- 1Department of Human and Organizational Development, Peabody College, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, United States

- 2Sandia National Laboratories, Albuquerque, NM, United States

Drinking water has and will continue to be at the foundation of our nation’s well-being and there is a growing interest in United States (US) drinking water quality. Nearly 30% of the United States population obtained their water from community water systems that did not meet federal regulations in 2019. Given the heavy interactions between society and drinking water quality, this study integrates social constructionism, environmental injustice, and sociohydrological systems to evaluate local awareness of drinking water quality issues. By employing text analytics, we explore potential drivers of regional water quality narratives within 25 local news sources across the United States. Specifically, we assess the relationship between printed local newspapers and water quality violations in communities as well as the influence of social, political, and economic factors on the coverage of drinking water quality issues. Results suggest that the volume and/or frequency of local drinking water violations is not directly reflected in local news coverage. Additionally, news coverage varied across sociodemographic features, with a negative relationship between Hispanic populations and news coverage of Lead and Copper Rule, and a positive relationship among non-Hispanic white populations. These findings extend current understanding of variations in local narratives to consider nuances of water quality issues and indicate opportunities for increasing equity in environmental risk communication.

1 Introduction

The United States Safe Drinking Water Act has contributed to one of the safest drinking water supplies in the world. Despite the general reliability and accessibility of drinking water infrastructure for communities across the United States, inequitable provision of adequate drinking water persists Allaire et al. (2018), McDonald and Jones (2018). Community Water Systems (CWS) serve 94% of the United States population, yet 28% of water systems experienced at least one water quality violation in 2019, based on the United States’ Environmental Protection Agency’s (USEPA) Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) United States Environmental Protection Agency (2021).

The disproportionate distribution of safe drinking water and perceptions of those affected can be partially understood through the lens of social constructionism. In this research, social constructionism is defined as the analysis of social processes which contribute to the development of epistemologies and knowledges Burningham and Cooper (1999). Often applied to understand the creation and legitimization of social phenomena, social constructionism can play an important role in human behavior related to environmental degradation and the maintenance of inequity and power differentials. For example, theorists have applied social constructionism to understand climate science denial, and environmental sustainability Prasad (2019); Longo et al. (2021). When considering injustices in drinking water quality, individuals with more power may construct and legitimize explanations for existing environmental inequities for those with lesser power. This results in an ongoing and constitutive narrative that not only normalizes but also maintains the inequitable distribution of environmental risks Grove et al. (2018). Thus, the social constructionism of poor drinking water quality can pose significant and compounding risks to communities with greater proportions of low-income individuals and people of color. The USEPA defines environmental justice as “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies” United States Environmental Protection Agency (2022). Environmental justice requires that all communities have “the same degree of protection from environmental and health hazards” and “equal access to the decisionmaking process to have a healthy environment in which to live, learn, and work United States Environmental Protection Agency (2022). The latter half of this definition is important because it highlights the agency necessary for all individuals to define their interpretation of healthy and thriving communities.

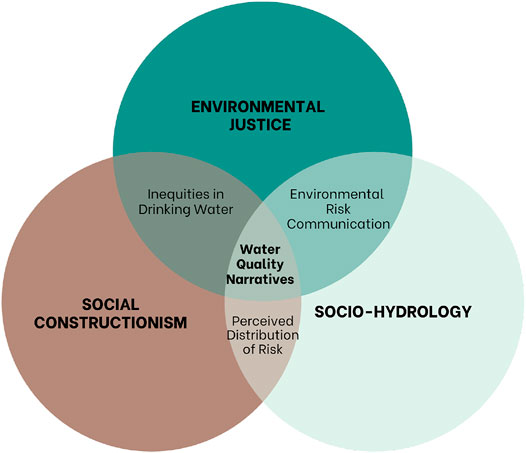

An important part of how people define healthy and just communities is how they discuss environmental issues with one another. Media coverage of water quality narratives is a one example of social constructionism because it captures community perceptions of environmental risk in literary form. However, patterns in social constructionism do not singularly define the ongoing disproportional distribution of water quality risks in communities. Rather, water quality narratives pose the opportunity to extend theories of social constructionism into the field of socio-hydrology to understand environmental justice (Figure 1). The field of socio-hydrology highlights the complicated interactions and interdependencies between humans, water systems, and our physical surroundings (Sivapalan et al., 2012; Madani and Shafiee-Jood, 2020). By studying the inequities of coupled human-water systems, researchers gain a broader understanding of social, behavioral, and developmental impacts of water management. Thus, integrating social constructionism, environmental injustice, and sociohydrological systems would enable critical nuances into understanding and mitigating environmental risk in communities.

FIGURE 1. Water quality narrative analysis lies at the intersection of environmental justice, social constructionism, and socio-hydrology.

The Flint Drinking Water Crisis is an example of the media’s role in water quality issues. The local media helped to shed light on ongoing environmental injustices, eventually leading to federal policy changes (DelToral, 2015; Egan and Spangler, 2016; Jackson, 2017). Flint’s struggle for safe drinking water revealed the inextricable relationship between environmental justice and social constructionism. Moreover, the complex relationships between social relationships and social-hydrological systems. For example, local newspaper outlets such as The Flint Journal provided consistent coverage of public discussion and community struggles, which amplified the voices of community organizers and families affected by lead poisoning resulting in a national dialogue about drinking water quality in the United States. Thus, the narratives that local news reporters collect and distribute play a significant role in how individuals perceive risk and can help to garner a response to local water quality issues.

Given the role of social constructionism and coupled socio-hydrological systems in environmental injustice, local newspapers serve as an invaluable source of data for studying the social aspects of drinking water. Previous studies have used local news and social media platforms to understand water-related matters. Analyses of local water narratives have uncovered patterns of substandard water in Mobile Home Parks (Pierce and Gonzalez, 2017), unequal stewardship expectations for Indigenous peoples (Lam et al., 2017), and shared frustration and health concerns among families affected by lead pollution (Ekenga et al., 2018). Although previous research has utilized local news and social media platforms to assess important water-related matters, all were dependent on an analytical process called content analysis, which requires manual coding of each article to understand overarching trends. While such research methods are valuable, the time and resources necessary to read and code each newspaper generally results in fewer articles being analyzed, which can limit the geographic and temporal range of the evaluations. Moreover, while targeted research on the topic of drinking water narratives exists, a more systematic, national approach is lacking.

