- 1School of Economics and Management, South China Normal University, Guangzhou, China

- 2Key Lab for Behavioral Economic Science and Technology, South China Normal University, Guangzhou, China

The promotion of pro-environment behaviors is important for achieving national and global environmental protection goals. However, there is a gap between the government’s environmental will and the people’s pro-environmental tendencies. National pride has been identified as a critical pathway to achieving individual behaviors desired by the government. Here, we investigate the role of national pride in promoting individuals’ pro-environmental tendencies (PET). A large-scale survey and two experiments in the Chinese context were conducted to investigate the relationship between national pride and PET and the tools for promoting national pride and PET. The results show that national pride is positively associated with individuals’ PET. Priming with national achievements promotes individuals’ PET by inspiring their national pride. Both political-economic achievements and historical-cultural achievements can inspire Chinese people’s national pride, but political-economic achievements are more effective. Moreover, priming national pride combined with highlighting national environmental norm information could more effectively increase PET. Our findings illuminate the relationship between individuals’ national pride and PET, suggesting a potential means for translating national environmental will into individuals’ pro-environmental actions.

1 Introduction

Environmental problems, such as climate change, pollution, and the overexploitation of natural resources, are currently among the greatest threats to humankind, occupying a prominent position on most countries’ policy agendas. For example, at the international level, 175 countries signed the Paris Agreement in 2016 with the aim of collectively addressing climate change. At the national level, for example, in 2020, China pledged to achieve peak carbon emissions by 2030 and strive to attain carbon neutrality by 2060. However, at the individual level, large sections of the public remain unaware of environmental threats or lack the motivation to act (Wong, 2010; Lewandowsky et al., 2013; Schultz et al., 2014; Han et al., 2021). The crucial question, then, is how national will to protect the environment can translate into individuals’ pro-environmental actions.

National pride has been identified as a critical pathway to achieving individual behaviors desired by the government. As an emotional attachment to one’s own country, national pride has been shown to influence individuals’ attitudes and actions and is employed as moral suasion across a wide range of contexts, such as tax compliance (Gangl et al., 2016; Macintyre et al., 2021), pursuing a protectionist regime (Mayda & Rodrik, 2005), supporting sporting events (Kim et al., 2013), and bearing children for the national good (Risse, 2010). However, no experiments were conducted showing the positive impact of national pride on individuals’ pro-environmental actions. And few empirical studies investigate the effects of potential promotional tools of national pride like national achievements (Gangl et al., 2016). Insights into the effects of promotional national pride tools would not only enhance theoretical understanding of national pride and its effects but might also allow public institutions to choose the most effective communication instruments for promoting citizens’ pro-environmental tendencies (PET), the willingness to engage in pro-environmental actions.

This present paper, therefore, conducted three studies to investigate the relationship between individuals’ national pride and PET and the effects of promotional tools of national pride in the Chinese context. In Study 1, we used data derived from a national survey conducted in China to reveal the correlation between national pride and PET. Then, an online experiment was conducted to examine whether manipulating individuals’ national pride can affect their PET using the priming method with national achievements in Study 2. Finally, in Study 3, we used another online experiment to investigate the effect of priming national pride on translating national will into individual PET by highlighting national environmental norm information.

1.1 National pride and PET

One useful explanation of national pride and its effects is offered by social identity theory (Tajfel, 1974; Gangl et al., 2016), which suggests that people derive part of their self-concept from knowledge of their membership of a social group combined with the value and emotional significance attached to that membership (Tajfel and Turner, 1982). So, such self-categorization provides citizens with a positive self-concept through such positive emotions as love and pride in national achievements, meaning national pride can be defined as “the positive affect that the public feels towards their country, resulting from their national identity” (Smith and Kim, 2006, p. 127). This national pride as social identity provides important guidance for social behavior (Huddy and Khatib, 2007): individuals tent to behave in a way that benefits the group’s welfare and interests (Brewer and Kramer, 1986; Reese et al., 2015). According to research, people who have a strong sense of belonging to their community are more likely to participate in blood or monetary donations, as well as vote in elections (Skitka, 2005; Huddy and Khatib, 2007). Since good environmental conditions directly improve the group members’ health and wellbeing, individuals’ identification with a higher social unit, such as a nation, strengthens the attitudes, cohesion, empathy, and solidarity within their group and, consequently, their willingness to make economic sacrifices to protect the environment in the interest of the group’s welfare (Brieger 2019).

We argue that individuals with a higher sense of national pride have a stronger identification with their nation and would be more willing to act in pro-environment ways. Aydin et al. (2022) found that patriotism which is the aspect of national pride and positive love of the country was positively associated with pro-environmental beliefs and behaviors of Turkish participants. Hamada et al. (2021) found similar results using data from Chinese university students and workers. Feygina et al. (2010) found that when Americans were told that it was patriotic to act in pro-environmental ways, they participated in pro-environmental behaviors more actively. Therefore, we propose hypothesis H1.

Hypothesis H1:. There is a positive relationship between individuals’ national pride and PET.

1.2 National achievements and national pride

National pride refers to a positive affective bond connected to specific national achievements and symbols, such as economic development, good governance, low corruption levels, or achievements in sports (Ha and Jang, 2015). Gangl et al. (2016) found that priming with national achievements (in such areas as healthcare, infrastructure, the quality of democratic institutions, and the economy) was effective in promoting people’s patriotism and, consequently, increasing cooperation. Macintyre et al. (2021) also found that priming national pride using sporting achievements increased Australians’ levels of tax compliance. Priming has been proven to be a useful nudging tool to affect people’s behaviors (Shariff et al., 2016). Bimonte et al. (2020) used a visual priming technique based on a short video cartoon about the smartphone lifecycle to investigate the impact of priming on environmental attitudes and found that priming made pro-environmental attitudes more salient and affect the WTP for environment-friendly goods. In view of this, we argue that priming with national achievements can be used as a promotional tool of national pride to affect individuals’ PET and propose hypothesis H2.

