- 1Department of Biological Sciences, Georgetown University, Washington, DC, United States

- 2Department of Biological Sciences, University of Denver, Denver, CO, United States

Anthropogenic nutrient inputs into native ecosystems cause fluctuations in resources that normally limit plant growth, which has important consequences for associated foodwebs. Such inputs from agricultural and urban habitats into nearby natural systems are increasing globally and can be highly variable. Despite the global increase in anthropogenically-derived nutrient inputs into native ecosystems, the consequences of variation in subsidy amount on native plants and their associated foodwebs are poorly known. Salt marshes represent an ideal system to address the differential impacts of nutrient inputs on ecosystem and community dynamics because human development and other anthropogenic activities lead to recurrent introductions of nutrients into these natural systems. Previously, we have found in manipulative experiments that arthropod abundance increases in response to nutrient enrichment, with predators being the trophic group most strongly affected. We conducted a survey of Atlantic coastal Spartina marshes to test whether such local responses are indicative of responses at a landscape level. We examined the most abundant arthropod species associated with Spartina coastal marshes that receive variable amounts of anthropogenic nitrogen, and tested how this response varied across different arthropod functional groups (herbivores, epigeic feeders, and predators). Similar to what we found at a local scale, nutrient subsidies alter the trophic structure of the arthropod assemblage by changing the relative abundances of various feeding groups. Variable responses among predators to nitrogen density could be partly explained by diet breadth (e.g., generalists vs. specialists). Herbivores had a negative response to increasing plant nitrogen density; specialist predators tracked their herbivore prey and thus also responded negatively to nitrogen density. However, generalists were not negatively affected by nitrogen density and indeed some generalist predators responded positively to nitrogen density. Thus, the overall predator-to-herbivore ratio was also positively associated with nitrogen density. Our research helps us to understand how long-term nutrient enrichment of native ecosystems by human activities affects arthropod assemblages and foodweb dynamics.

Introduction

Natural and anthropogenic inputs of nutrients (e.g., nitrogen) into native ecosystems often promote fluctuations in the availability of resources that normally limit plant growth (Robinson, 1994; Inouye and Tilman, 1995; Siemann, 1998; Haddad et al., 2000). Such inputs from agricultural and urban habitats into nearby natural systems are increasing globally and can be highly variable (Vitousek et al., 1997; Tilman, 1999; Boyer et al., 2002; Mayer et al., 2002; Valiela and Bowen, 2002; Valiela and Cole, 2002). Nutrient inputs promote changes in primary productivity and plant diversity that in turn can have important consequences for associated food-webs (Polis and Hurd, 1996; Polis et al., 1997a,b, 1998; Huxel and McCann, 1998; Haddad et al., 2000; Holmgren et al., 2001). Inputs of limiting nutrients (e.g., nitrogen) often concomitantly affect plant species richness, plant species composition, primary productivity, and plant tissue quality (C:N content) and determining their independent effects on the associated arthropod assemblage can be experimentally daunting (Kirchner, 1977; Siemann, 1998; Haddad et al., 2000). By working in natural plant monocultures (e.g., cordgrass-dominated coastal wetlands) the task is somewhat simplified because the cascading effects of nutrient subsidies on consumers will be driven largely by changes in primary productivity and plant nutrition (see Denno et al., 2002).

Despite the global increase in anthropogenically-derived nutrient inputs into native ecosystems, such as salt marshes, the consequences of variation in nutrient subsidies on native plants and their associated foodwebs are poorly known. Many researchers have tested the effects of nutrient subsidies on salt marshes in manipulative experiments (e.g., Valiela et al., 1978; Gratton and Denno, 2003; Wimp et al., 2010; Deegan et al., 2012; Murphy et al., 2012). For example, we have found that arthropod abundance increases in response to experimental nutrient enrichment, with predators being the trophic group most strongly affected (Wimp et al., 2010; Murphy et al., 2012). However, whether these results are consistent with observations from un-manipulated habitats across large geographic areas is unknown. Additionally, most of the studies that have examined the impacts of nitrogen inputs on salt marsh ecosystems have only been conducted using a small range of nitrogen input levels (often just a single level). In reality, salt marshes experience a wide range of nitrogen input levels, and higher levels of nitrogen can negatively affect plant producers. For example, excess nitrogen in the soil can lead to higher soil salinity, with negative effects on the plant. Excess nitrogen can also lead to a decrease in the root:shoot ratio, which can cause the plants to lodge or fall over because they are top-heavy (Deegan et al., 2012). Recently Wigand et al. (2018) demonstrated that in nutrient-enriched tidal creeks, soil shear strength in Spartina plots was significantly lower than in unmanipulated reference creeks and that these decreases in soil strength likely cause channel bank failures when Spartina plants collapse into tidal creeks. Such negative effects on plants may in turn impact herbivores. Finally, while our previous data demonstrates a positive effect of nutrient enrichment on higher trophic levels (Wimp et al., 2010; Murphy et al., 2012), such positive effects may describe a narrow set of circumstances. For instance, it is possible that the relationship between nutrient enrichment and higher trophic level consumers is only positive until a threshold is reached, and additional inputs of nitrogen will have no further effect. Additionally, the positive relationship may also only be possible when recruitment from nearby un-manipulated habitat is possible, which would mean that this pattern would only occur in experimental settings (e.g., manipulated plots nested within un-manipulated habitat) and not in marshes that are affected by widespread anthropogenic disturbance.

While bottom-up impacts of nitrogen addition may affect herbivore density and herbivory (Bertness et al., 2008; He and Silliman, 2015, 2016), top-down effects from predators may also limit herbivore populations. Previous studies have found that the impacts of nutrient addition on arthropod biomass and diversity are stronger for higher trophic levels (Wimp et al., 2010; Murphy et al., 2012). Thus, the positive response of herbivores to nutrient enrichment may eventually be checked by higher trophic level predators and parasites. It is unclear how higher trophic level predators and parasites may respond to nutrient enrichment across a wide range of nutrient enrichment levels, or within a larger spatial context. Because many arthropod predators gain not only additional prey, but also increasingly complex plant structure with higher levels of nutrient enrichment, this may diminish intraguild predation and cannibalism (Langellotto and Denno, 2006). Thus, the combined effects of additional prey resources and reduced competition/intraguild predation/cannibalism among predators may lead to a sustained positive response of predators/parasites to nutrient enrichment.

