- Department of Biological Sciences, Wellesley College, Wellesley, MA, United States

We argue that developmental hormones facilitate the evolution of novel phenotypic innovations and timing of life history events by genetic accommodation. Within an individual’s life cycle, metamorphic hormones respond readily to environmental conditions and alter adult phenotypes. Across generations, the many effects of hormones can bias and at times constrain the evolution of traits during metamorphosis; yet, hormonal systems can overcome constraints through shifts in timing of, and acquisition of tissue specific responses to, endocrine regulation. Because of these actions of hormones, metamorphic hormones can shape the evolution of metamorphic organisms. We present a model called a developmental goblet, which provides a visual representation of how metamorphic organisms might evolve. In addition, because developmental hormones often respond to environmental changes, we discuss how endocrine regulation of postembryonic development may impact how organisms evolve in response to climate change. Thus, we propose that developmental hormones may provide a mechanistic link between climate change and organismal adaptation.

The Role of Hormones in Metamorphosis

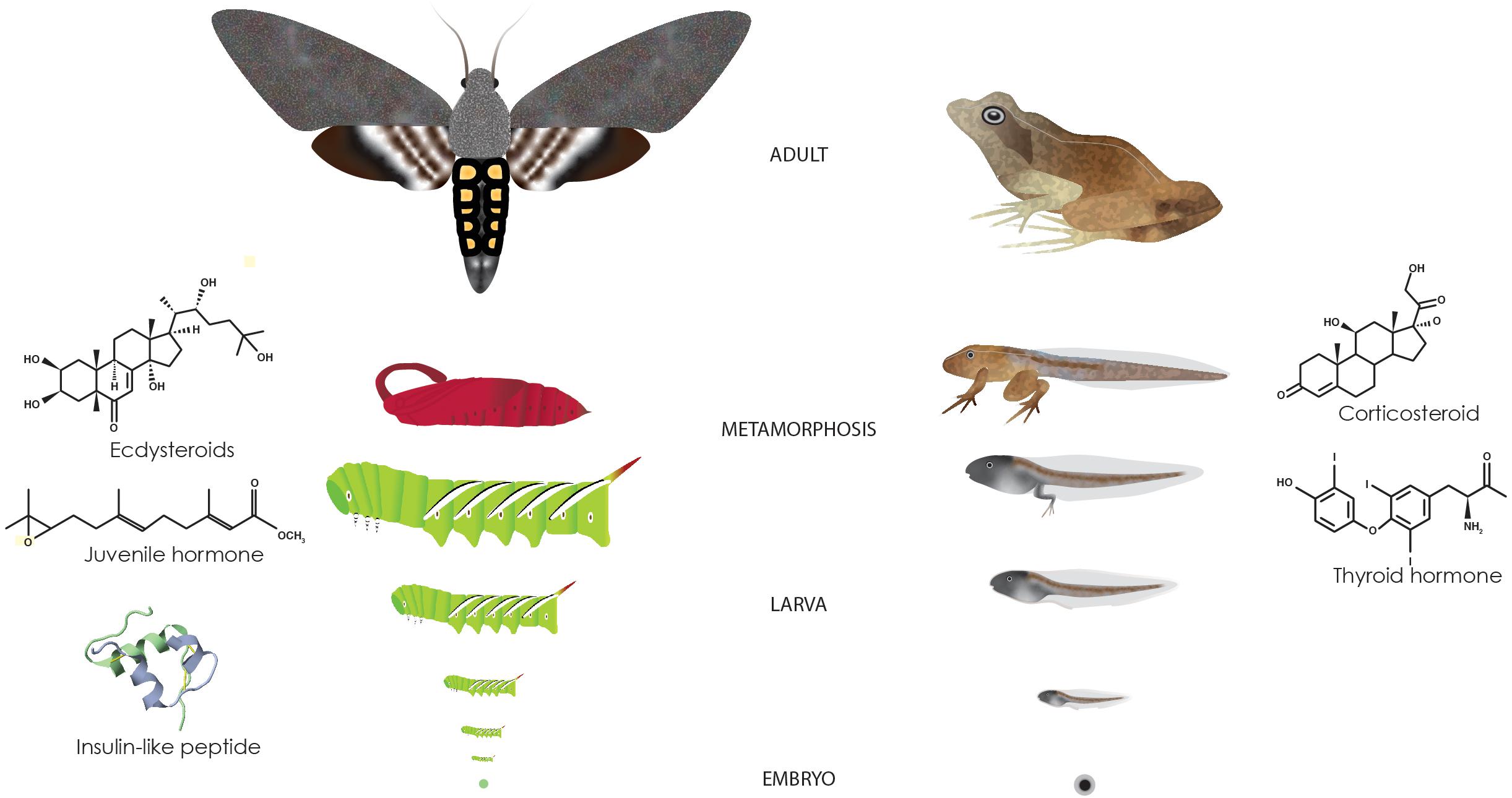

Approximately 80% of animals undergo metamorphosis—the transition from a larval to an adult stage (Figure 1; Werner, 1988). One key tenant of metamorphosis is that the pre-metamorphic or larva stage and its subsequent adult stage often occupy different habitats (Bishop et al., 2006). The change in habitat (such as from aquatic to terrestrial, or terrestrial to aerial) may be accompanied by a shift in nutrition and feeding behavior or different means of locomotion which necessitates distinct morphological, physiological and/or behavioral adaptations. In many metamorphic species, such as frogs and insects, the larvae devote much of their resources to growth, whereas the adults divert much of their energy toward reproduction and dispersal. In other species, especially marine invertebrates, the larval stage is dedicated toward dispersal and much of their growth commences once they settle. Because of their distinct roles, the larvae and adults often look nothing like each other. Metamorphosis then serves as a transitional period during which tissue remodeling and adult development can occur. Moreover, metamorphosis allows larval and adult life stages to evolve independently although certain aspects of the adult stage may depend on the larval development and experiences (Moran, 1994; Lee et al., 2013; Collet and Fellous, 2019; Moore and Martin, 2019).

Figure 1. Metamorphosis in insects and vertebrates. Holometabolous insects and anurans grow as a larva and undergoes metamorphosis before developing into an adult. Major hormones involved in this process are depicted next to the drawings. Insulin-like peptide is Dilp5 from Drosophila (generated using FirstGlance in Jmol at http://first-glance.jmol.org).

Hormones play salient roles during metamorphosis. In response to either internal or environmental signals, dynamics of endocrine regulators begin to change toward the end of the larval life. These endocrine regulators are secreted into the circulatory system and orchestrate complex metabolic and/or morphogenetic processes in target tissues. In organisms that have adult body plans that differ radically from larval body plans, key body plan regulators that were involved in embryonic development, such as Hox genes, play major roles in shaping the adult body (Gaur et al., 2001; Lombardo and Slack, 2001; Tomoyasu et al., 2005; Chesebro et al., 2009; Hrycaj et al., 2010; Chou et al., 2019). Although these endocrine regulators act during other developmental stages, metamorphosis is a time when they coordinate drastic changes in gene expression and morphogenesis in multiple tissues (White et al., 1999; Arbeitman et al., 2002; Helbing et al., 2003; Li and White, 2003; Alves et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2019). In addition, hormones play an important role in determining body size by impacting both how fast and how long an animal grows (Lorenz et al., 2009; Nijhout et al., 2014).

Below, we discuss how these endocrine processes might influence organismal evolution in the face of climate change. We will first discuss how hormones orchestrate the dramatic morphological changes that occur during metamorphosis. We then discuss how hormones respond to environmental conditions. Next, we will explore how hormones may bias evolution and how organisms might overcome constraints imposed by hormones. Furthermore, we will introduce the concept of “developmental goblet” to offer a visual representation of how hormones might impact the evolution of metamorphic organisms. Finally, we will explain how hormones can facilitate the evolution of novel traits by a process called genetic accommodation and discuss how climate change might impact the evolution of organisms by impacting their endocrine system.

Despite the prevalence of metamorphosis across the animal kingdom, metamorphosis likely evolved several times independently (Wolpert, 1999) although the molecular machinery used for metamorphosis was likely present in the common ancestor of all bilaterians (Fuchs et al., 2014). Therefore, the specific developmental events during metamorphosis differ between taxa. Our review focuses on vertebrates and insects where endocrine regulation of development has been best studied. Amphibians are one of the models for understanding the impacts of ecological changes as they are particularly susceptible to ecological disturbances (Hopkins, 2007). Insects are the most diverse group of organisms. In particular, those that undergo complete metamorphosis (the Holometabola, which have distinct larval, pupal and adults stages), have enjoyed extraordinary success (Yang, 2001). Ecological services of insects provide major economic contributions (Losey and Vaughan, 2006). With global climate change leading to mismatches in the timing of metamorphosis and flowering time, both insect and plant communities face dire consequences (Hegland et al., 2009; Høye et al., 2013; Kudo and Ida, 2013; Forrest, 2016).

Metamorphic Hormones in Vertebrates and Non-insect Invertebrates

Within a particular phylum, the specific endocrine regulators involved in metamorphosis appear to be similar. In most vertebrates, thyroid hormone signaling is a key endocrine pathway that regulates growth, development/morphogenesis and metabolism (Rabah et al., 2019). Thyroid hormone is produced and secreted from the thyroid gland and plays a chief role in metamorphosis in amphibians and fish (Gudernatsch, 1912). The main form of thyroid hormone secreted from the thyroid gland is thyroxine (T4), which is biologically inactive and is subsequently converted to the biologically active triiodothyronine (T3), which coordinates metamorphosis (Denver et al., 2002). This conversion is mediated by the enzyme type II iodothyronine deiodinase (Davey et al., 1995). In target tissues, thyroid hormone enters the cell and regulates the expression of target genes in several different ways. In vertebrates, T3 typically binds to the nuclear Thyroid hormone receptor (TR) (Sap et al., 1986; Weinberger et al., 1986), which together with the co-receptor retinoid co-receptor (RXR), bind to DNA and regulate transcription (Zhang and Kahl, 1993; Zhang and Lazar, 2000). The peak in thyroid hormone titers coincides with the beginning of metamorphosis and coordinates myriad morphological and physiological changes from resorption of the tail to growth of limbs and remodeling of the gut (Shi, 2000; Brown and Cai, 2007). Different tissues of a tadpole undergo metamorphic changes at distinct time points. For example, a metamorphosizing tadpole grows its limbs before losing its tail so that it can continue to swim while the limbs grow out. This tissue specific timing of metamorphosis is regulated by the distinct timing of appearance of mRNAs encoding TR, RXR and type II iodothyronine deiodinase (Yaoita and Brown, 1990; Kawahara et al., 1991; Wong and Shi, 1995; Shi et al., 1996; Cai and Brown, 2004). Thyroid hormone is both necessary and sufficient for metamorphosis in teleost fishes. For example, when flounder larvae are exposed to T4, they can accelerate metamorphosis, leading to small juveniles, whereas disruption of thyroid hormone production by thiourea leads to retention of larval traits (Inui and Miwa, 1985). Exogenous thyroid hormone is also sufficient to induce early metamorphosis in larvae of the grouper, Epinephelus coioides (de Jesus et al., 1998).

