94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Ecol. Evol., 12 March 2021

Sec. Conservation and Restoration Ecology

Volume 9 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2021.608057

This article is part of the Research TopicTowards Legal, Sustainable and Equitable Wildlife TradeView all 19 articles

Overexploitation is a critical threat to the survival of many species. The global demand for wildlife products has attracted considerable research attention, but regional species exploitation histories are more rarely investigated. We interviewed 169 villagers living around seven terrestrial nature reserves on Hainan Island, China, with the aim of reconstructing historical patterns of hunting and consumption of local wildlife, including the globally threatened Chinese pangolin (Manis pentadactyla) and Hainan peacock-pheasant (Polyplectron katsumatae), from the mid-20th century onwards. We aimed to better understand the relationship between these past activities and current consumption patterns. Our findings suggest that eating pangolin meat was not a traditional behaviour in Hainan, with past consumption prohibited by local myths about pangolins. In contrast, local consumption of peacock-pheasant meat was a traditional activity. However, later attitudes around hunting pangolins and peacock-pheasants in Hainan were influenced by pro-hunting policies and a state-run wildlife trade from the 1960s to the 1980s. These new social norms still shape the daily lifestyles and perceptions of local people towards wildlife consumption in Hainan today. Due to these specific historical patterns of wildlife consumption, local-adapted interventions such as promoting substitute meat choices and alternative livelihoods might be effective at tackling local habits of consuming wild meat. Our study highlights the importance of understanding the local historical contexts of wildlife use for designing appropriate conservation strategies.

Unsustainable harvesting of wildlife, in particular hunting for meat consumption, has been recognised as one of the major causes of global biodiversity loss (Bennett and Robinson, 2000; Corlett, 2007; Benítez-López et al., 2017; Grooten and Almond, 2018). Many different motivations underlie hunting for meat consumption, from meeting subsistence protein needs to a demand for luxury dishes. Drivers and patterns of wildlife exploitation also vary across cultures and geographic regions (Fa et al., 2003; Sandalj et al., 2016). In particular, biodiversity in regions with very high human population densities, such as China, is often under intensive pressure from exploitation and other human activities (Zhang and Yin, 2014; USAID Wildlife Asia, 2018). As a result, many hunting-induced population declines and regional extinctions have been documented in China across a diverse range of species (Greer and Doughty, 1976; Thapar, 1996; Rookmaaker, 2006; Turvey et al., 2015a), and further population collapses of formerly widespread and abundant species, such as the Chinese giant salamander (Andrias davidianus) and yellow-breasted bunting (Emberiza aureola), continue to occur due to extensive and unsustainable demand for the wild meat market (Wang et al., 2004; Kamp et al., 2015; Cunningham et al., 2016). Exploitation of wildlife in China has occurred throughout recent history, but has escalated rapidly during the past few decades (Cunningham et al., 2016). Historical patterns of wildlife consumption, and the extent to which such patterns might have become modified during recent periods of socio-cultural change, are therefore important to understand when designing conservation management strategies for species threatened by overexploitation (Huber, 2012; Duffy et al., 2016).

Pangolins (Family Manidae) are recognised as international conservation priorities. They are heavily trafficked for consumption, and have also been identified as potential intermediate hosts in the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020 (Choo et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). The enormous volumes of pangolins seen in wildlife trade has led to recent revision of their IUCN Red List status, with the Chinese pangolin (Manis pentadactyla), Sunda pangolin (M. javanica) and Philippine pangolin (M. culionensis) now listed as Critically Endangered, and the five other pangolin species listed as Endangered or Vulnerable (IUCN, 2020). China is one of the main destination markets for international pangolin trade due to demand for meat, body parts, and scales. Much research attention has been focused on the international trade of pangolin products and hunting of pangolins in source countries, mainly in Africa (Challender and Hywood, 2012; Soewu and Sodeinde, 2015; Cheng et al., 2017; Ingram et al., 2019). Conversely, hunting pressure on native pangolin populations within demand countries such as China has been relatively neglected (Yang et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2016).

The Chinese pangolin was formerly distributed widely across central and southern China. However, it has declined severely during recent decades, making evidence-based conservation of its remaining populations an important goal (Wu et al., 2004; Yang et al., 2018). This population decline has resulted in China uplisting the species from Class II to Class I protection status under national wildlife protection law in 2020 (SFGA of China, 2020). However, due to their cryptic and nocturnal habits and their low population densities across a wide geographic range, estimating current pangolin population size and distribution is challenging, and few studies have attempted to estimate population densities, abundance or trends using standard census techniques. In contrast, social science approaches offer some promise for gaining evidence on these population parameters to guide conservation. One such study was conducted in 2015 on Hainan Island, China’s southernmost province, where rural household interview surveys suggested that a small pangolin population might still persist within the island’s remaining tropical forests (Nash et al., 2016). It is therefore urgent to (i) assess levels and drivers of potential exploitation of surviving pangolin populations on Hainan, and better understand the socio-cultural context within which local people interact with pangolins, and (ii) inform conservation interventions to reduce exploitation and demand at the community level.

Collecting conservation-relevant data on sensitive behaviours using social science methods is often difficult, due to interviewee reticence in reporting accurate information on potentially illegal activities (Nuno and St. John, 2015; Hinsley et al., 2019; Jones et al., 2020). However, whereas absolute baselines on human-wildlife interactions are difficult to obtain, it is still possible to detect differences in the timing or magnitude of reported interactions with different exploited species that occur within the same landscapes, thus providing a relative between-species signal for use in conservation planning (Turvey et al., 2015b). Rural subsistence communities in Hainan are known to exploit and consume other threatened and protected species in addition to pangolins (Gaillard et al., 2017; Gong et al., 2017; Xu et al., 2017). In particular, galliform birds are hunted for food across China (Liang et al., 2013; Zhou et al., 2015; Kong et al., 2018; Chang et al., 2019). The island’s Endangered endemic pheasant, the Hainan peacock-pheasant (Polyplectron katsumatae), is a Class I Protected Species that also occurs within remaining tropical forests across Hainan, and is threatened by illegal hunting and habitat destruction. The peacock-pheasant population is thought to have declined rapidly since the 1950s, with an estimated population loss of almost 80% compared to historical levels (Liang and Zhang, 2011). As pangolins and peacock-pheasants share similar threats, protection status, and inferred distributions across Hainan, they may constitute a useful species pair for assessing reported patterns of hunting and consumption.

We conducted semi-structured interviews in Hainan to establish a new baseline on past and present hunting practices associated with pangolins and peacock-pheasants in low-income subsistence communities across the island, including targeted interviews with hunters, consumers, restaurants, and wild meat dealers. Our results demonstrate different patterns and perceptions of hunting and consuming of these species, associated with policy changes in recent decades and their conflict with local traditions. These findings can guide evidence-based conservation planning for these protected species by informing local-adapted interventions based upon understanding of historical behaviour patterns.

