95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Environ. Sci. , 28 January 2022

Sec. Biogeochemical Dynamics

Volume 10 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2022.811375

This article is part of the Research Topic Physical and Biogeochemical Processes Driving Methane Sources, Sinks and Emissions in Aquatic Systems: The Past, Present and Future under Global Change View all 24 articles

This study traces the pathways of dissolved methane at the Eurasian continental slope (ECS) and the Siberian shelf break based on data collected during the NABOS-II expedition in August-September, 2013. We focus on the sea ice-ocean interface during seasonal strong ice melt. Our analysis reveals a patchy pattern of methane supersaturation related to the atmospheric equilibrium. We argue that sea ice transports methane from the shelf and that ice melt is the process that causes the heterogeneous pattern of methane saturation in the Polar Mixed Layer (PML). We calculate the solubility capacity and find that seasonal warming of the PML reduces the CH4 storage capacity and contributes to methane supersaturation and potential sea-air flux in summer. Cooling in autumn enhances the solubility capacity in the PML once again. The shifts in the solubility capacity indicate the buffering capacity for seasonal storage of atmospheric and marine methane in the PML. We discuss specific pathways for marine methane and the storage capacity of the PML on the ECS as a sink/source for atmospheric methane and methane sources from the Siberian shelf. The potential sea-air flux of methane is calculated and intrusions of methane plumes from the PML into the Cold Halocline Layer are described.

The Arctic holds large natural sources of methane (CH4), especially the Siberian shelf, which is considered as potential sources of this greenhouse gas for the atmosphere. The release of CH4 from these shallow shelf seas threaten to enhance the current Arctic amplification of global warming (IPCC, 2019). Indeed, warmer seawater as a positive feedback on the climate is discussed to displace gas hydrate stability zones and increase the thawing of subsea permafrost, which acts as a physical barrier to ascending gas (Reagan and Moridis, 2008; Shakhova et al., 2019). Recent acoustic surveys on shelves and along continental slopes revealed significant CH4 emissions, triggered by an increasing number of submarine gas seepages (Westbrook et al., 2009; Baranov et al., 2020; Chuvilin et al., 2020). These assessments of potential CH4 release mainly focused on the changes in the submarine CH4 storage system (Shakhova et al., 2010, Shakhova et al., 2014; Berchet et al., 2016). Based on these methodological approaches, bottom-up flux CH4 estimations are strongly imbalanced related to top-down flux estimations (AMAP, 2015), revealing that either the release at the submarine-marine interface or the sea-air CH4 fluxes is overestimated.

Actually, calculations based on the level of CH4 super-saturation in surface water related to the atmospheric equilibrium disregard the effects of sea ice and the water transformations coupled to the sea ice cycle on the pathways of CH4 (Damm et al., 2018). According to recent studies, the transport of shelf-sourced CH4 by sea ice is a driving mechanism causing the patchy appearance of CH4 excess in surface waters detected in different Arctic regions (Damm et al., 2015, Damm et al., 2018; Verdugo et al., 2021). Consequently, an assessment of the current sink capacities of certain regions and water masses in the Arctic Ocean is urgently needed to better simulate future climate scenarios.

In the last few decades, Arctic sea ice has sharply declined (Screen and Simmonds, 2010). The longer sea ice-free seasons (Markus et al., 2009; Günther et al., 2015) will have significant consequences for the CH4 cycle, while the elongated period for a potential net sea-air exchange is just one possibility. Intensive sea ice melt causes an increasing contribution of fresh water in surface waters that dilutes the CH4 excess. Eventually, warming will amplify the water stratification, and restrict CH4 fluxes into the atmosphere. Water stratification is known to favor lateral CH4 transport, which in turn enables CH4 oxidation in the water column (Mau et al., 2013; Gentz et al., 2014; Myhre et al., 2016; Mau et al., 2017; Silyakova et al., 2020; Damm et al., 2021).

Moreover, changes of temperature and salinity in surface water, controlling the solubility and eventually the storage capacity for CH4, needs to be considered in assessments of the current CH4 budget. The Eurasian continental slope (ECS) is a key Arctic region to study this complexity of marine CH4 pathways and the potential sink capacity of Arctic surface water. The surface water at the ECS comprises the Polar Mixed Layer (PML) on top and the salinity-stratified Cold Halocline Layer (CHL) underneath. In summer, the PML is formed by sea ice melt and Siberian River runoff (Rudels et al., 1996). In winter, ice formation in leads and polynyas alters the characteristics of the PML (Dmitrenko et al., 2009; Krumpen et al., 2011; Iwamoto et al., 2014). The CHL is formed via interaction between inflowing Atlantic water and sea ice (Rudels et al., 2004). The CHL remains close to the Siberian continental slope, receives inflows from surrounding shelves, and is additionally modified through mixing with the PML (Alkire et al., 2017). Both water masses link the shallow shelf with the ECS and highlight the role of the shelf-basin exchange for the validation of the CH4 sink capacity.

In this study, we provide a first assessment of the seasonal storage capacity of the PML on the ECS. Based on data collected along cross-slope sections in late summer 2013 we point to the seasonal buffer capacity of the PML, which might influence the CH4 flux. We discuss the ability of the ECS as a sink for CH4 under the conditions of current sea ice retreat. Further, we describe the formation of CH4 plumes in the sea ice-influenced PML during the period of pronounced seasonal ice melt and their mixing into the CHL. We show that the CH4 plumes in the PML on the ECS are induced by the melt of mainly estuarine ice.

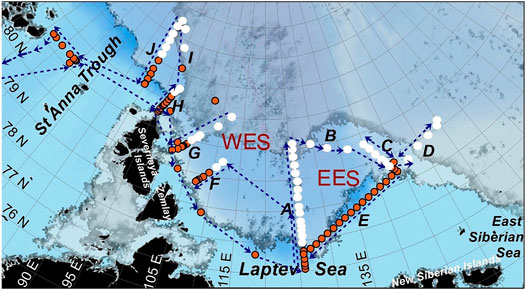

We used CH4, total alkalinity and thermohaline observations collected at ten sections (Figure 1) over the Eurasian continental slope (ECS) of the Arctic Ocean from the St. Anna Trough to the East Siberian Sea during the Nansen and Amundsen Basins Observational System (NABOS, https://uaf-iarc.org/NABOS/) cruise onboard R/V “Akademik Fedorov” from August to September, 2013.

FIGURE 1. Sea ice concentration [University of Bremen, (Spreen et al., 2008)] on August 15th (light grey/transparent) and September 15th (dark grey/transparent) is shown together with sampling sites in open water (red) and ice-covered (white) regions. Blue arrows indicate the track of the R/V “Akademik Fedorov”.

In order to determine the pathways and source regions of the ice along the sampling sections, we utilized the Lagrangian ice tracking tool, ICETrack. ICETrack makes use of low-resolution sea ice motion and concentration products and has been widely used in previous studies to identify age and origin of sea ice, as well as conditions along pathways (e.g. Belter et al., 2021; Krumpen et al., 2021). A comparison of the satellite-based motion estimates of ICETrack with buoy data has shown that the deviation between real and virtual tracks is rather small (60 ± 24 km after 320 days, Krumpen et al., 2020). For an in-depth method, data product and setup description, we refer to Krumpen et al., 2019).

Profiles of salinity and temperature in the water column were obtained using a conductivity–temperature–depth (CTD) system. The principal device used, was a Sea-Bird SBE911. At selected CTD station a 24-Niskin bottle rosette was used to collect the water samples for СH4 and total alkalinity (TA) analysis every 10 m along the top 100 m. Under heavy ice condition sampling was carried out from fractures or leads.

Samples for CH4 measurements were collected in 30, 100, 200 ml glass vials, taking care to avoid entrainment of bubbles while filling bottles, alkalized up to pH 12, then sealed with rubber stoppers and aluminum caps. To avoid the risk of contamination samples were collected first followed by TA. CH4 samples were stored in a refrigerator at 4° in the darkness until measuring in the land laboratory within 1 month after the cruise. CH4 concentrations were measured by using a gas chromatograph with a flame ionization detector (Shimadzu, GA-8A) with an instrumental precision 1%. The analytical error for measurement was 3%.

