- 1National Research Council, Institute for Electromagnetic Sensing of the Environment, CNR-IREA, Milan, Italy

- 2University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, Cambridge, MD, United States

- 3National Research Council, Institute of Marine Sciences, CNR-ISMAR, Venice, Italy

- 4Council for Agricultural Research and Economics, Research Centre for Plant Protection and Certification, CREA-DC, Florence, Italy

- 5National Research Council, Institute of Marine Sciences, CNR-ISMAR, Milan, Italy

A profound transformation, in recent decades, is promoting shifts in the ways ecological science is produced and shared; as such, ecologists are increasingly encouraged to engage in dialogues with multiple stakeholders and in transdisciplinary research. Among the different forms of public engagement, citizen science (CS) has significant potential to support science-society interactions with mutual benefits. While many studies have focused on the experience and motivations of CS volunteers, scarce literature investigating the perspectives of researchers is available. The main purpose of this paper is to better understand scientists’ attitudes about CS in the context of its potential to support outcomes that extent beyond more traditional ones focused on promoting science knowledge and interest. We surveyed the scientific community belonging to the International Long-Term Ecological Research (ILTER) network because ILTER is of interest to multiple stakeholders and occurs over long time scales. Via an online questionnaire, we asked ILTER scientists about their willingness to participate in different types of public engagement, their reasons for participating in CS, the associated barriers, and any impacts of these efforts on them. Our findings show that many ILTER scientists are open to participating in CS for a wide range of reasons; the dominant ones involve deeper public engagement and collaboration. The barriers of greatest concern of these respondents were the lack of institutional support to start and run a CS project and the difficulty of establishing long-term stable relationships with the public. They reported impacts of CS activities on how they pursue their work and acknowledged the benefit of opportunities to learn from the public. The emerging picture from this research is of a community willing and actively involved in many CS projects for both traditional reasons, such as data gathering and public education, and expanded reasons that activate a real two-way cooperation with the public. In the ILTER community, CS may thus become an opportunity to promote and develop partnerships with citizens, helping to advance the science-society interface and to rediscover and enhance the human and social dimension of the scientific work.

1 Introduction

In recent decades, science has been undergoing a profound transformation in the ways it is produced and shared (Allen and Giampietro, 2006; Benessia et al., 2016; Wittmayer et al., 2019). This is particularly true for ecological science, geosciences and other environmental sciences, which must consider social and cultural dimensions (Haberl et al., 2006; Groffman et al., 2010; EEA, 2021a; EEA, 2021b), in order to disentangle and address complex local and global challenges (Owen et al., 2012; Davies, 2014; Enquist et al., 2017; Kelly et al., 2019). Such efforts require scientists to engage in dialogues with stakeholders (resource managers, property owners, policy personnel and others) and in transdisciplinary research, adopting a “translational” perspective “to develop research that addresses the sociological, ecological, and political contexts of an environmental problem” (Enquist et al., 2017, p. 541). This also means that scientists need to increase and expand how they engage with public audiences (Groffman et al., 2010; Wittmayer et al., 2019; Rose et al., 2020), as well as share their efforts, success and challenges with each other (Davis et al., 2022).

Public engagement can be defined as any activity by members of the scientific community to engage with people outside their research area (Besley et al., 2018). Many scientists are actively involved in public engagement (Burchell, 2015; Golumbic et al., 2017; Rose et al., 2020; Davis et al., 2022) and feel these activities as an important part of their work (Rose et al., 2020). However, the motivations for scientists’ participation in public engagement are often focused, prevalently or exclusively, on defending science, increasing science knowledge and building excitement about science to improve public consensus on scientific research and science reliability (Dudo and Besley, 2016; Besley et al., 2018; Rose et al., 2020). These are valid goals but they tend to overemphasize knowledge gains over other goals. A possible reason for this may be that scientists feel more responsible for transmitting their understanding rather than taking care of the co-construction of scientific knowledge, and, while they want public support, they may not feel the public’s opinion is relevant in the advancement of the debate on science and technology (Besley and Nisbet, 2013; Llorente et al., 2019; Pasquier et al., 2020).

This prevalent top-down approach has been questioned by some researchers and organizations pushing for meaningful engagements with public audiences (e.g., Center for Public Engagement with Science and Technology at the American Academy of the Advancement of Science) and for broadening of targeted communication outcomes. For example, Besley et al. (2018) offered a broad array of possible communication objectives that extend beyond knowledge gains, and instead seek to build connections between scientists and public audiences: ⅰ) demonstrating the scientific community’s expertise, ⅱ) demonstrating the scientific community’s openness and transparency, ⅲ) demonstrating scientists share community values, ⅳ) hearing what others (e.g., local community members), think about scientific issues, and ⅴ) framing research implications so that they resonate with public values. In Europe, the Science with and for Society (SwafS) Program and the Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI) challenge scientists to both critically reflect on their research approach and consider ways to more fully integrate other stakeholders, entailing a co-construction of knowledge for society (Owen et al., 2012; Rauws, 2015; Rask et al., 2016; L’Astorina and Di Fiore, 2017; L’Astorina and Di Fiore, 2018). Overall, a participatory approach may be essential to deal with complex, transdisciplinary and multi-player problems and to build the foundation for scientific citizenship in democratic societies (Funtowicz and Ravetz, 1993; Irwin, 2001; Irwin, 2015).

One opportunity to support science-society interactions with mutual benefits is citizen science (CS). Among the high number of definitions of CS, we adopted the one from Serrano Sanz et al. (2014), who defined it as “the general public engagement in scientific research activities when citizens actively contribute to science either with their intellectual effort or surrounding knowledge or with their tools and resources.” As such, CS presents the opportunity to promote a collaborative relationship and dialogue between scientists and the public and, indeed, some suggest it is one of the most promising approaches for meaningful science-society exchanges (e.g.; Garbarino and Mason, 2006; Horst et al., 2016; Fritz et al., 2019; Ramya et al., 2019; Gunnell et al., 2021; Vohland et al., 2021).

Various authors have offered different epistemological views of volunteer involvement in CS. The two main directions (Hecker and Taddicken, 2022) still refer to seminal works proposed in the nineties by Irwin (1995) and Bonney (1996). Irwin (1995) proposed the term CS as a support to democratization of expertise, emphasizing the collaborative aspects of citizens and often including people with local and lay or indigenous knowledge who work with scientists to co-create knowledge. Bonney (1996) characterized CS mainly as a tool for professional scientists to receive contribution from volunteering citizens through environmental data collection. These two perspectives coexist in an often-cited classification by Haklay (2013); Haklay (2018), where CS includes different levels of participation. This classification ranges from “crowdsourcing” (citizens are only human sensors and have a passive role) to “distributed intelligence” and “participatory science” (citizens are “participants” in a research activity, collecting data and giving an interpretation of data) to “extreme” CS (a strong collaboration between researchers and citizens in problem definition, data collection and critical analysis). Shirk et al. (2012) offered a similar framework with five models of public participation in scientific research: contractual, contributory, collaborative, co-created and collegial.

