95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Environ. Sci. , 30 December 2022

Sec. Environmental Economics and Management

Volume 10 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2022.1059906

The automotive industry is set to face a series of fundamental changes in the following years. Along with the transition to electric vehicles or production of autonomous cars, companies are also expected to better address sustainability issues, usually divided into environmental, social and governance (ESG) aspects. The present paper aims to explore the relationship between non-financial sustainability, measured by ESG scores, and firm value in the automotive industry, where empirical evidence is scarce. A structural equation modelling (SEM) approach has been taken on a novel dataset of 131 listed companies worldwide across 6 years. Our results indicate a mixed influence of the E, S, G scores on firm value in the analyzed period, with some inconclusive effects, especially from the social score. The findings are beneficial for investors, fund managers and automotive companies’ executives. Further research directions are also provided.

In a very recent study, elaborated for McKinsey consulting company, Perez et al. (2022), state that companies will have to address their externalities if they want to maintain their social license.

The United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment recommends investors to consider ESG issues when evaluating companies for prospective financial investments.

However, the rate at which the social license translates into companies’ economic and financial sustainability was slowed down by different factors, including the reservations the financial investors still have in setting their investment decisions based on ESG scores, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine. Nevertheless, there are factors which most likely will accelerate the process, such as the global climate changes and the social unrests generated by the world-wide two-digits inflation rate.

In the last 10 years a significant number of papers approached the connection between ESG and company performances (via ROA—return on assets, ROE—return on equity and ROCE—return on capital employed), respectively between ESG and market values (most often Tobin’s Q or company value) using regressions or other statistical instruments for sectors as energy, pharmaceutical, tourism. To our best knowledge there is no research as to date to study the automotive industry using structural equation modelling (SEM).

This paper has a two-fold target: to check how the relation between ESG and company value is significant for the automotive industry, one of the most dynamic and relevant sectors of the global economy (since the literature review presents several opposite points of view regarding the influence ESG has or not upon market value of the companies), respectively how does SEM help reveal the specifics of this relation.

To study the impact of ESG scores on financial performance the current paper uses a unique approach, with market value of the company as a measure for the value creating process and an innovative research design for the automotive sector. We find that the environmental pillar is generally associated with products’ emissions level, whereas the social pillar is widely associated with employees’ satisfaction (Lee, Raschke, & Krishen, 2022). The governance component incorporates all aspects related to shareholders, administration and law obedience.

Firstly, the foundation of current research design is represented by structural equation modelling (SEM). The classic SEM usually includes many well-known linear models, such as multivariate regression, ANOVA, path analysis or factor analysis. One of the main benefits is the flexibility and general framework it provides for modelling complex causal mechanisms, which can be done in a unified way. Some other advantages, which are relevant for this article, are the ability to model reciprocal relationships (two-way causation) and the analysis of longitudinal data. This technique is identified in previous research aimed at measuring the impact of corporate social responsibility on firm value (Jitmaneeroj, 2017), ESG compliance on corporate sustainability (Budsaratragoon & Jitmaneeroj, 2021), as well as corporate governance on sustainability reporting (Janggu, Darus, Zain, & Sawani, 2014).

Sun et al. (2022) used the SEM method to examine the impact of COVID-19 pandemics on small and medium enterprises’ business norms and performances in China, through a survey questionnaire. Their findings confirmed the significant impact of COVID-19 on innovative operational procedures, profitability, remote work, and stakeholder satisfaction and safety.

A recent paper of Behl et al. (2022) also uses SEM to measure the impact of ESG scores on firm value. This paper will be used in the Discussion section as a benchmark for the current analysis, as it will allow measuring more precisely the effect of ESG compliance in the automotive sector versus the energy sector.

Secondly, this paper states that each of the three pillars of ESG should be analyzed individually as their impact on company valuation can differ in direction. According to a study of Ionescu et al. (2019), the influence and significance of each pillar fluctuates according to the geographical location of the company at stake as the legislative frameworks have different implications in different markets. Furthermore, among the three pillars, the environmental one is expected to have the largest impact as the potential derived gains for investors are the easiest to understand (Sultana, Zulkifli, & Zainal, 2018).

Thirdly, this research identifies that the link between ESG investments and any variable of interest has to be framed within a specific sector or industry to avoid heterogeneity (Pellegrini, Caruso, & Cifone, 2019). The automotive sector does not benefit of a plethora of studies in the ESG sphere, as for example, the tourism and pharmaceutical sectors.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows: in chapter two there is a literature review, highlighting the main similar research and their findings, chapter three describes the methodology and data used, the fourth presents the results in a detailed manner, whilst the fifth section is dedicated to a discussion of the findings and their significance. The sixth and final section is concerned with the conclusions, policy implications and future lines of research.

