95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Environ. Sci. , 02 February 2024

Sec. Interdisciplinary Climate Studies

Volume 12 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2024.1278235

This article is part of the Research Topic Nature-based Solutions for Urban Resilience and Human Health View all 10 articles

Shannon Mihaere1

Shannon Mihaere1 Māia-te-oho Holman-Wharehoka2

Māia-te-oho Holman-Wharehoka2 Jovaan Mataroa3

Jovaan Mataroa3 Gabriel Luke Kiddle4

Gabriel Luke Kiddle4 Maibritt Pedersen Zari5*

Maibritt Pedersen Zari5* Paul Blaschke4

Paul Blaschke4 Sibyl Bloomfield5

Sibyl Bloomfield5Nature-based solutions (NbS) offer significant potential for climate change adaptation and resilience. NbS strengthen biodiversity and ecosystems, and premise approaches that centre human wellbeing. But understandings and models of wellbeing differ and continue to evolve. This paper reviews wellbeing models and thinking from Aotearoa New Zealand, with focus on Te Ao Māori (the Māori world and worldview) as well as other Indigenous models of wellbeing from wider Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa Oceania. We highlight how holistic understandings of human-ecology-climate connections are fundamental for the wellbeing of Indigenous peoples of Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa Oceania and that they should underpin NbS approaches in the region. We profile case study experience from Aotearoa New Zealand and the Cook Islands emerging out of the Nature-based Urban design for Wellbeing and Adaptation in Oceania (NUWAO) research project, that aims to develop nature-based urban design solutions, rooted in Indigenous knowledges that support climate change adaptation and wellbeing. We show that there is great potential for nature-based urban adaptation agendas to be more effective if linked closely to Indigenous ecological knowledge and understandings of wellbeing.

Climate change is the most significant health issue of our times (Costello et al., 2009; Smith et al., 2014; World Health Organisation, 2021). Climate change results in direct impacts on human health, including deaths, illness and injury due to extreme weather events. In addition, significant indirect impacts are mediated by a complex and powerful interplay of social, ecological, and economic factors. These indirect impacts of climate change on human health include: shifting patterns of infectious disease; air pollution; freshwater contamination; impacts on the built environment from sea level rise and storm events; forced migration; conflict over scarce resources; increasing food insecurity; and (possible) economic collapse (McIver et al., 2016; Tukuitonga and Vivili, 2021; Romanello et al., 2022). Emerging research also highlights the deleterious effects of climate change on mental health (Gibson et al., 2020; Tiatia et al., 2022).

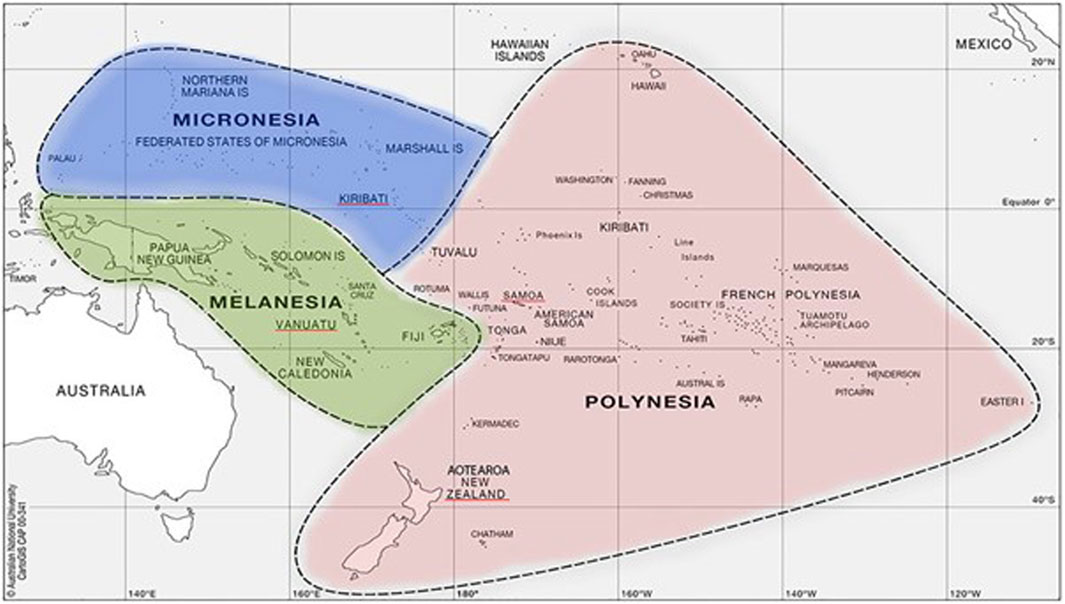

The health impacts of climate change, and in particular the harm caused by the increased frequency and intensity of storm events linked to climate change, have heightened the need to provide urgent solutions that protect communities and enhance resilience (Romanello et al., 2022). In Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa Oceania, including Aotearoa New Zealand (Figure 1), recent events (such as damaging floods and cyclones affecting Aotearoa New Zealand in January and February 2023, and Vanuatu in February and March 2023) have highlighted the urgent need to adapt to climate change (Ministry for the Environment, 2022). Using nature-based solutions (NbS) is one way of doing this.

FIGURE 1. Regions of Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa Oceania. Source: Adapted from Australian National University (CC License).

NbS are actions to protect, conserve, restore, and manage natural or modified terrestrial, freshwater, coastal and marine ecosystems, which address social, economic and environmental challenges effectively and adaptively, while simultaneously providing human wellbeing, ecosystem services and resilience and biodiversity benefits (Cohen-Shacham et al., 2016). This definition emphasises that the overall aim of NbS approaches is to generate multiple societal, cultural, health and economic co-benefits for people while conserving, regenerating, or restoring ecological and biodiversity health (IUCN, 2023). Understanding that the health of ecosystems, and the biodiversity within them, is essential for human survival, while leveraging the patterns and functions of social-ecological systems and ecosystem services across and within interconnected landscapes, ocean ecologies and socio-cultural contexts, is crucial to the successful design and implementation of NbS (Cohen-Shacham et al., 2016). Working with nature, rather than against it or without it, often leads to more effective, economical and culturally appropriate responses to societal challenges while at the same time conserving or restoring biodiversity (Pedersen Zari et al., 2022).

Central to this paper is the principle that for the Indigenous communities of Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa Oceania impacted by climate change, localised understandings of wellbeing, or “placing wellbeing” (Panelli and Tipa, 2007; Tiatia-Seath et al., 2020) must inform a full assessment of impact and potential responses, including NbS. In short, nuanced and contextualised understandings of wellbeing must be central to Indigenous-led and focused adaptation efforts (Kiddle et al., 2021). It is also vital to understand that relationships between people, the land, ocean, mountains, rivers, forest, animals and so on are different in Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa Oceania than in other parts of the world. For example, in Te Ao Māori (Māori world and worldview), genealogy at its most profound, includes a more-than-human lineage and kinship. Māori are literally related to certain mountains, rivers, and bodies of water which are seen as living entities in their own right (expanded upon in Section 3) (Yates, et al., 2023). This means to intervene in, regenerate, manipulate, or work with “nature” has very real spiritual connotations and potentially social justice outcomes related to wellbeing, particularly for Indigenous peoples. Understanding this, at least in the context of Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa Oceania, will ensure that NbS are contextualised and support fundamental values, and thus will be more likely to be successful in terms of ecological and climate outcomes, but also holistic human wellbeing. Internationally agreed definitions and practices of NbS are useful, but these must be locally contextualised in different parts of the world to fit with differing worldviews, particularly related to human-nature relationships. Without such contextualisation, NbS run the risk of undermining local or Indigenous notions of human and ecological wellbeing, worldviews, and social justice agendas. Climate adaptation and NbS should not become a tool of neo-colonisation of spaces or ideas, even if unintentional.

This article reviews Indigenous wellbeing models from Aotearoa New Zealand and wider Oceania; and in doing so brings attention to the important role of NbS and NbS approaches that centre human wellbeing, and the need for a more nuanced Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa Oceania approach to NbS. The article presents the summarised findings of a literature review and critically links Indigenous wellbeing models, climate impacts, and social justice factors within the context of Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa Oceania. It then presents key findings from two Indigenous knowledge-driven explorations of climate change adaptation through urban built environment design, one in Aotearoa New Zealand, and one in the Cook Islands, that have emerged out of Nature-based Urban design for Wellbeing and Adaptation in Oceania (NUWAO) research; a project funded by the New Zealand government through the Royal Society of New Zealand, that aims to develop nature-based urban design solutions, driven by Indigenous knowledges that support climate change adaptation and individual and community wellbeing in diverse urban settings in Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa Oceania. NUWAO focuses on urban NbS because there has been less attention on urban NbS in the region (Kiddle et al., 2021), and because globally most people live in cities now meaning urban areas are where climate change impacts are more likely to be experienced (Pedersen Zari et al., 2022). In Aotearoa New Zealand approximately 87% of the general population and 85% of Māori live in urban centers, the result of a rapid urbanisation process in the 20th century (Ryks et al., 2019). In nearly every Pacific island nation urban population growth rates now exceed national population growth rates (Kiddle et al., 2021), and some of the world’s highest urbanisation rates exist, particularly in the western nations of Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa Oceania (often termed “Melanesia”), while to the north urbanisation rates are approaching 70% (in areas referred to as “Micronesia”) (Kiddle et al., 2021).

