- School of Life Sciences, University of Technology Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

In many lizards, a mother’s choice of nest site can influence the thermal and hydric regimes experienced by developing embryos, which in turn can influence key traits putatively linked to fitness, such as body size, learning ability, and locomotor performance. Future increases in nest temperatures predicted under climate warming could potentially influence hatchling traits in many reptiles. In this study, we investigated whether future nest temperatures affected the thermal preferences of hatchling velvet geckos, Amalosia lesueurii. We incubated eggs under two fluctuating temperature treatments; the warm treatment mimicked temperatures of currently used communal nests (mean = 24.3°C, range 18.4–31.1°C), while the hot treatment (mean = 28.9°C, range 20.7–38.1°C) mimicked potential temperatures likely to occur during hot summers. We placed hatchlings inside a thermal gradient and measured their preferred body temperatures (Tbs) after they had access to food, and after they had fasted for 5 days. We found that hatchling feeding status significantly affected their preferred Tbs. Hatchlings maintained higher Tbs after feeding (mean = 30.6°C, interquartile range = 29.6–32.0°C) than when they had fasted for 5 d (mean = 25.8°C, interquartile range = 24.7–26.9°C). Surprisingly, we found that incubation temperatures did not influence the thermal preferences of hatchling velvet geckos. Hence, predicting how future changes in nest temperatures will affect reptiles will require a better understanding of how incubation and post-hatchling environments shape hatchling phenotypes.

Introduction

Developmental plasticity, the changes in the phenotype induced by the environment experienced by the developing embryo, is an important source of variation for many organismal traits that can influence individual fitness (West-Eberhardt, 2003). In most species of oviparous reptiles, females abandon their eggs after laying them in nests (Reynolds et al., 2002). In the absence of parental care, the thermal and hydric conditions inside reptile nests can vary markedly throughout the incubation period. For example, nest temperatures often fluctuate widely on a daily basis (Shine and Harlow, 1996; Andrews and Warner, 2002), and can vary depending on local weather conditions (Shine, 2004). In the last few decades, a large body of experimental research has demonstrated that incubation temperatures can influence a multitude of offspring traits, including sex, morphology, behavior, performance, and cognitive abilities (Deeming and Ferguson, 1991; Deeming, 2004; Noble et al., 2018; While et al., 2018). Some of these developmental effects can be long lasting, and can influence the growth and survival of offspring (Qualls and Andrews, 1999; Andrews et al., 2000; Dayananda et al., 2016) and may influence lifetime reproductive success (Warner and Shine, 2008). Thus, an understanding of thermal developmental plasticity can provide insights into how reptiles may cope with changing environments (Mitchell et al., 2008; Angilletta, 2009; Carlo et al., 2018).

Most research on thermal developmental plasticity has focused on how incubation temperatures affect morphological traits, physiology, sex ratios and incubation duration (While et al., 2018). By contrast, few studies have investigated whether incubation temperatures can also influence the thermal preferences or thermal tolerances of hatchlings (Lang, 1987; Blumberg et al., 2002; Du et al., 2010; Dayananda et al., 2017; Abayarathna et al., 2019; Refsnider et al., 2019). Most lizards maintain their body temperature (hereafter, Tb) within a preferred range by carefully selecting suitable microhabitats, altering their behavior, or by adjusting their posture, shape, or color (Huey, 1982). In turn, selected Tbs influence the physiology, behavior, performance, activity budgets, and growth of individuals, which can influence their survival and reproduction (Huey, 1982; Angilletta, 2009). Thus, incubation-induced plasticity in preferred body temperatures (Tpref) may have important fitness consequences for hatchling lizards. More broadly, an understanding of how incubation temperatures influence the Tpref of lizards is important for predicting how species may fare under future climates (Huey et al., 2012).

Experimental studies on lizards have found that incubation temperatures may affect the thermoregulatory behavior of hatchlings of some species, but not others (Du et al., 2010; Refsnider et al., 2019). For example, incubation temperatures did not affect the selected Tbs of hatchling veiled chameleons Chamaeleo calyptratus (Andrews, 2008), three lined skinks Bassiana duperreyi (Du et al., 2010), or Cuban rock iguanas Cyclura nubila (Alberts et al., 1997). By contrast, other studies reported the opposite effect. For example, in the Madagascar ground gecko, Paroedura pictus, hatchlings from hot incubation temperatures had higher dorsal temperatures prior to crossing between the cold and hot sides of a thermal shuttle apparatus (Blumberg et al., 2002). In Sceloporus virgatus, hatchlings from cold temperature incubation (15–25°C) selected higher Tbs, and maintained Tbs more precisely than hatchlings from hot temperature (20–30°C) incubation (Qualls and Andrews, 1999). In a study on Jacky dragons (Amphibolurus muricatus) using constant temperature incubation, hatchlings from the 28.1°C treatment had lower Tbs after 2 h in a thermal gradient than hatchlings from 25 or 32°C treatments (Esquerre et al., 2014). Despite evidence that incubation temperatures can affect the Tpref of hatchlings, it is unclear whether such incubation induced shifts are ecologically relevant, particularly if the effects are short lived or are masked by interactions with the post-hatching environment (Andrews et al., 2000; Buckley et al., 2007). For example, incubation-induced differences in Tpref of hatchlings might have little effect on subsequent growth or survival if lizards shift Tpref in response to food availability. In some lizards, individuals may elevate their Tpref after feeding, or may select cooler Tpref when food is scarce (Brown and Griffin, 2005). Such thermophilic responses to feeding might mask or swamp developmental shifts in thermoregulatory behavior. Hence, to understand the ecological significance of incubation-induced shifts in Tpref, we also need to assess whether other sources of variation such as feeding influence the Tpref of hatchlings.

In this study, we carried out an experiment to test whether thermal conditions during incubation affected the thermal preferences of hatchling velvet geckos, Amalosia lesueurii. Velvet geckos lay eggs communally in nest crevices, and maximum daily nest temperatures are positively correlated with maximum daily air temperatures (Dayananda et al., 2016). Thermal data collected from 21 nests in 2018–2019 revealed that the slope of the relationship between air temperature and nest temperature was greater than one in 24% of nests (Cuartas-Villa and Webb, 2021). Because the frequency and intensity of heatwaves is predicted to increase in future (Cowan et al., 2020; Trancoso et al., 2020), it is likely that some nests will become hotter in future. To determine how such changes might affect phenotypic traits of hatchlings, we incubated eggs under a “cold” (mean = 24.3°C, range 18.4–31.1°C) and “hot” treatment (mean = 28.9°C, range 19.1–38.1°C) to mimic current vs. potential future nest temperatures. We predicted that hatchlings from hot incubation should have higher Tpref than hatchlings from cold incubation; i.e., local adaptation hypothesis (Levinton, 1983). Our null hypothesis was that incubation temperature would not influence Tpref. However, it is possible that developmental shifts in Tpref might not be detectable if Tpref is influenced by environmental conditions in the post-hatching environment. To explore these hypotheses, we measured the preferred body temperatures of hatchlings in a cost-free thermal gradient. To assess whether feeding influenced gecko body temperatures, we measured the hatchling’s body temperatures after feeding and fasting.

