- 1School of Cultural Industry and Tourism, Xiamen University of Technology, Xiamen, China

- 2Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China

- 3School of Civil Engineering, Putian University, Putian, China

- 4School of Computer and Information Engineering, Xiamen University of Technology, Xiamen, China

Informal development, as a unique phenomenon that has become widespread in China’s urbanization process in recent years, has continued to attract the attention of both the government and academia. Existing studies focus on urban village redevelopment strategies, and little research has been conducted on informal development in urban villages under the land property approach. In particular, research needs to further explore what impact China’s collective land property rights have had on informality in urban villages. This study mainly adopts a qualitative research method, including field observation and in-depth interviews. The research was conducted in urban villages in Guangzhou. The study finds that land property rights have an important impact on urbanization and property rights arrangements have an important impact on resource allocation efficiency. Due to the ambiguity of collective land property rights in China, informal development in urban villages is the result of the collective action of villagers, government, and enterprises under the stimulation of economic development. The interaction of the stakeholders has promoted the rapid development of informal housing in urban villages.

1 Introduction

Since the reform and opening up, China has undergone rapid urbanization. Two different types of urbanization—“top-down” urbanization led by urban governments and “bottom-up” urbanization led by village collectives (Deng and Huang, 2004). Village-based urbanization usually occurs in peri-urban areas between central cities and suburbs and dominates the transformation of economic structures, social relations, and physical landscapes (Tian, 2015). Many autonomous villages have formally or informally converted agricultural land to non-agricultural land, increasing competition for land with urban governments (Wang et al., 2018). A large number of existing discussions on urban villages have focused on the impact of the dualistic land system on urban villages’ transformation (Wang et al., 2009; Hao et al., 2011) and the exploration of transformation policies (He et al., 2010; Tang, 2015; van Oostrum, 2021).

There is a lack of research on urban villages, particularly those that focus on the redevelopment strategies of urban villages (Hin and Xin, 2011; Wu et al., 2013; Li et al., 2014; Lai and Tang, 2016; Yuan et al., 2020; Pan and Du, 2021). however, urban village redevelopment is difficult because collective land use rights are mostly scattered among multiple land users and have formed a stable interest pattern. Especially, under the traditional state-led land development system, the redevelopment of collective land is subject to great resistance, and it is necessary to further investigate the transformation mechanism. The purpose of the paper is the need to further explore the impact of the ambiguity of collective land property rights on village development. This study focuses on why urban villages can continuously adapt to market demand and thus diversify their business models, thereby promoting sustainable village development. The impact of informal land property rights on the spatial development of villages needs to be further explored.

Land property rights system refers to the institutional regulation of the composition of a country’s land property rights system and the way it is implemented. It is the general term for all economic relations of all economic subjects to land and all economic relations between different economic subjects arising from the relations of economic subjects to land. A large number of scholars have introduced new institutional economics into the field of urban planning, and the research has focused on two directions: transaction costs and property rights governance (Alexander, 1992; Webster, 1998; Lai and Tang, 2016). The research system of new institutional economics is huge, and it updates welfare economics in terms of assumptions, and derives from the concept of transaction costs as the main object of study, with contracts as the main object, and the economics of transaction costs and property rights. Since then, the concept of transaction costs and analytical methods have been applied in different planning fields (e.g., land use planning, housing, and land development) (Darabi and Jalali, 2018), with specific issues including value capture (Hong, 1998), land price mechanisms (Needham and de Kam, 2004), land development processes (Buitelaar, 2004), governance structures for land conversion (Chung, 1994; Tan et al., 2012), and redevelopment plans (Lai and Tang, 2016). The purpose of the institutional cost of urban development is to reduce transaction costs. In the new institutional economics paradigm, urban planning is no longer a simple act of public intervention but is linked to institutional design. The key to institutional analysis is to analyze the transaction costs of different institutions. The differences in transaction time, space, cultural practices, and institutional environment of cities in the development process reflect different characteristics, and the core of the institutional analysis is to find the most appropriate governance system. The institution that minimizes the total cost for all parties is the optimal one (Alexander, 1992). The current state-led land development transaction costs have become very high, and collective land redevelopment interests are intricate and difficult to coordinate. While redeveloping collective land in urban areas offers a favorable opportunity to exploit the surplus of land rents in a new phase of urbanization, local governments bear extremely high transaction costs in the land redevelopment process under the traditional state-led institutional arrangements (Lai et al., 2017).

The study provides a relevant reference for the redevelopment of urban villages in China. The academic understanding of the value of informal development should be reconsidered as village-led land development adopts a market-oriented approach that allows land development to adapt to market demand and present a diverse range of businesses. Village informal development plays a more important and diverse role in China’s urbanization, and its value should be valued by academics. Village-led land development behaviors and spatial impacts should be recognized in the process of high-quality urbanization in China, without unilaterally considering urbanized development under the state-led system.

The first section of this paper introduces the study’s background and the need to further investigate the mechanisms of transformation, as collective land development has met with significant resistance under the traditional state-dominated land development system. The second section introduces land redevelopment in the context of China’s dualistic land system and provides the theoretical analytical framework for this paper. The third section explains the informality and ambiguity of collective land property rights through the case of village development in Guangzhou, which adopts a more market-oriented development model and continuously adjusts to market demand to form diversified business forms for the village’s long-term prosperity. The 4 section concludes the paper by providing a relevant reference for urban village renewal in China, arguing that village-led land development adopts a market-oriented model that allows land development to adapt to market demand and present diverse business forms, and thus should reconsider academic understanding of informal development values.