More recently, researchers have applied text analytics to newspaper articles (Gunda, 2018). Text analytics is a data-driven approach that uses natural language processing to analyze millions of articles for trends and patterns that would not have been previously feasible (Moreno and Redondo, 2016). Applying computational methods to text data results in a much broader understanding of local newspaper narratives and allows researchers to evaluate temporal and spatial trends arising from local variation. In doing so, data-based approaches informed by theory can provide a more robust understanding of risks to drinking water quality across regions.

The aims of this study were to leverage text analytics to 1) evaluate temporal and regional trends of water pollution-related articles in local news and 2) examine the relationship between local water violations and potential political, economic, and sociodemographic variables on water-related news coverage. Pollution is evaluated through water quality violations, which are assessed using SDWA rule violations. This study provides a data-driven approach to understanding media patterns and their relationship with social and physical differences across the United States, allowing for a broader understanding of patterns and trends than previous case studies. Lastly, our findings underline the importance of local journalism in water quality issues, highlighting the salience of community news coverage amidst environmental risks.

2 Methodology

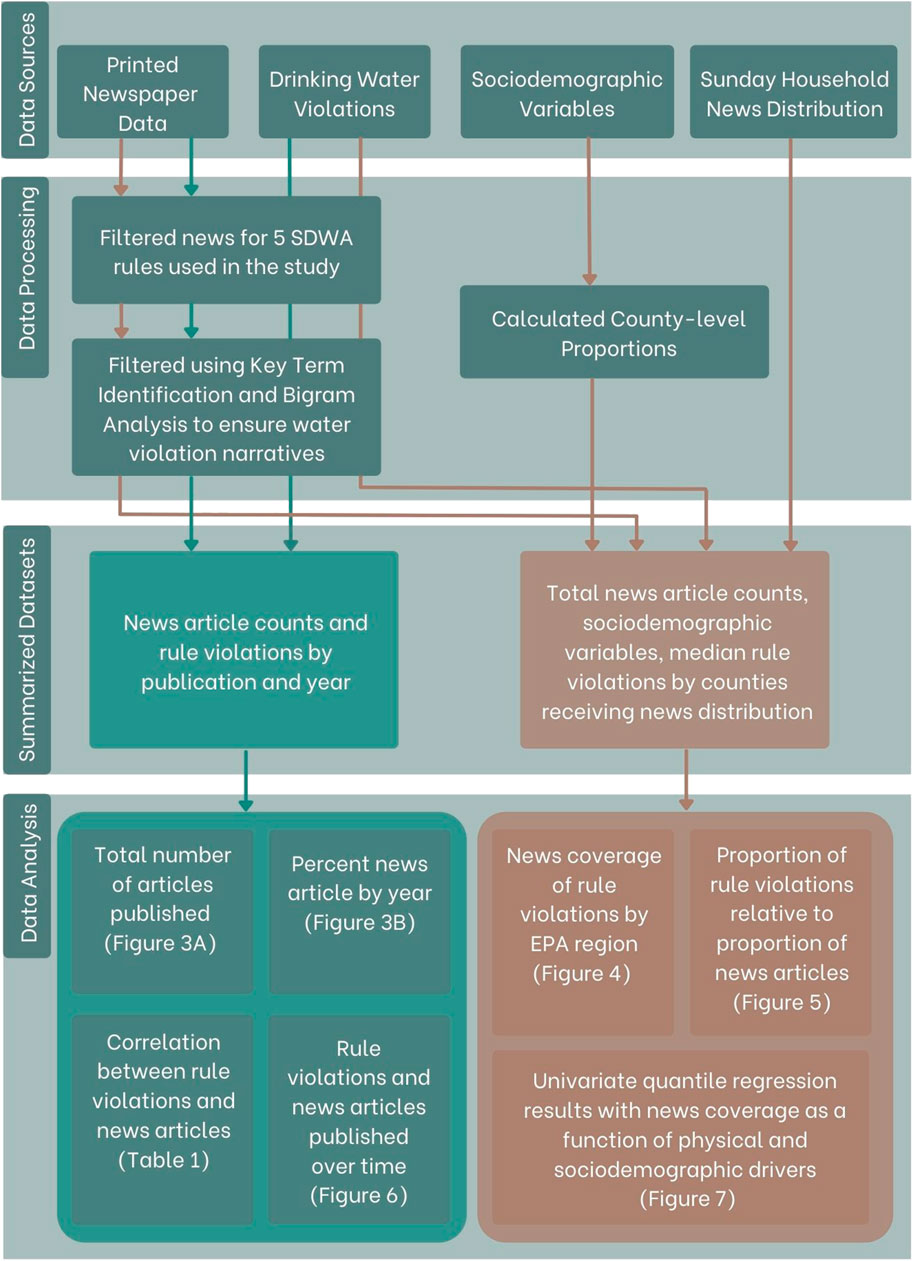

This study utilized a dataset of water-related newspaper articles downloaded from LexisNexis for the years 2009–2017. Sociodemographics and water quality violations were obtained from publicly available data sources. Data sources, processing, and analyses strategies are discussed in the following subsections (Figure 2). All data processing and analyses were conducted in RStudio [v.1.3.1056].

2.1 Data Sources

A dataset of water-related newspaper articles—created by downloading any local news source article from LexisNexis that mentioned the word “water” within the United States- was used for this study (Gunda, 2018). In total, there were 413,690 news articles (published between 2009 and 2017) across 25 news sources that were evaluated for this study. Metadata for each article such as city of publication and date published is also provided in the corpus (Supplementary Table S1). Sunday household distribution (at the county-level) was downloaded for each of the newspaper sources using the Alliance for Audited Media’s (AAM) Media Intelligence Center (Alliance for Audited Media, 2021). Sunday distribution was chosen because it was available for all news sources, whereas availability of distribution data for the remaining days of the week was highly variable.

A list of primary regulated drinking water contaminants were compiled from the National Primary Drinking Water Regulations (NPDWR) per the SDWA (US EPA, 2021). In total, there were over 90 contaminants that address several aspects of drinking water quality, such as surface water treatment, disinfectants and disinfection byproducts, inorganic and organic chemicals, and radionuclides.

