- 1School of Economics and Management, Beijing Institute of Petrochemical Technology, Beijing, China

- 2Waikato Management School, The University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand

Integrated Reporting (IR), as a novel sustainability-oriented organizational reporting approach, is expected to produce better corporate reporting for stakeholders and promote greater transparency and accountability in the capital market. This paper offers a theoretical framework that integrates five mainstream IR theories: stakeholder theory, agency theory, signalling theory, legitimacy theory, and institutional theory. Based on the theoretical framework, there are three drivers for companies to improve their IR disclosure practices: to mitigate information asymmetry between the organisation and all stakeholders; to signal superior quality, legitimacy, and conformity to all stakeholders; and to discharge accountability to all stakeholders. Direct and indirect costs are the main factors that lead to poor IR disclosure practices. This study is the first attempt to construct an integrated theoretical framework for IR. The constructed framework can be adopted as a theoretical foundation for future empirical studies with regard to IR.

1 Introduction

Integrated Reporting (IR) is a newly emerged corporate reporting approach to communicating to stakeholders about organisational value creation. It incorporates a number of features (e.g., intellectual capital, corporate social responsibility, and strategy) of early corporate reporting practices and shows some clear advantages over early corporate reporting practices by overcoming some limitations of early corporate reporting practices. Developments in corporate reporting practices and related regulations worldwide are heading towards the adoption of IR practices (EY, 2014; Howitt, 2016). South Africa was the first country to explicitly mandate (on an apply or explain basis) companies listed on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange to publish integrated reports and to follow its local IR framework, the King III Report on Corporate Governance for South Africa (known as King III) (Cheng et al., 2014). The United Kingdom and some countries in the European Union, especially Germany and France, also moved towards mandating IR. However, IR is still on a voluntary adoption basis in most countries, as for example in Malaysia, Singapore, India, Turkey, and Japan, where the voluntary adoption of IR has been backed by their governments. A significant global IR development is the establishment of the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC). The International Integrated Reporting Framework (IIRF) prescribed by IIRC is regarded as a significant achievement (Eccles & Krzus, 2014). Currently, the framework is the most commonly used international guideline by scholars and practitioners of IR research and adoption.

The primary areas of focus in previous IR studies are IR disclosures, evaluation of IR disclosure practices, and hypothesis testing in relation to the determinants and effects of IR practices, including the adoption of IR and IR disclosure practices. However, after reviewing 210 IR articles published from 2009 to 2020, Jayasiri et al. (2022) point out that a large number of IR studies do not use any theories. Hsiao et al. (2022) report a similar finding. Especially, there is a paucity of conceptual research focusing on theoretical frameworks underpinning the use of IR. According to Gray et al. (2009), “Theory is, at its simplest, a conception of the relationship between things. It refers to a mental state or framework and, as a result, determines, inter alia, how we look at things, how we perceive things, what things we see as being joined to other things and what we see as “good” and what we see as “bad” (p. 6). A theoretical framework is a structure that can hold, support, introduce and describe a theory that explains why the research problem under study exists (Abend, 2008). IR practice is a complex business social phenomenon. Thus, there is a need to have deeper insights into IR practices and gain a fuller understanding of IR practices. To our knowledge, there has been no broad review of theoretical perspectives that can be adopted to explain IR practices. Although IR is the new development of sustainability reporting (SR), theory-focused studies concerning SR theoretical frameworks are scarce in extant SR literature. Lai and Stacchezzini (2021), as a conceptual analysis research from a normative perspective, are concerned with organisational and professional changes associated with the evolution of SR from the 1960s to the 21st century. The theory derived from Suddaby and Viale (2011) is adopted to illuminate how organisational fields and professional jurisdictions interact with the development of SR. Moses et al. (2020) is a meta-analysis that explores the association between board governance and SR disclosure practices. Moses et al. (2020) review the literature with regards to SR disclosure practices in association with board governance and use four popular theories associated with SR disclosure practices, namely agency, legitimacy, stakeholder, and signaling theories, to build links between board governance variables and SR disclosure practices. Based on the theoretical analysis, Moses et al. (2020) conceptually verify the theoretical propositions. Ribeiro et al. (2016) conduct an empirical analysis of the determinants of the extent of SR disclosures in the public sector. Their hypotheses are developed based on legitimacy theory and institutional theory. Ribeiro et al. (2016) empirically verify the theoretical assumptions. However, the two theories are not used in combination. In other words, legitimacy theory or institutional theory are adopted alone when developing an individual hypothesis. No matter Moses et al. (2020) or Ribeiro et al. (2016), they focus on the operationalisation of the selected theories. That is to say, their purpose is to examine whether empirical or conceptually support or detract from the selected theories.

This paper aims to provide an integrative and summative theoretical justification for IR. The main purposes of this paper are two-fold. The first is to synthesise and unify the somewhat scattered previous studies which provide a theoretical underpinning for IR. Considering there is no single motivation for adopting IR, the second is to reveal and theorise organisations’ motivations with regard to releasing stand-alone integrated reports and selecting their IR disclosure practices.

It is believed that there is no single theory that can solely interpret IR practices (Gray et al., 1995a; Omran & El-Galfy, 2014). Using multiple theories can allow deeper insights into IR practices and provide a fuller understanding (Deegan et al., 2000). Many different theories have been applied in prior information disclosure studies. Faced with so many choices, we need to decide which theories should be focused on. The first consideration is that these theories should adapt to the nature of IR. Cotter et al. (2011, p.1) believe that “the choice of a suitable theory to underpin the research depends on the type of information disclosure being examined and the external parties considered”. The second consideration is that we need to ensure the theories adopted are not competing but complementary to each other (Gray et al., 1995b). In other words, analysing the perspectives of multiple theories should reach compatible interpretations of IR disclosure practices. Thus, stakeholder theory, agency theory, signalling theory, legitimacy theory, and institutional theory, which are generally adopted in IR studies and are regarded as theories that are consistent with the nature of IR, are chosen. Among IR (and SR) studies that use a theoretical foundation, calculation results show that stakeholder, agency, institutional, legitimacy and signalling theories are the most widely adopted theories (Hsiao et al., 2022; Jayasiri et al., 2022). These theories have internal connections. For instance, the notion of “signalling legitimacy” stemmed from legitimacy theory and can be borrowed by signalling theory (Watson et al., 2002). Finally, this paper presents an integrated theoretical framework consisting of five theories. We find that IR helps organisations: 1) to mitigate information asymmetry between the organisation and all stakeholders; 2) to signal superior quality, legitimacy, and conformity to all stakeholders; and 3) to discharge accountability to all stakeholders.

This study differs from prior IR (and SR) studies and thus contributes to the IR literature. This paper is not a systematic review and agenda-setting research that investigates the diffusion of IR study and is not an empirical research. It focuses on an underestimated research field—the complementarity between mainstream theories concerning IR disclosure practices—which has not been adequately investigated yet. By linking IR—the latest developments in SR—with the complementarity between theories, this paper contributes to the literature. We can say that this paper is a useful complement to the latest IR studies that focus on discussing the operationalisation of theories in the context of IR using literature analysis and empirical analysis. This paper may become a valuable reference to scholars and practitioners who are keen to understand “the concepts and potential applications of each individual theory and the relationships between and among them” in the context of IR (Chen & Roberts, 2010, p. 652). Moreover, the theoretical framework established in this paper syntheses the most widely used five theories in prior IR studies and thus has the potential to comprehensively explain the phenomenon of IR disclosure practices (Ribeiro et al., 2016). To our best knowledge, this study is the first attempt to construct an integrated theoretical framework for IR. This paper captures multiple theoretical explanations of motivations of IR practices and uses the theoretical framework to absorb them all, which goes beyond the single motivation identified by prior studies.

The paper is organised in four sections. Sections 2 reviews the stakeholder theory, agency theory, signalling theory, legitimacy theory, and institutional theory, respectively. The assumptions underpinning the theories are identified, and the implications of these theories for the current IR study are explained. Section 3 explains the nexus between these theories and summarises the similarities and differences. On this basis, an integrated theoretical framework is suggested. Section 4 provides discussions. Section 5 summarises the paper.

2 Theoretical traditions for integrated reporting

2.1 Stakeholder theory

2.1.1 Overview

There are two theoretical positions, shareholder theory and stakeholder theory, which have been recognised as “two polar opposites” in the management literature (Alam, 2018). Shareholder theory focuses on shareholder primacy (Friedman, 1970). This perspective, according to economic theories, argues that shareholder primacy will result in a better resources allocation and will benefit everyone in the society (Quinn & Jones, 1995; Tantalo & Priem, 2016). However, this perspective is criticised as narrow and restrictive because it focuses only on shareholders and ignores or mistreats other stakeholders (Gray et al., 1988).

