94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

POLICY AND PRACTICE REVIEWS article

Front. Ecol. Evol., 02 March 2021

Sec. Conservation and Restoration Ecology

Volume 9 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2021.645427

This article is part of the Research TopicTowards Legal, Sustainable and Equitable Wildlife TradeView all 19 articles

China is among the world’s leading consumer markets for wildlife extracted both legally and illegally from across the globe. Due to its mega-richness in biodiversity and strong economic ties with China, Southeast Asia (SEA) has long been implicated as a source and transit hub in the transnational legal and illegal wildlife trade with China. Although several cross-border and domestic wildlife enforcement mechanisms have been established to tackle this illegal trade in the region, international legal cooperation and policy coordination between China and its SEA neighbors remain limited in both scope and effectiveness. Difficulties in investigating and prosecuting offenders in overseas jurisdictions, as well as organized criminal groups that sustain the illicit supply chain, continue to undermine efforts by the region’s governments to combat wildlife trafficking. In addition to reviewing the key trends in both the legal and illegal wildlife trade between SEA and China, this paper examines existing legal and policy frameworks in SEA countries and China, and provides a synthesis of evidence on the latest developments in regional efforts to curtail this multibillion-dollar trade. In particular, it discusses how proactive and effective China has been in cooperating with its SEA neighbors on this issue. The paper also draws on the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (UNTOC) framework to suggest pathways to deepen legal cooperation between China and SEA countries in order to disrupt and dismantle transnational wildlife trafficking in the region.

As one of the world’s leading consumer markets, China’s role in shaping the international trade in legal and illegal wildlife (specifically fauna species) cannot be understated (e.g., Nijman, 2010; UNODC, 2016). Over the past two decades, China’s market for wildlife products has continually and markedly expanded (Jiao and Lee, in press)—a trend triggered largely by the country’s economic boom, increased consumer affluence (CSRI, 2020) and traditional utilitarian culture that treats wildlife as an exploitable resource (Zhang et al., 2008; Zhang and Yin, 2014). This expansion in China’s appetite for wildlife products (e.g., medicines, meat, skins) has further contributed to the growth in the scale and scope of the global wildlife trade. Partly owing to a reduction in the country’s biodiversity (NFGA, 2008; MEE and CAS, 2015), much of the wildlife found in the Chinese market has overseas origins and will have entered through both legal and illegal channels.

Due to its mega-richness in biodiversity, geographical proximity and strong economic ties with China, Southeast Asia (SEA) has long been implicated in this legal and illegal trade (Li and Li, 1998; Li et al., 2000). Countries in the region have functioned variously as sources, transit routes and distributing hubs, as well as destination markets for high-value, endangered species of wildlife fauna (e.g., elephant ivory, pangolin scales) (Krishnasamy and Zavagli, 2020). Especially with countries such as Cambodia and Lao PDR (hereafter, Laos) serving as “hotspots” for wildlife poaching and smuggling, the illegal wildlife trade (IWT)—whilst very lucrative—poses a significant threat to the region’s biodiversity, human health and collective security (Sodhi et al., 2004; Hughes, 2017). Moreover, given that the wildlife products trafficked in the region are often illegally sourced from South Asia and Africa, being destined for the mainland Chinese market (UNODC, 2019), this invokes a shared responsibility for China and its SEA neighbors to combat transnational wildlife trafficking.

This paper begins by reviewing the status quo of legal and illegal wildlife trading between SEA and China. It then examines the existing legal and policy frameworks in SEA countries and China, and the extent to which they support more efficient criminal justice responses, interagency coordination and intergovernmental cooperation in the fight against the multibillion-dollar illegal trade. This is followed by a synthesis of evidence on the latest developments in regional efforts by China, individual SEA countries and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), to identify key chokepoints and improve transnational cooperation to tackle wildlife trafficking. In so doing, the paper also considers how proactive and effective China has been in cooperating with its SEA neighbors on this issue. Focusing on the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (UNTOC), this paper finally turns to discuss the value of international legal instruments to enhancing China-SEA legal cooperation to disrupt and curtail the transnational illegal wildlife trade.

One caveat warrants note here. Given the difficulty in gaining access to primary data on IWT globally and regionally, this paper draws on available estimates, seizure reports, official statements and media releases, as well as news media sources—some of which may not be very recent (i.e., from 2019 or 2020) due to data limitations—to illustrate the nature and scale of transnational wildlife trafficking between SEA and China.

The legal wildlife trade between SEA and China is substantial and growing in both scale and scope. Analysis of trade records collated from the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) Trade Database revealed that between 1997–2016,1 approximately 3.8 million CITES-listed, live vertebrates (e.g., amphibians, birds, fish, mammals, reptiles) and 1.4 million whole organism equivalents (WOEs)—mainly comprised of body parts and products (e.g., claws, heads, skins)—were imported into China from SEA. The average annual import volume is 259,695 WOEs, accounting for around 45% of China’s legitimate global imports of CITES-listed vertebrates which are estimated at 0.6 million WOEs per year (Jiao and Lee, in press).

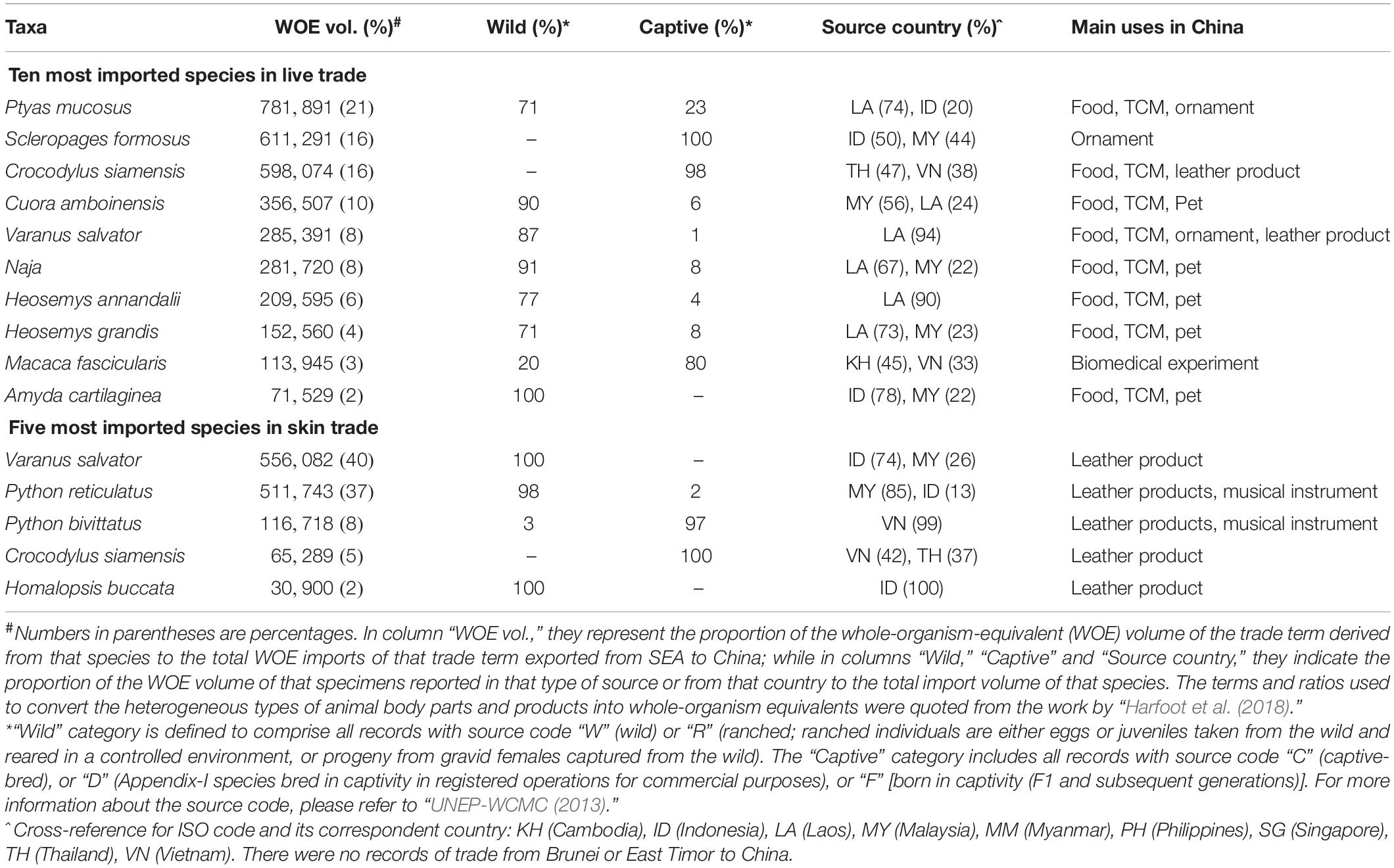

This trade is commercially oriented and feeds into five key industries: fashion, traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), food, pets and ornaments, and musical instruments (Table 1). Live animals and skins have consistently dominated the trade, with each accounting for 72% and 27% of China’s total imports from SEA, respectively. Further, China’s sourcing of legal wildlife from SEA has largely focused on a few SEA countries and a handful of reptile species: 79% of its imports from the region were supplied by three SEA countries (Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia), with 88% of the imports made up of ten species [e.g., common water monitor (Varanus salvator), Indian rat snake (Ptyas mucosus), Siamese crocodile (Crocodylus siamensis); Table 1].

