95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Environ. Sci. , 11 November 2022

Sec. Atmosphere and Climate

Volume 10 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2022.973900

Hydrothermal fluctuation is the major driving factor affecting greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in wetlands, but how wetland drying regulates the temperature dependence of GHG emissions remains uncertain. An experimental incubation was carried out to study the interaction effects of temperature (5, 10, 15, 20°C) and moisture (40%, 60%, 100% WHC) on soil GHG emissions in a karst wetland. The results showed that: 1) the cumulative CO2 and N2O emissions and global warming potential (GWP) increased with increasing temperature but decreased with soil drying. 2) There was a decreasing contribution of CO2 and an increasing contribution of N2O to GWP with increasing temperature and moisture. 3) Soil CO2 and N2O emissions and GWP were positively related to urease activity and negatively related to pH, soil organic matter and catalase. Soil CH4 emissions were positively related to soil microbial biomass C and N. The hydrothermal changes, soil properties and their interaction explained 26.86%, 9.46% and 49.61% of the variation in GWP. Our results indicate that hydrothermal fluctuation has a significant effect on total GHG emissions by regulating soil properties.

Wetlands cover 5%–8% of the global landscape (Fennessy, 2014) but account for approximately 15% of the terrestrial organic carbon stock (Han et al., 2013), which plays a critical role in regulating global carbon cycling and climatic change (Xiong et al., 2015; Salimi et al., 2021). Meanwhile, wetlands are a large source of CH4 and N2O (Sovik et al., 2006; Kayranli et al., 2010), in which global warming potential (GWP) is 28 and 298 times higher, respectively, than CO2 on a 100-year time scale (Wang et al., 2021). Although many factors have been determined to affect wetland greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, the soil temperature and water content are confirmed to be the two major factors influencing GHG emissions (Toczydlowski et al., 2020; Docherty and Thomas, 2021). Climate change can alter wetland ecosystem biogeochemistry and affect gas emissions by increasing temperature and changing hydrological patterns (Salimi et al., 2021). Therefore, quantifying the response of GHG emissions to soil temperature and water content changes is critical to predicting the potential effect of wetlands on global warming.

Many studies have reported that there is an increasing trend of GHG efflux as the temperature and moisture increase in a certain range (Yang et al., 2013; Yvon-Durocher et al., 2014; Toczydlowski et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2020). For instance, CO2 and CH4 emissions could increase approximately 3 times for every 10°C increase in temperature (McKenzie et al., 1998); elevating temperature significantly promotes soil CH4 and N2O emissions from wetlands (Liu et al., 2017; Toczydlowski et al., 2020). Higher temperatures can promote soil organic matter decomposition (Yang et al., 2013), microbial biomasses (Baldock et al., 2012), C cycle-related enzyme activities (Bell et al., 2010), and chemical reaction rates (Reichstein et al., 2013), thus enhancing greenhouse gas emissions. The moisture effect on wetland GHG emissions is dependent on the aerobic and anaerobic situations (Salimi et al., 2021). CO2 emissions are often higher in unsaturated soils, while flooding causes a reduction in CO2 and an increase in CH4 emissions in wetlands (Yang et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2020). Wetland moisture is crucial to the substrate supply for soil microorganisms and oxygen diffusivity (Salimi et al., 2021). On the one hand, unsaturated moisture is beneficial for forming an aerobic environment and providing more organic substrates for aerobic microorganisms, which in turn facilitates soil C and N mineralization and CH4 oxidation (Yang et al., 2013; Henneberg et al., 2016; Zhang T. et al., 2020). On the other hand, excessive moisture prevents the proliferation of O2 and further limits aerobic microbial activity, resulting in a decrease in CO2 emissions (Martikainen et al., 1993; Yang et al., 2013). Furthermore, excessive moisture promotes anaerobic microsites and therefore promotes CH4 emissions (Kang et al., 2012) and N2O efflux through denitrification (Dobbie and Smith, 2001). However, some studies have reported that higher temperatures have a small effect on CO2 emissions (Liu et al., 2017) or reduce CH4 emissions when wetlands are constrained by the soil water content (Houweling et al., 2000; Kang et al., 2012), while increasing moisture decreases N2O emissions (Zhang, et al., 2020). These different results reveal that the response of wetland GHG emissions to soil temperature and water content changes remains inconclusive.

Wetlands are normally distributed in ecotones between aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems, leading to inevitable hydrothermal fluctuations in temperature and moisture (Salimi et al., 2021). Although many field studies have been performed on the factors affecting soil GHG flux rates in wetlands globally, it is difficult to determine a single parameter because other factors usually covary or interact (Zhao et al., 2020). Laboratory incubation has proven to be a feasible approach for overcoming confounding covariations. Many studies have researched the potential mechanisms of wetland GHG emissions under various temperature and moisture conditions (Liu et al., 2017; Zhao et al., 2020), whereas only a few studies have focused on the interactions of temperature and moisture (Gao et al., 2011; Toczydlowski et al., 2020). Moreover, there are large seasonal variations in hydrological cycling due to human impacts such as artificial drainage (Chen et al., 2018) and climate change, such as temperature increases and precipitation reductions (Wu et al., 2017; Salimi et al., 2021), which in turn cause long-term drier rather than wetter conditions in many wetlands (Zhao et al., 2020). Therefore, it is critical to elucidating the responses of GHG emissions to unsaturated moisture conditions combined with temperature.

Guizhou Province, as the center of karst landform in southwest China (Wang L. et al., 2018), is one of the largest and continuous typical karst region in China (Liu et al., 2022). Its exposed karst land has caused soil degradation, soil erosion and a sharp decline in soil productivity. It also aggravates the problems of drought and flood. As one of the important sources of GHG emissions in plateau regions, wetland ecosystems are extremely vulnerable and particularly sensitive to global warming and related changes in temperature and precipitation (Yang et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2022). Study has shown that the coverage rate of karst wetland ecosystem is increasing at an average rate of about 5% per decade (Fan et al., 2015). Therefore, the study on the impact of temperature and moisture changes on GHG emissions in karst wetland ecosystems has important guiding significance for future global climate change.

Therefore, we conducted an incubation experiment, made up of four temperature gradients and three moisture gradients, in the karst wetland of the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau. The objectives of the present study were 1) to determine the interactions of temperature and soil drying on CO2, CH4 and N2O emissions, 2) to compare the contribution of three greenhouse gases to global warming potential (GWP), and 3) to explore the relationship between soil factors and GHG emissions.

