusca and Iverson, 1985; Martínez and Defeo, 2006; Wolff, 2009; Vick and Blum, 2010), though analyses of expression patterns and regulation of several Hox genes (i.e., homeobox genes that specify regions of the animal body plan along the head-tail axis) have revealed novel patterns of gene expression (e.g., hindgut expression of Abdominal-B gene; Vick and Blum, 2010). This highlights the potential of this system to study evolutionary changes of segment identity and patterning (Vick and Blum, 2010; Mojaddidi et al., 2018). Embryos develop into small juveniles inside the marsupium and are released from the brood pouch at approximately 1 mm length. Individuals undergo indeterminate growth with biphasic molting; a type of ecdysis, characteristic of isopods (George, 1972; Steel, 1982), whereby the posterior and anterior body halves molt sequentially. First the hind-half (from fifth thoracic segment to posterior-most part of the body) molts, which is followed by hardening of the exoskeleton and subsequent molting of the fore-half (from fourth thoracic segment to anterior-most part of the body), with a time interval of about 24 hours (Unwin and Stebbing, 1920; George, 1972; Marcus, 1990). Sexual maturity, is reached at 1.5 to 3 months (depending on environmental conditions) (e.g., Lürig and Matthews, 2021), and at approximately 3–4 mm length. Growth is continuous after sexual maturation (Steel, 2009). As in other crustaceans, growth is dependent on ecdysis, which involves tissue growth and the synthesis of a new exoskeleton that eventually replaces the old one during the molt (Carlisle, 1956; Chang and Mykles, 2011).

Sexual dimorphism: In males, genitals consist of pairs of testes that are located in the region that binds together the pereon (pe) and the pleon (pl). In females, the ovaries are paired and lie parallel to the hindgut with oviducal openings on the fifth thoracic segment. When a female is about to produce eggs, the ovaries enlarge and extend along the length of the thorax (Unwin and Stebbing, 1920). Besides the gonads, sexual dimorphism in A. aquaticus is apparent in males being larger than females (e.g., Adams et al., 1985) (see section “Sexual Selection and Assortative Mating”) and a few morphological modifications, mostly involved in pre-copula formation (Bertin et al., 2002). Such morphological modifications involve the pleotelson (pl) and several paraeopods, which differ in shape between males and females: in males the fourth pair of paraeopods is reduced and curved, which allows them to position and carry the female during mate guarding, and the first pair of paraeopods bears apophyses that are absent in females (Unwin and Stebbing, 1920; Needham, 1942; Chang, 1986; Brusca and Wilson, 1991; Bertin et al., 2002). The oostegites of females, which are specialized limbs, enlarge to form the brood pouch in the anterior ventral side of the body, covering the oviducal openings.

Isopoda are known for showing extensive intraspecific morphological variation and for being successful colonizers of a wide range of environments (Wetzer, 2002; Wilson, 2008, 2009; Joca et al., 2015; Lins et al., 2017; Shen et al., 2017; Rudy et al., 2018; Alves et al., 2019). Though empirical tests are scarce thus far, some characteristic traits of A. aquaticus, such as biphasic molting (Unwin and Stebbing, 1920; George, 1972; Marcus, 1990; Balian et al., 2008), pre-copula formation (Unwin and Stebbing, 1920; Montalentl, 1990), and the development of brood pouches (Ridley and Thompson, 1979), have been associated with the evolutionary success of A. aquaticus, and of Isopoda in general (Hornung, 2011; Horváthová et al., 2017). In general, A. aquaticus inhabits a variety of natural (and man-made) aquatic habitats, and is common in lakes, ponds, rivers, and creeks across Europe and parts of Asia. In Box 2, we summarize what is known about A. aquaticus phylogeography, including its phylogenetic relationships, as well as patterns of global distribution and ecogeographic variation in life histories. Numerous subspecies of A. aquaticus have been described along the species’ total geographic range (Sket, 1994; Prevorcnik et al., 2004; Verovnik et al., 2009). Its broad distribution and diversity of colonized habitats exposes the species to ecological variation on local and continental scale, and provides opportunities for eco-evolutionary and phylogenetic studies across broad geographic scales.

Phylogeny and ecogeographical patterns.

Map showing the occurrence of A. aquaticus based on publicly available biodiversity databases (gray dots) and previously published studies (yellow dots and polygons). The distribution range of the species estimated by Birštejn (1951); Sket (1994), and Verovnik and Konec (2019), is shown with the orange, the green, and the pink polygons, respectively. This indicates a wide distribution of A. aquaticus throughout Europe and a poorly defined eastern edge of the geographical range (see also Sket, 1994). Note that the latter is likely due to lack of rigorous surveys rather than true differences in abundance (see Supplementray Table 1). Very few publications report explicitly the absence of A. aquaticus from specific locations (Williams, 1962b), most occurrence data comes from contributors from western European countries, and there are discrepancies between studies. It is therefore possible that the species is present in more locations but not yet explored or reported. More details can be found in the Supplementary Material.

Phylogeny:Asellus aquaticus belongs to the Isopoda (von Reumont et al., 2012; Rota-Stabelli et al., 2013; Misof et al., 2014; Thomas et al., 2020), which contains more than 10,000 species with extensive intraspecific morphological variation, sexual dimorphism, sequential hermaphroditism, and with a global distribution (Wetzer, 2002; Wilson, 2008, 2009; Joca et al., 2015; Lins et al., 2017; Shen et al., 2017; Rudy et al., 2018; Alves et al., 2019). Isopoda have successfully colonized a variety of environments, including deep sea, land, and freshwater (Hessler et al., 1979; Poulin, 1995; Wilson, 2008). The colonization of terrestrial and freshwater environments is thought to have occurred independently from marine environments (Carefoot and Taylor, 1995; Broly et al., 2013; Lins et al., 2017), but the timing of this transition to land is uncertain (Lins et al., 2017), due to the scarcity of fossil records for this group (Schmidt, 2008; Broly et al., 2013; Lins et al., 2017). Reconstructing the phylogenetic relationships of Isopoda has been a major challenge (Wetzer, 2002; Wilson, 2008, 2009; Joca et al., 2015; Lins et al., 2017; Shen et al., 2017; Rudy et al., 2018; Alves et al., 2019), and vastly different conclusions have been reached depending on whether phylogenetic reconstructions were based on morphological (e.g., biphasic molting, heart musculature) or molecular data (Zhang et al., 2019).

The combination of different types of data (e.g., mitochondrial and nuclear DNA) and methodological approaches (e.g., maximum likelihood or Bayesian inference; Lartillot et al., 2007; Crotty et al., 2019) has revealed the Asellota, the clade containing A. aquaticus, as the oldest branch of the Isopoda (Watling, 1981; Wilson, 2009; Yu et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2019). Interestingly, two inversions of the origin of replication in the mitochondrial genome took place within the Isopoda; one occurred after the Asellota branched off (see Figure 5 in Zhang et al., 2019) and the other one in the highly derived taxon group composed of Cymothoidae and Corallanidae. Alternatively, and less parsimoniously, the basal isopod taxon could also be the Phreatoicidea (Wetzer, 2002; Kilpert et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2019). Given the recency in the progress of elucidating the phylogenetic isopod relationships, the growing insights from fossil records (see e.g., Selden et al., 2016; Schädel et al., 2020), and the very speciose nature and extreme diversity of this clade, many interesting new insights might still await us, with genomic data increasing rapidly and becoming available for analyses.