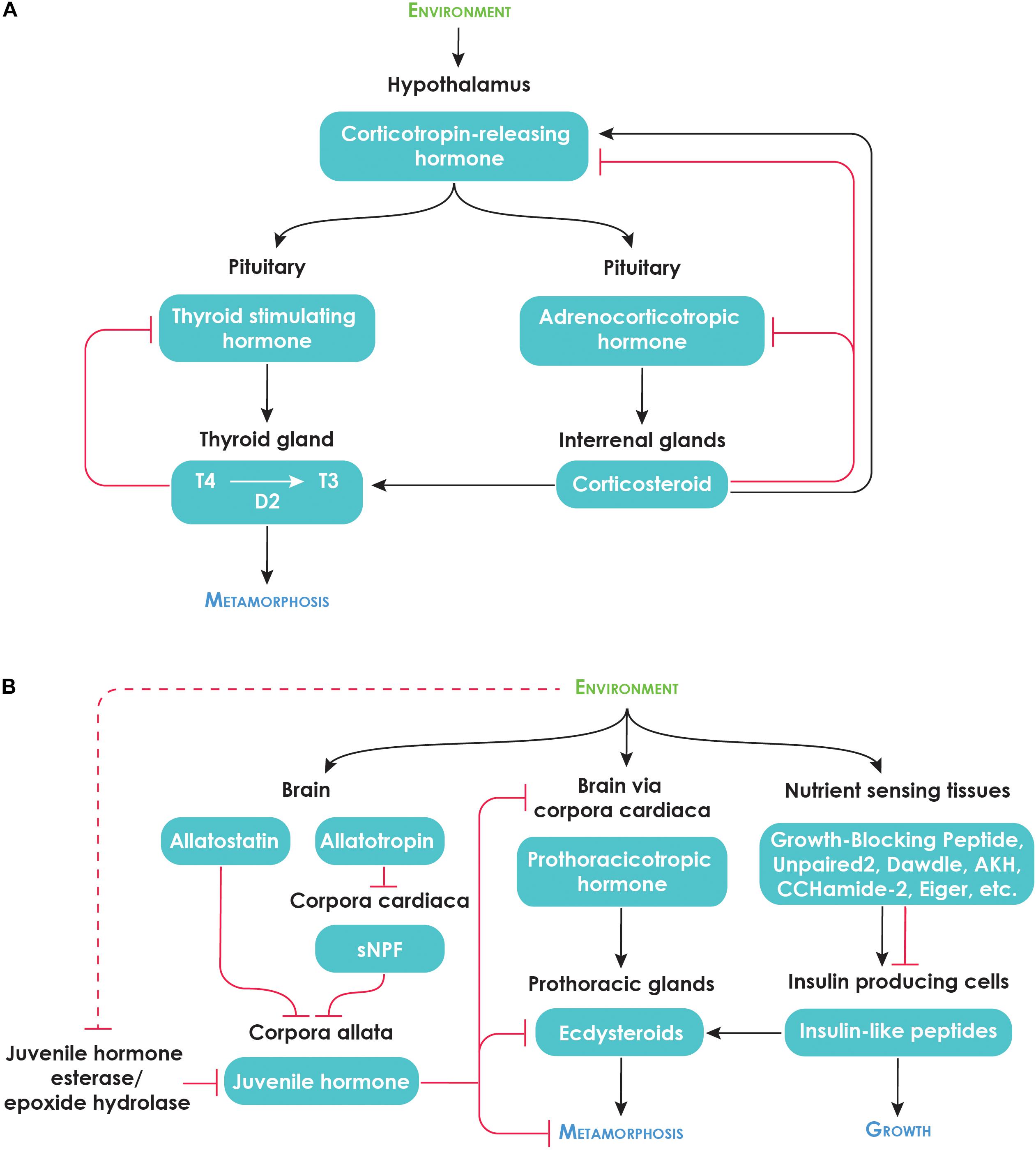

Thyroid hormone is part of the hypothalamic–pituitary–thyroid (HPT) axis (Figure 2A). As in mammals, thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), which is secreted from the pituitary gland, stimulates the production of thyroid hormone. In amphibians, TSH release is in turn regulated by corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH) from the hypothalamus rather than the thyrotropin-releasing hormone as is the case in mammals (Denver, 1999). CRH is a potent regulator of metamorphosis and appears to overcome the negative feedback of thyroid hormone on TSH release (Manzon and Denver, 2004). In teleost fishes, the role of CRH in regulating thyroid production appears to be limited to some species (Larsen et al., 1998; Campinho et al., 2015).

Figure 2. Neuroendocrine regulation of metamorphosis. (A) Metamorphic regulation of amphibians [Modified from Denver (2013)]. (B) Hormonal regulation of insect growth and metamorphosis. The details of JH regulation are based on lepidopteran studies. Many of the regulators secreted by the nutrient-sensing tissues were identified in Drosophila melanogaster. We do not yet know how conserved these factors are across all insects. Dotted red line indicates effect of stress on JH esterase activity.

The HPT axis interacts with the hypothalamic–pituitary–interrenal (HPI) axis, which responds to stress. The HPT axis begins with the hypothalamus releasing CRH, which stimulates the anterior pituitary to release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) (Figure 2A). ACTH acts on the interrenal glands to release corticosteroids, the key mediator of stress responses.

Corticosteroids also interact with the thyroid hormone pathway and regulate the developmental changes induced by thyroid hormone. The application of hydrocortisone accelerates T3- and T4-induced metamorphosis in Bufo bufo, Rana hechsheri and Rana pipiens (Frieden and Naile, 1955). Corticosterone was also found to stimulate T3-induced metamorphosis in Xenopus laevis (Gray and Janssens, 1990). Corticosteroids act on tissues by enhancing tissue sensitivity to thyroid hormone: Aldosterone and corticosterone increase T3 binding in tadpole tails (Niki et al., 1981; Suzuki and Kikuyama, 1983), and cultured tadpole tails exposed to corticosteroids express higher transcript levels of type II deiodinase and TR (Krain and Denver, 2004; Bonett et al., 2010). It is thus possible that the production of corticosteroids due to environmental stressor can accelerate metamorphosis by enhancing tissue sensitivity to thyroid hormone (Wada, 2008; Denver, 2021; Figure 2). The evidence for teleost fishes is more ambiguous: Although cortisol can enhance the impacts of T3 on fin-ray resorption of the Japanese flounder, Paralichthys olivaceus, in vitro, the timing of metamorphosis is not impacted by cortisol in vivo (de Jesus et al., 1990). The lack of in vivo effects may be because sufficient amount of cortisol is produced endogenously (de Jesus et al., 1990).

Thyroid hormone can play an essential role during metamorphosis of other Deuterostomes (Box 1), including several Echinoderm species (Chino et al., 1994; Heyland and Hodin, 2004; Heyland et al., 2006) and possibly also ascidians (Patricolo et al., 1981, 2001). Whether thyroid hormone acts via TR is not as well-established in these non-vertebrate Deuterostomes although TR is present in all Deuterostomes studied to date (Taylor and Heyland, 2017). Intriguingly, recent studies have also suggested the involvement of thyroid hormone signaling in accelerating molluscan metamorphosis (Fukazawa et al., 2001; Taylor and Heyland, 2017). Although regulators of corticosteroid action have been identified outside vertebrates (Baker, 2010), the role of corticosteroids during metamorphosis in these species remains unknown.

BOX 1. Terms used in this review.

| Terms used in this review | Definition |

| Cryptic genetic variation | Hidden genetic variation of a trait that is revealed under environmental stress. This genetic variation contributes to genetic accommodation of a phenotype in a population of organisms |

| Deuterostomes | The animals include chordates and echinoderms and are characterized by the development of the anus before the mouth during embryogenesis. Its sister group is called the protostomes, which develop the mouth before the anus. |

| Developmental bias | A bias on the production of certain phenotypes due to the underlying developmental system |

| Developmental constraint | A limitation on the production of certain phenotypes due to the underlying developmental system |

| Developmental drive | A positive drive that leads to the production of certain phenotypes due to the underlying developmental system |

| Developmental goblet | A model for metamorphic organisms depicting that the phylotypic stage and metamorphosis represent the times when development is most conserved. |

| Developmental hourglass | A model for embryogenesis that shows that the mid-embryonic stage called the phylotypic stage is the time of highest developmental conservation. |

| Genetic accommodation | An evolutionary process by which an environmentally or mutationally induced novel phenotype either becomes fixed or becomes readily induced by small environmental fluctuations in a population. It is characterized by either an increase or decrease in phenotypic plasticity |

| Genetic assimilation | A special case of genetic accommodation whereby an environmentally induced novel phenotype becomes fixed in a population even without the initial environmental input. In this case, phenotypic plasticity of the trait disappears and becomes robust (or canalized) |

| Hormonal pleiotropy or hormonal integration | Hormonal pleiotropy or hormonal integration occurs when a hormonal system influences more than one distinct trait. |

| Modularity | The degree to which a trait can develop and evolve independently of another. A module in a biological system can be defined at the molecular, cellular or tissue level. |

| Phenotypic plasticity | The ability of an organism with the same genotype to give rise to different phenotypes depending on the environment |

| Phylotypic stage | A developmentally conserved stage that occurs during mid-embryogenesis. Each phylum is thought to have a characteristic phylotypic stage |

| Physiological homeostasis | The ability of the endocrine system to respond to the environment so that developmental and metabolic processes can proceed normally. We propose that physiological homeostasis is key to an organism’s ability to cope with climate change and suggest that genetic variation in physiological homeostasis might dive the process of genetic accommodation |

| Polyphenisms | A special case of phenotypic plasticity where two or more distinct phenotypes arise as a consequence of a change in the environment |

Metamorphic Hormones in Insects

Before undergoing metamorphosis, most insects undergo several larval molts—the process involving the shedding of the exoskeleton to allow for growth. Within insects, the main developmental hormones are juvenile hormone (JH) and ecdysteroids (Nijhout, 1998; Truman, 2019; Figure 1). Generally, periodic surges of the 20-hydroxyecdysone (20E) trigger larval-larval molting as well as the initiation of metamorphosis. During the larval stage, JH prevents a larva from undergoing metamorphosis and therefore came to known as the “status quo hormone” (Riddiford, 1996). JH alters the effects of 20E action and inhibits metamorphic genes from being activated (Nijhout, 1998; Liu et al., 2009; Jindra et al., 2013, 2015). When bound to the Ecdysone receptor (EcR), 20E activates a transcriptional cascade of genes which induces molting (Riddiford et al., 2000) and adult tissue morphogenesis by activating a transcription factor called Ecdysone-induced protein 93 (E93) (Belles and Santos, 2014; Jindra, 2019; Truman and Riddiford, 2019). Conversely, JH binds to its receptor Methoprene-tolerant (Met) and induces the expression of Krüppel homolog 1 (Kr-h1), which represses E93 (Belles and Santos, 2014). Together, these regulators comprise the MEKRE93 pathway, which appears to be highly conserved across most insects studied to date (Belles, 2019, 2020). During metamorphosis, these regulators play critical roles in regulating metamorphic timing (Rountree and Bollenbacher, 1986; Mirth et al., 2005; Yamanaka et al., 2013; Hatem et al., 2015; Nijhout, 2015) and hence the final body size (Nijhout and Williams, 1974; Caldwell et al., 2005; Callier and Nijhout, 2013; Nijhout et al., 2014). We will discuss how hormones impact body size in Section “ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS ON METAMORPHIC HORMONES.” In addition, tissue proliferation and morphogenesis are also regulated by these hormones through their action on many target genes (Champlin and Truman, 1998a,b; Truman and Riddiford, 2002, 2007; Mirth et al., 2009; Herboso et al., 2015).

Just as the major metamorphic hormones of vertebrates are regulated by the brain, the production of metamorphic hormones in insects is also regulated by the brain, which can integrate various environmental cues (Figure 2B). Ecdysteroids production and release is regulated by prothoracicotropic hormone (PTTH), which is synthesized in the brain and released by the corpora cardiaca. JH synthesis and release is stimulated and inhibited by neuroendocrine factors called allatotropins and allatostatins, respectively, although the roles of these factors in the regulation of metamorphosis remain poorly understood (Goodman and Granger, 2005; Nijhout et al., 2014). Based on studies done in the silkworm, Bombyx mori, the allatostatins appear to act directly on the corpora allata whereas allatotropins appear to act indirectly by inhibiting Short neuropeptide F (sNPF), an inhibitor of JH biosynthesis that is produced in the corpora cardiaca (Kaneko and Hiruma, 2014; Figure 2B). JH activity is also modulated by JH degradation enzymes, JH esterase (JHE) and JH epoxide hydrolase (JHEH).

In addition to these two metamorphic hormones, Insulin-like peptides act on the Insulin/Target of rapamycin (TOR) signaling pathway and impact growth of insects (Koyama et al., 2020). This pathway plays an important role in regulating growth rate and determining the overall body size of the adult (Brogiolo et al., 2001; Geminard et al., 2009). Nutritional availability influences growth in almost all animals, and Insulin/TOR signaling pathway links growth of organisms to nutrient availability (Masumura et al., 2000; Ikeya et al., 2002; Geminard et al., 2009). In addition, this pathway plays a major role during metamorphosis to control tissue specific growth (Shingleton et al., 2005; Tang et al., 2011). Insulin-like peptides are often released in response to nutrients (Park et al., 2014) although in many cases, the interaction is indirect. For example, in fruitfly larvae, different tissues sense amino acids and sugars and release factors that then travel to cells that release insulin-like peptides (Figure 2B; Colombani et al., 2003; Geminard et al., 2009; Kim and Neufeld, 2015; Sano et al., 2015; Agrawal et al., 2016; Koyama and Mirth, 2016; Nässel and Broeck, 2016). Once released, insulin-like peptides travel to other parts of the body where they bind to the Insulin receptor, which activates a signal transduction cascade that ultimately leads to the phosphorylation of the forkhead transcription factor, Forkhead box O (FoxO), which regulates many developmentally and physiologically relevant genes (Koyama et al., 2020). The Insulin/TOR signaling pathway interacts with the ecdysteroid signaling pathway in a complex manner: Insulin/TOR signaling regulates the production of ecdysone, thus impacting the timing of metamorphosis (Mirth et al., 2005), while ecdysteroids also act to suppress Insulin signaling (Colombani et al., 2005; Mirth et al., 2014).