Materials and Methods

Study Species

The velvet gecko, Amalosia lesueurii, is a small (up to 65 mm snout to vent length), nocturnal lizard that inhabits sandstone rock outcrops from south eastern New South Wales to south-eastern Queensland (Cogger, 2014). By day the geckos thermoregulate under small, sun-exposed stones (Schlesinger and Shine, 1994; Webb et al., 2008). At dusk, they venture from their rocks or crevices to forage in leaf litter (Cogger, 2014). Female velvet geckos lay eggs in communal nests located in rock crevices in late spring, and the eggs hatch from February to March (Webb et al., 2008). After emergence, hatchlings settle under small stones located near the communal nests, and they spend the first eight months of life sheltering beneath one or two rocks (Webb, 2006). Annual observations of communal nests at three study sites in Morton National Park, NSW, have revealed that gravid geckos have laid eggs inside the same communal nests since 1992 (Webb, unpublished data). Previous studies have shown that maximum daily nest temperatures are positively correlated with maximum daily air temperatures (Dayananda et al., 2016). In some nests, the slope of the relationship between nest and air temperature is greater than one (Cuartas-Villa and Webb, 2021). Thus, temperatures inside some communal nests may increase in the future if the frequency and duration of summer heatwaves increases.

Egg Incubation Experiment

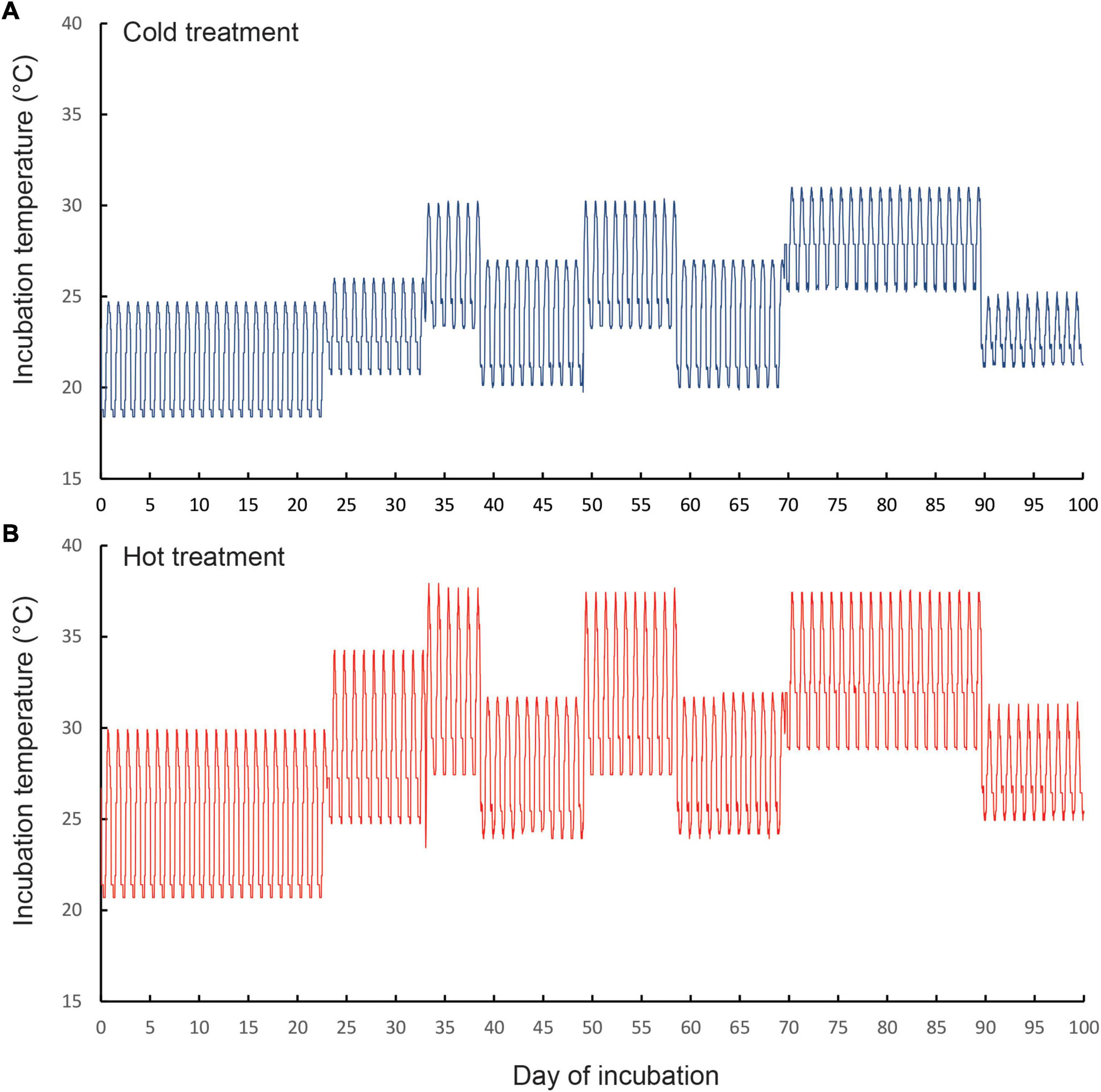

We carried out an egg incubation experiment to mimic thermal regimes inside currently used nests (hereafter, “cold”) and thermal conditions that could occur inside nests during hot summers in 2,050 (“hot”). We programmed two identical incubators (Panasonic MIR 154, 10 step functions) to mimic the cycling temperatures that occur in natural nests at our study sites, in which nest temperatures cycle on a daily basis, but get hotter during summer heatwaves (Figure 1). Temperatures inside each incubator were recorded with four miniature data loggers (Thermochron DS1922L-F5#, accuracy of ± 0.5°C) that were placed inside100 ml glass jars filled with egg incubation media (see below), and sealed with cling wrap. These were positioned at the front and rear of the top and bottom shelves of each incubator. Temperatures in the cold treatment (mean = 24.3°C, range 18.4–31.1°C, SD = 3.2°C) were similar to those recorded inside sun-exposed communal nests (Dayananda et al., 2016). Temperatures in the hot treatment (mean = 28.9°C, range 20.7°C–38.1°C, SD = 4.3°C) cycled in exactly the same way as the “cold” treatment (Figure 1), except that mean temperatures were 4.6°C higher. Temperatures in the hot treatment were on average, 2°C higher than the temperatures recorded inside four sun-exposed communal nests from Morton National Park over the period 23 November 2018 to 28 January 2019 (mean nest temperature = 26.9°C range 15.8–36.7°C, Cuartas-Villa and Webb, 2021). This treatment simulated the potential future nest temperatures that could occur in 2,050, based on the predicted increases in air temperatures between 2.9 and 4.6°C that are forecast for southeast Australia by climate modelers (Dowdy et al., 2015).