These classifications suggest that CS could be a transformative process affecting many aspects of the relationship between ecology and society; this notion served as the starting point for our research on the motivations of scientists to engage in CS projects and activities. While there are many studies focused on the experience and motivations of CS volunteers (see, for example, Mankowski et al., 2011) or on the learning outcome of volunteers in terms of scientific knowledge (Trumbull et al., 2000; Cronje et al., 2011; Crall et al., 2013), only a few studies have investigated the perspectives of researchers engaged in CS projects (Riesch and Potter, 2014; Golumbic et al., 2017).

Here, we seek to better understand scientists’ attitudes about CS in the context of its potential to support a broader array of communication outcomes; that is, to move beyond traditional ones focused on knowledge gains and to more fully engage volunteers in research activities and associated dialogues. We focused on the International Long-Term Ecological Research (ILTER) network1 (Mirtl et al., 2018; Wohner et al., 2021), which offers an ideal context to examine scientists’ attitudes on public engagement and specifically on the benefits, opportunities and challenges of CS. First, research at ILTER sites occurs across long time scales and utilizes large and diverse sources of data to investigate ecological and socio-ecological state and changes. ILTER research ranges from local to continental environmental questions and issues that are relevant for multiple stakeholders, and thus are suitable to support in-depth and expanded engagement activities with local community members and the public at large. Second, since many ILTER sites are embedded in local communities, scientists working there may be in the position to potentially form more stable relationships through CS, and thus support broader communication and deeper engagement between scientists and stakeholders.

We present the findings from a survey that we launched among scientists working at ILTER across the globe, aimed at examining scientists’ willingness to participate in different types of public engagement (including CS), their reasons for participating in CS, the barriers associated with CS, and any impacts of these efforts on them. Overall, our findings can deepen our understanding of CS and its transformative potential for researchers in ecology.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 The ILTER context

ILTER is a global network of networks active in the fields of ecosystem, critical zone, and socio-ecological research (Mirtl et al., 2018; Wohner et al., 2021) across terrestrial, freshwater, transitional, and marine environments. Founded in 1993, it currently (DEIMS-SDR, 2022) consists of 44 active Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER) network members, which include 700 LTER sites (comprising mainly one habitat type with activities concentrated on small scale ecosystem processes and structures) and 80 Long-term Socio-Ecological Research (LTSER) platforms (comprising multiple habitat types, with activities focusing mainly on socio-economic research that can be readily applicable to contemporary environmental challenges; Dick et al., 2018).

The primary goal of ILTER is to investigate changes in ecosystem structure, processes and function in response to a wide range of environmental forcings using long-term (typically decades), place-based research. ILTER adopts a whole-system approach, crucial to understanding the role and interactions of multiple and complex ecosystem variables. Socio-ecological research is also conducted in national LTER networks worldwide, in particular at the LTSER platforms, aiming at collecting and synthesizing both environmental and socio-economic knowledge and to involve a broader stakeholder-community to define research priorities (Haberl et al., 2006; Mauz et al., 2012; Dick et al., 2018).

As reported in a companion paper (Bergami et al., 2023), different CS project and initiatives are on-going at ILTER, however the majority of them are sparse and do not share harmonized procedures and views. Only recently (January 2022), an initiative2 has been developed at the whole network level in eLTER (the European component of ILTER), jointly with the iNaturalist network, to create an umbrella project aiming at strengthening the relationship between citizens and the researchers, promoting long-term biodiversity data registration within LTSER (Long-Term Socio-Ecological Research) platforms.

2.2 Questionnaire development and administration

We collected quantitative data from ILTER scientists via an online questionnaire, available as Supplementary Material S1, which asked respondents about their attitudes and actions with regard to CS. In the questionnaire, we defined “public engagement with science” as “communicating with non-scientists on scientific topics outside of formal educational settings (including CS),” and defined “citizen science” as “collaborating with the public on scientific endeavours.”

To develop and validate the online questionnaire, we first held a workshop at the Second ILTER Open Science Meeting in September 2019 in Leipzig (Germany). Our aim was to gather initial perspectives of ILTER scientists on CS, as the participants discussed and reflected on roles, rights, responsibilities, barriers, and rewards. The 14 participants played different roles at 10 LTER networks, and they had different levels of experience in CS initiatives; they therefore brought a diversity of perspectives on CS. We worked with the participants to create and discuss a preliminary list of reasons why scientists might participate in CS, as well as a list of associated challenges.

Building from the workshop lists and from related literature and inventories (e.g., Riesch et al., 2013; Golumbic et al., 2017; Tredick et al., 2017; Besley et al., 2018; Robertson Evia et al., 2018; Stylinski et al., 2018), we then wrote a first draft of the questionnaire. We piloted this draft with 14 environmental scientists who were not involved with ILTER (10 were non-native English speakers) to ensure respondents interpreted and answered questions as intended and that language was clear. We used their feedback to revise and write the final draft of the questionnaire.

We administered the online questionnaire in early 2020 by sending an initial recruitment email and two reminder emails to all ILTER site managers on the ILTER secretariat contact list (850 recipients). The emails specified the purpose of the study and how the data would be used, and asked site managers to complete and to forward it to other scientists at their site. The questionnaire was a mix of multiple-choice and open-ended questions in which the scientists had to select the option that best suited their opinion or to write in full their answers. In some items, scientists were asked to indicate their degree of agreement, importance or willingness based on a 5-point Likert-like scale. Respondents were free to choose whether or not to answer any particular question. The average survey duration was approximately 20 min. The questionnaire was available online from late February to mid-September 2020.

2.3 Respondents and demographics

One hundred and sixty-five respondents completed the first part of the questionnaire, which is relevant to this study (i, ii, and iv in the questionnaire provided in the Supplementary Material S1). We assumed that site managers either filled the questionnaire or passed it on to a scientist at their site. Thus, our pool of possible respondents was 850, and our response rate is 17%., comparable to that of other online surveys of expert communities (e.g., Scott et al., 2011; Dudo and Besley, 2016).

The questionnaire had demographic items including information about respondents’ role at the ILTER sites and platforms, their career level, age, gender, the scientific field of interest, the country where they work and the DEIMS.ID3 of the ILTER site or platforms they manage.

The survey results are accessible on Zenodo (Bergami et al., 2022).