From the perspective of shareholder theory, shareholders are viewed as the owners, who can decide how to manage their capitals and properties because contracts prescribe their rights with respect to capitals and properties; managers are thus viewed as the agents of shareholders (Freeman, 2001; Asher et al., 2005). However, from the perspective of stakeholder theory, rights with respect to properties and capitals are socially constructed and are not ultimate rights (Donaldson & Preston, 1995; Etzioni, 1998; Asher et al., 2005). In terms of business objectives, from the perspective of shareholder theory, Friedman (1962, 1970) suggests that a company should have only one objective—maximising the profits for shareholders. From the perspective of stakeholder theory, the business objectives can be extended to include stakeholder objectives (Clarkson, 1995; Mitchell et al., 1997; Freeman et al., 2004). Stakeholder theory emphasises that an organisation needs to meet the objectives of its various stakeholders, rather than only the objectives of shareholders as in shareholder theory because “stakeholder theory highlights organisational accountability beyond simple economic or financial performance” (Guthrie et al., 2006, p. 256).

2.1.2 Stakeholder definition, identification, and prioritisation

The term “stakeholder” was first proposed in an internal memorandum at the Stanford Research Institute in 1963 (Freeman, 1984). Since then, there have been numerous definitions of the stakeholder. Initially, the shareholder was considered the sole stakeholder (Friedman, 1962). However, Freeman (1984) expands the definition of stakeholder by providing a classical definition, from a strategic management point of view, to include any group that is likely to affect or be affected by organisational activities.

Many scholars have attempted to identify and differentiate stakeholder groups. For example, potential categories have included external and internal stakeholders (Pearce, 1982; Carroll, 1989); strategic and moral stakeholders (Goodpaster, 1991); supportive, marginal, non-supportive, and mixed blessing stakeholders (Savage et al., 1991); and single issue and multiple issues stakeholders (Wood, 1994). Clarkson (1995) believes that stakeholders can be divided into two categories, namely primary and secondary stakeholders. Primary stakeholders, including shareholders, employees, customers, suppliers, lenders, government, and communities, are considered to have priorities because they are critical for the organisation’s survival. The secondary stakeholders comprising environmentalists and media, do not rely on the organisation and are not considered to be vital for the organisation’s survival. Mitchell et al. (1997) endow the stakeholder identification and salience with three stakeholder attributes: power, legitimacy, and urgency. Based on these three relationship attributes, they categorise stakeholders into eight groups from the lowest to the highest priority (non-stakeholder, dormant, discretionary, demanding, dominant, dangerous, dependent, and definitive stakeholders). Friedman and Miles (2002) classify stakeholder groups into four types: whose with explicit/implicit recognised contracts and compatible interests (e.g., shareholders, top management, partners); those with explicit/implicit recognised contracts and incompatible interests (e.g., government, customers, lenders, suppliers and other creditors); those with unrecognised implicit contracts and compatible interests (e.g., the general public, trade associations); and those with no contracts and incompatible interests (e.g., aggrieved or criminal members of the public).

2.1.3 The branches of stakeholder theory

There are many perspectives on stakeholder theory. Donaldson and Preston (1995) frame stakeholder theory into three different versions: descriptive, normative, and instrumental. Berman et al. (1999) separate stakeholder theory into two distinct stakeholder management models: strategic stakeholder management (an instrumental approach) and intrinsic stakeholder commitment (a normative approach). Among these perspectives, two major branches of stakeholder theory are prominent in the literature: the ethical (moral or normative) branch, and the managerial (positive) branch (Gray et al., 1996; Guthrie et al., 2006; Belal & Owen, 2007; Belal, 2008; Deegan, 2009; Gray et al., 2009).

The ethical branch proposes that all stakeholders have the same right to be considered and treated fairly, regardless of what the stakeholder’s power1 is (Deegan, 2009). Stoney and Winstanley (2001) emphasise “the moral role of organisations and their enormous social effects on people’s lives” (p.608). Thus, the ethical perspective relates directly to Gray et al.’s (1996) accountability model of stakeholder theory. According to Gray et al. (2009, p. 25), “the organisation owes an accountability to all its stakeholders” rather than only focusing on powerful stakeholders who provide critical resources to the organisation (Deegan & Unerman, 2006). However, when the interests of stakeholder groups conflict, it is a challenge for managers to treat all stakeholders fairly (Fernando & Lawrence, 2014). Nevertheless, Hasnas (1998) points out that an organisation must manage stakeholders’ conflicting interests “to attain the optimal balance among them” (p. 32). The managerial branch, unlike the ethical one, is a “management centred” perspective, centred mainly on managing the relationship between an organisation and its critical stakeholders. The identification of critical stakeholders is based on “the extent to which the organisation believes the interplay with each group needs to be managed in order to further the interests of the organisation” (Gray et al., 1996, p. 45). From this perspective, an organisation ought to be accountable to powerful stakeholders who control the critical resources of the organisation, rather than all stakeholders as in the ethical perspective (Fernando & Lawrence, 2014). The more critical the stakeholders’ resources to the organisation, the greater is the accountability of the organisation to meet the expectations of those stakeholders (Deegan, 2009).

2.1.4 Stakeholder accountability

It is expected that organisations are accountable for their activities (Alam, 2018). Jones (1977) claims that accountability implies an obligation to explain to somebody else, who has the authority to evaluate the account and allocate compliments or criticism. Stewart (1984) establishes a ladder of accountability, comprising five types of accountability: accountability for probity and legality; process accountability; performance accountability; programme accountability; and policy accountability. In addition, Laughlin (1990) proposes the concepts of contractual accountability and communal accountability. According to Gray et al. (1996), accountability is “the duty to provide an account (by no means necessarily a financial account) or reckoning of those actions for which one is held responsible” (p. 38). In order to explain the possible reasons for stakeholder accountability, Werhane and Freeman (1997) identify three types of analysis: interest-based; rights-based, and duty-based. Compared with interest-based and rights-based accountability, duty-based accountability is the widest and looks at organisational responsibilities to stakeholders. Based on the above definitions, Christensen and Ebrahim, 2006 conceptualise accountability as “being answerable to stakeholders for the actions of the organisation” (p. 196). The notion of accountability may be derived from the ethical (normative) perspective of stakeholder theory, in which stakeholders have a right to information about how an organisation affects them (Deegan, 2009).

2.1.5 Stakeholder involvement

According to Waddock (2002), there are three levels of stakeholder involvement: stakeholder mapping (first level), in which the company maps its stakeholders to distinguish between primary and secondary; stakeholder management (second level), in which the company attempts to manage stakeholder expectations and balance different positions; and stakeholder engagement (third level), in which the company engages its stakeholders in decision-making processes, shares information, has dialogues and establishes a mutual responsibility model (Manetti, 2011; Rinaldi, 2013). It is believed that high-level accountability towards stakeholders can be fulfilled if an organisation is inclined to stakeholder engagement (Freeman, 1984; Silvestri et al., 2017).

2.1.6 Implications of stakeholder theory for integrated reporting

According to the definition provided by IIRC (2013), stakeholders are “those groups or individuals that can reasonably be expected to be significantly affected by an organisation’s business activities, outputs or outcomes, or whose actions can reasonably be expected to significantly affect the ability of the organisation to create value over time” (p.33). IIRC (2013) advocates that “an integrated report benefits all stakeholders interested in an organisation’s ability to create value over time, including employees, customers, suppliers, business partners, local communities, legislators, regulators and policy-makers” (p.4). Value creation by embracing all stakeholders fits in ideally with the nature of IR (Haller & Van Staden, 2014). Like wise, Conway (2019) also argues that “the rationale behind IR is underpinned by stakeholder theory” (p.607). Songini and Pistoni (2015) believe that IR can satisfy the information needs of the overall stakeholders’ categories. Similarly, Eccles et al. (2010) also see IR as a channel of communication for all stakeholders.

Steenkamp (2018) believes that the purpose of IR is to enhance accountability for stakeholders via integrated reports. Silvestri et al. (2017) classify accountability into two categories: strong accountability and weak accountability. From the strong accountability perspective, IR is used as a strong accountability tool by companies to be answerable towards their stakeholders; from the weak accountability perspective, IR is regarded as a reputational tool. Quarchioni et al. (2020) claim that IR is not only a stakeholder accountability tool but a stakeholder managerial tool.