An important part of decolonising research practices is to make the positionality of researchers apparent (Tuhiwai Smith, 2012; Latai-Niusulu et al., 2020). In light of this, authors of this article include Indigenous Māori (Indigenous peoples of Aotearoa New Zealand) and Cook Island researchers and designers, as well as those who are Pākehā (New Zealanders of European descent), all of whom are involved in research related to NUWAO. Further details about the positionality of each author and the NUWAO project are available at www.nuwao.org.nz.

Climate change poses a significant threat to the health and wellbeing of Indigenous people globally (United Nations, 2016), including Māori in Aotearoa New Zealand and Pacific communities across Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa Oceania. The health impacts of climate change are progressively becoming realised (Royal Society Te Aparangi, 2017) and will be felt disproportionately across vulnerable groups and those already enduring poorer health outcomes (Jones et al., 2014), including Māori and Pacific communities. In the Pacific islands of Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa Oceania, Indigenous people are at the frontline of climate change impacts. The nations of the Pacific have unique and diverse island and marine ecosystems and cultures that are facing significant impacts from changes to climate (Nurse et al., 2014; Alam et al., 2022). These changes directly threaten the health of Pacific islanders, as well as economic and social development. Across Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa Oceania increasing extreme weather events, especially cyclones, floods and droughts, are also displacing populations, causing injury and psychological trauma (Gibson et al., 2020; Tiatia et al., 2022). Indirectly, human health is threatened because of negative climate change impacts on the health of ecosystems that fundamentally underpin human wellbeing, the health of which is considered by many Indigenous peoples in Oceania to be indivisible from human wellbeing.

Communities of Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa Oceania live in diverse contexts but face a number of common challenges. These include: a tendency to live in geographical locations that are particularly prone to the impacts of climate change (UNESCAP, 2019); high dependence on land and ocean ecologies for basic needs and economic security (for example, food, shelter, medicines, and fuel); and experience of economic deprivation as well as social and political marginalisation (Bailey-Winiata, 2021), that has often, but not in all nations of the Pacific, been exacerbated by complex histories and on-going realities of colonisation. Climate change will likely increase existing social and health inequalities, both between and within nations (Woodward and Porter, 2016; Levy et al., 2017), with traditionally marginalised Indigenous populations likely to be impacted disproportionally. This is concerning because the response to climate change thus far has generally adhered to western hegemonic understandings of health and ecological systems (Jones et al., 2014). We contend that Indigenous-focused and led approaches are needed, including those centring wellbeing and working with nature to effectively adapt to climate change (Kiddle et al., 2021).

Definitions and models of wellbeing are fluid and evolving. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the United Nations highlight the importance of individual and communal wellbeing in people’s development (Yates et al., 2022). Yet, wellbeing as articulated and measured in typical western metrics tends to be individualistic. In contrast, a common thread running through the world’s diverse Indigenous populations is the collective nature of wellbeing (Durie, 1994). Indigenous concepts of wellbeing tend to be broader and more holistic and, particularly, recognise the interconnected relationships of people with ecosystems and biodiversity, especially related to ancestral lands, oceans and waterways, which Indigenous peoples often depend upon for their collective flourishing (Durie, 1985; United Nations, 2011). Recognition of the interconnected relationships of people with the living world is also consistent with an ecosystem services framework, which is often used to address health and wellbeing outcomes internationally including in the Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa Oceania region (McFarlane et al., 2019).

In the context of NbS, a defining feature of indigeneity is the intrinsic relationship between humankind and the natural environment, with Indigenous cultures paying deliberate attention to the responsibilities these relationships generate and giving active expression to them in all aspects of life. In short, Indigenous ontologies position humans as inseparable from the Earth and its living ecologies (Redvers et al., 2020). For example, in Aotearoa New Zealand, in Te Ao Māori (Māori world/worldview), humans have Whakapapa (genealogical/kinship) relationships with many aspects of the natural world, including Papatūānuku (the earth mother), as well as specific mountains, rivers, waterways and even plants. People are literally related to the land. Whakataukī (proverbs) illustrate the holistic kinship relationship Māori have with the environment. For example, a common Whakataukī is: Ka ora te wai, Ka ora te whenua. Ka ora te whenua, Ka ora te tangata (If the water is healthy, the land will be nourished. If the land is nourished, the people will be provided for). Another is: Ko au te whenua, te whenua ko au, Ko au te awa, te awa ko au (I am the land, the land is me. I am the river, the river is me). In Kiribati, people refer to the sea as their mother ocean (Anterea, cited in Xuande and Yuting, 2021). In Samoa, the word for earth, Ele’ele, also translates to blood, highlighting that the integral part of being or existing is the land (Powell and Fraser, 1892; Vaai, 2019). Holistic health, wellbeing, and identity is therefore inherently connected to the eco-sphere in the region. This relational ontology is fundamentally of Te Moana-nui-a-kiwa and is at the foundation of Oceanic understandings of the world. This highlights that working with nature in the region potentially holds very different meaning and significance than in other parts of the world.

In Aotearoa New Zealand Māori have a holistic and interconnected relationship with Te Taiao (the living world, nature) (Mead, 2003; Hikuroa, 2017). The traditional knowledge base, Mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge), has developed over many millennia (and continues to), including centuries in Aotearoa following Polynesian settlement likely in the thirteenth century (Anderson et al., 2015). Mātauranga Māori includes a multifaceted endeavour to apply knowledge and understanding of Te Taiao following a systemic methodology based on evidence, culture, values and worldview (McAllister et al., 2019).

An early and influential model of Māori wellbeing in Aotearoa New Zealand is Te Whare Tapa Whā, originating in a meeting of Māori health workers in 1982 and later refined and presented by leading Māori health advocate Professor Mason Durie in 1984 (Durie, 1985 & 1994). Te Whare Tapa Whā models Māori health as the four walls of a whare (house), with all four walls necessary to ensure symmetry and balance of the individual and community. The four walls, or dimensions of Māori wellbeing in the model, are: Taha Tinana (physical health); Taha Wairua (spiritual health); Taha Hinengaro (mental health); and Taha Whānau (family health). The model represents the concept that should any of these dimensions be missing or harmed in some way, a person, or a collective, may become unwell. Overall, the model looks to incorporate a traditional Māori approach which takes the view that the spiritual dimension (often missing in modern health approaches), family, and the balance of the mind are as important as the physical manifestations of illness (Durie, 1994). Many representations of Te Whare Tapa Whā also show the four walls of the whare resting on the Whenua (ground or land, also placenta), showing the foundation of the holistic model of health to be itself dependent on the health of the Whenua (Moewaka Barnes and McCreanor, 2019).

Taha Wairua is very important in Te Ao Māori and is a significant and integral part of Māori wellbeing. Taha Wairua provides a spiritual link that is interwoven through Whānau (family) and the environment to ensure health and wellbeing. Durie (1994) emphasises that the spiritual world for Māori extends to relationships with the environment. For example, Whenua (the land), Awa (rivers), and Maunga (mountains) have a spiritual importance, and their significance is often immortalised in Pūrākau (stories), Waiata (songs), Mōteatea (laments), Kōrero Tuku Iho (oral tradition) and Whaikōrero (formal oratory). Thus, Taha Wairua is deeply affected when Māori experience a lack of access to ancestral lands which is regarded by Kaumātua (tribal elders) as a sign of poor health (Thom and Grimes, 2022).

Te Whare Tapa Whā was followed in 1985 by Rangimārie Rose Pere’s model of Māori wellbeing, Te Wheke, based on the eight tentacles of an octopus. Te Wheke models all aspects of Māori life and health as interconnected, enabling an inclusion of family, spirituality and ancestors. This model extended past the four dimensions as established by Durie to eight dimensions of wellbeing—adding Mana Ake (the unique qualities of each individual and family to create positive identity), Mauri (the life-sustaining principle in all people, elements of the living world, and objects), Ha a koro ma a kuri ma (breath of life from ancestors), and Whatumanawa (the open and healthy expression of emotion) (Love, 2004). The collective Waiora, or the total wellbeing for the individual and family, is gained from a combination of these dimensions, and is represented in the model as the eyes of the octopus. In Te Wheke each tentacle of the octopus represents aspects of a person’s life that need to be supported in order to sustain balance and wholeness (ibid).