Figure 1. Thermal regimes that we programmed for the (A) cold incubation treatment and (B) hot incubation treatment. The temperature regimes of the cold treatment mimicked thermal regimes that we have recorded inside the communal nests of our focal species Amalosia lesueurii under the current climate (Cuartas-Villa and Webb, 2021). Temperature regimes of the hot treatment are potential nest temperatures likely to occur under future climates. Note that in both treatments, temperatures fluctuated daily, and increased during the incubation period, to simulate the thermal regimes that occur in natural nests over spring and summer. The three elevated spikes in temperature (at around days 35, 55, and 80 of incubation) correspond to heatwaves of varying durations.

After programming the incubators, we brought gravid females into the lab, and after oviposition, we placed eggs singly inside 100 mL glass jars filled with moist vermiculite (water potential of 200 KPa) and covered each jar with plastic food wrap to prevent the eggs from desiccating. We randomly allocated one egg from each clutch of two eggs produced by each female to each of two programmable incubators. Full details of collection of geckos, husbandry, incubation regimes, and incubation periods and hatching success, are presented elsewhere (Abayarathna et al., 2019).

Measurement of Preferred Body Temperatures

After hatching, we housed hatchlings individually in plastic containers (Sistema NZ 2.0 L, 220 × 150 × 60 mm) with a paper substrate, a plastic half pipe and a water dish. We placed the hatchling cages on timer-controlled heating cables set to 32°C, which created a thermal gradient (23–32°C) inside the cages during the day, while night time temperatures matched the room temperature of 23°C. We fed hatchlings with five pinhead crickets twice weekly, and cleaned their cages at weekly intervals. We recorded the Tbs of 22 four-week old hatchlings (10 hot-incubated and 12 cold-incubated hatchlings, all from Dharawal) inside a thermal gradient. We did not measure the lizards’ preferred body temperatures prior to this age as the hatchlings were used in another study in which we measured their learning abilities using a Y maze apparatus (Abayarathna and Webb, 2020). We recognize that testing hatchlings at 4 weeks of age is a limitation of our study; however, if incubation temperatures induce biologically meaningful shifts in hatchling preferred body temperatures, such effects should be detectable in the first eight weeks of life (Buckley et al., 2007).