The CH4 saturations with respect to atmospheric equilibrium were calculated by applying the equilibrium concentration of CH4 in sea water with the atmosphere as function of temperature and salinity (Wiesenburg and Guinasso, 1979). We used an atmospheric mole fraction of 1.91 ppm, i.e. the monthly mean from September, 2013 (Data provided by NOAA Global sampling networks, sampling Hydrometeorological Observatory of Tiksi, http://www.esrl.noaa.gov).

The fluxes (F, nMol/m2 day) of CH4 across the air-sea interface were calculated in accordance to Wanninkhof (1992), using the equation

where Kw is the gas transfer velocity for CH4, Cw is the measured CH4 concentration in surface water, Ca is the equilibrium concentration of CH4 at surface water temperature and salinity calculated using the measured CH4 atmospheric mixing ratio and the Bunsen solubility coefficient taken from Wiesenburg and Guinasso, 1979. We have estimated Kw depending on wind speed (u) as described in Wanninkhof (1992):

Following Wanninkhof (1992), the appropriate Schmidt number (Sc) for CH4 was calculated using the surface water temperature dependent polynomial relationship.

The relationship between TA and salinity was used to identify the freshwater fractions of sea ice melt or estuarine ice melt waters in the PML (Macdonald et al., 2002; Yamamoto-Kawai et al., 2005; Fransson et al., 2009; Alkire at al., 2019). For TA samples were collected into borosilicate glass flasks (125-ml) pre-treated with saturated mercuric chloride solution (200 µL); the bottles were sealed and stored until following analysis, which was carried out on board by an automated open-cell potentiometric titration (Haraldsson et al., 1997), with precision of ±1 µmol/L.

Our first five stations near the ice edge covered a route ∼80 miles apart the eastern Laptev Sea shelf break for the August 24–26th period. Section A (Figure 1, along 126°E longitude) was carried out August 27–28th. No ice was present at the southern stations while mid and northern stations were sampled in an area with ice concentration >90 and 70–80%, respectively. Ice thickness ranged between 70 and 100 cm at the mid stations and 40–60 cm at the northern stations. The ice was first-year ice, substantially rotten and melted from below. For August 29–31st, three northern stations at section C were visited before the termination of sampling due to a consolidated heavy ice pack. Southern stations along the ice edge, were occupied on August 31st. On the next day, the stations along the ice edge towards section D were done. At ∼153°E the thickness of the heavy consolidated pack ice reached 2 m. For September 4–6th section E was carried out. On September 8th, we started section F (crossing the Laptev Sea slope at 110°E). On September 10th, section F was interrupted at the middle of the slope by storm conditions. More specifically, the wind speed exceeded 18 m/s and the wave height exceeded 3 m. Work at section G (105°E) started in the marginal ice zone at the northern stations and was finalized at Severnaya Zemlya shelf on September 13th. The same day, we sampled section H at 95°E. Due to the presence of heavy pack ice, section I was started at 84°30′N and, interrupted by a storm, on September 16th. On September 17th we resumed sampling on section J along 90°E. However, a strong storm prevented sampling at the upper slope points. On September 18th and, 19th we sampled the final section across St. Anna Trough.

A typical vertical structure of surface waters in the Eurasian sector of the Arctic Ocean consists of two layers–the Polar Mixed Layer (PML) and the Cold Halocline Layer (CHL) (Alkire et al., 2017).

The PML extends from the ocean surface to the ∼20–55 m depths, and is characterized by vertical uniform distributions of temperature and salinity. Following Jones (2001), the base of the PML is associated with salinities ≤33 psu, but a wide range of temperatures. In line with that, in summer, 2013 the temperature of the PML varied between −1.78 and 2.51°C in the ice-free areas and between −0.137 and −1.781°C in the areas covered by sea ice.

Below the PML, strong vertical gradients of salinity accompanied by negligible gradients of temperature and a relatively weak T–S slope form the CHL. Strong salinity gradients in the CHL suggest the increased density stratification that suppresses diapycnal mixing between the upper and intermediate ocean layers (e.g., Rudels et al., 1996). In 2013, the CHL was localized between 20 and 80 m depths, slightly deepening in the eastern sector of the Makarov Basin. The CHL salinities varied between 33.0 and 34.0 psu (e.g., Alkire et al., 2017), whereas the temperature range was from −1.80°C to −0.1°C.

According to regional patterns, in our study, we divided the research area into two sectors: western and eastern ECS.

The western sector (further the western sector of the ECS, WES) comprises the sections located from the St Anna Trough up to the section A at 126°E (Figure 1, Sections A, F, G, H, I, J.). The eastern sector (further the eastern sector of the ECS, EES) comprises sections located to east from the Lomonosov Ridge (Figure 1, Sections B, C, D, E).

In the PML the highest CH4 concentrations detected were 5.81 nmol/L, which reflected an average CH4 super-saturation (154%) with respect to the atmospheric equilibrium. The mean CH4 concentrations increased from 4.03 nmol/L (standard error, SE = 0.18) in the WES up to 4.25 nmol/L (mean, SE = 0.12) in the EES. This corresponded to a slightly increase of the CH4 super-saturation from 105 to 107% in the WES and EES, respectively. Unlike the WES, where CH4 saturation was the same for the ice-covered and ice-free areas, in the EES, CH4 concentration at ice-free stations were 4.23 nmol/L (mean, SE = 0.19) that corresponded to a CH4 super-saturation of 110.2%. At the ice-covered stations, the mean CH4 concentration was 4.44 nmol/L (SE = 0.18), which corresponded to a CH4 super-saturation of 109% at ice-covered stations.

In the CHL the CH4 concentrations increased from 3.49 nmol/L in the WES to 5.69 nmol/L in the ESL. Those corresponded to CH4 saturation from 96.7 to 145%. In the WES, the mean CH4 concentrations were 4.13 nmol/L (SE = 0.19) corresponding to a CH4 super-saturation of 104%. In the EES mean CH4 concentration was 4.35 nmol/L (SE = 0.19), which correspond to a CH4 saturation of 108%.

When entering through the St Anna Trough, pronounced cooling and freshening by sea ice melt created the PML (Rudels et al., 1996). The direction of the PML circulation is supposed to correspond to the current of warm saline AW underneath, mainly following the coastline eastward (Carmack et al., 2016). The thickness of the PML enhanced from ∼20 m at 90°E to ∼50 m at 125°E.

In mid of August ∼85% of the research area was covered by sea ice while, sea ice progressively reduced to less than ∼10% in mid of September. During sampling roughly 15% of the stations on the WES (Figure 1) and, 46% of the stations on the EES were still ice covered. The salinity profiles of the PML clearly reflected the different stages of sea ice melt (Figure 1, Figure 4, Figure 6). As the ongoing melt also affects the CH4 solubility capacity (SC), we discuss the sea ice effects on the CH4 saturation with respect to the atmospheric equilibrium in detail.

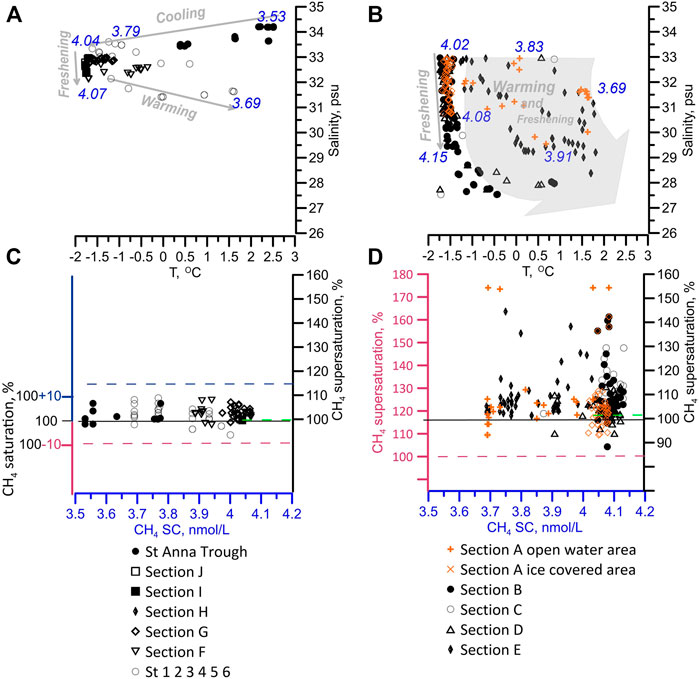

The cooling of the warm inflowing surface water and coexisting freshening due to sea ice melt or meteoric water enhanced the SC from 3.53 to 4.07 nmol/L in the PML from west to east (Figures 2A, B).