In addition to water quality terms, we also compiled data regarding drinking water violations, sociodemographics, and political tendencies. Drinking water rule violations for the counties receiving news coverage were downloaded from the USEPA’s Safe Drinking Water Information System (SDWIS) covering a range of January 2009 to December 2017 (United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2021). County-level sociodemographic data were obtained from American Community Surveys (ACS) 5-year estimates (2009–2018) (US Census Bureau, 2021); these were queried using the TidyCensus package [v. 0.9.9.5] (Walker, 2020). Political tendencies were captured using county-level presidential election data describing the number of Republican votes in the past 2008–2016 presidential election, relative to the article’s publication date (MIT Election Data and Science Lab, 2018).

2.2 Data Processing

Evaluation of these articles for water quality-related issues was facilitated using key term identification (Silge and Robinson, 2017). Five SDWA rules were chosen for this analysis (Supplementary Table S1, S2). The five rules analyzed were: 1) Lead and Copper Rule (LCR); 2) Disinfection Byproducts (DBP) Rule; 3) Radionuclides (RN) rule; 4) Volatile Organic Chemicals (VOC) Rule; and 5) Total Coliform Rule (TCR). The corpus was filtered for any articles containing one or more contaminants monitored under each of these five SDWA rules.

To evaluate the corpus for the five SDWA rules, key term identification, an analytical approach that identified whether a list of words are within text data was used (Krauthammer and Nenadic, 2004). After filtering for the primary regulated contaminants, there were 42,764 articles in the corpus that mentioned a primary contaminant monitored per the SDWA rule. However, some of these articles included colloquial variations of “lead” (i.e., “lead author” and “lead attorney”). To address these issues, bigram analysis was conducted to further filter the remaining articles. Bigram analysis generates 2-word phrases/combinations which researchers can use to understand the relationships between word pairs (Silge and Robinson, 2017). After generating the bigrams, articles that only pertained to contaminant issues (e.g., “lead pipes” or “lead testing”) were retained, while nonpertinent terms (e.g., “lead author” or “lead attorney”) were not. The final filtered corpus contained 11,562 articles. With the final filtered corpus, summaries of coverage (i.e., tallies) each of the five SDWA rules, total as well as across different newspapers and over time were created.

For the community variables, normalization was conducted to calculate proportions. For example, the sociodemographic variables were divided by the county’s total population to reflect the proportion of 1) non-Hispanic white; 2) Black; 3) American Indian and Alaska Native (referenced as “American Indian” hereafter); 4) Hispanic individuals; and 5) foreign-born individuals who speak Spanish at home. Additionally, the ACS workforce population value was used to calculate proportion of individuals employed in agriculture, mining, fishing, or logging. Publication dates were matched with the most recent presidential election cycles during the study period (i.e., 2008, 2012, and 2016) to capture the proportion of Republican votes compared to total votes within each county. For example, an article published in 2010 was assigned to the 2008 presidential election.

These datasets were merged to create two datasets for analysis, one capturing temporal patterns in violations and the other capturing sociodemographics (Figure 2). The first dataset contained counts of both newspaper articles and violations for each SDWA rule (stratified by publication and year) while the second dataset contained newspaper article counts, sociodemographics, political leanings, and rule violations for each SDWA rule. For the latter, total newspaper counts by SDWA rule were joined with median annual SDWA rule violations and sociodemographics (for counties receiving Sunday newspaper distribution), and analyzed at the county-level for each newspaper’s distribution.

2.3 Data Analyses

Several methods were employed to explore patterns in news coverage over different geographies (e.g., EPA regions and county news distributions) and time. First, SDWA rules were visualized for the entire dataset, followed by annual publications stratified by SDWA rule. To evaluate patterns in publication, correlations between different SDWA rules were calculated. SDWA rule coverage was also visualized at the USEPA regional level, to explore regional trends of water quality-related news. The relationship between SDWA rule violations and SDWA news coverage was examined using proportionality, over both the entire study period and annually. The influence of physical and sociodemographic patterns on SDWA news coverage was explored using univariate quantile regressions. Predictors included SDWA violations occurring within the counties receiving news distribution; proportion of non-Hispanic white, Black, Hispanic, and American Indian populations; proportion of foreign born Spanish-speaking individuals; proportion of the working population employed in agricultural, mining, fishing, and logging; and the proportion of Republican voters.

3 Results

There were over 11,500 articles mentioning an SDWA rule published from 2009 to 2017 (Supplementary Table S1). The five rules chosen for this analysis (Lead and Copper Rule (LCR), Disinfection Byproducts (DBP rule), Radionuclides (RN) rule, Volatile Organic Chemicals (VOC) rule, and Total Coliform Rule (TCR)) were covered in over 7,000 articles across a total of 25 news sources from 24 different states (Supplementary Table S1). Below, we describe in greater detail the temporal and regional differences observed for the five selected rules.

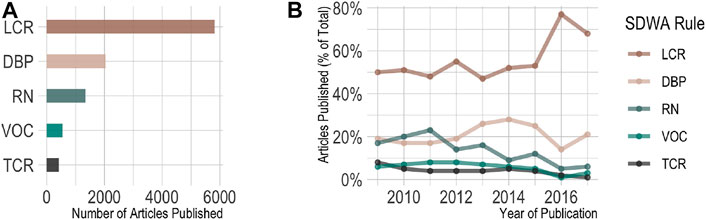

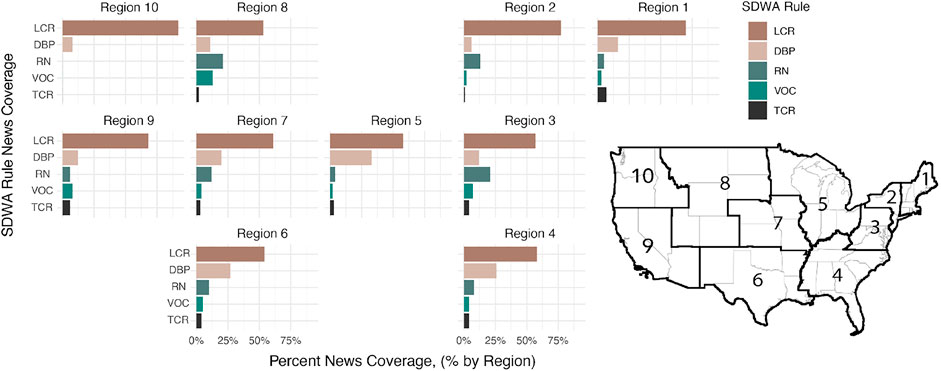

Coverage of water-related news articles varied significantly by rule and region. Coverage of LCR was most prevalent, followed by DBP, RN, VOC, and TCR (Figure 3). Annual rates of publication also varied by rule, with some showing a general downward trend (VOC, TCR, and RN). DBP and LCR fluctuated more over time (standard deviation (SD) = 43.9 and 251, respectively; Supplementary Table S3), and a noticeable spike in LCR-related articles occurred in 2016 (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3. (A) Total number of articles published. (B) Annual percentage of news articles across 5 SDWA rules, 2009-2017. Generally, LCR was most discussed within the news articles, with a prominent increase occurring in 2016. Note: LCR = Lead and Copper Rule, DBP = Disinfection Byproducts Rule, RN = Radionuclides Rule, VOC = Volatile Organic Chemicals Rule, TCR = Total Coliform Rule.

