95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Environ. Sci. , 01 June 2022

Sec. Water and Wastewater Management

Volume 10 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2022.863044

This article is part of the Research Topic Sustainable Sanitation- How Can We Improve Sanitation Systems in the Global South? View all 19 articles

Sheik Mohammed Shibl Akbar Chinna Mohideen1,2*†

Sheik Mohammed Shibl Akbar Chinna Mohideen1,2*† Shirish Singh2*†

Shirish Singh2*† Tanvir Ahamed Chowdhury3

Tanvir Ahamed Chowdhury3 Damir Brdjanovic1,4

Damir Brdjanovic1,4To achieve SDG 6.2.1 (a) on safely managed sanitation services, several financial flow models (FFMs) and business models for the sanitation value chain have been implemented in Bangladesh and elsewhere; however, there is limited research on financial viability and sustainability of business models. Bangladesh has attained 99% sanitation coverage, mostly with onsite sanitation systems; however, the country is facing a second-generation sanitation challenge, fecal sludge management, encompassing the entire sanitation chain. Kushtia Municipality in Bangladesh is entirely served by onsite systems; the fecal sludge emptying service is provided by the municipality, and the fecal sludge treatment plant is managed by a private entity. This study investigated sustainability of FFMs in Kushtia by using the financial, institutional, environmental, technical, and social (FIETS) sustainability approach and applying the financial flow simulator (eSOSView™) tool to analyze financial viability. Several criteria in each aspect of the FIETS approach were developed, scored, and validated by stakeholders to determine sustainability. The study found that the financial aspect is the most important criteria for sustainability and “modified parallel tax and discharge fee” is the most sustainable business model for Kushtia.

The Sustainable Development Goal 6 (SDG 6) established by the United Nations in 2015 as part of the 2030 agenda for sustainable development focuses to ensure availability and sustainability of water and sanitation for all (UN, 2015). SDG 6.2 (a) targets to attain safely managed sanitation services for all. At least 1.8 billion people from developing countries are users of onsite sanitation systems (OSS) such as septic tanks, pit latrines, and ventilated improved pits (Capone et al., 2021), and partially digested material accumulating in OSS is fecal sludge (FS) (Strande et al., 2014). Many developing countries are facing challenges with management of FS from OSS due to rapid urbanization, high population density, and increased and unplanned growth (Opel, 2012).

Bangladesh is a densely populated South Asian country that had attained 99% sanitation coverage with OSS (Islam et al., 2016). Negligence toward fecal sludge management (FSM) and FS discharge to open drains by the majority of households results in environmental and public health hazards (Al-Hafiz, 2017). There is an increasing attention to safe sanitation and FSM in Bangladesh post the announcement of the National Water Supply and Sanitation Strategy, 2014, for water and sanitation through partnerships with organizations to implement Citywide Inclusive Sanitation Engagement (CWISE) in various cities of the country (Kabir and Salahuddin, 2014), and business models were introduced for sanitation services. CWISE covers the sanitation value chain (SVC), which includes superstructure (toilet), containment, emptying, transport, treatment, and safe reuse or disposal.

The business model for FSM is a new approach to enhance business opportunities in the sanitation sector (Diener et al., 2014) and business model approaches pave a way for increased private sector participation in sanitation service provision, which is dominated by public utilities (Rao et al., 2016). The financial flow is one parameter of the business model approach in FSM, and the other parameters are service arrangement and contractual arrangements (CWAS, 2020). The financial flow approach is helpful for the city administration to understand the financial sustainability of FSM in their city. Financial flow models (FFMs) show different financial transfers occurring between stakeholders in a SVC. There are several FFMs implemented in several parts of the world, which are generalized into five models (Strande et al., 2014). Model 1: discrete collection and treatment model—household pays an emptying fee to the emptying and transport (E&T) provider to empty FS, and the E&T service provider empties and transports FS into the fecal sludge treatment plant (FSTP) and pays the treatment provider a discharge fee. The treatment provider produces reusable product at FSTP which is sold for a purchase price to the end-user. Model 2: integrated collection and treatment model—E&T and treatment and reuse are handled by a single entity in which emptying fee is paid by households and the purchase price by end-users. Model 3: parallel tax and discharge fee model—household pays emptying fee to the E&T provider and sanitation tax to the government. E&T pays discharge fee to the treatment provider and the treatment provider receives a purchase price from the end-user. From the sanitation tax, the government provides some budget support to the treatment provider. Model 4: dual licensing and sanitation tax model—similar to model 3 except that the discharge fee is replaced by the discharge license, which is paid to the government. Model 5: incentivized discharge model—this model is a modification of model 4 to incentivize the E&T service provider by providing a discharge incentive instead of paying a discharge fee or discharge license. A summary of these models along with pros and cons is presented in Table 1.