Hypothesis H2:. Priming with national achievements can arouse people’s national pride and, consequently, promote PET.

According to Müller-Peters (1998), national pride can be divided into two dimensions, in terms of political-economic and historical-cultural pride, the first dimension involves a country’s economic and political performance capabilities or achievements, and the second dimension involves the achievements of culture and history. Few studies have examined the effectiveness of different national achievements as promotional tools of national pride. Cross-country comparisons literature show that in different counties, people’s feelings of pride toward different national achievements are various (Evans and Kelley, 2002; Fabrykant and Magun, 2016). In other words, the effects of different national achievements on promoting national pride are country-dependent, implying that they need to be examined in a country-specific context. The present paper studies this issue in the Chinese context.

In modern China, political, economic, and cultural growth moved in diametrically different paths. Since the founding of the People’s Republic of China, China has made remarkable achievements in the political and economic fields. For example, China’s economy has developed rapidly, becoming the second-largest economy in the world. Macao and Hong Kong have returned to China. China has lifted nearly 800 million people out of poverty, accounting for nearly 75 percent of global poverty reduction over the same period (DRC and WBG, 2022). The Belt and Road Initiative has enhanced China’s international influence.

In terms of history and culture, China is one of the four ancient civilizations, with a long history and excellent culture. However, Chinese nationality lacks cultural confidence due to various historical reasons (Zhou, 2012). Since the Opium War, foreign invasions and internal disorder brought about not only the threat of national subjugation but also a great impact on Chinese culture. Western culture marched into China directly and rapidly, which broke China’s cultural autonomy and marginalized traditional Chinese culture gradually. China had been copying many things from western countries, either passively or actively, for more than one hundred years, which resulted in the loss of Chinese cultural confidence. The situation has changed greatly with the prosperity of China since the 21st century, and the Chinese people’s cultural confidence is recovering (Zhou, 2012). The prominence of political and economic achievements and the battered cultural confidence may lead to Chinese people’s feelings of pride being more sensitive to political-economic achievements than to historical-cultural achievements. Based on the above analysis, hypothesis H3 is proposed.

hypothesis H3:. In the Chinese context, political-economic achievements are more effective in priming national pride than historical-cultural achievements.

1.3 National pride, social norm, and PET

National pride is closely tied to identification with one’s own country (Smith & Kim, 2006). As social identity theory suggests, the sense of belonging to a social group serves an important purpose in that it allows people to embed the norms of the social group, and a strong association between a person and the norm referent group is key to the effectiveness of social norms on behavior (Liu et al., 2019). Milfont et al. (2020) pointed out that pro-environmental action was a function of salient environmental in-group norms coupled with high levels of in-group identification. And they found that believing that the nation had a superordinate environmental identity was positively associated with both individual and collective pro-environmental actions. Fielding and Hornsey (2016) found that the likelihood of group members making pro-environmental decisions increases if their group norms are pro-environmental. Therefore, people with a stronger sense of pride in their nation would be more willing to act in accordance with the guidance of national environmental norms.

Existing literature has found that highlighting social norm information is another useful nudging tool that can promote pro-environmental actions (Byerly et al., 2018). Bonini et al. (2018) suggested that it is necessary to investigate whether combining interventions could further aid the promotion of pro-environmental actions. So, by combining priming national pride and highlighting norm information, we try to examine whether individuals with high national pride are more willing to engage in pro-environmental actions when they are aware of their country’s environmental norms and propose hypothesis H4.

Hypothesis H4:. Priming national pride and highlighting national environmental norm information would be more effective in promoting PET.

2 Study 1

2.1 Participants

The Chinese Social Survey (CSS) is a large-scale continuous sample survey project that was initiated by the Institute of Sociology, which is part of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. The CSS is conducted every 2 years, with the first wave of the longitudinal survey conducted in 2006. The data for this study was primarily derived from the CSS conducted in 2013 because the items that measure national pride and pro-environmental tendencies were only included in this wave of the survey.

For the CSS (2013), responses were obtained from 10,206 participants. Of these participants, 2,004 participants were excluded because they did not answer the required questions or chose “unclear”. 8,202 participants (80.36% of the entire sample) provided complete responses covering our variables of interest, and their responses were therefore included in the current study.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 National pride

The following item was used to assess participants’ national pride: “I have often been proud of the country’s achievements.” Participants were asked to rate their feelings on a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree) (M = 3.713, SD = 0.694).

2.2.2 Pro-environmental tendencies

One item was used to measure participants’ pro-environmental tendencies: “If I have time, I am very willing to join an environmental NGO.” The response scale ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree) (M = 3.040, SD = 0.745).

2.2.3 Demographics

It has been documented that gender, age, and education are demographic factors influencing individual pro-environmental behaviors (López-Mosquera et al., 2015). Thus, we included age (M = 45.447, SD = 13.558), gender (dummy coded as 1 = female, 0 = male; M = 0.454, SD = 0.498), and education (1 = no qualifications, 9 = graduate degree; M = 3.408, SD = 1.934) as control variables.