2 Institutional perspective on the land development process in urban China

Since the 1990s, both developed and developing countries have been undergoing enormous economic and social institutional transformations. Transition is a complex process that involves profound changes in many economic and social fields, and is an area of very important concern for global academics. The most important institutional transformations in the developed Western countries today are reflected in three main areas: the globalization of the way the economy is organized, the shift from Fordism to post-Fordism in the mode of production, and the change in the mode of governance to the strengthening of civil society. Unlike the path of transformation in the West, and quite different from the overall developmental decline that resulted from radical reforms in the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, China’s institutional transformation is considered pragmatism and gradualism. China is currently undergoing one of the largest and most complex development transitions in the world, and “a variety of external and internal irregularities are having a profound impact on urban space, making traditional planning research and classical theories of planning unable to explain the rapid changes in Chinese urban space (Yang et al., 2023a).

Chinese cities have witnessed the emergence of new urban properties and the creation of new urban spaces: “informal, disordered spaces”, which emerge as a result of the ambiguity and incompleteness of property rights. The city is not only a vehicle for economic activity but also the growth, combination, and transmutation of urban forces that emphatically react to economic and social processes. This interactive process constantly drives the reconfiguration of urban space and institutional changes. The complexity of China’s urban space is caused by the dualistic design of China’s land-rural property rights system, the coexistence of a dualistic system during China’s transition to a market system, the non-completeness and ambiguity of rural collective land property rights, and the transformation of institutional patterns and accumulation mechanisms during the reform period. This has led to a large number of non-regulatory behaviors and rent-seeking activities of different interest groups, leaving institutional space for various non-regulatory economic rent-seeking activities (Shen, 2007; Yang et al., 2023a).

Douglass C North advocates the division of institutions into formal and informal institutions. Formal institutions refer to a series of policy laws created by people consciously, including laws, rules, regulations, etc., Informal institutions refer to the agreed and common codes of conduct that people gradually form in the process of long-term social interaction and are recognized by society, including value beliefs, customs, cultural traditions, moral ethics, ideology, etc. Institutional change refers to the change or replacement of the original institutional arrangement or the innovation of the institutional arrangement. Institutional change can be broadly classified into two types: induced institutional change and mandatory institutional change. The so-called induced institutional change refers to the institutional change that is, spontaneously advocated, organized, and realized by an individual or a group of people who are induced by the profit opportunity of the new system. The so-called compulsory institutional change refers to the system change that is, introduced by government orders and laws. The government is the main body of institutional change, which is top-down, rapid, radical, and compulsory (North, 1986).

From the perspective of property rights, land development rights are the direct target of the public policy of urban planning, and the status of land development rights is closely related to the urban planning system. The status of land development rights is closely related to the urban planning system. Land development rights in China during the transition period are characterized by the fact that the right to dispose of land development is owned by the state, and the state also has a strong right to expropriate it; while the right to benefit from land development is heavily owned by the state. The state also has a strong right of expropriation, while the right to the benefits of land development is located in a large number of “public spheres” of property rights, as Bazel put it. The right to develop the land is also a strong right of expropriation by the state, while the right to benefit from land development is located in a large part in what Bazel calls the “public domain” of property rights. Urban planning defines land development rights based on two objectives: first, urban planning is an institutional tool for rulers to maximize the monopoly rent of land; second, urban planning is an institutional tool for rulers to maximize the monopoly rent of land. First, urban planning is an institutional tool for rulers to maximize the monopoly rents of land; and second, urban planning provides an effective system of property rights to maximize the rulers’ tax revenues. These two objectives are often inconsistent. These two goals are often inconsistent, and the status of land development rights in China has exacerbated this contradiction, making urban planning face an institutional This contradiction is exacerbated by the state of land development rights in China, making urban planning an institutional dilemma (North and Weingast, 1989).

