- 1School of Management, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, China

- 2China Railway Materials Tianjin Company Limited, Tianjin, China

While central environmental inspection (CEI), a sort of campaign-style enforcement, has been adopted in China to tackle environmental issues, it is unclear if the CEI has promoted industrial structure upgrading. Based on a sample of 279 cities from 2011 to 2018 in China, this study investigates the impact of CEI on industrial structure upgrading and its intrinsic mechanism using the difference-in-differences approach (DID). The results reveal that 1) CEI significantly promoted industrial structure upgrading. 2) Local government environmental attention played a mediating role between CEI and industrial structure upgrading. 3) Heterogeneity analysis revealed that the effect of CEI on industrial structure upgrading differed significantly with regional discrepancies and the officials’ promotion motivation. Specifically, the CEI had greater effects on the eastern region and those cities whose officials have a strong promotion motivation. This study indicates that the central government should continue to promote routine inspection, special inspection, and look-back mechanism construction, thus enhancing the sustainability of the industrial structure upgrading effect. Overall, this study contributes to industrial structure upgrading theoretical research and offers useful insights into the environmental governance of emerging countries.

Introduction

Industrial structure upgrading is a critical factor in achieving sustainable development goals in a country and globally (Zhang and Chen, 2018; Wang et al., 2020; Zheng J. et al., 2021; Wang and Li, 2022). As the second-largest economy in the world, China is shifting its development strategy from high speed to high quality, urgently searching for solutions to industrial structure upgrading. Compared with developed countries, China faced a series of issues such as lower industrial structure hierarchy and industrial structure imbalance.

Environmental regulation is essential to industrial structure upgrading. The empirical findings have not yet created cohesive results. There are three views about this relationship: positive, negative, and curvilinear. First, Porter’s hypothesis suggests that appropriate environmental regulation can generate innovation compensation for firms, such as green technologies, processes, and products, which may improve financial performance and competitive advantages (Popp and Newell, 2012; Yang et al., 2012; Aghion et al., 2013). For example, some studies found that environmental regulation can effectively stimulate industrial structure upgrading (Levinson, 2009; Sen, 2015). Second, the pollution haven theory suggests that increased environmental regulation increases firms’ costs and ultimately inhibits industrial structure upgrading (Jaffe and Palmer, 1997). Due to disparities in regional environmental regulations, polluting firms are incentivized to shift to regions with less stringent regulations, resulting in environmental degradation (Millimet and Roy, 2016; Solarin et al., 2017). For example, a previous study found a pollution haven effect in firm location choice (Kheder and Zugravu, 2012). Millimet et al. (2009) argue that environmental regulation increases firms’ production costs, reduces productivity and profits, and impedes industrial structure upgrading. Alpay et al. (2002) found that environmental regulation is a negative deterrent for the food processing industry in the United States. Finally, some scholars also found that the impact of environmental regulation on industrial structure upgrading is uncertain, i.e., the relationship between environmental regulation and industrial structure upgrading is nonlinear (Zhou et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2018; Chen and Qian, 2020). For example, Chen and Qian (2020) analyzed the dual impact of different types of marine environmental regulation on industrial structure upgrading in the manufacturing industry based on panel data from 2004 to 2017 in coastal areas of China.

Central environmental inspection (CEI) is a command-and-control environmental regulatory tool that incorporates mass mail and phone reports into the process. It is a significant institutional innovation in China’s environmental governance, launched in 2015 and eventually achieved full coverage of 31 provinces in 2018 (Lin et al., 2021; Deng et al., 2022). The CEI mainly checks the local governments’ implementation of environmental policies on behalf of the central government, intending to promote local governments to actively take responsibility for environmental protection (Jia and Chen, 2019; He and Geng, 2020; Li et al., 2020; Xiang and van Gevelt, 2020). Additionally, it spurs firms to actively improve environmental information disclosure (Pan and Yao, 2021), increase environmental protection investment (Wang J. et al., 2022), boost green innovation (Zhang et al., 2022), and enhance total factor productivity (Wang et al., 2021b). The existing literature on the impact of environmental regulations on industrial structure upgrading focuses mainly on the effects of low-carbon city pilots (Zheng J. et al., 2021), ecological compensation mechanisms (Zheng Q. et al., 2021), and green credit policy (Cheng et al., 2022). However, to our knowledge, no study has yet been conducted to discuss how CEI affects industrial structure upgrading. Has the CEI promoted industrial structure upgrading? What mechanism is responsible for the CEI effect?

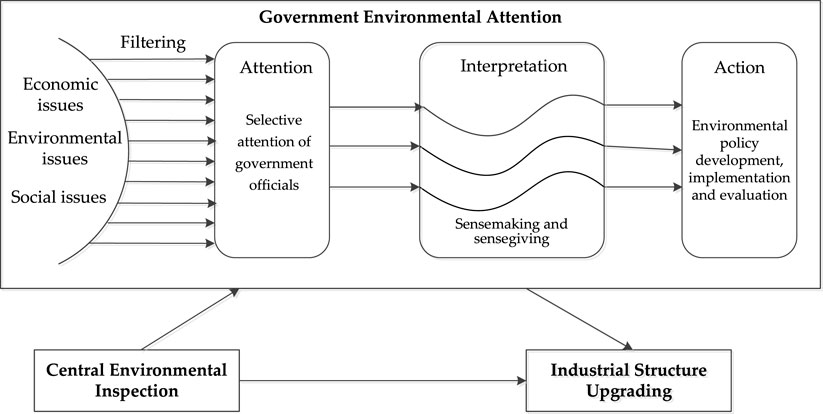

Based on the theory of the attention-based view, we propose that government attention is an essential mechanism for the CEI affecting industrial structure upgrading. The theory states that organizational decision-making depends on which issues decision-makers allocate their limited attention to (Ocasio, 1997). Previous studies that analyze government policy point out that government policy attention can significantly affect policy output (Fan et al., 2022). Thus, how governments allocate their policy attention shapes their subsequent policy outputs. CEI improves government environmental attention through organizational incentive design, internal government communication channels, and public participation. The environmental attention drives local governments to prioritize environmental protection issues in their policy agenda. Local governments will then actively implement green industrial policies and promote industrial structural upgrading. China is vast, and there are great differences in economic development and resource endowment across regions (Zhao et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2021). Based on the environmental Kuznets curve, there are differences between the innovation compensation effect and the compliance cost effect generated by environmental regulation, creating uncertainty regarding the impact of CEI on industrial structure upgrading (Wang L. et al., 2022). Moreover, under a decentralized administrative structure, local officials have easy access to many financial and economic resources, tremendous administrative power to interfere with resource allocation in the market, and the power to make relatively independent economic decisions (Shi et al., 2020). In the context of promotion tournaments, local government officials are more concerned about promotion benefits (Maskin et al., 2000; Chen et al., 2005).