Research papers focusing on investing decisions based on environmental, social and governance criteria have been produced by the scientific community starting with the 1970s and are exponentially growing in numbers (Friede, Busch, & Bassen, 2015). The recent incorporation of ESG principles into investing decisions demonstrates a change in the financial paradigm that goes further than the initial Friedman doctrine (Friedman, 2007) and is found to yield positive financial results (Fatemi, Glaum, & Kaiser, 2018). Currently, there seems to be a consensus amongst investors that an increased ESG performance translates to a higher financial performance.

The following section structures the reviewed ESG literature as follows:

1) Increasing ESG presence in investment decisions

2) The impact of ESG factors on firm value by sectors

3) Observed quantitative approaches and results

4) Hypotheses statement

A growing number of companies from different sectors and locations invest more resources into improving their ESG aspects and activities and making public these efforts via reporting ESG, such as now over 90% of S&P 500 companies publish ESG reports in some form, as well as about 70% of Russell 1000 companies (Perez et al., 2022). Yet again, the opposite applies as those financial analysts which are insensitive to ESG news tend to estimate less accurate forecasts (Derrien, Krueger, Landier, & Yao, 2021). This is no surprise, as investors have a two-fold motivation. On one hand, they seek to maximize profits, while on the other hand they are actively preoccupied of addressing the ESG issues (Amel-Zadeh & Serafeim, 2018).

In a very recent study, elaborated for McKinsey consulting company, Perez et al. (2022), state that companies will have to address their externalities if they want to maintain their social license.

The United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment recommends investors to consider ESG issues when evaluating companies for prospective financial investments.

However, the rate at which the social license translates into companies’ economic and financial sustainability was slowed down by different factors, including the reservations the financial investors still have in setting their investment decisions based on ESG scores, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine. Nevertheless, there are factors which most likely will accelerate the process, such as the global climate changes and the social unrests generated by the world-wide two-digits inflation rate.

Even if companies have recently increased reporting ESG data, the cross-industry comparison and evaluation of companies based on ESG scores are not straightforward. Billio et al. (2021), Jacobs and Levy (2022) showed inconsistencies between the scoring structures of several rating agencies. As such, on one side, both investors and researchers ought to proceed with caution in setting investment decisions based on ESG status and reporting. On the other side, from the company perspective, after market shocks such as the Dieselgate Volkswagen scandal (Leleux & van der Kaaij, 2019), actors in the automotive sector should seek to increase reporting, transparency and adhesion to the ESG principles to increase firm value and attract investors (Wong, Batten, Mohamed-Arshad, Nordin, & Adzis, 2021) (Aboud & Diab, 2018).

Janicka and Sajnóg (2022) studied the quality of ESG reporting in EU public companies (via the ESG-index) and its effect on their market capitalization, using a set of 15,000 companies listed on 27 stock exchanges for the 2002 to 2019 period. The authors found that 50% of the companies listed on old EU member states’ stock exchanges and only 5% of the companies from the new EU member states had reported ESG-indexes in any given year of the research period. Also, they found a positive relationship between companies’ market capitalisation and the quality of their ESG reports, and that companies’ market values are positively, but not strongly affected by the ESG-indexes.

Ademi and Klungseth (2022) investigated the relation between ESG performances and financial performances for 150 Standard and Poor’s listed companies for the 2017-2020 period. The authors found that companies with superior ESG performance perform better (both financially and in market values) compared to their industry peers. Ademi and Klungseth showed that ESG scores have a significant and positive impact upon both accounting measures (via return on capital employed) and market value of companies (via Tobin’s Q).

Regarding the tourism sector, Ionescu et al. (2019) highlighted that in recent years ESG principles were ever more integrated into investors’ decision-making process. Also, Buallay et al. (2022) find a significant relationship between return on assets of tourism companies and the ESG guidelines. Yet again, consistent evidence supports the theory that involvement in the environmental and social spheres is a driving factor for financial performance (Abdi et al., 2022). Nevertheless, the tourism sector includes transportation, hotel and leisure (Bodhanwala & Bodhanwala, 2021) components, with each subsector presenting different levels of ESG compliance. Ceteris paribus, this observation can be hold valid for any analyzed sector.