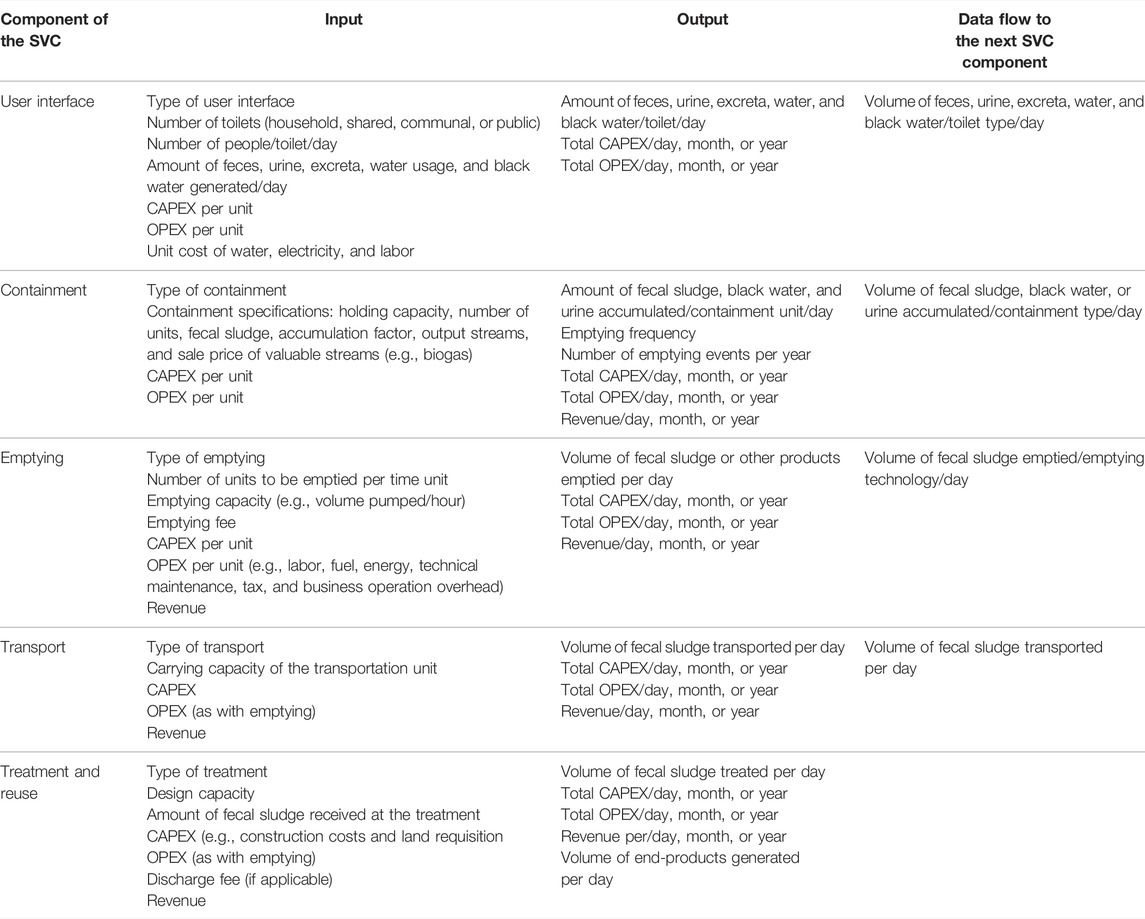

Among many financial decision support tools, most of the tools cover FS emptying and/or treatment and/or reuse and only a couple of tools cover the entire SVC. The FSM Technical and Financial Assessment tool focuses on the technical and financial viability of diverse options across emptying, transport, and treatment and reuse of SVC (Dey et al., 2016). The CLARA Simplified Planning Tool (SPT) compares the finances of alternatives for water supply and sanitation interventions in the early planning stage, which was targeted for a few African countries (Langergraber and Weissenbacher, 2014). The SaniPlan tool covers the entire SVC with water supply and solid waste management, which was developed for Indian municipalities/cities for improving service provision and offers a comprehensive financial planning including funding (Dey et al., 2016). Climate and Costs in Urban Sanitation (CACTUS) is a tool that aids authorities to make informed decisions on urban sanitation services at the city level considering the cost of “city-wide sanitation,” “climate,” and “welfare” (University of Leeds, 2022). The Citywide Inclusive Sanitation (CWIS) Costing tool was developed to monitor CWIS principles that focus on investing in safely managed sanitation services at the city level (World Bank, 2022). The tool analyzes capital expenditure (CAPEX) and operating expenditure (OPEX) for onsite and offsite technologies such as septic tanks or pipes that convey excreta to a treatment site at each component level. Despite the tool monitoring CAPEX and OPEX for sanitation systems, it does not indicate how revenue for sustaining sanitation services by the service provider can be incorporated. There is not a single tool that can analyze the impacts of different FFMs (as described earlier) in SVC except for the financial flow simulator tool (eSOS™) (Furlong et al., 2020). eSOS™ is an Excel-based decision support tool, which needs input data on the type of user interface, containment, transport, and treatment and upon entering mentioned input data, material flows are determined. Financial flows are linked to material flows and many charges are assessed on a volume or mass basis depending on charges levied by stakeholders in SVC. Financial flow in the tool displays a variety of financial parameter, that is, CAPEX, OPEX, revenue, profit or loss for each component of SVC and entire SVC to determine the financial viability of FFMs. A summary of input data, output, and linkages within SVC in eSOS™ is presented in Table 2. There is flexibility in adding modified FFMs based on material and financial flows in a city.