The contributions of our study are threefold. First, we investigate the impact of CEI on industrial structure upgrading, which provides new insights into understanding the relationship between environmental policy and industrial structural upgrading. Second, we reveal the potential mechanism of the CEI affecting industrial structural upgrading from the perspective of an attention-based view. Finally, we analyze the effects of regional development discrepancies and officials’ promotion motivation on the relationship between CEI and industrial structural upgrading, which enriches our understanding of the heterogeneity of CEI policy effects.

Literature review and hypotheses

Central environmental inspection

As a major institutional innovation in China, CEI is a hot topic in environmental governance literature. CEI shifts the focus from inspecting firms to inspecting local governments in environmental governance. The CEI strengthened the environmental responsibilities of local governments through a series of institutional instruments. First, members of the CEI team include leaders from the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection and the Central Organization Department, with a high administrative level. Second, CEI implements the principle of party and government responsibility, which changes the target of inspection from firms to local governments, thus improving the deterrent effect of inspection. Third, CEI links the inspection results to the appraisal and promotion of the local government officials, improving the local government officials’ motivation. Finally, CEI receives reports from the public throughout its presence and is directly accountable for problems. For example, inaccurate investigation and handling of letters and visits and inconsistent feedback on investigation and handling. Under the strict enforcement of CEI and public scrutiny, local governments make more stringent environmental regulations and implement them completely.

Prior studies on CEI have provided a solid foundation and valuable insights. Some focused on CEI’s policy effects (He and Geng, 2020; Li et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2021). Jia and Chen (2019) found that CEI positively impacted environmental performance and that this effect continued after CEI ended. Xiang and van Gevelt (2020) also pointed out that CEI effectively identified and corrected environmental regulation violations. Another stream of studies examined how CEI affects firms. Wang J. et al. (2022) found that CEI increases firms’ investment in environmental protection. Deng et al. (2022) found that CEI facilitates firms’ innovation and improves their performance. Local governments influence firms’ environmental actions by closing polluting firms, reducing their production scale, or incentivizing them to reduce pollution emissions. As a result, the firms reduce their carbon emissions (Wang et al., 2021a). Also, the CEI improves firms’ environmental information disclosure (Pan and Yao, 2021).

However, there are two gaps in the existing literature: one is how CEI influences industrial structure upgrading, the other is the mechanism of CEI’s influence on local government, industry, and firms. Introducing Ocasio’s theory of attention-based view, this paper examines CEI’s impact on industrial structure upgrading and the potential mechanism of working to enrich the existing knowledge.

The attention-based view

The attention-based view is a theory of organizational decision-making and action developed by Ocasio (Ocasio, 1997). He defines organizational attention as the process of “noticing, encoding, interpreting, and focusing of time and effort by organizational decision-makers on both 1) issues (…) and 2) answers”. Issues refer to the categories available to understand the environment, including problems, threats, and opportunities. Answers refer to the available options for action, including recommendations, routines, projects, plans, and procedures. According to Ocasio’s model, issues and answers are conveyed and distributed into specific procedures and communication channels. Attention is situated in these channels and their interactions condition managers’ attention. The attention-based view has three principles: the focus of attention (i.e., what decision-makers do depends on their attention), situated attention (i.e., what decision-makers focus on and do depends on the specific situation), and the structural distribution of attention (i.e., the situation in which decision-makers find themselves, and how they focus on it, depends on rules, resources, social relationships, and the allocation of the decision-makers attention to specific activities, communications, and procedures) (Ocasio, 1997). Attention is not a unitary concept but is used differently in various metatheories. At the level of the brain, neuroscientists have identified three types of attention: selective attention, executive attention, and vigilance. The organizational theory offers an alternative to theories of structural determinism or strategic choice (Ocasio, 2011). Ocasio et al. (2018) propose a broader role for communication as a process by which actors can attend to and engage with organizational and environmental issues and initiatives.

In public policy research, why and how issues gain political attention becomes essential to research related to agenda-setting and policy-making (Jones et al., 2003; Jones and Baumgartner, 2005; Nowlin, 2011). A few studies have begun to focus on the role of government attention (May et al., 2008; Mortensen and Green-Pedersen, 2014; Fan et al., 2022). We define government attention as the process of noticing, encoding, interpreting, and focusing time and effort by government decision-makers on issues and answers. The attention-based view of government provides new perspectives to test classical and cutting-edge public policy research questions.

The logic of industrial structure upgrading under CEI

Industrial structure upgrading refers to the process or trend of the continuous transformation of industrial structure from low-level to high-level forms (Song et al., 2021). According to the pollution haven hypothesis, pollution-intensive firms tend to relocate to areas with less stringent environmental regulations to reduce production costs when faced with environmental regulations (Copeland and Taylor, 1994). As a widespread enforcement action, CEI increases the strength and scope of the environmental regulation of local governments, which effectively avoids the phenomenon of pollution haven. In this case, high-pollution firms may be forced to shut down (Wang et al., 2021a) or undergo a transformation and upgrade by enhancing their technology (Zhang et al., 2022), contributing to the transformation of the industrial structure from low to high.

Government environmental attention refers to noticing, encoding, interpreting, and focusing time and effort by government decision-makers on environmental protection issues and answers. We propose CEI can influence local government attention and thus industrial structure upgrading through the attention-based view (Ocasio, 2011). First, the incentive system influences the distribution of government attention among tasks (Baker, 1992; MacDonald and Marx, 2001). In China’s centralized political system, higher-level governments have the power to make decisions on performance evaluation and personnel appointments for lower-level governments. CEI communicates to local governments the concerns of the central government about environmental issues. Local governments allocate more attention to environmental issues to gain an advantage in the promotion tournament. Second, communication within the government can also affect the focus of government attention (Ocasio, 1997; Ocasio et al., 2018). The team of CEI transferred the main issues and rectification tasks to the provincial governments through the inspection report, leading to rectification meetings with each provincial government. Communication between provincial and municipal governments has been strengthened, prompting local governments to pay attention to environmental issues. Third, CEI strengthens the environmental attention of local governments through bottom-up public participation. Public participation in environmental protection can convey the actual status of environmental governance in its jurisdiction. Studies have shown that complaints from residents within a jurisdiction can increase the environmental attention of local governments (Koontz and Thomas, 2006).

The theory of the attention-based view states that decision-makers cannot allocate their attention casually lightly because of the constraints of the external environment (Ocasio, 1997; Ocasio, 2011). As a form of external pressure, CEI changes the decision-making situation of local governments. The bottom-up model directs local governments to allocate their attention to environment-related issues. Under the guidance of the new policy, local governments will take the initiative to make environmental protection a constraint in formulating and implementing industrial policies. The CEI increase the sense of urgency among policymakers to address environmental issues and thus prioritize them in the policy agenda.