In the pharmaceutical sector, a positive relation between ESG factors and financial performance was found by López-Toro et al. (2021) using a PLS-SEM methodology. In addition, the integration of ESG pillars in the pharma industry is found to contribute to increased marketing performances (Paolone, Cucari, Wu, & Tiscini, 2021) and towards the fulfillment of the Sustainable Development Goals (Consolandi, Phadke, Hawley, & Eccles, 2020) set by the United Nations. In terms of financial performance, Barbieri and Pellegrini (2022) find an inverted U-shaped relationship between ESG scores and Tobin’s Q.

Conca et al. (2021) studied the case of agri-food sector companies (57 European EU-28 listed companies for the 2010-2018 period). The results of their study showed a positive correlation in case of accounting profitability and a negative one in case of the relation between governance disclosure practices and market value of the companies.

Dincă et al. (2022) used a regression model to find whether the quality of governance influence the nexus between environmental performance and education levels at society level, for a set of 43 countries (EU members and G20 countries) over the 1995-2020 period. Their main results showed that all the independent variables reflecting institutional quality, included in the model, have a direct and positive link to CO2 emissions’ level.

For the automotive industry, previous empirical results on the impact and significance of ESG factors and firm value are relatively scarce and divergent. For this specific sector, besides the previously mentioned Dieselgate scandal, we identify only a few relevant papers. Pellegrini, Caruso, & Cifone (2019) find a positive association between the environmental pillar and ROA, as well as an inversed U shape relation between the governance pillar and ROA. Rossi et al. (2020) confirm this positive relation for the environmental and governance dimensions when using firm market value as a financial indicator.

Irrespective of the statistical tools employed, the scientific community measures company performances from a value creation perspective, using at least three indicators. More precisely, return on assets or ROA, (Pellegrini, Caruso, & Cifone, 2019; Barbieri & Pellegrini, 2022; Buallay, Al-Ajmi, & Barone, 2022), Tobin’s Q (Aboud & Diab, 2018; Wong, Batten, Mohamed-Arshad, Nordin, & Adzis, 2021; Behl, Kumari, Makhija, & Sharma, 2022; Buallay, Al-Ajmi, & Barone, 2022) and enterprise value (Rossi, Minicozzi, Pascarella, & Capasso, 2020) are the main identified proxies for this perspective.

Zhou and Luo (2022) approached the sustainable development of Chinese enterprises and the way listed companies’ ESG performance affects their market value. The authors found that the improvement of listed companies’ ESG performance can enhance the market value of the company with companies’ financial performance having a significant mediating effect. Also, they found operational capacity to be an important facilitator in ESG performance influencing companies’ market value.

Atan et al. (2018) approached the impact of ESG factors upon financial performances and market value (i.e., profitability—ROE, cost of capital and company value—Tobin’s Q) for a panel of 54 selected Malaysian companies for the 2010-2013 period. The authors used panel data regressions which revealed no significant correlations between the individual E, S or G factors or the overall ESG and company profitability, respectively company value (via Tobin’s Q). Also, none of the ESG factors showed any significant correlation with average cost of capital. The only positive and significant correlation seemed to be the one between the combined ESG scores and the company cost of capital. Similar results are to be found in the case of a panel quantile regression in the Chinese stock exchange (Zhang, Qin and Liu 2020).

Constantinescu and Mititean (2020) have studied the correlation between ESG factors’ disclosure and

Market value of 55 European companies from the energy sector, using two linear regressions models. The authors identified a positive correlation between the forementioned variables for the companies located in the Oil and Gas Service and the Renewable energy subsectors and a negative and significant correlation for the companies from the Oil and Gas subsectors.

Exploring the automotive sector through a Generalized Method of Moment (GMM), Lin et al. (2019) find that green practices positively influence financial profitability, especially for lower-sized firms. Nevertheless, through green strategy innovation this respective paper does not account for ESG factors.

Other identified ESG papers focus on shareholder risk (Egorova et al., 2022) or do not specifically focus on the automotive sector (Taliento, Favino and Netti 2019). The latter paper of Taliento, Favino and Netti (2019) is nevertheless interesting as it follows a similar Structural Equation Modelling approach. The current study continues this line of research and provides a deeper perspective inside the automotive sector.

This research studies the impact of ESG standards’ compliance and reporting upon the market value of analyzed companies from the automotive sector to find whether investors and financial markets react to ESG standards as the ones from tourism and pharma industries.

The paper introduces four hypotheses on which the research is centered, respectively one hypothesis for each of the three components (Environmental, Social and respectively Governance) and one for the overall ESG, to find if and how these influence the company value in the subsequent periods.

A novel dataset comprised of ESG and financial data for companies operating in the automotive industry has been gathered at the beginning of 2022. For the timeframe 2015—2020, financial data were obtained from the Morningstar Direct platform and ESG data from Sustainalytics, one of the largest ESG rating company.