2.4 Data analysis

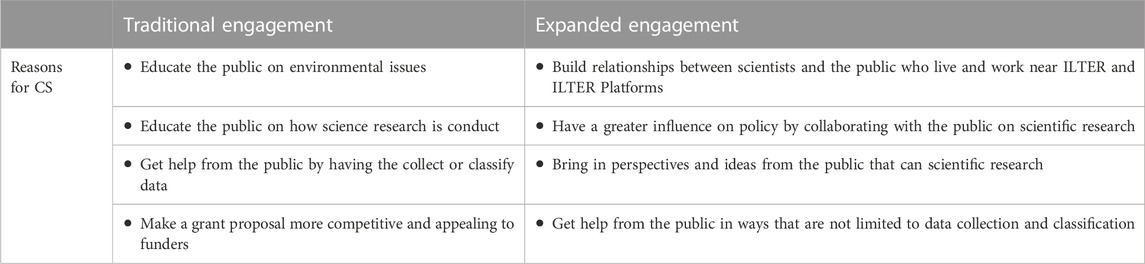

We developed our analysis by reporting the percentage of respondents in the rankings of the different questions for what regards: i) willingness to participate in different types of public engagement, ii) reasons for participation in CS, iii) possible barriers to CS, and iv) ways the CS initiative impacted scientists. As noted, we sought to examine CS activities in the context of broader engagement goals. Thus, building from the literature described earlier, we examined reasons for participating in CS activities in the context of traditional versus an expanded engagement perspective (Table 1). For this study, we define traditional as focused on knowledge gains and promotion of science interest, and expanded as linked to building relationships and promoting two-way dialogues.

TABLE 1. List of the reasons for participating in CS activities, considering traditional and expanded engagement.

The statistical analysis mainly focused on mean comparisons (paired two-samples Wilcoxon test) to assess potential significant differences in the responses of the various demographic groups. Geographical distribution of CS activities was represented by bio-geographical region. The statistical software R (version 4.1.2) was used for all the analysis (R Core Team, 2021). The analysis is available as open code on GitHub (Oggioni and Bergami, 2022).

3 Results

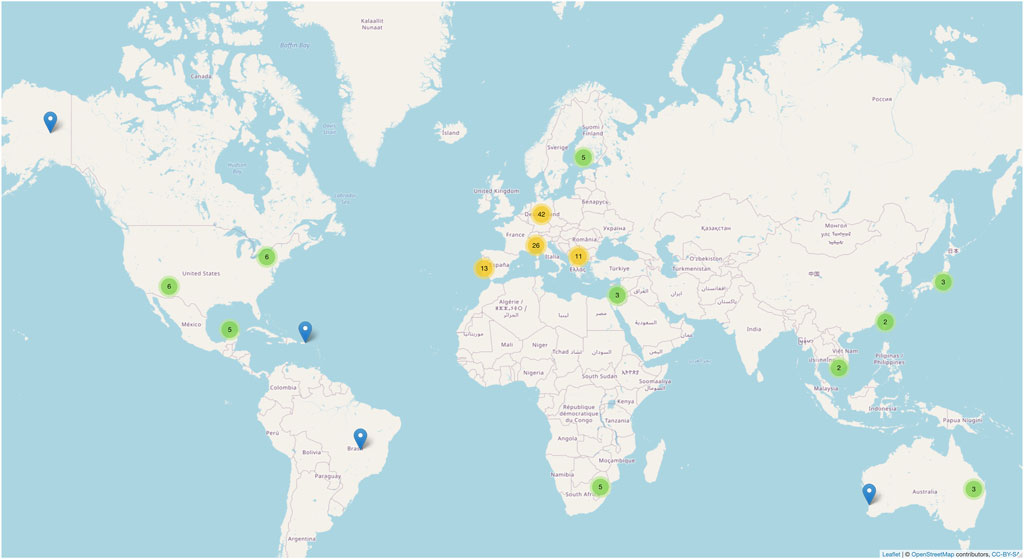

Respondents were a mix of science professionals based on an LTER site or LTSER platform with 38% working as site managers and 25% working as collaborators, National network Coordinators, or data managers; 16% listed “other”, which included co-site managers and PhD students. In terms of their career level, a majority of respondents were senior (44%) or mid-career (22%); the remainder were junior career (10%), graduate students (1%) and retired scientists (2%). Most respondents were 50–59 years in age (25%) with the remainder over 60 (20%), 40–49 (13%) and under 40 (5%). They primarily worked in LTER Europe (58%) and US LTER (10%), with low percentages from East-Asia-Pacific (EAP, 7%), Central and South America (4%) and Africa (3%) (Figure 1). Most (59% of respondents) listed biology and environmental science as their main science field.

FIGURE 1. Map of the distribution of respondents by biogeographic regions [© OpenStreetMap contributors (openstreetmap.org). Map data July 14, 2023].

The analysis of the differences in the responses between the various demographic groups, described above, did not give statistically significant results. Therefore, we will present the results as overall percentages, considering the answers coming from a unique pool.

3.1 Willingness for public engagement

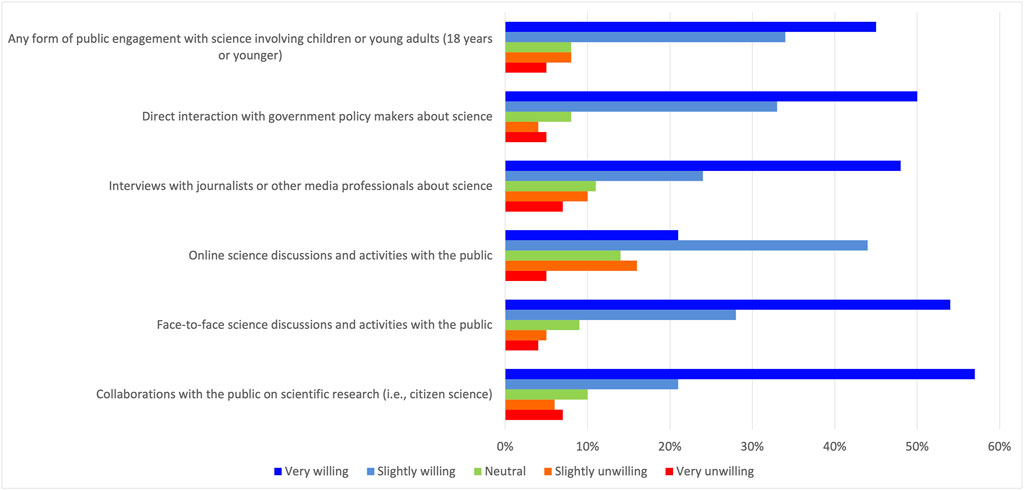

From 65 to 83% of respondents were “slightly” or “very” willing to participate in some form of public engagement (Figure 2). The greatest willingness was for CS and face-to-face discussions/activities (54–57% were “very willing”). The lowest willingness was for online science discussions/activities (only 21% were “very willing”).

FIGURE 2. Percentage of respondents who are willing/unwilling to participate in different types of public engagement.