Incubation samples were collected at a depth of 0–10 cm from calcareous soil located in Huaxi National Urban Wetland Park (26°29'∼26°36′N, 106°27'∼106°52′E) in Guiyang City, which is in a typical karst wetland on the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau. Each sample was freeze-dried and passed through a 2 mm sieve. We conducted a 3 × 4 factorial design with two factors: a temperature gradient of 5 (T5), 10 (T10), 15 (T15), and 20°C (T20) and a moisture gradient of 40% (W40), 60% (W60), and 100% (W100) water-holding capacity (WHC). There were 12 treatment combinations with three replicates in each treatment.

Before incubation, 100 g freeze-dried soil was put into a 250 ml plastic jar, and then deionized moisture was added to adjust the required soil moisture content. Then, the jars were placed in four constant temperature incubators (LRH-100CA, Shanghai Yiheng Co. Ltd, China) at a gradient of 5, 10, 15 and 20°C, respectively. The jars were covered with perforated plastic film to facilitate gas flow. During the cultivation period, a weighing method was used to maintain constant moisture by adding deionized water every 5 days.

The jars were flushed with fresh air for 20 min to clear the gas accumulated in the culture flask before taking the gas sample and were then sealed the jars via a cap with a three-way valve. The gas samples were collected at 0 and 30 min using a 10 ml syringe after 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 10, 15, 20, 25 and 30 days of incubation.

Gas samples were using gas chromatography (GC-2014, Shimadzu, Japan). The contents of CH4 and CO2 were determined by the front detector FID (hydrogen flame ion detector) at 200°C. N2O concentration was determined by an ECD (electron capture detector) at 300°C and 99.99% high purity nitrogen as the carrier gas. The GHG flux rate was calculated following (Junna et al., 2014).

where F is the instantaneous rate of greenhouse gas, ρ is the gas density (kg m−3),

The global warming potential (GWP, mg kg−1, CO2 equivalent) was calculated following the formulae of (Wang et al., 2021).

Two-way ANOVA was used to test the effects of temperature, moisture and their interactions on GHG emissions and GWP. The LSD test was used to test the difference among all treatments. Pearson correlation was used to analyse the correlation between greenhouse gas emissions and soil factors. Statistical analysis was conducted by using IBM SPSS Statistics 26 and Origin Pro 2021. Variance decomposition analysis was implemented by the varpart function in the “Vegan” package of RStudio. All analyses were defined as significant at the 0.05 level.

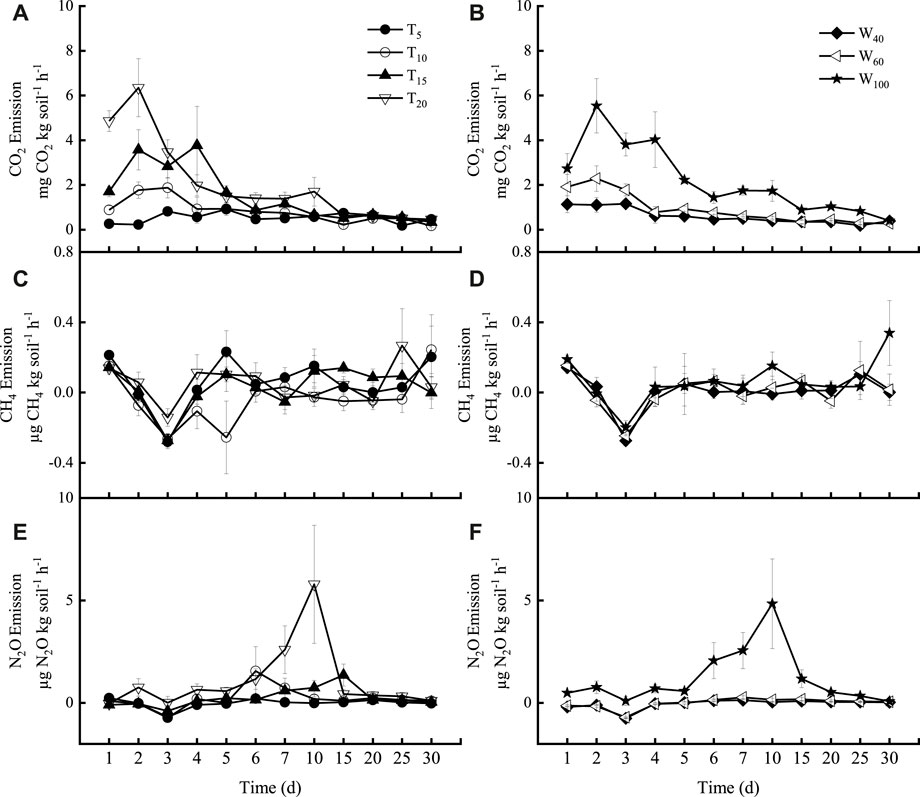

The CO2, CH4, and N2O emission rates of all treatments showed similar variations with incubation time (Figure 1). The CO2 emission rate reached a maximum before the third day and then decreased gradually to stable in both the temperature and moisture treatments (Figures 1A,B). The CH4 emission rate was lowest on the third day and then increased to stable in both the temperature and moisture treatments (Figures 1C,D). The N2O emission rate of each treatment showed small fluctuations during the whole incubation period, except for a peak value in T20 and W100 on the 10th day (Figures 1E,F).

FIGURE 1. Temporal changes in soil CO2, CH4 and N2O emission rates. The error bars show standard errors: n = 9 and 12 for temperature and WHC, respectively.