We conducted household interviews from November 2016 to April 2017 around seven terrestrial protected areas in Hainan: Bawangling, Diaoluoshan, Jianfengling, Wuzhishan and Yinggeling national nature reserves, and Jiaxi and Limushan provincial nature reserves. All of these reserves contain monsoon forests that represent potential pangolin and peacock-pheasant habitat. However, recent baseline distributions and local occurrence data for both species are unavailable. The reserves are all surrounded by numerous low-income rural communities mainly comprising Li and Miao ethnic minorities. Local people often utilise resources collected inside the reserves (Fauna and Flora International China Programme, 2005; Turvey et al., 2017). We sampled villages identified by local guides that were within walking distance of reserves, in which inhabitants were known to hunt wildlife within nearby forests and were also open to be interviewed by outsiders. We conducted interviews in 3–13 villages adjacent to each reserve, covering 42 villages within four administrative counties (Baisha, Ledong, Qiongzhong, and Wuzhishan) in total (Figure 1).

We conducted between 1 and 11 interviews per village. We initially identified interviewees through introductions by local guides, then used snowball sampling to identify subsequent potential interviewees who might hunt or hold hunting knowledge (Newing, 2010). Most interviews were conducted with village inhabitants on a one-to-one basis; a small number of interviews were instead conducted in groups, during which no attitudinal or demographic questions were asked. Rangers and reserve staff were also interviewed when available and were not asked about their perceptions on current hunting behaviour. Villagers younger than 18 years old were not interviewed, only one interviewee was interviewed per household to ensure independence of responses, and both males and females were interviewed. No maximum sample size was set for interviewees in each village. We explained that we were conducting anonymous interviews to understand people’s perceptions and knowledge about hunting, obtained verbal consent before all interviews, and informed respondents they could stop at any time. Cotton towels (about 0.2 USD each) were given as gifts to increase participation rates and show gratitude for the interviewee’s time. The choice of gift was given careful consideration, and aimed at being useful but not too expensive for interviewees, so that motivation to participate would not be mainly due to receipt of the gift. Research design was approved by the Department of Geography Ethics Review Group, University of Cambridge (#1503).

We used an anonymous questionnaire to collect data on interviewees’ reported hunting experiences, intentions, and attitudes, with a specific focus on the hunting of pangolins and peacock-pheasants. We also collected basic demographic data on interviewees’ age, gender, ethnic group, income level and education level. However, we did not record names or other personal information that could identify individuals. The questionnaire consisted of a series of multiple-choice and open-ended questions that took up to 30 min to complete (see Supplementary Material). Part of the questionnaire design was based on the Theory of Planned Behaviour, and aimed to investigate people’s attitude towards hunting (Ajzen, 2002, 2006). Specifically, we used Likert scales and multiple-choice questions to determine interviewees’ experiential and instrumental attitudes towards hunting (i.e., whether they feel hunting benefits themselves or others), injunctive and descriptive social norms (i.e., whether people around them approve and/or practice hunting), and perceived behaviour control (i.e., whether they are capable of hunting and whether they feel hunting is a self-willing behaviour). We also asked about hunting practices during the previous 2-year period and about future intention to hunt, and whether interviewees held utilitarian values about nature (Gamborg and Jensen, 2016). In addition to asking about hunting wildlife in general, we also asked specifically about hunting of pangolins and peacock-pheasants, and interviewees’ knowledge of these two species. We validated whether interviewees could recognise pangolins and peacock-pheasants by showing pictures to aid identification (sourced from pangolins.org and arkive.org), and further asked them to provide descriptions of key morphological characters (e.g., scales on pangolins; eyespot-patterned tail feathers of peacock-pheasants). All interviews were conducted by the first author in Mandarin, and answers were recorded in Chinese. The majority of interviewees spoke Mandarin, but some older people spoke only Li and Miao languages, and interviews were carried out with translation assistance provided by bilingual local guides.

We also conducted additional targeted interviews with professional hunters, potential wild meat selling restaurants, wild meat consumers and wild meat dealers, with potential interviewees accessed through social networks and introduced by trusted middlemen. Because recruitment rates were expected to be low, we did not set a maximum sample size, and results are presented in a descriptive manner. High confidentiality was assured for these interviewees to encourage participation; we did not ask about any demographic variables, and interview questions mainly focused on interviewees’ personal hunting, selling, or consuming behaviours.

We used binomial general linear models (GLMs) to identify factors that correlated with interviewees’ self-reported hunting behaviour (with self-reported hunters defined as interviewees who said it was “possible” or “largely possible” that they would go hunting in the future, and/or who admitted to hunting during the previous 2-year period). The maximal model included 16 variables: respondent age, gender, education, ethnic group, occupation, annual income, county, nearby reserve, and eight other variables associated with the Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen, 2002, 2006). We used stepwise selection (stepAIC) to find the best-performing model with the lowest Akaike information criterion (AIC). We standardised variable coefficients in the final model using beta to identify the most influential factor. We used two additional binomial GLMs, built following the same procedure, to determine potential demographic predictors for interviewees who reported knowledge about pangolins or peacock-pheasants. We also conducted Spearman rank correlations and z-tests to investigate knowledge distribution patterns among interviewees. All analyses were performed in RStudio under R version 3.5.2 (RStudio Team, 2015). Answers to open-ended questions on interviewees’ knowledge about pangolins or peacock-pheasants were analysed using thematic analysis; responses were coded into different categories, then grouped into themes to reveal general patterns (Gavin, 2008; Newing, 2010). Price data were inflated to prices in 2017 in Chinese yuan using the consumer price index (National Bureau of Statistics, 2020).

We conducted interviews with 169 individuals or groups in 42 villages, including 34 rangers and reserve staff, 131 villagers, and four villager group interviews (group sizes ranging between 4 and 10 villagers) (Table 1). We also successfully interviewed one active professional hunter, three wild meat dealers, five restaurant owners, and four wild meat consumers across Hainan. The locations of these 13 interviewees remained confidential and were not recorded.

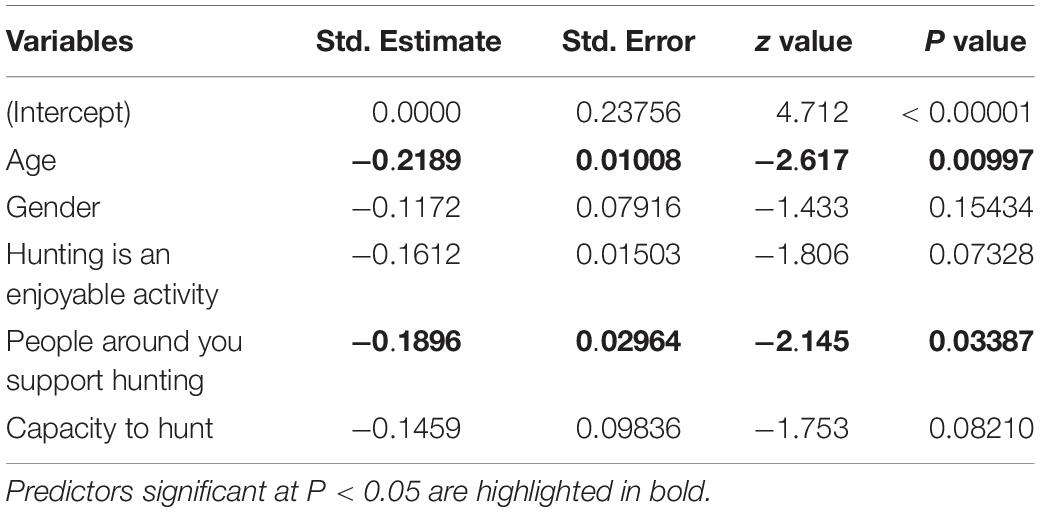

Most interviewees expressed negative attitudes toward hunting, although a relatively high proportion agreed that hunting was an enjoyable activity (Table 2). Most interviewees also reported that hunting was an uncommon activity, with only 16 out of 131 interviewees (12.2%) considering that hunting was frequently or sometimes practiced. Self-reported hunting behaviour was also uncommon, and only 13 interviewees (10%) self-identified as active or potential future hunters. GLM results showed that age and perceived local supportiveness for hunting were significantly correlated with self-reported hunting behaviour, with self-reporters tending to be younger and feel that people around them supported hunting (Table 3).