Based on the availability of both ESG and financial data, the initial dataset contained 152 companies. ESG data consisted of four variables measured monthly for each company, namely E score, S score, G score and ESG score, while financial data referred to annual enterprise value.

According to Sustainalytics’s ESG Ratings product methodology and definitions, E, S, and G scores were calculated on a scale from 0 to 100 based on a balanced scorecard system, where 0 represented a laggard performance and 100 a top performance for the researched company in the Environment, Social or Governance pillars. The overall ESG Score considered all three before-mentioned scores and was calculated as a weighted average: 25% weight on the E score, 45% on the S score and 30% on the G score. Since all scores had a monthly reporting frequency, the final dataset reports the median ESG/E/S/G score per year for each of the analyzed companies to reflect their annual performance. The annual enterprise value, which is used to measure a company’s total value, was expressed in mil. USD.

The preliminary treatment of data included outliers’ removal and replacement of E/S/G missing data with an aggregate measure based on average past E, S, and G performance. After this step, a final dataset of 131 companies resulted, with six time periods and a total of 3930 data points which have been standardized.

The number of companies in the dataset grouped by region and country is found in Table 1. As it can be observed in this table, the dataset contains companies which are fairly spread around each region of the globe, with the highest number of companies from Japan (25 companies) and the United States (20 companies).

To test the hypotheses presented, a structural equation modelling (SEM) approach is employed, using a cross-lagged panel model (CLPM) with a 6-year wave (T1 to T6) from 2015 to 2020. Compared to other conventional methods, such as time series or linear regression models, the structural equation model allows developing path models that better illustrate causal relationship. Moreover, causal mechanisms are more easily and accurately modelled through this approach by simultaneously analyzing all variables in the model instead of separately (Chin 1998). The cross-lagged panel model, which is a subtype of the broader structural equation models, is highly suitable for determining the lagged effects of one variable to another. This paper focuses on the lagged effect from the ESG score, the independent variable, in time T to firm value, the dependent variable, in time T + 1, controlling for firm value in time T. Additionally, this approach has the advantage of testing for reverse causality, i.e., firm value effects on ESG scores. The conceptual path diagram for this model is illustrated in Figure 1 below.

Table 2 presents a summary of the variables used in the analysis, while Table 3 reports the descriptive statistics for each variable, grouped by year. The skewness of firm value for all years in the analyzed period is relatively high, which indicates the predominance of large firms in the dataset, while the E, S, and G scores are almost symmetrically distributed. This also suggests that ESG data is mostly available for large companies in the automotive industry, which face higher ESG disclosure pressures. Moreover, the positive skewness coefficients for the non-financial variables indicate a bias towards high E, S, and G scores for the companies in our dataset. Analyzing the correlation matrix, which can be found in Table 4 below, it results that the correlation coefficients between E, S, and G scores and firm value in all years are mostly positive, yet less than 0.25.

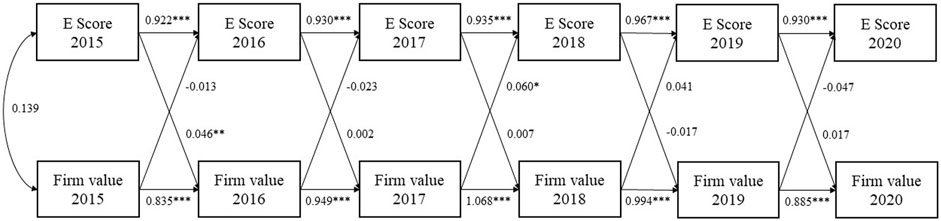

Figure 2 below shows the cross-lagged model between the environmental (E) score and company value. Results indicate a stable temporal behavior of both E score and firm value across all the 6 years analyzed. On the other hand, only one cross-lagged effect from the E score to firm value is statistically significant, from 2015 to 2016, which indicates that the environmental score does not predict firm value in the automotive industry a year later in the analyzed period. The same conclusion can be drawn by analyzing the cross-lagged effect of firm value on the E score a year later, with only one statistically significant effect, from 2017 to 2018.

FIGURE 2. Cross-lagged panel model of environmental (E) score and firm value, with standardized parameters, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

Model fit indices, summarized in Table 4, indicate an overall good fit of the data.