Geographic distribution:Asellus aquaticus occurs throughout large parts of Europe (Sket, 1994; Verovnik et al., 2005; Sworobowicz et al., 2015), although its local distribution can be distinctively patchy (Williams, 1962b; Hynes and Williams, 1965; Wolff, 1973). It is hypothesized that A. aquaticus arrived in Europe around 8 to 12 million years ago through the brackish Paratethys basin (Sket, 1994; Verovnik et al., 2005). The species’ current distribution is assumed to reflect the last ice age, where the Appennine and the Balkan Peninsula served as major glacial refugia for many species in Europe (Hewitt, 1999, 2000). Asellus aquaticus probably diversified in such southern refugia before subsequently recolonizing the northern parts of Europe when the ice retreated (Verovnik et al., 2005; Sworobowicz et al., 2015). Recently, it was shown that A. aquaticus might have also survived in the extensive lacustrine systems present along the glacial margins in a vast network of glacial microrefugia across Europe (Sworobowicz et al., 2020). It has also been suggested that dispersal of A. aquaticus may have been influenced by human activity (Williams, 1962b; Verovnik et al., 2005; Sworobowicz et al., 2020), though empirical data supporting this view is still scarce. Genetic diversity is maintained by secondary contact of different phylogroups or lineages (Verovnik et al., 2005), and is highest around the Adriatic Sea, the Alps, and the south-eastern Balkan Peninsula, whereas central and north-eastern Europe seem to be dominated by populations with low genetic diversity (Sworobowicz et al., 2015). Further studies exploring the distribution patterns of this species in more detail could shed light onto its current geographical range and dispersal patterns. This may be particularly relevant given that the wide geographic distribution of A. aquaticus likely reflects a capacity to reach (via dispersal) and to tolerate (or adapt to) a broad range of environments (e.g., high resistance to desiccation, pollution, and changing temperatures; e.g., Aston and Milner, 1980; Weltje, 2006; Konec et al., 2016; O’Callaghan et al., 2019).

Ecogeographic variation in life histories: Studies in natural populations from different geographical locations show that A. aquaticus commonly has two complete generations per year (e.g., in England; Unwin and Stebbing, 1920; Adcock, 1979; Ridley and Thompson, 1979; in Norway; Økland, 1978). These give rise to spring and autumn cohorts (Unwin and Stebbing, 1920; Adcock, 1979; Ridley and Thompson, 1979), which may encounter different selective environments, as shown in other species (e.g., Leys et al., 2017). The first cohort develops from embryo to maturity entirely during the favorable growing season (i.e., summer months), whereas second cohort (overwintering generation) develop rapidly during the first weeks of life, reach sexual maturity, and then enter a state of reproductive stasis (or reproductive diapause) (Brasiello and Tadini, 1969; Adcock, 1979; Steel, 2009). Despite the aforementioned commonalities across geographically distinct locations, A. aquaticus also shows substantial geographic and seasonal variation in breeding patterns and life history characteristics, potentially reflecting adaptation (or plasticity) to differing environmental factors (Anderson, 1969; Økland, 1978; Murphy and Learner, 1982). The length of the breeding season can be highly variable (e.g., 5–11 months; Aston and Milner, 1980), with northern populations having shorter breeding seasons (Anderson, 1969) and periods of sexual inactivity, or reproductive diapause (Fano et al., 1976; Migliore et al., 1982). Such geographic variation in life cycles, including the reproductive diapause, has been proposed to be adaptive: in several northern locations faster development (than in southern locations) allows individuals to exploit resources following reproductive stasis (in spring and summer) (Fano et al., 1976; Vitagliano et al., 1994).

Along with its wide environmental distribution, several studies have documented phenotypic variation across different environments and habitats in A. aquaticus (e.g., Williams, 1962a; Aston and Milner, 1980; Hargeby et al., 2004; Sworobowicz et al., 2015; Lürig et al., 2019), indicating its high capacity for phenotypic change via both phenotypic plasticity and genetic adaptation (see section “Integration and Future Perspectives”). Of particular relevance from an eco-evolutionary perspective, are the repeated cases of ecotype differentiation within Swedish lakes (Eroukhmanoff et al., 2009a,b) and the evolution of cave-adapted populations in karstic areas (Kosswig and Kosswig, 1940; Konec et al., 2015; Mojaddidi et al., 2018). These examples of phenotypic divergence underscore the potential of this species to contribute to our understanding of adaptive diversification across different temporal and spatial scales.

Moreover, A. aquaticus is a key mediator of ecosystem level processes, being involved in a range of important trophic and non-trophic interactions in freshwater ecosystems. On the one hand, A. aquaticus is an efficient detritivore with a broad spectrum of diets from microbes to leaf litter, and thus, a major contributor to the recycling of nutrients and biomass (Carpenter and Lodge, 1986; Graça et al., 1994; Bjelke and Herrmann, 2005). On the other hand, A. aquaticus serves as a prey for mesopredators (e.g., fish, insects, and waterfowl; Hart and Gill, 1992; Hargeby et al., 2004), and acts as a host to parasites, endosymbionts, and epibionts (Cook et al., 1998; Dezfuli, 2000; Zimmer and Bartholmé, 2003).

The broad environmental distribution of A. aquaticus is considered to stem from its ability to cope with stressful environmental conditions (e.g., Aston and Milner, 1980; Maltby, 1995). For instance, the species is resilient to high levels of both organic and chemical pollution (Aston and Milner, 1980; Van Ginneken et al., 2017, 2019), and is able to bioaccumulate metals (Elangovan et al., 1999; Rauch and Morrison, 1999) – making it a well-suited study system also in ecotoxicology. There is a vast number of insightful studies exemplifying the relevance of this species for water quality assessment and for ecotoxicology (e.g., Rauch and Morrison, 1999; MacNeil et al., 2002; Christensen et al., 2013; Van Ginneken et al., 2017), as well as a recent review highlighting A. aquaticus as a model for biomonitoring (O’Callaghan et al., 2019; Figure 1), but we do not cover these aspects further here.

Finally, from a methodological point of view, individuals of A. aquaticus can be collected readily from the wild, and populations easily established and maintained over multiple generations in the laboratory at low-cost (e.g., Bloor, 2010, 2011). Asellus aquaticus is also well-suited for large scale phenotypic and genetic studies, with several phenotyping and genotyping tools already available, including a high throughput phenotyping pipeline (Lürig, 2021), a genome-wide linkage map and hundreds of genetic markers (Protas et al., 2011; Bakovic et al., 2021). This combination makes A. aquaticus highly amenable to controlled laboratory and mesocosm experiments (Rossi and Fano, 1979; Maltby, 1995; Lürig et al., 2019), as well as to in-depth genetic and phenotypic studies (e.g., Protas et al., 2011;, Lürig et al. 2019, Bakovic et al., 2021).

Areas of Integrative Research Using Asellus Aquaticus

Microbial Associations

The interactions between a host and its microbiome can have a substantial impact on organismal function and fitness and can mediate ecosystem processes (e.g., Douglas, 2014; Fisher et al., 2017; Hurst, 2017; Koskella et al., 2017; López-García et al., 2017). Isopods, such as A. aquaticus, are well-suited to studies on host-microbiome interactions as they bear a diverse community of bacteria and eukaryotic microorganisms inside and outside their bodies (Douglas, 1998; Wang et al., 2007; Fraune and Bosch, 2010; Gilbert et al., 2012; Dhanasekaran et al., 2021). A multitude of complex associations with microorganisms, ranging from intracellular associations to epibiotic symbiosis, have already been found or hypothesized to exist in A. aquaticus (Zimmer and Bartholmé, 2003; Wang et al., 2007; Bredon et al., 2020).

One of the most important functions provided by the microbiota is the ability to digest nutritionally challenging compounds, such as lignocellulose, that A. aquaticus and many terrestrial isopods, use as a major food source (Zimmer et al., 2001; Bredon et al., 2019, 2020). Such dietary endosymbiosis is thought to have been a key element during the radiation of isopods in terrestrial and freshwater habitats from a common marine ancestor (Zimmer and Bartholmé, 2003; Wang et al., 2007; Bouchon et al., 2016; Bredon et al., 2019, 2020).