Kılıç and Kuzey (2018b) believe that according to stakeholder theory, gender-diverse boards can better recognise the needs of stakeholders, which can enhance a company’s ability to manage the needs of different groups of stakeholders. Moreover, a higher practice of forward-looking disclosures in an integrated report represents a higher ability of a company to manage the needs of different stakeholder groups. Therefore, board gender diversity has a positive relationship with the practice of forward-looking disclosures in an integrated report. García-Sánchez et al. (2013) explore whether the culture of a country affects the adoption of IR. They find that firms from countries with stronger collectivist and feminist values are more likely to adopt IR. García-Sánchez et al. (2013) interpret these results using stakeholder theory and suggest that collectivist and feminist values highlight public welfare, leading firms to adopt IR to enhance the decision-making ability of stakeholders.

Similarly, Vitolla et al. (2019b) examine how national culture impacts IR quality based on a sample of 135 international companies from 28 countries. The results show that firms operating in countries with cultural systems with less power distance, more uncertainty avoidance, less individualism, less masculinity, and less indulgence tend to show higher IR quality. The interpretations of the results are based on the ethical-moral (normative) and strategic-managerial (instrumental) approaches of stakeholder theory, respectively. Vitolla et al. (2019b) believe a cultural system defines whether a country is stakeholder-oriented or shareholder-oriented. From the ethical-moral (normative) approach perspective, low power distance, high collectivism, high feminism, high restraint and high uncertainty avoidance lead to a stakeholder-oriented national culture, shaping a context that encourages firms to report financial and non-financial information in an integrated way. From the strategic-managerial (instrumental) approach perspective, the above national culture elements define the context in which the stakeholders act. In order to strategically manage the information needs of stakeholders, a high IR quality is required. Vitolla et al. (2019c) develop hypotheses regarding the relationship between five kinds of stakeholders’ pressure and IR quality based on stakeholder theory. The results indicate that pressure from customers, environmental protection organisations, employees, shareholders, and governments leads to IR quality. They believe that stakeholder pressure determines IR quality because a higher IR quality represents a proactive response by companies to stakeholders’ expectations.

In addition, according to Ambler and Wilson (1995), stakeholder theory is criticised because it may lead to inefficiency and suboptimality generally because of conflicts among stakeholders. Similarly, Jensen (2001) believes “whereas value maximisation provides corporate managers with a single objective, stakeholder theory directs corporate managers to serve many masters. And, to paraphrase the old adage, when there are many masters, all end up being short-changed. Without the clarity of mission provided by a single-valued objective function, companies embracing stakeholder theory will experience managerial confusion, conflict, inefficiency, and perhaps even competitive failure” (p. 9). However, Conway (2019) points out that this criticism of stakeholder theory is not a problem for IR because IR clarifies the aim of a company by clearly disclosing the company’s objectives and strategy; thus, decisions are made closely surrounding the aim and trade-offs between stakeholder interests are “necessary and acceptable” (p. 611).

2.2 Agency theory

2.2.1 Overview

Agency theory is mainly concerned with the agency problem that arises from the separation of ownership and managerial control (Jensen & Meckling, 1976), which translates to the separation of risk sharing, decision making and control in companies (Fama & Jensen, 1983).

2.2.2 Principal-agent relationship

Agency theory is founded on the principal-agent relationship (also referred to as the agency relationship), which is defined by Jensen and Meckling (1976) as “a contract under which one or more persons [the principal(s)] engage another person (the agent) to perform some service on their behalf which involves delegating some decision-making authority to the agent” (p.308). According to Lambert (2001), the principal is seen as the party who provides capital, endures primary risks and conducts incentives, while the agent is viewed as the party who makes decisions and performs a service on behalf of the principal, and endures secondary risks. In a corporate context, agents mainly correspond to managers, whereas principals primarily correspond to investors (Shehata, 2014).

2.2.3 Agency problem

Two key assumptions underlie a principal-agent relationship: 1) economic rationality (the principal and the agent are interest maximisers); and 2) self-interest (the interests of the principal and the agent are not always aligned) (Berle & Means, 1932; Jensen & Meckling, 1976; Merkl-Davies & Brennan, 2011). Based on these assumptions, agency theory infers that there are conflicts (known as “agency conflict”) inherent in principal-agent relationships, although there is a fiduciary relationship between agents and principals and it is expected that agents act in the interests of the principals (Bhaumik & Gregoriou, 2010; De Villiers & Hsiao, 2017). When the agent does not act in the best interests of the principal, an agency problem emerges, because individualistic and opportunistic interests held by principals and agents impact the efficiency of the principal-agent relationship (Subramaniam, 2018). This type of agency problem is called a “principal-agent problem” (Panda & Leepsa, 2017).

2.2.4 Information asymmetry

According to agency theory, information asymmetry results from managers who have an information advantage over investors (De Villiers & Hsiao, 2017). Specifically, it reflects an information gap that arises from managers possessing private or asymmetric information regarding the true situation of a company (De Villiers & Hsiao, 2017). Information asymmetry may exacerbate agency problems (Scott, 1997). Specifically, information asymmetry may lead to moral hazards (also referred to as hidden costs) and adverse selection (Jensen & Meckling, 1976; Fama & Jensen, 1983; Jensen, 1986).

2.2.5 Agency costs

Agency costs are the summation of the monitoring cost, bonding cost, and the residual loss arising from loopholes in agency relationships (Jensen & Meckling, 1976). Several strategies, including incentive-focused and monitoring strategies, may mitigate agency problems. Incentive-focused strategy aims to provide incentives that induce agent behaviours congruent with the principal’s interests. For instance, employment contracts may be chosen by the investors to provide incentives for aligning the managers’ interest with that of the investors. Accordingly, the cost related to incentive-focused strategies is called a bonding cost (e.g., bonuses and stock options). The second type of strategy for reducing opportunistic behaviour is the monitoring strategy, which aims to monitor managers’ behaviour. It includes external or internal audits (Watts & Zimmerman, 1986), the composition of the board of directors (Fama & Jensen, 1983), and performance evaluation systems (Kaplan & Atkinson, 1989). Accordingly, the costs related to monitoring strategies are called monitoring costs (e.g., mandatory audit costs). Monitoring costs are paid by investors, whereas bonding costs are paid by managers (Shehata, 2014). Residual loss occurs when managers do not aim to maximise the investors’ interest (Morris, 1987).

2.2.6 Implications of agency theory for integrated reporting

Agency theory postulates that IR can be seen as one of the mechanisms to monitor a company’s performance by providing high extent and quality of disclosures to investors (Jensen & Meckling, 1976; De Villiers & Hsiao, 2017; Fasan & Mio, 2017). Thus, IR reduces information asymmetry between investors and managers, allowing investors to monitor managers’ behaviours and to assess whether managers’ actions meet investors’ interests (Jensen & Meckling, 1976; De Villiers & Hsiao, 2017; Fasan & Mio, 2017). Previous studies have shown that IR can also mitigate agency costs.

García-Sánchez and Noguera-Gámez (2017) investigate the effect of voluntary disclosures concerning IR on information asymmetry. They argue that IR provides high extent and quality of voluntary disclosures, which can decrease information asymmetries. Their results indicate that there is a negative relationship between information asymmetry and the adoption of IR, suggesting that IR can mitigate information asymmetry. In another study, Pavlopoulos et al. (2017) find that a higher quality of IR disclosures decreases agency costs.

Wen et al. (2017) use agency theory to test the association between the extent of IR disclosures of Malaysian public listed companies and financial performance. They believe IR can be seen as one of the monitoring mechanisms for the company performance because managers are willing to share a company’s private information with the capital market in order to maximise the company’s value. Finally, Wen et al. (2017) find that the extent of IR disclosures has a significant positive impact on financial performances. Similarly, Frías-Aceituno et al. (2014) find that there is a positive relationship between profitability and the extent of IR disclosures of a company.

Kılıç and Kuzey (2018b) verify that firm size and practices of forward-looking disclosures contained in integrated reports have a positive relationship. They believe that according to agency theory, a larger company incurs a higher level of agency cost associated with high-level information asymmetry compared to small ones. Therefore, larger companies are willing to release forward-looking disclosures in integrated reports in a high-level manner to minimise information asymmetry and accordingly, agency costs. Similarly, Frías-Aceituno et al. (2014) use agency theory to investigate whether there is a positive relationship between firm size and the extent of IR disclosures. They state that larger companies have a greater need for external funds, resulting in an increased likelihood of conflicts of interest between investors and managers. Consequently, larger companies face higher agency costs and greater problems of information asymmetry. IR, as a means of voluntary disclosure, can be adopted to reduce agency costs. Frías-Aceituno et al. (2014) show that firm size has a positive relationship with the extent of IR disclosures.

