- Department of Urban and Rural Planning, School of Architecture, Southwest Jiaotong University, Chengdu, China

Within the Anglo-American literature, commercial, along with residential, gentrification has often been treated as an attendant neighborhood phenomenon. This study aims to uncover the distribution of areas for emerging consumption that indicate the occurrence of commercial gentrification, as well as to explain the development process and spatial correlations of commercial gentrification in Chengdu, a large Chinese city. With the data of points of interest (POIs), the study categorizes new retail places for commercial gentrification and conducts spatial and statistical analyses. The following findings are revealed: First, the distribution of new retail places changed from a monocentric to a polycentric structure in the main urban areas of Chengdu from 2010 to 2020, wherein high-density areas were partially overlapped with traditional commercial centers. Second, commercial gentrification in Chengdu was presented by the fastest growth of the entertainment services in the 2010s. Third, commercial gentrification in Chengdu shifted from a centripetal to a centrifugal development pattern from 2010 to 2020. The geographies of development were variegated, connected with multiple location attributes and impacted by local governments’ urban development strategies. Fourth, commercial gentrification was positively correlated with the growth of knowledge-intensive industries but negatively related to the change in both traditionally secondary and tertiary sectors in the past decade. Finally, changes in housing prices showed no connection with commercial gentrification during the studied period. The study suggests that commercial gentrification should be treated as a phenomenon of industrial gentrification, independent of residential gentrification. The commercial spatial planning in the city should play close attention to the synergic and exclusive relations between new retail industries and the evolution of industrial spaces in the emerging post-industrial city economy.

1 Introduction

Gentrification has been extensively studied on a global scale since 2000 (Atkinson et al., 2004; Lees et al., 2016). The connotations surrounding this concept range from early-stage residential substitution to the upward filtering of urban socio-spatial structures. The literature on gentrification has developed various analytical concepts, including school-district gentrification, rural gentrification, and commercial gentrification (Huang and Yang, 2012). Commercial gentrification is the transformation of residential, commercial, or industrial spaces into spaces with higher-value retail businesses; this process often entails the displacement of original residents and business owners (Gonzalez and Waley, 2003; Zukin et al., 2009).

In general, commercial gentrification entails emerging consumption activities and the advancement of retail industries within a city. Without a precise definition, the existing literature refers to emerging consumption as those activities cultivated in the formation of new consumer culture and consumption patterns (Bird and Macedo, 2021). However, while traditional consumption meets the necessary material and service demands of residents in daily life, emerging consumption creates and satisfies their higher-level demands, such as those for cultural capital and social status (Zhu, 2020; Areiza-Padilla and Manzi-Puertas, 2021). Moreover, the application of new technologies (e.g., internet technology and social media platforms) in transactions further distinguishes emerging from traditional consumption (Sun and Wang, 2021; Xiang et al., 2021). Emerging consumption gives rise to new consumption spaces and brings about the evolution of urban space. In particular, both commercial and residential gentrification can be contextualized in the emerging consumption of the new middle class, who, in Western cities, denotes a particular segment of the service classes with greater access to cultural and economic capital in post-industrial society (Zukin et al., 2009; Sun et al., 2018).

In China, commercial gentrification emerged amid unique social and political dynamics. Since the founding of the People’s Republic of China, urban society in the country has been production-oriented, with individual consumption substituted by collective consumption. Since the country’s process of reform and opening-up, its market economy grew dramatically, leading to sharp increases in citizens’ average income; and Chinese society has gradually shifted from a production-oriented society to a consumption-oriented society (Davis, 2000; Tomba, 2004). The 2010s witnessed a significant acceleration in the post-industrial social transformation of large Chinese cities and, in turn, in the growth of the Chinese middle class through the development of new tech-heavy industries. International urban development strategies have encouraged intercity labor competition, boosting human capital development. However, given the lack of equitable development across China’s regions, many major cities still struggle to use high-skilled workers (Yang and Zhou, 2018).

Furthermore, China’s central and local governments have played a significant role in the development of a consumption-oriented society and economy. In 2015, the State Council released Guidelines on Accelerated Cultivation of New Supply Power by Actively Exerting the Leading Effect of Emerging Consumption (hereafter, the 2015 policy of Guidelines on Emerging Consumption) to accelerate the development of emerging consumption styles. The 14th Five-Year Plan, released on 11 March 2021, proclaimed the promotion of domestic consumption to be the main objective of social and economic development. The plan includes a series of national strategies, such as upgrading traditional consumption, encouraging new consumption types, and developing international central cities of consumption.

Hence, research into commercial gentrification is theoretically important for explaining the spatial characteristics of emerging consumption and their effects on urban transformation in the unique context of major Chinese cities. Furthermore, it can enrich comparative analyses between commercial and residential gentrification. In more practical terms, it generates implications for the optimization of commercial spatial planning. In this paper, Chengdu—a representative consumption-oriented city in southwest China—is used as a case study to assess the spatial evolution of commercial gentrification in Chinese cities, especially concerning the relevant spatial correlations and effects of commercial gentrification.

2 Emerging consumption, commercial gentrification, and urban change

In the Western literature on this subject, commercial gentrification is considered an accompanying neighborhood phenomenon to residential gentrification (Sun and Song, 2021). Residential gentrification results from the housing choices of the emerging middle class in inner cities (Yang et al., 2019a; Yang et al., 2019b). These housing choices then influence the resource-allocation decisions of business owners, leading to commercial gentrification as a second-hand phenomenon (Davidson and Loretta, 2010; Pastak et al., 2019). Therefore, the forces of commercial gentrification have been explained by two traditional theories of residential gentrification focusing on the demand side or the supply side. On the one hand, humanist scholars represented by David Ley (Ley, 1996) assert that gentrification in Western cities since the 1980s has mainly stemmed from a dramatic increase in high-skilled, middle-class individuals and their consumption patterns (Zukin, 1982; Hamnett, 2003). The new middle-class residents may also accelerate the restructuring of the community retail industries through local marketing strategies (Keatinge and Deborah, 2016). On the other hand, scholars like Neil Smith (Smith, 1996) argue that both residential and commercial gentrification are the result of basic capitalist economic dynamics (i.e., the deprivation and agglomeration of surplus values). From this perspective, gentrification essentially comprises the plundering of rent gaps by reinvesting in recession-affected inner-city areas with high economic potential. A few studies in urban China emphasize that the pursuit of rent gaps of commercial land by local governments and capitalists is the main reason for commercial gentrification in large cities (Wang, 2011; Liu and Chen, 2018; Song et al., 2020).

On this basis, the spatial characteristics of commercial gentrification have largely been investigated by focusing on individual cases, lacking proper assessments of city-level laws (Liu et al., 2019). For instance, the literature has spatially characterized commercial gentrification in Western cities with the following three aspects: 1) increasing “boutiques” featuring leisure experiences and cultural attributes; 2) growing large corporate chain; and 3) the declining of localized retail formats (Zukin et al., 2009; Pastak et al., 2019; Sun and Song, 2021). Still, commercial gentrification generally occurs in inner-city areas and on certain historically or culturally significant blocks (Pratt, 2009). Song et al. (2020) creatively characterize the commercial gentrification of Nanjing from 2008 to 2018, proposing a corresponding development pattern: leaping-type diffusion from traditional business centers to surrounding emerging business districts. This development pattern comprises three spatial types: overall implantation type, invasive succession type, and transformation and upgrading type.