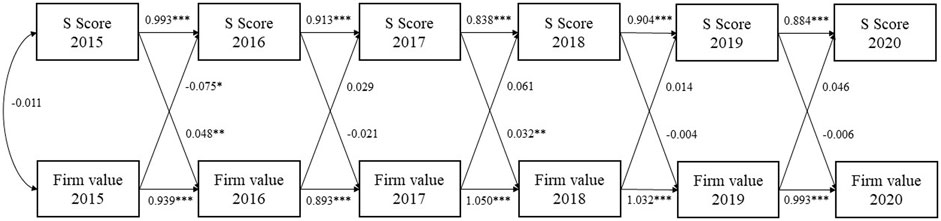

The results for Model two are graphically summarized in Figure 3. Both social (S) score and firm value are temporally stable between 2015 and 2020, while the cross-lagged effects between the two variables are not statistically significant in most cases. This indicates that the S score did not predict firm value a year later, for the period 2015–2020.

FIGURE 3. Cross-lagged panel model of social (S) score and firm value, with standardized parameters, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

The model fit indices are found in Table 4 and indicate an overall poor fit of the data.

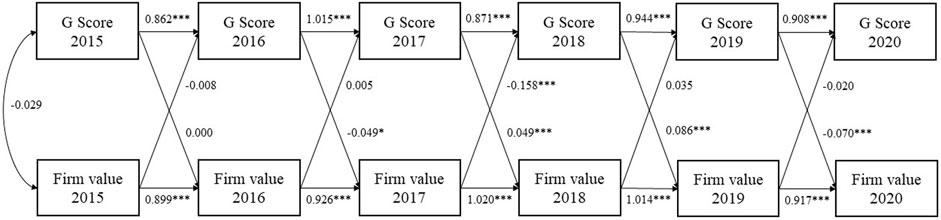

The results for Model three are shown in Figure 4 and indicate a stable temporal behavior for both variables. When it comes to the cross-lagged effect, the governance (G) score can predict firm value a year later, from 2016 until 2020, which is suggested by the statistical significance of the cross-lagged coefficients. Examining the coefficients, we notice a negative significant influence from the governance (G) score in 2016 and 2019, respectively, to firm value in 2017 and 2020, respectively. However, there is a positive significant influence from the G score in 2017 and 2018, respectively, to the firm value in 2018 and 2019, respectively.

FIGURE 4. Cross-lagged panel model of governance (G) score and firm value, with standardized parameters, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

The fit indices for model three are found in Table 4 and indicate a good fit of the data.

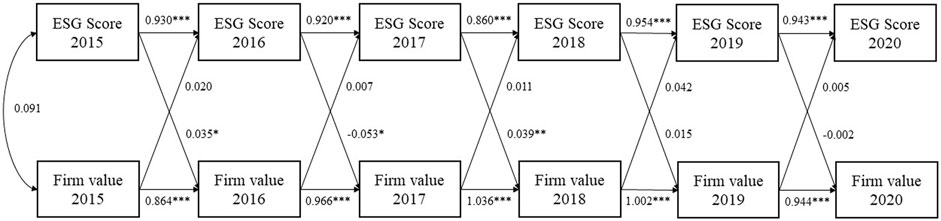

The relationship between the ESG score and firm value in the analyzed period is summarized in Figure 5. Both variables show a stable temporal behavior, with significant coefficients across all periods. A significant cross-lagged effect can be observed from the ESG Score in 2015, 2016, and 2017 to firm value in 2016, 2017, and 2018, respectively. However, the direction of the influence is mixed, with the ESG Score of 2016 having a negative effect on firm value in 2017, while the ESG score of 2015 and 2017, respectively, have a positive effect on firm value in 2016 and 2018, respectively.

FIGURE 5. Cross-lagged panel model of ESG score and firm value, with standardized parameters, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

This current analysis of the relationship between ESG scores and firm value in the automotive industry does not reveal a time-consistent influence of the former on the latter. This contrasts with the few existent studies from the automotive sector and with studies from other sectors, such as tourism, where a positive effect of ESG on firm value has been found using non-structural quantitative models. One can also identify a contrast with results from other studies that used a similar structural modelling approach, specifically from the pharmaceutical sector (López-Toro et al., 2021) and energy sector (Behl et al., 2022), where a positive, significant relationship has been found.

Even though the CLPM results show a positive influence of ESG score on firm value in some years of the analyzed period, this is not stable over time, with many non-significant and even significant negative cross-lagged coefficients found as well. While recent studies point out that actors in the automotive sector should seek to disclose more non-financial information to increase firm value and attract investors, our findings suggest that, in the 2015-2020 period, the financial market of this sector has not reacted to ESG scores changes when it comes to firm valuation. More precisely, investment decision-makers in this sector seem to have been guided by other factors than ESG. This hesitation can also be explained by a lack of standardization of ESG ratings. Investment professionals usually find themselves in the situation to choose their ESG information from a multitude of providers, each with its own research methodology for calculating their scores. Moreover, methodologies have been prone to changes, especially in the analyzed period, as the ESG rating industry has gained significant attention and momentum.