2.3 Signalling theory

2.3.1 Overview

Signalling theory was initially developed to elucidate uncertainty in workforce markets (Spence, 1973). According to Spence’s (1973) findings, employers lack information about the quality of potential employees and this information asymmetry may impede employers’ selection ability; therefore, high-quality job applicants distinguish themselves from low-quality job applicants by using the signalling function of higher education. Spence’s (1973) work triggered massive studies using signalling theory in management research, in areas including corporate governance (Miller and del Carmen Triana, 2009; Zhang & Wiersema, 2009), entrepreneurship (Certo, 2003; Elitzur and Gavious, 2003; Busenitz et al., 2005; Lester et al., 2006), human resource management (Suazo et al., 2009), and voluntary disclosure in corporate reporting (Ross, 1977).

According to Connelly et al. (2011), signallers are “insiders (e.g., executives or managers) who obtain information about an individual (e.g., Spence, 1973), product (e.g., Kirmani & Rao, 2000), or organisation (e.g., Ross, 1977) that is not available to outsiders” (p. 44). The receivers are defined by these researchers as “outsiders who lack information about the organisation in question but would like to receive this information.” According to Morris (1987), information asymmetry exists between signallers and receivers. In other words, the signallers’ information is superior to that of receivers. The signal is defined as “the publication of a device which acts as a prediction of superior quality” (Morris, 1987, p. 48). Information asymmetry is the precondition for the existence of the signal. In order to be effective, the signal provided by high-quality sellers must not be easily imitated by low-quality sellers. Signalling theory is used to depict the behaviour when signallers and receivers have access to different information and is concerned with reducing information asymmetries between these two parties (Spence, 2002). Typically, signallers must choose whether and how to signal the information, and receivers must choose how to interpret the signal (Omran & El-Galfy, 2014).

According to Connelly et al. (2011), quality is “the underlying, unobservable ability of the signaller to fulfill the needs or demands of an outsider observing the signal” (p. 43). In Spence’s (1973) example, higher education can be regarded as a reliable signal of a job applicant’s quality, based on two premises: 1) potential employees’ quality cannot be observed by employers; and 2) low-quality job applicants are not able to complete higher education. Similarly, Kirmani and Rao (2000) also provide a general example of signalling theory. A product warranty can be regarded as a reliable signal of a product’s quality, based on two premises: 1) buyers are not able to distinguish between high-quality products and low-quality products; and 2) the sellers of low-quality products are not able to provide a product warranty. In Ross’s (1977) example, financial indicators (e.g., interest and dividend payments) can be regarded as a reliable signal of a company’s quality, based on two premises: 1) companies’ quality cannot be observed by external investors; and 2) low-quality companies are not able to sustain these payments.

These above signals can be classified into three categories: intent, camouflage and need (Connelly et al., 2011). Intent signals indicate future action. For example, a company may signal its determination by responding to a competitive action initiated by a rival quickly (Baum & Korn, 1999). Camouflage signals disguise a potential liability by diverting attention away from a potential vulnerability to some other characteristic. For example, companies expanding globally signal their legitimacy by using strategic alliances in order to draw attention away from the liability of foreignness (Dacin et al., 2007). Need signals communicate requirements to the receiver. For example, each of the divisions or subsidiaries of a company signals its need for funds and resources, and the headquarter of the company decides which is signalling the greatest need (Gupta et al., 1999).

2.3.2 Implications of signalling theory for integrated reporting

According to signalling theory, voluntary disclosures, such as non-financial information in corporate reports can be seen as a signalling device to signal the superior quality of a company to the capital market (Spence, 1973; Cohen et al., 2012). In a similar vein, IR containing non-financial disclosures such as intellectual capital and CSR can be used as a signalling device (Visser, 2008).

Albertini (2018) finds that French companies tend to disclose information on increases in capitals in integrated reporting, confirming that insiders in companies purposely use IR to communicate the superior quality of the company. Based on signalling theory, Frías-Aceituno et al. (2014) argue that profitable companies distinguish themselves from low-quality companies through IR in order to reduce the cost of capital and to stabilise or enhance their company value. They then find there is a positive relationship between profitability and the adoption of IR. Likewise, Girella et al. (2019) develop a hypothesis about the relationship between the adoption of IR and profitability based on signalling theory. They find that higher profitability leads a firm to adopt IR. In addition, they also find that companies operating in collectivist countries tend to adopt IR voluntarily. Girella et al. (2019) argue that according to signalling theory, if a company operates in a country with high collectivism in which people are willing to share information, its managers are likely to signal more information out, resulting in the company applying IR voluntarily.

2.4 Legitimacy theory

2.4.1 Overview

Legitimacy theory is concerned with the relationship between the organisation and society (Deegan, 2002; Belal, 2008). Legitimacy theory is based on the notion of a social contract between the organisation and society (Deegan et al., 2002; Deegan, 2006; Magness, 2006; Deegan & Samkin, 2009; Deegan & Unerman, 2011). Shocker and Sethi (1974) provide an explanation of the concept of the social contract:

Any social institution and business with no exception operates in society via a social contract, expressed or implied, whereby its survival and growth are based on the delivery of some socially desirable ends to society in general; and the distribution of economic, social, or political benefits of groups from which it derives its power (p. 67).

Deegan et al. (2000) describe the explicit term of the social contract as the legal system, whereas the implicit term of the social contract refers to un-codified societal expectations.

2.4.2 Legitimacy

According to Suchman (1995), legitimacy is “a generalised perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions” (p. 574). Lindblom (1994) defines legitimacy as “a condition or status which exists when an entity’s value system is congruent with the value system of the larger social system of which the entity is a part” (p. 2). Dowling and Pfeffer (1975) also provide an explanation of legitimacy:

Organisations seek to establish congruence between the social values associated with or implied by their activities and the norms of acceptable behaviour in the larger social system of which they are a part (p. 122).

The above three definitions are concerned with whether the value system of an organisation is congruent with the societal value system. Gray et al. (2009, p. 28) believe that “organisations can only continue to exist if the society in which they are based perceives the organisation to be operating to a value system that is commensurate with the society’s own value system”. This assertion is also supported by other scholars, such as Dowling and Pfeffer (1975), Lindblom (1994), and Magness (2006). Therefore, legitimacy is regarded as a resource, which can determine the organisation’s survival (Dowling & Pfeffer, 1975; Suchman, 1995; O’Donovan, 2002).

Lindblom (1994) distinguishes between legitimacy and legitimation. Legitimacy is considered to be a status or condition, while legitimation is considered to be the process of being adjudged legitimate (Lindblom, 1994). Maurer (1971) also claims that “legitimation is the process whereby an organisation justifies to a peer or superordinate system its right to exist” (p. 361). Therefore, Suchman (1995) argues that “legitimacy is possessed objectively, yet created subjectively” (p. 574).

Suchman (1995) proposes three different legitimacy conceptions: pragmatic legitimacy, moral legitimacy and cognitive legitimacy. Pragmatic legitimacy means that if organisational actions or policies benefit relevant members of the public, the relevant public may see these organisational actions as legitimate. Pragmatic legitimacy is classified into exchange legitimacy, influence legitimacy and dispositional legitimacy (Dumitru and Guşe, 2017). Moral legitimacy reflects the notion that the relevant public may see organisational actions as legitimate when they judge these actions or policies to be “the right things”. Moral legitimacy has four forms: consequential, procedural, structural, personal legitimacy, and legal legitimacy (Suchman, 1995; Durocher et al., 2007). Cognitive legitimacy is based on the relevant public’s cognition rather than on their benefit or moral judgement. Organisations are perceived to be cognitively legitimate if their actions follow the pre-existing pattern of other organisations that are comprehensible and familiar to the relevant public.

2.4.3 Legitimacy gap

According to Lindblom (1994, p. 3), “legitimacy is dynamic in that the relevant publics continuously evaluate corporate output, methods, and goals against an ever-evolving expectation”. Lindblom (1994, p. 2) also argues “when a disparity, actual or potential, exists between the two value systems, there is a threat to the entity’s legitimacy”. The disparity between an organisation’s value system and the societal value system is referred to as the legitimacy gap (Liu & Anbumozhi, 2009).