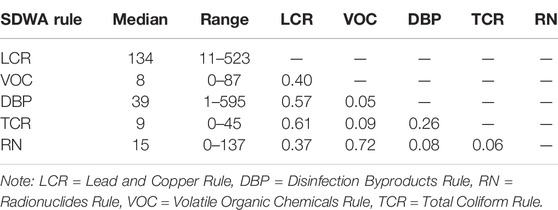

News coverage for each of the five rules showed a relationship with coverage of the other four rules. For example, articles published on LCR correlated with articles related to TCR and DBP. Similarly, the publication of VOC-related articles were correlated with news articles mentioning RN (Table 1).

TABLE 1. Median, range, and correlation between coverage of SDWA rules. Articles including LCR were likely to be published with TCR and DBP, while VOC articles tended to be published more frequently with RN.

The number of water quality-related newspaper articles published was highly variable by region (Figure 4). For example, coverage of LCR was the greatest in USEPA regions 2 and 10 while coverage of DBP was greatest in region 5. RN, on the other hand, was more widely discussed in regions 3 and 8. The share of articles published that mention VOC were greatest in region 8, while TCR was most frequent in USEPA regions 1 and 9 (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4. Regional News Coverage by Rule, 2009–2017. News coverage of LCR was high in all regions, while coverage of DBP, RN, VOC, and TCR varied by USEPA region. Note: LCR = Lead and Copper Rule, DBP = Disinfection Byproducts Rule, RN = Radionuclides Rule, VOC = Volatile Organic Chemicals Rule, TCR = Total Coliform Rule.

When considering by news source, different nuances emerge. For example, LCR was generally the most covered across the newspapers, with the exception of RN in the Richmond Times Dispatch (USEPA Region 3), and DBP in Dayton Daily News (USEPA Region 5) and Lincoln Journal Star (USEPA Region 7) (Supplementary Figure S1). VOC was covered most frequently in the Denver Post (USEPA Region 8). Across all five rules, Dayton Daily News (USEPA Region 5) published the most water quality-related articles in the given time period, with a total of 1,073 articles published, and an average of 119 articles per year. In contrast, The Columbian (USEPA Region 1) published the least articles over the time period, with only 12 articles in the observed time period (averaging 1.3 articles per year).

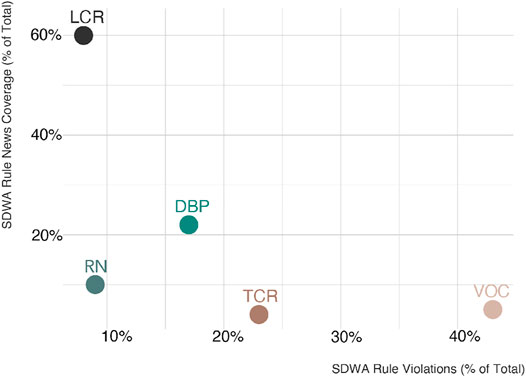

In addition to evaluating patterns in news coverage, we also evaluated the relationship between local water violations and water-related news article publication. Although LCR-related articles dominated the majority of water-related news coverage, this rule had the lowest percentage of violations of all rules assessed (Figure 5). Contrastingly, VOC and TCR, which had the majority of violations, were discussed far less (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5. Proportion of violations occurring relative to proportion of news coverage among the 5 SDWA rules. LCR received a significant proportion of news coverage among the five SDWA rules, despite receiving the least proportion of violations. Note: LCR = Lead and Copper Rule, DBP = Disinfection Byproducts Rule, RN = Radionuclides Rule, VOC = Volatile Organic Chemicals Rule, TCR = Total Coliform Rule.

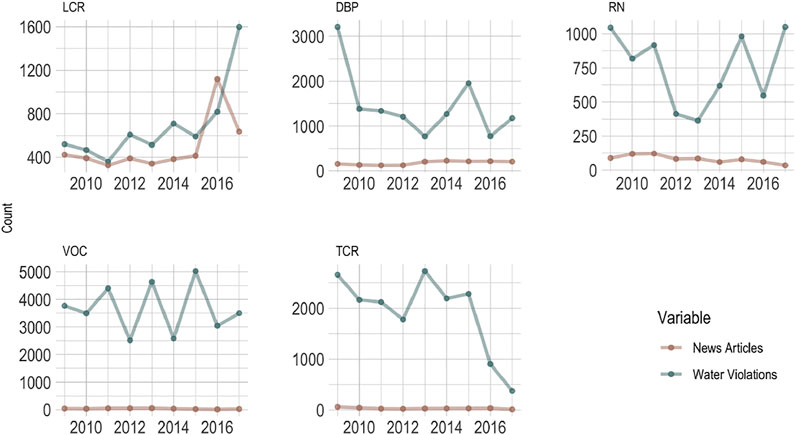

The directional relationship between news coverage and violations was further evaluated at an annual scale. Despite the large number of violations attributed to VOC, TCR, and DBP from 2009 to 2017, few articles were published during these time periods. LCR, on the other hand, were discussed widely, spiking in 2016 with more than 1,500 articles published (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6. Number of violations and articles published by rule, 2009–2017 (Note varying y-axes). Except for LCR, the correlation between violations and news coverage was generally poor. Note: LCR = Lead and Copper Rule, DBP = Disinfection Byproducts Rule, RN = Radionuclides Rule, VOC = Volatile Organic Chemicals Rule, TCR = Total Coliform Rule.