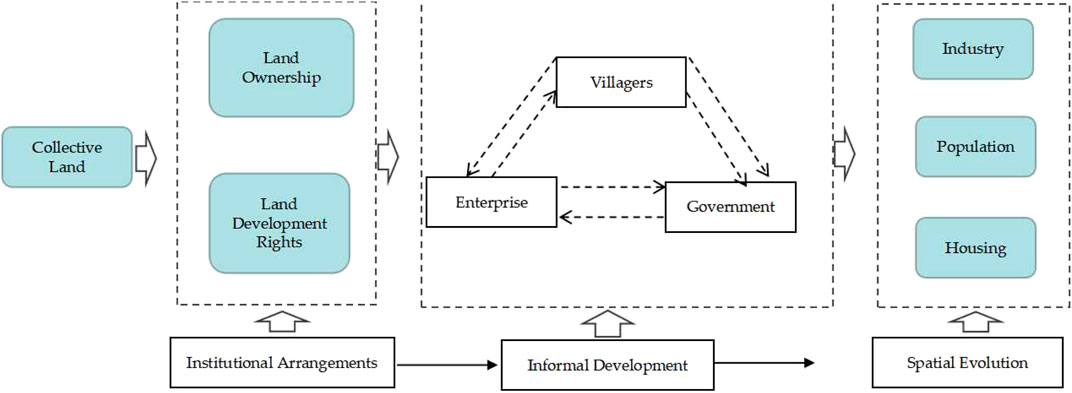

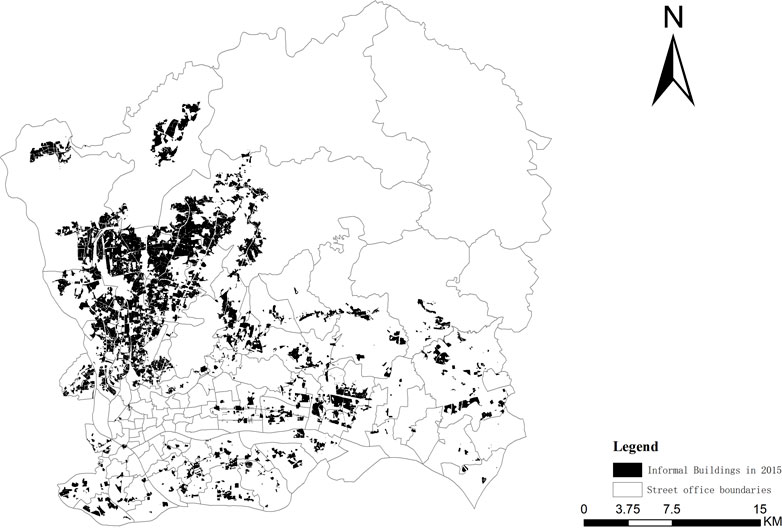

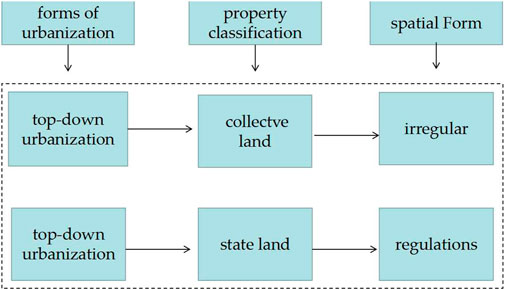

With the transformation of China’s urban growth pattern, land redevelopment is gradually replacing new district development as a way of urban space reuse in large cities in economically developed regions. Under the unique urban dual land ownership system, cities include two parts urban areas (state land ownership) and urban villages (collective land ownership). The development of urban villages is a product of land replacement and urban development (Liu and Wong, 2018; Ren, 2018; Zhao and Zhang, 2018; Li et al., 2021); residents of these areas have incomplete property rights and can only gain revenue by adding properties to collective land, and the urbanization of villages has led to low levels of infrastructure development, disorder, and crowded living environments. The concept of informal development distinguishes urban villages from formal state-led urban development and provides a useful perspective on the development of urban villages. Previous research has extensively investigated urban village redevelopment strategies (Zhao, 2017; Wang, 2022; Zhou et al., 2022). Urban villages have the substandard infrastructure and built environments, and most are difficult to rebuild and revitalize, impeding the city’s overall development (Changqing et al., 2007; Gu et al., 2023; Hu et al., 2023). Less attention has been paid to the non-informal development of land in urban villages, particularly the development outlets of well-located urban villages. The results of existing research on urban villages are the result of informal development under the institutional arrangement of collective land property rights (Figure 1). However, the impact of land property rights informality on the spatial development of villages needs to be further explored.

3 Study area and research methodology

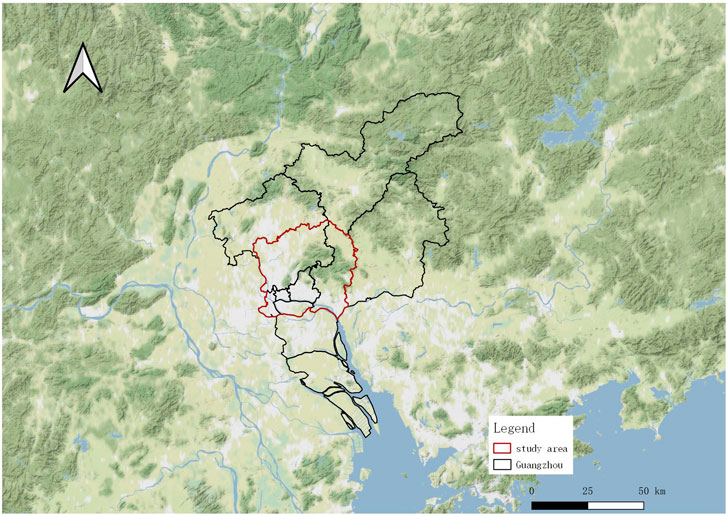

Guangzhou is the capital of Guangdong Province, the political, economic, scientific, educational, and cultural center of the province, a famous coastal open city in China, and a national pilot area for comprehensive reform, located in the south of China, the southeastern part of Guangdong Province and the northern edge of the Pearl River Delta. Guangzhou is therefore known as the “Southern Gate” of China. Guangzhou is governed by Yuexiu District, Haizhu District, Liwan District, Tianhe District, Baiyun District, Huangpu District, Panyu District, Huadu District, Zengcheng District, and Conghua District. At the beginning of the reform and opening up, Guangzhou’s built-up area was only 54.4 square kilometers, with an average of 33,000 people per kilometer. The scope of this research is selected as Yuexiu, Haizhu, Tianhe, Huangpu, Fangcun, Liwan, and Baiyun districts in Guangzhou (Figure 2). The development of collective land and state-owned land in this area is a mosaic. This interactive process constantly promotes the reconstruction of urban space and institutional changes.