Wartick and Mahon (1994) contend that legitimacy gaps may occur when:

1) There is a change in the organisation’s output, methods, and goals, but societal expectations of the organisation’s output, methods, and goals remain unchanged;

2) The organisation’s output, methods, and goals and societal expectations change in different directions, or change in the same direction but with differing momentum;

3) The organisation’s output, methods, and goals are unchanged, but societal expectations of the organisation’s output, methods, and goals have changed.

Changes in societal expectations include changes in social awareness (Freedman & Jaggi, 2005; Choi et al., 2013); changes in media influence (Brown & Deegan, 1998; Deegan et al., 2002); changes in relevant group pressure (Deegan & Gordon, 1996); and changes in regulations (Patten, 2002; Cowan & Deegan, 2011).

Alrazi et al. (2016, p. 671) comment on the implications of a legitimacy gap as follows:

The implications of a legitimacy gap could be enormous, leading to potential product boycotts by customers, withdrawals of investments by shareholders, and difficulties in securing loans from banks, while increased lobbying activities by the public, which could lead to increased regulation, and difficulties in hiring qualified staff.

However, it is not easy to determine the legitimacy gap’s existence and size (Wartick & Mahon, 1994).

2.4.4 Strategic perspective and institutional perspective

Depending on the purpose of legitimation, there are two perspectives on legitimacy—institutional legitimacy and organisational (or strategic) legitimacy (Ashford and Gibbs, 1990; Suchman, 1995; Gray et al., 1996). The distinction between institutional legitimacy and organisational/strategic legitimacy is “a matter of perspective, with strategic theorists adopting the viewpoint of organisational managers looking “out”, whereas institutional theorists adopt the viewpoint of society looking “in” (Suchman, 1995, p. 577). The institutional perspective assumes that “cultural definitions determine how the organisation is built, how it is run, and, simultaneously, how it is understood and evaluated” (Suchman, 1995, p. 576). From an institutional perspective (a wider perspective), institutional legitimacy focuses on what institutional structures, procedures and practices as a whole (such as capitalism/socialism) are accepted by society (Chen & Roberts, 2010). These pre-existing structures, procedures and practices are adopted as the baseline to estimate whether the organisation complies with social expectations (Chen & Roberts, 2010). A strategic perspective (a narrower perspective) emphasises “the ways in which organisations instrumentally manipulate and deploy evocative symbols” (Suchman, 1995, p. 572), assuming legitimacy is a “high level of managerial control over legitimating processes” (Suchman, 1995, p. 576). Generally, institutional legitimacy and organisational/strategic legitimacy are complementary, rather than conflicting (AhmedHaji & Anifowose, 2017).

The strategic perspective focuses on strategies employed by companies to “obtain, maintain or repair” organisational legitimacy (Suchman, 1995). Maintaining legitimacy is generally easier than obtaining or repairing legitimacy (O’Donovan, 2002). In order to maintain legitimacy that has already been established and to respond to challenges that may threaten legitimacy, an organisation keeps an eye on changing social expectations and emerging challenges (Maroun, 2018). The extent of an organisation’s efforts to maintain or repair legitimacy relies on the importance of legitimacy for the organisation’s survival. For some organisations, such as those with low-level legitimacy, it is not necessary to invest too much effort into maintaining or repairing legitimacy. Conversely, some organisations, such as those with high-level legitimacy, need to manage their legitimacy more proactively (Suchman, 1995; O’Donovan, 2002; Clarkson et al., 2008).

2.4.5 Legitimation strategies

When organisations face a threat to their legitimacy or a perceived legitimacy gap, there are four legitimation strategies they may apply (Dowling & Pfeffer, 1975; Lindblom, 1994).

1) Adaptation and conformance: change the organisation’s output, methods, and goals to conform with relevant public expectations about the organisation’s performance.

2) Alter expectations: do not change the organisation’s output, methods, and goals but change relevant public expectations about the organisation’s performance.

3) Manage perceptions: do not change the organisation’s output, methods, and goals but educate the relevant public about its actual performance.

4) Avoidance/denial: do not change the organisation’s output, methods, and goals but distract or manipulate/divert relevant public attention away from the issue.

Legitimation strategies can vary between substantive management and symbolic management (Setia et al., 2015). Substantive management is seen as “making real, material changes in organisational goals, structures, process and socially constituted practices”, while symbolic management is depicted acting “so as to appear consistent with social values and expectations” (Ashforth & Gibbs, 1990, pp. 178-180). According to Kim et al. (2007), substantive management is more effective than symbolic management in managing social expectations. In addition, Meznar and Nigh (1995) also propose two strategies named “bridging” and “buffering”. “Bridging” is similar to the concept of substantive management, while “buffering” focuses on protecting organisations from external interference or affecting the external environment through political action, lobbying and advertising. Additionally, Deegan (2002) points out that legitimisation strategies may vary between countries. In this sense, choosing legitimisation strategies requires explicit consideration of the specific jurisdictional context (Deegan, 2002).

2.4.6 Implications of legitimacy theory for integrated reporting

Corporate reports have been regarded as a critical source of legitimation (Dyball, 1998; O’Donovan, 2002). Both mandatory disclosures and voluntary disclosures can lead to legitimisation (Magness, 2006; Lightstone & Driscoll, 2008). Corporate reports, such as IR, are regarded as documents that facilitate companies achieving organisational legitimacy (Chu et al., 2013). In other words, organisations prepare IR in order to gain, maintain or repair their legitimacy to ensure continued access to resources (De Villiers & Maroun, 2017). Managers may prepare integrated reports to manipulate others’ perceptions of their companies by selective reporting of favourable information (Melloni et al., 2016). Albetairi et al. (2018) examine the extent of IR disclosures of Bahraini listed insurance companies and find that a high practice of performance indicator disclosures in a firm’s integrated report is associated with the poor financial performance of the firm. They explain this result using legitimacy theory: a company whose legitimacy is threatened (e.g., one that has poor financial performance) tends to increase the extent of IR disclosures to enhance its communication with stakeholders, gain a better reputation, and maintain legitimacy.

Velte and Stawinoga (2017) see IR as a tool to communicate organisational legitimisation actions; therefore, by being a qualified corporate citizen, an organisation’s image is enhanced. Ahmed Haji and Anifowose (2017) find that there is an overall significant increase in the quality of IR disclosures in South African companies, and the quality of IR disclosures are increasing over time in particular industries. They explain their findings using both the strategic and institutional perspectives of legitimacy theory: the overall significant increase in the quality of IR disclosures is a response to external pressures (strategic legitimacy), and the increase in the quality of IR disclosures within a particular industry indicates institutionalisation (institutional legitimacy). The findings suggest that the strategic and institutional perspectives of legitimacy theory are complementary, rather than conflicting. Nicolò et al. (2021) find a positive relationship between the environmentally and socially sensitive industry membership of European SOEs and the extent of IR disclosures. By using legitimacy theory, Nicolò et al. (2021) argue that environmentally sensitive companies are likely to make more IR disclosures to show that they are operating within accepted environmental and social boundaries so as to maintain their legitimacy. Moreover, socially sensitive companies tend to make more IR disclosures to repair their legitimacy.

2.5 Institutional theory

2.5.1 Overview

Institutionalists focus on identifying institutions and institutional pressures as well as explaining institutional impacts on organisational structures, processes and practices (Greenwood et al., 2008). Institutional researchers contend that organisational structures, processes and practices are the result of institutional pressures (Farooq & Maroun, 2017). Institutions generate institutional pressures on various social actors (individuals and organisations) to force these individuals and organisations to adopt similar structures, processes and practices (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; De Villiers & Alexander, 2014; De Villiers et al., 2014).

2.5.2 Institutionalisation

The concept of institutionalisation stems from the explanation of the nature and origin of social order (Berger & Luckmann, 1967). They argue that social order emerges as individuals communicate and disseminate interpretations with others about their actions (also defined as social interactions), creating a shared social reality. Institutionalisation is defined by Scott (1987) as the process by which actions become repeated over time and acquire similar meanings among members of society. Institutional theory has evolved from the creation of social reality to the institutionalisation of organisations, which emphasises the patterns of organisational behaviour and those patterns’ conformity among organisations (Scott, 1987; Chen & Roberts, 2010). Some scholars (e.g., Meyer & Rowan, 1977; DiMaggio & Powell, 1983) question what makes organisations so similar. They conclude that not all organisational behaviour can be attributed to pursing maximising organisational efficiency and effectiveness; the reason that organisations increasingly homogenise their organisational structures, processes and practices is to meet social expectations or to be socially acceptable.

