95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

POLICY BRIEF article

Front. Ecol. Evol. , 18 December 2019

Sec. Conservation and Restoration Ecology

Volume 7 - 2019 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2019.00491

This article is part of the Research Topic Conservation and Management of Large Carnivores - Local Insights for Global Challenges View all 20 articles

The relevance of the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS) for large carnivores is on the increase. Its appendices currently feature polar bear, Gobi bear, African wild dog, lion, leopard, snow leopard, and cheetah. This increased involvement raises various issues and debates concerning, inter alia, the value added by the CMS as compared to other treaties; the scope of the CMS in relation to its definition of “migratory species”; and the Convention's implications for the sustainable use of listed large carnivores. We present these and similar emerging questions within their broader context, provide beginnings of answers, and outline an agenda for further research. We further highlight the need for improved interpretive guidance on aspects of the Convention's legal text and its implications for sustainable use.

The 1979 Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS) (to which 129 countries and the European Union are currently parties) prescribes particular conservation measures for “endangered” migratory species listed in its Appendix I, and fosters targeted international cooperation through species-specific subsidiary treaties, memoranda of understanding, or other arrangements—primarily for species listed in its Appendix II.

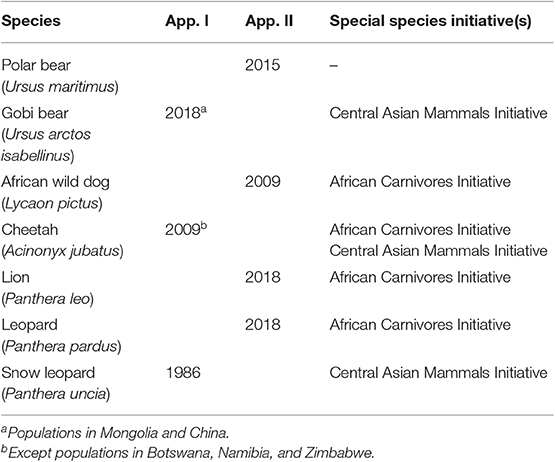

The practice of the CMS's principal decision-making body, the Conference of the Parties (COP), has been characterized by flexibility and pragmatism (Bowman et al., 2010; Lewis and Trouwborst, 2017), enabling the listing of several species that are not migratory in the most typical sense. These include seven large carnivore (sub)species from Africa, Asia and the Arctic, i.e., polar bear (Ursus maritimus), Gobi bear (Ursus arctos isabellinus), African wild dog (Lycaon pictus), lion (Panthera leo), leopard (Panthera pardus), snow leopard (Panthera uncia), and cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus). Three of these feature in Appendix I, four in Appendix II, and most were added during the fourth decade since the Convention's adoption (Table 1) [“Large carnivores” are understood here as species in the Carnivora order with an average adult biomass of at least 15 kilograms, and not including pinnipeds (Ripple et al., 2014)—although, notably, several pinnipeds are also CMS-listed].

Table 1. Large carnivore (sub)species covered by CMS appendices and SSIs, with years in which their listings entered into effect.

To date, no CMS subsidiary treaties or memoranda of understanding have been developed for any of these large carnivores, but six of them are covered by at least one of two relevant “Special Species Initiatives” (SSIs). One is the Central Asian Mammals Initiative (CAMI), a comparatively informal and flexible cooperative arrangement involving governmental and non-governmental stakeholders. Launched in 2014, CAMI covers snow leopard and cheetah along with various large herbivores. Gobi bear and leopard are likely future additions. The other SSI is the African Carnivores Initiative (ACI), established in 2017 under joint auspices of the CMS and the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), and providing a cooperative umbrella for African wild dogs and (African) lions, leopards, and cheetahs. Some consideration has also been given to the CMS providing secretariat services for the 1973 International Agreement on the Conservation of Polar Bears—a treaty falling outside the current CMS framework, but with which the need for cooperation has received recent emphasis (CMS Secretariat, 2018). Notably, the scope of CMS involvement has occasionally extended to non-listed large carnivores. For instance, a 2008 COP Resolution calls on “Parties and Range States to enhance mutual transboundary cooperation for the conservation and management of tigers and other Asian big cat species” [COP Resolution 9.22, 2008 (Rev. COP12)].