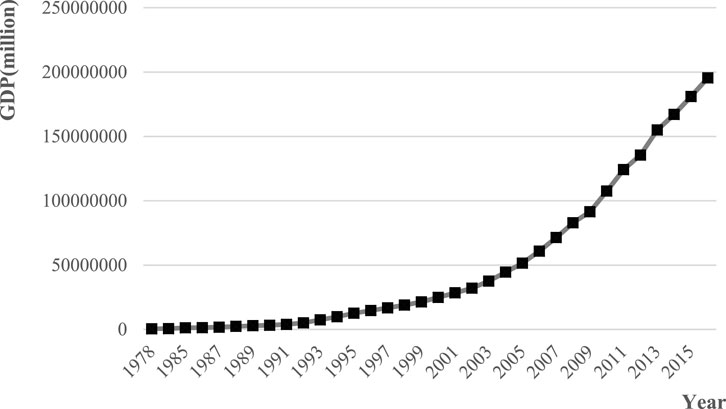

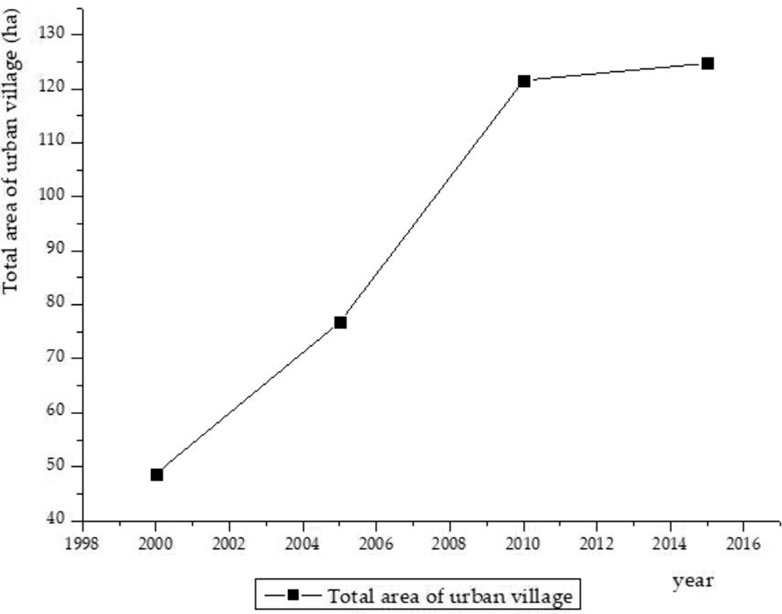

Guangzhou was chosen for the empirical study. Guangzhou, a reformed and open city on the Chinese coast, has been urbanized rapidly since 1978 and has been called the Red Capitalism of South China (Lin, 1997). Guangzhou’s economy has achieved rapid development from 1978 to 2015 (Figure 3). It has attracted a large number of investors from Hong Kong to set up factories in Guangzhou since the early 1980s due to its geographical location and its proximity to Hong Kong and Macau, as a result of lower labor and land costs in Guangzhou. This process has enabled Guangzhou to rise rapidly, with rapid economic development and urban spatial expansion. Like other cities in China, Guangzhou’s urbanization process is based on the typical dual system of urban and rural areas. As a result of the ‘land rent surplus’ between state-owned land with full property rights and rural collective land with ambiguous property rights, the urban government and the rural collective government have the incentive to maximize this surplus. Both rural-led development and state-led development drive urban expansion, rural de-farming, and the formation of urban villages. Guangzhou thus provides a suitable case for studying the impact of two different types of institutions on urban spatial expansion.

This study mainly used qualitative research methods, including field observation, in-depth interviews, and textual analysis methods. The researcher visited Haizhu District, Tianhe District, and Baiyun District villages in November, December 2018, and January 2019. First, the researcher visited the existing residents of Fenghe Village. On this basis, the researcher focused on observing the changes in the village’s class structure, the interaction between different subjects, and their impact on the village landscape, and recorded them in the form of an observation diary. In addition, the researcher conducted in-depth interviews with a total of 30 respondents in the village, divided into three categories: villagers, village committee, and outsiders. The main purpose of the interviews was to obtain information about the 30 interviewees in the village, the perceptions of demographic and landscape changes, land, and tourism development, as well as the perceptions and attitudes of different subjects toward physical, cultural, and social changes in the village.

4 Informal development in urban villages under land property right

4.1 The general development process of urban villages in Guangzhou

The Pearl River Delta is at the forefront of China’s reform and opening up, creating a miracle of economic development and rapidly expanding urban construction land. With the transformation of the economy and the development of new urbanization, the past era of massive land acquisition in the suburbs will not be sustainable. In recent years, the central government’s strict control of urban land sales and the awakening of farmers’ awareness of the land value in rural areas have made land acquisition difficult. These two factors have forced the Chinese government to shift from rural land acquisition to urban renewal.

The enormous expansion of urban space in Guangzhou can demonstrate the impact of institutional arrangements on the development of urban villages and their role in urban development. Rural-led land development was widespread, resulting in a large number of urban villages in Guangzhou, forming a ‘mosaic space’ with the formal urban areas created by state land ownership.