2.5.3 Isomorphism and decoupling dimensions

There are two dimensions in institutional theory: isomorphism and decoupling. Isomorphism, as the core concept of institutional theory, is described as the “adaptation of an institutional practice by an organisation” (Dillard et al., 2004, p. 509). DiMaggio and Powell (1983, p. 149) define isomorphism as “a constraining process that forces one unit in a population to resemble other units that face the same set of environmental conditions”. Moll et al. (2006) divide isomorphism into two components: competitive isomorphism and institutional isomorphism. They define competitive isomorphism as “how competitive forces drive organisations towards adopting least-cost, efficient structures, and practices” (Moll et al., 2006, p. 187). Institutional isomorphism can be divided into three isomorphism processes: coercive, mimetic, and normative (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983).

According to DiMaggio and Powell (1983, p. 150), coercive isomorphism “results from both formal and informal pressures exerted on organisations by other organisations upon which they are dependent and by cultural expectations in the society in which organisations function”. Coercive pressure results from resource dependence, which means organisations that depend on resources can be constrained by an organisation which effectively controls the same resources (Salter & Hoque, 2018). Coercive isomorphism is usually the result of laws, regulations or social pressures, which force organisations to comply with the respective prescription (Farooq & Maroun, 2017). In other words, coercive isomorphism means organisations are forced by external factors to apply specific internal structures and procedures (Moll et al., 2018). Mimetic isomorphism means that organisations imitate the internal structures and procedures applied by other organisations or themselves that are perceived to be more legitimate and more successful (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Farooq & Maroun, 2017; Moll et al., 2018). Normative isomorphism stems from professionalisation. It is evident when organisations apply structures and procedures promoted by educational institutions and professional institutions (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Farooq & Maroun, 2017; Moll et al., 2018).

Decoupling is the other dimension of institutional theory. It occurs when “the formal organisational structure or practice is separate and distinct from actual organisational practice” (Dillard et al., 2004, p. 510). This separation may be an intentional and/or unintentional action of the organisation (Moll et al., 2006). Organisational structures, procedures and practices are not necessarily the result of maximising organisational efficiency and effectiveness but rather stem from the need to conform to institutional pressures (Powell, 1988; Lounsbury, 2008). In order to balance actual structures, procedures and practices with conformity to institutional pressures, organisations “buffer their formal structures from the uncertainties of technical activities by becoming loosely coupled, building gaps between their formal structures and actual work activities” (Meyer & Rowan 1977, p. 357). There are three indicators of decoupling (see Meyer & Rowan, 1977; Suchman, 1995). The first is ambiguous or generally defined goals, targets and performance indicators, which avoid clear connections between processes and outcomes and technical data. The second is ambiguous or unclearly understood technical processes, and is based on the assumptions that if qualified experts perform the assigned task carefully, the outcome is correct. The third is ambiguous or inexplicitly explained connections between the characteristics of the organisation.

2.5.4 Implications of institutional theory for integrated reporting

Institutional theory is one of the theories used to explain and to predict IR practices (Katsikas et al., 2016). Both isomorphism and decoupling mechanisms can explain the adoption of IR by organisations. For instance, the presence of regulations in South Africa, illustrated by the King III and King IV reports mandating the adoption of IR, is an example of the coercive mechanism (Vaz et al., 2016). Also, the development of the IIRC and its publication of IIRF have become sources of normative pressure for organisations, impelling organisations to do well in IR practices (Farooq & Maroun, 2017; Humphrey et al., 2017). Additionally, organisations’ successful peers who have performed well in IR practices introduce mimetic pressure for organisations (Vaz et al., 2016; Farooq & Maroun, 2017). Producing merely empty rhetoric in IR can be interpreted as evidence of decoupling (Deegan & Unerman, 2011; Farooq & Maroun, 2017; Chikutuma, 2019).

Previous studies have also shown that jurisdictional factors in a country, such as its legal, economic, financial, and cultural systems, have an impact on IR practices. For instance, Jensen and Berg (2012) identify potential country-level determinants of the adoption of IR, based on institutional theory. They find that the adoption of IR is determined by the financial, educational and labour, cultural, and economic systems of a country. They explain that, according to institutional theory, a country’s comprehensive system of financial, educational, cultural and economic institutions exerts institutional pressure on the country’s companies.

Frías-Aceituno et al. (2013) investigate whether the adoption of IR is determined by the legal system of a country. Their findings indicate that companies from countries with civil law are more likely to adopt IR, and companies from a country where regulations are strictly enforced are also more likely to adopt IR. The researchers use institutional theory to explain their findings. Generally, they believe a country’s legal institutions exert institutional pressure (coercive and normative pressures) on companies. Specifically, they assert that the civil law system is more stakeholder-oriented compared with the common law legal system, which focuses on protecting shareholders. Companies in the countries where there is coercive and normative pressure (i.e., the legal system seeks to protect stakeholders) are likely to adopt IR. Moreover, if regulations are strictly enforced, it can be seen as effective protection of stakeholders’ interests. IR is seen as a complementary mechanism to the control mechanisms that ensure companies comply with regulations; thereby, IR is more likely to be adopted in countries that have stronger legal enforcement. Higgins et al. (2014) interpret the findings of interview surveys with managers of early IR-adopting of Australian companies using institutional theory and indicate that the motivation for adopting IR is to signal a company’s strategy and to meet institutional expectations.

3 The integrated theoretical framework

3.1 The relationship between theories

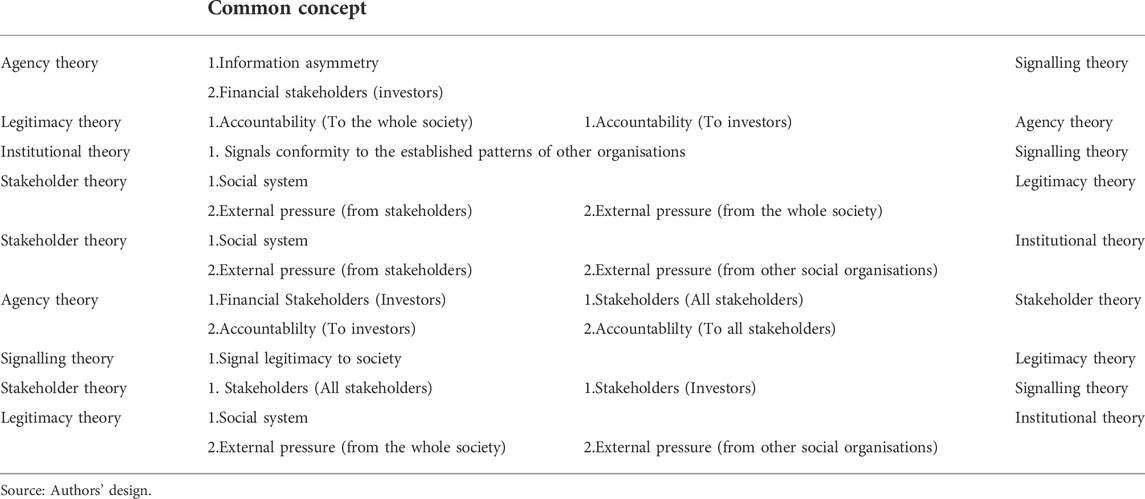

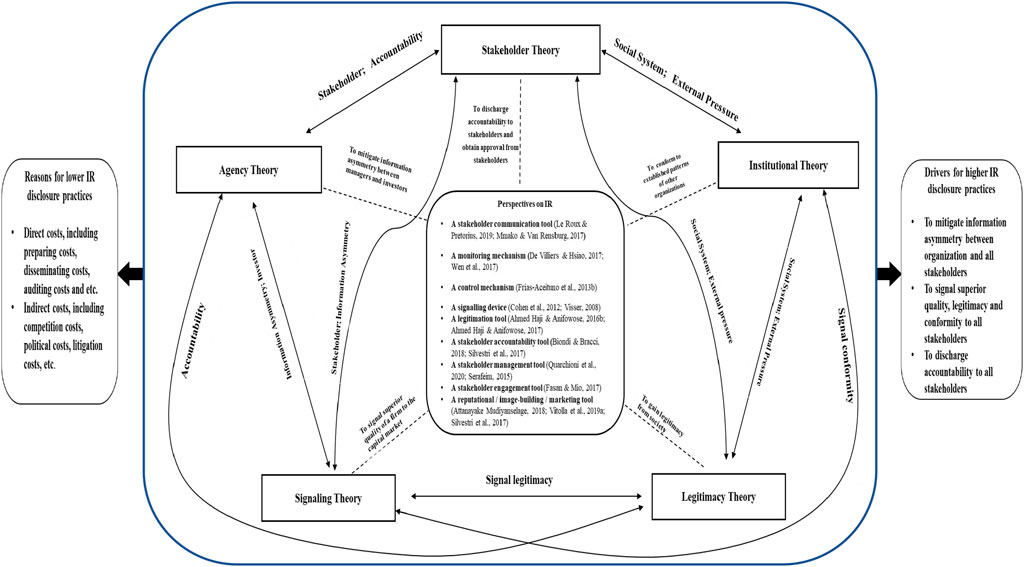

These aforementioned five theories can be broadly classified into two main categories: socio-political theories that include stakeholder, legitimacy, and institutional theory; and economics-based theories based on the wealth maximisation and individual self-interest concepts inherent in agency and signalling theory (Gray et al., 1995b). Stakeholder, legitimacy, and institutional theories are mainly concerned with how companies react to societal and/or political pressures, which means these three theories do not consider company value. In contrast, agency and signalling theories are primarily concerned with maximising company value (Perez, 2018). Table 1 and Table 2 show the similarities and dissimilarities among theories, respectively.

