- 1School of Economics and Business Administration, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China

- 2School of Electrical Engineering, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China

- 3College of Physical Education, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China

- 4School of Management, Xiamen University, Xiamen, Fujian, China

Combining the perspectives of upper echelon theory and institutional theory, we investigate how top managers’ sport experience exploits corporate environmental proactivity in China and embed this question into state ownership. With the sample of Chinese listing enterprises from 2008 to 2018, we find that both sport experience and state ownership positively promote corporate environmental proactivity, while state ownership crowds out the promotion of top managers’ sport experience. Further analyses show that position and financial experience of top manager as well as corporate investing efficiency and location matter in these processes. Thus, we extend the understanding of how top managers’ sport experience and state ownership interact and influence corporate environmental proactivity. We, therefore, provide new instruments to promote corporate environmental proactivity and, respectively, extend upper echelon theory from the perspective of top managers’ sport experience as well as institutional theory from the perspective of state ownership.

1 Introduction

China, the biggest emerging economy, is facing a striking environmental challenge (Jiang et al., 2020; Wang & Jiang, 2021), despite tremendous effort toward fighting the same (Sun et al., 2019). Pro-environment enterprises have been appealing for a long time (Li et al., 2020; Ren et al., 2022), which is evidently positive for the society, and is also believed to bring enterprises both better performance and legitimacy (De Mendonca & Zhou, 2019; Pan et al., 2019; Li et al., 2021). Constructing corporate environmental proactivity has become an important issue, and efforts have been made to search for the drivers of environmental proactivity, including factors about society, economy, institutions, corporations, and individuals (Hörisch et al., 2017; Alzubaidi et al., 2021; Wang & Jiang, 2021).

The characteristics and prior experiences of top managers (TMs) are argued to be a set of important drivers of environmental proactivity (Cho et al., 2019; Pryor et al., 2019). According to the upper echelon theory (UET), how enterprises operate critically depends on TMs, whose decisions are influenced by their psychological traits (Arena et al., 2018; Liao & Long, 2018; Pryor et al., 2019; Shahab et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2019). Furthermore, an individual’s psychological traits are majorly shaped by their prior experiences (Allen et al., 2013; Cho et al., 2019; Marchini et al., 2022), such as birth (Ren et al., 2021), education (Hörisch et al., 2017; Cho et al., 2019), and employment (Wang et al., 2022).

However, among the efforts to search TMs’ characteristics influencing environmental proactivity (Arena et al., 2018; Liao & Long, 2018; Pryor et al., 2019; Ren et al., 2021), sport experience, the fast-growing experience during the dramatic aging era in China, is somehow ignored. Sport experiences tend to spread fast following the aging trend, during which the growing scale of the elderly tends to exercise more to maintain their health. Meanwhile, as the Chinese government has put forward the policy “Healthy China 2030,” an increasing number of sporting exercises will be encouraged, especially for corporate upper echelons who treasure their health. During the spreading trend of sport, sport experience itself, which shapes a tough, resilient, and hard-working mentality, is likely to impact pro-sustainability and pro-environment proactivity. Thus, the influence of TMs’ sport experience on enterprises’ environmental proactivity deserves more attention.

Considering the environment has been strikingly degraded in the developing economies, we test our question, how does TMs’ sport experience exploit corporate environmental proactivity, in the Chinese context. In emerging economies such as China, a large proportion of the economy consists of and is impacted by the state-owned enterprises (SOEs) (Liang & Renneboog, 2017; Hu et al., 2018), making it important to test how state ownership influences corporate environmental proactivity (Wang & Jiang, 2021). However, whether state ownership promotes or suppresses environmental proactivity remains debatable (Pan et al., 2019). Thus, we further put our question into the conditions of state ownership.

Considering our research questions, namely, how TMs’ sport experience exploits corporate environmental proactivity and how state ownership matters during this process, we collected Chinese listing enterprises from 2008 to 2018 as a sample and tested the observations with the fixed-effect panel regression. In doing so, we find that both sport experience and state ownership positively promote corporate environmental proactivity, and state ownership in enterprises moderates how sport experience influences corporate environmental proactivity: first, sport experience positively promotes environmental proactivity. Second, state ownership positively promotes environmental proactivity. Third, state ownership negatively moderates the process that sport experience positively promotes environmental proactivity; namely, sport experience in state-owned enterprises suppresses environmental proactivity, while sport experience in non-state-owned enterprises promotes environmental proactivity.

Furthermore, we apply several robustness and heterogeneity tests. The major conclusions remain robust, and several interesting findings emerge: first, top managers’ positions matter, and sport experience of director board chairman (DBC) seems less influential than that of CEO. Second, top managers’ financial experience matters too, and top managers with financial experience seems less impacted by sport experience and state ownership. Third, investment efficiency matters: sport experience and state ownership promote environmental proactivity and no crowd-outs are found in overinvesting firms, while no promotion but only crowd-outs are found in under-investing firms. Finally, no promotion but only crowd-outs are found in east region firms.

With the aforementioned studies and findings, we provide new instruments to promote corporate environmental proactivity and new understanding about sport experience and state ownership:

First, we provide new instruments to promote corporate environmental proactivity. With upper echelon theory, we analyze how top managers’ trait (i.e., sport experience in this study) influences corporate environmental proactivity. We further put this relationship in the context of China and test the moderating effect of state ownership. We also test several heterogeneities, improving the understanding of the mechanism and conditions. As few literature studies are found about sport experience influencing environmental proactivity, we thus improve the interpretation of the ex ante factor of environmental proactivity, its mechanisms, and marginal conditions.

Second, we contribute to upper echelon theory, extending the understanding of sporting experience of top managers in the context of China. Though numerous research studies delve into how top managers’ personality and cognition influence environmental proactivity (Pryor et al., 2019), few literature studies are found about how top managers’ sport experience influences corporate operation, not to mention environmental proactivity or its relationship with state ownership. Thus, we fill this gap and provide new benefit–cost analysis about hiring sporting-experienced top managers, especially for the SOEs with environmental goals.

Finally, we contribute to institutional theory, verifying institutions as important factors in pro-environment operations (Sun et al., 2019). We provide new pieces of evidence examining how state ownership influences pro-environment traits and their consequences, with the regulatory focus theory. We focus on the interaction between sport experience and state ownership, and how this interaction influences corporate environmental proactivity. Existing literature often stands on the pro-side of state ownership, interpreting and testing from the resource-based view, arguing state ownership provides abundant resources and political protection which facilitates environmental proactivity (Gao & Hafsi, 2015; Liao et al., 2019; Li et al., 2021; Wang & Jiang, 2021). We supplement supporting evidence to the pro-side, but we also remind of a marginal while pessimistic fact that state ownership crowds out how pro-environment traits construct environmental practices.

2 Theoretical foundation and hypothesis development

2.1 Theoretical foundation

2.1.1 Upper echelon theory

Ever since upper echelon theory (UET) was sparked by Hambrick and Mason (1984), it has been widely applied in management research studies (Bromiley & Rau, 2016), such as Petrenko et al. (2016), Ou et al. (2018), and Zhang et al. (2021). UET has become a core theory in the field about how firms decide and receive significant empirical support (Pryor et al., 2019).