In 1988 the New Zealand Royal Commission on Social Policy1, in Ngā Pou Mana, presented a model of Māori wellbeing in which the foundations of social policy and social wellbeing were presented as four supports, or four interrelated prerequisites: Mana (prestige, authority, control, power, influence, status, and charisma); cultural integrity; a sound economic base; and a sense of confidence and continuity. Ngā Pou Mana also outlined four factors considered to be fundamental to social wellbeing for Māori, specifically: Whanaungatanga (the importance of the family), Taonga Tuku Iho (cultural heritage), Te Ao Tūroa/Te Taiao (the natural environment) and Tūrangawaewae (the land base; a place of belonging, standing and identity). The Ngā Pou Mana model’s point of difference to earlier work in Aotearoa New Zealand was an unequivocal emphasis on linkages between Māori and the environment. Reference to Te Ao Tūroa paid homage to the number of Waitangi Tribunal2 claims throughout the 1980 s responding to the modification and pollution of culturally significant waterways in Aotearoa New Zealand (Derby, 2023). The explicit attention to Te Ao Turoa seeks to emphasise that Māori wellbeing is affected not just by access to, or quantity of, natural resources, but also their state or condition. Therefore, experiences like the loss of land (through colonisation), pollution affecting traditional areas of food gathering, and the depletion of “natural resources,” are all destabilising factors on health and wellbeing and debase spiritual and cultural values (Royal Commission on Social Policy, 1988; Thom and Grimes, 2022). This makes sense when, as discussed earlier, Māori understand their kinship relationship with, and responsibility to, the natural world recognising rivers and mountains, for example, as living ancestors. The natural environment is not simply resource for exploitation. The connection between spirituality, ecological health, and physical health for Māori makes links to negative health and wellbeing outcomes associated with colonisation, the accelerated deforestation transformation of the Aotearoa New Zealand landscape, and rapid urbanisation of the 20th century clearer. Like many other Indigenous populations these social justice impacts combine to make land access, tenure, and management as an aspect of adaptation to climate change more complex (Ryks et al., 2019; Aslany and Brincat, 2021).

Historically the western world has looked to define the wellbeing of Pacific peoples from a eurocentric perspective. However, Pacific peoples have their own ways of describing what wellbeing means to them (Tanguay, 2014). For example, spirituality is central to Pacific ways of life and is prominent in traditional understandings and models of Pacific wellbeing (Pulotu-Endemann, 2001). Indeed, leading Pacific theologian Reverend Upolu Lumā Vaii describes a “Pacific eco-relational spirituality” as the essence to life and wellbeing, such that there is “no wellbeing of the individual without the wellbeing of the whole” (Vaii, 2019, p. 7).

An important model of Pacific wellbeing developed in the Aotearoa New Zealand context is the Fonofale model of wellbeing for Pacific peoples, originally developed by Fuimaono Karl Pulotu-Endemann in the early 2000 s (Pulotu-Endemann, 2001). Here the configuration of the Samoan fale (house with open sides and traditionally a thatched roof) represents various interconnected concepts that are central to the wellbeing of Pacific peoples: (i) the roof—“culture”—as the overarching component, under which all other elements important for Pacific peoples are maintained: (ii) “family” as the foundation; and (iii) the four posts of “physical,” “spiritual,” “mental” and “other” sustaining the link between family and culture. The Fonofale model, like Te Whare Tapa Whā, also shows the interconnectedness of all elements, as influenced by the environment, time, and context (Thomsen et al., 2018).

More recent work on Pacific wellbeing commissioned by the Aotearoa New Zealand Treasury (Thomsen et al., 2018) looked to inform ongoing refinements to the Living Standards Framework, first introduced in 2011 to the Aotearoa New Zealand public sector to model and measure multidimensional wellbeing and, overall, drive a wellbeing focus in public policy. This work was informed by the Fonofale model as described above and recommended that “any framework for describing and understanding Pacific peoples must highlight family as the dominant relationship that Pacific peoples acquire from birth, and highlight the key influence that culture plays in the social, human, and physical capital stocks of Pacific Aotearoa New Zealanders” (ibid, p. i). The work recommended four initial indicators for Pacific peoples’ wellbeing for inclusion in the Living Standards Framework: “family resilience;” “Pacific connectedness and belonging;” “religious centrality and embeddedness;” and “cultural recognition.”

Within the Pacific island nations and territories, Vanuatu has been a regional leader in both measuring wellbeing and embedding a wellbeing focus within public policy making. The “Alternative Indicators of Wellbeing for Melanesia” initiative, for example, begun in 2010, defined through extensive research three distinct domains of wellbeing particularly relevant for wellbeing and happiness in Vanuatu: access to customary land and natural resources; traditional knowledge and practice; and community vitality (Malvatumauri National Council of Chiefs, 2012). Vanuatu’s approach has been focused on subjective wellbeing, or happiness. Centred around the question “what do you need in order to have a good life?,” key results highlight that people living on customary land, participating in traditional ceremonial activities, and those who are active members of their community, are, on average, happier in Vanuatu. The deeper and more nuanced understandings of wellbeing created through this work in Vanuatu have flowed through into national development planning. For example, for the first time, policies around traditional medicine and healing practices, traditional knowledge, access to traditional wealth items, access to customary land, and use of Indigenous languages have been included in the 2016–2030 Vanuatu National Sustainable Development Plan (NSDP) (Department of Strategic Policy, Planning and Aid Coordination, 2017).

The environmental context is typically prominent in Pacific models of wellbeing. For example, in the Cook Islands, Pito’enua (health and wellbeing) encompasses five dimensions: Kopapa (physical wellbeing); Tu Manako (mental and emotional wellbeing); Vaerua (spiritual wellbeing); Kopu Tangata (social wellbeing); and Aorangi (total environment), with the latter meaning how an individual is shaped by society and the environment (Scheyvens et al., 2023a). In addition, the Tokelauan Te Vaka Atafaga model of wellbeing positions wellbeing as a Vaka (voyaging canoe) within the ocean, which acts as its environmental context. For example, if the sea is rough, or the wind is too strong, these things will affect the wellbeing of those on the Vaka (Kupa, 2009). Environmental wellbeing is also central to the “Frangipani Framework of Pacific Wellbeing,” which draws from recent work exploring the wellbeing of Pacific peoples from communities in Samoa, Fiji, Vanuatu, and Cook Islands. Here Pacific wellbeing is modelled into spiritual, mental, physical, financial and social domains (the petals of the frangipani flower) and environmental wellbeing (how the health of the environment and access to land and other environmental resources has an impact on human wellbeing) is modelled as the trunk and roots of the frangipani tree (Scheyvens et al., 2023b & 2023c).

In considering the importance of traditional spiritual beliefs on wellbeing in Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa Oceania, the impacts of western colonialism must be taken into account. As a phenomenon accompanying colonisation, the conversion of most Oceanic peoples to Christianity is of particular significance (Vaai, 2019). The overwhelming majority of adult inhabitants of most Pacific island countries consider themselves Christian, with the exception of the non-indigenous population of Fiji, who include Hindu and Muslim peoples totalling just over one-third of the population (Fiji Bureau of Statistics, 2023). Even in Aotearoa New Zealand, where adherence to any religious faith has declined significantly in the last 2 decades, approximately two-thirds of Māori declared themselves as Christian in the 2018 census, a significantly higher proportion than in the overall population (which is approximately 40%) (Statistics New Zealand, 2019).

Overall, wellbeing understandings, from the Pacific islands of Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa Oceania and from Pacific communities within Aotearoa New Zealand, highlight how wellbeing for Pacific peoples is communal, linked closely to the spiritual world, and is influenced by relationships with island and ocean environments, and the ecosystem services that these environments provide. At the same time, Pacific models of wellbeing are also place-based; highlighting how contextualised and nuanced understandings of wellbeing are required in a unique, and very diverse, oceanic region.

The links between connection to nature and human wellbeing are well documented and numerous and range from physiological benefits to psychological ones that are both overt and easily to comprehend through to ones which occur on a subconscious basis (Gillis and Gatersleben, 2015; Soderlund and Newman, 2015; Aerts et al., 2018). Evidence exists of positive physical benefits such as reduced blood pressure and cortisol levels, increased parasympathetic nervous system activity, and reduction in overall stress; increased immunity; and increased cognitive ability (Berman et al., 2008; Tyrväinen et al., 2014). Evidence of psychological benefits include: positively modified behaviour, particularly in terms of social interaction and reduced violence; decreased rates of depression; increased ability to concentrate; increased happiness; and increased social cohesion (Kuo and Sullivan, 2001; Mayer and Frantz, 2004; Hartig et al., 2014; Cohen-Cline et al., 2015).