Environmental Impacts on Metamorphic Hormones

Although the production of the hormones mentioned above are regulated by gene products, they also respond readily to environmental conditions. In this section, we address how the environment can impact hormonal systems. Where possible, we also review how metamorphic hormones respond to these environmental cues and impact phenotypes.

Environmental Impacts of Vertebrate Metamorphic Hormones

In vertebrates, various environmental cues have been shown to influence hormone titers. For example, T4, T3 and corticosteroid levels all increase rapidly when tadpoles of the Western spadefoot toad, Scapiopus hammondii encounter decreasing water levels (Denver, 1998). These environmental changes are sensed by the brain neurons, which trigger an increase in CRH release from the hypothalamus, activating the HPT axis (Denver, 1998; Boorse and Denver, 2003). These changes are correlated with an earlier onset of and small body size at metamorphosis (Denver et al., 1998).

Temperature also impacts T3 and corticosteroid levels. In leopard frog tadpoles, Lithobates pipiens, corticosteroid levels peak earlier and T3 levels are elevated at higher temperatures (Freitas et al., 2017). Similarly, and tadpoles of the American bullfrog, Lithobates catesbeianus, also have elevated T3 levels at higher temperatures (Freitas et al., 2016). Higher temperatures are associated with faster growth and earlier onset of metamorphosis and smaller sizes at metamorphosis (Smith-Gill and Berven, 1979; Leips and Travis, 1994; Álvarez and Nicieza, 2002). Although hormonal changes could explain some of these changes, it is also possible that the phenotypic effects could also result from increased rates of intrinsic biochemical reactions and an overall reduction in cell size (Atkinson and Sibly, 1997).

Nutrition also impacts the timing of metamorphosis of anurans. There is a critical size above which food deprivation accelerates metamorphosis (Leips and Travis, 1994) and leads to smaller body sizes at the time of metamorphosis (Denver et al., 1998; Nicieza, 2000). These impacts appear to be regulated by hormones. T3 and corticotropin-releasing hormone levels are increased in food restricted mid-prometamorphic S. hammondii tadpoles (Boorse and Denver, 2003), and thyroid glands from starved late pre- to early prometamorphic Rana catesbeiana tadpoles also produce significantly higher amounts of T4 (Wright et al., 1999).

Environmental Regulation of Insect Metamorphic Hormones

In insects, a complex interaction between various endocrine regulators determines the timing of metamorphosis (Koyama et al., 2020). Within a particular species, the timing of metamorphosis can shift depending on environmental conditions, such as temperature and nutrient availability (Davidowitz et al., 2003). Both heritable differences in developmental time and plastic responses to the environment may involve alterations in endocrine regulators. In the lab, higher temperatures almost always lead to small adult body sizes by shortening the growth period (Davidowitz et al., 2003, 2004; Klok and Harrison, 2013). Observations in the field are much more complex and appear to depend on several factors including the number of generations, temperature, survival, and photoperiod (e.g., Roff, 1980; Atkinson, 1994; Imasheva et al., 1994; James et al., 1997; Horne et al., 2015).

Although studies have explored the cellular basis of temperature-dependent differences in body size (Partridge et al., 1994; Atkinson and Sibly, 1997; Zwaan et al., 2000), we still do not have a clear understanding of how temperature during the growth period impacts endocrine events that regulate life history transitions. However, the environment can impact hormones that regulate growth. A recent study on the cricket Modicogryllus siamensis demonstrated that higher rearing temperatures lead to enhanced Insulin/TOR signaling, leading to faster growth rate (Miki et al., 2020). Insulin/TOR signaling, however, does not impact the number of instars in M. siamensis; instead, the timing of JH decline impacts the duration of the juvenile growth period in a photoperiod-dependent manner (Miki et al., 2020). Thus, body size determination appears to rely on a complex interaction of endocrine regulators that respond differently to distinct environmental cues. Furthermore, we still do not understand how temperature influences the duration of larval stage, and more studies are needed to address this issue.

In addition, the environment can impact the timing of diapause and adult eclosion. Diapause is a dormant stage in insects that is equivalent to hibernation in vertebrates. Depending on the species, diapause can occur during different life history stages but metamorphic hormones often play prominent roles in regulating both the entry and duration of diapause (Chippendale and Yin, 1975; Zdarek and Denlinger, 1975; Sim and Denlinger, 2008, 2013). Environmental conditions, such as temperatures, can impact metamorphic hormones to influence the timing and duration of diapause (Turnock et al., 1986; Green and Kronforst, 2019; Cambron et al., 2021). We suspect that hormonal responses to environmental conditions are the norm, and that species can utilize these cues to coordinate life history transitions and phenotypic outcomes.

We end this section by discussing how hormones play prominent roles in polyphenisms. Polyphenic organisms can produce two or more distinct phenotypes from one genotype depending on the environment. A classic example of a polyphenism includes the polyphenisms of horned beetles where smaller male beetles have no horns on the head or the thorax, whereas larger male beetles grow horns (Kijimoto et al., 2013). These alternative morphs are both adaptive: Horned males use their horn as weapons to engage in male-male combat and guard the tunnels in which females are found, whereas hornless males “sneak by” the males by creating side-tunnels and gain access to the females (Emlen, 1997). Other examples of polyphenisms include the diet-induced polyphenisms of the caterpillars of Nemoria arizonaria, which can either develop into oak twig-resembling larvae or catkin-resembling morphs (Greene, 1989), and butterfly wing polyphenisms, where adult morphs adopt distinct wing color patterns depending on the season (Nijhout, 2003).

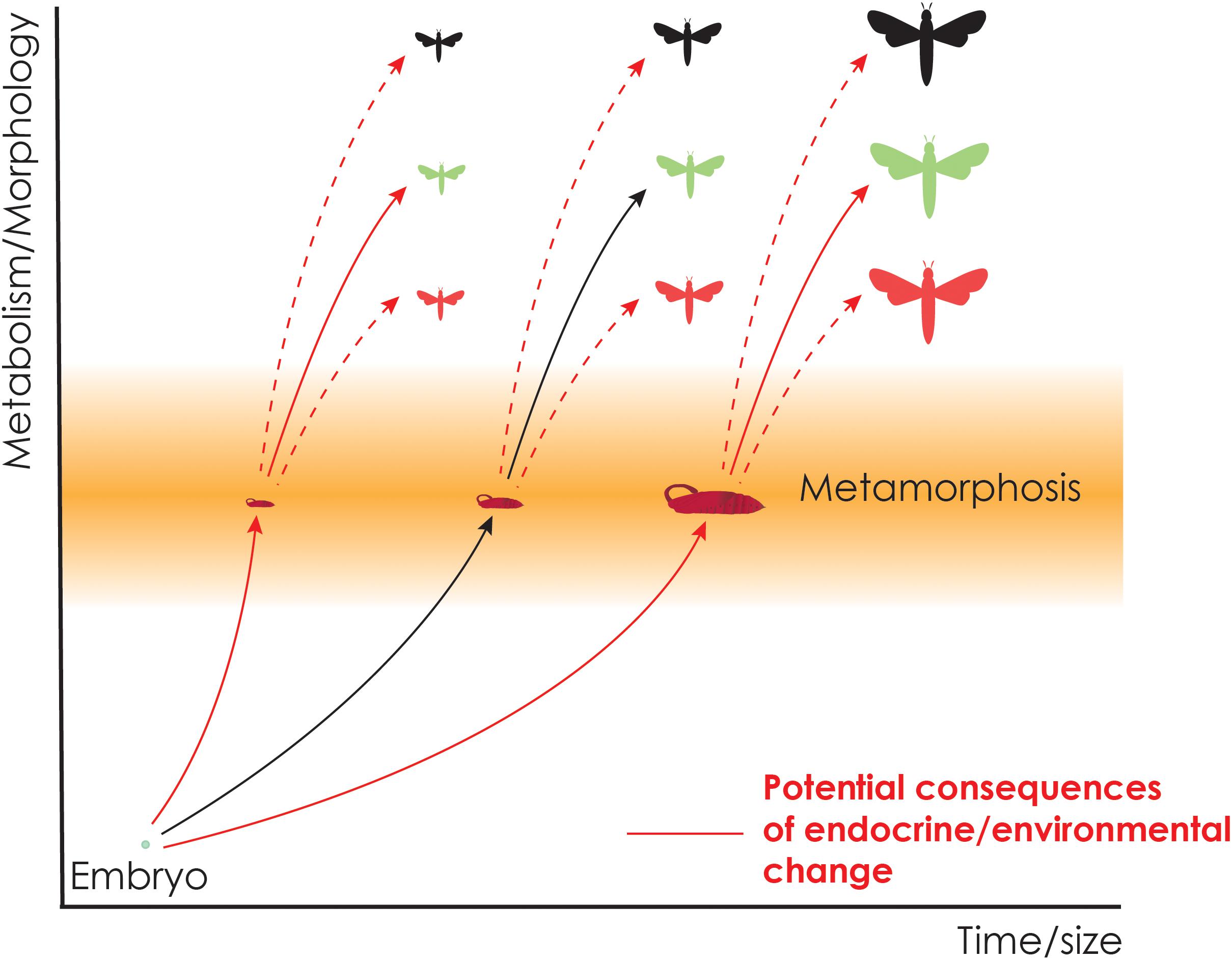

In polyphenisms, hormones play a salient role in instructing identical genomes to give rise to distinct adult morphologies that are adapted to particular environments (Nijhout, 1999, 2003). Because of the major effects developmental hormones have on adult tissue morphogenesis, small changes in the endocrine system can lead to profound changes during metamorphosis that results in distinct, and at times spectacular, adult phenotypes (Figure 3). In many polyphenisms, the endocrine centers integrate environmental stimuli encountered by the larva and adjusts the amount and timing of hormone production/release/response. For example, in the squinting bush brown butterfly Bicyclus anynana, the adult wing has eyespots that serve as defense against potential predators. Depending on the environment, both the ecdysteroid titers and the amount of ecdysone receptors expressed on the wing discs change (Monteiro et al., 2015) and impact the size of eyespots. In another butterfly, Precis coenia, the wings can be red and brown depending on the photoperiod and the temperature and their impacts on ecdysteroid levels during the early pupal stage (Rountree and Nijhout, 1995). Similarly, the alternative morphs of horned beetles are regulated by the titers of JH and ecdysteroids that are modulated by the amount of nutritional consumption (Emlen and Nijhout, 1999, 2001).

Figure 3. Potential consequences of environmental changes on the timing of metamorphosis and the development of adult phenotypes during metamorphosis. Adult body size can become larger or smaller through changes in the timing of metamorphosis (solid red lines), or distinct morphologies may develop in response to environmental changes (dotted red lines). These events are often regulated by endocrine processes that respond to environmental cues.