Increasing nitrogen inputs from anthropogenic sources are a common problem across a wide array of ecosystems, but one ecosystem that is particularly threatened by nitrogen inputs is coastal salt marshes where urbanization and agriculture are increasing nutrient runoff and nitrogen availability (Bertness et al., 2002, 2004). Land development and agriculture are jeopardizing coastal wetlands at an alarming rate, and one of the major threats is nitrogen runoff from neighboring anthropogenic sources, which alters vegetation dynamics, promotes the incursion of invasive species, and increases nitrogen availability (Bertness et al., 2002, 2004). An estimated 50% of the variation in nitrogen availability in Spartina marshes is explained by shoreline development such as housing developments and agriculture (Bertness et al., 2002). Because Spartina is nitrogen-limited, particularly in high-marsh habitats, nitrogen subsidies (natural and anthropogenic) result in dramatic increases in biomass, plant nitrogen content, plant architecture, and detritus (Mendelssohn, 1979a,b; Bertness et al., 2002; Denno et al., 2002; Gratton and Denno, 2003). The nitrogen-sensitive assemblage of arthropods associated with Spartina marshes (Denno et al., 2003; Huberty and Denno, 2006a,b) provides an ideal opportunity to study the food-web consequences of nitrogen subsidies at a large spatial scale. We compared the arthropod assemblage among Atlantic coastal Spartina marshes receiving variable amounts of anthropogenic nitrogen and at varying distances from potential upland N sources. We selected study marshes so that we could compare nearby marshes at similar latitudes that had different levels of nutrient inputs due to human development and agriculture. We predicted that if our results from our manipulated plot-experiments (Wimp et al., 2010; Murphy et al., 2012) accurately represent ecosystem-wide responses at greater geographic scales, then arthropod density should be greater in productive marshes that receive elevated subsidies of allochthonous nitrogen compared to more pristine marshes, and that the response should be stronger for higher trophic levels.

Methods

Study System

The perennial cordgrass Spartina alterniflora (now reclassified as Sporobolus alterniflorus, but hereafter referred to as Spartina) dominates the vegetation of Atlantic coastal marshes where it grows in the intertidal zone (Redfield, 1972; Bertness, 1991). Many marshes are characterized by large, pure expanses of Spartina that directly abut upland habitats, either natural upland vegetation or agricultural and urban habitats (Warren and Niering, 1991; Bertness et al., 2002, 2004). Most nitrogen that is delivered to coastal waters and wetlands in the US derives from non-point sources, such as agriculture and atmospheric deposition (Howarth et al., 1996); in the Mid-Atlantic region agriculture is the dominant source of nitrogen to natural systems (Boyer et al., 2002). As terrestrially-derived nitrate flows downstream from anthropogenic sources, about one quarter of the nitrogen is intercepted by coastal wetlands (e.g., Spartina marshes) before it is able to reach open waters (Valiela and Cole, 2002). Nitrogen that is retained in the marsh is incorporated into plant biomass, denitrified, or buried in marsh sediments (Valiela and Teal, 1979; Denno et al., 2002; Valiela and Cole, 2002).

Spartina is a foundation species that serves as the only host plant for a variety of insect herbivores in several feeding guilds including sap-feeders, free-living folivores, stem borers, and leaf miners (Denno, 1977; Stiling and Strong, 1983; Denno et al., 2003, 2005). We were able to capitalize on a wealth of life-history, mesocosm feeding trials, and stable isotope information in this exhaustively studied system in order to categorize the functional roles of the arthropod species found in Spartina (e.g., Dobel et al., 1990; Denno et al., 2002, 2003; Finke and Denno, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006; Gratton and Denno, 2003; Huberty and Denno, 2006a; Langellotto and Denno, 2006; Lewis and Denno, 2009; Wimp et al., 2010, 2013, 2019). Furthermore, previous studies have established the relative degree of habitat and feeding specialization for the dominant species (Denno, 1976, 1977, 1980; Wimp et al., 2013) and trophic interactions among the dominant species (Döbel and Denno, 1994; Finke and Denno, 2002; Denno et al., 2003, 2004, 2005; Ferrenberg and Denno, 2003). Sap-feeders are numerically dominant while free-living folivores, borers, and miners are less common (Denno et al., 2005). Of the sap-feeders, planthoppers (Prokelisia dolus and P. marginata) are the most abundant (Denno et al., 2000). Many herbivores show remarkable increases on N-subsidized Spartina due to enhanced colonization, fecundity and survival (Vince et al., 1981; Denno et al., 2002, 2003). Certain herbivores respond exclusively to increases in plant nitrogen content (N-sensitive “specialists” like P. marginata), whereas other species respond specifically to increases in plant biomass (several sap-feeders) (Huberty and Denno, 2006a,b). Overall, herbivores on Spartina are very responsive to nitrogen-induced changes in plant quality and biomass.

Spartina also has a rich assemblage of associated detritivores and algivores (collectively described as “epigeic feeders”) from a variety of feeding guilds such as grazers, shredders, algal, and fungal feeders (Wimp et al., 2013). Nitrogen-loading promotes increased abundance and diversity of detritivores in Spartina and other systems, both as a consequence of increased detrital biomass and quality (%N) (Settle et al., 1996; Halaj and Wise, 2002).

Spartina also hosts a diversity of natural enemies for herbivores and epigeic prey, including invertebrate predators and parasitoids, but predators are a far more important source of mortality than parasitoids on mid-Atlantic marshes (Döbel and Denno, 1994). The predator assemblage includes both generalist predators (web-building and hunting spiders) and specialist predators (e.g., the mirid Tytthus vagus) (Döbel and Denno, 1994; Finke and Denno, 2002; Denno et al., 2003). Top carnivores are voracious intraguild predators and include hunting spiders (Pardosa littoralis and Hogna modesta) and katydids (Conocephalus spartinae) that feed on herbivores, detritivores, specialist predators as well as each other (Finke and Denno, 2003; Denno et al., 2004; Matsumura et al., 2004). Hunting spiders, such as Pardosa, inflict high mortality on herbivores, an effect that can cascade to basal resources such as biomass and tiller production (Finke and Denno, 2002; Denno et al., 2005). However, intraguild predation reduces the overall effectiveness of the predator complex in suppressing herbivore populations and thus dampens trophic cascades (Denno et al., 2003, 2004; Finke and Denno, 2004).