Table 1. Most commonly traded species in China’s legal wildlife imports from Southeast Asia during 1997–2016, broken down by live animals and skins (Data source: CITES Trade Database 1997–2016).

Over half (60%) of the animals and their derivatives traded from SEA to China reportedly originate from wild and ranching sources. Speaking to an overarching trend which sees wild-caught specimens dominating SEA’s wildlife exports to the rest of the world (Nijman, 2010), this presents the risk of illegal, wild-extracted animals being laundered into the legal supply chain prior to export (Lyons and Natusch, 2011; Natusch and Lyons, 2012). Certainly, it is noteworthy how nearly half of the total species found in China’s illegal wildlife trade can also be seen in the legal trade (Jiao and Lee, in press). As such, given the large volume of wild-sourced wildlife involved in the legal trade, coupled with the absence of effective regulation of wild harvesting in source countries like Indonesia (China’s major supplier of wild-sourced reptile skins in SEA) (Nijman and Shepherd, 2009; UNODC, 2016), this underscores an exigent need for institutional and regulatory innovation to better facilitate information and knowledge exchange of sustainable wild extraction and farming practices, improve source countries’ certification schemes, and streamline the implementation of proper licensing and registration to prevent species over-exploitation.

With Southeast Asia serving as one of the world’s major gateways to the illegal wildlife trade, the regional black-market value of these illicit products is estimated to reach billions of dollars each year (Felbab-Brown, 2011; UNODC, 2013). Even so, the “underground” nature of the trade, combined with data limitations, means that it remains difficult to gauge the full value and magnitude of IWT within the region. Aside from SEA’s geographical proximity to China and other consumer markets in Asia (e.g., Japan, South Korea), a plethora of other factors have also contributed to this reality, ranging from inadequate legislation and poorly resourced law enforcement to high levels of corruption, endemic poverty, as well as improved transport links within the region (Grieser-Johns and Thomson, 2005; Ngoc and Wyatt, 2013; Brook et al., 2014). Indeed, increased connectivity due to the rapid expansion of the digital economy and physical infrastructure projects, as a result of China’s Belt and Road Initiative and other regional initiatives, indicate how the IWT problem may intensify in scale and severity in the near future. Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, which has curbed certain forms of organized crime, transnational criminal entrepreneurs have also become more adaptive in their strategies to evade law enforcement, infiltrate the legal economy and proceed with “business as usual” (UNODC, 2020a).

Owing to unsustainable hunting and poaching, most large animals (> 1 kg) have experienced a precipitous decline in their populations across the SEA region (Harrison et al., 2016). Highly valued species, such as the Chinese pangolin (Challender et al., 2014), Indochinese leopard and tiger (Lynam, 2010; Rostro-Garcia et al., 2016), Javan rhinoceros (Brook et al., 2014), and Burmese star tortoise (Platt et al., 2011) have been extirpated from much of their original range or have even gone extinct in the wild. Crucially, the depletion of the region’s wildlife resources has not only transformed the roles of certain SEA countries within the supply chain—Vietnam, for one, has evolved from a regional supplier into a key distribution center (Lin, 2005; Ngoc and Wyatt, 2013; Davis et al., 2019)—but it has also forced poachers, smugglers and illicit traders to target new source areas and alternative species as substitutes. This is exemplified by the increasing occurrence of African pangolin species on the Asian market (Heinrich et al., 2016; Gomez et al., 2016), and how leopard parts have been prescribed as alternatives to tiger parts given their relatively higher availability (Raza et al., 2012).

As noted earlier, China is known as the prime destination for a large share of the wildlife traded illicitly from SEA to the international market (UNODC, 2010). Thailand continues to be among the largest seahorse exporters in Asia, even after its export suspension in January 2016, with most ending up in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and mainland China for TCM uses (Foster et al., 2016, 2019). Bangkok has also become a global trading center for the sale of illegal ivory from Africa (Doak, 2014), as well as illegal tortoises and freshwater turtles smuggled from Africa, South Asia, and Southeast Asia to foreign tourists (Nijman and Shepherd, 2015). Due to its free port status, huge daily cargo throughput, and well-established trade links with both source and consumer countries, Singapore has likewise emerged as a prominent transit hub for the movement of illicitly sourced wildlife commodities, especially via containerized trafficking (Felbab-Brown, 2011; Krishnasamy and Zavagli, 2020).

Considering the land border shared by China and mainland SEA countries, it is unsurprising that this subregion should witness a high-level flurry of illicit trade activity over the past decade. Indeed, the cross-border supply of a variety of illegal wildlife and their derivatives has further contributed to the growth in economic activity seen in the border towns situated between China and its SEA neighbors. These towns have, in turn, evolved into the focal points for the collection, retailing and transshipment of these illicit products. Vietnam has long acted as a critical node in the illicit supply chain between SEA and China (Grieser-Johns and Thomson, 2005), with a large trading network having formed around several Vietnam-China border cities, including Mong Cai and Lang Son on the Vietnamese side (Van Song, 2003) and Dongxing, Pingxiang and Longzhou on the Chinese side (Li et al., 2010).

In Laos’ Golden Triangle Special Economic Zone, tiger pelts sourced from Thailand and Malaysia are reportedly sent to Yunnan Province and Fujian Province to tanneries, then smuggled back to the Golden Triangle area where they are sold to Chinese tourists (EIA, 2015). In the border town of Boten, a one-day market survey had recorded around 1,000 wildlife items, including bear parts, pangolin scales and elephant hides, being offered for open sale in outlets run mostly by Chinese nationals (Krishnasamy et al., 2018). Moreover, following China’s ban on the domestic commercial processing and sale of elephant ivory and related products in 2017, trafficking networks have since relocated their ivory carving and production from China to Laos and African countries, such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo (CITES Secretariat,2017a,b).

Similarly, in Cambodia’s Tonle Sap Biosphere Reserve, reports had at one point surfaced of a large volume of turtles being harvested unsustainably by local fishermen, sold to village-level dealers and later middlemen in larger cities. These middlemen would then smuggle the turtles to supply urban markets in southern China and Vietnam (Platt et al., 2008). In Myanmar, Kachin State is documented as an important gateway for overland trafficking of pangolins sourced in Myanmar, other SEA countries (Zhang et al., 2017), India, and potentially Africa (Mohapatra et al., 2015; Nijman et al., 2016), as well as for tiger pelts procured in northeast India and Nepal (UNODC, 2010). Accounts indicate how the border town of Mong La, which is located next to the Chinese township of Daluo in Yunnan Province, has become a regional hub for illegal wildlife products, especially elephant ivory, tiger and leopard parts. Most of these products are sold to Chinese customers and then taken back to China via the Daluo port (Shepherd and Nijman, 2007; Nijman and Shepherd, 2014).

With respect to maritime SEA, Indonesia and Malaysia serve as major source countries for illegal wildlife destined for the mainland Chinese and Hong Kong markets. It is estimated that in one year, around 180,000 live Southeast Asian box turtles, substantial amounts of plastrons and carapaces (Schoppe, 2009), between 200,000-450,000 live Asiatic softshell turtles, and 1.2 million tokay geckos (Nijman et al., 2012) were exported in violation of Indonesia’s quota control for the international pet, meat and TCM markets. Analysis of seizure reports for Malaysia likewise reveals how the country constitutes a key transshipment center for the trafficking of elephant ivory, Malagasy tortoises, pangolins, and rhino horns from Africa to other parts of Asia—most notably, to Hong Kong, mainland China and Vietnam (TRAFFIC,2017a,b, 2018, 2019).

To deal with the complex and multiscalar challenges posed by IWT, effective legal cooperation and policy coordination are required at both the national and transnational levels. For this to happen, however, a network of concerned and knowledgeable stakeholders at different scales of governance needs to be galvanized, and a cooperative platform established through which their expertise and resources can be pooled for a more cohesive response to wildlife trafficking. Whereas subsequent sections will focus on efforts at interstate cooperation (e.g., between wildlife regulators and enforcers) within the region to disrupt and disconnect cross-border supply chains from source to market, this section takes stock of the key policy and legal frameworks in SEA countries and China pertaining to IWT. It also considers to what extent they collectively contribute to a regulatory regime to curtail the trade.

At the national level, effective interagency coordination between wildlife regulatory and enforcement authorities is crucial. In the Chinese case, for example, formal responsibility for regulating the legal wildlife trade, as well as the prevention, detection and investigation of the illegal trade, is spread across many agencies that come under different ministries. Key ones include the National Forestry and Grassland Administration (NFGA), Forest Police (under the Ministry of Public Security), Bureau of Fisheries (under the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs), General Administration of Customs and its Anti-Smuggling Bureau, Ministry of Ecology and Environment and local environmental protection bureaus, State Administration for Market Regulation, National Medical Products Administration, and local animal health supervision and inspection stations. In the SEA context, a complex regulatory web is similarly found, with a variety of agencies and actors tasked with implementing and enforcing relevant laws and policies.