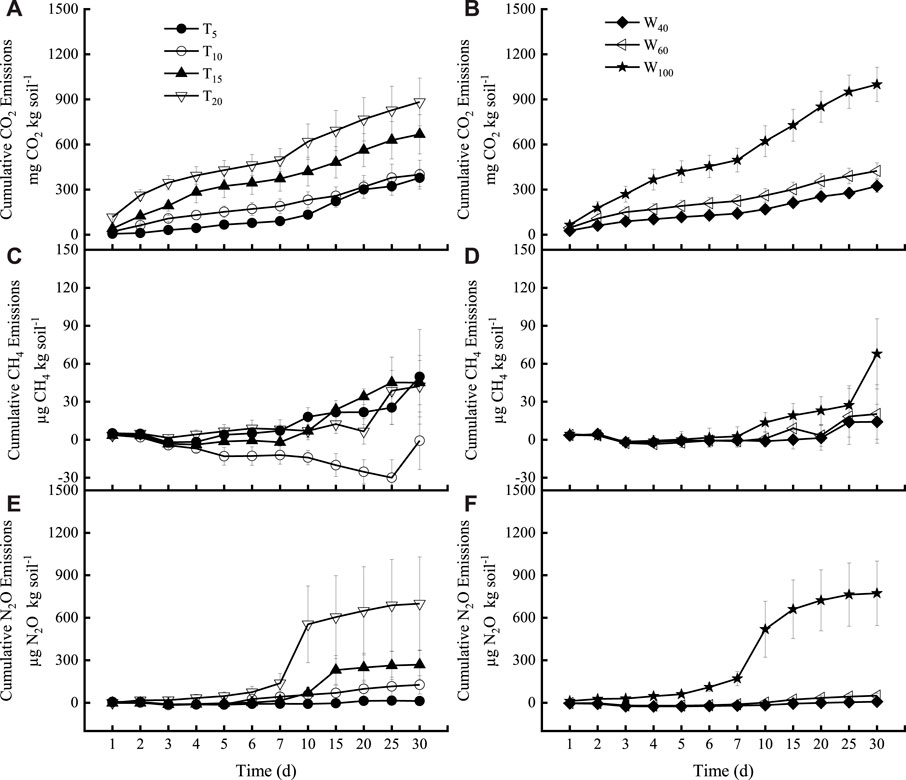

Soil CO2 emissions increased with increasing temperature (Figure 2A), increasing by 5.6% (T10), 76% (T15, p < 0.05), and 133% (T20, p < 0.05) compared to T5 (Figure 2A and Table 1). The soil N2O emissions of T15 and T20 showed significant increases compared to T5 (Figure 2E and Table 1). Soil CH4 emissions were not significantly affected by temperature (Figure 2C, p > 0.05). The soil CO2 emissions increased by 31% (W60) and 209% (W100, p < 0.05) compared to W40; soil N2O emissions showed significant increases in W100 compared to W40 (Figures 2B,F, p < 0.05). The cumulative CH4 emissions increased with increasing moisture (Figure 2D); however, there were no significant differences between treatments due to the complicated response under different temperature levels (Table 1 and Figure 3B).

FIGURE 2. Temporal changes in soil cumulative CO2, CH4 and N2O emissions. The error bars show standard errors: n = 9 and 12 for temperature and WHC, respectively.

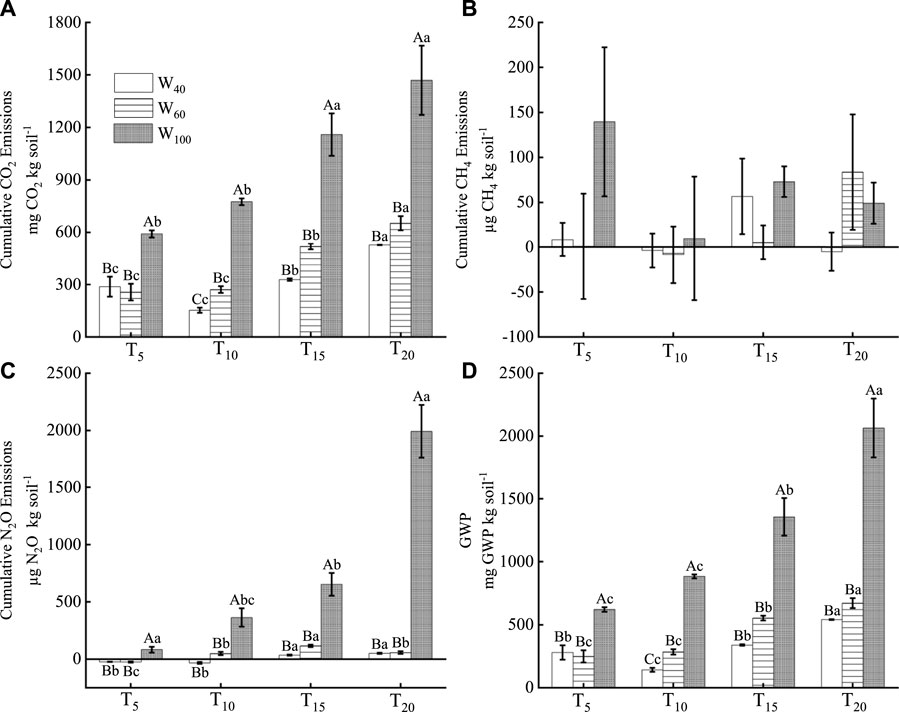

FIGURE 3. Interactions of temperature and moisture treatment on soil cumulative CO2, CH4 and N2O emissions at the end of culture. The capital letters are the differences between the same temperature and different moisture treatments, and the lowercase letters are the differences between the same moisture and different temperature treatments. The error bars show standard errors: n = 3.

The GWP increased by 14% (T10), 95% (T15, p < 0.05), and 185% (T20, p < 0.05) compared to T5 (Table 1). The GWP of W100 was significantly increased compared to that of W40 (Table 1, p < 0.05). The contribution of CO2 to GWP was more than 84.93% and decreased with temperature and moisture increases, but the contribution of N2O to GWP increased with temperature and moisture increases (Table 2). Temperature, moisture and their interactions had significant effects on CO2/GWP and N2O/GWP (Table 2, p < 0.01). There were significant effects of temperature and moisture interactions on CO2 and N2O emissions and GWP (Table 1). The CO2 and N2O emissions and GWP of W100 were significantly higher than those of W40 and W60 among the different temperature gradients, and there were significant differences in CO2 emissions and GWP between W40 and W60 under the T10 treatment (p < 0.05, Figures 3A,D).

Temperature had significant effects on SOM, but there was no interaction between temperature and moisture. Soil MBC, MBN and NH4+-N significantly decreased with increasing soil drying and temperature; in contrast, soil sucrase increased with increasing temperature and drying (Table 3, p < 0.05). Soil catalase and urease increased as the temperature (Table 3, p < 0.05) increased from 40% WHC to 60% WHC and then decreased down from 100% WHC.