UET focuses on tracing corporate decisions based on the characteristics of upper echelons, mainly about how corporate decisions and performances are influenced by the social, behavioral, and cognitive factors of CEOs, TMTs, and the CEO–TMT interfaces (Bromiley & Rau, 2016). UET explains how TMs’ deciding process is affected by their traits, and how their decisions embody corporate operations (Pryor et al., 2019).

UET believes corporate decisions largely depend on upper echelons’ behavioral traits and personality (Arena et al., 2018). Considering environmental proactivity is a kind of corporate strategy and orientation, TMs are claimed to be at the pinnacle (Cho et al., 2019).

2.1.2 Institutional theory

Institutional theory frames how institutions and organizations interact (Zhou et al., 2017). It argues that firms are fundamentally influenced by their embeddedness in certain institutional environments, and firms adjust their strategies and operations according to the institutional norms (Wang & Jiang, 2021). This influence of institutions comes not only from the formal norms such as laws and regulations, but also the informal norms including beliefs and values (Zhou et al., 2017; Wang & Jiang, 2021). Institutional theory also emphasizes the necessary supplement of government intervention to the market (Xia et al., 2021), especially where there exists a large positive externality such as environment protection.

In the emerging economies, governments are the most salient institutions and profoundly shape the market competition (Zhou et al., 2017). The government not only constructs rules but also enforces the rules, and meanwhile controls and allocates various critical resources (Gao & Hafsi, 2015). Organizations must acquire legitimacy by obeying the dominant stakeholders and institutions (Liu et al., 2020), namely, the government. Within this context, state ownership provides the government a direct power to control firms, which delivers the governmental mandates (Yang et al., 2019) and also provides firms with resources (Pan et al., 2019).

2.2 Hypothesis development

2.2.1 Upper echelon theory, sport experience, and environmental proactivity

Sport represents a structural type of physical activity that involves physical exertion, elements of competition, complex physical skills, and clear rules and patterns (Allen et al., 2021). Sport is an important social and cultural phenomenon for human development and is considered a critical tool in active aging, to maintain both physical fitness and mental happiness (Cannella et al., 2021).

Sport participation has a psychosocial impact on individuals (Laborde et al., 2020; Cannella et al., 2021) and even shapes their personality (Piepiora et al., 2022). People who engage in sport and exercise activities have different personality traits than those who do not (Eagleton et al., 2007), and this influence is more profound in longer and deeper sport participation (Piepiora et al., 2022). For example, athletes are often found to have more vigor, less fatigue (Eagleton et al., 2007), and more extraversion (Allen et al., 2021; Piepiora, 2021a). Moreover, high-risk sports participants, such as mountaineers, are often found to have more extraversion, conscientiousness, and emotional stability (Crust, 2020). Another instance is the certain trait constructed within the competitive context of sports, such as risk-taking (Boheim & Lackner, 2015), which is always found in sports where rewards are directly linked to competitiveness and performance (Böheim et al., 2022).

The personality-shaping effect of sport comes from dealing with difficulty in a stressful situation in sport (Piepiora, 2021b). From the gene-environment perspective, a specific gene which is believed to construct a certain personality (e.g., 5-HTT) is found to be associated with positive psychological development in the context of sport (Golby & Sheard, 2006). This personality-shaping effect of sport might be caused by the competence of rivalries (Piepiora, 2021a), and the pressures on the performance might strengthen specific personality (Piepiora et al., 2022). For example, this personality-shaping effect of sport becomes stronger given success in sport (Steca et al., 2018; Allen et al., 2021), which often accompanies self-achievement from fans and media (Allen & Desille, 2017).

Sport participation is believed to shape more positive personality traits (Piepiora et al., 2022), such as openness characterized by divergent thinking (Piepiora et al., 2021). Among these positive impacts, sports, especially team sports, constructs a strong preference for social stimulation (Allen et al., 2021). Sport participation exposes children and adolescents to adult concepts (e.g., organization, discipline, fairness, and teamwork), thus facilitating mature developmental and personality traits (Allen et al., 2013). Team sports participants are found to have more extraversion (Eagleton et al., 2007).

Following UET, top managers’ sport experiences certainly influence corporate operations, by constructing top managers’ personality traits (Piepiora et al., 2022), such as maturity (Allen et al., 2021), extraversion (Eagleton et al., 2007), openness (Piepiora et al., 2021), and preference for social stimulation (Allen et al., 2021). Combined with the stakeholder theory (Provasnek et al., 2017; Yu et al., 2017), it is indeed the pressure from the public and competitors which drives environmental proactivity (Liao & Long, 2018). Thus, TMs with sport experience tend to orient more environmentally, from the aspects of competing pressure and environmental legitimacy.

In the developing economies such as China, the striking environmental degradation pushes the public under the pressure of environmental protection against the excessive consumption of resources (Liao & Long, 2018). The pro-environment development has been placed among the highest level of government agenda (see the fourth guidance from the State Council, the highest administrative power in China). TMs’ ambition positively promotes enterprises’ environmental processes (Liao & Long, 2018), as environmental proactivity brings them legitimacy and reputation. In this manner, sport experience shapes a competitive and aspiring trait, thus positively leading to environmental proactivity.

Moreover, environmental proactivity is a new and risky target in addition to the traditional one to maximize shareholders’ benefit (Arena et al., 2018), thus the openness (Stroessner et al., 2015), risk-taking (Spanjol et al., 2011), and self-confidence (Arena et al., 2018), which are often found in sport participants, also drive the environmental proactivity.

Thus, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 1. Sport experiences of top managers promote environmental proactivity.

2.2.2 Institutional theory, state ownership, and environmental proactivity

State ownership is prevalent in China, and is believed to be more interventionist in developing countries such as China than in developed countries (Gao & Hafsi, 2015). State ownership exchanges controlling power for political privileges (Wang & Jiang, 2021), providing SOEs with more resources, institutional protection, and competing advantages (Liao et al., 2019; Li et al., 2021). Both political control and privileges lead SOEs toward more environmental proactivity (Wang & Jiang, 2021).

On the one hand, according to the institutional theory and stakeholder theory (Pan et al., 2019; Jiang et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021), political control of state ownership pushes SOEs to be environmentally proactive. The government control inherent in state ownership pushes SOEs to achieve public goals (Liu et al., 2020). Nowadays, in China, where environmental degradation is striking and the government is emphasizing on environmental protection, green development has become one of the most critical tasks (Pan et al., 2019; Wang & Jiang, 2021). Thus, SOEs tend to be more environmentally proactive, with more public duty.

On the other hand, according to the institutional theory and resource-based theory (Gao & Hafsi, 2015; Li et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021), political privileges of state ownership help SOEs to be environmentally proactive. The government usually adjusts economy and grants protection by national strategic planning, antitrust policies, funds, and banking regulations, which often prefers SOEs according to institutional theory (Zhou et al., 2017). Combining with the resource-based theory, the stable external environment is crucial to environmental proactivity, as availability of resources is a critical constraint to pursuing environmental sustainability (Arena et al., 2018). Namely, slack resources are found to positively moderate how TMs’ ambition promotes enterprises’ environmental processes (Liao & Long, 2018). Thus, the abundant resources and stable context provided by state ownership are helpful to construct environmental proactivity and achieve environmental practices (Gao & Hafsi, 2015; Pan et al., 2019; Wang & Jiang, 2021). Thus, SOEs tend to be more environmentally proactive, with more public resources.