The Role of Hormones in Biasing Evolution

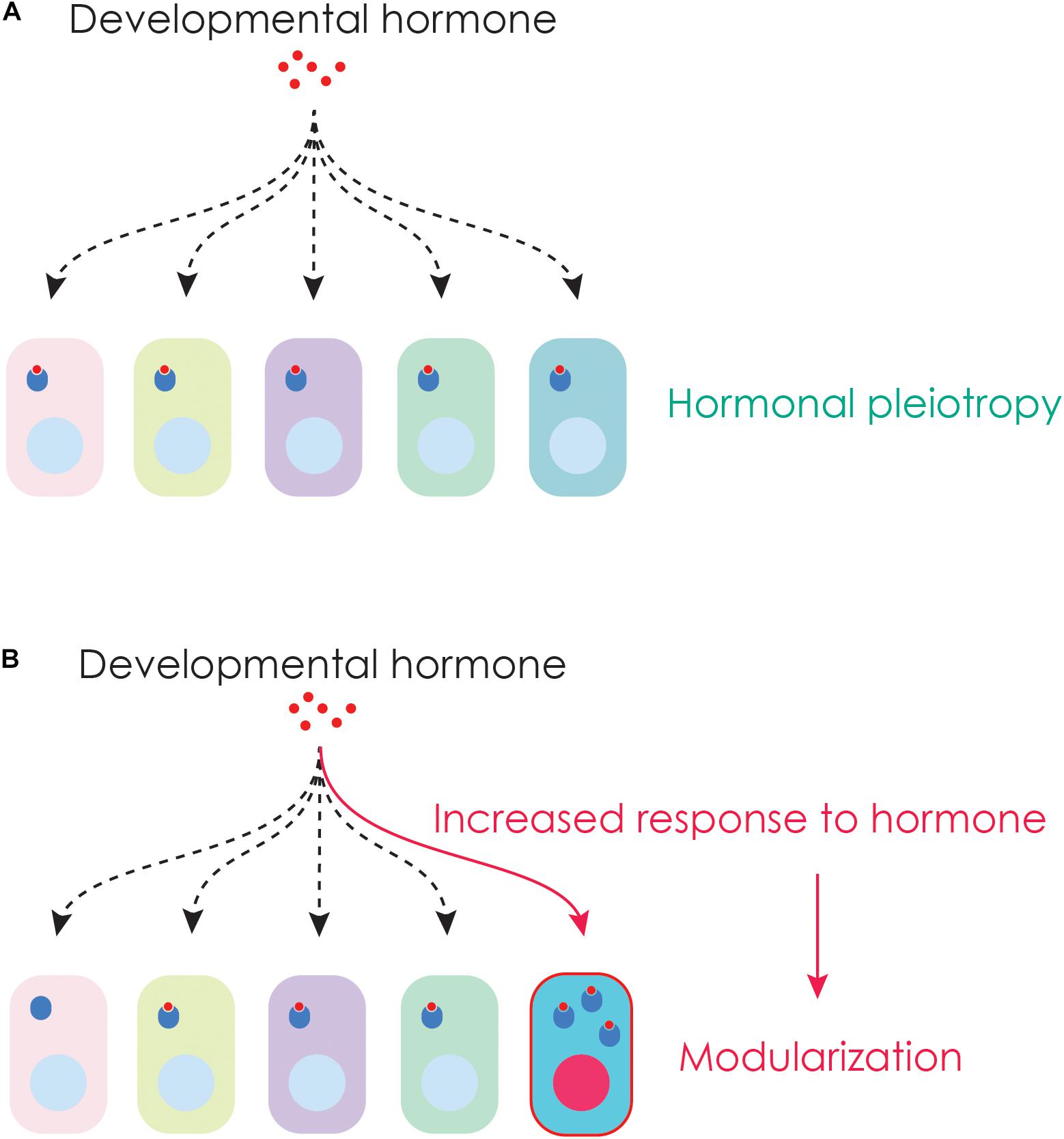

Metamorphosis is a time when the same developmental hormone coordinates changes in multiple tissues at once (known as hormonal pleiotropy or hormonal integration) (Box 1 and Figure 4A). Hormonal pleiotropy may influence the evolutionary trajectory of organisms. The effect of hormonal pleiotropy on the evolution of organisms is dependent on the way each tissue responds to hormones (Ketterson et al., 2009). If increases in hormones enhance fitness of all traits, hormonal systems will likely evolve rapidly. In contrast, if increases in hormones leads to fitness enhancing changes in some tissues but not others, antagonistic selection may constrain the evolution of the traits involved (McGlothlin and Ketterson, 2008). For example, a hormone might promote the growth of a body part which might contribute to increased fitness. If the same hormone also promotes growth of another structure which reduces fitness, hormonal pleiotropy may prevent one trait from increasing in size while reducing the size of the other trait. Although tissue responses to hormones can evolve over time, in the short term, hormonal pleiotropy can prevent rapid adaptive changes (Ketterson and Nolan, 1999). In addition, because the same metamorphic hormone can also regulate myriad of other traits beyond metamorphosis (Hayes, 1997; Flatt et al., 2005; Deal and Volkoff, 2020), endocrine regulation that has been shaped by natural selection during another life history stage could also impact endocrine regulation during metamorphosis. For example, in insects, JH plays roles in behavior (Huang et al., 1991; Sullivan et al., 2000; Zhang et al., 2020), reproduction (Bilen et al., 2013; Santos et al., 2019) and aging (Yamamoto et al., 2013). The non-metamorphic roles of thyroid hormone has not been studied as extensively in metamorphic vertebrates, but in fishes, it appears to impact embryonic survival, larval growth (Ayson and Lam, 1993; Alinezhad et al., 2020), and gonadal sex ratios (Sharma and Patino, 2013).

Figure 4. Hormonal pleiotropy and modularization. (A) Hormonal pleiotropy occurs when one hormone impacts many tissues at the same time. (B) Specific tissues can overcome constraints imposed by pleiotropy by evolving a unique response to hormones. Such changes could arise, for example, by the cells becoming more sensitive to hormones by producing additional hormone receptors.

In particular, in insects, many adult tissues (e.g., eyes, legs, wing) arise from the proliferating tissues called imaginal cells that proliferate in response to ecdysteroids (Champlin and Truman, 1998b; Nijhout and Grunert, 2002; Nijhout et al., 2007; Herboso et al., 2015). Programmed death of larval cells in various tissues is also coordinated by ecdysteroids (Nicolson et al., 2015). A change in the production of, or response to, metamorphic hormones can lead to catastrophic changes in the development of larvae, typically resulting in the death right before pupation (Cherbas et al., 2003; Davis et al., 2005; Tan and Palli, 2008; Ohhara et al., 2015). Moreover, tissue growth is coordinated by hormones such that disruption of one tissue can impact metamorphosis of the whole organism (Cherbas et al., 2003; Colombani et al., 2012).

This does not necessarily mean that developmental events regulated by metamorphic hormones always evolve slowly. If changes in the same hormone exert favorable changes across most tissues, selection on the endocrine system can allow for the rapid evolution of coordinated changes in multiple tissues and lead to dramatically altered phenotypes. The evolution of organisms that retain juvenile traits as reproductive adults (for example, the Mexican axolotl, the strepsipteran Xenos vesparum or the Japanese mealybug, Planococcus kraunhiae) often arise from changes in endocrine-dependent regulators (Rosenkilde and Ussing, 1996; Chafino et al., 2018; Vea et al., 2019). Thus, hormonal pleiotropy, at least in the short term, likely biases the way traits evolve and can acts as a developmental constraint (Smith et al., 1985) or a developmental drive (Box 1; Arthur, 2001).

The Role of Hormones in Facilitating the Evolution of Adult Phenotypes

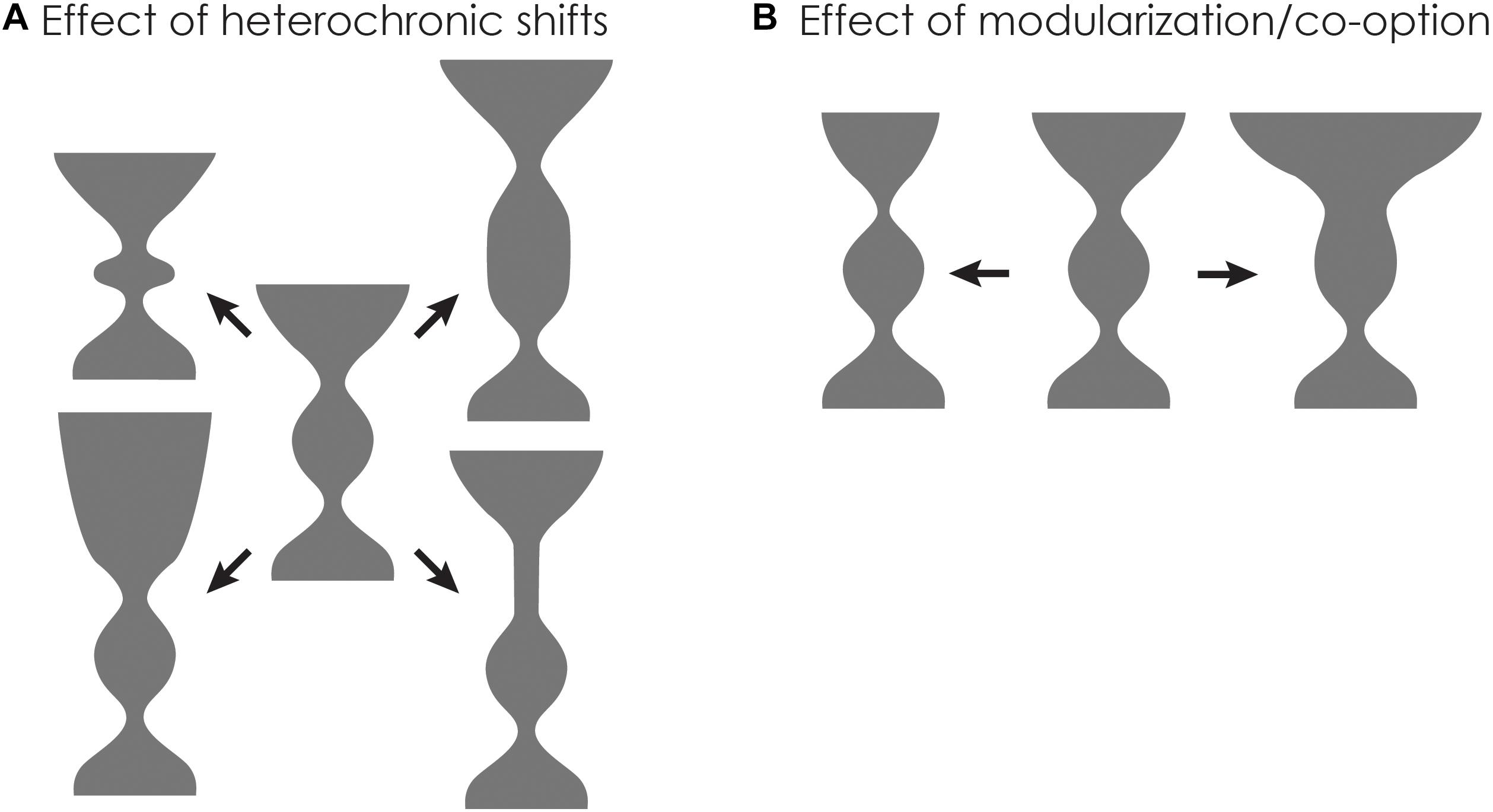

Although the highly pleiotropic developmental physiology might temporarily slow the evolution of metamorphic processes, the same endocrine regulators can also contribute to phenotypic diversification. Two distinct processes can lead to phenotypic diversification of adult morphologies: heterochrony and modularization or co-option of endocrine-dependent processes.

Heterochronic Shifts of Metamorphosis Can Promote Adult Size Diversity

A glance at the organisms living around us highlights the diversity of body sizes across species. Although body sizes and hence the timing of metamorphosis can be impacted by environmental conditions, these differences can be explained by specific-specific differences: No matter how much a fruit fly larva eats, it will never grow as large as a bullfrog. At least some of the diversity of body size can be explained by genetic changes in the timing of metamorphosis (heterochrony).

Heterochronic shifts in the timing of thyroid hormone-mediated metamorphosis can impact adult sizes in Deuterostomes. In amphibians, premature exposure to thyroid hormone can cause the tadpole to initiate metamorphosis at a much smaller size than normally observed (Gudernatsch, 1912; Shi et al., 1996). In contrast, experimental ablation of thyroid glands can cause the tadpole to continue feeding and grow to an enormous size (Allen, 1916). An extreme case of heterochronic shifts has been documented in the direct-developing anuran, Eleutherodactylus coqui (Callery and Elinson, 2000). In this species, thyroid hormone production is initiated during embryogenesis such that the tadpole state is bypassed and a miniature adult frog hatches from the eggs. Shifting the timing of metamorphosis thus has profound impacts on the size of the adult. Similarly, exposure to thyroid hormone or thyroid hormone inhibitors can accelerate or delay, respectively, the timing metamorphosis in echinoderms (Heyland and Hodin, 2004).

In insects, body size can respond readily to artificial selection with corresponding shifts in the timing of metamorphosis (Grunert et al., 2015). In fact, it is the heritable changes in the endocrine response to the environment that often appears to be under selection and to underlie the divergent life history strategies. For instance, insects have evolved distinct responses to starvation depending on the feeding ecology (Callier and Nijhout, 2013; Hatem et al., 2015; Nijhout, 2015; Nagamine et al., 2016; Helm et al., 2017; Xu et al., 2020). In species that feed on ephemeral food sources, starvation often triggers an immediate switch to metamorphic induction by activating ecdysteroid production, ensuring that the larvae regardless of their size will initiate metamorphosis (Mirth et al., 2005; Helm et al., 2017). In species that have reliable food supply, starvation halts ecdysteroid synthesis, leading to a delay in the timing of metamorphosis (Nijhout, 2015; Xu et al., 2020). Moreover, different species have distinct threshold sizes, which is the size checkpoint that determines when a larva can metamorphose (Nijhout, 1975). Threshold size plays a critical role in the final size of the adult and does so by ultimately determining the timing of JH decline (Chafino et al., 2019; He et al., 2020).

In species with larvae that feed and grow, changes in the timing or rate of metamorphic hormone synthesis, release or sensitivity can influence final adult size (Figure 3). Because the endocrine regulators themselves do not change, such changes can occur without disrupting the process of metamorphosis itself. Thus, heterochronic shifts in the timing of metamorphosis, and hence the evolution of final adult size, may occur over just a few generations. We note that heterochronic changes can also occur at the level of individual tissues or behavior. Such heterochronic shifts can occur when traits become modularized and respond to hormones in a trait-specific manner (see next section).