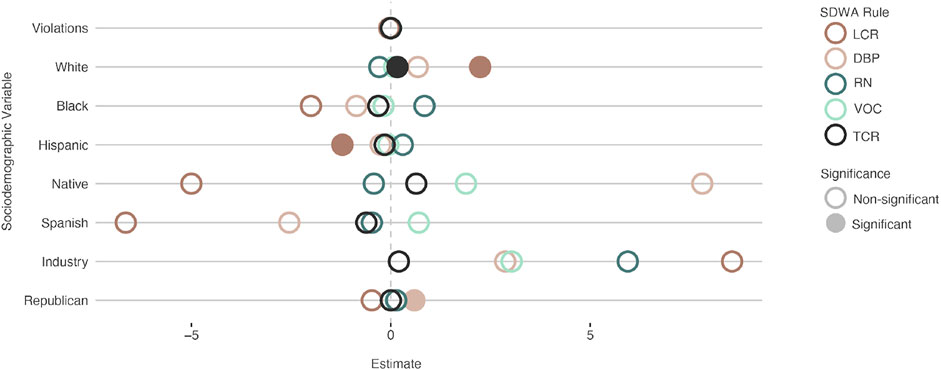

Univariate regression analyses evaluated the relationships between physical (i.e., violations) and sociodemographic drivers. All five SDWA rule violations did not have a relationship with water-related news (Figure 7; Supplementary Table S4). However, the relationship between coverage and racial/ethnic sociodemographics showed different patterns. The proportion of non-Hispanic white individuals had a positive relationship on coverage of LCR- and TCR-related coverage, with negative directionality for RN and positive for DBP and VOC (Supplementary Table S4). This means that communities with greater non-Hispanic white populations receive more news coverage on the topics of LCR and TCR, and tend to have less coverage on the topics of RN, and more coverage on the topics of DBP and VOC. In contrast, the proportion of Hispanic and Black individuals generally had a negative direction with rule coverage, with the exception of RN, which had a positive direction (Supplementary Table S4). This means that communities with greater Hispanic and Black populations tend to receive less coverage about LCR, TCR, DBP, and VOCs, and more on the subject of RN. Lastly, the proportion of American Indian highly varied in direction and beta across all five rules (Supplementary Table S4). This suggests the proportion of American Individuals in a community and the topics of coverage it will receive can vary widely by contaminant.

FIGURE 7. Univariate quantile regression results showing news coverage as a function of physical and sociodemographic drivers for each rule. The beta values (i.e., coefficients) reflect the direction of influence of the different co-variates. A negative direction between violations and news coverage was observed, while relationships between news coverage and sociodemographic, cultural, economic, and political relationships varied. Note: LCR = Lead and Copper Rule, DBP = Disinfection Byproducts Rule, RN = Radionuclides Rule, VOC = Volatile Organic Chemicals Rule, TCR = Total Coliform Rule.

Cultural, economic, and political variables also had varying associations with news coverage of water quality issues. For example, the proportion of foreign born Spanish-speaking individuals had a negative direction with all coverage types but VOC (Figure 7; Supplementary Table S4). This suggests that communities with a larger proportion of Spanish-speaking households tend to receive less news coverage on all contaminants, except for VOC. Contrastingly, the proportion of individuals employed in industrial activities had a positive direction on all coverage types. This means that the greater the proportion of working individuals employed in industry, the more they tend to receive water related news coverage. Lastly, the proportion of Republican voters had a positive relationship with DBP-related coverage and varied for the other four rules (Figure 7; Supplementary Table S4). This suggests that a greater proportion of Republican-voting individuals will receive more water quality news coverage on the topic of DBPs.

4 Discussion

The aims of this study were to elucidate patterns in news coverage of drinking water quality issues, with a focus on potential relationships between associated physical (i.e., violations) and sociodemographic variables. Our analyses also examined water quality spatially and temporally, with attention to national trends over 2009 to 2017. Our results suggest several notable findings, such as the inequitable news coverage of drinking water quality issues among Black and Hispanic communities. Additionally, our work revealed positive directions with political and economic variables that are contrary to other findings. Discussion of these findings, and the implications of our results are below.

The temporal and regional trends of water-quality related articles revealed several noteworthy insights. Overall, the publication of water-related news articles were most prominent for LCR, followed by DBP, RN, VOC, and TCR, (Figure 3). Over time, there was a noticeable increase in LCR coverage in 2016, reflecting national coverage of the Flint Water Crisis (Jackson, 2017). The dominance of LCR-related coverage could be stemming from the immediate, long-term health consequences of this rule, which negatively impacts infants and children, a vulnerable population that garners significant empathy among the public (Ekenga et al., 2018; Levallois et al., 2018). We also found that LCR and DBP were more likely to be published in tandem, which could be due to their connections to public water system maintenance, whereas RN, VOC, and TCR are the result of industrial or agricultural activity (US EPA, 2009). This divide may exist because the consequences of treatment and maintenance (i.e., LCR and DBP) are viewed as necessary investments for safe drinking water (Tanellari et al., 2015), whereas contaminants related to economic growth (i.e., RN, VOC, and TCR) may be less frequently discussed within the news, especially when communities are reliant on those sources of income (Griffin and Dunwoody, 1995).

Regional patterns in coverage could be attributed to local variations in contaminant sources. We found that USEPA regions 2 and 10 had the greatest percentage of water-related LCR coverage, while DBP-related coverage was greatest in region 5 (Figure 4). The high coverage of LCR in region 2 may be related to New York and New Jersey’s aging infrastructure, which has resulted in elevated lead levels in the past (Lytle et al., 2020; American Society of Civil Engineers, 2021). USEPA region 5, on the other hand, is often characterized by its tendency to over-apply fertilizers and its limited wastewater infrastructure, which could describe the high coverage of DBP in this region (Tuser, 2021). High coverage of RN and VOC in USEPA regions 8 and 3 could be due to the mining and oil and gas production in these areas (United States Energy Information Administration, 2021). Lastly, coliform is often a consequence of agricultural production, which explains its prevalent coverage within USEPA regions 1 and 9, the latter of which has a significant amount of agricultural land (Cooley et al., 2014) (Figure 4).