Thus, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 2. State ownership promotes environmental proactivity.

2.2.3 Moderation of state ownership

How does state ownership moderate the relationship between TMs’ sport experience and corporate environmental proactivity? Would it be a multiplying effect that TMs’ sport experience promotes corporate environmental proactivity more in SOEs or a crowding-out effect that TMs’ sport experience promotes corporate environmental proactivity less in SOEs?

We argue from the perspective of regulatory focus theory that TMs with sport experience in SOEs focus less on regulation, thus they orient less toward the environment. Namely, state ownership crowds out the promotion of TMs’ sport experience on corporate environmental proactivity.

Regulatory focus theory divides focus on regulation into two parts (Liao & Long, 2018): one is the promotion focus, which prompts individual to chase positive goals such as rewards and reputation; the other is the prevention focus, which merely seeks to avoid punishment.

On the one hand, TMs with sport experience in SOEs focus less on promotion. For individuals with promotion focus tend to pursue achievements and awards (Adams et al., 2011), legitimacy theory suggests that environmental proactivity seems an intuitive instrument to gain legitimacy and reputation (Calza et al., 2016; Li et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021). However, SOEs are often multi-target (Li et al., 2021); rewards and reputation can be gained from other achievements (such as common prosperity and COVID-19 prevention), and TMs with promotion focus in SOEs are often distracted (Li et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2019). Via state ownership, governments can affect SOEs’ operations and TMs’ appointments (Zhou et al., 2017) and mandate SOEs for non-economic goals such as employment (Gao & Hafsi, 2015). Thus, environmental proactivity in SOEs is usually less market-driven (Hu et al., 2018), and even contrasts with their economic goals (Li et al., 2018).

On the other hand, TMs with sport experience in SOEs focus less on prevention. Stability, safety, and responsibility are valued more by the TMs with prevention focus, especially within the scope of their own duties and responsibilities (Liao & Long, 2018). However, SOEs are often governmentally connected and thus are less likely to be investigated or punished (Wang & Jiang, 2021). Another mechanism is that SOEs have more resources and are less concerned about the consequences of being less pro-environment. Thus, there is less pressure and motivation for TMs with sport experience in SOEs to orient environmentally and avoid environmental investigation and regulation, while non-SOEs must comply with the legal and social requirements of the environment (Calza et al., 2016).

Thus, we draw the following hypothesis, which further consists of two sub-hypotheses:

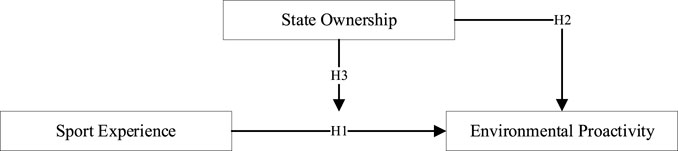

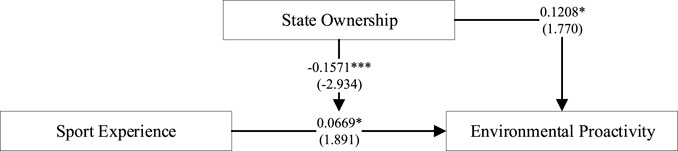

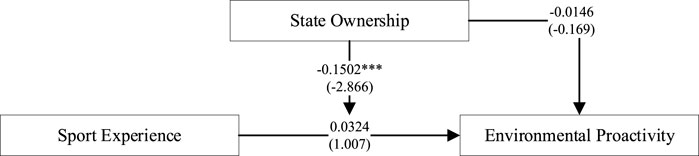

Hypothesis 3. State ownership moderates the promotion of top managers’ sport experiences on environmental proactivity.Thus, combining the abovementioned hypotheses, our study framework is shown as Figure 1.

3 Methodology

3.1 Models and variables

To examine how sport experience influences environmental proactivity in SOEs, following several relating studies (Hu et al., 2018; Flammer et al., 2019; Ren et al., 2021), we apply panel regression with three-way fixed effects and standard errors as follows:

where

We measured the environmental proactivity (denoted as

We measured the sport experience (denoted as

We measured state ownership (denoted as

We controlled several dimension variables, mainly including accounting factors (Marchini et al., 2022), financial market factors, and governance factors (Husted & Sousa-Filho, 2019; Marchini et al., 2022).

First, the accounting factors consider 1) the firm size (

Second, the financial market factors consider 1) the book-to-market ratio (

Third, the governance factors consider 1) meeting of the director board (

3.2 Data and sample

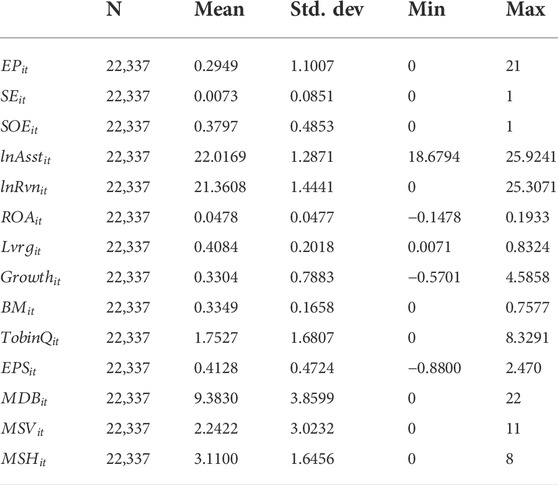

Primary data were obtained from the CSMAR database, which is a resource for several relevant studies (Zhou et al., 2017; Jiang et al., 2020). The data used in this study are from A-share corporations listed on the CSHSE and CSZSE from 2008 to 2018. After filling or removing missing data and winsorization with 1% at both tails, a sample of 22,337 corporation-year observations was obtained. The descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1.

The sample started in 2008 for three main reasons. First, China’s share structure reform around 2006 significantly changed the reporting of some accounting data. Thus, some financial indicators might have been incomparable to those prior to the reform (Zhou et al., 2018). Second, Chinese property law reforms around 2007 also significantly influenced corporate operation (Kong et al., 2019). Finally, the 2008 global crisis was another considerable event that caused structural changes.

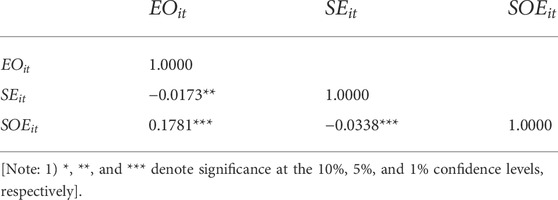

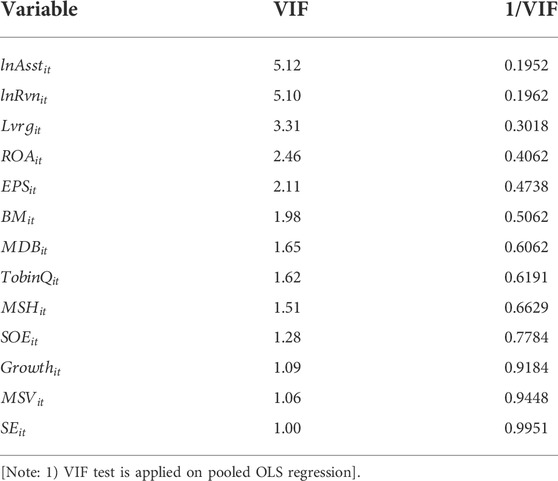

The correlation matrix of main variables is shown in Table 2, where correlations are less than 0.2; the variance inflation factors (VIFs) of main variables are shown in Table 3, where the VIFs of the main variables are lower than 2. These results indicate slight concern about multicollinearity but also the suitability of applying fixed-effect panel regression (Hu et al., 2018; Husted & Sousa-Fiho, 2019).