Pearson correlation analysis showed that the cumulative CO2 and N2O emissions and GWP were positively related to soil moisture, temperature, and urease activity and negatively related to pH, SOM and catalase (p < 0.05, Figure 4A). The cumulative CH4 emissions were positively related to MBC and MBN (Figure 4A, p < 0.05). Variance decomposition analysis found that hydrothermal, soil properties and their interaction explained 26.86%, 9.46% and 49.61% of the variation in GWP, respectively (Figure 4B).

FIGURE 4. Pearson correlation analysis (A). The red and blue ellipses represent positive and negative correlations between GHG emissions and soil properties, respectively. The darker the colour and the flatter the graph are, the stronger the correlation is, and * represents significance (p < 0.05). (B) The variance decomposition analysis of global warming potential (GWP) influenced by soil hydrothermal factors and soil properties, in which the overlap represents the common influence and the residual represents the unexplained variation. T: temperature; W: moisture; SOM: soil organic matter; TN: total nitrogen; TP: total phosphorus; MBC: microbial biomass carbon; MBN: microbial biomass nitrogen; NH4+-N: ammonium nitrogen; NO3−-N: nitrate nitrogen, same as Table 3.

Higher temperatures significantly promoted CO2 emissions in this study (Table 1), which is in line with many previous studies (Schaufler et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2020; Toczydlowski et al., 2020). Gao et al. (2011) reported that the soil CO2 emission rate increased by 2.4–3.7 times in swamps and peat wetlands from 5 to 35°C. Increasing temperature can promote soil microbial activity and decomposition of soil organic matter by improving microbial substrate availability (Silvola et al., 1996; Inglett et al., 2012), thus increasing CO2 emissions and reducing soil SOC content (Na et al., 2011). We found that SOM, MBC and MBN significantly decreased with increasing temperature and were negatively related to CO2 emissions (Figure 4A). Previous studies also found that increasing temperature resulted in decreases in SOC (Kirschbaum, 2000; He et al., 2020), MBC and MBN (Rinnan et al., 2009; Fu et al., 2012).

Elevating temperature often leads to a higher methane efflux under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions (Inglett et al., 2012; Vilakazi et al., 2021). For example, Macdonald et al. (1998) indicated that the CH4 emission rate showed an exponential increase between 5 and 30°C. However, we found that there were no differences among the four temperature gradients due to the complicated responses under different moisture levels (Figure 3B). Temperature alters CH4 production by affecting soil organic matter, C availability, redox processes, and bacterial community changes such as methanogens abundance, composition and activity (Morrissey et al., 2014; Li et al., 2020). Li et al. (2020) indicated that high MBC and MBN contents are a potential mechanism leading to high CH4 emissions. Our study showed that CH4 emissions were positively related to MBC and MBN (Figure 4A), indicating that temperature affects CH4 emissions by regulating microbial biomass C and N.

In our study, increasing temperature significantly promoted N2O emissions, with a maximum in the T20 treatment (Table 1), which was consistent with previous studies conducted in Tibetan (Liu et al., 2017) and European wetland soils (Schaufler et al., 2010). Cui et al. (2018) found that elevating temperature increased the N2O flux rate by 147% in a northern peat wetland. Elevating temperature could stimulate the soil nitrogen mineralization rate, which in turn increases the availability of mineral nitrogen and provides a nutrient supply for nitrification and denitrification to produce N2O (Morse and Bernhardt, 2013). We found that elevating temperature significantly reduced soil NH4+-N and increased NO3−-N content (Table 3). Even with an extremely low NH4+-N content, the ammonia-oxidizing archaeal community could still use NH4+-N to produce NO3−-N (Martens-Habbena et al., 2009). Although soil was not incubated at higher temperatures in the present study, a previous study reported that the N2O emissions were higher than those at 20 °C when the temperature increased to 25 and 34°C, and high temperature promoted the expression of denitrifying genes (Wang et al., 2018).

We found that the soil CO2 emissions at 100% WHC were 3.1 times higher than those at 40% WHC (Table 1). This result is similar to (Maucieri et al., 2017), who observed that soil CO2 emissions increased by 2.7 times from 25% to 100% WHC in Australia. Soil moisture usually determines the decomposition rate of soil organic matter in wetlands (Burkett and Kusler, 2000). Generally, soil CO2 emissions are positively correlated with moisture under unsaturated moisture conditions (Silvola et al., 1996; Blodau et al., 2004). Oxygen diffusion to deep soil can increase organic matter mineralization, and CO2 production from aerobic respiration is more effective than anaerobic respiration, which in turn accelerates CO2 transport in unsaturated soil (Yang et al., 2013). In addition, soil microbes are more active when there is moisture below the soil surface, and these microbes utilize the active organic carbon matrix, which directly causes higher CO2 emissions (Chimner and Cooper, 2003). However, some studies found that moisture was negatively related to CO2 emissions under seasonal flooded conditions (Chen et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2020). The excessive increase in moisture can mitigate the diffusion and availability of O2 in soil, thus reducing CO2 emissions by limiting the activity of aerobic microbes and the decomposition of SOC (Jimenez et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2014; Khalid et al., 2019).

Soil moisture is a major factor in regulating CH4 oxidation and emission (Khalid et al., 2019). We found that higher moisture promoted CH4 emissions, which were highest at 100% WHC (Table 1). Higher moisture can reduce the oxygen concentration, which is beneficial to the anaerobic decomposition of methanogens, thus promoting CH4 production (McInerney and Helton, 2016). Instead, the CH4 emission rate may be reduced under low moisture conditions by enhancing CH4 oxidation (Maucieri et al., 2017). Moreover, soil CH4 emissions were positively correlated with MBC and MBN in this study (Figure 4A). Soil organic carbon is the carbon source and energy for generating CH4, in which microbial biomass carbon can provide a substrate for methanogens (Li et al., 2020). Many previous studies also reported that soil MBC had a highly positive correlation with CH4 emissions (Rasilo et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2019). In addition, methanotrophic bacteria have a certain demand for NH4+-N (Bodelier and Laanbroek, 2004), which can increase the activity of methanogens and reduce the activity of methane bacteria (Bodelier et al., 2012), thereby increasing methane emissions. Although moisture had no significant effect on NH4+-N content in the present study, there was a significant interaction of moisture and temperature on NH4+-N content (Table 1).