Modularization and Co-option of Hormone Action Promotes Adult Phenotypic Diversification

Although the pleiotropic effects of metamorphic hormones might temporarily constrain evolution of metamorphic events, the sensitivity of target tissues to hormones may not be constrained in the same manner. Adaptive change in the sensitivity of tissues allows individual traits to be regulated independently from the rest of the body. Modularization (Box 1), or the evolution of a unique set of responses to hormones, releases the constraints imposed by the pleiotropic effects of endocrine regulators. Endocrine regulators can also be recruited to regulate new developmental event in a tissue specific manner (a process known as co-option) (True and Carroll, 2002).

The most obvious demonstration of modularization and/or co-option of hormonal pathways in adult development is seen in insect polyphenisms. A recent survey of nymphalid butterflies has demonstrated that 20E titers fluctuate in a thermally sensitive manner regardless of the effect on wing coloration (Bhardwaj et al., 2020). Thus, in polyphenic butterflies, the pigment specification and/or synthesis pathways appear to have co-opted the pre-existing thermally-sensitive ecdysteroid peak of metamorphosis so that the adult wing coloration can be modulated by the larval environment. This example suggests that (1) hormonal levels respond readily to the environment and (2) target tissues can evolve to respond uniquely to the fluctuating hormones.

In other polyphenic traits, hormones that regulate growth of the body can have an exaggerated effect on specific parts of the body. The impressive weapons of rhinoceros beetles grow larger because insulin signaling has an outsized effect on the growth of the head horns (Emlen et al., 2012). Similarly, the disproportionate growth of the horns and mandibles in some beetle species is regulated by localized effects of hormones that arise due to tissue specific sensitivities to metamorphic hormones (Emlen and Nijhout, 1999, 2001; Gotoh et al., 2011, 2014). Thus, when individual tissues acquire the ability to uniquely respond to hormones, phenotypes can overcome hormonal pleiotropy and diversify (Figure 4B). Such changes could arise, for example, by the increased production of the hormone receptor or by more efficient conversion of the prohormone to an active hormone in a particular tissue (Figure 4B).

Finally, we note that modularity facilitates heterochronic shifts of modules. Hormones can act on individual modularized traits and either speed up or slow down development relative to an ancestral trait. Thus, heterochronic changes and modularization can both facilitate phenotypic diversification. For example, changes in thyroid hormone have been suggested to underlie the diversification of barb species in Lake Tana: Experimental alterations of thyroid hormone levels in Lake Tana barbs Labeobarbus intermedius, for example, can accelerate or slow down craniogenesis and produce a bony skull that resembles that of Labeobarbus brevicephalus and Labeobarbus megastoma, respectively (Smirnov et al., 2012; Shkil and Smirnov, 2016). Thyroid hormone does not uniformly impact craniogenesis. Rather, different skull bones have distinct sensitivities to thyroid hormones, allowing thyroid hormone to heterochronically alter the development of skull bones in a modular fashion (Shkil et al., 2012; Shkil and Smirnov, 2016).

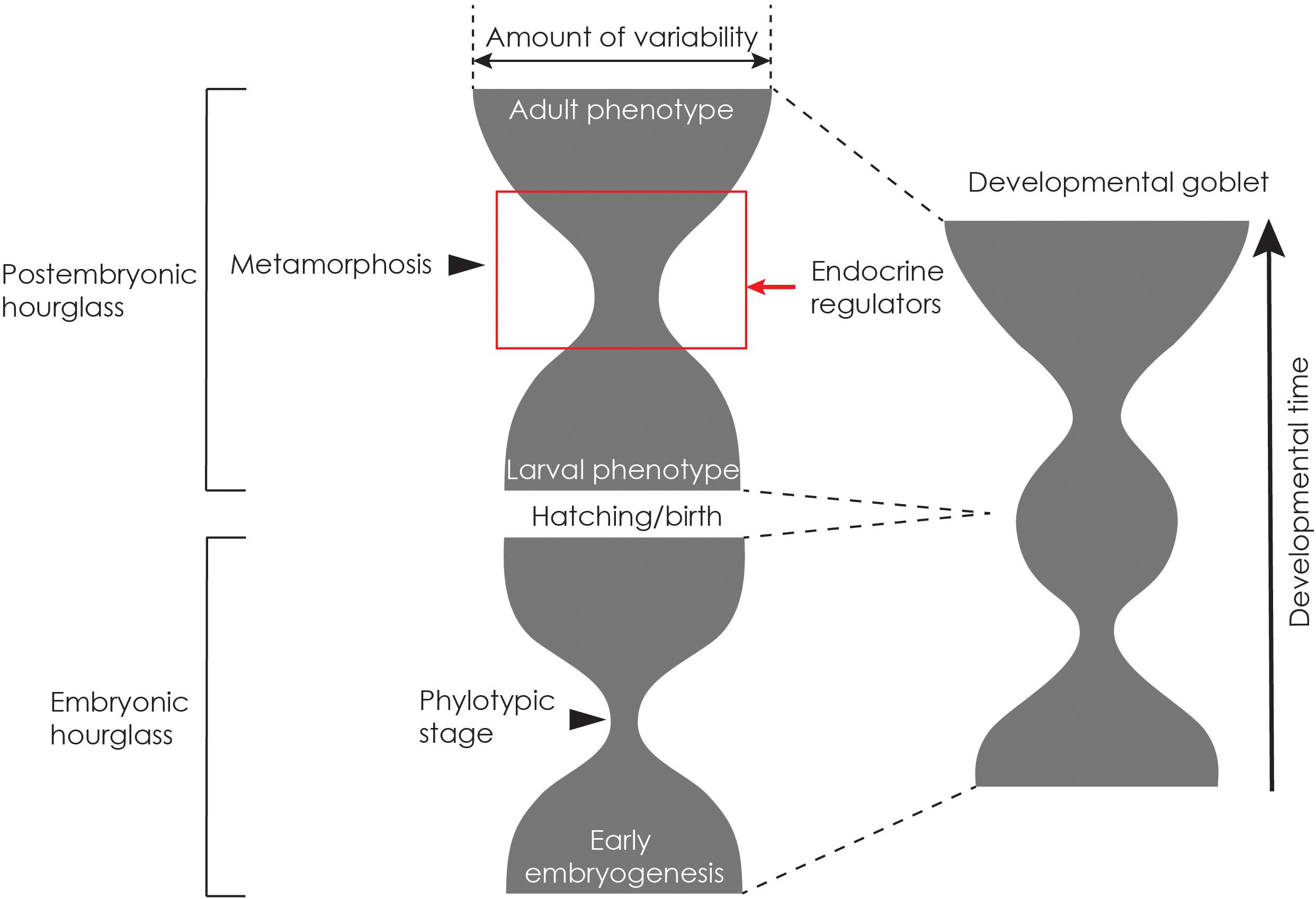

The Developmental Goblet: Metamorphosis as Both a Constrained and Evolvable Stage in Development

In embryos, the phylotypic stage (Box 1) has been proposed to be a time when development is highly constrained and embryos resemble each other across species (Raff, 1996). This understanding led to the conceptualization of a developmental hourglass (Box 1), which has a broad base and broad top that sandwiches a narrow opening, representing the conserved phylotypic stage (Duboule, 1994; Raff, 1996). During the phylotypic stage, complex gene regulatory interactions pattern the major body plans, and any alterations in the interactions are likely to have profound changes in the body plan and the survival of an embryo (Galis and Metz, 2001). Because of these developmental constraints (Smith et al., 1985), gene interactions are predicted to be relatively stable across different species of a phylum, which share similar body plans.

We have discussed how pleiotropy of hormone action can bias development and how release from pleiotropic regulation via modularization and/or co-option of endocrine regulation can allow for diversification of traits. Across species, we propose that the amount of constraint could still be larger during metamorphosis than during the larval or adult stage. We, therefore, suggest that the early portion of metamorphosis represents a second developmentally constrained stage, during which the endocrine mechanisms controlling life history transitions are conserved. Drost et al. (2017) have also hypothesized that metamorphosis may be another constrained stage. Conversely, the larval and late metamorphic stages are less constrained and developmentally uncoupled from each other, allowing divergent stage-specific adaptations (Moran, 1994). If we were to graphically depict the amount of phenotypic and/or developmental variability across post-embryonic development of various metamorphic species within a phylum, we expect an hourglass shape to emerge where the constriction corresponds to metamorphosis, and the broad base and the broad top correspond to the larger phenotypic and/or developmental variability of larvae and adults, respectively (Figure 5). The width of the constriction would then depend upon the degree to which tissues have become modularized or uniquely sensitive to hormones: the more modularized the tissues, the less constricted the hourglass.

Figure 5. The developmental goblet model for metamorphic organisms. The phenotypic diversity of metamorphic animals results from two stacked developmental hourglasses, the developmental goblet, which is composed of an embryonic hourglass and a postembryonic hourglass. The horizontal width of the hourglass represents phenotypic diversity across a taxon. The vertical axis represents developmental time with the top of the goblet representing the adult stage. Early larval ecologies are diverse and are reflected in the diversity of larval phenotypes. During metamorphosis, a small number of developmental hormones constrain development. Subsequently, developmental trajectories diverge to generate various adult morphologies.

The phenotypic diversity of metamorphic animals can then be depicted as two stacked developmental hourglasses, composed of an embryonic and a post-embryonic hourglass (Figure 5). The resulting goblet shape may therefore be more appropriate for metamorphic animals with complex life cycles: the base and the cup representing early embryogenesis and adult development, respectively, and the bulge in the stem of a goblet representing the late embryo/larval stage (Figure 5). We call this the developmental goblet (Box 1).

We suspect that hormonal pleiotropy will constrain the metamorphic stage. However, unlike the embryonic phylotypic stage, the constraints could be more easily overcome by modularization of hormonally regulated traits, and co-option of endocrine regulation can lead to diversification of particular body parts or specific metabolic process. In animals that undergo drastic changes in body plans, metamorphosis is a post-embryonic developmental stage when the expression and/or activity of conserved developmental genes, such as homeobox genes, are modulated by the action of metamorphic hormones and their targets (Gaur et al., 2001; Monier et al., 2005; Mou et al., 2012). In insects undergoing metamorphosis, ecdysteroids activate various signaling networks in a tissue-specific manner (Li and White, 2003). In anurans, Hox genes involved in limb development are activated during limb outgrowth (Lombardo and Slack, 2001), and thyroid hormone-induced metamorphosis in axolotls has been shown to activate the expression of Hox5a in the heart (Gaur et al., 2001). In flatfish, developmental genes are also regulated by thyroid hormone in a tissue-specific manner during metamorphosis (Alves et al., 2016). Thus, hormones coordinate metamorphic events across a variety of tissues, but individual tissues can respond at different times and in distinct ways by activating target developmental genes in a tissue-specific manner. Thus, metamorphosis offers opportunities for innovation and phenotypic diversification.

Finally, we note that the shape of the goblet will likely depend on the taxon. In metamorphic organisms that undergo dramatic tissue reprogramming and remodeling (e.g., insects with complete metamorphosis), the constriction during metamorphosis maybe more pronounced than organisms in which adult organs develop from preexisting larval organs changes (e.g., fishes).