TABLE 2. Summary of input, output, and links to the next SVC component in eSOSView™ (Furlong et al., 2020).

There is a lack of information on financial transfers across the SVC despite a well-established SVC in Kushtia. Due to unavailability of information on financial transfers, the financial viability of the FSM business model could not be ascertained. Hence, this study was conducted in Kushtia Municipality with three main objectives: 1) to investigate current FSM practices to analyze existing FSM, 2) to study financial transfers to analyze the financial viability of existing FFMs, and 3) to evaluate various FFMs/business models to recommend a sustainable model.

Kushtia Municipality is a city in Khulna division and located in southwestern Bangladesh with a population of 418,312 in 2019 living in 93,582 households with an average household size of 4.4 and 33,250 holdings (holdings are property numbers in the city with one or more households living in one holding) (Kushtia Municipality, 2019). Based on monthly income, households are segregated in low-income (up to 117 USD), middle-income (117–588 USD), and high-income (more than 588 USD) households (Baki, 2014). The city is dependent on OSS such as septic tanks and pit latrines. FS emptying services are offered by the municipality with vacutugs and a private entity operates and maintains FSTP and runs a co-compost plant to produce co-compost from FS and municipal solid waste.

The study started with a detailed literature review of reports, documents, publications, books, and a collection of secondary data. Several unpublished data were also collected from stakeholders working in sanitation in Kushtia and reviewed. Primary data, both quantitative and qualitative were collected from key informant interviews and focus group discussions (Table 3). Joint stakeholder meetings (JSMs) were organized with support from the municipality comprising 30 participants—municipality officials, council members (elected representatives), representatives of household, sanitary hardware shop owners (private actors), FS emptiers, and FSTP operators. The first JSM was used to triangulate and validate data collected from primary and secondary sources. Strength, weakness, opportunities, and threat (SWOT) analysis is a strategic planning tool to assess the internal and external SWOT of stakeholders and context (Shikun et al., 2017; Shabanova et al., 2015) and was conducted in the study.

Input data including financial transfers are fed into the eSOS™ tool to analyze the financial viability of existing FFM and the five generalized FFMs and proposed FSM. The whole system approach for sustainability as used by the Dutch Water Alliance, which has five aspects of sustainability—financial, institutional, environmental, technical, and social (FIETS) (Galli et al., 2014) are used in the multi-criteria analysis for selecting a sustainable business model for the city.

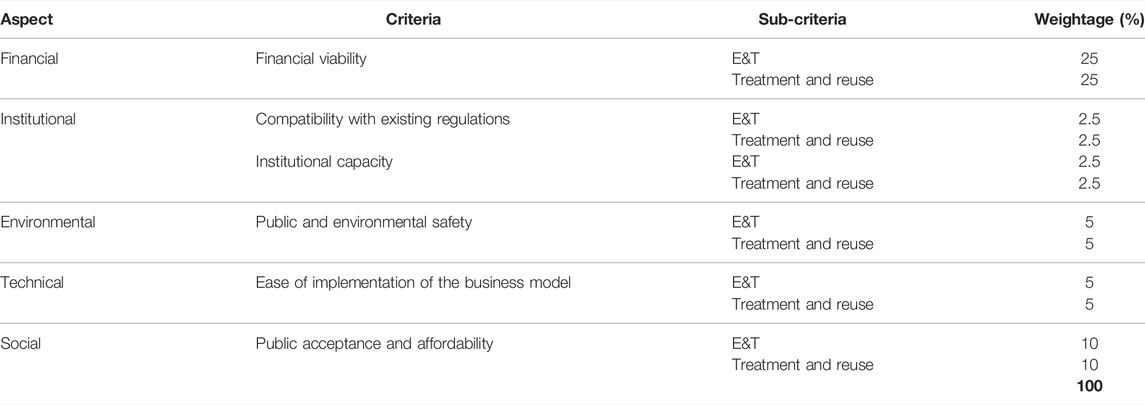

A second JSM was organized to share and discuss existing FFMs, the five generalized FFMs, and proposed FFMs and suggestions for weightage of all five aspects and their criterion for the multi-criteria analysis. Stakeholders were explained about the study and were asked to award weightage for each aspect and score for each criterion for the multi-criteria analysis. The weightage of each aspect and criterion was decided from discussions/feedbacks received during the meeting and is illustrated in Table 4.

TABLE 4. Criteria and weightage for multi-criteria analysis. Bold value is the total (sum) of values of the column i.e. weightage of each aspect totaling to 100%.

The study was formulated as per the Netherlands Code of Conduct for Research Integrity, 2018, and was supported by the Kushtia Municipality council. When this study was carried out, IHE Delft was in the process of establishing a research ethics committee, so no ethical approval was available. However, the authors are aware of the research ethics and all subjects involved in the study were informed about the purpose of the study and the consent was obtained from all participants of the study. The findings of the field study were shared with key stakeholders in JSM and later after completion of the study.

The study is limited to households in the study area and excludes financial flows from institutional and commercial holdings. The unavailability of some financial data has been adopted as suggested by stakeholders during JSMs.