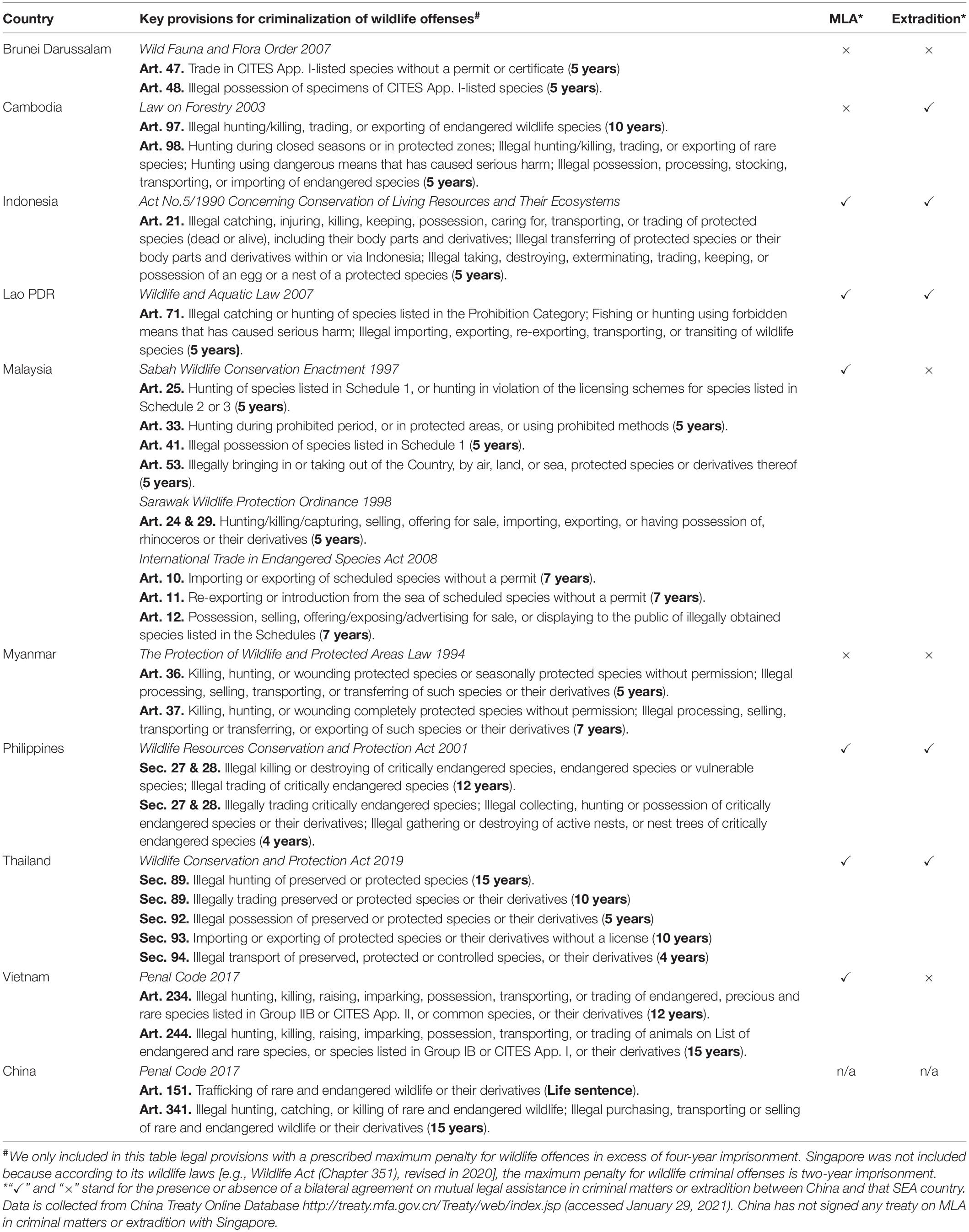

Across the SEA region, domestic legal frameworks that set out the ownership, management rules, offenses and penalties in the wildlife sector come in different forms. For instance, although most SEA countries have adopted wildlife statutes, Cambodia includes wildlife-related provisions in its 2002 Law on Forestry, whereas Vietnam integrates them into ministerial decrees (Table 2). Most SEA countries have, moreover, promulgated an array of administrative and ministerial directives, circulars, and orders to support the implementation of major wildlife legislation, as well as customs laws as a supplementary instrument to regulate the trade of controlled wildlife (Broussard, 2017).

Table 2. Key legal provisions for criminalization of wildlife offenses in China and ASEAN member-states.

Although the consequences of wildlife offenses vary by country, all SEA countries have established regulatory measures pertaining to the killing or hunting, possessing, selling, transporting, importing, and exporting of endangered and protected species, in an effort to police their exploitation and movement nationally and across borders (ASEAN-WEN, 2016). Depending on the gravity of the offense, violations may lead to administrative and/or criminal liability. Indeed, all countries in SEA have introduced—whether in their wildlife laws (e.g., Laos), CITES-enabling laws (e.g., Malaysia), or penal codes (e.g., Vietnam)—key provisions for criminalizing serious wildlife offenses with imprisonment and/or monetary charges (Table 2).

Notably, recent years have witnessed promising developments when it comes to expanding the scope of existing laws and regulations, imposing heavier penalties for wildlife offenses, and adding aggravating conditions such as the involvement of repeat offenders or organized criminal groups. For example, with Vietnam’s amendment of its Penal Code in 2017 (Law No. 12/2017/QH14), the Code saw a 40-fold increase in the level of fines for offenses against endangered and rare species to VND two billion (US$86,480), with the maximum jail term also increasing three-fold to 15 years. In March 2019, Thailand enacted the Wildlife Preservation and Protection Act. Compared to its 1992 predecessor, the new Act formally brings non-native, CITES-listed species under its protection as “controlled species” and markedly increases the maximum term of imprisonment for infractions from four to 15 years (The Law Library of Congress, 2020; Table 2). One year later, Singapore passed a new amendment (Bill No. 15/2020) to its Wild Animals and Birds Act (Chapter 351, 2000). Despite the maximum prison sentence for wildlife offenses remaining low (i.e., two years) even with this amendment, the maximum fine has been raised considerably from the original SG$1,000 (US$750) to SG$50,000 (US$37,500). The regulatory scope has also been further expanded to include invertebrate species that are deemed threatened, dangerous or invasive.

At the regional level, ASEAN and its member-states committed in 2019 to meeting their obligations vis-à-vis the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, which include a call to action for governments to clamp down on environmental crime.2 Alongside its Plan of Action for ASEAN Cooperation on CITES and Wildlife Enforcement (2016–2020), ASEAN has spearheaded some salient multilateral initiatives in this space. Both the ASEAN Working Group on CITES and Wildlife Enforcement (AWG-CITES), and the ASEAN Senior Officials Meeting on Transnational Crime (SOMTC) Working Group on Illicit Trafficking of Wildlife and Timber (WG-ITWT), were established to facilitate information exchange between state authorities and promote interstate cooperation.

The AWG-CITES was created during the 18th Meeting of the ASEAN Senior Officials for Forestry in 2016 by merging the previous ASEAN Wildlife Enforcement Network (ASEAN-WEN) and ASEAN Expert Group on CITES (DENR, 2019). The WG-ITWT was then formed during the 11th ASEAN Ministerial Meeting on Transnational Crime (AMMTC) in September 2017, following its endorsement at the 10th AMMTC earlier in 2015. With the trafficking of wildlife and timber recognized as new areas for transnational crime, the WG-ITWT has served to complement the work of the AWG-CITES in developing a coordinated response to wildlife and timber trafficking. In particular, special attention is directed to strengthening international and regional legal cooperation to crack down on transnational criminal syndicates (ASEAN Secretariat, 2019a). Within this ASEAN operational framework, interagency coordination between ASEAN member-states normally occurs through a national-level, multi-agency taskforce: for instance, the Wildlife Enforcement Network in Thailand and the National Wildlife Management Committee in the Philippines. These taskforces are generally mandated to coordinate law enforcement activities against IWT (ASEAN-WEN, 2016).

But despite the existence of these regional and national coordination networks, a recent assessment of select SEA countries (i.e., Indonesia, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam) suggests that they have played a limited role thus far in helping to foster a coherent interagency and/or inter-governmental response to IWT (OECD, 2019). Indeed, the use of national multi-agency taskforces to coordinate investigations into and the prosecution of IWT cases remains infrequent at best. Due to a confluence of factors, including high coordination costs, inadequate expertise, and conflicting enforcement priorities, limited information has been exchanged between these national agencies (World Bank, 2016; OECD, 2019). Moreover, the AWG-CITES and its primary interlocutor—that is, the national-level CITES management authorities—continue to lack the capacity and resources to coordinate complex investigations (e.g., joint multi-national investigations or controlled deliveries) into wildlife trafficking, especially those involving transnational organized criminal groups. As a result, IWT cases with a transnational scope do not usually yield successful upstream or downstream investigations.

Furthermore, despite the involvement of anti-corruption and financial intelligence units in the multi-agency taskforces of several SEA countries (e.g., Indonesia, Thailand), investigations into the corruption and illicit financial transactions involved in IWT have rarely been conducted in the region. According to the OECD (2019), the main barriers to the uptake of anti-corruption and “follow-the-money” approaches to IWT can stem from how, for instance, IWT does not feature as a sufficiently high-level, policy priority; the penalty for IWT does not meet the minimum threshold for triggering investigations into alleged corruption; or there is a dearth of expertise, capacity, resources, and political will to undertake parallel financial investigations into IWT-related activities.

Consequently, successful prosecutions continue to be formed primarily on the basis of there being evidence of a wildlife trafficking offense, with evidence for convictions also dependent on the ability of authorities to catch criminals in the act (OECD, 2019). This is not to mention the potential issue of institutional overlap, where the de facto intersection of agencies’ mandates may result in contradictory, duplicative or obstructive policies. To avoid this problem, the WG-ITWT’s work domain needs to be suitably distinct from that of the AWG-CITES in order to enhance their complementarity and reduce overlap (Broussard, 2017).