3.2 Reasons for participating in citizen science

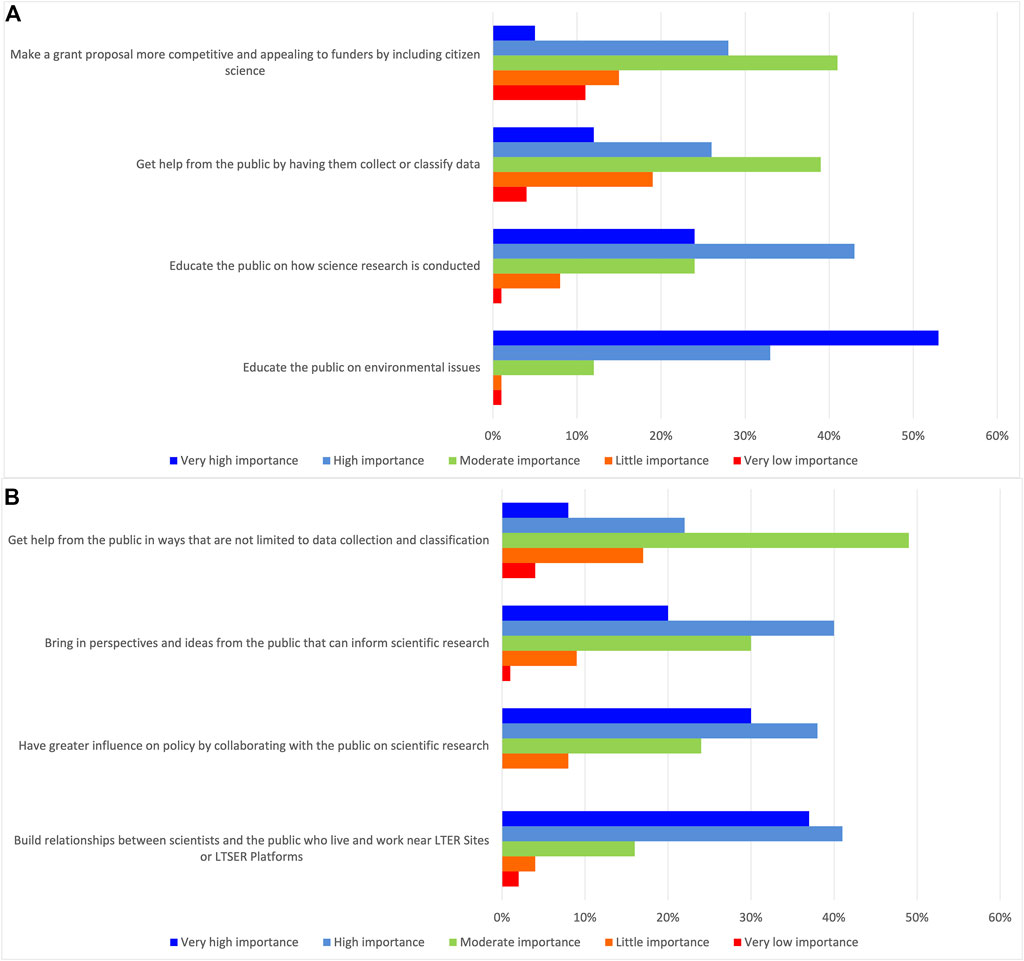

The ratings of the responses to the two types of engagement (traditional vs. expanded, see Table 1) show a statistically significant difference (p = 0.037, see Figure 3). The expanded engagement reason, “Build relationship between scientists and the public live and work near LTER Sites and LTSER Platforms,” was rated as one of the most important (78%, “high” or “very high” importance). Other important reasons were a mix of traditional and expanded engagement reasons: “have a greater influence on policy by collaborate with the public on scientific research (68%), “educate the public on environmental issues” (67%), “education the public on how science research is conducted (67%),” and “bring in perspectives and ideas from the public that can inform scientific research” (61%). Likewise, the lowest ratings were for mix of traditional and expanded engagement reasons: “get help from the public by having them collect or classify information,” “make a grant proposal more competitive and appealing to funds by including citizen science,” and “get help from the public in ways that are not limited to data collection and classification” (39%, 33% and 28% rated these as “high” or “very high” importance, respectively).

FIGURE 3. Percentage of respondents who rated the importance of different reasons for participation in CS. (A) traditional reasons; (B) expanded reasons.

3.3 Citizen science barriers

When provided with a list of possible barriers for CS (Figure 4), only a small percentage of respondents strongly agreed with any on the list (2–16%). The barriers of greatest concern were the lack of support to start and run a CS project and the difficulty of establishing long-term stable relationships with the public needed to conduct the work (59% and 54% agreed or strongly agreed, respectively). Some respondents also pointed to other barriers: validating data collected or classified by the public, not getting credit or acknowledgement for contributing to CS, the public’s lack of knowledge or skill necessary for the research, and training the public on this knowledge or skills (42%, 41%, 35%, and 33% agreed or strongly agreed, respectively). By contrast, only a few respondents thought formally acknowledging volunteers’ contributions or a lack of public interest were barriers to CS efforts (17% and 7% agreed or strongly agreed, respectively).

3.4 Citizen science impacts on scientists

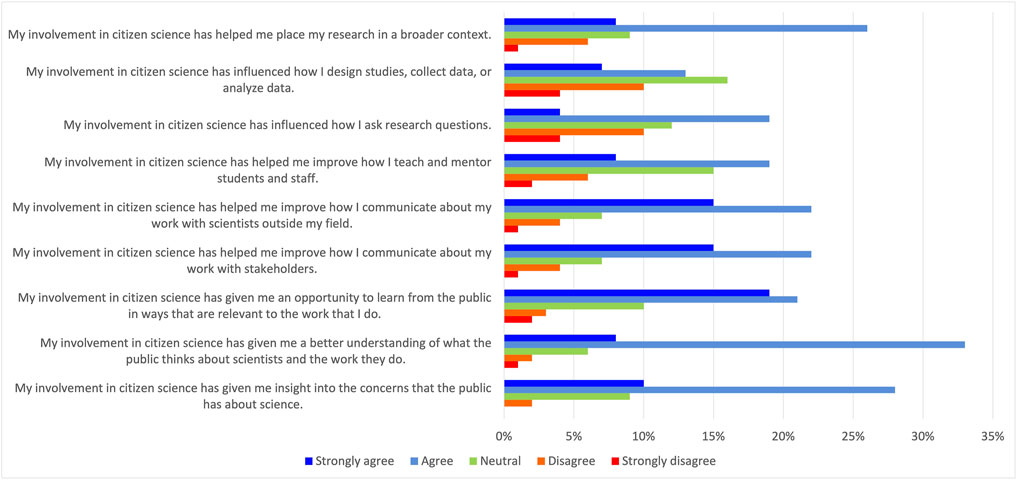

Half of respondents indicated that they have participated in CS initiatives with 76% of these respondents involved in more than one (Bergami et al., 2023). Many of those involved in these initiatives agreed or strongly agreed that these initiatives had some impact on them (Figure 5). The two most common impacts were “better understanding of what the public thinks about scientists and the work they do” and “insight into concerns that the public has about science” (41% and 38% agree or strongly agree and only 3% and 2% disagree or strongly disagree, respectively). Also common were “improve how I communicate about my work with stakeholders”, “an opportunity to learn from the public in ways that are relevant to the work that I do,” and “helped me place my research in a broader context” (37%, 34%, and 34% agree or strongly agree and only 5%, 5% and 7% disagree or strongly disagree). Impacts that were not as common were “how I communicate about my work with scientists outside my field,” “how I ask research questions,” and “how I design studies, collect data or analyze data” (26%, 23% and 20% agree or strongly agree with 8%, 14% and 14% disagree or strongly disagree, respectively).