2.3 Results

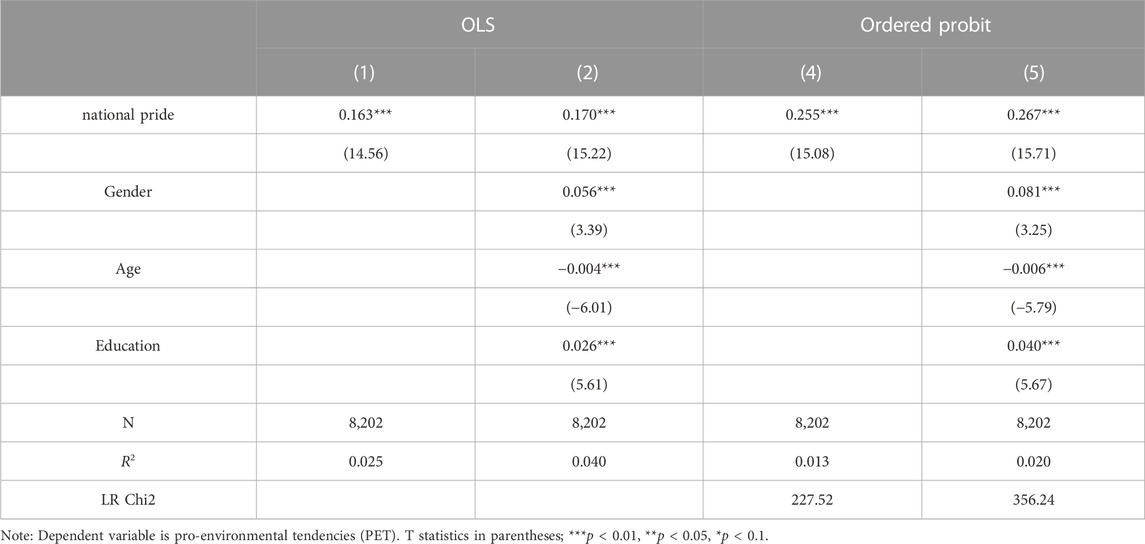

We employed two empirical statistical schemes, OLS regression and ordered probit regression, to examine the relationship between national pride and PET. Table 1 shows that all the coefficients of national pride are significantly positive (p < 0.01), suggesting that there is a significantly positive correlation between national pride and PET, verifying H1. Moreover, the results also offer a set of findings regarding demographic variables. The coefficients of gender, age, and education are significantly positive, negative, and positive, respectively, suggesting that women, younger people, and people with more education are more willing to engage in pro-environment behaviors. The results are consistent with the findings of López-Mosquera et al. (2015).

3 Study 2

In this study, we used videos of political-economic achievements and historical-cultural achievements to prime participants’ national pride and investigate the effects of promotional tools of national pride on improving individuals’ PET. One thing to note was that using achievement videos to prime national pride might also arouse participants’ positive affect, which would impact their PET (Ibanez et al., 2017; Chatelain et al., 2018). The interference of positive affect had to be controlled in order to accurately examine the effect of priming national pride on PET. In addition, we also tried to control the influence of important personal traits that determine individuals’ PET, such as environmental attitude (Ajzen, 1991).

3.1 Participants and procedures

A total of 305 participants were recruited using Wenjuanxing a widely used online survey platform in China. The participants were randomly divided into three priming groups. Participants in the first group (pevideo group, 102 participants, 70 females; mean age was 22.706) watched a video (about 3 min long), depicting some of China’s key political-economic achievements, such as the founding ceremony of the People’s Republic of China, the reform and opening up initiative, the return of Hong Kong to China, the country’s accession to the WTO, and the development of 5G and high-speed rail technology. Participants in the second group (hcvideo group, 103 participants, 71 females; mean age is 21.933) watched a video (about 3 min long), depicting some of China’s key historical-cultural achievements, such as China’s four great inventions, the four great classics of China, the heroes of modern Chinese history, China’s poetry and other literary classics, and quintessential portrayals of Chinese culture and art. And participants in the third group (control group, 100 participants, 64 females; mean age is 22.446) did not watch any videos.

Participants who followed the link were redirected to an online experiment structured in four sections: The first asked participants to indicate their environmental attitude. The second included the priming process, followed by scales on national pride and positive affect. The third asked participants to complete scale of pro-environmental tendencies. The final section collected demographic information.

3.2 Measures

3.2.1 National pride

We used the item “How proud are you of your country?” to assess national pride (Müller-Peters, 1998). The response scale ranged from 1 (not proud at all) to 7 (very proud).

3.2.2 Pro-environmental tendencies (PET)

We used three items to assess pro-environmental tendencies: “Are you willing to practice garbage sorting in your daily life?” “Are you willing to reuse paper, shopping bags, etc. in your daily life and work?” “Are you willing to pay higher prices for green products (e.g., green organic food, easily degradable products, energy-saving and environment-friendly home appliances, pollution-free daily necessities, new energy vehicles, etc.)?”. The response scale ranged from 1 (not at all) to 7 (extremely). The mean value of above items was used to measure participants’ PET (Cronbach’s α = 0.763).

3.2.3 Positive affect

PANAS was used to assess participants’ positive affect at the time (Watson et al., 1988). The response scale ranged from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). The mean value of the scores for the five positive affect items (proud, enthusiastic, inspired, excited, and determined) served as a measure of positive affect (Cronbach’s α = 0.874).

3.2.4 Control variables

We considered participants’ environmental attitudes and several background variables, such as gender, age, and family income. Environmental attitude was measured with the NEP scale (Dunlap et al., 2000), which comprised 15 items. The response scale ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The mean value was used as environmental attitude variable (Cronbach’s α = 0.801). We applied a dummy code to the gender variable (male = 0 and female = 1). We used participants’ ages for the age variable. The level of average monthly household income is as follows: 1 = less than 5,000 yuan; 2 = 5,000 to 10,000 yuan; 3 = 10,000 to 15,000 yuan; 4 = 15,000 to 20,000 yuan; 5 = more than 20,000 yuan.