China has a complex regulatory system in place for the protection and management of endangered and threatened species as well as their habitats. This system is comprised of three main tiers of legal instruments: (1) national laws and regulations enacted by the National People’s Committee, the State Council and its ministerial affiliates (e.g., NFGA); (2) local laws and regulations promulgated by provincial and other local-level legislative bodies and governments; and (3) legislative and judiciary interpretations and opinions released by the Standing Committee of the National People’s Committee, the Supreme People’s Court, and the Supreme People’s Procuratorate (Cao, 2015, 2016).

The Wildlife Protection Law of 1989 (WPL; revised in 2016) serves as the backbone of China’s wildlife governance framework. It sets out the fundamental mechanisms for the conservation of wildlife species and their habitats, administration of wildlife resource utilization, and the administrative liability and penalties for violations. While the WPL prohibits the hunting, catching, sale, and purchase of protected species and their products (including those species in the Special State Protection List and in CITES Appendix I and II), it does allow for exemptions pertaining to the utilization of protected species for a specified range of purposes (e.g., scientific research, captive breeding, epidemic monitoring, public exhibition, heritage conservation, or other special purposes). But to ensure that such exempted uses and trades are monitored and do not adversely impact the survival of wild populations, the WPL establishes various regulatory schemes such as business registration, quotas control, licensing, and special marking. Infringement of these prohibitive or restrictive measures can result in administrative sanctions, including the confiscation of wildlife contraband and illegal proceeds, license revocation, and fines of up to ten times the contraband’s market value (e.g., WPL, Article 48). Acts causing serious harm are also considered criminal offenses under Articles 151 (wildlife trafficking), 340 (illegal fishing) and 341 (illegal hunting, catching, killing, purchasing, transporting, or selling) of the Penal Code. Criminal penalties may range from fines or property forfeiture, to fixed-termed imprisonment and a life sentence (Table 2).

In terms of domestic policy coordination, new interagency platforms have been created at both the central and local levels in recent years to strengthen the capacity of Chinese wildlife law enforcement officers. In December 2011, the National Interagency CITES Enforcement Coordination Group (NICE-CG) was established as a liaison mechanism to enhance the coordination among responsible government authorities in implementing CITES (NFGA, 2011). The NICE-CG consists of 12 departments from nine ministries, including the Department of Customs Control and Inspection, among others. The Department of Wildlife Conservation, which also hosts China’s CITES Management Authority, acts as its coordinating body. Since its initiation, the NICE-CG has convened six annual joint meetings, through which representatives from member agencies are brought together to discuss and identify priority areas for CITES implementation, opportunities for multi-departmental joint law enforcement operations, and training programs for capacity-building (State Council, 2016). By December 2013, all 31 provinces (including municipal cities and autonomous regions) had established their own interagency CITES enforcement coordinating offices (CITES Secretariat, 2018).

In November 2016, another high-level interagency coordination platform—the Inter-ministerial Joint Meeting (IJM) on Combating Illegal Wildlife Trade—was formed with the approval of the State Council (NFGA, 2017). As of July 2020, some 27 ministerial departments are listed as members, with the NFGA designated as the coordinating agency. Joint meetings are held annually to analyze evolving trends in the illegal wildlife trade, review progress made and the major challenges faced by wildlife law enforcement, and set out the key tasks of each member agency (NFGA, 2019). Notably, in July 2020, policy priorities identified during the 3rd Inter-ministerial Joint Meeting included, inter alia, enforcing the decision passed by the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress on the total ban on consuming terrestrial wildlife as food (including both wild-caught and captive-bred sources); strengthening the monitoring and tracking of the online sale of illegal wildlife; and building a national platform for public reporting of wildlife offenses (NFGA, 2020). In this way, the IJM platform constitutes an enhanced version of the NICE-CG, one that covers a broader range of IWT issues and features a greater number of participating agencies that have high institutional rank.

This decentralized assemblage of biodiversity legislation and related policy actors notwithstanding, significant implementation and enforcement challenges remain within the Chinese regulatory system. A number of factors can be attributed to this state of affairs. For instance, despite efforts to mainstream and integrate environmental concepts such as “ecological civilization” (Shengtai Wenming) into policy practice, the Chinese government continues to prioritize economic values over ecological ones. Especially with the COVID-19 pandemic, economic recovery has yet again become the foremost policy preoccupation for the Chinese leadership. This may be further exacerbated by the “two-masters dilemma,” whereby local forestry and environmental protection departments are often accountable less to their central ministries and more to the local governors who decide on their budget and staffing needs—and who traditionally care more about local economic growth targets than environmental sustainability (Li, 2007). This creates perverse environmental incentives on two levels: first, it has meant that the above-mentioned Wildlife Protection Law, as a pivotal piece of biodiversity legislation, is more concerned with the “rarity, particularity, and economic value” of a species as opposed to its value to the ecosystem (Yu and Czarnezki, 2013). Second, by focusing on the economic value of species, this arguably encourages a neoliberal outlook that treats the wildlife trade as a lucrative revenue source for the state and other non-state actors.

Aside from bureaucratic rivalry (the Ministry of Ecology and Environment is known for being one of the country’s weaker ministries), funding shortages, and a lack of qualified personnel (Li, 2007; Wang and McBeath, 2017), concerns have also been raised over the vague language used in Chinese laws (McBeath et al., 2006). This results in not only unclear lines of authority, but equally unclear guidelines for how these laws are to be interpreted and implemented at the national and provincial levels. A notable example is the problematic interpretation of the term “other special purposes,” which has allowed for the commercial farming and trade of protected species since the early 1990s (Sun, 2016).

As previously mentioned, alongside other exempted purposes, the WPL (both 1989 and 2016 versions) contains a licensable category for the utilization of state protected species stipulated as “other special purposes.” But while this category should have in principle excluded any utilization for “economic purposes,” as wildlife farming for economic purposes could have negative impacts on species conservation given the lack of means to distinguish between captive-bred and wild-caught specimens (Tensen, 2016), its inclusion has given rise to adverse unintended consequences. By inscribing economic purposes into the licensable scope, the 1991 Measures for the Management of Licensing for Domestication and Captive Breeding of Wildlife under Special State Protection—an NFGA-promulgated regulation for implementing the WPL that is still in effect today—had opened up a backdoor to the commercial farming of protected species and trade in farmed specimens. It is in this way that greater harmonization of Chinese domestic laws with the global legal and policy language, as reflected in UNTOC, could assist with enhancing China’s domestic enforcement as well as creating a more solid basis for regional cooperation.

Cooperation between China and SEA countries on environmental protection and non-traditional security issues has expanded considerably and become more formalized since 2002. Particularly in the areas of CITES implementation and combating wildlife trafficking, China has noticeably become more proactive in its cooperation with SEA countries over time. This has resulted in the establishment of bilateral and multilateral agreements, hosting of regional fora, organization of workshops and training sessions, as well as participation in transnational law enforcement operations. The effectiveness, and limitations of each of these mechanisms are discussed below.

China and ASEAN’s deepened cooperation on IWT and transnational crime has been pursued through a variety of institutional mechanisms and platforms that supplement the “ASEAN Plus China” arrangement. These include, for instance, the ASEAN Plus Three (APT) mechanism, which includes China, Japan and South Korea, and the East Asia Summit. Especially since the creation of the ASEAN-WEN in December 2005, several multilateral agreements and joint statements that directly target wildlife trafficking, or which acknowledge it as a major transnational crime threat within the region, have been signed between China and ASEAN. Notably, in November 2014, 18 countries—including China and ASEAN member-states—adopted the “Declaration on Combating Wildlife Trafficking” at the 9th East Asia Summit in Nay Pyi Taw. The Declaration recognized the severe and multifaceted repercussions caused by the illicit trade of wild fauna and flora, as well as the imperative need for a competent interagency response. Participating countries had then agreed to take action through, inter alia, regular dialogs, harmonization of relevant laws to support evidence exchange and criminal prosecution, and development of national interagency taskforces to strengthen interstate cooperation among source, transit and destination countries (CITES Secretariat, 2014).

Within the ASEAN Plus China and APT frameworks, cooperation on transnational crime issues (which includes wildlife trafficking) is largely conducted through the annual consultations held between the ASEAN Ministerial Meeting on Transnational Crime and China (AMMTC + China) and the Plus Three format (AMMTC + 3), as well as through affiliated Senior Officials Meeting on Transnational Crime. Work plans are developed every five years to serve as a principal guide for priority action areas. In September 2017, at the 5th AMMTC + China Consultation, China and ASEAN renewed their “Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) on Cooperation in the Field of Non-traditional Security Issues.” As part of this agreement, both sides committed to developing practical measures to strengthen national and regional capacities for dealing with different types of transnational crime. These measures included sharing information on relevant legislative frameworks, intelligence sharing, personal exchange and training, as well as cooperation in such areas as evidence gathering, tracing of criminal proceeds, and the apprehension and investigation of criminal fugitives (ASEAN Secretariat, 2017).

Although the illegal wildlife trade was not explicitly listed among the transnational crime types prioritized in this MOU, inroads have since been made to incorporate wildlife trafficking into the purview of the AMMTC + 3. Adopted at the 18th APT Foreign Ministers Meeting in August 2017, the “APT Cooperation Work Plan (2018–2022),” for one, stressed the need to expand and deepen cooperation to address emerging forms of transnational crime, including trafficking of wildlife and timber (ASEAN Secretariat, 2018). In November 2019, at the 10th AMMTC + 3, the delegates reaffirmed their commitment to strengthen APT cooperation to prevent and combat transnational crime as articulated in the APT Cooperation Work Plan (ASEAN Secretariat, 2019b).