In addition to research explicitly focusing on commercial gentrification, research on spaces for emerging consumption in Chinese cities is gaining prominence with a particular focus on e-commerce spaces and web celebrity shops. More specifically, researchers have proposed that the distribution of e-commerce spaces has a macro-agglomerated and multi-core structure (Sun and Wang, 2021). Web celebrity shops also present a structure of multi-core agglomeration, and they have developed from central areas to the urban periphery (Xiang et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2021). While these new retail places have distribution laws identical to traditional retail places (i.e., invisible consumption spaces still present a mode of large-scale development and are greatly affected by traditional urban commercial centers), they also present unique characteristics (e.g., the distribution of online celebrity spaces is more even, and invisible consumption spaces harbor more low-rent commercial and residential buildings in central areas). Furthermore, new consumption types have boosted the development of rural consumption economies, bridging the divide between urban and rural areas (Xu et al., 2021). In summary, the literature has largely focused on spaces for the individual type of consumption; but it lacks systematic research on spaces for emerging consumption.

The social influence of gentrification—a major research topic in critical geography—has risen greatly in recent years. Increasingly, research has begun to focus on how gentrification excludes ethnic minority groups and other disadvantaged groups (Sakzlolu and Lees, 2020; Huang and Liu, 2022). Both commercial gentrification and residential gentrification are generally seen as squeezing the survival space for original residents and traditional industries by driving retail shop/house prices higher, forcing outward migration (Gonzalez and Waley, 2003; Zukin, 2008; Ferm, 2016; Song et al., 2020), and destroying the authenticity of the city (Martinez, 2016). Startlingly, the effect of commercial gentrification on urban spatial evolution has scarcely been explored. According to some studies, commercial gentrification can revitalize the economies, improve built environments, and stimulate new employment opportunities in inner-city areas (Bridge and Dowling, 2001; Meltzer, 2016; Sun et al., 2018). Creative industries and historical streets generally interact with the spaces for emerging consumption in a bidirectional causal relationship (Wang et al., 2019). Furthermore, commercial gentrification boosts the globalization of consumer culture (Mermet, 2017).

Based on the insight provided by the studies detailed above, this study screens out the sorts of retail places that signify the advent of commercial gentrification. It then quantitatively analyzes the spatial distribution of these new retail places in 2010, 2015, and 2020 in the sub-districts of Chengdu, which is called Street (jiedao) in China. Street (Jiedao) refers to the lowest level of administrative units in Chinese cities. Next, this study measures the development levels of commercial gentrification in different Streets using the location quotient (LQ) index. Then, it reveals the correlations between commercial gentrification and urban spatial evolution from five major perspectives: knowledge-intensive industrial space, manufacturing space, ordinary office space, commercial space, and residential space. In this way, the study depicts the characteristics of commercial gentrification at a city level against the context of urban China and offers a comparison between the commercial gentrification of Chengdu with that of Western cities.

3 Retail places representing commercial gentrification

Residential gentrification has been traditionally measured by socioeconomic and housing indicators. However, retail industry indicators for measuring commercial gentrification have not yet been established (Kosta, 2019). This study proposes categories of retail places representing commercial gentrification by considering areas for emerging consumption in general, and the consumer culture of China’s new middle class in particular. In the 2015 policy of Guidelines on Emerging Consumption, the types of emerging consumption were defined as service consumption, information consumption, green consumption, fashion consumption, quality consumption, and rural consumption, all of which respond to the changing consumer culture that values meaningful experience, health, knowledge, individualization, quality, and environmental protection (Yin, 2005).

The new middle class relevant to gentrification research in Western literature generally comprises professional and managerial personnel workers—members of the professional and managerial class (PMC)—in the service industry aged 30–45 years. Relative to that in the West, China’s new middle class is both smaller and younger (Li, 2010). Additionally, personal consumption has only recently begun to be promoted in Chinese cities, meaning that the consumer culture of the new middle class is forming and has a low internal homogeneity (Wang and Lau, 2009). Given these dynamics, China’s emerging middle class often engages in consumption with the aim of achieving greater social distinction and status. Therefore, its consumption pattern is characterized by “international brand consumption, hedonic consumption and conspicuous consumption” (Yu, 2005). Given the rapid growth of the new middle class in recent years, branding-oriented material consumption patterns are increasingly being overshadowed by rational and personalized consumption patterns. Middle-class consumers tend to appreciate the quality, experience, and pursuit of knowledge through consumption (Zhu, 2020).

In their investigation of Nanjing’s commercial gentrification, Song et al. (2020) considered six classes of high-end commercial places, including exotic cuisine, coffee and tea, cosmetology and body care, yoga and fitness, business clubs, and bars. Wang and Gao (2008) divided businesses targeting the middle class into experience-type entertainment places (e.g., golf, coffee and tea, and cultural shows) and stimulant entertainment places (e.g., nightclubs and bars).

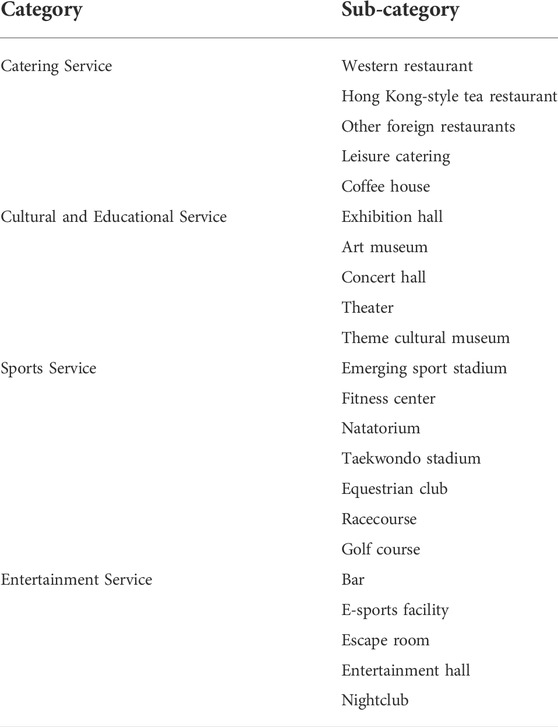

The above research has shown that the new middle class is drawn to medium- and high-end individual consumption with a focus on high-quality, entertaining experiences as well as cultural consumption that effectively indicates social status. Based on the classification of the point of interest (POI) data in Chengdu, this study identified four categories (and 22 sub-categories) of retail places targeting the new middle-class consumers in China: 1) catering services, 2) cultural and educational services, 3) sports services, and 4) entertainment services (Table 1).