Our study found that increasing soil moisture promoted N2O emissions, with the highest emissions in the 100% WHC treatment (Figure 2F). A previous study also found that the largest N2O emissions occur at 80% and 100% water-filled porosity spaces (Ciarlo et al., 2007). Soil moisture is often positively correlated with N2O emissions (Schaufler et al., 2010), including linear (Dobbie and Smith, 2001), quadratic (Ciarlo et al., 2007) or exponential relationships (Dobbie and Smith, 2003), while a few studies have shown no obvious relationship between N2O emissions and moisture change (Krauss and Whitbeck, 2012). N2O production is the result of nitrification and denitrification with the participation of soil microorganisms (Braker and Conrad, 2011). Higher moisture can increase the soil soluble carbon content for microbes to provide sufficient C and N sources and improve the microbial nitrogen conversion rate, thus increasing N2O emissions (Wu et al., 2022). In addition, wetland N2O emissions are affected by NH4+-N content to a certain extent, which could be produced by nitrification of NH4+-N (Cui et al., 2016).

We found that soil CO2 and N2O emissions were significantly affected by temperature and moisture interactions in this study (Table 1), which was consistent with the results of black ash wetlands in this study (Toczydlowski et al., 2020). We found that soil CO2 and N2O emissions under high moisture (W100) were significantly higher than those under low moisture (W40 and W60) in all temperature treatments (Table 1; Figures 3A,C). (Rey et al., 2010) indicated that moisture had a greater effect on soil CO2 emissions than temperature under low moisture conditions (40% and 60% WHC), while temperature had a greater effect on CO2 emissions under higher moisture conditions (100% WHC). However, the temperature and moisture interaction had no significant impact on CH4 emissions in the present study (Table 1), which was inconsistent with other studies. For instance, soil temperature and moisture interactions had a significant impact on CH4 emissions in alpine marshes and peat wetlands (Gao et al., 2011). The variations may result from the differences in soil types (Tian et al., 2010), soil properties (Li et al., 2020) and soil moisture (Yang et al., 2013).

Global warming potential converts the elevating temperature effect of a certain greenhouse gas in a certain time range into equivalent CO2, which can quantitatively assess the effect of greenhouse gas on climate warming. We found that soil CO2 emissions were the main contribution of GWP (above 84.93%), followed by N2O (Table 2). A previous study reported that CO2 emissions accounted for 94–100% and 75–85% of the GWP in mineral and organic wetland soils, respectively (Bonnett et al., 2013). Huang et al. (2019) found that CO2, CH4 and N2O contributed 20%, 10% and 70% to the GWP of artificial tidal mangrove wetlands, respectively. One study even found that CH4 emissions accounted for 68% of the GWP in natural mangrove wetlands (Wang et al., 2016).

In the present study, increasing temperature significantly increased the GWP, which was 2.85 times higher in T20 than in T5 (Table 1), suggesting that the GWP has positive feedback to climate warming. Similar results were also found in other studies in which the GWP at 20°C was 2.8 times higher than that at 5 °C in Alaskan peat wetlands (Treat et al., 2014) and 2.1 times higher at 19°C than at 7°C in Tibetan alpine wetlands (Liu et al., 2017). Correlation analysis indicated that temperature and moisture affected GWP mainly by affecting soil pH, organic matter, nitrogen availability and enzyme activity (Figure 4A). Hydrothermal factors and soil properties together accounted for 85.93% of GWP variations (Figure 4B), suggesting that GWP is not only regulated by soil temperature and moisture interactions but also affected by soil chemical properties. Li et al. (2020) found that soil environmental variables account for 28%–67% of GHG emission changes in coastal wetlands. Environmental variables could explain 58.58% of the change in carbon concentration under elevated temperature conditions in paddy wetlands and natural wetlands (Furlanetto et al., 2018). Our results supported that GHG emissions are not only affected by temperature and moisture but also regulated by soil properties and enzyme activities (Salimi et al., 2021).

Increasing temperature and moisture significantly promoted CO2 and N2O emissions, and CH4 emissions increased with increasing moisture. There was a decrease in the contribution of CO2 but an increase in the contribution of N2O to the GWP with increasing temperature and moisture. The CO2 and N2O emissions and GWP were positively correlated with urease activity and negatively correlated with soil pH, SOM and catalase. Soil CH4 emissions were positively correlated with MBC and MBN. The hydrothermal changes (temperature and moisture), soil properties and their interaction explained 26.86%, 9.46% and 49.61% of the variations in GWP, respectively, suggesting that the temperature and moisture interaction had a direct effect on GHG emissions and an indirect effect by regulating soil properties.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary materials, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

YH: Data processing and analysis, manuscript writing TZ: Funding acquisition, Data analysis, Manuscript writing and editing QZ: Gas measurements and data sorting XG: Data curation supporting, Formal analysis supporting TH: Resources supporting SY: Gas measurements.

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42061013, 41701081) and Guizhou Provincial Science and Technology Projects (ZK(2022)146, (2020)1Y118).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Baldock, J., Wheeler, I., Mckenzie, N., and Mcbratney, A. (2012). Soils and climate change: Potential impacts on carbon stocks and greenhouse gas emissions, and future research for Australian agriculture. Crop Pasture Sci. 63, 269. doi:10.1071/CP11170

Bell, T. H., Klironomos, J. N., and Henry, H. a. L. (2010). Seasonal responses of extracellular enzyme activity and microbial biomass to warming and nitrogen addition. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 74 (3), 820–828. doi:10.2136/sssaj2009.0036

Blodau, C., Basiliko, N., and Moore, T. R. (2004). Carbon turnover in peatland mesocosms exposed to different water table levels. Biogeochemistry 67 (3), 331–351. doi:10.1023/B:BIOG.0000015788.30164.e2

Bodelier, P., Br-Gilissen, M.-J., Meima-Franke, M., and Hordijk, K. (2012). Structural and functional response of methane-consuming microbial communities to different flooding regimes in riparian soils. Ecol. Evol. 2 (1), 106–127. doi:10.1002/ece3.34

Bodelier, P. L., and Laanbroek, H. J. (2004). Nitrogen as a regulatory factor of methane oxidation in soils and sediments. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 47 (3), 265–277. doi:10.1016/s0168-6496(03)00304-0

Bonnett, S., Blackwell, M., Leah, R., Cook, V., O'connor, M., and Maltby, E. (2013). Temperature response of denitrification rate and greenhouse gas production in agricultural river marginal wetland soils. Geobiology 11 (3), 252–267. doi:10.1111/gbi.12032

Braker, G., and Conrad, R. (2011). in Adv. Appl. Microbiol. Laskin. Editors S. Sariaslani, and G. M. Gadd (Academic Press), 33–70.