One cannot exclude the possibility of a better model than the one employed in this research, specifically one using additional variables that can increase overall model fit and provide further insights regarding the factors affecting firm value in the automotive industry. Also, the validity of the findings is extremely sensitive to ESG scores’ measurement, therefore a model which uses scores from other ESG data providers can yield different results.

With the expansion of this industry and the overall growth of ESG in recent years, more companies have also been researched from this perspective, therefore increasing the availability and granularity of ESG data. Subsequently, as a future direction of research, we recommend incorporating this new ESG data, particularly for companies in the automotive sector, in other models, not limited to structural equation models, that can provide empirical evidence on the relationship between ESG and firm value. Nevertheless, from a methodological perspective, the structural equation model approach, in the cross-lagged panel model version, can be confidently used to test two-way causation between non-financial and financial data.

Existing literature on the influence of ESG factors on financial performance has mostly concluded that there is a significant, positive influence of the former on the latter. While studies from industries such as pharma, energy or tourism reach this conclusion, evidence in the automotive sector is mostly scarce and divergent. Using a flexible SEM-based procedure, this article provides empirical evidence on the relationship between ESG and firm value for a significant number of companies in this sector and across the globe, over an extended period. As ESG gains momentum in the financial world and companies in the automotive sector face fundamental changes in the way they operate, the results provide a glimpse into how the financial markets in this sector have reacted to non-financial information in the post-Dieselgate period.

The results of this study show that, in the automotive industry, ESG factors have yet to prove their influence on company value, with mixed results coming from our Cross-Lagged Panel Model. Regarding the environmental score’s influence on firm value, there is a significant positive influence only from 2015 to 2016, while the other cross-lagged effects are not significant. For the governance score, there are mixed effects on firm value, specifically a negative effect from 2016 to 2017 and 2019 to 2020, respectively, and a positive effect on firm value from 2017 to 2018 and 2018 to 2019, therefore not supporting the initial hypothesis of a positive significant relationship in the 2015-2020 period. The initial hypothesis for social score was also invalidated. When it comes to the influence of the overall ESG score on firm value, our results also show mixed effects in the first 3 years, and a non-significant influence in the following 2 years. In comparison to Behl et al. (2022), which follows a similar methodology for energy sector companies and the results support some of the hypothesis, the current results do not support any of the hypothesis set initially.

According to the findings of this research, in the analyzed period, the financial market did not react to ESG scores changes in regard to firm valuation. Investors in the automotive sector have been guided by other factors than ESG, partially due to the lack of ESG ratings standardization. Investors have to choose their ESG information from a multitude of providers, each with its own score methodology. Moreover, methodologies have changed, especially in the analyzed period, as the ESG rating industry has gained significant attention and momentum.

The current model can be improved, using additional variables that can increase overall model fit and provide further insights regarding the factors affecting firm value in the automotive industry. At the same time, the database of scores can be extended, using inputs from other ESG data providers, which could generate slightly different results.

Perhaps a correlated effort of representatives of central governments, big equity markets and of international financial institutions could generate a set of generally accepted ESG measures, which can become instrumental in the investment decisions and determine companies to take a pro-active stand in this direction.

In future research, this analysis will be developed, incorporating more companies and a longer period of time. Also, the sources of ESG ratings will be extended and another research method will be used to complement the SEM method, increasing the accuracy and double checking the results.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, MD and C-DV; methodology, C-DV; software, C-DV; validation, MD; formal analysis, MD and C-DV; investigation, C-DV; resources, MD and DD; data curation, C-DV and DD; Writing—original draft preparation, C-DV, MD, and DD; Writing—review and editing, MD, C-DV, and DD; Visualization, DD; supervision, MD; Project administration, MD.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fenvs.2022.1059906/full#supplementary-material

Abdi, Y., Li, X., and Càmara-Turull, X. (2022). Exploring the impact of sustainability (ESG) disclosure on firm value and financial performance (FP) in airline industry: The moderating role of size and age. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 24 (4), 5052–5079. doi:10.1007/s10668-021-01649-w

Aboud, A., and Diab, A. (2018). The impact of social, environmental and corporate governance disclosures on firm value: Evidence from Egypt. J. Account. Emerg. Econ. 8 (4), 442–458. doi:10.1108/JAEE-08-2017-0079