4 Research area, data, and methods

4.1 Research area

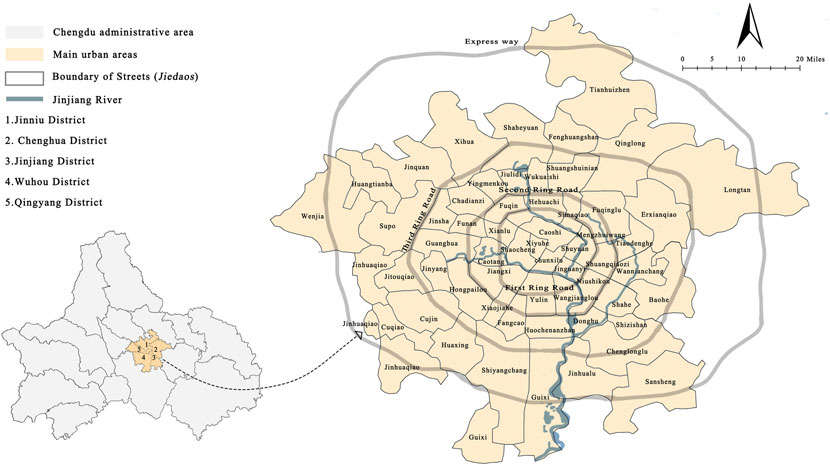

Chengdu, a major city in the west of China and the capital city of Sichuan Province, has recently begun to undergo rapid development (Yang et al., 2022). Chengdu has been a pilot city for the national strategy of “developing China’s west” since 2000. In 2013, the Belt and Road Initiative was promoted by President Xi Jinping. Cities in west China such as Chengdu started to play an increasingly important role in the development of the export-oriented economy. New state-led urban strategies have been devised, converting the city from a battleground of investments and industries to an agglomeration of talented people. Moreover, Chengdu is a transportation junction to China’s external areas and an administrative and cultural center in Western China. Located on the Chengdu Plain for over a thousand years, Chengdu is largely flat, with a warm, humid climate. The city is known for its livability, comfortability, and leisure. Following the prosperous development of its consumption culture, the 14th Party Congress of Chengdu in 2022 highlighted the city as a site planned to be transformed into a hub of international consumption. Numerous ambitious plans that followed made Chengdu a suitable site for this research. As the emerging retail industry tends to develop in dense urban areas, this study considers the five main urban areas (wu chengqu) in Chengdu, which include Qingyang District, Jinniu District, Wuhou District, Chenghua District, and Jinjiang District (Figure 1). Given that emerging consumption is still developing in Chinese cities, the sum of the corresponding retail places remains limited. Commercial gentrification is expected to become a prominent feature in areas larger than individual communities, at least. The study thus chooses Street (jiedao), for which the geographical area is larger than that of a community but smaller than that of an urban district, as a basic unit for the analysis of commercial gentrification.

4.2 Data

We used the POI data, the second-hand housing prices of Chengdu’s main urban area in 2010, 2015, and 2020, and government policies as the study’s main data.1 We employed 184,838, 314,508, and 724,536 POIs for the main urban areas of Chengdu in 2010, 2015, and 2020, respectively. The POI data were screened, cleaned, and classified as one of the abovementioned four classes. Ultimately, we used 2,054, 5,360, and 10,477 POIs for the four categories of retail industries in 2010, 2015, and 2020, respectively.

4.3 Methods

We combined three methods to analyze commercial gentrification in Chengdu. First, We selected Kernel density estimation (KDE) to detect the spatial distribution of the four categories of new retail places. Kernel density is a non-parametric method of estimation, which does not assume the potential structure of the variable, but rather estimates the probability density function based on the data of a random variable (Parzen, 1962). It fits into the exploration of the distribution of a finite data sample in an area. Second, the changing location quotient (LQ) of the new retail places in a Street was used to measure the developmental level of commercial gentrification. The development level of a segment of retail industries in a Street is impacted by the Street scale and the scale of commercial land use in the Street. The LQ indicator can reduce the impact of regional scale and can be used to calculate the relative level of specialization with reference to the average level of the city. Finally, industrial distribution in different sections of the city tends not to follow the rules of normal distribution due to the aggregation effect of industries, the bias of some industries to particular geographical positions, and the influence of urban planning on the display of urban industries. Accordingly, we selected Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient to assess the connections between commercial gentrification and urban spatial change.

4.3.1 Kernel density estimation

The KDE of the new retail places from 2010 to 2020 was made in ArcGIS (version 10.6). The density maps of traditional retail places were also constructed for the purpose of comparison. The study defines 1 km × 1 km square, roughly equal to the size of a daily living area, as the bandwidth of the kernel density estimation. In order to facilitate comparison, we have unified the classification of kernel density levels over the 3 years. The formula is as follows:

where

4.3.2 LQ analysis

We calculated the LQs of the four retail industry categories for the 58 Streets. Each Street gains five LQ values for 2010, 2015, 2020, and the changes every 5 years. The changing index marks the developmental level of commercial gentrification during the 5 years. The calculation formula is as follows:

Where i stands for the index of a Street,

4.3.3 Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient analysis

The five major Street-level functions correlated with commercial gentrification are the development level of knowledge-intensive industries, the development level of manufacturing, the development level of ordinary companies and enterprises, the degree of retail mixing, and housing price. Knowledge-intensive industries include financial, high-tech, cultural, and creative industries. The first three indicators were calculated through LQ, while housing price was denoted by the growth rate. Using Spearman’s correlation coefficient, three models for 2010, 2020, and 2010–2020 were established to explain the correlations between commercial gentrification and the five variables. Spearman’s correlation coefficient (