Burkett, V., and Kusler, J. (2000). Climate change: Potential impacts and interactions in wetlands of the untted states. J. Am. Water. Resour. As. 36 (2), 313–320. doi:10.1111/j.1752-1688.2000.tb04270.x

Chen, H., Zou, J., Cui, J., Nie, M., and Fang, C. (2018). Wetland drying increases the temperature sensitivity of soil respiration. Soil Biol. Biochem. 120, 24–27. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2018.01.035

Chen, Q., Ma, J., Liu, J., Zhao, C., and Liu, W. (2013). Characteristics of greenhouse gas emission in the Yellow River Delta wetland. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 85, 646–651. doi:10.1016/j.ibiod.2013.04.009

Chimner, R. A., and Cooper, D. J. (2003). Influence of water table levels on CO2 emissions in a Colorado subalpine fen: An in situ microcosm study. Soil Biol. Biochem. 35 (3), 345–351. doi:10.1016/S0038-0717(02)00284-5

Ciarlo, E., Conti, M., Bartoloni, N., and Rubio, G. (2007). The effect of moisture on nitrous oxide emissions from soil and the N2O/(N2O+N2) ratio under laboratory conditions. Biol. Fertil. Soils 43 (6), 675–681. doi:10.1007/s00374-006-0147-9

Cui, P., Fan, F., Yin, C., Song, A., Huang, P., Tang, Y., et al. (2016). Long-term organic and inorganic fertilization alters temperature sensitivity of potential N2O emissions and associated microbes. Soil Biol. Biochem. 93, 131–141. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2015.11.005

Cui, Q., Song, C., Wang, X., Shi, F., Yu, X., and Tan, W. (2018). Effects of warming on N2O fluxes in a boreal peatland of permafrost region, Northeast China. Sci. Total Environ. 616-617, 427–434. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.10.246

Dobbie, K. E., and Smith, K. A. (2003). Nitrous oxide emission factors for agricultural soils in great britain: The impact of soil water-filled pore space and other controlling variables. Glob. Chang. Biol. 9 (2), 204–218. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2486.2003.00563.x

Dobbie, K. E., and Smith, K. A. (2001). The effects of temperature, water-filled pore space and land use on N2O emissions from an imperfectly drained gleysol. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 52 (4), 667–673. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2389.2001.00395.x

Docherty, E. M., and Thomas, A. D. (2021). Larger floods reduce soil CO2 efflux during the post-flooding phase in seasonally-flooded forests of Western Amazonia. Pedosphere 31 (2), 342–352. doi:10.1016/S1002-0160(20)60073-X

Fan, Z., Li, J., Yue, T., Zhou, X., and Lan, A. (2015). Scenarios of land cover in Karst area of Southwestern China. Environ. Earth Sci. 74 (8), 6407–6420. doi:10.1007/s12665-015-4223-z

Fennessy, M. S. (2014). in Global environmental change. Editor B. Freedman (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands), 255–261.

Fu, G., Shen, Z., Zhang, X., and Zhou, Y. (2012). Response of soil microbial biomass to short-term experimental warming in alpine meadow on the Tibetan Plateau. Appl. Soil Ecol. 61, 158–160. doi:10.1016/j.apsoil.2012.05.002

Furlanetto, L. M., Palma-Silva, C., Perera, M. B., and Albertoni, E. F. (2018). Potential carbon gas production in southern Brazil wetland sediments: Possible implications of agricultural land use and warming. Wetlands 38 (3), 485–495. doi:10.1007/s13157-018-0993-x

Gao, J., Ouyang, H., Lei, G., Xu, X., and Zhang, M. (2011). Effects of temperature, soil moisture, soil type and their interactions on soil carbon mineralization in Zoigê alpine wetland, Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 21 (1), 27–35. doi:10.1007/s11769-011-0439-3

Han, G., Yang, L., Yu, J., Wang, G., Mao, P., and Gao, Y. (2013). Environmental controls on net ecosystem CO2 exchange over a reed (phragmites australis) wetland in the Yellow River Delta, China. Estuaries Coast. 36 (2), 401–413. doi:10.1007/s12237-012-9572-1

He, J., Xie, J., Su, D., Zheng, Z., Diao, Z., and Lyu, S. (2020). Organic carbon storage and its influencing factors under climate warming of sediments in steppe wetland, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27 (16), 19703–19713. doi:10.1007/s11356-020-08434-8

Henneberg, A., Brix, H., and Sorrell, B. K. (2016). The interactive effect of Juncus effusus and water table position on mesocosm methanogenesis and methane emissions. Plant Soil 400 (1), 45–54. doi:10.1007/s11104-015-2707-y

Houweling, S., Dentener, F., and Lelieveld, J. (2000). Simulation of preindustrial atmospheric methane to constrain the global source strength of natural wetlands. J. Geophys. Res. 105 (D13), 17243–17255. doi:10.1029/2000JD900193

Huang, C.-M., Yuan, C.-S., Yang, W.-B., and Yang, L. (2019). Temporal variations of greenhouse gas emissions and carbon sequestration and stock from a tidal constructed mangrove wetland. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 149, 110568. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.110568

Inglett, K. S., Inglett, P. W., Reddy, K. R., and Osborne, T. Z. (2012). Temperature sensitivity of greenhouse gas production in wetland soils of different vegetation. Biogeochemistry. 108(1-3), 77–90. doi:10.1007/s10533-011-9573-3

Jimenez, K. L., Starr, G., Staudhammer, C. L., Schedlbauer, J. L., Loescher, H. W., Malone, S. L., et al. (2012). Carbon dioxide exchange rates from short- and long-hydroperiod Everglades freshwater marsh. J. Geophys. Res. 117 (G4), G04009. doi:10.1029/2012JG002117

Junna, S., Bingchen, W., Gang, X., and Hongbo, S. (2014). Effects of wheat straw biochar on carbon mineralization and guidance for large-scale soil quality improvement in the coastal wetland. Ecol. Eng. 62 (1), 43–47. doi:10.1016/j.ecoleng.2013.10.014

Kang, H., Jang, I., and Kim, S. (2012). in Global change and the function and distribution of wetlands. Editor B. A. Middleton (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands), 99–114.