Besides dietary endosymbiosis, the prevalence of the reproductive manipulator Wolbachia (Cordaux et al., 2012), and a diverse community of epibionts with understudied functions (Fontaneto and Ambrosini, 2010), make isopods promising study systems for host-microbiome interactions. In general, microbes may broaden host environmental tolerance and thereby allow hosts to have wide dietary niches, inhabit diverse abiotic environments, and cope with a variety of environmental stressors (Henry et al., 2021). Although little studied thus far in A. aquaticus, it seems possible that its broad environmental tolerance is, in part, achieved via host-microbiome interactions. Furthermore, dietary symbionts in A. aquaticus have the potential to directly mediate the role of their detritivore hosts in the ecosystems, which makes A. aquaticus, together with terrestrial isopods (Bouchon et al., 2016) also well-suited to explore the effects of symbiotic associations on ecosystem functioning (see section “Integration and Future Perspectives”).

Microbial Communities and Diet

The ability of isopods, including A. aquaticus, to break down cellulose and lignins (i.e., lignocellulose) from leaf litter is considered a crucial adaptation during its past colonization of freshwater habitats from marine ancestors (Zimmer et al., 2001, 2002a; Zimmer and Bartholmé, 2003). While marine isopods often feed on nutritious and easily digestible food sources, such as algae (Kennish and Williams, 1997; Wahlström et al., 2020), detritivores in freshwater ecosystems are often confronted with leaf litter and detritus of allochthonous origin (Grieve and Lau, 2018). This detritus typically has low nutrient levels and high concentrations of lignocellulose, phenolics, and other recalcitrant components of terrestrial plants (Webster and Benfield, 1986; Kritzberg et al., 2004; Cross et al., 2005; Solomon et al., 2008). Since most marine ancestors do not have the ability to degrade such compounds (Ray and Julian, 1952; Zimmer et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2007), it is hypothesized that the successful colonization of freshwater environments was facilitated by the adoption of gut microbial communities that produce enzymes for the digestion of recalcitrant plant detritus (Zimmer et al., 2001, 2002a; Bredon et al., 2019, 2020).

Asellus aquaticus is known to harbor bacterial endosymbionts in two digestive structures: the hepatopancreas (also called midgut gland; Wang et al., 2007; Bouchon et al., 2016; Bredon et al., 2019), a multilobed gland that is functionally analogous to the liver and pancreas of higher organisms (Brunet et al., 1994), and the hindgut (Zimmer and Bartholmé, 2003). The community of bacterial endosymbionts in the midgut gland produces digestive enzymes such as phenoloxidase and cellulase, allowing A. aquaticus to feed directly on recalcitrant allochthonous substrates (Robson, 1979; Zimmer and Bartholmé, 2003; Hasu et al., 2008; Bredon et al., 2020). Other crustacean detritivores (e.g., the amphipod Gammarus pulex; Zimmer and Bartholmé, 2003), and various terrestrial isopods (Wang et al., 2007; Kostanjšek et al., 2010; Bredon et al., 2020) also resort to enzymatic breakdown of leaf litter, but enzymes in these other species are produced by both host (Kostanjšek et al., 2010) and gut microbiota (Bredon et al., 2020). In contrast, A. aquaticus seems to mostly rely on its gut microbiome when digesting plant material of terrestrial origin (Bredon et al., 2020), providing evidence for a strong symbiotic relationship.

Similarly to other detritivores, A. aquaticus also relies on environmental bacteria for nutritional purposes via microbial establishment, i.e., microbial colonization of the substrate, which is thought to provide several benefits (Gessner et al., 1999). On the one hand, this microbial colonization results in a change of the physical and chemical status of terrestrial substrates (Gessner et al., 1999), preparing them for consumption by detritivores through enzymatic catalysis and leaf fragmentation (Bärlocher and Porter, 1986; Bärlocher, 1992). On the other hand, the algae, bacteria, and fungi colonizing the substrate and forming an extracellular polymeric substance matrix (e.g., biofilm; Flemming et al., 2007), acts directly as an important food source. Although A. aquaticus can feed on fresh plant material (e.g., macrophytes or filamentous algae; Marcus et al., 1978), it seems to prefer (and also grow faster on) substrates colonized by microbiota (Marcus et al., 1978; Rossi, 1985; Graça et al., 1993a; Bohmann, 2005). The optimal diet of A. aquaticus is likely to be a complex mix of components. For instance, algal compounds seem to be needed for optimal development, likely due to a specific fatty acid composition (Grieve and Lau, 2018). In addition, there is compelling evidence that A. aquaticus prefers fungal food sources, and even specific species of fungi, over other parts of the biofilm (Rossi and Fano, 1979; Graça et al., 1993a), possibly because higher growth rates can be sustained when feeding on phosphorus and nitrogen-rich fungi (Rossi and Fano, 1979; Graça et al., 1993b; Lürig and Matthews, 2021).

Microbial Reproductive Manipulators

A variety of microorganisms are known to affect reproduction and sex determination in arthropods (Stouthamer et al., 1990; Breeuwer and Jacobs, 1996; Groenenboom and Hogeweg, 2002), including isopods (e.g., Chebbi et al., 2019). Of these, the best studied is the intracellular bacterium Wolbachia, which may occur in as many as half of all arthropod species (Cowdry, 1923; Hilgenboecker et al., 2008; Weinert et al., 2015). Wolbachia can have a major impact on host fitness (Werren, 1997; Stouthamer et al., 1999; Werren et al., 2008; Becking et al., 2019) by for instance, protecting against viruses (Teixeira et al., 2008), providing nutrients (Brownlie et al., 2009) and, notably, by influencing reproduction and life-histories (Dobson et al., 2002; Cao et al., 2019). Being a maternally transmitted symbiont, Wolbachia has evolved mechanisms to promote its spread, either by inducing cytoplasmic incompatibility or by skewing offspring sex ratios toward females via feminization, male killing, or the induction of parthenogenesis (O’Neill et al., 1997). In the terrestrial isopods Armadillidium nasatum (Becking et al., 2019) and A. vulgare (Chebbi et al., 2019), Wolbachia is thought to have influenced sex chromosome evolution and cytoplasmic sex determination.

Asellus aquaticus is known to carry Wolbachia (Bouchon et al., 1998), and different lines of evidence suggest that sex determination in this species may be influenced by both sex determining genes and maternally transmitted factors (Vitagliano et al., 1994), such as Wolbachia. On the one hand, the karyotype of A. aquaticus consists of eight homomorphic chromosome pairs (2n = 16) in both sexes (Montalenti and Rocchi, 1964; Salemaa, 1979; Valentino et al., 1983). However, the presence of a difference in heterochromatin areas for one chromosome pair in males from an Italian population has been taken as an indication for an incipient sex chromosome differentiation in A. aquaticus (Rocchi et al., 1984; Volpi et al., 1992). On the other hand, analyses of hybrid offspring between populations differing in male to female ratios indicate that sex ratio in A. aquaticus can be highly dependant on the origin of the mother (Vitagliano et al., 1994). This potentially indicates a role for a maternally transmitted factor, such as Wolbachia, in sex determination and population sex ratios (e.g., Charlat et al., 2003). Empirical evidence suggests that switches from Wolbachia-driven to genetic sex determination may take place in different taxa (Charlat et al., 2003), including terrestrial isopods (O’Neill et al., 1997). Given these observations, and known Wolbachia effects in other arthropods, including isopods, A. aquaticus is an excellent candidate to evaluate how interactions between host genetics and reproductive symbionts influence sex determination, and to provide insight into the eco-evolutionary implications of these interacting processes.