Table 3. Results for GLM investigating predictors of self-reported hunting behaviour with lowest AIC value (AIC = 45.074).

Although hunting was reported as uncommon, seven out of 169 interviewees (4.1%) specifically reported having hunted either pangolins or peacock-pheasants since 2010. Five interviewees reported pangolin hunting incidents that occurred during 2014 or 2015 outside or within Jianfengling and Yinggeling reserves. For example, one interviewee from a village outside Jianfengling Reserve described how he had heard of a villager in an adjacent village catching and eating a pangolin that was found in cropland. Hunting of peacock-pheasants was described by one interviewee near Jianfengling Reserve as “frequent” and “occurring every year.” Another interviewee said that he often went to Nanle Mountain inside Yinggeling Reserve to hunt peacock-pheasants and other birds because he thought that this area was not protected. Hunting of other species was also reported without prompting during interviews, and several captive wild animals and hunting gear (snap traps and cage traps) were observed in villages during fieldwork, providing evidence of ongoing local hunting activities (Figure 2). Three interviewees also mentioned the “turtle rush,” a period of intensive local collecting of the golden coin turtle (Cuora trifasciata), a species highly valued in the pet trade.

Figure 2. Captive wild animals and hunting gears observed in villages during fieldwork. (a) Black-breasted leaf forest turtle (Geoemyda spengleri); (b) female silver pheasant (Lophura nycthemera); (c) Pallas’s squirrel (Callosciurus erythraeus); (d) crested serpent eagle (Spilornis cheela); (e) snap traps; (f) cage traps. Photo credit: Yifu Wang.

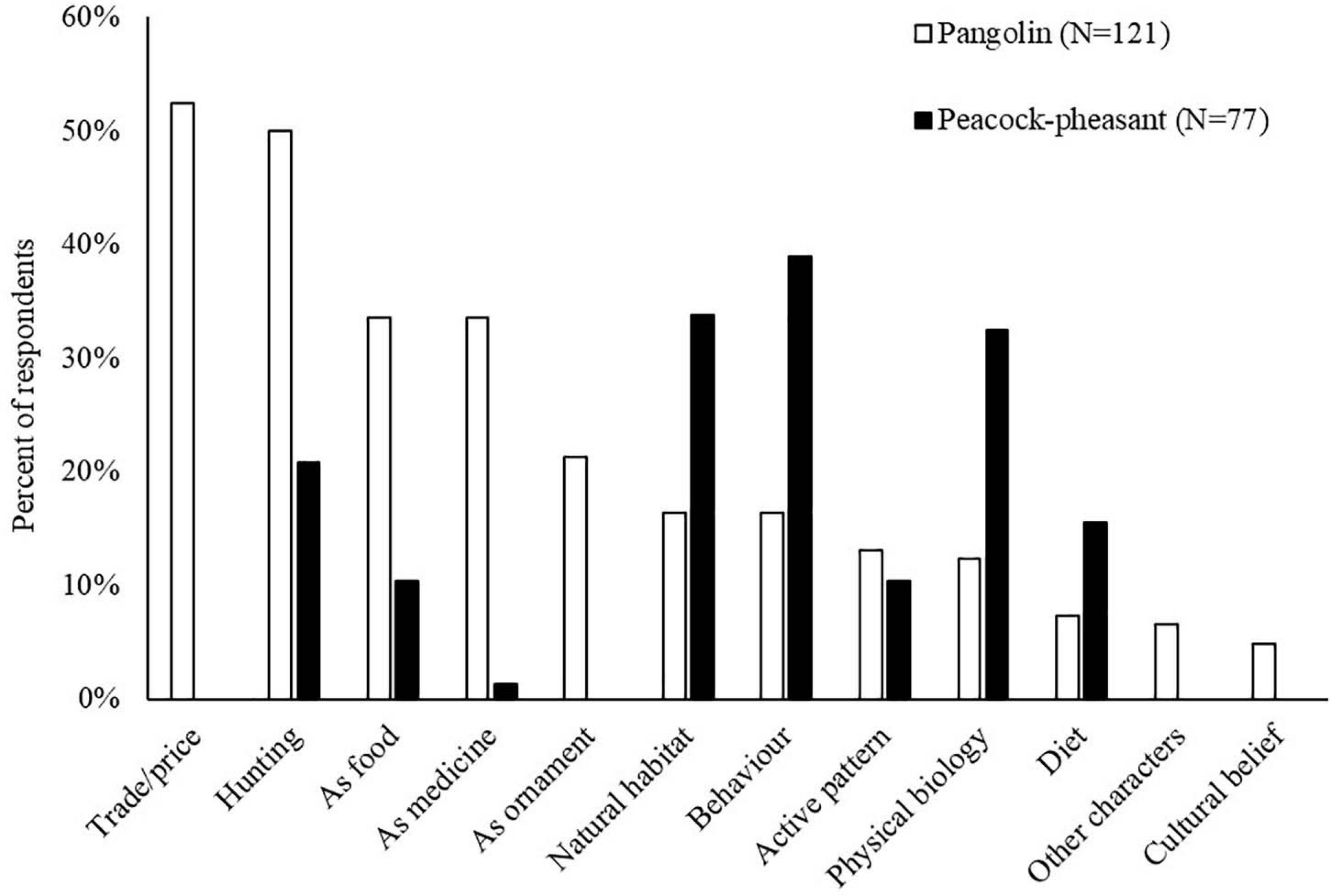

Our open-ended questions asked for knowledge about the two target species. A total of 121 interviewees (71.6%) provided information about pangolins, whereas only 77 interviewees (45.6%) provided information about peacock-pheasants, representing a statistically significant difference (z-test, P < 0.001). The relative amounts of different reported categories of knowledge also differed significantly between the two species (Spearman rank correlation, rho = 0.0340, P = 0.917) (Figure 3). GLM results revealed that the only predictor to be significantly correlated with whether interviewees reported pangolin information was age (N = 147, SE = 2.4, z = 3.8, P < 0.001; see Supplementary Material for full results), with older interviewees more likely to report information. Conversely, three predictors were significantly correlated with whether interviewees reported peacock-pheasant information (N = 147; county: Wuzhishan, SE = −1.6, z = −2.4, P < 0.05; age: SE = 1.2, z = 2.7, P < 0.01; occupation: state-enterprise employees, SE = 1.7, z = 2.9, P < 0.01; see Supplementary Material for full results), with older interviewees, interviewees not from Wuzhishan County, and interviewees working for state-owned enterprises more likely to report information.

Figure 3. Percentage of interviewees providing different categories of knowledge about pangolins and peacock-pheasants. Note that respondents may provide knowledge on more than one category.