NbS typically involve working with vegetation, water, and biodiversity, so can therefore have numerous positive impacts on human individual health (as well as more technical benefits related to climate change adaptation; for example, flood mitigation). This means that the design of urban nature-based interventions can more strategically consider the causes of health and wellbeing (rather than just the causes of disease). For example, the spatial design and materiality of buildings and their facades, as well as public works of art and soundscapes, and the experiences of these in linked urban spaces impacts on experiences of human-nature relationship in cities (Pedersen Zari, 2019). Specific cultural interpretations of nature and human-nature relationships, as well as the inclusion of specific native or cultural keystone plant species are also highly important, particularly in the context of Indigenous communities (Rodgers et al., 2023). This means that the quality and variety of opportunities for human-nature relationships in urban contexts and how spatial experiences are linked through time and cultural values is likely to be important in the creation of NbS that result in human wellbeing in general, and Indigenous wellbeing specifically. This is in contrast to simply understanding the success or value of NbS as, for example, a measurable quantity of trees or the size of urban green space. Effective urban NbS are arguably more complex and holistic than simply the amount of biomass or greenspace in a city.

Although literature shows that experiencing and valuing nature-human relationships differs between various cultural groups (Sangha et al., 2018), and certainly this is true in Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa Oceania, to date most examples of NbS do not consider in depth how cultural diversity and the differences between the preferences or needs of various groups of people can be more effectively explored and integrated into design practice. Exploration of this is an opportunity for design-led research focused on NbS in Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa Oceania (and in other parts of the world). Such NbS design could be an important contributor to a more holistic notion of ecological urban sustainability or regeneration that takes into account cultural relationships to land and ocean. This is of great importance for safeguarding both the physical and psychological wellbeing of individuals and communities in the coming decades as humanity increasingly becomes urbanised and removed from outdoor environments, while concurrently people must learn how to create, adapt, and live in urban environments in a greatly changed ecological and climatic context. It is also vital in social-justice oriented understandings of climate change adaptation interventions which is important in the diverse and complicated colonisation contexts of Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa Oceania.

Building from this understanding of a more holistic and locally contextualised kind of NbS for the wellbeing of Indigenous peoples, we now profile two case-study examples from Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa Oceania (from Aotearoa New Zealand and the Cook Islands) that have emerged from the NUWAO research project.

Research by Holman-Wharehoka (2023), who holds both Māori and Pākehā Whakapapa, looked to investigate the relationship between the built environment and climate change from a Te Ao Māori perspective, and to propose alternative ways to approach climate change adaptation planning by/with Māori. Key research aims were: to investigate how Māori wellbeing could be better reflected in climate adaptation design; and to investigate how the built environment can better reflect the reciprocal relationship that Māori have with Te Taiao. The concepts of sustainable engineering systems directly connect the built environment to Te Taiao, however the sector typically looks at non-human ecosystems purely for practical benefits or as a resource for humans. A Te Ao Māori perspective is more holistic and comes from lived experience and connection to Wāhi (place). The particular Wāhi/case study discussed in this research was Waiwhetū (Waiwhetū Stream), in Te Awa Kairangi (Lower Hutt); a setting that highlights the way the built environment over the past 180 years has colonised and degraded the wellbeing of the Awa and therefore has challenged the ability that Māori of Waiwhetū have to be Kaitiaki (guardians) of their Awa.

The central research methodology, founded in principles of a Kaupapa Māori framework (a by Māori, for Māori, with Māori approach) (Tuhiwai Smith, 2012), involved using Pūrākau (traditional Māori oral stories) to understand traditional knowledge in relation to dealing with extreme climate-related events such as flooding. Key findings of both literature review and interviews indicated that the writing of new Pūrākau, created to fit today’s context of time, society and climate, could embody a Kaupapa Māori approach to climate adaptation understanding and planning, drawing on Mātuaranga Māori, that would better reflect cultural values and therefore support wellbeing. This makes sense in the context of understanding that traditional knowledge is constantly evolving. The final aim of the research was therefore to explore the role of new Pūrākau as a way to begin design for climate adaptation in the built environment, including devising a new Pūrākau in collaboration with authors Te Kahureremoa Taumata and Khali-Meari Materoa to tell the story of the river’s changes in a first person narrative with the river as the central voice.

For Māori, everything is connected in a spiritual, mental, social, and physical sense. Central to the research was the understanding that Whenua, Awa, Wāhi Tapu (sacred sites) and Māori wellbeing are inseparable from Te Taiao (which includes climate). The Te Whare Tapa Whā model (Durie, 1995) provided a central conceptual framework for the research; highlighting the importance and interconnectedness of spiritual, mental, physical and family wellbeing for Māori, as well as Whenua, for “it is clear that without our land and roots to understand where we come from, we would be out of balance” (Holman-Wharehoka, 2023, p. 13).

The Pūrākau that was developed begins with an ode to Ranginui (the sky father), recognising the source of the Wai (water), that it is gifted from Ranginui to Pukeatua, the Maunga that Waiwhetū whakapapa to. The meaning of the name Waiwhetū is described in the Pūrākau; Wai, being water, and Whetū, being the stars, meaning the Awa is named for its ability to reflect the stars. The Pūrākau then describes the Awa in a pre-colonisation context, how big and deep it used to be, and that it was once a highway for Māori that would take Waka (Māori canoe) from the ocean into the Whenua. The Pūrākau then begins to discuss the emergence of Pākehā settlement and development, showing a noticeable shift in societal life and therefore a negative shift in the health of the Awa, and in turn the wellbeing of Waiwhetū Māori (Māori who whakapapa to Waiwhetū). The culverting of the Awa for urban development, with portions now hidden in underground pipes, is described. Overall, the Pūrākau intended to elucidate what it would feel like, from the perspective of the Awa, to go through this tremendous shift of life, from being nurtured to becoming desecrated. The Pūrākau ends with the following lines:

He taonga te wai Water is sacred

I whakarereā A treasure abandoned

Mā wai rā e taurima te ipukarea? Who will take care of the source?

Ko wai koe? Who are you? (You are water)

(Holman-Wharehoka, 2023, p. 95).

The degradation and lack of acknowledgement of the role the Awa plays for Māori are made manifest in the Pūrākau as consequences and impacts of climate change. The Pūrākau shows that if we want to ensure that the Awa can help to mitigate impacts such as floods, we need to return Mana (prestige and authority) to our Wai. The research is groundbreaking in the field of architectural science because it demonstrates how traditional knowledge and practice can be used to convey human-nature relationships and cultural values that in turn help to determine appropriate climate change adaptation strategies and ways of working with nature. It centers Māori worldview and priorities in urban design and planning, and makes it clear that the health of ecologies (in this case the Awa), climate, and people are not able to be separated and should be considered as interconnected parts of Te Taiao when trying to understand past, current and future conditions, and in relation to designing new interventions.

Within the context of today’s climate crisis, adaptation methods, including NbS, continue to develop and evolve. There is space within this development for Māori voices and Mātauranga to be at the centre of the conversation and decision making. A key finding of the research is that Mātauranga comes from and is used/given by Māori. It is not simply another formula for industry or government to “use;” it is a lived knowledge system that requires correct Tikanga (appropriate Māori customary practices and behaviours), guided by Kawa (governing protocol and policy).

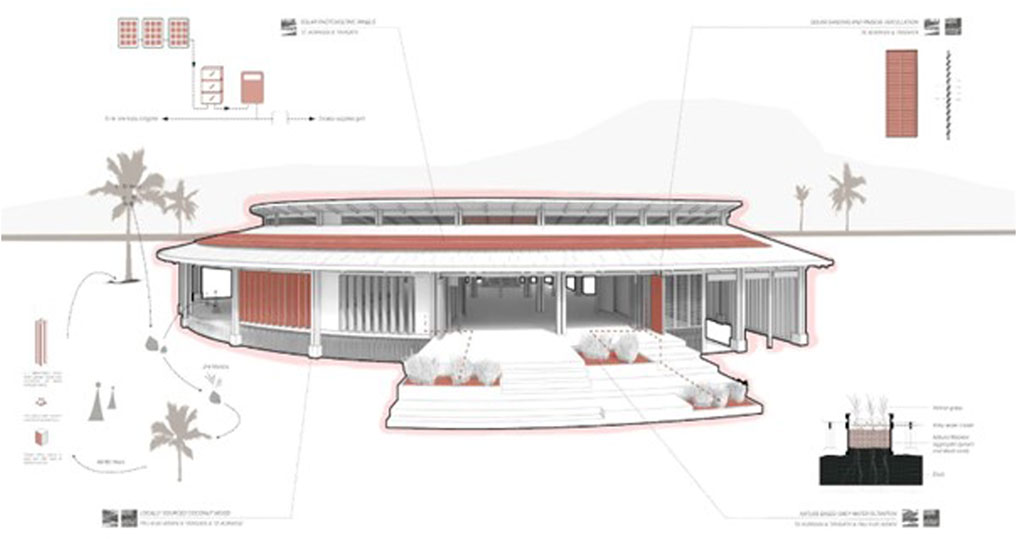

Mataroa’s research (2023) explored how Kuki Airani (Cook Islands) values can enable architecture that enhances the Oraanga Meitaki (wellbeing, health, and vitality) of Te Aorangi (the environment) and existing ecosystems. The research had four key aims: (i) to investigate how Kuki Airani values can reshape methods of designing architecture; (ii) to explore how Kuki Airani methods of design can contribute to the health and wellbeing of Kuki Airani Tangata (the community of the Cook Islands) and Te Aorangi; (iii) to understand the Kuki Airani relationship between wellbeing, Te Aorangi, and architecture; and (iv) to empower Kuki Airani Tangata (people) to apply their knowledge in architectural responses to climate change.