Epibionts

In addition to the various internal microbes referred to above, aquatic crustaceans, including A. aquaticus, also host specialized epibiotic communities (e.g., bacteria, diatoms, protozoa, and rotifers) on their exoskeleton (Cook et al., 1998; Fontaneto and Ambrosini, 2010). While it is generally assumed that the only benefit is phoretic (i.e., mode of transportation for the epibiont; May, 1989), it has also been argued that certain rotifer species may feed on host-derived material (e.g., feces or bacteria; Beauchamp, 1932). Studies in pelagic species, such as copepods and cladocerans, suggest that surface colonization by protozoans may also be associated with predator avoidance (Steffan, 1967; Thiery and Cazaubon, 1992), increased oxygen uptake (Steffan, 1967; Thiery and Cazaubon, 1992), or greater intake of suspended matter (Green, 1974). The extensive colonization of certain body regions or organs, such as the gills in A. aquaticus, could also be harmful and potentially indicate a parasitic association (Cook et al., 1998). However, despite epibionts being common in aquatic invertebrates, we still know little about the nature of these colonizations and the impact they may have on host performance (Cook et al., 1998).

Interestingly, in A. aquaticus the composition of epibiotic communities can vary within (e.g., between dorsal and ventral body parts) and across individuals, as well as between populations (Cook et al., 1998). Asellus aquaticus may be a particularly suitable system to investigate the spatial and temporal dynamics of epibionts communities on their host. The bi-phasic sequential molting of A. aquaticus (Box 1) will induce time-restricted dispersal and recolonization events for epibionts (Cook et al., 1998) that could be easily traced. Moreover, organisms with bi-phasic molting never shed the entire exoskeleton at once, which may allow for more stable associations between hosts and epibionts compared to other arthropods. Further work in this direction could help elucidate the ecological and evolutionary significance of epibiont–host organism interactions.

Biotic Interactions

Interactions between organisms and their environment can influence organismal performance and evolutionary trajectories and, when involving keystone species such as A. aquaticus, have overreaching consequences for the entire food web or ecosystem (e.g., Visser et al., 2012). Classic examples in different taxa illustrate the extent to which competitive, predator-prey, and host-parasite interactions can influence ecosystem function (Levine, 1976; Berryman, 1992; Gandon and Van Zandt, 1998; Abrams, 2000; MacColl, 2011), such as, for instance, through trophic cascades (Best and Stachowicz, 2012; Walsh et al., 2016).

Asellus aquaticus is relevant for ecosystem functioning due to its role in organic matter processing and nutrient cycling within aquatic ecosystems, as well as in the aquatic-terrestrial interphase arising from its detritivory (i.e., it typically feeds on leaf litter fallen from trees) (Carpenter and Lodge, 1986; Graça et al., 1994; Bjelke and Herrmann, 2005). Moreover, A. aquaticus is an important component of aquatic food webs, as it serves as a prey for mesopredators (e.g., Hart and Gill, 1992; Hargeby et al., 2004) and as a host for trophically transmitted parasites (e.g., Dezfuli, 2000). However, and despite a long history of research on A. aquaticus, surprisingly little is known about the extent to which interactions between these isopods and their environment link ecosystem and evolutionary processes (i.e., eco-evolutionary dynamics) (Hairston et al., 2005, Matthews et al., 2011; Schoener, 2011; Miner et al., 2012; Reznick et al., 2019). Given the high degree of phenotypic variation (e.g., Hargeby et al., 2005; Lürig et al., 2019), and its role as a keystone species, A. aquaticus is a well-suited model for evolutionary ecosystem studies, such as those related to resource use and biotic interactions.

Detritivory and Competition

Among and within species variation in the ability to tolerate suboptimal environmental conditions and to utilize diverse diets can be major determinants of species distribution and competitive exclusion (Hoffmann and Hercus, 2000; Liancourt et al., 2005; de Araújo et al., 2014). Competitive interactions may be particularly relevant when considering keystone species, such as A. aquaticus, as they have the potential to influence key ecosystem processes (Lindeman, 1991; Bianchi, 2020). Benthic detritivores, in general, play a central role for the functioning of ecosystems aquatic environments with high productivity (Jeppesen et al., 1998; Bjelke and Herrmann, 2005; Adey and Loveland, 2007; Kenna et al., 2017). Therefore, differential environmental tolerances and competitive exclusion between co-existing benthic detritivore species can have important ecosystem level effects (Wallace and Webster, 1996; Little et al., 2019).

Asellus aquaticus seems to be a strong competitor to more environmentally sensitive taxa: it is resilient to both low oxygen levels (Edwards and Learner, 1960; Maltby, 1995; Bjelke, 2005) and high levels of unionized ammonia (Maltby, 1995), which presumably allows A. aquaticus to occupy a broader range of oligo- and eutrophic benthic microhabitats than some other detritivore taxa (e.g., Hargeby, 1990a; Graça et al., 1994; Bjelke, 2005). It has even been suggested that interspecific differences in physical and chemical tolerances may explain the non-overlapping distribution patterns between A. aquaticus and G. pulex (Costantini et al., 2005), a common gammarid amphipod that competes with A. aquaticus for space and for detrital resources (Åbjörnsson et al., 2000; Van den Brink et al., 2017). Specifically, A. aquaticus tolerates pollution better than does G. pulex, which may explain why it often dominates in polluted areas (Whitehurst and Lindsey, 1990; Whitehurst, 1991).

Another aspect that presumably makes A. aquaticus a strong competitor in benthic detrital food chains is its ability to use a broad range of dietary resources (Marcus et al., 1978; Willoughby and Marcus, 1979; Graça et al., 1993b; Lürig and Matthews, 2021). Asellus aquaticus is, in fact, able to use diets that important competitors cannot utilize. It is possible that a specific gut microbial community facilitates the digestion of epiphytic fungi and bacteria (see also section “Microbial Communities and Diet”), which then allows A. aquaticus to harness dietary sources that are not available to other benthic detritivores. The ability to digest fungi may be especially beneficial because of their high nutritional value and near optimal elemental ratios (i.e., low C:P and C:N ratios; Elser et al., 2000), which in turn, can positively affect growth and pose a competitive advantage for A. aquaticus.

Given the aforementioned specific trophic features, and the possibility for diet manipulations, A. aquaticus is amenable to tackling a broad range of food web related topics. Interesting and ecologically relevant questions include aspects related to differential resource base (e.g., biofilm versus leaf litter; Grieve and Lau, 2018; Santschi et al., 2018; Gossiaux et al., 2020) and to how species-specific responses to diverse pollutants (e.g., pesticides versus fungicides) influence food webs (Burdon et al., 2016; Feckler et al., 2016; Stamm et al., 2016).

Predator-Prey Interactions

Benthic species, such as A. aquaticus, are a key food source for mesopredators in aquatic ecosystems and disturbances in their populations can have far-reaching consequences (Rask and Hiisivuori, 1985; Brooks et al., 2009), and strongly influence nutrient cycling across food webs (Schmitz et al., 2018). Hence, understanding predator-prey interactions of keystone species can provide core insight into the role of biotic interactions in nature. Asellus aquaticus is an important component of aquatic food webs (Murphy and Learner, 1982; Hart and Ison, 1991; Graça et al., 1994; Persson and Eklöv, 1995) because it is a prey species to different invertebrate (e.g., insects; Thompson, 1978; Cockrell, 1984; Brooks et al., 2009) and vertebrate predators (e.g., fish, Rask and Hiisivuori, 1985; Hart and Gill, 1992; Salvanes and Hart, 1998; Harris et al., 2011). Locally, isopods can make up a very large proportion of a predator’s diet (up to 70%) (Rask and Hiisivuori, 1985) and can therefore be a main factor in determining the occurrence and abundance of predator species (Herrmann, 1984).