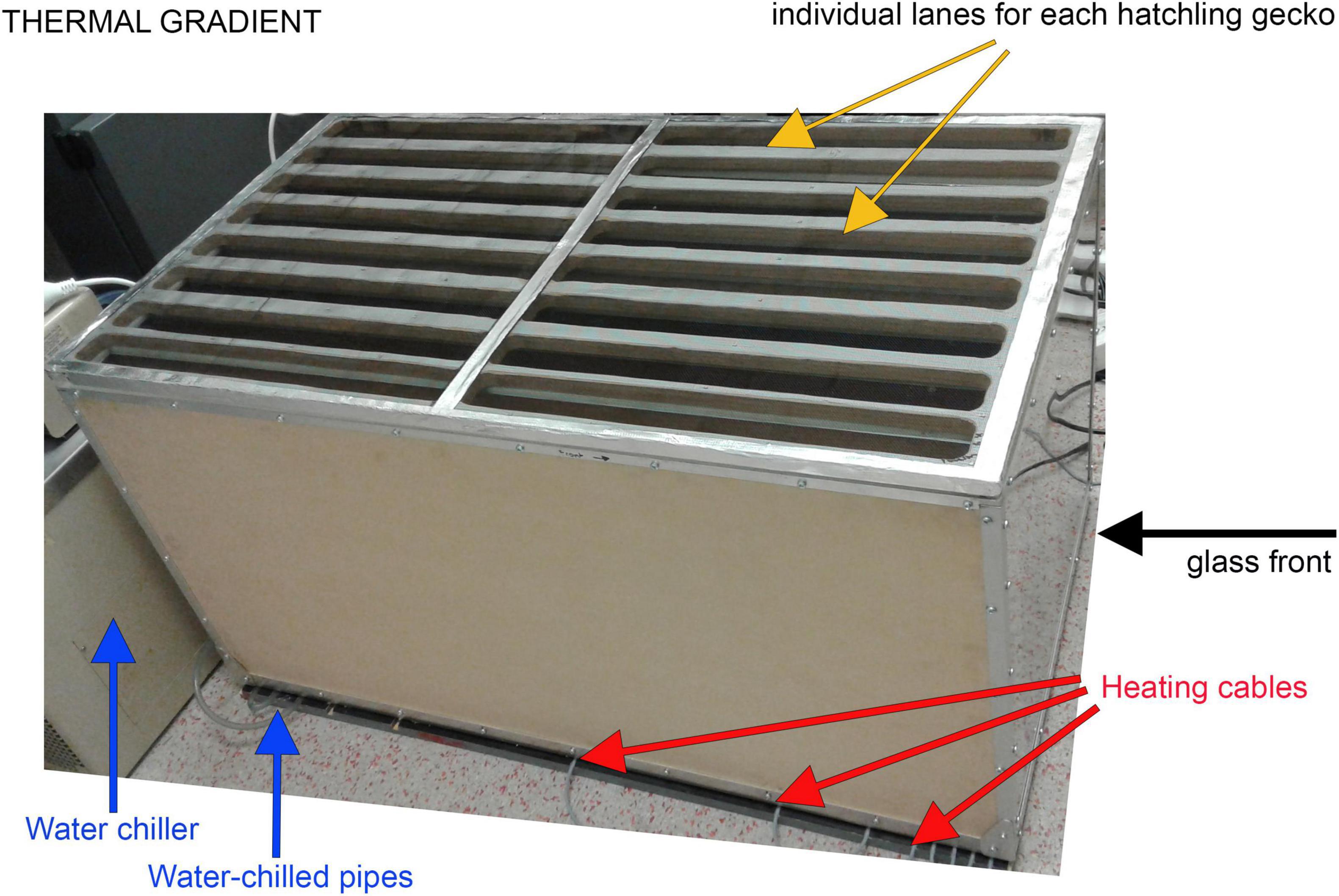

The thermal gradient consisted of a wooden enclosure (1.5 m long × 0.5 m wide × 0.5 m high) with a mesh lid and a clear glass front at one end (Figure 2). We partitioned the enclosure into 8 lanes, each 1.5 m long and 6 cm wide, each of which contained a 1.4 m long white plastic half pipe as a shelter, with a water dish in the middle. To create the thermal gradient, we placed the cage on a wooden base that contained heating cables at one end, and plastic tubes connected to a water bath (Haake F3 K Circulating Water Bath) carrying chilled water (5°C) at the other end (Figure 2). Two 250-watt infrared lamps provided additional heating at the hot end. The substrate temperatures within the thermal gradient ranged from 10 to 40°C. To measure the substrate temperature within the gradient, we placed miniature data loggers (Thermochron i-buttons, factory calibrated and accurate to ± 0.1°C) along the floor of each lane. The data loggers recorded the temperature every 60 min.

Figure 2. Photograph of the thermal gradient used to measure preferred body temperatures of hatchling velvet geckos. Each gecko was placed in a separate runway, which contained a plastic half pipe for shelter, and a water dish. Two 250-watt infrared lamps provided additional heating at the hot end (not shown in the photo).

To measure the preferred Tb of the hatchlings, we placed each hatchling in the middle of each lane of the thermal gradient at 0900 h. We estimated thermal preferences of hatchlings during the day because the geckos thermoregulate under rocks during the day time, as do other geckos (Kearney and Predavec, 2000). After 1 h of acclimation, we observed the location of each hatchling though the front glass wall, and recorded the numbers of the data loggers nearest to the lizard. If we could not see the hatchling, we confirmed its position by gently lifting the half pipe without disturbing the animal. In such cases, we recorded the lizard’s Tb with an infrared thermometer (Cool Tech, CT663, spot diameter = 13 mm). We repeated this procedure every hour from 1,000 to 1,700 h. We used substrate temperature as a proxy for lizard Tb (Buckley et al., 2007; Goodman and Walguarnery, 2007) because the hatchlings small body size (SVL < 30 mm, mass < 0.55 g) precluded the use of cloacal probes. In addition, the Tb of small lizards can change rapidly within seconds of handling, so aside from the risk of injuring the lizard, cloacal probes may not provide accurate estimates of hatchling Tbs. In addition, the capture of lizards could affect their subsequent behavior within the thermal gradient, which could affect their Tb. Although our method was crude, substrate temperatures recorded from data loggers near lizards were positively correlated with lizard temperatures that were measured with the IR thermometer (r2 = 0.94, P < 0.001). To assess whether feeding influenced the Tb of hatchling geckos, we tested lizards under their normal feeding regime. The order of feeding was counterbalanced across each cohort to avoid any possibility of an order effect influencing results. For the fasted treatment, lizards were not fed for 5 days prior to placement in the thermal gradient, which allowed us to compare our results with other studies on lizards (Brown and Griffin, 2005).

Statistical Analyses

For each individual lizard, we calculated the mean body temperature (Tb) in the thermal gradient, and the 25 and 75% quartiles, after feeding, and prior to feeding (Hertz et al., 1993). These metrics allowed us to compare the preferred body temperatures of hatchlings before and after feeding. To determine whether incubation treatment or feeding status affected hatchling body temperatures, we used repeated-measures ANOVA. In this analysis, hatchling body temperature was the dependent variable, while hour of day, and feeding status were the within subjects effects, and incubation treatment was the between subjects effect. Although we used a split-clutch design, and placed one egg from each clutch of two eggs into each incubator, only two hatchlings had the same mother. For this reason, we did not include maternal ID as a factor in our analyses. Prior to carrying out the analysis, we checked that data met the assumptions of homogeneity of variances (Levene’s test, P = 0.31) and were normally distributed (Shapiro-Wilks tests). As data transformations did not solve the problem of non-normality, we elected not to transform raw data prior to the analysis, as ANOVA is robust to departures of normality (Schmider et al., 2010). However, because the data did not meet the assumptions of sphericity for hour (Mauchley’s W = 0.038, P = 0.001) or feeding × hour (Mauchley’s W = 0.066, P = 0.01), we used the Greenhouse-Geisser correction for determining the significance of F-tests (Field, 2013). We ran statistical analyses using SPSS version 26.