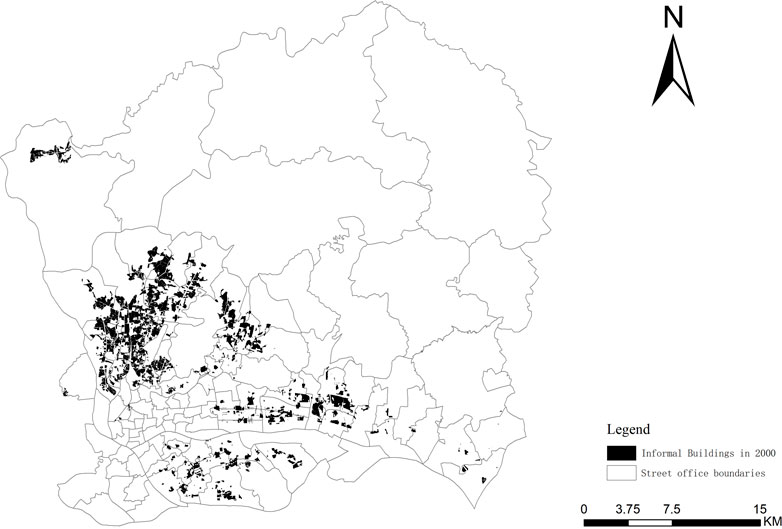

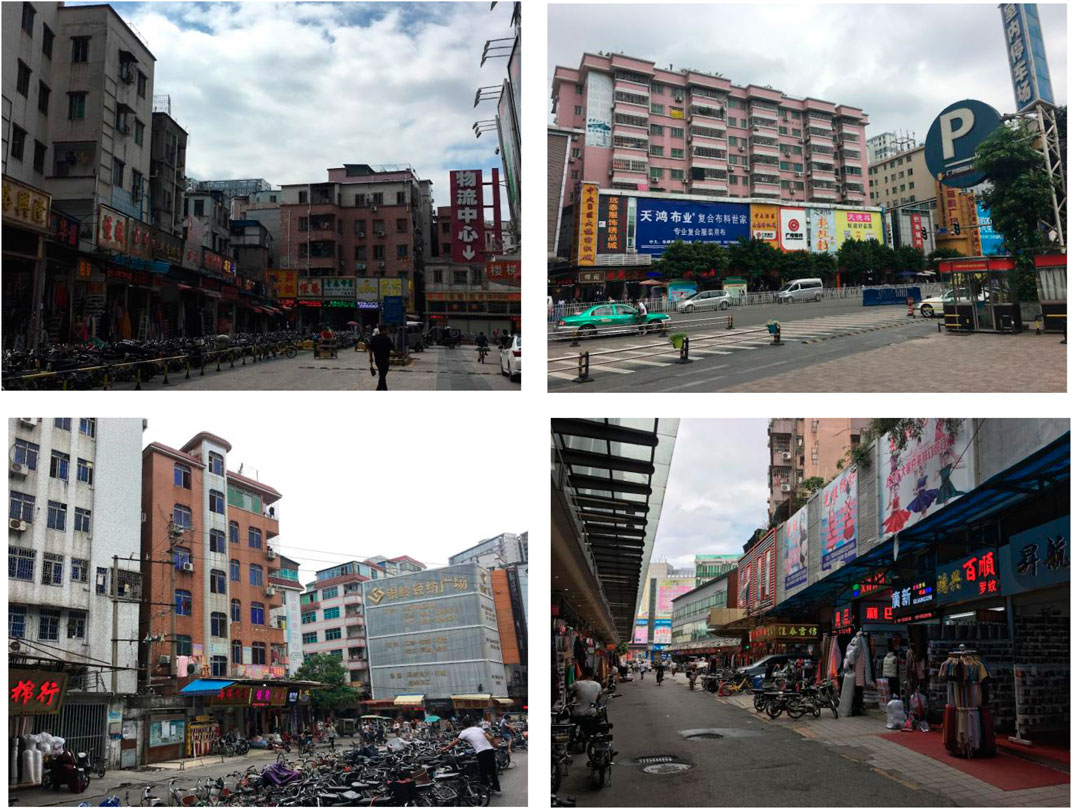

Guangzhou has made great achievements in the accumulation of 3 decades of economic development. However, due to the difference between the urban-rural dual system and the lag of the management system, with time, a large number of village collective properties and farmers’ homesteads have been built. Residential houses are faced with the need for renovation, and the legal approval procedures are out of touch with reality, resulting in a large number of buildings outside the supervision of laws and regulations and government policies and regulations, forming so-called “formally developed” commercial houses and “self-developed” villagers’ houses, collective properties, etc. The situation of “village in the city” and “city beside the village”, such as informal development, coexist and influence each other. Redevelopment of land in urban villages is a costly project. By extracting urban construction land through high-definition remote sensing and using machine learning based on the characteristics of urban village land (Yang et al., 2022a; Yang et al., 2022c), we finally extracted the land area and location of urban villages in the central urban area of Guangzhou in 2000,2005,2010,2015 and compared the growth of urban village land (Figures 4, 5). A comparison of the data shows that Guangzhou has seen a rapid development of urban villages in the city since 2000, with rapid economic development and a large increase in housing demand from migrant workers (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6. Growth of urban village area from 2000 to 2015 in Guangzhou (Source: Drawn by the authors).

4.2 Developers and villagers cooperate in collective land development driven by profit

Since 1978, China has undergone rapid urbanization (Yang, 2019; Ao et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2020a; Yang et al., 2020b). The rapid growth of buildings is accompanied by a large influx of people with residential needs (He et al., 2018; He, 2019; Liu et al., 2019). Two different types of urbanization coexist, top-down urbanization led by urban governments, and bottom-up urbanization led by rural villages (Figure 7). These two types of urbanization have rapidly driven the rapid expansion of Guangzhou’s urban area. Relying on the government’s financial input alone cannot meet the huge capital demand, while developers with strong financial resources can solve this problem. The pursuit of profit maximization is the fundamental starting point of all commercial behavior. Developers participate in urban village redevelopment projects with the same goal of obtaining high profits. Urban villages are better located and their redevelopment will provide real estate developers with quality land resources to satisfy their profit pursuit under the increasingly tight urban land supply.

Villagers are one of the subjects most affected by the urban village transformation. According to field interviews and understanding, on the one hand, villagers hope to improve their quality of life by improving the infrastructure and living conditions in the village through redevelopment because they have been living in urban villages with the poor living environment, hygiene conditions, and security conditions for a long time; on the other hand, villagers worry that redevelopment will harm their vested economic interests. First of all, whether the economic income from housing rental and business environment that depend on the urban periphery can be protected during the redevelopment process is the main concern of the villagers.

The reform and opening up of China, on the one hand, a large number of township enterprises and private enterprises have developed rapidly, and the demand for simple industrial factories and stores along the streets has surged, however, the lack of such demand by the government has led to the emergence of a large number of informal settlements. On the other hand, economic development has promoted the flow of population and materials between urban and rural areas, and a large number of migrant workers and business people have gathered in rapidly urbanizing areas.