In Kushtia municipality, more than 90% of the population have access to improved sanitation facilities (toilets), and their typology is presented in Table 5 (Chowdhury, 2018). OSS was prevalently used with 52.1% septic tanks and 47% pit latrines of volumes 15.33 and 2.58 m3, respectively (Al-Hafiz, 2017). Some low-income households are having toilets without containment, and excreta is directly discharged to nearby drains.

Kushtia Municipality offers on demand FS emptying service through vacutug of capacities 1 m3, 2 m3, and 4 m3 for a prescribed fee of 9.41 USD, 11.76 USD, and 14.12 USD, respectively. OSS are generally emptied in an interval of 4 years with some not emptied even in 12 years, which is similar to findings in Khulna, where OSS, having an average volume of 16.64 m3 in a septic tank and 1.96 m3 in a pit latrine, are generally emptied every 3 years and some even every 15 years (Singh et al., 2021). It was revealed that some OSS dispose liquid portion of FS into nearby open drains, which is a reason for holding FS for long and results in solidifying FS which is difficult to empty. One of the biggest challenges in FS emptying is difficulty in accessing mechanized emptying due to narrow roads which, in turn, leads to manual emptying. Emptied FS is transported to a FSTP at Baradi, 5 km away from the city, and an average distance traveled by a vacutug is about 10 km per trip.

Collected FS is emptied into drying beds of capacity 9 m3/day for dewatering and there are two units of drying beds. Percolate from the drying beds is pumped into a coco-pit filter for treatment and further treated in a pond. Dewatered sludge is co-composted with organic solid waste generated in the municipality. Co-compost contains a good amount of nutrients than chemical fertilizer, which is packaged and sold in fertilizer shops as well as procured by farmers directly. The co-compost is dried in open spaces due to the lack of space availability and the process of drying gets disrupted during rainy seasons. Similar to the co-composting facility in Devanahalli, India, segregation of municipal solid waste is the biggest problem faced in this FSTP, where plastic wastes are separated in the plant before the co-composting process (Rohini et al., 2019).

Four major stakeholders were identified in FSM in Kushtia municipality: 1) households, 2) Kushtia municipality, 3) private entities, and 4) farmers. Households are responsible for the construction of OSS including plumbing systems for the proper functioning of OSS and its operation and maintenance. It is also the responsibility of households to pay for emptying fees to the E&T service provider. Kushtia Municipality provides E&T services by scheduling suitable vacutugs on request from households, operates and maintains vacutugs, and monitors the performance of FSTP. A single private entity operates and maintains FSTP and produces and markets co-compost. Farmers are end-users and purchase co-compost and apply in agricultural fields. The results of the SWOT analysis of stakeholders are illustrated in Table 6.

It is evident that households are significant stakeholders that initiate SVC and create demand for FSM services. FSM regulations should be favorable for households to ensure the proper working of FSM and sustainability of financial and business model as the main contribution of FSM business is through fees paid by households. Kushtia Municipality is the responsible authority to regulate FSM services and currently providing the sole E&T service and monitoring of FSTP. Due to the absence of a dedicated unit/wing for FSM in the municipality, a lack of planning in FSM services and management has been observed, which could cause public and environmental health risks. The municipality should utilize its authority to create a FSM unit for proper FSM planning and regularizing FSM services and to create an enabling environment for the private sector to engage in FSM services. It is also important to provide inclusive services to low-income households, which lack access to mechanized emptying due to narrow roads. The private entity’s role in SVC is limited to treatment and reuse, which could potentially be included in E&T as well as to providing quality and timely FS E&T services. The efficiency of co-composting is affected as a result of limited space for drying co-compost in the FSTP. Although the private sector is collaborating with the Department of Agriculture and farmers, it seems that the current support is politically influenced and could have an impact in the case of a shift of power in politics. The smooth support from the department needs to be ensured together with increasing knowledge/awareness of the benefits of using co-compost and improved water management practices which could lead to a dedicated market for co-compost benefitting both private entities and farmers.

Existing FFM is a modification of the discrete collection and treatment model. The E&T service is provided by the municipality with an emptying fee (2.06 USD/m3), and there is no discharge fee. Treatment and reuse is provided by a private entity which pays yearly lease fee (license fee) of 588.4 USD/year to the municipality to operate the FSTP and produces co-compost. Financially, the private entity operates with revenue generated from the sale of co-compost at a price of 0.43 USD/kg. The FS flow and the financial flow of the existing model are shown in Figure 1.

For financial analysis, a sanitation tax (tax collected by the municipality to provide FS emptying service) of 2.35 USD/containment/year for high- and middle-income households and 1.17 USD/containment/year for low-income households was adopted after analyzing the user willingness to pay through focus group discussions and JSMs. Several other cities such as Dumaguete, Philippines, charges the sanitation tax of 12 USD/family/year (Asian Development Bank Institute, 2018); Sinnar, India, charges 4.05 USD/property/year (CWAS, 2020); and Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, charges 0.04 USD/m3/year (Water and Sanitation for the Urban Poor–WSUP, 2012). A discharge incentive of 149 USD/year for emptying service provider has been adopted in this analysis is significantly less than 5 USD/truck/trip in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, to prevent the illegal discharge of FS (SANDEC, 2006). Sanitation tax and discharge incentives could be varied to provide equitable, inclusive, and safe sanitation to all citizens in the municipality. The introduction of sanitation tax is welcomed by the residents of Wai and Sinnar (Mehta et al., 2019), since it reduces the desludging cost paid by the residents to desludging operators.