4 Discussion

Recent years have seen a rise in calls for scientists to engage with stakeholders in science efforts and to understand possible shifts within academic culture regarding public engagement (Groffman et al., 2010; Owen et al., 2012; Davies, 2014; Benessia et al., 2016; Wittmayer et al., 2019). This requires addressing and understanding scientists’ involvement in, attitudes toward, and abilities to pursue public engagement, in particular CS. The benefits of CS are generally described in terms of bringing people closer to science and of promoting a collaborative relationship and dialogue between scientists and the public. The acknowledgment of the transformative process affecting many aspects of the relationship between ecology and society (Haberl et al., 2006; Groffman et al., 2010; EEA, 2021a; EEA, 2021b) highlights the potential role that CS may play in these efforts. CS, indeed, may become an opportunity for scientists, as well as citizens, to rethink the way they conceive, share and formulate questions on scientific issues, renegotiating their role, rights and responsibilities (Allen and Giampietro, 2006; Enquist et al., 2017; Wittmayer et al., 2019; L’Astorina et al., 2021; Hecker and Taddicken, 2022).

Within this context, the main aim of this paper was to survey the attitudes of scientists involved in the globally widespread ILTER network in terms of engaging in CS. Before discussing the results, we should highlight two critical aspects. The first is the biogeographical and socio-ecological representativeness of the ILTER site network, which shows a strong geographical bias of site/platform locations towards regions with higher economic density (Wohner et al., 2021). The regions of lower economic density, which have significant relevance in both a regional and a global context concerning the sensitivity of ecosystems and socio-ecological relationships, are underrepresented. Second, the prevalent typology of respondents to our survey was mainly European, senior/mid-career and in the age over 50, with an underrepresentation of other countries, roles and ages. This likely explains the lack of statistically significant differences in the responses between the various demographic groups; that is, the respondents’ role at the ILTER sites and platforms, their career level, and age had almost no meaningful relationship when compared to their prioritization of any of the survey’s question categories.

Our findings indicate that most scientists were willing to participate in various forms of public engagement and particularly CS. Indeed, approximately half of respondents have participated in CS initiatives with many involved in more than one (Bergami et al., submitted). This aligns with other studies that demonstrate high willingness to support public engagement (Martın-Sempere et al., 2008; Besley et al., 2013; Besley, 2015; Pew Research Center, 2015; Besley et al., 2018) and specifically CS (Riesch and Potter, 2014; Golumbic et al., 2017). ILTER scientists do report a somewhat lower willingness to engage in online science public discussions and activities (only 23% of respondents rated this as “very willing”). This also matches similar findings, which suggest scientists harbor concerns about time and efficacy for this type of public engagement (Besley, 2015).

A number of studies exploring the reasons for public engagement of scientists (Riesch et al., 2013; Riesch and Potter, 2014; Burchell, 2015; Golumbic et al., 2017; Besley et al., 2018; Robertson Evia et al., 2018; Bína et al., 2021) reveal scientists are mainly committed to transmitting their knowledge and increasing public understanding or excitement without consideration of broader outcomes or the public’s contribution for the advancement of science and technology (Gastil, 2017; Kappel and Holmen, 2019; Pasquier et al., 2020). However, this trend seems to hold only partially for ILTER scientists who offer a wide range of reasons for participating in CS. The three dominant ones involve deeper public engagement and collaboration: i) building relationships with the public that live and work near the LTER site and platforms, ii) attain a greater influence on policy through this collaboration, and iii) bring public’s perspectives and ideas into scientific research. These reasons do coexist with more traditional ones (i.e., educating the public on environmental issues and science research practices), pointing to a diversity of drivers for these efforts.

These findings suggest the ILTER community has broad views of how CS volunteers can contribute to science research. For example, most rated “Get help from the public by having them collect or classify data” of very low to moderate importance. However, ILTER scientists’ reasons for participating in CS partly conflicts with how they are actually involving volunteers in their science research (Bergami et al., 2023); that is, the majority of respondents who are or have participated in CS indicated that their volunteers are involved in helping “collect samples or record data.” This discrepancy could be explained by skepticism about the quality of the data gathered by not-experts, which is often considered in the literature as one of the main barriers for scientists in the activation of CS projects (e.g., Riesch et al., 2013; Burgess et al., 2017; Golumbic et al., 2017). However, this does not seem to be the case for ILTER researchers, since many respondents do not indicate this aspect as a key barrier. Rather, the barriers of greatest concern were the lack of support to start and run a citizen science project and the difficulty of establishing long-term stable relationships necessary to conduct the work. These highlight an institutional problem: the scarce support, and perhaps interest for CS initiatives. There is a growing recognition that research and academic institutions need to expand the extent and approach to public engagement, but in practice they mainly focused funds and incentives around traditional scientific research (Riesch et al., 2013; Entradas and Bauer, 2017; Rose et al., 2020). The lack of support makes it difficult to build and maintain stable long-term relationships, an action that should be fostered at the institutional level because it can overcome the project level of a limited time span, and can help embed CS within many activities performed at site/platform or network level. It is noteworthy that the minority of respondents who reported they were very unwilling to participate in public engagement gave the highest ratings to the statements, “the public does not have the necessary knowledge or skills to contribute to scientific research” and “it is too difficult or time-consuming to teach the public the necessary knowledge or skills to contribute to scientific research.” This suggests that those who are reluctant to participate in public engagement harbor misconceptions about the public’s ability to make robust and valuable contributions to science.

Whatever the reasons and the barriers, the ILTER scientists who participated in CS activities indicated impacts on how they pursue their work. They gained a better understanding of what the public thinks about science, including their concerns, and gained communication skills. Impressively, almost two-thirds acknowledged the opportunity to learn from the public. Half or almost half of respondents agreed that there were impacts on their research: how to ask questions, design studies, and collect and analyze data. These responses provide evidence of the awareness that CS represents an opportunity for scientists, as well as volunteers, to reframe their role in society. For some, CS is challenging science by demonstrating that traditional research approaches are not the only way to build knowledge; rather, formally trained researchers should also collaborate with those who are experts through experience and local knowledge to find solutions in an uncertain and complex world (Funtowicz and Ravetz, 1993; Stilgoe, 2009; ESF Science Policy Briefing 50, 2013; Sabu, 2020; Pateman et al., 2021; Fraisl et al., 2022). Warren et al. (1995) describes this knowledge as “unique to a given culture or society” and that may reveal critical for the solution of environmental issues.

In conclusion, the picture that emerges from the survey is of a community that is willing and actively involved in CS (also see Bergami et al., 2023) for traditional reasons, such as data gathering and public education, and expanded reasons that activate a two-way cooperation with the public. This is in line with the growing trend towards an ever-increasing integration between science and the society, particularly within the context of environmental issues (e.g., Groffman et al., 2010; Benessia et al., 2016; EEA, 2021a). This seems particularly relevant for long-term research endeavors, like the ILTER community, considering their global diffusion, broad temporal and spatial scales, relevancy and the need to establish strong and durable interactions with multiple stakeholders and local communities.