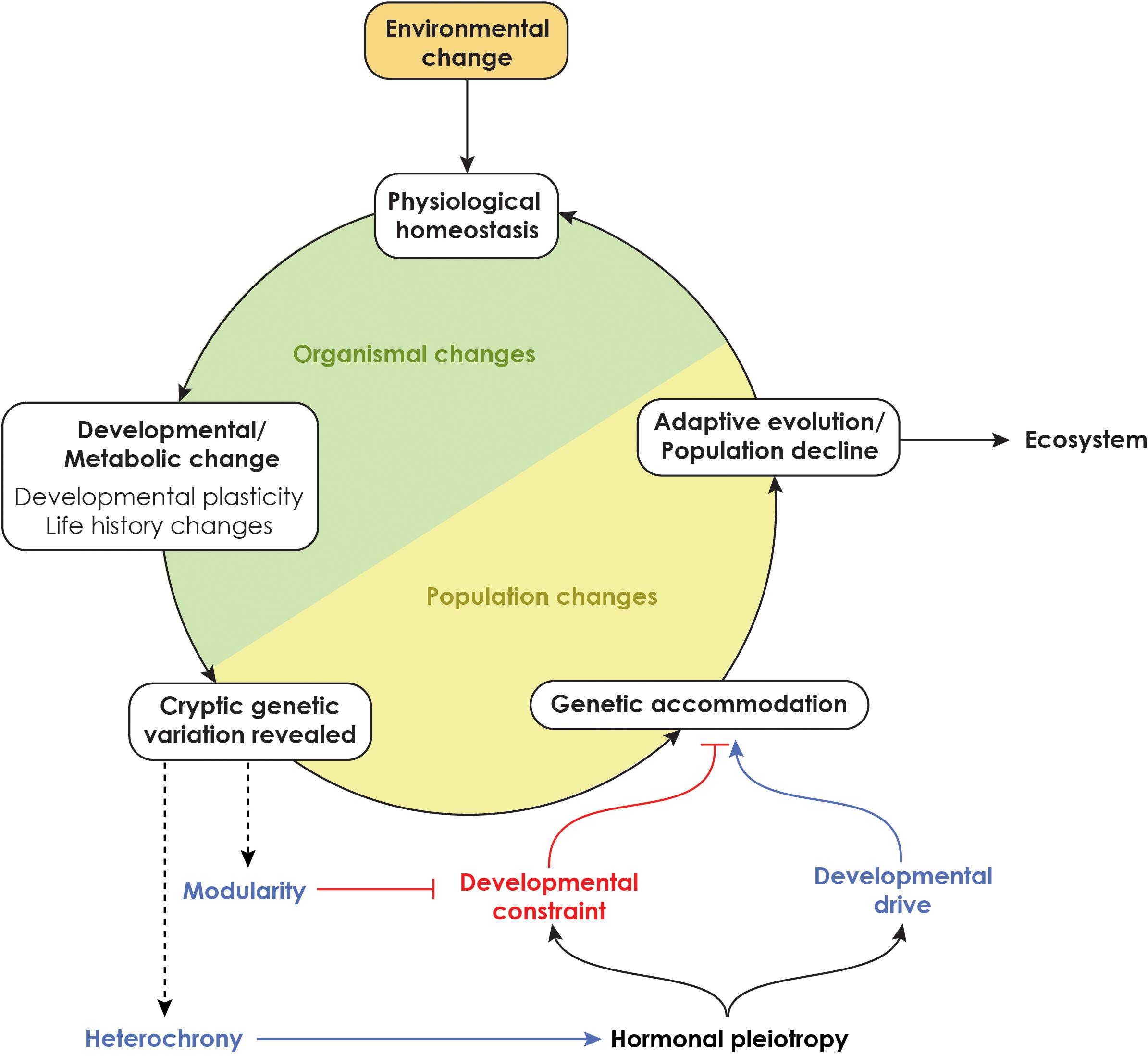

Developmental Homeostasis as a Driver of Evolution by Genetic Accommodation Under a Changing Climate

Phenotypic plasticity is the ability of an organism with the same genotype to give rise to different phenotypes depending on the environment (Box 1). Phenotypic plasticity has been recognized as an important of how populations might respond to climate change (Reed et al., 2011; Merila and Hendry, 2014; Rodrigues and Beldade, 2020). Moreover, phenotypic plasticity has been proposed to facilitate phenotypic evolution by allowing organisms to explore novel morphospace under altered environmental or genetic backgrounds (West-Eberhard, 2003; Nijhout et al., 2021). Specifically, when genetic differences underlie the organisms’ variable phenotypic responses to the novel environment, natural selection can act on the induced phenotypes. The genetic variation underlying the phenotypic variation under the novel environment is called cryptic genetic variation (Box 1), which is normally hidden but is exposed under stressful or novel environments (Gibson and Dworkin, 2004). Selection on these revealed cryptic genetic variants can lead to evolution of novel phenotypes. Genetic accommodation (Box 1) is the name given to such an evolutionary process (West-Eberhard, 2003).

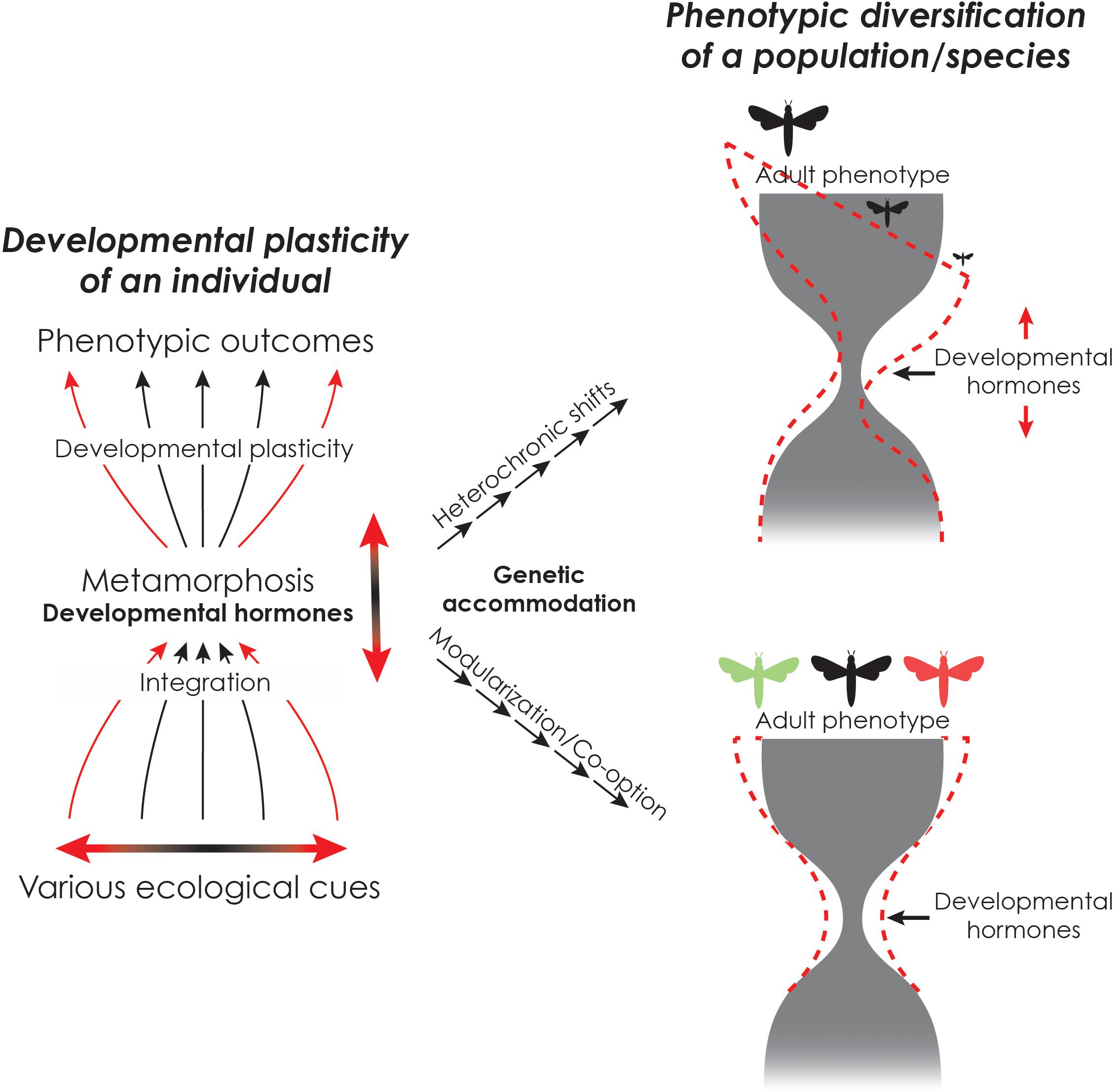

Climate change dependent phenotypic plasticity may lead to adaptive evolution by genetic accommodation (Kelly, 2019). Although several mechanisms have been proposed to explain genetic accommodation, developmental hormones may play a role in this process (Figure 6; Lema and Kitano, 2013; Kulkarni et al., 2017; Lafuente and Beldade, 2019; Levis and Pfennig, 2019; Lema, 2020; Suzuki et al., 2020). Developmental hormones often regulate both trait development and homeostasis, thus serving as the nexus between the environment and development (Dufty et al., 2002; Denver, 2009; Xu et al., 2013; Figure 3). Hormonal changes can manifest as phenotypic differences and the degree to which a developmental hormone impacts the phenotype and facilitate phenotypic evolution can vary according to the cryptic genetic variation that is revealed under stressful conditions (Suzuki and Nijhout, 2006, 2008; Suzuki et al., 2020).

Figure 6. Genetic accommodation via endocrine changes leads to changes in body size and morphology.(Left) Developmental plasticity of an individual. Extreme environmental conditions can lead to changes in the timing of metamorphosis or adult morphogenesis through changes in the timing and amount of endocrine action (solid red lines). (Right) Such changes can be selected for and become genetically accommodated in a population over multiple generations, leading to changes in phenotypic diversity (dotted red lines).

Altered temperature and precipitation patterns due to climate change (Trenberth, 2011; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2014), and resulting changes in food availability, may lead to such stressful environments that disrupt physiological homeostasis and reveal cryptic genetic variation. If the population encounters a directional change in environmental conditions (e.g., warmer and moister) over multiple generations, hormonally mediated traits may evolve by either shifting the timing of life history transitions or by altering the adult phenotypes by co-option or modularization of hormonally mediated traits (Figure 6). For example, in amphibians, desiccation stress and nutritional stress have both been shown to lead to changes in stress hormones, which in turn impacts that timing of metamorphosis and life history transitions (Denver, 1997; Denver et al., 2002; Wada, 2008; Ledon-Rettig et al., 2009; Kulkarni and Buchholz, 2014). In spadefoot toads, aridification has been proposed to have led to the evolution of species with shorter larval periods by adjustments in thyroid hormone titers through genetic accommodation (Gomez-Mestre and Buchholz, 2006; Kulkarni et al., 2017).

In insects, JH levels increase or fail to decline in larvae exposed to stressful environments (Cymborowski et al., 1982; Rauschenbach et al., 1987; Jones et al., 1990; Browder et al., 2001; Suzuki and Nijhout, 2006; Xu et al., 2020), possibly due to the inhibition of the JH degradation enzyme, JHE (Hirashima et al., 1995), and/or changes in JH binding proteins, which may alter the bioavailability of JH (Tauchman et al., 2007). Cryptic genetic variation that confers differential sensitivity to heat or nutritional stress could lead to variation in JH levels that selection could act upon. Similarly, 20E levels has been shown to increase in response to thermal stress in adult Drosophila virilis (Hirashima et al., 2000), and in the common cutworm, Spodoptera litura, mild thermal stress upregulates the expression of EcR during metamorphosis (Shen et al., 2014). Thus, environmental stress can impact both JH and ecdysteroid signaling.

Finally, evolution of hormonal systems could also impact insect diapause through genetic accommodation. Emergence of adults is regulated by hormones, and selection for environmentally sensitive alleles of endocrine regulators has been proposed for the evolution of diapause by genetic accommodation (Schiesari and O’Connor, 2013). Moreover, climate change may impact the timing of entry and exit from diapause (Forrest, 2016). Taken together, genetic accommodation of hormonal regulation may play a role in the evolution of the timing of metamorphosis and life history transitions.

Genetic accommodation mediated by physiological homeostasis can change the shape of the developmental goblet in two ways: Either the height can change, or the width of the upper constriction and shape of the “cup” might change (Figure 7). For example, parts of the hourglass may lengthen due to changes in diapause, dormancy or the timing of metamorphosis, each of which would increase the height of the hourglass (Figure 7A). Alternatively, the width and shape of the upper cup can change by increased modularity and release from hormonal pleiotropy (Figure 7B). Of course, different species respond in disparate ways to varying environmental conditions. Thus, the overall effect of genetic accommodation on a group of species will be the total of such changes.

Figure 7. Changes in developmental endocrinology in response to climate change can lead to changes in body size and metabolism/morphology. (A) Potential effects of heterochronic shifts on the shape of the developmental goblet. Changes in endocrine system can lead to alteration in duration of the larval or metamorphic stages. (B) Potential effects of modularization/co-option on the shape of the developmental goblet. Changes in endocrine system can lead to alteration in phenotypic diversity of the adult stages.

Climate change will impact the length of the growing season, the timing of metamorphosis and the size of adult organisms which can impact fitness (Honěk, 1993; Blanckenhorn, 2000; Blanckenhorn and Demont, 2004; Daufresne et al., 2009; Sheridan and Bickford, 2011). Although these changes certainly have many proximate causes (Atkinson, 1994; Atkinson and Sibly, 1997; Verberk et al., 2021), how a species adapts in response to climate change may also depend on the developmental system as well as the amount and nature of cryptic genetic variation: stabilization of the newly induced phenotypes can lead to genetic assimilation (or fixation) of the novel phenotypes (Box 1); selection on the novel phenotypes could lead to increased phenotypic plasticity; or selection in the altered environment could lead to compensatory genetic changes that restores the original phenotype (i.e., genetic compensation) (Grether, 2005). Because so many traits are regulated by hormones, changes in hormonal response requires uncoupling of tissues and subsequent evolution of appropriate tissues specific adaptations—modularization of adaptation. Whether such changes can happen fast enough to keep up with the rapid pace of climate change remains unclear. Therefore, metamorphic organisms may not be able to evolve in all directions depicted in Figure 7. Instead, certain directions of change may occur more rapidly than others.