Since the CAPEX and OPEX of superstructure and containment lie with households and no revenues are generated, this component is ignored in the financial analysis. The CAPEX of superstructure and containment is 82,704,020 USD and OPEX is 793,082 USD per year. Financially, it incurs a loss but it benefits users by providing comfort, safety, and privacy contributing to good health.

Based on revenues of all vacutugs in Kushtia, an emptying fee of USD 2.06/m3 is calculated, which is collected from households by the E&T service provider (municipality) in the existing FFM. An emptying fee of Kushtia Municipality is lower than other Bangladeshi cities such as Jashore and Jhenaidah (Sarwar, 2019). CAPEX for E&T was funded by a UN agency and OPEX for E&T is calculated as 18,689 USD per annum and it comprises the cost of maintenance of vacutugs, fuel cost, and human resources in E&T. The financial analysis shows that E&T incur a loss of 4,435 USD per year in existing FFMs as shown in Table 7 and the loss is primarily due to low emptying fees. In contrast, globally E&T services are a profitable business in many cities due to higher emptying fees and higher trips, that is, Kigamboni, Tanzania (Masaninga, 2020); Jaipur, Delhi, Khulna, and Madurai (Chowdhry and Kone, 2012).

CAPEX was funded by a UN agency, and OPEX incurred by the private entity was 14,906 USD per year comprising lease fee, human resources, and maintenance of the FSTP. The financial analysis revealed that the treatment and reuse component of SVC has a profit of 534 USD per year in existing FFMs as shown in Table 7, which is similar to findings in Pokhara, Nepal (Furlong et al., 2020; Shrestha, 2018), whereas treatment plants in Jashore and Jhenaidah are not generating sufficient profit as they are not operating in full capacity (Sarwar, 2019).

In addition to the existing and five generalized FFMs described earlier, model 6 (Figure 2), which is a modified form of model 3 (Parallel Tax and Discharge Fee model), was adapted to the context of Kushtia. In this FFM, the municipality provides E&T service and households have to pay an emptying fee and yearly sanitation tax for the service. Treatment and reuse are provided by a private entity which operates primarily with revenue generated from the sale of end-product. The private entity pays a yearly lease fee (license fee) to the municipality to operate FSTP and produces co-compost, which is sold to the end-user. The biggest advantage of this FFMs is that the sanitation tax and lease fee is supportive for the municipality to sustain E&T service, whereas the biggest disadvantage is public might be reluctant to pay both emptying fee and sanitation tax. To overcome this disadvantage, the municipality has significantly reduced the E&T fee that households are currently paying.

From the financial analysis (Table 7), models 1, 3, 4, and 5 incur a loss in E&T as a result of lower E&T fees, whereas in financial analysis across SVC, models 3, 4, and 5 displayed a profit of 49,556 USD, 49,969 USD, and 49,861 USD, respectively, as a result of the combination of treatment and reuse revenue. The existing model and models 1 and 2 incurred a loss even after combining the revenue of E&T and treatment and reuse, which is due to the absence of sanitation tax. It is evident that model 6, which generated a net profit of 49,863 USD per year for E&T, 1,533 USD per year for treatment and reuse, and 50,439 USD for the entire SVC is the most profitable FFM for the municipality. Higher profit is due to the sanitation tax for E&T services in the municipality.