FIGURE 2. The effect of the CH4 solubility on the level of CH4 saturation, related to the atmospheric equilibrium in the PML. The (A,B) gives the CH4 solubility concentration (blue numbers) calculated in relation to the water temperature and salinity. The arrows show the dominant effect of either cooling or warming and freshening in the WES (A), and EES (B). The (C,D) shows the shift related to the saturation induced by changing solubility (dashed lines): in blue (cooling), in green (freshening), and in red (warming) in the WES (C) and EES (D). The shift in saturation forced by predominantly by warming (left red axes) consisted in real saturation (right black axes) (D). Orange symbols indicate the reference section A. In the WES the enhanced solubility masked the CH4 supersaturation caused by marine sources. In the EES, CH4 supersaturation is clearly induced by marine CH4 sources.

In the ice-covered PML in the WES, the SC increased at ∼13% mainly by cooling of the water down to near the freezing point (−1.718°C; S 32.963 psu), while the freshening effect remained negligible (<0.1%, ΔS = 0.838 psu). That increase in SC resulted in a slightly CH4 under-saturation related to the atmospheric equilibrium (Figure 2).

In the ice-covered PML in the EES, the water temperature was mostly near the freezing point, while the cooling effect on the SC was still sustained, reflected by the under-saturation at some stations. That pointed to a restricted air-sea exchange mainly hampered by the ice coverage.

By comparison, in the ice-free PML in the WES, a seasonal warming up to 1.608°C, resulted in ∼10% less SC, finally reflected in under-saturation down to ∼90% (Figure 2).

Freshening by sea ice melt increased the SC from 4.02 to 4.08 nmol/L at northern ice-covered stations (Figures 2A, C), resulted in negligible increase in the SC (∼1%) compared to the effect of simultaneously occurring warming. Under consideration of the variabilities in saturation by changes in the SC, we observed CH4 supersaturation up to 153% caused by additional CH4 discharged from marine sources.

A combined effect of freshening and warming was observed in the EES including the reference section A, which served as a boundary between the WES and EES (Figures 2B, D). The prevailing impact of warming to the decreased SC (11%) was attributed for all shelf break ice-free stations. By comparison, we observed the largest freshening, in the eastern EES, at the section C, increasing the SC to 4.15 nmol/L, which corresponded to a plus by ∼2%.

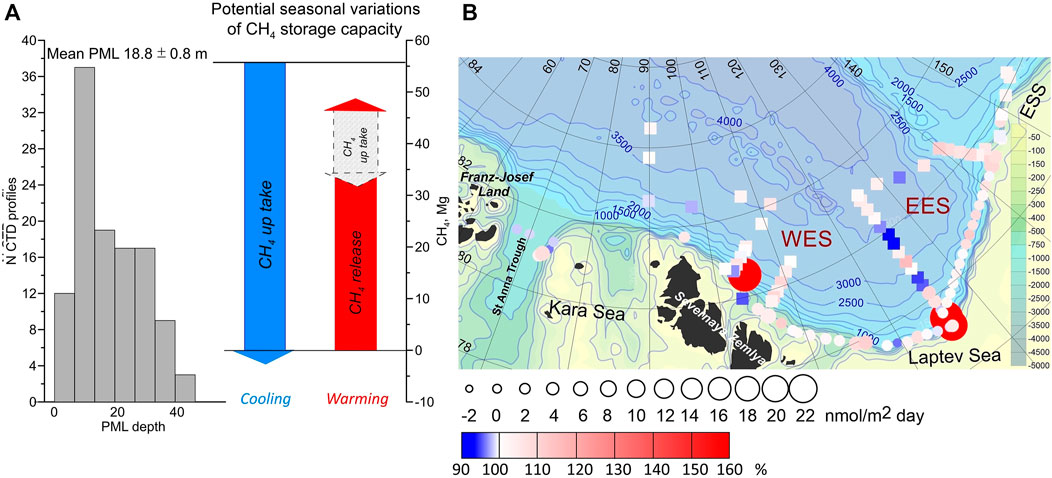

The variation in the SC revealed the significance of surface warming and coherent freshening due to sea ice melt to the level of CH4 saturation. Remarkably, the cooling of warm inflowing water in the WES results in an enhanced potential sink capacity for either atmospheric or marine CH4 sources. However, this potential sink capacity seasonally shrinks by ice melt and subsequent warming of the melt water, while especially the degree of warming in summer, triggers the PML at the ECS switches to acting as a potential source for atmospheric CH4 (Figure 3A).

FIGURE 3. Mean PML depths and the potential CH4 storage capacity (A); CH4 flux and saturation related to the atmosphere (B). (A) The blue arrow shows the potential CH4 up-take caused by cooling. Cooling takes place when the water mass enters the polar region and in autumn during the freeze up. The red arrow shows the potential release of CH4 caused by warming, e.g. as consequences of sea ice retreat. Freshening partly counterbalances the release capacity. The discrepancy between both arrows are caused by variations in the SC calculated with different temperatures in WES and ESS (Figure 2). (B) СН4 saturation related to the atmospheric equilibrium is shown by colors. Squares and circles show ice-covered and ice-free stations, respectively. The size of circles is related to potential sea-air СН4 fluxes in open water areas.

To assess the variation of potential sources and sink capacities in the upper PML by changing SC we estimated the CH4 storage capacity within the upper 18.8 m. For the entire area covered by the 2013 NABOS ll observations, we used the average PML depth of 18.8 m determined using high-resolution vertical profiles of the potential density (Figure 3A). We just considered the surface layer as a layer mainly favored to be influenced by sea-air gas exchange. Then we multiplied that value to the square of the research area and ΔSC in ng/m3.

The locally restricted cooling of the inflowing warm surface water resulted in a potential CH4 uptake of ∼4.99 Mg (106 g) CH4. We considered this cooling effect exclusively for the region west of 90°E (section J), which corresponded to an area ∼30,065 km2.

In addition, cooling in autumn down to the freezing temperature occurs in the whole research area (335,778 km2). An assessment of the potential uptake capacity results in ∼55.70 Mg of CH4 (Figure 3A).

Under the assumption that the whole area becomes ice free in summer, the seasonal warming will result in 12% less SC tending to balance the relicts of the cooling effect (Figure 3A). Then up to ∼46.58 Mg (106 g) CH4 might be potentially released from the ECS to the atmosphere. However, in summer 2013, ∼66% of the research area was still ice covered, resulting in a two thirds smaller amount.

The seasonal changing storage capacity reveals the buffer capacity of the PML for atmospheric or marine-sourced CH4. While mostly annually balanced, the seasonal stored CH4 might be reduced by ongoing oxidation in surface water. Studies considering CH4 oxidation report low oxidation rates in surface waters of other Arctic regions (Mau et al., 2013, Mau et al., 2017; Damm et al., 2015; Uhlig and Loose 2017) but oxidation rate measurements are needed to verify if oxidation acts as CH4 sink in the PML at the ECS.

Seasonal freshening enhanced the SC just by ∼3.2%, resulting in a potential uptake of ∼13.17 Mg CH4. That contribution is small in comparison to the cooling/warming effect on the SC. However, summer sea ice retreat increases the seasonal ice melt at the ECS (Krumpen et al., 2019). That reinforces the freshening effect. In addition, enhanced discharge of Siberian River water (McClelland et al., 2006; Overeem and Syvitski, 2016), which contributes approximately 40% of total freshwater into the Arctic Ocean (Serreze et al., 2006; Haine et al., 2015), will also contribute to increase the CH4 uptake capacity in the coming decades.