Survey Design and Methods

We selected 14 marshes along the mid-Atlantic coast between Maine and Virginia (Figure 1; Supplement 1). We chose these marshes such that they abutted large expanses of native upland vegetation (<5 km away) or were bordered by development or agriculture that would lead to an increase in nitrogen inputs (see Bertness et al., 2002). Initially, we chose marshes that spanned a gradient of minimally to heavily impacted based on proximity to upland development and rate of tidal flushing. Thus, according to these criteria, Virginia Coastal Reserve (VA), Great Bay Marsh (NJ), and Plum Island LTER (MA) were considered minimally impacted; Delaware Seashore State Park (DE), Caumsett State Historic Park (NY), Foxhill Salt Marsh (RI), Colt State Park (RI), Fogland Nature Preserve (RI), and Awcomin Marsh (NH) were considered moderately impacted; and Horseshoe Cove (NJ), Little Creek Wildlife Area (DE), Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge (NY), Urban Forestry Center (NH), and Fore River Sanctuary (ME) were considered heavily impacted marshes. However, we found that these criteria did not adequately capture nitrogen loading into each marsh and were highly subjective. We therefore used nitrogen density as a measure of nitrogen loading into each marsh since it represents a non-subjective measure and also captures variation in the way that marshes in different locations respond to nutrient addition. Specifically, in a previous study (Murphy et al., 2012) we found that Spartina growing in one marsh responded to nutrient manipulation with an increase in plant percent nitrogen, while Spartina growing in a different marsh responded with an increase in biomass (Murphy et al., 2012). Because nitrogen density captures both measures simultaneously (percent nitrogen and biomass), it allows us to make comparisons across different marshes. In each marsh we aimed to establish 4 square plots (10 m2 each and separated by 50 m) along 3 replicated transects (separated by 100 m) running seaward from the upland, for a total of 12 plots per marsh. However, some marshes were too small to accommodate 12 plots and so these marshes had fewer plots (please see Supplement 1 for exact sample sizes); there were 151 plots overall across 14 marshes. We conducted the survey between August 13 and 28, 2012 and started surveying marshes in the south and worked our way north to help control for phenology so that we sampled each site during peak biomass. In each plot we sampled: (1) aboveground and belowground biomass of Spartina, (2) biomass of detritus, (3) N-content of Spartina, and (4) the density of all arthropods.

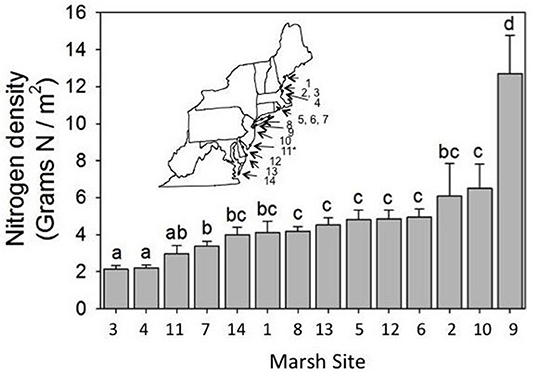

Figure 1. Mean nitrogen density varied across marshes [F(13, 136) = 12.73, P < 0.0001]. Inset shows approximate locations of the study marshes, which are numbered from north to south. We found no trend in nitrogen density with latitude [F(1, 14.6) = 2.62, P = 0.15]. Specific information about marsh study locations and sample size can be found in Supplement 1. Error bars show standard errors of the means. Asterisk denotes site of our plot-level manipulations in NJ, and letters indicate significant differences.

Plant Samples

We measured plant biomass and height using 0.047 m2 quadrats (Denno et al., 2002) by sorting the quadrat samples into live and dead plant material and measuring the height of living culms. For the live plant material, we washed it with deionized water, dried it in a drying oven at 60°C for 3 days, and then weighed it. To measure the N-content of Spartina, we subsampled plant snips (5–10 Spartina culms per plot), ground them in a Mixer Mill, and sent our samples to the Cornell Stable Isotope Laboratory for percent elemental analysis using an elemental analyzer-stable isotope ratio mass spectrometer system Thermo Delta V Advantage IRMS and Carlo Erba NC2500 EA systems.

We used the nitrogen content of Spartina leaves to estimate the level of enrichment experienced by a marsh. For each sample location, we multiplied live leaf biomass per square meter by percent nitrogen in those leaves to get nitrogen density, the number of grams of nitrogen in live Spartina leaves in a square meter of marsh. Nitrogen density reflects average nutrient input to the marsh over time and is independent of culm length or density. Thus, we were able to measure nitrogen density as a continuous variable in order to examine the relationship between nitrogen inputs and arthropod responses.

We sampled belowground biomass using a soil corer 8 cm in diameter and 16 cm long, but not all soil cores come out of the ground with that much material so we measured each core and controlled for volume in all root biomass measurements; we took one soil core sample per plot. We separated Spartina roots from soil using a sledge hammer and a high-power hose to loosen the dense, rhizomatous root mass enough to extract the soil. We then dried the roots in an oven set at 60°C for 72 h and then weighed them.

Arthropod Samples

We collected arthropods using a D-vac suction sampler with a 21 cm aperture, which was placed in 5 different locations within the plot for 3 s periods (following methods described in Murphy et al., 2012; Wimp et al., 2013). We collected arthropods during low tides so that we could place the D-vac head on the ground to effectively capture the epigeic assemblage. Previous studies have demonstrated that the D-vac suction sampler can effectively sample ground-dwelling arthropods in S. alterniflora, where it can remove 97% of the spiders in a collection area (Dobel et al., 1990). We immediately placed collected arthropods into closed containers with ethyl acetate, and transferred the samples into 75% ethanol. In the laboratory, we counted arthropods in each sample and converted these counts to number per square meter for each focal species.

Statistical Analyses

After calculating nitrogen density for each marsh survey site, we examined normality and equality of variance assumptions and our data met both assumptions. We used a One-Way ANOVA to test for differences in nitrogen density across the 14 marsh survey sites, followed by a Tukey's post-hoc test to examine significant differences among individual marsh sites. When we examined correlations among variables, live %N, root biomass, culm density, total herbivore density, total predator density, total epigeic prey density, and total spider density met normality and equality of variance assumptions. However, live biomass, thatch biomass, culm length, Tytthus density, and Grammonota density did not meet equality of variance and normality assumptions, and were square root transformed. Pardosa density required a log transformation to meet assumptions. Additionally, when we examined the relationship between nitrogen density and plant or arthropod assemblage variables, the uncertainty in our predictor variable (nitrogen density) was similar to the uncertainty in our response, so we could not use regression analysis, and we instead used correlation analysis.

Results

We found variation in nitrogen density across sites [F(13, 136) = 12.73, P < 0.0001; Figure 1], which allowed us to study how variation in nitrogen density affected salt marsh communities. Notably, we did not find a relationship between nitrogen density and latitude [F(1, 14.6) = 2.62, P = 0.15], and so our results are not simply due to latitudinal gradients. Nitrogen density was greatest in Jamaica Bay, which is a salt marsh located near the JFK airport runway for New York City, and was lowest at Awcomin Marsh (NH) and the Plum Island LTER site (MA).