The economic affordability of these floating populations is often low, and the temporary nature of their living is such that “urban village” rental housing meets the housing needs of a large number of migrant workers. As a result, economic development objectively requires a large number of simple and cheap production and living places, and informal settlements cater to this objective market. The objective demand of the market and the profit-seeking instinct of market players have stimulated the disorderly supply of informal settlements. On the one hand, a small number of people, especially developers, to obtain more revenue, build without obtaining administrative permission from the planning department, or do not carry out development and construction under administrative permission, such as breaking through the approved plot ratio, sacrificing greenery, squares, car parks, and other public facilities without permission, lowering the daylight spacing ratio, increasing the intensity of development, and pursuing high profits. And in the current context of soaring real estate prices, developers illegally building excess area gains huge, illegal construction costs are low and enforcement costs are high, illegal construction is often “punished in place of demolition”, the penalty amount is only 5%–10% of the cost of illegal construction works.

4.3 China’s urban-rural land system shapes the space for urban-rural mixing

The deficiencies of the current land system in China are a major reason for the prevalence of informal construction (Yang et al., 2023b). Based on the dual land system between urban and rural areas caused by historical reasons in China, there is a huge price scissor difference between rural collective land and urban construction land; the land use system practiced in China makes the government monopolize the primary land market, the only way to urbanize rural land is through state expropriation, and there is a serious lack of property and development rights of rural collective land (Ding, 2003; Lin and Ho, 2005; Dong et al., 2021; Dai et al., 2022; Hui et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2023b). The land expropriation system makes the value added in the process of urbanization of rural collective land mainly dominated by the government; at the same time, the subjects of property rights of rural collective land are blurred and fall into a situation where “everyone has a share” and “no one has a share". Due to the huge demand for economic development, housing in urban villages is developing rapidly (Figure 8).

The implementation of the collective land institution has fully safeguarded the interests of the state and has contributed significantly to the rapid urbanization and development of cities in China (Cai, 2003; Tian and Zhu, 2013; Wang et al., 2015; Kong et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2022a). However, it also leads to the following consequences: on the one hand, local governments are tempted to obtain huge land financial gains through massive expropriation of rural land, falling into a strange circle where the more land the government expropriates, the more it benefits, while rural collectives and farmers suffer greater losses (Xie et al., 2016; Huang, 2018; Gong and Tan, 2021; Yang et al., 2022b; Yang et al., 2022c); on the other hand, as it is difficult for the government to fully protect the real interests of collectives and farmers through massive expropriation, it is often not fully understood and supported by collectives and farmers, and rural collectives and farmers in some areas often resist through informal construction.

5 Discussion and conclusion

Under China’s current land system, the existing model of urban village transformation has not only increased the conflicts between the government and the villagers in the urban villages but also often prevented the mobile population from living in the cities after urban village transformation. Therefore, taking into account China’s national conditions and international experience, we should innovate the land system based on the premise of land ownership, to effectively transform the infrastructure, urban landscape, and comprehensively improve the level of public services in urban villages, and continue to play the role of informal development of “urban villages” to provide low-cost housing for the low-income urban class and the external mobile population. The role of the informal development of “urban villages” in providing low-cost and quality housing for the urban low-income class and the external mobile population.

This study uses an institutional analysis approach in land development to analyze how the ambiguity of land property rights affects the impact of informal development in urban villages. Informal development, as a unique phenomenon that has become widespread in China’s urbanization process in recent years, has continued to attract the attention of both the government and academia. The development of urban villages is considered to be the result of informality, the lack of suboptimal state regulatory options, and institutional constraints on collective land property rights. The concept of informal development distinguishes urban villages from formal state-led urban development and provides a useful perspective on the development of urban villages, which as a result of existing research is the result of informal development under the institutional arrangement of collective land property rights.

The impact of informality on urban village land redevelopment needs to be further explored. The study finds that land property rights have an important impact on urbanization and property rights arrangements have an important impact on resource allocation efficiency. Due to the ambiguity of collective land property rights in China, informal development in urban villages is the result of the collective action of villagers, government, and enterprises under the stimulation of economic development. The interaction of the three parties has promoted the rapid development of informal housing in urban villages. This study provides a relevant reference for urban village regeneration in China. The informal development of urban villages plays an important role in the role of urbanization in China and is an important part of urbanization, which adapts to the development needs of different development stages of urbanization. Its value should be valued by academics.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, JY, HM, and JW; methodology, JY; writing—original draft preparation, JY, and YH; writing—review and editing, JY, and HM; Funding acquisition, HM, and JY All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program of the CAS, Pan-Third Pole Environment Study for a Green Silk Road, No.XDA20040402, the Fujian Social Science Fund (grant numberFJ2021C036), and the Fujian Provincial Department of Education Fund (grant numberJAS19312).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alexander, E. R. (1992). A transaction cost theory of planning. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 58 (2), 190–200. doi:10.1080/01944369208975793

Ao, Y., Zhang, Y., Wang, Y., Chen, Y., and Yang, L. (2020). Influences of rural built environment on travel mode choice of rural residents: The case of rural sichuan. J. Transp. Geogr. 85, 102708. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2020.102708

Buitelaar, E. (2004). A transaction-cost analysis of the land development process. Urban Stud. 4113, 2539–2553. doi:10.1080/0042098042000294556

Cai, Y. (2003). Collective ownership or cadres' ownership? The non-agricultural use of farmland in China. China Q. 175, 662–680. doi:10.1017/s0305741003000890

Changqing, Q., Kreibich, V., and Baumgart, S. (2007). Informal elements in urban growth regulation in China–urban villages in Ningbo. Asien 103, 23–44.