Ademi, B., and Klungseth, N. J. (2022). Does it pay to deliver superior ESG performance? Evidence from US S&P 500 companies. J. Glob. Responsib. 13 (4), 421–449. doi:10.1108/JGR-01-2022-0006

Amel-Zadeh, A., and Serafeim, G. (2018). Why and how investors use ESG information: Evidence from a global survey. Financial Analysts J. 74 (3), 87–103. doi:10.2469/faj.v74.n3.2

Atan, R., Alam, M. M., Said, J., and Zamri, M. (2018). The impacts of environmental, social, and governance factors on firm performance: Panel study of Malaysian companies. Manag. Environ. Qual. 29 (2), 182–194. doi:10.1108/MEQ-03-2017-0033

Barbieri, S., and Pellegrini, L. (2022). “How much does matter ESG ratings in big pharma firms performances?,” in Climate change adaptation, governance and new issues of value. Editors C. Bellavite Pellegrini, L. Pellegrini, and M. Catizone (Cham: Palgrave Studies in Impact Finance. Palgrave Macmillan), 185–225. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-90115-8_9

Behl, A., Kumari, P. S., Makhija, H., and Sharma, D. (2022). Exploring the relationship of ESG score and firm value using cross-lagged panel analyses: Case of the Indian energy sector. Ann. Operations Res. 313 (1), 231–256. doi:10.1007/s10479-021-04189-8

Billio, M., Costola, M., Hristova, I., Latino, C., and Pelizzon, L. (2021). Inside the ESG ratings: (Dis)agreement and performance. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 28 (5), 1426–1445. doi:10.1002/csr.2177

Bodhanwala, S., and Bodhanwala, R. (2021). Exploring relationship between sustainability and firm performance in travel and tourism industry: A global evidence. Soc. Responsib. J. 18 (7), 1251–1269. doi:10.1108/SRJ-09-2020-0360

Browne, M. W., and Cudeck, R. (1992). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociol. methods & Res. 21 (2), 230–258. doi:10.1177/0049124192021002005

Buallay, A., Al-Ajmi, J., and Barone, E. (2022). Sustainability engagement’s impact on tourism sector performance: Linear and nonlinear models. J. Organ. Change Manag. 35 (2), 361–384. doi:10.1108/JOCM-10-2020-0308

Budsaratragoon, P., and Jitmaneeroj, B. (2021). Corporate sustainability and stock value in asian–pacific emerging markets: Synergies or tradeoffs among ESG factors? Sustainability 13 (11), 6458. doi:10.3390/su13116458

Chin, W. W., and Todd, P. A. (1998). On the use, usefulness, and ease of use of structural equation modeling in mis research: A note of caution. MIS Q. 22 (1), 237. doi:10.2307/249690

Conca, L., Manta, F., Morrone, D., and Toma, P. (2021). The impact of direct environmental, social, and governance reporting: Empirical evidence in European-listed companies in the agri-food sector. Bus. Strategy Environ. 30 (2), 1080–1093. doi:10.1002/bse.2672

Consolandi, C., Phadke, H., Hawley, J., and Eccles, R. G. (2020). Material ESG outcomes and SDG externalities: Evaluating the health care sector’s contribution to the SDGs. Organ. Environ. 33 (4), 511–533. doi:10.1177/1086026619899795

Constantinescu, D., and Mititean, P. (2020). “Association of ESG factors' disclosure with the value of European companies from Energy industry,” in 8th International Scientific Conference IFRS: Global Rules and Local Use - Beyond the Numbers, 200–213. Proceedings paper.

Derrien, F., Krueger, P., Landier, A., and Yao, T. (2021). “ESG news, future cash flows, and firm value,” in Swiss finance institute research paper, 21–84. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3903274

Dincă, G., Bărbuță, M., Negri, C., Dincă, D., and Model, L. S. (2022). The impact of governance quality and educational level on environmental performance. Front. Environ. Sci. 10. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2022.950683

Egorova, A. A., Grishunin, S. V., and Karminsky, A. M. (2022). The impact of ESG factors on the performance of information technology companies. Procedia Comput. Sci. 199, 339–345. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2022.01.041

Fatemi, A., Glaum, M., and Kaiser, S. (2018). ESG performance and firm value: The moderating role of disclosure. Glob. Finance J. 38, 45–64. doi:10.1016/j.gfj.2017.03.001

Friede, G., Busch, T., and Bassen, A. (2015). ESG and financial performance: Aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. J. Sustain. finance Invest. 5 (4), 210–233. doi:10.1080/20430795.2015.1118917

Friedman, M. (2007). “The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits,” in Corporate ethics and corporate governance, 173–178.