The CMS's increased involvement in large carnivore conservation has generated various issues and debates. The 2017 proposals to list lion and leopard in particular met with an unusual degree of opposition by several range states, i.e., South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zimbabwe (Hodgetts et al., 2018). Disagreement largely centered on the scope of the Convention's definition of “migratory species.” However, the opposition appeared to be driven also (or even primarily) by underlying concerns over potential future impediments for the sustainable use of these species—including through the perceived interplay between CMS and CITES listing (IISD, 2017). A related question concerns the value added by CMS listing vis-à-vis other international legal regimes of relevance to the large carnivores involved. These issues may again arise at the next COP meeting (in February 2020), which will also consider whether to list the jaguar (Panthera onca) in the Convention's appendices (UNEP/CMS/COP13/Doc.27.1.2). In light of the above, we concisely explore these and other emerging issues concerning the CMS's application to large carnivores.

According to the Convention text, the term “migratory species” covers the population or part of the population of any wild animal species or lower taxon “a significant proportion of whose members cyclically and predictably cross one or more national jurisdictional boundaries” [Article I(1)(a)]. According to interpretive guidance adopted in 1988 (and recently reaffirmed), “cyclically” relates to a cycle “of any nature, such as astronomical (circadian, annual, etc.), life or climatic, and of any frequency,” and “predictably” implies that a phenomenon “can be anticipated to recur in a given set of circumstances, though not necessarily regularly in time” [COP Resolution 2.2, 1988; now Resolution 11.33 (Rev. COP12)]. Whereas listing in the Convention's appendices is reserved for “migratory species” as just defined, other fauna may still fall within the broader category of species “members of which periodically cross one or more national jurisdictional boundaries,” regarding whom CMS parties are encouraged to conclude targeted agreements [Article IV(4)]. In light of this, and the COP's broad interpretation of “migratory species,” the Convention's scope may be best understood as encompassing transboundary species conservation rather than only migratory species in the classical sense (Lewis and Trouwborst, 2017).

The COP's listing record itself has been pragmatic rather than dogmatic. Various species have been listed despite the cyclical and predictable nature of their transboundary movements perhaps not being immediately apparent—including several of the aforementioned large carnivores. Of particular interest is the most recent (2017) COP meeting, which resulted in the listing of lion, leopard, and Gobi bear. The proposals to list lion and leopard on Appendix II met with fierce opposition from several range states (mentioned above), which contended that neither carnivore satisfied the CMS definition of a “migratory species.” This dispute could only be resolved through voting—a departure from the ordinary CMS practice of consensus-based decision-making. Historically, disputes over listing proposals have occasionally been resolved by excluding particular populations from listing. However, this approach was rejected for lions and leopards because the populations of the range states in question are not biologically distinct from contiguous populations (Hodgetts et al., 2018). It should further be noted that (i) both listing proposals described in detail how the “migratory species” definition was met, referring inter alia to dispersal, movements following herbivore migrations, movements resulting from climatic conditions, and the large number of transboundary lion and leopard populations; (ii) the previous COP had already expressly acknowledged that lions are a “migratory species” for the purposes of the Convention (CMS COP Resolution 11.32, 2014); (iii) the proposals were adopted with only four and eight votes against, respectively; and (iv) as Appendix II listings, these decisions do not oblige range states to adjust their domestic legislation.

The Gobi bear proposal was addressed in the same meeting session, but the contrast is stark. Despite involving a legally far-reaching Appendix I listing, the documented evidence of transboundary Gobi bear movements was limited to a single documented return trip by a bear across the Chinese border, with the species' known range otherwise being confined to Mongolia. The proposal itself frankly acknowledges that “if a cyclical or predictable migration/movement occurs, it hasn't yet been documented” (UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.1.5, 2017). Nevertheless, not a single party questioned or objected to the proposal, which was adopted by consensus.

An issue that remains under-explored is the relevance of the precautionary principle (or precautionary approach) in cases like the Gobi bear's, where uncertainty exists regarding a (sub)species' or population's transboundary movements or transboundary occurrence. Current guidance on species listing provides that “by virtue of the precautionary approach and in case of uncertainty regarding the status of a species, the Parties shall act in the best interest of the conservation of the species concerned [and] adopt measures that are proportionate to the anticipated risks to the species” [CMS COP Resolution 11.33 (Rev. COP12)]. A related question concerns the CMS's role where a species or population is not currently transboundary but used to be, with international cooperation a potential aid to its recovery. A case in point, other than the Gobi bear, is the Asiatic lion, i.e., the Panthera leo leo population in India. Notwithstanding Asiatic lions' confinement to a single country, the COP in 2014—when Asiatic lion was still considered a separate subspecies, P.l. persica—expressly acknowledged that Panthera leo “and all its evolutionarily significant constituents, including Panthera leo persica, satisfy the Convention's definition of ‘migratory species”' (CMS COP Resolution 11.32, 2014).