Chung, L. L. W. (1994). The economics of land-use zoning: A literature review and analysis of the work of coase. Town Plan. Rev. 65 (1), 77. doi:10.3828/tpr.65.1.j15rh7037v511127

Dai, D., Yang, J., and Rao, Y. (2022). Spatial-temporal evolution of industrial land transformation effect in eastern China. Front. Environ. Sci. 10, 975510. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2022.975510

Darabi, H., and Jalali, D. (2018). Illuminating the formal–informal dichotomy in land development on the basis of transaction cost theory. Plan. Theory 18, 100–121. doi:10.1177/1473095218779111

Deng, F. F., and Huang, Y. (2004). Uneven land reform and urban sprawl in China: The case of beijing. Prog. Plan. 61 (3), 211–236. doi:10.1016/j.progress.2003.10.004

Ding, C. (2003). Land policy reform in China: Assessment and prospects. Land use policy 20 (2), 109–120. doi:10.1016/s0264-8377(02)00073-x

Dong, L., Shang, J., Ali, R., and Rehman, R. U. (2021). The coupling coordinated relationship between new-type urbanization, eco-environment and its driving mechanism: A case of guanzhong, China. Front. Environ. Sci. 9, 638891. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2021.638891

Gong, Y., and Tan, R. (2021). Emergence of local collective action for land adjustment in land consolidation in China: An archetype analysis. Landsc. Urban Plan. 214, 104160. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2021.104160

Gu, S., Li, J., Wang, M., and Ma, H. (2023). Post-renewal evaluation of an urbanized village with cultural resources based on multi public satisfaction: A case study of nantou ancient city in shenzhen. Land 12 (1), 211. doi:10.3390/land12010211

Hao, P., Sliuzas, R., and Geertman, S. (2011). The development and redevelopment of urban villages in Shenzhen. Habitat Int. 35 (2), 214–224. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2010.09.001

He, B. J. (2019). Towards the next generation of green building for urban heat island mitigation: Zero UHI impact building. Sustain. Cities Soc. 50, 101647. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2019.101647

He, B. J., Zhao, D. X., Zhu, J., Darko, A., and Gou, Z. H. (2018). Promoting and implementing urban sustainability in China: An integration of sustainable initiatives at different urban scales. Habitat Int. 82, 83–93. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2018.10.001

He, S., Liu, Y., Wu, F., and Webster, C. (2010). Social groups and housing differentiation in China's urban villages: An institutional interpretation. Hous. Stud. 25 (5), 671–691. doi:10.1080/02673037.2010.483585

Hin, L. L., and Xin, L. (2011). Redevelopment of urban villages in Shenzhen, China–An analysis of power relations and urban coalitions. Habitat Int. 35 (3), 426–434. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2010.12.001

Hong, Y-H. (1998). Transaction costs of allocating increased land value under public leasehold systems: Hong Kong. Urban Stud. 359, 1577–1595. doi:10.1080/0042098984295

Hu, D., Zeng, J., Chen, J., Lin, W., Xiao, X., Feng, M., et al. (2023). Microbiological quality of roof tank water in an urban village in southeastern China. J. Environ. Sci. 125, 148–159. doi:10.1016/j.jes.2022.01.036

Huang, L. (2018). From benign unconstitutionality to delegated legislation: Analysis on the ways for legal reform of China rural collective construction land circulation. Habitat Int. 74, 36–47. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2018.02.008

Hui, C., Shen, F., Tong, L., Zhang, J., and Liu, B. (2022). Fiscal pressure and air pollution in resource-dependent cities: Evidence from China. Front. Environ. Sci. 10, 908490. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2022.908490

Kong, X., Liu, Y., Jiang, P., Tian, Y., and Zou, Y. (2018). A novel framework for rural homestead land transfer under collective ownership in China. Land Use Policy 78, 138–146. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.06.046

Lai, Y., and Tang, B. (2016). Institutional barriers to redevelopment of urban villages in China: A transaction cost perspective. Land Use Policy 58, 482–490. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.08.009

Lai, Y., Wang, J., and Lok, W. (2017). Redefining property rights over collective land in the urban redevelopment of Shenzhen, China. Land Use Policy 69, 485–493. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.09.046

Li, B., Tong, D., Wu, Y., and Li, G. (2021). Government-backed ‘laundering of the grey’in upgrading urban village properties: Ningmeng apartment project in Shuiwei village, Shenzhen, China. Prog. Plan. 146, 100436. doi:10.1016/j.progress.2019.100436

Li, L. H., Lin, J., Li, X., and Wu, F. (2014). Redevelopment of urban village in China–A step towards an effective urban policy? A case study of liede village in Guangzhou. Habitat Int. 43, 299–308. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2014.03.009

Lin, G. C. S., and Ho, S. P. S. (2005). The state, land system, and land development processes in contemporary China. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 95 (2), 411–436. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.2005.00467.x

Lin, G. C. S. (1997). Red capitalism in south China: Growth and development of the Pearl River Delta. University of British Columbia Press.

Liu, R., and Wong, T. C. (2018). Urban village redevelopment in Beijing: The state-dominated formalization of informal housing. Cities 72, 160–172. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2017.08.008

Liu, Z., Liu, Y., He, B. J., Xu, W., Jin, G., and Zhang, X. (2019). Application and suitability analysis of the key technologies in nearly zero energy buildings in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 101, 329–345. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2018.11.023

Needham, B., and de Kam, G. (2004). Understanding how land is exchanged: Co-ordination mechanisms and transaction costs. Urban Stud. 4110, 2061–2076. doi:10.1080/0042098042000256387

North, D. C. (1986). The new institutional economics. J. Institutional Theor. Econ. 142 (1), 230–237.