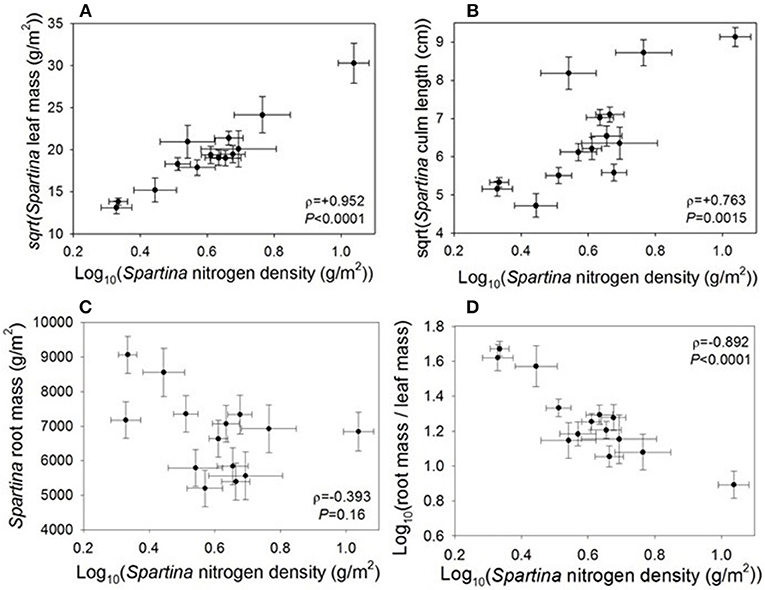

Live Spartina biomass is a component of nitrogen density, so we expected and found that the two variables were positively correlated (ρ = +0.952, P < 0.0001; Figure 2). This correlation remains significant even when the site with the highest nitrogen density (Site 9, Jamaica Bay, NY) is removed (ρ = +0.902, P < 0.0001). However, percent nitrogen of the plants was not correlated with nitrogen density (ρ = +0.238, P = 0.41; Supplement 2). We found a significant correlation between nitrogen density and Spartina culm length (ρ = +0.763, P = 0.0015; Figure 2), and this relationship remains significant when Site 9 is removed. Although culm length increased with nitrogen density, culm density decreased (ρ = −0.681, P = 0.0073), such that there were fewer culms per unit area. However, nitrogen density was not correlated with dead Spartina biomass (thatch) (ρ = +0.252, P = 0.39), or with Spartina root biomass (ρ = −0.393, P = 0.16); notably, when we remove the site with the highest nitrogen density (Site 9, Jamaica Bay, NY) the root biomass result becomes significant (ρ = −0.583, P = 0.037). Nitrogen density was also correlated with a significant decrease in root/leaf biomass (ρ = −0.892, P < 0.0001; Figure 2), and this correlation remains significant when we remove the site with the highest nitrogen density (ρ = −0.883, P < 0.0001).

Figure 2. Correlations between Spartina nitrogen density and Spartina (A) leaf biomass, (B) culm length, (C) root biomass when we remove the site with the highest nitrogen density the root biomass result becomes significant (ρ = −0.583, P = 0.037), and (D) root-to-shoot ratio.

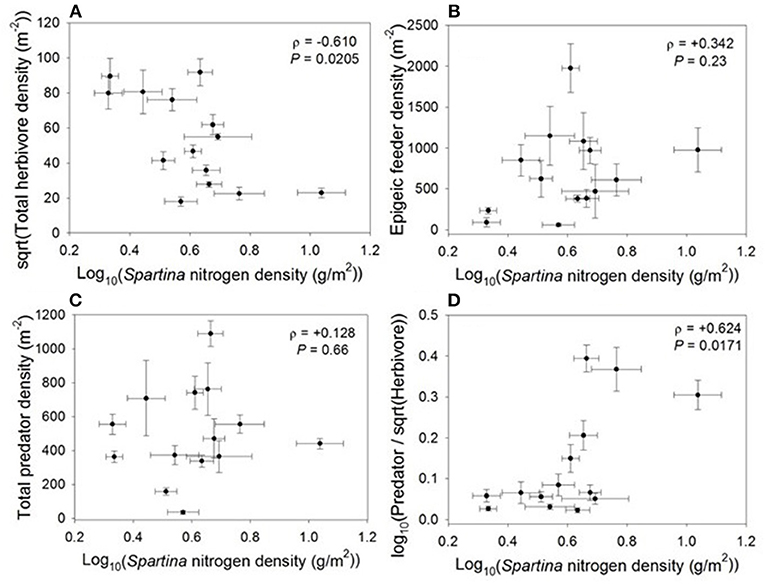

When we examined the impacts of Spartina nitrogen density on higher trophic levels, we found that nitrogen density had a negative relationship with total herbivore density (ρ = −0.610, P = 0.021; Figure 3, see Supplement 1 for a list of species found in most marshes). This response was likely driven by plant biomass; total herbivore density was negatively related to live biomass (ρ = −0.584, P = 0.0283), and was not correlated with live Spartina percent nitrogen (ρ = +0.001, P = 0.99), culm density (ρ = +0.255, P = 0.38), or culm length (ρ = −0.389, P = 0.17). However, nitrogen density had no relationship with the total density of epigeic feeders (ρ = +0.342, P = 0.23; Figure 3) or predator density (ρ = +0.128, P = 0.66; Figure 3). Notably, increasing nitrogen density led to an increase in the overall predator to herbivore ratio (ρ = +0.624, P = 0.017; Figure 3).

Figure 3. Correlations between Spartina nitrogen density and (A) total herbivore density, (B) total epigeic feeder density, (C) total predator density, and (D) predator-to-herbivore ratio.

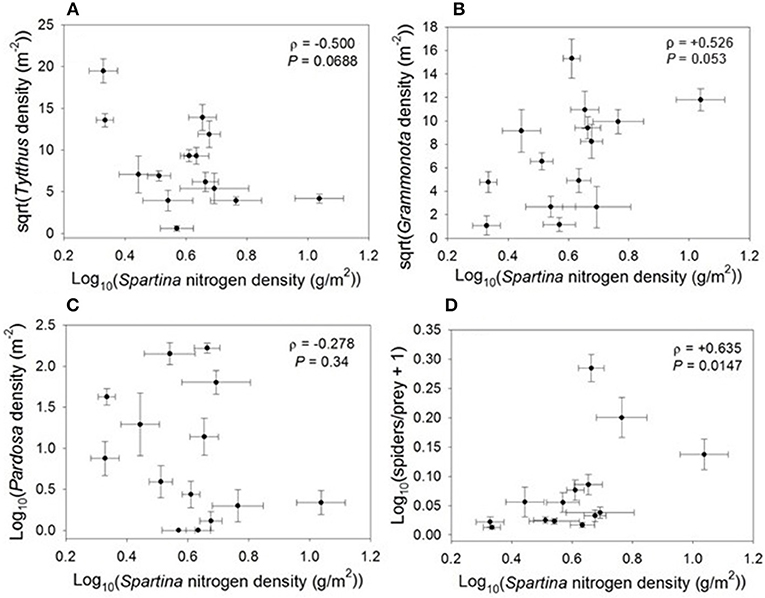

The relationship between nitrogen density and higher trophic levels varied according to predator group. Densities of the specialist predator Tytthus vagus declined marginally with increasing nitrogen density, similar to their planthopper prey (ρ = −0.500, P = 0.069; Figure 4), and were correlated with the densities of planthopper nymphs (ρ = +0.431, P = 0.0220). Densities of the web-building spider Grammonota trivittata (ρ = +0.526, P = 0.053) marginally increased and densities of the hunting spider Pardosa littoralis (ρ = −0.278, P = 0.34) had no relationship with nitrogen density. Indeed, the only Spartina variable that was correlated with densities of the hunting spider Pardosa littoralis was thatch biomass (ρ = +0.323, P = 0.03); Pardosa is an intraguild predator and cannibalistic, and thatch provides a refuge from intraguild predation/cannibalism (Langellotto and Denno, 2006). Additionally, the spider/prey ratio increased with an increase in Spartina nitrogen density (ρ = +0.635, P = 0.015; Figure 4). Thus, Spartina nitrogen density had a negative relationship with specialist predators such as Tytthus vagus, but a positive relationship with generalist spiders as a group.