Results

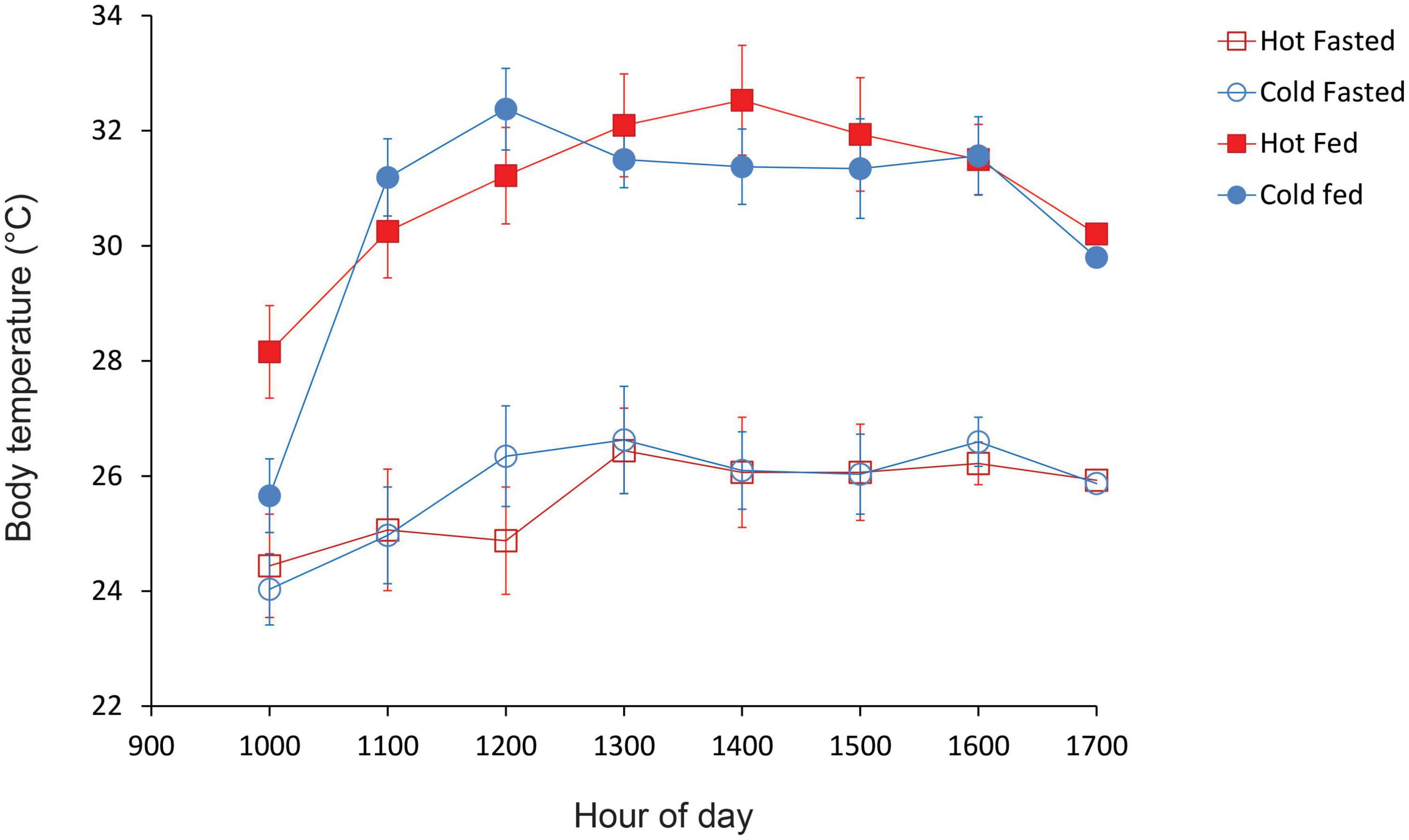

Lizards from both hot and cold incubation treatments showed very similar patterns of thermoregulation (Figure 3), and had similar preferred Tbs before feeding (mean Tbs = 25.9 and 25.7°C, respectively) and after feeding (mean Tbs = 30.7 and 30.4°C, respectively). Both cold-incubated and hot-incubated lizards showed similar patterns of thermoregulation, with hatchlings maintaining higher body temperatures (Tbs) after midday than during the morning (Fig. 3). Lizard body temperatures varied significantly with hour of day [F(3.4, 68.6) = 20.73, P < 0.01], but there was no interaction between hour and incubation treatment [F(3.4, 85.4) = 2.25, P = 0.08] nor between feeding status, incubation treatment and hour [F(3.4, 85.4) = 0.99, P = 0.42]. However, lizard feeding status significantly affected body temperatures, with lizards maintaining higher Tbs after feeding than prior to feeding [F(1,20) = 206.78, P = 0.0001, Figure 3]. There was also a significant interaction between feeding status and hour [F(4.3, 85.4) = 3.97, P = 0.004], reflecting the fact that at 10 a.m., 1 h after being placed in the gradient, body temperatures of fed and unfed lizards were similar (Figure 3). Thereafter, body temperatures of recently-fed lizards were higher than those of fasted lizards during each hour of the day (Figure 3). Lizards selected higher body temperatures in the thermal gradient after feeding (mean Tb = 30.6°C, IQR = 29.6–32.0°C, range = 23.5–35.5°C) than before feeding (mean Tb = 25.8°C, IQR = 24.7–26.9°C, range = 20.0–32.5°C). Overall, there was no significant effect of incubation treatment on hatchling Tbs [F(1, 20) = 0.13, P = 0.73] and no interaction between feeding status and incubation treatment [F(1,20) = 0.04, P = 0.84].

Figure 3. Mean Tbs of cold-incubated and hot-incubated hatchling velvet geckos that were placed inside a thermal gradient between 0900 and 1,500 h. Figure shows the temperature profiles of recently fed lizards and lizards that were fasted for 5 days. Error bars denote standard errors.

Discussion

We predicted that hatchlings from the hot incubation treatment would select higher preferred body temperatures (Tpref) than hatchlings from the cold treatment. Contrary to our prediction, we found no evidence that incubation temperatures affected the thermal preferences of 4-week old hatchlings. Indeed, mean selected Tbs of cold- and hot-incubated hatchlings were very similar, as was the precision of thermoregulation (Figure 3). Although we measured body temperatures of hatchlings at age four weeks, our findings agree with the results of previous studies, which found no effect of incubation temperatures on selected Tbs of hatchlings during the 2 months of life in veiled chameleons Chamaeleo calyptratus (Andrews, 2008), and western fence lizards Sceloporus occidentalis (Buckley et al., 2007). Other studies reported no effect of incubation on selected Tbs of 1-week old three lined skinks Bassiana duperreyi (Du et al., 2010) or 14–16 month old Cuban rock iguanas Cyclura nubila (Alberts et al., 1997). By contrast, other studies have reported that incubation temperatures can influence the thermoregulatory behavior of hatchlings. For example, in western fence lizards hatchlings from a warm-incubation treatment thermoregulated more precisely than lizards from a cool-incubation treatment, and this effect persisted for at least seven weeks post hatching (Buckley et al., 2007). In the Madagascar ground gecko, Paroedura pictus, hatchlings from a hot incubation treatment maintained higher dorsal temperatures prior to crossing between the cold and hot sides of a thermal shuttle apparatus at night, and this effect persisted for several weeks after hatching (Blumberg et al., 2002). Studies on other ectotherms suggest that as for reptiles, the effects of developmental temperatures on preferred body temperatures are mixed (Dillon et al., 2009). For example, in some Drosophila species, flies reared at 25°C had higher Tpref than those reared at 20°C (Yamamoto and Ohba, 1984). In Drosophila melanogaster, adults selected lower temperatures when reared at 28°C than when reared at 19 or 25°C (Krstevska and Hoffmann, 1994). These mixed results suggest that like other traits, reaction norms for thermal preferences may be non-linear (Noble et al., 2018). Hence, we cannot rule out the possibility that intermediate incubation temperatures might affect preferred Tbs of velvet geckos. Future studies, using intermediate temperatures, and larger sample sizes, would help resolve this issue.