3.3 Results

3.3.1 Descriptives

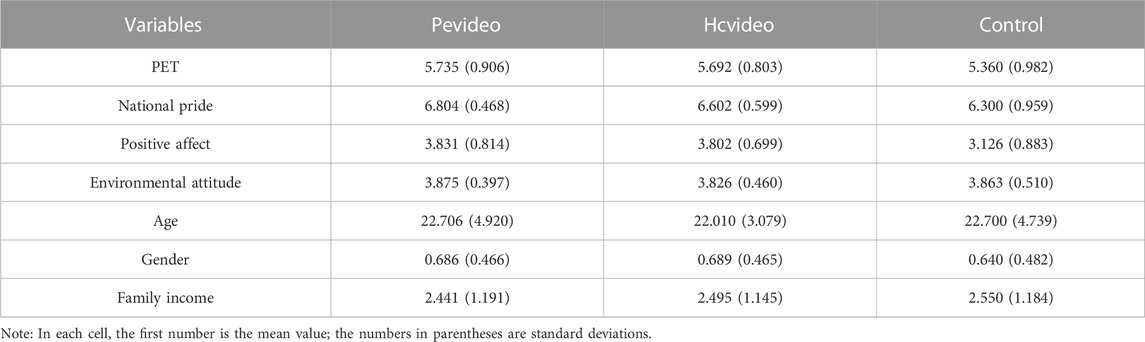

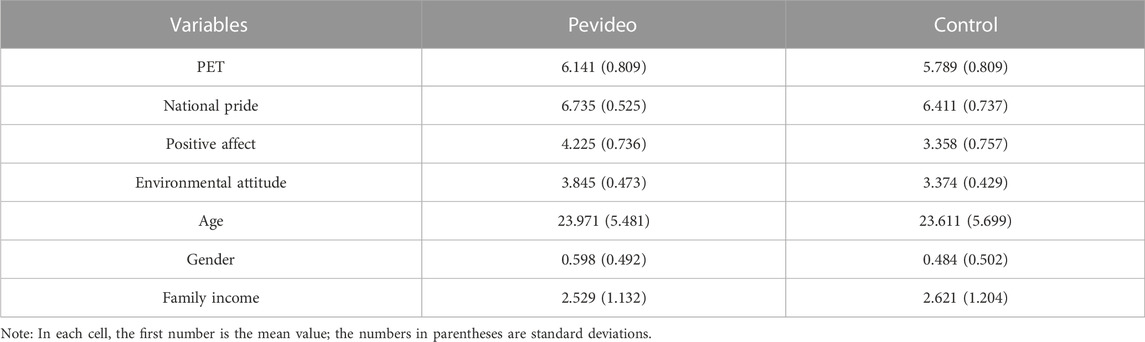

Table 2 presents overall descriptive statistics.

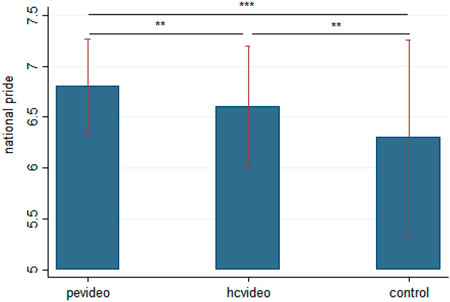

3.3.2 Priming effect on national pride

The ANOVA results show that the priming effect of national achievements on participants’ national pride is significant (F (2, 304) = 13.08, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.08; see Figure 1). Specifically, participants’ national pride in the pevideo group is significantly higher than that in the hcvideo and control groups (Fpe-con (1, 200) = 22.68, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.102; Fpe-hc (1, 203) = 7.223, p = 0.008, η2 = 0.034). Participants’ national pride in the hcvideo group is significantly higher than that in the control group (Fhc-con (1, 201) = 7.282, p = 0.008, η2 = 0.035). The findings suggest that while both political-economic and historical-cultural achievements can effectively arouse national pride, political-economic achievements have a more effective priming effect on participants’ national pride, confirming H3 and the first part of H2.

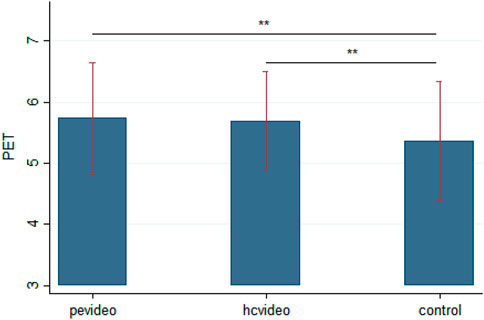

3.3.3 Priming effects on PET

To examine the priming effect on promoting PET, we analyzed differences in participants’ PET between the three priming groups. The ANOVA results show that participants’ PET in the pevideo group and the hcvideo group are significantly higher than that in control group (Fpe_con (1, 201) = 7.971, p = 0.005, η2 = 0.068; Fhc_con (1, 201) = 6.997, p = 0.009, η2 = 0.064), while there is no significant difference between the pevideo group and the hcvideo group (Fpe_con (1, 201) = 0.128, p = 0.721; see Figure 2). Supplementary Table S1 in the online Appendix reports the results of OLS regression, showing that the coefficients of the dummy variables for priming (b = 0.364, p = 0.001), pevideo priming (b = 0.367, p = 0.004), and hcvideo priming (b = 0.362, p = 0.004) are both significantly positive. The findings suggest that priming with national achievements exerts a significant effect on promoting participants’ PET.