Figure 4. Correlations between Spartina nitrogen density and (A) Tytthus density, (B) Grammonota density, (C) Pardosa density, and (D) spiders-to-prey ratio.

Discussion

Many ecological field studies focus on local scales and study plot-level responses to anthropogenic disturbances, such as nutrient enrichment. However, if results from these plot-level experiments do not scale up to reflect responses observed across larger geographic gradients, then their value to scientific advancement is questionable. Importantly, we found that results from this study, in which we sampled marshes from 8 states along the eastern seaboard, agree with our previous research conducted at a local scale (Wimp et al., 2010; Murphy et al., 2012), thus validating the value of plot-level experiments. Such scalability is particularly important when we are considering substantial drivers of global change, such as nutrient enrichment, which can impact terrestrial, freshwater, and marine ecosystems. We found that while nutrient subsidies generally have positive effects on aboveground plant biomass, they also decrease the root:shoot ratio. Additionally, we found that the impacts of nutrient subsidies on consumers differs according to trophic level. Some generalist predator responses and the predator: herbivore ratio had a positive relationship with nutrient subsidies, but herbivores and specialist predators had no relationship or a negative relationship with nutrient subsidies, similar to our previous results from studies at a local scale (Wimp et al., 2010; Murphy et al., 2012). Notably, because we have previously conducted experimental studies at multiple sites, and used methods in which we added nutrients as either a 1-year pulse or a multi-year press (Murphy et al., 2012), we can use our experimental treatments to explain patterns at a larger, geographical scale.

In numerous small-plot or entire-marsh manipulative experiments, researchers have found a positive correlation between nutrient enrichment and aboveground biomass (e.g., Valiela et al., 1978; Denno et al., 2002; Gratton and Denno, 2003; Pennings et al., 2005; Deegan et al., 2007, 2012; Wimp et al., 2010; Murphy et al., 2012). Our results from salt marshes sampled across a much larger geographic gradient show the same pattern as the results from these local studies. We found that marshes with greater nitrogen density produced Spartina plants with greater aboveground biomass, measured as both leaf mass and plant height. However, while aboveground biomass increased with nutrient enrichment, belowground biomass decreased with increasing nitrogen density such that marshes that experienced high nutrient enrichment had plants with a significantly lower root:shoot ratio compared to plants located in marshes with lower levels of nutrient enrichment. Previous work by Deegan et al. (2012) showed that the root:shoot ratio decreased with increasing nutrient enrichment in an ecosystem-wide manipulative experiment. Deegan et al. (2012) suggested that increasing nutrient availability enabled plants to reduce their root biomass while increasing above ground biomass. However, these top-heavy plants were more likely to topple into creeks because they lacked the root architecture to stabilize the creek banks; thus the decrease in the root:shoot ratio may lead to marsh loss and increased coastal erosion. Notably, our results from un-manipulated marshes across a wider geographic gradient support the findings of Deegan et al. (2012) as we found a significant negative correlation between root:shoot ratio and nutrient density across 14 marshes.

Herbivore declines in response to increasing nitrogen density across our sites may seem puzzling at first, but these results actually agree with manipulative experiments that we have conducted at a local scale. Previously, we have found that patterns of plant allocation to plant quantity (biomass) and quality (percent nitrogen) differ according to site (Murphy et al., 2012). In this study, we found an increase in Spartina aboveground biomass with an increase in nitrogen density, but we did not find any relationship between nitrogen density and percent nitrogen. Thus, the plants with the highest percent nitrogen content were not necessarily the plants with the greatest biomass. Our previous experimental results found that when plant allocation to biomass is greater than plant allocation to percent nitrogen, changes in herbivore abundance are minimal for a multi-year press, and negligible for a single-year pulse (Murphy et al., 2012). This pattern could arise for a number of reasons. First, if herbivores have to process greater amounts of plant material to obtain the nitrogen they need, this could negatively impact their growth and development. Second, bottom-up effects related to plant defense and palatability are known to affect herbivores (Vidal and Murphy, 2018). Spartina plants from northern marshes are more palatable to herbivores than plants from southern marshes, but plants in southern marshes receive more herbivore damage, which may be why they are more heavily defended (Pennings et al., 2001; Pennings and Silliman, 2005). We did not measure palatability as part of our study, and so are unable to determine whether herbivore densities correlate with plant defense and nutrient density. Third, an increase in live biomass would lead to a greater number of sites for web attachment for spiders, and hiding locations for predators that are intraguild predators and cannibals (Langellotto and Denno, 2006). Thus, increased structural complexity could lead to greater top-down pressure. In support of this last explanation, we have consistently found that higher trophic level predators are more strongly affected by nutrient addition relative to herbivores in manipulative experiments (Wimp et al., 2010; Murphy et al., 2012).

While the predator:herbivore ratio had a positive relationship with nitrogen density, such responses were not consistent across predator groups. Variable responses among predators to nitrogen density could be partly explained by diet breadth (e.g., generalists vs. specialists). Herbivores had a negative response to increasing plant nitrogen density; specialist predators tracked their herbivore prey and thus also responded negatively to nitrogen density. However, generalists were not negatively affected by nitrogen density and indeed some generalist predators responded positively to nitrogen density. Thus, the overall predator:herbivore ratio was also positively associated with nitrogen density. Additionally, differences in predator responses to nutrient addition also explain why we found an increase the predator:herbivore ratio, but not overall predator density, with an increase in nitrogen density. Indeed, predators exhibited every possible response to an increase in nitrogen density; taxa had either positive or negative relationships with nitrogen density, or demonstrated no significant response. Understanding the mechanism behind this response is simplified for specialist relative to generalist predators. For instance, the specialist predator Tytthus vagus feeds only on planthopper herbivore eggs, so densities of this predator declined with an increase in nitrogen density, similar to their prey. However, for the two most common generalist predators (the hunting spider, Pardosa littoralis and the web-building spider, Grammonota trivittata), responses are driven by both prey and structural resources (Wimp et al., 2019) and their ability to feed on prey from different food webs. Even though herbivore density declines with nitrogen density, Pardosa and Grammonota are multi-channel omnivores that can feed on a combination of prey from the live plant and epigeic food webs (Wimp et al., 2013; Murphy et al., in review). Since epigeic prey densities had no relationship with nitrogen density, these generalist predators could use alternative prey from the epigeic food web when herbivores were not available. This may explain why Pardosa densities were not affected by a change in nitrogen density. However, the marginally positive response of Grammonota to an increase in nitrogen density is more likely to be driven by structural resources. Grammonota is a web-building spider that requires adequate scaffolding for web attachment, and taller Spartina plants would provide such a resource. Because spiders were either positively affected by nitrogen density or exhibited no response, when compared to the negative response of herbivores, the overall spider:herbivore ratio was positive.