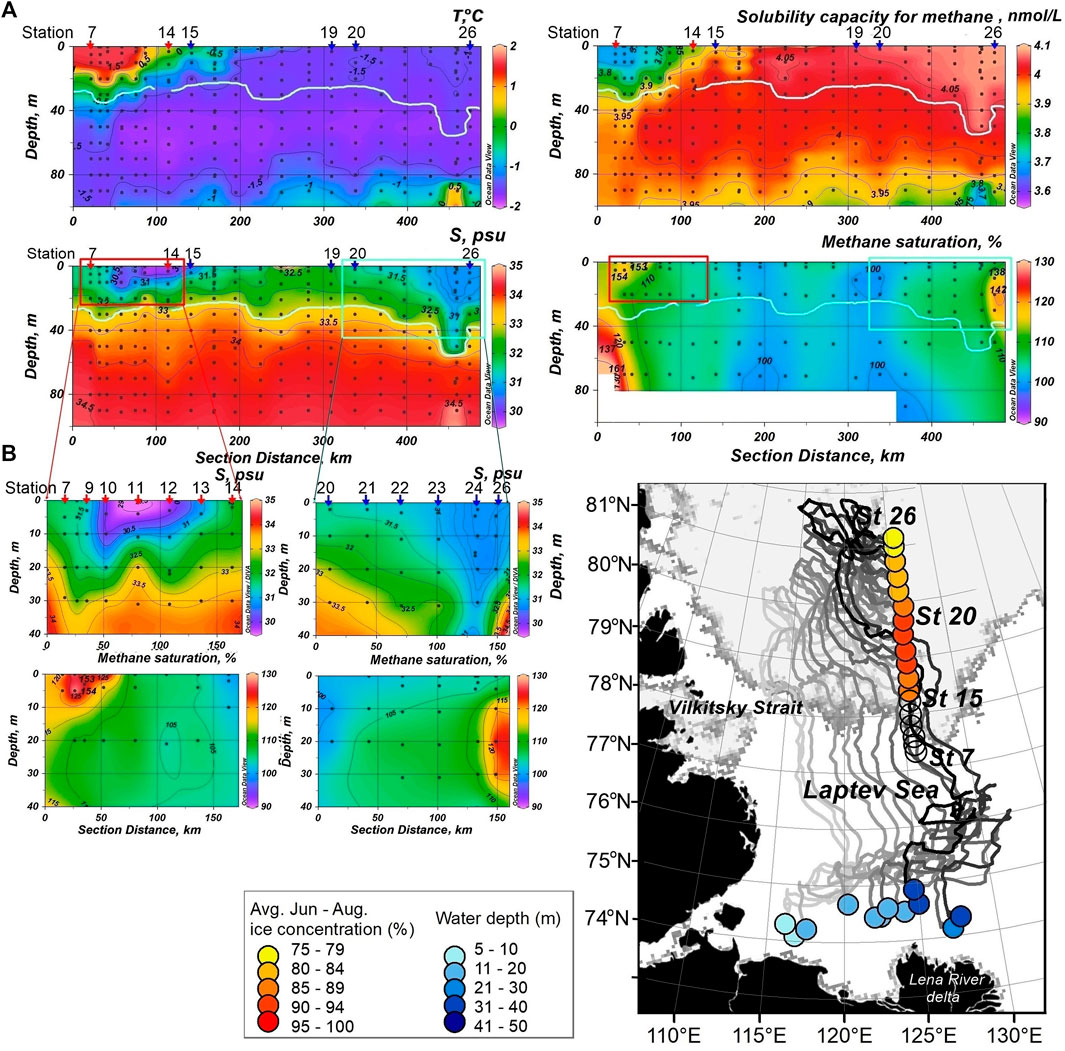

In summer, the surface water in the central Laptev Sea is reported to be slightly CH4 supersaturated with spatial restricted hotspots of enhanced CH4 excess (Thornton et al., 2016). In accordance, we detected CH4 super-saturation up to ∼142% in still ice covered and up to ∼154% in ice-free PML. Further, we also revealed a pronounced spatial heterogeneity in the CH4 excess (Figure 4A). Both aspects clearly point to a locally induced CH4 excess. Hence, we suggest sea ice as the source for CH4 excess, and the ongoing melt of single ice floes as the process, which causes the heterogeneity in the excess (Damm et al., 2015, Damm et al., 2018; Verdugo et al., 2021). Certain features of local CH4 release from sea ice into the PML during melt are shown at the section A and discussed in more detail below.

FIGURE 4. (A) Profiles of temperature, salinity, CH4 solubility capacity (SC) and saturation along section A (126oE, from south to north). During sampling, stations 7–14 and 15–26 were ice-free [red arrows (A), empty circles (B)] and ice covered [blue arrows (A), filled circles (B)], respectively. Red and blue squares contour the CH4 plumes at the southern and northern stations, respectively. Extensions of the red and blue squares are given on the left of the lower panel. The white line gives the boundary between PML and CHL. (B) Backward trajectories of sampled sea ice obtained from IceTrack. The color of the end notes provide the corresponding water depths at the formation site. The color of the start nodes provides the June-August ice concentration, averaged along the individual track lines.

At the southern ice-free stations a CH4 plume was directly located near the surface of the PML. Remarkably, the plume showed gradients in CH4 concentration and also in salinity. Both, CH4 concentration and salinity decreased from south to north (Sts 7–14). That pattern pointed to the formation of the CH4 plume during the early stage of melt, i.e. when brine charged with CH4 had been released from sea ice. By comparison, at the northern stations (Sts 12–14) the plume had been subsequently diluted on top during ongoing melt when brine release ceased and remain freshwater discharged. While at the southern stations the ice had being drifted away just before dilution by freshwater started, leaving the plume on top of the PML undiluted (Figure 4A).

At the northern ice-covered stations (Sts 25, 26), a CH4 plume was disposed at the depth range 10–30 m (Figure 4A). Notably, the plume position pointed to CH4 transport dissolved in brine downward during early stages of sea ice melt (Verdugo et al., 2021). Also the lower sea ice concentration at the northern compared to the southern stations (Figure 4B), pointed to different stages of ice melt.

This counterintuitive pattern is corroborated by the salinity gradients. Further, tracing the drift pattern, it is obvious that ice at the southern and northern part of the section was formed on the inner Laptev Sea shelf impacted by the Anabar and the Lena River waters, respectively (Figure 4B). The ice formed in the Anabar Estuary was less saline because the native winter salinity is < 10 psu (Dmitrenko et al., 2005) than formed in the Lena Estuary, where native winter salinity is 22–28 psu (Dmitrenko et al., 2005). The low salinity of the ice formed in the Anabar estuary caused the relatively slower ice melt at the stations in the middle of the section.

The CH4 plumes were directly related to initial CH4 concentration in the ice. CH4 uptake into sea ice occurs during ice formation from supersaturated seawater (Crabeck et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2014; Damm et al., 2018). The shallow Laptev Sea shelf is a significant sources of CH4 (Shakhova et al., 2015; Baranov et al., 2020) and CH4 super-saturation in shelf water in summer is reported (Bussmann et al., 2017; Sapart et al., 2017; Savvichev et al., 2018).

The river estuaries are characterized by high sedimentation rates (Bauch et al., 2001; Stein et al., 2001; Han, 2014), which exert the dominant control on benthic escape of CH4 at the sediment-water interface in the shallow Laptev Sea (Puglini et al., 2020). Further, CH4 uptake during sea ice formation is favored on shallow shelves as cooling during freeze creates convection down to the bottom. This convective mixing enhances the turbulence, initiates resuspension of sediments, and eventually CH4 release from bottom (Wegner et al., 2017; Damm et al., 2021). Convection also enables rapid transport of CH4 to the sea surface and hence the uptake into sea ice during freeze events (Damm et al., 2007; Damm et al., 2021).