In addition to the uneven coverage in water quality over time and space, we found a noticeable disconnect between actual violations and local news coverage (Figure 6). Overwhelmingly, LCR was covered more frequently, despite having the smallest share of violations. Meanwhile, VOC and TCR had a significant share of total violations, yet received the least news coverage. This finding is important because local newspapers play an important role in relaying public health risks (De Coninck et al., 2020). Due to the role that local news plays in social constructionism, the lack of coverage for pertinent local water quality concerns may pose a risk to community awareness and responses (Brittle and Zint, 2003; O’Shay et al., 2020). Thus, failure to publish pertinent details regarding local water quality may pose risks to a community’s health, in addition to its ability to organize and respond to unsafe drinking water.

Patterns between news coverage and potential sociodemographic drivers revealed additional insights (Figure 7). Counties receiving news coverage with larger percentages of non-Hispanic white populations had a positive directional relationship with water quality-related news publications, while counties with a larger proportion of Hispanic and Black populations had a negative direction. The difference in risk communication may pose threats to environmental justice, as Black and Hispanic community members are often those most affected by environmental pollutants. Local coverage of environmental risk is indispensable as it informs environmental justice movements (Kern and Kovesi, 2018; Malin and Ryder, 2018; Mohai, 2018). American Indian populations can be diverse in terms of CWS infrastructure, tribal lands, and primacy, which may explain the disparate results found among news coverage (Table 2). For example, the positive direction between American Indian communities and DBP and VOC rules may be a reflection of different water practices, including independent tribal Water Quality Standards (WQSs) and Treatment as a State (TAS), which allow tribes to determine their own water usage and water quality standards (Diver, 2018). Meanwhile, the negative relationship between American Indian communities with TCR, RN, and LCR news coverage may point to the constraints of tribal WQS, which are less effective for non-point source pollution (Diver, 2018). Future research would benefit from studying local variations in news coverage among several different American Indian communities.

Similar to other environmental and health research (Schwarzenbach et al., 2010; Gilligan et al., 2018; Grossman et al., 2020), we observed a relationship between news coverage and political leanings. Specifically, we show a positive relationship between DBP-related coverage and Republican voters water quality news coverage. Previous literature has shown that political leanings can capture multiple endogenous interactions, such as income inequality and populations density (Gilligan et al., 2018). Amongst communities with greater proportions of conservative voters, the positive correlation with drinking water news coverage could be related to political and economic advantages that may be associated with maintaining water resources for community employment opportunities Barnett (2019). Thus, future research could explore the relationship and framing of political leanings and water quality narratives. This might be reflective of the importance of maintaining local economies and water quality/quantity for the sake of future generations, regardless of political affiliation.

Overall, the relationships found in these analyses not only suggest inequitable distribution of news coverage on the topic of drinking water violations, but also they support previous calls for environmental justice to be extended into theories of social constructionism and socio-hydrology Thaler (2021); Taylor (2000). For example, while the inequitable distribution of drinking water quality news coverage not only functions to mediate environmental health messaging to all communities, coverage that is withheld may limit the shared knowledge necessary for communities to organize effectively against environmental injustice Taylor (2000). Meanwhile, the shared social construction and legitimization of inequitable water risk distribution is an indisputable aspect of socio-hydrological systems, an area that has been overlooked to date.

Although data availability was a significant driver of the study focus, some limitations regarding content analysis, spatiotemporal evaluations, and sociodemographic features are worth highlighting. For example, key term filtering does not allow the researcher to grasp tone or the overall summary of an article. Analytical techniques, such as structural topic modeling, sentiment analysis, and Kullback-Leibler Divergence could be implemented to gain greater insights into the narratives and patterns of media coverage for water quality issues (Gunda, 2018). We were also unable to distinguish whether an article was locally authored or licensed from national news sources, which impacted our ability to filter national stories from local ones. Such metadata may explain the national spike in LCR coverage in 2016 relating to the Flint Water Crisis. In addition to text analyses limitations, analyzing the data temporally and regionally posed some challenges. For example, examining violations and news articles that occurred annually failed to fully capture the relationship between water quality violations and the series of decisions made before a news story is published (Hassell, 2021). We also acknowledge that We also acknowledge that while the variables used to combine two ACS 5-year estimates datasets to represent the study period were consistent, this approach requires revisiting due to assumptions in the initial datasets. Furthermore, counties—which were the spatial unit used for news distribution data—are often more coarse than their census or block group counterparts. Additionally, the newspaper corpus used for the analyses only had one source from the Pacific Northwest, which was not as representative as other regions in the United States. For sociodemographic analyses, future studies could further disaggregate Black into Black Hispanic and Black non-Hispanic categories to capture additional nuances within these populations.

Local journalism plays a key role in promoting this social cohesion by reminding community members that local water quality risks impact not only themselves but their neighbors, bridging many divides (Mason, 2016). Thus, this research points to the salience of local journalism in promoting a shared community awareness of drinking water quality and availability. Increasingly, however, local news platforms are being forced to reduce their budgets or close down all together (Hendrickson, 2019). Furthermore, printed news consumption is rapidly shifting towards digital platforms (Trilling et al., 2017). So future research would benefit from the inclusion of other forms of media, such as online news sources, television, social media, or radio, which all serve as highly utilized forms of risk communication (Lazrus et al., 2012; Demuth et al., 2018). Future studies could also extend beyond drinking water coverage to consider patterns in broader environmental and public health issues. Finally, while our results suggested that media coverage among readership regions with greater proportions of foreign born Spanish-speaking individuals may be less available to first-generation Spanish-speaking individuals, our study did not consider non-English news sources. Thus, additional research will be necessary to understand alternative languages of water-related media for regions with a greater proportion of foreign born Spanish-speaking individuals.

This study presented a data-driven approach aimed at understanding local newspaper coverage of water quality issues. The general disassociation between physical violations and news coverage highlights a pressing issue with regards to public health awareness and action. Addressing such issues is especially important given the economic investment needed to address ongoing infrastructural challenges within the United States (Allen et al., 2018). In addition to highlighting the disconnect with actual violations, this work also sheds light on potential social inequity within media coverage. Given that water pollution is increasingly prevalent (Hartmann et al., 2021), with significant burdens among the Black and Hispanic communities (Allaire et al., 2018; McDonald and Jones, 2018), additional attention and research is warranted. Socio-hydrological approaches that continue to elucidate the complex interactions between coupled natural and human systems will increase our understanding and possible ways to mitigate environmental risks within our communities.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study can be found in Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

All authors were engaged in research conceptualization. MC conducted the investigation, created visualizations, and authored the original draft. TG and YM acquired funds, supervised the work, and reviewed/edited the draft.