Predation can also be a major evolutionary driver behind trait divergence, from behavior to morphology and life histories (Johnson and Belk, 2020). Predator avoidance mechanisms range from behavioral avoidance to cryptic coloration and are sometimes highly dependent on the type of microhabitat (e.g., with or without shelter) and on how individual phenotypes match the microhabitat (e.g., via crypsis) (e.g., Edelaar et al., 2008, 2017; Ruxton et al., 2019; van Bergen and Beldade, 2019). For organisms such as A. aquaticus that typically hide in vegetation, macrophyte patches or leaf litter deposits can offer both nutritional resources and shelter from predation either via direct structural effect or via cryptic background matching (Hargeby et al., 2005; Warfe et al., 2008; Kovalenko et al., 2012). Intriguingly, A. aquaticus has evolved cryptic pigmentation presumably as a consequence of visual predation, whereby close matching of isopod body color and microhabitat background color has been found (Hargeby et al., 2004, 2005; Lürig et al., 2019) (see section “Ecotype Divergence Within Lakes” and Figure 2).

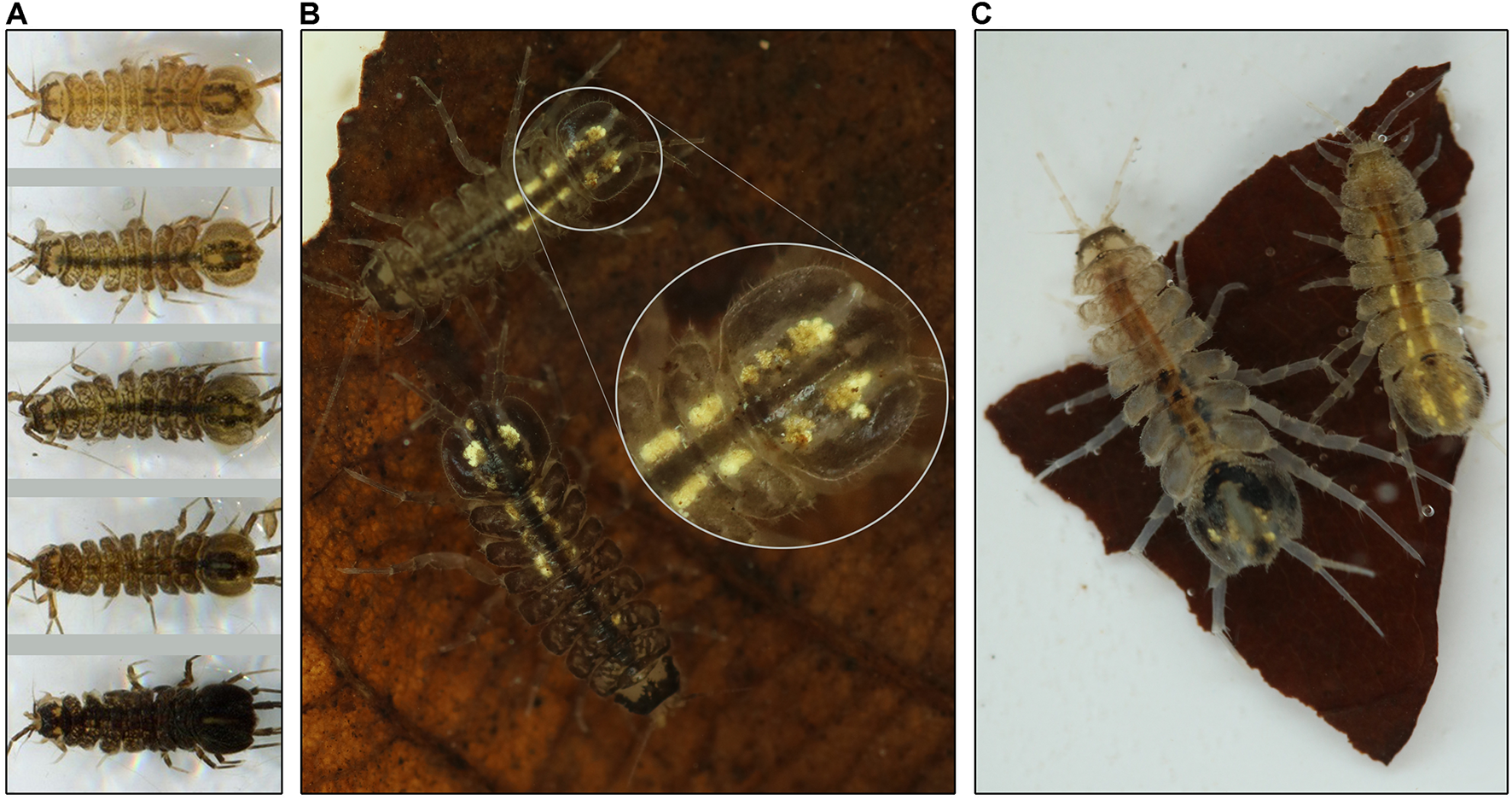

FIGURE 2

Determinants of body pigmentation in Asellus aquaticus.(A) Images show differences in pigmentation between individuals of A. aquaticus. Pigmentation in this species is a highly variable trait, ranging from light to dark brown in surface water forms (e.g., Hargeby et al., 2004, 2005; Lürig et al., 2019) to nearly colorless cave forms (Protas et al., 2011). Similar to other isopods, integumental pigmentation is mainly composed of the ommochromes xanthommatin and ommatin, which are deposited inside specialized skin cells (Needham, 1970). (B) Image showing two individuals of A. aquaticus with visible Zenker cells, which are a specialized cell type homologous to the tegumental glands of terrestrial isopods (Ter-Poghossian, 1909; Gorvett, 2009). In A. aquaticus, the Zenker cells form conspicuous fluorescent yellow stripes along thoracic and abdominal segments (Zimmer et al., 2002b). Zenker cells help in the storage of metabolic waste products, such as uric acid, which appears in large amounts in A. aquaticus (Lockwood, 1959). The storage of uric acid, along with increased pigmentation, has been proposed as a mechanism to avoid cell toxicity (Linzen, 1974). Furthermore, the ecological relevance of the conspicuousness produced by Zenker cells has been associated with predation (Zimmer et al., 2002b), in that the fluorescence emitted by Zenker cells causes intraspecific variation in external patterns, affecting individual visibility, and influencing predation risk (Zimmer et al., 2002b). (C) Image of individuals of A. aquaticus infected with Acanthocephalan parasites, which have disruptive effects on the pigmentation patterns (Oetinger and Nickol, 1981). Infected individuals generally show darker pigmentation in the posterior-most region of the body (Needham, 1974; Dezfuli et al., 1994), making them more conspicuous (Dezfuli et al., 1994), and potentially influencing trophic transmission to the next host (i.e., different species of freshwater fish) (e.g., Hasu et al., 2007; Benesh et al., 2009).

There is increasing evidence for a tight relationship between behavior, morphology, and performance (Garland and Losos, 1994), as well as for variation in that relationship across environments (Broom and Ruxton, 2005; Lürig et al., 2016). However, the extent to which variation in that relationship, in turn, influences ecoysytem function, is still poorly understood. Furthermore, anti-predator responses can come at a cost to other performance traits, which may also influence ecosystem function. For instance, in A. aquaticus, predator presence decreases feeding efficiency (Åbjörnsson et al., 2000; Calizza et al., 2013) and thus, it can indirectly affect nutrient cycling and decomposition of organic material. Given the potential for predator-prey interactions and phenotypic habitat matching in A. aquaticus, this species is suitable for investigating the impact of differential predation pressures on ecosystem function.

Host-Parasite Interactions

Another type of biotic interaction in A. aquaticus that has the potential to strongly influence ecosystem function is that of host-parasite interactions involving multiple trophic levels. Host-parasite interactions can influence population performance and dynamics at different scales (e.g., Penczykowski et al., 2016) from within-host (e.g., direct effect of parasites on host survival or reproduction) up to community-level effects (e.g., impact on the structure of the communities of their hosts) (Dobson and Hudson, 1986; Minchella and Scott, 1991). This is especially true in the case of transmission of parasites across two trophic levels via keystone species, such as A. aquaticus and fish.