Where

5 Results

5.1 The distribution of new retail places representing commercial gentrification

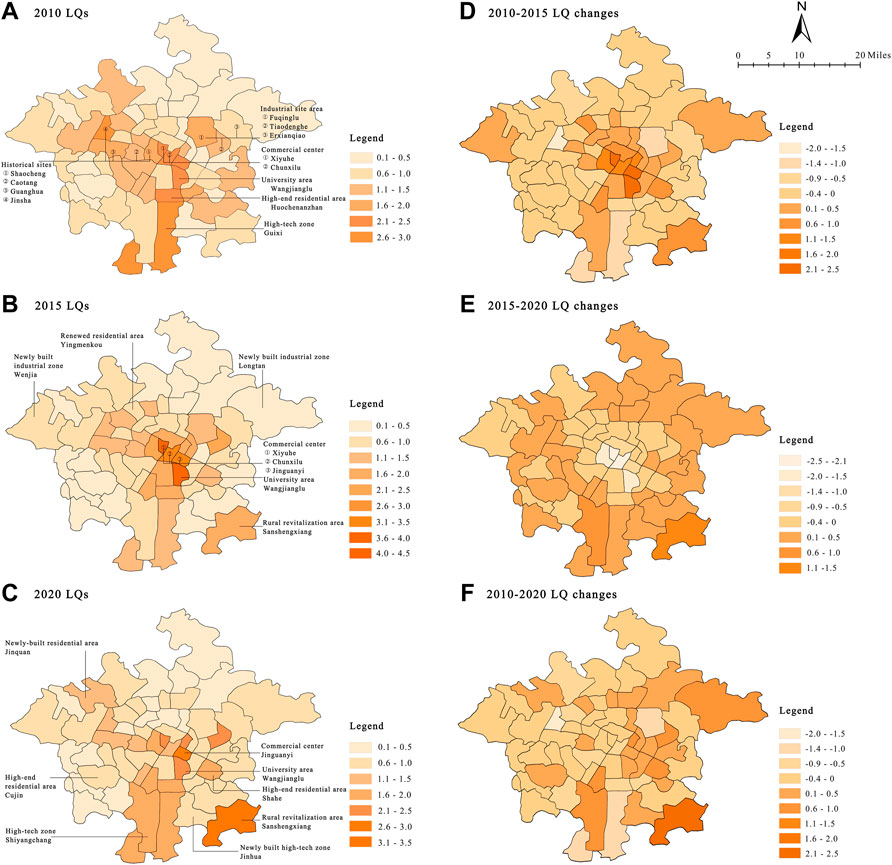

5.1.1 From monocentric to polycentric structure

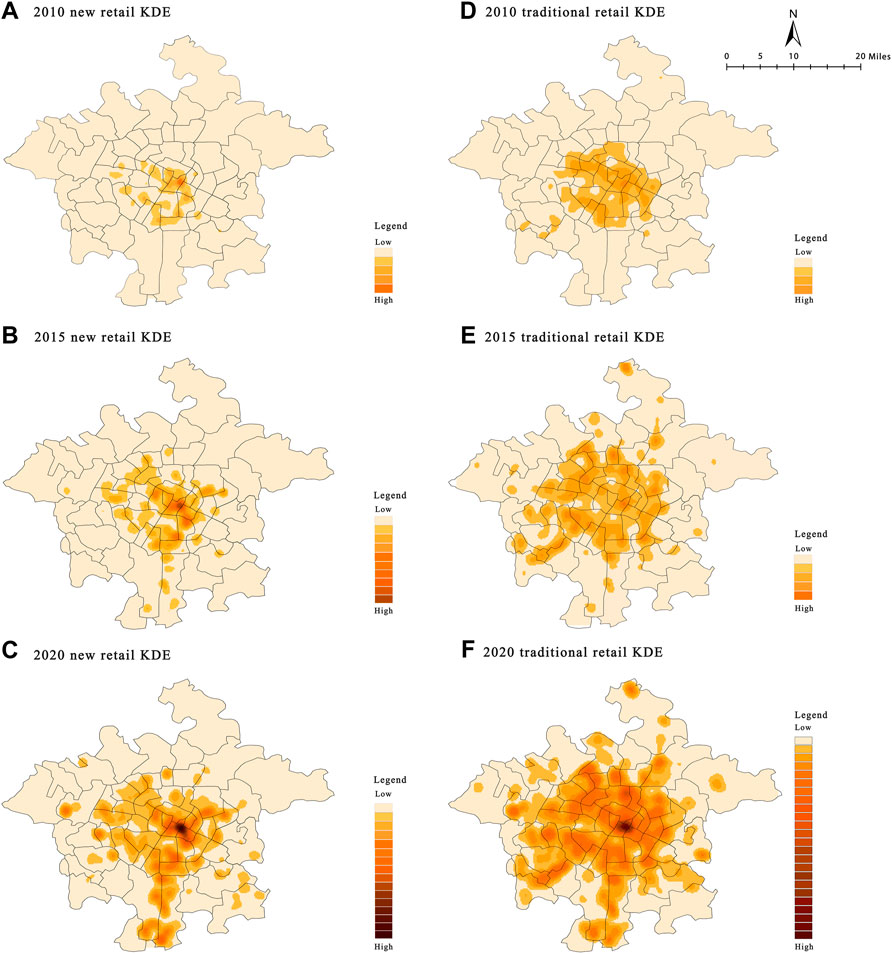

Figure 2 shows the kernel density maps of places for the new and traditional consumption in 2010, 2015, and 2020 in the main urban areas of Chengdu. The distribution of these new retail places has changed from a monocentric to a polycentric structure from 2010 to 2020. The difference in densities between the core and the surrounding areas has greatly enlarged. In 2010, spaces for emerging consumption formed only one dense area of Chunxilu Street, where the city-level commercial center is located. In 2015, high-density areas developed outside the center. The Chunxilu core was expanded in scale, and its density was further enhanced. From 2015 to 2020, the number of new consumption cores and the unevenness of density distribution continued to enlarge. Further still, the new consumption cores in 2020 have overlapped with some of the traditional commercial centers, such as those of Chunxilu, Shaocheng, Jinsha, Shuangnan, Shupo, Jinyang, Donghu, and Fuqinglu Streets (Figures 2C, F). However, the density levels could be divergent between the overlapped two centers, such as those in Yulin, Donghu, Jinsha, Shuangnan, and Jiulidi Streets. Furthermore, a few new centers, namely Sansheng, Tiaodenghe, and Wangjianglu Streets, have grown outside of the traditional ones.

5.1.2 Diffusion from the center to inner suburbs and high-tech zone

From 2010 to 2020, the new retailing spread from the inner city to the inner suburbs and grew rapidly in the south part of the city, where the high-tech south zone is located. The high-tech south zone is affiliated with the Chengdu High-Tech Industrial Development Zone (CHTIDZ), which was designated by the national government in 1990. From 2010 to 2020, the development of the high-tech south zone reached a high point. In 2016, the Ministry of Science and Technology ranked the comprehensive strength of the CHTIDZ the third of the national zones, right below Zhongguancun Science Park in Beijing and ZhangJiang high-tech Park in Shanghai. In comparison, traditional retail industries experienced rapid development in various directions of inner suburbs and outskirts during the decade, with a comparative advantage over the new retail industries in the north and southwest suburbs.

5.2 The development characteristics of commercial gentrification

5.2.1 A growing total number but a stable proportion

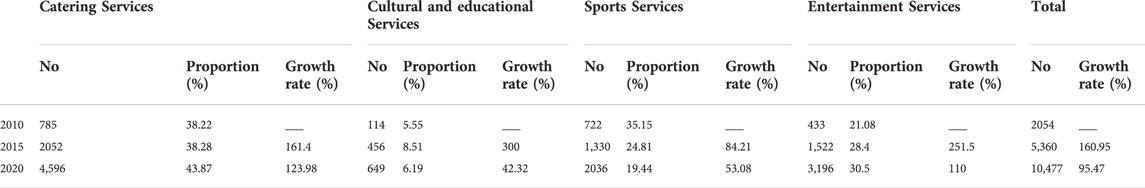

The total number of the four categories of retail places grew significantly between 2010 and 2020, rising from 2,054 in 2010 to 5,360 in 2015 and 10,477 in 2020. Despite this growth, however, the proportion of these places for emerging consumption across the overall retail places remained constant, which accounted for only 2.2%, 3.0%, and 2.8% in 2010, 2015, and 2020, respectively. The result indicates that the retail industries for emerging consumption were developing at a steady pace in line with the rest of the Chengdu retail industries.

5.2.2 Rapid development of spaces for entertainment service consumption

Among the four classes of emerging consumption, catering services constituted the dominant type in Chengdu, accounting for about 40% of the total from 2010 to 2020 (Table 2). In terms of growth speed, however, entertainment service consumption grew the fastest from 2010 to 2020 with a sustained, steady pace, followed by catering consumption with the second-fastest growth rate. The proportion of sports service consumption was 35.15% in 2010, though this figure declined over the course of the next decade, ultimately falling below that of entertainment service consumption in 2020. In 2020, places for cultural and educational services were the least prominent in Chengdu, with the figure declining despite some initial growth.