4 Empirical analysis

4.1 Results of baseline models

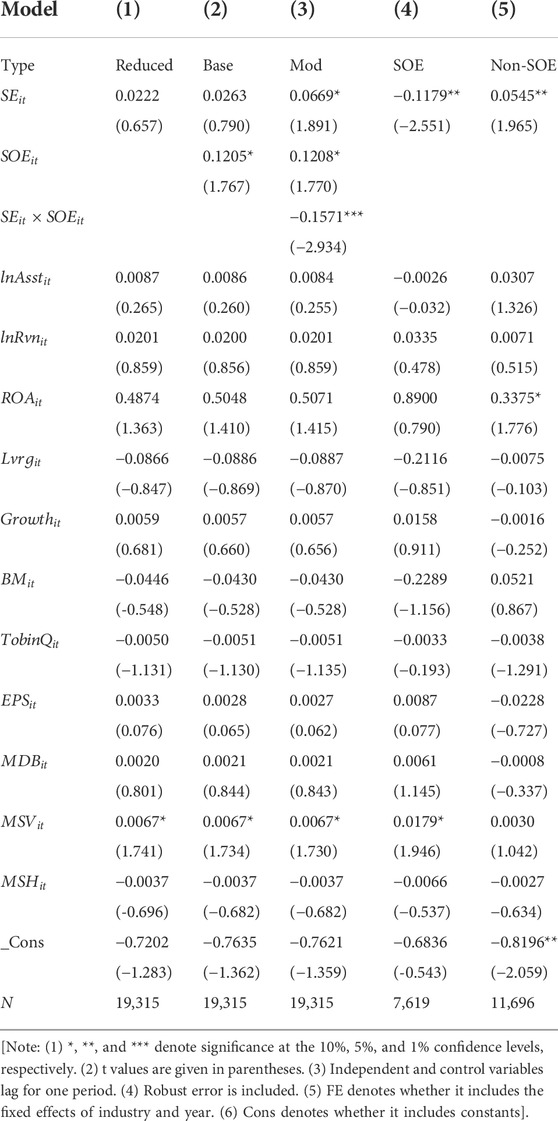

Table 4 presents the results of baseline models. Model (1) shows the results excluding state ownership, and model (2) shows the results including state ownership. Model (3) introduces the moderating effect of state ownership on sport experience, and the major results are listed in Figure 2. Models (4) and (5) show the results of subsamples.

According to the results of model (3), we find that:

First, sport experience leads to environmental proactivity, as

Second, state ownership promotes environmental proactivity, as

Third, state ownership hinders the promotion of sport experience on environmental proactivity, as

Generally, taking the results of models (1–3) together, we find that state ownership is a factor more robust and influential than sport experience. Thus, we partly support Sun et al. (2019) who argue institutions as important factors influencing green production. This may be because TMs with sport experience are fewer than SOEs, and state ownership is a more prevalent and influential factor in China (Zhou et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018) than TMs and their sport experiences.

Nevertheless, according to model (3), we conclude that TMs’ sport experience is still a considerable driver of environmental proactivity, though being crowded out by state ownership. This may be because multiple goals in addition to environmental protection and mandatory hierarchy of state ownership limit the motivation and initiation of TMs, thus TMs’ sport experience promoting environmental proactivity is crowded out by state ownership. However, due to the considerable strength of UET, which still influences corporate operation slightly but essentially, TMs’ sport experience promotes environmental proactivity even when given a strong government control.

4.2 Robustness tests

4.2.1 Endogenous problem

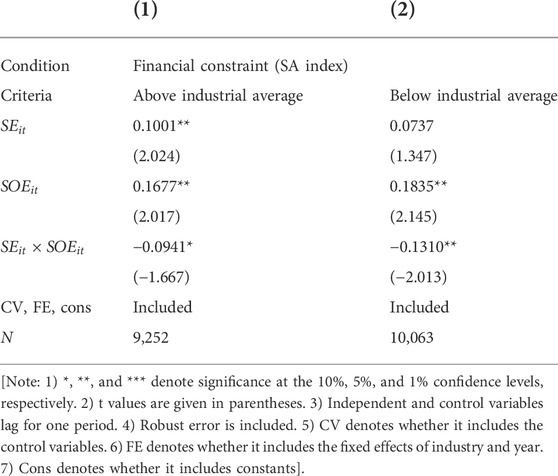

Following the resource-based theory, an intuitive guess is that more constrained corporations tend to have less environmental proactivity, causing an endogenous problem of omitting variables. Another concern is that SOEs tend to be more abundant and less financially constrained, causing an endogenous problem of omitting causality. Thus, we introduce financial constraint as a potential influencing factor to our questions.

As for financial constraints, we measure with the SA index. The other well-known measures, KZ index and WW index, are not applied, as serious concerns and extreme cautions about endogenous accounting factors are raised by existing research studies (Hadlock & Pierce, 2010; Farre-Mensa & Ljungqvist, 2016). The SA index is argued to be a more adaptable measure of financial constraints applicable in various circumstances (Hadlock & Pierce, 2010) and is calculated as follows:

We divide observations into two subsamples according to the Chinese studies (Yu et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019), the one is financially constrained whose SA index is above the industry average; while the other is not financially constrained whose SA index is below the industry average.

The results are shown in Table 5, and the major conclusions remain robust: first, according to model (1), sport experience promotes environmental proactivity in financially constrained firms, and H1 is supported. Second, according to models (1) and (2), state ownership drives environmental proactivity, and H2 is supported. Third, according to models (1) and (2), state ownership negatively moderates the relationship between sport experience and environmental proactivity, and H3 is supported. The slight change might be because the resource abundance moderates how sport experience fosters environmental proactivity: according to resource-based theory (Arena et al., 2018; Wang & Jiang, 2021), financial constraints might suppress environmental proactivity and force firms to focus on surviving routine operation; thus, given this context, TMs with sport experience, who are more vigorous, have less fatigue (Eagleton et al., 2007), and more extraversion (Allen et al., 2021; Piepiora, 2021b), tend to act more influential in the pro-environment decision and process.