China has been providing substantial logistical support for capacity-building activities at the regional level—on occasion at the behest of SEA governments—through the organization and hosting of multilateral fora, workshops, and trainings with SEA countries. Although it is difficult to fully gauge the effectiveness of these efforts—building capacity is usually incremental and requires a longer timeframe—the fact that China has taken the lead in many of these initiatives is noteworthy in itself. Back in July 2012, for instance, China hosted the inaugural technical consultation meeting between NICE-CG and ASEAN-WEN in Nanning, Guangxi Province. Over 60 law enforcement officers from China and ASEAN member-states, as well as representatives from international organizations, were present to discuss pathways to enhance collaboration between the two largest wildlife enforcement networks in Asia. Recommended joint activities included information-sharing, public awareness-raising, and demand reduction (TRAFFIC, 2012).

Another example of collaboration took place in April 2016, when China’s CITES Management Authority co-hosted a field mission with its Vietnamese counterpart and Laos’ Department of Forest Inspection. The trip had frontline enforcement officers from the three countries visiting TCM markets and border ports that were believed to be key staging points in the region’s main wildlife trafficking routes. The mission was intended to improve on-the-ground understanding of wildlife trafficking, exchange enforcement experiences, build relationships and encourage future cooperation by establishing direct communication protocols among the law enforcement agencies in the three countries’ border provinces (WCS, 2016). This was then followed up with China-Lao and China-Vietnam training seminars, which focused on improving the direct contact mechanism for border enforcement agencies. Crucially, these exchanges would result in agreements to develop pilot communication schemes between the prefectural forestry police in Xishuangbanna and forestry inspection departments in Laos’ northern provinces (TRAFFIC, 2016), as well as between the Chinese anti-smuggling office and forest police in Guangxi and their counterparts in adjoining Vietnamese provinces (NFGA, 2016).

2016 is thus an important year for regional cooperation. In the same year, the China-ASEAN Forestry Cooperation Forum was launched during the 13th China-ASEAN Exposition in Nanning. The forum adopted the “Nanning Proposal for China-ASEAN Forestry Cooperation,” which identified five priority areas of cooperation, with the fourth being the conservation of wild flora and fauna and prevention of transboundary wildlife trafficking (Zhang, 2016). The momentum continued with the fourth Regional Dialogue on Combating Trafficking of Wild Fauna and Flora in 2017, which expanded upon three preceding dialogs on preventing the illegal logging and trading of Siamese rosewood. China pledged to join up with ASEAN, through offering training support, in regional efforts to curb the illegal wildlife trade (CITES Secretariat, 2017c).

These developments paved the way for the “Plan of Action for Nanning Proposal (2018–2020),” which was formally endorsed at the 21st ASEAN Senior Officials Meeting on Forestry in August 2018 (NFGA, 2018). As part of efforts to implement the Nanning Proposal, the China-ASEAN Wildlife Conservation Workshop was held in Sichuan, with some 20 participants from ASEAN member-states attending the training sessions and exchanging details on their respective wildlife laws as well as practices for controlling IWT (Eaaflyway, 2018).

Considering the large number of seizures and arrests made by Chinese law enforcement each year, China’s track record in cracking down on wildlife offenses domestically and intercepting illegal shipments at national borders appears consistent and promising. For example, official data reveals how between 2007 and 2016, Chinese forest police had handled a national total of 246,000 forest and wildlife-related criminal cases and two million administrative cases, leading to the apprehension of 3.9 million offenders and confiscation of 57.6 million animal individuals (NFGA, 2008–2017). Crucially, since 2010, China’s wildlife enforcement units, including the CITES Management Authority, forest police and customs, have actively participated in a series of regional and international law enforcement operations with ASEAN-WEN and individual SEA countries. These joint operations have yielded significant seizures of illegal wildlife products and led to the detainment of hundreds of wildlife criminals. The most notable were “Operations Cobra I, II and III.” Taking place between 2013 and 2015, the series was aimed at dismantling organized wildlife trafficking syndicates. Over the course of these operations, China played a leading role in proposing and co-organizing cross-continental crackdowns, sending its elite officers abroad to join international coordination teams to facilitate intelligence-sharing, as well as coordinating and conducting follow-up investigations and prosecutions (WCO, 2013, 2014; CITES Secretariat, 2015). Operation Cobra II, carried out between the end of 2013 and early 2014, also saw the first-ever, China-Africa sting operation, which resulted in the eradication of a major ivory trafficking racket and the extradition of a Chinese national from Kenya to China (WCO, 2014). However, as discussed below, the momentum from these joint operations is yet to be adequately built upon at the regional level in SEA.

Even though China and SEA countries have clearly taken considerable steps to boost their domestic interagency responses and regional engagement to tackle wildlife trafficking, especially in the last decade, cooperation among them on IWT remains limited in both scope and effectiveness. Despite the high-level commitment from both sides to ending wildlife trafficking, political will is yet to translate into a sustained and systematic course of action, with efforts largely concentrated in the policy and capacity-building domains. Current progress appears to have stagnated, for example, at the stage of exploring possible roadmaps for a communication mechanism between frontier wildlife law enforcement agencies in China and its SEA neighbors. Furthermore, China’s abiding interest would seem to lie more with releasing policy agreements with ASEAN, hosting conferences and training workshops—that is, regional confidence-building measures. China’s leadership in these areas—whilst pivotal to advancing its partnership with the ASEAN community—thus remains disproportionate to its prominent role as the region’s largest end-user market of illicit wildlife products. This begs the question: how can China step up its leadership in this area and translate its regional institution-building efforts into a more impactful approach to dealing with IWT?

Greater traction is needed with regard to joint law enforcement operations and legal cooperation, more broadly, given how difficulties in investigating and prosecuting offenders in overseas jurisdictions continue to undermine efforts by the region’s governments to combat wildlife trafficking. As revealed by court verdicts on criminal cases of wildlife trafficking,3 an oft-seen practice of wildlife trafficking from SEA to China is one where organized criminal groups and offenders based in SEA countries (e.g., Vietnam)—some of whom may be Chinese immigrants or businessmen with contacts back in China (ACET, 2019; van Uhm and Wong, 2019)—would use Chinese social media (e.g., WeChat) to reach out to potential Chinese buyers. Once an order is received, they will prepare the illegal goods and arrange skilled smugglers to move the goods in circumvention of customs border checkpoints to designated places in Chinese border cities (e.g., Nanning). Contracted Chinese intermediaries are then either paid to handle the domestic transfer to buyers, or will buy up the goods and manage the sale themselves. In many of these cases, only the easily replaceable Chinese transporters and vendors are at risk of getting caught, whereas the ringleaders and criminal syndicates stationed in SEA countries are more likely to remain at large, perpetuating these supply chains.

Cooperation to fight IWT will necessarily have policy, regulatory and operational dimensions, and can take place at all points along an illegal chain of custody from prevention, interdiction to prosecution (Elliott, 2017). Disrupting illicit supply chains, therefore, requires that major countries of supply, transit and demand collaborate to dismantle the criminal networks that operate these supply chains across borders. In this section, UNTOC is leveraged as a framework for deepening China-SEA legal cooperation—and one that also suggests the utility of international legal instruments to combating transnational wildlife trafficking.

At present, the international legal regime for addressing IWT is fragmented. Although a substantial body of treaties, agreements, and declarations has emerged since the 1970s to better protect the environment and endangered wildlife (Trouwborst et al., 2017), none of them contain specific measures for the prevention and suppression of wildlife trafficking (Elliott, 2017). Existing international rules, obligations, and principles relevant to wildlife trafficking have arisen from multiple areas of international law, including international trade, environmental protection and conservation, organized crime and corruption, and animal welfare (UNODC, 2012; Slobodian, 2014; Lelliott, 2020). UNTOC is one such instrument that offers provisions applicable to tackling IWT. Indeed, in the Resolution under which UNTOC was adopted, the UN General Assembly affirmed how the Convention constitutes “an effective tool and the necessary legal framework for international cooperation” to fight the trafficking of endangered species of wild fauna and flora and other criminal activities (UN General Assembly, 2000).

In addition to the seven specific offenses stipulated by UNTOC and its three attached Protocols, the Convention also applies broadly to serious crimes committed by a transnational organized criminal group (Article 3.1).4 According to the Convention, “serious crime” refers to an offense that is punishable in domestic law by “a maximum deprivation of liberty of at least four years or a more serious penalty” [Article 2(b)]. A crime is “transnational” when it is committed or prepared in more than one state, or committed in one state but involves criminal groups operating in other states, or causes substantial transboundary consequences (Article 3.2). “Organized criminal group” refers to a structured group of three or more people working in concert over a period of time to commit serious crimes for financial or material benefits [Article 2(a)]. Such structured groups do not need to have “formally defined roles for its members, continuity of its membership or a developed structure” [Article 2(c)]. As such, the Convention adopts a broad definition of organized criminal group, covering both loose networks of individuals connected by trade relationships or contracts, and highly integrated groups with more formal hierarchies and stable memberships (Boister, 2016; UNODC, 2016).