In summary, CEI drives local government attention to environmental issues. After the government focuses on environmental issues, the green innovation capacity of firms is improved through policy subsidies, which facilitates the development of green industries from the demand side, thus promoting industrial structure upgrading. Based on the above analysis, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1: Central environmental inspection significantly promotes industrial structure upgrading.

H2: Local government environmental attention plays a mediating role between central environmental inspection and industrial structure upgrading.

The theoretical framework of this study is shown in Figure 1.

Methodology

Data

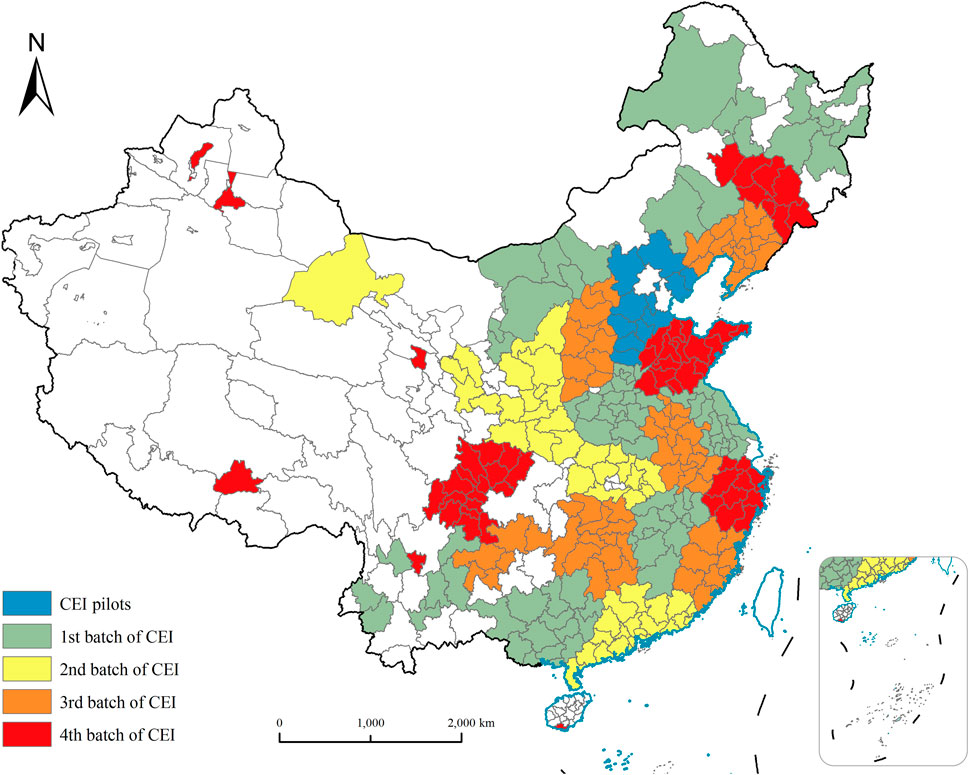

In 2015, a pilot program for CEI started in Hebei province. As of 2018, the CEI covered all 333 prefecture-level administrative regions (293 prefecture-level cities) in 31 provinces, municipalities, and autonomous regions across the country. Because there are no prefecture-level cities in municipalities, four of them were left out. Samples with missing data were also removed. Finally, the samples used in this study covered a total of 268 prefecture-level cities in 27 provinces and autonomous regions (Figure 2 labels the distribution of cities for the CEI pilots and the four batches of CEI). We adopted the samples published in the 2018 China Urban Statistical Yearbook and limited the timeframe from 2011 to 2018. This period was chosen for the following reasons. First, it fully covered the first round of CEI, which began on 31 December 2015, and achieved full coverage across the country in 2017. Thus, this period provided suitable data to assess the policy impact. Second, because the second round of CEI launched on 15 July 2019, some regions may have been inspected twice while others only once, which may have affected the results. In addition, the second round of CEI expanded the subject to central enterprises. In this round, the inspection directly supervises central state-owned enterprises’ without going through the local government, deviating from our study’s focus.

We collected the CEI data from the Ministry of Ecology and Environment and the official websites of various local governments. The control variable data were obtained comes from China City Statistical Yearbook; government environmental attention data from WinGo textual analytics database (www.wingodata.com); and local government data from the government work report on official websites, China Statistical Yearbook, and other authoritative websites (e.g., People.com.cn, Xinhuanet.com).

Measurement of variables

Industrial structure upgrading (IND). The upgrading of industrial structure refers to transforming industrial structure from low-level forms to high-level forms according to the history and logical sequence of economic development. Drawing on existing studies (Song et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2021; Zheng J. et al., 2021), we adopt the industrial structure hierarchical coefficient to quantitatively describe the evolution process of industries from the relative changes in proportion to reflect the dynamic process of industrial structure upgrading fully. The specific measurement formula is:

Central environmental inspection (CEI). Considering that there will be a delay in the effect of the CEI on the industrial structure upgrading, we assign values according to the following criteria: When the CEI is stationed in the first half of the year, we assign a value of one for that year and beyond (following year and beyond); all other cases are 0.

Government environmental attention (gea). We measure government environment attention using the government work report and WinGo textual analytics database. The content of the government work report mainly includes a review and summary of the government’s work in the past year and a summary and plan of the government’s various tasks in the current year. Thus, it measures the government’s attention.

Step 1: Extract the theoretical keywords. According to the definition of government environmental attention, the following theoretical keywords are extracted: environmental protection, pollution prevention and control, public health, ecological civilization construction, and sustainable development.

Step 2: Expand the theoretical keywords. We use the WinGo textual analytics database to calculate similar words for each theoretical keyword. WinGo is a text analysis platform that utilizes a machine learning approach. It uses a deep learning word-embedding model to calculate the word similarity. The greater the similarity, the more similar the semantics and syntax of the two words are. After categorizing and filtering similar words, we update the theoretical keywords and obtain new theoretical keywords.

Step 3: Repeat Step 2 until the theoretical keywords and similar words become saturated. Saturation means that no further new and different similar words appear.

Step 4: Determine the final keywords. The keywords are determined based on the theoretical keyword word frequency. We finally select theoretical keywords with word frequencies greater than 100 as the keywords of concern for the government environment.

Step 5: Count the keyword word frequencies and the ratio of the number of word frequencies to the total number of words in the text.