Ultimately, the biological relevance of incubation-induced shifts in preferred Tbs will depend on the magnitude and duration of such effects relative to other sources of environmental variation (Booth, 2018). Notably, several studies have shown that incubation-induced shifts in Tb are transitory, so are unlikely to influence traits linked to fitness (Buckley et al., 2007; Goodman and Walguarnery, 2007). In the present study, hatchlings maintained significantly higher Tbs after feeding (fed: mean Tb = 30.6°C; fasted mean Tb = 25.8°C), demonstrating that food availability has large effects on hatchling Tbs. Thermophilic responses to feeding are widespread in snakes (Blouin-Demers and Weatherhead, 2001) but are less common in lizards (Wall and Shine, 2008; Schuler et al., 2011). Notably, the 4.8°C increase in mean Tb of hatchling geckos after feeding is similar to that reported for snakes in thermal gradients (typically, increases of 2–6°C (Lysenko and Gillis, 1980; Slip and Shine, 1988; Tsai and Tu, 2005), but is higher than the 3.1°C increase reported for adults of our study species (Dayananda and Webb, 2020), or the modest increases (typically, <2°C), reported for lizards such as Heloderma suspectum (Gienger et al., 2013) and Anolis carolinensis (Brown and Griffin, 2005). Future studies on hatchlings of other lizard species in this respect, particularly geckos, would help to evaluate the generality of our results.

Why do fasted hatchlings select lower Tbs than recently fed individuals? After feeding, selection of higher Tbs likely maximizes digestive efficiency and rates of energy assimilation (Harlow et al., 1976; Beaupre et al., 1993). However, because metabolic rates scale with Tb, maintenance of high Tbs increases energy expenditure (Angilletta, 2009). Therefore, in the absence of food, hatchlings may select lower Tbs to reduce energy expenditure. Conserving energy might be particularly important for hatchlings, as they may lack sufficient energy reserves in their tails to survive long periods in the absence of food (Greer, 1989). Ultimately, shifts in Tb in response to food availability may represent a trade-off between energy conservation vs. maintenance of other fitness related behaviors (Huey, 1982). For example, adults of Yarrow’s spiny lizard Sceloporus jarrovi that were deprived of food for five days maintained high Tbs, presumably so they could maximize important fitness related behaviors such as territory defense (Schuler et al., 2011). In the wild, hatchling velvet geckos congregate under rocks near communal nest sites, and hatchlings often share rocks with conspecifics during the first few months of life (Webb, 2006), so territory defense may be unimportant during this period.

Irrespective of feeding status, hatchling geckos displayed diel variation in preferred Tbs. Hatchlings selected low Tbs in the morning, and thereafter they raised their Tb and maintained elevated temperatures throughout the afternoon (Figure 3). Similar diel patterns of thermoregulation were reported for individuals of two gecko species, Eublepharis macularius and Oedura marmorata, that were fasted for 3 days before being placed in a thermal gradient (Angilletta et al., 1999). Similarly, individuals of the gecko Tarentola mauritanica increased their Tbs during the day (Gill, 1994). The underlying cause for this pattern of thermoregulation in geckos is not known, but we note that Tbs of hatchling A. lesueurii follow the same pattern as rock temperatures; i.e., delayed heating, reaching a peak in early afternoon (Webb and Shine, 1998). Potentially, this pattern might represent an entrained circadian rhythm for activity or thermoregulation (Refinetti and Susalka, 1997; Tawa et al., 2014). Because hatchling geckos commence foraging shortly after dusk, maintaining high Tbs around dusk would aid in prey capture and potentially, escape from predators (Christian and Tracy, 1981). As for diurnal lizards, maintenance of high Tbs during daylight hours would facilitate physiological processes such as digestion, growth and sloughing (Huey, 1982; Angilletta et al., 1999).

Conclusion

In conclusion, we found no effects of incubation temperature on the thermal preference of hatchling velvet geckos. However, there was a strong effect of feeding status on the hatchlings thermal preference, suggesting that food availability may influence thermoregulation by hatchlings in the wild. To evaluate the role of thermal developmental plasticity on the thermal preferences of hatchling lizards, future studies should not only estimate the duration of such effects, but also, their magnitude relative to plasticity caused by the post-hatching environment.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics Statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by University of Technology Animal Care and Ethics Committee.

Author Contributions

TA and JW contributed to conception, design of the study, contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted and revised versions. TA carried out the experiments, wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and organized the database. JW performed the statistical analysis and edited the manuscript. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was supported by a postgraduate research support grant from the University of Technology Sydney (to TA).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We thank Reannan Honey and our volunteers for their help with fieldwork and Gemma Armstrong, Paul Brooks, and Susan Fenech for their technical support in the laboratory. Rowena Morris (NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service) kindly provided us with access to study sites in Dharawal National Park. Graham Alexander and Dan Warner, and two reviewers provided constructive comments and suggestions that helped to improve an earlier version of the manuscript. The procedures described herein were approved by the UTS Animal Care and Ethics Committee (protocol # 2012000256 to JW), and were carried out under a NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service scientific license (SL 101013 to JW).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fevo.2021.727602/full#supplementary-material

References

Abayarathna, T., and Webb, J. K. (2020). Effects of incubation temperatures on learning abilities of hatchling velvet geckos. Anim. Cogn. 23, 613–620. doi: 10.1007/s10071-020-01365-4

Abayarathna, T., Murray, B. R., and Webb, J. K. (2019). Higher incubation temperatures produce long-lasting upward shifts in cold tolerance, but not heat tolerance, of hatchling geckos. Biol. Open 8:bio042564. doi: 10.1242/bio.042564

Alberts, A. C., Perry, A. M., Lemm, J. M., and Phillips, J. A. (1997). Effects of incubation temperature and water potential on growth and thermoregulatory behavior of hatchling Cuban rock iguanas (Cyclura nubila). Copeia 1994, 766–776. doi: 10.2307/1447294

Andrews, R. M. (2008). Effects of incubation temperature on growth and performance of the veiled chameleon (Chamaeleo calyptratus). J. Exp. Zool. A Ecol. Genet. Physiol. 309, 435–446. doi: 10.1002/jez.470

Andrews, R. M., and Warner, D. A. (2002). Nest-site selection in relation to temperature and moisture by the lizard Sceloporus undulatus. Herpetologica 58, 399–407.

Andrews, R. M., Mathies, T., and Warner, D. A. (2000). Effect of incubation temperature on morphology, growth, and survival of juvenile Sceloporus undulatus. Herpetol. Monographs 14, 420–431. doi: 10.2307/1467055

Angilletta, M. J. (2009). Thermal Adaptation: a Theoretical and Empirical Synthesis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Angilletta, M. J., Montgomery, L. G., and Werner, Y. L. (1999). Temperature preference in geckos: diel variation in juveniles and adults. Herpetologica 55, 212–222.

Beaupre, S. J., Dunham, A. E., and Overall, K. L. (1993). The effects of consumption rate and temperature on apparent digestibility coefficient, urate production, metabolizable energy coefficient and passage time in canyon lizards (Sceloporus merriami) from two populations. Funct. Ecol. 7, 273–280.