Funding

This work is funded by the Laboratory Directed Research & Development (LDRD) program at Sandia National Laboratories and Vanderbilt University’s Drinking Water Justice Lab. The authors declare that this study received funding from the Laboratory Directed Research and Development program at Sandia National Laboratories. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

Authors MC and TG were employed by Sandia LLC.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Jonathan Gilligan, Allison Witte, and George Hornberger at Vanderbilt University, who helped conceptualize and download the initial corpus used in this analysis. Sandia National Laboratories (SNL) is a multimission laboratory managed and operated by National Technology and Engineering Solutions of Sandia LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of Honeywell International Inc. for the United States Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration under contract DE-NA0003525. The views expressed in the article do not necessarily represent the views of the United States Department of Energy or the United States Government.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fenvs.2022.770812/full#supplementary-material

References

Allaire, M., Wu, H., and Lall, U. (2018). National Trends in Drinking Water Quality Violations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 2078–2083. doi:10.1073/pnas.1719805115

Allen, M., Clark, R., Cotruvo, J. A., and Grigg, N. (2018). Drinking Water and Public Health in an Era of Aging Distribution Infrastructure. Public Works Manage. Pol. 23, 301–309. doi:10.1177/1087724x18788368

Alliance for Audited Media (2021). Understanding Print Circulation. Lisle, IL: Alliance for Audited Media. [Dataset].

American Society of Civil Engineers (2021). New York Infrastructure Report Card. Reston, VA: American Society of Civil Engineers.

Barnett, C. (2019). The Environmental Issue Republicans Can’t Ignore. Washington, DC: Atlantic Media. The Atlantic.

Brittle, C., and Zint, M. (2003). Do newspapers lead with lead? A Content Analysis of How lead Health Risks to Children Are Covered. J. Environ. Health 65 (10), 17–34.

Burningham, K., and Cooper, G. (1999). Being Constructive: Social Constructionism and the Environment. Sociology 33, 296–316. doi:10.1017/s0038038599000188

Cooley, M. B., Quiñones, B., Oryang, D., Mandrell, R. E., and Gorski, L. (2014). Prevalence of Shiga Toxin Producing escherichia Coli, salmonella Enterica, and listeria Monocytogenes at Public Access Watershed Sites in a california central Coast Agricultural Region. Front. Cel. Infect. Microbiol. 4, 30. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2014.00030

De Coninck, D., d'Haenens, L., and Matthijs, K. (2020). Forgotten Key Players in Public Health: News media as Agents of Information and Persuasion during the Covid-19 Pandemic. Public Health 183, 65–66. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2020.05.011

DelToral, M. (2015). Memo from Miguel Del Toral to Thomas Poy. Chicago, IL: Environmental Protection Agency.

Demuth, J. L., Morss, R. E., Palen, L., Anderson, K. M., Anderson, J., Kogan, M., et al. (2018). Sometimes da# Beachlife ain’t Always da wave”: Understanding People’s Evolving Hurricane Risk Communication, Risk Assessments, and Responses Using Twitter Narratives. Weather, Clim. Soc. 10, 537–560. doi:10.1175/wcas-d-17-0126.1

Diver, S. (2018). Native Water protection Flows through Self-Determination: Understanding Tribal Water Quality Standards and “Treatment as a State”. J. Contemp. Water Res. Educ. 163, 6–30. doi:10.1111/j.1936-704x.2018.03267.x

Egan, P., and Spangler, T. (2016). President Obama Declares Emergency in flint. Detroit, MI: Detroit Free Press.

Ekenga, C. C., McElwain, C.-A., and Sprague, N. (2018). Examining Public Perceptions about lead in School Drinking Water: A Mixed-Methods Analysis of Twitter Response to an Environmental Health hazard. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 15, 162. doi:10.3390/ijerph15010162

Gilligan, J. M., Wold, C. A., Worland, S. C., Nay, J. J., Hess, D. J., and Hornberger, G. M. (2018). Urban Water Conservation Policies in the united states. Earth’s Future 6, 955–967. doi:10.1029/2017ef000797

Griffin, R. J., and Dunwoody, S. (1995). Impacts of Information Subsidies and Community Structure on Local Press Coverage of Environmental Contamination. J. Mass Commun. Q. 72, 271–284. doi:10.1177/107769909507200202

Grossman, G., Kim, S., Rexer, J. M., and Thirumurthy, H. (2020). Political Partisanship Influences Behavioral Responses to Governors’ Recommendations for Covid-19 Prevention in the united states. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 117, 24144–24153. doi:10.1073/pnas.2007835117

Grove, M., Ogden, L., Pickett, S., Boone, C., Buckley, G., Locke, D. H., et al. (2018). The Legacy Effect: Understanding How Segregation and Environmental Injustice Unfold over Time in baltimore. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 108, 524–537. doi:10.1080/24694452.2017.1365585

Gunda, T. (2018). Evolution of Water Narratives in Local US Newspapers: A Case Study of Utah and Georgia. Tech. rep.. Albuquerque, NM (United States): Sandia National Lab. SNL-NM.

Hartmann, A., Jasechko, S., Gleeson, T., Wada, Y., Andreo, B., Barberá, J. A., et al. (2021). Risk of Groundwater Contamination Widely Underestimated Because of Fast Flow into Aquifers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118, e2024492118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2024492118

Hassell, H. J. (2021). What Makes News Newsworthy: An Experimental Test of where a News story Is Published (Or Not) and its Perceived Newsworthiness. The Int. J. Press/Politics 26, 654–673. doi:10.1177/1940161220947321

Hendrickson, C. (2019). Local Journalism in Crisis: Why America Must Revive its Local Newsrooms. The Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/research/local-journalism-in-crisis-why-america-must-revive-its-local-newsrooms/.

Jackson, D. Z. (2017). Environmental justice? Unjust Coverage of the flint Water Crisis. Cambridge, MA: Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy.