The creation and the maintenance of these relationships and collaborations, through CS, can provide critical data and other support to LTER by expanding the temporal and spatial coverage of data (Zettler et al., 2017; La Sorte and Somveille, 2020). It can also promote and develop partnerships between citizens and ILTER, helping to advance the science-society interface (Nowotny, 2003; Cvitanovic et al., 2016; Muelbert et al., 2019). The ILTER networks might facilitate collective social learning and experiences, inspired by the so-called communities of practice (Wenger et al., 2002), in which knowledge, community, learning and identity are co-created. In the ILTER community, CS may thus become an opportunity also for scientists to enhance the human and social dimension of the scientific work.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7148596, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7472885

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the participants was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

All the Authors contributed to the design of the research and were organizers of the preparatory workshop during the ILTER 2nd Open Science Meeting (Leipzig, Germany; 3 September 2019); CD, CB, AL, and AC drafted the survey, which was discussed with and approved by all the Authors; AO and CB elaborated the survey results. AL, CD, and AP drafted the manuscript. All the Authors contributed to the discussion of the results and to the critical revisions of the text.

Funding

This work was performed within the “Citizens for Long-Term Ecological Research” initiative, supported by the ILTER Initiative Grants.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the ILTER Coordination Committee and Secretariat for contributing sharing widely the survey within the whole network and all the respondents of the ILTER community for their availability to participate.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fenvs.2023.1130022/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

2https://elter-ri.eu/news/joint-online-program-citizen-science-across-ltser-platforms-catalyst-network-collaboration

3DEIMS.iD is the identifier of ILTER sites/platforms on Dynamic Ecological Information Management System—Site and dataset registry (DEIMS-SDR), which is the ILTER information management system that allows to discover long-term ecosystem research sites around the globe. https://deims.org/docs/deimsid.html

References

Allen, T. F. H., and Giampietro, M. (2006). Narratives and transdisciplines for a post-industrial world. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 23, 595–615.

Benessia, A., Funtowicz, S., Giampietro, M., Guimarães Pereira, Â., Ravetz, J., Saltelli, A., et al. (2016). “The rightful place of science: Science on the verge,” in Tempe, AZ: Consortium for science, policy and outcomes.

Bergami, C., Campanaro, A., Davis, C., L’Astorina, A., Pugnetti, A., and Oggioni, A. (2023). Environmental citizen science practices in the ILTER community: Remarks from a case study at global scale. Front. Environ. Sci. 11, 1130020. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2023.1130020

Bergami, C., Merritt Davis, C., Campanaro, A., Pugnetti, A., L'Astorina, A., and Oggioni, A. (2022). “Survey dataset - environmental citizen science: Practices and scientists' attitudes at ILTER [data set],” in Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.7148596

Besley, J. C., Dudo, A., Yuan, S., and Lawrence, F. (2018). Understanding scientists’ willingness to engage. Sci. Commun. 40 (5), 559–590. doi:10.1177/1075547018786561

Besley, J. C., and Nisbet, M. (2013). How scientists view the public, the media and the political process. Public Underst. Sci. 22 (6), 644–659. doi:10.1177/0963662511418743

Besley, J. C., Oh, S. H., and Nisbet, M. (2013). Predicting scientists’ participation in public life. Public Underst. Sci. 22, 971–987. doi:10.1177/0963662512459315

Besley, J. C. (2015). What do scientists think about the public and does it matter to their online engagement? Sci. Public Policy 42 (2), 201–214. doi:10.1093/scipol/scu042

Bína, P., Brounéus, F., Kasperowski, D., Hagen, N., Bergman, M., Bohlin, G., et al. (2021). Awareness, views and experiences of citizen science among Swedish researchers—Two surveys. JCOM 20 (06), A10. doi:10.22323/2.20060210

Burchell, K. (2015). Factors affecting public engagement by researchers: Literature review. London: Policy Studies Institute.

Burgess, H. K., DeBey, L. B., Froehlich, H. E., Schmidt, N., Theobald, E. J., Ettinger, A. H., et al. (2017). The science of citizen science: Exploring barriers to use as a primary research tool. Biol. Conserv. 208, 113–120. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2016.05.014

Crall, A. W., Jordan, R., Holfelder, K., Newman, G. J., Graham, J., and Waller, D. M. (2013). The impacts of an invasive species citizen science training program on participant attitudes, behavior, and science literacy. Public Underst. Sci. 22 (6), 745–764. doi:10.1177/0963662511434894

Cronje, R., Rohlinger, S., Crall, A., and Newman, G. (2011). Does participation in citizen science improve scientific literacy? A study to compare assessment methods. Appl. Environ. Educ. Commun. 10 (3), 135–145. doi:10.1080/1533015X.2011.603611

Cvitanovic, C., McDonald, J., and Hobday, A. J. (2016). From science to action: Principles for undertaking environmental research that enables knowledge exchange and evidence-based decision-making. J. Environ. Manag. 183, 864–874. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.09.038

Davies, S. R. (2014). Knowing and loving: Public engagement beyond discourse. Technol. Stud. 27 (3), 90–110. doi:10.23987/sts.55316

Davis, C., Weber, C., and Nadkarni, N. (2022). Prevalence of discourse on public engagement with science in ecology literature. Front. Ecol. Environ. 20, 524–530. doi:10.1002/fee.2535

Dick, J., Orenstein, D. E., Holzer, J. M., Wohner, C., Achard, A. L., Andrews, C., et al. (2018). What is socio-ecological research delivering? A literature survey across 25 international LTSER platforms. Sci. Total Environ. 622-623, 1225–1240. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.11.324

Dudo, A., and Besley, J. C. (2016). Scientists’ prioritization of communication objectives for public engagement. PLoS ONE 11 (2), e0148867. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0148867

EEA (2021a). Building the foundations for fundamental change. Copenaghen: European Environment Agency.

EEA (2021b). Living in a state of multiple crises: Health, nature, climate, economy, or simply systemic unsustainability? Copenaghen: — European Environment Agency.

Enquist, C. A. F., Jackson, S. T., Garfin, G. M., Davis, F. W., Gerber, L. R., Littell, J. A., et al. (2017). Foundations of translational ecology. Front. Ecol. Environ. 15 (10), 541–550. doi:10.1002/fee.1733

Entradas, M., and Bauer, M. M. (2017). Mobilisation for public engagement: Benchmarking the practices of research institutes. Public Underst. Sci. 26 (7), 771–788. doi:10.1177/0963662516633834

ESF Science Policy Briefing 50 (2013). Science in society: Caring for our futures in turbulent times. Available at: http://archives.esf.org/fileadmin/Public_documents/Publications/spb50_ScienceInSociety.pdf.