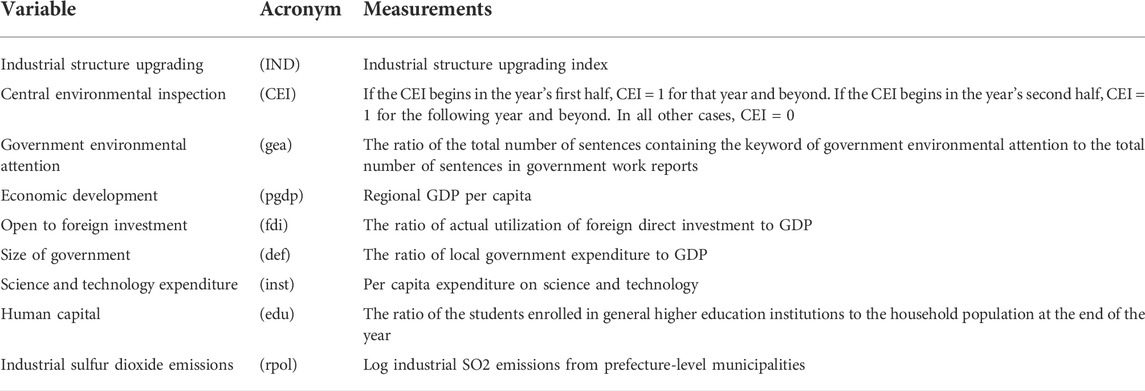

Control variables. A series of control variables are selected based on previous studies, including level of economic development, i.e., regional GDP per capita (pgdp), degree of openness to the outside world (fdi), size of government (def), science and technology expenditure (inst), human capital (edu), and industrial sulfur dioxide emissions (rpol). All variables and their measurements are shown in Table 1.

Model setting

The CEI as an exogenous event provides a quasi-experimental opportunity to solve the endogeneity problem using DID (Beck et al., 2010). The experimental group in this study consists of prefecture-level cities with CEI from 2016 to 2018, and the control group consists of prefecture-level cities without CEI. In addition, the entry time of the CEI is not uniform. We adopt the DID with inconsistent time points for estimation to accurately identify these policy effects. The baseline regression model is

Results

Descriptive statistical analysis

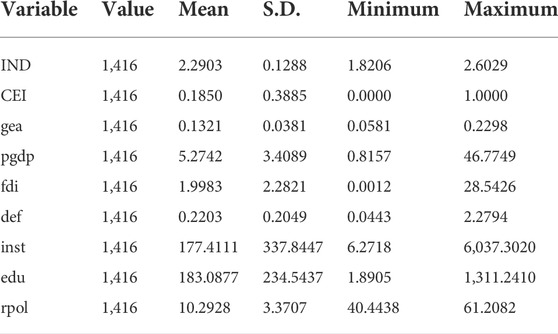

To ensure consistency, we removed the missing values and kept 1,416 observations. Descriptive statistics of the main variables are shown in Table 2. The maximum value of industrial structure upgrading is 260.29, and the minimum value is 202.66. The difference provides a basis for a follow-up empirical study using DID. The average CEI is 0.1850, which means that 18.5% of the sample cities in 9 years are pilot cities.

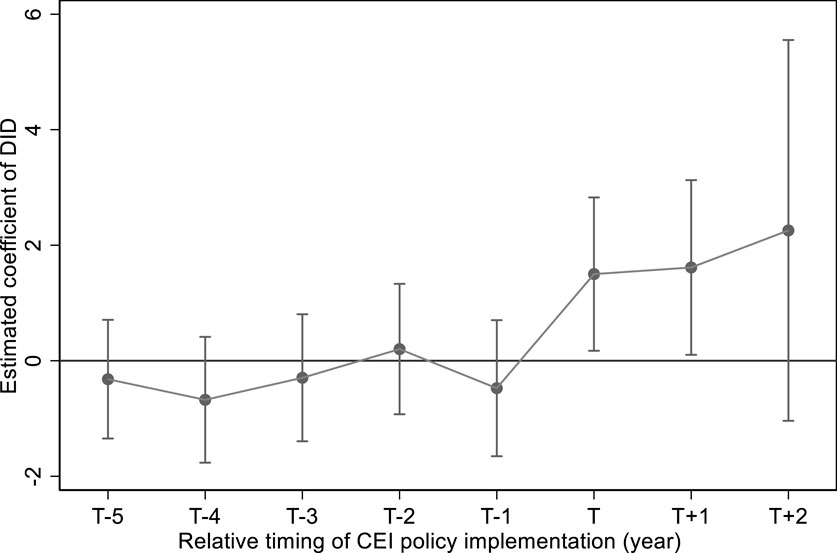

Parallel trend

Before applying the DID, it is necessary to test whether the experimental and control groups satisfy the parallel trend assumption. Before introducing the CEI policy, the industrial structure upgrading index of inspected and non-inspected prefecture-level cities should be parallel (Beck et al., 2010). Drawing on Beck’s study (Beck et al., 2010), we analyzed the dynamic distribution of industrial structure upgrading between the inspected and non-inspected cities. Figure 3 shows the effect of policy dynamics on industrial structure upgrading. As shown in the figure, the coefficients before the CEI are not significantly different from 0 (the 95% confidence interval has a value of 0), which means that there is no significant difference between the treatment and control groups before the CEI point T. This means that the parallel trend hypothesis is true. However, the coefficients after the CEI are significantly positive, which means the CEI has a significant effect. In the year the CEI arrived and the first year following the CEI, the regression coefficients are significant at the 5% confidence level. However, it is not significant the next year after the inspection. The above results suggest that the CEI can significantly promote industrial structure upgrading after it is conducted, but the policy effect gradually disappears as time progresses.

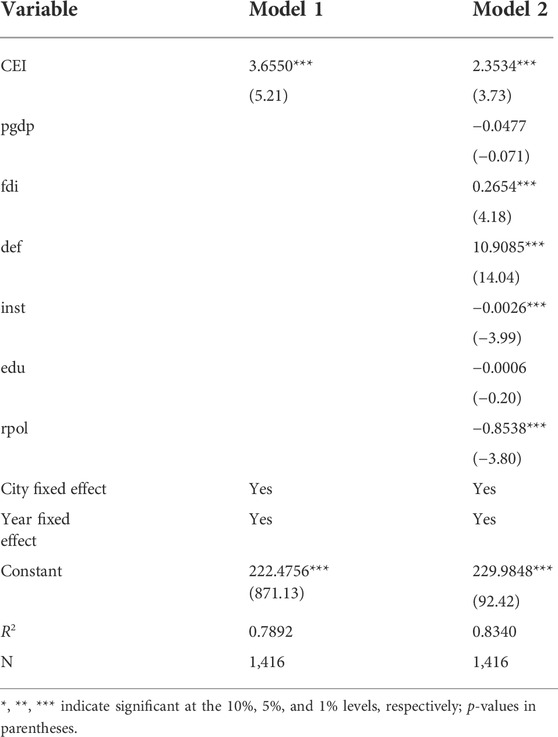

Analysis of baseline regression

The DID was used to test the policy effects of implementing the CEI, and the results are shown in Table 3. Models one and two show the direct effect of CEI on industrial structure upgrading. The results indicate that the estimated coefficients of CEI are positive and significant at the 1% level. After considering the effects of other variables, the entry of the CEI leads to an increase of about 2.3534 percentage points in the industrial structure upgrading index. It shows that the CEI helps change the local industrial structure from being dominated by primary industries to being dominated by secondary and tertiary industries. Therefore, the CEI significantly positively impacts local industrial structure upgrading. Hypothesis one is verified.