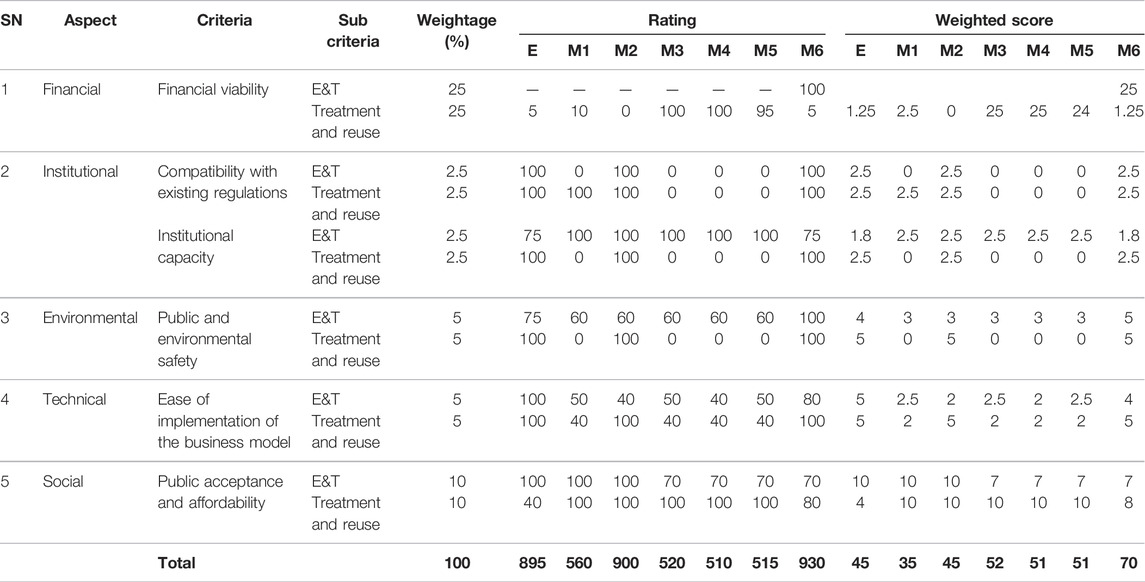

The FFMs were evaluated against FIETS criteria to determine a sustainable business model. The highest scoring model is the most sustainable model for the municipality. The description and weightage for each criterion were developed and finalized with inputs during JSM. All criteria were evaluated against 1) E&T and 2) treatment and reuse components. The models were rated between 0 and 100 for each of the FIETS criteria and converted to weighted scores as illustrated in Table 8.

TABLE 8. Multi-criteria analysis of FFMs (FIETS). Bold values are the total (sum) of values of the column i.e. weightage of each aspect totaling to 100%.

The financial viability of FFMs was the only criterion to evaluate the financial aspect, which is scored against the amount of net profit generated by FFMs. The model with highest net profit scored full marks, that is, 25 each in E&T and treatment and reuse sub-criteria and other models have scored relative to the highest scoring model. For E&T, model 6 scored 25 and all other models did not score any since net profit is negative. For treatment and reuse, models 3 and 4 scored 25 as a result of profit generated by sanitation tax and the existing model and model 6 scored the least with a score of 1.25 as net profit generated is lower than other models. Model 2 has not scored since it incurs a negative profit albeit providing comprehensive FSM services covering the entire SVC.

The institutional aspect is categorized into two criteria. The first criteria looked at “compatibility with existing regulations” (5% weightage), which examined the availability of supportive legal and regulatory framework for business model implementation. Without any legal and regulatory frameworks, it would be fairly difficult for institutions to implement a business model; hence models that have supportive legal and regulatory frameworks score high. For E&T, the existing models, models 2 and 6 scored 2.5 because of supportive regulations for the privatization of services and imposing sanitation tax up to 12% of holding tax. For treatment and reuse, all models except models 3, 4, and 5 scored 2.5 as there is no provision for imposing sanitation tax for treatment and reuse as it is handled by the private entity. Similarly, the discharge fee and discharge incentive are not being imposed for the same reason. The second criteria looked at “institutional capacity” (5% weightage), which assessed the availability of human resources and a dedicated unit for planning and management of FSM for the implementation of business model. For E&T, models 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 scored 2.5 as the private sector is providing services with adequate capacity and making a profit. The existing model and model 6 scored less with a score of 1.8 due to inadequate capacity in planning FSM and the absence of FSM wing in the municipality. For treatment and reuse, models 1, 3, 4, and 5 scored 0 as there is no separate FSM department to operate the FSTP and the existing model, models 2 and 6 scored 2.5 as it has dedicated man-power to operate the FSTP and reuse.

The environmental aspect was evaluated using the criterion of public and environmental safety, which assesses the impact of the business model on public and environmental safety. E&T evaluates safe hygiene practices that include use of personal protective equipment, provision of safe emptying services, and disposing of FS in FSTP. Models 1 to 5, where E&T is privately operated, provide prompt services being a profit-based entity. The lack of a monitoring agency and discharge incentive creates a high possibility of unsafe practices in E&T, and therefore these models scored 3. The existing model scored 4, higher than the former models as it is the public entity which provides services in a non-profit manner and it is monitored by the municipality. Models 1, 3, 4, and 5 scored 0 in terms of treatment and reuse as there is no FSM wing for operating FSTP. The private operated treatment and reuse will be environmentally safe as it is more profit-oriented; therefore, models 2 and 6 scored 5 in the environmental and public safety.

The criterion to evaluate this aspect was “ease of implementation of business model”, which is assessed by any changes required in the existing behavior of the public or stakeholders and practical difficulties in implementing the business model. With regard to E&T, models 2 and 4 scored 2, because finding an entity to provide comprehensive FSM services which are in loss and finding an entity to pay for discharge license is difficult. Models 1, 3, and 5 scored slightly higher than previous models with a score of 2.5 as the municipality has to develop a plan for a discharge fee and dumping license. Model 6 scored 4 as there are provisions for imposing sanitation tax for emptying and transport operated by the municipality but achieving maximum collection efficiency will require some time. The existing model scored 5 as implementing the existing model is not complicated. The municipality handling treatment and reuse part is difficult as there is no separate department for FSM; therefore, models 1, 3, 4, and 5 scored 2. The existing models, models 2 and 6, scored 5 as there are no difficulties with the treatment and reuse part of these models.

In the social aspect, the criterion of “public acceptance and affordability” of FSM services was used. People will accept the business model when it is affordable and it was observed that the public is more concerned about E&T and not much for treatment and reuse. For E&T, the existing model and models 1 and 2 scored 10, as these do not include any additional charge to public, whereas models 3, 4, 5, and 6 scored 7 as they add sanitation tax which is an additional expenditure for households. For treatment and reuse, all models scored 10 as it does not have a direct impact on the affordability for the public.