Fraisl, D., Hager, G., Bedessem, B., Gold, M., Hsing, P. Y., Danielsen, F., et al. (2022). Citizen science in environmental and ecological sciences. Nat. Rev. Methods Prim. 2, 64. doi:10.1038/s43586-022-00144-4

Fritz, S., See, L., Carlson, T., Haklay, M. M., Oliver, J. L., Fraisl, D., et al. (2019). Citizen science and the United Nations sustainable development goals. Nat. Sustain. 2 (10), 922–930. doi:10.1038/s41893-019-0390-3

Funtowicz, S. O., and Ravetz, J. R. (1993). Science for the post-normal age. Futures 25 (7), 739–755. doi:10.1016/0016-3287(93)90022-l

Garbarino, J., and Mason, C. E. (2006). The power of engaging citizen scientists for scientific progress. J. Microbiol. Biol. Educ. 17 (1), 7–12. doi:10.1128/jmbe.v17i1.1052

Gastil, J. (2017). “Designing public deliberation at the intersection of science and public policy,” in The oxford handbook of the science of science communication. Editors K. H. Jamieson, D. M. Kahan, and D. A. Scheufele (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 233–242. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190497620.013.26

Golumbic, Y. N., Orr, D., Baram-Tsabari, A., and Fishbain, B. (2017). Between vision and reality: A study of scientists’ views on citizen science. Citiz. Sci. Theory Pract. 2 (1), 6–13. doi:10.5334/cstp.53

Groffman, P. M., Stylinski, C., Nisbet, M. C., Duarte, C. M., Jordan, R., Burgin, A., et al. (2010). Restarting the conversation: Challenges at the interface between ecology and society. Front. Ecol. Environ. 8 (6), 284–291. doi:10.1890/090160

Gunnell, J. L., Golumbic, Y. N., Hayes, T., and Cooper, M. (2021). Co-Created citizen science: Challenging cultures and practice in scientific research. JCOM 20 (05), Y01. doi:10.22323/2.20050401

Haberl, H., Winiwarter, V., Andersson, K., Ayres, R. U., Boone, C., Castillo, A., et al. (2006). From LTER to LTSER: Conceptualizing the socio-economic dimension of long-term socio-ecological research. Ecol. Soc. 11 (2), 13. doi:10.5751/es-01786-110213

Haklay, M. (2013). “Citizen science and volunteered geographic information: Overview and typology of participation,” in Crowdsourcing geographic knowledge: Volunteered geographic information (VGI) in theory and practice. Editors D. Sui, S. Elwood, and M. Goodchild (Dordrecht: Springer), 105–122.

Haklay, M. (2018). “Participatory citizen science,” in Citizen science: Innovation in open science, society and policy. Editors M. Haklay, S. Hecker, A. Bowser, Z. Makuch, J. Vogel, and A. Bonn (London: UCL Press, University College London), 52–62. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv550cf2.11.

Hecker, S., and Taddicken, M. (2022). Deconstructing citizen science: A framework on communication and interaction using the concept of roles. JCOM 21 (01), A07. doi:10.22323/2.21010207

Horst, M., Davies, S. R., and Irwin, A. (2016). Reframing science communication. Handb. Sci. Technol. Stud. 4, 881–907.

Irwin, A. (2015). “Citizen science and scientific citizenship: Same words, different meanings?,” in Science communication today: Current strategies and means of action. Editors B. Schiele, J. Le Marec, and P. N. Baranger (France: Presses Universitaires de Nancy), 29–38.

Irwin, A. (1995). Citizen science: A study of people, expertise and sustainable development. London, U.K.: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203202395

Irwin, A. (2001). Constructing the scientific citizen: Science and democracy in the biosciences. Public understand. Sci. 10, 1–18. doi:10.1088/0963-6625/10/1/301

Kappel, K., and Holmen, S. J. (2019). Why science communication, and does it work? A taxonomy of science communication aims and a survey of the empirical evidence. Front. Commun. 4, 55. doi:10.3389/fcomm.2019.00055

Kelly, R., Fleming, A., and Pecl, G. T. (2019). Citizen science and social licence: Improving perceptions and connecting marine user groups. Ocean Coast. Manag. 178, 104855. doi:10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2019.104855

La Sorte, F. A., and Somveille, M. (2020). Survey completeness of a global citizen-science database of bird occurrence. Ecography 43, 34–43. doi:10.1111/ecog.04632

L’Astorina, A., Bergami, C., De Lazzari, A., and Falchetti, E. (2021). “Special Issue “Scientists moving between narratives towards an ecological vision”,” in Visions for sustainability, 16.

L’Astorina, A., and Di Fiore, M. (2017). A new bet for scientists? Implementing the responsible research and innovation (RRI) approach in the practices of research institutions. Beyond Anthr. 5 (2), 157. doi:10.7358/rela-2017-002-last

L’Astorina, A., and Di Fiore, M. (2018). Scienziati in affanno? Ricerca e innovazione responsabili (RRI) in teoria e nelle pratiche. Roma: CNR Edizioni. doi:10.26324/2018RRICNRBOOK

Llorente, C., Revuelta, G., Carrió, M., and Porta, M. (2019). Scientists’ opinions and attitudes towards citizens’ understanding of science and their role in public engagement activities. PLoS ONE 14 (11), e0224262. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0224262

Mankowski, T. A., Slater, S. J., and Slater, T. F. (2011). An interpretive study of meanings citizen scientists make when participating in galaxy zoo. Contemp. Issues Educ. Res. (CIER) 4 (4), 25–42. doi:10.19030/cier.v4i4.4165

Martın-Sempere, M. J., Garzón-Garcıa, B., and Rey-Rocha, J. (2008). Scientists’ motivation to communicate science and technology to the public: Surveying participants at the madrid science fair. Public Underst. Sci. 17 (3), 349–367. doi:10.1177/0963662506067660

Mauz, I., Peltola, T., Granjou, C., van Bommel, S., and Buijs, A. (2012). How scientific visions matter: Insights from three long-term socio-ecological research (LTSER) platforms under construction in Europe. Environ. Sci. Policy 19, 90–99. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2012.02.005

Mirtl, M., Borer, E., Djukic, I., Forsius, M., Haubold, H., Hugo, W., et al. (2018). Genesis, goals and achievements of long-term ecological research at the global scale: A critical review of ilter and future directions. Sci. Total Environ. 626, 1439–1462. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.12.001

Muelbert, J. H., Nidzieko, N. J., Acosta, A. T. R., Beaulieu, S. E., Bernardino, A. F., Boikova, E., et al. (2019). Ilter – the international long-term ecological research network as a platform for global coastal and ocean observation. Front. Mar. Sci. 6, 527. doi:10.3389/fmars.2019.00527

Nowotny, H. (2003). Democratising expertise and socially robust knowledge. Sci. Public Policy 30 (3), 151–156. doi:10.3152/147154303781780461

Oggioni, A., and Bergami, C. (2022). “oggioniale/CSSurveyAnalysis: 1.0 (1.0),” in Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.7472885

Owen, R., Macnaghten, P., and Stilgoe, J. (2012). Responsible research and innovation: From science in society to science for society, with society. Sci. Public Policy 39 (6), 751–760. doi:10.1093/scipol/scs093

Pasquier, U., Few, R., Goulden, M. C., Hooton, S., He, Y., and Hiscock, K. M. (2020). We can’t do it on our own!” - integrating stakeholder and scientific knowledge of future flood risk to inform climate change adaptation planning in a coastal region. Environ. Sci. Policy 103, 50–57. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2019.10.016

Pateman, R., Dyke, A., and West, S. (2021). The diversity of participants in environmental citizen science. Citiz. Sci. Theory Pract. 6, 9. doi:10.5334/cstp.369

Pew Research Center (2015). How scientists engage the public. Available at: http://assets.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/14/2015/02/PI_PublicEngagementbyScientists_021515.pdf.