5.2.3 Transition from centripetal development to centrifugal development

(1) 2010–2015

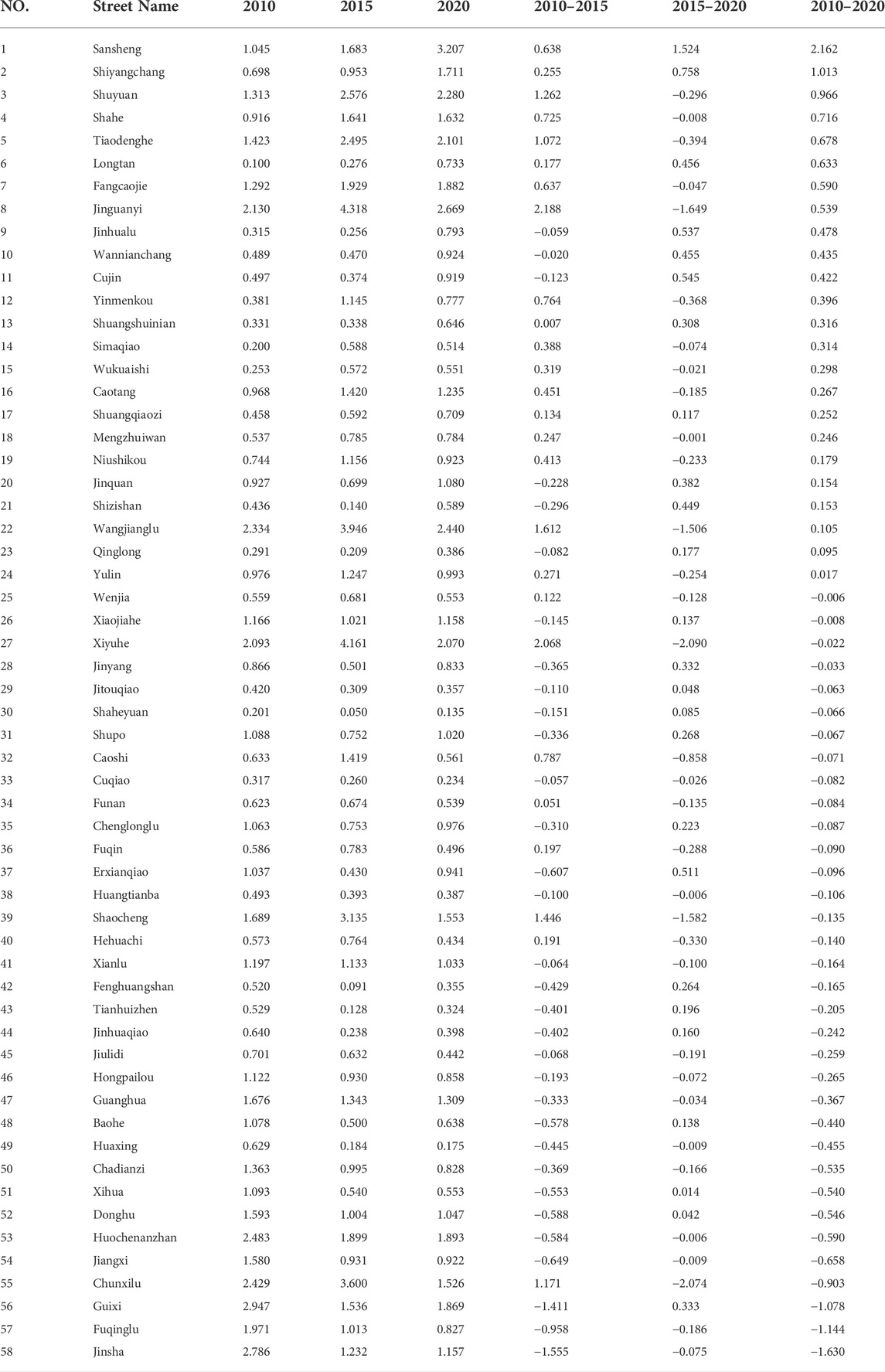

Table 3 shows the LQs of the new retail places at the Street level. Figure 3 maps the geography of commercial gentrification from 2010 to 2020. In 2010, Streets with high levels of new retail industries emerged in different parts of the city, including Chunxilu (with the commercial center) in the middle, Jinsha (with historical sites) in the west, Fuqinglu (with industrial sites) in the east and Guixi (in the high-tech zone) in the South. Generally, the west of the city affiliated with Qinqyang district (see Figure 1) was at the head of the development during the 2000s of the new retail industries in 2010. Qingyang District is famous for its abundant educational and cultural resources. It has a strong advantage in urban renewal and tourism development during the 2000s, as it hosts numerous important historical and cultural sites, such as Wide and Narrow Alley, the Du Fu Thatched Cottage, Qingyang Temple, Huanhuaxi Park, and the Jinsha archaeological site.

From 2010 to 2015, Streets in the central areas witnessed a rapid increase in the LQs of the places for emerging consumption. The condition could be attributed to the disinvestment of traditional retail sectors and then the initiation of commercial regeneration by the district government in the city center at this stage. In the Outline of the Twelfth Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development of Jinjiang District (2011–2015), a plan of industrial agglomeration in the city core was made, positioning Chunxilu Street as a business and trade agglomeration area, Jinguanyi Street as a business, cultural and leisure industry agglomeration area, and the eastward Niushikou as a financial services agglomeration area and Shahe Streets as an international business and commerce agglomeration area. The city center regeneration was formally set off. The iconic spaces for consumption, such as International Financial Square, Taikoo Li, and Lan Kwai Fong in Jinguanyi Street, were all developed by Hongkong-based developers at this stage.

Shaocheng historical area on the west side of the city center and Wangjianglu on the southeast side were also developing fast from 2010 to 2015. Located in Shaocheng Street, a historic area called Wide and Narrow Alleys experienced commercial redevelopment in 2008. The 12th Five-Year Plan of Qingyang District of Chengdu (2011–2015) positioned Shaocheng Street to advance high-end financial and commercial services, which generated new opportunities for Shaocheng in the growth of offices and consumption spaces. The remarkable development of Wangjianglu, on the other hand, took advantage of the environmental governance of Jinjiang River, the development of riverside leisure industries, and the regeneration of university areas.

Finally, in 2015, an area with concentrated places for emerging consumption took shape on the belt of Xiyuhe, Chunxilu, Jinguanyi, and Wangjianglu Streets, reversing the westward trend of commercial gentrification and pushing the east toward greater development. The concentration of the new retail industries in the southern CHTIDZ (Guixi Street) was slightly slowed down during the 5 years as a result of the comprehensive improvement of various types of retail industries in the southern high-tech zone. Sansheng Street (previously Sansheng Township), an area representative of rural revitalization in Chengdu, achieved early development in 2015, exhibiting fast growth in emerging consumption.

(2) 2015–2020

From 2015 to 2020, the advantage of the city center, especially Shaocheng, Chunxilu, Xiyuhe, and Jinguangyu Streets, in developing new retail industries was weakened, although these Streets still had agglomeration degree higher than the average level of the city stemming from LQs in 2020. The agglomeration degree for Chunxilu Street, the city-level commercial center, declined from 3.6 in 2015 to 1.5 in 2020. This was likely due to the fact that, with the commercial revitalization of the city center, the scale of the traditional retail industry grew substantially, and the proportion of emerging retail places declined.

On the contrary, the inner suburbs and urban peripheries began to lead the advancement of commercial gentrification, with high growth rates most evident around Shiyangchang Street in the high-tech zone, two newly built residential areas of Cujin and Jinhualu Streets and Sansheng Street. Shiyangchang Street was a demonstration area of creative industries designated by the government in the Chengdu High-tech Zone Innovation and Entrepreneurship Development Plan (2016–2020). In addition, Chengdu’s rural revitalization strategy is another policy that has had an important impact on commercial gentrification. Sansheng Street is a showcase of rural tourism in Chengdu. The first plan was made in 2003, focusing on the development of traditionally rural tourist industries. Later, foreign catering, cultural, and leisure industries increasingly assembled here and made Sansheng into an era of rural gentrification. In 2016, following the concept of building Chengdu as “a pilot of Park City” put forward by President Xi Jinping, Sansheng welcomed a new stage of development in ecological tourism. In 2020, the top-three Streets in Chengdu in terms of the agglomeration of places for emerging consumption were Sanshengxiang, Jinguanyi, and Wangjianglu Streets.

In 2020, Chengdu’s new retail places presented two developmental belts. One runs from the west to the southeast, and the other from the center to the south. Generally, from 2010 to 2020, the geography of commercial gentrification showed a trend of multi-directional development. The fast-growing Streets were located in different areas of the city, with the most concentrated being in the southeast of the city center. The city center, finally, has entered into a period of slow development.