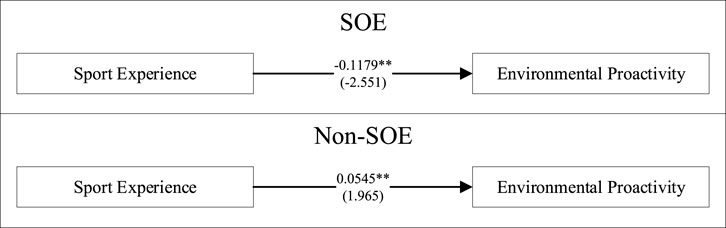

4.2.2 Alternative method: Subsample regression

Following Li et al. (2021), we run a subsample regression, separating our sample into SOEs and non-SOEs. The results are shown as models (4) and (5) in Table 4, and the major conclusions are drawn in Figure 3. Sport experience suppresses environmental proactivity in SOEs (

5 Further analyses: Potential heterogeneity

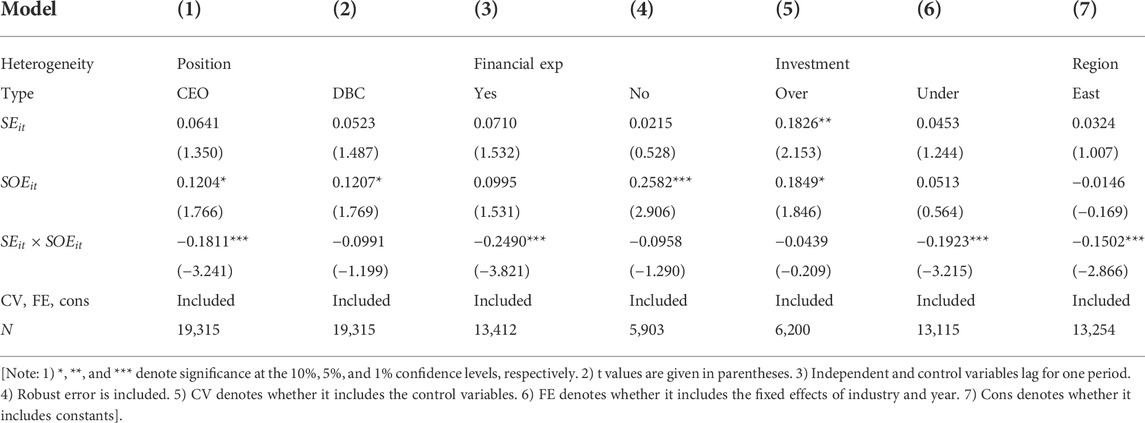

To further analyze the question, whether TMs’ sport experience influences corporate environmental proactivity in SOEs, we test several potential heterogeneous conditions, including TMs’ positions, TMs’ prior experiences represented by financial one, corporate investing efficiency, and corporate locating region. The main results are shown in Table 6. Though main conclusions are found in several models, heterogeneities are also found.

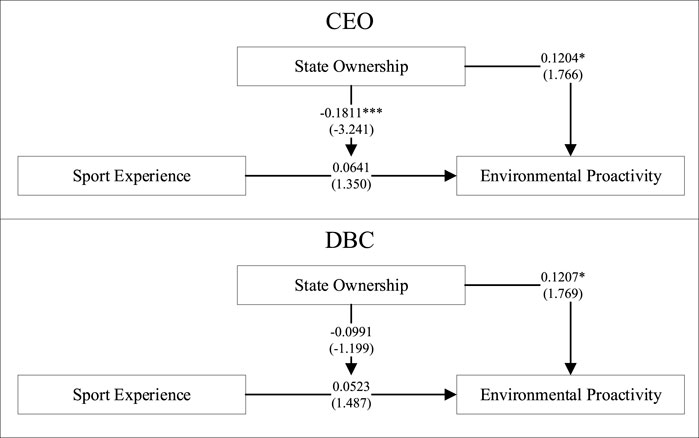

5.1 Heterogeneity of positions

To test whether TM’s position influences the relationship between sport experience and environmental proactivity, we divided it into the chief executive officer (CEO) and director board chairman (DBC). The rationality is that the CEO manages the routine operation and is often hired by the firm, while DBC owns the firm and is ultimately responsible for the firm.

The results are shown in Table 6 and Figure 4. Model (1) shows the results of CEO’s sport experience, and model (2) shows those of DBC. The results of state ownership are found to be robust in both subsamples, the coefficients in models (1) and (2) are, respectively, estimated as 0.1204 and 0.1207 both at a 10% confidence level, and H2 is supported. However, the crowd-out effect of SOE is found to be more profound and robust in the subsample considering CEO’s sport experience: according to model (2), the coefficient of SOE moderating between CEO’s sport experience and environmental proactivity is estimated as −0.1811 at 1% confidence level. These results indicate that state ownership indeed negatively moderates the relationship between CEO’s sport experience and corporate environmental proactivity, and partially support H3.

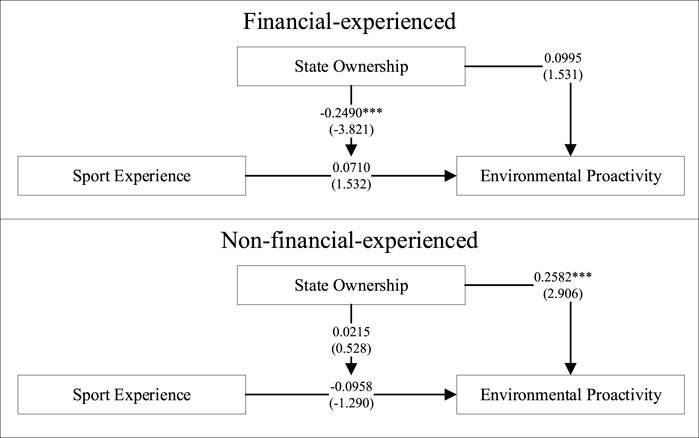

5.2 Heterogeneity of the financial experience

Following upper echelon theory (Hambrick & Mason, 1984; Wang R. et al., 2020; Cao & Zhang, 2021), we further test whether and how CEO experiences influence the relationships. We take CEO’s financial experience as a dimension and divide observations into two subsamples according to whether CEO has a financial experience.

The results are shown in Table 6 and Figure 5. Models (3) shows the results of CEO with financial experience, and model (4) shows those without financial experience. State ownership promotes environmental proactivity in firms with non-financial-experienced TMs; the coefficient in model (4) is estimated as 0.2582 at 1% confidence level, partially supporting H2. The negative moderating effect of SOE is found more profound and robust in the subsample with financial experience. According to model (3), the coefficient of SOE moderating between TMs’ sport experience and environmental proactivity is estimated as −0.2490 at 1% confidence level. These results indicate that state ownership indeed negatively moderates the relationship between TMs’ sport experience and corporate environmental proactivity, and partially support H3.

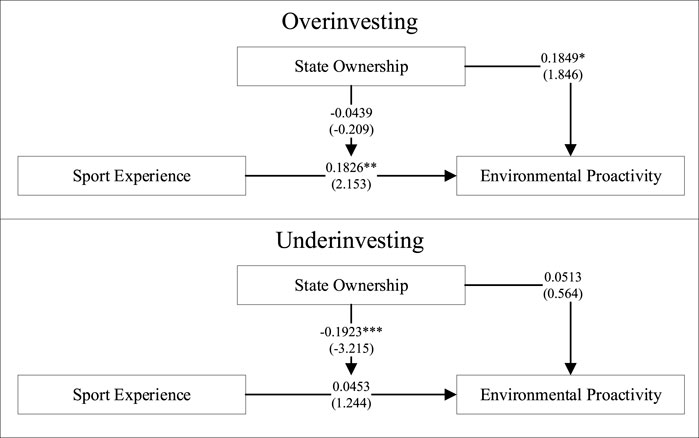

5.3 Heterogeneity of investing efficiency

Considering inefficient investing might stress TMs and therefore hinder environmental proactivity according to resource-based theory, we thus introduce investing efficiency as a potential influencing factor.