In many cases, wildlife trafficking between SEA and China would fall within UNTOC’s remit for three main reasons. First, China and all ASEAN member-states are parties to the Convention; and except for Singapore, all countries have written into their domestic legislation a maximum prison penalty in excess of four or more years for wildlife trafficking (Table 2). This fact constitutes an important precondition for invoking UNTOC provisions. Second, SEA-China wildlife trafficking involves the illegal acquisition and movement across borders of wildlife products, which can cause far-reaching and adverse impacts on biodiversity, public health (i.e., zoonotic infectious diseases), and regional security. Third, while actors involved in IWT supply chains vary considerably in type (e.g., opportunistic, professional), numbers, and with the structures of the network within which they operate also subject to change depending on the species being traded or the presence of a legal market (Phelps et al., 2016; ‘t Sas-Rolfes et al., 2019), organized crime elements are known to have penetrated many transboundary wildlife trafficking operations (van Uhm, 2016; van Uhm and Nijman, 2020). More importantly, as noted above, UNTOC’s conceptualization of an organized criminal group lends itself to a flexible definition that encompasses organized and corporate criminal groups that exhibit a high degree of organization and continuity, but also “disorganized criminal networks” made up of opportunistic individuals (e.g., harvesters, processors, intermediaries, smugglers, vendors, launderers) who are connected by fluid relationships of illegality (Wyatt et al., 2020). Against this definition, modern-day wildlife trafficking networks would qualify as organized criminal groups (Strydom, 2016; UNODC, 2020b).

The United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime is thus highly applicable as a practical framework for tackling the illegal wildlife trade between SEA and China, especially with respect to overcoming the difficulties in investigating and prosecuting upstream perpetrators located in source and transit countries. Given China’s striking track record in seizures and arrests (NFGA, 2008–2017), it is critical that China promptly and regularly shares intelligence (e.g., records of electronic communication and financial transactions) with law enforcement authorities in source and transit countries, in order to facilitate investigative efforts at following financial and other evidence trails for the prosecution of upstream offenders and organized crime groups in IWT supply chains. It is in this regard that UNTOC offers a host of tools that China and SEA could employ to bolster their cooperation in criminal justice and law enforcement to disrupt and dismantle IWT. These tools include general law enforcement cooperation and exchange of information (Article 27, 28); joint investigations (Article 19) and the use of special investigative techniques (e.g., controlled deliveries, electronic surveillance, undercover operations) (Article 20); international cooperation in confiscation (Article 13); formal mutual legal assistance (MLA) (Article 18) and extradition (Article 16). Certainly, the prompt sharing of information about the smuggling routes, concealment methods and false identities used by criminal groups is what renders early interception and seizure of illegal shipments possible.

The appropriate use of controlled deliveries can, moreover, help to track the route of trafficked wildlife to identify role players and ultimate beneficiaries connected with the criminal activities (INTERPOL and CITES, 2007). MLA in criminal matters also allows for the reciprocal provision of assistance in the servicing of judicial documents and gathering of admissible evidence for use in court cases. With respect to extradition, extraditing wildlife offenders from SEA to China for trial could, in principle, produce a stronger deterrent effect given how China currently has the harshest penalty for wildlife trafficking (i.e., life sentencing). Of course, any extradition agreement requires not only a deep level of legal cooperation but also mutual trust between the countries involved. In practice, agreeing on extradition terms between Southeast Asian governments and China is thus likely to be less than straightforward. However, even if a requested state were to refuse the extradition of an alleged offender to China (i.e., on the grounds that the offender is a national of their country), the request itself could still serve to reinforce the state’s obligation under UNTOC [Art. 16(10)] to refer the case to competent authorities to initiate an investigation and, if applicable, prosecution of the alleged offender.

At the fifth Session of the Conference of the Parties to the UNTOC in 2010, UNODC’s former Executive Director Yury Fedotov had expressed concern over how the Convention was used by only 12% of its member-states to ground international cooperation to fight organized criminal groups.5 Owing to the lack of a review mechanism and the limited application of UNTOC to tackling IWT, limited evidence currently exists on how effective UNTOC is (Boister, 2016). Despite repeated calls to bring wildlife trafficking that involves transnational organized criminal groups within UNTOC’s remit (e.g., UNESC, 2013; UN General Assembly, 2015; UNEP, 2016), the Convention remains underutilized (UNODC, 2020b). This is reflected in the low level of international cooperation on MLA and extradition in relation to wildlife trafficking. For example, Malaysia received only three MLA requests from foreign countries and had no outgoing requests during 2015–2016 (UNODC, 2017a). There has also been no reported use of MLA treaties or controlled deliveries in cross-border investigations to prosecute wildlife trafficking in Indonesia, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam (OECD, 2019). Moreover, certain SEA countries (e.g., Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar) have challenged the legitimacy of UNTOC as a legal basis for international cooperation on extradition (UNODC, 2008). As for China, MLA requests issued by the Ministry of Justice have increased only slightly from eight in 2011 (MOJ, 2012) to 24 in 2017 (Statista, 2020).

Although there is yet to be a systematic review of the challenges that constrain the use and utility of UNTOC vis-à-vis SEA-China legal cooperation on IWT, this paper posits that obstacles are likely to include: limited resources, weak rule of law in relevant countries, government corruption (Elliott, 2017), a lack of suitable guidelines and protocols for the content and scale of cooperation (UNODC, 2017b), gaps in the coverage of nationally protected species that result in the priotitization of indigenous species protection (Broussard, 2017), as well as discrepancies in the definition of “organized crime groups” and the penalty threshold for serious crimes. Indeed, it warrants note how the legal definition of organized criminal group still varies considerably between SEA countries and China, specifically in terms of the threshold for the minimum number of group members and minimum prison terms. For instance, Malaysia’s Penal Code 2013 defines organized criminal group as a group consisting of two or more people for the commission of offenses carrying imprisonment of at least ten years (Article 130u), whereas Singapore and Thailand employ a definition that is more in line with UNTOC. In contrast, China refutes the presence of typical organized criminal groups within its territory. Instead, its Penal Code 2017 (Article 294) develops a new concept termed “organizations with underworld characteristics” to describe criminal organizations that have a relatively large number of gang members with clearly defined roles (e.g., organizers, leaders, core group members), and which pursue economic gains through the repeated commission of organized crimes or other illegal activities with violence, threats or other means (Chin and Godson, 2006; Cai, 2017).

Tackling the SEA-China illegal wildlife trade undoubtedly necessitates a concerted effort among the major centers of supply, demand and trade involved in global wildlife trafficking (Esmail et al., 2020). Considering the scale, complexity, and severity of the IWT problem in Asia, a multifaceted response is required of the Chinese and SEA governments—individually and collectively. In this way, it is not sufficient to focus only on tackling market demand for contraband wildlife products or cracking down on illegal smuggling rings. Here, the chief objective of any coordinated, interstate effort within the IWT domain should also be to disrupt and dismantle the criminal networks that underpin the cross-border supply and trade of protected wildlife. Following this, the paper argues that China and the ASEAN community should seek to leverage the cooperation outlets offered by UNTOC and use these to supplement existing bilateral and multilateral arrangements. More specifically, it posits two specific areas wherein China and its SEA neighbors could focus on to improve their legal cooperation.

First, China should proactively act in accordance with UNTOC [e.g., Article 18(4), (5)] to share with SEA countries information critical to combating IWT, even when the data has not been explicitly requested. For rapid and secure data-sharing, the use of systems such as CENcomm,6 developed by the World Customs Organization, could be promoted among customs authorities, while the creation of direct cross-border communication mechanisms between other frontline operational units should also be prioritized. Second, the harmonization of domestic criminal laws and procedures across countries and in line with UNTOC should be undertaken, specifically with respect to the definition of what constitutes an organized criminal group and the penalty threshold for serious environmental crimes. Third, beyond UNTOC, it is crucial that China, individual SEA countries and ASEAN as a whole continue to advance bilateral and multilateral agreements for MLA, extradition (which presently exists between China and only half of SEA countries; Table 2), and other forms of legal cooperation. Here, bilateral agreements that address wildlife offenses whose maximum penalty imposes less than four-year imprisonment could serve to supplement UNTOC provisions that apply to serious crimes only. Equally important is for these countries to work together to develop detailed guidance on how such legal cooperation is to happen, with national contact officers clearly designated and law enforcement procedures streamlined.

With the COVID-19 pandemic having raised awareness and concern across the region about the health security implications of possible zoonotic diseases, transnational cooperation to help strengthen local interagency coordination and the rule of law in China and Southeast Asia is imperative to dismantling the illegal wildlife trade—as well as to protecting the region’s imperiled biodiversity.

YJ and PY did the data collection, analysis, and writing. All authors did the study design and manuscript revisions and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

This work was supported by research grants from Sun Yat-sen University (20wkpy08) to YJ, from the National Talent Research Program in China (grant nos. 41180944 and 41180953) and the European Commission Grant ENV/2018/160130/2 to TL, and from the Australian Research Council (DE180100603) to PY.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We thank Sarah Wilson for helping us with data compilation, and three reviewers for their constructive feedback.

‘t Sas-Rolfes, M., Challender, D. W. S., Hinsley, A., Veríssimo, D., and Milner-Gulland, E. J. (2019). Illegal wildlife trade: scale, processes, and governance. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 44, 201–228. doi: 10.1146/annurev-environ-101718-033253

ACET (2019). Illegal wildlife trade in Southeast Asia: evolution, trajectory and how to stop it. Green Lake: ACET.

ASEAN Secretariat (2017). Memorandum of Understanding between ASEAN and the Government of the Republic of China in the Field of Non-traditional Security Issues. Jakarta: ASEAN.

ASEAN Secretariat (2019a). Terms of Reference of the ASEAN Senior Meeting on Transnational Crime Working Group on Illicit Trafficking of Wildlife and Timber (SOMTC WG on ITWT). Jakarta: ASEAN.