Hu, L. T., and Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 6 (1), 1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118

Ionescu, G. H., Firoiu, D., Pirvu, R., and Vilag, R. D. (2019). The impact of ESG factors on market value of companies from travel and tourism industry. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 25 (5), 820–849. doi:10.3846/tede.2019.10294

Jacobs, B. I., and Levy, K. N. (2022). The challenge of disparities in ESG ratings. J. Impact ESG Invest. 2 (3), 107–111. doi:10.3905/jesg.2022.1.040

Janggu, T., Darus, F., Zain, M. M., and Sawani, Y. (2014). Does good corporate governance lead to better sustainability reporting? An analysis using structural equation modeling. Procedia-Social Behav. Sci. 145, 138–145. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.06.020

Janicka, M., and Sajnóg, A. (2022). The ESG reporting of EU public companies—does the company’s capitalisation matter? Sustainability 14, 4279. doi:10.3390/su14074279

Jitmaneeroj, B. (2017). The impact of corporate social responsibility on firm value: An application of structural equation modelling. Int. J. Bus. Gov. Ethics 12 (4), 1–329. doi:10.1504/IJBGE.2017.10010709

Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 2nd Edition. New York: The Guilford Press.

Lee, M. T., Raschke, R. L., and Krishen, A. S. (2022). Signaling green! firm ESG signals in an interconnected environment that promote brand valuation. J. Bus. Res. 138, 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.08.061

Leleux, B., and van der Kaaij, J. (2019). “ESG ratings and the stock markets,” in Winning sustainability strategies (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 103–125. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-97445-3_6

López-Toro, A. A., Sánchez-Teba, E. M., Benítez-Márquez, M. D., and Rodríguez-Fernández, M. (2021). Influence of ESGC indicators on financial performance of listed pharmaceutical companies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18 (9), 4556. doi:10.3390/ijerph18094556

Paolone, F., Cucari, N., Wu, J., and Tiscini, R. (2021). How do ESG pillars impact firms’ marketing performance? A configurational analysis in the pharmaceutical sector. J. Bus. Industrial Mark. 37 (8), 1594–1606. doi:10.1108/JBIM-07-2020-0356

Pellegrini, C. B., Caruso, R., and Cifone, R. (2019). The impact of ESG scores on both firm profitability and value in the automotive sector (2002-2016). Tirana, Albania: European Centre of Peace Science, Integration and Cooperation (CESPIC)European Centre of Peace Science, Integration and Cooperation (CESPIC), Catholic University'Our Lady of Good Counsel. (No. 1004).

Perez, L., Hunt, V., Samandari, H., Nuttall, R., and Biniek, K. (2022). Does ESG really matter—and why? McKinsey Quarterly Report. August 2022.

Rossi, M., Minicozzi, G., Pascarella, G., and Capasso, A. (2020). “ESG, competitive advantage and financial performances: A preliminary research,” in 13th annual conference of the EuroMed academy of business (Benevento, Italy: EuroMed Press), 969–986. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12070/44916.

Sultana, S., Zulkifli, N., and Zainal, D. (2018). Environmental, social and governance (ESG) and investment decision in Bangladesh. Sustainability 10 (6), 1831. doi:10.3390/su10061831

Sun, T., Zhang, W. W., Dinca, M. S., and Raza, M. (2022). Determining the impact of Covid-19 on the business norms and performance of SMEs in China. Econ. Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja 35 (1), 2234–2253. doi:10.1080/1331677X.2021.1937261

Wong, W. C., Batten, J. A., Mohamed-Arshad, S. B., Nordin, S., and Adzis, A. A. (2021). Does ESG certification add firm value? Finance Res. Lett. 39, 101593. doi:10.1016/j.frl.2020.101593

Keywords: ESG, non-financial sustainability, firm value, automotive, structural equation

Citation: Dincă MS, Vezeteu C-D and Dincă D (2022) The relationship between ESG and firm value. Case study of the automotive industry. Front. Environ. Sci. 10:1059906. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.1059906

Received: 03 October 2022; Accepted: 16 December 2022;

Published: 30 December 2022.

Edited by:

Mara Madaleno, Universidade de Aveiro and GOVCOPP, PortugalReviewed by:

Denok Sunarsi, Pamulang University, IndonesiaCopyright © 2022 Dincă, Vezeteu and Dincă. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marius Sorin Dincă, bWFyaXVzLmRpbmNhQHVuaXRidi5ybw==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.