There was a significant difference between the number of respondents reporting exploitation-related knowledge (i.e., trade and price, hunting, consumption, use as medicine, and ornamental use) for pangolins and for peacock-pheasants (98 reports for pangolin and 20 reports for peacock-pheasants; z test, P < 0.0001). Even non-hunters were found to be very familiar with pangolin exploitation. Indeed, these exploitation-related topics were all reported more frequently than any other categories of knowledge about pangolins, such as ecological or behavioural characteristics. The most frequently reported pangolin knowledge category was knowledge about trade and price, reported by 64 interviewees (52%). The second most frequently reported knowledge category was knowledge about hunting, reported by 61 interviewees (50%), which described hunting frequency or specific hunting techniques including looking for pangolin tracks, using dogs to track down pangolins, or smoking pangolins out of their burrows. Conversely, knowledge about peacock-pheasants focused more on behaviour (30 reports), habitat (26 reports), or physical biology (25 reports) rather than hunting (16 reports) or trade (0 reports) (Figure 3).

We did not obtain reports of historical hunting or trade from earlier than the 1960s. This might reflect the age limit of our interviewee sample, but might also be due to local beliefs mentioned by several interviewees (n = 6), in which pangolin hunting and utilisation was disapproved of in the past. Local myths regarded seeing a pangolin during the daytime as an omen representing either extreme fortune or bad luck (Katuwal et al., 2016), thus giving pangolins a more symbolic role in local culture rather than merely representing food items. This belief is apparently associated with the rarity of seeing these nocturnal animals during the daytime, combined with the reported local idea that pangolins feed on bones of the dead, also mentioned by Liu (1938).

Interviewees’ extensive knowledge on hunting and trading pangolins came from changing practices during the second half of the 20th century; 49 out of 121 interviewees (>40%) provided hunting or trade information specifically from the 1960s to the 1990s, with a peak of reported hunting during the 1980s. Interviewees described that pangolin hunting was directly supported by the Chinese government through legal commercial trade during this period, as state-owned supply and marketing cooperatives would purchase pangolin scales from locals for relatively high prices, as also reported by Wu et al. (2004). Hunting activity declined in the 1990s for two reasons: hunting was officially banned, and Hainan’s pangolin population had reportedly declined heavily by this period. The pangolin hunting period reportedly started and ended slightly later in more remote communities (i.e., those with reduced road access). Conversely, professional hunters reported that peacock-pheasants were never a main target species in Hainan due to their low body weight (around 0.5 kg per adult bird), meaning that they could not be sold for a high price. Instead, harvest of peacock-pheasants was mostly by-catch and/or for personal consumption.

These direct quotes from three interviewees illustrate the extent of hunting during the peak period and the subsequent collapse of the pangolin population:

“A village could catch a few hundred pangolins in total in one month back in the 1980s. I caught more than 20 myself.”

“Hunting and government purchasing started in 1976. Around that time, a local could catch more than 30 in one month. I caught more than 20 in 1985.”

“Lots of villagers searched for pangolins in the mountains during the 1990s, but they found only one or two per month at that time.”

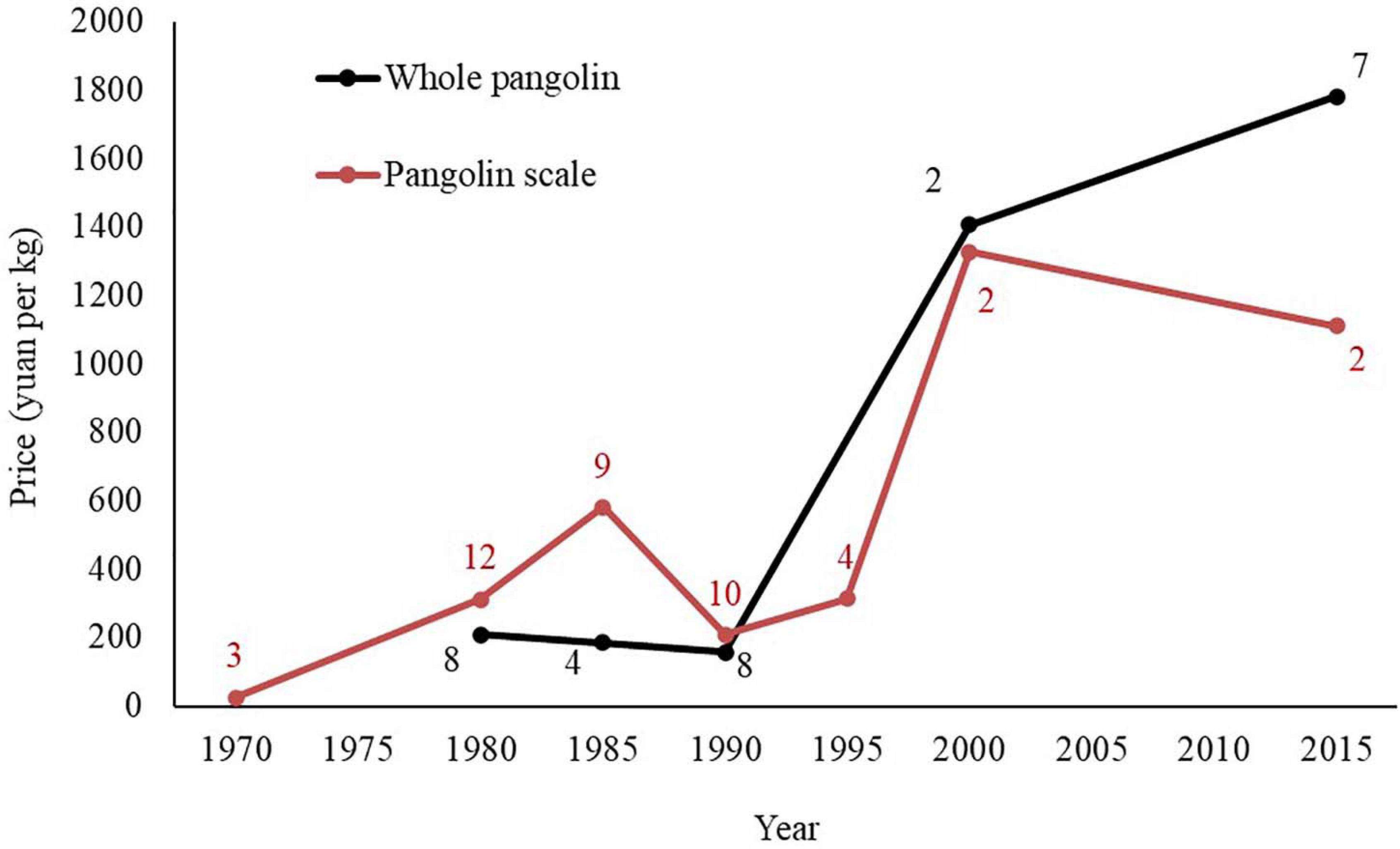

Information provided about pangolin trade included data on historical prices of whole pangolins and pangolin scales, which show an increase in price from the 1970s, a decline in the 1990s, and a more recent further increase (Figure 4). Professional hunters, wild-meat dealers and consumers also confirmed to us that the recent price of a whole pangolin was 2,000–3,400 yuan/kg (280–490 USD/kg).