Robustness check

Single-difference method. We use the single-difference method to test the robustness of the impact of the CEI on industrial structure upgrading. The results shown in Supplementary Appendix SA. indicate that the estimated coefficients of CEI are significantly positive with or without the inclusion of control variables. The coefficients are significantly higher than those estimated by the DID, which indicates that the single-difference method overestimates the effect of CEI on industrial structure upgrading. This result suggests that the DID can consider the city fixed and time effects, making results more reliable.

Counterfactual tests. Some unobservable factors driving industrial structure upgrading and CEI may affect the validity of results. To exclude such confounding factors unrelated to the CEI, we uniformly advance the entry time of the CEI team in each city by 2–5 years (Before2-Before5). As shown in Supplementary Appendix SA, the results reveal that none of the coefficients of Before2-Before5 are significant, indicating that the change in industrial structure upgrading was driven by the CEI rather than other factors.

Exclude the impact of concurrent events. Given that the policy of environmental interviews between 2011 and 2018 may impact some heavily polluted cities, we removed the prefecture-level cities within the sample after conducting the interviews and regression tests, as shown in Supplementary Appendix SA. It demonstrates that results are consistent with the original results regardless of whether control variables were added. Therefore, the robustness of the results was verified.

PSM-DID. The PSM method was adopted to reduce the estimation bias by applying the DID, thus effectively estimating the causal effect. We conducted Logit regressions with the control variables as covariates and the prefecture-level cities after CEI as dummy variables. There are seven matching methods chosen in this paper, which are one-to-one matching, caliper matching (cal = 0.25*Standard deviation of propensity score), nearest-neighbor matching (K = 2, cal = 0.25*Standard deviation of propensity score), kernel matching (epan kernel, bandwidth 0.06), local linear regression matching (tricubic kernel, bandwidth 0.01), spline matching, and Mahalanobis matching (Heteroskedasticity-Robust Standard Error). The matching process uses common support.

We performed a balance test to verify the reliability of the matching results, as shown in Supplementary Appendix SA. If the absolute value of the normalized deviation value of the matching variable is significantly less than 20, it could be considered appropriate and the matching estimation results are reliable (Feng et al., 2021). Meanwhile, most p values were significantly greater than 0.1, indicating no significant systematic difference between the matched treatment group and the control group. The empirical results of different matching methods are consistent with the baseline regression results. Therefore, the results prove that CEI has a significant positive impact on industrial structure upgrading.

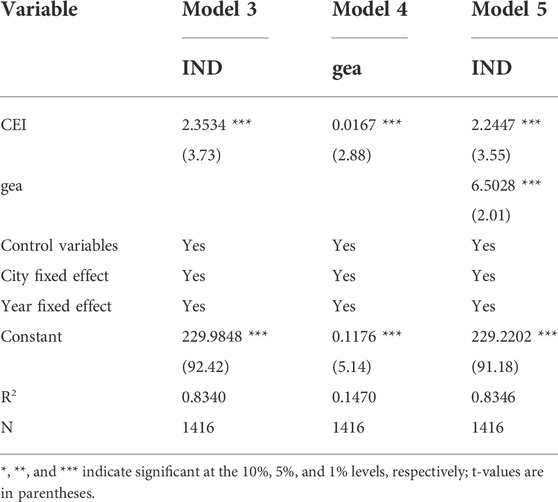

Mechanism analyses

We developed the following steps based on previous studies (Baron and Kenny, 1986) to test the mediating role of government environmental attention, In step 1, we use Eq. 3 to estimate the impact of the CEI on industrial structure upgrading.

In step 2, we use Eq. 4 to estimate the effect of local government competition on environmental attention.

In step 3, based on Step 1 and Step 2, we use regression Eq. 5 to estimate the joint effect of CEI and government environmental attention on industrial structure upgrading. The control variables are the same as above.

The results of the mediating effect test are shown in Table 4. In model 3, the coefficient of the explanatory variables is positive, indicating that the CEI can significantly increase the local government’s attention to environmental issues. Model five demonstrates the regression model results with included independent and mediating variables. The results indicate that the coefficients

To avoid the bias of the stepwise method (Baron and Kenny, 1986), we further re-test the mediating effect by the bias-corrected nonparametric percentile Bootstrap method (Preacher and Hayes, 2008). We use the Bootstrap plug-in to test the relationship between CEI and industrial structure upgrading with a 95% confidence interval and 5,000 replicate sampling settings. As shown in Supplementary Appendix SA, the empirical results indicate that government environmental attention partially mediates between the CEI and industrial structure upgrading, accounting for 4.61% of the total effect. Thus, hypothesis two is verified again.

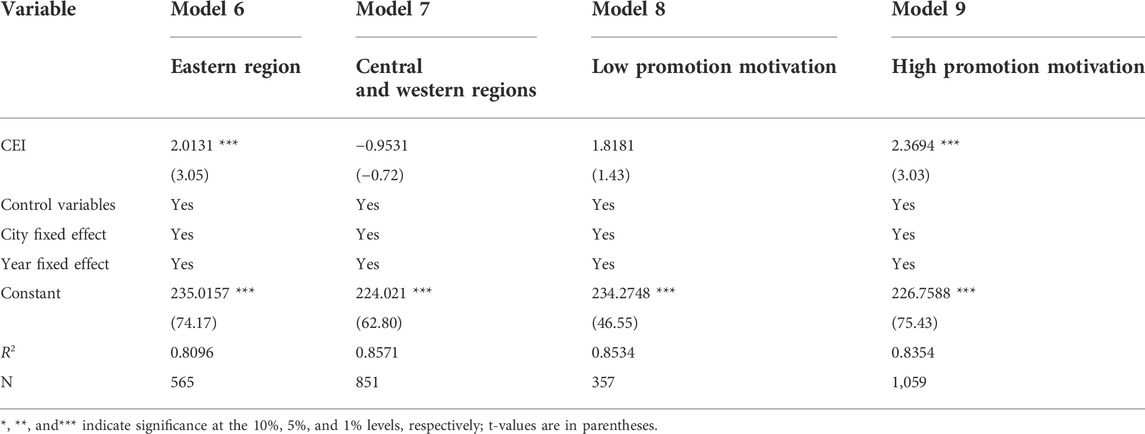

Heterogeneity analysis

Regional heterogeneity. Given the large differences in regional development in China, we divided the sample into eastern, central and western regions for the heterogeneity test. The regression results are shown in Table 5. The results reveal that the effect of CEI on industrial structure upgrading is only significantly positive in the eastern region.