Host-parasite interactions that have been best studied in A. aquaticus are those between the isopod and acanthocephalan parasites, including Acanthocephalus lucii, A. anguillae, and A. balkanicus (Brattey, 1983; Dezfuli, 2000; Amin et al., 2019). Species of acanthocephalans that frequently and specifically infect A. aquaticus have different species of fish – for example, perch, stickleback and/or eels – as their subsequent and final host (Dezfuli et al., 1994; Dezfuli, 2000; Lyndon and Kennedy, 2001; Hasu et al., 2007). The adult acantocephalan worms reside and reproduce in the fish intestine and transmission to A. aquaticus occurs when the isopod ingests the parasite’s eggs that have been released to the environment via fish feces. Once inside the isopod host, the eggs hatch, penetrate the gut wall, and the parasite subsequently develops inside the host body cavity (Dezfuli, 2000). Intriguingly, these trophically transmitted parasites are known for host manipulation, such as the induction of behavioral changes (e.g., infected isopods hide less than uninfected isopods; Benesh et al., 2008; Seppälä et al., 2008), increased body size, and/or changes in pigmentation (Brattey, 1983; Hasu et al., 2007; Benesh et al., 2009; see Figure 2). These parasites can also castrate female isopods by inhibiting secondary sexual development (Brattey, 1983; Dezfuli et al., 1994). While little is known about the consequences of parasitism on individuals and populations of A. aquaticus, the transmission of parasites across trophic levels, appeals to using this species in studies exploring ecosystem consequences and eco-evolutionary feedbacks of host-parasite interactions.

Phenotypic Divergence

Asellus aquaticus provides some fascinating examples of phenotypic variation across different temporal (i.e., within and between generations) and spatial (e.g., continental versus local) scales, making it a well-suited system to study the evolution of biological diversity. On a continental scale, multiple subspecies have formed throughout the species range (Box 2) and cave forms have evolved in multiple karstic areas in Europe (e.g., Konec et al., 2015; Mojaddidi et al., 2018). The latter has led to subterranean phenotypic adaptation and to the formation of troglomorphic subspecies (e.g., Kosswig and Kosswig, 1940; Turk-Prevorčnik and Blejec, 1998). On a regional scale, A. aquaticus has undergone repeated ecotype differentiation within lakes (Eroukhmanoff et al., 2009a,b), with divergence having been associated to both genetic (e.g., Bakovic et al., 2021) and plastic effects (Karlsson et al., 2010). Locally, A. aquaticus shows evidence of assortative mating (e.g., Ridley and Thompson, 1979; Adams et al., 1985), which has the potential to contribute to sexual selection and reproductive isolation (Jiang et al., 2013).

Available evidence indicates that the extensive phenotypic variation in A. aquaticus is driven, at least in part, by natural selection, offering an opportunity to explore the relationship between environmental variation and adaptive diversification (Nosil, 2012). In general, when environmental variation is spatially structured and gene flow is restricted, natural selection can promote local adaptation (Kawecki and Ebert, 2004; Hereford, 2009), whilst high spatio-temporal environmental variation can favor phenotypic plasticity (Via and Lande, 1985; Schlichting and Pigliucci, 1998; DeWitt and Scheiner, 2004; Lafuente and Beldade, 2019). Ultimately, the relationship between local adaptation and plasticity depends on the magnitude of the environmental differences and on the potential for dispersal and gene flow (Sultan and Spencer, 2002; Garant et al., 2007; Ghalambor et al., 2007; Räsänen and Hendry, 2008). The broad range of natural and man-made environments that the species inhabits, and the different temporal and spatial scales on which phenotypic variation occurs, make A. aquaticus well-suited for increasing our understanding of adaptive divergence across different scales.

Surface-Cave Divergence

The ability A. aquaticus to adapt to a broad range of conditions is particularly striking in surface versus cave environments in different parts of Europe (Kosswig and Kosswig, 1940; Sket, 1994; Turk et al., 1996; Turk-Prevorčnik and Blejec, 1998; Verovnik et al., 2004, reviewed in Verovnik and Konec, 2019). Generally, cave living organisms often show a pattern of multiple independently evolved populations (e.g., Bradic et al., 2013), and thus represent great systems to study mechanisms of adaptation and the prevalence (or lack thereof) of convergent and parallel evolution (e.g., Jeffery, 2009; Liu et al., 2017). Studies on surface-cave divergence of A. aquaticus have thus far provided the most extensive and detailed genetic and developmental analyses (and resources) for this species, which has resulted in extensive efforts to establish this species as an invertebrate model for studies of cave evolution (Protas et al., 2011; Konec et al., 2015; Mojaddidi et al., 2018; Verovnik and Konec, 2019). Based on molecular genetic analyses, the colonization of cave habitats happened independently in several locations, suggesting parallel or convergent evolution in subterranean populations (Konec et al., 2015). Closely related (and potentially ancestral) surface populations are still existent in many locations, and cave and surface forms can interbreed in captivity, which suggests incomplete reproductive isolation, and facilitates genetic and phenotypic analyses (Mojaddidi et al., 2018; Re et al., 2018).

As in many other cave-adapted taxa (e.g., Yoshizawa et al., 2012; Soares and Niemiller, 2013), cave populations of A. aquaticus show reduced or absent ommatidia (i.e., optical units that make up the compound eye of arthropods), depigmentation, elaborated sensory structures, and elongation of some appendages (Turk et al., 1996; Prevorcnik et al., 2004; Konec et al., 2015). Genetic mapping analyses have revealed that pigmentation (Figure 2) and eye loss are under the control of a few genes of large effect, with closely related traits (e.g., eye loss and eye reduction) mapping to distinct regions (Protas et al., 2011). Interestingly, the same genomic regions (and even same genes) underlie the convergent loss of pigmentation in two different cave populations of A. aquaticus (Pivka and Rak Channels in Slovenia; Re et al., 2018), potentially indicating that evolutionary change may have happened via fixation of standing genetic variation from an ancestral surface lineage (Re et al., 2018).

In contrast to their surface water ancestors, cave-living A. aquaticus show physiological differences involving energy saving mechanisms, such as lower locomotor and metabolic activity (Jemec et al., 2017), as well as differences in energy biomarkers (Zidar et al., 2018). Similar physiological specializations have been described for other cave crustaceans (Hervant et al., 1997, 1999; Simcic et al., 2005). The reduced locomotion of cave-dwelling A. aquaticus has been taken as an indication that cave adaptation is primarily driven by the increased stability of cave environments (Jemec et al., 2017; Verovnik and Konec, 2019). However, phenotypic divergence in morphometric traits, which appears to have happened independently of ecological parameters (e.g., nutrient availability or habitat type; Konec et al., 2015), has been taken as evidence for a role of darkness as a main selective agent (Culver et al., 2010). Further work on A. aquaticus could help understanding how different environmental factors (and their interactions) influence phenotypic divergence in cave animals (Culver et al., 2010; Pipan and Culver, 2012; Soares and Niemiller, 2013; Gross et al., 2014).

Many of the morphological differences (e.g., pigmentation, eye size, and antennal article number) between cave and surface forms of A. aquaticus arise during embryonic development (Mojaddidi et al., 2018) and involve the differential expression of genes with diverse putative functions, such as phototransduction, photoreception, and eye development (Gross et al., 2019). Transcriptomic analyses of cave (versus surface) individuals also revealed allele-specific gene expression (Stahl et al., 2015; Gross et al., 2019), suggesting that cis-regulatory changes in gene expression may be responsible for phenotypic differences. Since cis-regulatory changes are known to constitute an important part of the genetic basis of adaptation (see Wray, 2007), A. aquaticus could provide insight into the contribution of cis-regulatory changes to cave adaptation. Moreover, studies using this species in comparison with other taxa, could help to elucidate the extent to which cave related traits are under the control of the same or of different genes in independent phylogenetic lineages.