Figure 4. Historical price of whole pangolins (black line) or pangolin scales (red line) reported by interviewees. Data are grouped into 5-year time bins, indicated on the x axis by the first year of each respective time bin. Mean reported prices are given for each time bin; numbers associated with each data point show the number of prices reported for that period.

None of the interviewed restaurant owners admitted to selling pangolin or peacock-pheasant products, but did confirm that they sold farmed wildlife species such as bamboo rats (Rhizomys spp.) and porcupines (Hystrix brachyura). These species and other wild animals from unknown sources, including passerines, squirrels and other rodents, and small carnivores, were also common in local markets, whereas pangolins and galliform birds were much rarer according to restaurant owners. This was consistent with information provided by consumers, who reported buying whole pangolins from markets that were then cooked in restaurants rather than buying dishes directly in restaurants. Both consumers and dealers reported that buying pangolins from markets took place under conditions of strong trust between buyers and sellers, with unknown buyers requiring guarantees from up to seven trusted middlemen.

The four interviewed consumers provided different reasons and scenarios for eating pangolin dishes. One consumer particularly liked the taste of pangolin meat and, since pangolins were rare and expensive, often invited business friends and colleagues to socialize for work when pangolins were available. Two consumers ate pangolin dishes at their workplaces during meals to which they were invited by other people, who ordered pangolin dishes to show respect to their guests due to the species’ high price and rarity. The fourth consumer regularly enjoyed eating wild meat dishes and considered that holding a wild meat party was a way to maintain friendships and social connections. According to this consumer, pangolins were consumed for their potential health benefits, but due to their high cost, the consumption was not frequent.

Our results provide a new baseline to understand patterns, levels, and socio-cultural drivers of local hunting of pangolins and other conservation-priority species in Hainan Island, China. Unsurprisingly, direct questioning of rural interviewees provided relatively low levels of self-reported hunting, a result consistent with previous findings (Van Der Heijden et al., 2000; Nuno and St. John, 2015). However, interviewees still provided substantial information about hunting of pangolins, peacock-pheasants and other wildlife, and local demand for wild meat. These findings indicate that Hainan’s biodiversity faces continuing pressures that threaten its future. Enforcement and management agencies have made efforts to reduce regional wildlife hunting and consumption behaviours, and our results suggest that some of these behaviours (notably pangolin hunting) were more common in the past compared to today. However, observed decreases in hunting may have been driven by population declines rather than effective enforcement, and remaining illegal wildlife hunting and consumption needs to be tackled urgently. Our study provides a new understanding of hunting and consumption that can contribute important insights for identifying potential solutions, and also includes crucial baselines of historical change that further aid conservation planning.

Hainan’s rich biodiversity has constituted an important resource for local communities for millennia. Even pre-modern regional human interactions with many vertebrate species were unsustainable on Hainan, leading to numerous prehistoric and historical extinctions (Turvey et al., 2019), and escalating natural resource use has placed increasing pressure on regional biodiversity (Chau et al., 2001; Gong et al., 2006; Xu et al., 2017). However, although historical accounts indicate that pangolins have been exploited for food and medicine on Hainan since at least the early 20th century (Allen, 1938; Liu, 1938), data from our study suggest that local myths reduced hunting for consumption, thus keeping hunting pressure relatively low and stable until the Chinese government promoted a nation-wide state-run commercial trade of pangolins from the 1960s (Wu et al., 2004). This is also supported indirectly by the heavy pangolin harvests reported in the 1960s–1980s followed by the sudden decrease in offtake in the 1990s. If hunting pressure had been high before the mid-20th century, local pangolin populations may not have been sufficiently abundant to support such a high harvest load, and the subsequent decline in harvests would also not have been so drastic. This pattern of recent historical change in hunting intensity of pangolins contrasts with peacock-pheasants, which appear to have been hunted more than pangolins in the past because there were no cultural taboos restricting such behaviour. Conversely, peacock-pheasants did not experience an increase in hunting pressure driven by changes in state policy.

Cultural taboos play an important role in regulating a wide range of local behaviours and support sustainable interactions with biodiversity across many cultures and social-ecological systems (Colding and Folke, 2001; Wadley and Colfer, 2004). However, as demonstrated by the increased acceptability of hunting pangolins in Hainan, such taboos can be eroded easily by rapid societal change or outweighed by monetary incentives, and are often hard to restore following their disruption (Golden and Comaroff, 2015; Katuwal et al., 2016). State-encouraged hunting during past decades has also changed the nature of specific human-wildlife interactions and has driven severe population declines and extirpations in other Chinese species, such as tigers (Panthera tigris) (Coggins, 2003; Kang et al., 2010).

Patterns of pangolin knowledge, hunting and consumption across Hainan are therefore very different compared to local awareness and interactions with peacock-pheasants as a result of this official policy change. Whereas increased knowledge about both species was positively associated with interviewee age in our analyses, fewer interviewees had knowledge about peacock-pheasants, and knowledge about this species also showed geographic variation and was greater among state-enterprise employees, a category that consists mainly of reserve workers. These results suggest that although peacock-pheasants are known to be hunted (Liang and Zhang, 2011), they have been less of a priority target compared to pangolins, which do not show any variation in knowledge across our entire survey area or across all demographic sectors of our interviewee sample. In addition, interviewees did not provide much information about peacock-pheasant trade as there was little wider demand for this species. However, we note that even though peacock-pheasants might face lower intentional hunting pressure comparing to pangolins, hunting of this species still needs conservation attention due to a lack of knowledge of sustainable off-take thresholds, their probable low population size, and potentially high by-catch rates (e.g., from snares) as suggested by our interviewee data. As one of the most threatened galliforms in China, this species is also at potential risk of becoming valued due to its rarity, a main driver of consumption of luxury wildlife dishes (Sandalj et al., 2016; Shairp et al., 2016; Cardeñosa, 2019).

From an historical perspective, hunting first became formally regulated in China in 1989 when the first wildlife protection law was enacted, and hunting of pangolins, peacock-pheasants, and many other wildlife species was banned through their listing as Protected Animals (SFA of China, 1989). Hunting in general is also prohibited within the seven protected areas included in our survey, which were established from the 1970s to the 2000s (Ministry of Ecology and Environment of China, 2012). The rapid change in government policy did not lead to a sudden end in hunting or trade of wildlife products, and our results show that the price of pangolin products increased substantially during the 1990s. This economic change might reflect not only pangolin population decline, but also the shift from a controlled price to a market price where supply capacity would have a greater impact on economic value (Gale, 1955; Courchamp et al., 2006).

Our data also show that shifts in attitudes towards hunting and consuming wildlife are still ongoing. Although the majority of interviewees reported negative attitudes towards hunting, many still enjoyed hunting. These results suggest either that levels of subsistence or economic hunting were underreported in our study, or that recreational hunting remains popular (Phelps et al., 2016). Indeed, enjoyment and recreational value are major drivers of local hunting in many other parts of rural China (Chang et al., 2019). Recreational use of wildlife was also highlighted in our wild meat consumer survey in which wild meat parties with friends were mentioned as a frequent and important event. It is also interesting to note that hunting is often phrased as a solitary activity. In contrast, wild meat parties are a social activity, and need to be considered separately from recreational wildlife meat consumption.