These results may be attributed to the good geographical location of the eastern region. The region belongs to the more developed coastal region. Its high investment attraction ability, government financial resources, and technology development capability have laid a good foundation for upgrading industrial structures. In contrast, the central and western regions have slower regional economic development, a weaker accumulation of talent, and lower levels of science and technology, achieving economic growth through high energy consumption and high pollution. Therefore, under the CEI’s policy of equal treatment, the effectiveness of industrial structure upgrading is limited.

Promotion motivation of officials. Motivation can guide behavior and drive people towards a set goal (Weiner, 1985). At the micro-level, officials are the direct subjects of the diversity of government behaviors, and the various characteristics exhibited by the government manifest officials’ motivation (Gong et al., 2021; Jiang and Li, 2021). Local government officials are generally concerned about promotion benefits under China’s political and economic decentralization systems (Maskin et al., 2000; Chen et al., 2005). Therefore, promotion motivation is a key factor influencing policy formulation and local government implementation.

Promotion motivation refers to the psychological tendency or motivation that drives local government officials to obtain promotion benefits. It is a special psychological state in which local governments tend to obtain the benefits of promotion by their concrete actions under the influence of the environment. The lifetime system for leading cadres was discontinued when the Communist Party of China’s Central Committee established a retirement scheme for old cadres [Zhongfa (1982) No. 13]. It stated that officials could not continue serving after age 65. Therefore age is a key factor affecting the promotion of local officials. In contrast, younger officials have better career prospects and higher expectations for future promotion. This study measures their promotion motivation by age in office. Studies have shown that once prefecture-level city secretaries and mayors are over 54, the probability of promotion drops significantly. Hence, they prefer to retire to the second line (Ji et al., 2014). Because the mayor is usually responsible for economic and social construction in the traditional party-political division of labor, this study grouped the mayors of the prefecture-level cities according to the age cut-off of 54 years to test the industrial structure upgrading effect of the CEI separately. The results are shown in Table 5.

Officials’ personal information was obtained through collecting and collating public information on the Internet, such as Xinhua, People’s Daily Online and Baidu Encyclopedia. The collection of officials’ data is based on the following principles: 1) each city matched only one mayor per year; 2) if the city experienced more than one mayor in power within a year, the mayor whose term of office exceeded half a year was selected as the incumbent official of that year; 3) if the prefecture-level city experienced more than one mayor in that year and the term of office did not exceed half a year, the one with the longest term of office was selected. For cases where the starting year of the mayor’s tenure could not be determined, the gaps were checked by checking the current news.

The results show that the effect of CEI on industrial structure upgrading is only significant in the group of local government principal officials with high promotion motivation. One of the possible explanations is that after the CEI makes environmental performance part of the assessment, the local government officials in charge will face the pressure of both economic and environmental performance assessment. Local government officials with higher promotion incentives will try to promote upgrading industrial structures in their jurisdictions to achieve their promotion goals. In contrast, local government officials with lower promotion motivation will only focus on completing environmental assessment indicators to avoid environmental accountability. The typical strategy they use to solve issues is one-size-fits-all and superficial, which cannot be viewed from the perspective of the economy and the environment developing together. It makes it hard for the CEI to fully consider the effect of upgrading the industrial structure.

Conclusion and discussion

We focus on the effect of CEI on industrial structure upgrading and reveal several valuable insights. First, our study indicates that CEI significantly promoted industrial structure upgrading, and the robustness test supports this finding. It is in line with previous studies that have highlighted the positive impact of CEI on corporate environmental investment, total factor productivity, and air quality (Wang et al., 2021b; Lin et al., 2021; Wang J. et al., 2022). The results demonstrate that CEI, an institutional innovation in China, improves local government environmental regulation and promotes industrial structure upgrading. Second, local government environmental attention partially mediates between CEI and industrial structure upgrading. In line with the literature on the attention-based view (Ocasio, 1997), our study reveals that CEI prompts local government officials to allocate more attention to the issues related to environmental protection and green development, thus effectively contributing to industrial structure upgrading. Third, the effect of CEI on industrial structure upgrading varies in terms of different regions and prefecture-level cities, which is consistent with the related research on regional heterogeneity (Chen et al., 2021). Specifically, on the one hand, CEI has a significant improvement effect on industrial structure upgrading in the eastern regions. Still, this effect is not significant in the central and western regions. On the other hand, local governments whose officials have greater promotion motivation are more sensitive to the CEI, resulting in a higher impact of the CEI on industrial structure upgrading.

The contributions of this study are threefold. First, we link the CEI and industrial structure upgrading, enriching the current literature. Panel data from prefecture-level cities in China confirms that CEI can significantly promote industrial structure upgrading, providing new insights for understanding the relationship between central environmental policy tools and local industrial structure upgrading. Second, this study opens up a new avenue of research and expands on the previous literature. Based on the attention-based view (Ocasio, 1997), we propose and verify the mediating role of government environmental attention between the CEI and industrial structure upgrading, thus contributing to previous studies by revealing the underlying mechanism of this policy effect from a unique research perspective. Finally, we provide more empirical evidence for the relevant literature by examining regional discrepancies and the heterogeneity in the promotion motives of local government principal officials (Pan and Yao, 2021; Wang, 2021). Our findings validate the heterogeneity mentioned above in the constraining role of CEI in exerting policy effects on industrial structure upgrading, thus reinforcing the conclusions of the existing literature.

Given the above findings, the following policy recommendations should be considered. First, the normalization of the CEI ought to be taken seriously. Our study shows that CEI can effectively disrupt the low-level equilibrium of environmental regulations and promote industrial structure upgrading by increasing the intensity of local government environmental regulation. Therefore, in the normalization of the construction of the CEI, the central government needs to continue to promote routine inspection, special inspection, and look-back mechanism construction, enhancing the sustainability of the industrial structure upgrading effect (Shao et al., 2021). Second, the CEI should be institutionalized. A high enough level of positive incentives and strong enough accountability and punishment can improve the environmental attention of local governments through internal drive and external pressure. Improving the public participation mechanism is also necessary for the CEI system, which needs to be enhanced by establishing public complaint channels and response mechanisms. Third, both central and local governments need to translate perception into action. Local governments must take several steps to improve green innovation support policies, improve communication and coordination between different departments, and swiftly address issues with policy implementation. It is not sufficient for them to pay more attention to environmental issues. These measures can enhance the recognition and execution of the policy implementation process and clear the obstacles to industrial structure upgrading. Fourth, the differential enforcement system of CEI needs to be improved. Differentiated environmental goals can provide more financial support to regions with high environmental pressure and more backward economic development. Given the differences in the economic base, technology level, and talent accumulation between the eastern and western regions, it is necessary to consider the characteristics of different cities to realize CEI’s industrial structure upgrading effect fully. Finally, the scope of the accountability of the CEI should be broadened. This study reveals that CEI cannot effectively exert the industrial structure upgrading effect when local government principal officials have low promotion motivation. The CEI assessment objectives should be changed from focusing on ecological and environmental protection to promoting coordination between social development and environmental protection. In addition, one-size-fits-all approaches should be avoided and the phenomenon of perfunctory and superficial rectification by local governments should be improved. Thus, the CEI can become an institutional guarantee to promote economic development and environmental protection.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, BW and JW; methodology, BW; writing original draft preparation, BW and CM; visualization, CM; supervision, JW; funding acquisition, JW All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 71972094.