3.1.1 Agency theory and signalling theory

Signalling theory is closely linked to agency theory. Agency theory and signalling theory consider only the economic outcomes of the company. In other words, both theories primarily consider financial stakeholders, rather than a broader spectrum of stakeholders (Fernando & Lawrence, 2014). Moreover, information asymmetry is one of the key concepts in both agency theory and signalling theory. From the perspectives of agency theory and signalling theory, a company has an incentive to mitigate information asymmetry between company management and investors (An, 2012; Liu, 2014).

3.1.2 Stakeholder theory, legitimacy theory, and institutional theory

Stakeholder theory, legitimacy theory, and institutional theory evolve from a similar philosophical background, providing complementary and overlapping views (Azizul Islam & Deegan, 2008). All three theories treat the organisation as part of a broader social system (Deegan, 2006). They also have a common interest: explaining how organisations can survive in a changing society (Chen & Roberts, 2010). Stakeholder, legitimacy, and institutional theories all consider that economic outcomes, as well as organisational efficiency and effectiveness, are necessary but not sufficient for organisations to survive (Chen & Roberts, 2010).

Institutional legitimacy is directly related to institutional theory (Chen & Roberts, 2010). Institutional theorists (e.g., Ashforth & Gibbs, 1990; Oliver, 1991; Suchman, 1995) suggest that conformity to pre-existing institutional patterns is the easiest path to legitimacy because pre-existing institutional patterns must already have the characteristic of legitimacy (Chen & Roberts, 2010). From this perspective, Suchman (1995, p. 576) states “legitimacy and institutionalisation are virtually synonymous”. However, the perspective of institutional theory is narrower than that of legitimacy theory (Chen & Roberts, 2010). Institutional theory does not examine the value systems of society directly (Chen & Roberts, 2010). It sees the pre-existing institutional patterns as symbolic representations of the social value system (Chen & Roberts, 2010). While legitimacy theory does not specifically express how to meet social expectations or to be socially acceptable, institutional theory emphasises that organisations can incorporate pre-existing institutional patterns to achieve survival and success. Carpenter and Feroz (2001) believe institutional theory views organisations as operating within a social framework of norms, values, and taken-for-granted assumptions about what constitutes expectable or acceptable behaviour. Institutional theory is able to describe the reinforcement of the existing condition of legitimacy but is not sufficient to explain the changes in social expectation or the dynamics of legitimacy (Gray et al., 1996; Chen & Roberts, 2010).

An overlap also exists between stakeholder theory, especially in its managerial branch, and legitimacy theory (Azizul Islam & Deegan, 2008). According to Gray et al. (1995a, p. 67), “The different theoretical perspectives (legitimacy theory and stakeholder theory) need not be seen as competitors for explanation but as sources of interpretation of different factors at different levels of resolution.” However, compared with legitimacy theory, which sees the “environment” as a whole, stakeholder theory is concerned with the relationships between an organisation and its various stakeholders, who constitute the environment, and recognises that some stakeholder groups in the society are more powerful than other stakeholder groups (Chen & Roberts, 2010; Woodward et al., 1996). From the perspective of stakeholder theory, legitimacy is subjectively evaluated based on the value criterion of stakeholder groups, rather than the value system of the whole society (Chen & Roberts, 2010). Therefore, the focus of stakeholder theory is narrower than that of legitimacy theory (Azizul Islam & Deegan, 2008). Gray et al. (1997) argue that stakeholder theory, focusing on market forces, is reliant on organisation-centred legitimacy, which ignores the force of the whole society and social legitimacy.

3.1.3 Other relationships

The concept of accountability is explicitly or implicitly incorporated in agency, stakeholder, and legitimacy theories. Agency theory is mainly concerned with the relationship between company management and investors and emphasises accountability to financial stakeholders (Parker, 2005; Segrestin & Hatchuel, 2011). However, agency theory ignores the relationship between the company and other stakeholders. Stakeholder theory complements agency theory, and extends the relationship between management and investors to a wider range of stakeholders and emphasises accountability to all stakeholders (An, 2012; Liu, 2014). Legitimacy theory argues that a company should discharge accountability to society as a whole (Liu, 2014).

By connecting the concepts of signal and information asymmetry, signalling theory links to stakeholder theory and legitimacy theory (Albers and Günther, 2010; Hahn and Kühnen, 2013), although the information asymmetry concept is not included in stakeholder theory (An, 2012) and legitimacy theory (Liu, 2014). The existence of information asymmetry impairs the decision-making ability of stakeholders (Dilling & Caykoylu, 2019), intensifies conflicts of interests between managers and various stakeholder groups (Velte, 2018), and threatens the legitimacy of an organisation in society (An, 2012). Thus, a company has incentives to develop a signalling tool to mitigate information asymmetry between the organisation and various stakeholders to meet stakeholders’ expectations (Hill & Jones, 1992) as well as to mitigate information asymmetry between the organisation and the society as a whole to signal that it is complying with society’s cultural values and expectations (An, 2012). In addition, signalling theory connects with institutional theory (Fuhrmann, 2019). In order to respond to institutional pressures, a company will pursue a strategy to signal that it is conforming to the established patterns of other organisations.

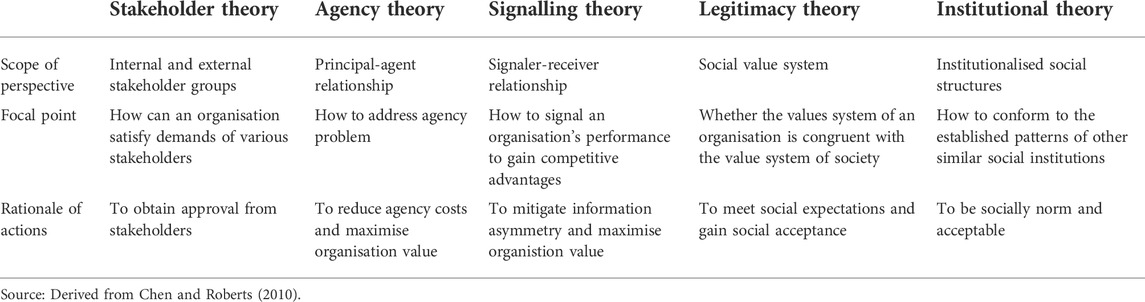

3.2 The integrated theoretical framework

Although each of the aforementioned five theories can be used to partly explain IR practices, any single one is inadequate if it is applied as the sole theoretical framework to elucidate IR practice (Fuhrmann, 2019). Thus, an integrated IR theoretical framework is developed on the basis of stakeholder, agency, signalling, legitimacy, and institutional theories. Some previous studies of corporate reporting practice have adopted the relevant theories to establish their theoretical framework. For example, Fernando and Lawrence (2014) establish a theoretical framework by combining stakeholder, legitimacy, and institutional theories to illuminate CSR reporting practices. Some IR studies have also attempted to use multiple theories to justify the rationale of IR practice. For example, institutional, legitimacy, and agency theories are used by Camilleri (2018) to shed light on IR practice, and institutional, signalling, stakeholder, and legitimacy theories are applied by Fuhrmann (2019) as a theoretical basis for interpreting a firm’s decision to release an integrated report.