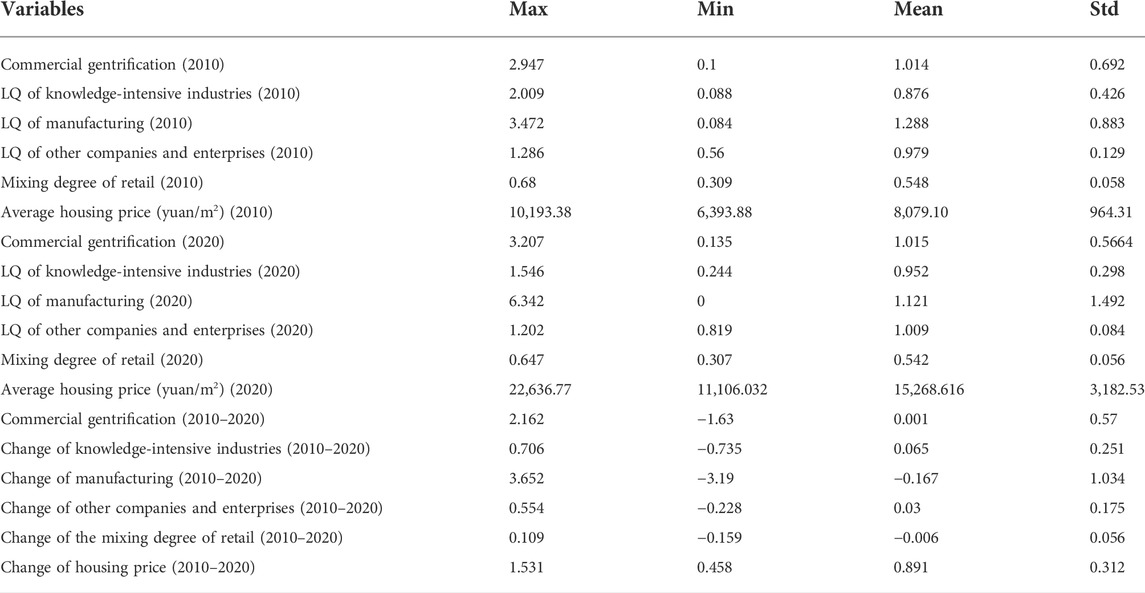

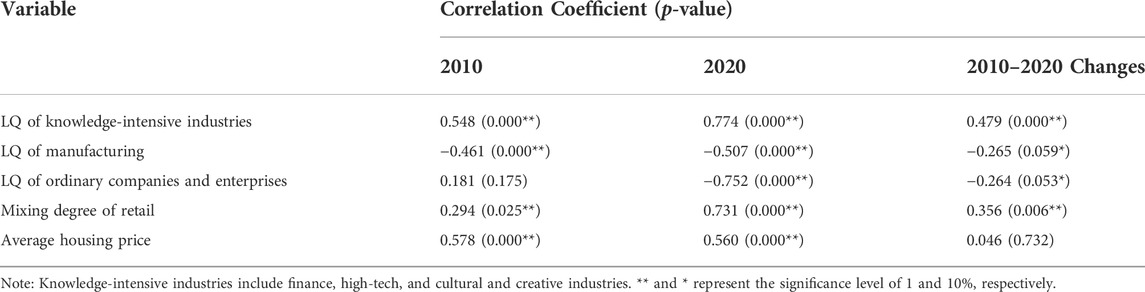

5.3 Correlations between commercial gentrification and urban spatial change

To determine the correlations between commercial gentrification and urban spatial evolution, the study relies on five sets of indicators to describe the spatial attributes of a Street in the main urban areas: LQ of knowledge-intensive industries, LQ of manufacturing, LQ of ordinary companies and enterprises, mixing degree of retail, average housing price. Three variables were assigned for each indicator, indicating the attribute of a Street in 2010, in 2020, and the value changes over the decade. Three sets of coefficients were then calculated by correlating the three sets of variables with commercial gentrification indicators separately (Table 4). Table 5 presents the results of this descriptive analysis.

TABLE 4. Spearman correlations for 2000, 2010, and 2000–2010 change against the commercial gentrification index in Chengdu (N = 58).

Commercial gentrification showed the highest correlation with the concentration of knowledge-intensive industries in 2010, 2020, or 2010–2020. On the contrary, the advancement of the four categories of new retailing did not significantly associate with the growth rate of housing prices from 2010 to 2020, although the indicators of commercial gentrification in 2010 and 2020 were both positively related to housing prices. Then, the development of the new retailing was positively correlated with the degree of retail mixing, verifying the positive effect of gentrification on local vitality. Even with the new retail places excluded, commercial gentrification was found to exert a positive effect on the diversity of retail industries, especially in the life-services field and cultural and educational fields. Finally, the development of commercial gentrification was negatively correlated with the development of manufacturing and companies not under the umbrella of the finance, high-tech, and cultural and creative industries from 2010 to 2020, but the correlation coefficients and significance are both relatively low. It is also worth noting that commercial gentrification has already been shown to elevate shop prices and repel traditional retail stores (Pratt, 2009; Liu et al., 2019).

6 Discussion

The above study sought to understand the distribution, development characteristics, and spatial correlations of commercial gentrification in a major Chinese city. Following its analysis, the three sets of distinctions of commercial gentrification in the city can be drawn.

6.1 A moderate development of commercial gentrification in Chengdu

As the number of retail places for emerging consumption is increasing at a rate of doubling every 5 years, its share across the overall retail places is relatively constant. Moreover, the new retail industries are still in a transitional phase from sports services to the stimulating of entertainment experiences; they have yet to develop into a generalized cultural-consumption phase. The results suggest that Chengdu’s consumption-oriented approach to development has not resulted in the new retail industries pushing significantly ahead of other types of retail industries. This could be a result of the limitations of the demand-side of commercial gentrification in Chengdu. As Yang (2022) has revealed that the employees in producer services took only 11.52% of all employed population in 2010 in Chengdu. Moreover, Chengdu, as the capital city of Sichuan province, has constantly attracted immigrants from the less-developed areas in the province. According to the population census, the city accommodated 4.71 million intra-provincial immigrants in 2020, while the highest proportion of these immigrants were those with secondary education. The demographic structure of the city could have hindered the rapid development of the emerging consumption industries.

6.2 Variegated geographies of commercial gentrification

Based on the KDE and LQ results, commercial gentrification in Chengdu is consistent with that in Western cities, primarily emerging in inner-city areas and, in particular, city-level commercial centers. Moreover, the multiple nuclei of new retail places seems partially consistent with traditional commercial centers. However, the density levels could be varied between the traditional and new retailing cores, and high-density new retailing can also develop in non-traditional commercial centers. Based on the developmental process of commercial gentrification from 2010 to 2020—which was significantly oriented by the government’s urban strategies—the frontiers of commercial gentrification possess mutable location attributes, including historical blocks, waterfront areas, urban commercial centers, universities, high-end residences, and rural landscapes.

The results illustrate that, although the emergence of commercial gentrification relies on traditional retail centers, its development may hinge on multiple factors. The findings further enrich our academic understanding of commercial geography. In the existing literature, the essential function of retail commerce is to meet residents’ daily material and service needs. Research in commercial geography has thus emphasized the completeness of functional levels of commercial centers, the relative locations between commercial centers and residential areas, and the extent to which the distribution of retailing optimizes consumer travel (Chai et al., 2008; Wand et al., 2013). The significance of retail industries for emerging consumption has been divorced from the daily necessities of residents to the higher level of individual demands. Most importantly, boosting emerging consumption has become the main tool with which city governors can help sustain economic vitality, which corresponds to Neil Smith’s viewpoint of gentrification as a globalized neoliberal urban strategy (Smith, 2002). Consequently, the development of new retailing would welcome greater creativity in location advantages than simply limited by service scope. Accordingly, the geographies of commercial gentrification tend to be both more variegated and selective by local governments and entrepreneurs, especially when compared to residential gentrification in Chinese cities, which usually occurs in areas with superior living resources—especially in terms of transport, the environment, and education (Huang and Yang, 2017).