Conflict of interest

CM was employed by company China Railway Materials Tianjin Company Limited.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fenvs.2022.1030653/full#supplementary-material

References

Aghion, P., Van Reenen, J., and Zingales, L. (2013). Innovation and institutional ownership. Am. Econ. Rev. 103, 277–304. doi:10.1257/aer.103.1.277

Alpay, E., Kerkvliet, J., and Buccola, S. (2002). Productivity growth and environmental regulation in Mexican and US food manufacturing. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 84, 887–901. doi:10.1111/1467-8276.00041

Baker, G. P. (1992). Incentive contracts and performance measurement. J. Polit. Econ. 100, 598–614. doi:10.1086/261831

Baron, R. M., and Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 51, 1173–1182. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

Beck, T., Levine, R., and Levkov, A. (2010). Big bad banks? The winners and losers from bank deregulation in the United States. J. Finance 65, 1637–1667. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.2010.01589.x

Chen, B., Ren, M. T., and Chen, L. Y. (2021). Impact analysis of large-scale environmental Spot inspection policy on green innovation: Evidence from China. Front. Environ. Sci. 9, 676413. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2021.676413

Chen, X., and Qian, W. (2020). Effect of marine environmental regulation on the industrial structure adjustment of manufacturing industry: An empirical analysis of China’s eleven coastal provinces. Mar. Policy 113, 103797. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2019.103797

Chen, Y., Li, H., and Zhou, L. A. (2005). Relative performance evaluation and the turnover of provincial leaders in China. Econ. Lett. 88, 421–425. doi:10.1016/j.econlet.2005.05.003

Cheng, Q., Lai, X., Liu, Y., Yang, Z., and Liu, J. (2022). The influence of green credit on China’s industrial structure upgrade: Evidence from industrial sector panel data exploration. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29, 22439–22453. doi:10.1007/s11356-021-17399-1

Copeland, B. R., and Taylor, M. S. (1994). North-south trade and the environment. Q. J. Econ. 109, 755–787. doi:10.2307/2118421

Deng, X., Huang, B., Zheng, Q., and Ren, X. (2022). Can environmental governance and corporate performance be balanced in the context of carbon neutrality? A quasi-natural experiment of central environmental inspections. Front. Energy Res. 10, 852286. doi:10.3389/fenrg.2022.852286

Fan, Z., Christensen, T., and Ma, L. (2022). Policy attention and the adoption of public sector innovation. Public Manag. Rev. doi:10.1080/14719037.2022.2050283

Feng, T., Lin, Z. G., Du, H. B., Qiu, Y. M., and Zuo, J. (2021). Does low-carbon pilot city program reduce carbon intensity? Evidence from Chinese cities. Res. Int. Bus. Finance 58, 101450. doi:10.1016/j.ribaf.2021.101450

Gong, M., He, W., and Zhang, N. (2021). Political promotion incentives and local employment. Econ. Anal. Policy 69, 492–502. doi:10.1016/j.eap.2021.01.004

He, L. Y., and Geng, M. M. (2020). Can Chinese central government inspection on environmental protection improve air quality? Atmosphere 11, 1025. doi:10.3390/atmos11101025

Jaffe, A. B., and Palmer, K. (1997). Environmental regulation and innovation: A panel data study. Rev. Econ. Stat. 79, 610–619. doi:10.1162/003465397557196

Ji, Z., Zhou, L., Wang, P., and Zhao, Y. (2014). Promotion of local officials and bank lending: Evidence from China’s city commercial banks. Finance Res. J. 1, 1–15. (in Chinese).

Jia, K., and Chen, S. (2019). Could campaignstyle enforcement improve environmental performance? Evidence from China’s central environmental protection inspection. J. Environ. Manage. 245, 282–290. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.05.114

Jiang, S. S., and Li, J. M. (2021). Do political promotion incentive and fiscal incentive of local governments matter for the marine environmental pollution? Evidence from China’s coastal areas. Mar. Policy 128, 104505. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104505

Jones, B. D., and Baumgartner, F. R. (2005). A model of choice for public policy. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 15, 325–351. doi:10.1093/jopart/mui018

Jones, B. D., Sulkin, T., and Larsen, H. A. (2003). Policy Punctuations in American political institutions. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 97, 151–169. doi:10.1017/S0003055403000583

Kheder, S. B., and Zugravu, N. (2012). Environmental regulation and French firms location abroad: An economic geography model in an international comparative study. Ecol. Econ. 77, 48–61. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2011.10.005

Koontz, T. M., and Thomas, C. W. (2006). What do we know and need to know about the environmental outcomes of collaborative management? Public Adm. Rev. 66, 111–121. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00671.x

Levinson, A. (2009). Technology, international trade, and pollution from US manufacturing. Am. Econ. Rev. 99, 2177–2192. doi:10.1257/aer.99.5.2177

Li, R., Zhou, Y., Bi, J., Liu, M., and Li, S. (2020). Does the central environmental inspection actually work? J. Environ. Manage. 253, 109602. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.109602

Lin, J., Long, C., and Yi, C. (2021). Has central environmental protection inspection improved air quality? Evidence from 291 Chinese cities. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 90, 106621. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2021.106621

MacDonald, G., and Marx, L. M. (2001). Adverse specialization. J. Polit. Econ. 109, 864–899. doi:10.1086/322084

Maskin, E., Qian, Y., and Xu, C. (2000). Incentives, information, and organizational form. Rev. Econ. Stud. 67, 359–378. doi:10.1111/1467-937X.00135

May, P. J., Workman, S., and Jones, B. D. (2008). Organizing attention: Responses of the bureaucracy to agenda disruption. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 18, 517–541. doi:10.1093/jopart/mun015

Millimet, D. L., and Roy, J. (2016). Empirical tests of the pollution haven hypothesis when environmental regulation is endogenous. J. Appl. Econ. Chichester. Engl. 31, 652–677. doi:10.1002/jae.2451

Millimet, D. L., Roy, S., and Sengupta, A. (2009). Environmental regulations and economic activity: Influence on market structure. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 1, 99–118. doi:10.1146/annurev.resource.050708.144100

Mortensen, P. B., and Green-Pedersen, C. (2014). Institutional effects of changes in political attention: Explaining organizational changes in the top bureaucracy. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 25, 165–189. doi:10.1093/jopart/muu030