Ecotype Divergence Within Lakes

Among the best-studied cases of phenotypic and ecological differentiation in A. aquaticus is the intralacustrine divergence into distinct ecotypes, which provides an excellent opportunity to study microevolutionary responses in both space and time. In several different lakes in Sweden, A. aquaticus has – over the last two decades – diverged phenotypically into two different ecotypes that associate with different vegetation types (Eroukhmanoff and Svensson, 2009, 2011; Harris et al., 2011): the ancestral reed (Phragmites australis) habitat and the novel stonewort (Chara tomentosum) habitat (Hargeby et al., 2004, 2005; Eroukhmanoff et al., 2009a). Phenotypic divergence in morphology and behavior in A. aquaticus is thought to have happened as the result of differences in visual predation pressure; invertebrate predators are most prevalent in reed habitats, while fish dominate the stonewort habitat (Hargeby et al., 2004; Eroukhmanoff and Svensson, 2009, 2011). These ecological conditions have favored crypsis in stoneworts, with isopods having smaller bodies, lighter pigmentation, and being behaviorally more cautious than those inhabiting reed habitats (Hargeby et al., 2004; Eroukhmanoff and Svensson, 2009, 2011).

Furthermore, mate choice experiments between individuals from the two ecotypes indicate that the combined effects of natural selection and size-assortative mating may have promoted morphological differentiation (Hargeby and Erlandsson, 2006). In addition to color polymorphism and anti-predator traits, demographic parameters also differ between the reed and stonewort ecotypes, with population densities being generally lower in the reed than in the stonewort habitat (Karlsson et al., 2010). These differences in demography have been associated with the differences in sexual behavior whereby the stonewort ecotype shows lower propensity to initiate precopula than the ancestral reed ecotype (Karlsson et al., 2010). At the same time, mating propensity is plastic (i.e., dependent on sex ratio) in the novel stonewort ecotype but not in the ancestral reed ecotype (Karlsson et al., 2010), suggesting that variation in mate choice (and its plasticity) may have contributed to ecotype divergence (Karlsson et al., 2010).

Anti-predator specializations have been found in several geographically separate and genetically independent stonewort-inhabiting populations in Sweden, indicative of parallel evolution (Hargeby et al., 2005; Eroukhmanoff and Svensson, 2009; Eroukhmanoff et al., 2009a). This divergence is, at least partly, under genetic control, such as seen for divergence in pigmentation between ecotypes (Hargeby et al., 2004). Molecular data suggests that A. aquaticus populations adapted to stonewort habitats have emerged independently and repeatedly, rather than emerged in one of the lakes and then subsequently dispersed to the others (Eroukhmanoff et al., 2009a).

Similar to the threespine stickleback model of ecological speciation (reviewed in Hendry et al., 2009) and other freshwater fish (Seehausen and Wagner, 2014; Skúlason et al., 2019), A. aquaticus occurs at wide geographic scales and in areas with different degrees of connectivity (e.g., across lakes, lake-stream, surface water-cave, and within lakes) providing the opportunity for future avenues of research on selection-gene flow balance and the speciation continuum (Nosil, 2012). In this vain, A. aquaticus constitutes an excellent invertebrate model system to study the mechanisms underlying parallel evolution in multiple independently evolved populations of a single species (Losos et al., 1998; Schluter et al., 2004; Boughman et al., 2005). Intralacustrine divergence further provides potential for understanding the interplay between natural selection (e.g., via vegetation and predation) and gene flow (e.g., effect of geographic distance and habitat suitability on potential for dispersal within ecosystems) (Richardson et al., 2014).

Sexual Selection and Assortative Mating

Assortative mating, whereby individuals with particular phenotypes mate with one another in a non-random fashion, is a main contributor to sexual selection (Jiang et al., 2013; Kopp et al., 2018), and has the potential to drive reproductive isolation (Lande, 1981; Panhuis et al., 2001; Ritchie, 2007). One of the most prevalent forms of assortative mating in many taxa, including A. aquaticus, is that with respect to size (i.e., size-assortative mating) (Harari et al., 1999; Shine et al., 2001; Jiang et al., 2013; Green, 2019).

Asellus aquaticus shows sexual dimorphism in body size: for any given age, males are larger than females (Box 1). Moreover, within populations, mating is size assortative in that larger males tend to pair with larger females (Ridley and Thompson, 1979). Mating in A. aquaticus is assortative also with respect to fluorescence (produced by Zenker cells), but the relevance of this is little studied so far (but see Zimmer et al., 2002b; Figure 2). Several lines of evidence suggest that sexual selection is important in A. aquaticus. Mating is preceded by a precopulatory stage (called amplexus or mate guarding), whereby males grasp onto the females with specialized legs (i.e., specialized fourth pair of pereopods) and wait for days until the female molts into a fertile state (see Box 1). Inter-male competition is likely to influence patterns of non-random mating as larger males are more likely to pair, and to displace small males from pairs (Verspoor, 1982; Adams et al., 1985; Hargeby and Erlandsson, 2006). In line with this, larger males seem to have a mating advantage (Crespi, 1989), which might determine the observed patterns of assortative mating in A. aquaticus (Ridley and Thompson, 1979).

The precopulatory mate guarding behavior in A. aquaticus imposes an intimate association between body size (and assortative mating) and reproductive success. In other species, precopulatory mate guarding can be subject to sexual conflict (Cameron et al., 2003; Arnqvist and Rowe, 2005; Wedell et al., 2006), mainly because the optimal duration of mate guarding can differ between males and females (Jormalainen et al., 1994; Jormalainen, 1998). In A. aquaticus, the probability of successful mate guarding increases with male size (Ridley and Thompson, 1979; Verspoor, 1982). However, males also tend to choose females that are closer to being fecund (Ridley and Thompson, 1979; Verspoor, 1982). This could potentially represent a compromise between pairing with a larger, more fecund female, and pairing with a smaller, but easier to carry female. All together, the relationship between pre-copulatory mate guarding and assortative mating in A. aquaticus offers an excellent opportunity to test empirically theories on life history evolution (Stearns, 1992; Roff, 1993; Wedell et al., 2006).

Integration and Future Perspectives

As stated at the onset of our review, understanding how organisms and ecosystems respond to environmental change requires integrative efforts that explore organism-environment interactions at different hierarchical levels (Lewontin, 1983; Kokko and López-Sepulcre, 2007; Post and Palkovacs, 2009; Matthews et al., 2014). Here, we have presented A. aquaticus, a species that is broadly distributed, ecologically relevant, experimentally tractable, and that has a well-studied natural history, as a suitable study system for integrative studies across different temporal, spatial, and biological scales. Building on the knowledge that we have synthesized in this review, we next suggest some specific avenues of integrative research using A. aquaticus. We particularly highlight two areas: first, the study of relationships between spatio-temporal environmental variability and phenotypic plasticity, and second, the study of host-microbiome interactions in relation to ecosystem function.

Spatio-Temporal Environmental Variability and Phenotypic Plasticity

Understanding how organisms cope with environmental variation has been a central theme in evolutionary biology and in ecology, and is becoming more relevant in the context of climate change (Charmantier et al., 2008; Chevin et al., 2010; Moritz and Agudo, 2013). Organismal traits can respond to environmental variation in different manners, and the type of adaptive responses depends on the predictability and the timescale of the environmental fluctuations (Leimar et al., 2006; Reed et al., 2010; Botero et al., 2015). Reversible phenotypic changes (via plasticity) are thought to be more likely under rapid or fluctuating environmental change, while genetic adaptation is considered more likely in response to long-term (and often gradual) environmental changes (Rando and Verstrepen, 2007; Stomp et al., 2008). Moreover, phenotypic plasticity is thought to be favored when environmental fluctuations are predictable (Lande, 2009; Botero et al., 2015; Tufto, 2015) and in the presence of gene flow (Sultan and Spencer, 2002; Crispo, 2008). Plasticity is often (but not always) adaptive (i.e., environmentally induced phenotypic change leads to a better match between phenotype and selective environment; e.g., Gotthard and Nylin, 1995; Ghalambor et al., 2007). In such cases, adaptive plasticity can allow populations to persist under heterogeneous environments, including those changing as a consequence of human activity (Charmantier et al., 2008; Merilä and Hendry, 2014; Sgrò et al., 2016).