Furthermore, several responses in our study demonstrate that understanding of current conservation regulations is incomplete. For example, some hunting activities were not considered to constitute “hunting” by interviewees, such as the “turtle rush” that overharvested golden coin turtles and many other reptile species (Gong et al., 2006; Gaillard et al., 2017). Several interviewees were also unclear about which areas were protected, or appeared unconcerned about openly discussing hunting protected species outside reserve boundaries as if protected animals were only protected in reserves. These observations might suggest the lack of using appropriate language when communicating with locals, and highlight potential future directions.

There are some unavoidable limitations in our study design. Illegal behaviours such as hunting are likely to be sensitive to direct questioning. Specialist interview techniques have been developed to attempt to overcome this problem (Hinsley et al., 2019; Jones et al., 2020), but restrictions such as sample size, design and analytical complexity, and time constraints prohibited application of these techniques in this study. Although some previous studies have obtained valuable results about sensitive behaviours through the use of direct questioning techniques (Kroutil et al., 2010), we assume that some interviewees are likely to under-report personal hunting behaviours, while over-reporting is much less likely. However, 10% of our interviewee sample admitted to recent hunting or to being potential hunters. This is not a low percentage given the known pressures from hunting that face many highly threatened species in Hainan (Gong et al., 2006; Liang et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2017). This figure can be treated as a minimum estimate, and probably underestimates the real number of hunters in our study. We also note that our use of snowball sampling rather than random sampling might conceivably have led to preferential selection of interviewees who were more likely to discuss hunting and hunting-related knowledge, thus making it difficult to infer wider levels of hunting across rural Hainan from our data. However, overall our findings suggest that there is a continuing and urgent need to tackle hunting as a threat to biodiversity in Hainan.

Other points highlighted in our results might be helpful for tackling ongoing hunting pressure in Hainan. Firstly, self-reported hunters tended to believe that people around them supported hunting. However, our results also indicate that most interviewees held negative attitudes towards hunting. We acknowledge that some interviewees might have misreported their true opinions on hunting during interviews. However, conservation mitigations could focus on this reported difference between perceived and actual social norms to encourage desired behaviour change, a well-studied concept that has been applied in many areas beyond wildlife conservation (Zhang et al., 2010; McDonald et al., 2014). Secondly, we suggest that the terminology associated with hunting, and regulations associated with hunting and protected areas, need further clarification through improved local educational activities to reduce misunderstanding and the perpetuation of unwanted behaviours. Lessons should be learned from this historical policy change and how it failed to convey these terminologies clearly, to avoid similar loopholes in future.

Consumption of wild animal products has also been impacted by the rapid changes in hunting policy. Such change can lead to different social norms related to consuming of different species. The change in pangolin exploitation pattern revealed in our study and the contrasts with that of peacock-pheasants support this conclusion. As the result, strategies to change wildlife consumption behaviour in Hainan should not focus solely on the conservation status or threats of species of concern, but also on the social associations that these species provide to consumers, whether it is recreational use or health benefits. Appropriate conservation mitigations should thus include encouraging suitable substitutes, and helping to establish new social norms (Clarke et al., 2007; Drury, 2009).

Our study highlighted that conservation interventions should build upon the understanding that current patterns of wildlife exploitation and consumption could be a legacy of past policy changes and shifting social norms. Due to the current COVID-19 pandemic, regulations on trading and consuming wild animal products have now become much tighter in China (National People’s Congress of China, 2020). The corresponding policy change means that species traditionally common in trade, such as bamboo rats and porcupines, can no longer be traded. A new social norm needs to be established. Indeed, our fieldwork was conducted before the COVID-19 outbreak, providing a baseline for future studies on the impact of these new policy shifts on local hunting and wildlife consumption behaviours. On the other hand, ongoing hunting practices in rural areas of Hainan and other parts of China require extra management attention, as human interactions with threatened wildlife species might pose threats not only to biodiversity but also to public health. Various bans on hunting and consuming wild animals have been established since 1989 and intensively recently to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic. However, changing public behaviours by implementing bans is just the first step (Ribeiro et al., 2020; Zhu and Zhu, 2020). Establishing and accepting such new social norms and adhering to desired behaviours is the final goal, and understanding the history of how social norms have changed can provide valuable insights for current management.

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because original raw data will not be shared with a third party as part of the ethics requirement. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to YW.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Department of Geography Ethics Review Group, University of Cambridge. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with national legislation and institutional requirements.

YW, NL-W, and ST all contributed to the initial design of the project, data analysis, revising the first draft, and the approval of the final submission. YW collected data and wrote the first draft. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We thank volunteers from Hainan Blue Ribbon Volunteer Organization, Hainan Laotao Volunteer Organization, Ledong Xinlianxin Volunteer Organization, Hainan Forestry Administration, Hainan Forestry Research Institute (Tongshi Branch), and Jianfengling National Nature Reserve for help with surveys in Hainan. We give special thanks to all anonymous respondents who participated in surveys, and people who helped with social network access to respondents. We also thank Heidi Ma and Helen Nash for help with project coordination and questionnaire design.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fevo.2021.608057/full#supplementary-material

Ajzen, I. (2002). Constructing a TPB questionnaire: conceptual and methodological considerations. Available online at: http://chuang.epage.au.edu.tw/ezfiles/168/1168/attach/20/pta_41176_7688352_57138.pdf (accessed March 3, 2021).

Allen, G. M. (1938). “The mammals of China and Mongolia: natural history of central Asia,” in Central Asiatic Expeditions of the American Museum of Natural History, Vol. 11, ed. W. Granger (New York: Andesite Press), 1–620.

Benítez-López, A., Alkemade, R., Schipper, A. M., Ingram, D. J., Verweij, P. A., Eikelboom, J. A. J., et al. (2017). The impact of hunting on tropical mammal and bird populations. Science 356, 180–183. doi: 10.1126/science.aaj1891

Bennett, E. L., and Robinson, J. G. (2000). “Hunting of wildlife in tropical forests: implications for biodiversity and forest peoples,” in Environment Department working papers, (Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group).

Cardeñosa, D. (2019). “Luxury seafood trade: extinction vs. lavishness,” in Encyclopedia of Ocean Sciences, eds J. K. Cochran, H. Bokuniewicz, and P. Yager (Cambridge: Academic Press), 409–413. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-409548-9.11206-0

Challender, D., and Hywood, L. (2012). African pangolins under increased pressure from poaching and intercontinental trade. Traffic Bull. 24, 53–55.

Chang, C. H., Williams, S. J., Zhang, M., Levin, S. A., Wilcove, D. S., and Quan, R.-C. (2019). Perceived entertainment and recreational value motivate illegal hunting in Southwest China. Biol. Conserv. 234, 100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2019.03.004

Chau, L. K., Chan, B. P., Fellowes, J. R., Hau, B. C., Lau, M. W., Shing, L. K., et al. (2001). Report of rapid biodiversity assessments at Bawangling National Nature Reserve and Wangxia Limestone Forest, western Hainan, 3 to 8 April 1998. South China Forest Biodiversity Survey Report Series No 2. Hong Kong: KFBG.