The satellite-based backtracking approach of the ice has shown that ice positioned at the northern plume stations was formed in the Anabar-Lena polynya with a water-depth between 30–50 m before it was advected north by prevailing offshore winds (Krumpen et al., 2016, Krumpen et al., 2019) (Figure 4B).

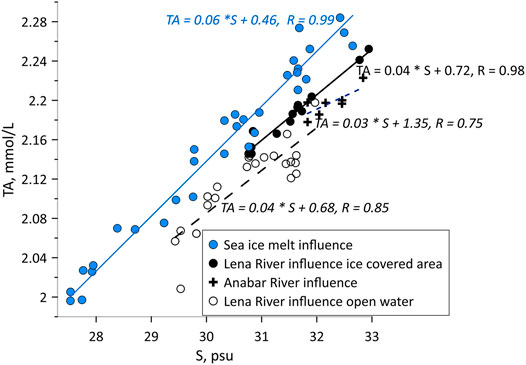

In addition, the TA/S ratio at those plume stations (0.72, Figure 5) was close to the TA of the Lena River water (0.78 mmol/L from Cooper et al., 2008) clearly pointing to freshening by Lena River ice meltwater fraction. The contribution of ice formed in the estuaries of the large Siberian Rivers to the ice cover in Nansen Basin was reported early (Eicken et al., 2005). Hence, we suggest the existence of ice predominantly formed in the external Lena River estuary on the Laptev Sea shelf and therefore argue for CH4 uptake from sediments into Lena estuary ice during its formation in autumn. Also at the southern ice-free stations the PML contained Lena River ice meltwater fraction shown by TA/S signal (0.68, Figure 5).

FIGURE 5. Total alkalinity–salinity plot for PML along the section A and EES sections. Black and empty circles show Lena River ice meltwater fraction at the ice-covered and ice free stations, respectively. Black crosses show Anabar River ice meltwater fraction at the ice-covered stations. Blue circles show the sea ice meltwater fraction. R is the correlation coefficient. Free terms in linear approximation equation TA (S) = kS + TAend correspond to alkalinity of meltwater from estuarine ice or sea ice, respectively, pointing to signatures of freshwater sources.

In comparison to both plume regions, we detected less CH4 supersaturation (up to 109%) at ice-covered stations in the middle of the section (Sts 15–19, Figure 4A). Backward drift trajectories pointed to the southwestern Laptev Sea shelf with depths ranged from 5 to 30 m, influenced by the Anabar River runoff, as the region for ice formation. The TA/S ratio (Figure 5) corroborated the Anabar River waters (Zhulidov and Emetz, 1991) as source water, and the western area of the Laptev Sea as the region for ice formation. The low salinity of the Anabar estuarine-ice caused less CH4 amount, captured during freezing and the relatively slower ice melt at the stations in the middle of the section.

As long as a supersaturation of CH4 in the PML exists, CH4 might also escape to the atmosphere. Sea-air flux is mainly favored at the end of the ice-free season when cooling and storm events diminish the water stratification. Since the atmosphere potentially acts as final sink for the marine CH4 that is seasonally stored in sea ice we have calculated the sea-air CH4 flux.

The PML on the ECS was weakly supersaturated with CH4, and hence a potential slight net source for the atmosphere during the summer (Figure 3B). In total, the CH4 concentration exceeded the atmospheric equilibrium at 0.22 nmol/L. The average sea-air CH4 flux, calculated for open water, was 2.0 nmol/m2day. A slightly higher flux was calculated for the outer shelf of the EES and on the external Laptev Sea shelf at the southern stations along sections A and G (Figure 3B). Summarized, the low sea-air flux indicates the ECS as a potential source for atmospheric CH4 mainly by strong wind loadings, i.e. during storm events.

Rapid ice retreat and accompanying strong sea ice melt provided the largest contribution of fresh water to the upper part of the PML in 2013 (Itkin and Krumpen, 2017). Hence, the level of CH4 excess in the PML was mainly triggered by the dilution with freshwater during later stages of melt. This dilution effect and the potential mixing into deeper water masses are the main processes contributing to keep the estuarine and shelf-sourced CH4 in the ocean. Apart from oxidation, dilution up to marine CH4 background values in sea water finally encourage that the ocean acts as sink for marine CH4 excess in Polar regions (Damm et al., 2021).

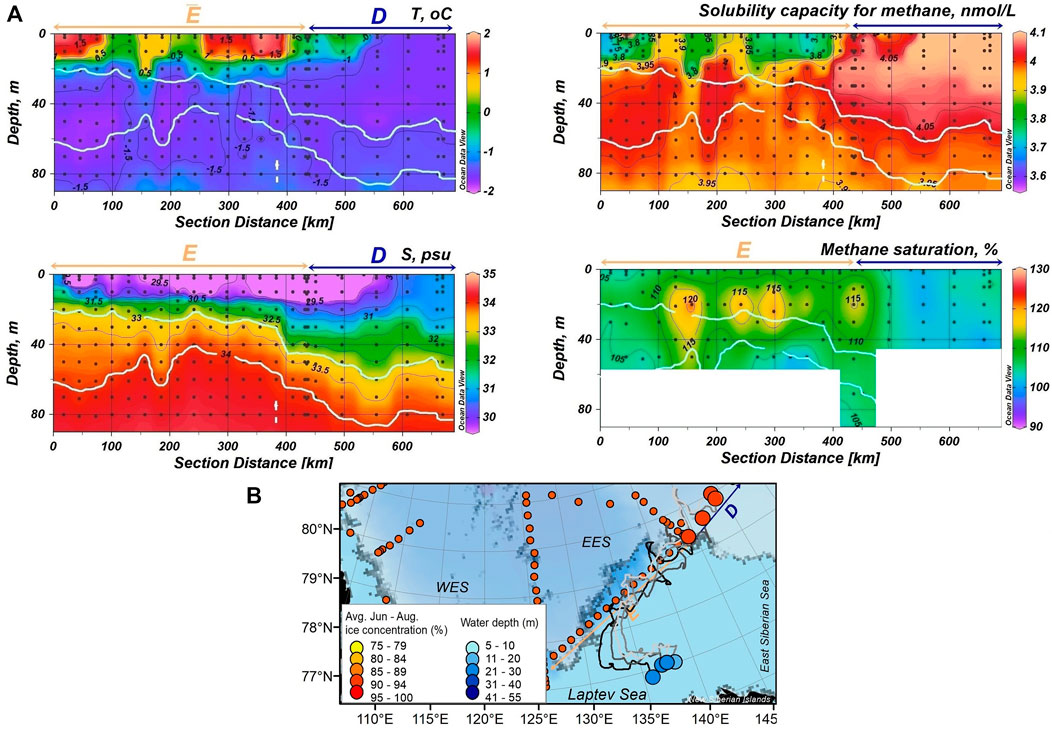

We detected CH4 plumes crossing the boundary between PML and CHL at the ice-free eastern Laptev Sea shelf break (Figure 6A). That feature revealed the intrusion of water from the PML, including the CH4 plume, into the CHL. The increased temperature within those intrusions, related the CHL at surrounding stations, corroborated the PML as the source of the CH4 plumes (Figure 6A). Vertical mixing induced by eddies at the ice edge (Zhao et al., 2014; Pnyushkov et al., 2018) favored the intrusion of water from the PML into the upper CHL and thus the transport of shelf-sourced CH4 into deeper water masses.

FIGURE 6. (A) Profiles of temperature, salinity, CH4 solubility capacity (SC) and saturation along sections E and D (from west to east). Light blue lines show the CHL depths. (B) Backward trajectories of sampled sea ice obtained from IceTrack. The color of the start nodes provides the June-August ice concentration, averaged along the individual track lines. The color of the end notes provide the corresponding water depths at the formation site.