Nowlin, M. C. (2011). Theories of the policy process: State of the research and emerging trends. Policy Stud. J. 39, 41–60. doi:10.1111/j.1541-0072.2010.00389_4.x

Ocasio, W. (2011). Attention to attention. Organ. Sci. (Linthicum). 22, 1286–1296. doi:10.1287/orsc.1100.0602

Ocasio, W., Laamanen, T., and Vaara, E. (2018). Communication and attention dynamics: An attention-based view of strategic change. Strateg. Manag. J. 39, 155–167. doi:10.1002/smj.2702

Ocasio, W. (1997). Towards an attention-based view of the firm. Strateg. Manage. J. 18, 187–206. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199707)18:1+<187::AID-SMJ936>3.0.CO;2-K

Pan, L., and Yao, S. (2021). Does central environmental protection inspection enhance firms’ environmental disclosure? Evidence from China. Growth Change 52, 1732–1760. doi:10.1111/grow.12517

Popp, D., and Newell, R. (2012). Where does energy R&D come from? Examining crowding out from energy R&D. Energy Econ. 34, 980–991. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2011.07.001

Preacher, K. J., and Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 40, 879–891. doi:10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

Sen, S. (2015). Corporate governance, environmental regulations, and technological change. Eur. Econ. Rev. 80, 36–61. doi:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2015.08.004

Shao, W., Yin, Y. F., Bai, X., and Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. (2021). Analysis of the upgrading effect of the industrial structure of environmental regulation: Evidence from 113 cities in China. Front. Environ. Sci. 9, 692478. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2021.692478

Shi, X., Bu, D., and Zhang, C. (2020). Official rotation and corporate innovation: Evidence from the governor rotation. China J. Account. Res. 13, 361–385. doi:10.1016/j.cjar.2020.07.004

Solarin, S. A., Al-Mulali, U., Musah, I., and Ozturk, I. (2017). Investigating the pollution haven hypothesis in Ghana: An empirical investigation. Energy 124, 706–719. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2017.02.089

Song, Y., Zhang, X., and Zhang, M. (2021). The influence of environmental regulation on industrial structure upgrading: Based on the strategic interaction behavior of environmental regulation among local governments. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 170, 120930. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120930

Wang, H., Fan, C., and Chen, S. (2021a). The impact of campaign-style enforcement on corporate environmental action : Evidence from China’s central environmental protection inspection. J. Clean. Prod. 290, 125881. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.125881

Wang, H., Yang, G., Ouyang, X., and Qin, J. (2021b). Does central environmental inspection improves enterprise total factor productivity? The mediating effect of management efficiency and technological innovation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 21950–21963. doi:10.1007/s11356-020-12241-6

Wang, J., Dong, H., and Xiao, R. (2022). Central environmental inspection and corporate environmental investment: Evidence from Chinese listed companies. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29, 56419–56429. doi:10.1007/s11356-022-19538-8

Wang, L., Wang, Z., and Ma, Y. (2022). Heterogeneous environmental regulation and industrial structure upgrading: Evidence from China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29, 13369–13385. doi:10.1007/s11356-021-16591-7

Wang, M. (2021). Environmental governance as a new runway of promotion tournaments: Campaignstyle governance and policy implementation in China’s environmental laws. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 34924–34936. doi:10.1007/s11356-021-13100-8

Wang, S. L., Chen, F. W., Liao, B., and Zhang, C. (2020). Foreign trade, FDI and the upgrading of regional industrial structure in China: Based on spatial econometric model. Sustainability 12, 815. doi:10.3390/su12030815

Wang, W. J., and Li, Y. X. Y. (2022). Can green finance promote the optimization and upgrading of industrial structures? Based on the intermediary perspective of technological progress. Front. Environ. Sci. 10, 919950. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2022.919950

Weiner, B. (1985). An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychol. Rev. 92, 548–573. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.92.4.548

Wu, L., Sun, L., Qi, P., Ren, X., and Sun, X. (2021). Energy endowment, industrial structure upgrading, and CO2 emissions in China: Revisiting resource curse in the context of carbon emissions. Resour. Policy 74, 102329. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2021.102329

Xiang, C., and van Gevelt, T. (2020). Central inspection teams and the enforcement of environmental regulations in China. Environ. Sci. Policy 112, 431–439. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2020.06.018

Yang, C. H., Tseng, Y. H., and Chen, C. P. (2012). Environmental regulations, induced R&D, and productivity: Evidence from taiwan’s manufacturing industries. Resour. Energy Econ. 34, 514–532. doi:10.1016/j.reseneeco.2012.05.001

Zhang, D., and Chen, L. (2018). Environmental regulation, upgrading of industrial structure and economic fluctuation: An empirical study of dynamic panel threshold. J. Environ. Econ. 4, 92–109. doi:10.20944/preprints201811.0319.v1

Zhang, Z., Peng, X., Yang, L., and Lee, S. (2022). How does Chinese central environmental inspection affect corporate green innovation? The moderating effect of bargaining intentions. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29, 42955–42972. doi:10.1007/s11356-022-18755-5

Zhao, J., Jiang, Q., Dong, X., and Dong, K. (2020). Would environmental regulation improve the greenhouse gas benefits of natural gas use? A Chinese case study. Energy Econ. 87, 104712. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2020.104712

Zhao, X., Liu, C., and Yang, M. (2018). The effects of environmental regulation on China’s total factor productivity: An empirical study of carbon-intensive industries. J. Clean. Prod. 179, 325–334. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.01.100

Zheng, J., Shao, X., Liu, W., Kong, J., and Zuo, G. (2021). The impact of the pilot program on industrial structure upgrading in low-carbon cities. J. Clean. Prod. 290, 125868. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.125868

Zheng, Q., Wan, L., Wang, S., Wang, C., and Fang, W. (2021). Does ecological compensation have A spillover effect on industrial structure upgrading? Evidence from China based on A multistage dynamic did approach. J. Environ. Manage. 294, 112934. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.112934

Keywords: industrial structure upgrading, Central environmental inspection, environmental attention, officials’ promotion motivation, difference-in-differences approach

Citation: Wang B, Ma C and Wu J (2022) Does central environmental inspection promote the industrial structure upgrading in China? An attention-based view. Front. Environ. Sci. 10:1030653. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.1030653

Received: 29 August 2022; Accepted: 28 September 2022;

Published: 11 October 2022.

Edited by:

Kangyin Dong, University of International Business and Economics, ChinaReviewed by:

Ghaffar Ali, Shenzhen University, ChinaMuhammad Ziaul Hoque, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Agricultural University, Bangladesh

Copyright © 2022 Wang, Ma and Wu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chunhao Ma, bWFjaHVuaG9vQDE2My5jb20=

Biying Wang

Biying Wang Chunhao Ma

Chunhao Ma Jianzu Wu

Jianzu Wu