3.3.4 Pathway analysis

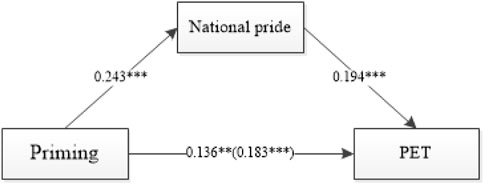

To investigate whether the effect of priming on promoting PET works by arousing participants’ national pride, we analyzed the mediating effect of national pride on the relationship between priming and PET. Moreover, we employed the bootstrap method (2000 random samples) as a supplementary test for the mediating effect (Hayes, 2018). Figure 3 presents the relationships between priming, national pride, and PET. Results show that national pride exerts a mediating effect on the relationship between priming and PET (b = 0.194, p = 0.007, 95% CI [0.012, 0.083]). The ANOVA results show that priming not only arouses participants’ national pride but also has a significant effect on participants’ positive affect (Fpe-con (1, 201) = 34.867, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.148; Fhc-con (1, 202) = 36.698, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.154; see Supplementary Figure S1). In order to eliminate the interference of positive affect on the effect of priming national pride on PET, we took ratings of positive affect as a control variable and ratings of national pride as an independent variable in the OLS regression model. The regression results in Supplementary Table S2 show that the coefficient of national pride is significantly positive (b = 0.190, p = 0.008), while the coefficient of positive affect is also significantly positive (b = 0.145, p = 0.015). Therefore, priming with national achievements successfully inspires participants’ national pride and, consequently, promotes their PET, verifying the second part of H2. Moreover, positive affect aroused by priming also exerts a significant impact on participants’ PET. Figure 3.

FIGURE 3. The results of mediating effect. Note: The independent variable is prime, prime = 1, 2, and 3 if the observations are from control group, hcvideo group, and pevideo group, respectively. The dependent variable are rating of PET. The mediating variable is rating of national pride. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

4 Study 3

Further, we wanted to investigate whether individuals with higher national pride were more willing to comply with the national environmental will to engage in pro-environmental actions. For this purpose, we took the experiment in Study 2 as the no-information treatment and conducted an information treatment experiment in Study 3, providing additional national environmental norm information to the participants. Therefore, in the analysis section, we combined the experimental data from Study 2 with that from study 3. By comparing participants’ PET between the information and no-information treatments, we can examine how participants with varying levels of national pride perform when they are aware of their country’s environmental norms.

4.1 Participants and procedures

The procedure was basically the same as that used in Study 2 but with two changes. The first was the sole use of the video depicting China’s political-economic achievements to prime participants’ national pride, given that these achievements were more effective than historical-cultural achievements in priming national pride in Study 2. The second change entailed the provision of information on a national environmental initiative to participants before they started filling out the PET scale. The information was as follows:

Green, the color of life, is the most distinctive undertone of contemporary China’s development. The 14th Five-Year Plan and the outline of the vision for 2035 call for promoting green development and harmony between humans and nature. Ecological progress is closely related to everyone, and everyone should contribute to it. We should foster a moderately frugal, green, low-carbon, civilized, and healthy way of life and consumption patterns and encourage the participation of the whole society.

A total of 197 participants were recruited for Study 3. There were 102 participants in the pevideo group (61 females; mean age is 23.97) and 95 participants in the control group (49 females; mean age is 23.61).

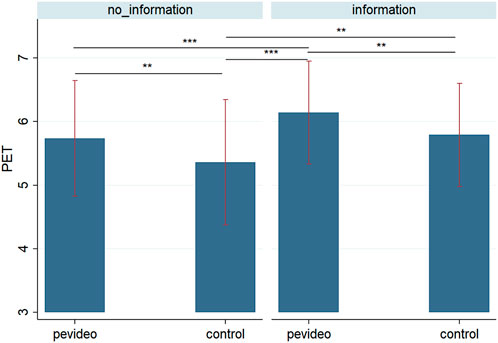

4.2 Results

Table 3 presents overall descriptive statistics. In information treatment (experiment of Study 3), the priming with political-economic achievements also has a significant effect on promoting national pride (F (1, 196) = 12.832, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.078) and PET (F (1, 196) = 9.259, p = 0.003, η2 = 0.072), suggesting that the priming effect of national achievements is robust. Compared with no-information treatment (the pevideo and control groups of Study 2), highlighting national environmental norm information in information treatment has a significantly positive impact on participants’ PET (F (1, 398) = 22.056, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.108). Figure 4 shows that the mean PET of the pevideo group in information treatment is significantly higher than that of the pevideo group in no-information treatment (t (202) = 3.369, p = 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.472), indicating that emphasizing national environmental norm information while priming national pride has the greatest promotional effect on individuals’ PET. The findings verify H4.