The research site was in Rarotonga, the largest of the Cook Islands. In recognition of the genealogical connections that Kuki Airani share with Te Aorangi, the selected site belongs to the researcher’s Kopu Tangata (family). Located in the western district of Arorangi, the site lies next to the shore and beneath the Maunga (mountain) of Raemaru. This area faces many challenges such as storm surges, cyclones, increasing sea temperatures and surface run-off. Despite a trend towards purely technical responses to the impacts of climate change seen in many nations of the Pacific where European or Australasian aid money is the basis of much climate adaptation infrastructure works (such as the building of sea walls for example), traditional knowledge concerning living with the Enua (land) and Moana (ocean) has been passed down from generation to generation, allowing Airani Tangata to adapt to many of these challenges. As a means to reiterate the importance of ‘working with’ nature and Indigenous knowledges, recognising conceptions of wellbeing in the Pacific, rather than a “doing to” method (a technical only lens), prioritisation of this traditional Kuki Airani knowledge was a key aim of the research. Kuki Airani cultural values and traditional knowledge shaped a design process that worked with nature to adapt to climate change and began to address many of these challenges.

As discussed, wellbeing in Pacific contexts refers to more than just the individual. The Rarotonga research centered wellbeing as a concept that radiates out to all other existing life forms, or the essence of being (Ministry of Social Development, 2012; Feek and Kepa Brian Morgan, 2013; Mahi Maioro Professionals, 2021). As discussed by Tavioni (2018), Atua (Gods) can manifest in many aspects, such as seasons, Maunga and Moana, demonstrating how every component of Te Aorangi shares a life force and requires consideration when designing in Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa Oceania. The research understood wellbeing as Oraanga Meitaki and it was explored as the spiritual, physical, and emotional wellness of all life forces, from Tangata (people), to the Atua (god/s), and existing ecosystems of Te Aorangi (Ministry of Social Development, 2012). Oraanga Meitaki resonates with the intergenerational responsibility that Kuki Airani share in protecting, preserving and caring for their homeland, and enables connections to be made between the design of space and Oraanga Meitaki.

Climate adaptation in urban contexts within the Pacific is often approached with a Eurocentric perspective, separating environmental and climate impacts from human occupation and economic potential. While sustainable design frameworks have been utilised within Rarotonga, there is an urgent need to prioritise local values, traditional knowledge and regenerative design strategies over the commonly accepted standards of sustainability in architectural discourse (Mataroa, 2023). A shift towards improving the Oraanga Meitaki of Te Aorangi demands simultaneous consideration of the spiritual, emotional, and physical impacts of a design. The unique contribution of this research is the development of the Te Aorangi framework; conceived to address design issues in Rarotonga by identifying connections between the Atua, Tangata and Te Aorangi. Derived from cultural Tivaevae (a traditional Kuki Airani tapestry) values, the framework sought to enhance the Oraanga Meitaki of spaces and challenged the current perception of what architecture can and should achieve. Prioritisation of Oraanga Meitaki within the framework can result in architectural solutions that improve and enhance the ecological landscape of Te Aorangi, as opposed to merely sustaining current degraded levels.

Through a decolonisation lens, the research explored how Kuki Airani values can empower Tangata to reclaim their approach to climate adaptation by re-shaping the architectural processes of designing environmentally responsive architecture in Rarotonga. Overall, a shift towards holistic, context-specific architectural processes in Rarotonga would enhance the Oraanga Meitaki of Te Aorangi, existing ecologies, and hence the Oraanga Meitaki of Kuki Airani Tangata, and also ensure that Peu Kuki Airani (the culture of the Cook Islands) is celebrated and preserved for future generations. The design-led research demonstrated that by using Indigenous knowledge and understandings of human-nature relationships personified as Atua, as a means to generate a regenerative architectural design framework, and resulting designs for a community centre (Figures 2, 3), both the processes and outcomes of design can centre Indigenous values and priorities while having adaptation and wellbeing outcomes.

FIGURE 2. Design for a Community Centre in Rarotonga derived through te aorangi framework (Source: Mataroa, 2023).

FIGURE 3. Design for a Community Centre in Rarotonga derived through Te Aorangi framework (Source: Mataroa, 2023).

The urgent need to adapt to climate change is clear and is of great importance in Oceania, where some of the most globally vulnerable peoples in relation to the impacts of climate change reside, and where human wellbeing is disproportionately affected. NbS could and in some places in Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa Oceania do already play a key role, enabling multiple co-benefits to evolve that focus on revitalising ecological health, and (if designed well) improving wellbeing. The next step in creating effective NbS, we argue, is to make sure that they contribute to culturally appropriate and just climate adaptation, leading to outcomes that support cultural values and self-determination for Indigenous people (Kiddle et al., 2021; Latai-Niusulu et al., 2022). Without this key cultural lens at the forefront of design and planning, adaptation is not supporting “a good life” and could lead to further marginalisation of Indigenous peoples. In short, NbS need to be localised not only in terms of ecological and climatic site conditions, but also cultural knowledge and values to be effective.

Ideas and worldviews related to human-nature relationships influence the design of NbS. It is clear that Indigenous peoples of Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa Oceania have different relationships with nature compared to each other, but holistic concepts of ecological-human roles, values, and relationships differ hugely when compared to typical European or North American ideas about how people and nature can or should interact. This is where many “standardisations” of NbS terms and processes come from however. This means there is a clear need to reassess how NbS fit into a wider local agenda of wellbeing, particularly for Indigenous peoples, and in the case of this research, Indigenous peoples of Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa Oceania. Without this framework of reference NbS can become accidental vehicles of neo-colonisation and actually undermine wellbeing for Indigenous people.

Overall, as for other Indigenous peoples globally, in Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa Oceania, Indigenous wellbeing tends to be holistic, relational and collective in nature. Indigenous people tend to have broader, more holistic approaches to wellbeing that centre the environment, spirituality, and the connectedness of all; or what is known in Aotearoa New Zealand as collective Waiora. Indigenous worldviews and cosmologies position humans as inseparable from the Earth and often oceans and/or from ecosystems. Ecological and climate wellbeing are not separable. This understanding of a kind of life force that binds all living aspects of the world (including rivers, oceans, mountains, forests and other “entities” not often acknowledged as being alive in western science) has varying names in Oceania including: Mauri (Aotearoa New Zealand), Mo’ui (Tonga), Mauli (Hawaii) and Oraanaga Meitaki (Cook Islands) (Krupa, 1996). The Mauri of rivers has been recognised in Aotearoa New Zealand for example, through granting of legal personhood to the Whanganui River as a means of Te Ao Māori-centred care for and management of the ecologies associated with these entities (in this case the river) that better reflects their meaning and Mana (Charpleix, 2018). In short, wellbeing for Indigenous peoples is not considered in isolation, but rather in the broader context that the individual sits within. As we have shown, there are many models of wellbeing in Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa Oceania that differ (but often are linked) that can and should influence urban and built environment design and climate change adaptation planning and interventions. How then can the design of NbS acknowledge, celebrate and work with such an understanding of the living world in order to centre local wellbeing? Our findings, including the examples provided by the tow case studies, indicate that it is not just the technical measurable outcomes of NbS that determine their compatibility with this worldview, but the overall frameworks of relational understanding, and the processes undertaken to arrive at and evolve NbS that are important.