We discussed the plume formation as a result of CH4 release from sea ice coupled to gravity brine drainage during the first melt stage (see above). Ongoing sea ice melt diluted the plume on top by freshwater discharge. Though, under the warm surface layer, the CH4 plumes are sustained by the strong density gradient on the top while the vertical mixing between PML and CHL enabled a downward deepening of the CH4 plumes (Figure 6A). The ice edge provides favorable conditions for eddy generation as specifically, convection by water cooling in leads generates a vertical dipole structure with a cyclonic eddy in the upper layer and an anticyclonic eddy in the CHL (Manley and Hunkins, 1985; Gupta et al., 2020; Meneghello et al., 2021). Further studies are needed to verify the role of eddies especially their enhanced lateral and vertical mixing capacity between certain water masses at the EES (Zhao et al., 2014; Pnyushkov et al., 2018) to contribute to the deepening of CH4 plumes into subsurface waters.

Remarkably, we did not observe CH4 plumes further east at the ice-covered shelf-break (Section D, Figure 6A). At these locations, sea ice melt had just began and CH4 release from sea ice, was still masked by the enhanced SC of the cold PML water. Further, ice drift trajectories indicated the area of sea ice formation in the shallow Laptev Sea shelf north from the New Siberian Islands (Figure 6B). In this area CH4 supersaturation in seawater as a result of CH4 release from the sediments under conditions of active turbulence are expected to be low (Puglini et al., 2020). Hence, the just slightly CH4 super-saturation (up to 108%) corroborate the capturing of low amounts of CH4 in sea ice on the shelf north from the New Siberian Islands.

We found a heterogeneous excess of CH4 next to the surface in the PML and suggest that sea ice impacts on the amount and pathways of CH4 on the ECS. On the one side, the cycle of sea ice formation and melt alters the solubility capacity of CH4 in the surface waters, which ultimately affects its ability to act as a source or sink of atmospheric CH4. On the other side, sea ice transports shelf-derived CH4 to the open ocean, which likely acts as a CH4 sink. It is noteworthy, that the largest CH4 excess in the PML on the ECS is generated by melt of ice originated in outer river estuaries on the shallow Laptev Sea shelf.

The increased solubility capacity during cooling has shown that the PML on the ECS acts as a potential seasonal sink for atmospheric or marine CH4. summer ice melt causes surface freshening and subsequent warming. The warming offsets the cooling effect and triggers the switching of the PML to act as a potential source of atmospheric CH4 in summer. The joint effect of both processes creates the seasonal buffer capacity of the PML. summer sea ice retreat will increase the freshening effect, the buffer capacity and reinforce the sink function of the PML for CH4.

Finally, Arctic amplification favors perennial sea ice retreat, and hence, we expect that larger amounts of freshwater will dilute the CH4 excess in surface water which eventually restricts CH4 flux into the atmosphere.

These linkages should be considered when assessing CH4 sources and sinks in the changing Arctic.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://uaf-iarc.org/nabos/.

EV designed the study. EV and ED wrote the paper. EV sampled and analyzed the CH4 data. AP sampled and analyzed the physical oceanography data and wrote the oceanography chapter. TK carried out sea ice trajectories and wrote the ice trajectory part. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the data, the manuscript and the figures.

This study was performed in the framework of the state assignment of IO RAS (theme 0128-2021-0005); NSF funded IARC Program “Nansen and Amundsen Basins Observational System” (NABOS ll; grant #1203473).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer TW declared a shared affiliation with the author AP to the handling editor at time of review.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We thanked the captain and crew of R/V Akademik Fedorov for their support during the NABOS 2013 cruise. We are grateful to I. Repina for providing wind data. We also thank M. Angelopolous for his comments on an earlier version of this paper. VI acknowledges support by the Interdisciplinary Scientific and Educational School of M.V. Lomonosov Moscow State University Future Planet and Global Environmental Change, AP acknowledges support by the NSF (grant #1724523).

Alkire, M. B., Jacobson, A., Macdonald, R. W., and Lehn, G. (2019). Assessing the Contributions of Atmospheric/Meteoric Water and Sea Ice Meltwater and Their Influences on Geochemical Properties in Estuaries of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Estuaries and Coasts 42, 1226–1248. doi:10.1007/s12237-019-00562-w

Alkire, M. B., Polyakov, I., Rember, R., Pnyushkov, A., Ivanov, V., and Ashik, I. (2017). Combining Physical and Geochemical Methods to Investigate Lower Halocline Water Formation and Modification along the Siberian continental Slope. Ocean Sci. 13, 983–995. doi:10.5194/os-13-983-2017

AMAP (2015). Assessment 2015: Human Health in the Arctic. Oslo, Norway: AMAP. Availableat: https://www.amap.no.

Baranov, B., Galkin, S., Vedenin, A., Dozorova, K., Gebruk, A., and Flint, M. (2020). Methane Seeps on the Outer Shelf of the Laptev Sea: Characteristic Features, Structural Control, and Benthic Fauna. Geo-mar Lett. 40, 541–557. doi:10.1007/s00367-020-00655-7

Bauch, H. A., Mueller-Lupp, T., Taldenkova, E., Spielhagen, R. F., Kassens, H., Grootes, P. M., et al. (2001). Chronology of the Holocene Transgression at the North Siberian Margin. Glob. Planet. Change 31, 125–139. doi:10.1016/s0921-8181(01)00116-3

Belter, H. J., Krumpen, T., von Albedyll, L., Alekseeva, T. A., Birnbaum, G., Frolov, S. V., et al. (2021). Interannual Variability in Transpolar Drift Summer Sea Ice Thickness and Potential Impact of Atlantification. The Cryosphere 15, 2575–2591. doi:10.5194/tc-15-2575-2021

Berchet, A., Bousquet, P., Pison, I., Locatelli, R., Chevallier, F., Paris, J.-D., et al. (2016). Atmospheric Constraints on the Methane Emissions from the East Siberian Shelf. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 4147–4157. doi:10.5194/acp-16-4147-2016

Bussmann, I., Hackbusch, S., Schaal, P., and Wichels, A. (2017). Methane Distribution and Oxidation Around the Lena Delta in Summer 2013. Biogeosciences 14, 4985–5002. doi:10.5194/bg-14-4985-2017

Carmack, E. C., Yamamoto‐Kawai, M., Haine, T. W. N., BaconBluhm, S., Bluhm, B. A., Lique, C., et al. (2016). Freshwater and its Role in the Arctic Marine System: Sources, Disposition, Storage, export, and Physical and Biogeochemical Consequences in the Arctic and Global Oceans. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 121, 675–717. doi:10.1002/2015JG003140

Chuvilin, E., Ekimova, V., Davletshina, D., Sokolova, N., and Bukhanov, B. (2020). Evidence of Gas Emissions from Permafrost in the Russian Arctic. Geosciences 10, 383. doi:10.3390/geosciences10100383

Cooper, L. W., McClelland, J. W., Holmes, R. M., Raymond, P. A., Gibson, J. J., Guay, C. K., et al. (2008). Flow-weighted Values of Runoff Tracers (δ18O, DOC, Ba, Alkalinity) from the Six Largest Arctic Rivers. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35, L18606. doi:10.1029/2008GL035007

Crabeck, O., Delille, B., Thomas, D. N., Geilfus, N. X., Rysgaard, S., and Tison, J. L. (2014). CO2 and CH4 in Sea Ice from a Subarctic Fjord. Biogeosciences Discuss. 11, 4047–4083. doi:10.5194/bgd-11-4047-2014

Damm, E., Bauch, D., Krumpen, T., Rabe, B., Korhonen, M., Vinogradova, E., et al. (2018). The Transpolar Drift Conveys Methane from the Siberian Shelf to the central Arctic Ocean. Sci. Rep. 8, 4515. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-22801-z

Damm, E., Ericson, Y., and Falck, E. (2021). Waterside Convection and Stratification Control Methane Spreading in Supersaturated Arctic Fjords (Spitsbergen). Continental Shelf Res. 224, 104473. doi:10.1016/j.csr.2021.104473

Damm, E., Rudels, B., Schauer, U., Mau, S., and Dieckmann, G. (2015). Methane Excess in Arctic Surface Water- Triggered by Sea Ice Formation and Melting. Sci. Rep. 5, 16179. doi:10.1038/srep16179