Cheng, W., Xing, S., and Bonebrake, T. C. (2017). Recent pangolin seizures in China reveal priority areas for intervention. Conserv. Lett. 10, 757–764. doi: 10.1111/conl.12339

Choo, S. W., Zhou, J., Tian, X., Zhang, S., Qiang, S., O’Brien, S. J., et al. (2020). Are pangolins scapegoats of the COVID-19 outbreak-CoV transmission and pathology evidence? Conserv. Lett. 2020, e12754. doi: 10.1111/conl.12754

Clarke, S., Milner-Gulland, E. J., and BjØrndal, T. (2007). Social, economic, and regulatory drivers of the shark fin trade. Mar. Resour. Economics 22, 305–327. doi: 10.1086/mre.22.3.42629561

Coggins, C. (2003). The tiger and the pangolin: nature, culture, and conservation in China. Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press. doi: 10.1515/9780824865122

Colding, J., and Folke, C. (2001). Social taboos: “invisible” systems of local resource management and biological conservation. Ecol. Applicat. 11, 584–600. doi: 10.1890/1051-0761(2001)011[0584:STISOL]2.0.CO;2

Corlett, R. T. (2007). The impact of hunting on the mammalian fauna of tropical Asian forests. Biotropica 39, 292–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7429.2007.00271.x

Courchamp, F., Angulo, E., Rivalan, P., Hall, R. J., Signoret, L., Bull, L., et al. (2006). Rarity value and species extinction: the anthropogenic Allee effect. PLoS Biol. 4:e415. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040415

Cunningham, A. A., Turvey, S. T., Zhou, F., Meredith, H. M., Guan, W., Liu, X., et al. (2016). Development of the Chinese giant salamander Andrias davidianus farming industry in Shaanxi Province, China: conservation threats and opportunities. Oryx 50, 265–273. doi: 10.1017/S0030605314000842

Drury, R. (2009). Reducing urban demand for wild animals in Vietnam: examining the potential of wildlife farming as a conservation tool. Conserv. Lett. 2, 263–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-263X.2009.00078.x

Duffy, R., St John, F. A. V., Büscher, B., and Brockington, D. (2016). Toward a new understanding of the links between poverty and illegal wildlife hunting. Conserv. Biol. 30, 14–22. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12622

Fa, J. E., Currie, D., and Meeuwig, J. (2003). Bushmeat and food security in the Congo Basin: linkages between wildlife and people’s future. Environ. Conserv. 30, 71–78. doi: 10.1017/S0376892903000067

Fauna and Flora International China Programme (2005). Action plan for implementing co-management in the Bawangling Nature Reserve and adjacent communities in Qingsong Township. Beijing: Flora International China Programme.

Gaillard, D., Liu, L., Haitao, S., and Shujin, L. (2017). Turtle soup: local usage and demand for wild caught turtles in Qiongzhong County, Hainan Island. Herpetol. Conserv. Biol. 12, 33–41.

Gale, D. (1955). The law of supply and demand. Math. Scand. 3, 155–169. doi: 10.7146/math.scand.a-10436

Gamborg, C., and Jensen, F. S. (2016). Wildlife value orientations among hunters, landowners, and the general public: a Danish comparative quantitative study. Hum. Dimens. Wildlife 21, 328–344. doi: 10.1080/10871209.2016.1157906

Golden, C. D., and Comaroff, J. (2015). Effects of social change on wildlife consumption taboos in northeastern Madagascar. Ecol. Soc. 20:41. doi: 10.5751/ES-07589-200241

Gong, S., Shi, H., Jiang, A., Fong, J. J., Gaillard, D., and Wang, J. (2017). Disappearance of endangered turtles within China’s nature reserves. Curr. Biol. 27, R170–R171. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.01.039

Gong, S., Wang, J., Shi, H., Song, R., and Xu, R. (2006). Illegal trade and conservation requirements of freshwater turtles in Nanmao, Hainan Province, China. Oryx 40, 331–336. doi: 10.1017/S0030605306000949

Greer, C. E., and Doughty, R. W. (1976). Wildlife utilization in China. Environ. Conserv. 3, 200–208. doi: 10.1017/S0376892900018609

Hinsley, A., Keane, A., St. John, F. A., Ibbett, H., and Nuno, A. (2019). Asking sensitive questions using the unmatched count technique: Applications and guidelines for conservation. Methods Ecol. Evol. 10, 308–319. doi: 10.1111/2041-210X.13137

Huber, T. (2012). “The Changing Role of Hunting and Wildlife in Pastoral Communities of Northern Tibet,” in Pastoral practices in High Asia: Agency of ‘development’ effected by modernisation, resettlement and transformation, ed. H. Kreutzmann (Dordrecht: Springer), 195–215. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-3846-1_11

Ingram, D. J., Cronin, D. T., Challender, D. W. S., Venditti, D. M., and Gonder, M. K. (2019). Characterising trafficking and trade of pangolins in the Gulf of Guinea. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 17:e00576. doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2019.e00576

Jones, S., Papworth, S., Keane, A. M., Vickery, J., and St John, F. A. V. (2020). The bean method as a tool to measure sensitive behaviour. Conserv. Biol. 2020:13607. doi: 10.1111/cobi.13607

Kamp, J., Oppel, S., Ananin, A. A., Durnev, Y. A., Gashev, S. N., Hölzel, N., et al. (2015). Global population collapse in a superabundant migratory bird and illegal trapping in China. Conserv. Biol. 29, 1684–1694. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12537

Kang, A., Xie, Y., Tang, J., Sanderson, E. W., Ginsberg, J. R., and Zhang, E. (2010). Historic distribution and recent loss of tigers in China. Integrat. Zool. 5, 335–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4877.2010.00221.x

Katuwal, H., Parajuli, K., and Sharma, S. (2016). Money overweighted the traditional beliefs for hunting of Chinese pangolins in Nepal. J. Biodivers. Endangered Species 4:10.4172. doi: 10.4172/2332-2543.1000173

Kong, D., Wu, F., Shan, P., Gao, J., Yan, D., Luo, W., et al. (2018). Status and distribution changes of the endangered Green Peafowl (Pavo muticus) in China over the past three decades (1990s−2017). Avian Res. 9:18. doi: 10.1186/s40657-018-0110-0

Kroutil, L. A., Vorburger, M., Aldworth, J., and Colliver, J. D. (2010). Estimated drug use based on direct questioning and open-ended questions: responses in the 2006 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 19, 74–87. doi: 10.1002/mpr.302

Liang, W., and Zhang, Z. (2011). Hainan peacock-pheasant (Polyplectron katsumatae): an endangered and rare tropical forest bird. Chin. Birds 2, 111–116. doi: 10.5122/cbirds.2011.0017

Liang, W., Cai, Y., and Yang, C. (2013). Extreme levels of hunting of birds in a remote village of Hainan Island, China. Bird Conserv. Int. 23, 45–52. doi: 10.1017/S0959270911000499

McDonald, R. I., Fielding, K. S., and Louis, W. R. (2014). Conflicting social norms and community conservation compliance. J. Nat. Conserv. 22, 212–216. doi: 10.1016/j.jnc.2013.11.005

Ministry of Ecology and Environment of China (2012). List of Protected Areas in Hainan Province. Beijing: Ministry of Ecology and Environment of China.