Notably, South Africa and Uganda submitted reservations [per CMS Article XI(6)] to ensure that the listing of lion and leopard would not apply to them. Zimbabwe also attempted to do so, but its reservations missed the prescribed deadline and were ultimately declared invalid (Lewis, 2019).

Finally, it should be noted that CMS listing excludes captive populations, but that precedent exists for listing populations that have been reintroduced to the wild (using captive populations) and managed (Hodgetts et al., 2018).

The impasse that arose in 2017 related specifically to listing lion and leopard in the CMS appendices, not the Convention's support for these species' conservation per se. The COP's decisions regarding the ACI were adopted by consensus. Moreover, despite their disagreement over CMS listing, the African lion's range states had previously agreed that “CMS can provide a platform to exchange best conservation and management practices; support the development, implementation and monitoring of action plans; promote the standardization of data collection and assessments; facilitate transboundary cooperation; and assist in the mobilization of resources” (2016 Entebbe Communiqué, African Lion Range States Meeting).

Several factors indicate that the definition of “migratory species” was not the principal reason for certain range states' opposition to the CMS listing of lion and leopard. If it were, these parties could have been expected to initiate a more generic debate around the interpretation in Resolution 11.33—which they did not (Hodgetts et al., 2018). Other pointers include the lack of opposition to the Gobi bear's listing, and the fact that Tanzania, while opposing the listing of lion and leopard, itself proposed the listing of the chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes)—hardly a more obviously “migratory” species—at the very same COP meeting.

The reluctance of some states to include leopard and lion on CMS Appendix II appears to stem (at least in part) from the possibility of a future uplisting to Appendix I—potentially entailing serious obstacles to these species' management and utilization (Hodgetts et al., 2018; Trouwborst et al., 2019). All of the states in question have statutory mechanisms that can be, or are automatically, used to protect CMS Appendix I-listed species. However, the precise implications of legal protection differ from one state to another, as do the species in respect of which trophy hunting is currently permitted. In this light, further exploration is warranted of the degree to which an Appendix I listing would affect, inter alia, parties' discretion regarding trophy hunting and the management of damage-causing animals. Per CMS Article III(5):

“Parties that are Range States of a migratory species listed in Appendix I shall prohibit the taking of animals belonging to such species. Exceptions may be made to this prohibition only if:

a) the taking is for scientific purposes;

b) the taking is for the purpose of enhancing the propagation or survival of the affected species;

c) the taking is to accommodate the needs of traditional subsistence users of such species; or

d) extraordinary circumstances so require;

provided that such exceptions are precise as to content and limited in space and time. Such taking should not operate to the disadvantage of the species.”

“Taking” includes “taking, hunting, fishing, capturing, harassing, deliberate killing, or attempting to engage in any such conduct” [Article I(1)(i)].

Aspects of the definition of “taking” (in particular, the meaning of “harassing” and “deliberate”) would benefit from interpretive guidance (Lewis, 2019). This notwithstanding, Article III requires apparently far-reaching prohibitions, subject to prima facie narrow exception possibilities (Bowman et al., 2010; Trouwborst, 2014; Lewis, in press). The precise scope of these exception possibilities remains unclear. In practice, parties have reported granting exceptions for a variety of reasons not expressly mentioned in Article III(5) (e.g., public safety and prevention of property damage) (Lewis, in press). For present purposes, particularly pertinent questions include to what extent and under what conditions trophy hunting can fit the “purpose of enhancing the propagation or survival of the affected species” and the scope of the “extraordinary circumstances” clause (Trouwborst, 2014; Lewis, in press).

The COP's adoption of comprehensive interpretive guidance on Article III(5) would alleviate current ambiguities concerning the scope for lethal management and sustainable use of Appendix I-listed large carnivores. In 2020, the COP will consider several draft documents on “Application of Article III of the Convention” (UNEP/CMS/COP13/Doc.21). These express concern regarding international trade in Appendix I species, but do not resolve the interpretive uncertainties associated with Article III. The CMS Secretariat has additionally prepared legislative guidance materials on implementing Article III(5) (UNEP/CMS/COP13/Doc.22). However, the interpretations proposed therein haven't been endorsed by the COP and fail to answer the abovementioned questions surrounding trophy hunting. Ideally, the COP should therefore request that the Secretariat further develop its interpretive guidance on Article III(5) and present this for adoption at the COP's fourteenth meeting.