Our research helps us to understand how long-term nutrient enrichment of native ecosystems from anthropogenic sources affects the arthropod assemblage and foodweb dynamics. We found that while above-ground biomass increased with nutrient density, the ratio of belowground roots to aboveground shoots decreased significantly with nutrient enrichment, which may lead to marsh loss as suggested by Deegan et al. (2012). Further, we found that herbivore abundance was significantly lower in marshes that experienced high levels of nutrient enrichment. Recently there have been reports of an insect apocalypse (Hallmann et al., 2017; Lister and Garcia, 2018; Sanchez-Bayo and Wyckhuys, 2019; but see Thomas et al., 2019) and our results suggest that nutrient enrichment may be just one of many possible mechanisms, as also suggested by Sanchez-Bayo and Wyckhuys (2019). While the negative effects of nitrogen enrichment on aquatic systems are obvious due to the creation of dead zones, the impacts of nitrogen enrichment on terrestrial systems are more subtle, but nonetheless important. Not every trophic level, or functional group, responds to fertilization in a similar manner, and positive responses to fertilization are not common, even among herbivores where such responses might be anticipated or even expected. Such divergent responses to fertilization can lead to altered trophic structure and ultimately affect ecosystem processes.

Data Availability

The datasets for this study can be found in Dryad using doi: 10.5061/dryad.j4d7r61.

Author Contributions

DL performed the statistical analyses. GW and SM wrote the manuscript. All authors conceived the ideas, designed methodology, collected the data, contributed critically to subsequent drafts, and gave final approval for publication.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF-DEB 1026067 to GW; NSF-DEB 1026000 to SM).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Adams, C. Ademawagun, A. Ayotte, E. Barnes, K. Beins, M. Brabson, L. Buttrick, L. Cepero, N. Chaudhuri, G. Connor, K. Grenis, C. Hallagan, K. Hauri, M. Hayes, R. Huang, K. Hoffman, E. Kuras, M. Lynch, H. Maness, J. McCarty, M. Monahan, G. Ngo, E. Noyes, D. Olney, K. Parnigoni, E. Phillips, E. Powell, L. Preudhomme, B. Rojewski, A. Styer, M. Uelk, J. Wade, S. Wu, and M. Zeigler for help in the field or processing the samples in the lab. We thank the following site managers for facilitating our research and permits at each site: Ken Able at the Rutgers University Marine Station; Katie Brown, Kara Wooldrik, and Jaime Parker at Fore River Sanctuary; Jim Raynes at Conservation Commission of the Town of Rye for Awcomin Marsh; A.J. Dupere at the Urban Forestry Center; Scott Ruhren at Foxhill Salt Marsh; George Frame with the National Parks Service Gateway National Recreation Area for permits at the Jamaica Bay Unit and the Sandy Hook Unit; Anne Giblin at Plum Island LTER; Cheryl Wiitala at Fogland Nature Preserve; Melissa Slaughter at Colt State Park; Katherine Thomas and Leonard Krauss at Caumsett State Historic Park; Gary Kreamer and Ken Reynolds at Little Creek Wildlife area; Amanda Deschenes and Chris Bennett at Delaware Seashore State Park; and Alex Wilke at Virginia Coast Reserve.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fevo.2019.00350/full#supplementary-material

References

Bertness, M. D. (1991). Zonation of Spartina patens and Spartina alterniflora in a New England salt marsh. Ecology 72, 138–148. doi: 10.2307/1938909

Bertness, M. D., Crain, C., Holdredge, C., and Sala, N. (2008). Eutrophication and consumer control of New England salt marsh primary productivity. Conservat. Biol. 22, 131–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2007.00801.x

Bertness, M. D., Ewanchuk, P. J., and Silliman, B. R. (2002). Anthropogenic modification of New England salt marsh landscapes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 1395–1398. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022447299

Bertness, M. D., Silliman, B. R., and Jefferies, R. (2004). Salt marshes under siege. Am. Sci. 92, 54–61. doi: 10.1511/2004.1.54

Boyer, E. W., Goodale, C. L., Jaworski, N. A., and Howarth, R. W. (2002). Anthropogenic nitrogen sources and relationships to riverine nitrogen export in the northeastern U.S.A. Biogeochemistry 57/58, 137–169. doi: 10.1023/A:1015709302073

Deegan, L. A., Bowen, J. L., Drake, D., Fleeger, J. W., Friedrichs, C. T., Galvan, K. A., et al. (2007). Susceptibility of salt marshes to nutrient enrichment and predator removal. Ecol. Appl. 17, S42–S63. doi: 10.1890/06-0452.1

Deegan, L. A., Johnson, D. S., Warren, R. S., Peterson, B. J., Fleeger, J. W., Fagherazzi, S., et al. (2012). Coastal eutrophication as a driver of salt marsh loss. Nature 490, 388–392. doi: 10.1038/nature11533

Denno, R. F. (1976). Ecological significance of wing-polymorphism in Fulgoroidea which inhabit tidal salt marshes. Ecol. Entomol. 1, 257–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2311.1976.tb01230.x

Denno, R. F. (1977). Comparison of the assemblages of sap-feeding insects (Homoptera-Hemiptera) inhabiting two structurally different salt marsh grasses in the genus Spartina. Environ. Entomol. 6, 359–372. doi: 10.1093/ee/6.3.359

Denno, R. F. (1980). Ecotope differentiation in a guild of sap-feeding insects on the salt marsh grass, Spartina patens. Ecology 61, 702–714. doi: 10.2307/1937435

Denno, R. F., Gratton, C., Dobel, H., and Finke, D. L. (2003). Predation risk affects relative strength of top-down and bottom-up impacts on insect herbivores. Ecology 84, 1032–1044. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2003)084[1032:PRARSO]2.0.CO;2

Denno, R. F., Gratton, C., Peterson, M. A., Langellotto, G. A., Finke, D. L., and Huberty, A. (2002). Bottom-up forces mediate natural-enemy impact in a phytophagous insect community. Ecology 83, 1443–1458. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2002)083[1443:BUFMNE]2.0.CO;2

Denno, R. F., Lewis, D., and Gratton, C. (2005). Spatial variation in the relative strength of top-down and bottom-up forces: causes and consequences for phytophagous insect populations. Ann. Zool. Fennici 42, 295–311.