The influence of colonisation, and resulting wide adherence to Christian perspectives and values in the Pacific, is significant and important to discuss in this context because there is potentially tension between climate action and some religious doctrines. For example, and in particular, the Judaeo-Christian tradition of human uniqueness compared to all other species and consequent licence of human dominion over nature, as expressed in parts of the Bible, has often been seen as leading to environmental devastation (White, 1967). There is now, however, strong and diverse involvement of Christians and people of other faiths involved in climate change and resilience responses in Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa Oceania (Creegan and Shepherd, 2018; Purdie, 2022). Luetz and Nunn (2020) describe how climate change decision-making in Pacific Island nations is more likely to be influenced by tradition and local practice (including the highly-respected teachings of religious leaders) than by science.

In juxtaposition to the religious belief of human dominion over nature, a significant stream in religious thinking that is often termed “eco-theology” (Deane-Drummond, 2008) has arisen. Eco-theology can be seen as a form of constructive theology that focuses on the interrelationships of religion and nature, particularly in the light of environmental concerns. As such, eco-theology has drawn significant thinking from the concepts of traditional ecological knowledge, especially in terms of the intrinsic and holistic relationship between humankind and the natural environment. Nunn et al. (2016), surveying a large sample of University of South Pacific students, found that nearly 90% of respondents reported feeling part of Nature, having a personal connection with the natural environment, and thought their welfare was linked to Nature. Participants had spiritual values that explained their feelings of connectedness to Nature. In theological as well as cultural framing this relationship of oneness with nature also leads towards holistic wellbeing (Mayer and Frantz, 2004; Tomlinson, 2019; Vaai, 2019; Whitburn et al., 2020; Barragan-Jason et al., 2022) while addressing colonial and neo-colonial paradigms (Pacific Conference of Churches, 2001).

Pacific peoples’ understandings of wellbeing and identity are grounded in relationships and collectivism (Lautua, 2023). In Aotearoa New Zealand, the relationships between Whenua, Maunga, Ngāhere (forests) and Atua are life-affirming (Pomare-Peta, 2022). Gelves-Gómez and Brincat (2021) discuss similar holistic concepts associated with the Fijian word Vanua (territory, place) and relate these concepts to wellbeing, quoting (Ravuvu (1987): “For to live well in this world and in the other world, one has to live according to Vanua beliefs and values….” Fihaki (2022) and Pomare-Patea (ibid) also consider that both the recognition of the concept of stewardship in the Bible, and the subsequent actions of stewardship, bring increased Hauora (health). In the Judeao-Christian tradition those actions of stewardship, including climate adaptation, are often collectively called “Creation care.” As such, there have been calls for the inclusion of faith-based approaches and opportunities in climate adaptation and wellbeing, that go beyond the secular. Luetz and Nunn (2020), for example, describe how current climate responses in Moana-nui-a-Kiwa Oceania Oceania have been hindered by previous technocratic approaches rooted in a secular and binary view of humans in nature, and quote Hulme (2017), summarising his international reviews, exhorting that “climate policies need to tap into intrinsic, deeply-held values and motives if cultural innovation and change are to be lasting and effective.”

Climate change is the most significant health and wellbeing issue of our times, with Indigenous people disproportionately affected. NbS play a key role in adapting to climate change; bringing multiple co-benefits and critically focusing on revitalising ecological health. Culturally appropriate NbS also need to be informed by localised understandings of wellbeing. As we have discussed, for the Indigenous people of Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa Oceania Oceania, these understandings are many, but are linked by centring human-ecological relationships and connections, spirituality, and the connectedness of all.

The two case studies discussed in this article illustrate the importance of appropriate research methods, design frameworks and design that forefront Indigenous values, knowledge, and wellbeing in the creation of NbS that centre local practices of wellbeing. More consciously considering worldview and cultural values during (co) designing processes will make these adaptation strategies, including NbS, more locally relevant, effective, and likely to have positive wellbeing outcomes for interconnected socio-ecological systems. There is a clear need for standardisations of NbS terms, methods, and evaluation frameworks to be flexible enough to be relevant to specific localised contexts, particularly where Indigenous peoples reside. There is need for further research on the intersection of spiritual and religious beliefs and models of human wellbeing in Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa Oceania, as also noted by Gelves-Gómez and Brincat (2021).

The case studies highlight that working with nature in the context of Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa Oceania is not simply a technical exercise, but a deeply meaningful, potentially spiritual, and certainly a political act in the context of decolonisation and re-Indigenisation. People seeking to employ NbS in Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa Oceania should be aware of this in planning, design, and participatory processes, overall design goals and outcomes, and ongoing maintenance planning. The further development of a framework to guide NbS work in Moana-nui-a-Kiwa Oceania will be the subject of ongoing research. The motivation and positionality behind NbS design for climate adaptation that centres worldview-driven local ideas and practices of wellbeing is of vital importance to effectiveness in the Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa Oceania context and should be made transparent by funders, designers and planners, managers, and other actors involved in design for climate adaptation.

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving humans were approved by the Victoria University of Wellington Human Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

SM: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing–original draft. M-t-oH-W: Investigation, Writing–original draft. JM: Investigation, Writing–original draft. GK: Investigation, Writing–original draft, Conceptualization, Writing–review and editing. MP: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. PB: Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. SB: Writing–review and editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by a Marsden grant (20-VUW-058) from the Marsden Fund Te Pūtea Rangahau a Marsden. Te Pūtea Rangahau a Marsden is managed by Royal Society Te Apārangi on behalf of the New Zealand Government with funding from the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment. The funder played no role in the conceptualisation, development, undertaking, or analysis of the research.

We would like to acknowledge funding from the Marsden Fund–Royal Society of New Zealand.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1Established to examine social conditions in Aotearoa New Zealand and recommend policies that would result in a more just and fair society.

2A permanent commission of inquiry in Aotearoa New Zealand that makes recommendations on claims brought by Māori relating to Crown actions which breach the promises made in Te Tiriti o Waitangi (the Te Reo Māori version of the Treaty of Waitangi)—Aotearoa New Zealand’s founding document.

Aerts, R., Honnay, O., and Van Nieuwenhuyse, A. (2018). Biodiversity and human health: mechanisms and evidence of the positive health effects of diversity in nature and green spaces. Br. Med. Bull. 127, 5–22. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldy021

Alam, M., Ali, M. F., Kundra, S., Nabobo-Baba, U., and Alam, M. A. (2022). “Climate change and health impacts in the South Pacific: a systematic review,” in Ecological footprints of climate change. Editors U. Chatterjee, A. O. Akanwa, S. Kumar, S. K. Singh, and A. Dutta Roy (Cham: Springer Climate. Springer). doi:10.1007/978-3-031-15501-7_29

Anderson, A., Binney, J., and Harris, A. (2015). Tangata whenua: a history. Wellington, New Zealand: Bridget Williams Books.

Aslany, M., and Brincat, S. (2021). Class and climate-change adaptation in rural India: beyond community-based adaptation models. Sustain. Dev. 29 (3), 571–582. doi:10.1002/sd.2201

Bailey-Winiata, A. P. S. (2021). Understanding the potential Exposure of coastal Marae and urupā in Aotearoa new Zealand to sea level rise. Doctoral dissertation. Hamilton, New Zealand: The University of Waikato

Barragan-Jason, G., de Mazancourt, C., Parmesan, C., Singer, M. C., and Loreau, M. (2022). Human–nature connectedness as a pathway to sustainability: a global meta-analysis. Conserv. Lett. 15 (1), e12852. doi:10.1111/conl.12852

Berman, M. G., Jonides, J., and Kaplan, S. (2008). The cognitive benefits of interacting with nature. Psychol. Sci. 19, 1207–1212. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02225.x

Charpleix, L. (2018). The Whanganui River as Te Awa Tupua: place-based law in a legally pluralistic society. Geogr. J. 184 (1), 19–30. doi:10.1111/geoj.12238

Cohen-Cline, H., Turkheimer, E., and Duncan, G. E. (2015). Access to green space, physical activity and mental health: a twin study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 69, 523–529. doi:10.1136/jech-2014-204667

Cohen-Shacham, E., Walters, G., Janzen, C., and Maginnis, S. (2016). Nature-based solutions to address global societal challenges, 97. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN, 2016–2036.

Costello, A., Abbas, M., Allen, A., Ball, S., Bell, S., Bellamy, R., et al. (2009). Managing the health effects of climate change: lancet and university College London institute for global health commission. Lancet 373 (9676), 1693–1733. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(09)60935-1

N. H. Creegan, and A. Shepherd (2018). Creation and hope: reflections on ecological anticipation and action from Aotearoa New Zealand (Eugene, Oregon, United States: Wipf and Stock Publishers).

Department of Strategic Policy, Planning and Aid Coordination (2017). Vanuatu 2030 – the people’s plan. National sustainable development plan 2016-2030. Monitoring and evaluation framework.

Derby, M. (2023). Waitangi tribunal – Te rōpū whakamana - developing the tribunal. 1980s', Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Available at: http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/waitangi-tribunal-te-ropu-whakamana/page-2.