Notably, the COP has been willing to exclude distinct populations from Appendix I if sustainable taking is possible (Trouwborst et al., 2017). For instance, it recognized this possibility for the Saker falcon, Falco cherrug (CMS COP Resolution 10.28, 2011) and has subsequently promoted the development of an adaptive management framework to improve this species' conservation through, inter alia, regulated sustainable use (CMS COP Resolution 11.18, 2014). This illustrates the Convention's ability to take a pragmatic approach toward consumptive use and assist states in coordinating the taking of animals from transboundary populations to ensure that this is sustainable.

Beyond the CMS's own restrictions on taking, some parties fear that a species' CMS listing may be used to leverage its CITES listing, resulting in restrictions on international trade (IISD, 2017). CMS listing decisions tend to consider CITES-compatibility. This explains, for instance, why several cheetah populations were excluded from the species' CMS Appendix I listing (Trouwborst et al., 2017). The CMS's influence on CITES decisions is less obvious. CITES's mandate is distinct from that of the CMS, its listing criteria make no explicit call for coherence with other international fora [CITES Resolution 9.24 (Rev. COP17)], and various species remain on CITES Appendix II despite their CMS Appendix I status. Nevertheless, the interplay between these two listing regimes warrants future exploration.

Concerns have also arisen about whether CMS listing is appropriate for large carnivores already covered by other cooperative arrangements. The COP has agreed that listing proposals must explain the value that listing would add to existing conservation efforts [CMS Resolution 11.33 (Rev. COP12)]. The Convention's Scientific Council has also stressed this—for instance, in its comments on the feasibility of proposing the tiger (Panthera tigris) for inclusion in CMS Appendix I (UNEP/CMS/Conf.10.12). The tiger is already the focus of significantly more international cooperation than, for instance, the dhole or Asiatic wild dog (Cuon alpinus). A draft Appendix I listing proposal for the dhole was considered by the Scientific Council in 2007 (CMS/ScC14/Doc.13), but a formal proposal has not yet been submitted to the COP (see also CMS/StC.23/Doc.14; Trouwborst, 2015). One concern is the low number of CMS parties within the dhole's current range—which is a similar concern for tiger (UNEP/CMS/ScC16/REPORT) and polar bear, but has not stood in the way of the latter's listing.

One argument in favor of CMS listing may be that other international fora do not address all of the threats facing a particular species. For instance, CITES lists 24 species of large carnivore (Trouwborst, 2015), but its mandate is limited to combating unsustainable international trade. The CMS can therefore potentially complement CITES's efforts by coordinating responses to other anthropogenic threats. Indeed, this was the thinking underlying the establishment of the CITES-CMS African Carnivores Initiative.

Where a species is already addressed by bilateral arrangements and/or multilateral initiatives with limited geographic scope, the CMS can potentially provide overarching coordination between these and foster collaboration with additional states. The latter may, for instance, be necessary if existing frameworks exclude portions of a species's range. Regrettably, the CMS itself suffers significant membership gaps, limiting its impact in some regions. Notable absentees include Canada, China, Mexico, the Russian Federation and the United States (Hensz and Soberón, 2018). However, the Convention does not prohibit non-parties from participating in its initiatives or ancillary treaties, and there are examples of such participation occurring.

Finally, although the CMS's provisions emphasize the responsibilities of range states, the Convention also seemingly has a role in facilitating cooperation with non-range states. For instance, polar bear conservation has long been the focus of various arrangements between range states, including a dedicated treaty. However, Norway's proposal to list this species on CMS Appendix II argued that non-Arctic states contribute to several of the threats facing polar bears, and that the CMS provides an appropriate mechanism to facilitate cooperation in this regard (UNEP/CMS/COP11/Doc.24.1.11/Rev.2). The listing was ultimately adopted, but several stakeholders were skeptical about its value and doubted the role that the Convention can realistically play in addressing such threats as climate change (UNEP/CMS/COP11/Proceedings). Debates such as this spotlight important questions about the types of conservation challenges that species-based treaties are best-equipped to tackle and the issues toward which they should be channeling their limited resources.