Damm, E., Schauer, U., Rudels, B., and Haas, C. (2007). Excess of Bottom-Released Methane in an Arctic Shelf Sea Polynya in winter. Continental Shelf Res. 27, 1692–1701. doi:10.1016/j.csr.2007.02.003

Dmitrenko, I. A., Kirillov, S. A., Tremblay, L. B., Bauch, D., and Willmes, S. (2009). Sea-ice Production over the Laptev Sea Shelf Inferred from Historical Summer-To-winter Hydrographic Observations of 1960s-1990s. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L13605. doi:10.1029/2009GL038775

Dmitrenko, I., Tyshko, K., Kirillov, S., Eicken, H., HolemannKassense, J. H., and Kassens, H. (2005). Impact of Flaw Polynyas on the Hydrography of the Laptev Sea. Glob. Planet. Change 48, 9–27. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2004.12.016

Eicken, H., Dmitrenko, I., Tyshko, K., Darovskikh, A., Dierking, W., Blahak, U., et al. (2005). Zonation of the Laptev Sea Landfast Ice Cover and its Importance in a Frozen Estuary. Glob. Planet. Change 48, 55–83. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2004.12.005

Fransson, A., Chierici, M., and Nojiri, Y. (2009). New Insights into the Spatial Variability of the Surface Water Carbon Dioxide in Varying Sea Ice Conditions in the Arctic Ocean. Continental Shelf Res. 29, 1317–1328. doi:10.1016/j.csr.2009.03.008

Gentz, T., Damm, E., Schneider von DeimlingDeimling, J., Mau, S., McGinnis, D. F., and Schlüter, M. (2014). A Water Column Study of Methane Around Gas Flares Located at the West Spitsbergen continental Margin. Continental Shelf Res. 72, 107–118. doi:10.1016/j.csr.2013.07.013

Günther, F., Overduin, P. P., Yakshina, I. A., Opel, T., Baranskaya, A. V., and Grigoriev, M. N. (2015). Observing Muostakh Disappear: Permafrost Thaw Subsidence and Erosion of a Ground-Ice-Rich Island in Response to Arctic Summer Warming and Sea Ice Reduction. The Cryosphere 9, 151–178. doi:10.5194/tc-9-151-2015

Gupta, M., Marshall, J., Song, H., Campin, J. M., and Meneghello, G. (2020). Sea‐Ice Melt Driven by Ice‐Ocean Stresses on the Mesoscale. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 125, e2020JC016404. doi:10.1029/2020JC016404

Haine, T. W. N., Curry, B., Gerdes, R., Hansen, E., Karcher, M., Lee, C., et al. (2015). Arctic Freshwater export: Status, Mechanisms, and Prospects. Glob. Planet. Change 125, 13–35. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2014.11.013

Haraldsson, C., Anderson, L. G., Hassellöv, M., Hulth, S., and Olsson, K. (19971997). Rapid, High-Precision Potentiometric Titration of Alkalinity in Ocean and Sediment Pore Waters. Deep Sea Res. Part Oceanographic Res. Pap. 44, 2031–2044. doi:10.1016/S0967-0637(97)00088-5

IPCC (2019). Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate. Editors H.-O. Pörtner, D. C. Roberts, V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, and M. Tignor. Chapter lll. Geneva. Availableat: https://www.ipcc.ch/srocc/chapter/chapter-3-2/.

Itkin, P., and Krumpen, T.(2017). Winter sea ice export from the Laptev Sea preconditions the local summer sea ice cover. The Cryosphere Discussions, 1–15. doi:10.5194/tc-2017-28

Iwamoto, K., Ohshima, K. I., and Tamura, T. (2014). Improved Mapping of Sea Ice Production in the Arctic Ocean Using AMSR-E Thin Ice Thickness Algorithm. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 119, 3574–3594. doi:10.1002/2013jc009749

Jones, E. P. (2001). Circulation in the Arctic Ocean. Polar Res. 20 (2), 139–146. doi:10.3402/polar.v20i2.6510

Krumpen, T., Belter, H. J., Boetius, A., Damm, E., Haas, C., Hendricks, S., et al. (2019). Arctic Warming Interrupts the Transpolar Drift and Affects Long-Range Transport of Sea Ice and Ice-Rafted Matter. Sci. Rep. 9, 5459. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-41456-y

Krumpen, T., Birrien, F., Kauker, F., Rackow, T., von Albedyll, L., Angelopoulos, M., et al. (2020). The MOSAiC Ice Floe: Sediment-Laden Survivor from the Siberian Shelf. The Cryosphere 14, 2173–2187. doi:10.5194/tc-14-2173-2020

Krumpen, T., Gerdes, R., Haas, C., Hendricks, S., Herber, A., Selyuzhenok, V., et al. (2016). Recent Summer Sea Ice Thickness Surveys in Fram Strait and Associated Ice Volume Fluxes. The Cryosphere 10, 523–534. doi:10.5194/tc-10-523-2016

Krumpen, T., von Albedyll, L., Goessling, H. F., Hendricks, S., Juhls, B., Spreen, G., et al. (2021). MOSAiC Drift Expedition from October 2019 to July 2020: Sea Ice Conditions from Space and Comparison with Previous Years. The Cryosphere 15, 3897–3920. doi:10.5194/tc-15-3897-2021

Krumpen, T., Willmes, S., Morales Maqueda, M. A., Haas, C., Hölemann, J. A., Gerdes, R., et al. (2011). Evaluation of a Polynya Flux Model by Means of thermal Infrared Satellite Estimates. Ann. Glaciol. 52 (57), 52–60. doi:10.3189/172756411795931615

Macdonald, R. W., McLaughlin, F. A., and Carmack, E. C. (2002). Fresh Water and its Sources during the SHEBA Drift in the Canada Basin of the Arctic Ocean. Deep Sea Res. Part Oceanographic Res. Pap. 49, 1769–1785. doi:10.1016/S0967-0637(02)00097-3

Manley, T. O., and Hunkins, K. (1985). Mesoscale Eddies of the Arctic Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. 90 (C3), 4911–4930. doi:10.1029/jc090ic03p04911

Markus, T., Stroeve, J. C., and Miller, J. (2009). Recent Changes in Arctic Sea Ice Melt Onset, Freezeup, and Melt Season Length. J. Geophys. Res. 114, C12024. doi:10.1029/2009JC005436

Mau, S., Blees, J., Helmke, E., Niemann, H., and Damm, E. (2013). Vertical Distribution of Methane Oxidation and Methanotrophic Response to Elevated Methane Concentrations in Stratified Waters of the Arctic Fjord Storfjorden (Svalbard, Norway). Biogeosciences 10, 6267–6278. doi:10.5194/bgd-10-6461-2013

Mau, S., Römer, M., Torres, M. E., Bussmann, I., Pape, T., Damm, E., et al. (2017). Widespread Methane Seepage along the continental Margin off Svalbard - from Bjørnøya to Kongsfjorden. Sci. Rep. 7, 42997. doi:10.1038/srep42997

McClelland, J. W., Déry, S. J., Peterson, B. J., Holmes, R. M., and Wood, E. F. (2006). A Pan-Arctic Evaluation of Changes in River Discharge during the Latter Half of the 20th century. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L06715. doi:10.1029/2006GL025753

Meneghello, G., Marshall, J., Lique, C., Isachsen, P. E., Doddridge, E., Campin, J.-M., et al. (2021). Genesis and Decay of Mesoscale Baroclinic Eddies in the Seasonally Ice-Covered interior Arctic Ocean. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 51, 115–129. doi:10.1175/JPO-D-20-0054.1

Myhre, C. L., Ferré, B., Platt, S. M., Silyakova, A., Hermansen, O., Allen, G., et al. (2016). Extensive Release of Methane from Arctic Seabed West of Svalbard during Summer 2014 Does Not Influence the Atmosphere. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43 (9), 4624–4631. doi:10.1002/2016GL068999

Overeem, I., and Syvitski, J. P. M. (2016). Shifting Discharge Peaks in Arctic Rivers, 1977-2007. Geografiska Annaler: Ser. A, Phys. Geogr. 92, 285–296. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0459.2010.00395.x