The financial flow simulator (eSOSView™) tool could be applied to determine financial viability of individual components as well as entire SVC. The financial analysis of existing FFMs in Kushtia revealed that it is financially unviable, incurring a loss of 3,901 USD per year. While exploring other FFMs, it showed that the modified parallel tax and discharge fee model generates the highest net profit of 51,396 USD per year considering the entire SVC (49,863 USD per year for E&T and 1,533 USD per year for treatment and reuse). It is evident that sanitation tax and discharge incentive aid service providers in attaining financial sustainability. The eSOSView™ tool could be tailored to determine financial viability of existing FFMs in addition to the generalized five FFMs. Financial viability is not adequate to determine a sustainable business model; hence, the FIETS sustainability approach was adapted to determine a sustainable FSM business model for Kushtia municipality. Criteria and weightage for each of the FIETS approaches could be developed and customized as per the existing situation and validated by relevant stakeholders. The study found out that the financial aspect remained the dominant criteria with 50% weightage, and due to this reason, the modified parallel tax and discharge fee model, which generated the highest net profit, turned out to be a sustainable business model for Kushtia.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: https://ihedelftrepository.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/masters1/id/315036/rec/1.

The ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

SA: conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, and writing—original draft. SS: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, and supervision. TC: conceptualization, writing—review and editing, and supervision. DB: conceptualization, writing—review and editing, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition.

The study was a part of MSc research supported by the “Accelerating the Impact of Education and Training of Non-Sewered Sanitation” project financed by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (OPP1157500).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Al-Hafiz, N. (2017). Study on Faecal Sludge Management in Kushtia Municipality and its Future Development and Sustainability. MSc thesis. Khulna, Bangladesh: Khulna University of Engineering & Technology.

Asian Development Bank Institute (2018). Spillover Effects from Fecal Sludge Management: Dumaguete City [Video]. YouTube. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XAIwcJvKEvs (Accessed at 11 16, 2021).

Baki, A. A. T. M. (2014). Socio-Economic Impacts of Gorai River Bank Erosion on People: A Case Study of Kumarkhalli, Kushtia. M.A Thesis Inst. Gov. Stud. (IGS). Dhaka, Bangladesh: BRAC University.

Capone, D., Chigwechokha, P., de Los Reyes, FL., Holm, RH., Risk, BB., and Tilley, E. (2021). Impact of Sampling Depth on Pathogen Detection in Pit Latrines. PLOS Neglected Trop. Dis. 15 (3), e0009176. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0009176

Center for Water and Sanitation (CWAS) - CEPT University (2020). Policy Brief - Financing and Business Models for Fecal Sludge and Septage Management for Urban India [Online]. Available at https://pas.org.in/Portal/document/UrbanSanitation/uploads/Policy_brief-Financing_and_business_models_FSSM_22.7.2019.pdf (Accessed at 11 07, 2021).

Chowdhry, S., and Kone, D. (2012). Business Analysis of Fecal Sludge Management: Emptying and Transport Services in Africa and Asia. Report. The United States of America: Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Chowdhury, M. R. (2018). An Endline Study to Assess Faecal Sludge Management of Residential Premises in Selected Southern Cities of Bangladesh. Report. Bangladesh: SNV Netherlands Development Organization.

Dey, S., Patro, S. A., and Rathi, S. (2016). Centre for Study of Science, Technology and Policy (CSTEP). Bengaluru, India:Sanitation Tool Compendium. Available at: https://www.cstep.in/drupal/sites/default/files/2019-01/CSTEP_RR_Technology_Options_for_the_Sanitation_Value_Chain_Compendium_2016.pdf(Accessed on 09 24, 2020).

Diener, S., Semiyaga, S., Niwagaba, B. C., Muspratt, A. M., Gning, J. B., Mbeguere, M., et al. (2014). A value proposition: Resource recovery from faecal sludge—Can it be the driver for improved sanitation?. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 88, 32 38. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2014.04.005

Furlong, C., Singh, S., Shrestha, N., Sherpa, M. G., Lüthi, C., Zakaria, F., et al. (2020). Evaluating Financial Sustainability along the Sanitation Value Chain Using a Financial Flow Simulator (eSOSView™). Water Sci. Technol. 82 (11), 2220. doi:10.2166/wst.2020.456

Galli, G., Nothomb, C., and Baetings, E. (2014). Towards Systemic Change in Urban Sanitation, Working Paper. Netherlands: IRC WASH.

Islam, R., Saha, U. K., Mamun, A. A., Brosse, N., and Stevens, L. (2016). Implications of Inappropriate Containment on Urban Sanitation and Environment: a Study of Faridpur, Bangladesh. Paper presented at the 39th WEDC International Conference, Ghana 2016.

Kabir, A., and Salahuddin, M. (2014). A Baseline Study to Assess Faecal Sludge Management of Residential Premises in Selected Southern Cities of Bangladesh. Report. Bangladesh: SNV Netherlands Development Organization.