Blouin-Demers, G., and Weatherhead, P. J. (2001). An experimental test of the link between foraging, habitat selection and thermoregulation in black rat snakes Elaphe obsoleta obsoleta. J. Anim. Ecol. 70, 1006–1013.

Blumberg, M. S., Lewis, S. J., and Sokoloff, G. (2002). Incubation temperature modulates post-hatching thermoregulatory behavior in the Madagascar ground gecko, Paroedura pictus. J. Exp. Biol. 205, 2777–2784.

Booth, D. T. (2018). Incubation temperature induced phenotypic plasticity in oviparous reptiles: where to next? J. Exp. Zool. A Ecol. Integr. Physiol. 329, 343–350. doi: 10.1002/jez.2195

Brown, R. P., and Griffin, S. (2005). Lower selected body temperatures after food deprivation in the lizard Anolis carolinensis. J. Therm. Biol. 30, 79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2004.07.005

Buckley, C. R., Jackson, M., Youssef, M., Irschick, D. J., and Adolph, S. C. (2007). Testing the persistence of phenotypic plasticity after incubation in the western fence lizard, Sceloporus occidentalis. Evol. Ecol. Res. 9, 169–183.

Carlo, M. A., Riddell, E. A., Levy, O., and Sears, M. W. (2018). Recurrent sublethal warming reduces embryonic survival, inhibits juvenile growth, and alters species distribution projections under climate change. Ecol. Lett. 21, 104–116. doi: 10.1111/ele.12877

Christian, K. A., and Tracy, C. R. (1981). The effect of the thermal envrionment on the ability of hatchling land iguanas to avoid predation during dispersal. Oecologia 49, 218–223. doi: 10.1007/BF00349191

Cowan, T., Hegerl, G., and Harrington, L. (2020). Present-day greenhouse gases could cause more frequent and longer Dust Bowl heatwaves. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 505–510.

Cuartas-Villa, S., and Webb, J. K. (2021). Nest site selection in a southern and northern population of the velvet gecko (Amalosia lesueurii). J. Therm. Biol. 102:103121. doi: 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2021.103121

Dayananda, B., and Webb, J. K. (2020). Thermophilic response to feeding in adult female velvet geckos. Curr. Zool. 66, 693–694. doi: 10.1093/cz/zoaa022

Dayananda, B., Gray, S., Pike, D., and Webb, J. K. (2016). Communal nesting under climate change: fitness consequences of higher nest temperatures for a nocturnal lizard. Glob. Change Biol. 22, 2405–2414. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13231

Dayananda, B., Murray, B. R., and Webb, J. K. (2017). Hotter nests produce hatchling lizards with lower thermal tolerance. J. Exp. Biol. 220, 2159–2165. doi: 10.1242/jeb.152272

Deeming, D. C. (2004). “Post-hatching phenotypic effects of incubation in reptiles,” in Reptilian Incubation: Environment, Evolution and Behaviour, ed. D. C. Deeming (Nottingham: Nottingham University Press), 229–251.

Deeming, D. C., and Ferguson, M. W. J. (1991). “Physiological effects of incubation temperature on embryonic development in reptiles and birds,” in Egg Incubation: Its Effects on Embryonic Development in Birds and Reptiles, eds D. C. Deeming and M. W. J. Ferguson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 147–171.

Dillon, M. E., Wang, G., Garrity, P. A., and Huey, R. B. (2009). Thermal preference in Drosophila. J. Therm. Biol. 34, 109–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2008.11.007

Dowdy, A., Abbs, D., Bhend, J., Chiew, F., Church, J., Ekstrom, M., et al. (2015). East Coast Cluster Report, Climate Change in Australia Projections for Australia’s Natural Resource Management Regions: Cluster Reports, eds M. Ekstrom, P. Whetton, C. Gerbing, M. Grose, L. Webb, and J. Risbey (Melbourne, VIC: CSIRO and Bureau of Meteorology).

Du, W., Elphick, M., and Shine, R. (2010). Thermal regimes during incubation do not affect mean selected temperatures of hatchling lizards (Bassiana duperreyi, Scincidae). J. Therm. Biol. 35, 47–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2009.10.007

Esquerre, D., Keogh, J. S., and Schwanz, L. E. (2014). Direct effects of incubation temperature on morphology, thermoregulatory behaviour and locomotor performance in jacky dragons (Amphibolurus muricatus). J. Therm. Biol. 43, 33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2014.04.007

Field, A. (2013). Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 4th Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Gienger, C. M., Tracy, C. R., and Zimmerman, L. C. (2013). Thermal responses to feeding in a secretive and specialized predator (Gila monster, Heloderma suspectum). J. Therm. Biol. 38, 143–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2012.12.004

Gill, M. (1994). Diel variation in preferred body temperatures of the Moorish gecko Tarentola mauritanica during summer. Herpetology 4, 56–59.

Goodman, R. M., and Walguarnery, J. W. (2007). Incubation temperature modifies neonatal thermoregulation in the lizard Anolis carolinensis. J. Exp. Zool. A Ecol. Genet. Physiol. 307, 439–448. doi: 10.1002/jez.397

Greer, A. E. (1989). The Biology and Evolution of Australian Lizards. Chipping Norton, NSW: Surrey Beatty and Sons.

Harlow, H. J., Hillman, S. S., and Hoffman, M. (1976). Effect of temperature on digestive efficiency in the herbivorous lizard, Dipsosaurus dorsalis. J. Comp. Physiol. B Biochem. Syst. Environ. Physiol. 111, 1–6.

Hertz, P. E., Huey, R. B., and Stevenson, R. D. (1993). Evaluating temperature regulation by field-active ectotherms: the fallacy of the inappropriate question. Am. Nat. 142, 796–818. doi: 10.1086/285573

Huey, R. B. (1982). “Temperature, physiology, and the ecology of reptiles,” in Biology of the Reptilia, eds C. Gans and F. H. Pough (Cambridge, MA: Academic Press), 25–91.

Huey, R. B., Kearney, M. R., Krockenberger, A., Holtum, J. A. M., Jess, M., and Williams, S. E. (2012). Predicting organismal vulnerability to climate warming: roles of behaviour, physiology and adaptation. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 367, 1665–1679.

Kearney, M., and Predavec, M. (2000). Do nocturnal ectotherms thermoregulate? A study of the temperate gecko Christinus marmoratus. Ecology 81, 2984–2996.