We introduce the industrial standard measure of investing efficiency following Richardson (2006), which has been widely applied since being sparked (Chen et al., 2011; Wang H. et al., 2020; Stephie Tsai et al., 2021). The thought behind this was to measure investing efficiency by the deviations in investing expenditure from the target level (Wang H. et al., 2020). After estimating investment with the following industry-year regression, investing efficiency is measured by the residual (

where

The results are shown in Table 6 and Figure 6. Model (5) shows the results of overinvesting firms, and model (6) shows underinvesting ones. TMs’ sport experience is found to be more profound in overinvesting firms, and the coefficient in model (5) is estimated as 0.1826 at 5% confidence level, partially supporting H1. State ownership is found to be more profound in overinvesting firms, and the coefficient in model (5) is estimated as 0.1849 at 10% confidence level, partially supporting H2. The negative moderating effect of SOE is found to be more profound and robust in the subsample of underinvesting firms, and the coefficient of SOE moderating between CEO’s sport experience and environmental proactivity in model (6) is estimated as −0.1923 at 1% confidence level, partially supporting H3.

These results indicate that investment, largely depending on resources and risk-taking, may be one important driver of environmental proactivity. In the overinvesting firms, which may have abundant resources and risk-taking, both TMs’ sport experience and state ownership promote environmental proactivity, and no crowd-out effect is found. However, in the underinvesting firms, which may lack resources or risk-taking, neither TMs’ sport experience nor state ownership influences environmental proactivity, while the crowd-out effect is found.

5.4 Heterogeneity of locating region

Regions somehow reflect the context factors (e.g., economic development, institutions, policies, and demanding market), which influence environmental proactivity. Thus, we take the corporate locating region into consideration.

For this purpose, we define corporate regions using its registering province, following the four-region division provided by the National Bureau of Statistics of China (http://www.stats.gov.cn/ztjc/zthd/sjtjr/dejtjkfr/tjkp/201106/t20110613_71947.htm), and extract the firms in the east as a subsample.

The results are shown in Table 6 and Figure 7. Model (7) shows the results of east region firms. Only crowd-out effect is found, while no other relationship is found. The coefficient of moderator is estimated as −0.1502 at 1% confidence level, partly supporting H3.

This finding may be due to the development of east China, where the market and corporate governance are more developed, and governments are more serving. Because the market and corporate governance in east China are more developed, sport experience, one of TMs’ bias, can be eliminated by the stakeholders (such as shareholders, directors, and supervisors). Because the government is more serving, tending to intervene less in corporate operation via mandatory policies, SOEs in the east region are not mandated to prioritize the environment over the market. Thus, firms in east China operate in a more rational way and are being less considerably influenced by TMs’ traits or state ownership.

6 Conclusion and discussion

Given China, the biggest developing country with a large government, facing both aging problem and environmental issues, facilitating both mental health and environmental health is a critical question. With upper echelon theory and regulatory focus theory, we interpret how top managers’ sport experience influence corporate environmental proactivity considering state ownership. We test the questions with the sample of Chinese listing enterprises from 2008 to 2018, with the fixed-effect panel regression.

For this purpose, we find: first, sport experience positively promotes environmental proactivity, supporting existing literature (Arena et al., 2018; Liao & Long, 2018; Pryor et al., 2019). Second, state ownership positively promotes environmental proactivity, supporting previous studies (Calza et al., 2016; Wang & Jiang, 2021). Third, state ownership negatively moderates the process that sport experience positively promotes environmental proactivity, extending related research (Arena et al., 2018) to a specific contingency. Furthermore, we apply several robustness tests and heterogeneity tests, main conclusions remain robust and marginal conditions (such as top managers’ positions, financial experience, and investment efficiency) are found.

With the aforementioned studies and findings, we provide new instruments to promote corporate environmental proactivity and new perspectives about sport experience and state ownership: first, we provide new instruments to promote corporate environmental proactivity. Second, we contribute to the understanding of sport-experienced top managers in the context of China, following the upper echelon theory. Finally, we provide new evidences examining how state ownership influences pro-environment traits and their consequences, with the institutional theory and regulatory focus theory.

Meanwhile, our research and findings contribute to the practice. On the one hand, we find that state ownership promotes corporate environmental proactivity, verifying the effectiveness of governmental intervention in protecting the environment. On the other hand, we suggest top managers’ sport experience as a driver of environmental proactivity, thus to hire a sport-experienced top manager or to encourage top manager engaging sports can be two instruments for achieving environmental goals. Moreover, we further suggest several marginal conditions (such as top managers’ position and corporate investing efficiency), which can be used contingently by the stakeholders: shareholders are able to benefit from sport-experienced top managers in the overinvesting SOEs, while policymakers chasing better environmental goals should pay more attention to SOEs with sport-experienced CEO, sport-experienced TMs with financial experience, underinvestment, and east location.

We must admit several drawbacks in our research which deserve more studies. First, we test our hypotheses with public listing enterprises, which are better governed, but we cannot provide evidence based on the small or medium enterprises; thus, future research could focus on the private enterprises. Second, we test our hypotheses in China, so we cannot guarantee the external validity of our entire conclusions in other counties; thus, future research could be cross-country.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. These data can be found here: CSMAR (https://www.gtarsc.com/).

Author contributions

JZ conducted the major study and writing. PP collected and cleaned data. JP supervised and funded the study. YF revised some analysis and writing.

Funding

This study was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Project No. 2020CDJSK02PT04), the Chongqing Natural Science Foundation (Project No. cstc2020jcyj-msxmX0817), the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province in China (2020J01032), and the Natural Science Foundation of Hainan Province in China (Youth Fund Project) (721QN0873).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adams, L., Faseur, T., and Geuens, M. (2011). The influence of the self-regulatory focus on the effectiveness of stop-smoking campaigns for young smokers. J. Consum. Aff. 45 (2), 275–305. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6606.2011.01203.x

Allen, M. S., and Desille, A. E. (2017). Personality and sexuality in older adults. Psychol. HEALTH 32 (7), 843–859. doi:10.1080/08870446.2017.1307373

Allen, M. S., Greenlees, I., and Jones, M. (2013). Personality in sport: A comprehensive review. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 6 (1), 184–208. doi:10.1080/1750984X.2013.769614

Allen, M. S., Mison, E. A., Robson, D. A., and Laborde, S. (2021). Extraversion in sport: A scoping review. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 14 (1), 229–259. doi:10.1080/1750984X.2020.1790024

Alzubaidi, H., Slade, E. L., and Dwivedi, Y. K. (2021). Examining antecedents of consumers' pro-environmental behaviours: TPB extended with materialism and innovativeness. J. Bus. Res. 122, 685–699. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.01.017

Arena, C., Michelon, G., and Trojanowski, G. (2018). Big egos can Be green: A study of CEO hubris and environmental innovation. Brit. J. Manage. 29 (2), 316–336. doi:10.1111/1467-8551.12250