Durie, M. (1994). Whaiaora—Māori health development. Auckland, New Zealand: Oxford University Press.

Durie, M. H. (1985). A Maori perspective of health. Soc. Sci. Med. 20 (5), 483–486. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(85)90363-6

Feek, A., and Kepa Brian Morgan, T. K. (2013). Mauri model analysis. Mahi Maioro Professionals. Available at: https://www.maurimodel.nz/about-1.

Fiji Bureau of Statistics (2023). in Population by religion - 2007 census of population. Retrieved 13.12.2023 Available at: https://www.statsfiji.gov.fj/statistics/social-statistics/religion.

Gelves-Gómez, F., and Brincat, S. (2021). “Leveraging Vanua: metaphysics, nature, and climate change adaptation in Fiji,” in Beyond belief. Climate change management. Editors J. M. Luetz, and P. D. Nunn (Cham: Springer). doi:10.1007/978-3-030-67602-5_4

Gibson, K. E., Barnett, J., Haslam, N., and Kaplan, I. (2020). The mental health impacts of climate change: findings from a Pacific Island atoll nation. J. Anxiety Disord. 73, 102237. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102237

Gillis, K., and Gatersleben, B. (2015). A review of psychological literature on the health and wellbeing benefits of biophilic design. Buildings 5, 948–963. doi:10.3390/buildings5030948

Hartig, T., Mitchell, R., De Vries, S., and Frumkin, H. (2014). Nature and health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 35, 207–228. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182443

Hikuroa, D. (2017). Mātauranga Māori—the ūkaipō of knowledge in New Zealand. J. R. Soc. N. Z. 47 (1), 5–10. doi:10.1080/03036758.2016.1252407

Holman-Wharehoka, M. (2023). Investigating the relationship between the built environment and climate change from a Te āo Māori perspective using Pūrākau as a methodology with the case study of Waiwhetū awa. Wellington, New Zealand: Victoria University of Wellington.

International Union for Conservation of Nature (Iucn), (2023). Nature-based solutions. Available at: https://www.iucn.org/our-work/nature-based-solutions.

Jones, R., Bennett, H., Keating, G., and Blaiklock, A. (2014). Climate change and the right to health for Maori in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Health & Hum. Rights J. 16, 54–68.

Kiddle, G. L., Bakineti, T., Latai-Niusulu, A., Missack, W., Pedersen Zari, M., Kiddle, R., et al. (2021b). Nature-based solutions for urban climate change adaptation and wellbeing: evidence and opportunities from Kiribati, Samoa, and Vanuatu. Front. Environ. Sci. 9, 442. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2021.723166

Kiddle, G. L., Pedersen Zari, M., Blaschke, P., Chanse, V., and Kiddle, R. (2021a). An Oceania urban design agenda linking ecosystem services, nature-based solutions, traditional ecological knowledge and wellbeing. Sustainability 13 (22), 12660. doi:10.3390/su132212660

Krupa, V. (1996). Life and health, disease, and death. A cognitive analysis of the conceptual domain. Asian Afr. Stud. 5 (1), 3–13.

Kuo, F. E., and Sullivan, W. C. (2001). Environment and crime in the inner city: does vegetation reduce crime? Environ. Behav. 33, 343–367. doi:10.1177/00139160121973025

Kupa, K. (2009). Te Vaka Atafaga: a Tokelau assessment model for supporting holistic mental health practice with Tokelau people in Aotearoa, New Zealand. Pac. Health Dialog 15 (1), 156–163.

Latai-Niusulu, A., Nel, E., and Binns, T. (2020). Positionality and protocol in field research: undertaking community-based investigations in Samoa. Asia Pac. Viewp. 61 (1), 71–84. doi:10.1111/apv.12252

Latai-Niusulu, A., Taua’a, S., Kiddle, G. L., Pedersen Zari, M., Blaschke, P., and Chanse, V. (2022). “Traditional nature-based architecture and landscape design: lessons from Samoa and Wider Oceania,” in Creating resilient landscapes in an era of climate change (Oxon and New York: Routledge), 194–216.

Lautua, T. (2023). A pacific qualitative methodology for the intersection of images of god, cultural identity and mental wellbeing. J. Pastor. Theol. 33, 171–188. doi:10.1080/10649867.2023.2225955

Levy, B. S., Sidel, V. W., and Patz, J. A. (2017). Climate change and collective violence. Annu. Rev. Public Health 38, 241–257. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044232

Luetz, J. M., and Nunn, P. D. (2020). Managing climate change adaptation in the pacific region. Springer Link, 293–311.

Mahi Maioro Professionals (2021). Climate change adaptation in the Pacific Islands: a review of faith-engaged approaches and opportunities. in The Mauri model. Mahi Maioro Professionals. Online: Kepa.Maori.Nz. Available at: https://www.maurimodel.nz/about-1.

Malvatumauri National Council of Chiefs (2012). Alternative indicators of well-being for Melanesia. in Vanuatu pilot study report.

Mataroa, J. (2023). Towards Te aorangi; A Kuki Airani Framework for Design in Rarotonga: How can prioritisation of the Kuki Airani (Cook Islands) Tivaevae values enable architecture that enhances the Oraanga Meitaki (Wellbeing and quality of life) of Te aorangi (the environment)? Masters thesis. Wellington, New Zealand: Victoria University of Wellington.

Mayer, F. S., and Frantz, C. M. (2004). The connectedness to nature scale: a measure of individuals’ feeling in community with nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 24 (4), 503–515. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2004.10.001

McAllister, T. G., Beggs, J. R., Ogilvie, S. C., Kirikiri, R., Black, A., and Wehi, P. M. (2019). Kua takoto te mānuka: mātauranga Māori in New Zealand ecology. New Zealand Journal of Ecology 43(3), 1–7. doi:10.20417/nzjecol.43.41

McFarlane, R. A., Horwitz, P., Arabena, K., Capon, A., Jenkins, A., Jupiter, S., et al. (2019). Ecosystem services for human health in Oceania. Ecosyst. Serv. 39, 100976. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2019.100976

McIver, L., Kim, R., Woodward, A., Hales, S., Spickett, J., Katscherian, D., et al. (2016). Health impacts of climate change in Pacific Island countries: a regional assessment of vulnerabilities and adaptation priorities. Environ. Health Perspect. 124 (11), 1707–1714. doi:10.1289/ehp.1509756

Ministry for the Environment, (2022). Aotearoa New Zealand’s first national adaptation plan. Wellington: Ministry for the Environment. Available at: https://environment.govt.nz/assets/publications/climate-change/MFE-AoG-20664-GF-National-Adaptation-Plan-2022-WEB.pdf.

Ministry of Social Development, (2012). Turanga māori—a Cook Islands conceptual framework transforming family violence—restoring wellbeing. Available at: http://archive.org/details/pasefika-proud-resource-ngavaka-o-kaiga-tapu-pacific-framework-cook-islands.

Moewaka Barnes, H., and McCreanor, T. (2019). Colonisation, hauora and whenua in Aotearoa. J. R. Soc. N. Z. 49 (Suppl. 1), 19–33. doi:10.1080/03036758.2019.1668439

Nurse, L. A., Mclean, R. F., Agard, J., Briguglio, L. P., Duvat-Magnan, V., et al. (2014). “Small islands,” in Climate change 2014: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Part B: regional aspects. Contribution of working group II to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Editors V. R. Barros, C. B. Field, D. J. Dokken, M. D. Mastrandrea, K. J. Mach, T. E. Biliret al. (Cambridge University Press), 1613–1654. hal-01090.

Pacific Conference of Churches (2001). Island of hope: an alternative to economic globalisation. Geneva: World Council of Churches.

Panelli, R., and Tipa, G. (2007). Placing well-being: a Maori case study of cultural and environmental specificity. EcoHealth 4, 445–460. doi:10.1007/s10393-007-0133-1

Pedersen Zari, M. (2019). Understanding and designing nature experiences in cities: a framework for biophilic urbanism. Cities Health 7 (2), 201–212. doi:10.1080/23748834.2019.1695511

Pedersen Zari, M., MacKinnon, M., Varshney, K., and Bakshi, N. (2022). Regenerative living cities and the urban climate–biodiversity–wellbeing nexus. Nat. Clim. Change 12 (7), 601–604. doi:10.1038/s41558-022-01390-w

Pomara-Petia, M. (2022). “Tiakina te Taiao, tiakina te iwi,” in Awhi mai awhi atu: women in creation care. Editor Purdie, 232–245.

Powell, T., and Fraser, J. (1892). The Samoan story of creation: a tala. J. Polyn. Soc. 1 (3), 164–189.