Conclusion

Climate change in the Anthropocene has dramatically accelerated extinction rates (Waters et al., 2016). However, how evo-devo intersects with climate change remains poorly studied (Campbell et al., 2017; Gilbert, 2021). Recent studies have begun to identify alleles that are involved in organismal response to climate change (Franks and Hoffmann, 2012; Merila and Hendry, 2014), but the mechanistic basis of evolution of organisms in response to climate change is still lacking (Chmura et al., 2019). In metamorphic organism, hormones play critical roles in life history transitions. Because of the multitude of roles they play, hormones can bias the way organisms develop and evolve, leading to changes in the shapes of the developmental goblet. We propose that developmental homeostasis may be a contributor for adaptive evolution especially in a changing climate (Figure 8). As organisms face climate change, changes in homeostatic mechanisms may allow rapid adaptive responses in metabolism that are followed by phenological and morphological changes that alter the shape of the developmental goblet. In particular, physiological homeostasis can allow the expression of hidden genetic variation that can promote adaptive evolution. The amount of hidden genetic variation present in a population for such adaptive changes may then be a determinant of whether a population thrives or collapses.

Figure 8. Impact of climate change on developmental hormones and their ultimate impacts on populations and the ecosystem. Climate change can impact developmental physiology of organisms that can influence their development and life history. Cryptic genetic variation that is revealed as a consequence of climate change can fuel genetic accommodation of traits. The degree to which members of a population can adjust their development and physiology determines whether a population thrives or declines.

Author Contributions

YS and LT wrote sections of the manuscript. Both authors contributed to the manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Science Foundation grant IOS-2002354 and funding from Wellesley College. The publication fees for this article were supported by the Wellesley College Library and Technology Services Open Access Fund.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Drs. Julia Bowsher, Marianne Moore, and Nick Rodenhouse, and members of the Suzuki lab for their constructive feedback on earlier drafts of this work. We would also like to thank the reviewers of this work who have provided helpful and constructive criticisms that helped to improve this work.

References

Agrawal, N., Delanoue, R., Mauri, A., Basco, D., Pasco, M., Thorens, B., et al. (2016). The Drosophila TNF eiger is an adipokine that acts on insulin-producing cells to mediate nutrient response. Cell Metab. 23, 675–684. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.03.003

Alinezhad, S., Abdollahpour, H., Jafari, N., and Falahatkar, B. (2020). Effects of thyroxine immersion on Sterlet sturgeon (Acipenser ruthenus) embryos and larvae: variations in thyroid hormone levels during development. Aquaculture 519:734745. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2019.734745

Allen, B. M. (1916). The results of the extirpation of the anterior lobe of the hypophysis and of the thyroid of Rana pipiens larvae. Science 44, 755–758. doi: 10.1126/science.44.1143.755

Álvarez, D., and Nicieza, A. G. (2002). Effects of temperature and food quality on anuran larval growth and metamorphosis. Funct. Ecol. 16, 640–648. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2435.2002.00658.x

Alves, R. N., Gomes, A. S., Stueber, K., Tine, M., Thorne, M. A., Smaradottir, H., et al. (2016). The transcriptome of metamorphosing flatfish. BMC Genomics 17:413. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-2699-x

Arbeitman, M. N., Furlong, E. E., Imam, F., Johnson, E., Null, B. H., Baker, B. S., et al. (2002). Gene expression during the life cycle of Drosophila melanogaster. Science 297, 2270–2275. doi: 10.1126/science.1072152

Arthur, W. (2001). Developmental drive: an important determinant of the direction of phenotypic evolution. Evol. Dev. 3, 271–278. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-142x.2001.003004271.x

Atkinson, D. (1994). Temperature and organism size – a biological law for ectotherms? Adv. Ecol. Res. 25, 1–58. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2504(08)60212-3

Atkinson, D., and Sibly, R. M. (1997). Why are organisms usually bigger in colder environments? Making sense of a life history puzzle. Trends Ecol. Evol. 12, 235–239. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(97)01058-6

Ayson, F. G., and Lam, T. J. (1993). Thyroxine injection of female rabbitfish (Siganus guttatus) broodstock: changes in thyroid hormone levels in plasma, eggs, and yolk-sac larvae, and its effect on larval growth and survival. Aquaculture 109, 83–93. doi: 10.1016/0044-8486(93)90488-K

Baker, M. E. (2010). Evolution of 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-type 1 and 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-type 3. FEBS Lett. 584, 2279–2284. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.03.036

Belles, X. (2019). The innovation of the final moult and the origin of insect metamorphosis. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 374:20180415. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2018.0415

Belles, X., and Santos, C. G. (2014). The MEKRE93 (Methoprene tolerant-Kruppel homolog 1-E93) pathway in the regulation of insect metamorphosis, and the homology of the pupal stage. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 52, 60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2014.06.009

Bhardwaj, S., Jolander, L. S., Wenk, M. R., Oliver, J. C., Nijhout, H. F., and Monteiro, A. (2020). Origin of the mechanism of phenotypic plasticity in satyrid butterfly eyespots. eLife 9:e49544. doi: 10.7554/eLife.49544

Bilen, J., Atallah, J., Azanchi, R., Levine, J. D., and Riddiford, L. M. (2013). Regulation of onset of female mating and sex pheromone production by juvenile hormone in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 18321–18326. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1318119110

Bishop, C. D., Erezyilmaz, D. F., Flatt, T., Georgiou, C. D., Hadfield, M. G., Heyland, A., et al. (2006). What is metamorphosis? Integr. Comp. Biol. 46, 655–661. doi: 10.1093/icb/icl004

Blanckenhorn, W. U. (2000). The evolution of body size: What keeps organisms small? Q. Rev. Biol. 75, 385–407. doi: 10.1086/393620

Blanckenhorn, W. U., and Demont, M. (2004). Bergmann and converse bergmann latitudinal clines in arthropods: Two ends of a continuum? Integr. Comp. Biol. 44, 413–424. doi: 10.1093/icb/44.6.413

Bonett, R. M., Hoopfer, E. D., and Denver, R. J. (2010). Molecular mechanisms of corticosteroid synergy with thyroid hormone during tadpole metamorphosis. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 168, 209–219. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2010.03.014

Boorse, G. C., and Denver, R. J. (2003). Endocrine mechanisms underlying plasticity in metamorphic timing in spadefoot toads. Integr. Comp. Biol. 43, 646–657. doi: 10.1093/icb/43.5.646

Brogiolo, W., Stocker, H., Ikeya, T., Rintelen, F., Fernandez, R., and Hafen, E. (2001). An evolutionarily conserved function of the Drosophila insulin receptor and insulin-like peptides in growth control. Curr. Biol. 11, 213–221. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00068-9

Browder, M. H., D’Amico, L. J., and Nijhout, H. F. (2001). The role of low levels of juvenile hormone esterase in the metamorphosis of Manduca sexta. J. Insect. Sci. 1:11. doi: 10.1673/031.001.1101

Brown, D. D., and Cai, L. (2007). Amphibian metamorphosis. Dev. Biol. 306, 20–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.03.021

Cai, L., and Brown, D. D. (2004). Expression of type II iodothyronine deiodinase marks the time that a tissue responds to thyroid hormone-induced metamorphosis in Xenopus laevis. Dev. Biol. 266, 87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.10.005

Caldwell, P. E., Walkiewicz, M., and Stern, M. (2005). Ras activity in the Drosophila prothoracic gland regulates body size and developmental rate via ecdysone release. Curr. Biol. 15, 1785–1795. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.09.011

Callery, E. M., and Elinson, R. P. (2000). Thyroid hormone-dependent metamorphosis in a direct developing frog. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 2615–2620. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050501097

Callier, V., and Nijhout, H. F. (2013). Body size determination in insects: a review and synthesis of size- and brain-dependent and independent mechanisms. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 88, 944–954. doi: 10.1111/brv.12033

Cambron, L. D., Yocum, G. D., Yeater, K. M., and Greenlee, K. J. (2021). Overwintering conditions impact insulin pathway gene expression in diapausing Megachile rotundata. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 256:110937. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2021.110937

Campbell, C. S., Adams, C. E., Bean, C. W., and Parsons, K. J. (2017). Conservation evo-devo: preserving biodiversity by understanding its origins. Trends Ecol. Evol. 32, 746–759. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2017.07.002

Campinho, M. A., Silva, N., Roman-Padilla, J., Ponce, M., Manchado, M., and Power, D. M. (2015). Flatfish metamorphosis: A hypothalamic independent process? Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 404, 16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2014.12.025

Chafino, S., Lopez-Escardo, D., Benelli, G., Kovac, H., Casacuberta, E., Franch-Marro, X., et al. (2018). Differential expression of the adult specifier E93 in the strepsipteran Xenos vesparum Rossi suggests a role in female neoteny. Sci. Rep. 8:14176. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-32611-y

Chafino, S., Urena, E., Casanova, J., Casacuberta, E., Franch-Marro, X., and Martin, D. (2019). Upregulation of E93 gene expression acts as the trigger for metamorphosis independently of the threshold size in the beetle Tribolium castaneum. Cell Rep. 27, 1039–1049.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.03.094

Champlin, D. T., and Truman, J. W. (1998a). Ecdysteroid control of cell proliferation during optic lobe neurogenesis in the moth Manduca sexta. Development 125, 269–277. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.2.269

Champlin, D. T., and Truman, J. W. (1998b). Ecdysteroids govern two phases of eye development during metamorphosis of the moth, Manduca sexta. Development 125, 2009–2018. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.11.2009

Cherbas, L., Hu, X., Zhimulev, I., Belyaeva, E., and Cherbas, P. (2003). EcR isoforms in Drosophila: testing tissue-specific requirements by targeted blockade and rescue. Development 130, 271–284. doi: 10.1242/dev.00205

Chesebro, J., Hrycaj, S., Mahfooz, N., and Popadic, A. (2009). Diverging functions of Scr between embryonic and post-embryonic development in a hemimetabolous insect, Oncopeltus fasciatus. Dev. Biol. 329, 142–151. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.01.032

Chino, Y., Saito, M., Yamasu, K., Suyemitsu, T., and Ishihara, K. (1994). Formation of the adult rudiment of sea urchins is influenced by thyroid hormones. Dev. Biol. 161, 1–11. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1001

Chippendale, G. M., and Yin, C. M. (1975). Reappraisal of proctodone involvement in the hormonal regulation of larval diapause. Biol. Bull. 149, 151–164. doi: 10.2307/1540486

Chmura, H. E., Kharouba, H. M., Ashander, J., Ehlman, S. M., Rivest, E. B., and Yang, L. H. (2019). The mechanisms of phenology: the patterns and processes of phenological shifts. Ecol. Monogr. 89:e01337. doi: 10.1002/ecm.1337

Chou, J., Ferris, A. C., Chen, T., Seok, R., Yoon, D., and Suzuki, Y. (2019). Roles of Polycomb group proteins Enhancer of zeste (E(z)) and Polycomb (Pc) during metamorphosis and larval leg regeneration in the flour beetle Tribolium castaneum. Dev. Biol. 450, 34–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2019.03.002

Collet, J., and Fellous, S. (2019). Do traits separated by metamorphosis evolve independently? Concepts and methods. Proc. R. Soc. B 286:20190445. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2019.0445

Colombani, J., Andersen, D. S., and Leopold, P. (2012). Secreted peptide Dilp8 coordinates Drosophila tissue growth with developmental timing. Science 336, 582–585. doi: 10.1126/science.1216689

Colombani, J., Bianchini, L., Layalle, S., Pondeville, E., Dauphin-Villemant, C., Antoniewski, C., et al. (2005). Antagonistic actions of ecdysone and insulins determine final size in Drosophila. Science 310, 667–670. doi: 10.1126/science.1119432

Colombani, J., Raisin, S., Pantalacci, S., Radimerski, T., Montagne, J., and Leopold, P. (2003). A nutrient sensor mechanism controls Drosophila growth. Cell 114, 739–749. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00713-X

Cymborowski, B., Bogus, M., Beckage, N. E., Williams, C. M., and Riddiford, L. M. (1982). Juvenile hormone titres and metabolism during starvation-induced supernumerary larval moulting of the tobacco hornworm, Manduca sexta L. J. Insect Physiol. 28, 129–135. doi: 10.1016/0022-1910(82)90120-2

Daufresne, M., Lengfellner, K., and Sommer, U. (2009). Global warming benefits the small in aquatic ecosystems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 12788–12793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902080106

Davey, J. C., Becker, K. B., Schneider, M. J., St Germain, D. L., and Galton, V. A. (1995). Cloning of a cDNA for the type II iodothyronine deiodinase. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 26786–26789. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.26786

Davidowitz, G., D’Amico, L. J., and Nijhout, H. F. (2003). Critical weight in the development of insect body size. Evol. Dev. 5, 188–197. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-142X.2003.03026.x

Davidowitz, G., D’Amico, L. J., and Nijhout, H. F. (2004). The effects of environmental variation on a mechanism that controls insect body size. Evol. Ecol. Res. 6, 49–62.