Boheim, R., and Lackner, M. (2015). Gender and risk taking: Evidence from jumping competitions. J. R. Stat. Soc. A 178 (4), 883–902. doi:10.1111/rssa.12093

Böheim, R., Lackner, M., and Wagner, W. (2022). Raising the bar: Causal evidence on gender differences in risk-taking from a natural experiment. J. Sports Econ. 23 (4), 460–478. doi:10.1177/15270025211059533

Bromiley, P., and Rau, D. (2016). Social, behavioral, and cognitive influences on upper echelons during strategy process. J. Manag. 42 (1), 174–202. doi:10.1177/0149206315617240

Calza, F., Profumo, G., and Tutore, I. (2016). Corporate ownership and environmental proactivity. Bus. Strategy Environ. 25 (6), 369–389. doi:10.1002/bse.1873

Cannella, V., Villar, F., Serrat, R., and Tulle, E. (2021). Psychosocial aspects of participation in competitive sports among older athletes: A scoping review. Gerontologist 62, e468–e480. doi:10.1093/geront/gnab083

Cao, G., and Zhang, J. (2021). Guanxi, overconfidence and corporate fraud in China. Chin. Manag. Stud. 15 (3), 501–556. doi:10.1108/CMS-04-2020-0166

Chen, S., Sun, Z., Tang, S., and Wu, D. (2011). Government intervention and investment efficiency: Evidence from China. J. Corp. FINANCE 17 (2), 259–271. doi:10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2010.08.004

Cho, C. K., Cho, T. S., and Lee, J. (2019). Managerial attributes, consumer proximity, and corporate environmental performance. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 26 (1), 159–169. doi:10.1002/csr.1668

Crust, L. (2020). Personality and mountaineering: A critical review and directions for future research. PERSONALITY Individ. Differ. 163, 110073. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2020.110073

De Mendonca, T., and Zhou, Y. (2019). What does targeting ecological sustainability mean for company financial performance? Bus. Strategy Environ. 28 (8), 1583–1593. doi:10.1002/bse.2334

Eagleton, J. R., McKelvie, S. J., and De Man, A. (2007). Extraversion and neuroticism in team sport participants, individual sport participants, and nonparticipants. Percept. Mot. Ski., 105(1), 265–275. doi:10.2466/pms.105.1.265-275

Farre-Mensa, J., and Ljungqvist, A. (2016). Do measures of financial constraints measure financial constraints? Rev. Financ. Stud. 29 (2), 271–308. doi:10.1093/rfs/hhv052

Flammer, C., Hong, B., and Minor, D. (2019). Corporate governance and the rise of integrating corporate social responsibility criteria in executive compensation: Effectiveness and implications for firm outcomes. Strateg. Manag. J. 40 (7), 1097–1122. doi:10.1002/smj.3018

Gao, Y., and Hafsi, T. (2015). Government intervention, peers' giving and corporate philanthropy: Evidence from Chinese private SMEs. J. Bus. Ethics 132 (2), 433–447. doi:10.1007/s10551-014-2329-y

Golby, J., and Sheard, M. (2006). The relationship between genotype and positive psychological development in national-level swimmers. Eur. Psychol. 11 (2), 143–148. doi:10.1027/1016-9040.11.2.143

Hadlock, C. J., and Pierce, J. R. (2010). New evidence on measuring financial constraints: Moving beyond the KZ index. Rev. Financ. Stud. 23 (5), 1909–1940. doi:10.1093/rfs/hhq009

Hambrick, D. C., and Mason, P. A. (1984). Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top managers. Acad. Manag. Rev. 9 (2), 193–206. doi:10.2307/258434

Hörisch, J., Kollat, J., and Brieger, S. A. (2017). What influences environmental entrepreneurship? A multilevel analysis of the determinants of entrepreneurs' environmental orientation. Small Bus. Econ. 48 (1), 47–69. doi:10.1007/s11187-016-9765-2

Hu, J., Wang, S., and Xie, F. (2018). Environmental responsibility, market valuation, and firm characteristics: Evidence from China. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 25 (6), 1376–1387. doi:10.1002/csr.1646

Husted, B. W., and Sousa-Filho, J. M. D. (2019). Board structure and environmental, social, and governance disclosure in Latin America. J. Bus. Res. 102, 220–227. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.01.017

Jiang, W., Wang, A. X., Zhou, K. Z., and Zhang, C. (2020). Stakeholder relationship capability and firm innovation: A contingent analysis. J. Bus. Ethics 167 (1), 111–125. doi:10.1007/s10551-019-04161-4

Kong, D., Xiang, J., Zhang, J., and Lu, Y. (2019). Politically connected independent directors and corporate fraud in China. Acc. Finance 58 (5), 1347–1383. doi:10.1111/acfi.12449

Laborde, S., Allen, M. S., Katschak, K., Mattonet, K., and Lachner, N. (2020). Trait personality in sport and exercise psychology: A mapping review and research agenda. Int. J. sport Exerc. Psychol. 18 (6), 701–716. doi:10.1080/1612197X.2019.1570536

Li, B., Xu, L., McIver, R., Wu, Q., and Pan, A. (2020). Green M&A, legitimacy and risk‐taking: Evidence from China’s heavy polluters. Acc. Finance 60 (1), 97–127. doi:10.1111/acfi.12597

Li, J., Xia, J., and Zajac, E. J. (2018). On the duality of political and economic stakeholder influence on firm innovation performance: Theory and evidence from Chinese firms. Strateg. Manag. J. 39 (1), 193–216. doi:10.1002/smj.2697

Li, X., Yang, J., Liu, H., and Zhuang, X. (2021). Entrepreneurial orientation and green management in an emerging economy: The moderating effects of social legitimacy and ownership type. J. Clean. Prod. 316, 128293. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128293

Liang, H., and Renneboog, L. (2017). On the foundations of corporate social responsibility. J. Finance 72 (2), 853–910. doi:10.1111/jofi.12487

Liao, Z., and Long, S. (2018). CEOs' regulatory focus, slack resources and firms' environmental innovation. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 25 (5), 981–990. doi:10.1002/csr.1514

Liao, Z., Zhang, M., and Wang, X. (2019). Do female directors influence firms' environmental innovation? The moderating role of ownership type. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 26 (1), 257–263. doi:10.1002/csr.1677

Liu, Z., Li, X., Peng, X., and Lee, S. (2020). Green or nongreen innovation? Different strategic preferences among subsidized enterprises with different ownership types. J. Clean. Prod. 245, 118786. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118786

Marchini, P. L., Tibiletti, V., Mazza, T., and Gabrielli, G. (2022). Gender quotas and the environment: Environmental performance and enforcement. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 29 (1), 256–272. doi:10.1002/csr.2200

Ou, A. Y., Waldman, D. A., and Peterson, S. J. (2018). Do humble CEOs matter? An examination of CEO humility and firm outcomes. J. Manag. 44 (3), 1147–1173. doi:10.1177/0149206315604187

Pryor, C., Holmes, R. M., Webb, J. W., and Liguori, E. W. (2019). Top executive goal orientations’ effects on environmental scanning and performance: Differences between founders and nonfounders. J. Manag. 45 (5), 1958–1986. doi:10.1177/0149206317737354