An integrated IR theoretical framework is developed on the basis of the relationships between stakeholder, agency, signalling, legitimacy, and institutional theories (refer to Figure 1). Each theory incorporated in the integrated theoretical framework sees IR as having different functions, which are summarised in Figure 1. For instance, IR is a legitimation tool from the perspective of legitimacy theory, while IR is a monitoring mechanism from the perspective of agency theory. Each theory can be used to interpret the motivation for higher IR disclosure practices by organisations. For instance, the reason for higher IR disclosure practices by organisations is to gain legitimacy from society from the perspective of legitimacy theory, while it is to mitigate information asymmetry between principals and agents from the perspective of agency theory. Considering the theories are interrelated and underpin each other in explaining IR disclosure practices by organisations, the drivers for higher IR disclosure practices are integrated into three categories:

1) To mitigate information asymmetry between the organisation and all stakeholders

2) To signal superior quality, legitimacy and conformity to all stakeholders

3) To discharge accountability to all stakeholders.

Despite the three motivations for higher IR disclosure practices of organisations, there are also two explanations for lower IR disclosure practices. Specifically, IR induces both direct and indirect disclosure costs, which discourage firms from higher IR disclosure practices (Fuhrmann, 2019; Grassmann et al., 2019). Direct disclosure costs include the costs of preparing, disseminating, and auditing an integrated report (Admati & Pfleiderer, 2000; Wang et al., 2013). Indirect disclosure costs include unwillingness to set a disclosure precedent (Wang et al., 2013); higher volatility in the stock market (Bushee and Neo, 2000); and all proprietary costs (Wang et al., 2013; Fuhrmann, 2019; Grassmann et al., 2019), including competition costs (i.e., the possibility of losing competitive disadvantage), political costs (i.e., increased labour costs; intensified regulations), and litigation costs. For example, a company may be reluctant to report forward-looking information because such information may be used by its competitors, thus diminishing its competitiveness (Kılıç & Kuzey, 2018b). Also, releasing forward-looking information may incur litigation, which is another reason that a firm avoids disclosing such information (Kılıç & Kuzey, 2018b). It can be said that managers’ decisions on IR disclosure practices constitute a cost-benefit analysis process (Beattie & Smith, 2012; Wang et al., 2013). In other words, a firm will use IR only when the firm believes that the benefits of IR exceed the costs of IR (Kannenberg & Schreck, 2018).

3.3 Application of the integrated theoretical framework

The theoretical framework can be applied to guide the methodology of IR-related research. Firstly, from the perspective of signalling theory, if an explicit guideline for a company in terms of how to use IR to signal its superior quality is not given, wrong signalling may happen (An, 2012). Thus, when implementing IR in a jurisdiction, an explicit IR framework for local companies is required. Secondly, legitimacy theory and institutional theory suggest that firms’ disclosure decisions vary between countries; hence, the national characteristics of the country where a firm is resident need to be considered (Deegan, 2002; Baldini et al., 2018; Fuhrmann, 2019). Thus, when constructing the IR framework in a specific jurisdiction, its contextual factors, such as the political system, the cultural system, the legal system, and the economic system are taken into consideration, and a stakeholder-consultation approach is needed to be adopted.

Thirdly, stakeholder theory emphasises balancing the conflicting expectations of different stakeholder groups with regard to disclosures (Hasnas, 1998); therefore, it is necessary to identify the expectations of each stakeholder group about IR disclosures. Also, on the basis of legitimacy theory, some scholars propose that knowledge is needed about whether there are specific stakeholder groups who are more easily influenced by legitimising disclosures than others (Deegan, 2002; An, 2012; Liu, 2014); hence, analysing which stakeholder groups are sensitive to IR disclosures is important. Thus, in order to identify the expectations of various stakeholder groups about IR disclosures, and the sensitive stakeholder groups affected by IR disclosures, different weightings should be assigned according to the importance of different disclosures in stakeholders’ minds.

Fourthly, the legitimation and institutionalisation processes of IR are dynamic and change over time (Zilber, 2008; Ryan, 2011; Van Bommel, 2014; Deegan, 2018); therefore, the longitudinal approach can be used to examine the changes in IR disclosure practices by companies. Lastly, IR is still a totally new reporting format for many counties such as China (Briem and Wald, 2018; Kannenberg & Schreck, 2018). According to institutional theory, firms who are pioneers in adopting a new reporting format such as IR in one country would be considered as “organisational role models” for other firms in that country and are more likely to obtain external approval (Clegg & Hardy, 2005; Higgins et al., 2014; Hassan et al., 2019). Thus, how firms adapt to IR and how to implement the adoption of IR both within a country and within a company need to be considered.

The integrated theoretical framework can be used to make sense of the analysis and to provide reflections on the findings of the analysis. Firstly, the integrated theoretical framework can be applied to give meaning to the construction of a country-specific IR framework. Secondly, the integrated theoretical framework can be employed to shed light on the current status and development of IR disclosure practices by companies. Thirdly, the integrated theoretical framework can be adopted to develop hypotheses on factors influencing IR disclosure practices, the effect of IR disclosure practices and to interpret the findings. Lastly, the integrated theoretical framework can be used to interpret the perceptions of stakeholders on both the barriers to the adoption of IR and recommendations for IR implementation.

4 Discussion

The coherent understanding emerging from this paper assists in identifying organisational motivations in the adoption of IR. Prior literature on IR has not explicitly pointed out the fact that not all organisations adopt IR for the same reasons. Our findings in terms of the organisational motivations in the adoption of IR can be classified as external pressures, external benefits, and internal aspirations.

First, mitigating information asymmetry between the organisation and all stakeholders as well as signaling superior quality, legitimacy and conformity to all stakeholders can be attributed to external pressures and external benefits. Theoretically, a common feature of legitimacy theory, institutional theory and the managerial branch of stakeholder theory is the quest for legitimacy and responses to the corresponding external pressures (Berrone and Gomez-Mejia, 2009; Fernando and Lawrence, 2014). Signaling theory and agency theory seek for external benefits. Empirically, prior studies, based on legitimacy theory, institutional theory and the managerial branch of stakeholder theory, confirm that external pressures lead to the adoption of IR (García-Sánchez et al., 2013; Lai et al., 2016; Vaz et al., 2016; Ahmed Haji & Anifowose, 2017; Vitolla et al., 2019c). Moreover, a series of IR studies, based on signaling theory and agency theory, confirm that IR is able to provide external benefits for organisations, including lower agency costs (Pavlopoulos et al., 2017; Obeng et al., 2021; Sun, 2021), lower capital costs (e.g., Zhou et al., 2017), lower information asymmetry (e.g., Pavlopoulos et al., 2017), milder earnings management (e.g., Pavlopoulos et al., 2017), higher analysts’ forecast accuracy (e.g., Zhou et al., 2017; Perez, 2018) and higher firm value (e.g., Lee and Yeo, 2016; Barth et al., 2017; Pavlopoulos et al., 2019).

Second, discharging accountability to all stakeholders can be attributed to internal aspirations. Theoretically, the ethical branch of stakeholder theory suggests an internal intention (inner morality aspirations). Empirically, prior studies such as Robertson and Samy (2019) and Gerwanski (2020) verify that pursuing morality is one of the important motivations to prompt companies to adopt IR.

To sum up, organizations’ interest in adopting IR can be driven by an inherent desire for stakeholder accountability, economically motivated desires and quests for legitimacy, which suggests that internal intentions (inner morality aspirations) and external intentions (external incentives pursuing and pressures responding) are not mutually exclusive (Gerwanski, 2020). Our findings are in line with Robertson and Samy (2019) who identify that external pressures (such as legal requirements and informal rules), external benefits (such as economic benefits), and internal aspirations (such as moral and ethical behaviours) are rationales for IR adoption. Thus, the established conceptual framework allows researchers to analyse what actually kindles an organisation’s interest in releasing stand-alone integrated reports and choosing a certain IR disclosure practice — “doing good” (stakeholder accountability) and/or “doing well” (economically driven desires and quests for legitimacy significantly)?

5 Conclusion

This paper provides an integrated theoretical framework for the present study by integrating a series of theoretical traditions, comprising stakeholder theory, agency theory, signalling theory, legitimacy theory, and institutional theory. Each theory has its own features, although common concepts and differences exist between theories. By combining the features of IR, this integrated theoretical framework identifies the three drivers for companies to improve their IR disclosure practices (to mitigate information asymmetry between the organisation and all stakeholders; to signal superior quality, legitimacy, and conformity to all stakeholders; and to discharge accountability to all stakeholders). It then provides two reasons for limiting higher IR disclosure practices (direct and indirect costs). External benefits, external pressures, and internal aspirations are rationales for the decision of a company to release IR or to choose a certain IR disclosure practice.