Kushtia Municipality (2019). Municipality Citizen Charter. Kushtia, Bangladesh: Kushtia Municipality.

Langergraber, G., and Weissenbacher, N. (2014). Introduction to CLARA. Sustain. Sanit. Pract. 19, 5–7.

Masaninga, B. M. (2020). Development of a Sustainable Business Model for Faecal Sludge Management, A Case of Kigamboni District, Dar Es Salaam. MSc thesis. Delft, Netherlands: IHE Delft Institute for Water Education.

Mehta, M., Mehta, D., and Yadav, U. (2019). Citywide Inclusive Sanitation through Scheduled Desludging Services: Emerging Experience from India. Front. Environ. Sci. 7, 188. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2019.00188

Opel, A. (2012). Absence of Faecal Sludge Management Shatters the Gains of Improved Sanitation Coverage in Bangladesh. Sustain. Sanit. Pract. 2012 (13), 4–10.

Rao, K. C., Kvarnström, E., Di Mario, L., and Drechsel, P. (2016). Business Model for Faecal Sludge Management. Colombo, SriLanka: International Water Management Institute (IWMI). CGIAR Research Program on Water, Land and Ecosystems WLE. 80p (Resource Recovery and Reuse Series 6).

Rohini, P., Gagana, S., and Girija, R. (2019). Findings from Cocomposting Operations at Fecal Sludge Treatment Plant (FSTP), Devanahalli, India, Proceedings of FSM 5–5th International Fecal Sludge Management Conference, Capetown, South Africa.

SANDEC (2006). Urban Excreta Management: Situation, Challenges, and Promising Solutions, Proceedings of the 1st International Fecal Sludge Management Policy Symposium and Workshop, . Dakar, Senegal.

Sarwar, R. M. (2019). Funding Gaps & Barrier Analysis and Identification of Possible Financial Resources for Fecal Sludge Management (FSM) Services for SNV Netherlands Development Organisation. Report. Dhaka, Bangladesh: SNV Netherlands Development Organisation.

Shabanova, L. B., Ismagilova, G. N., Salimov, L. N., and Akhmadeev, M. G. (2015). PEST- Analysis and SWOT- Analysis as the Most Important Tools to Strengthen the Competitive Advantages of Commercial Enterprises. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 6 (3), 705–709. doi:10.5901/mjss.2015.v6n3p705

Shikun, C., Lei, Z., Mingyue, Z., Xue, B., Zifu, L., and Mang, H. (2017). Assessment of Two Fecal Sludge Treatment Plants in Urban Areas: Case Study in Beijing. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 10 (3), 237–245. doi:10.3965/j.ijabe.20171003.3067

Shrestha, N. (2018). Optimisation of FSM Business Model in Pokhara, Nepal with an Emphasis on Fecal Sludge Entrepreneurs. MSc Thesis. Delft, Netherlands: IHE Delft Institute for Water Education.

Singh, S., Gupta, A., Alamgir, M., and Brdjanovic, D. (2021). Exploring Private Sector Engagement for Faecal Sludge Emptying and Transport Business in Khulna, Bangladesh. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 18 (5), 2755. doi:10.3390/ijerph18052755

Strande, L., Ronteltap, M., and Brdjanovic, D. (2014). Fecal Sludge Management: Systems Approach for Implementation and Operation. London: IWA Publishing, The United Kingdom.

UN (2015). Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, United Nations, New York, USA. Available at: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_70_1_E.pdf (Accessed 16 May, 2020).

University of Leeds (2022). Climate and Costs. Available at: http://cactuscosting.com/(Accessed on 03 31, 2020).

Water and Sanitation for the Urban Poor – WSUP (2012). Sanitation Surcharges Collected through Water Bills: a Way Forward for Financing Pro-poor Sanitation? Discuss. Pap. Available at: https://www.wsup.com/content/uploads/2017/08/DP004-ENGLISH-Sanitation-Surcharges.pdf (Accessed on 03 31, 2022).

World bank (2022). CWIS Costing and Planning Tool. Available at: http://200.58.79.50/fmi/webd/CWIS%20Planning%20Tool%201_4 (Accessed on 03 31, 2020).

Keywords: fecal sludge management, financial flow models, financial viability, business model, Kushtia

Citation: Akbar Chinna Mohideen SMS, Singh S, Chowdhury TA and Brdjanovic D (2022) Application of Financial Flow Simulator (eSOSView™) for Analyzing Financial Viability and Developing a Sustainable Fecal Sludge Management Business Model in Kushtia, Bangladesh. Front. Environ. Sci. 10:863044. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.863044

Received: 26 January 2022; Accepted: 19 April 2022;

Published: 01 June 2022.

Edited by:

Shikun Cheng, University of Science and Technology Beijing, ChinaReviewed by:

Digbijoy Dey, IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre, NetherlandsCopyright © 2022 Akbar Chinna Mohideen, Singh, Chowdhury and Brdjanovic. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sheik Mohammed Shibl Akbar Chinna Mohideen, c2hpYmxha2JhckBnbWFpbC5jb20=; Shirish Singh, cy5zaW5naEB1bi1paGUub3Jn

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.