Pnyushkov, A., Polyakov, I. V., Padman, L., and Nguyen, A. T. (201820182). Structure and Dynamics of Mesoscale Eddies over the Laptev Sea continental Slope in the Arctic Ocean. Ocean Sci. 14, 1329–1347. doi:10.5194/os-14-1329-2018

Puglini, M., BrovkinRegnier, V. P., Regnier, P., and Arndt, S. (2020). Assessing the Potential for Non-turbulent Methane Escape from the East Siberian Arctic Shelf. Biogeosciences 17, 3247–3275. doi:10.5194/bg-17-3247-2020

Reagan, M. T., and Moridis, G. J. (2008). Dynamic Response of Oceanic Hydrate Deposits to Ocean Temperature Change. J. Geophys. Res. 113, C12023. doi:10.1029/2008JC004938

Rudels, B., Anderson, L. G., and Jones, E. P. (1996). Formation and Evolution of the Surface Mixed Layer and Halocline of the Arctic Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. 101 (C4), 8807–8821. doi:10.1029/96jc00143

Rudels, B., Jones, E. P., Schauer, U., and Eriksson, P. (2004). Atlantic Sources of the Arctic Ocean Surface and Halocline Waters. Polar Res. 23 (2), 181–208. doi:10.3402/polar.v23i2.6278

Sapart, C. J., Shakhova, N., Semiletov, I., Jansen, J., Szidat, S., Kosmach, D., et al. (2017). The Origin of Methane in the East Siberian Arctic Shelf Unraveled with Triple Isotope Analysis. Biogeosciences 14, 2283–2292. doi:10.5194/bg-14-2283-2017

Savvichev, A. S., Kadnikov, V. V., Kravchishina, M. D., Galkin, S. V., Novigatskii, A. N., Sigalevich, P. A., et al. (2018). Methane as an Organic Matter Source and the Trophic Basis of a Laptev Sea Cold Seep Microbial Community. Geomicrobiology J. 35, 411–423. doi:10.1080/01490451.2017.1382612

Screen, J. A., and Simmonds, I. (2010). The central Role of Diminishing Sea Ice in Recent Arctic Temperature Amplification. Nature 464 (7293), 1334–1337. doi:10.1038/nature09051

Serreze, M. C., Barrett, A. P., Slater, A. G., Woodgate, R. A., Aagaard, K., Lammers, R. B., et al. (2006). The Large-Scale Freshwater Cycle of the Arctic. J. Geophys. Res. 111, C11010. doi:10.1029/2005JC003424

Shakhova, N., Semiletov, I., and Chuvilin, E. (2019). Understanding the Permafrost-Hydrate System and Associated Methane Releases in the East Siberian Arctic Shelf. Geosciences 9, 251. doi:10.3390/geosciences9060251

Shakhova, N., Semiletov, I., Leifer, I., Sergienko, V., Salyuk, A., Kosmach, D., et al. (2014). Ebullition and Storm-Induced Methane Release from the East Siberian Arctic Shelf. Nat. Geosci 7, 64–70. doi:10.1038/ngeo2007

Shakhova, N., Semiletov, I., Salyuk, A., Yusupov, V., Kosmach, D., and Gustafsson, Ö. (2010). Extensive Methane Venting to the Atmosphere from Sediments of the East Siberian Arctic Shelf. Science 327, 1246–1250. doi:10.1126/science.1182221

Shakhova, N., Semiletov, I., Sergienko, V., Lobkovsky, L., Yusupov, V., Salyuk, A., et al. (2015). The East Siberian Arctic Shelf: towards Further Assessment of Permafrost-Related Methane Fluxes and Role of Sea Ice. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A. 373 (2052), 20140451. doi:10.1098/rsta.2014.0451

Silyakova, A., Jansson, P., Serov, P., Ferré, B., Pavlov, A. K., Hattermann, T., et al. (2020). Physical Controls of Dynamics of Methane Venting from a Shallow Seep Area West of Svalbard. Continental Shelf Res. 194, 104030. doi:10.1016/j.csr.2019.104030

Spreen, G., Kaleschke, L., and Heygster, G. (2008). Sea Ice Remote Sensing Using AMSR-E 89-GHz Channels. J. Geophys. Res. 113, C02S03. doi:10.1029/2005JC003384

Stein, R., Boucsein, B., Fahl, K., Garcia de Oteyza, T., Knies, J., and Niessen, F. (2001). Accumulation of Particulate Organic Carbon at the Eurasian continental Margin during Late Quaternary Times: Controlling Mechanisms and Paleoenvironmental Significance. Glob. Planet. Change 31, 87–104. doi:10.1016/s0921-8181(01)00114-x

Thornton, B. F., Geibel, M. C., Crill, P. M., Humborg, C., and Mörth, C.-M. (2016). Methane Fluxes from the Sea to the Atmosphere across the Siberian Shelf Seas. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 5869–5877. doi:10.1002/2016GL068977

Uhlig, C., and Loose, B. (2017). Using Stable Isotopes and Gas Concentrations for Independent Constraints on Microbial Methane Oxidation at Arctic Ocean Temperatures. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 15, 737–751. doi:10.1002/lom3.10199

Verdugo, J., Damm, E., and Nikolopoulos, A. (2021). Methane Cycling within Sea Ice; Results from Drifting Ice during Late spring, north of Svalbard. The Criosphere 15, 2701–2717. doi:10.5194/tc-15-2701-2021

Wanninkhof, R. (1992). Relationship between Wind Speed and Gas Exchange over the Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. 97, 7373–7382. doi:10.1029/92JC00188

Wegner, C., Wittbrodt, K., Holemann, J., Janout, M., Krumpen, T., Selyuzhenok, V., et al. (2017). Sediment Entrainment into Sea Ice and Transport in the Transpolar Drift: A Case Study from the Laptev Sea in winter 2011/2012. Continental Shelf Res. 141, 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.csr.2017.04.010

Westbrook, G. K., Thatcher, K. E., Rohling, E. J., Piotrowski, A. M., Pälike, H., and Osborne, A. H. (2009). Escape of Methane Gas from the Seabed along the West Spitsbergen continental Margin. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L15608. doi:10.1029/2009GL039191

Wiesenburg, D. A., and Guinasso, N. L. (1979). Equilibrium Solubilities of Methane, Carbon Monoxide, and Hydrogen in Water and Seawater. J. Chem. Eng. Data 24, 356–360. doi:10.1021/je60083a006

Yamamoto-Kawai, M., Tanaka, N., and Pivovarov, S. (2005). Freshwater and Brine Behaviors in the Arctic Ocean Deduced from Historical Data of δ18O and Alkalinity (1929-2002 A.D.). J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 110, C10003. doi:10.1029/2004JC002793

Zhao, M., Timmermans, M.-L., Cole, S., Kishfields, R., Proshutinski, A., and Tolle, J. (2014). Characterizing the Eddies Field in the Arctic Ocean Halocline. J. Geophys. Res.-Ocean. 119, 8800–8817. doi:10.1002/2014JC010488

Zhou, J., Tison, J.-L., Carnat, G. N., Geilfus, X., and Delille, B. (2014). Physical Controls on the Storage of Methane in Landfast Sea Ice. The Cryosphere 8, 1019–1029. doi:10.5194/tc-8-1019-2014

Keywords: methane plumes, polar mixed layer, Eurasian continental slope, sea ice, shelf-basin interaction

Citation: Vinogradova E, Damm E, Pnyushkov AV, Krumpen T and Ivanov VV (2022) Shelf-Sourced Methane in Surface Seawater at the Eurasian Continental Slope (Arctic Ocean). Front. Environ. Sci. 10:811375. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.811375

Received: 08 November 2021; Accepted: 12 January 2022;

Published: 28 January 2022.

Edited by:

Daniel F. McGinnis, Université de Genève, SwitzerlandReviewed by:

Terry Whitledge, Retired, Fairbanks, AK, United StatesCopyright © 2022 Vinogradova, Damm, Pnyushkov, Krumpen and Ivanov. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Elena Vinogradova, dmlub2dyYWRvdmFAb2NlYW4ucnU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.