Asellus aquaticus is well-suited for empirically testing the relationship between environmental variability and the evolution of plasticity (Tufto, 2000; Leimar et al., 2006; Lande, 2009). Given that the species occurs in temporally stable cave and deep water environments (e.g., Turk et al., 1996; Protas et al., 2011), as well as in spatio-temporally variable lakes and streams (e.g., Murphy and Learner, 1982; Hargeby, 1990b; Hargeby et al., 2007), genetic trait polymorphism or plasticity may be favored in different contexts (Sultan and Spencer, 2002; Richardson et al., 2014). The available evidence for ecogeographical variation in phenotypic traits in A. aquaticus provides a solid foundation for future studies aiming to understand genetic and phenotypic variation in fitness related traits.

One trait of particular interest in this context is body pigmentation. As stated above (section “Surface-Cave Divergence” and “Ecotype Divergence Within Lakes”; Figure 2), pigmentation in A. aquaticus is highly variable, may influence predation risk in lakes (Eroukhmanoff and Svensson, 2009; Eroukhmanoff et al., 2009a) and can be dramatically reduced in caves (Verovnik and Konec, 2019). Both surface water and cave studies in A. aquaticus suggest that color polymorphism is, at least in part, genetically determined (Hargeby et al., 2004; Protas et al., 2011). On the other hand, two recent studies also show extensive diet-based plasticity in A. aquaticus pigmentation (Lürig et al., 2019; Lürig and Matthews, 2021). This nutritional plasticity in body color has been hypothesized to help reduce the negative effects of high protein diets. Tryptophan, an amino acid whose concentration can vary strongly across diets, is toxic at high intracellular levels, but by forming inert pigments from soluble tryptophan, arthropods may avoid the negative effects of high protein diets (Linzen, 1974). Along these lines, variation in A. aquaticus pigmentation within lakes could also be explained by an alternative, but not mutually exclusive, hypothesis to predator-mediated selection: variation in pigmentation between habitats could reflect avoidance of cell toxicity when feeding on different dietary resources (e.g., reed versus stonewort).

Cave adapted A. aquaticus provide another intriguing case of evolution of pigmentation – likely in part via developmental plasticity of biochemical pathways (e.g., Bilandžija et al., 2020). The aforementioned different lines of evidence provide the foundations to explore how genes and environmental conditions co-determine the production and evolution of pigmentation and, in a broader sense, of phenotypic variation.

Host-Microbiome Interactions and Ecosystem Function

In the quest of predicting the impact of anthropogenic activity on nature, researchers are trying to understand the relationship between biodiversity and ecosystem functioning (Loreau et al., 2001; Hooper et al., 2005; Hillebrand and Matthiessen, 2009). In the past, this has been mostly studied from the perspective of the effects of environmental stressors on either individuals, populations, or ecosystems (Hoffmann and Parsons, 1997; Steinberg, 2012). However, it is becoming increasingly clear that an isolated perspective on the different scales of ecological organization may be overly simplistic and could lead to imprecise predictions of biodiversity–ecosystem function (Isbell et al., 2018). It is therefore important to take a more integrative perspective investigating biodiversity–ecosystem function across different spatial and temporal scales (Gonzalez et al., 2020).

Asellus aquaticus seems particularly well-suited to explore the inter-connectedness and reciprocal interactions across levels of ecological organization. This is, in particular, because of the potentially tight relationships between host microbiome (see section “Microbial Associations”), host performance, and ecosystem function. For instance, the accumulation and decomposition rate of organic material can be influenced by both environmentally acquired (Bärlocher and Porter, 1986; Bärlocher, 1992) and endosymbiotic microbes in the isopod digestive system (Robson, 1979; Zimmer and Bartholmé, 2003; Hasu et al., 2008). Gut microbial endosymbionts are likely to allow A. aquaticus to exploit a range of different diets (Robson, 1979; Zimmer and Bartholmé, 2003; Hasu et al., 2008; Bredon et al., 2020) (see section “Detritivory and Competition”). Furthermore, gut bacteria can provide protection against secondary infections by intestinal parasites (e.g., Buffie and Pamer, 2013; Knutie, 2018), further strengthening the potential role of the microbiome in host fitness. How variation in microbiome composition influences the processing of different nutritional sources, and the extent to which this affects rates of decomposition and defenses against parasites are, in general, not well understood. Further investigations of microbiome assembly mechanisms in A. aquaticus can help to elucidate whether and how dietary and/or parasitic symbiotic associations cascade to ecosystem function.

Concluding Remarks

Here we have summarized key aspects of knowledge from 150 years of research on A. aquaticus to highlight its potential as a broadly usable model system for the biological realm. The quest to better understand the evolutionary significance and ecological relevance of organism-environment interactions will benefit from integrative efforts that combine concepts and approaches across multiple disciplines. This integrative effort should include research across the interfaces between different disciplines and, importantly, include more animal systems, such as A. aquaticus, that permit inquiries from individual to ecosystem scale (Lewontin, 1983; Kokko and López-Sepulcre, 2007; Post and Palkovacs, 2009; Matthews et al., 2014). Increasing the diversity of study systems in ecology and evolution can also help to unravel the wondrous diversity of evolutionary processes in natural populations and how this diversity influences ecological processes (Bolker, 2014; Duffy et al., 2021).

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Statements

Author contributions

EL, ML, BM, and KR conceived the idea for the review. EL wrote the first draft of the manuscript, with contributions from ML and MR. MR carried out research on distribution patterns presented in Box 2. ML conducted bibliographic research presented in Figure 1, both with contributions from EL. EL produced the remaining figures. All authors contributed to the development and discussion of ideas, writing and editing of the manuscript, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

Financial support was provided by Eawag Discretionary Funds to KR (PSP 5221.00492.013.03). ML received financial support from the Swiss National Science Foundation through an Early Postdoc. Mobility Grant with the No. P2EZP3_191804 and from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 898932.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fevo.2021.748212/full#supplementary-material

References

1

ÅbjörnssonK.DahlJ.NyströmP.BrönmarkC. (2000). Influence of predator and dietary chemical cues on the behaviour and shredding efficiency of Gammarus pulex.Aquat. Ecol.34379–387. 10.1023/A:1011442331229

2

AbramsP. A. (2000). The evolution of predator-prey interactions: theory and evidence.Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst.3179–105. 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.31.1.79

3

AdamsJ.GreenwoodP.RichardP.TaniaY. (1985). Loading constraints and sexual size dimorphism in Asellus aquaticus.Behaviour92277–287.

4

AdcockJ. A. (1979). Energetics of a population of the isopod Asellus aquaticus: life history and production.Freshw. Biol.9343–355. 10.1111/j.1365-2427.1979.tb01519.x

5

AdeyW. H.LovelandK. (2007). “Detritus and detritivores: the dynamics of muddy bottoms,” in Dynamic Aquaria (Third Edition), edsAdeyW. H.LovelandK. (London: Academic Press), 303–327. 10.1016/B978-0-12-370641-6.50027-3

6

AlfredJ.BaldwinI. T. (2015). New opportunities at the wild frontier.eLife4:e06956. 10.7554/eLife.06956

7