As regards the transboundary dimensions of the conservation and sustainable use of the world's large carnivores, the CMS clearly has a useful role to play. In the further development of this role, keen attention should be paid to determining where the Convention might add most value, in order to make efficient use of scarce resources and avoid duplication of efforts. It would also be conducive to prepare and adopt further interpretive guidance on the application of Article III(5), clarifying what scope exists for the lethal management and sustainable use of large carnivores listed in Appendix I. By highlighting and exploring these and other issues which warrant attention, we hope that our analysis can contribute to optimizing the future evolution of the CMS within its unique niche in international wildlife law and policy, to the benefit of large carnivores and biodiversity at large.

ML and AT contributed equally to study design, analysis, and writing of the manuscript.

AT was funded by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (grant no. 452-13-014).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Bowman, M., Davies, P., and Redgwell, C. (2010). Lyster's International Wildlife Law, 2nd Edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

CMS Secretariat (2018, February 9). CMS Executive Secretary attends polar bear range states' meeting. CMS News. Available online at: https://www.cms.int/en/news/cms-executive-secretary-attends-polar-bear-range-states-meeting (accessed December 10, 2019).,

Hensz, C. M., and Soberón, J. (2018). Participation in the Convention on Migratory Species: a biogeographic assessment. Ambio 47, 739–746. doi: 10.1007/s13280-018-1024-0

Hodgetts, T., Lewis, M., Bauer, H., Burnham, D., Dickman, A., Macdonald, E., et al. (2018). Improving the role of global conservation treaties in addressing contemporary threats to lions. Biodivers. Conserv. 27, 2747–2765. doi: 10.1007/s10531-018-1567-1

IISD (2017). Summary of The Twelfth Meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals. Earth Negotiations Bulletin, Vol. 18.

Lewis, M. (2019). Deciphering the complex relationship between AEWA's and the Bonn Convention's respective exemptions to the prohibition of taking. J. Int. Wildlife Law Policy. doi: 10.1080/13880292.2019.1672945. [Epub ahead of print].

Lewis, M. (in press). Sustainable use and shared species: navigating AEWA's constraints on the harvest of African-Eurasian migratory waterbirds. Georgetown Environ. Law Rev.

Lewis, M., and Trouwborst, A. (2017). “Bonn Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals 1979,” in Multilateral Environmental Treaties, eds M. Fitzmaurice, A. Tanzi, and A. Papantoniou (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 25–34.

Ripple, W. J., Estes, J. A., Beschta, R. L., Wilmers, C. C., Ritchie, E. G., Hebblewhite, M., et al. (2014). Status and ecological effects of the world's largest carnivores. Science 343:1241484. doi: 10.1126/science.1241484

Trouwborst, A. (2014). Aussie jaws and international laws: the Australian shark cull and the Convention on Migratory Species. Cornell Int. Law J. Online 2, 41–46.

Trouwborst, A. (2015). Global large carnivore conservation and international law. Biodiv. Conserv. 24, 1567–1588. doi: 10.1007/s10531-015-0894-8

Trouwborst, A., Lewis, M., Burnham, D., Dickman, A., Hinks, A., Hodgetts, T., et al. (2017). International law and lions (Panthera leo): understanding and improving the contribution of wildlife treaties to the conservation and sustainable use of an iconic carnivore. Nat. Conserv. 12, 83–128. doi: 10.3897/natureconservation.21.13690

Keywords: biodiversity conservation, Convention on Migratory Species (CMS), international law, large carnivores, leopard (Panthera pardus), lion (Panthera leo), polar bear (Ursus maritimus), sustainable use

Citation: Lewis M and Trouwborst A (2019) Large Carnivores and the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS)—Definitions, Sustainable Use, Added Value, and Other Emerging Issues. Front. Ecol. Evol. 7:491. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2019.00491

Received: 22 August 2019; Accepted: 03 December 2019;

Published: 18 December 2019.

Edited by:

David Jack Coates, Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (DBCA), AustraliaReviewed by:

Attila D. Sándor, University of Agricultural Sciences and Veterinary Medicine of Cluj-Napoca, RomaniaCopyright © 2019 Lewis and Trouwborst. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Arie Trouwborst, YS50cm91d2JvcnN0QHRpbGJ1cmd1bml2ZXJzaXR5LmVkdQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.