ASEAN Secretariat (2019b). Joint Statement the 10th ASEAN Plus Three Ministerial Meeting on Transnational Crime (10th AMMTC + 3) Consultation. Jakarta: ASEAN.

ASEAN-WEN (2016). ASEAN handbook on legal cooperation to combat wildlife crime. Bangkok: Freeland Foundation.

Boister, N. (2016). “The UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime 2000,” in International law and transnational organized crime, eds P. Hauck and S. Peterke (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 126–148.

Brook, S. M., Dudley, N., Mahood, S. P., Polet, G., Williams, A. C., Duckworth, J. W., et al. (2014). Lessons learned from the loss of a flagship: the extinction of the Javan rhinoceros Rhinoceros sondaicus annamiticus from Vietnam. Biol. Conserv. 174, 21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2014.03.014

Broussard, G. (2017). Building an effective criminal justice response to wildlife trafficking: Experiences from the ASEAN region. Rev. Eur. Comparat. Int. Environ. Law 26, 118–127. doi: 10.1111/reel.12203

Cai, J. (2017). Retrospect, reflection and prospect of China’s organized crime criminal law legislation. J. Henan Univers. 6, 21–27. doi: 10.15991/j.cnki.411028.2017.06.004

Cao, D. (2016). “Wildlife crimes and legal protection of wildlife in China,” in Animal Law and Welfare-International Perspectives, eds D. Cao and S. White (Cham: Springer), 263–278.

Challender, D., Baillie, J., Ades, G., Kaspal, P., Chan, B., Khatiwada, A., et al. (2014). Manis pentadactyla. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2014: e.T12764A45222544. Gland: IUCN.

Chin, K. L., and Godson, R. (2006). Organized crime and the political-criminal nexus in China. Trends Organized Crime 9, 5–44. doi: 10.1007/s12117-006-1001-z

CITES Secretariat (2014). East Asia Summit adopts Declaration on Combating Wildlife Trafficking. Geneva: CITES.

CITES Secretariat (2015). Successful operation highlights growing international cooperation to combat wildlife crime. Geneva: CITES.

CITES Secretariat (2017a). Application of Article XIII in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic. SC69 Doc. 29.2.1. Geneva: CITES.

CITES Secretariat (2017b). Status of elephant populations, levels of illegal killing and the trade in ivory: a report to the CITES Standing Committee. SC69 Doc. 51.1. Geneva: CITES.

CITES Secretariat (2017c). CITES Secretary-General’s remarks at the 4th Regional Dialogue on Combating Trafficking in Wild Fauna and Flora, Bangkok, Thailand. Geneva: CITES.

CITES Secretariat (2018). Review report on the implementation of China’s illegal ivory law enforcement and the National Ivory Action Plan. SC70 Doc. 27.4 Annex 7. Geneva: CITES.

Davis, E. O., Glikman, J. A., Crudge, B., Dang, V., Willemsen, M., Nguyen, T., et al. (2019). Consumer demand and traditional medicine prescription of bear products in Vietnam. Biol. Conserv. 235, 119–127. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2019.04.003

DENR (2019). ASEAN Working Group on CITES and Wildlife Enforcement (AWG-CITES & WE). Quezon City: DENR.

Doak, N. (2014). Polishing off the Ivory Trade: Surveys of Thailand’s Ivory Market. Cambridge: TRAFFIC International.

EIA (2015). Sin city: illegal wildlife trade in Lao’s Golden Triangle Special Economic Zone. Washington, DC: EIA.

Elliott, L. (2017). Cooperation on transnational environmental crime: Institutional complexity matters. Rev. Eur. Comparat. Int. Environ. Law 26, 107–117. doi: 10.1111/reel.12202

Esmail, N., Wintle, B. C., t Sas-Rolfes, M., Athanas, A., Beale, C. M., Bending, Z., et al. (2020). Emerging illegal wildlife trade issues: a global horizon scan. Conserv. Lett. 13:e12715. doi: 10.1111/conl.12715

Felbab-Brown, V. (2011). The disappearing act: the illicit trade in wildlife in Asia. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Foster, S. J., Kuo, T. C., Wan, A. K. Y., and Vincent, A. C. J. (2019). Global seahorse trade defies export bans under CITES action and national legislation. Mar. Policy 103, 33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2019.01.014

Foster, S. J., Wiswedel, S., and Vincent, A. (2016). Opportunities and challenges for analysis of wildlife trade using CITES data – seahorses as a case study. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 26, 154–172. doi: 10.1002/aqc.2493

Gomez, L., Leupen, B. T., and Heinrich, S. (2016). Observations of the illegal pangolin trade in Lao PDR. Malaysia: TRAFFIC Southeast Asia.

Grieser-Johns, A., and Thomson, J. (2005). Going, going, gone: the illegal trade in wildlife in East and Southeast Asia. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Harfoot, M., Glaser, S. A. M., Tittensor, D. P., Britten, G. L., McLardy, C., Malsch, K., et al. (2018). Unveiling the patterns and trends in 40 years of global trade in CITES-listed wildlife. Biol. Conserv. 223, 47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2018.04.017

Harrison, R. D., Sreekar, R., Brodie, J. F., Brook, S., Luskin, M., O’kelly, H., et al. (2016). Impacts of hunting on tropical forests in Southeast Asia. Conserv. Biol. 30, 972–981. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12785

Heinrich, S., Wittmann, T. A., Prowse, T. A., Ross, J. V., Delean, S., Shepherd, C. R., et al. (2016). Where did all the pangolins go? International CITES trade in pangolin species. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 8, 241–253. doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2016.09.007

Hughes, A. C. (2017). Understanding the drivers of Southeast Asian biodiversity loss. Ecosphere 8:e01624. doi: 10.1002/ecs2.1624

INTERPOL and CITES (2007). Controlled deliveries: a technique for investigating wildlife crime. Lyon: INTERPOL.

Jiao, Y. B., and Lee, T. M. (in press). The global magnitude and implications of China’s legal and illegal wildlife trade. Oryx.

Krishnasamy, K., and Zavagli, M. (2020). Southeast Asia: at the heart of wildlife trade. Malaysia: Southeast Asia Regional Office.

Krishnasamy, K., Shepherd, C. R., and Or, O. C. (2018). Observations of illegal wildlife trade in Boten, a Chinese border town within a Specific Economic Zone in northern Lao PDR. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 14:e00390. doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2018.e00390

Lelliott, J. (2020). “International law relating to wildlife trafficking: An overview,” in Wildlife trafficking: the illicit trade in wildlife, animal parts, and derivatives, eds G. Ege, A. Schloenhardt, and C. Schwarzenegger (Berlin: Carl Grossmann Publishers), 125–148.

Li, P. J. (2007). Enforcing wildlife protection in China: the legislative and political solutions. China Informat. 21, 71–107. doi: 10.1177/0920203X07075082

Li, Y. B., Wei, Z. Y., Zou, Y., Fan, D. Y., and Xie, J. F. (2010). Survey of illegal smuggles of wildlife in Guangxi. Chin. J. Wildlife 31, 280–284.

Li, Y. M., and Li, D. M. (1998). The dynamics of trade in live wildlife across the Guangxi border between China and Vietnam during 1993–1996 and its control strategies. Biodivers. Conserv. 7, 895–914. doi: 10.1023/A:1008873119651

Li, Y. M., Gao, Z. X., Li, X. H., Wang, S., and Niemelä, J. (2000). Illegal wildlife trade in the Himalayan region of China. Biodiver. Conserv. 7, 901–918. doi: 10.1023/A:1008905430813

Lynam, A. J. (2010). Securing a future for wild Indochinese tigers: transforming tiger vacuums into tiger source sites. Integrat. Zool. 5, 324–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4877.2010.00220.x

Lyons, J. A., and Natusch, D. J. D. (2011). Wildlife laundering through breeding farms: illegal harvest, population declines and a means of regulating the trade of green pythons (Morelia viridis) from Indonesia. Biol. Conserv. 12, 3073–3081. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2011.10.002

McBeath, J., and Huang McBeath, J. (2006). Biodiversity Conservation in China: Policies and Practice. J. Int. Wildlife Law Policy 4, 293–317. doi: 10.1080/13880290601039238

Mohapatra, R. K., Panda, S., Acharjyo, L. N., Nair, M. V., and Challender, D. W. (2015). A note on the illegal trade and use of pangolin body parts in India. TRAFFIC Bull. 27, 33–40.

MOJ (2012). The Ministry of Justice handled 251 requests for mutual legal assistance last year. Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Justice.

Natusch, D. J. D., and Lyons, J. A. (2012). Exploited for pets: the harvest and trade of amphibians and reptiles from Indonesian New Guinea. Biodivers. Conservat. 21, 2899–2911. doi: 10.1007/s10531-012-0345-8

NFGA (2008). Survey of Key Terrestrial Wildlife Resources in China. Beijing: China Forestry Publishing House.

NFGA (2011). National Interagency CITES Enforcement Coordination Group was formally established. Beijing: China Forestry Publishing.

NFGA (2016). China-Vietnam training seminar held in Guilin recently. Beijing: China Forestry Publishing.

NFGA (2017). The inter-department linkage mechanism for combating illegal wildlife trade was officially launched. Beijing: China Forestry Publishing.

NFGA (2018). China-ASEAN forestry cooperation made new progress. Beijing: China Forestry Publishing.

NFGA (2019). The second Inter-ministerial Joint Conference on Combating Illegal Wildlife Trade proposed to work in tandem to combat illegal wildlife trade more vigorously and effectively. Beijing: China Forestry Publishing.