Kayranli, B., Scholz, M., Mustafa, A., and Hedmark, Å. (2010). Carbon storage and fluxes within freshwater wetlands: A critical review. Wetlands 30 (1), 111–124. doi:10.1007/s13157-009-0003-4

Khalid, M. S., Shaaban, M., and Hu, R. (2019). N2O, CH4, and CO2 emissions from continuous flooded, wet, and flooded converted to wet soils. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 19 (2), 342–351. doi:10.1007/s42729-019-00034-x

Kirschbaum, M. U. F. (2000). Will changes in soil organic carbon act as a positive or negative feedback on global warming? Biogeochemistry 48 (1), 21–51. doi:10.1023/A:1006238902976

Krauss, K. W., and Whitbeck, J. L. (2012). Soil greenhouse gas fluxes during wetland forest retreat along the lower savannah river, Georgia (USA). Wetlands 32 (1), 73–81. doi:10.1007/s13157-011-0246-8

Li, X., Sardans, J., Hou, L., Liu, M., Xu, C., and Peñuelas, J. (2020). Climatic temperature controls the geographical patterns of coastal marshes greenhouse gases emissions over China. J. Hydrol. X. 590, 125378. doi:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2020.125378

Liu, Y., Liu, G., Xiong, Z., and Liu, W. (2017). Response of greenhouse gas emissions from three types of wetland soils to simulated temperature change on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Atmos. Environ. X. 171, 17–24. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2017.10.005

Liu, L., Jiang, Y., Gao, J., Feng, A., Jiao, K., Wu, S., et al. (2022). Concurrent climate extremes and impacts on ecosystems in southwest China. Remote Sens. 14, 1678. doi:10.3390/rs14071678

Macdonald, J. A., Fowler, D., Hargreaves, K. J., Skiba, U., Leith, I. D., and Murray, M. B. (1998). Methane emission rates from a northern wetland; response to temperature, water table and transport. Atmos. Environ. X. 32 (19), 3219–3227. doi:10.1016/S1352-2310(97)00464-0

Martens-Habbena, W., Berube, P. M., Urakawa, H., De La Torre, J. R., and Stahl, D. A. (2009). Ammonia oxidation kinetics determine niche separation of nitrifying Archaea and Bacteria. Nature 461 (7266), 976–979. doi:10.1038/nature08465

Martikainen, P. J., Nykänen, H., Crill, P., and Silvola, J. (1993). Effect of a lowered water table on nitrous oxide fluxes from Northern Peatlands. Nature 366 (6450), 51–53. doi:10.1038/366051a0

Maucieri, C., Zhang, Y., Mcdaniel, M. D., Borin, M., and Adams, M. A. (2017). Short-term effects of biochar and salinity on soil greenhouse gas emissions from a semi-arid Australian soil after re-wetting. Geoderma 307, 267–276. doi:10.1016/j.geoderma.2017.07.028

Mcinerney, E., and Helton, A. M. (2016). The effects of soil moisture and emergent herbaceous vegetation on carbon emissions from constructed wetlands. Wetlands 36 (2), 275–284. doi:10.1007/s13157-016-0736-9

Mckenzie, C., Schiff, S., Aravena, R., Kelly, C., and Louis, V. (1998). Effect of temperature on production of CH4 and CO2 from peat in a natural and flooded boreal forest wetland. Clim. Change 40 (2), 247–266. doi:10.1023/A:1005416903368

Morrissey, E. M., Berrier, D. J., Neubauer, S. C., and Franklin, R. B. (2014). Using microbial communities and extracellular enzymes to link soil organic matter characteristics to greenhouse gas production in a tidal freshwater wetland. Biogeochemistry 117 (2), 473–490. doi:10.1007/s10533-013-9894-5

Morse, J. L., and Bernhardt, E. S. (2013). Using 15N tracers to estimate N2O and N2 emissions from nitrification and denitrification in coastal plain wetlands under contrasting land-uses. Soil Biol. Biochem. 57, 635–643. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2012.07.025

Na, L., Wang, G., Gao, Y., and Wang, J. (2011). Warming effects on plant growth, soil nutrients, microbial biomass and soil enzymes activities of two alpine meadows in Tibetan Plateau. Pol. J. Ecol. 59, 25–35. doi:10.3402/polar.v30i0.15942

Rasilo, T., Hutchins, R. H. S., Ruiz-González, C., and Del Giorgio, P. A. (2017). Transport and transformation of soil-derived CO2, CH4 and DOC sustain CO2 supersaturation in small boreal streams. Sci. Total Environ. 579, 902–912. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.10.187

Reichstein, M., Bahn, M., Ciais, P., Frank, D., Mahecha, M. D., Seneviratne, S. I., et al. (2013). Climate extremes and the carbon cycle. Nature 500 (7462), 287–295. doi:10.1038/nature12350

Rey, A., Petsikos, C., Jarvis, P. G., and Grace, J. (2010). Effect of temperature and moisture on rates of carbon mineralization in a Mediterranean oak forest soil under controlled and field conditions. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 56 (5), 589–599. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2389.2004.00699.x

Rinnan, R., Stark, S., and Tolvanen, A. (2009). Responses of vegetation and soil microbial communities to warming and simulated herbivory in a subarctic heath. J. Ecol. 97 (4), 788–800. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2745.2009.01506.x

Salimi, S., Almuktar, S. a. a. a. N., and Scholz, M. (2021). Impact of climate change on wetland ecosystems: A critical review of experimental wetlands. J. Environ. Manage. 286, 112160. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.112160

Schaufler, G., Kitzler, B., Schindlbacher, A., Skiba, U., Sutton, M. A., and Zechmeister-Boltenstern, S. (2010). Greenhouse gas emissions from European soils under different land use: Effects of soil moisture and temperature. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 61 (5), 683–696. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2389.2010.01277.x

Silvola, J., Alm, J., Ahlholm, U., Nykanen, H., and Martikainen, P. J. (1996). CO2 fluxes from peat in boreal mires under varying. J. Ecol. 84 (2), 219. doi:10.2307/2261357