Nash, H. C., Wong, M. H. G., and Turvey, S. T. (2016). Using local ecological knowledge to determine status and threats of the Critically Endangered Chinese pangolin (Manis pentadactyla) in Hainan, China. Biol. Conserv. 196, 189–195. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2016.02.025

National People’s Congress of China (2020). Decision of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress to comprehensively prohibit the illegal trade of wild animals, break the bad habit of excessive consumption of wild animals, and effectively secure the life and health of the people. China. China: National People’s Congress of China.

Newing, H. (2010). Conducting research in conservation: social science methods and practice. Abingdon: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203846452

Nuno, A., and St. John, F. A. V. (2015). How to ask sensitive questions in conservation: A review of specialized questioning techniques. Biol. Conserv. 189, 5–15. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2014.09.047

Phelps, J., Biggs, D., and Webb, E. L. (2016). Tools and terms for understanding illegal wildlife trade. Front. Ecol. Environ. 14, 479–489. doi: 10.1002/fee.1325

Ribeiro, J., Bingre, P., Strubbe, D., and Reino, L. (2020). Coronavirus: Why a permanent ban on wildlife trade might not work in China. Nature 578, 217–217. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-00377-x

Rookmaaker, K. (2006). Distribution and extinction of the rhinoceros in China: review of recent Chinese publications. Pachyderm 40, 102–106.

Sandalj, M., Treydte, A. C., and Ziegler, S. (2016). Is wild meat luxury? Quantifying wild meat demand and availability in Hue, Vietnam. Biol. Conserv. 194, 105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2015.12.018

SFGA of China (2020). List of endangered and protected species of China (Amendment) (Change of pangolin protection level). China: SFGA of China.

Shairp, R., Veríssimo, D., Fraser, I., Challender, D., and MacMillan, D. (2016). Understanding urban demand for wild meat in Vietnam: implications for conservation actions. PLoS One 11:e0134787. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134787

Soewu, D. A., and Sodeinde, O. A. (2015). Utilization of pangolins in Africa: fuelling factors, diversity of uses and sustainability. Int. J. Biodivers. Conserv. 7, 1–10. doi: 10.5897/IJBC2014.0760

Thapar, V. (1996). “The tiger — road to extinction,” in The Exploitation of Mammal Populations, eds V. J. Taylor and N. Dunstone (Netherlands: Springer), 292–301. doi: 10.1007/978-94-009-1525-1_16

Turvey, S. T., Bryant, J. V., Duncan, C., Wong, M. H., Guan, Z., Fei, H., et al. (2017). How many remnant gibbon populations are left on Hainan? Testing the use of local ecological knowledge to detect cryptic threatened primates. Am. J. Primatol. 79:e22593. doi: 10.1002/ajp.22593

Turvey, S. T., Crees, J. J., and Di Fonzo, M. M. (2015a). Historical data as a baseline for conservation: reconstructing long-term faunal extinction dynamics in Late Imperial–modern China. Proc. R. Soc. B 282:20151299. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2015.1299

Turvey, S. T., Trung, C. T., Quyet, V. D., Nhu, H. V., Thoai, D. V., Tuan, V. C. A., et al. (2015b). Interview-based sighting histories can inform regional conservation prioritization for highly threatened cryptic species. J. Appl. Ecol. 52, 422–433. doi: 10.1111/1365-2664.12382

Turvey, S., Walsh, C., Hansford, J., Crees, J., Bielby, J., Duncan, C., et al. (2019). Complementarity, completeness and quality of long-term faunal archives in an Asian biodiversity hotspot. Philosop. Transact. B Biol. Sci. 374:217. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2019.0217

USAID Wildlife Asia (2018). Research study on consumer demand for elephant, pangolin, rhino and tiger parts and products in China (Chinese). Washington, D.C: USAID Wildlife Asia.

Van Der Heijden, P. G. M., Van Gils, G., Bouts, J., and Hox, J. J. (2000). A comparison of randomized response, computer-assisted self-interview, and face-to-face direct questioning: eliciting sensitive information in the context of welfare and unemployment benefit. Sociol. Methods Res. 28, 505–537. doi: 10.1177/0049124100028004005

Wadley, R. L., and Colfer, C. J. P. (2004). Sacred forest, hunting, and conservation in West Kalimantan. Indonesia. Hum. Ecol. 32, 313–338. doi: 10.1023/B:HUEC.0000028084.30742.d0

Wang, X., Zhang, K., Wang, Z., Ding, Y., Wu, W., and Huang, S. (2004). The decline of the Chinese giant salamander Andrias davidianus and implications for its conservation. Oryx 38, 197–202. doi: 10.1017/S0030605304000341

Wu, S., Liu, N., Zhang, Y., and Ma, G. (2004). Assessment of threatened status of Chinese pangolin. Chin. J. Appl. Environ. Biol. 10, 456–461.

Xu, L., Guan, J., Lau, W., and Xiao, Y. (2016). “An overview of pangolin trade in China,” in TRAFFIC Briefing Paper, (Cambridge: TRAFFIC).

Xu, Y., Lin, S., He, J., Xin, Y., Zhang, L., Jiang, H., et al. (2017). Tropical birds are declining in the Hainan Island of China. Biol. Conserv. 210, 9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2016.05.029

Yang, D., Dai, X., Deng, Y., Lu, W., and Jiang, Z. (2007). Changes in attitudes toward wildlife and wildlife meats in Hunan Province, central China, before and after the severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak. Integrat. Zool. 2, 19–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4877.2007.00043.x

Yang, L., Chen, M., Challender, D. W. S., Waterman, C., Zhang, C., Huo, Z., et al. (2018). Historical data for conservation: reconstructing range changes of Chinese pangolin (Manis pentadactyla) in eastern China (1970–2016). Proc. R. Soc. B 285:20181084. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2018.1084

Zhang, L., and Yin, F. (2014). Wildlife consumption and conservation awareness in China: a long way to go. Biodivers. Conserv. 23, 2371–2381. doi: 10.1007/s10531-014-0708-4

Zhang, T., Wu, Q., and Zhang, Z. (2020). Probable pangolin origin of SARS-CoV-2 associated with the COVID-19 outbreak. Curr. Biol. 30, 1346–1351. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.03.022

Zhang, X., Cowling, D. W., and Tang, H. (2010). The impact of social norm change strategies on smokers’ quitting behaviours. Tobacco Contr. 19, i51–i55. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.029447

Zhou, C., Xu, J., and Zhang, Z. (2015). Dramatic decline of the vulnerable Reeves’s pheasant Syrmaticus reevesii, endemic to central China. Oryx 49, 529–534. doi: 10.1017/S0030605313000914

Keywords: China, conservation, game meat, Hainan peacock-pheasant, hunting, pangolin, social norm, wildlife trade

Citation: Wang Y, Leader-Williams N and Turvey ST (2021) Exploitation Histories of Pangolins and Endemic Pheasants on Hainan Island, China: Baselines and Shifting Social Norms. Front. Ecol. Evol. 9:608057. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2021.608057

Received: 18 September 2020; Accepted: 22 February 2021;

Published: 12 March 2021.

Edited by:

Yan Zeng, Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), ChinaReviewed by:

Hari Prasad Sharma, Tribhuvan University, NepalCopyright © 2021 Wang, Leader-Williams and Turvey. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yifu Wang, eXczOTNAY2FtLmFjLnVr

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.