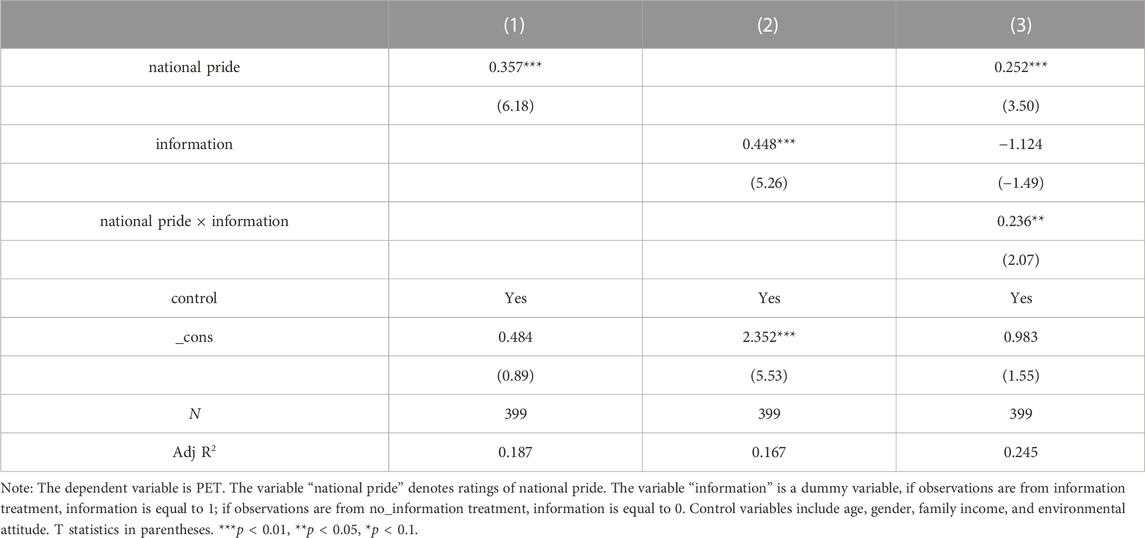

We further analyzed the interaction effect between the degree of national pride and highlighting norm information. Table 4 presents the results of OLS regression, showing that the participants’ national pride has a significantly positive correlation with PET (b = 0.252, p = 0.001), while the coefficient of the interaction between national pride and the dummy variable of highlighting information is significantly positive (b = 0.236, p = 0.039). The finding suggests that compared with the no information condition, when participants are introduced with national environmental norm information, the effect of national pride on PET is even stronger.

5 General discussion

To demonstrate that national pride can be used as a promotional tool for individuals’ PET, this article reports evidence from one survey and two experimental studies showing that national pride can indeed impact individuals’ PET. Moreover, the present article also shows that priming with national achievements is an effective way to manipulate individuals’ sense of national pride. The results also show that people with higher national pride are more willing to conform to national environmental norms, and combining priming national pride with highlighting national environmental norm information is more effective in promoting PET. The present paper is one of the few that uses the priming method to examine the relationship between national pride and PET and the effect of the promotion tools of national pride.

The current findings confirm and expand research showing a connection between national pride and individual behaviors (Kim et al., 2013; Macintyre et al., 2021) and add to the growing literature on the factors that influence pro-environmental tendencies (Kollmuss and Agyeman, 2002; Brieger, 2019; Milfont et al., 2020). In particular, the present study shows that people’s feelings of national pride are indeed related to their tendencies to engage in pro-environmental actions. Specifically, people with a higher sense of national pride have higher PET. Moreover, the findings of this study not only demonstrate the correlation between national pride and individuals’ PET but also verify the effect of priming on national pride and PET. It suggests that priming national pride is a novel and effective way to promote individuals’ PET.

The findings show that, in the Chinese context, political-economic achievements and historical-cultural achievements are both effective in priming people’s national pride, but political-economic achievements are more effective. The prominence of China’s political and economic achievements and its people’s cultural inconfidence may be the potential reasons for that result. Fabrykant and Magun (2016) argued that faster economic growth in less developed countries increases the pride in mass achievements at the cost of the elitist ones. However, they also found that there are significant differences in how people in different countries perceive different types of achievements. For example, Russian national pride is closely related to economic and political achievements (Fabrykant and Magun, 2019), while South Koreans exhibit greater national pride in their achievements in sports, history, and science and technology than in politics and social welfare systems (Chung and Choe, 2008). We argue that the priming effects of different types of achievements may be country-dependent and would be different in different countries.

The current paper also finds that people with higher degrees of national pride are more willing to comply with national norms and act in ways that reflect the national will. The findings implicate the role of social identity theory in explaining the correlation between national pride and PET. Individuals’ PET would increase with the strengthening of their sense of national pride and pro-environmental group norms (Fielding and Hornsey, 2016). What’s more, the present paper provides optimism evidence for a combination of different nudging tools, such as priming and social norm informing, contributing to the nudge literature that explores moderate ways to promote PET (Wee et al., 2021).

Our study did, however, have several limitations. First, this study was conducted in a Chinese context, which resulted in the fact that the conclusions may not be universal for other countries with different cultures, histories, economic environments, and political systems. The Chinese people are more collectivist, while people in many western countries are more individualistic. Literature shows that individualism affects national pride negatively while collectivism affects it positively (Yoon, 2010; Asante, 2020). So the difference in cultural traits between different countries would influence people’s feelings of national pride. And as discussed above, the priming effect of national achievements would be country-dependent. Therefore, further research should be carried out in different economic and cultural contexts.

Second, the present paper focuses on the impact of national pride on individual pro-environmental tendencies. The gap between pro-environmental tendencies and behavior has been widely documented (Farjam et al., 2019), so the effect of priming national pride on realistic pro-environmental behaviors requires further study.

Third, most of the participants in Study 2 and 3 are college students and young adults. Age has been found to be an important factor influencing an individual’s sense of national pride (Smith and Kim, 2006). On the one hand, since the founding of the People’s Republic of China, China’s institutional structure and economic development have undergone tremendous changes. So, there are significant differences in the participation and experience of people of different ages in this process, which would lead them to have different feelings about the national achievements. On the other hand, in the last 30 years, in the state-controlled propaganda apparatus, media and education the priority has shifted from communist ideology to a shared sense of Chinese national identity, history and culture, and the stronger patriotism of post-1980 confirms the success of this endeavor (Shan, 2014). Therefore, it is necessary to investigate the priming effect on individuals’ national pride in a greater age range.