Sovik, A., Augustin, J., Heikkinen, K., Huttunen, J., Necki, J., Karjalainen, S., et al. (2006). Emission of the greenhouse gases nitrous oxide and methane from constructed wetlands in Europe. J. Environ. Qual. 35, 2360–2373. doi:10.2134/jeq2006.0038

Tian, Y., Ouyang, H., Gao, Q., Xu, X., Song, M., and Xu, X. (2010). Responses of soil nitrogen mineralization to temperature and moisture in alpine ecosystems on the Tibetan Plateau. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2, 218–224. doi:10.1016/j.proenv.2010.10.026

Toczydlowski, A. J. Z., Slesak, R. A., Kolka, R. K., and Venterea, R. T. (2020). Temperature and water-level effects on greenhouse gas fluxes from black ash (Fraxinus nigra) wetland soils in the Upper Great Lakes region, USA. Appl. Soil Ecol. 153, 103565. doi:10.1016/j.apsoil.2020.103565

Treat, C. C., Wollheim, W. M., Varner, R. K., Grandy, A. S., Talbot, J., and Frolking, S. (2014). Temperature and peat type control CO2 and CH4 production in Alaskan permafrost peats. Glob. Chang. Biol. 20(8), 2674–2686. doi:10.1111/gcb.12572

Vilakazi, B. S., Zengeni, R., Mafongoya, P., Ntsasa, N., and Tshilongo, J. (2021). Seasonal effluxes of greenhouse gases under different tillage and N fertilizer management in a dryland maize mono-crop. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 21, 2873–2883. doi:10.1007/s42729-021-00574-1

Wang, H., Liao, G., D’souza, M., Yu, X., Yang, J., Yang, X., et al. (2016). Temporal and spatial variations of greenhouse gas fluxes from a tidal mangrove wetland in Southeast China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 23 (2), 1873–1885. doi:10.1007/s11356-015-5440-4

Wang, L., Wang, P., Sheng, M., and Tian, J. (2018a). Ecological stoichiometry and environmental influencing factors of soil nutrients in the karst rocky desertification ecosystem, southwest China. Glob. Ecol. Conservation 16, e00449. doi:10.1016/j.gecco.2018.e00449

Wang, X. J., Ye, C. S., Zhang, Z. J., Guo, Y., Yang, R. L., and Chen, S. H. (2018b). Effects of temperature shock on N2O emissions from denitrifying activated sludge and associated active bacteria. Bioresour. Technol. 249, 605–611. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2017.10.070

Wang, J., Quan, Q., Chen, W., Tian, D., Ciais, P., Crowther, T. W., et al. (2021). Increased CO2 emissions surpass reductions of non-CO2 emissions more under higher experimental warming in an alpine meadow. Sci. Total Environ. 769, 144559. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144559

Wu, X., Cao, R., Wei, X., Xi, X., Shi, P., Eisenhauer, N., et al. (2017). Soil drainage facilitates earthworm invasion and subsequent carbon loss from peatland soil. J. Appl. Ecol. 54 (5), 1291–1300. doi:10.1111/1365-2664.12894

Wu, J., Wang, H., Li, G., Wu, J., Gong, Y., and Wei, X. (2022). Unimodal response of N2O flux to changing rainfall amount and frequency in a wet meadow in the Tibetan Plateau. Ecol. Eng. 174, 106461. doi:10.1016/j.ecoleng.2021.106461

Xiong, Z., Li, S., Yao, L., Liu, G., Zhang, Q., and Liu, W. (2015). Topography and land use effects on spatial variability of soil denitrification and related soil properties in riparian wetlands. Ecol. Eng. 83, 437–443. doi:10.1016/j.ecoleng.2015.04.094

Yang, J., Liu, J., Hu, X., Li, X., Wang, Y., and Li, H. (2013). Effect of water table level on CO2, CH4 and N2O emissions in a freshwater marsh of Northeast China. Soil Biol. Biochem. 61, 52–60. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2013.02.009

Yang, G., Chen, H., Wu, N., Tian, J., Peng, C., Zhu, Q., et al. (2014). Effects of soil warming, rainfall reduction and water table level on CH4 emissions from the Zoige peatland in China. Soil Biol. Biochem. 78, 83–89. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.07.013

Yvon-Durocher, G., Allen, A. P., Bastviken, D., Conrad, R., Gudasz, C., St-Pierre, A., et al. (2014). Methane fluxes show consistent temperature dependence across microbial to ecosystem scales. Nature 507 (7493), 488–491. doi:10.1038/nature13164

Zhang, T., Wang, G. X., Yang, Y., Mao, T. X., and Chen, X. P. (2015). Non-growing season soil CO2 flux and its contribution to annual soil CO2 emissions in two typical grasslands in the permafrost region of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 71, 45–52. doi:10.1016/j.ejsobi.2015.10.004

Zhang, T., Liu, X., and An, Y. (2020a). Fluctuating water level effects on soil greenhouse gas emissions of returning farmland to wetland. J. Soils Sediments 20 (11), 3857–3866. doi:10.1007/s11368-020-02730-z

Zhang, Y., Hou, W., Chi, M., Sun, Y., An, J., Yu, N., et al. (2020b). Simulating the effects of soil temperature and soil moisture on CO2 and CH4 emissions in rice straw-enriched paddy soil. Catena 194, 104677. doi:10.1016/j.catena.2020.104677

Zhao, M., Han, G., Li, J., Song, W., Qu, W., Eller, F., et al. (2020). Responses of soil CO2 and CH4 emissions to changing water table level in a coastal wetland. J. Clean. Prod. 269, 122316. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122316

Keywords: hydrothermal fluctuation, CH4, N2O, global warming potential, soil incubation

Citation: He Y, Zhang T, Zhao Q, Gao X, He T and Yang S (2022) Response of GHG emissions to interactions of temperature and drying in the karst wetland of the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau. Front. Environ. Sci. 10:973900. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.973900

Received: 20 June 2022; Accepted: 25 October 2022;

Published: 11 November 2022.

Edited by:

Hong Liao, Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology, ChinaReviewed by:

Muhammad Shaaban, Bahauddin Zakariya University, PakistanCopyright © 2022 He, Zhang, Zhao, Gao, He and Yang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tao Zhang, emhhbmd0YW9lY29Ab3V0bG9vay5jb20=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.