Pulotu-Endemann, F. K. (2001). A pacific model of health: the Fonofale model. Central PHO pacific cultural guidelines. Available at: http://www.centralpho.org.nz/Portals/0/Publications/Health%20Services/Pacific%20Cultural%20Guidelines.

Purdie, S. (2022). Awhi mai awhi atu: women in creation care. Wellington: Philip Garside Publishing Ltd.

Ravuvu, A. (1987). The Fijian ethos. Suva, Fiji: Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific, Fiji.

Redvers, N., Poelina, A., Schultz, C., Kobei, D. M., Githaiga, C., Perdrisat, M., et al. (2020). Indigenous natural and first law in planetary health. Challenges 11 (2), 29. doi:10.3390/challe11020029

Rodgers, M., Mercier, O. R., Kiddle, R., Pedersen Zari, M., and Robertson, N. (2023). Plants of place: justice through (re) planting Aotearoa New Zealand's urban natural heritage. Architecture_MPS 25 (1). doi:10.14324/111.444.amps.2023v25i1.001

Romanello, M., Di Napoli, C., Drummond, P., Green, C., Kennard, H., Lampard, P., et al. (2022). The 2022 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: health at the mercy of fossil fuels. Lancet 400 (10363), 1619–1654. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(22)01540-9

Royal Society Te Aparangi (2017). Human health impacts of climate change for New Zealand: evidence summary. Wellington, NewZealand: Royal Society Te Aparangi.

Ryks, J., Simmonds, N., and Whitehead, J. (2019). The health and wellbeing of urban Māori in Aotearoa New Zealand. ,” in Vojnovic I, Pearson AL, Gershim A, Deverteuil G, Allen A, (eds) (Routledge: New York: Handbook of Global Urban Health), 283–96.

Sangha, K. K., Preece, L., Villarreal-Rosas, J., Kegamba, J. J., Paudyal, K., Warmenhoven, T., et al. (2018). An ecosystem services framework to evaluate indigenous and local peoples’ connections with nature. Ecosyst. Serv. 31, 111–125. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2018.03.017

Scheyvens, R., Hardy, A., de Waegh, R., and Trifan, C. A. (2023a). “Well-being and resilience,” in Islands and resilience: experiences from the pandemic era (Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore), 35–51.

Scheyvens, R., Movono, A., and Auckram, J. (2023b). Enhanced wellbeing of Pacific Island peoples during the pandemic? A qualitative analysis using the Advanced Frangipani Framework. Int. J. Wellbeing 13 (1), 59–78. doi:10.5502/ijw.v13i1.2539

Scheyvens, R. A., Movono, A., and Auckram, S. (2023c). Pacific peoples and the pandemic: exploring multiple well-beings of people in tourism-dependent communities. J. Sustain. Tour. 31 (1), 111–130. doi:10.1080/09669582.2021.1970757

Smith, K. R., Woodward, A., Campbell-Lendrum, D., Chadee, D., Honda, Y., Liu, Q., et al. (2014). “Human health: impacts, adaptation, and co-benefits,” in Climate change 2014: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability contribution of Working Group II to the fifth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. C. B. Field, V. R. Barros, D. J. Dokken, K. J. Mach, M. D. Mastrandrea, T. E. Biliret al. (New York: Cambridge University Press), 709–754.

Soderlund, J., and Newman, P. (2015). Biophilic architecture: a review of the rationale and outcomes. AIMS Environ. Sci. 2, 950–969. doi:10.3934/environsci.2015.4.950

Statistics New Zealand (2019). 2018 census totals by topic. Available at: https://www.stats.govt.nz/2018-census/.

Tanguay, J. (2014). Alternative indicators of well-being for Melanesia: changing the way progress is measured in the South Pacific. Devpolicy blog. 21 May. Available at: https://devpolicy.org/alternative-indicators-of-well-being-for-melanesia-changing-the-way-progress-is-measured-in-the-south-pacific-20140521/.

Tavioni, M. (2018). Tāura ki te Atua—the role of ’akairo in Cook Islands Art. Auckland, New Zealand: Thesis, Auckland University of Technology. Available at: https://openrepository.aut.ac.nz/handle/10292/11594.

Thom, R. R. M., and Grimes, A. (2022). Land loss and the intergenerational transmission of wellbeing: the experience of iwi in Aotearoa New Zealand. Soc. Sci. Med. 296, 114804. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114804

Thomsen, S., Tavita, J., and Zsontell, L. (2018). A pacific perspective on the living standards framework and wellbeing. Aotearoa New Zealand Treasury Discussion Paper, 18/09. Available at: https://treasury.govt.nz/publications/dp/dp-18-09.

Tiatia, J., Langridge, F., Newport, C., Underhill-Sem, Y., and Woodward, A. (2022). Climate change, mental health and wellbeing: privileging Pacific peoples’ perspectives–phase one. Clim. Dev. 15, 655–666. doi:10.1080/17565529.2022.2145171

Tiatia-Seath, J., Tupou, T., and Fookes, I. (2020). Climate change, mental health, and well-being for Pacific peoples: a literature review. Contemp. Pac. 32 (2), 399–430. doi:10.1353/cp.2020.0035

Tomlinson, M. (2019). The pacific way of development and christian theology. Sites A J. Soc. Anthropol. Cult. Stud. 16 (1). doi:10.11157/sites-id428

Tuhiwai Smith, L. (2012). Decolonizing methodologies: research and indigenous peoples. Dunedin: Otago University Press.

Tukuitonga, C., and Vivili, P. (2021). Climate effects on health in small islands developing states. Lancet Planet. Health 5 (2), e69–e70. doi:10.1016/s2542-5196(21)00004-8

Tyrväinen, L., Ojala, A., Korpela, K., Lanki, T., Tsunetsugu, Y., and Kagawa, T. (2014). The influence of urban green environments on stress relief measures: a field experiment. J. Environ. Psychol. 38, 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2013.12.005

United Nations, (2016). State of the world's indigenous peoples: indigenous peoples' access to health services. February.

United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP) (2019). Ocean cities regional policy guide. Bangkok: UNESCAP. Available at: https://www.unescap.org/resources/ocean-cities-regional-policy-guide.

United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (2011). Who are Indigenous peoples? Factsheet. Available at: https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/5session_factsheet1.pdf.

Vaai, U. L. (2019). "We are therefore we live": pacific eco-relational spirituality and changing the climate change story. Tokyo, Japan: Toda Peace Institute. Policy Brief No. 56, October.

Whitburn, J., Linklater, W., and Abrahamse, W. (2020). Meta-analysis of human connection to nature and proenvironmental behavior. Conserv. Biol. 34 (1), 180–193. doi:10.1111/cobi.13381

White, L. (1967). The historical roots of our ecologic crisis. Science 155 (3767), 1203–1207. doi:10.1126/science.155.3767.1203

Woodward, A., and Porter, J. R. (2016). Food, hunger, health, and climate change. Lancet 387 (10031), 1886–1887. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)00349-4

World Health Organization, (2021). Climate Change and health. 30 october. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/climate-change-and-health.

Xuande, F., and Yuting, G. (2021). An analysis of the tuna diplomacy between pacific island countries and EU-take Kiribati as an example. in E3S web of conferences, EDP Sciences 251, 01071. doi:10.1051/e3sconf/202125101071

Yates, A., Dombroski, K., and Dionsio, R. (2022). Dialogues for wellbeing in an ecological emergency: wellbeing-led governance frameworks and transformative Indigenous tools. Dialogues Hum. Geogr., 1–20. doi:10.1177/20438206221102957

Yates, A., Pedersen Zari, M., Bloomfield, S., Burgess, A., Walker, C., Waghorn, K., et al. (2023) A transformative architectural pedagogy and tool for a time of converging crises. Urban Sci., 7, 1. doi:10.3390/urbansci7010001

Keywords: wellbeing, adaptation, nature-based solutions, Aotearoa New Zealand, Cook Islands, Indigenous people

Citation: Mihaere S, Holman-Wharehoka M-t-o, Mataroa J, Kiddle GL, Pedersen Zari M, Blaschke P and Bloomfield S (2024) Centring localised indigenous concepts of wellbeing in urban nature-based solutions for climate change adaptation: case-studies from Aotearoa New Zealand and the Cook Islands. Front. Environ. Sci. 12:1278235. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2024.1278235

Received: 16 August 2023; Accepted: 18 January 2024;

Published: 02 February 2024.

Edited by:

Bo Hong, Northwest A&F University, ChinaReviewed by:

Minh-Hoang Nguyen, Phenikaa University, VietnamCopyright © 2024 Mihaere, Holman-Wharehoka, Mataroa, Kiddle, Pedersen Zari, Blaschke and Bloomfield. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Maibritt Pedersen Zari, bWFpYnJpdHQucGVkZXJzZW4uemFyaUBhdXQuYWMubno=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.