6.3 Commercial gentrification as a type of industrial gentrification

As commercial gentrification may develop in different types of locations, it is nonetheless significantly correlated with the spatial evolution of knowledge-intensive industries. More notably, commercial gentrification is likely to emerge in areas already characterized by high housing prices. However, the development of commercial gentrification does not necessarily accompany the increase in housing prices. For example, between 2010 and 2015, retail sectors for emerging consumption shrunk in the commercial centers of Chunxilu, Xiyuhe, Jinsha, and Guixi Streets due to the expansion of the other retail sectors (Figure 3C). The housing prices of these Streets, nevertheless, witnessed a stabilized growth due to their location advantages. Some other Streets located at the fringe of the main urban areas, such as Baohe and Jitouqiao, saw a sharp rise in housing prices due to large-scale housing construction, but experienced a slower development of commercial gentrification in recent years. Therefore, commercial gentrification seems to have been cultivated in some high-end residential areas that also accommodated a large share of knowledge-intensive industries, but its temporal and spatial synchronization with residential gentrification was lower than that with the spatial evolution of knowledge-intensive industries.

The findings of the current study suggest broadening the scholarship of commercial gentrification to become a type of industrial gentrification in the Chinese context. As Pratt (2019, p. 1057) has claimed, “the gentrification approach was found to be partial...industrial gentrification may have a different set of dynamics.” The development of commercial gentrification exerts a greater influence on urban industrial spatial change than residential spatial upgrading and displacement. It is an indicator of the post-industrial transformation of the city. However, it is worth bearing in mind that it also generates indirectly negative effects on traditional manufacturing industries and ordinary office spaces in addition to their direct negative effects on traditional retail industries.

7 Conclusion

Through unfolding the conditions of commercial gentrification in Chengdu, the current study provides certain theoretical and practical implications for commercial gentrification and spatial planning for new retail industries. First, commercial gentrification is representative of industrial gentrification in major Chinese cities. Its developmental path and spatial effects differ from those of residential gentrification. On the one hand, commercial gentrification is characterized by variegated geographies. It is compatible with diverse locational conditions and may develop away from traditional commercial centers. On the other hand, the phenomenon accompanies urban industrial spatial change—especially post-industrial transformation. Second, the study also sheds light on the developmental characteristics of new retail industries for emerging consumption in large Chinese cities. As far as Chengdu is concerned, the development of emerging consumption remains moderate. The main types of emerging consumption are sports and entertainment (which satisfy sensory stimulation), whereas cultural consumption that meets consumers’ spiritual and knowledge demands is immature.

This study has implications for the layout of emerging commercial spaces. Since 2011, the rate of urbanization in China has been over 50%. Policies of urban renewal at the national and sub-national levels have shifted their focus to the quality improvement of built environments and the economic revitalization of old city areas. The mode of large-scale urban redevelopment—a strategy widely used by municipal governments in the 2000s, and which triggered the wave of newly-built residential gentrification—has been intensively criticized. In this case, commercial gentrification is expected to receive even more overt state intervention. Planning for emerging commercial spaces would do well to more thoroughly investigate the diversified location advantages in the city, break the spatial limits of existing commercial spaces, coordinate with financial, high-tech, and cultural industries, and minimize the unreasonable the exclusion of traditionally secondary and tertiary industries. At the same time, local governments should encourage retailing development in cultural and educational services both prudently and gradually in order to reach an active interaction between the supply and demand side of the consumer market.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

QY: conceptualization, methodology, funding acquisition, supervision, and writing–original draft. YL: formal analysis, methodology, writing—review and editing. LY: conceptualization, methodology, supervision, and writing–original draft. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51808452) and the General Program of the Sichuan Federation of Social Science Associations (No. SC20B113).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1The POIs data is obtained from the Resource and Environmental Science and Data Center in China. This data is obtained by applying the key in the Autonavi map and using Python to crawl the real-time map of the year. The housing price data come from the HomeLink Real estate data platform. HomeLink is one of the top 100 real estate brokerage enterprises and the largest second-hand real estate trading platform in China.

References

Areiza-Padilla, J. A., and Manzi-Puertas, M. A. (2021). Conspicuous consumption in emerging markets: the case of Starbucks in Colombia as a global and sustainable brand. Front. Psychol. 12, 662950. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.662950

Atkinson, R., and Bridge, G. (2004). “Introduction,” in Gentrification in a global context: the new urban colonialism. Editors R. Atkinson, and G. Bridge (London: Routledge), 1–17.

Bird, D., and Macedo, P. (2021). Seeking growth in emerging markets exploring consumer trends. (Boca Raton, FL: Polen Capital).

Bridge, G., and Dowling, R. (2001). Microgeographies of retailing and gentrification. Aust. Geogr. 32 (1), 93–107. doi:10.1080/00049180020036259

Chai, Y., Weng, G., and Shen, J. (2008). A study on commercial structure of Shanghai based on residents’ shopping behavior. Geogr. Res. (4), 897–906. doi:10.3321/j.issn:1000-0585.2008.04.018

Davidson, M., and Loretta, L. (2010). New-build gentrification: its histories, trajectories, and critical geographies. Popul. Space Place 16 (5), 395–411. doi:10.1002/psp.584

Ferm, J. (2016). Preventing the displacement of small businesses through commercial gentrification: are affordable workspace. Plan. Pract. Res. 31 (4), 402–419. doi:10.1080/02697459.2016.1198546

Gonzalez, S., and Waley, P. (2003). Traditional retail markets: the new gentrification frontier? Antipode 45 (4), 965–983. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8330.2012.01040.x

Hamnett, C. (2003). Gentrification and the middle-class remaking of inner London, 1961-2001. Urban Stud. 40 (12), 2401–2426. doi:10.1080/0042098032000136138

Huang, X., and Liu, Y. (2022). Worse life, psychological suffering, but ‘better’ housing: the post-gentrification experiences of displaced residents from Xuanwumen, Beijing. Popul. Space Place 28 (4), 2523. doi:10.1002/psp.2523

Huang, X., and Yang, Y. C. (2012). The research progress of gentrification in western countries and China with the implications for China’s urban planning. Urban Plan. Int. (02), 54–60. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1673-9493.2012.02.008

Huang, X., and Yang, Y. (2017). Urban redevelopment, gentrification and gentrifiers in post-reform inland China: a case study of Chengdu, China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 27 (1), 151–164. doi:10.1007/s11769-017-0852-3

Keatinge, B., and Deborah, G. M. (2016). A‘Bedford Falls’kind of place: neighbourhood branding and commercial revitalisation in processes of gentrification in Toronto, Ontario. Urban Stud. 53 (5), 867–883. doi:10.1177/0042098015569681

Kosta, E. B. (2019). Commercial gentrification indexes: using business directories to map urban change at the street level. City Community 18 (4), 1101–1122. doi:10.1111/cico.12468

Lees, L., Shin, H. B., and López-Morales, E. (2016). Planetary gentrification. Cambridge, Malden, MA: Polity Press.