R Core Team (2021). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available at: https://www.R-project.org/.

Ramya, C., Blumenthal, M. S., and Matthews, L. J. (2019). Community citizen science: From promise to action. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. Available at: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2763.html.

Rask, M. T., Mačiukaitė-Žvinienė, S., Tauginienė, L., Dikčius, V., Matschoss, K. J., Aarrevaara, T., et al. (2016). Innovative public engagement: A conceptual model of public engagement in dynamic and responsible governance of research and innovation. Helsinki: University of Helsinki and European Union.

Rauws, G. (2015). “Public engagement as a priorty for research,” in Science, society and engagement, an e-anthology. Editors S. B. Edward Andersson, and H. Davis, 22–24.

Riesch, H., and Potter, C. (2014). Citizen science as seen by scientists: Methodological, epistemological and ethical dimensions. Public Underst. Sci. 23, 107–120. doi:10.1177/0963662513497324

Riesch, H., Potter, C., and Davies, L. (2013). Combining citizen science and public engagement: The open air laboratories programme. JCOM 12 (03), A03. doi:10.22323/2.12030203

Robertson Evia, J., Peterman, K., Cloyd, E., and Besley, J. (2018). Validating a scale that measures scientists’ self-efficacy for public engagement with science. Int. J. Sci. Educ. Part B 8 (1), 40–52. doi:10.1080/21548455.2017.1377852

Rose, K. M., Markowitz, E. M., and Brossard, D. (2020). Scientists’ incentives and attitudes toward public communication. PNAS 117 (3), 1274–1276. doi:10.1073/pnas.1916740117

Sabu, J. H. (2020). What motivates researchers to participate in citizen science projects? A Q-methodological study to identify researchers’ latent perspectives. Master thesis (Delft: Delft University of Technology), 81.

Scott, A., Jeon, S-H., Joyce, C. M., Humphreys, J. S., Kalb, G., Witt, J., et al. (2011). A randomised trial and economic evaluation of the effect of response mode on response rate, response bias, and item non-response in a survey of doctors. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 11 (1), 126. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-11-126

Serrano Sanz, F., Holocher-Ertl, T., Kieslinger, B., Sanz Garcia, F., and Silva, C. G. (2014). White paper on citizen science in Europe socientize consortium. Available at: http://www.zsi.at/object/project/2340/attach/White_Paper-Final-Print.pdf.

Shirk, J. L., Ballard, H. L., Wilderman, C. C., Phillips, T., Wiggins, A., Jordan, R., et al. (2012). Public participation in scientific research: A framework for deliberate design. Ecol. Soc. 17 (2), 29. doi:10.5751/ES-04705-170229

Stilgoe, J. (2009). Citizen scientists: Reconnecting science with civil society. Demos. Available at: http://www.demos.co.uk/files/Citizen_Scientists_-_web.pdf.

Stylinski, C., Storksdieck, M., Canzoneri, N., Klein, E., and Johnson, A. (2018). Impacts of a comprehensive public engagement training and support program on scientists’ outreach attitudes and practices. Int. J. Sci. Educ. Part B 8 (4), 340–354. doi:10.1080/21548455.2018.1506188

Tredick, C. A., Lewison, R. L., Deutschman, D. H., Hunt, T. A., Gordon, K. L., and Von Hendy, P. (2017). A rubric to evaluate citizen-science programs for long-term ecological monitoring. BioScience 67 (9), 834–844. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix090

Trumbull, D., Bonney, R., Bascom, D., and Cabral, A. (2000). Thinking scientifically during participation in a citizen-science project. Sci. Educ. 84, 265–275. doi:10.1002/(sici)1098-237x(200003)84:2<265::aid-sce7>3.0.co;2-5

Vohland, K., Land-Zandstra, A., Ceccaroni, L., Lemmens, R., Perelló, J., Ponti, M., et al. (2021). “The science of citizen science evolves. chapter 1,” in The science of citizen science. Editors K. Vohland, A. Land-Zandstra, L. Ceccaroni, R. Lemmens, J. Perelló, and M. Ponti (Cham: Springer), 1–12. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-58278-4_1

Warren, D. M., Slikkerveer, L. J., and Brokensha, D. (1995). The cultural dimension of development: Indigenous knowledge systems. London, UK: Intermediate Technology Publications.

Wenger, E., Mcdermott, R., and Snyder, W. M. (2002). Cultivating communities of practice. Harvard, MA: HBS Press.

Wittmayer, J. M., Backhaus, J., Avelino, F., Pel, B., Strasser, T., Kunze, I., et al. (2019). Narratives of change: How social innovation initiatives construct societal transformation. Futures 112, 102433. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2019.06.005

Wohner, C., Ohnemus, T., Zachariasc, S., Mollenhauerc, H., Ellis, E. C., Klug, H., et al. (2021). Assessing the biogeographical and socio-ecological representativeness of the ILTER site network. Ecol. Indic. 127, 107785. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2021.107785

Keywords: citizen science (CS), public engagement with science, survey, ecological research, ILTER network, collaborative research, scientists’ attitudes

Citation: L’Astorina A, Davis C, Pugnetti A, Campanaro A, Oggioni A and Bergami C (2023) Scientists’ attitudes about citizen science at Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER) sites. Front. Environ. Sci. 11:1130022. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2023.1130022

Received: 22 December 2022; Accepted: 13 March 2023;

Published: 27 March 2023.

Edited by:

Ahmet Erkan Kideys, Middle East Technical University, TürkiyeReviewed by:

Joan Masó, Ecological and Forestry Applications Research Center (CREAF), SpainJohn A. Cigliano, Cedar Crest College, United States

Copyright © 2023 L’Astorina, Davis, Pugnetti, Campanaro, Oggioni and Bergami. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alessandro Oggioni, b2dnaW9uaS5hQGlyZWEuY25yLml0

†These authors share first authorship

Alba L’Astorina

Alba L’Astorina Cathlyn Davis

Cathlyn Davis Alessandra Pugnetti

Alessandra Pugnetti Alessandro Campanaro

Alessandro Campanaro Alessandro Oggioni

Alessandro Oggioni Caterina Bergami

Caterina Bergami