Denno, R. F., Mitter, M. S., Langellotto, G. A., Gratton, C., and Finke, D. L. (2004). Interactions between a hunting spider and a web-builder: consequences of intraguild predation and cannibalism for prey suppression. Ecol. Entomol. 29, 566–577. doi: 10.1111/j.0307-6946.2004.00628.x

Denno, R. F., Peterson, M. A., Gratton, C., Cheng, J., Langellotto, G. A., Huberty, A., et al. (2000). Feeding-induced changes in plant quality mediate interspecific competition between sap-feeding herbivores. Ecology 81, 1814–1827. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2000)081[1814:FICIPQ]2.0.CO;2

Döbel, H. G., and Denno, R. F. (1994). “Predator planthopper interactions,” in Planthoppers: Their Ecology and Management, eds R. F. Denno and T. J. Perfect (New York, NY: Chapman and Hall, 325–399.

Dobel, H. G., Denno, R. F., and Coddington, J. A. (1990). Spider (Aranae) community structure in an intertidal salt marsh: effects of vegetation structure and tidal flooding. Environ. Entomol. 19, 1356–1370. doi: 10.1093/ee/19.5.1356

Ferrenberg, S. M., and Denno, R. F. (2003). Competition as a factor underlying the abundance of an uncommon phytophagous insect, the salt marsh planthopper Delphacodes penedetecta. Ecol. Entomol. 28, 58–66. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2311.2003.00479.x

Finke, D. L., and Denno, R. F. (2002). Intraguild predation diminished in complex-structured vegetation: implications for prey suppression. Ecology 83, 643–652. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2002)083[0643:IPDICS]2.0.CO;2

Finke, D. L., and Denno, R. F. (2003). Intraguild predation relaxes natural enemy impacts on herbivore populations. Ecol. Entomol. 28, 67–73. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2311.2003.00475.x

Finke, D. L., and Denno, R. F. (2004). Predator diversity dampens trophic cascades. Nature 429, 407–410. doi: 10.1038/nature02554

Finke, D. L., and Denno, R. F. (2005). Predator diversity and the functioning of ecosystems: the role of intraguild predation in dampening trophic cascades. Ecol. Lett. 8, 1299–1306. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2005.00832.x

Finke, D. L., and Denno, R. F. (2006). Spatial refuge from intraguild predation: implications for prey suppression and trophic cascades. Oecologia 149, 265–275. doi: 10.1007/s00442-006-0443-y

Gratton, C., and Denno, R. F. (2003). Inter-year carryover effects of a nutrient pulse on Spartina plants, herbivores, and natural enemies. Ecology 84, 2692–2707. doi: 10.1890/02-0666

Haddad, N. M., Haarstad, J., and Tilman, D. (2000). The effects of long-term nitrogen loading on grassland insect communities. Oecologia 124, 73–84. doi: 10.1007/s004420050026

Halaj, J., and Wise, D. H. (2002). Impact of a detrital subsidy on trophic cascades in a terrestrial grazing food web. Ecology 83, 3141–3151. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2002)083[3141:IOADSO]2.0.CO;2

Hallmann, C. A., Sorg, M., Jongejans, E., Siepel, H., Hofland, N., Schwan, H., et al. (2017). More than 75 percent decline over 27 years in total flying insect biomass in protected areas. PLoS ONE 12:e0185809. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185809

He, Q., and Silliman, B. R. (2015). Biogeographic consequences of nutrient enrichment for plant–herbivore interactions in coastal wetlands. Ecol. Lett. 18, 462–471. doi: 10.1111/ele.12429

He, Q., and Silliman, B. R. (2016). Consumer control as a common driver of coastal vegetation worldwide. Ecol. Monogr. 86, 278–294 doi: 10.1002/ecm.1221

Holmgren, M., Scheffer, M., Ezcurra, E., Guitierrez, J. R., and Mohren, G. M. J. (2001). El Nino effects on the dynamics of terrestrial ecosystems. Trends Ecol. Evol. 16, 89–94. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(00)02052-8

Howarth, R. W., Billen, G., Swaney, D., Townsend, A., Jaworski, N., Lajtha, K., et al. (1996). Regional nitrogen budgets and riverine N & P fluxes for the drainages to the North Atlantic Ocean: natural and human influences. Biogeochemistry 35, 75–139. doi: 10.1007/BF02179825

Huberty, A., and Denno, R. F. (2006a). Consequences of nitrogen and phosphorus limitation for the performance of two planthoppers with divergent life-history strategies. Oecologia 149, 444–455. doi: 10.1007/s00442-006-0462-8

Huberty, A., and Denno, R. F. (2006b). Trade-off in investment between dispersal and ingestion capability in phytophagous insects and its ecological implications. Oecologia 148, 226–234. doi: 10.1007/s00442-006-0371-x

Huxel, G. R., and McCann, K. (1998). Food web stability: the influence of trophic flows across habitats. Am. Nat. 152, 460–469. doi: 10.1086/286182

Inouye, R., and Tilman, D. (1995). Convergence and divergence of old-field vegetation after 11 years of nitrogen addition. Ecology 76, 1872–1887. doi: 10.2307/1940720

Kirchner, T. B. (1977). The effects of resource enrichment on the diversity of plants and arthropods in a shortgrass prairie. Ecology 58, 1334–1344. doi: 10.2307/1935085

Langellotto, G. A., and Denno, R. F. (2006). Refuge from cannibalism in complex-structured habitats: implications for the accumulation of invertebrate predators. Ecol. Entomol. 31, 575–581. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2311.2006.00816.x

Lewis, D., and Denno, R. F. (2009). A seasonal shift in habitat suitability enhances an annual predator subsidy. J. Anim. Ecol. 78, 752–760. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2009.01550.x

Lister, B. C., and Garcia, A. (2018). Climate-driven declines in arthropod abundance restructure a rainforest food web. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, E10397–E10406. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1722477115

Matsumura, M., Trafelet-Smith, G. M., Gratton, C., Finke, D. L., Fagan, W. F., and Denno, R. F. (2004). Does intraguild predation enhance predator performance? A stoichiometric perspective. Ecology 89, 2601–2615. doi: 10.1890/03-0629

Mayer, B., Boyer, E. W., Goodale, C. L., Jaworski, N. A., van Breemen, N., Howarth, R. W., et al. (2002). Sources of nitrate in rivers draining sixteen watersheds in the northeastern U.S.: isotopic constraints. Biogeochemistry 57/58, 171–197. doi: 10.1007/978-94-017-3405-9_5

Mendelssohn, I. A. (1979a). The influence of nitrogen level, form, and application method on the growth response of Spartina alterniflora in North Carolina. Estuaries 2, 106–112. doi: 10.2307/1351634

Mendelssohn, I. A. (1979b). Nitrogen metabolism in the height forms of Spartina alterniflora in North Carolina. Ecology 60, 574–584. doi: 10.2307/1936078

Murphy, S. M., Wimp, G. M., Lewis, D., and Denno, R. F. (2012). Nutrient presses and pulses differentially impact plants, herbivores, detritivores and their natural enemies. PLoS ONE 7:e43929. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043929