Ley, D. (1996). The new middle class and the remaking of the central city. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Li, C. (2010). Introduction: The rise of the middle class in the middle kingdom. in Li, Chen (Ed.), China's Emerging Middle Class: Beyond Economic Transformation, 3–31. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Liu, B., and Chen, Z. N. P. (2018). Power, capital and space-production of urban consumption space based on the transformation of historical street area: a case study of sino-ocean Taikoo Li in Chengdu. Urban Plan. Int. 33 (1), 75–80. doi:10.22217/upi.2016.265

Liu, F., Zhu, X., Li, J., and Huang, Q. (2019). Progress of gentrification research in China: a bibliometric review. Sustainability 11 (2), 367–395. doi:10.3390/su11020367

Martinez, G. P. (2016). Authenticity as a challenge in the transformation of Beijing’s urban heritage: the commercial gentrification of the Guozijian Historic Area. Cities 59, 48–56. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2016.05.026

Meltzer, R. (2016). Gentrification and small business: threat or opportunity? Cityscape 18 (3), 57–86. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26328273.

Mermet, A. C. (2017). Global retail capital and the city: towards an intensification of gentrification. Urban Geogr. 38 (8), 1158–1181. doi:10.1080/02723638.2016.1200328

Parzen, E. (1962). On estimation of a probability density function and mode. Ann. Math. Stat. 33 (3), 1065–1076. doi:10.1214/aoms/1177704472

Pastak, I., Eneli, K., Tiit, T., Reinout, K., and Maarten, V. H. (2019). Commercial gentrification in post-industrial neighbourhoods: a dynamic view from an entrepreneur’s perspective. Tijds. Econ. Soc. Geog. 110 (5), 588–604. doi:10.1111/tesg.12377

Pratt, A. (2009). Urban regeneration: From the arts ‘Feel good’ factor to the cultural economy: a case study of hoxton, London. Urban Stud. 46 (5/6), 1041–1061. doi:10.1177/0042098009103854

Sakzlolu, B., and Lees, L. (2020). Commercial gentrification, ethnicity, and social mixedness: the case of javastraat, indische buurt, amsterdam. City Community 19 (4), 870–889. doi:10.1111/cico.12451

Smith, N. (2002). New globalism, new urbanism: gentrification as global urban strategy. Antipode 34 (3), 427–450. doi:10.1111/1467-8330.00249

Smith, N. (1996). The new urban frontier: Gentrification and the revanchist city. New York: Rutledge.

Song, W. X., Sun, J., Chen, Y. R., Yin, S. G., and Cheng, P. Y. (2020). Commercial gentrification in the inner city of Nanjing, China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 75 (2), 426–442. doi:10.11821/dlxb202002015

Sun, J., and Song, W. X. (2021). Literature review of foreign research on commercial gentrification and the enlightenment for Chinese studies. World Reg. Stud. 30 (5), 1096–1105. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1004-9479.2021.05.2019592

Sun, J., Zhu, X. G., Song, W. X., and Ma, G. Q. (2018). Commercial gentrification driven by cultural consumption in neighborhoods around university campuses: a case study of the original campuses of nanjing university and angina normal university. Urban Plan. 42 (07), 25–32. doi:10.11819/cpr20180705a

Sun, S. J., and Wang, J. Y. (2021). Distributional characteristics and influencing factors of invisible consumption space: a case study of Nanjing old city. Urban Plan. 261 (1), 97–103. doi:10.16361/j.upf.202100012

Tomba, L. (2004). Creating an urban middle class: social engineering in Beijing. China J. 51, 1–26. doi:10.2307/3182144

Wang, D., Duan, W., and Ma, L. (2013). Spatial impact analysis on the development of large business center—The case of wujiaochang area in shangha. Urban Plan. Forum 207 (2), 79–86. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1000-3363.2013

Wang, J., and Lau, S. Y. (2009). Gentrification and Shanghai’s new middle-class: another reflection on the cultural consumption thesis. Cities 26 (2), 57–66. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2009.01.004

Wang, L., Qiu, S., and Liao, S. W. (2019). Gentrification of the surrounding area of creative industry cluster: an empirical study based on Shanghai cases. Morden Urban Res. (02), 69–77. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1009-6000.2019.02.010

Wang, W. H. (2011). Commercial gentrification and entrepreneurial governance in shanghai: a case study of taikang road creative cluster. Urban Policy Res. 29 (4), 363–380. doi:10.1080/08111146.2011.598226

Wang, X. Z., and Gao, L. (2008). Gentrification and the spatial structure of recreational places in big cities. Hum. Geogr. 23 (2), 49–55. doi:10.13959/j.issn.1003-2398.2008.02.005

Xiang, J. Y., Luo, Z. D., Zhang, J. Y., and Cheng, L. (2021). Research on the distribution characteristics of “net celebrity space” in the mobile internet era: A case study in main area of Hangzhou, China. Mod. Urban Res. 36 (9), 20–27. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1009-6000.2021.09.002

Xu, Y., Zhang, M., and Xiao, H. (2021). New urban-rural connection brought by food consumption: a case study of organic food and organic farm. Mod. Urban Res. 36 (9), 2–10. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1009-6000.2021.09.001

Yang, L., Chau, K. W., and Chu, X. (2019). Accessibility-based premiums and proximity-induced discounts stemming from bus rapid transit in China: empirical evidence and policy implications. Sustain. Cities Soc. 48, 101561. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2019.101561

Yang, L., Chau, K. W., and Wang, X. (2019). Are low-end housing purchasers more willing to pay for access to public services? Evidence from China. Res. Transp. Econ. 76, 100734. doi:10.1016/j.retrec.2019.06.001

Yang, L., Liang, Y., He, B., Lu, Y., and Gou, Z. (2022). COVID-19 effects on property markets: the pandemic decreases the implicit price of metro accessibility. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 125, 104528. doi:10.1016/j.tust.2022.104528

Yang, Q. (2022). “Gentrification in Chinese cities,” in Urban sustainability (Singapore: Springer). doi:10.1007/978-981-19-2286-2_5

Yang, Q., and Zhou, M. (2018). Interpreting gentrification in Chengdu in the post-socialist transition of China: a sociocultural perspective. Geoforum 93, 120–132. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.05.014

Yin, X. (2005). New Trends of leisure consumption in China. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 26 (1), 175–182. doi:10.1007/s10834-004-1419-x

Yu, F. (2005). The Change and characteristics of China's middle-class consumer culture since the end of the 19th century. Acad. Res. 2005 (7), 13–19. doi:10.3969/j.issn

Zhou, K., Zhang, H. T., Xia, Y, N., and Liu, C. (2021). New urban consumption space shaped by social media: a case study of the geo-tagging places of changsha on xiaohongshu. Mod. Urban Res. 36 (9), 11–19. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1009-6000.2021.09.003

Zhu, D. (2020). The new middle class and the new consumption: Class structure transition and lifestyle changes against the background of internet development. Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press.

Zukin, S. (2008). Consuming authenticity: from outposts of difference to means of exclusion. Cult. Stud. 22 (5), 724–748. doi:10.1080/09502380802245985

Zukin, S. (1982). Loft living: culture and capital in urban change. Baltimore: The Johns Hopskins University Press.

Keywords: commercial gentrification, space for emerging consumption, knowledge-intensive industry, development characteristic, residential gentrification, spatial correlation, Chengdu, China

Citation: Yang Q, Liu Y and Yang L (2022) Commercial gentrification in China and its distribution, development, and correlates: The case of Chengdu. Front. Environ. Sci. 10:992092. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.992092

Received: 12 July 2022; Accepted: 01 August 2022;

Published: 30 August 2022.

Edited by:

Jianhong Xia, Curtin University, AustraliaCopyright © 2022 Yang, Liu and Yang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Linchuan Yang, eWFuZ2xjMDEyNUBzd2p0dS5lZHUuY24=

Qinran Yang

Qinran Yang Yang Liu

Yang Liu Linchuan Yang

Linchuan Yang