Kern, L., and Kovesi, C. (2018). Environmental justice Meets the Right to Stay Put: Mobilising against Environmental Racism, Gentrification, and Xenophobia in chicago’s Little Village. Local Environ. 23, 952–966. doi:10.1080/13549839.2018.1508204

Krauthammer, M., and Nenadic, G. (2004). Term Identification in the Biomedical Literature. J. Biomed. Inform. 37, 512–526. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2004.08.004

Lam, S., Cunsolo, A., Sawatzky, A., Ford, J., and Harper, S. L. (2017). How Does the media Portray Drinking Water Security in Indigenous Communities in canada? an Analysis of canadian Newspaper Coverage from 2000-2015. BMC Public Health 17, 1–14. doi:10.1186/s12889-017-4164-4

Lazrus, H., Morrow, B. H., Morss, R. E., and Lazo, J. K. (2012). Vulnerability beyond Stereotypes: Context and agency in hurricane Risk Communication. Weather, Clim. Soc. 4, 103–109. doi:10.1175/wcas-d-12-00015.1

Levallois, P., Barn, P., Valcke, M., Gauvin, D., and Kosatsky, T. (2018). Public Health Consequences of lead in Drinking Water. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 5, 255–262. doi:10.1007/s40572-018-0193-0

Longo, S. B., Isgren, E., Clark, B., Jorgenson, A. K., Jerneck, A., Olsson, L., et al. (2021). Sociology for Sustainability Science. Discover Sustain. 2, 1–14. doi:10.1007/s43621-021-00056-5

Lytle, D. A., Schock, M. R., Formal, C., Bennett-Stamper, C., Harmon, S., Nadagouda, M. N., et al. (2020). Lead Particle Size Fractionation and Identification in newark, new jersey’s Drinking Water. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 13672–13679. doi:10.1021/acs.est.0c03797

Madani, K., and Shafiee-Jood, M. (2020). Socio-hydrology: a New Understanding to Unite or a New Science to divide? Water 12, 1941. doi:10.3390/w12071941

Malin, S. A., and Ryder, S. S. (2018). Developing Deeply Intersectional Environmental justice Scholarship. Environmental Sociology. doi:10.1080/23251042.2018.1446711

Mason, L. (2016). A Cross-Cutting Calm: How Social Sorting Drives Affective Polarization. Public Opin. Q. 80, 351–377. doi:10.1093/poq/nfw001

McDonald, Y. J., and Jones, N. E. (2018). Drinking Water Violations and Environmental justice in the united states, 2011–2015. Am. J. Public Health 108, 1401–1407. doi:10.2105/ajph.2018.304621

MIT Election Data and Science Lab (2018). County Presidential Election Returns 2000-2020. Washington, DC: U.S. Energy Information Administration. [Dataset]. doi:10.7910/DVN/VOQCHQ

Moreno, A., and Redondo, T. (2016). Text Analytics: the Convergence of Big Data and Artificial Intelligence. IJIMAI 3, 57–64. doi:10.9781/ijimai.2016.369

O’Shay, S., Day, A. M., Islam, K., McElmurry, S. P., and Seeger, M. W. (2020). Boil Water Advisories as Risk Communication: Consistency between Cdc Guidelines and Local News media Articles. Health Commun. 37, 152–162. doi:10.1080/10410236.2020.1827540

Pierce, G., and Gonzalez, S. R. (2017). Public Drinking Water System Coverage and its Discontents: the Prevalence and Severity of Water Access Problems in california’s mobile home parks. Environ. Justice 10, 168–173. doi:10.1089/env.2017.0006

Prasad, A. (2019). Denying Anthropogenic Climate Change: or, How Our Rejection of Objective Reality Gave Intellectual Legitimacy to Fake News. Sociol. Forum 34, 1217–1234. Wiley Online Library. doi:10.1111/socf.12546

Schwarzenbach, R. P., Egli, T., Hofstetter, T. B., Von Gunten, U., and Wehrli, B. (2010). Global Water Pollution and Human Health. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 35, 109–136. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-100809-125342

Silge, J., and Robinson, D. (2017). Text Mining with R: A Tidy Approach. Newton, MA: O’Reilly Media, Inc..

Sivapalan, M., Savenije, H. H., and Blöschl, G. (2012). Socio-Hydrology: A New Science of People and Water. Hydrol. Process. 26, 1270–1276. doi:10.1002/hyp.8426

Tanellari, E., Bosch, D., Boyle, K., and Mykerezi, E. (2015). On Consumers’ Attitudes and Willingness to Pay for Improved Drinking Water Quality and Infrastructure. Water Resour. Res. 51, 47–57. doi:10.1002/2013wr014934

Taylor, D. E. (2000). The Rise of the Environmental justice Paradigm: Injustice Framing and the Social Construction of Environmental Discourses. Am. Behav. Sci. 43, 508–580. doi:10.1177/0002764200043004003

Thaler, T. (2021). Social justice in Socio-Hydrology—How We Can Integrate the Two Different Perspectives. Hydrol. Sci. J. 66, 1503–1512. doi:10.1080/02626667.2021.1950916

Trilling, D., Tolochko, P., and Burscher, B. (2017). From Newsworthiness to Shareworthiness: How to Predict News Sharing Based on Article Characteristics. J. Mass Commun. Q. 94, 38–60. doi:10.1177/1077699016654682

United States Energy Information Administration (2021). Crude Oil Production State Rankings, March 2021. Washington, DC: United States Environmental Protection Agency.

United States Environmental Protection Agency (2021). SDWIS Federal Reports Advanced. Washington, DC: United States Environmental Protection Agency. [Dataset].

United States Environmental Protection Agency (2022). Environmental Justice. Washington, DC: United States Environmental Protection Agency. [Dataset].

US Census Bureau (2021). American Community Survey Data. Washington, DC: United States Census Bureau. [Dataset].

Keywords: drinking water, text analysis, sociodemographic factors, newspaper articles, social constructionism, environmental justice, socio-hydrology

Citation: Caballero MD, Gunda T and McDonald YJ (2022) Pollution in the Press: Employing Text Analytics to Understand Regional Water Quality Narratives. Front. Environ. Sci. 10:770812. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.770812

Received: 05 September 2021; Accepted: 16 March 2022;

Published: 27 April 2022.

Edited by:

Anders Hansen, University of Leicester, United KingdomReviewed by:

Dimitrinka Atanasova, Lancaster University, United KingdomSibo Chen, Ryerson University, Canada

Copyright © 2022 Caballero, Gunda and McDonald. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mariah D. Caballero, bWFyaWFoLmQuY2FiYWxsZXJvQHZhbmRlcmJpbHQuZWR1

Mariah D. Caballero

Mariah D. Caballero Thushara Gunda

Thushara Gunda Yolanda J. McDonald

Yolanda J. McDonald