Finally, since the participants are mainly students, we chose the pro-environment behaviors that are more frequent and easier for them to participate in when designing the scale. Some important pro-environment behaviors, such as energy use and transportation choice, were not involved in this study. Therefore, the future study should examine the effects of priming national pride on tendencies for more kinds of pro-environmental behaviors.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee of South China Normal University. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

PW, ZD, and SC designed the experiment. PW and MX carried out the experiment. PW analyzed the data, wrote the paper. PW, ZD, SC, and MX revised the paper.

Funding

This research was supported by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2020M682739), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (71602138 and 71973048).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fenvs.2023.1103635/full#supplementary-material

References

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 50 (2), 179–211. doi:10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Asante, K. T. (2020). Individualistic and collectivistic orientations: Examining the relationship between ethnicity and national attachment in Ghana. Stud. Ethn. Natl. 20 (1), 2–24. doi:10.1111/sena.12313

Aydin, E., Bagci, S. C., and Kelesoglu, İ. (2022). Love for the globe but also the country matter for the environment: Links between nationalistic, patriotic, global identification and pro-environmentalism. J. Environ. Psychol. 80, 101755. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101755

Bimonte, S., Bosco, L., and Stabile, A. (2020). Nudging pro-environmental behavior: Evidence from a web experiment on priming and WTP. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 63 (4), 651–668. doi:10.1080/09640568.2019.1603364

Bonini, N., Hadjichristidis, C., and Graffeo, M. (2018). Green nudging. Acta Psychol. Sin. 50 (8), 814–826. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1041.2018.00814

Brewer, M. B., and Kramer, R. M. (1986). Choice behavior in social dilemmas: Effects of social identity, group size, and decision framing. J. personality Soc. Psychol. 50 (3), 543–549. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.50.3.543

Brieger, S. A. (2019). Social identity and environmental concern: The importance of contextual effects. Environ. Behav. 51 (7), 828–855. doi:10.1177/0013916518756988

Byerly, H., Balmford, A., Ferraro, P. J., Hammond Wagner, C., Palchak, E., Polasky, S., et al. (2018). Nudging pro-environmental behavior: Evidence and opportunities. Front. Ecol. Environ. 16 (3), 159–168. doi:10.1002/fee.1777

Chatelain, G., Hille, S. L., Sander, D., Patel, M., Hahnel, U. J. J., and Brosch, T. (2018). Feel good, stay green: Positive affect promotes pro-environmental behaviors and mitigates compensatory “mental bookkeeping” effects. J. Environ. Psychol. 56, 3–11. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2018.02.002

Chung, K., and Choe, H. (2008). South Korean national pride: Determinants, changes, and suggestions. Asian perspect. 32 (1), 99–127. doi:10.1353/apr.2008.0032

DRCWBG (2022). Four decades of poverty reduction in China: Drivers, insights for the world, and the way ahead. Hampshire, United States: World Bank.

Dunlap, R. E., Van Liere, K. D., Mertig, A. G., and Jones, R. E. (2000). New trends in measuring environmental attitudes: Measuring endorsement of the new ecological paradigm: A revised NEP scale. J. Soc. issues 56 (3), 425–442. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00176

Evans, M. D., and Kelley, J. (2002). National pride in the developed world: Survey data from 24 nations. Int. J. public Opin. Res. 14 (3), 303–338. doi:10.1093/ijpor/14.3.303

Fabrykant, M., and Magun, V. (2019). Dynamics of national pride attitudes in post-soviet Russia, 1996–2015. Natl. Pap. 47 (1), 20–37. doi:10.1017/nps.2018.18

Fabrykant, M., and Magun, V. (2016). “Grounded and normative dimensions of national pride in comparative perspective,” in Dynamics of national identity: Media and societal factors of what we are (London, UK: Routledge), 109–138.

Farjam, M., Nikolaychuk, O., and Bravo, G. (2019). Experimental evidence of an environmental attitude-behavior gap in high-cost situations. Ecol. Econ. 166, 106434. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2019.106434

Feygina, I., Jost, J. T., and Goldsmith, R. E. (2010). System justification, the denial of global warming, and the possibility of “system-sanctioned change. Personality Soc. Psychol. Bull. 36 (3), 326–338. doi:10.1177/0146167209351435

Fielding, K. S., and Hornsey, M. J. (2016). A social identity analysis of climate change and environmental attitudes and behaviors: Insights and opportunities. Front. Psychol. 7, 121. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00121

Gangl, K., Torgler, B., and Kirchler, E. (2016). Patriotism's impact on cooperation with the state: An experimental study on tax compliance. Polit. Psychol. 37 (6), 867–881. doi:10.1111/pops.12294

Ha, S. E., and Jang, S. J. (2015). National identity, national pride, and happiness: The case of South Korea. Soc. Indic. Res. 121 (2), 471–482. doi:10.1007/s11205-014-0641-7

Hamada, T., Shimizu, M., and Ebihara, T. (2021). Good patriotism, social consideration, environmental problem cognition, and pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors: A cross-sectional study of Chinese attitudes. SN Appl. Sci. 3, 1–16.