Krstevska, B., and Hoffmann, A. A. (1994). The effects of acclimation and rearing conditions on the response of tropical and temperate populations of Drosophila melanogaster and D. simulans to a temperature gradient (Diptera: Drosophilidae). J. Insect Behav. 7, 279–288.

Lang, J. W. (1987). “Crocodilian thermal selection,” in Wildlife Management: Crocodiles and Alligators, eds G. J. W. Webb, S. C. Manolis, and P. J. Whitehead (Chipping Norton, NSW: Surrey Beatty & Sons Pty Ltd), 301–317.

Levinton, J. S. (1983). The latitudinal compensation hypothesis: growth data and a model of latitudinal growth differentiation based upon energy budgets. I. Interspecific comparison of Ophryotrocha (Polychaeta: Dorvilleidae). Biol. Bull. 165, 686–698. doi: 10.2307/1541471

Lysenko, S., and Gillis, J. E. (1980). The effect of ingestive status on the thermoregulatory behavior of Thamnophis sirtalis sirtalis and Thamnophis sirtalis parietalis. J. Herpetol. 14, 155–159.

Mitchell, N. J., Kearney, M. R., Nelson, N. J., and Porter, W. P. (2008). Predicting the fate of a living fossil: how will global warming affect sex determination and hatchling phenology in tuatara. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 275, 2185–2193. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2008.0438

Noble, D. W., Stenhouse, V., and Schwanz, L. E. (2018). Developmental temperatures and phenotypic plasticity in reptiles: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biol. Rev. 93, 72–97. doi: 10.1111/brv.12333

Qualls, C. P., and Andrews, R. M. (1999). Cold climates and the evolution of viviparity in reptiles: cold incubation temperatures produce poor-quality offspring in the lizard, Sceloporus virgatus. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 67, 353–376. doi: 10.1006/bijl.1998.0307

Refinetti, R., and Susalka, S. J. (1997). Circadian rhythm of temperature selection in a nocturnal lizard. Physiol. Behav. 62, 331–336. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(97)88989-5

Refsnider, J. M., Clifton, I. T., and Vazquez, T. K. (2019). Developmental plasticity of thermal ecology traits in reptiles: trends, potential benefits, and research needs. J. Therm. Biol. 84, 74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2019.06.005

Reynolds, J. D., Goodwin, N. B., and Freckleton, R. P. (2002). Evolutionary transitions in parental care and live bearing in vertebrates. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 357, 269–281. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2001.0930

Schlesinger, C. A., and Shine, R. (1994). Selection of diurnal retreat sites by the nocturnal gekkonid lizard Oedura lesueurii. Herpetologica 50, 156–163.

Schmider, E., Ziegler, M., Danay, E., Beyer, L., and Bühner, M. (2010). Is it really robust? Methodology 6, 147–151.

Schuler, M. S., Sears, M. W., and Angilletta, M. J. (2011). Food consumption does not affect the preferred body temperature of Yarrow’s spiny lizard (Sceloporus jarrovi). J. Therm. Biol. 36, 112–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2010.12.002

Shine, R. (2004). Seasonal shifts in nest temperature can modify the phenotypes of hatchling lizards, regardless of overall mean incubation temperature. Funct. Ecol. 18, 43–49.

Shine, R., and Harlow, P. S. (1996). Maternal manipulation of offspring phenotypes via nest-site selection in an oviparous lizard. Ecology 77, 1808–1817.

Slip, D. J., and Shine, R. (1988). Thermophilic response to feeding of the diamond python, Morelia s. spilota (Serpentes: Boidae). Comp. Biochem. Physiol A Physiol. 89, 645–650. doi: 10.1016/0300-9629(88)90847-x

Tawa, Y., Jono, T., and Numata, H. (2014). Circadian and temperature control of activity in Schlegel’s Japanese gecko, Gekko japonicus (Reptilia: Squamata: Gekkonidae). Curr. Herpetol. 33, 121–128. doi: 10.5358/hsj.33.121

Trancoso, R., Syktus, J., Toombs, N., Ahrens, D., Wong, K. K.-H., and Pozza, R. D. (2020). Heatwaves intensification in Australia: a consistent trajectory across past, present and future. Sci. Total Environ. 742:140521. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140521

Tsai, T.-S., and Tu, M.-C. (2005). Postprandial thermophily of Chinese green tree vipers, Trimeresurus s. stejnegeri: interfering factors on snake temperature selection in a thigmothermal gradient. J. Therm. Biol. 30, 423–430.

Wall, M., and Shine, R. (2008). Post-feeding thermophily in lizards (Lialis burtonis Gray, Pygopodidae): laboratory studies can provide misleading results. J. Therm. Biol. 33, 274–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2008.02.005

Warner, D. A., and Shine, R. (2008). The adaptive significance of temperature-dependent sex determination in a reptile. Nature 451, 566–568. doi: 10.1038/nature06519

Webb, J. K. (2006). Effects of tail autotomy on survival, growth and territory occupation in free-ranging juvenile geckos (Oedura lesueurii). Austral Ecol. 31, 432–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9993.2006.01631.x

Webb, J. K., and Shine, R. (1998). Using thermal ecology to predict retreat-site selection by an endangered snake species. Biol. Conserv. 86, 233–242.

Webb, J. K., Pike, D. A., and Shine, R. (2008). Population ecology of the velvet gecko, Oedura lesueurii in south eastern Australia: implications for the persistence of an endangered snake. Austral Ecol. 33, 839–847.

West-Eberhardt, M. J. (2003). Developmental Plasticity and Evolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

While, G. M., Noble, D. W. A., Uller, T., Warner, D. A., Riley, J. L., Du, W.-G., et al. (2018). Patterns of developmental plasticity in response to incubation temperature in reptiles. J. Exp. Zool. A Ecol. Integr. Physiol. 329, 162–176. doi: 10.1002/jez.2181

Keywords: heatwave, nest temperature regulation, reptile, developmental plasticity, climate change

Citation: Abayarathna T and Webb JK (2021) Do Incubation Temperatures Affect the Preferred Body Temperatures of Hatchling Velvet Geckos? Front. Ecol. Evol. 9:727602. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2021.727602

Received: 19 June 2021; Accepted: 16 November 2021;

Published: 08 December 2021.

Edited by:

J. Sean Doody, University of South Florida, United StatesReviewed by:

Anindita Bhadra, Indian Institute of Science Education and Research Kolkata, IndiaRichard Anthony Peters, La Trobe University, Australia

Copyright © 2021 Abayarathna and Webb. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jonathan K. Webb, Sm9uYXRoYW4ud2ViYkB1dHMuZWR1LmF1

Theja Abayarathna

Theja Abayarathna Jonathan K. Webb

Jonathan K. Webb