North, D. C., and Weingast, B. R. (1989). Constitutions and commitment: The evolution of institutions governing public choice in seventeenth-century england. J. Econ. Hist. 49 (4), 803–832. doi:10.1017/s0022050700009451

Pan, W., and Du, J. (2021). Towards sustainable urban transition: A critical review of strategies and policies of urban village renewal in shenzhen, China. Land Use Policy 111, 105744. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105744

Ren, X. (2018). Governing the informal: Housing policies over informal settlements in China, India, and Brazil. Hous. Policy Debate 28 (1), 79–93. doi:10.1080/10511482.2016.1247105

Shen, J. (2007). Scale, state and the city: Urban transformation in post-reform China. Habitat Int. 31 (3-4), 303–316. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2007.04.001

Tan, R., Beckmann, V., Qu, F., and Wu, C. (2012). Governing farmland conversion for urban development from the perspective of transaction cost economics. Urban Stud. 4910, 2265–2283. doi:10.1177/0042098011423564

Tang, B. (2015). Not rural but not urban”: Community governance in China's urban villages. China Q. 223, 724–744. doi:10.1017/s0305741015000843

Tian, L. (2015). Land use dynamics driven by rural industrialization and land finance in the peri-urban areas of China:“The examples of Jiangyin and Shunde”. Land Use Policy 45, 117–127. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.01.006

Tian, L., and Zhu, J. (2013). Clarification of collective land rights and its impact on non-agricultural land use in the Pearl River Delta of China: A case of shunde. Cities 35, 190–199. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2013.07.003

van Oostrum, M. (2021). Access, density and mix of informal settlement: Comparing urban villages in China and India. Cities 117, 103334. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2021.103334

Wang, B., Tian, L., and Yao, Z. (2018). Institutional uncertainty, fragmented urbanization and spatial lock-in of the peri-urban area of China: A case of industrial land redevelopment in Panyu. Land Use Policy 72, 241–249. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.12.054

Wang, C. (2022). Do planning concepts matter? A lacanian interpretation of the urban village in a British context. Plan. Theory 21 (2), 155–180. doi:10.1177/14730952211038936

Wang, Q., Zhang, X., Wu, Y., and Skitmore, M. (2015). Collective land system in China: Congenital flaw or acquired irrational weakness? Habitat Int. 50, 226–233. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.08.035

Wang, Y. P., Wang, Y., and Wu, J. (2009). Urbanization and informal development in China: Urban villages in Shenzhen. Int. J. Urban Regional Res. 33 (4), 957–973. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2009.00891.x

Webster, C. J. (1998). Public choice, Pigouvian and Coasian planning theory. Urban Stud. 35 (1), 53–75. doi:10.1080/0042098985078

Wu, F., Zhang, F., and Webster, C. (2013). Informality and the development and demolition of urban villages in the Chinese peri-urban area. Urban Stud. 50 (10), 1919–1934. doi:10.1177/0042098012466600

Xie, L., Berck, P., and Xu, J. (2016). The effect on forestation of the collective forest tenure reform in China. China Econ. Rev. 38, 116–129. doi:10.1016/j.chieco.2015.12.005

Yang, J., He, Z., and Ma, H. (2022b). Comparison of collective-led and state-led land development in China from the perspective of institutional arrangements: The case of Guangzhou. Land 11 (2), 226. doi:10.3390/land11020226

Yang, J., Yang, L., and Ma, H. (2022a). Community participation strategy for sustainable urban regeneration in Xiamen, China. Land 11 (5), 600. doi:10.3390/land11050600

Yang, L., Chau, K. W., Szeto, W. Y., Cui, X., and Wang, X. (2020). Accessibility to transit, by transit, and property prices: Spatially varying relationships. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 85, 102387. doi:10.1016/j.trd.2020.102387

Yang, L. (2019). Evaluating the urban land use plan with transit accessibility. Sustain. cities Soc. 45, 474–485. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2018.11.042

Yang, L., Liang, Y., He, B., Lu, Y., and Gou, Z. (2022c). COVID-19 effects on property markets: The pandemic decreases the implicit price of metro accessibility. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 125, 104528. doi:10.1016/j.tust.2022.104528

Yang, L., Liang, Y., He, B., Yang, H., and Lin, D. (2023). COVID-19 moderates the association between to-metro and by-metro accessibility and house prices. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 114, 103571. doi:10.1016/j.trd.2022.103571

Yang, L., Wang, X., Sun, G., and Li, Y. (2020). Modeling the perception of walking environmental quality in a traffic-free tourist destination. J. Travel & Tour. Mark. 37 (5), 608–623. doi:10.1080/10548408.2019.1598534

Yang, L., Yu, B., Liang, Y., Lu, Y., and Li, W. (2023). Time-varying and non-linear associations between metro ridership and the built environment. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 132, 104931. doi:10.1016/j.tust.2022.104931

Yuan, D., Yau, Y., Bao, H., and Lin, W. (2020). A framework for understanding the institutional arrangements of urban village redevelopment projects in China. Land Use Policy 99, 104998. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104998

Zhao, P. (2017). An ‘unceasing war’on land development on the urban fringe of beijing: A case study of gated informal housing communities. Cities 60, 139–146. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2016.07.004

Zhao, P., and Zhang, M. (2018). Informal suburbanization in Beijing: An investigation of informal gated communities on the urban fringe. Habitat Int. 77, 130–142. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2018.01.006

Keywords: land property rights, informal development, collective land, urban village, Guangzhou

Citation: Yang J, Ma H, Fu W and He Y (2023) Impact of land property rights on the informal development of urban villages in China: The case of Guangzhou. Front. Environ. Sci. 11:1138511. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2023.1138511

Received: 05 January 2023; Accepted: 17 February 2023;

Published: 02 March 2023.

Edited by:

Yibin Ao, Chengdu University of Technology, ChinaReviewed by:

Fenghua Wen, Central University of Finance and Economics, ChinaXiongbin Lin, Ningbo University, China

Copyright © 2023 Yang, Ma, Fu and He. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Haitao Ma, bWFodEBpZ3NucnIuYWMuY24=; Wenjie Fu, ZndqQHB0dS5lZHUuY24=

Jinkun Yang

Jinkun Yang Haitao Ma2*

Haitao Ma2*