Han, Y., Duan, H., Du, X., and Jiang, L. (2021). Chinese household environmental footprint and its response to environmental awareness. Sci. Total Environ. 782, 146725. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.146725

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Commun. Monogr. 85 (1), 4–40. doi:10.1080/03637751.2017.1352100

Huddy, L., and Khatib, N. (2007). American patriotism, national identity, and political involvement. Am. J. Political Sci. 51 (1), 63–77. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2007.00237.x

Ibanez, L., Moureau, N., and Roussel, S. (2017). How do incidental emotions impact pro-environmental behavior? Evidence from the dictator game. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 66, 150–155. doi:10.1016/j.socec.2016.04.003

Kim, Y., KiTae, Y., and Ko, Y. J. (2013). Consumer patriotism and response to patriotic advertising: Comparison of international vs. national sport events. Int. J. Sports Mark. Spons. 14 (3), 74–96. doi:10.1108/IJSMS-14-03-2013-B006

Kollmuss, A., and Agyeman, J. (2002). Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 8 (3), 239–260. doi:10.1080/13504620220145401

Lewandowsky, S., Gignac, G. E., and Oberauer, K. (2013). Correction: The role of conspiracist ideation and worldviews in predicting rejection of science. PloS one 8 (10), e0134773. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0134773

Liu, J., Thomas, J. M., and Higgs, S. (2019). The relationship between social identity, descriptive social norms and eating intentions and behaviors. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 82, 217–230. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2019.02.002

López-Mosquera, N., Lera-López, F., and Sánchez, M. (2015). Key factors to explain recycling, car use and environmentally responsible purchase behaviors: A comparative perspective. Resour. Conservation Recycl. 99, 29–39. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2015.03.007

Macintyre, A., Chan, H. F., Schaffner, M., and Torgler, B. (2023). National pride and tax compliance: A laboratory experiment using a physiological marker. PloS one 18 (1), e0280473. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0280473

Mayda, A. M., and Rodrik, D. (2005). Why are some people (and countries) more protectionist than others? Eur. Econ. Rev. 49 (6), 1393–1430. doi:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2004.01.002

Milfont, T. L., Osborne, D., Yogeeswaran, K., and Sibley, C. G. (2020). The role of national identity in collective pro-environmental action. J. Environ. Psychol. 72, 101522. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101522

Müller-Peters, A. (1998). The significance of national pride and national identity to the attitude toward the single European currency: A europe-wide comparison. J. Econ. Psychol. 19 (6), 701–719. doi:10.1016/S0167-4870(98)00033-6

Reese, G., Proch, J., and Finn, C. (2015). Identification with all humanity: The role of self-definition and self-investment. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 45 (4), 426–440. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2102

Risse, L. (2010). And one for the country’ the effect of the baby bonus on Australian women’s childbearing intentions. J. Popul. Res. 27 (3), 213–240. doi:10.1007/s12546-011-9055-4

Schultz, P. W., Milfont, T. L., Chance, R. C., Tronu, G., Luís, S., Ando, K., et al. (2014). Cross-cultural evidence for spatial bias in beliefs about the severity of environmental problems. Environ. Behav. 46 (3), 267–302. doi:10.1177/0013916512458579

Shan, W. (2014). Chinese nationalism: National pride and attitudes towards others. East Asian Policy 5 (04), 31–42. doi:10.1142/S1793930513000342

Shariff, A. F., Willard, A. K., Andersen, T., and Norenzayan, A. (2016). Religious priming: A meta-analysis with a focus on prosociality. Personality Soc. Psychol. Rev. 20 (1), 27–48. doi:10.1177/1088868314568811

Skitka, L. J. (2005). Patriotism or nationalism? Understanding post-september 11, 2001, flag-display behavior 1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 35 (10), 1995–2011. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2005.tb02206.x

Smith, T. W., and Kim, S. (2006). National pride in comparative perspective: 1995/96 and 2003/04. Int. J. public Opin. Res. 18 (1), 127–136. doi:10.1093/ijpor/edk007

Tajfel, H. (1974). Social identity and intergroup behaviour. Soc. Sci. Inf. 13 (2), 65–93. doi:10.1177/053901847401300204

Tajfel, H., and Turner, J. C. (1982). Social psychology of intergroup relations. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 33 (1), 1–39. doi:10.1146/annurev.ps.33.020182.000245

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., and Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. personality Soc. Psychol. 54 (6), 1063–1070. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063

Wee, S. C., Choong, W. W., and Low, S. T. (2021). Can “nudging” play a role to promote pro-environmental behaviour? Environ. Challenges 5, 100364. doi:10.1016/j.envc.2021.100364

Wong, K. K. (2010). Environmental awareness, governance and public participation: Public perception perspectives. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 67 (2), 169–181. doi:10.1080/00207231003683424

Yoon, K. I. (2010). Political culture of individualism and collectivism. Doctoral dissertation. Michigan: university of Michigan.

Keywords: pro-environmental tendencies, national pride, priming, social norm information, national achievement

Citation: Wang P, Dong Z, Cai S and Xiao M (2023) Proud of you, so act for you? The role of national pride in promoting individual pro-environmental tendencies. Front. Environ. Sci. 11:1103635. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2023.1103635

Received: 09 January 2023; Accepted: 01 March 2023;

Published: 09 March 2023.

Edited by:

Seth Oppong, University of Botswana, BotswanaReviewed by:

Nathaniel Geiger, Indiana University, United StatesJun Luo, Zhejiang University of Finance and Economics, China

Copyright © 2023 Wang, Dong, Cai and Xiao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Pengcheng Wang, Y2hlbmdwd0AxMjYuY29t

Pengcheng Wang

Pengcheng Wang Zhiqiang Dong

Zhiqiang Dong Shenggang Cai

Shenggang Cai Min Xiao1

Min Xiao1