NFGA (2020). Twenty-seven departments join forces to combat illegal trade in wild flora and fauna. Beijing: China Forestry Publishing.

Ngoc, A. C., and Wyatt, T. (2013). A green criminological exploration of illegal wildlife trade in Vietnam. Asian J. Criminol. 8, 129–142. doi: 10.1007/s11417-012-9154-y

Nijman, V. (2010). An overview of international wildlife trade from Southeast Asia. Biodivers. Conserv. 19, 1101–1114. doi: 10.1007/s10531-009-9758-4

Nijman, V., and Shepherd, C. R. (2009). Wildlife trade from ASEAN to the EU: issues with the trade in captive-bred reptiles from Indonesia. Brussels: TRAFFIC Europe.

Nijman, V., and Shepherd, C. R. (2014). Emergence of Mong La on the Myanmar–China border as a global hub for the international trade in ivory and elephant parts. Biol. Conserv. 179, 17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2014.08.010

Nijman, V., and Shepherd, C. R. (2015). Ongoing trade in illegally sourced tortoises and freshwater turtles highlights the need for legal reform in Thailand. Nat. Hist. Bull. Siam Soc. 61, 3–6.

Nijman, V., Shepherd, C. R., and Sanders, K. L. (2012). Over-exploitation and illegal trade of reptiles in Indonesia. Herpetol. J. 22, 83–89.

Nijman, V., Zhang, M. X., and Shepherd, C. R. (2016). Pangolin trade in the Mong La wildlife market and the role of Myanmar in the smuggling of pangolins into China. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 5, 118–126. doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2015.12.003

OECD (2019). The illegal wildlife trade in Southeast Asia: institutional capacities in Indonesia, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. Paris: OECD Publishing, doi: 10.1787/14fe3297-en

Phelps, J., Biggs, D., and Webb, E. L. (2016). Tools and terms for understanding illegal wildlife trade. Front. Ecol. Environ. 14:479–489. doi: 10.1002/fee.1325

Platt, S. G., Sovannara, H., Kheng, L., Holloway, R., Stuart, B. L., and Rainwater, T. R. (2008). Biodiversity, exploitation, and conservation of turtles in the Tonle Sap Biosphere Reserve, Cambodia, with notes on reproductive ecology of Malayemys subtrijuga. Chelonian Conserv. Biol. 7, 195–204. doi: 10.2744/CCB-0703.1

Platt, S. G., Swe, T., Ko, W. K., Platt, K., Myo, K. M., Rainwater, T. R., et al. (2011). Geochelone platynota (Blyth 1863) – Burmese Star Tortoise, Kye Leik. Gland: IUCN.

Raza, R. H., Chauhan, D. S., Pasha, M. K. S., and Sinha, S. (2012). Illuminating the blind spot: A study on illegal trade in leopard parts in India (2001–2010). New Delhi: TRAFFIC India.

Rostro-Garcia, S., Kamler, J. F., Ash, E., Clements, G. R., Gibson, L., Lynam, A. J., et al. (2016). Endangered leopards: range collapse of the Indochinese leopard (Panthera pardus delacouri) in Southeast Asia. Biol. Conserv. 201, 293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2016.07.001

Schoppe, S. (2009). Status, trade dynamics and management of the Southeast Asian Box Turtle Cuora amboinensis in Indonesia. Malaysia: TRAFFIC Southeast Asia.

Shepherd, C. R., and Nijman, V. (2007). An assessment of wildlife trade at Mong La market on the Myanmar-China border. TRAFFIC Bull. 21, 85–88.

Slobodian, L. (2014). Addressing transnational wildlife crime through a Protocol to the UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime: A scoping paper. Bonn: IUCN Environmental Law Centre.

Sodhi, N. S., Koh, L. P., Brook, B. W., and Ng, P. K. L. (2004). Southeast Asian biodiversity: an impending disaster. Trends Ecol. Evolut. 19, 654–660. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2004.09.006

State Council (2016). The Sixth Joint Meeting for the National Interagency CITES Enforcement Coordination Group was held in Beijing. Beijing: State Council.

Statista (2020). Number of mutual legal assistance requests sent by Ministry of Justice of China abroad from 2012 to 2017. Tokyo: Statista.

Strydom, H. (2016). “Transnational organized crime and the illegal trade in endangered species of wild fauna and flora,” in International law and transnational organized crime, eds P. Hauck and S. Peterke (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 264–285.

Sun, J. (2016). A review of the rule of law for trade in wildlife and wildlife products in China. Bus. Cult. 25, 88–93.

Tensen, L. (2016). Under what circumstances can wildlife farming benefit species conservation? Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 6, 286–298. doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2016.03.007

The Law Library of Congress (2020). Regulation of wild animal wet markets in selected jurisdictions. Washington DC: The Law Library of Congress.

TRAFFIC (2016). Officials from China and Lao PDR receive CITES law enforcement training. Cambridge: TRAFFIC.

TRAFFIC (2017a). Malaysian Customs make large seizure of threatened Malagasy tortoises. Cambridge: TRAFFIC.

TRAFFIC (2017b). Malaysian enforcement blazes a sizzling trail with a spate of high-profile wildlife seizures. Cambridge: TRAFFIC.

TRAFFIC (2019). Record setting 30-tonne pangolin seizure in Sabah ahead of World Pangolin Day. Cambridge: TRAFFIC.

Trouwborst, A., Blackmore, A., Boitani, L., Bowman, M., Caddell, R., Chapron, G., et al. (2017). International wildlife law: understanding and enhancing its role in conservation. BioScience 67, 784–790. doi: 10.1093/biosci/bix086

UN General Assembly (2000). United Nations Conventions against Transnational Organized Crime. UN General Assembly Resolution A/RES/55/25. New York: UN General Assembly.

UN General Assembly (2015). Tackling illicit trafficking in wildlife. UN General Assembly Resolution A/RES/69/314. New York: UN General Assembly.

UNEP (2016). Illegal trade in wildlife and wildlife products. Resolution UNEP/EA.2/Res.14. Cambridge: UNEP.

UNESC (2013). Crime prevention and criminal justice responses to illicit trafficking in protected species of wild fauna and flora. UNESC Resolution E/RES/2013/40. Brazil: UNESC.

UNODC (2008). Information Submitted by States in Their Responses to the Checklist/Questionnaire on the Implementation of the United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime for the First Reporting Cycle. CTOC/COP/2008/CRP.7. Vienna: UNODC.

UNODC (2010). The globalization of crime: a transnational organized crime threat assessment. Vienna: UNODC.

UNODC (2013). Transnational organized crime in East Asia and the Pacific: a threat assessment. Vienna: UNODC.

UNODC (2017a). Criminal justice response to wildlife crime in Malaysia: a rapid assessment. Vienna: UNODC.

UNODC (2017b). Criminal justice response to wildlife crime in Thailand: a rapid assessment. Vienna: UNODC.

UNODC (2019). Transnational organized crime in Southeast Asia: evolution, growth and impact. Bangkok: UNODC Regional Office for Southeast Asia and the Pacific.

van Uhm, D. P. (2016). The illegal wildlife trade: inside the world of poachers, smugglers and traders. Switzerland: Springer.

van Uhm, D. P., and Nijman, R. C. C. (2020). The convergence of environmental crime with other serious crimes: subtypes within the environmental crime continuum. Eur. J. Criminol. 2020, 1–20. doi: 10.1177/1477370820904585

van Uhm, D. P., and Wong, R. W. Y. (2019). Establishing trust in the illegal wildlife trade in China. Asian J. Criminol. 14, 23–40. doi: 10.1007/s11417-018-9277-x

Wang, B., and McBeath, J. (2017). Contrasting approaches to biodiversity conservation: China as compared to the United States. Environ. Dev. 23, 65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.envdev.2017.03.001

WCO (2014). Operation Cobra II: African, Asian and North American law enforcement officers team up to apprehend wildlife criminals. Brussels: WCO.

WCS (2016). Laos, China and Vietnam enhance cooperation to combat transnational wildlife trafficking networks. Bengaluru: WCS.

World Bank (2016). Project information document: country Vietnam report. Washington, D.C: World Bank.

Wyatt, T., van Uhm, D., and Nurse, A. (2020). Differentiating criminal networks in the illegal wildlife trade: organized, corporate and disorganized crime. Trends Organiz. Crime 2020, 1–17. doi: 10.1007/s12117-020-09385-9

Yu, W., and Czarnezki, J. J. (2013). Challenges to China’s Natural Resources Conservation and Biodiversity Legislation. Environ. Law 43, 125–144.

Zhang, L. (2016). China-ASEAN 2016 Forestry Cooperation Forum held in Nanning. Guangxi Forestry 9, 1–7.

Zhang, L., and Yin, F. (2014). Wildlife consumption and conservation awareness in China: A long way to go. Biodivers. Conserv. 23, 2371–2381. doi: 10.1007/s10531-014-0708-4

Zhang, L., Hua, N., and Sun, S. (2008). Wildlife trade, consumption and conservation awareness in southwest China. Biodiver. Conserv. 17, 1493–1516. doi: 10.1007/s10531-008-9358-8

Keywords: UNTOC, species conservation, wildlife trafficking, international cooperation, policy coordination, legal frameworks

Citation: Jiao Y, Yeophantong P and Lee TM (2021) Strengthening International Legal Cooperation to Combat the Illegal Wildlife Trade Between Southeast Asia and China. Front. Ecol. Evol. 9:645427. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2021.645427