Pennings, S. C., Clark, C. M., Cleland, E. E., Collins, S. L., Gough, L., Gross, K. L., et al. (2005). Do individual plant species show predictable resopnses to nitrogen addition across multiple experiments? Oikos 110, 547–555. doi: 10.1111/j.0030-1299.2005.13792.x

Pennings, S. C., and Silliman, B. R. (2005). Linking biogeography and community ecology: latitudinal variation in plant-herbivore interaction strength. Ecology 86, 2310–2319. doi: 10.1890/04-1022

Pennings, S. C., Siska, E. L., and Bertness, M. D. (2001). Latitudinal differences in plant palatability in Atlantic coast salt marshes. Ecology 82, 1344–1359. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2001)082[1344:LDIPPI]2.0.CO;2

Polis, G. A., Anderson, W. B., and Holt, R. D. (1997a). Toward an integration of landscape and food web ecology: the dynamics of spatially subsidized food webs. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 28, 289–316. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.28.1.289

Polis, G. A., and Hurd, S. D. (1996). Linking marine and terrestrial food webs: allochthonous input from the ocean supports high secondary productivity on small islands and coastal land communities. Am. Nat. 147, 396–423. doi: 10.1086/285858

Polis, G. A., Hurd, S. D., Jackson, C. T., and Sanchez-Pinero, F. (1997b). El Nino effects on the dynamics and control of an island ecosystem in the Gulf of California. Ecology 78, 1884–1897. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(1997)078[1884:ENOEOT]2.0.CO;2

Polis, G. A., Hurd, S. D., Jackson, C. T., and Sanchez-Pinero, F. (1998). Multifactor population limitation: variable spatial and temporal control of spiders on Gulf of California islands. Ecology 79, 490–502. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(1998)079[0490:MPLVSA]2.0.CO;2

Redfield, A. C. (1972). Development of a New England salt marsh. Ecol. Monogr. 42, 201–237. doi: 10.2307/1942263

Robinson, D. (1994). The responses of plants and their roots to non-uniform supplies of nutrients. New Phytol. 127, 635–647. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1994.tb02969.x

Sanchez-Bayo, F., and Wyckhuys, K. A. G. (2019). Worldwide decline of the entomofauna: a review of its drivers. Biol. Conserv. 232, 8–27. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2019.01.020

Settle, W. H., Ariawan, H., Astuti, E. T., Cahyana, W., Hakim, A. L., Hindayana, D., et al. (1996). Managing tropical rice pests through conservation of generalist natural enemies and alternative prey. Ecology 77, 1975–1988. doi: 10.2307/2265694

Siemann, E. (1998). Experimental tests of effects of plant productivity and diversity on grassland arthropod diversity. Ecology 79, 2057–2070. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(1998)079[2057:ETOEOP]2.0.CO;2

Stiling, P., and Strong, D. R. (1983). Weak competition among Spartina stem borers, by means of murder. Ecology 64, 770–778. doi: 10.2307/1937200

Thomas, C. D., Jones, T. H., and Hartley, S. E. (2019). “Insectageddon”: a call for more robust data and rigorous analyses. Glob. Chang. Biol. 25, 1891–1892. doi: 10.1111/gcb.14608

Tilman, D. (1999). Global environmental impacts of agricultural expansion: the need for sustainable and efficient practices. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.U.S.A. 96, 5995–6000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.5995

Valiela, I., and Bowen, J. L. (2002). Nitrogen sources to watersheds and estuaries: role of land cover mosaics and losses within watersheds. Environ. Pollut. 118, 239–248. doi: 10.1016/S0269-7491(01)00316-5

Valiela, I., and Cole, M. L. (2002). Comparative evidence that salt marshes and mangroves may protect seagrass meadows from land-derived nitrogen loads. Ecosystems 5, 92–102. doi: 10.1007/s10021-001-0058-4

Valiela, I., and Teal, J. M. (1979). The nitrogen budget of a salt marsh ecosystem. Nature 280, 652–656. doi: 10.1038/280652a0

Valiela, I., Teal, J. M., and Deuser, W. G. (1978). The nature of growth forms in the salt marsh grass Spartina alterniflora. Am. Nat. 112, 461–470. doi: 10.1086/283290

Vidal, M. C., and Murphy, S. M. (2018). Bottom-up vs. top-down effects on terrestrial insect herbivores: a meta-analysis. Ecol. Lett. 21, 138–150. doi: 10.1111/ele.12874

Vince, S. W., Valiela, I., and Teal, J. M. (1981). An experimental study of the structure of herbivorous insect communities in a salt marsh. Ecology 62, 1662–1678. doi: 10.2307/1941520

Vitousek, P. M., Mooney, H. A., Lubchenco, J., and Melillo, J. M. (1997). Human domination of Earth's ecosystems. Science 277, 494–499. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5325.494

Warren, R. S., and Niering, W. A. (1991). Vegetation change on a northeast tidal marsh: interaction of sea-level rise and marsh accretion. Ecology 74, 96–103. doi: 10.2307/1939504

Wigand, C., Watson, E. B., Martin, R., Johnson, D. S., Warren, R. S., Hanson, A., et al. (2018). Discontinuities in soil strength contribute to destabilization of nutrient-enriched creeks. Ecosphere 9:e02329. doi: 10.1002/ecs2.2329

Wimp, G. M., Murphy, S. M., Finke, D. L., Huberty, A. F., and Denno, R. F. (2010). Increased primary production shifts the structure and composition of a terrestrial arthropod community. Ecology 91, 3303–3311. doi: 10.1890/09-1291.1

Wimp, G. M., Murphy, S. M., Lewis, D., Douglas, M. R., Ambikapathi, R., Van-Tull, L., et al. (2013). Predator hunting mode influences patterns of prey use from grazing and epigeic food webs. Oecologia 171, 505–515. doi: 10.1007/s00442-012-2435-4

Keywords: eutrophication, food web structure, latitudinal gradient, nitrogen, nutrient subsidies, salt marsh

Citation: Wimp GM, Lewis D and Murphy SM (2019) Impacts of Nutrient Subsidies on Salt Marsh Arthropod Food Webs: A Latitudinal Survey. Front. Ecol. Evol. 7:350. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2019.00350

Received: 26 April 2019; Accepted: 02 September 2019;

Published: 26 September 2019.

Edited by:

Qinfeng Guo, United States Forest Service (USDA), United StatesReviewed by:

Florencia Botto, Institute of Marine and Coastal Research (IIMyC), ArgentinaQiang He, Duke University, United States

Copyright © 2019 Wimp, Lewis and Murphy. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gina M. Wimp, Z213MjJAZ2VvcmdldG93bi5lZHU=

Gina M. Wimp

Gina M. Wimp Danny Lewis1

Danny Lewis1 Shannon M. Murphy

Shannon M. Murphy