Davis, M. B., Carney, G. E., Robertson, A. E., and Bender, M. (2005). Phenotypic analysis of EcR-A mutants suggests that EcR isoforms have unique functions during Drosophila development. Dev. Biol. 282, 385–396. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.03.019

de Jesus, E. G., Inui, Y., and Hirano, T. (1990). Cortisol enhances the stimulating action of thyroid hormones on dorsal fin-ray resorption of flounder larvae in vitro. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 79, 167–173. doi: 10.1016/0016-6480(90)90101-Q

de Jesus, E. G., Toledo, J. D., and Simpas, M. S. (1998). Thyroid hormones promote early metamorphosis in grouper (Epinephelus coioides) larvae. Gen. Comp. Endocr. 112, 10–16. doi: 10.1006/gcen.1998.7103

Deal, C. K., and Volkoff, H. (2020). The role of the thyroid axis in fish. Front. Endocrinol. 11:596585. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2020.596585

Denver, R. J. (1997). Environmental stress as a developmental cue: corticotropin-releasing hormone is a proximate mediator of adaptive phenotypic plasticity in amphibian metamorphosis. Horm. Behav. 31, 169–179. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1997.1383

Denver, R. J. (1998). Hormonal correlates of environmentally induced metamorphosis in the Western spadefoot toad, Scaphiopus hammondii. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 110, 326–336. doi: 10.1006/gcen.1998.7082

Denver, R. J. (1999). Evolution of the corticotropin-releasing hormone signaling system and its role in stress-induced phenotypic plasticity. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 897, 46–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07877.x

Denver, R. J. (2009). Stress hormones mediate environment-genotype interactions during amphibian development. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 164, 20–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2009.04.016

Denver, R. J. (2013). “Chapter seven – neuroendocrinology of amphibian metamorphosis,” in Current Topics in Developmental Biology, ed. S. Yun-Bo (New York, NY: Academic Press), 195–227. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385979-2.00007-1

Denver, R. J. (2021). Stress hormones mediate developmental plasticity in vertebrates with complex life cycles. Neurobiol. Stress 14:100301. doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2021.100301

Denver, R. J., Glennemeier, K. A., and Boorse, G. C. (2002). “28 - Endocrinology of complex life cycles: amphibians,” in Hormones, Brain and Behavior, eds D. W. Pfaff, A. P. Arnold, S. E. Fahrbach, A. M. Etgen, and R. T. Rubin (San Diego, CA: Academic Press), 469. doi: 10.1016/B978-012532104-4/50030-5

Denver, R. J., Mirhadi, N., and Phillips, M. (1998). Adaptive plasticity in amphibian metamorphosis: response of Scaphiopus hammondii tadpoles to habitat desiccation. Ecology 79, 1859–1872. doi: 10.2307/176694

Drost, H. G., Janitza, P., Grosse, I., and Quint, M. (2017). Cross-kingdom comparison of the developmental hourglass. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 45, 69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2017.03.003

Duboule, D. (1994). Temporal colinearity and the phylotypic progression: a basis for the stability of a vertebrate Bauplan and the evolution of morphologies through heterochrony. Development 1994 (Supplement) 135–142. doi: 10.1242/dev.1994.Supplement.135

Dufty, A. M., Clobert, J., and Møller, A. P. (2002). Hormones, developmental plasticity and adaptation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 17, 190–196. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(02)02498-9

Emlen, D. J. (1997). Alternative reproductive tactics and male-dimorphism in the horned beetle Onthophagus acuminatus (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae). Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 41, 335–341. doi: 10.1007/s002650050393

Emlen, D. J., and Nijhout, H. F. (1999). Hormonal control of male horn length dimorphism in the dung beetle Onthophagus taurus (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae). J. Insect Physiol. 45, 45–53. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1910(98)00096-1

Emlen, D. J., and Nijhout, H. F. (2001). Hormonal control of male horn length dimorphism in Onthophagus taurus (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae): a second critical period of sensitivity to juvenile hormone. J. Insect Physiol. 47, 1045–1054. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1910(01)00084-1

Emlen, D. J., Warren, I. A., Johns, A., Dworkin, I., and Lavine, L. C. (2012). A mechanism of extreme growth and reliable signaling in sexually selected ornaments and weapons. Science 337, 860–864. doi: 10.1126/science.1224286

Flatt, T., Tu, M. P., and Tatar, M. (2005). Hormonal pleiotropy and the juvenile hormone regulation of Drosophila development and life history. BioEssays 27, 999–1010. doi: 10.1002/bies.20290

Forrest, J. R. (2016). Complex responses of insect phenology to climate change. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 17, 49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cois.2016.07.002

Franks, S. J., and Hoffmann, A. A. (2012). Genetics of climate change adaptation. Annu. Rev. Genet. 46, 185–208. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110711-155511

Freitas, J. S., Kupsco, A., Diamante, G., Felicio, A. A., Almeida, E. A., and Schlenk, D. (2016). Influence of temperature on the thyroidogenic effects of diuron and its metabolite 3,4-DCA in tadpoles of the American bullfrog (Lithobates catesbeianus). Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 13095–13104. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b04076

Freitas, M. B., Brown, C. T., and Karasov, W. H. (2017). Warmer temperature modifies effects of polybrominated diphenyl ethers on hormone profiles in leopard frog tadpoles (Lithobates pipiens). Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 36, 120–127. doi: 10.1002/etc.3506

Frieden, E., and Naile, B. (1955). Biochemistry of Amphibian Metamorphosis: I. Enhancement of Induced Metamorphosis by Gluco-Corticoids. Science 121, 37–39. doi: 10.1126/science.121.3132.37

Fuchs, B., Wang, W., Graspeuntner, S., Li, Y., Insua, S., Herbst, E. M., et al. (2014). Regulation of polyp-to-jellyfish transition in Aurelia aurita. Curr. Biol. 24, 263–273. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.12.003

Fukazawa, H., Hirai, H., Hori, H., Roberts, R. D., Nukaya, H., Ishida, H., et al. (2001). Induction of abalone larval metamorphosis by thyroid hormones. Fish Sci. 67, 985–988. doi: 10.1046/j.1444-2906.2001.00351.x

Galis, F., and Metz, J. A. (2001). Testing the vulnerability of the phylotypic stage: on modularity and evolutionary conservation. J. Exp. Zool. 291, 195–204. doi: 10.1002/jez.1069

Gaur, A., Zajdel, R. W., Bhatia, R., Isitmangil, G., Denz, C. R., Robertson, D. R., et al. (2001). Expression of HoxA5 in the heart is upregulated during thyroxin-induced metamorphosis of the Mexican axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum). Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 1, 225–235. doi: 10.1385/CT:1:3:225

Geminard, C., Rulifson, E. J., and Leopold, P. (2009). Remote control of insulin secretion by fat cells in Drosophila. Cell Metab. 10, 199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.08.002

Gibson, G., and Dworkin, I. (2004). Uncovering cryptic genetic variation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 5, 681–690. doi: 10.1038/nrg1426

Gilbert, S. F. (2021). Evolutionary developmental biology and sustainability: a biology of resilience. Evol. Dev. 23:e12366. doi: 10.1111/ede.12366

Gomez-Mestre, I., and Buchholz, D. R. (2006). Developmental plasticity mirrors differences among taxa in spadefoot toads linking plasticity and diversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 19021–19026. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603562103

Goodman, W. G., and Granger, N. A. (2005). “The juvenile hormones,” in Comprehensive Molecular Insect Science, eds I. Lawrence, L. I. Gilbert, K. Iatrou, and S. S. Gill (Amsterdam: Elsevier), 319–408. doi: 10.1016/B0-44-451924-6/00039-9

Gotoh, H., Cornette, R., Koshikawa, S., Okada, Y., Lavine, L. C., Emlen, D. J., et al. (2011). Juvenile hormone regulates extreme mandible growth in male stag beetles. PLoS One 6:e21139. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021139

Gotoh, H., Miyakawa, H., Ishikawa, A., Ishikawa, Y., Sugime, Y., Emlen, D. J., et al. (2014). Developmental link between sex and nutrition; doublesex regulates sex-specific mandible growth via juvenile hormone signaling in stag beetles. PLoS Genet. 10:e1004098. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004098

Gray, K. M., and Janssens, P. A. (1990). Gonadal hormones inhibit the induction of metamorphosis by thyroid hormones in Xenopus laevis tadpoles in vivo, but not in vitro. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 77, 202–211. doi: 10.1016/0016-6480(90)90304-5

Green, D. A. II, and Kronforst, M. R. (2019). Monarch butterflies use an environmentally sensitive, internal timer to control overwintering dynamics. Mol. Ecol. 28, 3642–3655. doi: 10.1111/mec.15178

Greene, E. (1989). A diet-induced developmental polymorphism in a caterpillar. Science 243, 643–646. doi: 10.1126/science.243.4891.643

Grether, G. F. (2005). Environmental change, phenotypic plasticity, and genetic compensation. Am. Nat. 166, E115–E123. doi: 10.1086/432023

Grunert, L. W., Clarke, J. W., Ahuja, C., Eswaran, H., and Nijhout, H. F. (2015). A quantitative analysis of growth and size regulation in Manduca sexta: the physiological basis of variation in size and age at metamorphosis. PLoS One 10:e0127988. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127988

Gudernatsch, J. F. (1912). Feeding experiments on tadpoles. Wilhelm Roux’ Arch. Entwicklungsmech. Org. 35, 457–483. doi: 10.1007/BF02277051

Hatem, N. E., Wang, Z., Nave, K. B., Koyama, T., and Suzuki, Y. (2015). The role of juvenile hormone and insulin/TOR signaling in the growth of Manduca sexta. BMC Biol. 13:44. doi: 10.1186/s12915-015-0155-z

Hayes, T. B. (1997). Hormonal mechanisms as potential constraints on evolution: examples from the Anura. Am. Zool. 37, 482–490. doi: 10.1093/icb/37.6.482

He, L. L., Shin, S. H., Wang, Z., Yuan, I., Weschler, R., Chiou, A., et al. (2020). Mechanism of threshold size assessment: metamorphosis is triggered by the TGF-beta/Activin ligand Myoglianin. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 126:103452. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2020.103452

Hegland, S. J., Nielsen, A., Lázaro, A., Bjerknes, A.-L., and Totland, Ø. (2009). How does climate warming affect plant-pollinator interactions? Ecol. Lett. 12, 184–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2008.01269.x

Helbing, C. C., Werry, K., Crump, D., Domanski, D., Veldhoen, N., and Bailey, C. M. (2003). Expression profiles of novel thyroid hormone-responsive genes and proteins in the tail of Xenopus laevis tadpoles undergoing precocious metamorphosis. Mol. Endocrinol. 17, 1395–1409. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0274

Helm, B. R., Rinehart, J. P., Yocum, G. D., Greenlee, K. J., and Bowsher, J. H. (2017). Metamorphosis is induced by food absence rather than a critical weight in the solitary bee, Osmia lignaria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 10924–10929. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1703008114

Herboso, L., Oliveira, M. M., Talamillo, A., Pérez, C., González, M., Martín, D., et al. (2015). Ecdysone promotes growth of imaginal discs through the regulation of Thor in D. melanogaster. Sci. Rep. 5:12383. doi: 10.1038/srep12383

Heyland, A., and Hodin, J. (2004). Heterochronic developmental shift caused by thyroid hormone in larval sand dollars and its implications for phenotypic plasticity and the evolution of nonfeeding development. Evolution 58, 524–538. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2004.tb01676.x

Heyland, A., Price, D. A., Bodnarova-Buganova, M., and Moroz, L. L. (2006). Thyroid hormone metabolism and peroxidase function in two non-chordate animals. J. Exp. Zool. B Mol. Dev. Evol. 306, 551–566. doi: 10.1002/jez.b.21113

Hirashima, A., Rauschenbach, I., and Sukhanova, M. (2000). Ecdysteroids in stress responsive and nonresponsive Drosophila virilis lines under stress conditions. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 64, 2657–2662. doi: 10.1271/bbb.64.2657