Pan, X., Chen, X., Sinha, P., and Dong, N. (2019). Are firms with state ownership greener? An institutional complexity view. Bus. Strategy Environ. 29 (1), 197–211. doi:10.1002/bse.2358

Petrenko, O. V., Aime, F., Ridge, J., and Hill, A. (2016). Corporate social responsibility or CEO narcissism? CSR motivations and organizational performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 37 (2), 262–279. doi:10.1002/smj.2348

Piepiora, P. (2021a). Assessment of personality traits influencing the performance of men in team sports in terms of the big five. Front. Psychol. 12, 679724. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.679724

Piepiora, P., Kwiatkowski, D., Bagińska, J., and Agouridas, D. (2021). Sports level and the personality of American football players in Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18 (24), 13026. doi:10.3390/ijerph182413026

Piepiora, P. (2021b). Personality profile of individual sports champions. Brain Behav. 11 (6), e02145. doi:10.1002/brb3.2145

Piepiora, P., Piepiora, Z., and Bagińska, J. (2022). Personality and sport experience of 20–29-year-old polish male professional athletes. Front. Psychol. 13, 854804. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.854804

Provasnek, A. K., Sentic, A., and Schmid, E. (2017). Integrating eco-innovations and stakeholder engagement for sustainable development and a social license to operate. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 24 (3), 173–185. doi:10.1002/csr.1406

Ren, S., Huang, M., Liu, D., and Yan, J. (2022). Understanding the impact of mandatory CSR disclosure on green innovation: Evidence from Chinese listed firms. Br. J. Manag. doi:10.1111/1467-8551.12609

Ren, S., Wang, Y., Hu, Y., and Yan, J. (2021). CEO hometown identity and firm green innovation. Bus. Strategy Environ. 30 (2), 756–774. doi:10.1002/bse.2652

Richardson, S. (2006). Over-investment of free cash flow. Rev. Acc. Stud. 11 (2-3), 159–189. doi:10.1007/s11142-006-9012-1

Saeed, A., Riaz, H., Liedong, T. A., and Rajwani, T. (2022). The impact of TMT gender diversity on corporate environmental strategy in emerging economies. J. Bus. Res. 141, 536–551. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.11.057

Shahab, Y., Ntim, C. G., Chen, Y., Ullah, F., Li, H. X., and Ye, Z. (2019). Chief executive officer attributes, sustainable performance, environmental performance, and environmental reporting: New insights from upper echelons perspective. Bus. Strategy Environ. 29 (1), 1–16. doi:10.1002/bse.2345

Spanjol, J., Tam, L., Qualls, W. J., and Bohlmann, J. D. (2011). New product team decision making: Regulatory focus effects on number, type, and timing decisions. J. Prod. Innov. Manage. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5885.2011.00833.x

Steca, P., Baretta, D., Greco, A., D'Addario, M., and Monzani, D. (2018). Associations between personality, sports participation and athletic success. A comparison of Big Five in sporting and non-sporting adults. PERSONALITY Individ. Differ. 121, 176–183. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2017.09.040

Stephie Tsai, H., Wu, Y., and Xu, B. (2021). Does capital market drive corporate investment efficiency? Evidence from equity lending supply. J. Corp. FINANCE 69, 102042. doi:10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2021.102042

Stroessner, S. J., Scholer, A. A., Marx, D. M., and Weisz, B. M. (2015). When threat matters: Self-regulation, threat salience, and stereotyping. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 59, 77–89. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2015.03.003

Sun, H., Edziah, B. K., Sun, C., and Kporsu, A. K. (2019). Institutional quality, green innovation and energy efficiency. ENERGY POLICY 135, 111002. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2019.111002

Wang, H., Luo, T., Tian, G. G., and Yan, H. (2020). How does bank ownership affect firm investment? Evidence from China. J. Bank. FINANCE 113, 105741. doi:10.1016/j.jbankfin.2020.105741

Wang, K., and Jiang, W. (2021). State ownership and green innovation in China: The contingent roles of environmental and organizational factors. J. Clean. Prod. 314, 128029. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128029

Wang, R., Lee, C. J., Hsu, S. C., Zhen, S. N., and Chen, J. H. (2020). Effects of career horizon and corporate governance in China's construction industry: Multilevel study of top management fraud. J. Manage. Eng. 36 (5). doi:10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000816

Wang, Y., Qiu, Y., and Luo, Y. (2022). CEO foreign experience and corporate sustainable development: Evidence from China. Bus. Strategy Environ. 31 (5), 2036–2051. doi:10.1002/bse.3006

Xia, D., Chen, W., Gao, Q., Zhang, R., and Zhang, Y. (2021). Research on enterprises’ intention to adopt green technology imposed by environmental regulations with perspective of state ownership. Sustainability 13 (3), 1368. doi:10.3390/su13031368

Yang, D., Wang, A. X., Zhou, K. Z., and Jiang, W. (2019). Environmental strategy, institutional force, and innovation capability: A managerial cognition perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 159 (4), 1147–1161. doi:10.1007/s10551-018-3830-5

Yu, G., Zhong, H., and Fan, R. (2019). Privatization, financing constraints and enterprise innovation: Evidence from Chinese industrial enterprises [民营化、融资约束与企业创新——来自中国工业企业的证据]. Finance Res. 04, 75–91.

Yu, J., Lo, C. W., and Li, P. H. Y. (2017). Organizational visibility, stakeholder environmental pressure and corporate environmental responsiveness in China. Bus. Strategy Environ. 26 (3), 371–384. doi:10.1002/bse.1923

Zhang, L., Xu, Y., and Chen, H. (2021). Do returnee executives value corporate philanthropy? Evidence from China. J. Bus. Ethics 179, 411–430. doi:10.1007/s10551-021-04870-9

Zhang, X., Li, Z., and Li, C. (2019). Banking competition, financing constraints and enterprise innovation: Empirical evidence from Chinese industrial enterprises [银行业竞争、融资约束与企业创新——中国工业企业的经验证据]. Finance Res. 10, 98–116.

Zhou, F., Zhang, Z., Yang, J., Su, Y., and An, Y. (2018). Delisting pressure, executive compensation, and corporate fraud: Evidence from China. Pacific-Basin Finance J. 48, 17–34. doi:10.1016/j.pacfin.2018.01.003

Keywords: sport experience, upper echelon theory, environmental proactivity, state-owned enterprises, moderating effect

Citation: Zhang J, Pan P, Pan J and Feng Y (2022) How top managers’ sport experience exploits environmental proactivity in state-owned enterprises.. Front. Environ. Sci. 10:1026570. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.1026570

Received: 24 August 2022; Accepted: 12 October 2022;

Published: 03 November 2022.

Edited by:

Huaping Sun, Jiangsu University, ChinaReviewed by:

Valeria Naciti, University of Messina, ItalyHafeez Ullah, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, China

Copyright © 2022 Zhang, Pan, Pan and Feng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jianhua Pan, cGFuamh1YUBjcXUuZWR1LmNu; Yuan Feng, MTc2MjAxOTAxNTM5NzJAc3R1LnhtdS5lZHUuY24=

Jing Zhang

Jing Zhang Pengyuan Pan2

Pengyuan Pan2